Featured Application

A proteolytic fermentation broth was applied to leather tanning and protein stain removal showing its potential use in the leather and detergent industries, or even in the treatment of industrial proteinaceous wastes and/or effluents. The microbial proteolytic broth applications exemplify the cross-sectoral benefits and environmental responsibility at the heart of the bioeconomy. Microbial enzyme applications in leather processing, stain removal, and waste and effluent management demonstrate how microbial biotechnology can replace polluting industrial practices, thereby becoming a catalyst for sustainable growth, innovation, and climate resilience.

Abstract

Microbial proteases are fundamental towards the eco-sustainability of proteolysis at the industrial scale. A proteolytic broth was obtained from a bioreactor fermentation of a proteolytic Bacillus strain isolated from an industrial alkaline bath. Broth proteolytic activity was applied to leather tanning and to the removal of protein stains. The hide tanned with the microbial proteolytic fermentation broth showed better physical properties than the one tanned with commercial pancreatic proteases of the same activity (780 LVU). Proteinaceous stains on cotton fabric were removed more efficiently using the Bacillus proteolytic broth than water or a commercial detergent. Blood and egg yolk disappeared in less than 30 min. The removal of soya and English sauce stains was even faster. Broth proteolytic activity was characterised by caseinolytic (5200 LVU), collagenolytic (10.0 U mg−1), elastolytic (3.7 U mg−1), and keratinolytic (0.7 U mg−1) activities, which were compared with those of a commonly used commercial protease. Alkaline protease activity in the broth was demonstrated by a 20% increase in caseinolytic activity from pH 5 to 8. Besides the demonstrated applications in the leather and detergent industries, the produced alkaline microbial proteases can also be used in the treatment of proteinaceous wastes and effluents, offering potential environmental benefits reinforcing and impacting the bioeconomy.

1. Introduction

Proteases are ubiquitous in all living beings, including those from the vegetal, animal, and microbial kingdoms [1,2]. Proteases are enzymes belonging to the hydrolytic enzyme class that catalyse the transformation of proteins into peptides and amino acids [3,4,5]. The Enzyme Commission classification placed proteases in class 3 (hydrolases), sub-class 4 (proteases), and assigned each proteolytic enzyme a unique Enzyme Commission number [6,7,8]. Proteases were classified by their catalytic action (the active site composition) in serine proteases EC 3.4.21 (subtilisin EC 3.4.21.62 and chymotrypsin EC 3.4.21.1), cysteine proteases EC 3.4.22 (papain EC 3.4.22.1), aspartic proteases EC 3.4.23 (renin EC 3.4.23.1), metalloproteases (EC 3.4.24), and threonine proteases (EC 3.4.25) [9]. Proteases can also be classified according to their pH working range (acid, neutral, or alkaline proteases), molecular weight, or substrate specificity.

The use of microbial proteases makes the industry more eco-sustainable, both by reducing the consumption of chemical products and by lowering waste and effluent treatment costs through their applicability and specificity [10]. Microbial proteases account for 60% of the global enzyme market sales, and Bacillus species are the most representative sources [11,12]. Among these industrial proteases, 35% are alkaline proteases [3]. Alkaline microbial proteases are active at high pH levels, ranging from 7 to 13, and due to their specificity are utilised in various industrial processes [13,14], such as leather manufacturing [7,15] or the detergent industry [7,16].

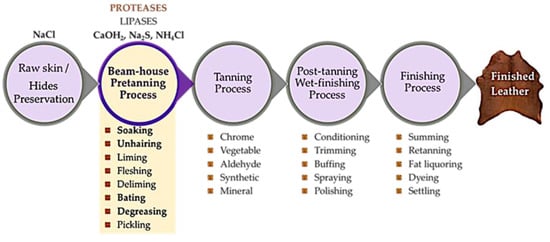

The tanning industry is highly traditional and has a negative environmental impact, but is crucial to the economy [17,18]. The industrial process of converting raw skin or hides into finished leather consumes significant amounts of chemicals, water, and energy through a complex technological process that involves both doing and undoing operations [7,19], making it highly polluting. Figure 1 illustrates the sequence of operations from raw hides to finished leather, emphasising the pre-tanning beam-house operations where proteases and lipases are applied. In addition to protease application in the pre-tanning beam-house operations (such as soaking rehydration, unhairing, bating, degreasing, and pickling), protease can also be used in chrome tanning and post-tanning operations [20].

Figure 1.

The operation sequence, from raw putrescible hides to finished leather (non-putrescible), highlights the main protease application steps in the beam-house pre-tanning process. The different possible tanning processes (chrome, vegetable, aldehyde, synthetic, or mineral) and several post-tanning wet-finishing and finishing processing steps are also identified.

The traditional tanning of one ton of raw hides results in 200 to 250 kg of finished leather [8], with a yield of only 20–25% in the transformation from raw hides into strong, non-putrescible finished leather, and resulting in the disposal of almost 80% of raw material in solid and liquid wastes during the leather-making process [21]. The traditional process utilises 500 kg of chemical products, consuming 15 to 50 m3 of water and 9.3 to 42 GJ of energy, resulting in 15 to 50 m3 of liquid effluents, 450 to 739 kg of solid waste, and 40 kg of organic solvent emissions [22].

This scenario can be changed for a more sustainable tanning industry by using enzymes instead of polluting chemical products and by replacing conventional, faster, cheaper, but highly polluting chrome tanning (wet blue leather) [20] with viable chrome substitutes. Alternative tanning processes using chrome substitutes include vegetable (green leather) [23], aldehyde (wet white leather) [24], synthetic [20], and mineral tanning [23].

European Union regulations restrict the use of hazardous substances that generate significant amounts of corrosive wastewater, aiming to reduce the environmental impact of tanneries by implementing combined enzymatic technologies [25]. In fact, enzymatic tanning requires less water and generates less waste than chrome tanning, selectively breaking down the collagen fibres, resulting in a uniform, softer, and more flexible leather product [25].

Protease application during the tanning process reduces chemical usage by 50%, lowering effluent chemical oxygen demand (COD), biological oxygen demand (BOD), and sulphide content, and thereby improving sustainability [22].

Despite the availability of new bacterial and fungal enzymes, pancreatic bating agents continue to dominate the market because they offer a cheap, balanced mixture of different proteases with a high lipase content [7].

The application of alkaline protease during soaking can accelerate hide rehydration by removing blood, dirt, grease, and proteoglycans. Protease application during unhairing can reduce COD, BOD, and sulphide content in the final effluents, thereby improving wastewater treatment efficiency and reducing chemical use. This approach also provides smoother grain, increases leather softness, and enhances the possibility of a higher area recovery and hair recovery [18,22]. Proteases are used as auxiliaries during liming to accelerate the processing. However, the bating step relies entirely on proteolytic enzymes [18] to digest the non-structural proteins, ensuring collagen integrity, cleaning up the interfibrillar region, improving grain openness and texture [26], and preparing the leather for uniform dye penetration and tanning.

