Cross-Cultural Validity and Reliability of the Questionnaire on Back-Health-Related Postural Habits During Daily Activities in the Polish Young Adolescent Population

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Ethical Statement

2.3. Instrument

2.4. Translation and Cross-Cultural Adaptation

2.5. Participants

2.6. Procedure

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Translation and Cross-Cultural Adaptation

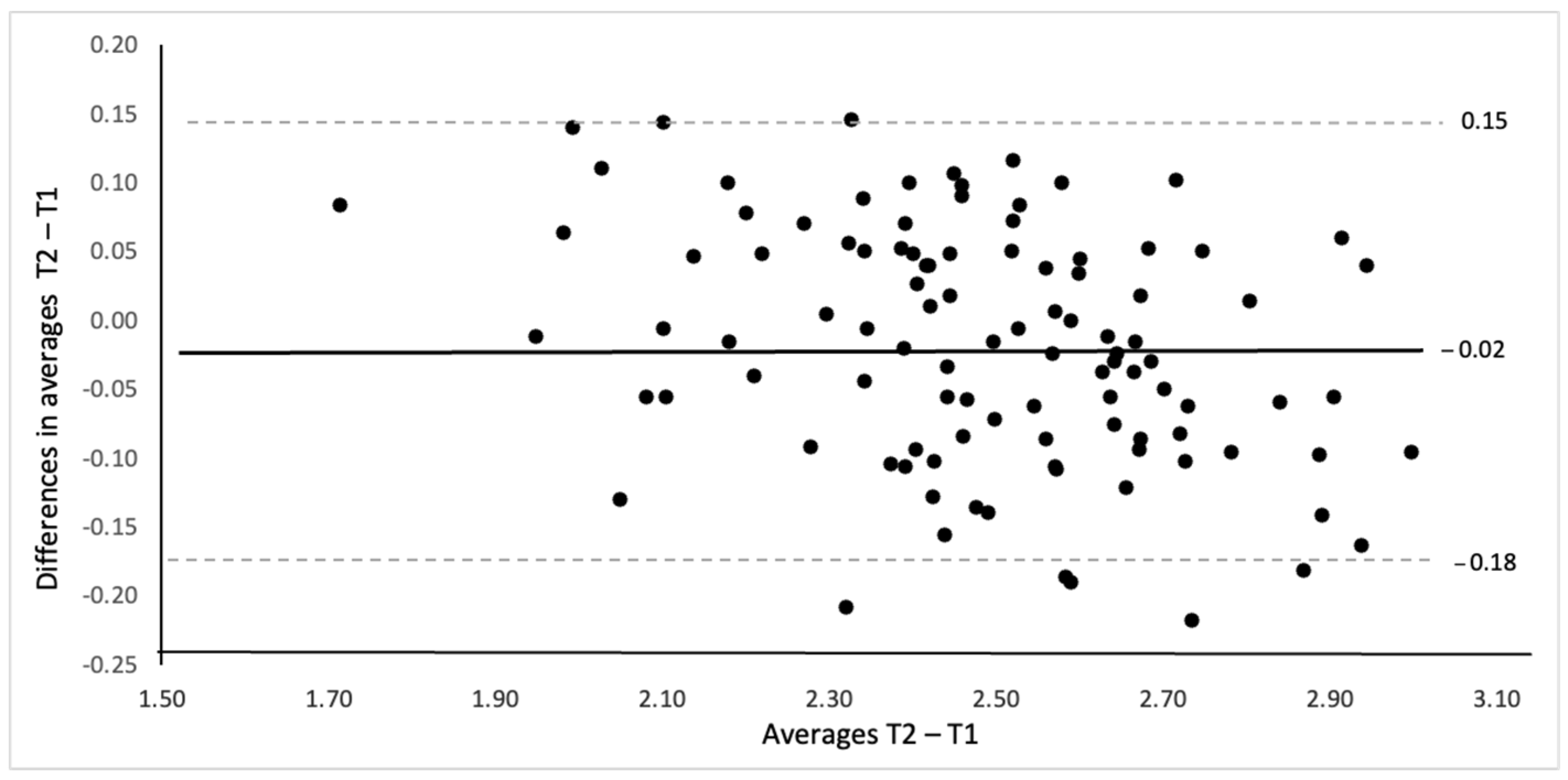

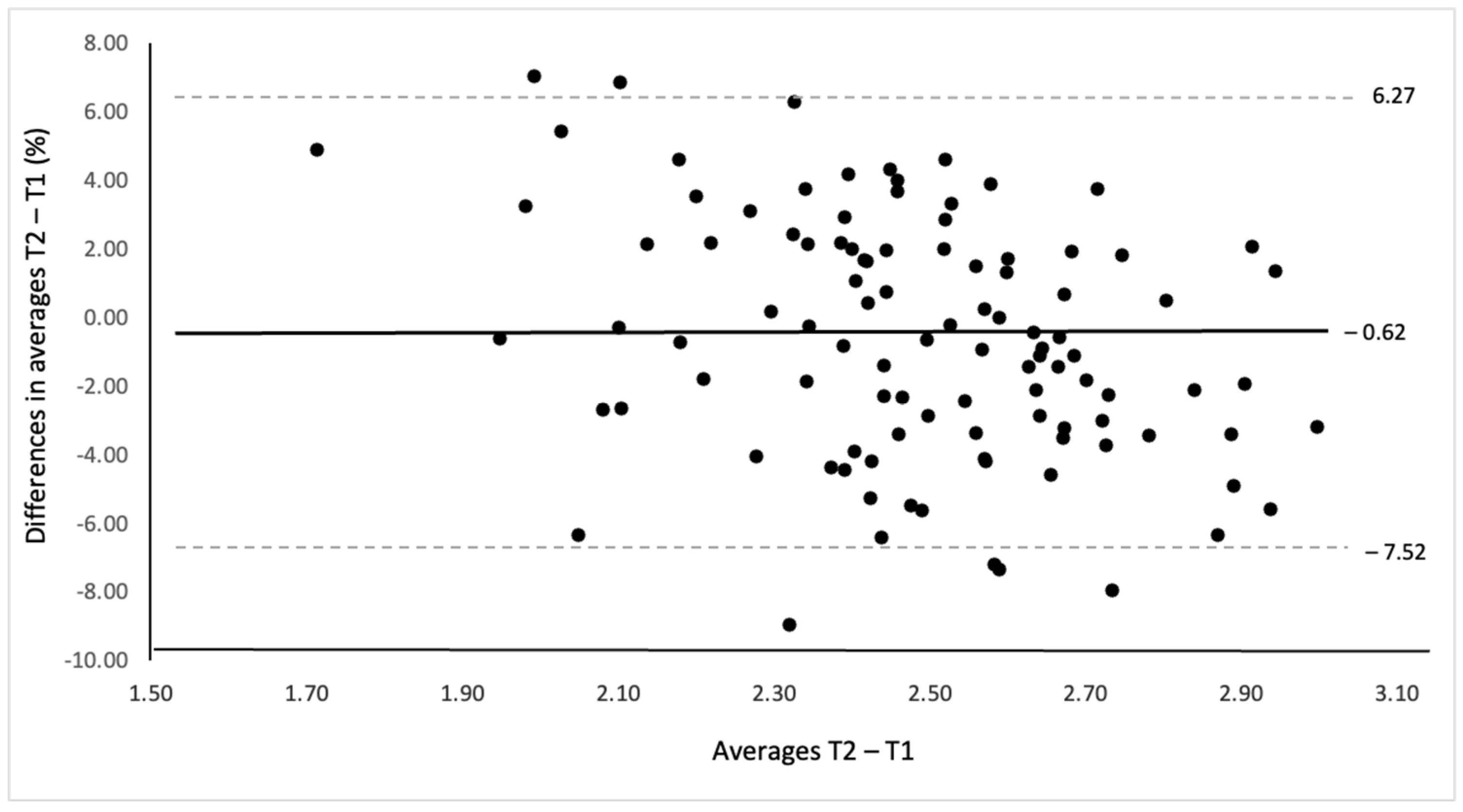

3.2. Reliability of the Questionnaire

3.3. Opinion of the Questionnaire

4. Discussion

4.1. Cross-Cultural Validation

4.2. Reliability and Psychometric Properties

4.3. Potential Uses in Different Fields

4.4. Limitations and Future Lines

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cochrane, W.A. The importance of physique and correct posture in relation to the art of medicine. Br. Med. J. 1924, 1, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Arnold, E.H. Bad posture or deformity? Am. Phys. Educ. Rev. 1926, 31, 1058–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boynton, D.A. Good posture—The ounce of prevention. J. Am. Assoc. Health Phys. Educ. Recreat. 1949, 20, 513–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosario, L.R. What is posture? A review of the literature in search of a definition. EC Orthop. 2017, 6, 111–133. [Google Scholar]

