1. Introduction

Accurate estimation of orchard block planting year, and consequently age, is crucial for various aspects of agricultural management, environmental assessment, and economic planning. The age of an orchard block significantly influences its productivity, carbon sequestration potential, water requirements, and susceptibility to pests and diseases [

1,

2,

3]. In the Australian macadamia industry specifically, reliable planting year data underpins accurate yield forecasting, resource allocation, and market planning [

4]. By integrating tree census records (e.g., planting dates) with models that account for climatic variability, stakeholders can better predict annual yield fluctuations, stabilize prices, and strengthen industry resilience [

5]. As global demand for macadamia nuts continues to rise, there is an increasing need for reliable, large-scale methods to map and monitor orchards across diverse landscapes.

Traditional methods for estimating orchard age, such as field surveys and manual interpretation of aerial imagery, are time-consuming, costly, and often impractical for large areas. Earth observation data provides extensive temporal and spatial coverage, making it a powerful tool for broad-scale orchard mapping. Satellite systems such as MODIS, Landsat, and Sentinel-2 offer varying spatial resolutions and historical records. MODIS provides daily global coverage at 250–1000 m resolution since 2000, which is valuable for regional-scale vegetation monitoring. However its coarse spatial resolution limits its use for individual orchard mapping [

6]. Landsat has provided a continuous global record since 1972 (60–80 m MSS initially), with 30 m multispectral observations from Landsat-4/5 TM, Landsat-7 ETM+, and Landsat-8/9 OLI; this archive is extensively used for land-cover mapping, including orchard delineation [

7]. For instance, Brinkhoff & Robson [

8] utilised over 30 years of Landsat imagery to estimate macadamia orchard planting years in Australia, demonstrating the potential of long-term satellite time series for orchard age estimation at a national scale. Sentinel-2, launched in 2015, provides 10–20 m resolution imagery with 5-day revisit, making it suitable for detailed orchard mapping, although its shorter historical record limits long-term studies [

9].

Integrating multiple data sources has emerged as a strategy to overcome limitations of individual sensors and improve mapping accuracy. Claverie et al. [

10] demonstrated the potential of combining high-resolution Sentinel-2 data with moderate-resolution MODIS data for improved crop-type mapping. In terms of predicting the tree-planting date from earth observation data, a study using a time series of Landsat NDVI on almond orchards in California, Chen et al. [

11] achieved high predictive accuracy, with a mean absolute error of less than half a year and an

of 0.96 at the orchard block level. This approach was facilitated by the availability of detailed block-level planting data, that supported precise model training and validation within a geographically limited area. A further study by Zhou et al. [

12] identified that young plantations often lack sufficient canopy cover to be detected as tree categories in land cover maps, leading to underestimation of newly planted areas.

The spatial resolution of satellite imagery can result in mixed pixels, particularly for smaller blocks or those with wide row spacing, complicating accurate mapping [

8]. Distinguishing between different tree crops with similar spectral and phenological characteristics also presents a challenge when attempting to predict the tree planting of orchards at a regional or national scale [

12]. Additionally, seasonal vegetation changes, especially during critical growth periods, may not be adequately captured by current satellite revisit times, affecting the accuracy of phenological assessments and age estimations [

13].

Deep learning models have demonstrated their capability to detect subtle temporal trends in multi-temporal datasets by leveraging automated feature extraction to capture complex dynamics without relying on predefined rules or manual engineering. Zhong et al. [

14] highlighted the effectiveness of CNNs (Conv1D) in identifying fine-grained temporal patterns in Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI) time series, where lower layers of the network detect small-scale temporal variations while upper layers summarise broader seasonal trends. Additionally, Zhong et al. [

14] demonstrated that deep neural networks applied to multi-temporal datasets can capture nuanced spectral and temporal trends in crop classification tasks, suggesting that faint signals—such as planting rows or emerging saplings—could likewise be identified in newly planted orchards. Similarly, Kussul et al. [

15] emphasised the ability of deep learning to discern smaller distinctions in land cover through extensive feature extraction and pattern recognition, illustrating how these methods can adapt to diverse agricultural contexts. Together, these findings indicate that deep learning approaches need not wait for clear canopy signatures or dramatic land-cover changes but can instead harness subtle indicators in remote sensing data to detect the planting and early growth of orchard crops. This adaptability underscores their potential to improve orchard monitoring and management by identifying transitions related to orchard establishment before dense canopies fully develop, offering significant advantages for agricultural applications.

