Biological Control Properties of Two Strains of Priestia megaterium Isolated from Tar Spots in Maize Leaves

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Organisms

2.2. Assays Using Cell-Free Extracts

2.3. pH Bioassay

2.4. Young Plant Bioassay

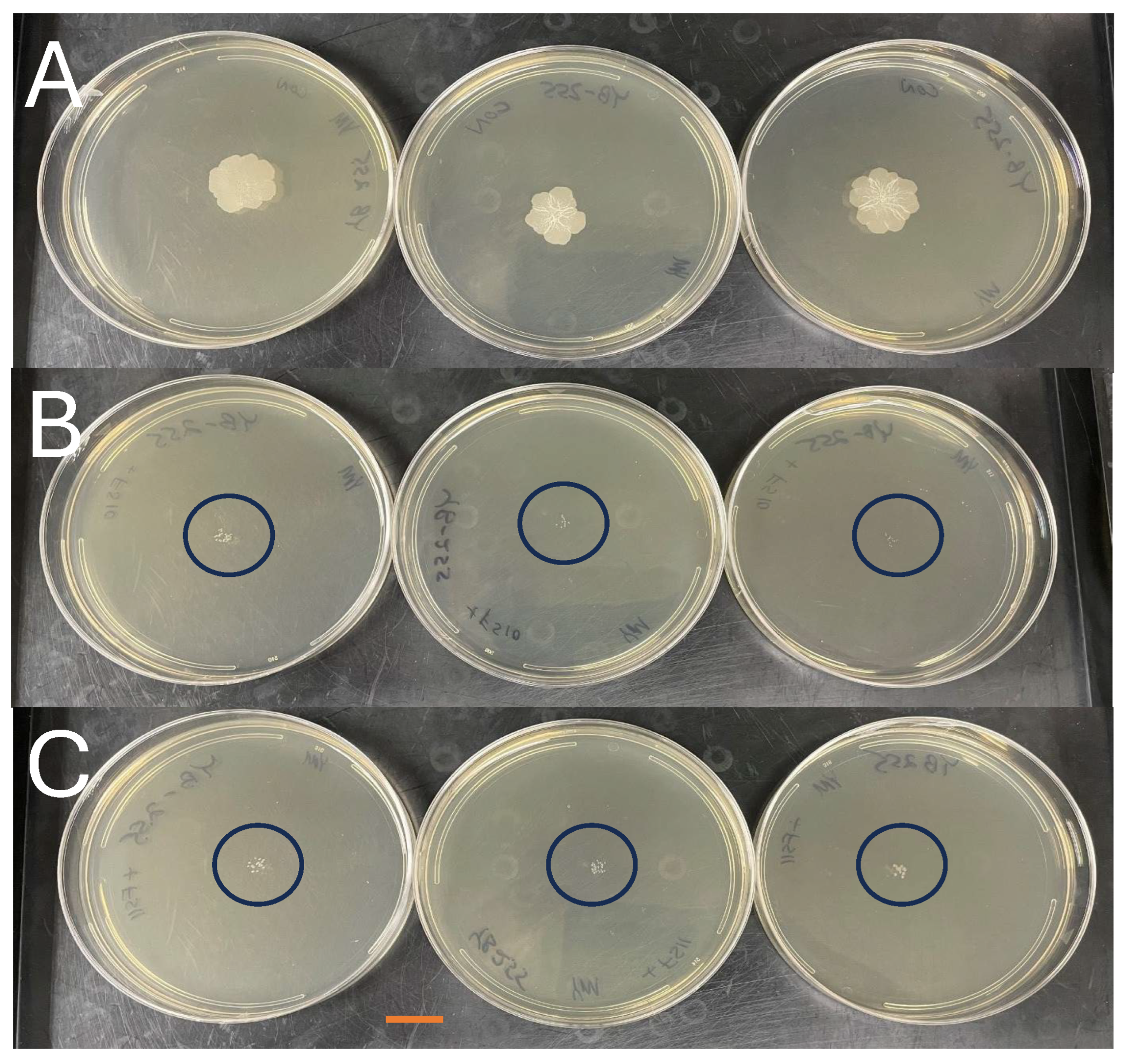

2.5. In Vitro Bioassay to Determine the Antifungal Activity of Volatiles Produced by FS10 and FS11

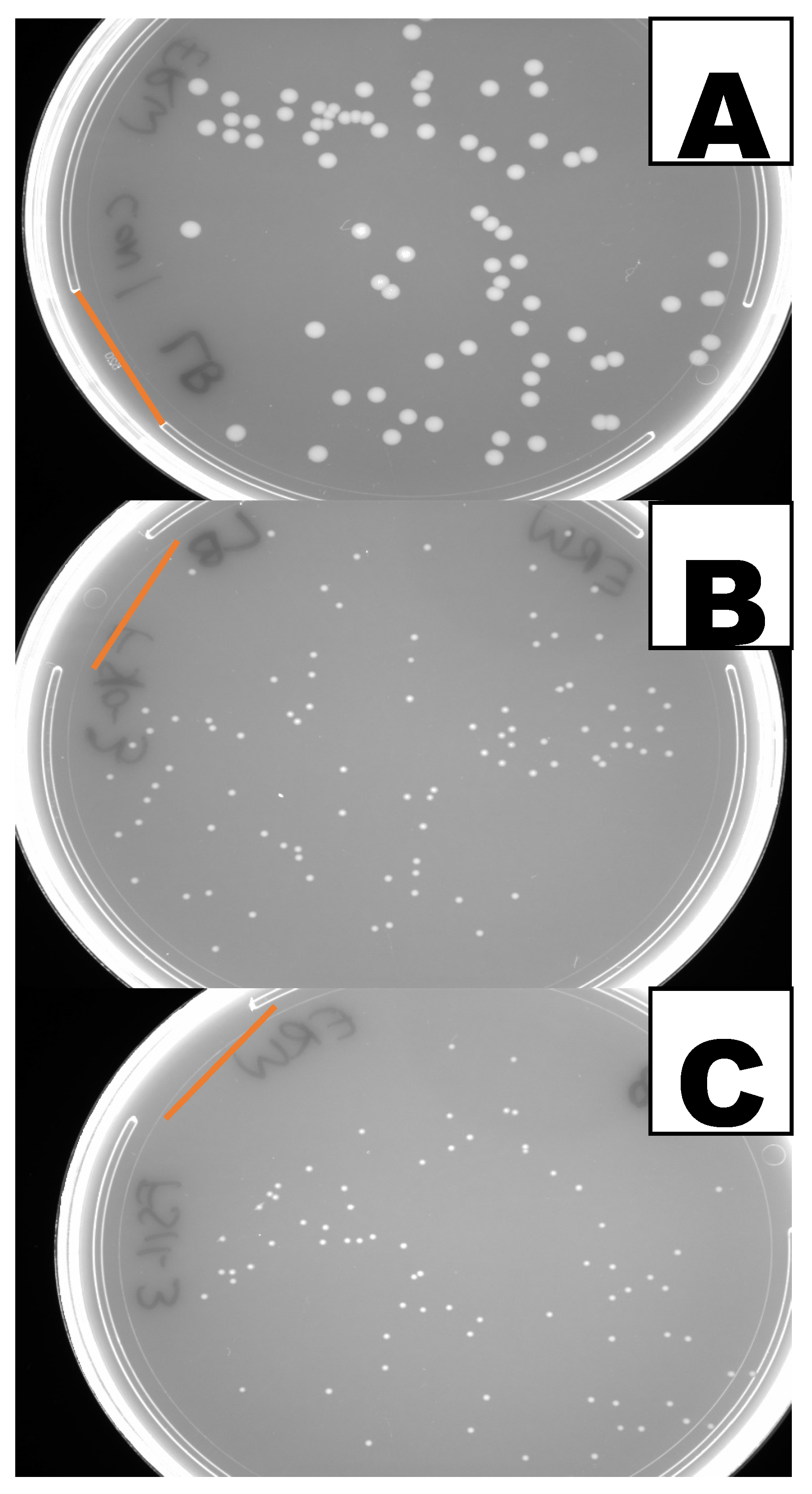

2.6. In Vitro Bioassay to Determine the Antibacterial Activity of Volatiles Produced by FS10 and FS11

2.7. Measurement of Sizes of Bacterial CFUs

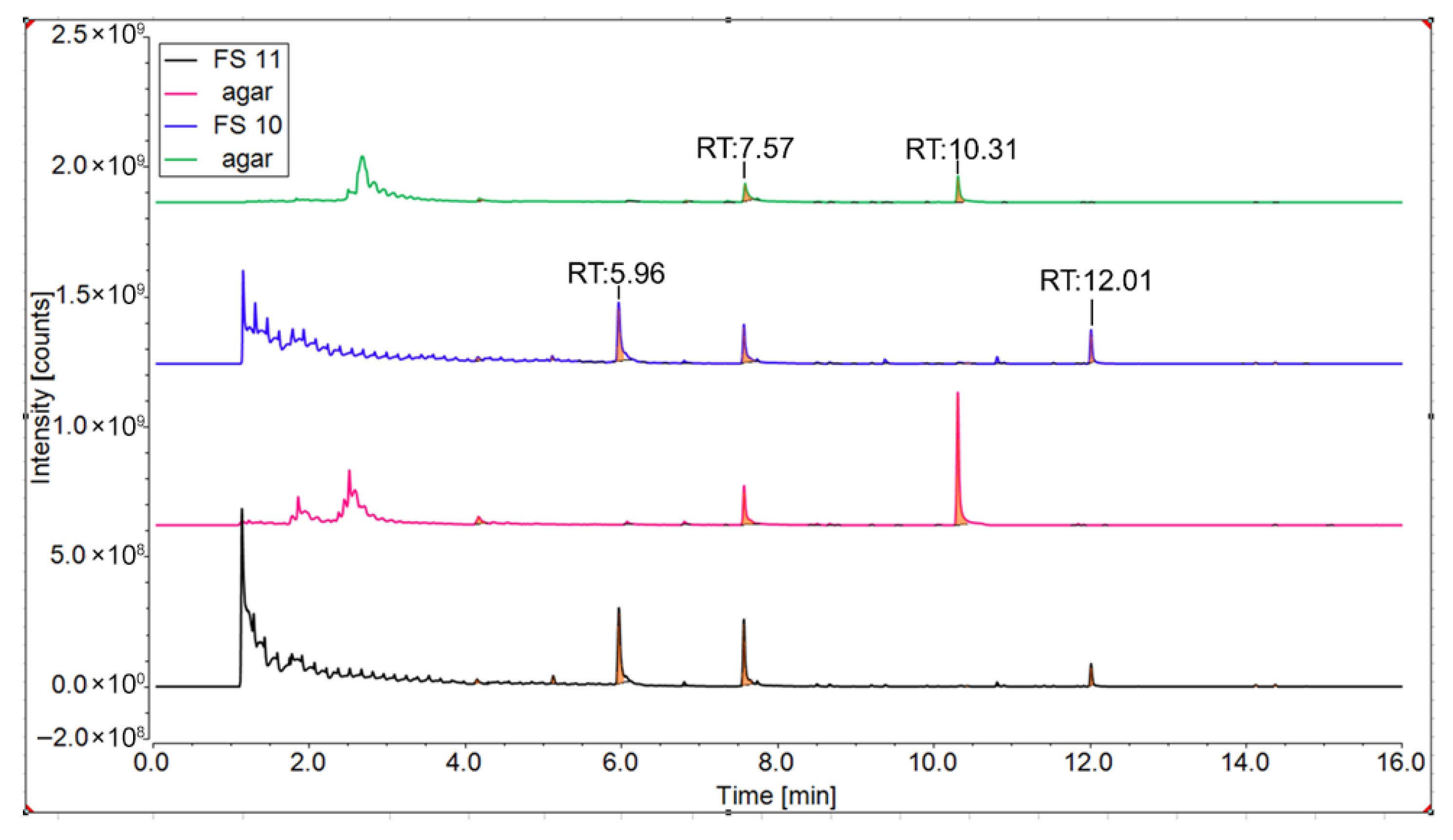

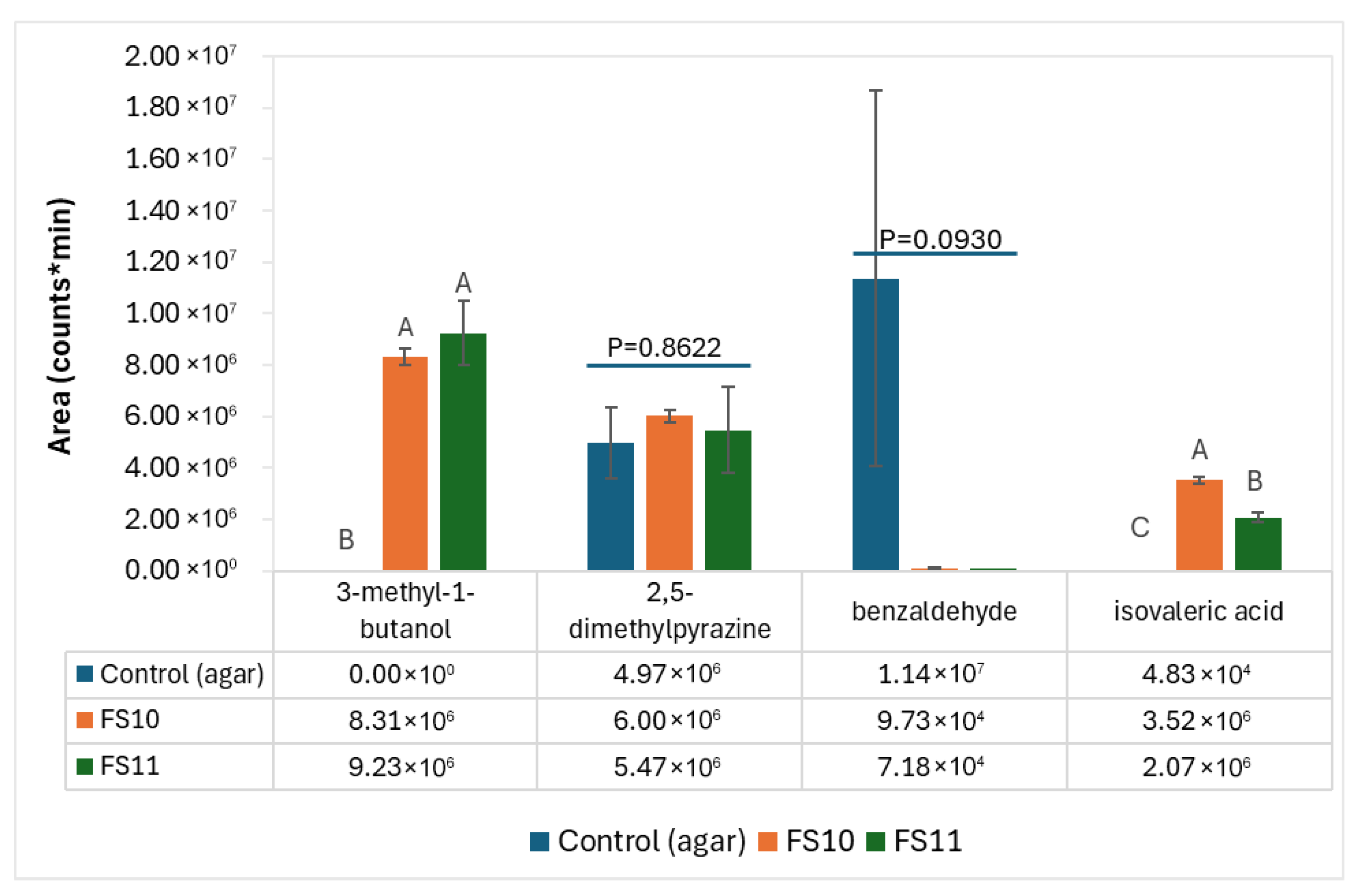

2.8. Identification of Volatiles

2.9. Bioassays Using the Volatiles Isovaleric Acid and 3-Methyl-1-butanol

2.10. Statistics

2.11. Data Collection

