Abstract

Seismic vulnerability assessment of reinforced concrete (RC) structures is crucial in earthquake-prone regions to mitigate risks to life and property. This study proposes a systematic three-phase framework for enhanced seismic risk assessment: (1) Automation, (2) Evaluation, and (3) Predictive Modeling. For the Automation Phase, a web-based tool was developed to digitize and streamline the Turkish Rapid Visual Screening (RVS) procedure, eliminating manual calculation errors while improving efficiency. During the Evaluation Phase, we applied this tool to assess 600 buildings, classifying them into four distinct risk categories (no, low, moderate, and high risk) through standardized scoring. Finally, in the Predictive Modeling Phase we conducted correlation analysis to identify key seismic risk factors (e.g., building height showing a strong negative correlation, while soft-story mechanisms and short columns emerged as critical vulnerabilities) and implemented three machine learning models (XGBoost, Random Forest, and AdaBoost) for risk prediction, with XGBoost achieving superior accuracy. The framework’s validation confirmed the web tool’s reliability relative to conventional methods while revealing most buildings as low-risk, demonstrating how this integrated approach—combining automated screening, large-scale assessment, and data-driven prediction—provides a scalable solution for seismic risk mitigation in vulnerable regions.

1. Introduction

Seismic vulnerability assessment of reinforced concrete (RC) structures is indispensable in earthquake prone areas where seismic activity is a hazard to life and property. This is proactive, which makes it important for several reasons. It has a vital role to play in protecting human lives above anything else. By identifying the potential weaknesses of a structure before an earthquake happens, engineers can undertake retrofitting or design modifications necessary to increase the building’s resilience. The catastrophic consequences of seismic events are tragically illustrated by Turkey’s earthquake history, particularly the 1999 İzmit earthquake (Mw 7.4) that claimed over 20,000 lives and caused $30 billion in damages [1], and more recently the 2023 Kahramanmaraş earthquakes (Mw 7.7 and 7.6) that resulted in 50,783 fatalities and the collapse of 36,932 buildings [2,3]. Rapid Visual Screening (RVS) is a simplified methodology for evaluation of the Seismic Vulnerability Index in Reinforced Concrete (RC) structures. This works well for rapid assessment and does not require detailed structural calculations, making it quite convenient, especially in areas that are earthquake prone. The RVS approach aims to capture fundamental building characteristics that are potential performance indicators of buildings during a seismic event. RVS is a valuable method for evaluating seismic and fire risks in RC structures. It offers a swift and practical approach to assess building vulnerabilities and prioritize mitigation strategies [4,5].

Different RVS methodologies have been developed and tested worldwide to address local requirements based on building typology. One widely used method is FEMA P-154, developed by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), which involves trained personnel visually inspecting structures to assess their seismic performance. This method has two levels: Level 1 offers a preliminary assessment, while Level 2 provides a more detailed evaluation for potentially hazardous buildings [6]. Other methods include the Canadian Manual for Screening of Buildings for Seismic Investigation by the National Research Council [7], and Japan’s Seismic Index Method (JSIM), which enables rapid evaluations of seismic safety [8]. New Zealand’s NZSEE methodology uses a two-stage assessment: Initial Assessment Procedure (IAP) and Detailed Seismic Assessments (DSA), classifying buildings as potential EPBs or non-EPBs [9]. The Vulnerability Index Method, developed by Italy’s GNDT and adopted in seven European countries, evaluates damage levels on both city-wide and single-building scales [10]. India’s RVS method, IITK-GSDMA, was developed by the Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur and Gujarat State Disaster Management Authority, adapting FEMA P-154 for RC structures in seismic-prone areas [11]. Greece’s Earthquake Planning and Protection Organization (OASP) published an RVS method in 2000, also derived from FEMA P-154, to identify dangerous buildings in earthquake-prone regions [12]. Europe uses the European Macroseismic Scale (EMS-98), developed by the European Seismological Commission, which replaced the older MSK-64 scale [13]. The RISK-UE project, funded by the European Commission, aimed to develop comprehensive earthquake risk scenarios for European cities, with Working Package 4 (WP4) focused on modern construction vulnerabilities [14].

