Abstract

To improve the drying efficiency and quality of Scutellaria baicalensis (S. baicalensis) for both medicinal and beverage purposes, this study examined the effects of temperature, vacuum degree, and rotation speed during rotary microwave vacuum drying. The study focused on drying kinetics, physicochemical properties, and sensory quality of the Scutellaria slices. Multivariate analyses, including hierarchical cluster and correlation network analyses, were used to explore the relationship between parameters and quality. Results showed that the method significantly reduced drying time and improved moisture migration. It also preserved active components like baicalin, wogonoside, total phenolics, and polysaccharides, with high antioxidant activity maintained. Temperature was the key factor. The best balance was achieved with 50 °C, −75 kPa, and 4.2 rad/s, resulting in high drying efficiency, a sensory acceptability score of 8.8, turbidity of 12.4 NTU, and strong antioxidant capacity. Cluster analysis distinguished microwave-vacuum-dried samples from those dried by traditional methods (natural air-drying and hot-air drying). Correlation network analysis revealed positive links between sensory acceptance, active components, and liquor clarity. This optimized parameter set is recommended for producing high-quality Scutellaria ingredients for consumers.

1. Introduction

S. baicalensis Georgi is primarily distributed across Asia and is a plant resource traditionally valued for both medicinal and edible purposes [1]. Its roots have garnered significant attention due to their rich content of flavonoid bioactive compounds such as baicalin, wogonoside, baicalein, and wogamolin [2,3]. Modern pharmacological research has confirmed that these components possess multiple health-promoting effects, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and immune-enhancing properties [4,5]. Currently, one of the most common forms of S. baicalensis products on the market involves slicing and drying its roots for direct infusion, creating a daily beverage with a distinctive flavor and health properties that enjoys stable consumer demand [6,7]. Therefore, in the context of developing health beverages, the quality of dried S. baicalensis slices is of paramount importance. While it is also widely used in extracts, capsules, and medicines, its use as a directly infused tea represents one of its primary market forms. Against this backdrop, the post-harvest drying process becomes a critical step in ensuring product quality. An optimized drying technique is crucial for maximizing the retention of functional active components, developing pleasant sensory characteristics, and extending shelf life [8,9].

Traditional drying methods for S. baicalensis primarily include sun drying, hot-air drying, and kiln drying [10,11,12]. Natural sun drying, though low-cost, is highly dependent on weather conditions, has a lengthy cycle, and is susceptible to microbial and environmental contamination. Precise control of drying conditions is difficult, often resulting in darkening of the herbal material and loss of active components due to photooxidation or enzymatic degradation. Hot-air drying and oven drying offer higher efficiency and greater controllability, yet they commonly involve high temperatures and prolonged durations. This can cause degradation of heat-sensitive flavonoids in S. baicalensis, leading to reduced medicinal efficacy [13,14]. At the same time, these methods are energy-intensive, have low thermal efficiency, and result in uneven drying, often causing surface hardening or deformation. They struggle to meet the modern Chinese herbal medicine industry’s demand for high-quality, energy-efficient, and environmentally friendly drying processes [15,16].

In contrast, microwave vacuum drying (MVD) technology, as a novel combined drying method, has demonstrated significant advantages due to its high efficiency, energy savings, and low-temperature drying characteristics [17,18]. MVD combines the volumetric heating of microwaves with the boiling point depression effect in a vacuum environment, enabling rapid and uniform dehydration of materials at low temperatures. During the drying process of blueberry pomace, MVD yielded the highest levels of total phenolics, total anthocyanins, and total sugars [19]. Comparative studies on Chinese yam indicate that MVD preserves color well and maintains a high retention rate of bioactive components [20]. The tray-rotary microwave vacuum dryer (TMVD), in particular, enhances drying uniformity through continuous rotation of the material pallets, preventing localized overheating and significantly improving thermal efficiency and drying quality. Previous studies have reported that this technology significantly reduces drying time compared to traditional hot-air drying when processing Chinese medicinal materials such as Angelica sinensis [21], while better preserving active components like saponins, polysaccharides, and vitamins, demonstrating broad application prospects. Additionally, this technology has garnered significant attention in the food industry, having been successfully applied to the drying of fruits and vegetables such as apples, strawberries, and longan [22], edible fungi [23], and functional food ingredients [24]. It effectively preserves the nutritional content, natural color, and flavor of the products. Therefore, this study systematically employs TMVD technology for the drying of S. baicalensis, focusing on achieving the following objectives: systematically investigating the optimal combination of key parameters such as temperature, vacuum level, and rotational speed; clarifying the influence patterns of the TMVD process on the retention rate of S. baicalensis primary active constituents; and establishing a sensory evaluation system to elucidate the differences between TMVD-dried products and conventionally dried products in terms of flavor characteristics and consumer acceptance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials and Methods

Fresh S. baicalensis root was procured from a standardized cultivation base in Longxi County, Dingxi City, Gansu Province, China (geographic coordinates: 35.0136° N, 104.6452° E). The initial moisture content was determined by the oven drying method at 105 °C until reaching a constant weight. The initial moisture content of the root was determined to be 0.615 ± 0.005 kg/kg (dry basis). After washing, (200 ± 1) g of the rhizome was weighed and cut into uniform 4 mm-thick slices using an industrial herbal slicing machine (Model HQ-300, Hangzhou Traditional Chinese Medicine Equipment Co., Ltd., Hangzhou, China; slicing accuracy ± 0.05 mm).

2.2. Experimental Reagents

The reference standards used in the experiment, including baicalin, wogonoside, baicalein, and wogonin, were purchased from Shanghai Titan Scientific Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Folin–Ciocalteu reagent, 1,1-diphenyl-2-pyridinehydrazine (DPPH), catechin, ascorbic acid, and cresol were all of analytical grade. Acetonitrile used for high-performance liquid chromatography was of chromatographic grade, while methanol and ethanol were both of analytical grade. These reagents were purchased from Shanghai Yuanye Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

2.3. Experimental Equipment

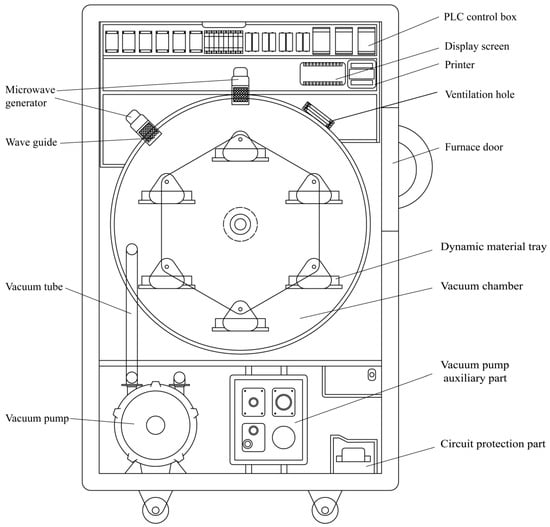

A tray-rotating microwave vacuum dryer (TMVD) was employed for the drying treatments. The total power of the apparatus was 6.6 kW, with a microwave generator power of 3 kW. The vacuum range was adjustable from −60 to −80 kPa, and the rotation speed was variable. The microwave generator was located at the top of the drying chamber, which was equipped with six sets of rotating racks with a rotation diameter of 500 mm. Supporting instruments included a CM-700d spectrophotometer (Konica Minolta, Tokyo, Japan), a CPA225D analytical balance (Sartorius, Göttingen, Germany), an SD20 pH meter (Toledo Instruments, Shanghai, China), a TS-200B constant-temperature shaker (Jinwen Instruments, Ningbo, China), a TGL 20M high-speed centrifuge (Meijia Sen Instruments, Shenyang, China), a TA-XT plus Texture Analyzer (Stable Micro Systems, Godalming, UK), a T2600S UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Jingcheng Instruments, Tianjin, China), a TL2310 turbidimeter (Hach, Loveland, CO, USA), a 1200 Liquid Chromatograph (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA), and an S-4800N scanning electron microscope (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic of the tray-rotating microwave vacuum dryer.

