Dynamic Characterization of Antioxidant-Related, Non-Volatile, and Volatile Metabolite Profiles of Cherry Tomato During Ripening

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

2.2. Measurement of Quality Indicators

2.3. UPLC-MS/MS Analysis

2.3.1. Dry Sample Extraction

2.3.2. UPLC Conditions

2.3.3. ESI-Q TRAP-MS/MS

2.4. GC-MS Analysis

2.4.1. Solid/Liquid Samples Class II

2.4.2. GC-MS Conditions

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Effects of Ripe Stages on Nutritional Quality of Cherry Tomato Fruits

3.2. Effects of Different Ripe Stages on Non-Volatile Substances in Tomato Fruits

3.2.1. Comparative Analysis of the Composition and Content of Primary Metabolic Products in Tomato Fruits at Different Ripe Stages

3.2.2. The Influence of Different Maturity Stages on the Composition and Content of Primary Metabolites in Tomato Fruits

3.2.3. Phenolic Acids

3.2.4. Flavonoids

3.2.5. Alkaloids

3.2.6. Lipids

3.2.7. Amino-Acids and Derivatives

3.3. Effects of Different Ripe Stages on Volatile Substances in Tomato Fruits

3.3.1. Comparative Analysis of the Composition and Content of Volatile Substances in Tomato Fruits at Different Ripe Stages

