Efficacy of Bone Marrow-Derived Stem Cells on Non-Ischemic Cardiomyopathy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Search Strategy

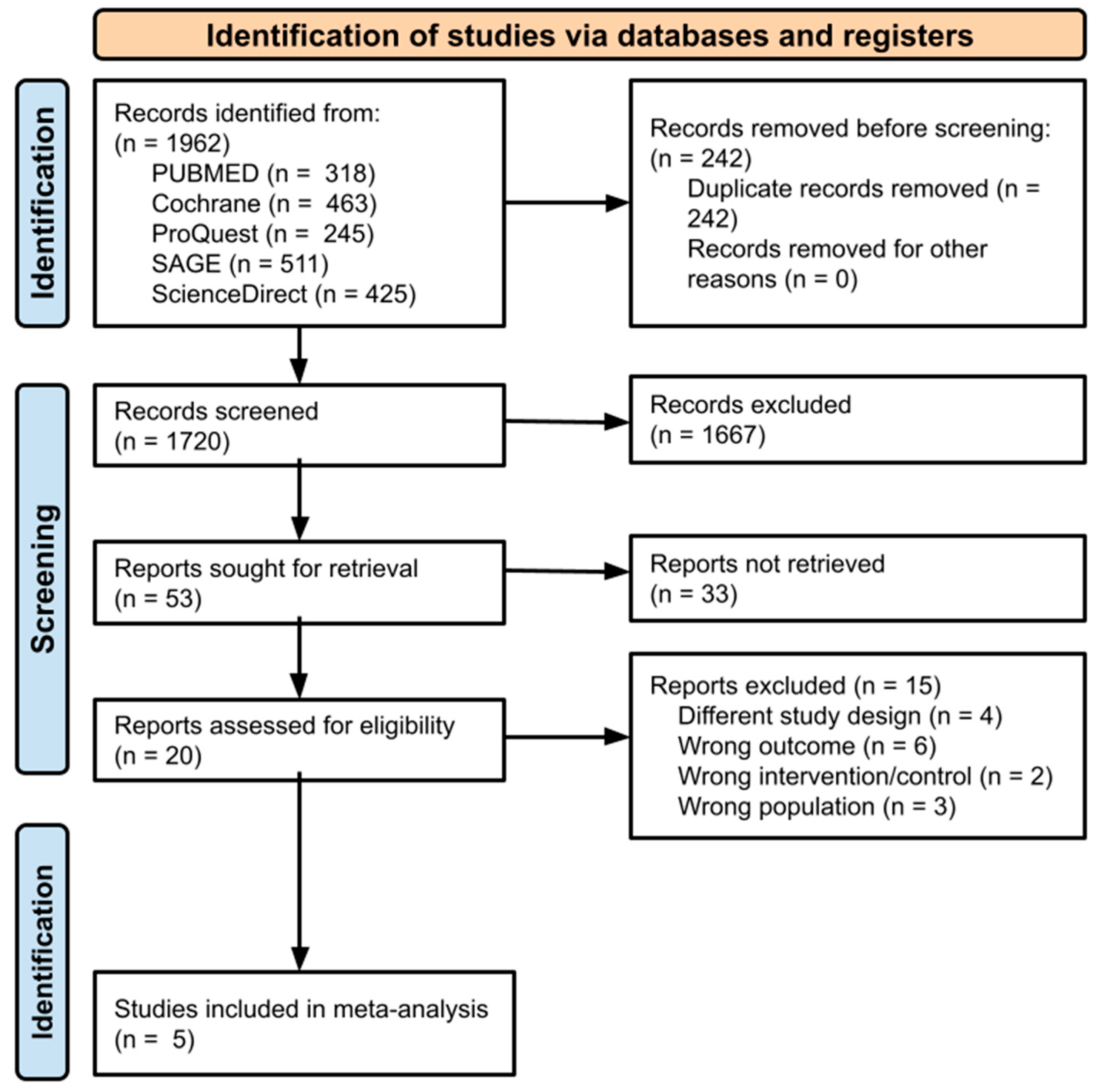

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Data Extractions, Quality Assessment, and Variable Definition