3. Results

3.1. Antifungal Activity of Volatiles Produced by the P. megaterium Strains

3.2. Identification of Volatiles Produced by the P. megaterium Strains

3.3. Inhibition of Bacterial Growth by the P. megaterium Volatiles

3.4. Inhibition of Fungal and Bacterial Growth Using P. megaterium Cell-Free Extracts

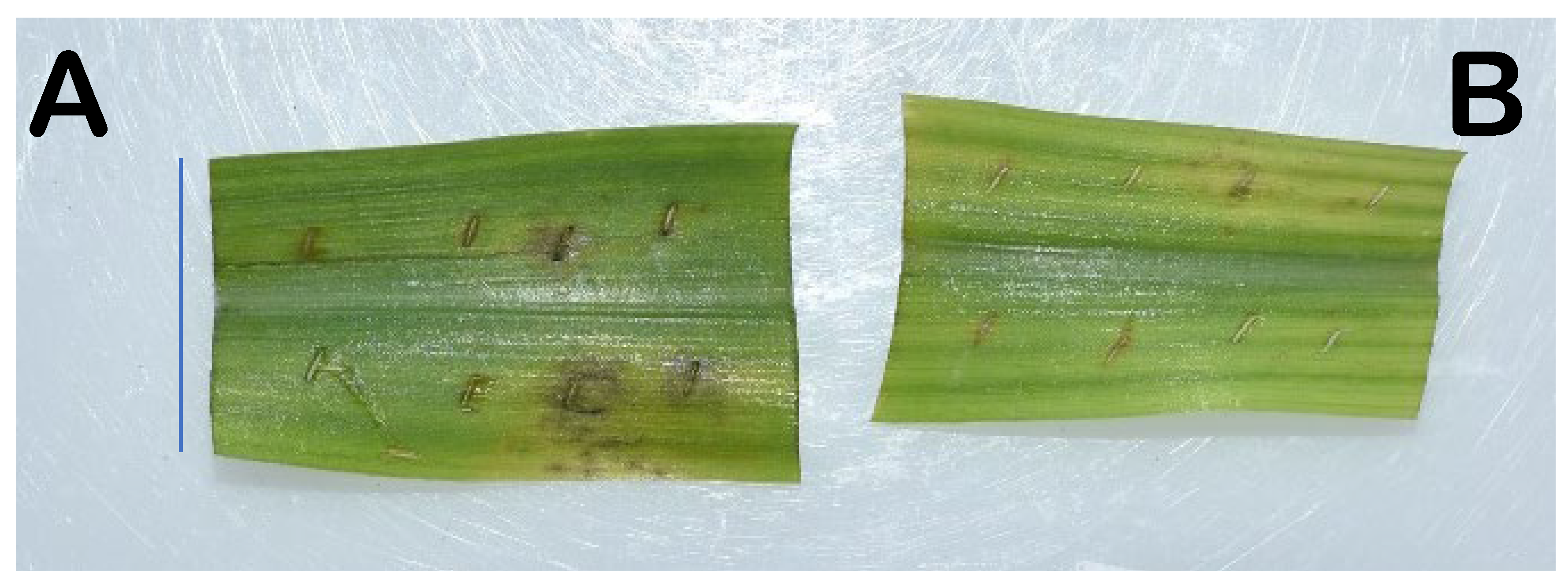

3.5. Reduction in Maize Pathogen Leaf Damage with P. megaterium Seed Treatment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Biopesticide Active Ingredients. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/ingredients-used-pesticide-products/biopesticide-active-ingredients (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Fira, D.; Dimkić, I.; Berić, T.; Lozo, J.; Stanković, S. Biological control of plant pathogens by Bacillus species. J. Biotechnol. 2018, 285, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debois, D.; Jourdan, E.; Smargiasso, N.; Thonart, P.; De Pauw, E.; Ongena, M. Spatiotemporal monitoring of the antibiome secreted by Bacillus biofilms on plant roots using MALDI mass spectrometry imaging. Anal. Chem. 2014, 86, 4431–4438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Fan, X.; Cai, X.; Hu, F. The inhibitory mechanisms by mixtures of two endophytic bacterial strains isolated from Ginkgo biloba against pepper phytophthora blight. Biol. Control 2015, 85, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, Y.; Sui, S.; Zeng, Q.; Shen, R. Biocontrol potential of Bacillus velezensis strain E69 against rice blast and other fungal diseases. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2019, 52, 1908–1917. [Google Scholar]