Lipases can be used in degreasing to break down natural grease into partially self-emulsifying soaps, thereby reducing or eliminating the need for non-biodegradable surfactants, such as alkylphenol ethoxylates [19].

All enzymes must be active under industrial operating conditions over a temperature range of 25 °C to 35 °C and at alkaline pH [27] to be applied in the leather industry.

Protease assays can be divided [28] into (a) homogeneous assays (not needing separation of product and/or substrate from the reaction mixture, relying on the physical change along substrate turnover, usually detecting a colourimetric or fluorescent signal) and (b) separation-based assays, in which the product and substrate are separated before analysis. Fluorescent assays are more precise than colourimetric assays. Separation-based assays based on labelled peptides offer significant advantages: they are suitable for extensive library screening and can enable a kinetic analysis of the enzymatic reaction. Greenfield et al. (2021) critically evaluate the most common colourimetric and fluorimetric methods used for measuring protease activity [29].

The first enzyme-based detergent was delivered in 1913 (company Röhm and Haas, Esslingen, Germany) under the trade name Burnus, containing a crude protease extract from animal pancreas, and was used to break down protein-based stains, such as blood, sweat, and food residues [7]. Burnus marked the first practical use of enzymes in laundry detergents, representing an important milestone in enzyme technology and cleaning solutions. However, the pancreatic proteases were unstable at high temperatures and in the alkaline conditions typically encountered in laundry processes, which limited their performance and durability [9].

Since then, proteases have been extensively applied in detergent preparation, enhancing detergent efficiency, particularly in low-temperature washing, aligning with energy-saving and eco-friendly trends. Nearly 25–30% of the commercial enzymes are the key ingredients in detergent manufacturing [9]. The development of stabilised protease formulations ensures compatibility with several detergent components and conditions. Novozymes (Bagsværd, Denmark) is considered the largest and most dominant producer and supplier of proteases to the detergent industry due to its advanced technology, global market reach, and innovation in sustainable solutions.

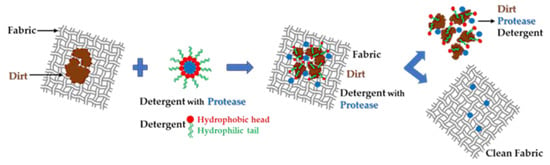

Figure 2 illustrates the action steps for stain removal from fabric by a protease-embedded detergent [7] agglomerate, from dirty to clean fabric.

Figure 2.

Action steps of the detergent with protease to remove dirt from the fabric.

Herein is described a new proteolytic microbial broth that was applied for leather tanning and for the removal of protein stains from cotton. The protease broth was produced through submerged fermentation in a bioreactor using a Bacillus strain previously isolated from a Portuguese tannery’s alkaline bath [30]. The cell-free fermentation broth’s enzymatic activities were assessed for their caseinolytic, collagenolytic, keratinolytic, and elastolytic activities. Also, its industrial proteolytic activity (Löhlein–Volhard Unit) was determined and compared with that of a commercial pancreatic protease cocktail. The leather tanning application of the microbial proteolytic broth was compared with the commercial pancreatic protease under the same conditions. Proteinaceous stain removal from fabric using the produced microbial proteolytic broth was demonstrated and compared with destaining using a commercial detergent.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microorganism

The protease-producing microorganism was isolated from an alkaline spent purge bath (pH 9.45) from a Portuguese tannery (Monteiro Ribas, Porto, Portugal) as previously described [30]. The isolate was taxonomically affiliated within the Bacillus subtilis group and is part of the Culture Collection of Industrial Microorganisms of the Portuguese National Institute for Agricultural and Veterinary Research, INIAV (Oeiras, Portugal), under accession CCMI1253 (BMR2) [30].

The B. subtilis CCMI1253 (BMR2) was maintained on slants or in Petri dishes with nutrient agar (NA) medium at 4 °C (Radiber Sa, UKS-5000, Barcelona, Spain) and was monthly reinoculated.

All culture media (BD Difco, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) were sterilised in an autoclave (AJC, Uniclave 88, Cacém, Portugal) for 20 min at 121 °C.

2.2. Production of Proteolytic Fermentation Broth

The bioreactor preinoculum was prepared in a 2000 mL shake flask containing 500 mL NB medium previously inoculated with 10% inoculum from a smaller flask (250 mL) derived from a single colony on nutrient agar (NA) medium and cultivated at 200 rpm and 37 °C.

The proteolytic crude broth was produced through fermentation in two SGI (Setric Genie Industrial, Toulouse, France) bioreactors with 7 L capacity that were in situ steam-sterilisable. Each bioreactor was inoculated with 10% inoculum (500 mL) in a 5 L sterile medium. Bioreactor working operation was stirring at 200 rpm (rotations per minute) and aeration of 1 vvm (air volume per medium volume per minute); pH and dissolved oxygen were monitored using Ingold electrodes (Ingold, Mettler Toledo, Columbus, OH, USA) connected to the SGI Modular Control Unit (Setric Genie Industrial, Toulouse, France) but that were not online controlled. Temperature was measured with a PT100 probe (SGI, Setric Genie Industrial, Toulouse, France) inserted into the fermenter and maintained at 37 °C using bioreactor online control through cold water or heating. The fermentation medium consisted of 7 g/L beef extract, 4 g/L yeast extract, 5 g/L peptone, and 0.4 g/L CaCl2.

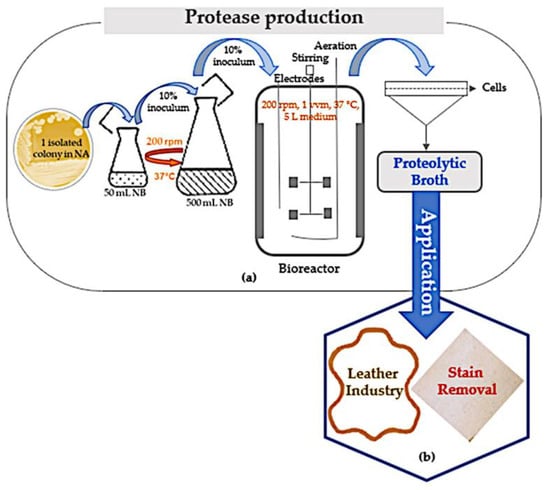

Figure 3 shows the proteolytic fermentation broth production scheme from a single colony in a Petri dish to applications in the leather tanning industry and in stain removal from cotton fabric.

Figure 3.

Proteolytic broth production and applications. (a) Inoculation scheme from the Petri dish to the bioreactor pre-inoculum and the bioreactor fermentation (7 L capacity), followed by cell separation from broth. (b) Proteolytic broth applications in leather-making and stain removal from cotton. NA and NB are nutrient agar and nutrient broth, respectively; rpm is rotations per minute, and vvm is air volume per medium volume.