2.4. Experimental Setup

The slices were placed in a TMVD apparatus, with automatic weighing system recordings taken every 5 min. Natural air-drying and hot-air drying served as controls. The hot-air drying used as a control in this study was conducted in a constant-temperature air-drying oven set at 60 °C with an air velocity of 1.5 m/s. The samples were dried to a safe moisture content similar to the TMVD experimental groups (approximately 0.1 g/g, dry basis), which required about 240 min. All experiments were performed in triplicate to ensure the reliability of the data. Based on extensive preliminary trials, the effects of different process parameters on the drying characteristics and quality of S. baicalensis slices were systematically investigated. The experimental factors included drying temperature (40 °C, 45 °C, 50 °C), vacuum level (−65 kPa, −70 kPa, −75 kPa), and rotation speed (3.7 rad/s, 4.2 rad/s, 4.7 rad/s). All drying experiments were performed with a slice thickness of 4 mm, using natural air-drying and traditional hot-air drying as control treatments. The dried S. baicalensis slices were subjected to sensory evaluation under specific infusion conditions: specifically, 5 g of dried S. baicalensis root slices were weighed, infused with 300 mL of water at 75 °C for 5 min, and then the infusion process was completed.

2.5. Drying Kinetic Parameters

2.5.1. Moisture Content

Calculate the material’s moisture content using the formula [25], the equilibrium moisture content was determined as the value at which no further weight loss was observed after 24 h of drying under the same conditions:

Among these, MR denotes the moisture content during the sample drying process; Mt represents the dry basis moisture content of the material at any given time t (g/g); Me indicates the moisture content of the material at equilibrium (g/g); M0 signifies the initial dry basis moisture content of the material (g/g).

2.5.2. Dry-Basis Moisture Content

The following equation [26] was employed to calculate the dry-basis moisture content:

where Wt denotes the sample mass at time t in grams, and Wd denotes the mass after drying in grams.

2.5.3. Drying Rate

Calculate the drying rate of the dried sample using the formula [25]:

DR denotes the drying rate of the sample during the drying process, g/(g·min); Mt1 and Mt2 represent the dry-basis moisture content of the sample at time points t1 and t2, respectively, (g/g).

2.6. Effective Moisture Diffusion Coefficient

The drying process follows Fick’s second law of diffusion. For thin-film samples, the moisture ratio over time satisfies Equation [27]. The application of this analytical solution is based on the following assumptions: uniform initial moisture distribution; negligible external resistance to mass transfer; one-dimensional moisture diffusion; constant effective diffusivity and temperature during drying; and negligible material shrinkage:

Deff represents the effective moisture diffusion coefficient, describing the migration rate of moisture within the material, in m2/s; L denotes half the characteristic thickness of the sample, in meters; t indicates the drying time, in seconds; n signifies the order term (where n = 0, 1, 2, …). Due to the rapid convergence of the series, when the dominant term is taken as n = 0, the formula simplifies to a linear form:

2.7. Specific Energy Consumption (SEC)

Calculate the specific energy consumption in the microwave vacuum based on the energy consumption assessment model proposed by Jahanbakhshi et al. [16]:

Here, SEC denotes specific energy consumption (kWh/kg), Ptotal represents the sum of microwave power and vacuum pump power (kW), t denotes drying time (h), and mwater denotes the mass of water removed (kg).

2.8. Color Difference

Among these, the total color difference change (ΔE) is one of the most direct indicators for measuring the apparent quality of materials [21]:

Here, L* denotes lightness, a* denotes redness, and b* denotes yellowness; L, a, and b represent the initial lightness, redness, and yellowness of the sample. L0, a0 and b0 represent the lightness, redness and yellowness of the fresh sample, respectively.

2.9. Texture and Chemical Properties

2.9.1. Hardness and Brittleness

The hardness and brittleness of the dried S. baicalensis roots were determined using a texture analyzer equipped with a P/25 flat-bottom probe [28]. The analysis was conducted with the following parameters: a pre-test speed of 2 mm/s, a test speed of 0.03 mm/s, a post-test speed of 10 mm/s, and a compression rate of 30%.

2.9.2. pH Value

The pH value of the tea infusion prepared from S. baicalensis slices was measured using an SD20 pH meter [29].

2.9.3. Turbidity

Turbidity was directly measured using a TL2310 turbidimeter for S. baicalensis slices infused in tea liquor. Results were expressed in NTU (Nephelometric Turbidity Units). Higher NTU values indicate greater turbidity of the tea liquor [28].

2.10. Chemical Quality

For the analysis of chemical components, 1 g of dried and powdered S. baicalensis root was extracted with 75% ethanol in a 50 mL beaker. The mixture was shaken in the dark for 24 h and then centrifuged at 360 r/min for 30 min under constant-temperature shaking conditions [21]. The resulting supernatant was collected for subsequent determinations.

2.10.1. Determination of Total Phenolic Content

The total phenolic content was determined using the Folin–Ciocalteu method. Briefly, 0.03 mL of the extract was mixed with 4.0 mL of 10% (v/v) Folin–Ciocalteu’s reagent, followed by the addition of 2.0 mL of 7.5% (w/v) sodium hydroxide solution. The mixture was vortexed for 10 min and then incubated in a 50 °C water bath in the dark for 1 h. The absorbance was measured at 765 nm using a spectrophotometer, with acidified methanol serving as the blank. TPC was expressed as milligrams of gallic acid equivalent per gram of dry weight (mg GAE/g DW) [21]. All determinations were performed in triplicate.

2.10.2. Total Flavonoid Content Determination

The total flavonoid content was analyzed by the NaNO2-AlCl3-NaOH method [19]. In this procedure, 3.2 mL of the extract was combined with 8.0 mL of distilled water and 1.2 mL of 5% (w/v) sodium nitrite (NaNO2). The solution was shaken for 10 min, after which 0.6 mL of 10% (w/v) aluminum chloride (AlCl3) was added. After another 10 min of shaking, 4.0 mL of 1 mol/L sodium hydroxide (NaOH) was added to terminate the reaction. The absorbance was read at 510 nm against a blank prepared with the NaNO2-AlCl3-NaOH solution. All analyses were carried out in triplicate.

2.10.3. Antioxidant Activity Assay

The antioxidant activity was evaluated using the DPPH (1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl) radical scavenging assay [30]. An appropriate volume of the extract was added to 6.0 mL of a 1 mmol/L DPPH methanol solution. The mixture was shaken at room temperature in the dark for 60 min, and the absorbance was then measured at 515 nm.

2.10.4. Polysaccharide Content Determination

The polysaccharide content was determined by the sulfuric acid-phenol method. Specifically, 0.02 mL of the extract [30] was mixed with 4.0 mL of 9% (v/v) phenol solution. After thorough mixing, 12.0 mL of concentrated sulfuric acid (H2SO4) was added rapidly. The mixture was shaken vigorously for 10 min and allowed to react at room temperature for 60 min. The absorbance was measured at 485 nm against a blank solution prepared without the sample. All measurements were performed in triplicate.

2.10.5. Active Constituents

The contents of baicalin, wogonin, baicalein, and wogonoside in S. baicalensis were determined using high-performance liquid chromatography [31]. The analysis was performed on an Agilent 1200 liquid chromatography system equipped with a DAD detector. A reversed-phase C18 column was used with a gradient elution of 0.1% formic acid in water and acetonitrile. The gradient program was 0–10 min, 20–40% acetonitrile; 10–15 min, 40–60% acetonitrile; 15–20 min, 60–20% acetonitrile. The flow rate was set at 0.8 mL/min, the column temperature was maintained at 30 °C, and the detection wavelength was 280 nm. The injection volume was 10 μL. All target components were well separated under these chromatographic conditions and quantified using the external standard method.

2.11. Microscopic

After fixation with 3.0% glutaraldehyde for 4 h, samples were dehydrated through a graded ethanol series (30%, 50%, 70%, 90%, 100%), critical-point-dried, sputter-coated with gold, and then observed and imaged using scanning electron microscopy at an accelerating voltage of 10 kV [27].

2.12. Sensory Evaluation

The sensory evaluation phase involved 70 trained sensory evaluators (aged 18–45, with equal representation of men and women). All evaluators passed taste sensitivity tests (e.g., basic taste recognition thresholds) and received specialized training prior to the experiment to familiarize themselves with the evaluation procedures and scaling methods. Evaluations were conducted in a standardized sensory evaluation room. Samples were presented in a randomized order using three-digit random codes, with water rinses between each evaluation. The sensory evaluation phase employed a 10-point scale for quantitative assessment (lower scores indicating lower sensory acceptability). Six core evaluation metrics were established: aroma intensity, bitterness intensity, aftertaste, tea liquor color, overall acceptability, and flavor persistence of S. baicalensis tea liquor.