- Mendes, R.; Garbeva, P.; Raaijmakers, J.M. The rhizosphere microbiome: Significance of plant beneficial, plant pathogenic, and human pathogenic microorganisms. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2013, 37, 634–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInroy, J.A.; Kloepper, J.W. Survey of indigenous bacterial endophytes from cotton and sweet corn. Plant Soil. 1995, 173, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.S.; Patel, S.; Saini, N.; Chen, S. Robust demarcation of 17 distinct Bacillus species clades, proposed as novel Bacillaceae genera, by phylogenomics and comparative genomic analyses: Description of Robertmurraya kyonggiensis sp. nov. and proposal for an emended genus Bacillus limiting it only to the members of the Subtilis and Cereus clades of species. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2020, 70, 5753–5798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.; Goodwin, S.B. Exploring the corn microbiome: A detailed review on current knowledge, techniques, and future directions. PhytoFrontiers 2022, 2, 158–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhao, H.; Chen, S. Colonization of maize and rice plants by strain Bacillus megaterium C4. Curr. Microbiol. 2006, 52, 186–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanovics, G.; Alfoldi, L. A new antibacterial principle: Megacine. Nature 1954, 174, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Tersch, M.A.; Carlton, B.C. Bacteriocin from Bacillus megaterium ATCC 19213: Comparative studies with megacin A-216. J. Bacteriol. 1983, 155, 866–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, I. A bacteriocin specifically affecting DNA synthesis in Bacillus megaterium. J. Mol. Biol. 1965, 12, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, B.; Purkayastha, R. Isolation, characterization and biological activities of a toxin from Bacillus megaterium (B-23). Indian. J. Exp. Biol. 1989, 27, 1060–1063. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shimada, N.; Hasegawa, S.; Harada, T.; Tomisawa, T.; Fujii, A.; Takita, T. Oxetanocin, a novel nucleoside from bacteria. J. Antibiot. 1986, 39, 1623–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malanicheva, I.; Kozlov, D.; Sumarukova, I.; Efremenkova, O.; Zenkova, V.; Katrukha, G.; Reznikova, M.; Tarasova, O.; Sineokii, S.; El’-Registan, G. Antimicrobial activity of Bacillus megaterium strains. Microbiology 2012, 81, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, F.; Tanaka, N.; Yonehara, H.; Umezawa, H. Studies on bacimethrin, a new antibiotic from B. megaterium. I. Preparations and its properties. J. Antibiot. Ser. A 1962, 15, 191–196. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, F.; Takeuchi, S.; Yonehara, H. Studies on bacimethrin, a new antibiotic from B. megatherium. II. The chemical structure of bacimethrin. J. Antibiot. Ser. A 1962, 15, 197–201. [Google Scholar]

- Pueyo, M.T.; Bloch, C., Jr.; Carmona-Ribeiro, A.M.; Di Mascio, P. Lipopeptides produced by a soil Bacillus megaterium strain. Microb. Ecol. 2009, 57, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Kong, Q.; Qin, C.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Y.; Lv, R.; Zhou, G. Identification of lipopeptides in Bacillus megaterium by two-step ultrafiltration and LC–ESI–MS/MS. AMB Expr. 2016, 6, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, R.; Groulx, E.; Defilippi, S.; Erak, T.; Tambong, J.T.; Tweddell, R.J.; Tsopmo, A.; Avis, T.J. Physiological and molecular characterization of compost bacteria antagonistic to soil-borne plant pathogens. Can. J. Microbiol. 2017, 63, 411–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, A.; Rana, A.; Dhaka, R.K.; Singh, A.P.; Chahar, M.; Singh, S.; Nain, L.; Singh, K.P.; Minz, D. Bacterial volatile organic compounds as biopesticides, growth promoters and plant-defense elicitors: Current understanding and future scope. Biotechnol. Adv. 2022, 63, 108078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weisskopf, L.; Schulz, S.; Garbeva, P. Microbial volatile organic compounds in intra-kingdom and inter-kingdom interactions. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 391–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mannaa, M.; Oh, J.Y.; Kim, K.D. Biocontrol activity of volatile-producing Bacillus megaterium and Pseudomonas protegens against Aspergillus flavus and aflatoxin production on stored rice grains. Mycobiology 2017, 45, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mannaa, M.; Kim, K.D. Biocontrol activity of volatile-producing Bacillus megaterium and Pseudomonas protegens against Aspergillus and Penicillium spp. predominant in stored rice grains: Study II. Mycobiology 2018, 46, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghunath, S.A.; Manjunatha, Y.; Rayappa, K. Synthesis, antimicrobial, and antioxidant activities of some new indole analogues containing pyrimidine and fused pyrimidine systems. Med. Chem. Res. 2012, 21, 3809–3817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, R.M.; Reddy, G.N.; Sreeramulu, J. Synthesis of some new pyrazolo-pyrazole derivatives containing indoles with antimicrobial activity. Der Pharma Chem. 2011, 3, 301–309. [Google Scholar]

