Neuroprotective Effects of N-Acetylcysteine-Amide (AD4) in a Survival Mouse Model of Paraoxon Intoxication: Targeting Oxidative Stress, Neuroinflammation and Memory Impairments

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

2.2. Drugs and Materials

2.3. In Vivo Treatment Schedule—Survival Mouse Model of Acute POX Poisoning

2.4. Bio- and Neurochemical Assays

2.4.1. Tissue Sample Preparation and Protein Extraction

2.4.2. Western Blotting and Immunodetection

2.4.3. Lipid Peroxidation (4-HNE) ELISA Kit

2.4.4. Tissue Preparation and Immunohistochemistry

2.5. Behavioral Assays

2.5.1. Novel Object Recognition Test (NORT)

2.5.2. Horizontal Locomotor Activity (HLA)

2.6. Data Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. AD4 Reverses the POX-Induced Reduction in GPx1 Expression and Prevents the Increase in Hippocampal 4-HNE Levels

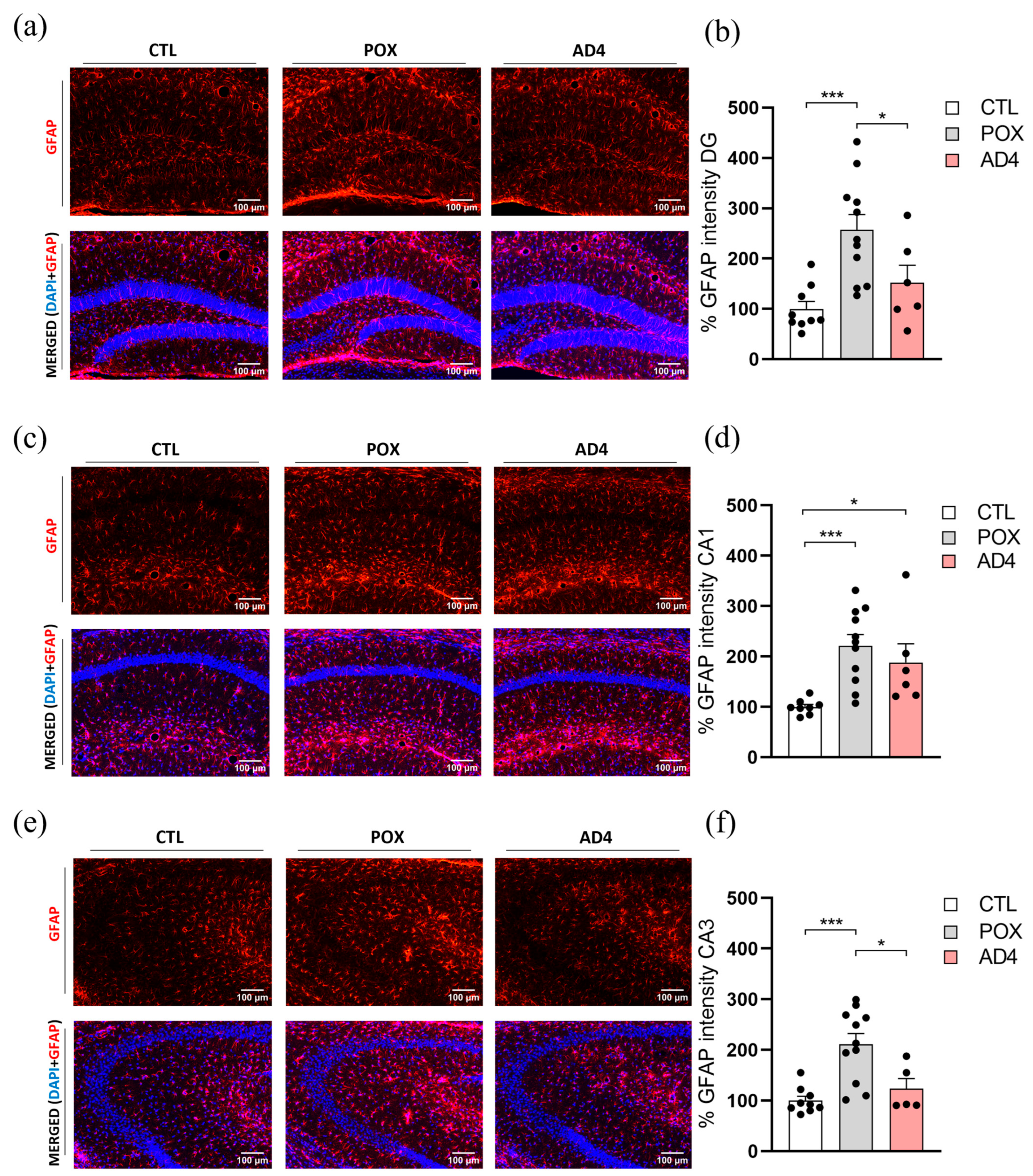

3.2. AD4 Mitigates POX-Induced Astroglial and Microglial Responses in the Hippocampus

3.3. AD4 Improves Recognition Memory Deficits in POX-Exposed Surviving Mice

3.4. AD4 Does Not Affect Basal Hyperlocomotion Induced by Acute POX Intoxication

3.5. Summary Results

| Effect | Effect of POX | Restored Parameters by AD4 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxidative stress | HP | PFC | HP | PFC | ||||

| GPx1 ↓ | GPx1 ↓ | GPx1 | GPx1 | |||||

| CAT ↓ | CAT (ns.) | - | - | |||||

| 4-HNE ↑ | 4-HNE (ns.) | 4-HNE | - | |||||

| Neuroinflammation | DG (HP) | CA1 (HP) | CA3 (HP) | DG (HP) | CA1 (HP) | CA3 (HP) | ||

| GFAP ↑ | GFAP ↑ | GFAP ↑ | GFAP | - | GFAP | |||

| IBA-1 ↑ | IBA-1 (ns.) | IBA-1(ns.) | IBA-1 | - | - | |||

| Cognitive deficits | NORT DI ↓ | NORT DI | ||||||

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 2-PAM | Pralidoxime |

| 4-HNE | 4-Hydroxynonenal |

| Ach | Acetylcholine |

| AChE | Acetylcholinesterase |

| AD4 | N-acetylcysteine-amide |

| BBB | Blood–brain barrier |

| CAT | Catalase |

| DG | Dentate Gyrus |

| DFP | Diisopropyl phosphorofluoridate |

| DI | Discrimination Index |

| FBS | Fetal Bovine Serum |

| GFAP | Glial Fibrilary Acidic Protein |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| GPx1 | Glutathione Peroxidase 1 |

| HP | Hippocampus |

| HLA | Horizontal Locomotor Activity |

| i.p. | Intraperitoneal |

| Iba-1 | Ionized Calcium Binding Adaptor Molecule 1 |

| MDA | Malonaldehyde |

| NAC | N-acetylcysteine |

| NORT | Novel Object Recognition Test |

| OP | Organophosphorus |

| O/N | Overnight |

| PFA | Paraformaldehyde |

| POX | Paraoxon |

| PB | Phosphate Buffer |

| PBS | Phosphate-Buffered Saline |

| PFC | Prefrontal Cortex |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| SEM | Standard Error of the Mean |

| S.E. | Status Epilepticus |

| s.c. | Subcutaneously |

References

- Balali-Mood, B. Basic and Clinical Toxicology of Organophosphorus Compounds; Balali-Mood, M., Abdollahi, M., Eds.; Springer: London, UK, 2014; ISBN 9781447156253. [Google Scholar]

