Abstract

In health sciences, the population-level burden of dental caries makes oral health education and the integration of theory and practice a priority. This quasi-experimental study examined whether augmented reality (AR) using the Merge Object Viewer improves basic dental knowledge, is associated with visual symptoms, and is acceptable compared with two-dimensional (2D) materials. A total of 321 students enrolled in health-related programmes participated and were assigned to three AR/2D sequences across three blocks (healthy dentition, cariogenesis, and pain management). Outcomes included knowledge (15-item test, pre and post intervention), computer vision syndrome (CVS-Q), acceptance (TAM-AR), and open-ended comments. Knowledge improved in all groups: 2D materials were superior for dentition, AR for cariogenesis, and both were comparable for pain. Two-thirds met criteria for symptoms on the CVS-Q, with a lower prevalence in the AR–2D–AR sequence. Acceptance was high, and comments highlighted usefulness, ease of use, and enjoyment, but also noted language issues and technical overload. Overall, AR appears to be a complementary tool to 2D materials in basic dental education.

1. Introduction

In recent years, health sciences education has undergone rapid digital transformation, with immersive technologies—such as augmented reality (AR) and other forms of extended reality (XR)—increasingly integrated into undergraduate, postgraduate, and continuing professional education [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Foresight reports and institutional guidelines highlight the expansion of immersive laboratories and pilot programmes, while also pointing to challenges related to ethics, privacy, equity of access, and sustainability [1,2,3,7,8]. Recent reviews indicate that AR and virtual reality (VR) can enhance academic performance, clinical competency development, and student motivation compared with traditional methods, although reported effect sizes are moderate and heterogeneity remains high [4,5,6,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. In dental education, the digitalization process is also accelerating [17], while students frequently report substantial stress burdens [18].

AR enables learners to interact with three-dimensional anatomical and clinical models directly within the physical environment, promoting active learning, spatial understanding, and self-regulated study, in accordance with the principles of meaningful learning and cognitive load theory [4,10,19,20,21,22,23,24]. However, evidence also reveals important limitations: quasi-experimental designs or experience reports predominate, outcome measures are often heterogeneous, and many studies focus primarily on affective outcomes (e.g., satisfaction, motivation) rather than theoretical knowledge acquisition of transfer to clinical context [3,4,5,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,21]. Moreover, questions remain regarding the optimal pedagogical models for sequencing of XR with two-dimensional (2D) resources, cost-effectiveness, and scalability beyond isolated pilot experiences [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,25,26].

The intensive use of immersive and screen-based technologies also raises concerns regarding protentional adverse effects. Computer vision syndrome (CVS), or digital eye strain, encompasses a range of ocular and extraocular symptoms (headache, cervical pain, etc.) associated with prolonged screen use [27,28]. Studies in student populations report a CVS prevalence exceeding 50–60%, with associations to exposure time, ergonomics, and insufficient visual breaks [17,27,29,30,31,32,33,34,35]. Although experimental research on 3D technologies and head-mounted displays has documented visual fatigue and transient accommodative changes [12,36,37,38], educational AR interventions rarely assess these effects systematically using validated instruments such as the CVS-Q [28].

Oral health represents a particularly relevant educational domain. According to the WHO, untreated dental caries is the most prevalent health condition worldwide [39,40]. Their repercussions for quality of life translate into substantial costs for individuals and healthcare systems [41,42,43,44]. Consequently, there is broad consensus on the need to more strengthen oral health education within health professions curricula, particularly regarding oral anatomy, cariogenesis, and pain management [45,46,47].

Although dentistry has rapidly adopted immersive technologies for anatomy education, procedural planning, and preclinical training, much of the available evidence is based on small samples, heterogeneous designs, and focus on practical skills or learner satisfaction [4,5,9,10,11,12,13,14,16,21,48,49]. Evidence remains limited regarding the effect of AR on theoretical knowledge in basic dentistry; the impact of different AR/2D sequencing patterns on CVS; and technology acceptance assessed through established models such as the AR-adapted Technology Acceptance Model (TAM-AR) [8,20,21,23,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,50].

Within this framework, the present study aimed to examine the effect of an AR tool based on 3D models (Merge Object Viewer, a mobile augmented reality application from Merge Labs Inc., San Antonio, TX, 78213, US, that enables the interactive exploration of three-dimensional educational content using smartphones or tablets), compared with conventional 2D resources, on theoretical learning outcomes in basic dentistry among vocational health students. Additionally, the study analyzed the impact of different AR/2D patterns on CVS prevalence and explored students’ satisfaction and technological acceptance using the TAM-AR and the CVS-Q. Two specific hypotheses were proposed: (a) that the use of augmented reality (AR) would yield a significantly greater improvement in theoretical knowledge scores than conventional 2D resources; and (b) that sequences involving two consecutive AR activities at the beginning or at the end of the session would be associated with higher levels of CVS than an alternating AR/2D sequence, in line with the available evidence on cognitive load and visual fatigue in immersive environments. To address these issues, the study was structured around the following research questions:

- RQ1: Does the use of AR with Merge Object Viewer lead to a significantly greater improvement in the acquisition of theoretical knowledge in basic dentistry (dentition, cariogenesis, and pain) than conventional 2D instructional resources?

- RQ2: Are there differences in the presence of CVS—as an expression of digital visual fatigue measured with the CVS-Q—among the different activity-sequencing patterns (2D–AR–AR, AR–2D–AR, AR–AR–2D) following the AR intervention?

- RQ3: What is the level of students’ satisfaction and technology acceptance regarding the use of AR, and what comments do participants provide to inform improvements in future interventions?

Overall, this study seeks to contribute empirical evidence to support a more critical and evidence-based integration of AR as a complementary tool to traditional 2D materials in health science education, particularly in basic dentistry.

2. Materials and Methods

In this section, the design and sequencing of the experimental conditions, the participants’ characteristics, the implementation of AR and 2D materials are described. The assessment instruments employed and the procedure followed to address the stated research questions are also detailed.

2.1. Participants

Sample size was determined by the accessible population in the participating centres during the study period. The final analyzed sample comprised 321 students enrolled in health-related vocational training programmes from six public Spanish centres located in the provinces of Álava, Ávila, Burgos, La Rioja, and Salamanca. Participants were allocated to three experimental groups (G1, G2 and G3) of comparable size, which followed different sequences of AR/2D intervention, as detailed in the study design section.

2.2. Instruments

In this study, three types of instruments were employed: (a) an ad hoc knowledge test; (b) a technology acceptance questionnaire adapted to AR (TAM–AR), previously validated in educational contexts with and extra open-ended question; and (c) the Computer Vision Syndrome Questionnaire (CVS-Q), a standardized and validated instrument for detecting computer vision syndrome.

Whereas TAM–AR and the CVS-Q constitute established measurement protocols widely used in the literature, the knowledge test and the open-ended question were specifically designed to meet the objectives of this study.

2.2.1. Knowledge Test

An ad hoc knowledge test specific to the study was developed, comprising 15 items distributed across three content blocks: (1) characteristics of healthy dentition and dental units (5 items); (2) prevention and identification of carious lesions (5 items); and (3) treatment and pain control (5 items). Within each block, five question formats were included: one short-answer question requiring justification, one dichotomous item (true/false), one single-best-answer multiple-choice question, one multiple-response multiple-choice question, and one item requiring the ordering of sequences or procedures. Item wording was derived from the learning outcomes and curricular contents of the module “Basic Techniques of Dental Assistance” within the intermediate vocational training programme for “Auxiliary Nursing Technician”, ensuring a direct correspondence between each item and a specific knowledge objective. Each item was scored on a 0–1 point scale. For the multiple-response and ordering items, intermediate partial-credit scores were assigned in proportion to the number of correct responses selected or steps correctly ordered, such that the maximum possible test score was 15 points. This instrument was used to objectively assess the level of learning achieved by students before and after the instructional experience (AR vs. 2D). Table A1 in Appendix A summarizes the structure and objectives of the knowledge test.

2.2.2. Technological Acceptance Questionnaire (TAM-AR)

An adaptation of the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) to Augmented Reality (AR)—the TAM-AR—previously validated in educational contexts by Cabero-Almenara and Pérez Díez de los Ríos, was employed [50]. This questionnaire constitutes a standardized and validated instrument designed to assess perceived satisfaction, usefulness, and technological acceptance of AR, as well as students’ willingness to incorporate this type of tool in future vocational training contexts. The questionnaire comprises 15 seven-point Likert-type items (1 = strongly disagree/extremely unlikely; 7 = strongly agree/extremely likely), organized into five theoretical dimensions: perceived usefulness (4 items), perceived ease of use (3 items), perceived enjoyment (3 items), attitude toward use (3 items), and intention to use (2 items). Each item was coded directly from 1 to 7, such that higher scores indicated greater acceptance or a more positive appraisal of the system, except for the negatively worded item (“I became bored while using the AR system”), which was treated as a reverse-scored item. For this item, recoding was performed using the transformation:

Xrecoded = 8 − Xoriginal

Subsequently, mean scores were computed for each dimension as the arithmetic average of the items comprising it, and an overall score for acceptance of AR was obtained as the mean of the 15 items after recoding.