- Saleh, A.E.; Ul-Hassan, Z.; Zeidan, R.; Al-Shamary, N.; Al-Yafei, T.; Alnaimi, H.; Higazy, N.S.; Migheli, Q.; Jaoua, S. Biocontrol activity of Bacillus megaterium BM344-1 against toxigenic fungi. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 10984–10990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathke, K.J.; Jochum, C.C.; Yuen, G.Y. Biological control of bacterial leaf streak of corn using systemic resistance-inducing Bacillus strains. Crop Prot. 2022, 155, 105932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planchamp, C.; Glauser, G.; Mauch-Mani, B. Root inoculation with Pseudomonas putida KT2440 induces transcriptional and metabolic changes and systemic resistance in maize plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 5, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieterse, C.M.; Zamioudis, C.; Berendsen, R.L.; Weller, D.M.; Van Wees, S.C.; Bakker, P.A. Induced systemic resistance by beneficial microbes. Ann. Rev. Phytopathol. 2014, 52, 347–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloepper, J.W.; Ryu, C.-M.; Zhang, S. Induced systemic resistance and promotion of plant growth by Bacillus spp. Phytopathology 2004, 94, 1259–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Hou, Z.; Zhou, D.; Jia, M.; Lu, S.; Yu, J.A. A plant growth-promoting bacteria Priestia megaterium JR48 induces plant resistance to the crucifer black rot via a salicylic acid-dependent signaling pathway. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1046181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, T.; Yao, X.-Z.; Wu, C.-Y.; Zhang, W.; He, W.; Dai, C.-C. Endophytic Bacillus megaterium triggers salicylic acid-dependent resistance and improves the rhizosphere bacterial community to mitigate rice spikelet rot disease. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 2020, 156, 103710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogoi, P.; Sharmah, B.; Manna, P.; Gogoi, P.; Baishya, G.; Saikia, R. Salicylic acid induced by Bacillus megaterium causing systemic resistance against collar rot in Capsicum chinense. Plant Cell Rep. 2025, 44, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, U.; Chakraborty, B.; Basnet, M. Plant growth promotion and induction of resistance in Camellia sinensis by Bacillus megaterium. J. Basic. Microbiol. 2006, 46, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, B.; Chlebek, D.; Hupert-Kocurek, K. Priestia megaterium KW16: A novel plant growth-promoting and biocontrol agent against Rhizoctonia solani in oilseed rape (Brassica napus L.)—Functional and genomic insights. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jetiyanon, K.; Boontawee, S.; Padawan, S.; Plianbangchang, P. Efficacy of Bacillus atrophaeus strain RS36 and Priestia megaterium strain RS91 with partially reduced fertilization for bacterial leaf blight suppression in rice seedlings. Asian Health Sci. Technol. Rep. 2024, 32, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.-G.; Tao, R.-X.; Hao, Z.-N.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X. Induction of resistance in cucumber against seedling damping-off by plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) Bacillus megaterium strain L8. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2011, 10, 6920–6927. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, E.T.; Dowd, P.F.; Ramirez, J.L.; Behle, R.W. Potential biocontrol agents of corn tar spot disease isolated from overwintered Phyllachora maydis stromata. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E.T.; Dowd, P.F.; Ramirez, J.L. Priestia megaterium Strains and Metabolites, Compositions Comprising Such, and Uses Thereof. U.S. Patent Application Serial No. 63/677,632, 22 July 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, E.T.; Evans, K.O.; Dowd, P.F. Antifungal activity of a synthetic cationic peptide against the plant pathogens Colletotrichum graminicola and three Fusarium species. Plant Pathol. J. 2015, 31, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipps, S.; Lipka, A.E.; Mideros, S.; Jamann, T. Inhibition of ethylene involved in resistance to E. turcicum in an exotic-derived double haploid maize population. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1272951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckman, P.M.; Payne, G.A. External growth, penetration, and development of Cercospora zeae-maydis in corn leaves. Phytopathol. 1982, 72, 810–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Media Formulas. Available online: https://nrrl.ncaur.usda.gov/media-formulas (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Ahimou, F.; Jacques, P.; Deleu, M. Surfactin and iturin A effects on Bacillus subtilis surface hydrophobicity. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2000, 27, 749–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segura Munoz, R.R.; Sourjik, V. Collective dynamics of Escherichia coli growth under near-lethal acid stress. mBio 2025, 16, e01932-25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B37 Observations. Available online: https://npgsweb.ars-grin.gov/gringlobal/accessiondetail?id=1445403 (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Dowd, P.F.; Johnson, E.T. Maize inbred leaf and stalk tissue resistance to the pathogen Fusarium graminearum can influence control efficacy of Beauveria bassiana towards European corn borers and fall armyworms. Int. J. Plant Biol. 2024, 15, 673–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettitt, T.; Wainwright, M.; Wakeham, A.; White, J. A simple detached leaf assay provides rapid and inexpensive determination of pathogenicity of Pythium isolates to ‘all year round’(AYR) chrysanthemum roots. Plant Pathol. 