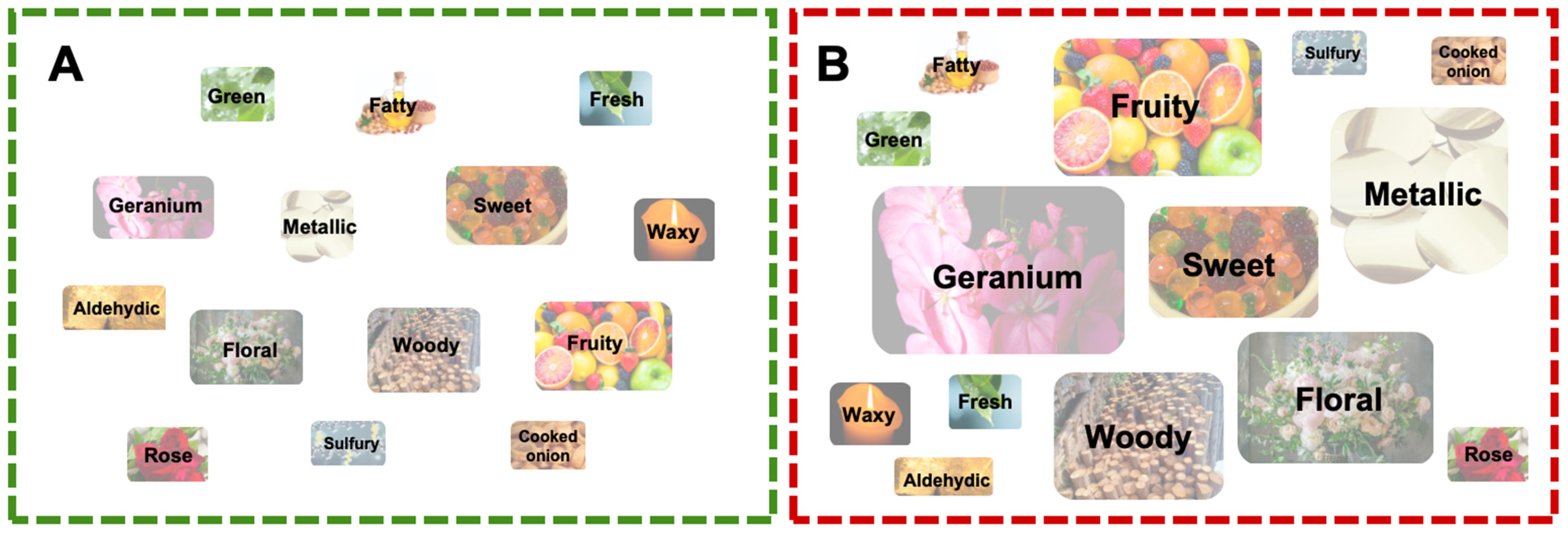

3.3.2. The Influence of Different Maturity Stages on the Key Aroma-Active Compounds in Tomato Fruits

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tieman, D.; Zhu, G.; Resende, M.F., Jr.; Lin, T.; Nguyen, C.; Bies, D.; Rambla, J.L.; Beltran, K.S.; Taylor, M.; Zhang, B.; et al. A chemical genetic roadmap to improved tomato flavor. Science 2017, 355, 391–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razifard, H.; Ramos, A.; Della Valle, A.L.; Bodary, C.; Goetz, E.; Manser, E.J.; Li, X.; Zhang, L.; Visa, S.; Tieman, D.; et al. Genomic Evidence for Complex Domestication History of the Cultivated Tomato in Latin America. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2020, 37, 1118–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Wang, S.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, S.; Liao, Q.; Zhang, C.; Lin, T.; Qin, M.; Peng, M.; Yang, C.; et al. Rewiring of the Fruit Metabolome in Tomato Breeding. Cell 2018, 172, 249–261.e212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, G.; Chang, P.; Shen, Y.; Wu, L.; El-Sappah, A.H.; Zhang, F.; Liang, Y. Comparing the Flavor Characteristics of 71 Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) Accessions in Central Shaanxi. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 586834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amr, A.; Raie, W. Tomato Components and Quality Parameters. A Review. Jordan. J. Agric. Sci. 2022, 18, 199–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Li, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, H.; Guo, F.; Wang, Y.; Wang, P.; Chen, Y.; Ni, D.; et al. Metabolome and RNA-seq Analysis of Responses to Nitrogen Deprivation and Resupply in Tea Plant (Camellia sinensis) Roots. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 932720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, J.; Morikawa-Ichinose, T.; Fujimura, Y.; Hayakawa, E.; Takahashi, K.; Ishii, T.; Miura, D.; Wariishi, H. Spatially resolved metabolic distribution for unraveling the physiological change and responses in tomato fruit using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-mass spectrometry imaging (MALDI-MSI). Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2017, 409, 1697–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pott, D.M.; Osorio, S.; Vallarino, J.G. From Central to Specialized Metabolism: An Overview of Some Secondary Compounds Derived From the Primary Metabolism for Their Role in Conferring Nutritional and Organoleptic Characteristics to Fruit. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, E.A.; Scott, J.W.; Shewmaker, C.K.; Schuch, W. Flavor Trivia and Tomato Aroma: Biochemistry and Possible Mechanisms for Control of Important Aroma Components. HortScience 2000, 35, 1013–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tieman, D.; Bliss, P.; McIntyre, L.M.; Blandon-Ubeda, A.; Bies, D.; Odabasi, A.Z.; Rodriguez, G.R.; van der Knaap, E.; Taylor, M.G.; Goulet, C.; et al. The chemical interactions underlying tomato flavor preferences. Curr. Biol. 2012, 22, 1035–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinet, M.; Angosto, T.; Yuste-Lisbona, F.J.; Blanchard-Gros, R.; Bigot, S.; Martinez, J.P.; Lutts, S. Tomato Fruit Development and Metabolism. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, G.; Abugu, M.; Tieman, D. The dissection of tomato flavor: Biochemistry, genetics, and omics. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1144113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Moreno, C.; Plaza, L.; de Ancos, B.; Cano, M.P. Nutritional characterisation of commercial traditional pasteurised tomato juices: Carotenoids, vitamin C and radical-scavenging capacity. Food Chem. 2006, 98, 749–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, D.; He, J.J.; Zhou, Y.Z.; Li, Y.L.; Zhou, H.J. Aroma effects of key volatile compounds in Keemun black tea at different grades: HS-SPME-GC-MS, sensory evaluation, and chemometrics. Food Chem. 2022, 373, 131587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, J.; Li, Y.; Yang, Z.; Lin, Z.; Chen, F.; Liu, S.; Li, C. Effect of different cooking times on the fat flavor compounds of pork belly. J. Food Biochem. 2022, 46, e14184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.; Fang, S.; Wang, J.; Zhuo, C.; Luo, Y.; Yu, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, Y.; Deng, W.W.; Ning, J. Sensomics analysis of the effect of the withering method on the aroma components of Keemun black tea. Food Chem. 2022, 395, 133549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, J.; Liu, P.; Yin, J.; Wang, W.; Zhang, J.; Wang, W.; Le, T.; Ni, D.; Jiang, H. Dynamic Changes in Volatile Compounds of Shaken Black Tea during Its Manufacture by GC x GC-TOFMS and Multivariate Data Analysis. Foods 2022, 11, 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Zheng, M.; Yu, S.; Gao, Y.; Zhu, G.; Zhu, J.K.; Hua, K.; Wang, Z. A natural variation contributes to sugar accumulation in fruit during tomato domestication. