Abstract

Soil degradation, declining fertility, and rising greenhouse gas emissions highlight the urgent need for sustainable soil management strategies. Among them, biochar has gained recognition as a multifunctional material capable of enhancing soil fertility, sequestering carbon, and valorizing biomass residues within circular economy frameworks. This review synthesizes evidence from 186 peer-reviewed studies to evaluate how feedstock diversity, pyrolysis temperature, and elemental composition shape the agronomic and environmental performance of biochar. Crop residues dominated the literature (17.6%), while wood, manures, sewage sludge, and industrial by-products provided more targeted functionalities. Pyrolysis temperature emerged as the primary performance driver: 300–400 °C biochars improved pH, cation exchange capacity (CEC), water retention, and crop yield, whereas 450–550 °C biochars favored stability, nutrient concentration, and long-term carbon sequestration. Elemental composition averaged 60.7 wt.% C, 2.1 wt.% N, and 27.5 wt.% O, underscoring trade-offs between nutrient supply and structural persistence. Greenhouse gas (GHG) outcomes were context-dependent, with consistent Nitrous Oxide (N2O) reductions in loam and clay soils but variable CH4 responses in paddy systems. An emerging trend, present in 10.6% of studies, is the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) to improve predictive accuracy, adsorption modeling, and life-cycle assessment. Collectively, the evidence confirms that biochar cannot be universally optimized but must be tailored to specific objectives, ranging from soil fertility enhancement to climate mitigation.

1. Introduction

1.1. Global Relevance

Soil degradation, declining fertility, and the intensification of climate change represent critical challenges for global food security and environmental sustainability. Conventional practices relying on synthetic fertilizers and intensive land management have often exacerbated GHG emissions and depleted soil organic carbon (SOC) reserves. In this context, biochar has emerged as a multifunctional material with the capacity to enhance soil fertility, sequester carbon, reduce GHG emissions, and simultaneously valorize agricultural and industrial residues within circular economy frameworks. Its multifunctionality positions biochar at the intersection of sustainable agriculture, climate mitigation, and resource recovery.

Beyond the scientific evidence, biochar has also been acknowledged in international climate policy frameworks, including the IPCC guidelines and the European Green Deal, reinforcing its strategic role as a tool for climate neutrality and sustainable land management.

1.2. State of Knowledge—Feedstocks and Pyrolysis

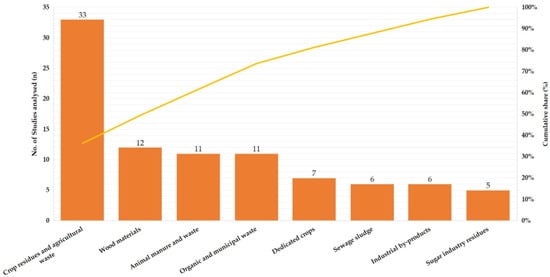

Biochar is an emerging term describing a class of carbonaceous materials produced for sustainable applications, including renewable energy generation, soil remediation, and carbon sequestration. It is scientifically defined as a carbon-rich, charcoal-like substance obtained through partial oxidation of carbon-based organic feedstocks such as wood, plant residues, and other forms of biomass, under conditions of limited or absent oxygen supply [1]. The performance of biochar is fundamentally shaped by feedstock type and pyrolysis conditions, which together dictate its physicochemical properties, agronomic potential, and environmental functionality. A wide spectrum of biomass sources has been investigated, reflecting both regional availability and research priorities. Lignocellulosic feedstocks such as pine, poplar, eucalyptus, willow, hardwood sawdust, softwood shavings, and bamboo produce biochars rich in aromatic carbon, with long-term stability and predictable pore structures suited for persistent soil conditioning [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. Crop residues and agricultural wastes dominate the literature (~17.6%), with rice husk, rice straw, wheat straw, maize stover, peanut shells, cotton stalks, coconut shells, sugarcane bagasse, sunflower husks, and coffee husks frequently tested for their ability to raise soil pH, enhance nutrient retention, improve water-holding capacity, and increase yields [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47]. Dedicated energy crops such as corn, switchgrass, rapeseed, sorghum, and quinoa, though less studied (3.7%), highlight dual opportunities for soil improvement and renewable energy [48,49,50,51,52,53,54]. Animal manures (5.9%), including poultry litter, cattle, pig, and goat manure, produce nutrient-rich biochars that supply slow-release N, P, and K while stimulating microbial cycling [16,17,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64]. Organic and municipal wastes (5.9%), such as food waste, mill residues, forest residues, and municipal solid waste, have been successfully converted into biochars for heavy metal immobilization and soil organic matter enhancement [65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74]. Sewage sludge (3.2%) yields P-enriched biochars that also stabilize organic contaminants [75,76,77,78,79,80], while industrial by-products (3.2%) including steel slag, paper sludge, and bio-oil residues, have been tested for remediation and soil buffering [3,22,47,78,81,82]. Finally, sugar industry residues (2.7%), such as sugar beet waste, sugarcane filter cake, molasses residues, and bagasse, improve SOC stocks and soil water retention [83,84,85,86,87]. Table 1 synthesizes the major biomass categories, while Figure 1 illustrates their relative distribution across the 186 reviewed studies.

Table 1.

Feedstock categories for biochar production across 186 studies (2012–2025).

Figure 1.

Relative distribution of reviewed studies across biomass feedstock categories for biochar production.

The overview provided in Table 1 emphasizes the diversity of biomass feedstocks explored for biochar production, ranging from lignocellulosic residues and dedicated crops to industrial by-products and sewage sludge. To complement this qualitative synthesis, Figure 1 presents the Pareto distribution of feedstock representation across the 186 reviewed studies. The bar chart shows the absolute frequency of studies per category, while the cumulative curve illustrates the Pareto principle: a small number of feedstocks capture most of the research attention, whereas a long tail remains marginal. More than 33% of the studies address crop residues and agricultural wastes, followed at a distance by wood materials, animal manures, and organic municipal wastes (~30% combined). By contrast, sewage sludge, industrial by-products, and sugar industry residues together contribute less than 20% of the total evidence base. This skewed distribution demonstrates the predominance of lignocellulosic resources in biochar research while exposing systematically underexplored feedstocks whose physicochemical variability and environmental trade-offs remain poorly resolved.

1.3. Gaps and Contradictions

Despite intensive research, several uncertainties constrain large-scale deployment. Feedstock heterogeneity complicates standardization, as ash content, pH, CEC, and potential contaminants vary widely. Biochar-SOC interactions remain inconsistent: low-temperature biochars (300–400 °C) often stimulate microbial activity and nutrient cycling (positive priming), whereas high-temperature biochars (450–550 °C) promote SOC stabilization via recalcitrant carbon structures (negative priming). Similarly, GHG mitigation outcomes are context-dependent, consistent reductions in N2O have been observed in loam and clay soils, but CH4 responses in paddy systems range from mitigation to stimulation, while CO2 outcomes vary from reductions to neutral or elevated fluxes. Moreover, relatively fewer than 10 studies have integrated long-term field trials or advanced computational methods to resolve these contradictions.

Contribution of this review. This article addresses these gaps by synthesizing evidence from 186 peer-reviewed studies. It provides an integrative analysis of how feedstock diversity and pyrolysis regimes influence biochar’s physicochemical composition, agronomic performance, and environmental impacts. A particular focus is placed on SOC priming effects, GHG mitigation, and the functional trade-offs between fertility enhancement and carbon stabilization. Additionally, this review highlights the emerging application of AI and machine learning (ML) in biochar-soil systems, illustrating their potential to improve predictive accuracy, reduce uncertainty, and accelerate scalable deployment.

This review addresses three central questions: (i) How can biochar be optimized for agricultural soils through feedstock selection and pyrolysis conditions? (ii) What are the trade-offs between fertility enhancement, SOC stabilization, and greenhouse gas mitigation? (iii) How can AI support predictive modeling, decision support, and the scaling-up of biochar applications? By structuring the synthesis around these questions, this review provides a critical assessment of one hundred eighty-eight peer-reviewed studies, identifies major knowledge gaps, and outlines future directions for positioning biochar as a cornerstone of sustainable agriculture, climate mitigation, and circular economy strategies.

1.4. Literature Search and Selection Criteria

A systematic literature search was conducted in Web of Science Core Collection, Scopus, and PubMed, covering the period 2012–2025. Search strings combined controlled vocabulary and free-text terms for biochar, soil fertility, carbon sequestration, and greenhouse gas mitigation. The initial search yielded 1325 records from databases and 87 from additional sources (n = 1412). After removal of 421 duplicates, 991 unique records remained for title and abstract screening. Of these, 671 were excluded as irrelevant, leaving 320 articles for full-text assessment. Following PRISMA eligibility criteria, 132 full texts were excluded due to insufficient biochar characterization, absence of agronomic or environmental outcomes, or duplication of previously published datasets. Ultimately, 186 peer-reviewed studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were synthesized in this review. The selection protocol adhered to PRISMA guidelines to ensure transparency and reproducibility in the literature identification, screening, exclusion, and inclusion.

2. Priming of SOC Sequestration

Table 2 synthesizes the principal factors influencing positive and negative priming effects of SOC following biochar addition.

Table 2.

Key factors driving positive and negative priming effects on SOC sequestration following biochar application.