The Turkish RVS methodology, part of the Earthquake Master Plan for Istanbul (EMPI), was developed by four major Turkish universities at the request of the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality (IMM) [15]. Over time, Turkey has introduced several region-specific RVS methods reflecting its commitment to seismic safety. The METU RVS method offers a simple, fast assessment of urban RC buildings via sidewalk evaluations, using data from 454 buildings damaged in the 1999 Düzce earthquake [16]. The Yakut Method targets low- to mid-rise RC frame buildings, requiring data on concrete strength and ground floor area [17]. The Performance Based Rapid Seismic Assessment Method (PERA) adopts an approach similar to the Turkish Seismic Design Code (TSDC), but significantly shortens the time required for site inspections and streamlines the analysis and evaluation processes [18]. The DURTES method assesses buildings’ seismic safety using two main scores: K1, based on structural strength and materials, and K2, based on the building’s current condition. In fact, the K1 coefficient follows the standards outlined in the seismic regulations, but the K2 coefficient is determined by around 100 characteristics based on the current state of the structure [19]. The Anadolu University Rapid Assessment Method (AURAP) is a modified version of the DURTES method that allows quick, low-cost, and reliable seismic assessment of midrise RC buildings. It is ideal for regions with building types similar to those in Turkey, such as the Balkans, Middle East, and Mediterranean [20].

Conventional RVS methods are now being enhanced with advanced technologies like Artificial Neural Networks, fuzzy logic, and machine learning, supported by big data. Additionally, modern websites and smartphone apps have emerged to streamline RVS applications, enabling real-time data collection and analysis. Several researchers have utilized fuzzy logic to improve RVS methods for seismic assessment. In Greece, Demartinos and Dritsos [21] designed a fuzzy logic-based procedure to classify buildings into five potential damage categories for future earthquakes. Harirchian and Lahmer [22] proposed a novel RVS method employing an Interval Type-2 Fuzzy Logic System (IT2FLS), which allows prioritization of vulnerable buildings for further evaluation while accounting for uncertainty during the assessment process. Allali et al. [23] introduced a fuzzy logic-based approach to evaluate building damage after an earthquake, relying on in situ visual assessments of structural and non-structural components by trained personnel. Tesfamariam and Saatcioglu [24] applied fuzzy inference systems to assess RC buildings using post-earthquake screening data from the 1994 Northridge earthquake. Şen [25] developed a soft computing method based on a Fuzzy Logic Model (FLM) and system theory, categorizing buildings into five hazard levels: “without”, “slight”, “moderate”, “heavy”, and “complete.” Mazumder et al. [26] created a fuzzy synthetic approach for first-level seismic risk assessment of unreinforced masonry (URM) buildings, incorporating fourteen risk factors grouped into five indexes. Similarly, Bektaş et al. [27] proposed a fuzzy logic-based RVS method tailored to accurately assess building characteristics in URM structures. Addressing uncertainty in regions with limited data, Sadrykia et al. [28] developed a fuzzy set theory-based method that tackles the vagueness in existing knowledge regarding seismic risk criteria.

Bektaş and Kegyes-Brassai [29] developed an NN-based RVS technique using post-earthquake data from the 2015 Gorkha event. Similarly, Harirchian and Lahmer [30] employed ANNs to evaluate RC building vulnerability through geometric characteristics. Several researchers have focused on specialized ANN applications: Falcone et al. [31] for retrofitting assessment, Noura et al. [32] for preliminary damage evaluation during surveys, and Özkan et al. [33] for performance prediction of RC frame buildings. The 2015 Gorkha earthquake data was also utilized by Sri Preethaa et al. [34] to develop an ANN model for post-earthquake damage grading.

Bektaş and Kegyes-Brassai [35] proposed a new machine learning-based highly accurate RVS method that can be adopted in other countries for masonry buildings using the post-earthquake building screening data on 273 masonry buildings that were collected after the 2019 Mugello, Italy earthquake. Mangalathu et al. [36] assessed the viability of the quick prediction of the earthquake building loss and damage by employing data from the South Napa Earthquake of 2014 by using advanced machine learning methods including discriminant analysis, K Nearest Neighbor, Decision Tree, and Random Forest. Chaurasia et al. [37] has employed ML algorithms for estimating the extent of damage of buildings due to the 2015 Gorkha, Nepal earthquake. Ghimire et al. [38] examined several spatially distributed seismic damage analysis techniques using machine learning at the regional scale in terms of their efficiency and pertinence. The vulnerability analysis using machine learning (VULMA) system provides an automated vulnerability assessment pipeline based on street-view imagery and geospatial data [39]. The framework consists of four key modules: image acquisition from online street-view services, expert-assisted labeling of structural features, machine learning-based image classification, and vulnerability index computation. This approach demonstrates the potential of computer vision techniques for large-scale building assessments, particularly for historical masonry aggregates where traditional surveys may be challenging. However, the method’s effectiveness depends on image quality, labeling consistency, and the ability to translate visual features into meaningful structural indicators.