2.13. Hierarchical Cluster Analysis and Correlation Network Analysis Heatmaps

To characterize sample similarities and the global correlation structure among indicators, we combined hierarchical clustering heatmaps with a Mantel-based association network.

Hierarchical clustering (HCA): After Z-score standardization of all variables, bidirectional clustering (samples × indicators) was performed in Origin 2025b using Euclidean distance and the minimum-distance (single-linkage) method; results were visualized as heatmaps with standardized values.

Correlation matrix: Pairwise linear relationships were summarized by Pearson correlation coefficients (r) with significance markers (“*, **, ***” for p < 0.05, 0.01, 0.001; FDR-adjusted), displayed as a lower-triangle heatmap.

Mantel association network: To evaluate subsystem-level/global associations, Euclidean distance matrices were constructed for indicator sets and tested via Mantel correlation (Mantel’s r) in R 4.4.3 (key packages: vegan, igraph, ggplot2), using 9999 permutations. p-values were adjusted for multiple testing by the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure (FDR), with significance set at p < 0.05. In the network, edge width is proportional to Mantel’s r (association strength), edge color encodes significance, and node size reflects degree. Unless otherwise specified, the correlation matrix is interpreted for “pairwise” relationships, whereas the Mantel network is used to infer “global/subsystem-level” couplings.

2.14. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS 22.0 statistical software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), Origin 2025b software (OriginLab Corp., Northampton, MA, USA), and Microsoft Excel 2024 (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA). All results are presented as the mean ± standard deviation from three independent replicate experiments. Statistical comparisons between treatment groups were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), with Tukey’s HSD test for post hoc analysis. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Drying Characteristics

3.1.1. Effect of TMVD Drying at Different Temperatures on Drying Characteristics

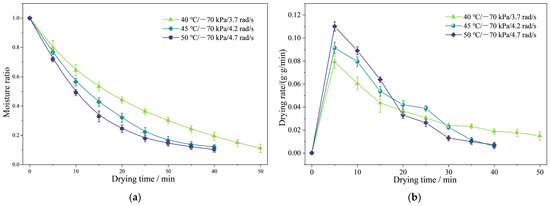

Under conditions of 4 mm slice thickness, −70 kPa vacuum pressure, and 4.2 rad/s tray rotation speed, the drying characteristic curves of S. baicalensis at different radiation temperatures are shown in Figure 2. As the radiation temperature increases, the time required for S. baicalensis to reach safe moisture content gradually decreases. At 40 °C, drying to safe moisture content took 50 min; at 45 °C, this time shortened to 40 min. At 50 °C, it also took approximately 40 min, but exhibited a faster drying rate in the later stages compared to 45 °C. Compared to the 40 °C baseline, the total drying time at 45 °C and 50 °C decreased by 20.0%. This is primarily because vacuum drying enables moisture evaporation at lower temperatures. The input of thermal energy augments the vapor pressure gradient, increasing the kinetic energy of water molecules and promoting their transport via evaporation and diffusion. Consequently, heat transfer rates accelerate, shortening the drying time. Similar phenomena have been reported in microwave vacuum drying of carrot slices [32]. Furthermore, the small reduction in total drying time when the temperature increased from 45 °C to 50 °C is consistent with findings from microwave-hot air combined drying of S. baicalensis. Excessive temperature did not further shorten drying time and could reduce quality [27]. Upon microwave irradiation, the absorbed energy weakens the intermolecular forces of bound water and disrupts its internal chemical bonds. This converts part of the bound water within cells into more mobile free water, reducing internal diffusion resistance and improving mass and heat transfer efficiency [33]. Notably, increasing the drying temperature from 45 °C to 50 °C did not significantly shorten the drying time. According to the literature, this may be due to structural changes in the samples caused by higher temperatures, such as increased tissue shrinkage and surface hardening [29,34]. These structural alterations could increase the resistance to internal moisture migration, thereby partially offsetting the promotive effect of temperature elevation on the drying rate.

Figure 2.

Moisture ratio (a) and drying rate (b) of Scutellaria baicalensis at different temperatures.

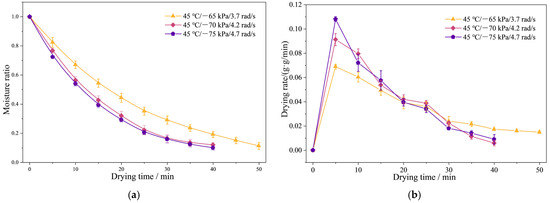

3.1.2. Effect of TMVD Drying at Different Vacuum Levels on Drying Characteristics

Under drying conditions of 45 °C temperature, 4 mm slice thickness, and 4.2 rad/s rotation speed, the drying characteristic curves of S. baicalensis at different vacuum levels (−65 kPa, −70 kPa, −75 kPa) are shown in Figure 3. Drying time exhibited a trend of first decreasing and then increasing with vacuum level. At −65 kPa, the time to reach safe moisture content was approximately 50 min, while at −70 kPa and −75 kPa, this time was reduced to 40 min. Compared to −65 kPa, drying time decreased by about 20% at −70 kPa and −75 kPa. Compared to −65 kPa, drying times were reduced by approximately 20% under conditions of −70 kPa and −75 kPa. This non-linear trend shows a synergistic effect between vacuum level and microwave energy. Higher vacuum levels lower the boiling point of water, which promotes faster internal vaporization. This phenomenon aligns with the trend observed by Zang et al. [19] during microwave vacuum drying of Angelica sinensis. Concurrently, the volumetric heating characteristic of microwave energy instantaneously generates substantial water vapor within the material, creating a pronounced vapor pressure gradient that accelerates moisture migration [35,36]. However, when the vacuum level is further increased to −75 kPa, the improvement in drying rate tends to level off. Similarly, Taskin et al. [37]. This phenomenon was also observed during microwave vacuum drying of pears. It may be related to changes in the mass transfer boundary layer and the restriction of internal vapor escape pathways [37]. As vacuum pressure decreases, air pressure within the sealed chamber diminishes, lowering the saturated vapor pressure of water. Under identical heating conditions, this facilitates easier moisture removal from the material. However, when vacuum pressure drops to −75 kPa, drying rate improvement becomes negligible. This may be due to the significantly reduced air density at very high vacuum levels, which weakens convective heat transfer. At the same time, premature surface hardening may increase resistance to internal moisture transport [37].

Figure 3.

Moisture ratio (a) and drying rate (b) of Scutellaria baicalensis at different vacuum levels.

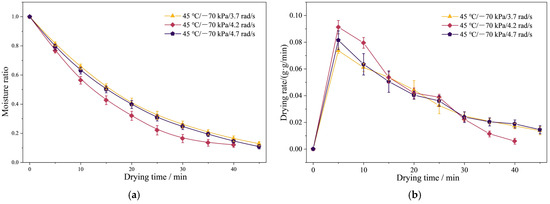

3.1.3. Effect of TMVD Drying at Different Rotational Speeds on Drying Characteristics

The effect of different tray rotation speeds (3.7 rad/s, 4.2 rad/s, 4.7 rad/s) on the drying process of S. baicalensis at a drying temperature of 45 °C and a vacuum level of −70 kPa is shown in Figure 4. Experimental data show that drying to the safe moisture content takes 45 min at 3.7 rad/s and 4.7 rad/s, but only 40 min at 4.2 rad/s. Compared to 3.7 rad/s, drying time decreases by 11.1% at 4.2 rad/s, while drying time at 4.7 rad/s remains the same as at 3.7 rad/s. The improvement in drying efficiency when the rotation speed was increased to 4.2 rad/s primarily resulted from the optimized heat distribution effect achieved by tray rotation. This mechanical motion effectively prevented localized overheating within the microwave field, ensuring uniform heating across all material surfaces. It also reduced the shielding effect, promoting drying uniformity. The existence of an optimal rotation speed is common in rotary drying systems. For example, in double-cone rotary vacuum dryers, an appropriate rotation speed is crucial for maintaining good particle mixing and heat transfer, while excessively high speeds can reduce drying efficiency and potentially cause particle attrition [30]. However, drying efficiency did not improve further at 4.7 rad/s. This may be due to excessively high rotational speeds reducing the material’s residence time in the microwave field, which lowers the microwave energy absorbed per rotation cycle [38]. Simultaneously, overly high speeds may disrupt the kinetic process of internal moisture migration outward, diminishing coordination between surface evaporation and internal diffusion [38,39]. The combined effect of these factors might undermine the positive effects expected from increased rotational speed. This undermines the positive effects of increased rotational speed [39]. This phenomenon suggests an optimal rotational speed threshold (4.2 rad/s), beyond which mechanical benefits no longer increase, showing a non-linear relationship between rotational speed and drying efficiency.