At the end of the TAM–AR questionnaire, an optional open-ended question was included in which students could freely provide comments and suggestions regarding their experience with AR. In accordance with the coding criteria, a positive evaluation could be accompanied by mentions of specific problems or limitations, whereas negative evaluations were reserved for comments that were clearly unfavourable toward the tool or the session.

2.2.3. Computer Vision Syndrome Questionnaire (CVS-Q)

The CVS-Q, in its original Spanish-language version—developed and validated for the detection of CVS in working populations—was administered [28]. This standardized and widely used instrument, assesses the presence of 16 ocular and visual symptoms (e.g., burning, itching, ocular dryness, blurred vision, difficulty focusing at near distances, headache), recording for each symptom its frequency (never, occasionally, often/always) and intensity (moderate, intense). For score computation, symptom frequency is first coded as 0 (never), 1 (occasionally), or 2 (often/always), and symptom intensity as 1 (moderate) or 2 (intense). In a first step, a symptom severity score is obtained as the product of frequency and intensity (frequency × intensity). In a second step, this product is recoded according to the original validation procedure as follows: 0 = 0; 1–2 = 1; and 4 = 2. In a third and final step, the recoded severity scores of the 16 symptoms are summed to obtain the total CVS-Q score.

According to the established cut-off, total scores ≥ 6 points indicate the presence of CVS and allow participants to be categorized into two groups (“without CVS” vs. “with CVS”), while also providing a continuous measure of symptom severity. In the present study, the CVS-Q was used as a standardized and validated measure to estimate the potential effects of AR exposure on students’ digital visual health and visual fatigue. Authorization for the use and sublicensing of the CVS-Q questionnaire is provided in Supplementary File S2.

2.3. Procedure

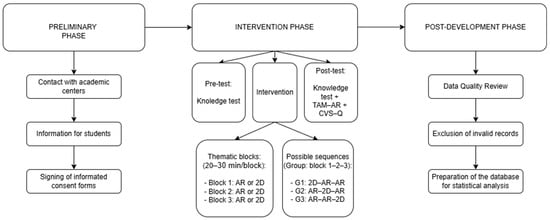

The study was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the University of Burgos (IR 34/2023) and was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki. Data collection took place between September 2024 and January 2025 at the participating centres. All intervention sessions were delivered by a researcher external to the centres, with specialized training in the subject matter and experience in the educational use of augmented reality. The complete procedure is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic overview of the study procedure and AR/2D sequences.

2.3.1. Preliminary Phase: Recruitment and Inclusion Criteria

A convenience sampling approach was employed. Eighteen educational centres from the autonomous communities of Castilla y León, La Rioja, and País Vasco were initially invited via institutional email. Seven centres agreed to participate; however, one was excluded prior to the start of fieldwork for failing to meet the established organizational requirements. Consequently, the study was ultimately conducted in six state-run public centres. Following institutional acceptance, students were informed about the voluntary nature of the study, the confidentiality of the data, and their right to withdraw from the research at any time without academic consequences. Participants (and, where applicable, their legal guardians) provided written informed consent before any measurements were initiated. No intervention session commenced until submission and correct completion of the consent forms had been verified.

Inclusion criteria were: (a) enrolment in the corresponding vocational training programme; (b) provision of written informed consent (by the student or, for minors, by their legal guardian); (c) attendance of at least 90% of the total duration of the intervention sessions; and (d) where applicable, adequate corrected visual acuity for work involving screens. Exclusion criteria comprised: (a) presence of acute or untreated ocular pathology; (b) active migraine; (c) a history of severe cybersickness; or (d) refusal to participate in the study.

2.3.2. Intervention Phase

The interventions were conducted in sessions of approximately 120 min, structured to promote both the acquisition of tool-use skills and the learning of curricular content. All activities took place in the group’s regular classroom during instructional hours and were supervised by the principal investigator and the teacher responsible for the student group. Each session followed the structure outlined below:

- Introduction: presentation of the activity’s objectives; explanation of the technology employed (AR or 2D materials); instructions for use; and basic ergonomic guidelines for visual care during work with screens and AR, with an approximate duration of 5 min.

- Pre-test phase: administration of a knowledge test to assess the level of prior knowledge across the three thematic blocks. The test was administered in paper-based format, individually and in person in the classroom, under the direct supervision of the external researcher and the teaching staff, thereby ensuring a controlled environment with no access to supporting materials, and with an approximate duration of 10 min.

- Development of the thematic modules: sequenced implementation of the three content blocks: (1) healthy dentition and dental units; (2) prevention and identification of carious lesions; and (3) pain management and control. Each block had an approximate duration of 20–30 min.

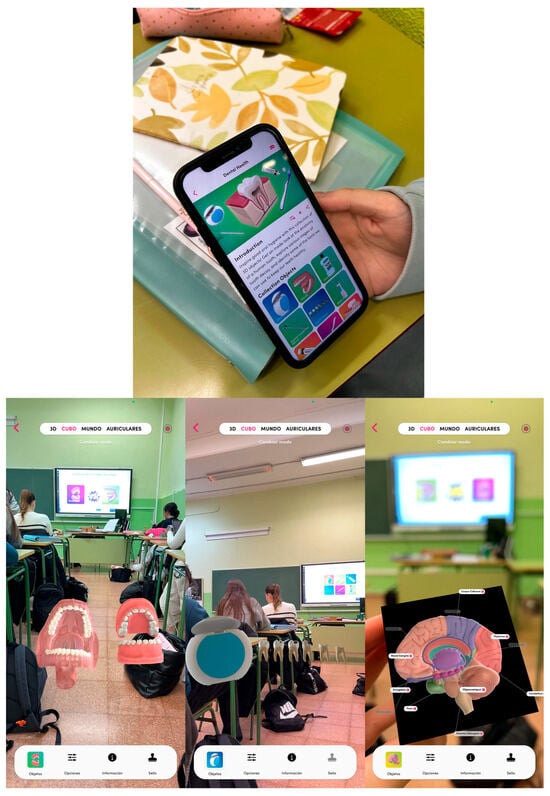

In the AR condition, the Merge Object Viewer application (Merge Labs, Inc., San Antonio, TX, USA) [51,52], was used, integrated into the “Merge EDU” educational platform [53]. It is an AR application for Android [51] and iOS [52] that enables students to explore interactive digital 3D models superimposed onto the physical environment, using smartphones or tablets in conjunction with a Merge Cube [54].

The intervention was implemented under real classroom conditions. Accordingly, students used the mobile devices available at their respective educational centres, which resulted in a heterogeneous set of devices rather than a single standardized model. The devices consisted of smartphones and tablets manufactured by major vendors (e.g., Apple and Android-based manufacturers), including iPads (7th generation or newer), iPhones (iPhone SE or newer), and Android smartphones and tablets released within approximately the previous four years.

All devices ran iOS (version 14 or later) or Android versions current at the time of the study (2023–2025), met the minimum technical specifications defined by the developer of the Merge Object Viewer application, including a rear-facing camera, touchscreen interface, at least 2 GB of RAM, and sufficient processing capability to render real-time 3D content [55].

The AR intervention was conducted under an institutional educational licence for the Merge EDU platform, which provided full access to all three-dimensional content during the study period. This licence was active for the entire duration of the intervention. As licensing terms, costs, and subscription periods are subjects to institutional agreements and may vary across context and over time, specific pricing details are not reported.

To facilitate replicability, the AR content used in this study can be independently accessed by external users through the Merge Object Viewer application within the Merge EDU platform, subject to current availability and licensing conditions. While full access to the instructional content requires a paid educational subscription, a limit subset of the three-dimensional models employed in this study could be explored without a paid licence after user registration. Specifically, within the “Human Anatomy” collection, the objects “Brain Anatomy” and “Human Teeth” were available for visualization, allowing other researchers or educators to experience representative elements of the AR content using compatible devices and a Merge Cube. Also, the template associated with the Merge Cube–based AR activity is provided in Supplementary File S3.