- Baranowska, A.; Sierakowska, M.; Owczarczuk, A.; Olejnik, B.J.; Lankau, A.; Baranowski, P. An analysis of the risk factors for postural defects among early school-aged children. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.; Rawat, V. The importance of body posture in adolescence and its relationship with overall well-being. Indian J. Med. Spec. 2023, 14, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.; Zhang, Y. College students’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding body posture: A cross-sectional survey—Taking a university in Wuhu City as an example. Prev. Med. Rep. 2023, 36, 102422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckmann, T.; Stoddart, D. The power of posture: A program to encourage optimal posture. J. Act. Aging 2015, 14, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Montuori, P.; Cennamo, L.M.; Sorrentino, M.; Pennino, F.; Ferrante, B.; Nardo, A.; Mazzei, G.; Grasso, S.; Salomone, M.; Trama, U.; et al. Assessment on practicing correct body posture and determinant analyses in a large population of a metropolitan area. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vojtíková, L. Defining a mutual relationship among the body posture, physical condition (fitness) and regular physical activity in children of young school-age. Stud. Univ. Babeș-Bolyai Educ. Artis Gymnast. 2020, 65, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Lu, X.; Yan, B.; Huang, Y. Prevalence of incorrect posture among children and adolescents: Finding from a large population-based study in China. iScience 2020, 23, 101043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, M.P.; Carvalho, P.J.; Cavalheiro, L.; Sousa, F.M. Prevalence of postural changes and musculoskeletal disorders in young adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 7191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brzęk, A.; Sołtys, J.; Gallert-Kopyto, W.; Gwizdek, K.; Plinta, R. Body posture in children with obesity—The relationship to physical activity. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Diabetes Metab. 2016, 22, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowicz-Szymańska, A.; Bibro, M.; Wodka, K.; Smola, E. Does excessive body weight change the shape of the spine in children? Child. Obes. 2019, 15, 346–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimes, P.; Legg, S. Musculoskeletal disorders in school students as a risk factor for adult MSD: A review of the multiple factors affecting posture, comfort and health in classroom environments. J. Hum.-Environ. Syst. 2004, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hadidi, F.; Bsisu, I.; AlRyalat, S.A.; Al-Zu’bi, B.; Bsisu, R.; Hamdan, M.; Kanaan, T.; Yasin, M.; Samarah, O. Association between mobile phone use and neck pain in university students: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0217231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburton, D.E.R.; Nicol, W.; Bredin, S.S.D. Health benefits of physical activity: The evidence. CMAJ 2006, 174, 801–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, P.B.; Grahamslaw, K.M.; Kendell, M.; Lapenskie, S.C.; Møller, N.E.; Richards, K.V. The effect of different standing and sitting postures on trunk muscle activity in a pain-free population. Spine 2002, 27, 1238–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crawford, R.J.; Gizzi, L.; Mhuiris, N.; Falla, D. Are regions of the lumbar multifidus differentially activated during walking at varied speed and inclination? J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2016, 30, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, S.W.; Schache, A.; Rath, D.; Hodges, P.W. Changes in three-dimensional lumbo-pelvic kinematics and trunk muscle activity with speed and mode of locomotion. Clin. Biomech. 2005, 20, 784–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crommert, M.E.; Ekblom, M.M.; Thorstensson, A. Activation of transversus abdominis varies with postural demand in standing. Gait Posture. 2011, 33, 473–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyedhoseinpoor, T.; Taghipour, M.; Dadgoo, M.; Sanjari, M.A.; Takamjani, I.E.; Kazemnejad, A.; Khoshamooz, Y.; Hides, J. Alteration of lumbar muscle morphology and composition in relation to low back pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Spine J. 2022, 22, 660–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Physical Activity. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/physical-activity (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Lioret, S.; McNaughton, S.A.; Cameron, A.J.; Crawford, D.; Campbell, K.J. Lifestyle patterns begin in early childhood, persist and are associated with cardiometabolic risk. Nutrients. 