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

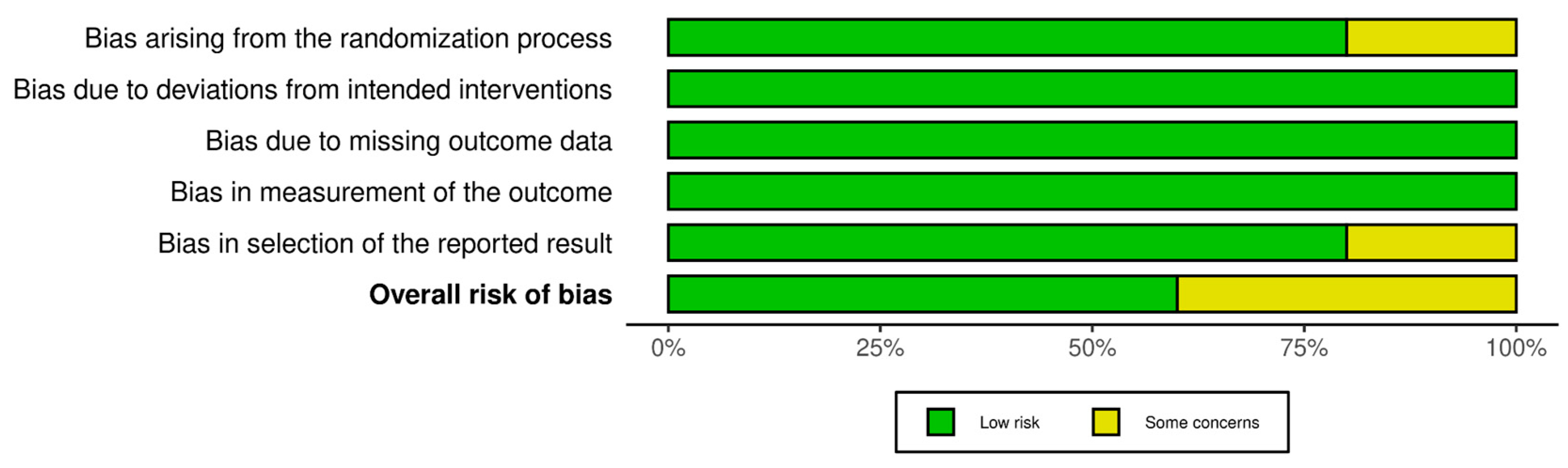

3.1. Quality Assessment

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Meta-Analysis Results