Sessions were conducted with the full cohort in the regular classroom. Students worked in small groups of 2–3 per device (smartphone or tablet), jointly exploring the AR models and collaboratively discussing responses to the proposed tasks under teacher guidance. During the activities, students interacted with the AR objects via touch gestures (rotation, zoom, and translation), enabling examination of dental, oral, and neural structures from multiple perspectives and viewing distances. The AR content was selected from scenes and collections of 3D objects available in Merge Object Viewer, specifically from the “Dental Health” and “Anatomy of the Brain” thematic collections by Merge EDU, which are accessible through a paid subscription and licence [56]. The “Dental Health” collection comprises anatomical models of the oral cavity, as well as models of human teeth presented in multiple views and morphologies. These include healthy teeth and teeth affected by caries at different anatomical sites and with varying degrees of involvement, together with representations of oral-hygiene instruments, orthodontic examples, and basic clinical instrumentation. The “Anatomy of the Brain” collection includes neuronal anatomical models depicting the orofacial connectivity and innervation pathways involved in pain control. On the basis of these resources, the three content blocks described above were defined. Figure A2 in Appendix D presents several images illustrating their use in AR.

In the control condition, a traditional instructional methodology was implemented using 2D materials (plates, diagrams, printed or projected images, and explanatory texts) covering the same theoretical content as the AR scenes; thus, the primary difference between conditions lay in the format and modality of presentation (2D vs. AR). The baseline 2D instructional materials used is provided in Supplementary File S1. The contents were used in a homogeneous manner across all groups, ensuring that the visual material and the associated tasks were comparable among participants.

The participating classrooms were randomly assigned to three AR/2D sequencing patterns: 2D–AR–AR, AR–2D–AR, and AR–AR–2D. Throughout the manuscript, we refer to these conditions as the sequencing groups G1, G2, and G3, respectively.

- 4.

- Final phase: At the conclusion of the instructional blocks, a brief guided reflection was conducted with the students regarding their learning experience with and without AR. Subsequently, students individually completed, in paper-based format and in the classroom, the post-test knowledge assessment, the CVS-Q, the TAM–AR questionnaire and a final open-ended question eliciting comments and suggestions related to the AR experience. Administration of all instruments was carried out under the supervision of the external researcher and the teaching staff, thereby ensuring adherence to the instructions and the allotted response time (approximately 20 min).

2.3.3. Post-Development Phase

After data collection, the records were reviewed to identify incomplete responses, implausible response patterns, or noncompliance with the inclusion criteria (e.g., insufficient attendance or questionnaires that were clearly completed incorrectly). Scores that did not meet the predefined quality criteria were excluded prior to statistical analysis. Before conducting inferential analyses, a preliminary exploration of the database was performed to detect data-entry errors, outliers, and missing data. Cases that failed to meet the previously established quality criteria (e.g., incomplete questionnaires or implausible responses) or that exhibited missing data on the variables involved in a given analysis were excluded from that specific analysis and treated as missing. Missing values were coded as “.” and handled as missing data, with no imputation procedures applied.

2.4. Data Analysis

Data analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 29.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The statistical significance level was set at p < 0.05, and all tests were two-tailed.

Prior to inferential modelling, variable distributions and the presence of outliers were explored using descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, frequencies, and percentages) for the sociodemographic variables and for all instruments. Given the sample size (N = 321), ANOVA was assumed to be robust to moderate violations of the normality assumption. Homogeneity of variances was assessed using Levene’s test, and homogeneity of covariance matrices was assessed using Box’s M test. In all cases, these tests were non-significant (p > 0.05); therefore, the assumptions required for ANOVA were considered satisfied.

To address RQ1, three 2 × 2 mixed factorial ANOVAs were conducted, one for each content block of the knowledge test (dentition, cariogenesis, and pain). In each model, the within-subject factor was measurement time (pre-test vs. post-test), and the between-subject factor was the methodology used in that block (AR vs. 2D), such that the AR condition was treated as the experimental group and the 2D condition as the control group. The dependent variable in each analysis was the total knowledge score for the corresponding block. Main effects of time and group, as well as the time × group interaction, were examined; for significant interactions, simple effects were probed (pre–post changes within each condition and between-group differences at each measurement occasion).

To address RQ2, Pearson’s chi-square test was applied to the contingency table crossing the AR/2D sequencing pattern (G1, G2, G3) with the presence/absence of CVS, with Cramer’s V reported as the effect size index.

Finally, to address RQ3, descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, and possible score range) were computed for scores on the five TAM-AR dimensions and for CVS-Q scores. In addition, as complementary analyses, univariate ANOVAs were performed to examine potential differences in TAM–AR dimension scores and in the total CVS-Q score as a function of the AR/2D sequencing pattern (G1, G2, G3), using these scores as dependent variables and the AR/2D sequencing pattern as the between-subjects factor. When the omnibus effect was significant, Scheffé post hoc tests were conducted and effect size (η2) was reported.

For the qualitative component, responses to the open-ended question included at the end of the TAM–AR were analyzed using descriptive content analysis. Each comment was treated as an independent unit of analysis. Through repeated reading of the responses, a two-level coding scheme was developed: (a) an overall appraisal of the experience (positive, negative, or neutral/no substantive contribution) and (b) several specific themes related to perceived usefulness for learning, appraisal of the technology, instructor performance, perceived technical limitations, language difficulties, proposals for functional improvement, potential distraction, and physical discomfort. Comments were coded by a primary coder and subsequently reviewed by another team member, who checked the consistency of category assignment. Coding was conducted using ATLAS.ti 9 qualitative analysis software, retaining the assignment of each comment to the sequencing group (G1, G2, G3). A single comment could be assigned to more than one category. No quantitative inter-rater agreement index was computed; discrepancies were resolved through discussion and consensus among team members. Subsequently, absolute frequencies and percentages for each category were calculated for the full set of comments and, exploratorily, by group. Qualitative findings were used complementarily to contextualize and interpret the quantitative results regarding AR acceptance and digital visual health.

2.5. Study Design

A counterbalanced quasi-experimental design with an equivalent control group was employed, framed within a mixed-methods approach that incorporated an embedded descriptive qualitative component. The participating classrooms were randomly assigned to three sequencing groups (G1, G2 and G3) according to their order of participation and availability. Each group defined the combination of methodologies (AR or 2D) implemented across three consecutive thematic blocks: G1 = “2D–AR–AR”, G2 = “AR–2D–AR”, and G3 = “AR–AR–2D”. The 2D methodology corresponded to traditional instruction based on printed materials and two-dimensional resources, whereas the AR condition entailed use of the tool described in the Materials section. Table 1 summarizes the sequence design by group and content block.

Table 1.

Design of the instructional sequences by group and content block. AR = augmented reality condition using the Merge Object Viewer; 2D = conventional two-dimensional instructional materials. Block 1: healthy dentition and tooth anatomy; Block 2: prevention and identification of carious lesions; Block 3: pain management and basic clinical procedures.

Accordingly, within each thematic block, two methodological conditions (AR vs. 2D) were compared between distinct subsamples of students. For instance, in the first content block, group G1 worked with the 2D methodology, whereas groups G2 and G3 used AR; in the second block, G2 worked with 2D and G1 and G3 with AR; and in the third block, G3 worked with 2D and G1 and G2 with AR. Thus, for each block, the AR vs. 2D comparison was conducted between different participants (between-groups comparison), although each student received AR in two blocks and 2D in one over the course of the intervention, thereby partially counterbalancing exposure to both methodologies.

Consistent with the mixed-methods approach, the embedded qualitative component consisted of a descriptive content analysis of responses to an open-ended question regarding personal experiences and suggestions concerning AR use, included at the end of the TAM–AR. These responses were coded while retaining group membership in the sequencing condition (G1, G2 or G3), enabling descriptive exploration of potential differential patterns in students’ evaluations as a function of the sequence of methodologies received.

2.6. Data and Materials Availability, and the Use of Generative AI

Anonymized and aggregated data generated and analyzed during the current study are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author, exclusively for scientific and academic purposes. Individual-level raw data, including raw knowledge test scores at the participant level, are not publicly shared in order to comply with ethical requirements, data protection regulations, and institutional approvals. However, such raw data may be made available upon justified request and subject to appropriate ethical review and data protection safeguards. The materials used in this study—including the complete template of the knowledge assessment and the implemented versions of the TAM–AR and CVS-Q questionnaires—are also available upon reasonable request, provided that their use does not interfere with ongoing or future instrument-validation processes.

