Abstract

Citrus production in the Mediterranean area is of considerable importance, in both cultural and economic terms, and the viability of the industry greatly depends on proper phytosanitary management. In this review, we focus on exotic and emerging dangerous citrus viruses that have still not been reported in the countries of the Mediterranean area, that are not yet regulated or that are restricted to certain small areas. We also discuss the contribution that old and new technologies may offer for valuable surveys aimed at promoting the adoption and sharing of better control measures and the production of pathogen-tested citrus trees and rootstocks.

1. Introduction

Although there are no cultivated citrus trees with Mediterranean wild-type ancestors, in the last two millennia, citrus trees have become popularly associated with the region, and citrus cultivation continues to have considerable economic and cultural significance throughout the Mediterranean and in surrounding areas. The first Citrus species to reach the East Mediterranean shores was probably the Etrog citron (Citrus medica), brought over from Persia and Medea. Sour oranges (C. aurantium) and lemons (C. lemon) followed, whereas the arrival of sweet oranges (C. sinensis) apparently took place only after 1499, following the discovery of the European–Far East sea-line by Vasco de Gama from Portugal. Indeed, several languages, including Arabic and the Romanian, refer to oranges as ‘portucal’. Interestingly, for decades, the Mediterranean citrus industry flourished with the use of seedling trees, a practice that had to be changed following a further maritime development allowing the transfer of rooted plants and soil infested with Phytophthora. The oomycete that caused this serious decline through disease forced the introduction of grafting on the sour orange rootstocks found by Spanish horticulturists, to end the gummosis epidemic. Similar attempts to use sour orange rootstock conducted in South Africa and the Far East, including Australia and Java (now Indonesia), were unsuccessful due to the wide presence of both citrus tristeza virus (CTV) and its vector. It took years to realize that the use of sour orange as a successful rootstock in handling the gummosis problem was only because citrus plants originally imported from ancient regions were introduced as seeds and, hence, were free from graft-transmitted pathogens.

The considerable growth of citrus demand to supply vitamin C needs on the Europe–Far East routes considerably expanded cultivation, from that in home gardens and orangeries, the luxury structures used until the 19th century to protect orange and other fruit trees during the winter, to more intensive groves. Along with this came an interest in the introduction of new varieties for the botanical gardens that were replacing the private orangeries.

Initially, most of the Mediterranean citrus-producing countries developed their local orange (and, eventually, mandarin) selections. The Jaffa orange, for example, was the most popular variety from about the middle of the nineteenth century, developed in Palestine and later in Israel after its establishment in 1948. This situation continued for at least 30 more years. Other orange varieties, such as the Tarocco and Moro blood oranges, were popular in Sicily and Southern Italy, and other varieties of oranges in Spain and Morocco. A large change occurred with the establishment of the Riverside experiment station in California, a school where many advanced horticulturists throughout the Mediterranean were educated and thus brought home practices of variety collection and variety diversification. With diversification came the import of citrus budwoods infected by different viruses. In many of the citrus areas in the region, the arrival of tristeza occurred 20–30 years before the disease turned into an observable problem. This was partly due to the absence in the region of the most effective, citrus-specific and abundant vector of the virus, Aphis (Toxoptera) citricidus Kirkaldy.

Because, in the early period, the spread of Citrus spp. occurred mainly through fruits and seeds, most of the important citrus disease agents commonly found in China, India and other Far East countries were not carried along. This helped in preventing the spread in the Mediterranean basin of phloem-limited pathogens, such as CTV, and other graft-transmissible viruses and bacteria [1]. Later, in 1920s and 1930s, the expansion of citrus cultivation in the Mediterranean area was associated with the introduction of budwood of exotic citrus varieties. It was later discovered that Meyer lemon imported from China and kumquats and satsumas from Japan led to the geographic dispersion of the tristeza virus, although, at that stage, the disease remained unnoticed there [2]. Worldwide alarming reports were followed with national programs of CTV elimination, which revealed cases of diseased trees in several Mediterranean countries, although still restricted to the original imported propagations (Supplementary Figure S1). Later, bioindexing and ELISA assays have shown the exchange of propagative material infected by CTV continued for decades [3]. New technologies are helping now to get information about the introduction of other citrus viruses and viroids.

Once the scale of the threat had been perceived, the European Plant Protection Organization (EPPO) decided to conduct a survey of viral and viral-like diseases of citrus plants in the Mediterranean, conducted by the late Prof. I. Reichert (Agriculture Research Station, Rehovot, Israel). The study mission showed that the danger of citrus viral diseases threatened the entire region [4] and highlighted the need to establish uniform methods of indexing, diagnosis and nomenclature. These observations continue to be relevant, especially since globalization resulted in movement of people and goods and considerable advances in novel diagnostic technologies.

The most serious outbreak of tristeza in the Mediterranean region was noticed in the 1960s in Spain, where several millions of trees grafted on sour orange had succumbed to the disease. Replanting the old clone citrus trees with virus-free planting material generated considerable benefits for the citrus industry in terms of quantity and quality of fruits [5]. A few years later, when the epidemic developed in Israel, the relevant organization set up to eradicate the disease, eventually realized that the majority of the CTV isolates were poorly aggressive. However, once CTV became an observed threat, many of the Mediterranean countries established regulatory policies against the continuation of the use of sour orange as a rootstock, in favor of a replacement plan that has, to date, proven to be protective against CTV.

Today, the increased number of viruses and viroids affecting citrus [6], favored by climatic changes and increased activities through global markets, have increased the risk of the introduction of exotic pests and pathogens, which could spread from a single Mediterranean site to the whole region—a region producing more than 21% of the world’s citrus (Supplementary Table S1). Nevertheless, the current knowledge of the occurrence and geographical distribution, biological characteristics and molecular biological features of exotic and emergent citrus viruses and viroids relevant to the area is discontinuous and not homogeneous (Figure 1).

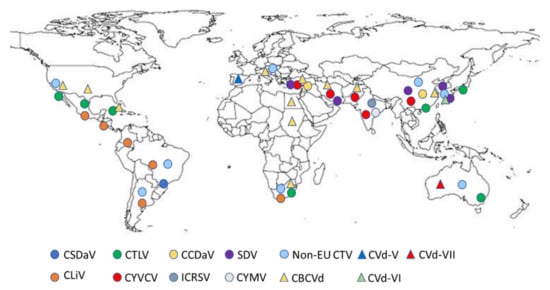

Figure 1.

Global distribution map of exotic citrus viruses and viroids relevant to the Mediterranean region (extracted from EPPO Global database 2021, accessed in July 2021). CSDaV, Citrus sudden death-associated virus; CTLV, Citrus tatter leaf virus; CCDaV, Citrus chlorotic dwarf-associated virus; SDV, Satsuma dwarfing virus; Non-EU CTV, stem pitting and resistance breaking citrus tristeza virus; CLiV, Citrus leprosis virus (sensu lato); CYVCV, Citrus yellow vein clearing virus; ICRSV, Indian citrus ringspot virus; CYMV, Citrus mosaic virus; CBCVd, Citrus bark cracking viroid; CVd-V, Citrus viroid V; CVd-VI, Citrus viroid VI; CVd-VII, Citrus viroid VII.

The guidelines for surveillance provided by the International Plant Protection Convention [7] suggest that researchers should consider whether a cooperative effort to collect and record data on pest presence or absence via surveys and monitoring or other procedures [8] would be strategically effective as a means of containing the spread of diseases within a country, as well as to prevent transborder movements among countries [9]. Such a program of surveillance requires a wide knowledge of the complex phytosanitary status of the citrus plants within each country and abroad, in order to focus on pests that are not known to be present in a specific area and to monitor the distribution of that specific pest of interest, or to carry out the identification of cases that would trigger further actions, in line with current international standards and a statistically sound and risk-based pest survey approach [10].

In this review, we focus on exotic, emerging dangerous and potential economically important citrus viruses that have still not been reported in countries in the Mediterranean area, that are not yet regulated or that are restricted within some small areas (Table 1, Figure 1). A literature and categorization search of bibliographic databases was conducted, using the European Food Safety Authority website (EFSA) (https://www.efsa.europa.eu/it accessed on 31 July 2021) and European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization (EPPO) Global Database [11]. We also discuss the contribution that old and new technologies may offer in relation to these issues.

Table 1.

List of exotic and emergent viruses relevant to the Mediterranean region as per the EPPO Global Database (accessed in July 2021) (and bibliographic database (in brackets)).

2. Citrus Viruses Recommended for Regulation as Quarantine Pests

2.1. Citrus Tristeza Virus (Closterovirus, Closteroviridae)

Citrus tristeza virus (CTV) is a positive-sense single-stranded genomic RNA of 19.3 kb encapsidated in the p25 major coat protein (95%) and the p27 minor coat protein (5%). The genome codes for 12 open reading frames (ORFs). Its phloem-associated virions consist of filamentous particles about 2000 nm long and 10–12 nm in diameter [12,13].