2011, 60, 946–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.A.; Rasband, W.S.; Eliceiri, K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Cadwallader, K.R.; Jeong, E.-J.; Cha, Y.-J. Effect of refrigerated and thermal storage on the volatile profile of commercial aseptic Korean soymilk. Prev. Nutr. Food Sci. 2009, 14, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, T.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, M.; Wei, X.; Kan, J.; Zalán, Z.; Wang, K.; Du, M. Volatile organic compounds produced by Pseudomonas fluorescens ZX as potential biological fumigants against gray mold on postharvest grapes. Biol. Control 2021, 163, 104754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.B.; Alimova, Y.; Myers, T.M.; Ebersole, J.L. Short-and medium-chain fatty acids exhibit antimicrobial activity for oral microorganisms. Arch. Oral. Biol. 2011, 56, 650–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toffano, L.; Fialho, M.B.; Pascholati, S.F. Potential of fumigation of orange fruits with volatile organic compounds produced by Saccharomyces cerevisiae to control citrus black spot disease at postharvest. Biol. Control 2017, 108, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidorova, D.E.; Plyuta, V.A.; Padiy, D.A.; Kupriyanova, E.V.; Roshina, N.V.; Koksharova, O.A.; Khmel, I.A. The effect of volatile organic compounds on different organisms: Agrobacteria, plants and insects. Microorganisms 2021, 10, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmassry, M.M.; Farag, M.A.; Preissner, R.; Gohlke, B.-O.; Piechulla, B.; Lemfack, M.C. Sixty-one volatiles have phylogenetic signals across bacterial domain and fungal kingdom. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 557253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves-López, C.; Serio, A.; Gianotti, A.; Sacchetti, G.; Ndagijimana, M.; Ciccarone, C.; Stellarini, A.; Corsetti, A.; Paparella, A. Diversity of food-borne Bacillus volatile compounds and influence on fungal growth. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2015, 119, 487–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Francesco, A.; Zajc, J.; Gunde-Cimerman, N.; Aprea, E.; Gasperi, F.; Placì, N.; Caruso, F.; Baraldi, E. Bioactivity of volatile organic compounds by Aureobasidium species against gray mold of tomato and table grape. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 36, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; He, Y.; Han, X.; Song, Z.; Shi, J. The volatile components from Bacillus cereus N4 can restrain brown rot of peach fruit by inhibiting sporulation of Monilinia fructicola and inducing disease resistance. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2024, 210, 112755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Li, G.; Zhang, J.; Yang, L.; Che, H.; Jiang, D.; Huang, H. Control of postharvest Botrytis fruit rot of strawberry by volatile organic compounds of Candida intermedia. Phytopathology 2011, 101, 859–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, S.; Linton, C.; Edwards, R.; Drury, E. Isoamyl alcohol (3-methyl-1-butanol), a volatile anti-cyanobacterial and phytotoxic product of some Bacillus spp. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 1991, 13, 130–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muria-Gonzalez, M.J.; Yeng, Y.; Breen, S.; Mead, O.; Wang, C.; Chooi, Y.-H.; Barrow, R.A.; Solomon, P.S. Volatile molecules secreted by the wheat pathogen Parastagonospora nodorum are involved in development and phytotoxicity. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashida-Soiza, G.; Uchida, A.; Mori, N.; Kuwahara, Y.; Ishida, Y. Purification and characterization of antibacterial substances produced by a marine bacterium Pseudoalteromonas haloplanktis strain. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2008, 105, 1672–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Bai, H.; Bai, Z.; Han, J.; Luo, D.; Bai, L. Multi-omics analysis identifies EcCS4 is negatively regulated in response to phytotoxin isovaleric acid stress in Echinochloa crus-galli. Pest. Manag. Sci. 2024, 80, 1957–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Api, A.; Belsito, D.; Botelho, D.; Browne, D.; Bruze, M.; Burton, G., Jr.; Buschmann, J.; Dagli, M.; Date, M.; Dekant, W. RIFM fragrance ingredient safety assessment, isoamyl alcohol CAS Registry Number 123-51-3. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2017, 110, S421–S430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Api, A.; Belmonte, F.; Belsito, D.; Botelho, D.; Bruze, M.; Burton, G., Jr.; Buschmann, J.; Dagli, M.; Date, M.; Dekant, W. RIFM fragrance ingredient safety assessment, isovaleric acid, CAS Registry Number 503-74-2. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2019, 130, 110570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brüssow, H. The antibiotic resistance crisis and the development of new antibiotics. Microb. Biotechnol. 2024, 17, e14510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, R.; Mahajan, P.; Pandiya, S.; Bajaj, A.; Verma, S.K.; Yadav, P.; Kharat, A.S.; Khan, A.U.; Dua, M.; Johri, A.K. Antibiotic resistance: A global crisis, problems and solutions. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 50, 896–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fungus | Control | P. megaterium FS10 Volatiles | P. megaterium FS11 Volatiles | Length of Assay |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fusarium verticillioides (Sacc.) Nirenberg 1976 | A 59 ± 2 a (3) 6% B 45 ± 0.3 a (3) 1% | 47 ± 0.5 b (2) [20%] 2% 34 ± 0.3 b (3) [24%] 2% | 46 ± 0.6 b (3) [22%] 2% 34 ± 0.3 b (3) [24%] 2% | 119 h 96 h |