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2024, 22, 3520–3522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Chen, H.; Wu, M.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, C.; Yang, Q.; Rolland, F.; Van de Poel, B.; Bouzayen, M.; Hu, N.; et al. A vacuolar invertase gene SlVI modulates sugar metabolism and postharvest fruit quality and stress resistance in tomato. Hortic. Res. 2025, 12, uhae283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takayama, M.; Ezura, H. How and why does tomato accumulate a large amount of GABA in the fruit? Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snowden, C.J.; Thomas, B.; Baxter, C.J.; Smith, J.A.; Sweetlove, L.J. A tonoplast Glu/Asp/GABA exchanger that affects tomato fruit amino acid composition. Plant J. 2015, 81, 651–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akihiro, T.; Koike, S.; Tani, R.; Tominaga, T.; Watanabe, S.; Iijima, Y.; Aoki, K.; Shibata, D.; Ashihara, H.; Matsukura, C.; et al. Biochemical mechanism on GABA accumulation during fruit development in tomato. Plant Cell Physiol. 2008, 49, 1378–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalal, A.; Rana, J.S.; Kumar, A. Ultrasensitive Nanosensor for Detection of Malic Acid in Tomato as Fruit Ripening Indicator. Food Anal. Methods 2017, 10, 3680–3686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Wen, W.; Cheng, Y.; Fernie, A.R. The metabolic changes that effect fruit quality during tomato fruit ripening. Mol. Hortic. 2022, 2, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saini, R.K.; Zamany, A.J.; Keum, Y.S. Ripening improves the content of carotenoid, alpha-tocopherol, and polyunsaturated fatty acids in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) fruits. 3 Biotech 2017, 7, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferraro, G.; D’Angelo, M.; Sulpice, R.; Stitt, M.; Valle, E.M. Reduced levels of NADH-dependent glutamate dehydrogenase decrease the glutamate content of ripe tomato fruit but have no effect on green fruit or leaves. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 3381–3389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Qin, L. The cause of germination increases the phenolic compound contents of Tartary buckwheat (Fagopyrum tataricum). J. Future Foods 2022, 2, 372–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Pan, X.; Jiang, L.; Chu, Y.; Gao, S.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Luo, S.; Peng, C. The Biological Activity Mechanism of Chlorogenic Acid and Its Applications in Food Industry: A Review. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 943911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.; Taine, E.G.; Meng, D.; Cui, T.; Tan, W. Chlorogenic Acid: A Systematic Review on the Biological Functions, Mechanistic Actions, and Therapeutic Potentials. Nutrients 2024, 16, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, M.A.; de Jager, A.; van Westing, L.M. Flavonoid and chlorogenic acid levels in apple fruit: Characterisation of variation. Sci. Hortic. 2000, 83, 249–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.H.; Hung, T.W.; Wang, C.C.; Wu, S.W.; Yang, T.W.; Yang, C.Y.; Tseng, T.H.; Wang, C.J. Neochlorogenic Acid Attenuates Hepatic Lipid Accumulation and Inflammation via Regulating miR-34a In Vitro. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 13163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhai, Y.; Wu, Z.; Wang, C.; Zhang, J. Dynamic characterization of volatile and non-volatile profiles during Toona sinensis microgreens growth in combination with chemometrics. Food Res. Int. 2025, 206, 116013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabavi, S.M.; Samec, D.; Tomczyk, M.; Milella, L.; Russo, D.; Habtemariam, S.; Suntar, I.; Rastrelli, L.; Daglia, M.; Xiao, J.; et al. Flavonoid biosynthetic pathways in plants: Versatile targets for metabolic engineering. Biotechnol. Adv. 2020, 38, 107316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Salehi, B.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; Aslam Gondal, T.; Saeed, F.; Imran, A.; Shahbaz, M.; Tsouh Fokou, P.V.; Umair Arshad, M.; Khan, H.; et al. Kaempferol: A Key Emphasis to Its Anticancer Potential. Molecules 2019, 24, 2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, D.; Hu, M.J.; Wang, Y.Q.; Cui, Y.L. Antioxidant Activities of Quercetin and Its Complexes for Medicinal Application. Molecules 2019, 24, 1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Hu, H.; Yang, R.; Zhu, Z.; Cheng, K. Current Advances in the Biosynthesis, Metabolism, and Transcriptional Regulation of alpha-Tomatine in Tomato. Plants 2023, 12, 3289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngo, T.H.; Park, J.; Jo, Y.D.; Jin, C.H.; Jung, C.H.; Nam, B.; Han, A.R.; Nam, J.W. Content of Two Major Steroidal Glycoalkaloids in Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum cv. Micro-Tom) Mutant Lines at Different Ripening Stages. Plants 2022, 11, 2895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozukue, N.; Kim, D.S.; Choi, S.H.; Mizuno, M.; Friedman, M. Isomers of the Tomato Glycoalkaloids alpha-Tomatine and Dehydrotomatine: Relationship to Health Benefits. Molecules 2023, 28, 3621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardenas, P.D.; Sonawane, P.D.; Heinig, U.; Jozwiak, A.; Panda, S.; Abebie, B.; Kazachkova, Y.; Pliner, M.; Unger, T.; Wolf, D.; et al. Pathways to defense metabolites and evading fruit bitterness in genus Solanum evolved through 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.; van Kan, J.A.L. Bitter and sweet make tomato hard to (b)eat. New Phytol. 2021, 230, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chapman, K.D. Lipid signaling in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2013, 4, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li-Beisson, Y.; Shorrosh, B.; Beisson, F.; Andersson, M.X.; Arondel, V.; Bates, P.D.; Baud, S.; Bird, D.; Debono, A.; Durrett, T.P.; et al. Acyl-lipid metabolism. Arab. Book 2013, 11, e0161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, A.; De Vadder, F.; Kovatcheva-Datchary, P.; Backhed, F. From Dietary Fiber to Host Physiology: Short-Chain Fatty Acids as Key Bacterial Metabolites. Cell 2016, 165, 1332–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volz, R.; Park, J.Y.; Harris, W.; Hwang, S.; Lee, Y.H. Lyso-phosphatidylethanolamine primes the plant immune system and promotes basal resistance against hemibiotrophic pathogens. BMC Biotechnol. 2021, 21, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouet-Mayer, M.A.; Valentova, O.; Simond-Cote, E.; Daussant, J.; Thevenot, C. Critical analysis of phospholipid hydrolyzing activities in ripening tomato fruits. Study by spectrofluorimetry and high-performance liquid chromatography. Lipids 1995, 30, 739–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitaker, B.D. Lipid Changes in Mature-green Tomatoes during Ripening, during Chilling, and after Rewarming subsequent to Chilling. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 1994, 119, 994–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudareva, N.; Klempien, A.; Muhlemann, J.K.; Kaplan, I. Biosynthesis, function and metabolic engineering of plant volatile organic compounds. New Phytol. 2013, 198, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaky, A.A.; Simal-Gandara, J.; Eun, J.B.; Shim, J.H.; Abd El-Aty, A.M. Bioactivities, Applications, Safety, and Health Benefits of Bioactive Peptides From Food and By-Products: A Review. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 815640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schagen, S. Topical Peptide Treatments with Effective Anti-Aging Results. Cosmetics 2017, 4, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oms-Oliu, G.; Hertog, M.L.A.T.M.; Van de Poel, B.; Ampofo-Asiama, J.; Geeraerd, A.H.; Nicolaï, B.M. Metabolic characterization of tomato fruit during preharvest development, ripening, and postharvest shelf-life. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2011, 62, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biais, B.; Benard, C.; Beauvoit, B.; Colombie, S.; Prodhomme, D.; Menard, G.; Bernillon, S.; Gehl, B.; Gautier, H.; Ballias, P.; et al. Remarkable reproducibility of enzyme activity profiles in tomato fruits grown under contrasting environments provides a roadmap for studies of fruit metabolism. Plant Physiol. 2014, 164, 1204–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffo, A.; Masci, M.; Moneta, E.; Nicoli, S.; Sanchez Del Pulgar, J.; Paoletti, F. Characterization of volatiles and identification of odor-active compounds of rocket leaves. Food Chem. 2018, 240, 1161–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikunov, Y.; Lommen, A.; de Vos, C.H.; Verhoeven, H.A.; Bino, R.J.; Hall, R.D.; Bovy, A.G. A novel approach for nontargeted data analysis for metabolomics. Large-scale profiling of tomato fruit volatiles. Plant Physiol. 2005, 139, 1125–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewinsohn, E.; Sitrit, Y.; Bar, E.; Azulay, Y.; Meir, A.; Zamir, D.; Tadmor, Y. Carotenoid pigmentation affects the volatile composition of tomato and watermelon fruits, as revealed by comparative genetic analyses. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 3142–3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; He, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, D. Analyzing Volatile Compounds of Young and Mature Docynia delavayi Fruit by HS-SPME-GC-MS and rOAV. Foods 2022, 12, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aloum, L.; Alefishat, E.; Adem, A.; Petroianu, G. Ionone Is More than a Violet’s Fragrance: A Review. Molecules 2020, 25, 5822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Amino Acid | GRS (mg/g) | RRS (mg/g) |