Generative AI tools were used solely for minor language editing. All scientific content and interpretations are the sole responsibility of the authors.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

Of the 321 participants, 274 were women (85.4%) and 47 were men (14.6%), with ages ranging from 15 to 55 years (M = 23.22; SD = 10.12). Regarding educational level, the sample comprised students enrolled in intermediate-level vocational training (n = 264; 82.2%) and advanced-level vocational training (n = 57; 17.8%). By specialty, the distribution was as follows: Auxiliary Nursing Care Techniques (TCAE; n = 264; 82.2%), Dental Hygiene (HB; n = 51; 15.9%), and Pathological Anatomy (AP; n = 6; 1.9%). The provincial distribution was: Burgos (n = 105; 32.7%), Álava (n = 69; 21.5%), La Rioja (n = 56; 17.4%), Salamanca (n = 46; 14.3%), and Ávila (n = 45; 14.0%). Full sociodemographic and educational characteristics are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic and Educational Characteristics of the Sample (N = 321).

3.2. Academic Performance Results (RQ1)

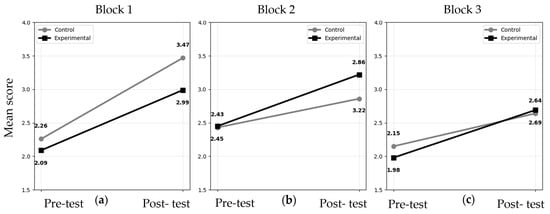

A 2 × 2 mixed factorial ANOVA revealed a statistically significant main effect of measurement time across all three knowledge blocks: Block 1 (healthy dentition and dental anatomy), F(1, 319) = 252.48, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.44 (large effect); Block 2 (prevention and identification of carious lesions), F(1, 319) = 55.05, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.15 (medium-to-large effect); and Block 3 (treatment and pain control), F(1, 319) = 44.94, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.12 (medium effect). As summarized in Table 3, mean scores increased significantly from pre-test to post-test across all three blocks, indicating an overall improvement in academic performance following the intervention, with particularly pronounced gains in Block 1.

Table 3.

RQ1. Descriptive statistics for knowledge scores by content block, measurement occasion (pre-test/post-test), and group (control vs. experimental). 2D = control, AR = experimental; Block 1 = dentition; Block 2 = cariogenesis; Block 3 = pain.

Regarding the main effect of group, a statistically significant difference was observed only in Block 1, F(1, 319) = 7.92, p = 0.005, η2p = 0.02 (small effect), with higher values in the control group (see Table 3). In Blocks 2 and 3, this effect was not significant, F(1, 319) = 3.15, p = 0.077, η2p = 0.01 and F(1, 319) = 0.21, p = 0.649, η2p ≈ 0.00, respectively, suggesting similar performance between groups for these contents when overall means are considered.

Regarding the time × group interactions, as shown in Figure 2, statistically significant effects were found for Block 1, F(1, 319) = 5.35, p = 0.021, η2p = 0.02, and Block 2, F(1, 319) = 4.45, p = 0.036, η2p = 0.01. In both cases, the effect size was small. In Block 1, both the control and experimental groups improved from pre-test to post-test; however, the gain was somewhat larger in the 2D control group (ΔM ≈ 1.21 vs. 0.91 points), which also started from a slightly higher baseline mean. In Block 2, improvement was more pronounced in the experimental group (ΔM ≈ 0.78) than in the control group (ΔM ≈ 0.43). For Block 3, the time × group interaction was not statistically significant, F(1, 319) = 1.61, p = 0.205, η2p = 0.01, indicating a parallel pattern of change across both groups. Appendix B.1 reports the mixed 2 × 2 factorial ANOVAs by content block.

Figure 2.

Changes in theoretical knowledge scores by content block and group (control vs. experimental) between the pre-test and post-test: (a) Dentition; (b) Cariogenesis; (c) Pain.

3.3. Computer Vision Syndrome (RQ2)

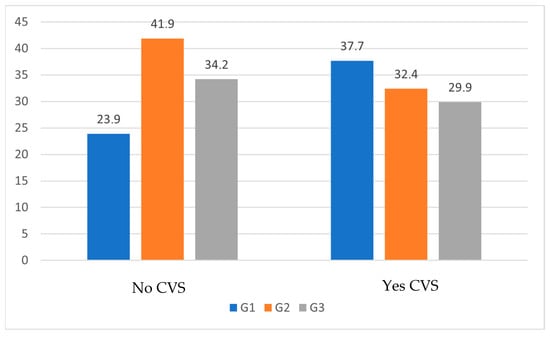

Pearson’s chi-square test indicated a statistically significant association between the AR/2D sequence and the presence of CVS, χ2(2, N = 321) = 6.66, p = 0.036, with a small effect size (Cramer’s V ≈ 0.14). The CVS-Q cut-off used to classify participants as “with CVS” was set at ≥6 points.

As shown in Table 4, overall, 63.6% of participants exceeded the CVS-Q cut-off and were classified as “with CVS,” whereas the remaining 36.4% were classified as “without CVS.” CVS prevalence by sequencing group was 73.3% in Group 1 (2D–AR–AR), 57.4% in Group 2 (AR–2D–AR), and 60.4% in Group 3 (AR–AR–2D). Appendix B.3, Table A6 presents the extended descriptive statistics of the CVS-Q by sequencing group (G1, G2, G3).

Table 4.

RQ2. Prevalence of CVS by group, according to the corresponding AR/2D sequencing pattern (2D–AR–AR, AR–2D–AR, AR–AR–2D).

Figure 3 shows the distribution of the AR/2D sequencing groups within each CVS category. Within the ‘No CVS’ classification, Group 2 accounted for the highest percentage of students (41.9%), followed by Group 3 (34.2%) and Group 1 (23.9%). In contrast, within the ‘Yes CVS’ group, Sequence 1 exhibited the highest percentage of cases (37.7%), ahead of Sequences 2 (32.4%) and 3 (29.9%).

Figure 3.

Percentage of students in each AR/2D sequencing group according to the presence of CVS. G1 = 2D–AR–AR sequence; G2 = AR–2D–AR sequence; G3 = AR–AR–2D sequence.

3.4. Satisfaction, Technological Acceptance of AR, and Students’ Feedback (RQ3)

3.4.1. Quantitative Results of the TAM-AR

First, to address RQ3 regarding AR acceptance, a descriptive analysis was conducted of the dimensions of the TAM-AR questionnaire. As shown in Table 5, the mean scores were above the theoretical midpoint for perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, perceived enjoyment, and attitude toward use, indicating that students rated AR as moderately high in usefulness, manageable, and pleasant, and exhibited an overall positive attitude toward its integration into the training programme. In the dimension of intention for future use, the scores were slightly below the theoretical midpoint, suggesting a moderate intention, closer to a neutral–favourable position than to a rejection of subsequent AR use. Appendix B.2 (Table A5) presents the extended TAM–AR descriptive statistics by sequencing group (G1, G2, G3).

Table 5.

Descriptive Statistics for the TAM–AR Dimensions.

Next, potential differences in AR acceptance as a function of sequencing group were examined (G1: 2D–AR–AR; G2: AR–2D–AR; G3: AR–AR–2D). One-way univariate ANOVAs indicated only a small main effect of sequence on perceived usefulness, F(2, 318) = 3.16, p = 0.044, η2 ≈ 0.02. Mean perceived usefulness scores were slightly higher in Sequence 1 (2D–AR–AR; M = 4.73, SD = 0.92) compared with Sequence 2 (AR–2D–AR; M = 4.40, SD = 1.01), with no significant differences relative to Sequence 3 (AR–AR–2D; M = 4.53, SD = 0.96; Scheffé post hoc test); see Table 6.

Table 6.

Mean scores (SD) on the TAM–AR dimensions and on the CVS-Q, by group and AR/2D sequencing pattern (G1, G2, G3).

3.4.2. Qualitative Results: Students’ Comments

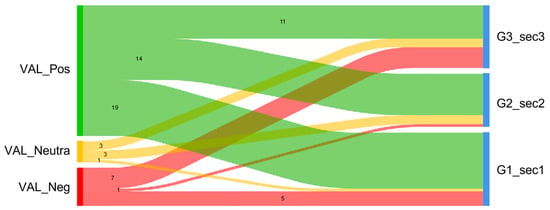

Second, the responses to the open-ended question included at the end of the TAM–AR were examined through a descriptive content analysis. Of the 321 participants, 68 (21.2%) responded to this question: 26 (38.2%) belonged to G1, 16 (23.5%) to G2, and 26 (38.2%) to G3. A total of 64 codable overall evaluations and 88 thematic references were generated. Not all comments yielded a codable overall evaluation; hence, the discrepancy between the number of responses (n = 68) and the number of overall evaluations (n = 64).