Figure 4.

Moisture ratio (a) and drying rate (b) of Scutellaria baicalensis at different rotational speeds.

3.2. Effective Moisture Diffusion Coefficient

The Deff data for S. baicalensis dried via microwave vacuum drying are presented in Table 1 The effects of different drying conditions on moisture migration efficiency and their underlying mechanisms are as follows: Increased temperature significantly raises Deff values by enhancing the thermal energy of water molecules, weakening hydrogen bonds, and reducing cell sap viscosity, which promotes capillary diffusion [40]. Increased vacuum pressure also significantly raises the effective water diffusion coefficient. This occurs because high vacuum reduces the latent heat required for water phase transition, amplifies the vapor pressure gradient between the material interior and the environment, and diminishes vapor boundary layer resistance [41]; Increasing the turntable speed elevates Deff from 3.12 × 10−10 m2/s to 3.76 × 10−10 m2/s. Centrifugal force promotes surface water redistribution, disrupting retained water films, while rotational inertia expands microchannels within the material (reducing diffusion path tortuosity). All experimental groups exhibited good model fitting quality (R2 ≥ 0.9757), with the highest reaching 0.9998, indicating that the experimental data align well with the simplified model based on Fick’s second law of diffusion [27]. However, it should be noted that this model relies on assumptions such as a constant effective diffusion coefficient and neglects effects like sample shrinkage, which may introduce some discrepancies from the actual drying process. The Deff values obtained in this study (2.46 × 10−10 to 3.91 × 10−10 m2/s) fall within the range reported for typical agricultural products undergoing microwave vacuum drying but are generally higher than those for conventional hot-air drying. For instance, Alaei [41] reported Deff values of 1.12 × 10−10 to 2.98 × 10−10 m2/s for nectarine dried under near-infrared vacuum conditions. The increased Deff in TMVD is due to the combined effect of volumetric microwave heating and the vacuum environment, both of which facilitate moisture migration. Parameter interaction effects manifested as follows: when temperature and vacuum were synergistically increased, Deff exhibited an additive effect (+36.2% relative to the baseline group) [21], attributable to concurrent optimization of thermodynamic driving forces and phase transition conditions. Conversely, increasing rotational speed compensated for low-temperature/low-pressure conditions, raising Deff by 52.8%. This confirms that mechanical forces can partially compensate for insufficient thermal energy.

Table 1.

Effective moisture diffusion coefficients of different drying groups.

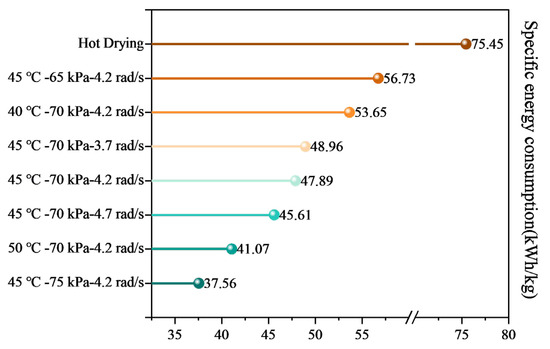

3.3. Energy Consumption Ratio

As shown in Figure 5, the energy—efficiency optimization and thermodynamic rationale for microwave vacuum drying of S. baicalensis can be summarized as follows. The SEC decreased significantly with increasing temperature, primarily due to the enhanced effective moisture diffusion coefficient and shortened drying time at higher temperatures. Increasing the vacuum level to −75 kPa further reduced the SEC, benefiting from the reduced boiling point that decreased the sensible heat input required for water phase change [34]. Higher tray rotation speeds improved thermal uniformity and promoted surface moisture removal via centrifugal effects [42]. Compared with conventional hot-air drying, microwave vacuum drying achieved the lowest SEC of 37.56 kWh/kg at 45 °C/−75 kPa/4.2 rad/s, corresponding to a 50.96% energy-saving rate. This result is consistent with the hypothesized synergistic mechanism where microwave energy couples directly with water molecules under reduced pressure [17].

Figure 5.

Energy consumption ratio under different drying conditions.

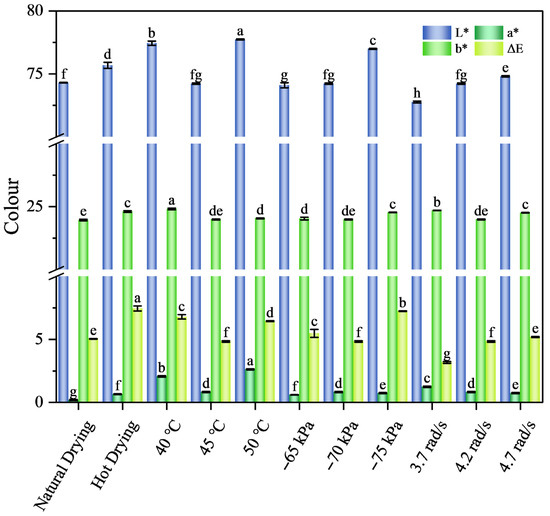

3.4. Color Difference

Analysis of color difference data from microwave vacuum drying of S. baicalensis, as shown in Figure 6, indicates that each parameter exerts a systematic influence on the material’s color characteristics. Among temperature variables, the L* value exhibits an increasing trend with rising temperature, with a 4.72% improvement at 50 °C compared to 45 °C. This increase in lightness at higher temperatures has been observed in other microwave-vacuum-dried plant materials and may be attributed to more rapid moisture removal reducing the time for enzymatic browning reactions [43]. Changes in the a* value indicate that higher temperatures promote reddening [43], with a 27.1% increase at 50 °C compared to 40 °C. Vacuum level analysis reveals that the ΔE value for the −75 kPa group is higher than that for the −70 kPa and −65 kPa groups, with increases of 49.8% and 32.3%, respectively. The greater color difference under higher vacuum conditions may result from intensified Maillard reaction rates due to the concentration effect during rapid drying, as similarly reported in vacuum-dried herbal products [40]. Simultaneously, the b* value for this group increased by 2.3% compared to the −70 kPa group. When the rotation speed was increased to 4.2 rad/s, the b* value rose to 24.52 ± 0.02, but the ΔE value simultaneously increased to 5.19 ± 0.05, representing a 63.1% increase compared to the 3.7 rad/s group. The a* value in the 3.7 rad/s group was the lowest across the rotation speed gradient. Control group data showed that ΔE values for hot-air drying were significantly higher than those for natural drying. Its b* values were also generally higher than those of the microwave group. The generally lower color differences in TMVD samples compared to hot-air drying are consistent with findings by Zang et al. [21], who attributed this to shorter exposure to thermal stress and the oxygen-deficient environment in microwave-vacuum drying. Notably, under 45 °C/−70 kPa conditions, the L* value difference between the 3.7 rad/s group and the 4.2 rad/s group was 0.78%, but the former’s ΔE value was 6.7% lower than the latter’s. Standard deviation analysis across parameter groups indicated that vacuum level variation caused the greatest fluctuation in ΔE values, while temperature changes most significantly impacted the stability of a* values.

Figure 6.

Color difference in Scutellaria baicalensis under different drying conditions. Different lowercase letters above the bars (or on top of the data points) indicate statistically significant differences between groups (p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD post-hoc test).