2020, 12, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miñana-Signes, V.; Monfort-Pañego, M.; Valiente, J. Teaching back health in the school setting: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaheer, M.; Fatima, N.; Riaz, U.; Haseeb, N. Association of heavy bag lifting time with postural pain in secondary school students. Pak. Biomed. J. 2022, 5, 64–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monfort-Pañego, M.; Molina-García, J.; Miñana-Signes, V.; Bosch-Biviá, A.H.; Gómez-López, A.; Munguía-Izquierdo, D. Development and psychometric evaluation of a health questionnaire on back care knowledge in daily life physical activities for adolescent students. Eur. Spine J. 2016, 25, 2803–2808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noll, M.; Tarragô Candotti, C.; Vieira, A.; Fagundes Loss, J. Back pain and body posture evaluation instrument (BackPEI): Development, content validation and reproducibility. Int. J. Public Health 2013, 58, 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, M.; Bettany-Saltikov, J.; Kandasamy, G.; Aristegui Racero, G. Development of a novel pictorial questionnaire to assess knowledge and behaviour on ergonomics and posture as well as musculoskeletal pain in university students: Validity and reliability. Healthcare 2024, 12, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monfort-Pañego, M.; Miñana-Signes, V. Psychometric study and content validity of a questionnaire to assess back-health-related postural habits in daily activities. Meas. Phys. Educ. Exerc. Sci. 2020, 24, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, V.D.; Rojjanasrirat, W. Translation, adaptation and validation of instruments or scales for use in cross-cultural health care research: A clear and user-friendly guideline. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2011, 17, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthoine, E.; Moret, L.; Regnault, A.; Sébille, V.; Hardouin, J.B. Sample size used to validate a scale: A review of publications on newly developed patient-reported outcomes measures. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2014, 12, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmenter, K.; Wardle, J. Evaluation and design of nutrition knowledge measures. J. Nutr. Educ. 2000, 32, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barchard, K.A.; Pace, L.A. Preventing human error: The impact of data entry methods on data accuracy and statistical results. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011, 27, 1834–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terwee, C.B.; Bot, S.D.; de Boer, M.R.; van der Windt, D.A.; Knol, D.L.; Dekker, J.; Bouter, L.M.; de Vet, H.C. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2007, 60, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozdemir, S.; Gencbas, D.; Tosun, B.; Bebis, H.; Sinan, O. Musculoskeletal pain, related factors, and posture profiles among adolescents: A cross-sectional study from Turkey. Pain Manag. Nurs. 2021, 22, 522–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrout, P.E.; Fleiss, J.L. Intraclass correlations: Uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol. Bull. 1979, 86, 420–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Gabrenya, W.K. In search of cross-cultural competence: A comprehensive review of five measurement instruments. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2021, 82, 37–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruchinho, P.; López-Franco, M.D.; Capelas, M.L.; Almeida, S.; Bennett, P.M.; Miranda da Silva, M.; Teixeira, G.; Nunes, E.; Lucas, P.; Gaspar, F.; et al. Translation, cross-cultural adaptation, and validation of measurement instruments: A practical guideline for novice researchers. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2024, 17, 2701–2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, A.C.F.; Silva, R.M.F.; Campos, M.H.; Bizinotto, T.; de Rezende, L.M.T.; Miñana-Signes, V.; Monfort-Pañego, M.; Silva Noll, P.R.; Noll, M. Evaluating instruments to assess spinal health knowledge in adolescents aged 14–17: A scoping review. J. Hum. Growth Dev. 2024, 34, 524–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalkbrenner, M.T. A practical guide to instrument development and score validation in the social sciences: The MEASURE approach. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2021, 26, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Time | Sex | Age/Years | Mean Score ± SD | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | M | 12–13 | 2.50 ± 0.26 | 20 |