Saadati and Moghadam [40] proposed EZRVS as a web application for the online and rapid screening and assessment of concrete buildings based on FEMA P-154. This application is also platform and hardware independent; all of the calculations are performed on the server side, available at http://www.seismohub.com/ezrvs (accessed on 28 January 2025). Using EZRVS, subscribers can easily and rapidly filter buildings using either artificial intelligence or the FEMA P-154 procedure. Kumari et al. [41] proposed an efficient web application using a Django and Gradient Boost Decision Tree (GBDT) trained machine learning model for conducting a quick vulnerability assessment.

Harirchian et al. [42] designed and presented a smartphone application for data collection concerning earthquake hazard safety assessment of buildings, arguing that the application will enhance the speed of assessment and the collection and processing of data online. An android app named RVS_IND App was created by Nanda et al. [43] with the purpose of making RVS more rapid by evaluating the seismic performance of buildings on the visual inspection level.

This study developed a web-based tool for the Turkish RVS method, applying it for the first time to buildings in Northern Cyprus. Utilizing machine learning, this study identified the most significant parameters that contribute to earthquake risk scores, addressing a critical gap in seismic vulnerability assessment and providing valuable tools for risk mitigation.

2. Materials and Methods

In this study, the methodology is based on three major components. First, an internet-based tool was developed that could automate the Turkish RVS procedure to assess seismic performance of RC buildings in a more accurate, user-friendly, and accessible way. Second, 600 buildings were assessed by using the developed tool, where data on key parameters were collected and classified into different risk categories. Consequently, some data analysis was conducted using machine learning techniques to identify important factors influencing earthquake risk scores in predicting the seismic performances of buildings. This integrates the use of automation into data analysis and predictive modeling as a way to come up with efficient and reliable methods of seismic risk assessments.

2.1. RVS Method Description

The Turkish RVS method was selected due to its thorough and organized way of evaluating how likely RC buildings are to be damaged by earthquakes. It starts by giving a building a base score that shows how much risk it has from earthquakes. This base score is adjusted according to various factors that could affect how well the building handles earthquakes. These factors are soft story, short column, heavy overhang, pounding effect, topographic effect, construction quality, and age of the building as shown in Table 1. A soft story configuration means that one floor of a given building is less stiff compared to the other floors. This makes these floors very vulnerable to lateral forces during an earthquake since the stiffness has been reduced [44]. A short column is stiffer than a typical column and is prone to damage or failure under strong earthquakes due to the high shear forces it endures. In RC structures, the short column effect can also result from half-height infill walls, ribbon windows, and the presence of mid-story beams around stair landings [45]. Heavy overhangs reduce earthquake performance, with the presence of extensive closed heavy overhangs significantly impairing the building’s ability to withstand seismic activity [46]. The pounding effect on the surrounding buildings could range from non-structural damage to severe structural damage, and even potentially creeping collapse of the neighboring buildings [47]. The topographic effect makes hill-slope structures with seismic design codes that met current standards insufficient against the intensified earthquake-induced forces, exposing them to hazards [48]. Construction quality is crucial for ensuring effective seismic performance in an RC frame. Poor construction quality, in contrast, has a harmful effect on the seismic behavior of RC structures [49]. Typically, older buildings are unlikely to perform well during earthquakes because past construction methods did not incorporate the seismic detailing required by current building codes [50].

Table 1.

Scoring criteria for the Turkish RVS [51].

The Earthquake Risk Score (E.R.S) is calculated by adding the Base Score (B.S) to the product of the Score reduction value (S.R.V) and the Vulnerability Parameter Multiplier (V.P.M) as shown in Equation (1). The V.P.M. is 1 if the above risk factor is present and 0 if it is not present. For visual construction quality, the V.P.M. is 2 if the construction quality is described as “poor”, 1 if described as “moderate” and 0 if the quality is described as “good” [51].