3.5. Physical and Chemical Properties

Under different drying methods and process conditions, the physical properties of S. baicalensis slices exhibited significant variations (Table 2). Products from hot-air drying showed the highest hardness and relatively higher brittleness, while naturally dried samples had the lowest hardness and brittleness. Among the MVD groups, temperature significantly affected hardness. With fixed vacuum and rotation speed, increasing temperature from 40 °C to 50 °C caused hardness to increase sharply from 4.48 ± 0.13 to 7.46 ± 0.18, nearing hot-air-dried levels. This trend of increasing hardness with temperature aligns with observations in microwave-vacuum drying of Angelica sinensis, where higher temperatures promoted more pronounced tissue contraction [21]. This is presumed to result from accelerated tissue contraction and structural densification at higher temperatures. Brittleness reached its optimum at 45 °C/−70 kPa/4.2 rad/s. Further increasing the vacuum to −75 kPa (45 °C, 4.2 rad/s) significantly increased brittleness, possibly due to more intense moisture removal promoting the formation of a porous brittle structure [44]. Similar vacuum-dependent brittleness changes have been reported in microwave-vacuum-dried fruits, where lower pressure conditions created more pronounced porous networks [37]. Rotational speed significantly influenced brittleness: reducing speed from 4.2 rad/s to 3.7 rad/s or increasing it to 4.7 rad/s both markedly decreased brittleness. This indicates that 4.2 rad/s facilitates uniform heating and mechanical processing, thereby promoting brittle structure formation. Regarding pH, all dried samples exhibited higher pH values than the natural drying group, with an upward trend as the drying temperature increased. The highest pH was observed under the 50 °C/−70 kPa/4.2 rad/s conditions. According to the literature, this phenomenon could be due to chemical changes during drying, such as the volatilization or degradation of acidic components, or the formation of Maillard reaction products [38,43]. Turbidity results showed that microwave vacuum drying yielded tea liquor with lower turbidity, with the lowest value observed at 45 °C/−70 kPa/4.2 rad/s. This performance was significantly better than that of natural drying and hot-air drying. Based on this, we speculate that microwave vacuum drying may contribute to a clearer tea liquor by reducing the leaching of macromolecular substances like polysaccharides and proteins. This speculation is consistent with reports in the literature regarding the effects of microwave treatment on cellular structure [22].

Table 2.

Physical properties of different drying groups.

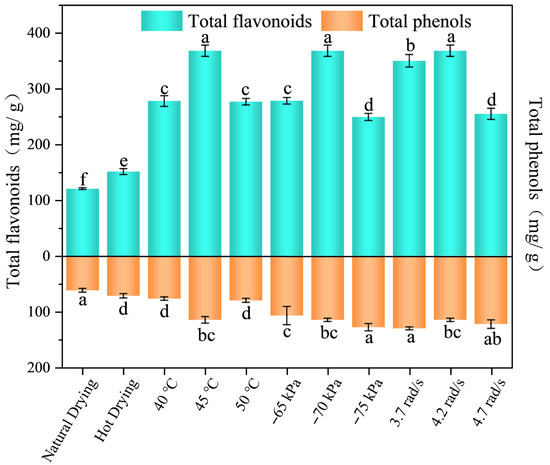

3.6. Total Phenols and Total Flavonoids

The total flavonoid and total phenolic content data of S. baicalensis dried products are shown in Figure 7. The retention efficiency of active components and the influencing mechanisms of parameters can be described as follows: Total flavonoid content peaked at 45 °C/−70 kPa/3.7 rad/s, significantly exceeding natural drying levels. This optimal temperature range for flavonoid preservation aligns with the observations by Liu et al. [14] in S. baicalensis drying, who also reported maximum flavonoid retention at moderate drying temperatures. This was mainly due to the synergistic thermal effects of microwave-vacuum treatment. The rapid volumetric heating from microwaves promoted internal moisture vaporization within cells, possibly combined with enhanced component dissolution through electromagnetic field interactions with cell membranes [45]. Meanwhile, the moderate treatment temperature (45 °C) effectively prevented glycosidic bond cleavage, which might occur at higher temperatures (50 °C). Total phenolic content peaks under −75 kPa high vacuum, driven by vacuum-shortened drying time. The enhanced phenolic preservation under high vacuum conditions is consistent with the research findings by García et al. [45] in herbal drying, who demonstrated that reduced oxygen exposure effectively inhibits oxidative degradation of phenolic compounds. Parameter interactions reveal threshold effects: total flavonoids in the 50 °C/−75 kPa group fall below those in the 45 °C/−70 kPa group, as elevated temperature accelerates drying but induces thermal degradation. This trade-off between drying efficiency and component retention corresponds to the reports by Bai et al. [15]. in the thermal processing of Chinese medicinal materials. Meanwhile, a 3.7 rad/s rotation speed at −70 kPa achieves dual optimization of total flavonoids and total phenolics, indicating that moderate mechanical force balances component extraction with enzyme inactivation. All microwave-vacuum groups showed significantly higher active ingredient retention rates than conventional hot-air drying. This result is consistent with literature reports on the protective effects of microwave heating and vacuum-induced low-oxygen environments on heat-sensitive components [17].

Figure 7.

Total flavonoids and total phenols content of dried Scutellaria baicalensis under different conditions. Different lowercase letters above the bars (or on top of the data points) indicate statistically significant differences between groups (p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD post-hoc test).

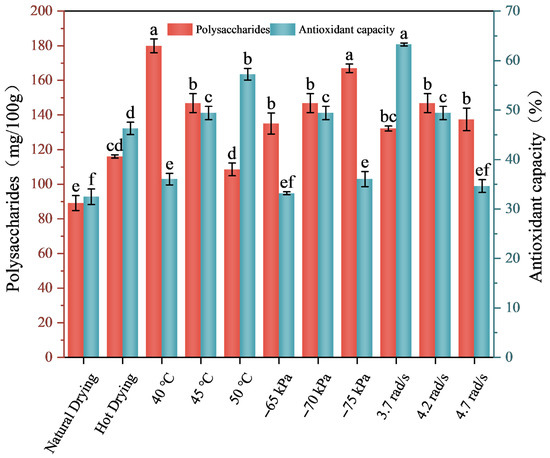

3.7. Polysaccharides and Antioxidant Properties

Based on the polysaccharide content and antioxidant activity data of S. baicalensis dried products (Figure 8), their retention patterns and parameter mechanisms can be summarized as follows: Polysaccharide content peaked at 40 °C (179.91 ± 4.02 mg/g), representing a 101.9% increase compared to natural drying (89.13 ± 4.33 mg/g). The better polysaccharide preservation at lower temperatures agrees with the observations by Zhang et al. [46]. In medicinal plant drying, it was found that mild thermal conditions better preserve polysaccharide structural integrity. This was attributed to low temperatures slowing the thermal degradation of polysaccharide chains, while vacuum conditions suppressed oxidative degradation [46,47]. Antioxidant activity peaked at 50 °C, where higher temperatures promoted the dissolution of phenolic compounds [48,49], which correlated with total phenolic data. However, this was accompanied by a decrease in polysaccharide content (108.59 ± 3.72 mg/g), indicating that preserving heat-sensitive components requires balancing temperature thresholds. The inverse trend between polysaccharide content and antioxidant activity at different temperatures is consistent with thermal stability studies of various plant active compounds [50]. Increasing vacuum pressure from −65 kPa to −75 kPa elevated polysaccharide content from 135.06 ± 6.09 mg/g to 167.00 ± 2.47 mg/g. Compared to conventional hot-air drying, microwave vacuum drying at 45 °C/−70 kPa/3.7 rad/s synergistically optimized polysaccharide content (146.88 ± 5.47 mg/g) and antioxidant activity (49.39 ± 1.34%). Leveraging the dual advantages of targeted electromagnetic field heating and an oxygen-depleted environment, surpassing hot-air drying (116.03 ± 0.93 mg polysaccharides, 46.29 ± 1.24% antioxidant activity).

Figure 8.

Scutellaria baicalensis polysaccharides and antioxidant activity under different treatment conditions. Different lowercase letters above the bars (or on top of the data points) indicate statistically significant differences between groups (p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD post-hoc test).