| Fusarium proliferatum (Matsush.) Nirenberg ex Gerlach and Nirenberg 1982 | A 53 ± 0.6 a (3) 2% B 40 ± 0.8 a (3) 3% | 37 ± 3 b (3) [30%] 12% 33 ± 0.7 b (3) [17%] 4% | 40 ± 0 b (2) [24%] 0% 33 ± 1 b (3) [17%] 3% | 96 h 96 h |

| Ustilago maydis (DC) Cda. YB-255 | 18 ± 0.6 a (3) 6% | 4.3 ± 0.2 b (3) [76%] 7% | 4.3 ± 0.2 b (3) [76%] 7% | 72 h |

| U. maydis YB-380 | 17 ± 1 a (3) 12% | 7 ± 0.3 b (3) [59%] 9% | 7 ± 0.4 b (3) [59%] 11% | 73 h |

| Bacterium | Control | P. megaterium FS10 Volatiles | P. megaterium FS11 Volatiles | Length of Assay |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. megaterium FS10 | 3759 ± 56 a (61) 12% | 3084 ± 46 b (53) [18%] 11% | 2705 ± 60 c (55) [28%] 16% | 23 h |

| P. megaterium FS11 | 2787 ± 44 a (75) 14% | 2659 ± 72 ab (80) [5%] 24% | 2536 ± 71 b (73) [9%] 24% | 23 h |

| Clavibacter michiganensis ssp. michiganensis corrig. (Smith 1910) Davis et al. 1984 (Cmm) B-65397 | 2701 ± 84 a (45) 21% | 40 ± 1 b (73) [98%] 28% | 34 ± 1 c (57) [99%] 20% | 144 h |

| Cmm B-65398 | 1454 ± 33 a (61) 18% | 33 ± 1 b (132) [98%] 48% | 59 ± 3 c (121) [96%] 52% | 89 h |