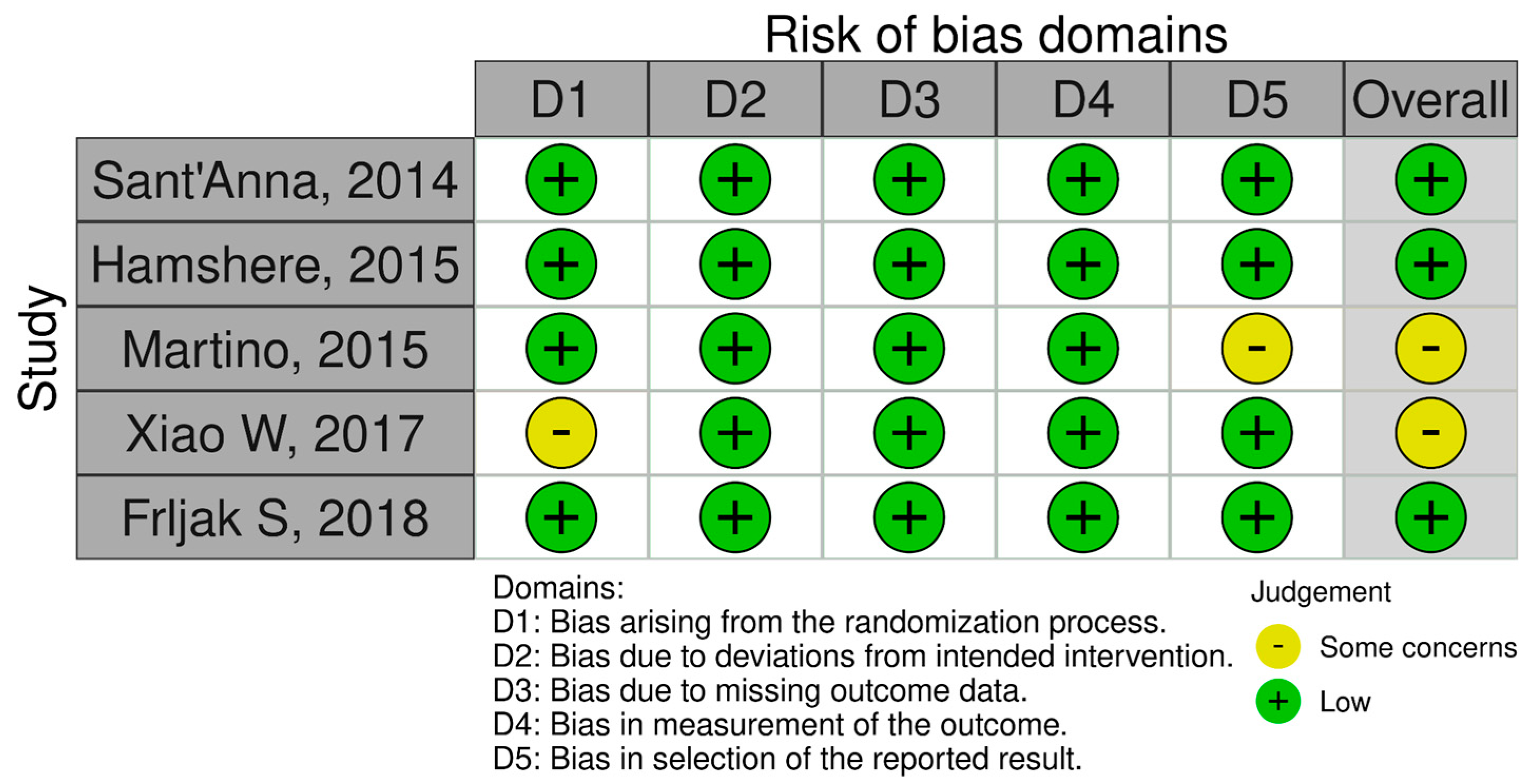

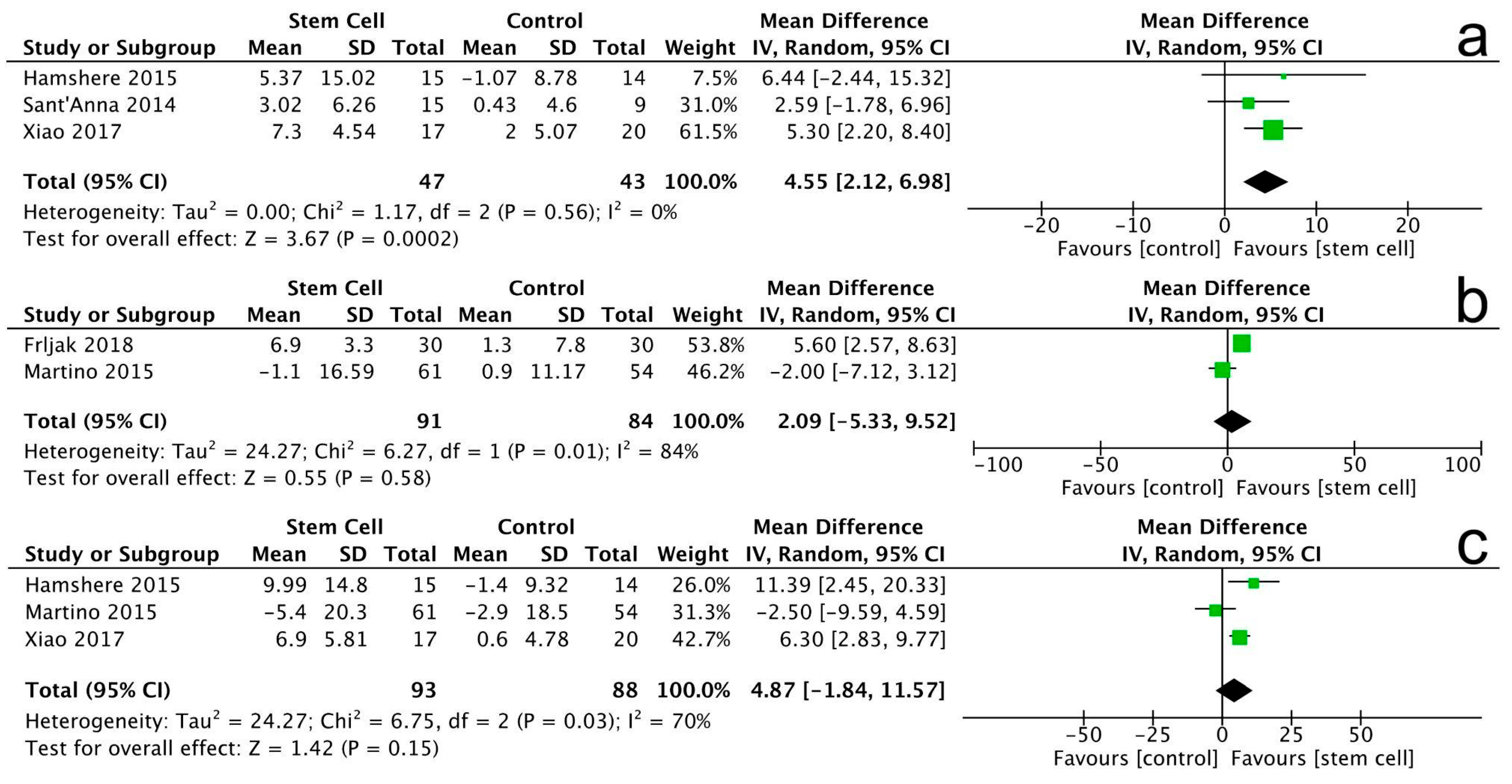

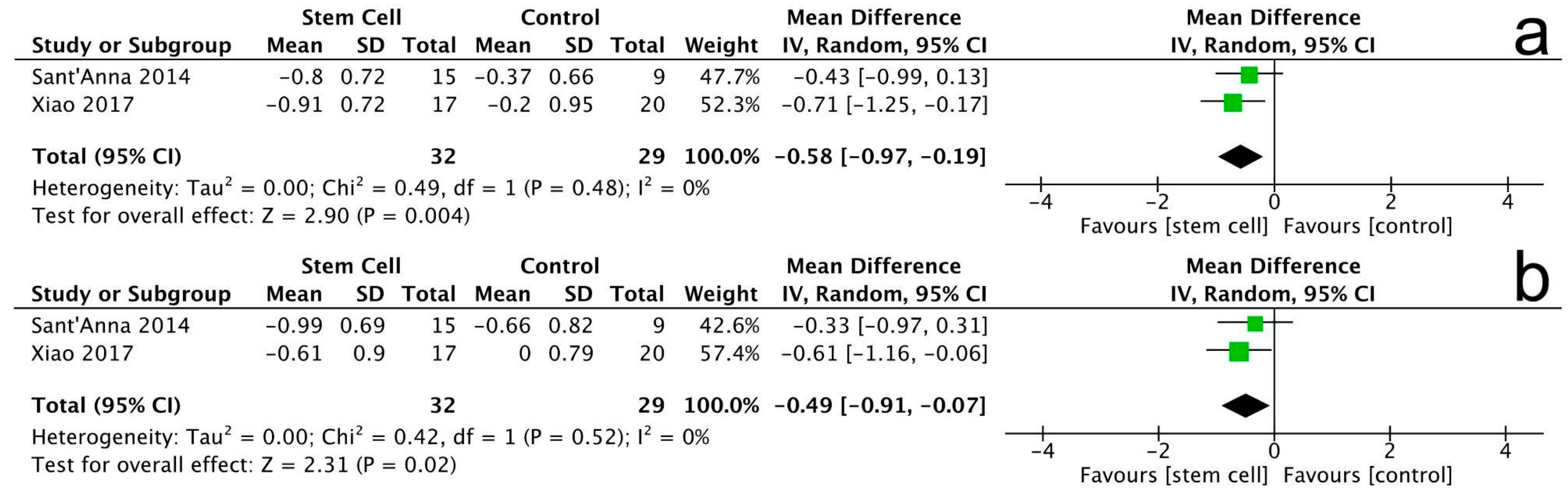

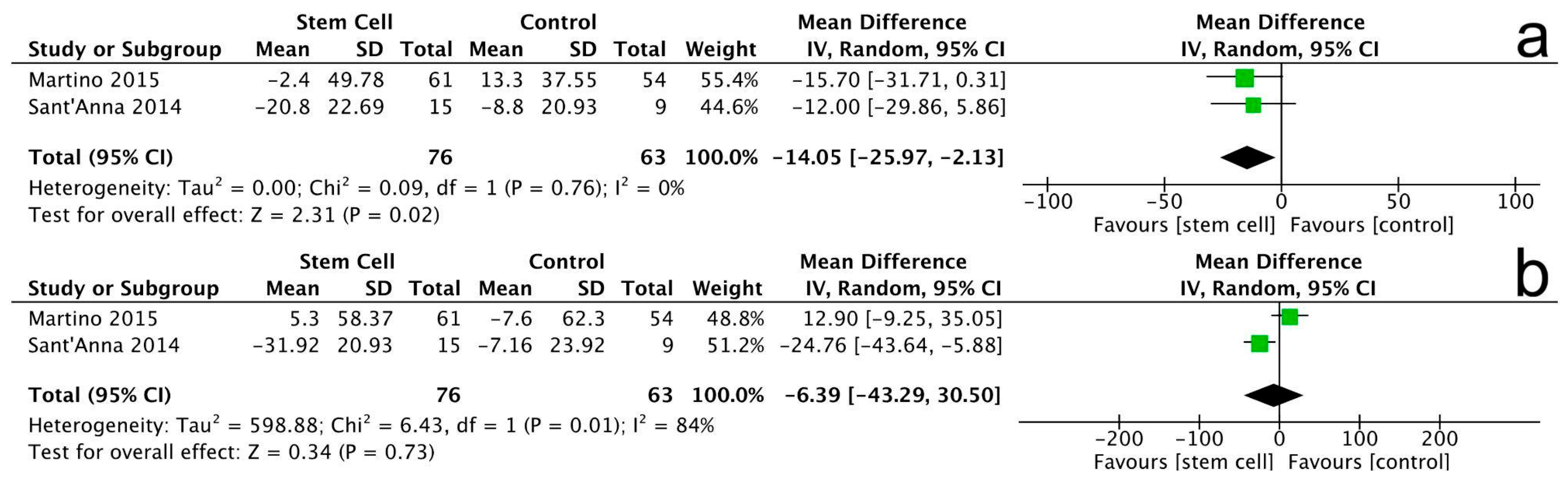

3.3.1. Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction

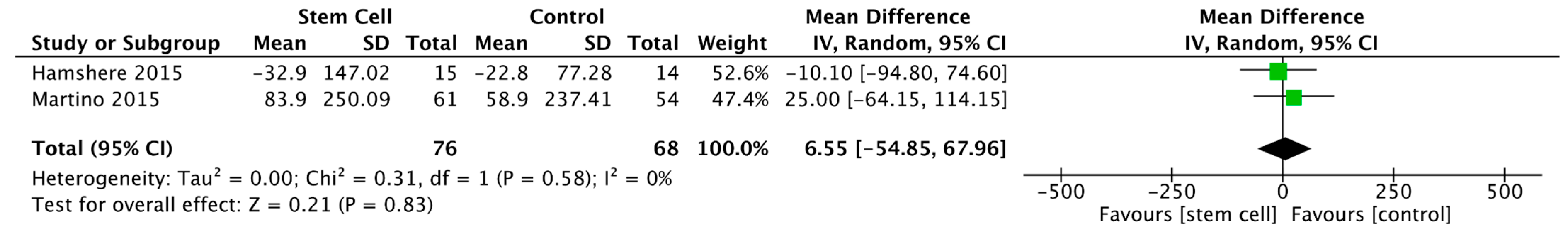

3.3.2. Left Ventricular End-Diastolic Volume

3.3.3. Left Ventricular End-Systolic Volume

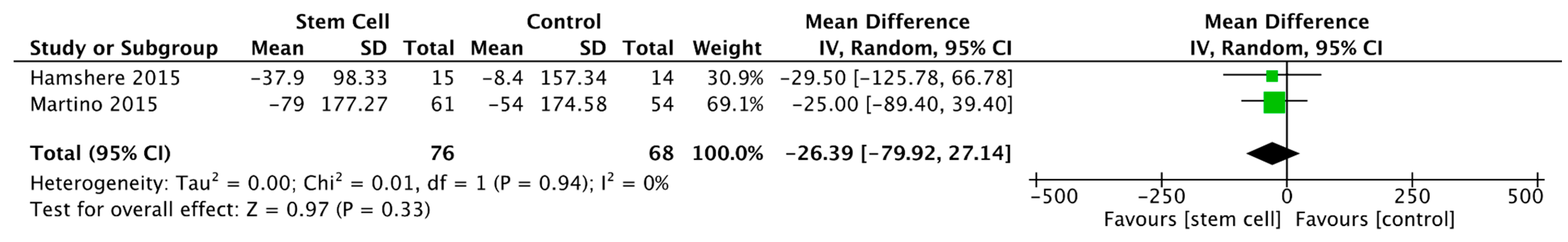

3.3.4. Left Ventricular End-Diastolic Diameter