2.3. Assessment of the Fermentation Broth Properties

Sterile sampling of fermentation broth was performed every hour over the fermentation time (8 h) to assess biomass by measuring optical density at 600 nm in a spectrophotometer (Jasco 7800, Tokyo, Japan). The cells were removed from the sampled fermentation broth through vacuum filtration with a 0.22 μm cellulose membrane filter (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA) to obtain a cell-free crude broth to determine the protein content spectrophotometrically [31] and the proteolytic activities (caseinolytic [32,33] and collagenolytic [34,35,36]) as described in the following sections.

After fermentation, the crude broths from the two fermenters were combined. The downstreaming process of the fermentation crude broth was performed using a tangential filtration system Hi-Flow (SGI, Setric Genie Industrial, Toulouse, France) with a hollow fibre cartridge with a 0.2 μm cut-off to remove the cells, followed by tangential ultrafiltration with 10 kD cut-off regenerated cellulose membranes (Sartorius, Gottingen, Germany), to obtain the proteolytic broth to be used for the protease applications in leather and stain removal and for the proteolytic activity assessments.

All reactants, solvents, and standards used were of reagent or analytical grade (Merck/Sigma, José Manuel dos Santos, Lisbon, Portugal). All solutions were prepared with purified water (Millipore Elix Essential 10, Burlington, MA, USA).

2.3.1. Determination of Protein Content

The protein content of the filtrated broth sample (20 μL) was determined through the Bradford method [31] using a spectrophotometer (Jasco 7800, Tokyo, Japan) at a wavelength (λ) of 595 nm. The calibration curve was made with bovine serum albumin (BSA) over the range 0 to 2000 μg mL−1, with linearity from 200 to 1400 μg mL−1.

2.3.2. Caseinolytic Activity

Colourimetric protease activity was assessed through the Anson and Folin method [32,33] modified by [37], using casein as substrate at 37 °C and pH 7.5, measuring absorbance at 660 nm, and calibrating with L-tyrosine at concentrations ranging from 0 to 55 μM. One unit of proteolytic activity (U) was defined as the amount of enzyme required to hydrolyse 1.0 μmol of L-tyrosine per minute at pH 7.5 and a temperature of 37 °C through the hydrolysis of casein at a wavelength of 660 nm [32,33].

Fluorometric protease activity was assessed through the Twining method [38], modified by Teixeira et al. [39], using fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) derivatisation and a fluorimeter (Hitachi model F3000, Tokyo, Japan) with 525 nm emission, 490 nm excitation, and 3 nm slot opening. One unit of proteolytic activity was defined as the enzymatic activity that increases the emitted fluorescence at 525 nm by one unit, after 30 min of hydrolysis at 37 °C, under the specified assay conditions [39], equivalent to the release of 1 ng of protein/min from the substrate FTC-casein.

Industrial proteolytic bate activity was assessed through the Tegewa method in Löhlein–Volhard Units (LVUs) [40] using Hammarsten casein as a substrate. One unit of bate activity (1.0 LVU) is the amount of proteolytic enzyme that produces an increase in protein degradation products, such as casein, equivalent to 5.75 × 10 −3 mL of a NaOH solution (0.1 N) under the test conditions (at pH 8.2 and during 1 h of reaction at 37 °C).

2.3.3. Collagenase Activity

The collagenolytic activity was determined spectrophotometrically through absorbance measuring at 570 nm, based on the hydrolysis of collagen by collagenases, forming small peptides as a product, stained with ninhydrin, following a method developed by Moore et al. and Mandl et al. [34,35,36], and using a calibration curve with L-leucine at a concentration range from 0 to 0.8 µmol to calculate collagenolytic activity. One unit of collagenolytic activity releases ninhydrin-stained peptides from the collagen molecule, equivalent to 1.0 µmole of L-leucine in 5 h, at pH 7.4 and 37 °C, in the presence of calcium ions.

2.3.4. Elastase Activity

Proteases with elastolytic activity are capable of hydrolysing some of the elastin-orcein peptide bonds and releasing free orcein and small peptides bound to orcein, resulting in an increased absorption at 578 nm; the elastase activity was determined spectrophotometrically as described by Sachar et al. [41] with modifications by Jany et al. [42], using an elastin–orcein substrate and a calibration curve with L-leucin in the range of 0 to 0.8 μmol. One unit of elastase activity is the amount of enzyme that, under test conditions (30 °C, pH 9.2, for 2 h), hydrolyses elastin–orcein to release free orcein and small orcein peptides, equivalent to an increase of 0.002 absorption units per minute at 578 nm.

2.3.5. Keratinase Activity

The keratinolytic activity was determined through the modified method of Hänel et al. [43] using keratin–azure (20 mg) as the substrate and 0.05 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) containing 200 µL of Tween 85 and 0.6 mL of enzyme solution. The mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 1.5 h. After vacuum filtration with a 0.22 µm Millipore membrane, the absorbance was read at 595 nm. Keratinolytic activity was determined from a calibration curve with proteinase K. One unit of keratinolytic activity is the amount of enzyme that releases amino acids and small peptides bound to remazol, as indicated by an increase of 0.002 units of absorbance per minute at 595 nm under test conditions (37 °C, pH 7.5, for 1.5 h).

2.4. Applications of the Proteolytic Broth

The proteolytic fermentation broth was then tested using the proteolytic broth obtained through ultrafiltration after cell removal in the bating step of the hide tanning process and in proteinaceous stain removal from cotton fabric.

2.4.1. Leather Tests

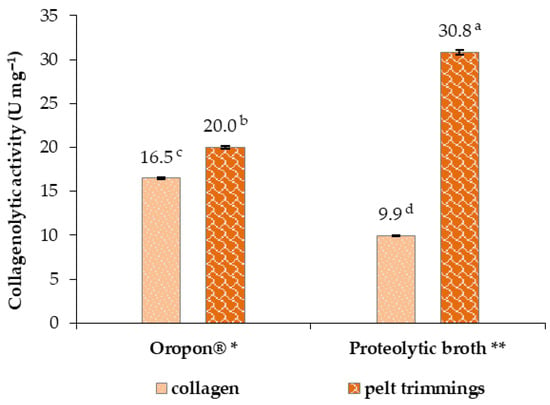

Proteolytic Broth Activity on Collagen and Pelt Trimmings

The collagenolytic activity of the produced microbial proteolytic broth was analysed using collagen and pelt trimmings as substrates and compared with that of the commercial enzymatic cocktail Oropon®. Collagenolytic activity determination is described in Section 2.3.3.