Despite significant progress in broad-scale orchard mapping and planting year estimation, several challenges remain unaddressed. Accurate detection and age estimation of young orchard blocks are difficult due to insufficient canopy cover and subtle spectral signatures, leading to underrepresentation in mapping efforts. Existing models often struggle to generalise across different geographical regions and orchard types because of variability in environmental conditions and management practices [

16]. Additionally, combining different data sources introduces complexities related to data alignment, scaling, and fusion methodologies. Whilst in Australia, the extent (location and area) of all commercial macadamias has been mapped in recent years [

17], a similar comprehensive dataset of block-level information such as planting date, variety etc. is yet to be developed. Without consistent nation-wide producer-supplied block-level data to apply model predictions to, alternative approaches must be employed, such as pixel-level analysis using available satellite data.

Orchard-level (block-aggregated) targets offer interpretability aligned with management units and can smooth within-block variability, but aggregation can mask sub-block heterogeneity and can inflate apparent accuracy when training and testing share regional conditions [

18]. In this context, per-pixel temporal modelling at the observation scale treats each pixel as an independent sequence, preserving fine-scale dynamics relevant to planting year signals while avoiding block averaging and increasing the potential information content available [

19]. However, this approach assumes pixel independence, which may not hold due to spatial autocorrelation within blocks. Balancing these trade-offs is crucial for developing robust models that generalise well across diverse orchard conditions.

This study therefore bridges the gap between prior block-level analyses and fine-grained, national-scale mapping by formulating planting year estimation at the pixel level. Constrained by the absence of uniform, producer-supplied block labels nationwide and the generalised nature of ATCM polygons, the approach treats each Landsat pixel as an independent temporal sequence (1988–2023 DEA annual geomedians) within mapped orchard extents. This design preserves sub-orchard heterogeneity while enabling large-sample training across regions. Generalisation is assessed under a strict region-held-out (LOROCV) protocol to reflect out-of-region deployment, and block-level summaries (medians of pixel predictions) are reported as secondary, management-facing aggregates.

In this context, this study compares machine learning and deep learning models for macadamia orchard planting year estimation across Australia. Traditional machine learning approaches, such as Random Forests and Gradient Boosting Machines are evaluated and compared with advanced deep learning models, including Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) and Temporal Convolutional Networks (TCN). By utilising multi-temporal satellite imagery from Landsat, the study aims to leverage the long-term historical data provided by the sensors. Hyperparameter tuning techniques, including the use of Keras Tuner [

20], are employed to optimise model architectures for each growing region. Additionally, this study aims to improve the accuracy of planting year predictions, particularly for recently planted orchards under three years old, by incorporating both Landsat spectral data and temporal pattern analysis. By integrating machine and deep learning models with satellite imagery, this study aims to improve the accuracy of macadamia orchard block planting year estimation across Australia. The findings will provide valuable insights for industry stakeholders, enhancing yield forecasting, resource management, and agricultural sustainability. Additionally, the research has the potential to inform decision-making at both farm and industry levels, supporting biosecurity preparedness, natural disaster response and recovery, and long-term agricultural planning.

2. Materials and Methods

In this study, multiple machine learning models were developed and evaluated to predict crop planting years from multi-temporal satellite imagery. The methodology included data preparation, hyperparameter tuning, model training, evaluation, and comparative analysis of model configurations. The top-performing models were subsequently applied to the Australian Tree Crop Map (ATCM) [

17] to derive nation-wide statistics on planted area by year. An overview of the end-to-end workflow is provided in

Figure 1.

2.1. Study Area

The study area encompassed all macadamia orchards defined by ATCM, from Tropical Queensland to New South Wales Mid North Coast in the east and South West Western Australia (

Figure 2). The spatial extent of the industry-defined growing regions was built from Local Government Area (LGA) and postcode boundaries. The regions vary in climate, soil type, and management practices, influencing the growth and development of macadamia orchards. The geographic diversity of these regions provides an ideal setting for evaluating model performance across different environmental conditions and management practices.