- Gunnell, D.; Eddleston, M.; Phillips, M.R.; Konradsen, F. The Global Distribution of Fatal Pesticide Self-Poisoning: Systematic Review. BMC Public Health 2007, 7, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddleston, M.; Buckley, N.A.; Eyer, P.; Dawson, A.H.; Straub, W. Management of Acute Organophosphorus Pesticide Poisoning. Lancet 2008, 371, 597–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyaratnam, J. Health Problems of Pesticide Usage in the Third World. Br. J. Ind. Med. 1985, 42, 505–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, M.; Salehi, M.; Asgari, A.; Ahmadi, S.; Abbasnezhad, M.; Hajihoosani, R.; Hajigholamali, M. Effects of Paraoxon on Serum Biochemical Parameters and Oxidative Stress Induction in Various Tissues of Wistar and Norway Rats. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2012, 34, 876–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhagwat, K. A Review on OP Toxicity in the Farmers of Solapur District from India. Int. J. Biol. Res. 2014, 2, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Zhang, D.; Liu, X.; Nie, H.; Ouyang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, Z. Screening of Efficient Salicylaldoxime Reactivators for DFP and Paraoxon-Inhibited Acetylcholinesterase. RSC Med. Chem. 2024, 15, 1225–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pannu, A.K.; Bhalla, A.; Vamshi, V.; Upadhyay, M.K.; Sharma, N.; Kumar, S. Changing Spectrum of Acute Poisoning in North India: A Hospital-Based Descriptive Study. Turk. J. Emerg. Med. 2022, 22, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pena-Llopis, S. Antioxidants as Potentially Safe Antidotes for Organophosphorus Poisoning. Curr. Enzym. Inhib. 2005, 1, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, R.E.; Hawkins, E.; Pinchbeck, L.R.; DeLorenzo, R.J.; Deshpande, L.S. Chronic Epilepsy and Mossy Fiber Sprouting Following Organophosphate-Induced Status Epilepticus in Rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2024, 388, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinka, E.; Kälviäinen, R. 25 Years of Advances in the Definition, Classification and Treatment of Status Epilepticus. Seizure 2017, 44, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolić, D.; Kovarik, Z. N-Methyl-d-Aspartate Receptors: Structure, Function, and Role in Organophosphorus Compound Poisoning. BioFactors 2024, 50, 868–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, S.E.; Loose, M.D.; Qi, M.; Levey, A.I.; Hille, B.; Mcknight, G.S.; Idzerda, R.L.; Nathanson, N.M. Disruption of the M1 Receptor Gene Ablates Muscarinic Receptor-Dependent M Current Regulation and Seizure Activity in Mice. Neurobiology 1997, 94, 13311–13316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lallement, G.; Carpentier, P.; Collet, A.; Pernot-Marino, I.; Baubichon, D.; Blanchet, G. Effects of Soman-Induced Seizures on Different Extracellular Amino Acid Levels and on Glutamate Uptake in Rat Hippocampus. Brain Res. 1991, 563, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelsl, R.L.; Rothman, S.M. Glutamate Neurotoxicity in Vitro: Antagonist Pharmacology and Intracellular Calcium Concentrations. J. Neurosci. 1990, 10, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapur, J. Role of NMDA Receptors in the Pathophysiology and Treatment of Status Epilepticus. Epilepsia Open 2018, 3, 165–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, M.; Garcia-Reyero, N.; Padrós, F.; Babin, P.J.; Sebastián, D.; Cachot, J.; Prats, E.; Arick, M.; Rial, E.; Knoll-Gellida, A.; et al. Zebrafish Models for Human Acute Organophosphorus Poisoning. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 15591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S.; Singh, S.; Chahal, K.S.; Prakash, A. Potential Pharmacological Strategies for the Improved Treatment of Organophosphate-Induced Neurotoxicity. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2014, 92, 893–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urquizu, E.; Paratusic, S.; Goyenechea, J.; Gómez-Canela, C.; Fumàs, B.; Pubill, D.; Raldúa, D.; Camarasa, J.; Escubedo, E.; López-Arnau, R. Acute Paraoxon-Induced Neurotoxicity in a Mouse Survival Model: Oxidative Stress, Dopaminergic System Alterations and Memory Deficits. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golime, R.R.; Singh, N.; Rajput, A.; DP, N.; Lodhi, V.K. Chronic Sub Lethal Nerve Agent (Soman) Exposure Induced Long-Term Neurobehavioral, Histological, and Biochemical Alterations in Rats. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 2024, 136, 102388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deshpande, L.S.; Lou, J.K.; Mian, A.; Blair, R.E.; Sombati, S.; Attkisson, E.; DeLorenzo, R.J. Time Course and Mechanism of Hippocampal Neuronal Death in an in Vitro Model of Status Epilepticus: Role of NMDA Receptor Activation and NMDA Dependent Calcium Entry. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2008, 583, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deshpande, L.S.; Carter, D.S.; Phillips, K.F.; Blair, R.E.; DeLorenzo, R.J. Development of Status Epilepticus, Sustained Calcium Elevations and Neuronal Injury in a Rat Survival Model of Lethal Paraoxon Intoxication. Neurotoxicology 2014, 44, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenstock, L.; Keifer, M.; Daniell, W.E.; Rosenstock, L.; Barnhart, S.; Costa, L.G.; Daniell, W.E.; Demers, P.; Eaton, D.; Morris, S.; et al. Chronic Central Nervous System Effects of Acute Organophosphate Pesticide Intoxication. Lancet 1991, 338, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, E.P.; Keefe, T.J.; Mounce, L.M.; Heaton, R.K.; Lewis, J.A.; Burcar, P.J. Chronic Neurological Sequelae of Acute Organophosphate Pesticide Poisoning. Arch. Environ. Health 1988, 43, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyaki, K.; Nishiwaki, Y.; Maekawa, K.; Ogawa, Y.; Asukai, N.; Yoshimura, K.; Etoh, N.; Matsumoto, Y.; Kikuchi, Y.; Kumagai, N.; et al. Effects of Sarin on the Nervous System of Subway Workers Seven Years after the Tokyo Subway Sarin Attack. J. Occup. Health 2005, 47, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishiwaki, Y.; Maekawa, K.; Ogawa, Y.; Asukai, N.; Minami, M.; Omae, K.; Health, S.; Group, E.S. Effects of Sarin on the Nervous System in Rescue Team Staff Members and Police Officers 3 Years after the Tokyo Subway Sarin Attack. Environ. Health Perspect. 2001, 109, 1169–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sultana, R.; Perluigi, M.; Butterfield, D.A. Lipid Peroxidation Triggers Neurodegeneration: A Redox Proteomics View into the Alzheimer Disease Brain. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2013, 62, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenini, G.; Lloret, A.; Cascella, R. Oxidative Stress in Neurodegenerative Diseases: From a Mitochondrial Point of View. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 2105607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, P.K.; Sheridan, R.D.; Green, A.C.; Scott, I.R.; Tattersall, J.E.H. A Guinea Pig Hippocampal Slice Model of Organophosphate-Induced Seizure Activity. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2004, 310, 678–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farizatto, K.L.G.; McEwan, S.A.; Naidoo, V.; Nikas, S.P.; Shukla, V.G.; Almeida, M.F.; Byrd, A.; Romine, H.; Karanian, D.A.; Makriyannis, A.; et al. Inhibitor of Endocannabinoid Deactivation Protects Against In Vitro and In Vivo Neurotoxic Effects of Paraoxon. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2017, 63, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenkraft, A.; Falk, A.; Finkelstein, A. The Role of Glutamate and the Immune System in Organophosphate-Induced CNS Damage. Neurotox. Res. 2013, 24, 265–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rambabu, L.; Megson, I.L.; Eddleston, M. Does Oxidative Stress Contribute to Toxicity in Acute Organophosphorus Poisoning?–A Systematic Review of the Evidence. Clin. Toxicol. 