Table 2 illustrates that buildings with an E.R.S. of less than 30 are deemed to be at high risk. They are categorized as moderate risk if their E.R.S. falls between 30 and 70. Structures with scores ranging from 70 to 100 are considered to be at low risk. Lastly, buildings with an E.R.S. exceeding 100 are classified as having no risk.

Table 2.

Risk status based on the E.R.S. [51].

2.2. Development of the Web-Based Seismic Assessment Tool

The web based application was designed and implemented using Python (version 3.10), HTML5, CSS3, JavaScript (ES6), and the Flask web framework (version 2.2.5); all the coding used the (version 1.85.1). Python was used in the backend and in data manipulation and specifically to calculate the RVS method to define the earthquake risk. The equations and algorithms needed by the RVS methodology to calculate the E.R.S. were implemented with Python. Python was tasked with carrying out these calculations with accuracy while employing the RVS parameters to arrive at the E.R.S. Drawing from this computed score, Python was also used to categorize the building into different risk classes. The frontend user interface of the application was designed with the help of HTML and CSS, which are specifically designed for the RVS assessment. HTML was used to build the framework of the actual web pages such as the RVS questionnaire, the input forms and the results window. CSS was employed in order to enhance the presentation of the RVS questions and the risk assessment results in a similar manner and makes them more accessible. As a result, using HTML and CSS allowed for structuring and imparting information connected with the RVS process, including user’s engagement with the questionnaire and displaying calculated numerical and qualitative risk scores and status. For the development of the backend of the application, Flask was used and it was combined with Python for the implementation of the RVS method. Flask helped to accomplish the RVS algorithm by being responsible for the routing and handling of the inputs received from the HTML forms submitted by the users. It also handled the transfers of data between the frontend and the Python backend, where the RVS calculations were conducted. It was Flask’s responsibility to handle the response data from the RVS questionnaire and the use of the Python code that produced the E.R.S. and then pass the results to the user. JavaScript was used for client side validation of the RVS questionnaire; this made it possible for the program to check if the inputs added by the user were in order before passing them to Flask for processing. JavaScript effectively controlled the dynamic interaction within the RVS questionnaire and also modified the content, providing an instant response according to the users’ inputs. This made it easier to validate and respond in parallel with the frontend so that by the time data related to the RVS assessment was being sent to the backend, it was correctly formatted, and no data were missing.

2.3. Data Collection

Data for the current study were acquired from 600 RC buildings within three major Northern Cyprus cities of Lefkoşa, Girne, and Mağusa, as shown in Figure 1, representing a good spectrum of the scenarios related to seismic hazard variability in Northern Cyprus. Since seismic ground-motion conditions vary through these regions, the resulting data set would strongly support the estimation of earthquake risks for RC buildings. The data collection focused on several key building characteristics, including the number of stories, building age, visual construction quality, and the presence of structural vulnerabilities such as soft stories, short columns, and heavy overhangs, as well as the influence of topographic and pounding effects. These parameters were then inputted into the web-based RVS tool that allowed classification of each building into appropriate seismic risk categories according to established Turkish RVS methodology. For each building, structural features such as soft story, short columns, heavy overhangs, pounding effect, and topographic effect were identified through visual inspection during the RVS process. These features were evaluated based on clear definitions from the Turkish RVS methodology. Additional parameters, such as the number of stories and the age of the building, were also recorded during the field survey. The number of stories was determined through direct visual counting. For building age, the construction year was used if it was visibly marked on the building. In cases where this information was not available on the building, it was obtained by asking the building owners or occupants. Visual construction quality (categorized as poor, moderate, or good) was assessed based on external observations of materials, workmanship, and signs of structural degradation.

Figure 1.

Satellite Imagery of Surveyed Buildings in: (a) Lefkoşa, (b) Girne, and (c) Mağusa [52].

Figure 2 demonstrates samples of the assessed buildings in the three different cities.

Figure 2.

Examples of assessed buildings.