2.2. Input Data

Compiling the input data required information about existing macadamia block planting years (labels) and a time series of satellite data (imagery). The input data labels were derived from polygon vectors with a planting year attribute, which were supplied by growers and industry bodies. For each block, the planting year was converted into a block age, with 1 representing the most recent year and increasing sequentially for earlier years. The block age was then used as the label for training the models.

The Landsat yearly geometric median, spanning from 1988 to 2023, were extracted from Digital Earth Australia’s (DEA) Data Cube [

21] for all macadamia blocks and formed the basis of the training, validation, and test data. These data, offering temporally consistent median composites, are useful for tracking long-term land cover changes, including orchard establishment. The data consists of six spectral bands (blue, green, red, near-infrared, shortwave infrared 1, and shortwave infrared 2). The Normalised Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) [

22] and Green Normalised Difference Vegetation Index (GNDVI) [

23] values were calculated for each pixel. The training data were segmented by growing region, shown in

Figure 2.

Table 1 shows the number of blocks with planting date information for each region. In total, there were 422 blocks with known planting dates.

In this study, individual pixel time series within the training-block boundaries were used. Pixels were included only when the pixel centre lay within the block polygon (i.e., no edge-touch pixels were taken), which functions as an implicit edge filter to reduce boundary mixing and label noise at block margins. Deep learning models typically require substantial data to learn generalisable patterns; using per-pixel sequences increases the number of training instances from 422 blocks to 60,405 pixels (

Table 1). However, due to spatial autocorrelation among pixels within the same block, this increase does not translate linearly into independent information [

19]. This granular sampling strategy aligns with recommendations to maximise sample size to improve reliability and generalisability [

24]. To ensure adequate data coverage while limiting regional imbalance, regions with fewer than 3000 pixels (Lismore, Macksville, Maclean, South East Queensland, and Western Australia) were grouped into an “Other Regions” category for modelling.

Features are drawn from the full historical sequence (1988–2023) to reconstruct the planting year retrospectively; the system is not designed as an as-of-year operational forecaster. Annual DEA geomedians are computed per calendar year and then stacked temporally; no future information is introduced within-year, but the multi-year context includes post-planting observations.

2.3. Data Sampling

A Leave-One-Region-Out Cross-Validation (LOROCV) approach was implemented to enhance the model’s ability to generalise across diverse geographies. As highlighted by Lyons et al. [

25], splitting the data this way ensures robust cross-validation essential for accurate assessment of a model’s ability to generalise geographically. Each model was trained on all regions except the one reserved for validation or testing [

26]. The withheld region’s pixels were split into two datasets: a validation dataset, which was used exclusively for the ‘early stopping’ and ‘reduce learning rate on plateau’ callbacks to determine when to stop training or reduce the learning rate, and a test dataset, which was used for final model evaluation. While the test dataset remained geographically distinct from the training data, its independence from the validation set depends on the degree of spatial autocorrelation within the withheld region. This evaluation approach aligns with best practices in spatial machine learning, ensuring that model performance is assessed on data not used for weight updates or direct optimisation.

Table 2 shows the number of training, validation, and test pixels across models, detailing pixel allocation for each region in the LOROCV process, which adheres to best practices in evaluating spatial datasets.

2.4. Machine Learning Models

To determine the best approach to predict the age of macadamia orchard pixels, range of machine learning and deep learning models were evaluated. The models encompass both traditional and advanced techniques, each with unique mechanisms for handling temporal data.

Table 3 lists the ten model types trialled in this study. This comprehensive evaluation aims to identify the most effective model for accurate and reliable prediction of macadamia orchard planting years.

2.5. Hyperparameter Tuning

Hyperparameter tuning plays a critical role in this process, ensuring models do not overfit or underfit to training data. In this application, the model configurations are tuned to ensure spatial generalisability. By exploring the hyperparameter space for each region, the most effective settings for each model type can be determined, ensuring robust and reliable predictions that account for geographic and temporal diversity. This tailored approach aims to maximise model performance in mapping orchard planting dates with precision across varied landscapes. Details of the search space for each of the model types can be found in

Appendix A.