Positive priming has frequently been reported when biochar stimulated microbial activity and improved soil fertility, thereby accelerating the decomposition of native organic matter. Multiple studies across diverse soil types documented increases in microbial populations after biochar incorporation, resulting in faster SOC turnover [2,3,7,26,32,38,56,57,64,88]. In sandy soils, biochar was shown to improve aeration and nutrient cycling, which in turn facilitated microbial processing of SOC [17,18,21,30,39,45]. Application rate also proved critical: moderate additions, typically ≤15% w/w or ≤30 mg· ha−1, promoted microbial utilization of existing carbon pools without saturating the soil system [14,15,16,22,27,33,37,41,47]. Biochars produced at low pyrolysis temperatures (300–400 °C), particularly from manures and crop residues, contained labile carbon fractions readily metabolized by microbes, thereby enhancing mineralization processes [3,22,44,78,81,82]. Short-term incubation trials (<6 months) consistently highlighted the role of these labile fractions in initiating positive priming responses [20,28,36,40,44,59,85]. In several cases, cyclic dynamics were observed, with initial positive priming followed by neutral or negative effects during medium-term incubations, and a return to positive effects in longer-term experiments, underscoring the temporal variability of priming mechanisms [11,12,34,51,54]. Conversely, negative priming is commonly associated with stabilization of SOC rather than its decomposition. Physical protection afforded by biochar pores and surfaces can limit microbial access to native carbon [35,65,75,76,78,80]. Sorption of dissolved organic matter onto biochar surfaces further reduces labile carbon availability, constraining microbial metabolism [19,66,68,70,71,72]. In certain cases, inhibitory effects were attributed to toxic constituents of specific biochars, including polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), heavy metals, or residual ammonia [55,56,57,61,62]. Biochars produced at high pyrolysis temperatures (>500 °C) consistently demonstrate greater stability in soils. This effect is mainly attributed to their higher content of resistant, aromatic carbon structures, which slow down the decomposition of both the biochar itself and the native SOC [5,26,42,46,77]. Long-term incubation studies (lasting more than one year) often report negative priming effects, meaning that biochar, as it ages and interacts with soil mineral components, tends to suppress microbial activity and carbon turnover [36,67,69,70,73,74]. Some studies have observed alternating temporal patterns—negative followed by positive and again negative priming—reflecting shifts in microbial community composition and plant–soil feedback processes over time [13,52,53,87,89].

Overall, priming effects are strongly context-dependent. Low-temperature biochars and moderate application rates tend to favor short-term microbial stimulation and carbon mineralization, while high-temperature biochars and long-term incubations more reliably enhance SOC stabilization. These contrasting outcomes highlight a critical trade-off for agricultural management: strategies that maximize immediate fertility gains may compromise long-term carbon storage, whereas approaches that prioritize sequestration may deliver fewer short-term productivity benefits.

3. Agricultural, Environmental and Industrial Applications of Biochar

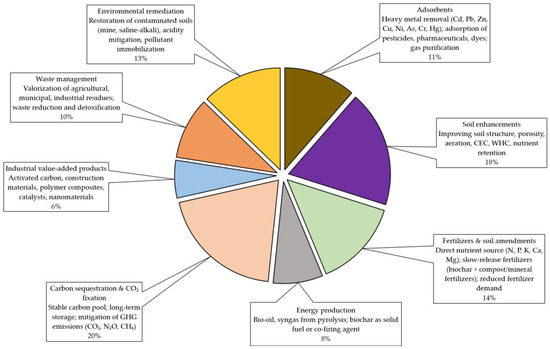

The broad spectrum of biochar applications reported across the 186 reviewed studies underscores its multifunctional role as both a soil amendment and an industrially relevant material. Figure 2 depicts the distribution of these studies, while Table 3 categorizes the principal domains of utilization.

Figure 2.

Distribution of biochar application domains in the reviewed literature (% out of total).

Table 3.

Reported environmental and industrial applications of biochar.

Adsorbent functions were highlighted in ~22% of the literature, reflecting sustained interest in biochar’s capacity to immobilize contaminants. Effective removal of heavy metals, including cadmium, lead, zinc, copper, arsenic, chromium, and mercury, was demonstrated in both soils and wastewater systems [2,65,66,67,75]. Beyond metals, biochar was applied for the sorption of pesticides, pharmaceuticals, and synthetic dyes, confirming its value in pollution mitigation [35,68,69,70,71,72,73,80]. These properties derive from its high porosity and abundance of surface functional groups, positioning biochar as a low-cost, effective adsorbent.

Soil enhancement applications accounted for ~36% of studies, making this the second most prominent category. Biochar was consistently reported to improve soil structure, porosity, aeration, CEC, water-holding capacity (WHC), and nutrient retention. For instance, rice husk and wheat straw biochars enhanced nutrient availability in sandy soils [14,15,16,17,18,19], while maize stover and peanut shell biochars improved aggregation and water retention [20,21,22,26].

Fertilizer and soil amendment uses were documented in ~27% of studies. Biochar was evaluated both as a direct source of nutrients, providing N, P, K, Ca, and Mg, and as a slow-release fertilizer when integrated with compost or mineral fertilizers [3,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,81]. Manure-derived biochars, particularly from poultry litter and cattle residues, exhibited higher nutrient concentrations than crop-derived biochars, thereby reducing reliance on synthetic fertilizers [62,63,64,78,82].

Energy-related applications appeared in ~15% of the dataset. Co-products of pyrolysis such as bio-oil and syngas were assessed as renewable energy sources, while biochar itself was considered a solid fuel and in co-firing systems [3,22,44,47,75,76,77,78,79,81,82].

Carbon sequestration and greenhouse gas mitigation were the most frequently reported applications, comprising ~39% of studies. Biochar was consistently characterized as a stable carbon pool with high potential for long-term CO2 fixation [2,3,15,17,65]. Field trials confirmed reductions in CO2, N2O, and CH4 emissions, consolidating its role in climate change mitigation [6,8,12,26,32,35,38,42,64]. Industrial applications were identified in ~12% of reviewed papers. Activated carbon derived from biochar, construction composites (cement blends, bricks), polymer-based composites, catalysts, and nanomaterials have all been explored [3,4,5,6,7]. Notably, biochar-based composites functioned as lightweight building materials with enhanced insulation, while activation techniques significantly increased adsorption efficiency in water treatment [8,9,10,11,12,13,86].

Waste management strategies represented ~19% of studies, emphasizing biochar’s role in valorizing agricultural residues, municipal solid waste, and industrial by-products [65,66,67,68,70,84]. Pyrolysis of food waste and sewage sludge was particularly relevant, reducing waste volume and toxicity while producing carbon-rich soil conditioners [71,72,73,74,87].

Environmental remediation accounted for ~25% of the dataset. Biochar was successfully applied to rehabilitate mine-degraded soils, reclaim saline-alkali lands, mitigate acidity, and immobilize pollutants [19,20,21,27]. Studies confirmed improvements in soil quality indicators under mining-affected conditions [34,37,51,85] and enhanced crop performance under stress environments [40,44,54,87].

In summary, while soil fertility enhancement and carbon sequestration dominate research, biochar’s broader potential spans remediation, waste valorization, and industrial innovation. These co-benefits strengthen its profile as a strategic material at the interface of agriculture, climate mitigation, and circular economy transitions.

4. Pyrolysis and Composition of Biochar

The relationship between pyrolysis temperature and functional outcomes represents one of the most decisive dimensions in biochar research, since thermal regimes directly control chemical composition, porosity, aromaticity, and long-term stability. To capture these dynamics, Table 4 synthesizes functional suitability across temperature ranges using an ordinal scale (0–5), derived from the relative frequency and consistency of positive outcomes across the 186 reviewed studies. Scores of 5 denote functions where more than 70% of studies consistently reported improvements, values of 2–4 reflect mixed or context-dependent responses, and 0 indicates negligible or absent evidence. Low-temperature biochars (300–350 °C) are most effective in enhancing soil fertility endpoints, including pH buffering, CEC, water retention, and crop yield, largely due to the persistence of labile carbon fractions and nutrient release. In contrast, high-temperature materials (≥450 °C) maximize structural stability, nutrient concentration, and N2O mitigation as a consequence of progressive aromatization, mineral enrichment, and increased recalcitrance. The intermediate regime (350–400 °C) emerges as a transitional zone where agronomic benefits remain high, but the persistence of carbon storage is moderate.

Table 4.

Functional suitability of biochars across pyrolysis temperature ranges.

The color scale represents the functional suitability score (0–5) derived from the frequency of positive outcomes reported across 186 studies. Green shades indicate high suitability (scores 4–5), yellow to orange represent moderate suitability (scores 2–3), and red denotes low suitability (scores 0–1). Lower pyrolysis temperatures (300–350 °C) favor fertility-related functions, while higher temperatures (≥450 °C) enhance stability, carbon sequestration, and N2O mitigation.

While Table 4 provides a semi-quantitative overview of functional suitability, Table 5 complements this analysis by quantifying the strength and direction of correlations among outcomes, thereby validating the trade-off patterns.

Table 5.

Pearson correlation heatmap of biochar functional outcomes across pyrolysis temperature regimes.

The color scale represents Pearson correlation coefficients (r). Red shades indicate strong negative correlations (r < −0.6), yellow represents moderate positive correlations (r ≈ +0.6 to +0.8), and green denotes strong positive correlations (r > +0.9).