The host range of CTV is generally limited to Citrus species and their relatives, which are symptomless for many CTV isolates if the virus is on their own roots, although when grafted, they show a wide range of symptoms, depending on the scion–rootstock combination and the virus strains and isolates. The most characterized symptoms are quick decline (QD) and stem pitting (SP). Quick decline, known as tristeza, leads to the death of the plant grafted on sour orange; stem pitting is associated with sparse foliage and reduced yield and fruit quality, regardless of the rootstock. Some rootstocks themselves can be severely affected on the trunk and at the root level (such as alemow). A third symptom, termed seedling yellows (SY), is seen on sour orange, lemon and grapefruit seedlings in the greenhouse or on infected trees regrafted with these varieties [1,5].

Almost all Citrus and Fortunella species host the virus by means of natural infection, and several Rutaceae species, such as Aegle, Aeglopsis, Citropsis and others, as well as non-citrus species (Passiflora gracilis and P. coerulea), have been reported as experimental hosts (see Moreno et al. [5] for comprehensive reference lists) (Table 1). Their roles in the epidemiology of the disease have not been clarified, and this has led to several uncertainties regarding the regulation of their movement as ornamental species [14]. Studies on CTV revealed that the outcome of a CTV infection differs depending on the citrus host and CTV strain [15,16]. In addition, the replication of the virus isolates differs according to the citrus species and variety [17].

Due to the continuous advancement enabled by bioinformatics and new genomic technologies, the possible recombination sites of the CTV 5′ half have been identified, whereas the 3′ half (genes p23, p25, p18, etc.) sites of the genome seem to be far more conserved, probably reflecting the strictness imposed by the functional role of their expression products [15,18]. Distinct members of the same lineage sharing common ancestries share a strain or genotype [15]. The introduction of high-throughput sequencing technologies (HTS) for CTV isolate characterization increased the number of whole genomes sequenced, allowing novel reassessments of the phylogenetic relations of the CTV strains, and the proposal of adding four new strains (S1, L1, M1 and A18) [19,20] to the previous CTV strain catalogue (T36, VT, T3, RB, T68, T30 and HA16-5). To date (as of July 2021), a total of 81 whole-genome sequences of CTV isolates coming from different countries have been listed in the GenBank database (Supplementary Table S2) [15,16,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42]. Most of them are representative of the VT and RB genotypes followed by T30 and T36 (Figure 2). Only 13 isolates from the Mediterranean area have been fully sequenced. Nine of them are VT genotypes, two are T30, and two are T36. These figures indicate that our knowledge of the genetic structure of the CTV population in the Mediterranean region is limited compared with that of the wider global populations and is probably incomplete, with potential considerable epidemiological phytosanitary implications.

Figure 2.

Distribution of the 81 full genome sequences of CTV per genotype available in the GenBank (as of July 2021).

Regarding the epidemiology of the disease in the Mediterranean region, the virus is efficiently vectored by the cotton/melon aphid Aphis gossypii, whereas the more abundant citrus-infesting aphids A. spiraecola (formerly A. citricola) and Aphis (Toxoptera) aurantii in the region seem far less efficient under experimental conditions (Supplementary Table S3, [5,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51]). A. citricidus, the most efficient vector of CTV worldwide [5], apparently remains restricted to the island of Madeira and the coastal area of the northwest quadrant of the Iberian Peninsula of Spain and Portugal. Aphids transmit the virus in a semi-persistent mode. The efficiency of transmission also varies between CTV isolates; isolates ST and VT-1, both of which belong to the VT strain, differ considerably in their rates of transmission by A. gossypii [52,53].

The failure of CTV eradication efforts throughout most of the Mediterranean countries, mainly due to the complex patterns of citriculture, in terms of ownership, maintenance and variety composition, has prompted the adaption of novel horticultural practices based on CTV-tolerant rootstocks, such as Troyer and Carrizo citrange, and this is in progress in many countries. Considerable difficulties were noticed, however, due to the underestimation of the new disease, and agronomic problems linked to the soil and water type and/or the fact that some budwood was infected by viroids.

This effective replacement strategy assumes that SP- and RB-inducing isolates and/or their efficient vectors are still absent from the Mediterranean area. Indeed a regional surveillance program should be adopted by the national phytosanitary services to prevent their introduction and spread.

The case of tristeza stem pitting. A CTV disease named stem pitting (SP) has been reported in many countries in the southern hemisphere, where it is responsible for considerable damage. The affected trees of sweet orange, grapefruit and lime species show stunting, low yield and poor fruit quality, regardless of the rootstock used (Figure 3). SP is induced by most CTV isolates when inoculated on Mexican lime and C. macrophylla, indicator plants or rootstocks. Grapefruit, sweet orange and other citrus species may also show this symptom in the field when infected by VT stem pitting isolates. Countries in which the SP isolates are prevalent, causing tree decline and poor performance in crops—as in the case of grapefruits in South Africa and the Pera orange variety in Brazil—have adopted mild isolate cross protection as a practical means of preventing the damaging effects of locally spreading native severe stem-pitting CTV isolates [54,55].

Figure 3.

Symptoms of tristeza stem pitting caused by SP isolates of CTV on the trunk (a), stem (b) and branch (c) of grapefruit. Similar effects may occur on some sweet orange varieties and on indicator plants, or on alemow used as rootstock (d).

However, field symptoms of stempitting disease in grapefruit trees have been only occasionally detected in the Eu-Med region, although they have been detected in Mexican lime and alemow seedlings and grapefruit and acidless pummelo plants in greenhouse tests [34,37].

Biological indexing on sweet orange and grapefruit in greenhouse allows to discriminate SP isolates and to evaluate their severity [32].

Resistance-breaking (RB) CTV isolates. Old surveys led researchers to assume that P. trifoliata plants were tolerant or resistant to most of the CTV isolates and strains, due to specific loci that are able to prevent the early steps of the infection process and to modify its expression. A similar mechanism has been reported for Swinglaea glutinosa and Severinia buxifolia. In recent years, certain CTV genotypes, known as resistance-breaking (RB) genotypes, were phylogenetically analyzed and found to belong to at least two subgroups, which shared 90.3% genomic nucleotide sequence identity with the T36 clade [41].

After a T36 isolate of CTV was able to infect and replicate in P. trifoliata protoplasts [56] and the T68 and VT genotypes were detected in the root of P. trifoliata cv. ‘Rubidoux’, the low detection rate for the CTV RB isolates was related to a low titer of the accumulated virus or an uneven distribution in shoots [41]. This limitation was apparently surmounted when a VT strain was found to coinfect a tree, generating a positive interaction for the infection [57,58].

After the discovery of a CTV isolate capable of breaking CTV resistance in trifoliate oranges and replicating in roots, bark and foliage, the spread of these isolates was investigated in many countries (Supplementary Table S2) outside the Mediterranean region [14], and they were recently found to have spread in China [59]. A few infected trees have been found in Morocco and rogued [60]. The productivity of infected trees is variable in relation to the scion–rootstock combination and the mixture of CTV isolates infecting the tree.

Different molecular methods for the detection of RB isolates are available. The first identification method using RT-PCR was described in 2013 by Roy et al. [40], who developed a genotype-specific assay that enabled them to overcome the difficulties of the MMM method to detect the presence of an unassigned genotype such as RB. However, in 2015, a new MMM marker specific for RB, targeting the ORF1a K17 region, was designed and used to study the diversity of the CTV strains present in New Zealand and the Pacific [57]. Cook et al. [61] proposed an RT-PCR protocol with three pairs of primers specifically designed to amplify RB group 1, RB group 2 and HA16-5, targeting a portion of the LProII domain of ORF1a. This protocol has been successfully used to detect multiple strains in two South African cross-protecting sources. A lab-on-chip miniaturized platform based on a sequential multiplex RT-PCR and microarray hybridization allowed researchers to simultaneously discriminate between the T36, T30, VT, RB, T68 and T3 strains in mixed infections [62].

Saponari et al. [63] describe a protocol developed in California, based on a preliminary assay related to the Mab MCA13 and T36NS probe, designed in the intergenic region between p25 and p27, followed by a bark inoculation on P. trifoliata and a test on Madam Vinous seedlings after a passage on trifoliate orange to check the infectivity, and a p65 sequence phylogenetic analysis.The full-length genome sequencing of these isolates confirmed the phylogenetic analysis. Two subclades were distinguished, with Californian isolates falling in both, and the New Zealand isolates placed together in group I, differently from the findings of Cook et al. [61].

Overall, although molecular methods help in a preliminary screening to identify potential SP or RB isolates, a combination of biological, molecular and, possibly, serological data are needed for a conclusive identification [14,32].

2.2. Citrus Tatter Leaf Virus, a Strain of Apple Stem Grooving Virus (Capillovirus, Betaflexiviridae)

Citrus tatter leaf virus (CTLV) is a strain of the Apple stem grooving virus (ASGV), a virus with a +ssRNA genome of 6496 nucleotides [64]. The virus is reported to be present throughout the world, with isolates infecting a variety of non-citrus hosts, particularly apples and pears. However, the disease caused by CTLV has not been reported on citrus plants in the Mediterranean region (Supplementary Figure S2) [65]. Complete genome sequences from different citrus species have been generated in Asia and USA (Table 2) [32,36,43,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86].