2.5.1. Thresholding Approach

As a simple baseline for comparison with more complex algorithms, a method similar to [

8] was implemented at the

pixel level (rather than the block level) to align with the study objective of pixel-level planting year estimation and with the other model types. For each pixel, the planting year was estimated as the year in which a vegetation index (VI) first crossed a specified threshold in its time series. Threshold values from

to

(step

) were explored for both NDVI and GNDVI. Recognising that specific thresholds may correspond to orchards of differing ages, integer “delta” adjustments from

to

years were applied to the crossing year. For each combination of VI, threshold, and delta, planting year predictions were generated and evaluated against planting records using standard metrics; the combination minimising root mean squared error (RMSE) was selected.

2.5.2. Machine Learning Approach

Hyperparameter tuning was conducted to enhance model performance for macadamia orchard planting year estimation. Tree-based models were optimised with scikit-learn’s

RandomizedSearchCV [

36], and deep learning models with Keras Tuner [

20]. For tree-based models, parameter distributions included the number of estimators, maximum depth, learning rate, and regularisation parameters (

Appendix A). The search spanned 50 iterations with threefold cross-validation to promote robust selection.

For neural network architectures, Keras Tuner

HyperModel classes targeted key hyperparameters, including the number of layers, units per layer, dropout rates, activation functions, and optimiser settings (

Appendix A). Bayesian optimisation was used to explore the hyperparameter space, with up to 50 trials initialised by five random points. During tuning, performance was assessed on validation data with early stopping (patience 5) to avoid unnecessary training. The total number of trained models is summarised in

Table 4. This systematic procedure refined model performance and supported accurate predictions across regions.

2.6. Model Evaluation

Evaluation followed a Leave-One-Region-Out cross-validation (LOROCV) scheme in which, for each fold, one growing region was held out entirely for testing and all remaining regions supplied training/validation data. This setup assesses spatial generalisation to unseen geographic conditions and reduces overfitting to regional characteristics. Hyperparameters were tuned using only the non-held-out regions for each fold; the held-out region remained untouched until the final test.

Performance was quantified using mean absolute error (MAE), root mean square error (RMSE), and the coefficient of determination (

) [

37]. For each model type and region, the top five hyperparameter settings (selected by the lowest validation MAE) were retrained for up to 100 epochs with early stopping (patience 10) and learning-rate reduction on plateau (factor 0.1, patience 5). Each region-model-hyperparameter combination was trained five times with different random initialisations to characterise variability due to stochastic optimisation. The resulting five test scores per configuration were averaged, and the best hyperparameter setting and checkpoint were retained for each region-model pair.

To summarise overall behaviour, metrics were aggregated to report the mean and standard deviation of MAE, RMSE, and across runs and regions. For like-for-like comparison among model types, regional test predictions were also concatenated to form a unified test set per model. Consistent with the retrospective formulation, evaluation uses the full multi-year context; region-held-out (LOROCV) metrics are treated as the primary measure of spatial generalisation, with block-level random-split results reported only as supplementary context because shared regional conditions can yield optimistic error estimates.

2.7. Model Application

To generate national planting year maps, Landsat annual geometric medians from Digital Earth Australia (1988–2023) were extracted for all macadamia orchard areas delineated in the ATCM. Pixels were included only when the pixel centre lay within an ATCM orchard polygon (no edge-touch pixels), providing an implicit edge filter that reduces boundary mixing. As the ATCM polygons are generalised with a minimum mapping unit of approximately 1 ha and may aggregate neighbouring blocks/orchards into a single feature [

8], planting year estimation was performed at the pixel level to retain sub-orchard heterogeneity within the mapped extent, acknowledging that polygon boundaries may not coincide exactly with management units.

The top-performing model type was identified from the LOROCV comparison. For deployment, a single model was then trained on the combined multi-region dataset using a block-level randomised split (80/10/10 for train/validation/test), ensuring validation and test blocks were spatially independent from training blocks while maximising training volume. Training proceeded for up to 200 epochs with early stopping (patience 10; minimum MAE improvement 0.001) and learning-rate reduction on plateau (factor 0.1; patience 5). The best checkpoint on the validation set was retained.