Fertility and yield displayed strong negative correlations with pyrolysis temperature (r = −0.99 and −0.83, respectively), while nutrient concentration, structural stability, and N2O mitigation correlated positively (r = 0.94–0.97). Moreover, stability, nutrient enrichment, and N2O mitigation were almost collinear (r > 0.95), whereas fertility-related parameters were negatively associated with them (r ≈ −0.9). These results confirm the existence of a fundamental trade-off: thermal regimes that maximize agronomic performance in the short term tend to undermine long-term carbon stabilization and greenhouse gas mitigation, while high-temperature designs optimized for climate benefits offer fewer immediate gains for soil productivity.

Table 6 presents the pyrolysis temperatures associated with different soil benefits across the 186 reviewed studies, highlighting that agronomic improvements cluster around specific thermal regimes.

Table 6.

Reported average pyrolysis temperatures corresponding to specific soil benefits.

4.1. Soil Properties

Improvements in soil pH were reported in 5 studies, with a median pyrolysis temperature of 400 °C. Biochars derived from sewage sludge and crop residues under these conditions effectively neutralized acidity and promoted plant growth [61,70,89,90,91]. Increases in CEC were noted in 4 studies at 300 °C, where chars retained oxygenated functional groups that enhanced ion exchange [73,90,92,93]. Low-temperature wood and manure biochars were particularly beneficial for sandy, low-fertility soils. Water holding capacity (WHC) improved in 2 studies at 350 °C, reflecting an optimal balance of porosity and structural integrity, especially for chars from manure and agricultural residues [93,94].

4.2. Nutrient Availability and Yield

Enhanced nutrient supply (N, P, K) was reported in seven studies at ~500 °C, where reduced labile C coincided with higher mineral concentrations [26,60,89,93,94,95,96]. Maize stover and sewage sludge chars pyrolyzed above 450 °C provided plant-available nutrients, reducing reliance on chemical fertilizers. Yield and biomass gains were the largest category, with 12 studies showing positive effects around 350 °C for rice, wheat, and maize [64,89,97,98,100,105,109,110,111,112,113,114,115]. Residue-derived chars such as rice husk and wheat straw combined structural improvements with nutrient contributions to drive yield increases [34,99,101,102,103,104,116,117,118,119,120].

4.3. Carbon Dynamics

Increases in SOC and total organic carbon (TOC) were reported in 6 studies with a median temperature of 450 °C. Biochars at this range offered both stable aromatic carbon and moderate labile fractions, supporting sequestration while stimulating microbial activity [93,107,108]. Softwood and manure-based chars at ~450 °C contributed simultaneously to short-term C inputs and long-term stabilization [60,89,106,121,122,123,124,125].

Synthesis. Overall, lower pyrolysis temperatures (300–350 °C) are linked to improvements in CEC, WHC, and crop productivity, while higher temperatures (450–500 °C) are associated with nutrient enrichment and SOC stabilization. This confirms functional trade-offs: low-temperature chars maximize fertility benefits, whereas high-temperature materials are optimized for climate mitigation.

Elemental composition. Feedstock and pyrolysis conditions produced highly variable elemental profiles, Table 7. Crop residue biochars typically showed high carbon content at elevated temperatures. Rice husk biochar at 350 °C contained 54.20% C and 32.50% O, consistent with retention of labile fractions [98], whereas rice straw biochar at 500 °C had 61.70% C and 27.80% O, reflecting aromatic condensation [19,126,127,128,129,130,131]. Wheat straw at 550 °C (66.40% C) and corn stover at 600 °C (69.80% C) confirmed the trend of increasing carbonization [21,26,132,133]. Corn cob biochar at 600 °C reached 79.10% C and 4.25% N, with exceptionally high K (10.10%), making it attractive for agronomy [27,134,135,136,137]. Peanut hull chars at 600 °C showed similar enrichment (65.50% C, 10% K, 2% N) [31], while sugarcane bagasse biochar yielded 76.50% C and 3.03% N [33,138,139,140,141,142,143,144].

Table 7.

Variation in elemental composition of biochars from diverse biomass feedstocks.

Waste-derived materials presented contrasting patterns. Sewage sludge biochar at 500 °C contained only 45.70% C but higher N (3.45%) and P (0.64%) [82,145,146,147,148,149,150]. Poultry litter chars at 400 °C had 42.30% C with enriched nutrients (4.12% N, 2.15% K, 1.87% P) [62,151,152,153,154], and cattle manure biochar at 450 °C showed 39.60% C, 37.90% O, and appreciable P and K contents [64]. Woody feedstocks provided stable, carbon-rich but nutrient-poor chars. Bamboo biochar at 600 °C (72.40% C, 0.94% N) was suitable for long-term storage [42,155,156,157,158,159], while walnut shell biochar at 900 °C (55.30% C, 0.47% N) had extremely low heteroatom content, producing highly recalcitrant materials for sequestration [12,160,161,162,163,164].

Elemental averages. Across the dataset, mean C content was 60.71% (SD 13.30), confirming biochar’s carbon-dominated nature but also its variability. Nitrogen averaged 2.08%, with higher values in manures, sewage sludge, and protein-rich residues. Oxygen averaged 27.49%, decreasing with higher pyrolysis severity. Hydrogen was modest (2.38%), reflecting aromatic condensation. Potassium was the most prominent nutrient (mean 3.02%), with high levels in crop residues such as corn cob and peanut hull. Sulfur (0.13%) and phosphorus (0.81%) were present in smaller amounts, enriched primarily in manures and sludge-derived biochars.

Conclusion. High-temperature pyrolysis of woody and lignocellulosic feedstocks produces stable carbon-rich biochars suitable for sequestration, while manures, sewage sludge, and organic wastes generate nutrient-enriched chars that support soil fertility but with lower long-term stability.

5. Biochar Soil Amendment vs. Other Soil Amendments with Regard to Reduced GHG Emissions

GHG emissions from agricultural soils remain a critical challenge for climate mitigation, and biochar has been extensively investigated as a soil amendment with potential to reduce CO2, N2O, and CH4 emissions while sustaining or even improving crop yields. Table 8 provides a comparative synthesis of studies evaluating biochar’s mitigation performance under diverse soil types, crops, and geographical conditions. The findings demonstrate that both the magnitude and direction of biochar’s effects are highly context-dependent, influenced by soil properties, co-amendments, and experimental duration.

Table 8.

Studies evaluating biochar’s mitigation performance under diverse soil types, crops, and geographical conditions.

Field trials in South Korea on clay loam soils (pH 5.8–5.9) reported that biochar applied at 2 mg·ha−1 together with fly ash and slag improved rice yields by 7–21%, while reducing N2O emissions by up to 5.7% and CH4 by 3.7%. However, some treatments produced >30% increases in CH4, reflecting the complexity of biochar–methane interactions in paddy systems [2,165,166,167,168]. In Japan, sandy loam soils amended with biochar combined with azolla and cyanobacteria produced yield gains of 10–37%, but also increases in N2O (11–26%) and CH4 (7.8–25.6%), pointing to shifts in microbial dynamics toward enhanced gaseous losses [15]. In Bangladesh, biochar combined with slag and gypsum (2–5 mg·ha−1) on clay loam soils improved rice yields by 15–40%, but increased N2O (7.3–25%) and CH4 (9.5–29%) emissions, confirming that co-amendments exert strong, site-specific influences [16].

By contrast, multiple Chinese studies on clay soils demonstrated consistent yield improvements (24–64%) from wheat straw and manure-derived biochars, alongside substantial reductions in N2O emissions, with decreases ranging from 3.6% to over 67% [17]. In southeastern China, steel slag-biochar mixtures applied at 8 mg·ha−1 in silt loam soils produced modest yield gains (0.8–9.3%) but variable GHG responses: CO2 increased by 4–21%, N2O by 15–20%, while CH4 ranged from a reduction of 7.3% to increases of 43% [3].

Evidence from sandy soils in China was mixed: some short-term experiments showed increases of ~7–9% in N2O and CH4 [28,40,109], whereas others reported neutral or minor effects on crop yields [39,47,77,112]. In the United States, corn systems amended with biochar showed an 8% yield increase accompanied by modest increases in CO2 and N2O (6% each) [71]. In Iran, rice experiments produced yield-neutral results but a ~5% increase in CO2 emissions, suggesting limited mitigation under those conditions [110,111]. High biochar application rates (15–45 mg·ha−1) in Chinese loam soils increased soybean yields and SOC by 17.8–58.7%, though emission outcomes were not consistently reported [113]. In red soils under sugarcane cultivation, bagasse biochar trials revealed substantial short-term CO2 reductions (15.8–57.3%) over 100-day incubations, indicating high mitigation potential in specific contexts [86].

In summary, biochar consistently enhances yields across systems, with increases ranging from 7% to over 60%. GHG reductions are most robust for N2O in clay and loam soils when biochar is co-applied with organic inputs, whereas CH4 dynamics in flooded paddy systems remain variable, alternating between mitigation and stimulation.

6. Applications of AI in Biochar-Soil Research

The integration of AI and ML into biochar-soil research is a recent but rapidly expanding trend, reflecting the growing demand for predictive tools and data-driven approaches in soil science. Applications focus on modeling biochar’s impact on soil properties, forecasting agronomic outcomes, and optimizing environmental performance. Table 9 summarizes the principal AI and ML techniques reported, alongside improvements in predictive accuracy and functionality.

Table 9.

ML and AI frameworks in biochar-soil research: reported outcomes.