3.3.5. 6-Minute Walking Test

3.3.6. New York Heart Association (NYHA) Class

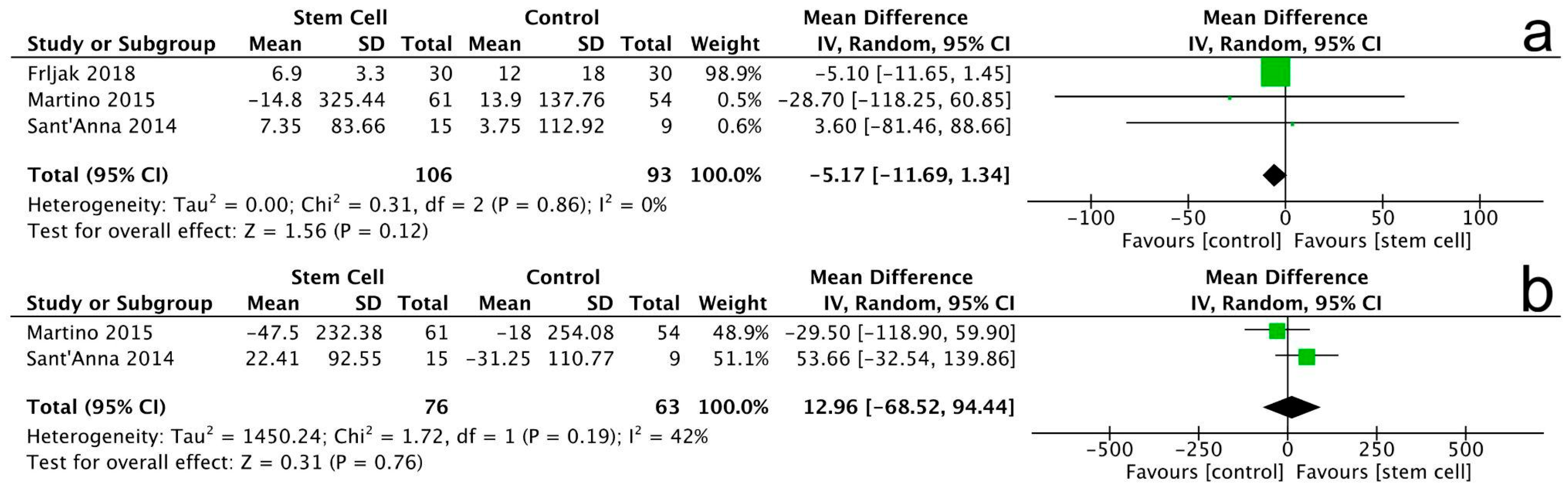

3.3.7. Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire (MLHFQ)