The final model was applied to every eligible Landsat pixel within ATCM orchard boundaries nationwide, producing pixel-level planting year estimates. Regional rasters were mosaicked and merged into a single, spatially explicit dataset covering all growing regions. For management-facing summaries, pixel-wise estimates within each orchard block were aggregated by the median to provide a block-level value while preserving the underlying pixel-level maps. Outputs were vectorised and clipped to ATCM boundaries so that partial pixels intersecting orchard edges were split in the final vector product. Regional summaries and cumulative planted-area curves were then generated to visualise spatio-temporal patterns, and an interactive web map was produced for exploratory access to the results.

2.8. Computing Infrastructure

All model hyperparameter tuning, training and evaluation were conducted on a high-performance computing (HPC) system running a 64-bit Linux-based operating environment, featuring an Intel Xeon Processor (Icelake) with 16 physical cores (2793.35 MHz). The system contained 251 GB of RAM and was equipped with an NVIDIA A100 PCIe 40 GB GPU (CUDA Version 12.6), optimised for deep learning computations. The Python environment, was built around Python 3.9.19, with essential packages including TensorFlow (Version 2.15.1) for deep learning model construction, Rasterio (Version 1.3.11) and Geopandas (Version 1.0.1) for geospatial data processing, and Matplotlib (Version 3.9.2) and Seaborn (Version 0.13.2) for visualisation. The environment also included libraries such as Scikit-Learn (Version 1.5.2) and Pandas (Version 2.3.1) for machine learning and data handling, respectively.

2.9. Use of Generative AI Tools

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT 4 (OpenAI, 2024) to assist with language refinement, including grammar and phrasing. The authors reviewed and edited the content produced by the tool and take full responsibility for the final text.

4. Discussion

This study presents a method to improve macadamia orchard planting year predictions using satellite-image time series and deep learning. Accurate planting year data are essential for yield forecasting and resource planning at both orchard and industry scales; knowing precisely when trees were established can significantly enhance yield models and market forecasts [

4]. The final model was applied to predict the planting year for all pixels within Australian macadamia orchards mapped in the ATCM [