Regression and classification models were the most frequently applied approaches, identified in 6 studies. These methods predicted soil property changes, such as pH, CEC, WHC, and yield response under varying biochar treatments, with 15–20% higher R2 values compared to conventional linear models. Models trained on datasets that incorporated feedstock type, pyrolysis temperature, and soil properties generated reliable yield predictions [7,39,45,54,79,114,169,170,171,172].

ANNs applied in 3 studies captured nonlinear relationships in nutrient and contaminant dynamics. ANNs successfully modeled adsorption of N, P, and heavy metals in biochar-amended soils, reducing root mean square error (RMSE) by 25–30% relative to equilibrium-based models [73,78,82,173,174,175].

Ensemble learning methods, including Random Forest (RF) and Gradient Boosted Trees (GBT), were reported in 3 studies. These tools identified key drivers of SOC stabilization and nutrient retention, with feature importance values above 85%. Their utility lies in both predictive accuracy and interpretability, isolating feedstock type and pyrolysis temperature as dominant variables [42,46,85,176,177,178,179].

Deep learning techniques such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and long short-term memory (LSTM) networks were applied in 2 studies using soil imaging and sensor data. CNN-based image analysis achieved >90% classification accuracy in quantifying porosity, microstructure, and aggregation under biochar treatments, demonstrating the potential for high-throughput monitoring [44,47,180,181,182].

SVMs were employed in 3 studies for classification, particularly in distinguishing positive, neutral, or negative soil responses to biochar in incubation trials. Reported accuracies exceeded 80%, confirming their utility for moderate datasets in SOC priming contexts [26,36,40,183,184,185,186].

Hybrid AI-LCA frameworks were described in 3 studies, combining ML with life cycle assessment (LCA) to evaluate soil carbon sequestration and greenhouse gas mitigation. These integrations reduced LCA uncertainty by 15–20%, increasing the robustness of long-term projections and supporting policy-relevant climate assessments [86,113,115,186].

Although AI applications appeared in only ~10.6% of the 186 reviewed studies, their diversity, from regression and ensemble methods to deep learning and hybrid modeling, demonstrates significant potential. AI can refine predictions, improve mechanistic understanding, and bridge scales from laboratory experiments to field-level and global assessments.

Although AI and ML have greatly advanced biochar–soil research, several limitations remain. Current datasets are often small, short-term, and geographically narrow, which limits model transferability across soil types and climates [36,42,46,67,69,70,73,74]. Deep learning models can achieve high predictive accuracy but frequently act as “black boxes,” providing limited insight into the underlying soil–biochar mechanisms [89,114,116]. The lack of long-term validation data also restricts reliability, as few studies incorporate temporal dynamics such as biochar aging and microbial adaptation [26,73,74,77]. Moreover, the absence of standardized databases for biochar and soil properties reduces model comparability.

Future research should focus on developing hybrid models that integrate AI with process-based and life-cycle assessment frameworks while expanding global datasets to improve model validation and transferability [116].

7. Conclusions

This review of 186 peer-reviewed studies confirms that biochar is not a one-size-fits-all solution but a multifunctional material whose performance depends fundamentally on the interplay between feedstock type and pyrolysis conditions. Its value lies in the capacity to reconcile soil fertility enhancement, carbon stabilization, and resource valorization within sustainable agriculture and climate mitigation frameworks.

7.1. Key Insights

First, feedstock diversity dictates both opportunities and trade-offs: crop residues dominate due to availability, woody materials provide carbon stability, manures and sludges deliver nutrient enrichment, while industrial and municipal wastes support circular economy pathways. Second, pyrolysis temperature emerged as the critical driver of functional outcomes: low-to-moderate regimes (300–400 °C) favor short-term fertility benefits (pH, CEC, WHC, yield), whereas higher temperatures (450–550 °C) promote long-term SOC stabilization and nutrient concentration. Third, SOC dynamics revealed a duality of positive and negative priming effects, underscoring the importance of application rate, soil type, and temporal scale. Fourth, GHG mitigation outcomes are strongly context-dependent: consistent reductions in N2O were observed in loam and clay soils, while CH4 responses in paddy systems and CO2 fluxes remain variable across studies. Finally, the emerging integration of AI, though still limited, demonstrates the potential to refine predictions, reduce uncertainty, and accelerate scalable deployment of biochar systems.

Although this review provides a broad synthesis of biochar–soil research, several limitations should be noted. The heterogeneity of experimental methods across primary studies complicates direct comparisons, as results depend on biochar type, pyrolysis conditions, soil characteristics, and local climate [5,26,42,46,77]. A geographical bias is evident, with most field data originating from Asia and Europe, while tropical and arid regions remain underrepresented [36,67,69,70,73]. Furthermore, the limited number of long-term and AI-integrated studies restricts understanding of cumulative effects [74,114,116]. These constraints highlight the need for harmonized methodologies and extended field validation across diverse agroecological zones.

7.2. Broader Implications and Future Directions

The accumulated evidence highlights biochar’s strategic role at the interface of soil health, climate policy, and circular economy innovation. Yet, its deployment must be tailored rather than generalized, aligning feedstock selection and pyrolysis design with targeted agronomic or environmental objectives. Future research should prioritize long-term field trials, mechanistic understanding of SOC-microbe interactions, and the integration of AI and life-cycle assessment tools to bridge experimental insights with real-world applications. By doing so, biochar can move beyond promise and evolve into a cornerstone technology for sustainable agriculture, resilient ecosystems, and global carbon management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.M. and A.M.Z.; methodology, A.M.Z. and F.M.; software, F.M.; validation, M.C. and S.O.; formal analysis, O.M.T. and F.B.; investigation, F.M. and A.M.Z.; resources, M.C.; data curation, A.M.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, F.M., O.M.T. and A.M.Z.; writing—review and editing, M.C. and S.O.; visualization, A.R.; supervision, S.O.; project administration, M.C.; funding acquisition, M.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work has been funded by the Romanian Ministry of Research Innovation and Digitalization, under the Core Program within the National Research Development and Innovation Plan 2022–2027, carried out with the support of MCID, grant 20N/2023, project no. PN 23 15 04 02: “Laboratory experiments valorization in the development of technologies for the production of biofuels from agro-industrial waste”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the project Establishment and operationalization of a Competence Center for Soil Health and Food Safety—CeSoH, Contract no.: 760005/2022, specific project no.2, with the title: Restoring soil health on unproductive land through biomass crops for sustainable energy-Soil- Bio mass- Sustainable, Code 2, financed through PNRR-III-C9-2022–I5 (PNRR-National Recovery and Resilience Plan, C9 Support for the private sector, research, development and innovation, I5, Establishment and operationalization of Competence Centers).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| CEC | Cation Exchange Capacity |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| CO2 | Carbon Dioxide |

| CH4 | Methane |

| GBT | Gradient Boosted Trees |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas |

| LCA | Life Cycle Assessment |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| N2O | Nitrous Oxide |

| PAHs | Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons |

| RF | Random Forest |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| SOC | Soil Organic Carbon |