|---|---|---|

| Aspartic acid (Asp) | 0.887 ± 133 b | 2.171 ± 0.220 a |

| Glutamic acid (Glu) | 1.191± 0.191 b | 11.619 ±0.924 a |

| Threonine (Thr) | 7.113 ± 2.151 a | 5.090 ± 0.647 a |

| Valine (Val) | 0.176 ± 0.038 a | 0.103 ± 0.004 b |

| Tyrosine (Tyr) | 0.178 ± 0.049 a | 0.143 ± 0.003 a |

| Isoleucine (Ile) | 0.203 ± 0.035 a | 0.121 ± 0.003 b |

| Leucine (Leu) | 0.185 ± 0.023 a | 0.217 ± 0.010 a |

| Arginine (Arg) | 0.208 ± 0.059 b | 0.331 ± 0.028 a |

| Cysteine (Cys) | 0.124 ± 0.002 a | 0.127 ± 0.001 a |

| Lysine (Lys) | 0.234 ± 0.053 a | 0.296 ± 0.018 a |

| Alanine (Ala) | 0.222 ± 0.042 b | 0.479 ± 0.032 a |

| Histidine (His) | 0.176 ± 0.037 b | 0.314 ± 0.020 a |

| Proline (Pro) | 0.062 ± 0.011 b | 0.157 ± 0.001 a |

| Methionine (Met) | 0.031 ± 0.011 b | 0.064 ± 0.011 a |

| Serine (Ser) | 4.895 ± 1.150 b | 6.034± 0.443 a |

| Glycine (Gly) | 0.101 ± 0.004 a | 0.103 ± 0.014 a |

| Phenylalanine (Phe) | 0.565 ± 0.147 a | 0.638 ± 0.069 a |

| Total | 16.551 ± 4.083 b | 28.006 ± 2.302 a |

| CAS | Compounds | Class | Odor | Threshold | ROAV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GRS | RRS | |||||

| 65767-22-8 | (5Z)-Octa-1,5-dien-3-one | Ketone | geranium, metallic | 0.000003 | 11.91 | 100 |

| 14901-07-6 | β-Ionone | Terpenoids | floral, woody, sweet, fruity | 0.000007 | 10.85 | 51.5 |

| 18829-56-6 | 2-Nonenal, (E)- | Aldehyde | fatty, green, fresh, aldehydic, fruity | 0.00008 | 2.13 | 1.65 |

| 2463-53-8 | 2-Nonenal | Aldehyde | fatty, green, waxy, fresh, fruity | 0.0001 | 1.71 | 1.32 |

| 5870-68-8 | Pentanoic acid, 3-methyl-, ethyl ester | Ester | fruity | 0.000008 | 1.41 | 1.30 |

| 140-26-1 | Butanoic acid, 3-methyl-, 2-phenylethyl ester | Ester | floral, fruity, sweet, rose | 0.00001 | 0.82 | 1.19 |

| 3658-80-8 | Dimethyl trisulfide | Sulfur compounds | sulfury, cooked onion, fatty | 0.000008 | 0.53 | 1.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, Z.; Guan, S.; Wang, R.; Ruan, M.; Ye, Q.; Yao, Z.; Liu, C.; Wan, H.; Zhou, G.; Cheng, Y. Dynamic Characterization of Antioxidant-Related, Non-Volatile, and Volatile Metabolite Profiles of Cherry Tomato During Ripening. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 1359. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14111359

Li Z, Guan S, Wang R, Ruan M, Ye Q, Yao Z, Liu C, Wan H, Zhou G, Cheng Y. Dynamic Characterization of Antioxidant-Related, Non-Volatile, and Volatile Metabolite Profiles of Cherry Tomato During Ripening. Antioxidants. 2025; 14(11):1359. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14111359

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Zhimiao, Sihui Guan, Rongqing Wang, Meiying Ruan, Qingjing Ye, Zhuping Yao, Chenxu Liu, Hongjian Wan, Guozhi Zhou, and Yuan Cheng. 2025. "Dynamic Characterization of Antioxidant-Related, Non-Volatile, and Volatile Metabolite Profiles of Cherry Tomato During Ripening" Antioxidants 14, no. 11: 1359. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14111359

APA StyleLi, Z., Guan, S., Wang, R., Ruan, M., Ye, Q., Yao, Z., Liu, C., Wan, H., Zhou, G., & Cheng, Y. (2025). Dynamic Characterization of Antioxidant-Related, Non-Volatile, and Volatile Metabolite Profiles of Cherry Tomato During Ripening. Antioxidants, 14(11), 1359. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14111359