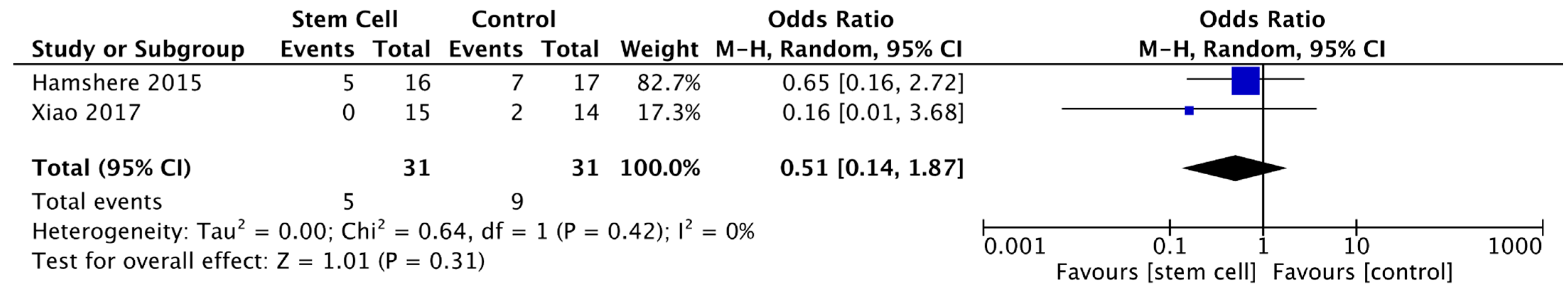

3.3.8. Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events

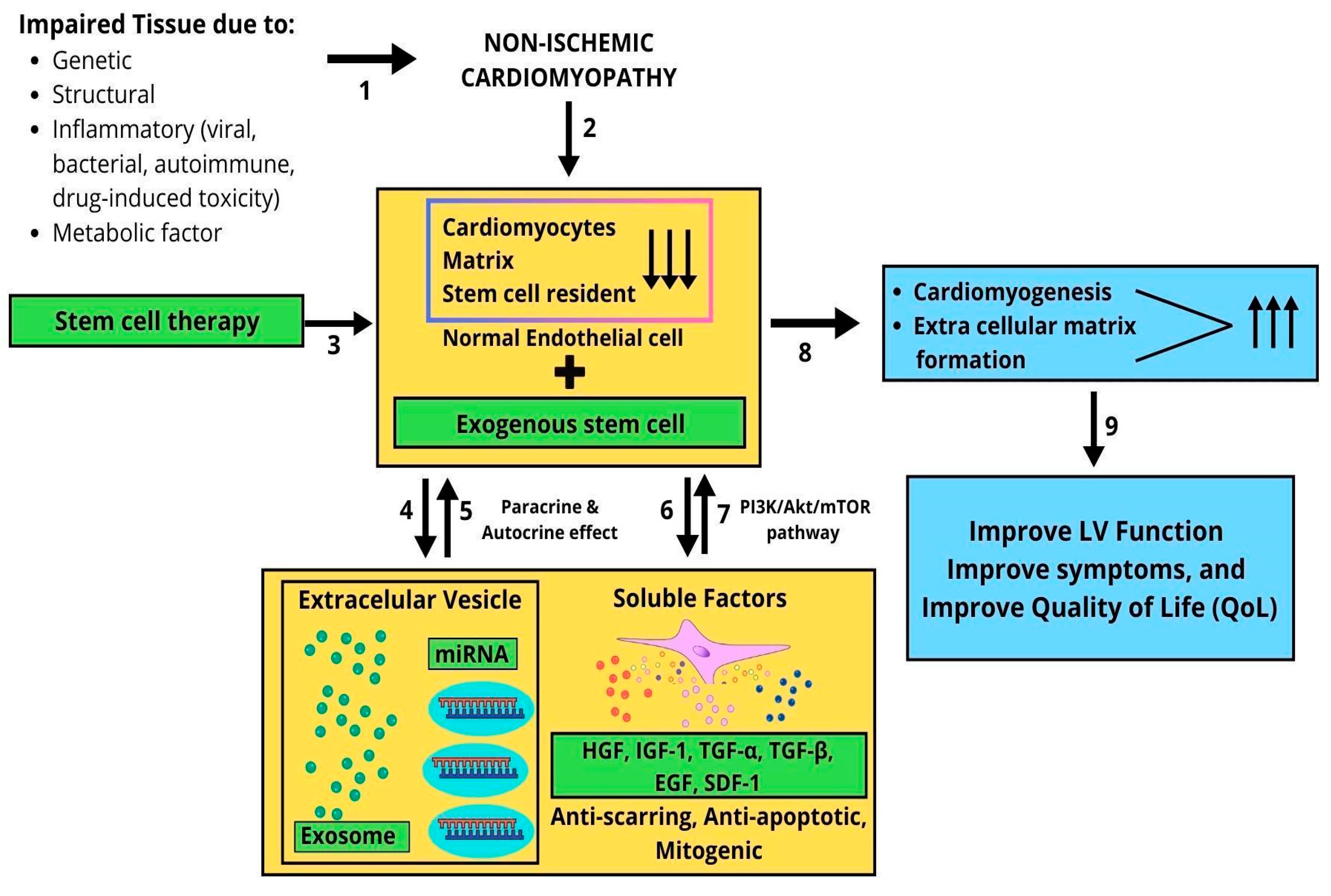

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NICM | Non-ischemic cardiomyopathy |

| ICM | Ischemic cardiomyopathy |

| CT-scan | Computed tomography scan |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| DCM | Dilated cardiomyopathy |

| HCM | Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy |

| RCM | Restrictive cardiomyopathy |

| ARVC | Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy |

| NDLVC | Non-dilated left ventricular cardiomyopathy |

| GBD | Global burden of disease |

| AHA | American Heart Association |

| ESC | European Association of Cardiology |

| DALYs | Disability-adjusted life years |

| WHF | The world heart federation |

| PRISMA | Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| RCTs | Randomized controlled trials |

| LVEF | left ventricular ejection fraction |

| LVEDV | left ventricular end-diastolic volume |

| LVESV | left ventricular end-systolic volume |

| NYHA | New York Heart Association |

| 6MWT | 6-min walk distance test |

| MACE | major cardiac adverse events |

References

- Groeneweg, J.A.; van Dalen, B.M.; Cox, M.P.G.J.; Heymans, S.; Braam, R.L.; Michels, M.; Asselbergs, F.W. 2023 European Society of Cardiology Guidelines on the Management of Cardiomyopathies. Neth. Heart J. 2025, 33, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershberger, R.E.; Hedges, D.J.; Morales, A. Dilated cardiomyopathy: The complexity of a diverse genetic architecture. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2013, 10, 531–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2017 Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death, 1980–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2020, 392, 1736–1788. [Google Scholar]

- GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1204–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbustini, E.; Narula, N.; Dec, G.W.; Reddy, K.S.; Greenberg, B.; Kushwaha, S.; Marwick, T.; Pinney, S.; Bellazzi, R.; Favalli, V.; et al. The MOGE(S) classification for a phenotype-genotype nomenclature of cardiomyopathy: Endorsed by the World Heart Federation. Glob. Heart 2013, 8, 355–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozkurt, B.; Colvin, M.; Cook, J.; Cooper, L.T.; Deswal, A.; Fonarow, G.C.; Francis, G.S.; Lenihan, D.; Lewis, E.F.; McNamara, D.M.; et al. Current diagnostic and treatment strategies for specific dilated cardiomyopathies: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2016, 134, e579–e646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yancy, C.W.; Jessup, M.; Bozkurt, B.; Butler, J.; Casey, D.E., Jr.; Colvin, M.M.; Drazner, M.H.; Filippatos, G.S.; Fonarow, G.C.; Givertz, M.M.; et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA Focused Update of the 2013 Heart Failure Guideline. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017, 70, 776–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandawat, A.; Chattranukulchai, P.; Mandawat, A.; Blood, A.J.; Ambati, S.; Hayes, B.; Rehwald, W.; Kim, H.W.; Heitner, J.F.; Shah, D.J.; et al. Progression of myocardial fibrosis in nonischemic DCM and association with mortality and heart failure outcomes. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2021, 14, 1338–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Køber, L.; Thune, J.J.; Nielsen, J.C.; Haarbo, J.; Videbæk, L.; Korup, E.; Jensen, G.; Hildebrandt, P.; Steffensen, F.H.; Bruun, N.E.; et al. Defibrillator implantation in patients with nonischemic systolic heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1221–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, N.; O’COnnor, C.M.; Chiswell, K.; Anstrom, K.J.; Newby, L.K.; Mentz, R.J. Survival in patients with nonischemic cardiomyopathy with preserved vs reduced ejection fraction. CJC Open 2021, 3, 1333–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Jia, C.; Sun, N.; Zhao, J.; Wang, Z.; Luo, W.; Wang, Z.; Wu, S.; Chen, L.; Luo, X.; et al. Description and prognosis of patients with recovered dilated cardiomyopathy: A retrospective cohort study. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 25, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulin, M.-F.; Deka, A.; Mohamedali, B.; Schaer, G.L. Clinical Benefits of Stem Cells for Chronic Symptomatic Systolic Heart Failure: A Systematic Review of the Existing Data and Ongoing Trials. Cell Transplant. 2016, 25, 1911–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tompkins, B.A.; Rieger, A.C.; Florea, V.; Banerjee, M.N.; Natsumeda, M.; Nigh, E.D.; Landin, A.M.; Rodriguez, G.M.; Hatzistergos, K.E.; Schulman, I.H.; et al. Comparison of Mesenchymal Stem Cell Efficacy in Ischemic Versus Nonischemic Dilated Cardiomyopathy. J. Am. Hear. Assoc. 2018, 7, e008460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponikowski, P.; Voors, A.A.; Anker, S.D.; Bueno, H.; Cleland, J.G.F.; Coats, A.J.S.; Falk, V.; González-Juanatey, J.R.; Harjola, V.-P.; Jankowska, E.A.; et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 2016, 37, 2129–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathiasen, A.B.; Kastrup, J. Stem cell therapy in ischemic heart disease: Current status and future perspectives. Future Cardiol. 2019, 15, 275–285. [Google Scholar]

- Hare, J.M.; DiFede, D.L.; Rieger, A.C.; Florea, V.; Landin, A.M.; El-Khorazaty, J.; Khan, A.; Mushtaq, M.; Lowery, M.H.; Byrnes, J.J.; et al. Randomized comparison of allogeneic versus autologous mesenchymal stem cells for nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy: POSEIDON-DCM trial. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2017, 6, e005969. [Google Scholar]

- Marquis-Gravel, G.; Stevens, L.M.; Mansour, S.; Avram, R.; Noiseux, N. Stem cell therapy for the treatment of nonischemic cardiomyopathy: A systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Can. J. Cardiol. 2014, 30, 1378–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sant’Anna, R.T.; Fracasso, J.; Valle, F.H.; Castro, I.; Nardi, N.B.; Sant’Anna, J.R.M.; Nesralla, I.R.; Kalil, R.A.K. Direct intramyocardial transthoracic transplantation of bone marrow mononuclear cells for non-ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy: INTRACELL, a prospective randomized controlled trial. Rev. Bras. J. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2014, 29, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamshere, S.; Arnous, S.; Choudhury, T.; Choudry, F.; Mozid, A.; Yeo, C.; Barrett, C.; Saunders, N.; Gulati, A.; Knight, C.; et al. Randomized trial of combination cytokine and adult autologous bone marrow progenitor cell administration in patients with non-ischaemic dilated cardiomyopathy: The REGENERATE-DCM clinical trial. Eur. Heart J. 2015, 36, 3061–3069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martino, H.; Brofman, P.; Greco, O.; Bueno, R.; Bodanese, L.; Clausell, N.; Maldonado, J.A.; Mill, J.; Braile, D.; Moraes, J.; et al. Multicentre, randomized, double-blind trial of intracoronary autologous mononuclear bone marrow cell injection in non-ischaemic dilated cardiomyopathy (the dilated cardiomyopathy arm of the MiHeart study). Eur. Heart J. 2015, 36, 2898–2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, W.; Guo, S.; Gao, C.; Dai, G.; Gao, Y.; Li, M.; Wang, X.; Hu, D. A randomized comparative study on the efficacy of intracoronary infusion of autologous bone marrow mononuclear cells and mesenchymal stem cells in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. Int. Heart J. 2017, 58, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frljak, S.; Jaklic, M.; Zemiljic, G.; Cerar, A.; Poglajen, G.; Vrtovec, B. CD34+ cell transplantation improves right ventricular function in patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2018, 7, 168–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, S.; Yu, L.; Li, J.; Wu, J.; Yang, D.; Xue, T.; Zhang, L.; Xie, Z.; Huang, X. Stem cell therapy for non-ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst. Rev. 2024, 13, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavousi, S.; Hosseinpour, A.; Bahmanzadegan Jahromi, F.; Attar, A. Efficacy of mesenchymal stem cell transplantation on major adverse cardiovascular events and cardiac function indices in patients with chronic heart failure: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, A.; Guha, A.; Thakur, R.K. Stem cell therapy for non-ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2022, 11, 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Vrtovec, B.; Poglajen, G.; Lezaic, L.; Sever, M.; Domanovic, D.; Cernelc, P.; Socan, A.; Schrepfer, S.; Torre-Amione, G.; Haddad, F.; et al. Effects of intracoronary CD34⁺ stem cell transplantation in nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy patients: A randomized controlled trial. Circulation 2013, 127, 1681–1691. [Google Scholar]