| WHC | Water Holding Capacity |

References

- Bhattacharya, T.; Khan, A.; Ghosh, T.; Tae Kim, J.; Rhim, J.-W. Advances and prospects for biochar utilization in food processing and packaging applications. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2024, 39, e00831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narzari, R.; Bordoloi, N.; Borkotoki, B.; Gogoi, N.; Bora, A.; Kataki, R. Chapter 2—Biochar: An Overview on Its Production, Properties and Potential Benefits; Research India Publications: Delhi, India, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Naveed, M.; Ramzan, N.; Mustafa, A.; Samad, A.; Niamat, B.; Yaseen, M.; Ahmad, Z.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Sun, N.; Shi, W.; et al. Alleviation of Salinity Induced Oxidative Stress in Chenopodium quinoa by Fe Biofortification and Biochar–Endophyte Interaction. Agronomy 2020, 10, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornes, F.; Liu-Xu, L.; Lidón, A.; Sánchez-García, M.; Cayuela, M.L.; Sánchez-Monedero, M.A.; Belda, R.M. Biochar Improves the Properties of Poultry Manure Compost as Growing Media for Rosemary Production. Agronomy 2020, 10, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alagha, O.; Manzar, M.S.; Zubair, M.; Anil, I.; Mu’azu, N.D.; Qureshi, A. Comparative Adsorptive Removal of Phosphate and Nitrate from Wastewater Using Biochar-MgAl LDH Nanocomposites: Coexisting Anions Effect and Mechanistic Studies. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branca, C.; Di Blasi, C. Packed-Bed Pyrolysis of Alkali Lignin for Value-Added Products. Recycling 2025, 10, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosa, A.; Taha, A.; Elsaeid, M. Agro-Environmental Applications of Humic Substances: A Critical Review. Egypt. J. Soil Sci. 2020, 60, 211–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qattan, S.Y.A. Harnessing Bacterial Consortia for Effective Bioremediation: Targeted Removal of Heavy Metals, Hydrocarbons, and Persistent Pollutants. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2025, 37, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isong, I.A.; John, K.; Okon, P.B.; Ogban, P.I.; Afu, S.M. Soil Quality Estimation Using Environmental Covariates and Predictive Models: An Example from Tropical Soils of Nigeria. Ecol. Process. 2022, 11, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brugnari, T.; Braga, D.M.; dos Santos, C.S.A.; Henrique, B.; Torres, C.; Modkovski, T.A.; Haminiuk, C.W.I.; Maciel, G.M. Laccases as Green and Versatile Biocatalysts: From Lab to Enzyme Market—An Overview. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2021, 8, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moteallemi, A.; Taherkhani, S.; Ahmadfazeli, A.; Dehghani, M.H. A Systematic Review of Plastic Wastes as New Adsorbents for Dye Removal in Aqueous Environments. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2025, 37, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Monsalve, S.; Gutterres, M.; Valente, P.; Palacido, J.; Lopez, S.; Kelly, D.; Kelly, S.L. Degradation of a Leather-Dye by the Combination of Depolymerised Wood-Chip Biochar Adsorption and Solid-State Fermentation with Trametes villosa SCS-10. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2020, 7, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazman, M.; Fawzy, S.; Hamdy, A.; Khaled, A.; Mahmoud, A.; Khalid, E.; Ibrahim, H.M.; Gamal, M.; Elyazeed, N.A.; Saber, N.; et al. Enhancing Rice Resilience to Drought by Applying Biochar–Compost Mixture in Low-Fertile Sandy Soil. Beni-Suef Univ. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2023, 12, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govil, S.; Long, N.V.D.; Escribà-Gelonch, M.; Hessel, V. Controlled-Release Fertiliser: Recent Developments and Perspectives. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 219, 119160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Gu, Y.; Zhao, J.; An, X.; Wu, Q.; Yang, D. Utilization of Biochar as a Carrier for the Integrated Controlled Release of Fertilizers and Pesticides: Synergistically Reducing Application Rates and Enhancing Efficiency. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 232, 121235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Luo, D.; Zhang, X.; Huang, R.; Cao, Y.; Liu, G.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H. Biochar-Based Slow-Release of Fertilizers for Sustainable Agriculture: A Mini Review. Environ. Sci. Ecotechnol. 2022, 10, 100167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ighalo, O.; Ohoro, C.; Ojukwu, V.; Oniye, M.; Shaikh, W.A.; Biswas, J.; Seth, C.; Mohan, G.B.M.; Chandran, S.; Rangabhashiyam, S. Biochar for Ameliorating Soil Fertility and Microbial Diversity: From Production to Action of the Black Gold. iScience 2024, 28, 111524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoriello, T.; Fiorentino, S.; Vecchiarelli, V.; Pagano, M. Evaluation of Spent Grain Biochar Impact on Hop (Humulus lupulus L.) Growth by Multivariate Image Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Domenico, G.; Bianchini, L.; Di Stefano, V.; Venanzi, R.; Lo Monaco, A.; Colantoni, A.; Picchio, R. New Frontiers for Raw Wooden Residues, Biochar Production as a Resource for Environmental Challenges. C 2024, 10, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, R.-J.; Li, H.-Q.; Yang, J.-S.; Wang, X.-P.; Xie, W.-P.; Zhang, X. Biochar Addition Inhibits Nitrification by Shifting Community Structure of Ammonia-Oxidizing Microorganisms in Salt-Affected Irrigation-Silting Soil. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, G.; Shen, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Song, B.; Hu, J.; Fang, H. Molecular-Scale Hydrophilicity Induced by Solute: Molecular-Thick Charged Pancakes of Aqueous Salt Solution on Hydrophobic Carbon-Based Surfaces. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 6793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyväluoma, J.; Hannula, M.; Arstila, K.; Wang, H.; Kulju, S.; Rasa, K. Effects of Pyrolysis Temperature on the Hydrologically Relevant Porosity of Willow Biochar. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1810.07417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darko, S.; Comert, G.; Mware, N.; Kibuye, F. Evaluation of Sustainable Green Materials: Pinecone in Permeable Adsorptive Barriers for Remediation of Groundwater Contaminated by Pb2+ and Methylene Blue. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2101.03137. [Google Scholar]

- Cartier, L.; Lembke, S. Climate Change Adaptation in the British Columbia Wine Industry: Can Carbon Sequestration Technology Lower the BC Wine Industry’s Greenhouse Gas Emissions? Appl. Econ. Finance 2021, 8, 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicomel, N.R.; Otero-Gonzalez, L.; Williamson, A.; Ok, Y.S.; Van Der Voort, P.; Hennebel, T.; Du Laing, G. Selective Copper Recovery from Ammoniacal Waste Streams Using a Systematic Biosorption Process. Chemosphere 2022, 286, 131935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, S.M.; Mosa, A.; Natasha; Jeyasundar, P.G.S.A.; Hassan, N.E.E.; Yang, X.; Antoniadis, V.; Li, R.; Wang, J.; Zhang, T.; et al. Pros and Cons of Biochar to Soil Potentially Toxic Element Mobilization and Phytoavailability: Environmental Implications. Earth Syst. Environ. 2023, 7, 321–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Gupta, R.; Zhang, Q.; You, S. Review of Biochar Production via Crop Residue Pyrolysis: Development and Perspectives. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 369, 128423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Cui, Y.; Jiang, S.; Forsell, N. Toward Carbon Neutrality before 2060: Trajectory and Technical Mitigation Potential of Non-CO2 Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Chinese Agriculture. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 368, 133186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.G.B.d.; Paiva, A.B.; Viana, R.d.S.R.; Jindo, K.; de Figueiredo, C.C. Biochar as a Feedstock for Sustainable Fertilizers: Recent Advances and Perspectives. Agriculture 2025, 15, 894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-I.; Park, H.-J.; Jeong, Y.-J.; Seo, B.-S.; Kwak, J.-H.; Yang, H.I.; Xu, X.; Tang, S.; Cheng, W.; Lim, S.-S.; et al. Biochar-Induced Reduction of N2O Emission from East Asian Soils under Aerobic Conditions: Review and Data Analysis. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 291, 118154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingues, R.R.; Trugilho, P.F.; Silva, C.A.; Melo, I.C.N.A.; Melo, L.C.A.; Magriotis, Z.M.; Sanchez-Mondero, M.A. Properties of Biochar Derived from Wood and High-Nutrient Biomasses with the Aim of Agronomic and Environmental Benefits. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0176884. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Xiao, J.; Xue, J.; Zhang, L. Quantifying the Effects of Biochar Application on Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Agricultural Soils: A Global Meta-Analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahapatra, S.; Ali, M.H.; Samal, K. Assessment of Compost Maturity-Stability Indices and Recent Development of Composting Bin. Energy Nexus 2022, 6, 100062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Song, L.; Jin, Y.; Liu, S.; Shen, Q.; Zou, J. Linking N2O Emission from Biochar-Amended Composting Process to the Abundance of Denitrify (nirK and nosZ) Bacteria Community. AMB Expr. 2016, 6, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, A.; Cowie, A.; Mai, T.L.A.; de la Rosa, R.A.; Brandão, M.; Kristiansen, P.; Joseph, S. Quantifying the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Benefits of Utilising Straw Biochar and Enriched Biochar. Energy Procedia 2016, 97, 254–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvaniti, O.S.; Fountoulakis, M.S.; Gatidou, G.; Kalantzi, O.I.; Vakalis, S.; Stasinakis, A.S. Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in Sewage Sludge: Challenges of Biological and Thermal Treatment Processes and Potential Threats to the Environment from Land Disposal. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2024, 36, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Guo, R.; Lu, W.; Zhu, D. Research Progress on Resource Utilization of Leather Solid Waste. J. Leather Sci. Eng. 2019, 1, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, W.; Zhou, G.; Yang, J.; Munir, S.; Ahmed, A.; Liu, Q.; Zhao, Z.; Ji, G. Bacillus amyloliquefaciens WS-10 as a Potential Plant Growth-Promoter and Biocontrol Agent for Bacterial Wilt Disease of Flue-Cured Tobacco. Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Control 2022, 32, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negi, S.; Chai, J.Y.; Tjhin, A.C.T.; Pan, S.Y. Electro-Anaerobic Digestion as Carbon–Neutral Solutions. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2025, 12, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, T.; Xue, G.; Zhao, J.; Ma, W.; Qian, Y.; Wu, M.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, P.; Su, C.; et al. Key Technologies and Equipment for Contaminated Surface/Groundwater Environment in the Rural River Network Area of China: Integrated Remediation. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2021, 33, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, C.; Zhao, H.; Wang, P. Recent Development in Functional Nanomaterials for Sustainable and Smart Agricultural Chemical Technologies. Nano Converg. 2022, 9, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S.; Das, R. Organic Farming to Mitigate Biotic Stresses under Climate Change Scenario. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2024, 48, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.; Halder, M.; Siddique, M.A.B.; Razir, S.A.A.; Sikder, S.; Joardar, J.C. Banana Peel Biochar as Alternative Source of Potassium for Plant Productivity and Sustainable Agriculture. Int. J. Recycl. Org. Waste Agric. 2019, 8 (Suppl. S1), 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalal, F.; Akhtar, K.; Saeed, S.; Said, F.; Hayat, Z.; Hussain, S.; Imtiaz, M.; Khan, M.A.; Liu, K.; Harrison, M.T.; et al. Biochar as Sustainable Input for Nodulation, Yield and Quality of Mung Bean. J. Umm Al-Qura Univ. Appl. Sci. 2024, 10, 510–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Wang, T.; Yang, F.; Cen, R.; Liao, H.; Qu, Z. Effects of Biochar on Soil Evaporation and Moisture Content and the Associated Mechanisms. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2023, 35, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdeen, S.A.; Hefni, H.H.H.; Awadallah-F, A.; El-Rahman, N.R.A. The Synergistic Effect of Biochar and Poly(2-ethyl-2-oxazoline)/Poly (2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate)/Chitosan Hydrogels on Saline Soil Properties and Carrot Productivity. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2023, 10, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palansooriya, K.N.; Withana, P.A.; Jeong, Y.; Sang, M.K.; Cho, Y.; Hwang, G.; Chang, S.X.; Ok, Y.S. Contrasting Effects of Food Waste and Its Biochar on Soil Properties and Lettuce Growth in a Microplastic-Contaminated Soil. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2024, 67, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Gu, M.; Yu, P.; Zhou, C.; Liu, X. Biochar and Vermicompost Amendments Affect Substrate Properties and Plant Growth of Basil and Tomato. Agronomy 2020, 10, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokołowska, Z.; Szewczuk-Karpisz, K.; Turski, M.; Tomczyk, A.; Cybulak, M.; Skic, K. Effect of Wood Waste and Sunflower Husk Biochar on Tensile Strength and Porosity of Dystric Cambisol Artificial Aggregates. Agronomy 2020, 10, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzaz, A.A.; Matei Ghimbeu, C.; Jellai, S.; El-Bassi, L.; Jeguirim, M. Olive Mill by-Products Thermochemical Conversion via Hydrothermal Carbonization and Slow Pyrolysis: Detailed Comparison between the Generated Hydrochars and Biochars Characteristics. Processes 2022, 10, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuda, K.; Sasaki, H. Comparative Assessment of the Scientific Structure of Biomass-Based Hydrogen from a Cross-Domain Perspective. Energy Inform. 2024, 7, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamauchi, S.; Yamagishi, T.; Kirikoshi, K.; Yatagai, M. Factors Governing Cesium Adsorption of Charcoals in Aqueous Solution. J. Wood Sci. 2017, 63, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robazza, A.; Neumann, A. Energy Recovery from Syngas and Pyrolysis Wastewaters with Anaerobic Mixed Cultures. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2024, 11, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangmankongworakoon, N. An Approach to Produce Biochar from Coffee Residue for Fuel and Soil Amendment Purpose. Int. J. Recycl. Org. Waste Agric. 2019, 8 (Suppl. S1), 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-W.; Chang, M.-S.; Mao, Y.; Hu, S.; Kung, C.-C. Machine Learning in the Evaluation and Prediction Models of Biochar Application: A Review. Sci. Prog. 2023, 106, 368504221148842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatrouni, M.; Asses, N.; Bedia, J.; Belver, C.; Molina, C.B.; Mzoughi, N. Acetaminophen Adsorption on Carbon Materials from Citrus Waste. C 2024, 10, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, L.; Xie, Y.; Ma, Q.; Wu, L. The Short-Term Effects of Rice Straw Biochar, Nitrogen and Phosphorus Fertilizer on Rice Yield and Soil Properties in a Cold Waterlogged Paddy Field. Sustainability 2018, 10, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyväluoma, J.; Kulju, S.; Hannula, M.; Wikberg, H.; Kalli, A.; Rasa, K. Quantitative Characterization of Pore Structure of Several Biochars with 3D Imaging. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 25648–25658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Y.; Zhu, L.; Cheng, H.; Yue, S.; Li, S. Effects of Biochar Application on CO2 Emissions from a Cultivated Soil under Semiarid Climate Conditions in Northwest China. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, P.; Park, S.; Oh, K.; Kim, S.; Kim, S.; Kang, K.S.; Kim, D.-H. Energy Recovery from Ginkgo biloba Urban Pruning Wastes: Pyrolysis Optimization and Fuel Property Enhancement for High-Grade Charcoal Productions. Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefin. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, M.; Konvalina, P.; Walkiewicz, A.; Neugschwandtner, R.W.; Kopecký, M.; Zamanian, K.; Chen, W.-H.; Bucur, D. Feasibility of Biochar Derived from Sewage Sludge to Promote Sustainable Agriculture and Mitigate GHG Emissions—A Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abady, M.M.; Mohammed, D.M.; Soliman, T.N.; Shalaby, R.A.; Sakr, F.A. Sustainable Synthesis of Nanomaterials Using Different Renewable Sources. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2025, 49, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaniyan, O.P.; Ajayi, E.I.O. Phytochemicals and In Vitro Anti-Apoptotic Properties of Ethanol and Hot Water Extracts of Cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) Biogas Slurry Following Anaerobic Degradation. Clin. Phytosci. 2021, 7, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiju, P.S.; Patel, A.K.; Shruthy, N.S.; Shalu, S.; Dong, C.D.; Singhania, R.R. Sustainability Through Lignin Valorization: Recent Innovations and Applications Driving Industrial Transformation. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2025, 12, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, R.A.M.; Yuan, W.; Wang, D.; Wang, D.; Kumar, A. The Effect of Gasification Conditions on the Surface Properties of Biochar Produced in a Top-Lit Updraft Gasifier. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahaya Pudza, M.; Zainal Abidin, Z.; Abdul Rashid, S.; Md Yasin, F.; Noor, A.S.M.; Issa, M.A. Eco-Friendly Sustainable Fluorescent Carbon Dots for the Adsorption of Heavy Metal Ions in Aqueous Environment. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhu, H.; Xi, B.; Tian, Y.; Sun, X.; Zhang, H.; Wu, B. Surface Hydrophobic Modification of Biochar by Silane Coupling Agent KH-570. Processes 2022, 10, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, R.; Masek, O.; Erastova, V. Biochars at the Molecular Level. Part 1—Insights into the Molecular Structures within Biochars. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.09661. [Google Scholar]