2020, 58, 437–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, K.A.; Ezz El-Din, E.M.; Ahmed, N.S.; El-Seedy, A.S. Effect of N-Acetylcysteine on Attenuation of Chlropyrifos and Its Methyl Analogue Toxicity in Male Rats. Toxicology 2021, 461, 152904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piotr, A.; Konrad, J.; Hubert, B.; Krzysztof, Ł.; Grzegorz, R. N-Acetylcysteine as a Potentially Safe Adjuvant in the Treatment of Neurotoxicity Due to Pirimiphos-Methyl Poisoning. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2024, 135, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, J.J.; Nagar, D.P.; Gujar, N.L.; Bhattacharya, R. Oxidative and Histopathological Alterations after Sub-Acute Exposure of Diisopropyl Phosphorofluoridate in Mice: Beneficial Effect of N-acetylcysteine. Life Sci. 2019, 228, 98–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Rodríguez, S.; Cano-Cebrián, M.J.; Esposito-Zapero, C.; Pérez, S.; Guerri, C.; Zornoza, T.; Polache, A. N-Acetylcysteine Normalizes Brain Oxidative Stress and Neuroinflammation Observed after Protracted Ethanol Abstinence: A Preclinical Study in Long-Term Ethanol-Experienced Male Rats. Psychopharmacology 2023, 240, 725–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, A.M.; Hassanen, E.I.; Ogaly, H.A.; Al Dulmani, S.A.; Al-Zahrani, F.A.M.; Galal, M.K.; Kamel, S.; Rashad, M.M.; Ibrahim, M.A.; Hussien, A.M. The Ameliorative Effect of N-Acetylcysteine against Penconazole Induced Neurodegenerative and Neuroinflammatory Disorders in Rats. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2021, 35, e22884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, R.S.B.; Empey, P.E.; Kochanek, P.M.; Bell, M.J. N-Acetylcysteine and Probenecid Adjuvant Therapy for Traumatic Brain Injury. Neurotherapeutics 2023, 20, 1529–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuni, Y.; Goldstein, S.; Dean, O.M.; Berk, M. The Chemistry and Biological Activities of N-Acetylcysteine. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2013, 1830, 4117–4129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atlas, D. Emerging Therapeutic Opportunities of Novel Thiol-Amides, NAC-Amide (AD4/NACA) and Thioredoxin Mimetics (TXM-Peptides) for Neurodegenerative-Related Disorders. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2021, 176, 120–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Offen, D.; Gilgun-Sherki, Y.; Barhum, Y.; Benhar, M.; Grinberg, L.; Reich, R.; Melamed, E.; Atlas, D. A Low Molecular Weight Copper Chelator Crosses the Blood-Brain Barrier and Attenuates Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis. J. Neurochem. 2004, 89, 1241–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinberg, L.; Fibach, E.; Amer, J.; Atlas, D. N-Acetylcysteine Amide, a Novel Cell-Permeating Thiol, Restores Cellular Glutathione and Protects Human Red Blood Cells from Oxidative Stress. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2005, 38, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penugonda, S.; Mare, S.; Goldstein, G.; Banks, W.A.; Ercal, N. Effects of N-Acetylcysteine Amide (NACA), a Novel Thiol Antioxidant against Glutamate-Induced Cytotoxicity in Neuronal Cell Line PC12. Brain Res. 2005, 1056, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun Lee, K.; Ri Kim, S.; Sun Park, H.; Ju Park, S.; Hoon Min, K.; Young Lee, K.; Hun Choe, Y.; Hyun Hong, S.; Jin Han, H.; Rae Lee, Y.; et al. A Novel Thiol Compound, N-Acetylcysteine Amide, Attenuates Allergic Airway Disease by Regulating Activation of NF-ΚB and Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1α. Exp. Mol. Med. 2007, 39, 756–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racine, R.J. Modification of Seizure Activity by Electrical Stimulation: II. Motor Seizure. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1972, 32, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueiredo, T.H.; Qashu, F.; Apland, J.P.; Aroniadou-Anderjaska, V.; Souza, A.P.; Braga, M.F.M. The GluK1 (GluR5) Kainate/α-Amino-3-Hydroxy-5-Methyl-4-Isoxazolepropionic Acid Receptor Antagonist LY293558 Reduces Soman-Induced Seizures and Neuropathology. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2011, 336, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amer, J.; Atlas, D.; Fibach, E. N-Acetylcysteine Amide (AD4) Attenuates Oxidative Stress in Beta-Thalassemia Blood Cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2008, 1780, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, R.; Zheng, W.; Ginman, T.; Ottosson, H.; Norgren, S.; Zhao, Y.; Hassan, M. Pharmacokinetic Profile of N-Acetylcysteine Amide and Its Main Metabolite in Mice Using New Analytical Method. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 143, 105158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Possamai, F.P.; Fortunato, J.J.; Feier, G.; Agostinho, F.R.; Quevedo, J.; Wilhelm Filho, D.; Dal-Pizzol, F. Oxidative Stress after Acute and Sub-Chronic Malathion Intoxication in Wistar Rats. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2007, 23, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maupu, C.; Enderlin, J.; Igert, A.; Oger, M.; Auvin, S.; Hassan-Abdi, R.; Soussi-Yanicostas, N.; Brazzolotto, X.; Nachon, F.; Dal Bo, G.; et al. Diisopropylfluorophosphate-Induced Status Epilepticus Drives Complex Glial Cell Phenotypes in Adult Male Mice. Neurobiol. Dis. 2021, 152, 105276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piel, S.; Janowska, J.I.; Ward, J.L.; McManus, M.J.; Jose, J.S.; Starr, J.; Sheldon, M.; Clayman, C.L.; Elmér, E.; Hansson, M.J.; et al. Succinate Prodrugs in Combination with Atropine and Pralidoxime Protect Cerebral Mitochondrial Function in a Rodent Model of Acute Organophosphate Poisoning. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 20329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Naim, A.B.; Hassanein, E.H.M.; Binmahfouz, L.S.; Bagher, A.M.; Hareeri, R.H.; Algandaby, M.M.; Fadladdin, Y.A.J.; Aleya, L.; Abdel-Daim, M.M. Lycopene Attenuates Chlorpyrifos-Induced Hepatotoxicity in Rats via Activation of Nrf2/HO-1 Axis. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 262, 115122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, L.S.; Phillips, K.; Huang, B.; DeLorenzo, R.J. Chronic Behavioral and Cognitive Deficits in a Rat Survival Model of Paraoxon Toxicity. Neurotoxicology 2014, 44, 352–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouardi, F.Z.; Anarghou, H.; Malqui, H.; Ouasmi, N.; Chigr, M.; Najimi, M.; Chigr, F. Gestational and Lactational Exposure to Malathion Affects Antioxidant Status and Neurobehavior in Mice Pups and Offspring. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2019, 69, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubos, E.; Loscalzo, J.; Handy, D.E. Glutathione Peroxidase-1 in Health and Disease: From Molecular Mechanisms to Therapeutic Opportunities. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2011, 15, 1957–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, T.; Li, J.; Xia, M.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Liu, C.; Zheng, T.; Chen, R.; Kan, D.; et al. Oxidative Stress and 4-Hydroxy-2-Nonenal (4-HNE): Implications in the Pathogenesis and Treatment of Aging-Related Diseases. J. Immunol. Res. 2022, 2022, 2233906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurumez, Y.; Cemek, M.; Yavuz, Y.; Osman Birdane, Y.; Emin Buyukokuroglu, M. Beneficial Effect of N-Acetylcysteine against Organophosphate Toxicity in Mice. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2007, 30, 490–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shri, P.; Singh, K.P.; Rani, V.; Nagar, D.P.; Acharya, J.; Bhaskar, A.S.B. N-Acetylcysteine Prevents Cholinergic and Non-Cholinergic Toxic Effects Induced by Nerve Agent Poisoning in Rats. Toxicol. Res. 2025, 14, tfae223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brocardo, P.S.; Pandolfo, P.; Takahashi, R.N.; Rodrigues, A.L.S.; Dafre, A.L. Antioxidant Defenses and Lipid Peroxidation in the Cerebral Cortex and Hippocampus Following Acute Exposure to Malathion and/or Zinc Chloride. Toxicology 2005, 207, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staal, F.J.T.; Roederer, M.; Herzenberg, L.A.; Herzenberg, L.A. Intracellular Thiols Regulate Activation of Nuclear Factor KCB and Transcription of Human Immunodeficiency Virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1990, 87, 9943–9947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valencia, A.; Morán, J. Reactive Oxygen Species Induce Different Cell Death Mechanisms in Cultured Neurons. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2004, 36, 1112–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Armenta, M.; Nava-Ruíz, C.; Juárez-Rebollar, D.; Rodríguez-Martínez, E.; Yescas Gómez, P. Oxidative Stress Associated with Neuronal Apoptosis in Experimental Models of Epilepsy. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2014, 2014, 293689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aroniadou-Anderjaska, V.; Figueiredo, T.H.; de Araujo Furtado, M.; Pidoplichko, V.I.; Braga, M.F.M. Mechanisms of Organophosphate Toxicity and the Role of Acetylcholinesterase Inhibition. Toxics 2023, 11, 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorke, D.E.; Oz, M. A Review on Oxidative Stress in Organophosphate-Induced Neurotoxicity. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2025, 180, 106735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guignet, M.; Dhakal, K.; Flannery, B.M.; Hobson, B.A.; Zolkowska, D.; Dhir, A.; Bruun, D.A.; Li, S.; Wahab, A.; Harvey, D.J.; et al. Persistent Behavior Deficits, Neuroinflammation, and Oxidative Stress in a Rat Model of Acute Organophosphate Intoxication. Neurobiol. Dis. 2020, 133, 104431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freidin, D.; Har-Even, M.; Rubovitch, V.; Murray, K.E.; Maggio, N.; Shavit-Stein, E.; Keidan, L.; Citron, B.A.; Pick, C.G. Cognitive and Cellular Effects of Combined Organophosphate Toxicity and Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, S.; Kadar, T.; Gilat, E. Seizure Duration Following Sarin Exposure Affects Neuro-Inflammatory Markers in the Rat Brain. Neurotoxicology 2006, 27, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboubakr, M.; Elshafae, S.M.; Abdelhiee, E.Y.; Fadl, S.E.; Soliman, A.; Abdelkader, A.; Abdel-Daim, M.M.; Bayoumi, K.A.; Baty, R.S.; Elgendy, E.; et al. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Potential of Thymoquinone and Lycopene Mitigate the Chlorpyrifos-Induced Toxic Neuropathy. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birdane, Y.O.; Avci, G.; Birdane, F.M.; Turkmen, R.; Atik, O.; Atik, H. The Protective Effects of Erdosteine on Subacute Diazinon-Induced Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Rats. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 21537–21546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.P.; Pearson-Smith, J.N.; Huang, J.; Day, B.J.; Patel, M. Neuroprotective Effects of a Catalytic Antioxidant in a Rat Nerve Agent Model. Redox Biol. 2019, 20, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, M.; Gage, M.; Sharma, S.; Gardner, C.; Gasser, G.; Anantharam, V.; Thippeswamy, T. Diapocynin, an NADPH Oxidase Inhibitor, Counteracts Diisopropylfluorophosphate-Induced Long-Term Neurotoxicity in the Rat Model. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2020, 1479, 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesseling, C.; Keifer, M.; Ahlbom, A.; Mcconnell, R.; Moon, J.-D.; Rosenstock, L. Long-Term Neurobehavioral Effects of Mild Poisonings with Organophosphate and n-Methyl Carbamate Pesticides among Banana Workers. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Health 2002, 8, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odegard, T.N.; Cooper, C.M.; Farris, E.A.; Arduengo, J.; Bartlett, J.; Haley, R. Memory Impairment Exhibited by Veterans with Gulf War Illness. Neurocase 2013, 19, 316–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Toxicology Program. NTP Monograph on the Systematic Review of Long-Term Neurological Effects Following Acute Exposure to Sarin, 6th ed.; Research Triangle Park: Durham, NC, USA, 2019.