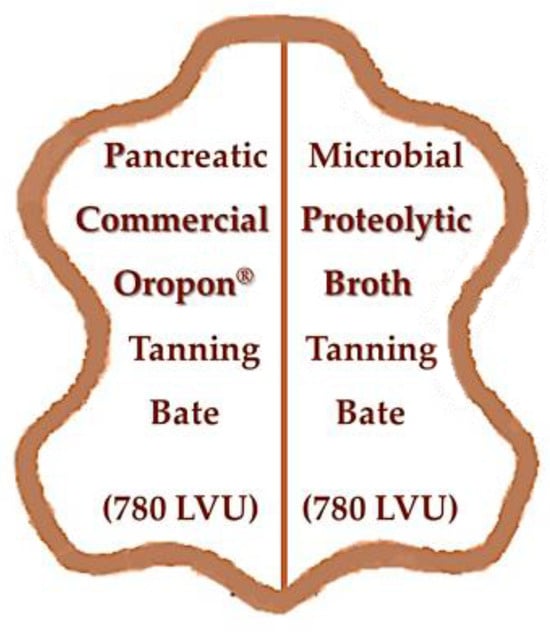

Proteolytic Broth Application in the Leather Bating

The test for application in the tanning process was performed by using the produced fermentation broth with 780 LVU (Löhlein–Volhard Unit) [40] of proteolytic activity on half-skin tanning, and using the commercial pancreatic bate Oropon® (BASF, Ludwigshafen am Rhein, Germany) [44] with the same LVU on the other half-skin tanning, both under the same tanning conditions of conventional tanning leather-making. The Löhlein–Volhard Unit (LVU) is a measure of proteolytic enzyme activity used in the leather industry, usually during the bating operation, a process that removes unwanted proteins and prepares the hide for tanning. One LVU represents the amount of enzyme needed to digest a specific amount of casein (1.725 mg) under standard conditions (pH 8.2 at 37 °C for one hour) [45].

Two hides with different thicknesses (2.4 and 1.6 mm) were used. The proteolytic fermentation broth produced by B. subtilis CCMI1253 (BMR2) was applied to one half of the hide, and the commercial enzyme cocktail Oropon® was applied to the other half for both thicknesses (Figure 4). The tanning trials were carried out at the tanning pilot plant of the Tanning Industry Technological Centre, CTIC, located in Alcanena, Portugal.

Figure 4.

Protease application to the tanning bating step of hides 2.4 and 1.6 mm thick, comparing the microbial proteolytic broth action in half of the hide with the pancreatic commercial enzyme cocktail (Oropon®) action in the other half, using the same 780 LVU proteolytic activity (LVU: Löhlein–Volhard Unit) for the different bates.

The physical properties of the tanned half skins were inferred through the determinations of load (Kg) and elongation (mm) to bursting (ISO 2589:2016 Leather—Physical and mechanical tests—Determination of thickness [46]; ISO 3376:2020 Leather—Physical and mechanical tests—Determination of tensile strength and percentage elongation [47]; ISO 3377-1:2011 Leather—Physical and mechanical tests—Determination of tear load [48]; ISO 3379:2024 Leather—Determination of distension and strength of grain—Ball burst method [49]).

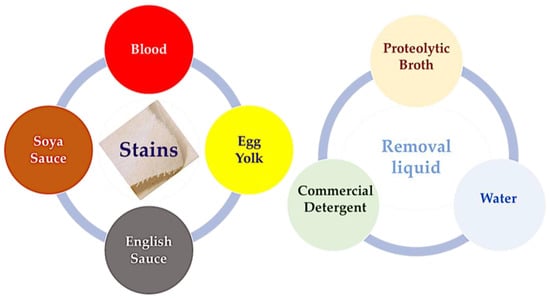

2.4.2. Proteolytic Broth Application in Stain Removal

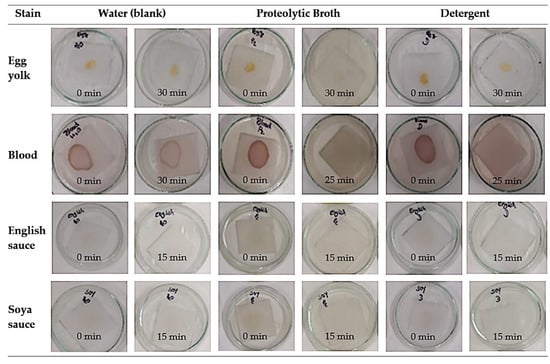

Proteinaceous stain removal from cotton fabric (squares of cotton fabric with the centre stained with egg yolk, blood, soya sauce, and English sauce) was assessed using the produced proteolytic broth and compared with the use of water (blank) or commercial detergent, under the same agitation (150 rpm) at room temperature (Figure 5). Identified cotton fabrics with a 5 cm side were used, on which a stain volume (100 µL) was impregnated and allowed to dry. The stained cotton was placed in different Petri dishes with the same volume (40 mL) of water as a blank, proteolytic broth, or commercial Presto® detergent (Unilever FIMA, Lisbon, Portugal) at 20% (mass of detergent per volume of water). The stain removal was visually observed, and stain removal time was determined in triplicate experiments and reported in minutes.

Figure 5.

Protein stain degradation studies using fermentation proteolytic broth, water, and aqueous solution of commercial detergent to remove blood, egg yolk, soya sauce, and English sauce stains from cotton fabrics. Tests were carried out in Petri dishes with orbital stirring at room temperature.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The Statistica software, v. 8.0 (StatSoft, Tulsa, OK, USA), was used to calculate means and standard deviations through one-way ANOVA with the Tukey HSD test at p < 0.05 (n = 3) to determine significant differences. Graphics presenting standard deviation bars were created using Excel software (Office 2019, Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA).

3. Results and Discussion

The literature includes several papers providing information on the isolation, purification, and characterisation of bacterial strains for protease production, isolated from diverse sources such as soil [50,51], effluent [52], waste [19,53], and marine environments [54,55]. However, protease production by bacteria isolated from leather tanning baths remains scarce. The B. subtilis CCMI1253 (BMR2) used to obtain extracellular proteases was isolated from an alkaline bath from a Portuguese leather industry [30] and produced a proteolytic broth through submerged fermentation in a bioreactor.

3.1. Fermentation Broth Characterisation

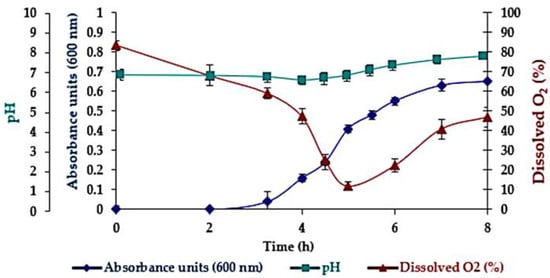

The fermentation pH and dissolved oxygen parameters assessed online and the absorbance at 600 nm (biomass) are presented in Figure 6. An almost 3 h lag phase, followed by an exponential growth phase from 3 to 7 h, and a stationary phase were observed in the absorbance over time analysis [56]. Dissolved oxygen decreased with growth, as expected. The fermentation monitoring revealed that extracellular proteolytic activity initiates simultaneously with a minimum dissolved oxygen of 10% at the end of the exponential growth phase, possibly due to secondary metabolism activation, in which cells, having depleted the more readily assimilable nutrients, start to break down the more complex substrates. The pH was maintained during the lag phase, decreased during the exponential phase, and slightly increased by the end of the exponential growth phase and the stationary phases.

Figure 6.

Biomass, pH, and dissolved oxygen parameters versus fermentation time. Standard deviation error bars (n = 2 bioreactors).