- Pettersson, K.; Nordlander, A.; Sasic Kalagasidis, A.; Modin, O.; Maggiolo, D. Dynamics of Contaminant Flow Through Porous Media Containing Random Adsorbers. Transp. Porous Media 2025, 152, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, J.; Ippolito, J.; Watts, D.; Sigua, G.; Ducey, T.; Johnson, M. Biochar Compost Blends Facilitate Switchgrass Growth in Mine Soils by Reducing Cd and Zn Bioavailability. Biochar 2019, 1, 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.; Unlu, S.; Demirel, Y.; Black, P.; Riekhof, W. Integration of Biology, Ecology and Engineering for Sustainable Algal-Based Biofuel and Bioproduct Biorefinery. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2018, 5, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiyo, A.K.; Kibet, J.K.; Kengara, F.O. Biocatalytic Degradation of Selected Tobacco Chemicals from Mainstream Cigarette Smoke Using Croton megalocarpus Seed Husk Biochar. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2022, 46, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedzbała, N.; Lorenc-Grabowska, E.; Rutkowski, P.; Checmanowski, J.; Madeja, A.S.; Welna, M.; Michalak, I. Potential Use of Ulva intestinalis-Derived Biochar Adsorbing Phosphate Ions in the Cultivation of Winter Wheat Triticum aestivum. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2024, 11, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azeez, J.O.; Bankole, G.O.; Aghorunse, A.C.; Odelana, T.B.; Oguntade, O.A. Evaluating the Environmental and Agronomic Implications of Bone Char and Biochar Applications to Loamy Sand Based on Sorption Data. Environ. Syst. Res. 2024, 13, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubel, R.I.; Wei, L. Economic Assessment of Biochar-Based Controlled-Release Nitrogen Fertilizer Production at Different Industrial Scales. In Waste Biomass Valorization; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, R.; Masek, O.; Erastova, V. Biochars at the Molecular Level. Part 2—Development of Realistic Molecular Models of Biochars. arXiv 2023, arXiv:4606268. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Lei, Z.; Song, X.; Zhang, Z.; Ying, Y.; Peng, C. Biochar Amendment Decreases Soil Microbial Biomass and Increases Bacterial Diversity in Moso Bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) Plantations under Simulated Nitrogen Deposition. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 044029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.K.; Kim, J.W.; Lee, S.P.; Yang, J.E.; Kim, S.C. Heavy Metal Remediation in Soil with Chemical Amendments and Its Impact on Activity of Antioxidant Enzymes in Lettuce (Lactuca sativa) and Soil Enzymes. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2020, 63, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Joseph, S.; Graber, E.R.; Taherymoosavi, S.; Mitchell, D.R.G.; Munroe, P.; Tsechansky, L.; Lerdahl, O.; Aker, W.; Saebo, M. Fertilizing Behavior of Extract of Organomineral-Activated Biochar: Low-Dose Foliar Application for Promoting Lettuce Growth. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2021, 8, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Hammerschmiedt, T.; Holatko, J.; Pecina, V.; Huska, D.; Latal, O.; Kintl, A.; Radziemska, M.; Muhammad, S.; Gustian, Z.M.; Kolackova, M.; et al. Assessing the Potential of Biochar Aged by Humic Substances to Enhance Plant Growth and Soil Biological Activity. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2021, 8, 46. [Google Scholar]