- Honatel, K.F.; Arbo, B.D.; Leal, M.B.; da Silva Júnior, F.M.R.; Garcia, S.C.; Arbo, M.D. An Update of the Impact of Pesticide Exposure on Memory and Learning. Discov. Toxicol. 2024, 1, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, C.M.; Burgess, N. The Hippocampus and Memory: Insights from Spatial Processing. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2008, 9, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baratz-Goldstein, R.; Deselms, H.; Heim, L.R.; Khomski, L.; Hoffer, B.J.; Atlas, D.; Pick, C.G. Thioredoxin-Mimetic-Peptides Protect Cognitive Function after Mild Traumatic Brain Injury (MTBI). PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0157064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iha, H.A.; Kunisawa, N.; Shimizu, S.; Onishi, M.; Nomura, Y.; Matsubara, N.; Iwai, C.; Ogawa, M.; Hashimura, M.; Sato, K.; et al. Mechanism Underlying Organophosphate Paraoxon-Induced Kinetic Tremor. Neurotox. Res. 2019, 35, 575–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehrani, H.; Asadi, B.; Golmanesh, L. Protective Effects of Mecamylamine and Atropine against A4β2 Nicotinic Receptor Expression and Functional Toxicity in Paraoxon-Treated Rats. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2008, 26, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izquierdo, P.G.; Charvet, C.L.; Neveu, C.; Green, A.C.; Tattersall, J.E.H.; Holden-Dye, L.; O’Connor, V. Modelling Organophosphate Intoxication in C. Elegans Highlights Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Determinants That Mitigate Poisoning. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0284786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Urquizu, E.; Cuiller, M.; Papadopoulou, G.; Pubill, D.; Raldúa, D.; Camarasa, J.; Escubedo, E.; López-Arnau, R. Neuroprotective Effects of N-Acetylcysteine-Amide (AD4) in a Survival Mouse Model of Paraoxon Intoxication: Targeting Oxidative Stress, Neuroinflammation and Memory Impairments. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 1463. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121463