3.8. Analysis of Active Ingredient Content

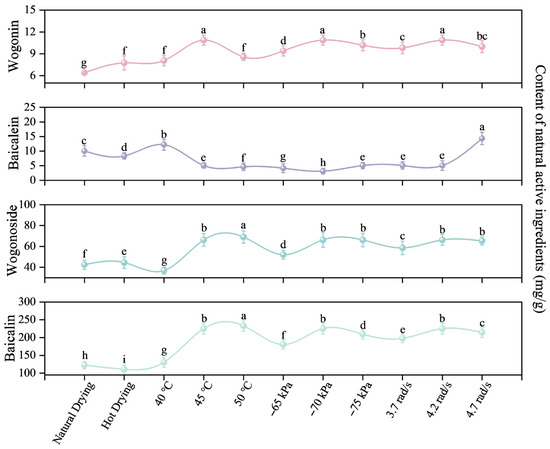

The effects of different drying methods and microwave vacuum process parameters on the four major flavonoid components of S. baicalensis revealed distinct responses among the active compounds to treatment conditions (Figure 9). Compared to natural drying and hot-air drying, microwave vacuum drying significantly increased the content of baicalin and wogonoside, particularly under the 45–50 °C treatment conditions, where baicalin content rose to 225.22–233.02 mg/g, while wogonoside reached 66.31–69.07 mg/g. This suggests that moderate temperature elevation may promote the conversion or retention of these compounds. Baicalein and wogonin showed distinct response patterns, reaching maximum values at 4.2 rad/s rotation speed (baicalein: 14.35 mg/g; wogonin: 9.98 mg/g). However, their levels were generally lower than those in naturally dried samples under most microwave-vacuum conditions, reflecting their differing thermal sensitivity and transformation pathways. Vacuum pressure also exhibited discernible patterns: most components reached higher concentrations at −70 kPa, while increasing vacuum to −75 kPa caused partial declines in certain components, indicating that moderate vacuum conditions favor the stability of target compounds. Increased rotation speed partially promoted baicalin content elevation, though its effect on other components was inconsistent. Collectively, these results demonstrate that microwave vacuum drying significantly influences the retention and transformation of different flavonoid components in S. baicalensis by adjusting temperature, vacuum pressure, and rotation speed. The response behavior of each component exhibits strong condition dependency and specificity, providing a theoretical basis for optimizing S. baicalensis drying processes.

Figure 9.

Chemical Constituent Content of Scutellaria baicalensis under Different Treatment Conditions. Different lowercase letters above the bars (or on top of the data points) indicate statistically significant differences between groups (p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD post-hoc test).

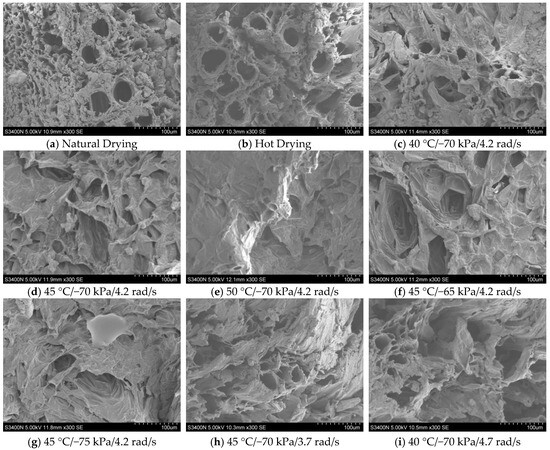

3.9. Microstructure

Analysis of the microstructural characteristics of S. baicalensis dried products based on scanning electron microscopy observations indicates (Figure 10) that different drying methods significantly affect cellular and surface morphology. Naturally dried samples exhibit a typical porous structure with intact air pores. The slow dehydration process allowed for gradual water gradient release, forming continuous vapor escape channels. The hot-air-dried group showed the least surface wrinkling, but localized densification areas were visible. This was attributed to high temperatures causing epidermal protein denaturation and hardening, which inhibited overall shrinkage but impeded internal water diffusion. Microwave vacuum drying consistently produced wrinkling and structural collapse across all groups, with severity closely correlated to process parameters [19]. The 40 °C/−70 kPa group exhibited partial cell wall collapse forming shallow pits, attributed to insufficient vacuum pressure differential driving force at low temperatures; samples dried at 50 °C/−70 kPa conditions exhibited more pronounced shrinkage and structural collapse as observed via SEM. These morphological changes are closely related to the more intense moisture migration and rapid dehydration process under high-temperature conditions [34]. Notably, the 3.7 rad/s group exhibited collapsed pores but in smaller numbers, while the 4.2 rad/s and 4.7 rad/s groups displayed curled porous structures, indicating mechanical force influences pore collapse. In summary, the open-channel structure of naturally dried samples explains their stable drying characteristics. The epidermal hardening from hot-air drying results in a tough texture, while the wrinkling and collapse in microwave-vacuum-dried samples are directly related to rapid dehydration stresses.

Figure 10.

Microstructure images of Scutellaria baicalensis under different treatment conditions.

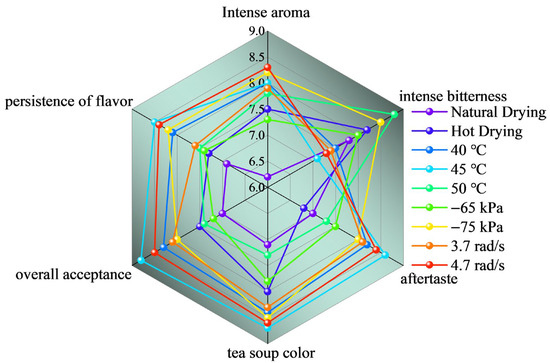

3.10. Evaluation Results

Analysis of physical test and sensory evaluation data for S. baicalensis slices steeped in water under different drying conditions reveals correlation trends between parameter variations and respective indicators (Figure 11). Further exploration of the sensory evaluation results demonstrates that the optimal sensory profiles obtained under 45 °C/−70 kPa/4.2 rad/s conditions correlate strongly with key physicochemical parameters. The highest overall acceptability score (8.8) corresponds to significantly higher baicalin content (225.22 mg/g) and lower turbidity (12.4 NTU), establishing a clear relationship between consumer preference and measurable quality attributes. This analysis confirms that optimal TMVD processing improves both sensory acceptance and the preservation of bioactive components. It provides useful guidance for producing consumer-preferred S. baicalensis products with high quality. Regarding physical properties, pH values fluctuated between 6.35 and 7.15 across conditions, with the natural drying group exhibiting the lowest pH (6.35) and the 50 °C/−70 kPa/40 r/min group showing the highest pH (7.15). Turbidity measurements revealed the highest turbidity in tea liquor from the natural drying group (25.8 NTU), while the lowest turbidity was observed in the 45 °C/−70 kPa/45 r/min group (13.1 NTU). Sensory evaluation data revealed aroma intensity scores ranging from 6.2 to 8.4, while bitterness intensity scores fell between 7.1 and 8.8. The highest scores for aftertaste, tea liquor color, overall acceptability, and flavor persistence were all achieved under the 45 °C/−70 kPa/40 r/min condition, reaching 8.6, 8.7, 8.8, and 8.5, respectively. Overall, alterations in drying temperature, pressure, and rotation speed parameters exhibited systematic variations with the tea liquor’s physical properties and sensory quality. Specifically, under the experimental conditions of this study, the use of moderate combinations of vacuum level and rotation speed tended to be associated with lower turbidity of the tea liquor and higher flavor acceptability scores.

Figure 11.

Scoring chart of Scutellaria baicalensis beverage under different processing conditions.

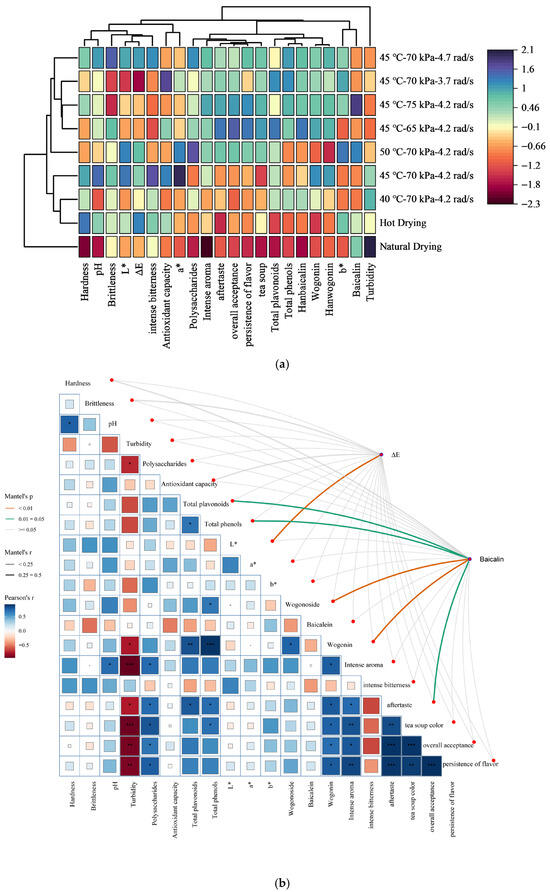

3.11. Hierarchical Clustering Analysis and Correlation Network Analysis Heatmap

Hierarchical clustering and correlation network analyses revealed consistent multivariate structures across both sample and indicator dimensions. The bidirectional clustering heatmap (Figure 12a), based on standardized data, Euclidean distance, and the minimum-distance (single-linkage) method, showed that naturally dried and hot-air-dried samples formed separate branches. Microwave vacuum–treated samples clustered into a single main branch with several adjacent subgroups [21,36]. At the indicator dimension, phenolic/flavonoid pools and representative monomers (total phenols, total flavonoids, baicalin, wogonoside, baicalein, wogonin) clustered together with antioxidant activity [15,49]; texture parameters (hardness, brittleness) were proximate to selected color coordinates (e.g., L*, b*), while pH and turbidity formed relatively independent branches, indicating variation patterns structurally divergent from most quality attributes.