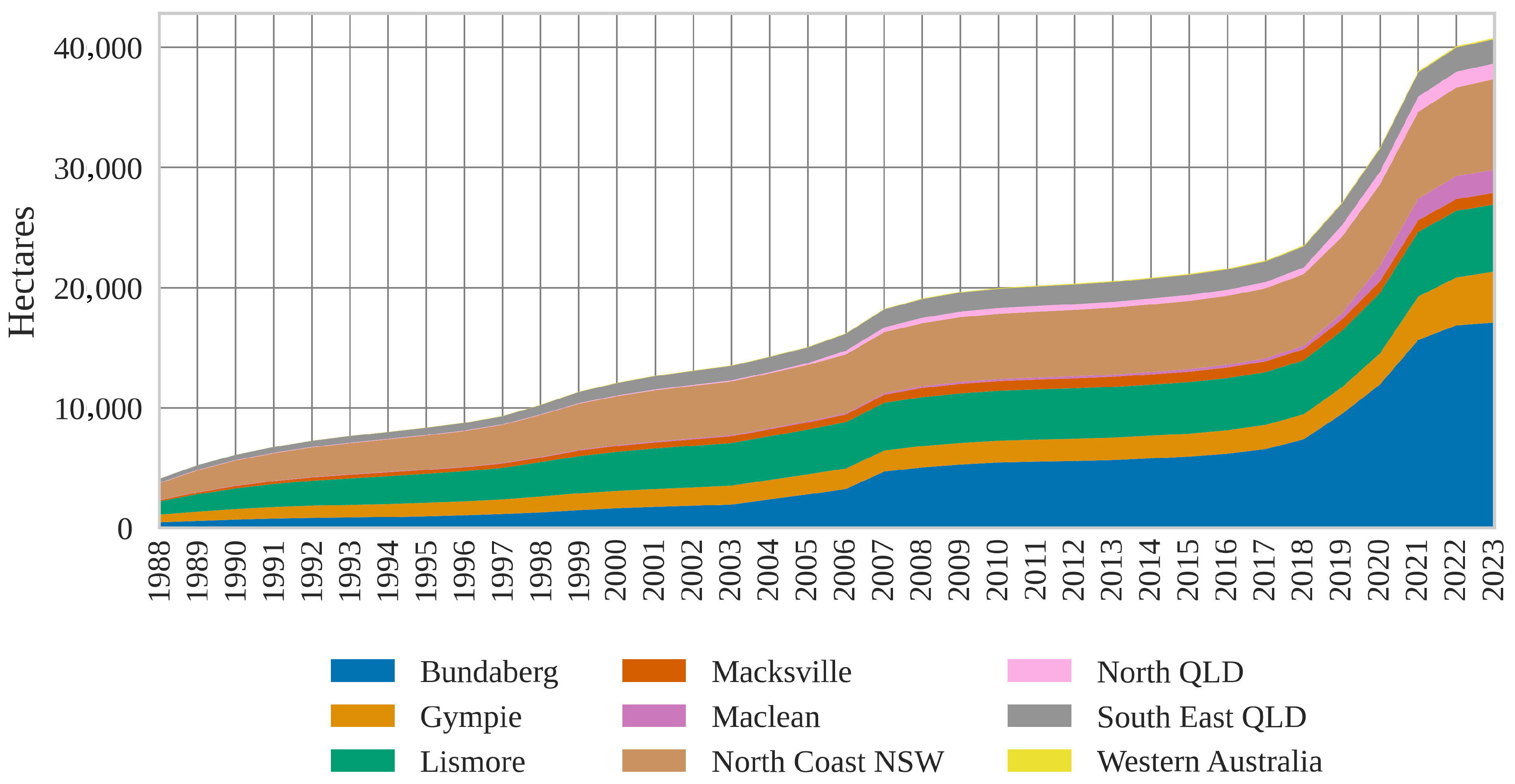

17]; the resulting estimates reveal region-specific planting trends over time. The cumulative planting area over time (

Figure 11) indicates substantial increases in planting areas across all regions in recent years (2018–2023), especially in the Bundaberg and Gympie growing regions. However, it is important to note that this analysis only considers macadamia orchards represented in the ATCM. Macadamia blocks that have been removed over time are not accounted for in the plot, meaning the cumulative areas shown do not reflect historical orchards that were planted and subsequently removed. This omission potentially leads to an underestimation of total planting activity over the years if used in this way.

Deep learning models demonstrated significant advantages over traditional methods like thresholding, RF, and GBT in predicting planting dates from satellite imagery. A key strength of deep learning is its ability to learn complex, abstract features directly from the imagery, capturing not only visible land-clearing events but also subtle changes in vegetation dynamics indicative of orchard establishment. Unlike thresholding, which relies on simple, predefined rules, and traditional machine learning models that depend heavily on engineered features, deep learning models can automatically identify intricate temporal and spatial patterns in the data [

38]. Across regions held out entirely for testing (LOROCV), all deep models achieved MAE < 1.5 years except TCN (

Figure 4); GRU and LSTM performed best at 1.2 years, improving on the macadamia-specific block-level benchmark of ∼1.7 years reported by Brinkhoff & Robson [

8]. When predictions are aggregated to blocks and evaluated under a block-level random split, MAE decreases to 0.6–0.7 years, approaching the <0.5 years reported by Chen et al. for almonds in a geographically compact, densely labelled setting [

11]; this alignment is consistent with the effects of target aggregation and evaluation design (random splits admit regional feature sharing, whereas out-of-region tests do not). The consistently strong performance across deep architectures suggests that modelling temporal trends is central to success, yet the observed plateau indicates limits imposed by current data coverage. Expanding the spatial and temporal diversity of training data is therefore likely to yield further gains and more reliable estimates across diverse growing conditions.

The thresholding approach, which relied on identifying specific GNDVI values to determine orchard age, performed remarkably well. This simple approach proved effective for detecting orchards within an age range (>3 years), particularly when strong spectral signals were present. Nonetheless, it is inherently limited in its ability to generalise across diverse planting scenarios or account for more subtle temporal changes. In contrast, deep learning models utilised multi-year spectral patterns and temporal context. This suggests that deep learning models may accurately determine orchard age and planting year, even in cases where complex or subtle temporal dynamics were involved. Tree-based methods like RF and GBT offered moderate performance but were inherently constrained by their inability to model temporal dependencies effectively for this type of application.