Table 2.

Relevant data of complete genome sequences of the main exotic and emergent citrus viruses relevant for the Mediterranean in addition to citrus tristeza virus.

Tatter leaf disease was first noted at Riverside, California, in 1962, on C. excelsa inoculated with a Meyer lemon introduced from China in 1908 based on leaf malformation. It was later found that trifoliate orange and its hybrids infected with similar budwood showed severe indentations, a brown line and a crease at the bud union, as well as stunting, initially considered to be caused by a separate disease agent named citrange stunt. Later, it was shown that both symptoms resulted from an identical virus named citrus tatter leaf virus [87].

Almost all citrus plants, regardless of species, cultivars and hybrids, are symptomless hosts if grown on their own roots or on tolerant rootstocks. Differently, trees grafted on P. trifoliata and its hybrids may show a bud–union crease about a year after grafting, with a marked yellow-to-brown line detectable after bark removal. Leaves of Rusk and Troyer citrange, Swingle citrumelo and other trifoliate hybrids show persistent clear spots, associated with the tattering of the leaf blade (Figure 4). Stems may be deformed and show a zigzag growth pattern, associated with chlorotic and pitted areas. C. excelsa is also sensitive to tattering and wood pitting.

Figure 4.

Mottling and tattered margins of a young leaf of Troyer citrange seedling inoculated with citrus tatter leaf virus (a), strong blotching of a mature leaf of the same seedling (b) and browning and bud-union collapse of a tree grafted on trifoliate orange (c).

The disease was subsequently found to be widespread in China and endemic in most Asian countries (Supplementary Figure S2) [88,89,90]. It also has been reported in all the citrus-producing states in the US, Australia [91] and South Africa [92]. CTLV led to severe decline which forced growers in China to substitute trifoliate orange rootstocks with the CTV-decline-tolerant Gou Tou orange, which later turned out to be susceptible to CTV stem pitting.

The virus, previously unnoticed in the Mediterranean region, was reported recently to be present in some lemon trees introduced to Cyprus from abroad [93]. Sporadic infections of the virus were found in introduced budwood in Sicily [32], and it was probably also present in some old introductions of Meyer lemon or Satsuma mandarin. The virus is included in the list of quarantine pests for many citrus-growing countries and is on the EPPO A1 list [11] (Table 1).

A long list of herbaceous plants is infected by the virus when inoculated mechanically. Among them are vegetables (such as pea, soybean, tomato and others) and weeds (such as Amaranthus tricolor, Chenopodium spp., Gomphrena globosa, Nicotiana spp. and others). Knife slashes and leaf abrasions allow infections from N. clevelandii to affect citrons and pass from citron to citron. Seed transmission has been observed in C. quinoa, cowpea and soybean, and there is some evidence of its possible seed transmission in Eureka lemon [94].

Given that all citrus species are potential hosts in the EPPO region, considering the number of introductions made before the international quarantine regulations, and the large recent use of trifoliate-hybrid rootstocks in the citrus-growing Mediterranean region, CTLV has the potential to pose a significant threat to the citrus industry [64,91].

Detection, initially performed using Troyer and Rusk citrange plants as indicator plants, has been replaced by ELISA [95], RT-PCR [91] and immunocapture–RT-PCR [96]. More recently developed RT-qPCR protocols using TaqMan® probes for CTLV detection [90,97] showed higher sensitivity than the SYBR Green assay [98]. Multiplex PCR methods, developed to detect CTLV, together with other viruses [99] and viroids [100], show a lack of sensitivity and high-throughput processing capability [90].

Using HTS technologies, the virus was detected, along with CTV, Citrus yellow vein clearing virus and citrus viroids, in samples screened for multiple infections [32,101].

2.3. Satsuma Dwarf Virus (Sadwavirus, Secoviridae) and Related Diseases

Satsuma dwarf virus (SDV) is a small isometric virus (26 nm in diameter) of two + ssRNAs (6790 and 5345 nt, genomic molecules). Complete genome sequences of three Satsuma dwarf virus isolates have been recently obtained by HTS [66] (Table 2). The virus is graft and mechanically transmitted, without a reported vector present in the EPPO region countries (Supplementary Figure S3). It is included in the EPPO A2 list and is thus recommended for regulation as a quarantine pest [11] (Table 1).

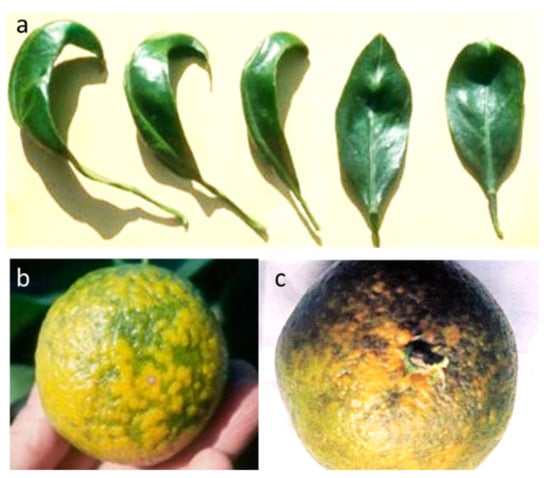

Satsuma dwarf, first reported in Japan, affects many citrus species and cultivars, and ornamental Rutaceae [102]. Today, several diseases previously considered different in certain details are thought to be phenotypically and genetically close, namely, Citrus mosaic virus (CiMV), navel orange infectious mottling virus (NIMV), Natsudaidai dwarf virus (NDV) and Hyuganatsu virus (HV). All these viruses are associated with spring flush malformation on Satsuma mandarins. Affected leaves are narrow-, boat- or spoon- shaped, with the plants showing enations, multiple flushing, fewer leaves, and small fruits with thicker peels (Figure 5). The trees are stunted and produce poorly. In addition, NDV is associated with the vein clearing, mottling and curling of the Natsudaidai variety, whereas NIMV mainly affects sweet orange trees. One variant, known as citrus mosaic virus, found exclusively in Japan, induces leaf mosaic symptoms.

Figure 5.

Boat-shaped leaves of Satsuma mandarin affected by satsuma dwarf virus (a), and the ring-shaped mosaic of the rind of the fruits before (b) and after the colored stage (c). Panels (a,b) retrieved from the Ecoport slideshow (http://citrus.ecoport.org/ accessed on 31 July 2021).

Biological assays for citrus indicators are symptomatic only after eliminating the coinfected CTV isolate using the trifoliate orange as a filter [103]. Herbaceous hosts allow rapid diagnosis [104]. ELISA is useful for detecting SDV but unable to discriminate between the citrus mosaic virus, navel orange infectious mottling virus and Natsudaidai dwarf virus, which differ in amino acid composition from SDV by 25% [105].

A broad-spectrum one-step RT-PCR process has been developed to detect the virus variants after the sequencing of the RNA 2 genome component of SDV and related viruses [105]. A multiplex RT-PCR allows for the simultaneous detection of SDV and CiMV targeting the PP2 gene region of Korean isolates, in combination with CTV and CTLV [106].

Recently, a QuantiGene Plex-Luminex assay has been developed for the detection of different citrus viruses and viroids, including SDV, applying a hybridization assay on magnetic beads, using probes that are sufficiently sensitive to allow signal detection in the absence of prior reverse transcription or DNA amplification [107].

2.4. Citrus Leprosis Viruses (Cilevirus, Kitaviridae, Dichorhavirus and Rhabdoviridae)

Citrus leprosis (CL) is an atypical and complex viral disease, caused by viruses belonging to two distinct genera, Cilevirus and Dichorhavirus, which affect the cytoplasm (CL-C) and the nucleus (CL-N), respectively [47]. Bacilliform cilevirus species (citrus leprosis virus C (CiLV-C) and citrus leprosis virus C2 (CiLV-C2) primarily infect sweet orange, but also some mandarins and grapefruit. They have bipartite +ssRNA genomes (8729/4969 and 8717/4989 nt) encoding six ORFs. The virus infections are microscopically observable in the endoplasmic reticulum, where they form dense, vacuolated viroplasm-like structures.

The dichorhaviruses are Orchid fleck virus citrus strain (OFV-citrus) (previously, citrus leprosis virus nuclear type (CiLV-N), citrus leprosis virus N (CiLV-N) and citrus chlorotic spot virus C (CiCSV) (see Zhou et al. [6] for comprehensive reference lists).

The disease is endemic to the Western Hemisphere, widely infecting most commercial citrus species throughout South America (Table 2), under a variety of names, such as nail head rust, nail head spot, scaly bark and “lepra explosiva” [108]. It is categorized as a quarantine pest in most countries [11] and is included in EPPO list 1 (Table 1).

Citrus leprosis viruses do not move systemically within the host, except for short distances along the mid-vein or secondary veinlets. They cause similar symptoms in the citrus hosts and are transmitted in a persistent manner [109] by mites of the genus Brevipalpus (Supplementary Table S3), which occur on citrus plants worldwide but rarely cause significant damage.