- Overall evaluation of the AR experience: Across the qualitative sample, most comments conveyed a favourable assessment of the AR experience. Of the 64 overall evaluations, 44 (68.8%) were classified as positive, 13 (20.3%) as negative, and 7 (10.9%) as neutral or lacking a clear contribution.

Among the positive evaluations, descriptions emphasizing the activity’s interest and clarity were common, such as “it was great, super interesting and very practical and simple. Good explanation of the concepts” (G1) or “really cool; you learn a lot” (G2). Several comments also highlighted that AR is “a good idea that will make it easier for us to study things more quickly” (G1) or “a very necessary activity nowadays… very useful” (G3).

At the opposite end, negative evaluations cantered primarily on technical and usability issues. Some students noted, for example, that “using the app overheats the phone and drains the battery very quickly” (G3), or that “the idea is good but the application does not work well; the device gets very hot and freezes—right now I do not see it as functional at all” (G1). Other comments expressed a more general disappointment with the activity’s format (e.g., “I expected something else; I didn’t love it; it’s not that interesting for me,” G3).

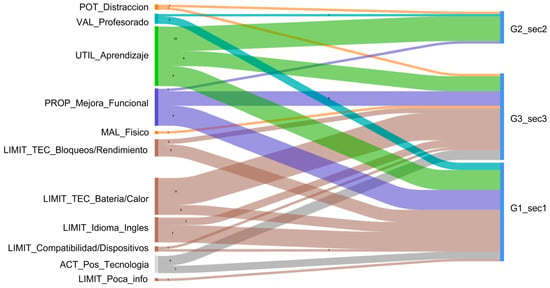

When results were analyzed by AR/2D sequencing pattern, all three groups exhibited a predominance of positive evaluations, albeit with distinct profiles. In G1 (2D–AR–AR), 76.0% of evaluations were positive, 20.0% negative, and 4.0% neutral; in G2 (AR–2D–AR), a very similar pattern was observed (77.8% positive, 5.6% negative, and 16.7% neutral); and in G3 (AR–AR–2D), positive evaluations remained the majority (52.4%), but with a higher relative weight of negative evaluations (33.3%). Indeed, slightly more than half of the negative comments came from this third group. This distribution of evaluations across sequences is visually represented in Figure 4 by means of a Sankey diagram.

Figure 4.

Sankey diagram. Flow of overall evaluations by group. VAL_Pos = positive evaluation; VAL_Neutra = neutral evaluation; VAL_Neg = negative evaluation. G1_sec1 = sequencing group 1 (2D–AR–AR); G2_sec2 = sequencing group 2 (AR–2D–AR); G3_sec3 = sequencing group 3 (AR–AR–2D).

- Specific themes of the AR experience: The thematic analysis identified 88 references distributed across eleven categories (see Table 7). The most frequent theme was perceived usefulness for learning, appearing in 24 comments (27.3%). In these responses, students emphasized that AR helped them to better understand the content, to visualize structures or processes, and to study more efficiently, with remarks such as: “I found it useful for the anatomy topic, since it can be good for learning” (G2), “I find it very useful to use it for studying and to be able to improve” (G1), or “it increases knowledge about various things of interest and they are very useful” (G3).

Table 7. Frequency of specific themes mentioned in open-ended comments, by sequencing group.

Table 7. Frequency of specific themes mentioned in open-ended comments, by sequencing group.

Two clusters of comments occurred with the same frequency (15 references each; 17.0% each): (i) proposals for functional improvements to the application and (ii) problems related to battery consumption and device overheating during the activity. Improvement proposals included suggestions regarding navigation and features, for example: “I would add the option to view several objects in several cubes at the same time… it would be a good option to allow substantial zooming” (G3), “use of the app with virtual reality glasses” (G2), or “they could include an option to change the language to Spanish” (G1). Battery and temperature issues were described in very direct terms: “it consumes a lot of battery quickly and overheats the phone a lot” (G3), “the phone gets hot and uses a lot of battery” (G3), or “the phone heats up; the app freezes and you have to close it and reopen it to make it work” (G3). Alongside these, additional references were recorded concerning language-related difficulties (interface or elements in English; 10 references, 11.4%), such as: “it’s very good, but it needs to be in Spanish because it limits you a lot and it’s not fair for people who don’t know [English]” (G1) or “it should be in Spanish; it heats up the phone a lot and uses a lot of battery” (G3); performance failures or freezes of the application or the device (7 references, 8.0%), for example: “the page freezes a lot and you have to exit and go back in” (G1) or “the app is in English, it doesn’t work, it freezes, and there is little information” (G1); and incompatibilities with certain devices (2 references, 2.3%), such as: “that it can be used better on all devices” (G3). Considered jointly, these mentions indicate that approximately one quarter of the analyzed excerpts refer to technical and/or linguistic limitations.

Among clearly positive aspects, beyond usefulness for learning, comments were also identified that valued AR technology as an innovation in itself (7 references, 8.0%), with expressions such as: “it seems like a good idea for people who prefer to study digitally” (G3) or “a different dynamic from what theory is” (G3). In addition, some responses highlighted the instructor’s performance during the experience (4 references, 4.5%), for instance: “very nice. Very clear. Good tools. An enjoyable and fun talk” (G1).

Other less frequent, yet design- and safety-relevant, themes included the potentially distracting nature of AR (2 references, 2.3%), e.g., “I liked it… but I wouldn’t use it to study because I get distracted” (G2), and the emergence of physical discomfort associated with device use (1 reference, 1.1%), where one student noted that “for people with migraines these apps are highly inadvisable (it intensified my pain)” (G3).

The distribution of themes varied according to the AR/2D sequencing pattern. In G2, the vast majority of references focused on usefulness for learning (76.9% of its codes), with very few allusions to technical problems or other issues, suggesting a particularly smooth experience, as illustrated by comments such as “a fun experience facilitating learning” or “none; personal opinion: very useful.” In G1, the thematic repertoire was more heterogeneous: alongside usefulness and improvement proposals, language difficulties and multiple device performance issues emerged strongly. Finally, G3 concentrated most complaints about battery drain and overheating, a substantial portion of references to freezing, and the only explicit mention of physical discomfort, in addition to several improvement proposals and comments on usefulness.

In Appendix C.1 (Table A7 and Table A8), the category system used for the analysis of open-ended comments is presented, including the code and descriptive label, a brief definition, inclusion criteria, exclusion criteria, and illustrative examples of comments. Figure A1 presents the Sankey diagram corresponding to the specific categorization.

In summary, students report high levels of satisfaction with and acceptance of AR, while also indicating the need for technical improvements, linguistic support, and functional adjustments to the tool.

4. Discussion

Based on the results, the main findings are presented below, together with the characteristics of the study sample, the study’s limitations, and directions for future research.

4.1. Characteristics of the Sample

The study involved vocational healthcare students from six institutions across five Spanish provinces, providing geographical diversity but not national representativeness. The predominance of women and intermediate-level vocational students, particularly Nursing Care Assistant Technicians, constrains generalizability to other educational profiles. Nevertheless, the relatively large sample size (N = 321) and the multicentre design enhance the robustness of the findings and their applicability to comparable vocational training contexts. This profile aligns with previous studies in health and dental education, including nursing and medicine programmes, which also report a predominance of female students [4,9,13,14,16,25,26,37,42,57,58,59,60].

4.2. Academic Performance (RQ1)

In response to RQ1, both 2D and AR conditions yielded significant learning gains across all content blocks, underscoring the importance of structured instructional design aligned with learning objectives. Consistent with previous reviews, immersive technologies tend to produce learning outcomes comparable to, or only moderately superior to, traditional approaches when embedded within well-designed pedagogical frameworks [3,4,5,6,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,21,24,48].

In Block 1 (dentition), the 2D group achieved higher baseline and post-intervention scores, as well as greater learning gains. From the perspective of meaningful learning theory, this pattern highlights the role of prior knowledge [19]. Additionally, Cognitive Load Theory provides a complementary explanation: for relatively simple, static identification tasks with high familiarity, 2D representations may suffice, whereas handheld AR may introduce extraneous cognitive load related to object manipulation, visuospatial coordination, and divided attention. Such demand is consistent with the Split-Attention Effect, potentially interfering with performance rather than enhancing learning [20,21,22,23].

In Block 2 (cariogenesis), learning gains were greater in the AR condition among students with comparable baseline levels suggesting a modality-specific advantage. AR appears particularly beneficial for content that involves three-dimensional or dynamic processes that are difficult to visualize mentally, as manipulable 3D models can reduce intrinsic cognitive load by externalizing spatial relationships and supporting schema construction [4,5,6,13,14,15,24]. Evidence from mobile AR application in histology and related domains supports this interpretation [60].