A maximum growth rate of 1.31 ± 0.09 h−1 was calculated using the Monod method [57], based on the slope of the exponential phase data and the logarithmic relationship between the ratio of biomass and initial biomass versus time. The shake flask experiments with the same microorganism achieved a lower growth rate of 0.88 ± 0.10 h−1 [30].

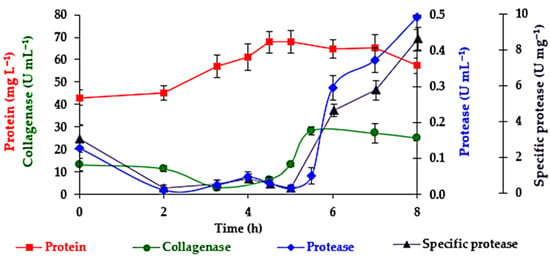

The time course of broth protein content, extracellular proteolytic activities (collagenolytic and caseinolytic), and specific protease (caseinolytic activity per protein mass) is shown in Figure 7. The maximum values observed were (i) a protein content of 68.1 mgL−1 at 5 h, which decreased to 57.3 mg L−1 at the end of fermentation (8 h); (ii) a collagenase activity of 28.5 U mL−1 at 5.5 h, followed by a slight decline toward the end of fermentation; and (iii) a protease activity of 0.49 U ml−1 (8.6 U mg−1 of protein) at the end of fermentation. The maximum proteolytic activities (collagenolytic and caseinolytic) occurred at the end of the exponential growth phase, in agreement with the previous reports for B. subtilis by Abe et al. [58] and by the authors’ earlier shake flask study [30].

Figure 7.

Protein content [31] in mg L−1, protease activity (caseinolytic) in U mL−1, and specific protease activity in U mg−1 of protein versus fermentation time. Standard deviation error bars (n = 2 bioreactors). One unit (U) of collagenolytic activity was defined by Moore et al., 1948 and 1954, and Mandl et al., 1953 [34,35,36], using collagen as substrate. One unit of proteolytic activity was defined by Anson 1938 and Folin 1929 [32,33] using casein as substrate.

3.2. Fermentation Broth Proteolytic Activities Comparison with the Pancreatic Enzymatic Cocktail

Table 1 compares the specific proteolytic activities of the microbial proteolytic broth and the commercial pancreatic protease Oropon®. The microbial enzymatic broth showed higher specific proteolytic activities than those of the pancreatic commercial cocktail, including collagenolytic activity using pelt trimmings as substrate, elastolytic, keratinolytic, and Löhlein–Volhard industrial enzymatic activity. Due to the high insolubility of the commercial enzymatic cocktail, the results were presented per mg of Oropon® since it was not possible to determine the protein content of the commercial enzyme. For the fermentation proteolytic broth, the specific activity results were presented per mg of total protein determined in [31].

Table 1.

Proteolytic broth and Oropon® commercial cocktail assessment to specific caseinolytic, collagenolytic, elastolytic, and keratinolytic activities.

As shown in Table 1, the proteolytic broth activity was higher than the OPORON® enzymatic activity, except for collagenolytic activity.

The proteolytic activities determined at pH 5.0 and pH 8.0 for the cell-free fermentation broth and the commercial enzymatic cocktail Oropon® are presented in Table 2. The pH increasing from 5 to 8 led to about a 20% higher proteolytic activity for both enzyme sources, the microbial and the pancreatic, due to the alkaline proteases.

Table 2.

Proteolytic broth and Oropon® commercial cocktail assessment of proteolytic activities at different pH using the Twining modified method [39].

3.3. Applications of the Produced Proteolytic Broth

Proteolytic broth applications in leather processing and in stain removal from cotton fabrics will be presented and discussed.

3.3.1. Leather Tests

Proteolytic Broth Activity on Collagen and Pelt Trimmings

The collagenolytic activity of the microbial proteolytic broth produced was analysed using collagen and pelt trimmings as substrates, and the activities were compared with those of the pancreatic commercial enzymatic cocktail Oropon®, and are presented in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Collagenolytic activity using collagen and pelt trimmings as substrates (Moore et al., 1948 and 1954, and Mandl et al., 1953 method [34,35,36], with standard deviation error bars (n = 2)). U: One unit releases ninhydrin-stained peptides from the collagen molecule, equivalent to 1.0 µmole of L-leucine in 5 h at pH 7.4 and 37 °C, in the presence of calcium ions [34,35,36]. * Results in U mg−1 of the Oropon® weight. ** Results in U mg−1 of the protein content. The data are presented as the means calculated using one-way ANOVA (p < 0.05) with standard deviation error bars (n = 3). Different letters express significant differences (Tukey test) with a for the highest value.

The results presented in Figure 8 showed that the collagenolytic activity was higher when pelt trimmings were used as a substrate than when collagen was used, in either the pancreatic Oropon® or the microbial proteolytic broth. The proteolytic broth exhibited a higher activity against pelt trimmings than the pancreatic enzymes, showing the potential application of the broth’s microbial protease in the leather industry.

Proteolytic Broth Application in the Leather Bating

The hide tanned using the proteolytic fermented broth and the hide tanned with pancreatic commercial bate’s physical properties were assessed in terms of the bursting load (kg) and bursting elongation (mm) for hides with two different leather thicknesses (2.4 mm and 1.6 mm). The results are shown in Table 3. The hide tanned with the produced proteolytic broth showed better physical tests for bursting (with elongation till 6.8 mm before bursting) than the one tanned with commercial proteases (elongation only till 6.3 mm) for the same bursting load of 19 kg and 1.6 mm leather thickness. The thicker leather (2.4 mm) showed the same bursting elongation of 10 mm at a higher load (54 Kg) for the hide tanned with bulk proteases than commercial proteases.

Table 3.

The physical–mechanical properties of skins tanned using concentrated proteolytic broth (microbial bulk proteases bate) and pancreatic commercial bate (Oropon®) with enzyme activities of 780 LVU under the same tanning conditions.

Thinner-skin tanning with the microbial proteolytic broth showed better physical tests for leather elongation (6.8 mm) for the same load than pancreatic commercial proteases with the same enzymatic activity and tanning process conditions. Microbial proteolytic broth application in the 1.6 mm thickness skin showed an 8% greater elongation than the commercial protease application at the same enzymatic activity and tanning process conditions. The thicker skin with microbial bulk proteases showed the same elongation as pancreatic commercial tanning for a 2% lower load force. The reported differences are not statistically meaningful, since they were obtained with only two replicates, but they present a trend in the studied applications.

The proteolytic broth’s ability to increase leather elongation by 8% compared with commercial proteases (under the tested conditions and formulations of proteolytic bate activity and leather processing conditions) indicates an improved fibre modification and better penetration, directly correlating with higher quality, more durable leather. This greater leather stretching may be due to the greater elastolytic activity of the proteolytic broth in relation to that of the commercial enzyme.