The symptoms on leaves and fruits are brown circular lesions (10–30 mm), centered at the point where the mite feeds, and surrounded by a chlorotic halo with 1–3 concentric rings. They may coalesce and crack. Fruits show yellow spots, which later become brown and depressed, change color prematurely and drop (Figure 6). Both leaf and fruit symptoms may be confused with measles and citrus canker. Young stems show small, chlorotic and shallow lesions that become darker and turn corky with age, and progress to bark scaling, without the wood staining usually associated with psorosis disease. In the infected areas, such as Brazil, the disease causes serious damage via leaf dropping and is regularly controlled by several annual applications of insecticides aimed to control mite populations and disease transmission.

Figure 6.

Brown circular lesions surrounded by a chlorotic halo on green fruits of sweet orange trees infected by Satsuma dwarf virus (a), a dark depressed lesion on a ripe fruit (b), dark and corky bark lesions on the stems (c,e), and a circular concentric lesion on a leaf (d) (Courtesy of Fundecitrus).

The detection was long based on transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis. Distinct diagnostic protocols are now available, specifically designed for each viral causal agent. CiLV-C, the most widespread, is reliably detected using ELISA [110,111] and RT-PCR [112]. Recently, highly specific antibodies for TAS-ELISA and IC-RT-PCR have been produced using the recombinant coat protein of the virus [113]. A one-step quantitative qRT-PCR, 1000 times more sensitive, is helpful in the earliest stages of the CiLV-C disease [114]. Viruliferous vectors have been detected using RT-PCR [112,115] in all the active stages of B. phoenicis, starting from at least 10 viruliferous individuals [48]. Specific TEM and RT-PCR protocols have been developed to detect CiLV-C2 [67]. RT-PCR protocols, targeting the N gene of the dichorhavirus associated with the disease, allows one to detect the citrus strain of OFV [116] and CiLV-N [117].

The application of HTS has increased the level of knowledge on genomic sequences and on the different viruses associated with the symptoms of leprosis, leading to new methodologies and descriptions of new species and genera (Table 2).

2.5. Citrus Yellow Mosaic Virus (Badnavirus, Caulimoviridae)

Citrus yellow mosaic virus (CYMV) is a non-enveloped bacilliform virus (150 × 30 nm in size) with a dsDNA genome (7559 bp in length) [70,118] (Table 2). Complete sequences from different hosts (sweet orange, rangpur lime, acid lime and pummelo) showed that they exhibit a more than 90% identity to each other [71,119]. Genetically, this citrus virus is closely related to cacao swollen shoot virus [70].

The disease was first reported in India in 1975 on sweet orange, lemon, mandarin, grapefruit and pummelo plants [118,120]. Mosaic symptoms affect the leaves, branches, fruits, etc., producing irregular yellow or bright green patches against a dark green background. The symptoms include bright yellow mottling or vein flecking on mature leaves and, occasionally, on fruits. If the trees are considerably affected, significantly low production and poor-quality fruits are observed, and the premature death of the plants sometimes occurs [118,121].

CYMV is transmitted by graft, infecting at least 13 citrus cultivars and their related plants [117]. It is also mechanically transmitted to citrus [118,121] and several non-citrus species. Indeed, the major mode of the dissemination of the virus is believed to be through infected rootstocks of rangpur lime during grafting [122]. The degree of spread by citrus mealybug (Planococcus citri) remains undetermined and would likely be localized because of the vector’s sedentary nature [51,123]. CYMV is categorized as a quarantine pest [11] and is included in EPPO list 1 (Supplementary Figure S5, Table 1).

Molecular methods based on RT-PCR, dot-blot hybridization and isothermal amplification are preferred for the serodiagnosis of this virus due to the relatively weak immune signals associated with CYMV infection. However, an immunodiagnostic method using in vitro-expressed recombinant virion-associated proteins was recently developed and found to be useful for large-scale detection [124]. Different RT-PCR protocols for the detection of the virus in plant samples, in combination with other pathogens, have been reported [122,125]. Dot-blot hybridization is useful as a preliminary detection test of suspected samples [126]. A real-time PCR protocol with SYBR Green was proposed by Johnson et al. [127], improving the sensitivity of detection. Recombinase polymerase amplification (RPA) allows researchers to detect plant viruses directly from the crude sap and in combination with immunocapture (IC-RPA), with extensive potential applications for the screening of a large number of samples [128].

3. Citrus Viruses Not Yet Recommended for Regulation as Quarantine Pests

3.1. Citrus Yellow Vein Clearing Virus (Mandarivirus, Alphaflexiviridae)

Citrus yellow vein clearing virus (CYVCV) has filamentous virions with a genome organization and size similar to those of flexiviruses [72,129]. The single-strand positive-sense RNA genome consists of 7529 nucleotides (nt) with a 5′ untranslated region (UTR) of 78 nt and a 3′ UTR of 36 nt, excluding the 3′ poly-A tail, and six open reading frames (ORFs) [72]. The isolates from Turkey, India, China and Pakistan showed closely similar genomic organization, suggesting considerable genetic stability [72,73,74,75,76,77,78]. Phylogenetic analyses based on comparisons of the amino acid sequences of ORF1 (RdRp) and ORF5 (CP) showed that CYVCV resides on the same branch as Indian citrus ringspot virus (ICRSV), in a clade clearly distinct from members of the other genera. It is closely similar to ICRSV, in particle size and genome organization, and shares a 74% sequence identity. However, it is serologically distinct and different in terms of the symptoms induced [72].

Following the sequencing of the first genome [72], a large number of isolates were deciphered by means of HTS from different countries, especially from infected lemon trees (Table 2).

The disease causing yellow vein clearing was first noticed on lemons and sour oranges in Pakistan [130] and was later observed to spread in many Asian countries, such as in India [131,132] in China on lemons [133] and in Iran on sour oranges, Eureka lemons and Persian limes [134]. Regrettably, it has reached Turkey in the past two decades, severely affecting lemon groves [45,135]. Occasionally, infected lemon trees have also been found in Cyprus [94], introduced from abroad, and in some citrus budwood sources introduced for research purposes [32].

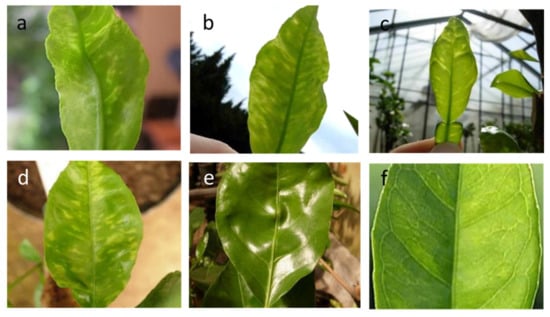

Under field conditions, the symptoms of the yellow vein clearing of the lateral veins and the yellow flecks are best seen with transmitted light, on the spring and autumn flushes of lemon and sour orange leaves (Figure 7). The environmental conditions affect their visibility [136]. Tissues along the adaxial veinlets may become water-soaked and then turn brown. Sour orange shows slight mottling, whereas sweet orange may show only a slight vein clearing (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Citrus yellow vein clearing virus induces vein clearing, yellow flecks, and distortion of young leaves of lemon (a,b) and sour orange (c,d), which may be persistent on mature leaves (e) and very mild on some sweet orange varieties (f).

Some diseased leaves are also crinkled and warped, with wavy edges that persist, similar to those induced by other viruses such as citrus infectious variegation (CVV) and citrus crinkly leaf virus (CCLV). Small chlorotic rings, sometimes associated with yellow vein clearing, are reminiscent of ringspot disease. The fruits of infected satsuma mandarins may show groove-like depressions, beginning at the upper portion of the fruit [137]. The wide spread of the virus in certain areas is associated with substantial economic losses, mainly in terms of lemon production [133].

CYVCV is transmitted by grafting and is mechanically and experimentally transmitted by two vectors, the spirea aphid (A. spiraecola), and probably, the cowpea aphid (A. craccivora), to beans and lemons [45], whereas A. gossypii, A. spiraecola and citrus whitefly (Dialeurodes citri) can successfully transmit CYVCV between citrus species [46,49] (Supplementary Table S3). Furthermore, CYVCV is transmissible by contaminated tools on sour oranges (16.5%) and rough lemons (20%) [46]. Conclusive evidence of seed transmission is still lacking [138]. On herbaceous plants, it can cause chlorosis, leaf mosaic symptoms and general necrosis, and some experimentally inoculated weed species remain symptomless [45].

The natural spread of this disease by whiteflies [49] and aphids [46] has turned the disease into a worldwide, emerging problem. The control measures adopted in China include rogueing of symptomatic plants and use of virus-free propagation materials [139], but Mediterranean countries have still not adopted any precautionary measure of surveillance.

Indexing by means of the graft inoculation of bark patches on sour orange or lemon seedlings or budlings produces the best results on continuously flushing indicator plants. The virus particles are detected by means of TEM [140] and immunosorbent TEM [128]. Different standardized serological methods are available for the rapid identification of infections [141,142,143].