Figure 12.

(a) Hierarchical clustering analysis diagram of Scutellaria baicalensis under different treatment conditions. (b) Corresponding Matrix and Mantel Association Network. Correlation matrix (or Mantel association network) showing… (your description). The asterisks denote statistical significance: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

The network (Figure 12b), based on distance-matrix correlations from Mantel tests, showed connections between components, color, and sensory attributes. Nodes representing active compounds (e.g., baicalin) had significant correlations (Mantel’s r > 0.5, p < 0.05) with color differences and sensory descriptors such as overall acceptability, flavor persistence, and tea liquor color [13,21]. ΔE also formed stable network edges with several physicochemical and sensory variables, whereas pH and turbidity were predominantly peripheral with limited connectivity [51]. Together, these analyses show that, within the key indicator framework used here, microwave vacuum processing forms distinct and consistent clusters compared to conventional drying. This applies to active-component content, appearance/color, and overall sensory evaluation. Consequently, within the association network framework established in this study, baicalin content and color difference (ΔE) may serve as potentially useful indicators for evaluating the overall quality of S. baicalensis dried products; however, their universality and robustness as predictive indicators require systematic verification in future studies.

4. Conclusions and Discussion

This study confirms that TMVD is a highly efficient and high-quality method for processing S. baicalensis slices. Compared to conventional hot-air drying, TMVD drastically reduced the drying time from 240 min to 40–50 min and lowered the specific energy consumption by approximately 51%. Temperature was identified as the most dominant factor affecting the drying rate, but its effect exhibited a threshold, with limited improvement beyond 45 °C. This is likely due to surface hardening at higher temperatures, which impedes internal moisture migration. Vacuum level and rotation speed also significantly influenced the process, with the optimal combination found at −70 to −75 kPa and 4.2 rad/s. Regarding product quality, TMVD demonstrated superior performance. It significantly better preserved key active components, including baicalin, wogonoside, total phenolics, and polysaccharides. This is primarily attributed to the rapid, low-temperature, and oxygen-depleted drying environment, which effectively minimized thermal degradation and oxidation. Furthermore, the tea infusion prepared from TMVD products had lower turbidity, a more desirable color, and significantly higher sensory acceptability scores (up to 8.8) than those from traditional methods. Multivariate analysis revealed, for the first time, positive correlations between key active components (e.g., baicalin) and sensory acceptance/liquor clarity, establishing a quantitative basis for product quality assessment. In conclusion, the optimized parameter set of 50 °C, −75 kPa, and 4.2 rad/s is recommended for industrial application, as it achieves the best balance among drying efficiency, energy consumption, and final product quality (both bioactive and sensory) for producing high-quality S. baicalensis ingredients. It should be noted that this study has certain limitations. The experimental scope was confined to specific ranges of temperature, vacuum pressure, and rotation speed. Future research could explore wider parameter intervals or the influence of factors such as slice thickness and pre-treatments. Additionally, the use of plant material from a single geographical origin may affect the generalizability of the findings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.Z. (Zewen Zhu); Formal analysis, Z.Z. (Zewen Zhu); Funding acquisition, G.M. and X.H.; Investigation, Z.Z. (Zewen Zhu) and P.W.; Methodology, Z.Z. (Zewen Zhu), G.M., X.H. and F.W.; Resources, F.W.; Software, Z.Z. (Zewen Zhu); Supervision, X.Y. and Y.Z.; Validation, Z.Z. (Zewen Zhu), F.W. and Y.L.; Visualization, X.Y. and C.K.; Writing—original draft, X.Y.; Writing—review and editing, G.M. and Z.Z. (Zepeng Zang). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Gansu Provincial Science and Technology Plan (23CXNA0017). The vacuum far-infrared drying characteristics and heat and mass transfer mechanism of Angelica sinensis (Young Mentor Fund) (0522014).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because it involved routine sensory evaluation of food products, which is considered low-risk and exempt under the institutional guidelines of Gansu Agricultural University. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles for sensory science research.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written or verbal consent was witnessed and formally recorded.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank the scientific research team for agricultural mechanization and automation at Gansu Agricultural University for help and encouragement.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Xiang, L.; Gao, Y.; Chen, S.; Sun, J.; Wu, J.; Meng, X. Therapeutic potential of Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi in lung cancer therapy. Phytomedicine 2022, 95, 153727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, J.Y.; Im, E.; Kim, N.D. Therapeutic potential of bioactive components from Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi in inflammatory bowel disease and colorectal cancer: A review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Gao, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Kong, L.J. Exploring bioactive constituents and pharmacological effects of Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi: A review. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2024, 19, 1934578X241266692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kılıç, T.; Paşa, C.; Gören, A.C. Medicinal use and chemical composition of Scutellaria baicalensis species. Rec. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 4, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, T.; Shibuya, N.; Fujii, T.; Tago, M.; Narukawa, Y.; Tamura, H.; Kiuchi, F. Inhibition of prostaglandin E2 production by a combination of flavonoids from Scutellaria baicalensis. Planta Medica 2016, 82, 1295–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, H.J.; Zhu, H.Y.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Lu, Y.; Li, H.; Chen, D.F. In vivo effect of quantified flavonoids-enriched extract of Scutellaria baicalensis root on acute lung injury induced by influenza A virus. Phytomedicine 2019, 57, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, T.T.; Wang, M.; Chen, Y.H.; Chung, Y.T.; Hwang, P.A. Propylene glycol improves stability of the anti-inflammatory compounds in Scutellaria baicalensis extract. Processes 2021, 9, 894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Jiang, S.; Sun, T.; Zhi, W.; Ding, Z.; Qing, Z.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y. Post-harvest processing methods have critical roles on the contents of active metabolites and pharmacological effects of Astragali Radix. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1489777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rai, R.; Rani, P.; Tripathy, P.P. Osmo-air drying of banana slices: Multivariate analysis, process optimization and product quality characterization. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 58, 4379–4391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, L.Q.; Xiong, Y.; Wang, Y.Q.; Cao, L.J.; Zhen, Y.; Yang, M. Preliminary study on standardization of production and processing of Scutellaria baicalensis pieces. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi 2019, 44, 3281–3286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.J.; He, Y.; Zhang, J.H.; Wang, W.K.; Li, X.; Rao, X.Y.; Wang, F.; Luo, X.J. Isothermal adsorption, desorption and thermodynamic properties of Scutellaria baicalensis pieces. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi 2016, 41, 830–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, M.; Sheng, X.; Zhang, J.; Liu, X.; Dai, Q.; Chen, Y.; Kang, A. Homeostatic regulation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor-cytochrome P450 1a axis by Scutellaria baicalensis-Coptis chinensis herb pair and its main constituents. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022, 297, 115545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Liu, T.; Ogaji, O.D.; Li, J.; Du, K.; Chang, Y. Recent advances in Scutellariae radix: A comprehensive review on ethnobotanical uses, processing, phytochemistry, pharmacological effects, quality control and influence factors of biosynthesis. Heliyon 2024, 10, e36146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Sandahl, M.; Sjöberg, P.J.; Charlotta, T. Pressurised hot water extraction in continuous flow mode for thermolabile compounds: Extraction of polyphenols in red onions. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2014, 406, 441–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, C.; Yang, J.; Cao, B.; Xue, Y.; Gao, P.; Liang, H.; Li, G. Growth years and post-harvest processing methods have critical roles on the contents of medicinal active ingredients of Scutellaria baicalensis. Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 158, 112985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Lan, Y.; Luo, L.; Xiao, Y.; Meng, X.; Zeng, Y.; Wu, J. The Scutellaria-Coptis herb couple and its active small-molecule ingredient wogonoside alleviate cytokine storm by regulating the CD39/NLRP3/GSDMD signaling pathway. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 329, 118155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinke, I.; Kulozik, U. Enhancing microwave freeze drying: Exploring maximum drying temperature and power input for improved energy efficiency and uniformity. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2024, 17, 2587–2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, B.B.; Janghu, S. Role of food microwave drying in hybrid drying technology. In Microwave Heating—Electromagnetic Fields Causing Thermal and Non-Thermal Effects; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, C.; Wei, Z.; Huang, W.; Yan, Z.; Luo, Z.; Beta, T.; Xu, X. Effects of four drying methods on the quality, antioxidant activity and anthocyanin components of blueberry pomace. Food Prod. Process. Nutr. 2023, 5, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Xia, L.; Wang, F.; Guo, S.; Zou, J.; Su, X.; Yu, P. Comparison of different drying methods on Chinese yam: Changes in physicochemical properties, bioactive components, antioxidant properties and microstructure. Int. J. Food Eng. 2020, 16, 20200009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, Z.; Huang, X.; He, C.; Zhang, Q.; Jiang, C.; Wan, F. Improving drying characteristics and physicochemical quality of Angelica sinensis by novel tray rotation microwave vacuum drying. Foods 2023, 12, 1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardhani, N.K.S.; Amanda, N.; Sari, A.R. Microwave vacuum drying on fruit: A review. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Food, Agriculture, and Natural Resources (IC-FANRes 2021), Online, 4–5 August 2021; Atlantis Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, K.K.; Shangpliang, H.; Raj, G.V.S.; Chakraborty, S.; Sahu, J.K. Influence of microwave vacuum drying process parameters on phytochemical properties of sohiong (Prunus nepalensis) fruit. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2021, 45, e15290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Bai, X.; Sun, J.; Zhu, W. Implication of ultrasonic power and frequency for the ultrasonic vacuum drying of honey. Dry. Technol. 2020, 39, 668–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, S.; Niu, Y.; Yuwen, C.; Liu, B. Microwave drying of Tricholoma matsutake: Dielectric properties, mechanism, and process optimization. Foods 2025, 14, 3054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Song, Z.; Ding, C. Study on the effect of ultrasonic and cold plasma non-thermal pretreatment combined with hot air on the drying characteristics and quality of yams. Foods 2025, 14, 2831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Wang, J.; Zhang, L.; Liu, S.; Li, C. Effects of osmotic dehydration on mass transfer of tender coconut kernel. Foods 2024, 13, 2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llavata, B.; Collazos-Escobar, G.A.; García-Pérez, J.V.; Carcel, J.A. PEF pre-treatment and ultrasound-assisted drying at different temperatures as a stabilizing method for the up-cycling of kiwifruit: Effect on drying kinetics and final quality. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2024, 92, 103591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, N.K.; Thakur, S.; Budhathoki, S.; Baral, D. pH profile and acidity analysis of some Nepalese tea brands: Effects of tea type and temperature. Bibechana 2024, 21, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wan, F.; Huang, X.; Yang, X.; Zang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Wu, B.; Zhang, K.; Ma, G. Novel ultrasonic pretreatment for improving drying performance and physicochemical properties of licorice slices during radio frequency vacuum drying. Foods 2024, 13, 4071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, X.; Liang, Z. Post-harvest processing methods have critical roles in the contents of active ingredients of Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi. Molecules 2022, 27, 8302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendonça, K.S.; Corrêa, J.L.G.; Junqueira, J.R.J.; Carvalho, E.E.N.; Silveira, P.G.S.; Uemura, J.H.S. Peruvian carrot chips obtained by microwave and microwave-vacuum drying. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 185, 115346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, R.L.; Link, J.V.; Tribuzi, G.; Carciofi, B.A.M.; Laurindo, J.B. Microwave vacuum drying and multi-flash drying of pumpkin slices. J. Food Eng. 2018, 232, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauhiduzzaman, M.; Hafez, I.; Bousfield, D.W.; Tajvidi, M. Modeling microwave heating and drying of lignocellulosic foams through coupled electromagnetic and heat transfer analysis. Processes 2021, 9, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, L.; Fernandes, J.R.; Nunes, F.M.; Tavares, P.B. Effect of drying temperature and storage time on the crispiness of homemade apple snacks. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2024, 104, 916–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, R.; Pratap-Singh, A. Microwave vacuum dehydration technology in food processing. In Innovative Food Processing Technologies: A Comprehensive Review; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebert, T.; Zubér, M.; Engelhardt, S.; Baumbach, T.; Karbstein, H.P.; Gaukd, V. Visualization of crust formation during hot-air-drying via micro-CT. Dry. Technol. 2018, 37, 1881–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taşkın, O.; Polat, A.; İzli, N.; Asik, B.B. Intermittent microwave-vacuum drying effects on pears. Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2019, 69, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisel, N.N.; Vaganova, A.A.; Savitskiy, A.N. Simulation modeling of grain heating by the energy of electromagnetic microwave field. Izvestiâ ÛFU. Tehničeskie Nauki 2020, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Ma, Z.; Wan, F.; Chen, A.; Zhang, W.; Xu, Y.; Zang, Z.; Huang, X. Different Pretreatment Methods to Strengthen the Microwave Vacuum Drying of Honeysuckle: Effects on the Moisture Migration and Physicochemical Quality. Foods 2024, 13, 3712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaei, B.; Chayjan, R.A. Modelling of nectarine drying under near infrared—Vacuum conditions. Acta Sci. Pol. Technol. Aliment. 2015, 14, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayvas, B.; Markovych, B.M.; Dmytruk, A.A.; Havran, M.; Dmytruk, V. The methods of optimization and regulation of the convective drying process of materials in drying installations. Math. Model. Comput. 2024, 11, 546–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligarda-Samanez, C.A.; Choque-Quispe, D.; Moscoso-Moscoso, E.; Palomino-Rincón, H. Nanoencapsulation of phenolic extracts from native potato clones (Solanum tuberosum spp. andigena) by spray drying. Molecules 2023, 28, 4961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, Z.; Ge, D.; Zhou, J.; Xu, Y. Suppression of cracking in drying colloidal suspensions with chain-like particles. J. Chem. Phys. 2024, 160, 164904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koutra, C.; Routsi, E.; Stathopoulos, P.; Kalpoutzakis, E.; Humbert, M.; Maubert, O.; Skaltsounis, A.-L. A novel process for oleacein production from olive leaves using freeze drying methodology. Foods 2025, 14, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garland, N.; Gordon, R.; McElroy, C.R.; Parkin, A.; MacQuarrie, D. Optimising low temperature pyrolysis of mesoporous alginate-derived Starbon® for selective heavy metal adsorption. ChemSusChem 2024, 17, e202400015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, K.; He, L.; Peng, L. Reinforcement of the bio-gas conversion from pyrolysis of wheat straw by hot caustic pre-extraction. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2018, 11, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Bi, J.; Yi, J.; Wu, X.; Li, X.; Zhao, Y. Stability of phenolic compounds and drying characteristics of apple peel as affected by three drying treatments. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2021, 10, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, L.M.; Ceccanti, C.; Negro, C.; Bellis, L.D.; Incrocci, L.; Pardossi, A.; Guidi, L. Effect of drying methods on phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity of Urtica dioica L. leaves. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsved, M.; Holm, S.; Christiansen, S.; Smidit, M.; Rosati, B.; Ling, M.; Boesen, T.; Finster, K.; Bilde, M.; Londahi, J.; et al. Effect of aerosolization and drying on the viability of Pseudomonas syringae cells. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 3086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Xu, J.L.; Sun, D.W. Evaluating drying feature differences between ginger slices and splits during microwave-vacuum drying by hyperspectral imaging technique. Food Chem. 2020, 332, 127407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).