Alam et al. [59] used crude protease produced by bacteria isolated from a tannery solid waste dumping yard, achieving significant reductions in chemical usage and improvements in leather mechanical properties, such as tensile strength and grain crack load [59]. Their results support the 8% increase in leather elongation obtained with the present microbial proteolytic broth application compared to the commercial pancreatic protease leather application under identical conditions. Recent studies that applied microbial proteases to enhance leather properties have demonstrated microbial proteases’ efficacy in the leather industry [20,59,60].

The pancreatic commercial bate, derived from animal pancreas, raises ethical and cost concerns, and its proteolytic activity is mainly due to trypsin and chymotrypsin. The proteolytic broth produced from a microbial source enables applications at higher pH and temperature ranges, offering various enzymatic activities (alkaline proteases, keratinases, and lipases), as well as a lower allergenicity due to its production by a Generally Recognised as Safe (GRAS) microorganism, such as Bacillus subtilis [61]. The microbial proteolytic broth is more sustainable and environmentally friendly, making it a greener alternative to pancreatic bate.

Microbial broths derived from low-value biomass or food waste can create high-value outputs, supporting the transition toward zero-waste manufacturing.

3.3.2. Stain Removal Tests

Regarding the use of proteolytic broth in proteinaceous stain removal, Figure 9 shows the results of stain removal from cotton fabric stained with egg yolk, blood, English sauce, and soya sauce using water action as a blank, in contrast to the actions of the proteolytic broth produced through B. subtilis CCMI1253 (BMR2) fermentation and a commercial detergent (Presto®). The proteolytic broth removed blood and egg yolk stains better than water or the detergent.

Figure 9.

Pictures of the stain removal experiments at the beginning and the end. Tests of stain removal from the cotton fabric of egg yolk, blood, and sauces with proteolytic broth, commercial Presto® detergent, and water as blank, under orbital agitation at room temperature. Stain images showing labels for the average time of stain removal, in minutes, for triplicate assays (standard deviation < 1 min).

The application of the produced proteases to remove stains from cotton fabric demonstrated a better removal of blood and egg yolk stains than the detergent or water, with removal times of 30 min for egg yolk, 25 min for blood, and around 15 min for soya sauce and English sauce. The assessment of proteinaceous stain removal by the proteolytic broth resulted in, compared to egg removal, 16.7% and 50% reductions in process time for blood and sauces, respectively. Under the tested conditions and formulations, the results suggested that the proteases produced can also be used as additives in detergent formulations to remove proteinaceous stains from clothes and to treat proteinaceous wastes and effluents.

To obtain more accurate results, other stain removal examination methods [62], such as colorimetric [63] or image analyses [64], should be performed in addition to the visual evaluation. Also, the proteolytic broth compatibility with detergents [65] needs to be assessed.

Alshehri et al. [64] reported industrial proteolytic applications to replace chemical catalysts with eco-friendly solutions, using an extracellular protease produced by a newly isolated Bacillus paramycoides, suggesting that the thermostable, alkaline, and detergent-biocompatible protease could be a promising additive for eco-friendly use in the detergent industry [64].

In the search for innovative strategies to improve proteolytic stabilisation, extensive research has focused on increasing enzyme stability through techniques such as the immobilisation [24], aggregation, and chemical modification of the enzyme structure [66] and encapsulation [67]. Yang et al. (2024) also improved the proteolytic stability through enzyme-catalysed crosslinking for detergent application [67].

Enzymes replace harsh chemicals, reducing environmental impact and promoting low-energy and low-toxicity reactions, as demonstrated by [22,23,25,26]. Proteases are naturally degradable, unlike synthetic detergents which can persist in ecosystems.

The leather-making and stain removal applications demonstrated the potential for bioeconomy and green chemistry development.

4. Conclusions

Microbial enzymes produced through scalable fermentation processes offer a sustainable alternative to animal-derived enzymes, with lower environmental impacts on greenhouse gas emissions and land and water use, as indicated by life cycle assessment studies. In this work, the high extracellular proteolytic activity obtained with short fermentation times demonstrates industrial scalability and energy efficiency.

The enzymatic activities achieved support the potential replacement of pancreatic enzymes in industrial applications, facilitating more reliable supply chains and integration into circular bioeconomy models. Moreover, the direct use of proteolytic broth rather than purified enzymes provides an additional economic advantage for industrial processing applications, especially for leather and detergents.

Microbial proteolytic fermented broth application in the leather tanning of thinner skin resulted in better physical leather test results, with 8% more elongation than leather tanned with commercial proteases, under the tested conditions and formulations using the same enzymatic activity and tanning process conditions. The microbial proteolytic broth is a greener alternative to pancreatic bates for leather industry applications.

The shift towards sustainable leather processing has led to the exploration of microbial enzymes as an alternative to traditional animal-derived bating agents. This work contributes to this trend by showcasing a greener alternative that improves leather quality and aligns with environmental sustainability goals.

Regarding the stain removal application, the proteolytic broth showed better blood and egg yolk stain removal than Presto® commercial detergent or water, under the tested conditions and formulations. The removal of sauce stains was faster, followed by blood and egg yolk removal.

Future research should focus on protease characterisation, kinetic parameter study, fermentation production optimisation, enzyme separation from broth, and protease purification. The long-term operational stability and reuse of the proteolytic broth under process conditions should be assessed. The enzymatic activity and stability (effects of temperature, pH, salt, and heavy metals), as well as the impact of surfactants and oxidising agents on broth proteolytic activity, need to be investigated. In particular, for the protease’s biochemical and molecular characterisation, the effects of inhibitors and metal ions on alkaline protease activity, as well as the determination of the protease’s molecular weight, should also be performed.

The study presented an innovative approach based on the application of an extremophilic strain isolated from an unconventional industrial environment (leather industrial baths), offering novel biotechnological solutions that address current challenges in enzyme-based industrial applications in pursuit of sustainability and more efficient production systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.L.; methodology, M.L. and M.J.M.; formal analysis, M.L., N.A. and A.R.; investigation, M.L. and M.J.M.; resources, M.L., A.R. and N.A.; data curation, M.L.; writing—original draft preparation, M.L., F.S., N.A. and A.R.; writing—review and editing, M.L., M.J.M., F.S., N.A. and A.R.; visualisation, M.L., M.J.M., F.S., N.A. and A.R.; supervision, A.R. and N.A.; project administration, M.L., A.R. and N.A.; funding acquisition, A.R., N.A. and M.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, IP through the Research Unit GEOBIOTEC: UID/04035/2025, https://doi.org/10.54499/UID/04035/2025.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable, since the study did not involve animals or human beings and did not require ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