Two main RT-PCR protocols, targeting the 5′ end of the genome [72] or the viral coat protein, have been developed. Reverse transcription- loop-mediated isothermal amplification (RT-LAMP) [144] and nested-RT-PCR [145] are rapid, simple and highly specific. Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) also allows detection in asymptomatic plants [146]. The droplet digital PCR (RT-ddPCR) method has been shown to allow the detection and quantification of low copy mixed infections of CYVCV and CTV, CTLV and viroids, and within infected vectors [139].

Recently, HTS sequencing allowed the identification of a novel virus with elongated flexuous virions resembling those of Mandarivirus, tentatively named citrus yellow mottle-associated virus (CiYMaV). The use of the antibody MAB 26A1 in serological testing allows the new virus to be distinguished from CYVCV [147].

3.2. Indian Citrus Ringspot Virus (Mandarivirus, Alphaflexiviridae)

Indian citrus ringspot virus (ICRSV) has a 7.5-kb ssRNA genome with six open reading frames (ORFs), along with 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions (Table 2). Flexuous rod-shaped virions are 650 nm in length and 13 nm in width [148]. The disease was brought into the citrus experiment station of Abohar in 1945 and eventually spread throughout the northwest of India [148], to which it is currently limited [149].

The disease affects commercial citrus cultivars of sweet orange, the popular Kinnow mandarins, acid limes, pummelos and grapefruit [149,150]. Infected trees exhibit conspicuous chlorotic rings, mottling and irregular chlorotic patterns, which are mostly evident on mature leaves, as occurs in the case of CYVCV infections, and sometimes on fruits. Of important diagnostic value is the appearance of irregular chlorotic rings on the leaves of the lower canopy [80]. Infected trees deteriorate annually, which affects their performance regarding fruits.

The disease is graft-transmissible from citrus and dodder to citrus. Although it has been detected in pollen from infected trees [149], there is no evidence for transmission from seeds or soil or by aphids or nematodes. Experimental mechanical transmission to cultivars of French bean, soybean, C. quinoa and C. amaranticolor resulted in local lesions and systemic infections.

Several classic methods have been used to detect ICRSV: biological indexing, ISEM, ELISA, RT-PCR and a multiplex RT-PCR technique [80,99]. The sensitive and rapid detection of ICRSV was performed using the one-step RT-LAMP with four different primers, targeting the coat protein gene of the virus. The RT-LAMP assay was found to be rapid, simple, cost effective and about one hundred times more sensitive than RT-PCR [151].

3.3. Citrus Chlorotic Dwarf-Associated Virus (Geminiviridae)

Citrus chlorotic dwarf-associated virus (CCDaV) is a novel DNA virus with a single-stranded circular genome 3640 nt in size, recently discovered by deep sequencing [82]. Further isolates were sequenced in Turkey, China and Thailand (Table 2). The disease was first observed and recognized in the mid-1980s in Turkey [152] and is particularly detrimental to lemon, grapefruit, common mandarin, clementine and others. The leaf symptoms include crinkling, curling, inverted cupping, malformation, chlorotic patterns and variegation (Figure 8), as well as reduced size, similar to those of diseases affecting leaves, such as citrus variegation, Satsuma dwarf, citrus leaf rugose and citrus yellow vein clearing. Young trees display bushy vegetation and a stunted appearance, due to the shortened internodes. It is naturally transmitted by the bayberry whitefly (Parabemisia myricae) and, probably, cowpea aphids (A. craccivora) (Supplementary Table S3). In China, where the disease was observed in 2008 on Eureka lemons in the Yunnan province [84], the infected trees showed mosaic symptoms, distortion and shrinkage on tender shoots and young leaves, as well as short internodes and narrow leaf blades. Infected trees are severely stunted, and the fruits are smaller in size. To date, only sweet orange varieties have shown tolerance to this disease.

Figure 8.

Indented margins of Interdonato lemon leaves (a), crinkling and chlorosis (b) in the Mersin region of Turkey (retrieved from the Ecoport slideshow, http://citrus.ecoport.org/, accessed on 31 July 2021).

Citrus chlorotic dwarf-associated virus (CCDaV) is a novel DNA virus with a single-stranded circular genome 3640 nt in size, recently discovered by deep sequencing [82]. Further isolates were sequenced in Turkey, China and Thailand (Table 2). The disease was first observed and recognized in the mid-1980s in Turkey [152] and is particularly detrimental to lemon, grapefruit, common mandarin, clementine and others. The leaf symptoms include crinkling, curling, inverted cupping, malformation, chlorotic patterns and variegation (Figure 8), as well as reduced size, similar to those of diseases affecting leaves, such as citrus variegation, Satsuma dwarf, citrus leaf rugose and citrus yellow vein clearing. Young trees display bushy vegetation and a stunted appearance, due to the shortened internodes. It is naturally transmitted by the bayberry whitefly (Parabemisia myricae) and, probably, cowpea aphids (A. craccivora) (Supplementary Table S3). In China, where the disease was observed in 2008 on Eureka lemons in the Yunnan province [84], the infected trees showed mosaic symptoms, distortion and shrinkage on tender shoots and young leaves, as well as short internodes and narrow leaf blades. Infected trees are severely stunted, and the fruits are smaller in size. To date, only sweet orange varieties have shown tolerance to this disease.

At present, the virus remains restricted to parts of Turkey and some Asian citrus countries, but the bayberry whitefly is known to be present in many countries (Supplementary Table S3; Figure 1). Therefore, it will be important to closely follow the possible spread of the disease to nearby geographical areas.

Indexing on sour orange, rough lemon and alemow plants under warm conditions can be used to identify the disease. Both conventional and quantitative PCR (qPCR) have been successful in detecting CCDaV in symptomatic plants from Turkey [82]. A new detection protocol using RT-PCR has been used to characterize the population structure of CCDaV isolates from different citrus species in Turkey, also leading to the full genome sequencing of six new isolates [83].

3.4. Citrus Sudden Death-Associated Virus (Marafivirus, Tymoviridae)

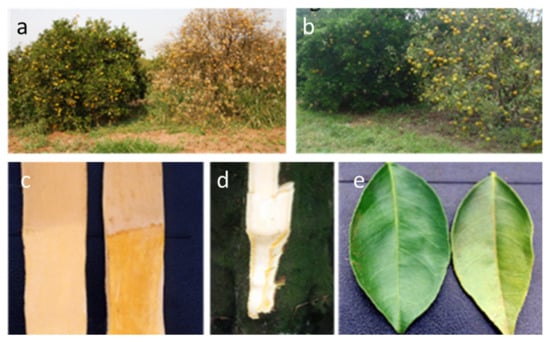

Citrus sudden death (CSD) disease was detected in 1999 in Brazil in sweet orange groves grafted on Rangpur lime, and it spread quickly, causing the alarming death of about four million trees. The symptoms of CSD are tree decline and rapid death, as for other citrus disease agents, such as Phytophthora spp. and tristeza, on trees on their own roots and sour orange, respectively. Infected trees show a discoloration of the tree canopy caused by a pale green coloration of the leaves, overall defoliation, death of the fibrous roots, decline and tree death (Figure 9). Symptoms are less frequently detected in trees grafted on C. volkameriana, C. jambhiri and C. pennivisiculata (see Matsumura et al. [153] for comprehensive reference list). A characteristic yellow stain in the phloem in the lower portion of the rootstock bark was evident on trees grafted on Rangpur lime and volkameriana rootstocks. New plantings in the infected area used alternative rootstocks such as Swingle citrumelo, Cleopatra mandarin, Sunki mandarin and trifoliate orange, which are tolerant to the disease but less adapted to drought conditions.

Figure 9.

Defoliation, decline and death of trees by citrus sudden death (a,b), yellow stain in the phloem of the Rangpur lime rootstock (c,d), and discoloration and browning of leaves (e). (Courtesy of Fundecitrus).

In the initial search for the causal agent, the apparent similarities between CSD- and CTV-induced quick decline led to the hypothesis that a new variant of CTV was involved in the disease. This hypothesis was disputed (Bar-Joseph, 2004, personal information), and the shotgun sequencing of CSD-infected tissue and further molecular characterizations allowed the association and characterization of a Marafivirus with CSD infections [43]. The CSDaV virions are isometric particles ≈30 nm in diameter, composed of a monopartite, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA genome of approximately 6.8 kb, encompassing two ORFs. A recent HTS analysis of the transcriptomes and sRNAs demonstrated a putative association of the disease both with a specific CSDaV genotype and with citrus endogenous pararetrovirus (CitPRV, family Retroviridae) (Table 2) [36,153].

The recent wide use of volkameriana lemon and C. macrophylla rootstocks in certain Mediterranean areas leads us to consider CSD a potential threat for the region, although the variation in climatic factors and in vector populations could delay or prevent the movement of CSD to new citrus areas.

The symptoms of the disease are difficult to reproduce on indicator plants, but different protocols have been described for detecting CSDaV by means of RT-PCR, on both symptomatic and asymptomatic trees and in aphids feeding on infected trees [36,43,154]. Moreover, the target regions show different variability, probably related to biological functions [153].