In Block 3 (pain management), no significant differences emerged between modalities. The length and structure of the session (≈120 min), likely increased cognitive load and fatigue, potentially masking AR-specific advantages toward the end of the intervention. Previous research indicate that motivational and engagement effects of AR and gamification may attenuate under task demands or without explicit self-regulation strategies [9,21,22,23].

Overall, AR should not be viewed as a universally superior solution; but rather as an instructional tool whose effectiveness depends on content complexity, learners’ prior knowledge, and instructional design [3,4,5,6,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,19,20,21,24,48].

4.3. Exposure Sequences and CVS (RQ2)

Regarding RQ2, AR/2D sequencing was associated with differences in the prevalence of CVS-compatible symptoms, with the alternating AR-2D-AR sequence showing the lowest prevalence. This finding aligns with prior studies reporting high CVS prevalence among students with intensive screen use, which often exceeds 70% when specific instruments such as the CVS-Q are employed [18,27,28,29,34]. Importantly, CVS was assessed at a single post-intervention time point; therefore, results reflect prevalence rather than the incidence, and causal attribution to AR exposure cannot be established [12,36,37]. Unlike head-mounted displays (HMDs), where visual fatigue is primarily associated with vergence–accommodation conflicts, handheld mobile AR introduces distinct ergonomic demands related to short viewing distance, sustained device and cube holding, upper-limb posture, and continuous visuomotor coordination.

Alternating AR and 2D modalities may help distribute visual and cognitive load by introducing ‘micro-pauses’ in visually demanding tasks. From the standpoint of visual ergonomics and cognitive load theory [28,30,32,34,36], such alternation, together with scheduled breaks may mitigate visual fatigue [20,23]. Although the cross-sectional, self-reported design limits causal inference, a common limitation in CVS research findings support the incorporation of digital ergonomics and safe-by-design principles into AR/XR educational intervention [1,2,4,5,6,7,9,10,11,12,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,38].

4.4. Satisfaction, Technological Acceptance of AR, and Student Feedback (RQ3)

In RQ3, TAM–AR scores indicated a high level of acceptance of AR: perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, enjoyment, attitude, and behavioural intention to use were all above the theoretical midpoint. This pattern is consistent with TAM-based evidence in AR/XR, where usefulness, ease of use, and enjoyment predict intention for future use [3,8,21,22,23,50], and with broader XR adoption research emphasizing institutional support, resources, and faculty training [1,2,7,8]. In health sciences and dentistry, immersive technologies [4,5,6,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,24,25] been applied across multiple learning domains and specialities, often improving motivation and perceived usefulness [16,26,48,49,57,58,59,60,61]. Our findings suggest that AR is perceived as relevant for oral health education.

Qualitative feedback reinforced these results. Most comments described the experience as useful, engaging, and easy to use, whereas a smaller proportion reported technical limitations (e.g., overheating, battery drain, instability, cube recognition) and the lack of a fully Spanish-language version. These concerns align with prior work highlighting the importance of infrastructure, accessibility, and linguistic localization for the sustainability of XR experiences [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,10,11,12,13,14,21,25]. Comments also reflected sequence-specific perceptions: “AR–2D–AR” was described as more balanced, while “AR–AR–2D” prompted more negative evaluations and technical complaints, consistent with the CVS findings. Although reports of distraction or physical discomfort were infrequent, a few students noted that AR could hinder prolonged study or exacerbate symptoms in cases of migraine or visual sensitivity, in line with evidence on digital visual fatigue [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38]. Notably, many criticisms were framed as improvement suggestions (e.g., adding more objects, integrating with AR/VR headsets, completing translation), which is consistent with recommendations supporting co-design with students and faculty to optimize usability and institutional acceptance [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,11,12,13,14,21,25].

Overall, triangulation of quantitative and qualitative data indicates that AR is well accepted and perceived as pedagogically useful; however, effective implementation requires attention to the technical, ergonomic, and contextual factors identified by learners.

5. Conclusions

This study examined the impact of an AR tool based on three-dimensional models, compared with conventional 2D resources, on theoretical knowledge performance in basic dentistry, digital visual health, and technology acceptance among vocational healthcare students. Overall, the intervention was associated with learning gains across the three instructional blocks, and AR provided added value primarily when applied to content with greater spatial or procedural complexity and when baseline knowledge levels were comparable between groups. By contrast, 2D materials proved equally effective—or even more advantageous—when students had an established conceptual foundation and bidimensional representations were sufficient to support understanding.

The findings further suggest that the AR/2D sequencing was related to the presence of computer vision syndrome (CVS) symptoms, indicating that not only total exposure time matters, but also how exposure is distributed and alternated across modalities. This underscores the need to incorporate visual ergonomics and digital eye health safeguards into the design of AR-based educational experiences.

Finally, the high level of technology acceptance, together with predominantly positive qualitative feedback, indicates that AR is perceived as a useful, motivating, and integrable tool within vocational healthcare education. In this context, AR emerges as a complementary resource, particularly relevant for teaching basic dentistry and oral health modules in which three-dimensional visualization offers clear pedagogical benefits.

5.1. Study Limitations

These conclusions should be interpreted in light of several limitations. First, the study employed a quasi-experimental design with naturally classroom-based groups and convenience sampling, without individual random assignment or blinding. Allocation to the experimental conditions was performed at the classroom level, which may have introduced cluster-related effects. As a result, unmeasured classroom-level variables (such as group dynamics, baseline academic climate, instructor-student interaction patterns, peer influence, or subtle differences in instructional context), could have contributed to between-group differences independently of the instructional modality (AR vs. 2D). Although the study design sought to mitigate this risk through counterbalanced sequencing and standardized procedures, the absence of individual-level randomization limits causal inference and should be taken into account when interpreting the findings. In addition, students were aware of whether they were using AR or 2D materials, which may have introduced expectancy and potential novelty-related influences. Furthermore, the sample was restricted to vocational healthcare students from six Spanish institutions, predominantly women and largely enrolled in intermediate-level training programmes. Consequently, the generalizability to other educational levels, disciplines, or contexts should be approached with caution.

Second, the intervention was delivered in a single prolonged session (approximately 120 min), which may have increased cognitive and visual fatigue.

Third, learning outcomes were assessed using an ad hoc knowledge test, specifically developed for this study and aligned with the official curriculum and learning objectives; however, the instrument has not yet undergone comprehensive psychometric validation. In particular, formal indicators of internal consistency (e.g., Cronbach’s alpha) and empirical evidence of content validity based on expert panel evaluation were not established prior to its use. While the test was carefully constructed to cover the targeted content domains and item formats, the absence of formal reliability and validity analyses constitutes a methodological limitation and should be considered when interpreting the magnitude and precision of the observed learning effects. Future research should prioritize the systematic psychometric validation of this instrument to strengthen the robustness and replicability of the findings.

Fourth, CVS was assessed using the CVS-Q at a single time point. As a result, the findings reflect the prevalence of symptoms compatible with CVS at the time of assessment rather than the incidence of new intervention-induced cases. This cross-sectional approach precludes the analysis of symptom trajectories and limits causal interpretation regarding the relationship between AR exposure and visual fatigue. Additionally, potential confounding factors such as prior visual health status, sleep patterns, or screen exposure outside the classroom could not be controlled. Longitudinal designs with repeated measurements before and after exposure would be required to more accurately assess incidence and temporal dynamics of CVS symptoms.

Finally, the AR experience was based on one mobile application and on basic oral health content; consequently, the results cannot be directly extrapolated to other devices (e.g., head-mounted displays), haptic simulators, or additional clinical domains without further empirical validation.

5.2. Future Research Directions

Future research should incorporate multiple shorter, distributed sessions to examine learning and visual fatigue trajectories over time and to evaluate medium- and long-term retention. It is also a priority to validate the knowledge assessment instrument (reliability, construct validity, and sensitivity to change) and to complement it with measures of practical performance (procedural skills, clinical simulations, interprofessional competencies).

Moreover, studies should include repeated CVS measurements and add objective indicators of visual fatigue. Another key direction is the systematic comparison of different “doses” and sequences of AR versus 2D exposure, incorporating concurrent measures of performance, cognitive load, and visual health, and testing designs with scheduled breaks or structured alternation patterns. Finally, replication and extension across additional content areas (e.g., oral histology, surgery, psychomotor training) and across platforms and immersion levels is warranted, integrating principles from instructional design, technology acceptance models, and recommendations in visual ergonomics and digital ethics.