For the technical support of Cláudia Correia, and Manuela Vida from INIAV staff. This research has been also carried out at the Biomass and Bioenergy Research Infrastructure (BBRI)-LISBOA2030-FEDER-01318200 which is supported by Lisbon Portugal Regional Operational Programme (Lisboa 2030), Portugal 2030, and the European Union.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Solanki, P. Microbial Proteases: Ubiquitous Enzymes with Innumerable Uses. 3 Biotech 2021, 11, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lageiro, M.M. Optimização Da Produção de Proteases Microbianas Para Aplicações Agro-Industriais. In Proceedings of the Encontro Ciência’20, Lisbon, Portugal, 3–4 November 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrudula, S. A Review on Microbial Alkaline Proteases: Optimization of Submerged Fermentative Production, Properties, and Industrial Applications. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2024, 60, 383–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angulo, M.; Márquez, M.C. A Green Technology Approach Using Enzymatic Hydrolysis to Valorize Meat Waste as a Way to Achieve a Circular Economy. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lageiro, M.; Alvarenga, N.; Lourenço, V.; Simões, F.; Reis, A. Isolamento, optimização da produção e aplicação agroindustrial de proteases microbianas. In Livro de Resumos do 7 Simpósio Produção e Transformação de Alimentos em Ambiente Sustentável; Instituto Nacional de Investigação Agrária e Veterinária (INIAV): Oeiras, Portugal, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contesini, F.J.; Melo, R.R.d.; Sato, H.H. An Overview of Bacillus Proteases: From Production to Application. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2018, 38, 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurumallesh, P.; Alagu, K.; Ramakrishnan, B.; Muthusamy, S. A Systematic Reconsideration on Proteases. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 128, 254–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lageiro, M.; Alvarenga, N.; Lourenço, V.; Simões, F.; Ferreira-Dias, S.; Reis, A. Alkaline Proteases from Bacillus CCMI 1253 Production and Agroindustry Applications. In Proceedings of the Encontro Ciência’23, Aveiro, Portugal, 5–7 July 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Savitri; Thakur, N.; Verma, R.; Bhalla, T.C. Microbial Proteases and Application as Laundry Detergent Additive. Res. J. Microbiol. 2008, 3, 661–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lageiro, M.; Alvarenga, N.; Lourenço, V.; Reis, A. Produção de Proteases Microbianas Com Bacillus CCMI 1253 Para Aplicações Agro-Industriais. In Proceedings of the Encontro Ciência’21, Lisbon, Portugal, 28–30 June 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, T.A. Bacterial Protease Enzyme: Safe and Good Alternative for Industrial and Commercial Use. Int. J. Chem. Biomol. Sci. 2017, 3, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Z.; Shafique, M.; Jabeen, N.; Naz, S.A.; Yasmeen, K.; Ejaz, U.; Sohail, M. Protease from Bacillus Subtilis ZMS-2: Evaluation of Production Dynamics through Response Surface Methodology and Application in Leather Tannery. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2023, 35, 102643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Gat, Y.; Arya, S.; Kumar, V.; Panghal, A.; Kumar, A. A Review on Microbial Alkaline Protease: An Essential Tool for Various Industrial Approaches. Ind. Biotechnol. 2019, 15, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, J.; Modi, D.R.; Sharma, R.; Saxena, S. Vital Role of Alkaline Protease in Bio-Industries: A Review. Plant Arch. 2011, 11, 1083–1092. [Google Scholar]

- Kumari, A.; Kaur, B.; Srivastava, R.; Sangwan, R.S. Isolation and Immobilization of Alkaline Protease on Mesoporous Silica and Mesoporous ZSM-5 Zeolite Materials for Improved Catalytic Properties. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2015, 2, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mhamdi, S.; Ktari, N.; Hajji, S.; Nasri, M.; Sellami Kamoun, A. Alkaline Proteases from a Newly Isolated Micromonospora chaiyaphumensis S103: Characterization and Application as a Detergent Additive and for Chitin Extraction from Shrimp Shell Waste. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 94, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariram, N.; Madhan, B. Development of Bio-Acceptable Leather Using Bagasse. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 250, 119441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.J.; Haque, P.; Rahman, M.M. Protease Enzyme Based Cleaner Leather Processing: A Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 365, 132826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffari, Z.H.; Hong, J.; Park, K.Y. A Systematic Review of Innovations in Tannery Solid Waste Treatment: A Viable Solution for the Circular Economy. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 948, 174848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, M.M.; Harris, J.; Busfield, J.J.C.; Bilotti, E. A Review of the Green Chemistry Approaches to Leather Tanning in Imparting Sustainable Leather Manufacturing. Green Chem. 2023, 25, 7441–7469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.K.; Sharma, P.C. Current Trends in Solid Tannery Waste Management. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2023, 43, 805–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundar, V.J.; Gnanamani, A.; Muralidharan, C.; Chandrababu, N.K.; Mandal, A.B. Recovery and Utilization of Proteinous Wastes of Leather Making: A Review. Rev. Environ. Sci. Bio Technol. 2011, 10, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maina, P.; Ollengo, M.A.; Nthiga, E.W. Trends in Leather Processing: A Review. Int. J. Sci. Res. Publ. 2019, 9, p9626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Qiang, X.; Liu, D.; Yu, L.; Wang, X. An Eco-Friendly Tanning Process to Wet-White Leather Based on Amino Acids. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 270, 122399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasoń-Rydel, M.; Sieczyńska, K.; Gendaszewska, D.; Ławińska, K.; Olejnik, T.P. Use of Enzymatic Processes in the Tanning of Leather Materials. AUTEX Res. J. 2024, 24, 20230012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, S.; Roy, M.; Pal, P. Corporate Greening in a Large Developing Economy: Pollution Prevention Strategies. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2019, 21, 1603–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khambhaty, Y. Applications of Enzymes in Leather Processing. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2020, 18, 747–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G. Protease Assays 2012 updated-1 October 2012. In Assay Guidance Manual; Markossian, S., Grossman, A., Baskir, H., Arkin, M., Auld, D., Austin, C., Baell, J., Brimacombe, K., Chung, T.D.Y., Coussens, N.P., et al., Eds.; Eli Lilly & Company: Indianapolis, IN, USA; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Greenfield, L.M.; Puissant, J.; Jones, D.L. Synthesis of Methods Used to Assess Soil Protease Activity. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2021, 158, 108277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lageiro, M.; Simões, F.; Alvarenga, N.; Reis, A. Proteolytic Bacillus Sp. Isolation and Identification from Tannery Alkaline Baths. Molecules 2025, 30, 3632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.M. A Rapid and Sensitive Method for the Quantitation of Microgram Quantities of Protein Utilizing the Principle of Protein-Dye Binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anson, M.L. The Estimation of Pepsin, Trypsin, Papain, and Cathepsin with Hemoglobin. J. Gen. Physiol. 1938, 22, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folin, O.; Ciocalteu, V. On Tyrosine and Tryptophane Determinations in Proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 1927, 73, 627–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.; Stein, W.H. Photometric Ninhydrin Method for Use in the Chromatography of Amino Acids. J. Biol. Chem. 1948, 176, 367–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.; Stein, W.H. A Modified Ninhydrin Reagent for the Photometric Determination of Amino Acids and Related Compounds. J. Biol. Chem. 1954, 211, 907–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandl, I.; MacLennan, J.D.; Howes, E.L.; DeBellis, R.H.; Sohler, A. Isolation and Characterization of Proteinase and Collagenase from Cl. Histolyticum. J. Clin. Investig. 1953, 32, 1323–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cupp-Enyard, C. Sigma’s Non-Specific Protease Activity Assay—Casein as a Substrate. JoVE 2008, 19, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twining, S.S. Fluorescein Isothiocyanate-Labeled Casein Assay for Proteolytic Enzymes. Anal. Biochem. 1984, 143, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, G.; Santana, A.; Pais, M.; Clemente, A. Enzymes of Opuntia Ficus-Indica (L.) Miller with Potential Industrial Applications-I. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. Part A Enzym. Eng. Biotechnol. 2000, 88, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löhlein-Volhard 1975. Determination de La Actividad de Preparados Enzimáticos Proteoliticos Según Löhlein-Volhard (Tegewa Method). In Análisis de Materias Primas; Escuela Syndical Nacional de Tenería: Barcelona, Spain, 1985; p. 1B. [Google Scholar]