4. Control Measures

4.1. Surveillance Is the Priority

The Mediterranean is one of the largest citrus producing regions in the world, producing more than 21 million metric tons (21% of the global market) (Supplementary Table S1). Each country in the region exhibits its own peculiarities regarding citrus variety composition and phytosanitary status. Nevertheless, all of them share some basic features, such as in climatic conditions, the historical evolution of the citrus cultivation, rootstocks, pests and diseases, and are exposed to similar risks from climatic change and the introduction of pathogens and/or their vectors.

In recent years, the pressure resulting from both abiotic and biotic stressors has increased. Viruses and relative vectors are among the most endangering and risky effectors. No less important are other quarantine diseases and pests not covered by the present review that threaten Mediterranean citrus industries: Huanglongbing, citrus variegated chlorosis and citrus canker, as well as Diaphorina citri and A. citricidus. Climate changes, globalization and the migration of people, especially seasonal workers, are some of the most endangering epidemiological factors, which must be responsibly managed in order to prevent the unintentional spread of disease. To overcome the apparent discontinuous and non-homogeneous phytosanitary status at the regional level, mostly related to interception rather than surveys, an effort should be made to conduct valuable surveys aimed at promoting the adoption and sharing of better control measures. These should (i) focus on the early detection of new incursions (emerging/exotic pests) in the area/region of interest or (ii) be used to demonstrate freedom from a specific pest in the area/region of interest [7]. Furthermore, they should be focused on describing the prevalence or distribution of that specific pest, identifying cases that require the imposition of urgent control measures to contain the spread or establishment of the pest in question. These approaches must also consider the relevance of statistical methods for estimating the sample size, the global (and group) sensitivity and the probability of freedom from the disease. The planning of a statistically sound and risk-based pest survey approach to surveil and identify CTV SP and RB isolates exotic to the Mediterranean region (if any) that could have severe impacts should be prioritized [10].

4.2. Towards Better Detection Tools, for Fast and Large Surveys

The early-stage detection and diagnosis of viral and viroid diseases are the key to effective surveillance surveys and the prevention of the spread of exotic pathogens. They must be efficiently organized in order to allow proper control measures, based on the potential invader pathogenicity and epidemiological characteristics. This should become an utmost priority in the case of exotic pathogens vectored by insects or mechanically transmitted to different hosts—conditions that could generate significant genetic changes and potential new pathogens [155].

In the last few decades, the long time required for the detection of symptoms and the high cost of bioassays on indicator plants in controlled screenhouses led many laboratories to neglect biological testing in favor of immunological and molecular assays, encouraged by the continuous improvement of technologies in terms of sensitivity, specificity, reliability, simplicity and cost effectiveness, as well the ability to manage a high number of samples. ELISA has been and is still the most common and suitable tool for large surveys applied in quarantine and certification programs [156].

The introduction of nucleic-acid-based techniques and, especially, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis allowed researchers to extend fast and precise detection methods to all the viruses for which antibodies are not available, and to discriminate between strains and genetic variants of CTV [18,157] and others (e.g., leprosis). Multiplex PCR technologies allow for the simultaneous detection of mixed infections of different viruses or viroids in a single assay [106,122]. Most viruses exotic to the Mediterranean region can now be detected using real-time PCR, allowing to discriminate between genetic variants and to quantify the virus titer without the need for post-PCR electrophoresis. A new frontier for diagnosis in large surveys is represented by LAMP and RPA [158], since these are carried out at a constant temperature and do not require either thermal cycler equipment or skilled personnel, while maintaining sensitivity, specificity and fast detection. The use of such techniques has been effective for the early detection of ICRSV in the large-scale indexing of field samples in remote areas as well [151], along with other citrus pathogens as CYMV [127], and CYVCV [143].

The advent of HTS technologies [159,160] has shown the potential advantage of providing a complete view of the phytosanitary status of plants and let to discriminate between new genetic variants [155,161]. It allows researchers to reduce costs and time, especially if compared to bioassays, which can require 2–3 years to develop symptoms. Moreover, the HTS libraries can be saved and re-analyzed in case of the discovery of new viruses or changes in the bioinformatic pipeline. HTS has already generated important information in studies aimed at characterizing the genetic structure of citrus viruses, as shown in Table 2 and Supplementary Table S2. This method is expected to extend our knowledge and understanding of the genetic diversity of the genomic structures of previously established citrus pathogens and to reveal hidden citrus pathogens that presently remain unrecognized throughout the Mediterranean region and worldwide. Allowing timely investigations into their pathogenic nature and developing proper control measures are essential, since opportune prevention practices are the key to successful pathogen control.

In this respect, the validation of the regionally applied diagnostic techniques, in terms of their sensitivity, specificity and reproducibility, must be coordinated in order to overcome significant variability between different laboratories, pipelines, expertise, libraries and sequencing strategies [162]. It should also be emphasized that there is a continued need to correlate the disease to a particular virus [159], especially in relation to biological variations between pathogen strains and variants. As in the case of any new technology, standard operating procedures have to be validated in order to make the diagnosis robust in routine screening [101], and biological and molecular confirmation should be requested [32].

4.3. Production of Healthy Plants for Planting

As demonstrated by the experiences of several countries, the production of disease-tested propagative material is the most effective solution to preserve or rebuild certain agricultural sectors in the face of graft transmissible diseases. One of the earliest approaches to produce virus free citrus plants was adopted in California in the 1930s, when the first graft transmissible agent, citrus psorosis, was discovered at the Citrus Experiment Station in Riverside. In 1956, following the extension of citrus indexing to new disease agents and the shortening of the time needed to obtain results, the Psorosis-Free Program evolved into the California Variety Improvement Program (CVIP), now known as the Citrus Clonal Protection Program (CCPP). The support of the citrus industry was crucial in obtaining successful results [163]. The Citrus Variety Improvement Programme of Spain (CVIPS) was launched in 1975 based on the CCPP [164]. The development of shoot tip grafting and thermotherapy technologies has helped to clean the propagation material from almost any graft-transmissible pathogen. In most cases they have been adapted to develop economically affordable means to sell “clean” citrus plants for “local” needs. Technical guidelines for the production of pathogen-tested citrus trees and rootstocks [165] and nursery requirement schemes for the production of healthy plants [166] on a regional basis are available and would be more effective to preserve the citriculture at least on a regional basis.

Concerning the Mediterranean region, it should be considered that the real list of systemic pathogens occurring in the EPPO region is large and needs to be updated, that recent findings have classified some old diseases in different ways and that new detection technologies are available. Therefore, there is a need to share and decide on a regional basis upon a new list of pathogens and to adopt validated certification programs, associated with continuous surveillance. As has been done in California and Spain, a more stringent protocol should be adopted in the case of the foreign introduction of propagative material to promptly discard infected material or, when possible, to adopt technologies available for sanitation.

The most critical step would be to organize indexing and procedures for recovering pathogen-free plants from local varieties to serve as a nuclear stock. It would be safer if each new species or variety introduced in the program was first subjected to full testing for all known pathogens, using molecular technologies associated with HTS in order to obtain a short-term result [32,101]. Parallel testing on indicator plants should also be compulsory.

5. Concluding Remarks

In this review, we have summarized the current knowledge and understanding of the occurrence, geographical distribution, biological characteristics and molecular biological features of exotic and emergent citrus viruses relevant to the Mediterranean region. Emphasis was placed on recent advances in their detection, control and suppression, aimed at preventing or limiting the spread of disease through best practices. It is intended as a contribution towards the many interventions needed to significantly limit the spread of disease and to maximize the agricultural and economic health of regional citrus industries. The valuable efforts of the International Organization of Citrus Virologists (IOCV), funded in 1957 by J.M. Wallace, contributed to the spread of knowledge on the surveillance of viral and viroid diseases affecting citrus plants. Over the years, it encouraged a number of countries to establish functioning and successful certification programs, as reviewed elsewhere. The recent Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2019/2072 of 28 November 2019, establishing uniform conditions for the implementation of Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 as regards protective measures against pests of plants, indicates outstanding changes to EU legislation.

It is obvious that large investments are needed to empower the citriculture of the Mediterranean region and to assure its long future. Educational programs will be helpful to understand and share the awareness of the dangers and provide well-trained personnel in well-equipped laboratories, as well as help to develop efficient communication with nurserymen, growers and consumers. With the overall benefit being a sustainable production of fruits and a safer environment.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agriculture11090839/s1, Supplementary Table S1. Global citrus production (in metric tons) in the Mediterranean countries, adapted from the USDA report in January 2021 for 2020/21 (USDA, FAS 2021, accessed in July 2021). Supplementary Table S2. Full genomes sequences of CTV available in GenBank (as of July 2021). Supplementary Table S3. Mediterranean distribution of vectors of exotic and Citrus viruses relevant for the Mediterranean region, their categorization and mode of transmission. Supplementary Figure S1. Global distribution of Citrus tristeza virus (non-EU isolates) (extracted from EPPO Global Database, accessed July 2021). Supplementary Figure S2. Global distribution of Citrus tatter leaf virus (extracted from EPPO Global Database, accessed in July 2021). Supplementary Figure S3. Global distribution of Satsuma dwarf virus (extracted from EPPO Global Database, accessed in July 2021). Supplementary Figure S4. Global distribution of Citrus leprosis sensu lato (extracted from EPPO Global Database, accessed in July 2021). Supplementary Figure S5. Global distribution of Citrus yellow mosaic virus (extracted from EPPO Global Database, accessed in July 2021).