5.3. Applications for Teaching

From an applied standpoint, the results support integrating AR not as a substitute for 2D resources, but as a strategic complement. In educational practice, this entails (a) prioritizing AR for content with high spatial/procedural demands (complex anatomy, three-dimensional relationships, operational sequences), (b) retaining 2D materials to consolidate conceptual foundations when bidimensional representations are sufficient, and (c) designing blended instructional pathways with explicit sequencing criteria (i.e., specifying what is best learned with AR versus 2D).

Responsible implementation additionally requires explicit digital visual hygiene guidelines (planned alternation, breaks, appropriate lighting, and viewing distance), alongside robust instructional design, adequate infrastructure, and learner guidance to minimize adverse effects and maximize pedagogical impact. Taken together, this work provides evidence to inform a pedagogically justified and sustainable adoption of AR, particularly within vocational healthcare training related to oral health.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app16031269/s1 Supplementary File S1: Baseline 2D instructional materials used in the control condition (PDF); Supplementary File S2: Authorization for the use and subli-censing of the CVS-Q questionnaire (PDF); Supplementary File S3: Template associated with the Merge Cube–based AR activity used in the intervention (PDF).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C.S.-M. and G.P.-L.-d.-E.; methodology, M.C.E.-L.; software, L.A.-G.; Writing—original draft preparation, G.P.-L.-d.-E.; writing—review and editing, M.C.S.-M., M.C.E.-L., L.A.-G. and G.P.-L.-d.-E.; visualization, G.P.-L.-d.-E.; supervision, M.C.S.-M., M.C.E.-L. and L.A.-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of University of Burgos (approval number IR 34/2023, date of approval: 1 November 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to the embargo of PhD dissertation.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express their most sincere gratitude to all participants in this study for their time, commitment, and invaluable contributions. The authors also acknowledge the financial support provided through the Predoctoral Research Staff Recruitment Grants (PREDOC), co-financed by the European Social Fund Plus (ESF+) (2023). During the preparation of this manuscript, generative AI tools (Chat GPT-5.2, Open AI; Perplexity) were used exclusively for minor language editing. All scientific content and interpretations are the sole responsibility of the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AR | Augmented reality |

| 2D | Two-dimensional resources or materials |

| 3D | Three-dimensional models |

| AR/2D | Combination or sequencing of activities using augmented reality and 2D materials |

| 2D–AR–AR | Block-based AR/2D sequencing pattern: first block using 2D materials, and the second and third blocks using AR |

| AR–2D–AR | Block-based AR/2D sequencing pattern: first block using AR, second block using 2D materials, and the third block using AR again |

| AR–AR–2D | Block-based AR/2D sequencing pattern: first and second blocks using AR, and the third block using 2D materials |

| XR | Extended reality (umbrella term for immersive technologies: AR, virtual reality, mixed reality, etc.) |

| CVS | Computer Vision Syndrome (set of digital visual fatigue symptoms associated with screen use) |

| CVS-Q | Computer Vision Syndrome Questionnaire: standardized questionnaire to detect and quantify computer vision syndrome |

| TAM | Technology Acceptance Model: model of technology acceptance |

| TAM–AR | Version of the Technology Acceptance Model adapted to augmented reality (AR technology acceptance model) |

| G1 | Sample Group 1, assigned to the 2D–AR–AR sequence |

| G2 | Sample Group 2, assigned to the AR–2D–AR sequence |

| G3 | Sample Group 3, assigned to the AR–AR–2D sequence |

| TCAE | Nursing Auxiliary Care Technician (intermediate vocational education and training programme) |

| HB | Oral Hygiene (higher vocational education and training programme) |

| AP | Pathological Anatomy (higher vocational education and training programme) |

| HMD | Head-Mounted Display: head-worn virtual/mixed reality headset |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance: statistical test used to compare means across groups |

| N | N Sample size (number of participants) |

| M | Arithmetic mean (average) |

| SD | Standard deviation (of the scores) |

| 95% CI | 95% confidence interval |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences: statistical analysis software (IBM SPSS Statistics) |

| IA | Artificial intelligence |

| iOS | Apple iOS mobile operating system |

| EDU | Abbreviation of Education; in the text, the name of the educational platform “Merge EDU” |

Appendix A. Knowledge Test

Structure and Objectives of the Knowledge Test

The knowledge test employed in this study was developed ad hoc and comprised 15 items distributed across three content blocks: (1) human dentition, (2) cariogenesis, and (3) pain. Each block included five question formats (short-answer, single-choice, multiple-choice, true/false, and ordering), aligned with specific learning outcomes of the module Basic Techniques for Dental Assistance. Table A1 summarizes, for each item, the corresponding content block, item type, a brief description of the prompt, and the associated learning objective, in order to facilitate comprehension and enable potential replication of the study without interrupting the flow of the main text. The full version of the test will be made available once it has been validated.

Table A1.

Summary of the items in the knowledge assessment and their associated learning objectives.

Table A1.

Summary of the items in the knowledge assessment and their associated learning objectives.

| Content Block | Item | Item Type | Item Summary | Linked Learning Objective |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Human dentition | 1 | Short answer | Eruption age of the first incisor | Recognize the basic chronology of dental eruption (primary incisors). |

| 2 | Single choice | Soft tissue with blood vessels and nerves | Identify the dental pulp as the vascularized and innervated soft dental tissue. | |

| 3 | Multiple choice | Periodontal (non-dental) tissues | Distinguish and name the main periodontal tissues as opposed to dental tissues. | |

| 4 | True/False | Function of the canines | Describe the main function of the canines in mastication. | |

| 5 | Ordering | Chronology from 6–18 years (eruption and replacement) | Correctly order the main milestones in dental chronology between 6 and 18 years of age. | |

| 2. Cariogenesis | 6 | Short answer | Dental caries as a reversible/irreversible lesion | Understand the (ir)reversible nature of dental caries and justify it in terms of tissue involvement. |

| 7 | Single choice | Factor that does NOT influence caries | Distinguish protective factors and risk factors in the development of dental caries. | |

| 8 | Multiple choice | Materials that prevent carious lesions | Identify the materials and resources used in the prevention of carious lesions. | |

| 9 | True/False | Pain when caries reaches dentine | Relate the depth of caries (dentine involvement) to the onset of pain. | |

| 10 | Ordering | Stages of progression of a carious lesion | Sequence the stages of progression of a carious lesion from the earliest enamel changes to pulpal involvement. | |

| 3. Pain | 11 | Short answer | The trigeminal nerve as the fifth cranial nerve | Correctly identify the cranial nerve number of the trigeminal nerve and its role in orofacial sensation. |

| 12 | Single choice | Anatomical origin of the trigeminal nerve | Locate the anatomical origin of the trigeminal nerve within the central nervous system. | |

| 13 | Multiple choice | Types of anaesthesia in dentistry | Recognize the main types of anaesthesia used in dental practice | |

| 14 | True/False | Use of general anaesthesia in dentistry | Differentiate general anaesthesia from other techniques and describe its usual indications in dentistry. | |

| 15 | Ordering | Steps in preparing an anaesthetic field | Appropriately sequence the steps for preparing an anaesthetic field in dentistry (patient, field, verification, administration). |

Appendix B. Additional Results of the Quantitative Analyses

Appendix B.1. Mixed 2 × 2 Factorial ANOVA by Content Block (RQ1)

Table A2, Table A3 and Table A4 present the full mixed 2 × 2 factorial ANOVA tables for each content block of the knowledge test.

Table A2.

Mixed 2 × 2 factorial ANOVA for Block 1 (healthy dentition and teeth). N = 321. η2p = partial eta squared.

Table A2.

Mixed 2 × 2 factorial ANOVA for Block 1 (healthy dentition and teeth). N = 321. η2p = partial eta squared.

| Effect | Type | df1 | df2 | F | p | η2p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time (pre vs. post) | Within-subject | 1 | 319 | 252.48 | <0.001 | 0.44 |

| Method (AR vs. 2D) | Between-subject | 1 | 319 | 7.92 | 0.005 | 0.02 |

| Time × Method | Within-subject | 1 | 319 | 5.35 | 0.021 | 0.02 |

Table A3.

Mixed 2 × 2 factorial ANOVA for Block 2 (prevention and identification of carious lesions). N = 321. η2p = partial eta squared.

Table A3.

Mixed 2 × 2 factorial ANOVA for Block 2 (prevention and identification of carious lesions). N = 321. η2p = partial eta squared.

| Effect | Type | df1 | df2 | F | p | η2p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time (pre vs. post) | Within-subject | 1 | 319 | 55.05 | <0.001 | 0.15 |

| Method (AR vs. 2D) | Between-subject | 1 | 319 | 3.15 | 0.077 | 0.01 |

| Time × Method | Within-subject | 1 | 319 | 4.45 | 0.036 | 0.01 |

Table A4.