- Sachar, L.A.; Winter, K.K.; Sicher, N.; Frankel, S. Photometric Method for Estimation of Elastase Activity. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1955, 90, 323–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jany, K.-D. Studies on the Digestive Enzymes of the Stomachless Bonefish Carassius auratus gibelio (Bloch): Endopeptidases. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part B Comp. Biochem. 1976, 53, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hänel, H.; Kalisch, J.; Keil, M.; Marsch, W.C.; Buslau, M. Quantification of Keratinolytic Activity from Dermatophilus congolensis. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 1991, 180, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, A.; Natt, M.A.; Evans, C.S. Comparative Studies of a New Microbial Bate and the Commercial Bate ‘Oropon’ in Leather Treatment. J. Ind. Microbiol. 1996, 17, 77–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crispim, A.; Mota, M. Unhairing with Enzymes. J. Soc. Leather Technol. Chem. 2003, 87, 198. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 2589:2016; Leather—Physical and Mechanical Tests—Determination of Thickness (ISO Standard No. 2589:2016(E)|IULTCS/IUP 4:2016(E)). International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- ISO 3376:2020; Leather—Physical and Mechanical Tests—Determination of Tensile Strength and Percentage Elongation (ISO Standard No. 3376:2020(E)|IULTCS/IUP 6:2020(E)). International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- ISO 3377-1:2011; Leather—Physical and Mechanical Tests—Determination of Thickness (ISO Standard No. ISO 3377-1:2011/IULTCS/IUP 40-1:2011). International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011.

- ISO 3379:2024; Leather—Physical and Mechanical Tests—Determination of Thickness (ISO Standard No. ISO 3379:2024|IULTCS/IUP 9). International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024.

- Ugbede, A.S.; Abioye, O.P.; Aransiola, S.A.; Oyewole, O.A.; Maddela, N.R.; Prasad, R. Production, Optimization and Partial Purification of Bacterial and Fungal Proteases for Animal Skin Dehairing: A Sustainable Development in Leather-Making Process. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2023, 24, 101632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, N.; Rehman, M.U.; Sarwar, A.; Nadeem, M.; Nelofer, R.; Shakir, H.A.; Irfan, M.; Idrees, M.; Naz, S.; Nabi, G.; et al. Purification, Characterization, and Application of Alkaline Protease Enzyme from a Locally Isolated Bacillus Cereus Strain. Fermentation 2022, 8, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desalegn, T.; Bacha, K.; Masi, C. The Effectiveness of Proteolytic Bacteria in the Leather and Detergent Industry Isolated Waste from the Modjo Tannery. Kuwait J. Sci. 2021, 50, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahmy, N.M.; El-Deeb, B. Optimization, Partial Purification, and Characterization of a Novel High Molecular Weight Alkaline Protease Produced by Halobacillus sp. HAL1 Using Fish Wastes as a Substrate. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2023, 21, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzkar, N. Marine Microbial Alkaline Protease: An Efficient and Essential Tool for Various Industrial Applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 161, 1216–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loperena, L.; Soria, V.; Varela, H.; Lupo, S.; Bergalli, A.; Guigou, M.; Pellegrino, A.; Bernardo, A.; Calviño, A.; Rivas, F.; et al. Extracellular Enzymes Produced by Microorganisms Isolated from Maritime Antarctica. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 28, 2249–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro-Pérez, M.L.; Fernández-Calderón, M.C.; Vadillo-Rodríguez, V. Decomposition of Growth Curves into Growth Rate and Acceleration: A Novel Procedure to Monitor Bacterial Growth and the Time-Dependent Effect of Antimicrobials. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2022, 88, e01849-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monod, J. The Growth of Bacterial Cultures. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 1949, 3, 371–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, S.; Yasumura, A.; Tanaka, T. Regulation of Bacillus Subtilis aprE Expression by glnA through Inhibition of scoC and σD-Dependent degR Expression. J. Bacteriol. 2009, 191, 3050–3058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.; Hasan, J.; Haque, P.; Rahman, M.M. Sustainable Leather Tanning: Enhanced Properties and Pollution Reduction through Crude Protease Enzyme Treatment. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 268, 131858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biškauskaitė, R.; Valeikienė, V.; Valeika, V. Enzymes for Leather Processing: Effect on Pickling and Chroming. Materials 2021, 14, 1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Liu, C.; Fang, H.; Zhang, D. Bacillus Subtilis: A Universal Cell Factory for Industry, Agriculture, Biomaterials and Medicine. Microb. Cell Factories 2020, 19, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niyonzima, F.N.; More, S. Detergent-Compatible Proteases: Microbial Production, Properties, and Stain Removal Analysis. Prep. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2015, 45, 233–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khazi, M.I.; Kut, D.; Liaqat, F.; Demirkan, E. Synergistic Protease-Lipase Treatment for Enhanced Blood Stain Removal from Textiles: Process Optimization and Efficacy Evaluation. Process Biochem. 2025, 156, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshehri, W.A.; Alhothifi, S.A.; Khalel, A.F.; Alqahtani, F.S.; Hadrich, B.; Sayari, A. Production Optimization of a Thermostable Alkaline and Detergent Biocompatible Protease by Bacillus paramycoides WSA for the Green Detergent Industry. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 13205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, S.S.; Nair, B.G.; SadasivanNair, S.; GopalakrishnaPai, J. Proteases from Marine Endophyte, Bacillus Subtilis ULB16: Unlocking the Industrial Potential of a Marine-Derived Enzyme Source. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2025, 64, 103503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aruna, V.; Chandrakala, V.; Angajala, G.; Nagarajan, E.R. Proteases: An Overview on Its Recent Industrial Developments and Current Scenario in the Revolution of Biocatalysis. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 92, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Ren, X.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, T.; Xiao, J.; Chen, H. Enhancing Alkaline Protease Stability through Enzyme-Catalyzed Crosslinking and Its Application in Detergents. Processes 2024, 12, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.