Urquizu E, Cuiller M, Papadopoulou G, Pubill D, Raldúa D, Camarasa J, Escubedo E, López-Arnau R. Neuroprotective Effects of N-Acetylcysteine-Amide (AD4) in a Survival Mouse Model of Paraoxon Intoxication: Targeting Oxidative Stress, Neuroinflammation and Memory Impairments. Antioxidants. 2025; 14(12):1463. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121463

Chicago/Turabian StyleUrquizu, Edurne, Marine Cuiller, Georgia Papadopoulou, David Pubill, Demetrio Raldúa, Jordi Camarasa, Elena Escubedo, and Raul López-Arnau. 2025. "Neuroprotective Effects of N-Acetylcysteine-Amide (AD4) in a Survival Mouse Model of Paraoxon Intoxication: Targeting Oxidative Stress, Neuroinflammation and Memory Impairments" Antioxidants 14, no. 12: 1463. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121463

APA StyleUrquizu, E., Cuiller, M., Papadopoulou, G., Pubill, D., Raldúa, D., Camarasa, J., Escubedo, E., & López-Arnau, R. (2025). Neuroprotective Effects of N-Acetylcysteine-Amide (AD4) in a Survival Mouse Model of Paraoxon Intoxication: Targeting Oxidative Stress, Neuroinflammation and Memory Impairments. Antioxidants, 14(12), 1463. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121463