Mixed 2 × 2 factorial ANOVA for Block 3 (treatment and pain control). N = 321. η2p = partial eta squared.

Table A4.

Mixed 2 × 2 factorial ANOVA for Block 3 (treatment and pain control). N = 321. η2p = partial eta squared.

| Effect | Type | df1 | df2 | F | p | η2p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time (pre vs. post) | Within-subject | 1 | 319 | 44.94 | <0.001 | 0.12 |

| Method (AR vs. 2D) | Between-subject | 1 | 319 | 0.21 | 0.649 | 0.00 |

| Time × Method | Within-subject | 1 | 319 | 1.61 | 0.205 | 0.01 |

Appendix B.2. Extended Descriptives of the TAM–AR by Sequencing Group (G1, G2, G3)

Table A5 presents the descriptive statistics by AR/2D sequencing group (G1, G2, G3) for the five dimensions of the TAM–AR.

Scores are expressed on a 1–7 scale, computed as the mean of the items for each of the following dimensions:

- Perceived usefulness: 4 items.

- Perceived ease of use: 3 items.

- Perceived enjoyment: 3 items.

- Attitude toward use: 3 items.

- Intention to use: 2 items (the reverse-coded item was recoded).

Table A5.

Descriptive statistics of the TAM–AR by AR/2D sequencing group (means on a 1–7 scale). Total N = 321; G1 (2D–AR–AR): n = 105; G2 (AR–2D–AR): n = 115; G3 (AR–AR–2D): n = 101.

Table A5.

Descriptive statistics of the TAM–AR by AR/2D sequencing group (means on a 1–7 scale). Total N = 321; G1 (2D–AR–AR): n = 105; G2 (AR–2D–AR): n = 115; G3 (AR–AR–2D): n = 101.

| Dimension (TAM–AR) | Total M (SD) | G1 (2D–AR–AR) M (SD) | G2 (AR–2D–AR) M (SD) | G3 (AR–AR–2D) M (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived usefulness | 4.55 (0.97) | 4.73 (0.92) | 4.40 (1.01) | 4.53 (0.96) |

| Perceived ease of use | 4.98 (1.11) | 5.12 (1.03) | 4.90 (1.14) | 4.91 (1.16) |

| Perceived enjoyment | 4.86 (0.99) | 5.05 (0.75) | 4.75 (1.04) | 4.79 (1.10) |

| Attitude toward use | 4.74 (0.98) | 4.88 (0.87) | 4.66 (1.02) | 4.69 (1.05) |

| Intention to use | 3.59 (1.50) | 3.57 (1.48) | 3.40 (1.52) | 3.81 (1.48) |

Appendix B.3. Extended Descriptives of the CVS-Q by Sequencing Group (G1, G2, G3)

Table A6 summarizes, for each AR/2D sequencing group, the descriptive statistics of the total CVS-Q score and the prevalence of CVS, using the standard cut-off of ≥6 points.

Table A6.

Descriptive statistics of the CVS-Q and prevalence of CVS by AR/2D sequencing group. CVS = computer vision syndrome, defined as CVS-Q ≥ 6.

Table A6.

Descriptive statistics of the CVS-Q and prevalence of CVS by AR/2D sequencing group. CVS = computer vision syndrome, defined as CVS-Q ≥ 6.

| Group (AR/2D Sequence) | n | CVS-Q Total M (SD) | Observed Range | % with CVS (≥6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 321 | 6.64 (2.87) | 1–18 | 63.6% |

| G1 (2D–AR–AR) | 105 | 7.02 (2.90) | 1–15 | 73.3% |

| G2 (AR–2D–AR) | 115 | 6.39 (2.93) | 1–18 | 57.4% |

| G3 (AR–AR–2D) | 101 | 6.53 (2.76) | 2–15 | 60.4% |

Appendix C. Additional Results Complementing the Qualitative Analyses

Appendix C.1. Qualitative Coding Scheme

This appendix presents the category system used for the analysis of students’ open-ended comments regarding the AR activity and the mobile application. For each category, both in Table A7 (global evaluation categories) and Table A8 (specific evaluation categories), the following information is provided:

- Code and descriptive label;

- Brief definition;

- Inclusion criteria;

- Exclusion criteria;

- 1–2 examples of comments (anonymized).

Table A7.

Global evaluation categories.

Table A7.

Global evaluation categories.

| ATLAS.ti Code | Label | Definition | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria | Example Comments (Anonymized) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| “VAL_Pos” | Positive global evaluation | Clearly positive judgements about the experience as a whole | Expressions of general satisfaction (“great”, “very good”, “I liked it a lot”, “highly recommended”, etc.). Comments about the activity or session without relevant criticism. | Comments that are more critical than positive. | “It has been great, super interesting and very practical and simple.”/”Very cool activity and very interesting, to study things… Thank you.” |

| “VAL_Neg” | Negative global evaluation | Clearly negative or disappointed judgements regarding the experience. | Comments such as “I didn’t really like it”, “it was not entertaining”, “I don’t find it functional at all” referring to the activity as a whole. | Cases where criticism is limited to a specific technical failure or ambiguous comments. | “I was expecting something else; I didn’t really like it, it’s not that interesting for me.”/“It was not a very entertaining activity.” |

| “VAL_Neutra/Sin_aporte” | Neutral evaluation/no contribution | Responses without evaluative content or with minimal content. | Responses such as “Nothing”, “Nothing to add”. Courtesy formulas without further information (“Thank you”, “Very good, thanks”, etc.). | Brief comments that nonetheless contain clear content (e.g., “very useful”, “recommended”). | “Nothing.”/“Nothing to add.” |

Table A8.

Specific evaluation categories.

Table A8.

Specific evaluation categories.

| Code | Label | Definition | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria | Example Comments (Anonymized) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| “UTIL_ Aprendizaje” | Usefulness for learning | The app/AR is perceived as a useful aid for studying or learning better. | Explicit mentions that it “helps to learn”, “makes studying easier”, “helps to retain the material better”, “is useful for training/class”. | Comments focused only on how entertaining/original the technology is. | “I think it is a very good option for people who want to study in a clearer and easier way.”/“It was quite interesting; I think it helps a lot with learning.” |

| “ACT_Pos_ Tecnologia” | Positive attitude toward the technology/AR | AR or the app is valued as interesting, enjoyable, or novel. | Comments such as “really cool”, “fun”, “original”, “a very good idea”, referring to the app/AR as a technology. | Comments focused on learning better or centred on the instructor. | “The application was interesting and fun.”/“The activity was really cool and very interesting.” |

| “LIMIT_TEC_ Bateria/Calor” | Problems with battery and heat | Problems related to battery consumption and overheating of the device. | References to “it uses a lot of battery”, “it consumes a lot of battery”, “the battery runs out quickly”, “the phone gets very hot”. | Comments about crashes or freezes without mention of battery/heat, or comments about personal physical discomfort. | “It consumes the battery very quickly and overheats the phone a lot.”/“The phone gets hot and it uses a lot of battery.” |

| “LIMIT_TEC_ Bloqueos/Rendimiento” | Technical freezes and performance issues | Failures in stability and performance: crashes, freezes, restarts, black screen, etc. | Comments where the app “freezes”, “gets blocked”, “doesn’t work well”, “you have to exit and re-enter”, “the cube turns black”, etc. | Comments focused on heating or battery, or on problems tied to a specific device or the cube. | “The application freezes and you have to close it and open it again.”/“The idea is good but the application doesn’t work well and it freezes; right now I don’t find it functional.” |

| “LIMIT_ Compatibilidad/ Dispositivos” | Compatibility and devices | Difficulties linked to the device or the cube (recognition, optimization, uneven functioning). | Comments that it “does not work well on some phones”, “cube recognition fails”, need for it to work better on all devices. | Generic freezes without mention of device/cube, language-related problems. | “It should be possible to use it better on all devices.”/“Overall, the application is very good. Sometimes the cube identification fails; that could be improved.” |

| “LIMIT_ Idioma_Ingles” | Language limitations (English) | Difficulties because the app is in English and not in Spanish or other languages. | Comments that “it is in English”, “it should be in Spanish”, proposals to display names in the selected language, etc. | Proposals to improve functionality without focus on language, difficulties understanding content without mentioning language. | “The problem with the application is that it is in English…”/“It is very good, but it is necessary for it to be in Spanish because that is very limiting and not fair for people who do not know the language.” |

| “LIMIT_Poca_info” | Little information/instructions | Perception that information or explanations are missing within the app. | Explicit mentions of “little information” about its use or content. | Difficulties of use or language-related problems. | “The problem with the application is that it is in English, it doesn’t work, it freezes, and there is little information.” |