2.4. Machine Learning Approach for Correlation and Predictive Analysis

A model evaluation of risk classification determinants for 600 buildings was performed using machine learning algorithms. The first analysis examined the main risk factors that strongly influenced the risk score through a correlation analysis. The input features included: number of stories and building age (both treated as continuous numerical variables), presence or absence of a soft story, heavy overhangs, short columns, pounding effect, and topographic effect, as well as visual construction quality categorized as poor, moderate, or good. These features were derived from field data collected during screening RVS assessments and standardized visual inspections. Numerical variables such as number of stories and building age were used in their raw form or normalized when required, while binary attributes (e.g., presence or absence of a soft story) were encoded as 0 or 1, and categorical values (e.g., construction quality) were numerically encoded for compatibility with the machine learning models. The research data were split into training and testing sections where 70% of buildings (420) served as the training material and the remaining 30% (180 buildings) acted as the test material. The prediction of risk scores relied upon three machine learning models, comprising Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), Random Forest, and AdaBoost, which effectively identify complex data patterns. XGBoost was trained to minimize some kind of regularized objective function made up of a convex loss function and the penalty scoring function for the difference between predicted outcomes and true labels. The boosting approach used random subsets of data and features in succession, with weights on mispredicted classes increasing with each iteration. This technique has proven successful for a wide array of tasks [53]. XGBoost works by iteratively adding decision trees to correct the errors (residuals) of the previous ones, improving prediction accuracy step-by-step. It uses an additive model, combining multiple weak learners (trees) with weights. In each step, it optimizes an objective function that includes both a loss function (measuring prediction errors) and a regularization term (controlling model complexity), ensuring a balance between accuracy and overfitting [54].

The general function for forecasting at step p is defined in Equation (2):

where represents the learner (decision tree) added at step p, denotes the cumulative prediction up to step p, and represents the cumulative prediction up to step p − 1.

To balance the model complexity and prevent overfitting while maintaining computational efficiency, XGBoost introduces a regularized objective function. This function evaluates the model’s performance by combining a loss function and a regularization term, as shown in Equation (3):

where represents the loss function, which measures the difference between the actual value and the predicted value ; n denotes the number of observations in the dataset; and represents the regularization term for the k-th tree, which penalizes the model complexity.

The regularization term is defined in Equation (4):

where T represents the number of leaves in the tree, denotes the weight (score) of the j-th leaf, controls the minimum loss reduction required to split a leaf node further, and represents the L2 regularization parameter, which helps control overfitting by penalizing large leaf weights.

This formulation ensures that XGBoost optimizes both prediction accuracy and model simplicity, making it highly effective for a wide range of predictive tasks [55].

Random forest operates as a solution to perform both regression and classification problems. RF operates as a supervised learning method that belongs to the bagging method within integrated learning approaches. The algorithm contains multiple decision trees as its core elements [56]. The ensemble learning approach Random Forest merges numerous decision trees through their predictive information to yield a final result. Random Forest operates under two distinct methods according to the targeted regression or classification task type.

The final prediction for regression is defined in Equation (5):

where F(x) represents the final prediction for the input x, ) denotes the prediction of the t-th decision tree, and T refers to the total number of trees in the forest.

The final prediction for classification is defined in Equation (6):

where mode represents the majority vote of the predictions from all trees.

For regression tasks, the final prediction is the average of the predictions from all individual trees. For classification tasks, the final prediction is determined by majority voting, where the most frequently predicted class among all trees is selected as the output [57,58].

The ensemble learning method called AdaBoost (Adaptive Boosting) improves weak learner performance through an iterative process that focuses on examples that the learners misidentify. Through its weighting mechanism, the algorithm joins numerous weak learners that normally consist of decision stumps to create a single robust classifier. All training samples get an initial weight value that is equal at the start of the process. A weak learner trains the weighted dataset at every iteration and provides its weighted error computation. New weights are calculated for the weak learner through an accuracy-based process, which enhances the weights of the accurate learners. The algorithm assigns incremented weights to these misidentified examples to emphasize them during the following algorithm passes. Finally, the strong classifier is formed by aggregating the weak learners’ predictions using weighted voting, as shown in Equation (7):

where sign determines the class label based on the sign of the weighted sum, represents the weight of the t-th weak learner, represents the prediction of the t-th weak learner for input x, and T represents the total number of weak learners.

AdaBoost is particularly effective for binary classification tasks and is widely recognized for its ability to transform weak learners into a highly accurate ensemble model [59].