| 14–15 | 2.51 ± 0.21 | 33 | ||

| Total | 2.50 ± 0.22 | 53 | ||

| F | 12–13 | 2.47 ± 0.29 | 15 | |

| 14–15 | 2.40 ± 0.31 | 36 | ||

| Total | 2.42 ± 0.30 | 51 | ||

| Total T1 | 12–13 | 2.48 ± 0.27 | 35 | |

| 14–15 | 2.44 ± 0.27 | 69 | ||

| Total | 2.46 ± 0.27 | 104 | ||

| T2 | M | 12–13 | 2.46 ± 0.21 | 20 |

| 14–15 | 2.49 ± 0.18 | 33 | ||

| Total | 2.48 ± 0.19 | 53 | ||

| F | 12–13 | 2.47 ± 0.30 | 15 | |

| 14–15 | 2.38 ± 0.25 | 36 | ||

| Total | 2.41 ± 0.26 | 51 | ||

| Total T2 | 12–13 | 2.46 ± 0.25 | 104 | |

| 14–15 | 2.43 ± 0.22 | 69 | ||

| Total | 2.44 ± 0.23 | 104 |

| Categories | M ± SD T1 | M ± SD T2 | M ± SD T1–T2 | M ± SD Dif T2–T1 | CC | ICC (95%IC) | CR | SEM | MDC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 2.50 ± 0.26 | 2.48 ± 0.23 | 2.49 ± 0.24 | −0.02 ± 0.09 | 0.94 | 0.96 (0.95–0.98) | 0.17 | 0.02 | 0.05 |

| Standing | 2.89 ± 0.43 | 2.86 ± 0.42 | 2.88 ± 0.41 | −0.03 ± 0.21 | 0.88 | 0.93 (0.90–0.96) | 0.42 | 0.06 | 0.16 |

| Sitting | 2.41 ± 0.43 | 2.45 ± 0.36 | 2.43 ± 0.38 | 0.04 ± 0.19 | 0.90 | 0.94 (0.91–0.96) | 0.38 | 0.05 | 0.13 |

| Transporting | 2.67 ± 0.38 | 2.69 ± 0.31 | 2.68 ± 0.34 | 0.02 ± 0.15 | 0.93 | 0.95 (0.93–0.97) | 0.29 | 0.03 | 0.09 |

| Moving weight | 2.22 ± 0.50 | 2.08 ± 0.47 | 2.15 ± 0.48 | −0.14 * ± 0.16 | 0.95 | 0.97 (0.96–0.98) | 0.31 | 0.03 | 0.08 |

| Lying | 2.29 ± 0.57 | 2.31 ±0.55 | 2.30 ± 0.56 | 0.03 ± 0.12 | 0.98 | 0.99 (0.98–0.99) | 0.24 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Monfort-Pañego, M.; Labecka, M.K.; Miñana-Signes, V.; Jankowicz-Szymańska, A. Cross-Cultural Validity and Reliability of the Questionnaire on Back-Health-Related Postural Habits During Daily Activities in the Polish Young Adolescent Population. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7793. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217793

Monfort-Pañego M, Labecka MK, Miñana-Signes V, Jankowicz-Szymańska A. Cross-Cultural Validity and Reliability of the Questionnaire on Back-Health-Related Postural Habits During Daily Activities in the Polish Young Adolescent Population. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(21):7793. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217793

Chicago/Turabian StyleMonfort-Pañego, Manuel, Marta Kinga Labecka, Vicente Miñana-Signes, and Agnieszka Jankowicz-Szymańska. 2025. "Cross-Cultural Validity and Reliability of the Questionnaire on Back-Health-Related Postural Habits During Daily Activities in the Polish Young Adolescent Population" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 21: 7793. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217793

APA StyleMonfort-Pañego, M., Labecka, M. K., Miñana-Signes, V., & Jankowicz-Szymańska, A. (2025). Cross-Cultural Validity and Reliability of the Questionnaire on Back-Health-Related Postural Habits During Daily Activities in the Polish Young Adolescent Population. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(21), 7793. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217793