Author Contributions

Literature search from the bibliographic database, information on hosts distribution and categorization from EPPO Global Database, and writing—original draft preparation: G.L. and A.F.C.; writing—editing and final review: G.L., A.F.C. and M.B.-J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This review was conceptualized, developed and finalized as an early action of the project NOVARANCIA ”Technological innovations (genetic, phytosanitary and agronomic) for the valorisation and traceability of red orange of Sicily”, funded by Regione Siciliana, PSR Sicilia 2014–2020, action 16–Cooperation, sub-action 16.1.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors warmly acknowledge the kind contribution by Giuseppe Eros Massimino Cocuzza, entomologist at the Department of Agriculture, Food and Environment (D3A), University of Catania, to help understand the vectors of citrus viruses and preparation of the Supplementary Table S3.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bar-Joseph, M.; Batuman, O.; Roistacher, N. The history of citrus tristeza virus–Revisited. In Citrus Tristeza Virus Complex and Tristeza Diseases; Karasev, A.V., Hilf, M., Eds.; APS Press: Saint Paul, MN, USA, 2009; pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Joseph, M.; Catara, A. Endemic and emerging vector-borne Mediterranean citrus diseases and their epidemiological consequences. In Integrated Control of Citrus Pests in the Mediterranean Region; Vacante, V., Gerson, V., Eds.; Bentham Science Pubblishers Ltd.: Sharjah, UAE, 2010; pp. 137–155. [Google Scholar]

- Davino, S.; Willemsen, A.; Panno, S.; Davino, M.; Catara, A.; Elena, S.F.; Rubio, L. Emergence and phylodynamics of Citrus tristeza virus in Sicily, Italy. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e66700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichert, I. EPPO study mission to investigate virus diseases of citrus in the Mediterranean countries. In Report of the International Conference on Virus Diseases of Citrus (Acireale, Sicily, 15–17 September 1959); European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organisation: Paris, France, 1960; pp. 13–44. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, P.; Ambros, S.; Albiach-Martì, M.R.; Guerri, J.; Peña, L. Citrus tristeza virus: A pathogen that changed the course of the citrus industry. Mol. Plant Path. 2008, 9, 251–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; da Graça, J.V.; Freitas-Astúa, J.; Vidalakis, G.; Duran-Vila, N.; Lavagi, I. Citrus viruses and viroids. In The Genus Citrus, 2nd ed.; Talon, M., Caruso, M., Gmitter, F., Jr., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2020; pp. 391–410. [Google Scholar]

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). Plant Pest Surveillance: A Guide to Understand the Principal Requirements of Surveillance Programmes for National Plant Protection Organizations; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- ISPM 5. Glossary of Phytosanitary Terms; IPPC/FAO: Rome, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- ISPM 6. Surveillance; IPPC/FAO: Rome, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- EFSA (European Food Safety Authority); Schrader, G.; Camilleri, M.; Diakaki, M.; Vos., S. Pest survey card on non-European isolates of citrus tristeza virus. EFSA Support. Publ. 2019, 16, 1600E. [Google Scholar]

- EPPO. EPPO Global Database. 2021. Available online: https://gd.eppo.int/ (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- Kitajima, E.W.; Silva, D.M.; Oliveira, A.R.; Müller, G.W.; Costa, A.S. Thread-like particles associated with tristeza disease of citrus. Nature 1964, 201, 1011–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martelli, G.P.; Agranosky, A.A.; Bar Joseph, M.; Boscia, D.; Candresse, T.; Coutts, R.H.A.; Dolja, V.V.; Hu, J.S.; Jelkmann, W.; Karasev, A.V.; et al. Family Closteroviridae. In Virus Taxonomy: Ninth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses; King, A.M.Q., Adams, M.J., Carstens, E.B., Lefkowitz, E.J., Eds.; Elsevier-Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 987–1001. [Google Scholar]

- EFSA PLH Panel (EFSA Panel on Plant Health). Scientific opinion on the pest categorisation of Citrus tristeza virus (non-European isolates). EFSA J. 2017, 15, 5031. [Google Scholar]