3. Results

3.1. Design and Implementation of the RVS Method Web Platform

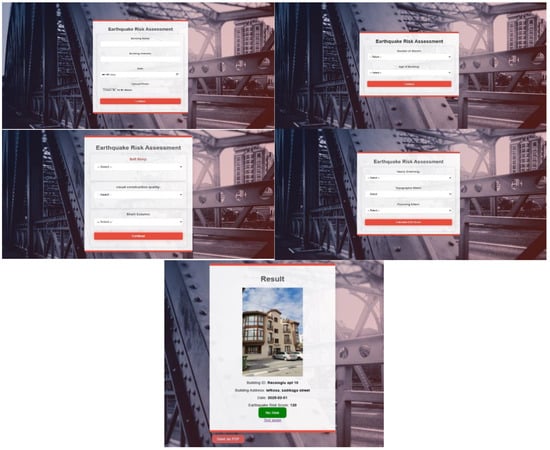

The developed web based RVS assessment tool helps the user to enter necessary data for the assessment of the RC structures’ performance against the earthquake and includes four web pages containing questions. It is each page’s intention, within the scope of the RVS method, to guarantee the collection of all pertinent information so as to provide an accurate evaluation. The first input that is expected of users is general building information on the first page of the website. This is followed by the name of the building, the address and the date on which this record was created. Moreover, users can enter a photo of the building by taking one with the built-in camera. This helps in the assessment process because the photo gives a visual aspect to the context being given. The second page contains information about structural characteristics. Users choose the number of stories from a list that includes options starting with one and ending with eight or more and the age of the building is chosen based on the options of the construction period. The third page discusses certain risk factors. Regarding the presence or absence of soft stories and short columns, users make their choices by opting for the labeled responses. Also, the users differentiate the quality of the visual construction by selecting among the poor, moderate, and good quality options. A similar strategy is followed on the fourth page, where there are more risk factors indicated. Heavy overhangs and pounding effects as well as topographic effects are other options that the users choose between presence and absence to complete the questionnaires. After providing such input, the user submits the details and moves to the fifth page, where the results of the assessment are revealed. This next page shows the results of the entered data and gives details such as the name of the building, its address, the date, photo if any, and the ERS as well as the risk status as illustrated in Figure 3. The web-based RVS assessment tool was performed on many buildings applying the web and the conventional manual method. The outcome obtained through both approaches was compared, and it was observed that both methods yielded the same results; therefore, the web-based tool is as accurate and efficient as the manual technique. This validation ensures that the web application can correctly calculate the E.R.S. and building classification in regard to risk. The developed web application is accessible for use at: https://earthquake-risk-assessment.vercel.app (accessed on 15 June 2024).

Figure 3.

Structure of the developed website.

3.2. Data Analysis

The 600-building survey provides an overall view of building characteristics, highlighting significant trends and potential hazards in the subject area.