- Oyebamiji, Y.O.; Adigun, B.A.; Shamsudin, N.A.A.; Ikmal, A.M.; Salisu, M.A.; Malike, F.A.; Lateef, A.A. Recent Advancements in Mitigating Abiotic Stresses in Crops. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, D.; Cong, M.; Xu, Z.; Xu, X.; Tian, X.; Cong, X.; Lu, S. Carbon Sequestration and Environmental Impacts in Ternary Blended Cements Using Dyeing Sludge and Papermaking Sludge. J. Infrastruct. Preserv. Resil. 2024, 5, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngambia, A.; Mašek, O.; Erastova, V. Development of Biochar Molecular Models with Controlled Porosity. Biomass Bioenergy 2024, 184, 107199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussa, R.R. Reducing Carbon Emissions in Egyptian Roads Through Improving the Streets Quality. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 25, 4765–4786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandran, P.; Suresh, S.; Balasubramain, B.; Gangwar, J.; Raj, A.S.; Aarathy, U.L.; Meyyazhagan, A.; Pappuswamy, M.; Sebastian, J.K. Biological treatment solutions using bioreactors for environmental contaminants from industrial waste water. J. Umm Al-Qura Univ. Appl. Sci. 2025, 11, 185–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Yang, Y.; Liu, X.H.; Li, S.; Li, S.; Li, K.; Daeng, H. Effects of Bagasse Biochar Application on Soil Organic Carbon Fixation in Manganese-Contaminated Sugarcane Fields. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2023, 10, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Zhai, X.; Wang, M.; Shi, Y.; Chen, Y.; Liang, Q.; He, B.; Wen, R. Biochar Amendments Improve Soil Functionalities, Microbial Community and Reduce Pokkah Boeng Disease of Sugarcane. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2024, 11, 28. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Y.; Hu, Z.; Ba, Y.; Qi, W. Application of Biochar-Coated Urea Controlled Loss of Fertilizer Nitrogen and Increased Nitrogen Use Efficiency. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2021, 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.N.; Kim, S.S.; Lee, D.W.; Shim, J.H.; Jeon, S.H.; Kwon, I.; Seo, D.C.; Kim, S.H. Characterization and Application of Biochar Derived from Greenhouse Crop By-Products for Soil Improvement and Crop Productivity in South Korea. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2024, 67, 112, Erratum in Appl. Biol. Chem. 2025, 68, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Sun, T.; Ma, H.; Tang, G.; Chen, M.; Abulaizi, M.; Yu, G.; Jia, H. Effects of Acidic Phosphorus-Rich Biochar from Halophyte Species on P Availability and Fractions in Alkaline Soils. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2022, 9, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mastro, F.; Cacace, C.; Traversa, A.; Pallara, M.; Cocozza, C.; Mottola, F.; Brunetti, G. Influence of Chemical and Mineralogical Soil Properties on the Adsorption of Sulfamethoxazole and Diclofenac in Mediterranean Soils. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2022, 9, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.V.; Sawargaonkar, G.; Rani, C.S.; Pasumarthi, R.; Kale, S.; Prakash, T.R.; Triveni, S.; Sigh, A.; Davala, M.S.; Khopade, R.; et al. Harnessing the Potential of Pigeonpea and Maize Feedstock Biochar for Carbon Sequestration, Energy Generation, and Environmental Sustainability. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2024, 11, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, S.; Mosa, A.; Natasha, N.; Abdelrahman, H.; Niazi, N.; Antoniadis, V.; Shahid, M.; Song, H.; Kwon, E.; Rinklebe, J. Removal of Toxic Elements from Aqueous Environments Using Nano Zero-Valent Iron- and Iron Oxide-Modified Biochar: A Review. Biochar 2022, 4, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Minnikova, T.; Kolesnikov, S.; Minkina, T.; Mandzhieva, S. Assessment of Ecological Condition of Haplic Chernozem Calcic Contaminated with Petroleum Hydrocarbons during Application of Bioremediation Agents of Various Natures. Land 2021, 10, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabhane, J.W.; Bhange, V.P.; Patil, P.D.; Bankar, S.T.; Kumar, S. Recent Trends in Biochar Production Methods and Its Application as a Soil Health Conditioner: A Review. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chutia, S.; Narzari, R.; Bordoloi, N.; Saikia, R.; Gogoi, L.; Sut, D.; Bhuyan, N.; Kataki, R. Pyrolysis of Dried Black Liquor Solids and Characterization of the Bio-Char and Bio-Oil. Mater. Today Proc. 2018, 5, 23193–23202. [Google Scholar]