The hyperparameter optimisation in this study was limited to a maximum of 50 trials, which, while sufficient to identify a set of effective hyperparameters, may not have fully explored the parameter space. It is possible that other hyperparameter combinations, beyond those tested, could yield improved model performance. Additionally, the training process may not have allowed sufficient time for some models, particularly larger and more complex architectures like the Temporal Convolutional Network (TCN), to converge and minimise error. The TCN’s consistently poor performance could be attributed to this limitation, as its greater complexity likely requires extended training to fully leverage its capacity to model temporal patterns [

33]. Future work should consider increasing the number of hyperparameter trials and allocating additional training time to ensure that models achieve optimal performance.

Accurately modelling planting dates for macadamia orchards across Australia’s diverse growing regions depends on a balanced and representative training dataset. The limited data availability before the 2000s (

Figure 3), both temporally and geographically, presents challenges for predicting planting years in these earlier periods. Model performance is constrained by limited historical data, especially in regions with fewer pixels, which can reduce accuracy for years and regions that are sparsely represented in our dataset. Geographic and temporal imbalances identified in this study have influenced model performance, highlighting the need to address these challenges. Models with smaller validation and test datasets, such as the model with Other Regions withheld, exhibited high prediction inaccuracies even when overall errors were low (

Figure 7), limiting the ability to learn region-specific features from other regions and thereby impacting generalisability. The merging of smaller regions appears to have created a class with greater geographical variability, leading to higher errors when validated and tested in these areas. Similarly, the concentration of available data in recent years (2017–2023) and earlier peaks (2004–2008) (

Figure 3) creates a temporal imbalance: MAE is lower in these well-sampled periods and higher for planting years with sparse data (

Figure 6). Enhancing data collection for under-represented regions and historical periods is essential to improve predictive accuracy and robustness. Collaborative efforts with industry are underway to address data gaps, with future work aiming to incorporate a larger, more comprehensive dataset that better represents growing regions both spatially and temporally. No explicit temporal or spatial reweighting was applied in this study, so estimates reflect the empirical sampling distribution (skewed toward recent years and larger regions), which helps explain higher errors for sparsely represented pre-2000 planting years. To mitigate this in future work—particularly if additional data further over-represents recent plantings or specific regions—we will evaluate (i) temporal reweighting to equalise the effective sample size per planting year bin, (ii) region-aware weighting to reduce dominance by data-rich regions, and (iii) stratified mini-batching so each update includes a balanced mix of years and regions. These adjustments are designed to improve reliability for under-represented years and locales without altering the retrospective formulation or the LOROCV evaluation protocol.

The lower errors in

Figure 8 compared to

Figure 4 can be explained by differences in data splitting. In

Figure 4, the data were split at the regional level, so the model was tested on entire growing regions held out from training. This forces the model to generalise to unseen geographical conditions, often increasing error. By contrast,

Figure 8 used block-level splitting, meaning the model still saw data from the same region during training (just not from those specific blocks). Consequently, the model encounters less overall variation at test time, leading to lower error estimates. This optimism arises from regional feature sharing (e.g., climate regimes, soils, management practices, sensor/viewing geometry) that the model can exploit under random splits, but which is intentionally broken by region-held-out evaluation.

Figure 8 compares the GRU model against the threshold-based method initially described by Brinkhoff & Robson [

8]. In that previous work, orchard-level (i.e., block-averaged) data were used to define NDVI/GNDVI thresholds, whereas this study derived them from pixel-level data for a more direct comparison with the deep learning approaches. An immediate consequence of moving to pixel-level analysis is that orchards planted in a single year can exhibit varied reflectance signals across different pixels, reflecting factors like row spacing, canopy density, or management zones.

Figure 9 shows the performance of each model when each block value is the median of all pixel-level predictions. This block-level perspective helps to smooth out within-orchard variability, because a single orchard-level estimate is taken from the median of all pixel-level predictions. Consequently, the block-level results (

Figure 9) tend to cluster more tightly around the diagonal and show slightly improved

value, indicating robust orchard-wide estimates. However, as noted, this aggregation can mask important sub-orchard differences—such as new rows or partial replanting within older blocks—which are clearly captured in pixel-level analysis (

Figure 8). Thus, although a block-level summary may align well with farm management units and simplify interpretation, the richer pixel-level approach offers finer spatial resolution of canopy development and highlights heterogeneity arising from row spacing, uneven planting, or distinct management zones within the same orchard block.