- Vrtovec, B.; Poglajen, G.; Sever, M.; Zemljic, G.; Frljak, S.; Cerar, A.; Cukjati, M.; Jaklic, M.; Cernelc, P.; Haddad, F.; et al. Effects of transendocardial CD34⁺ cell transplantation in patients with ischemic and nonischemic cardiomyopathy. Circ. Heart Fail. 2011, 4, e001510. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer-Rasokat, U.; Assmus, B.; Seeger, F.H.; Honold, J.; Leistner, D.; Fichtlscherer, S.; Schächinger, V.; Tonn, T.; Martin, H.; Dimmeler, S.; et al. A pilot trial to assess potential effects of selective intracoronary bone marrow–derived progenitor cell infusion in patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2009, 2, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segers, V.F.M.; De Keulenaer, G.W. Autocrine signaling in cardiac remodeling: A rich source of therapeutic targets. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2021, 10, e019169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanganalmath, S.K.; Bolli, R. Cell therapy for heart failure: A comprehensive overview of experimental and clinical studies, current challenges, and future directions. Circ. Res. 2013, 113, 810–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| No | First Author Name, Year | Study Design | Country of Origin | Number of Participants | Type of Stem Cell | Dose of Cells Injected (n) | Route of Administration | Duration of Follow-Up | Outcome of Interest |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sant’Anna RT et al., 2014 [20] | RCT | Brazil | 30 | BMMC | 1.06 ± 0.43 × 108 | Intramyocardial, transthoracic transplantation | 3 months & 9 months | LVEF, LVESV, LVEDV, 6-MWT, NYHA, MLHFQ |

| 2 | Hamshere S et al., 2015 [21] | RCT | UK | 60 | BMSC | 216.0 ± 221.8 × 106 | Intracoronary infusion | 3 months & 12 months | LVEF, LVESV, LVEDV, NYHA, NT-proBNP, MACE |

| 3 | Martino H et al., 2015 [22] | RCT | Brazil | 115 | BMMC | 8 × 107 | Intracoronary injection | 6 months & 12 months | LVEF, LVESV, LVEDV, NYHA, 6-MWT, MLHFQ |

| 4 | Xiao W et al., 2017 [23] | RCT | China | 37 | BMMC | 5.1 ± 2.0 × 108 | Intracoronary infusion | 3 months and 12 months | LVEF, MPD, LVEDd, NYHA, MACE |

| 5 | Frljak S et al., 2018 [24] | RCT | USA | 60 | CD34+ | 8 × 107 | Transendocardial | 6 months | LVEF, TAPSE, NT-proBNP, 6-MWT, LVEDd |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Soetisna, T.W.; Pajala, F.B.; Alzikri, H.R.; Millenia, M.S.; Santoso, A.; Listiyaningsih, E. Efficacy of Bone Marrow-Derived Stem Cells on Non-Ischemic Cardiomyopathy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7610. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217610

Soetisna TW, Pajala FB, Alzikri HR, Millenia MS, Santoso A, Listiyaningsih E. Efficacy of Bone Marrow-Derived Stem Cells on Non-Ischemic Cardiomyopathy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(21):7610. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217610

Chicago/Turabian StyleSoetisna, Tri Wisesa, Fegita Beatrix Pajala, Harry Raihan Alzikri, Maasa Sunreza Millenia, Anwar Santoso, and Erlin Listiyaningsih. 2025. "Efficacy of Bone Marrow-Derived Stem Cells on Non-Ischemic Cardiomyopathy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 21: 7610. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217610

APA StyleSoetisna, T. W., Pajala, F. B., Alzikri, H. R., Millenia, M. S., Santoso, A., & Listiyaningsih, E. (2025). Efficacy of Bone Marrow-Derived Stem Cells on Non-Ischemic Cardiomyopathy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(21), 7610. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217610