- Jian, G.; Shaohua, G.; Hailong, W.; Yunying, F.; Luming, S.; Tianyi, H.; Xiaoyi, C.; Di, W.; Xuanwei, Z.; Heqing, C.; et al. Biochar-Extracted Liquor Stimulates Nitrogen Related Gene Expression on Improving Nitrogen Utilization in Rice Seedling. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1131937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, S.; Graber, E.; Chia, C.; Munroe, P.; Donne, S.; Thomas, T.; Hook, J. Shifting Paradigms: Development of High-Efficiency Biochar Fertilizers Based on Nano-Structures and Soluble Components. Carbon Manag. 2013, 4, 323–343. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Sun, Y.C.; Sun, R.C. Fractionational and Structural Characterization of Lignin and Its Modification as Biosorbents for Efficient Removal of Chromium from Wastewater: A Review. J. Leather Sci. Eng. 2019, 1, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finore, I.; Feola, A.; Russo, L.; Cattaneo, A.; Donato, P.D.; Nicolaus, B.; Poli, A.; Romano, I. Thermophilic Bacteria and Their Thermozymes in Composting Processes: A Review. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2023, 10, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Ebrahimi, M.; Souri, M.K.; Mousavi, A.; Sahebani, N. Biochar and Vermicompost Improve Growth and Physiological Traits of Eggplant (Solanum melongena L.) under Deficit Irrigation. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2021, 8, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, A.L.; Jannoura, R.; Beuschel, R.; Steiner, C.; Buerkert, A.; Joergensen, R.G. The Combined Application of Nitrogen and Biochar Reduced Microbial Carbon Limitation in Irrigated Soils of West African Urban Horticulture. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2022, 9, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladele, S.; Adeyemo, A.; Awodun, M.; Ajayi, A.; Fasina, A. Effects of Biochar and Nitrogen Fertilizer on Soil Physicochemical Properties, Nitrogen Use Efficiency and Upland Rice (Oryza sativa) Yield Grown on an Alfisol in Southwestern Nigeria. Int. J. Recycl. Org. Waste Agric. 2019, 8, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshitake, S.; Enichi, K.; Tsukimori, Y.; Ohtsuka, T.; Koizumi, H.; Tomotsune, M. Long-Term Effects of Biochar Application on Soil Heterotrophic Respiration in a Warm–Temperate Oak Forest. Forests 2025, 16, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Shen, F.; Smith, R.L.; Qi, X. Black Liquor-Derived Calcium-Activated Biochar for Recovery of Phosphate from Aqueous Solutions. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 294, 122198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djousse Kanouo, B.M.; Allaire, S.E.; Munson, A.D. Quantifying the Influence of Eucalyptus Bark and Corncob Biochars on the Physico-Chemical Properties of a Tropical Oxisol under Two Soil Tillage Modes. Int. J. Recycl. Org. Waste Agric. 2019, 8 (Suppl. S1), 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodor, D.E.; Amanor, Y.J.; Attor, F.T.; Adjadeh, T.A.; Neina, D.; Miyittah, M. Co-Application of Biochar and Cattle Manure Counteract Positive Priming of Carbon Mineralization in a Sandy Soil. Environ. Syst. Res. 2018, 7, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, Q.; Xin, L.; Qin, Y.; Waqas, M.; Wu, W.-X. Exploring Long-Term Effects of Biochar on Mitigating Methane Emissions from Paddy Soil: A Review. Biochar 2021, 3, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, C.W.; Tae, S.; Mandal, S. Comparative Analysis of CO2 Adsorption Performance of Bamboo and Orange Peel Biochars. Molecules 2025, 30, 1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Sun, S.; Xu, S.; Wu, C. CO2 Capture over Steam and KOH Activated Biochar: Effect of Relative Humidity. Biomass Bioenergy 2022, 166, 106608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibitoye, S.E.; Loha, C.; Mahamood, R.M.; Jen, T.C.; Alam, M.; Sarkar, I.; Das, P.; Akinlabi, E.T. An Overview of Biochar Production Techniques and Application in Iron and Steel Industries. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2024, 11, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Shi, F.; Du, J.; Li, L.; Bai, T.; Xing, X. Soil Factors That Contribute to the Abundance and Structure of the Diazotrophic Community and Soybean Growth, Yield, and Quality under Biochar Amendment. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2023, 10, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jindo, K.; Sánchez-Monedero, M.A.; Mastrolonardo, G.; Audette, Y.; Higashikawa, F.S.; Silva, C.; Akshi, K.; Mondini, C. Role of Biochar in Promoting Circular Economy in the Agriculture Sector. Part 2: A Review of the Biochar Roles in Growing Media, Composting and as Soil Amendment. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2020, 7, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, L.; Sanaullah, M.; Mahmood, F.; Hussain, S.; Siddique, M.H.; Andwar, F.; Shahzad, T. Unlocking the Potential of Co-Applied Biochar and Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR) for Sustainable Agriculture under Stress Conditions. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2022, 9, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apori, S.O.; Byalebeka, J.; Muli, G.K. Residual Effects of Corncob Biochar on Tropical Degraded Soil in Central Uganda. Environ. Syst. Res. 2021, 10, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saner, A.; Carvalho, P.N.; Catalano, J.; Anastasakis, K. Renewable Adsorbents from the Solid Residue of Sewage Sludge Hydrothermal Liquefaction for Wastewater Treatment. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 838, 156418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Lu, J.; Jiang, S.; Fu, C.; Li, Y.; Xiang, H.; Lu, R.; Zhu, J.; Yu, B. Enhancing Slow-Release Performance of Biochar-Based Fertilizers with Kaolinite-Infused Polyvinyl Alcohol/Starch Coating: From Fertilizer Development to Field Application. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 302, 140665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrow, C.J. Biochar: Potential for Countering Land Degradation and for Improving Agriculture. Appl. Geogr. 2012, 34, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uras, Ü.; Carrier, M.; Hardie, A.G.; Knoetze, J.H. Physico-Chemical Characterization of Biochars from Vacuum Pyrolysis of South African Agricultural Wastes for Application as Soil Amendments. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2012, 98, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Meng, Y.; Lu, J.; Cheng, Y.; Tao, Y.; Wang, H. Pulping Black Liquor-Based Polymer Hydrogel as Water Retention Material and Slow-Release Fertilizer. Ind. Crops Prod. 2021, 165, 113445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Gupta, R.; You, S. Machine Learning Assisted Prediction of Biochar Yield and Composition via Pyrolysis of Biomass. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 359, 127511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukoba, K.; Jen, T.-C. Biochar and Application of Machine Learning: A Review; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Tong, Z.; Meng, S.; Li, Y.C.; Gao, B.; Bayabil, H.K. Characterization of Residues from Non-Woody Pulping Process and Its Function as Fertilizer. Chemosphere 2021, 262, 127906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Choudhury, B.; Hazarika, S.; Mishra, V.; Laha, R. Long-Term Effect of Organic Fertilizer and Biochar on Soil Carbon Fractions and Sequestration in Maize–Black Gram System. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2023, 14, 23425–23438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masís-Meléndez, F.; Segura-Chavarría, D.; García-González, C.A.; Quesada-Kimsey, J.; Villagra-Mendoza, K. Variability of Physical and Chemical Properties of TLUD Stove Derived Biochars. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Kwak, J.-H.; Chang, S.X.; Gong, X.; An, Z.; Chen, J. Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Forest Soils Reduced by Straw Biochar and Nitrapyrin Applications. Land 2021, 10, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Y.; Ji, B.; Cui, B.; Shi, Y.; Wang, J.; Hu, M.; Luo, S.; Guo, D. Almond Shell-Derived, Biochar-Supported, Nano-Zero-Valent Iron Composite for Aqueous Hexavalent Chromium Removal: Performance and Mechanisms. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, J.; Li, J.; Song, S.; Zhou, Y.; Li, L. Electrolyte-Dependent Supercapacitor Performance on Nitrogen-Doped Porous Bio-Carbon from Gelatin. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-H.; Lin, H.-H.; Jien, S.-H. Effects of Biochar Application on Vegetation Growth, Cover, and Erosion Potential in Sloped Cultivated Soil Derived from Mudstone. Processes 2022, 10, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahedi, R.; Rasouli-Sadaghiani, M.H.; Barin, M.; Vetukuri, R.R. Effect of Biochar and Microbial Inoculation on P, Fe, and Zn Bioavailability in a Calcareous Soil. Processes 2022, 10, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagemann, N.; Spokas, K.; Schmidt, H.-P.; Kägi, R.; Böhler, M.A.; Bucheli, T.D. Activated Carbon, Biochar and Charcoal: Linkages and Synergies across Pyrogenic Carbon’s ABCs. Water 2018, 10, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalu, S.; Simojoki, A.; Karhu, K.; Tammeorg, P. Long-Term Effects of Softwood Biochar on Soil Physical Properties, Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Crop Nutrient Uptake in Two Contrasting Boreal Soils. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2021, 316, 107454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutuma, B.; Sylla, N.; Bubu, A.; Ndiaye, N.; Santoro, C.; Brilloni, A.; Poli, F.; Manyala, N.; Soavi, F. Valorization of Biodigestor Plant Waste in Electrodes for Supercapacitors and Microbial Fuel Cells. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2111.01434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köppel, M.; Witzig, N.; Klausmann, T.; Cerrato, M.; Schweitzer, T.; Weber, J.; Yilmaz, E.; Chimbo, J.; Campo, B.; Davila, L.; et al. Predicting NOx Emissions in Biochar Production Plants Using Machine Learning. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.07881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiest, G.; Nolzen, N.; Baader, F.; Bardow, A.; Moret, S. Low-Regret Strategies for Energy Systems Planning in a Highly Uncertain Future. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.13277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosenzo, S. Evaluating Sugarcane Bagasse-Based Biochar as an Economically Viable Catalyst for Agricultural and Environmental Advancement in Brazil Through Scenario-Based Economic Modeling. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.12454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ethaib, S.; Omar, R.; Kamal, S.M.M.; Awang Biak, D.R.; Zubaidi, S.L. Microwave-Assisted Pyrolysis of Biomass Waste: A Mini Review. Processes 2020, 8, 1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, S.; Havlik, P.; Soussana, J.-F.; Levesque, A.; Valin, H.; Wollenberg, E.; Kleinwechter, U.; Fricko, O.; Gusti, M.; Herrero, M.; et al. Reducing greenhouse gas emissions in agriculture without compromising food security? Environ. Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 105004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, H.U.; Allevato, E.; Vaccari, F.P.; Stazi, S.R. Biochar Aged or Combined with Humic Substances: Fabrication and Implications for Sustainable Agriculture and Environment—A Review. J. Soils Sediments 2024, 24, 139–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rumaihi, A.; Shahbaz, M.; McKay, G.; Mackey, H.; Al-Ansari, T. A Review of Pyrolysis Technologies and Feedstock: A Blending Approach for Plastic and Biomass towards Optimum Biochar Yield. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 167, 112715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaniyan, J.O.; Isimikalu, T.; Raji, B.; Affinnih, K.; Alasinrin, S.Y.; Ajala, O. An Investigation of the Effect of Biochar Application Rates on CO2 Emissions in Soils under Upland Rice Production in Southern Guinea Savannah of Nigeria. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oo, A.; Sudo, S.; Win, K.; Shibata, A.; Gonai, T. Influence of Pruning Waste Biochar and Oyster Shell on N2O and CO2 Emissions from Japanese Pear Orchard Soil. Heliyon 2018, 4, e00568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Marchant-Forde, J.N.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y. Effect of Cornstalk Biochar Immobilized Bacteria on Ammonia Reduction in Laying Hen Manure Composting. Molecules 2020, 25, 1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paladino, G.L.; Dupaul, G.; Jonsson, A.; Haller, H.; Eivazi, A.; Hendenstrom, E. Selecting Effective Plant Species for the Phytoremediation of Persistent Organic Pollutants and Multielement Contaminated Fibrous Sediments. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2025, 37, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsadik, A.; Akintunde, O.O.; Habibi, H.R.; Achari, G. PFAS in Water Environments: Recent Progress and Challenges in Monitoring, Toxicity, Treatment Technologies, and Post-Treatment Toxicity. Environ. Syst. Res. 2025, 14, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatsa, T.M.; Kelile, A.W.; Beyene, E.G.; Shanko, M.M. Production and Comprehensive Analysis of Biodiesel from Dovyalis caffra Seed Oil. Sustain. Energy Res. 2025, 12, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, L. Regulation of Sulfur Molecules for Advanced Lithium–Sulfur Batteries: Strategies, Mechanisms, and Characterizations. Surf. Sci. Tech. 2024, 2, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irshad, M.A.; Hussain, A.; Nasim, I.; Nawaz, R.; Mutairi, A.A.A.; Azeem, S.; Rizwan, M.; Hussain, S.A.A.; Irfan, A.; Zaki, M.E.A. Exploring the Antifungal Activities of Green Nanoparticles for Sustainable Agriculture: A Research Update. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2024, 11, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminurrasyid, A.H.B.; Ikmal, A.M.; Nadarajah, K.K. The Rice-Microbe Nexus: Unlocking Productivity Through Soil Science. Rice 2025, 18, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovuoraye, P.E.; Ugonabo, V.I.; Fetahi, E.; Chowdhury, A.; Tahir, M.A.; Igwegbe, C.A.; Dehgani, M.H. Machine Learning Algorithm and Neural Network Architecture for Optimization of Pharmaceutical and Drug Manufacturing Industrial Effluent Treatment Using Activated Carbon Derived from Treculia africana. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2023, 70, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.; Lim, J.Y.; Igalavithana, A.D.; Hwang, G.; Sang, M.K.; Masek, O.; Ok, Y.S. AI-Guided Investigation of Biochar’s Efficacy in Pb Immobilization for Remediation of Pb Contaminated Agricultural Land. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2024, 67, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyanka, G.; Singiri, J.R.; Adler-Agmon, Z.; Sannidhi, S.; Daida, S.; Novoplansky, N.; Grafi, G. Detailed Analysis of Agro-Industrial Byproducts/Wastes to Enable Efficient Sorting for Various Agro-Industrial Applications. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2024, 11, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baig, K.S. Interaction of Enzymes with Lignocellulosic Materials: Causes, Mechanism and Influencing Factors. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2020, 7, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, Q.; Wan, Y.; Cao, C.; Bai, J.; Wang, R.; Zhao, Y. Effect of Passivator DHJ-C on the Growth and Cadmium Accumulation of Brassica napus in Cd-Contaminated Soil. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2021, 64, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Cedillo, E.E.; González-Chávez, M.M.; Handy, B.E.; Quitana-Olivera, M.F.; Lopez-Mercado, J.; Cardenas-Galindo, M.G. Acid-Catalyzed Transformation of Orange Waste into Furfural: The Effect of Pectin Degree of Esterification. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2024, 11, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, H.J.; Ro, H.S.; Kawauchi, M.; Honda, Y. Review on Mushroom Mycelium-Based Products and Their Production Process: From Upstream to Downstream. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2025, 12, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]