In this study, a single GRU model was utilised for planting year predictions. Future research should consider implementing probabilistic modelling techniques, as outlined by [

25]. By training multiple models on various data subsets using methods such as k-fold cross-validation or bootstrapping, it is possible to generate probabilistic estimates for each pixel’s planting year. Aggregating these estimates would create a map indicating the likelihood of planting in a given year for each pixel, providing both predictions and a measure of classification confidence. This approach addresses current limitations by highlighting areas with prediction uncertainty, particularly in regions with sparse or imbalanced data. It guides data collection efforts to improve model accuracy and mitigates data biases, offering more stable and accurate estimates of macadamia planting years across diverse regions. Incorporating these techniques aligns with best practices for remote sensing classification and accuracy assessment, thereby enhancing the reliability and interpretability of planting year predictions for improved agricultural management.

Implementing data augmentation strategies [

39] could enhance model performance across the entire time series. Furthermore, generating synthetic satellite imagery and corresponding planting year labels to mimic the spectral and temporal characteristics of historical orchards could expand the training dataset, thus reducing bias and improving model generalisability [

40,

41]. Moreover, moving from a pixel-based to a patch-based analysis offers promising improvements in prediction accuracy by incorporating the broader landscape context surrounding each pixel [

42]. This patch-based approach captures spatial relationships and patterns crucial for orchard age estimation, which may lead to more robust and reliable planting year predictions.

Future work could also examine simpler, transparent baselines alongside deep sequence models to contextualise national-scale feasibility. In particular, ordinary least squares and Elastic Net would provide like-for-like comparators under the same region-held-out (LOROCV) protocol. A targeted feature-set ablation could further quantify the contribution of (i) indices-only (NDVI/GNDVI), (ii) raw bands only, and (iii) bands+indices. Given the complementarity between broadband reflectances and vegetation indices, indices-only may underperform relative to bands+indices; empirical confirmation under identical training and evaluation settings would clarify these contributions.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated the effectiveness of using time-series Landsat imagery and advanced deep learning models to predict the planting years of macadamia orchards across multiple growing regions in Australia. By leveraging extensive satellite data spanning from 1988 to 2023 and state-of-the-art modelling techniques, a robust methodology has been developed for accurately mapping the age of macadamia orchards, addressing limitations in traditional orchard age estimation methods.

The predictive models developed in this study offer significant potential for enhancing agricultural planning, yield forecasting, and informed decision-making within the macadamia industry. Accurate orchard age information is invaluable for optimising resource allocation, pest and disease control, harvest and processing scheduling/planning. The integration of these insights into a dashboard-style mapping application shared with industry stakeholders provides a practical tool for real-world applications, facilitating ongoing collaboration and data expansion.

Future work should first address data limitations by expanding the geographic and temporal coverage of training samples, particularly in underrepresented regions and earlier planting years. To further refine planting year predictions, approaches such as probabilistic modelling [

25] could be employed, providing uncertainty estimates that highlight areas where predictions are less reliable. Implementing data augmentation strategies—for instance, generating synthetic satellite imagery—can increase the diversity of training examples and improve model robustness [

39,

40,

41]. Meanwhile, a patch-based analysis, which examines clusters of pixels rather than individual pixels, could capture broader spatial context and further enhance orchard age estimation [

42]. Finally, exploring advanced architectural designs (e.g., ensemble or hybrid deep learning) could further boost both accuracy and interpretability [

5].

Ultimately, this research contributes a scalable, adaptable framework for predictive modelling in precision agriculture. The methodologies and insights presented not only support the sustainability, profitability, and resilience of the macadamia industry in Australia but also offer a foundation for broader applications across other perennial crops and countries. By addressing key challenges and leveraging advancements in remote sensing and machine learning, this framework ensures the agricultural sector is better equipped to navigate future environmental and economic challenges.