- Harper, S.J. Citrus tristeza virus: Evolution of complex and varied genotypic groups. Front. Microbiol. 2013, 4, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yokomi, R.K.; Selvaraj, V.; Maheshwari, Y.; Saponari, M.; Giampetruzzi, A.; Chiumenti, M.; Hajeri, S. Identification and characterization of CTV RB strains Citrus tristeza virus isolates breaking resistance in trifoliate orange in California. Phytopathology 2017, 107, 901–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Targon, M.L.P.N.; Machado, M.A.; Muller, G.W.; Coletta Filho, H.D.; Manjunath, K.L.; Lee, R.F. Sequence of coat protein gene of the severe Citrus tristeza virus complex Capão Bonito. In Proceedings of the 14th Conference of International Organization of Citrus Virologists (IOCV), Campinas, Brazil, 13–18 September 1998; da Graca, J.V., Lee, R.F., Yokomi, R.K., Eds.; IOCV: Riverside, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 121–126. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, A.; Ananthakrishnan, G.; Hartung, J.S.; Brlansky, R.H. Development and application of a multiplex reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction assay for screening a global collection of Citrus tristeza virus isolates. Phytopathology 2010, 100, 1077–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bester, R.; Cook, G.; Maree, H.J. Citrus tristeza virus genotype detection using high-throughput sequencing. Viruses 2021, 13, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yokomi, R.; Selvaraj, V.; Maheshwari, Y.; Chiumenti, M.; Saponari, M.; Giampetruzzi, A.; Weng, Z.; Xiong, Z.; Hajeri, S. Molecular and biological characterization of a novel mild strain of citrus tristeza virus in California. Arch. Virol. 2018, 163, 1795–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasev, A.V.; Boyko, V.P.; Gowda, S.; Nikolaeva, O.V.; Hilf, M.E.; Koonin, E.V.; Niblett, C.L.; Cline, K.; Gumpf, D.J.; Lee, R.F.; et al. Complete sequence of Citrus tristeza virus RNA genome. Virology 1995, 208, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.Y.S.; Watanabe, S.; Yokomi, R.; Ng, J.C.K. Nucleotide heterogeneity at the terminal ends of the genomes of two California Citrus tristeza virus strains and their complete genome sequence analysis. Virol. J. 2018, 15, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappu, H.R.; Karasev, A.V.; Anderson, E.J.; Pappu, S.S.; Hilf, M.E.; Febres, V.J.; Eckloff, R.M.; McCaffery, M.; Boyko, V.; Gowda, S.; et al. Nucleotide sequence and organization of eight 3’ open reading frames of the citrus tristeza closterovirus genome. Virology 1994, 199, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scuderi, G.; Russo, M.; Davino, S.; Ferraro, R.; Catara, A.; Licciardello, G. Occurrence of the T36 Genotype of Citrus tristeza virus in Citrus Orchards in Sicily, Italy. Plant Dis. 2016, 100, 1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Z.; Barthelson, R.; Gowda, S.; Hilf, M.E.; Dawson, W.O.; Galbraith, D.W.; Xiong, Z. Persistent infection and promiscuous recombination of multiple genotypes of an RNA virus within a single host generate extensive diversity. PLoS ONE 2007, 2, e917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, A.; Brlansky, R.H. Genome analysis of an orange stem pitting Citrus tristeza virus isolate reveals a novel recombinant genotype. Virus Res. 2010, 151, 118–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, G.; Breytenbach, J.H.J.; Steyn, C.; de Bruyn, R.; van Vuuren, S.P.; Burger, J.T.; Maree, H.J. Grapefruit field trial evaluation of Citrus tristeza virus T68-strain sources. Plant Dis. 2021, 105, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harper, S.J.; Dawson, T.E.; Pearson, M.N. Complete genome sequences of two distinct and diverse Citrus tristeza virus isolates from New Zealand. Arch. Virol. 2009, 154, 1505–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zablocki, O.; Pietersen, G. Characterization of a novel citrus tristeza virus genotype within three cross-protecting source GFMS12 sub-isolates in South Africa by means of Illumina sequencing. Arch. Virol. 2014, 159, 2133–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licciardello, G.; Scuderi, G.; Ferraro, R.; Giampetruzzi, A.; Russo, M.; Lombardo, A.; Raspagliesi, D.; Bar-Joseph, M.; Catara, A. Deep sequencing and analysis of small RNAs in sweet orange grafted on sour orange infected with two Citrus tristeza virus isolates prevalent in Sicily. Arch. Virol. 2015, 160, 2583–2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawassi, M.; Mietkiewska, E.; Gofman, R.; Yang, G.; Bar-Joseph, M. Unusual sequence relationships between two isolates of Citrus tristeza virus. J. Gen. Virol. 1996, 77, 2359–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licciardello, G.; Ferraro, R.; Scuderi, G.; Russo, M.; Catara, A.F. A simulation of the use of high throughput sequencing as pre-screening assay to enhance the surveillance of citrus viruses and viroids in the EPPO region. Agriculture 2021, 11, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varveri, C.; Olmos, A.; Pina, J.A.; Marroquín, C.; Cambra, M. Biological and molecular characterization of a distinct Citrus tristeza virus isolate originating from a lemon tree in Greece. Plant Pathol. 2015, 64, 792–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Ruiz, S.; Moreno, P.; Guerri, J.; Ambrós, S. The complete nucleotide sequence of a severe stem pitting isolate of Citrus tristeza virus from Spain: Comparison with isolates from different origins. Arch. Virol. 2006, 151, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, K.K.; Tarafdar, A.; Sharma, S.K. Complete genome sequence of mandarin decline Citrus tristeza virus of the north-Eastern Himalayan hill region of India: Comparative analyses determine recombinant. Arch. Virol. 2012, 157, 579–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumura, E.E.; Coletta-Filho, H.D.; Nouri, S.; Falk, B.W.; Nerva, L.; Oliveira, T.S.; Dorta, S.O.; Machado, M.A. Deep sequencing analysis of RNAs from citrus plants grown in a citrus sudden death-affected area reveals diverse known and putative novel viruses. Viruses 2017, 9, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.N.; Mathews, D.M.; Dodds, J.A.; Mirkov, T.E. Molecular characterization of an isolate of citrus tristeza virus that causes severe symptoms in sweet orange. Virus Genes 1999, 19, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albiach-Marti, M.R.; Mawassi, M.; Gowda, S.; Satanarayana, T.; Hilf, M.E.; Shanker, S.; Almira, E.C.; Vives, M.C.; López, C.; Guerri, J.; et al. Sequences of Citrus tristeza virus separated in time and space are essentially identical. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 6856–6865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vives, M.C.; Rubio, L.L.; Pez, C.; Navas-Castillo, J.; Albiach-Mart, M.R.; Dawson, W.O.; Guerri, J.; Flores, R.; Moreno, P. The complete genome sequence of the major component of a mild citrus tristeza virus isolate. J. Gen. Virol. 1999, 80, 811–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Roy, A.; Choudhary, N.; Hartung, J.S.; Brlansky, R.H. The prevalence of the Citrus tristeza virus trifoliate resistance breaking genotype among Puerto Rican isolates. Plant Dis. 2013, 97, 1227–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harper, S.J.; Dawson, T.E.; Pearson, M.N. Isolates of Citrus tristeza virus that overcome Poncirus trifoliata resistance comprise a novel strain. Arch. Virol. 2010, 155, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melzer, M.J.; Borth, W.B.; Sether, D.M.; Ferreira, S.; Gonsalves, D.; Hu, J.S. Genetic diversity and evidence for recent modular recombination in Hawaiian Citrus tristeza virus. Virus Genes 2010, 40, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccheroni, W.; Alegria, M.C.; Greggio, C.C.; Piazza, J.P.; Kamla, R.F.; Zacharias, P.R.A.; Bar-Joseph, M.; Kitajima, E.W.; Assumpção, L.C.; Camarotte, G.; et al. Identification and genomic characterization of a new virus (Tymoviridae family) associated with citrus sudden death disease. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 3028–3037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afloukou, F.M.; Çalişkan, F.; Önelge, N. Aphis gossypii Glover is a vector of citrus yellow vein clearing virus. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 2021, 87, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onelge, N.; Satar, S.; Elibüyük, O.; Bozan, O.; Kamberoglu, M. Transmission studies on Citrus yellow vein clearing virus. In Proceedings of the 18th Conference International Organization of Citrus Virology, Campinas, Brazil, 7–12 November 2010; da Graca, J.V., Lee, R.F., Yokomi, R.K., Eds.; IOCV: Riverside, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.H.; Wang, Y.L.; Qin, W.; Cao, M.J.; Zhou, C.Y.; Yan, Z. Identification of Aphis spiraecola as a vector of Citrus yellow vein clearing virus. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2018, 152, 841–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastianel, M.; Novelli, V.M.; Kitajima, E.W.; Kubo, K.S.; Bassanezi, R.B.; Machado, M.A.; Freitas-Astua, J. Citrus Leprosis: Centennial of an unusual mite-virus pathosystem. Plant Dis. 2010, 94, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubo, K.S.; Novelli, V.M.; Bastianel, M.; Locali-Fabris, E.C.; Antonioli-Luizon, R.; Machado, M.A.; Freitas-Astua, J. Detection of Brevipalpus-transmitted viruses in their mite vectors by RT–PCR. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2011, 54, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.H.; Liu, C.H.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Y.L.; Zhou, C.Y.; Zhou, Y. Identification of Dialeurodes citri as a vector of citrus yellow vein clearing virus in China. Plant Dis. 2019, 103, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, S.; Çinar, A.; Kersting, U.; Garnsey, S.M. Citrus chlorotic dwarf: A new whitefly-transmitted virus-like disease of citrus in Turkey. Plant Dis. 1995, 79, 1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnsey, S.M.; Behe, C.G.; Lockhart, B.E.L. Transmission of citrus yellow mosaic badnavirus by the citrus mealybug. Phytopathology 1998, 9, S43. [Google Scholar]

- Raccah, B.; Loebenstein, G.; Bar-Joseph, M. Transmission of citrus tristeza virus by melon aphid. Phytopathology 1976, 66, 1102–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-Joseph, M.; Loebenstein, G. Effects of strain, source plant, and temperature on the transmissibility of citrus tristeza virus by the melon aphid. Phytopathology 1973, 63, 716–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.S.; Muller, G.W. Tristeza control by cross protection: A U.S.-Brasil cooperative success. Plant Dis. 1980, 64, 538–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, G.; van Vuuren, S.P.; Breytenbach, J.H.J.; Steyn, C.; Burger, J.T.; Maree, H.J. Characterization of Citrus tristeza virus single-variant sources in grapefruit in greenhouse and field trials. Plant Dis. 2016, 100, 2251–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albiach-Marti, M.R.; Grosser, J.W.; Gowda, S.; Mawassi, M.; Satyanarayana, T.; Garnsey, S.M.; Dawson, W.O. Citrus tristeza virus replicates and forms infections virions in protoplasts of resistant citrus relatives. Mol. Breed. 2004, 14, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, S.J.; Pearson, M.N. Citrus tristeza virus strains present in New Zealand and the South Pacific. J. Cit. Pathol. 2015, 2, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, K.; Yang, F.; Zhou, C. Distribution and population structure of Citrus tristeza virus in Poncirus trifoliata. Austral. Plant Pathol. 2017, 46, 351–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhou, T.; Cao, M.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Z. First report of citrus tristeza virus trifoliate resistance-breaking (RB) genotype in Citrus grandis in China. J. Plant Pathol. 2019, 101, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afechtal, M.; D’Onghia, A.M.; Cocuzza, G.E.M.; Djelouah, K. First report of the Citrus tristeza virus resistance-breaking strain in Morocco. J. Plant Path. 2018, 100, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, G.; van Vuuren, S.P.; Breytenbach, J.H.J.; Burger, J.T.; Maree, H.J. Expanded strain-specific RT-PCR assay for differential detection of currently known Citrus tristeza virus strains: A useful screening tool. J. Phytopathol. 2016, 164, 847–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scuderi, G.; Catara, A.F.; Licciardello, G. Genotyping citrus tristeza virus isolates by sequential multiplex RT-PCR and microarray hybridization in a lab-on-chip device. In Citrus Tristeza Virus: Methods in Molecular Biology; Catara, A., Bar-Joseph, M., Licciardello, G., Eds.; Humana: New York, NY, USA, 2019; Volume 2015, pp. 127–142. [Google Scholar]

- Saponari, M.; Giampetruzzi, A.; Selvaraj, V.; Maheshwari, Y.; Yokomi, R. Identification and characterization of resistance-breaking (RB) isolates of citrus tristeza virus. In Citrus Tristeza Virus: Methods in Molecular Biology; Catara, A., Bar-Joseph, M., Licciardello, G., Eds.; Humana: New York, NY, USA, 2019; Volume 2015, pp. 105–126. [Google Scholar]

- Tatineni, S.; Afunian, M.R.; Hilf, M.E.; Gowda, S.; Dawson, W.O.; Garnsey, S.M. Molecular characterization of Citrus tatter leaf virus historically associated with Meyer lemon trees: Complete genome sequence and development of biologically active in vitro transcripts. Phytopathology 2009, 99, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA PLH Panel (European Food Safety Authority). Scientific Opinion on the pest categorisation of Tatter leaf virus. EFSA J. 2017, 15, 5033. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, J.; Zhang, S.; Wu, J.; Yang, F.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, C.; Cao, M. Complete genome sequences and recombination analysis of three divergent Satsuma dwarf virus isolates. Trop. Plant Pathol. 2021, 46, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]