| Erwinia amylovora (Burrill 1882) Winslow et al. 1920 B-65467 | 1970 ± 48 a (17) 10% | 363 ± 46 b (41) [82%] 81% | 305 ± 38 b (38) [84%] 78% | 49 h |

| E. amylovora B-65468 | 2290 ± 24 a (107) 11% | 457 ± 8 b (172) [80%] 23% | 341 ± 5 c (159) [85%] 19% | 50 h |

| Treatment | Experiment 1, CFUs per Plate After 4 d | Experiment 2, CFUs per Plate After 4 d |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 25 ± 3 (3) a [22%] | 103 ± 7 (3) a [11%] |

| IVA at 83 µL L−1 | 5 ± 3 (3) b [108%] | 35 ± 9 (3) b [43%] |

| IVA at 208 µL L−1 | 0 (3) | 0 (3) |

| IVA at 417 µL L−1 | 0 (3) | 0 (3) |

| Treatment | Experiment 1, Mean Size of CFU After 3 d | Experiment 2, Mean Size of CFU After 3 d |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 463 ± 12 a (74) [22%] | 570 ± 27 a (89) [44%] |

| 3MB at 208 µL L−1 | 226 ± 6 b (72) [22%] | 282 ± 14 b (73) [42%] |

| 3MB at 417 µL L−1 | 45 ± 2 c (53) [38%] | 108 ± 7 c (46) [42%] |

| 3MB at 625 µL L−1 | 0 | 38 ± 3 d (28) [37%] |

| Organism | Mean Number of Cells, Spores or Basidiospores per Well | Control Growth | Growth with FS10 CFE Prep 1 | Growth with FS11 CFE Prep 1 | Growth at Tested pH, Length of Assay |

| Fusarium verticillioides (Sacc.) Nirenberg 1976 | 85 | Yes | Yes | Yes | ND |

| Ustilago maydis (DC) Cda. YB-255 | 100 | Yes | No, pH 6.7 ± 0.05 (4) [1%] | No, pH 5.6 ± 0.03 (4) [0.9%] | Good growth at 5.5 and 6.9, 48 h |

| Clavibacter michiganensis ssp. michiganensis corrig. (Smith 1910) Davis et al. 1984 B-65397 Gr+ | 95 | Yes | No, pH 6.0 ± 0.05 (4) [2%] | No, pH 5.6 ± 0.03 (3) [1%] | Weak growth at 5.5, good growth at 6.9, 89 h |

| Organism | Mean number of cells, spores or basidiospores per well | Control growth | Growth with FS10 CFE Prep 2 | Growth with FS11 CFE Prep 2 | Growth at tested pH |

| Fusarium proliferatum (Matsush.) Nirenberg ex Gerlach And Nirenberg 1982 | 26 | Yes | No, pH 6.9 ± 0.12 (3) [3%] | Yes | ND |

| U. maydis YB-255 | 120 | Yes | No, pH 6.2 ± 0.03 (4) [0.8%] | No, pH 5.7 ± 0.03 (4) [1%] | See above |

| E. amylovora (Burrill 1882) Winslow et al. 1920 B-65467 Gr− | 38 | Yes | No, pH 5.7 ± 0.03 (3) [1%] | No, 5.7 ± 0 (2) [0] | Good growth at 5.5 and 6.9, 30 h |

| Treatment | Control | FS10 | FS11 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bipolaris maydis (Y. Nisik. and C. Miyake) Shoemaker 1959, 2–day necrosis | 9.1 ± 0.4 a (24) 21% | 5.0 ± 0.5 b (24)] [45%] 54% | 4.1 ± 0.4 b (32) [55%] 54% |

| Colletotrichum graminicola (Ces.) G.W. Wilson 1914, 4–day necrosis, non–zero ratings only | 3.4 ± 0.3 a (12) 49% | 1.9 ± 0.1 b (10) [44%] 39% | 2.1 ± 0.3 b (11) [38%] 42% |

| Exserohilum turcicum (Pass.) K.J. Leonard and Suggs 2018, 2–day chlorosis | 1.9 ± 0.4 a (24) 105% | 0.3 ± 0.1 b (24) [84%] 164% | 0.6 ± 0.2 b (32) [68%] 186% |

| Pythium sylvaticum W.A. Campb. and F.F. Hendrix 1967, 3–day necrosis | 1.7 ± 0.2 a (24) 60% | 0.8 ± 0.2 b (24) [53%] 113% | 0.4 ± 0.1 b (32) [76%] 188% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Johnson, E.T.; Dowd, P.F.; Winkler-Moser, J.K. Biological Control Properties of Two Strains of Priestia megaterium Isolated from Tar Spots in Maize Leaves. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2465. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232465

Johnson ET, Dowd PF, Winkler-Moser JK. Biological Control Properties of Two Strains of Priestia megaterium Isolated from Tar Spots in Maize Leaves. Agriculture. 2025; 15(23):2465. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232465

Chicago/Turabian StyleJohnson, Eric T., Patrick F. Dowd, and Jill K. Winkler-Moser. 2025. "Biological Control Properties of Two Strains of Priestia megaterium Isolated from Tar Spots in Maize Leaves" Agriculture 15, no. 23: 2465. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232465

APA StyleJohnson, E. T., Dowd, P. F., & Winkler-Moser, J. K. (2025). Biological Control Properties of Two Strains of Priestia megaterium Isolated from Tar Spots in Maize Leaves. Agriculture, 15(23), 2465. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232465