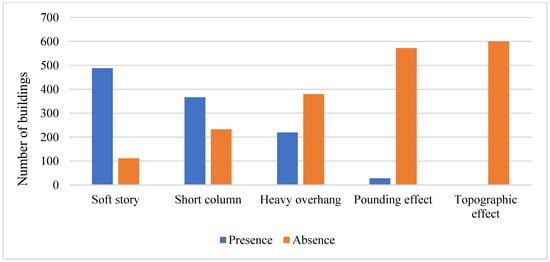

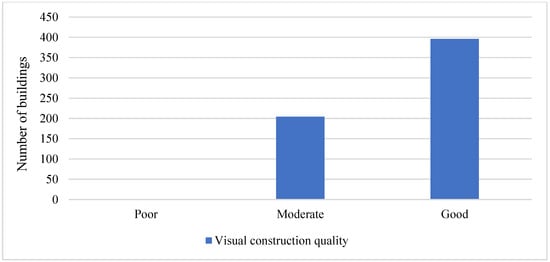

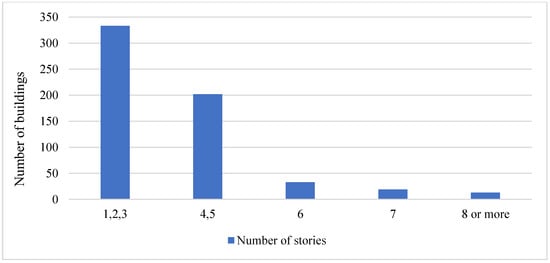

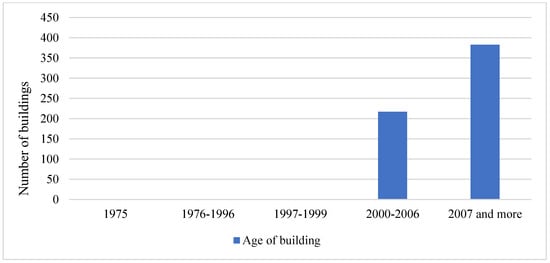

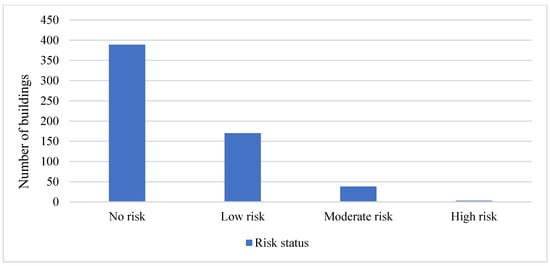

The survey of 600 buildings, conducted using the developed website, identified significant structural vulnerabilities and key characteristics. For example, 81.3% of the buildings exhibited soft-story mechanisms, and 61.2% contained short columns, both of which are critical seismic weaknesses that increase the risk of damage or collapse during earthquakes. Additionally, 36.7% of the buildings had heavy overhangs, which can create torsional effects during seismic events, and 4.7% were susceptible to pounding effects, where adjacent buildings may collide due to insufficient separation. Notably, no buildings were affected by topographic effects, as shown in Figure 4. In terms of visual construction quality, Figure 5 demonstrates that 66% of the buildings were in good condition, while 34% were in moderate condition, suggesting that while most structures are well-maintained, a significant portion may require repairs or upgrades. The distribution of building heights is as follows: 55.5% of the buildings had one, two, or three stories; 33.7% had four or five stories; 5.5% had six stories; 3.2% had seven stories; and 2.1% had eight or more stories as shown in Figure 6. Regarding construction periods, Figure 7 indicates that 63.8% were built in 2007 or later, likely complying with modern building codes, while 36.2% were constructed between 2000 and 2006 and may require closer scrutiny for seismic resilience.

Figure 4.

Prevalence of structural deficiencies in assessed buildings.

Figure 5.

Visual construction quality classification of assessed buildings.

Figure 6.

Distribution of assessed buildings by number of stories.

Figure 7.

Distribution of assessed buildings by construction age.

Having applied the RVS method on the 600 buildings that were surveyed, the results show a breakdown of seismic risk level within the buildings. As clearly visible from Figure 8, the majority of the buildings (64.8%) had no significant seismic risk. This suggests that nearly two-thirds of the buildings surveyed will respond positively to seismic activity with minimal structural defects that would lead to failure or severe damage. In addition, 28.3% of the buildings were categorized as having a low risk level. While these buildings are not entirely risk-free, they possess only minor shortcomings that could be remedied by some interventions, such as retrofitting or superficial repairs, to enhance their seismic performance. These buildings are typically considered to be of lower priority for immediate intervention but should nonetheless still be monitored or addressed in the long term to ensure safety. Fewer, 6.4%, of the buildings possessed a moderate level of seismic risk. These are less strong buildings and will require more efficient mitigation strategies such as structural reinforcement or redesigning to reduce their vulnerability to damage or collapse in an earthquake. Structures at this level should be accorded extra priority for more detailed assessment and potential retrofitting to better strengthen them. Finally, only 0.5% of the buildings were rated as high risk. This small but important subset is the one that comprises buildings highly vulnerable to seismic activity and at great risk of severe damage or collapse in the event of an earthquake. These buildings are recommended for immediate attention, such as evacuation, demolition, or very thorough retrofitting, to prevent potential loss of life and property. The results indicate that while the majority of the buildings are quite safe, a sizable proportion, particularly those in the medium and high-risk categories, require selective interventions to mitigate their seismic vulnerability. The decision makers can use this information to plan resource mobilization and design measures for enhancing the resilience of building stocks in seismically vulnerable areas. Mohd [60] conducted a seismic risk assessment of existing buildings in Famagusta, Northern Cyprus using the rapid visual screening (RVS) methodology developed by Sucuoğlu and Yazgan (2003) [61]. That study classified buildings according to their structural systems, number of stories, and year of construction. Based on this survey approach, the majority of assessed buildings were found to pose low or negligible seismic risk.

Figure 8.

Classification of assessed buildings by seismic risk status.

3.3. Correlation and Predictive Analysis Results

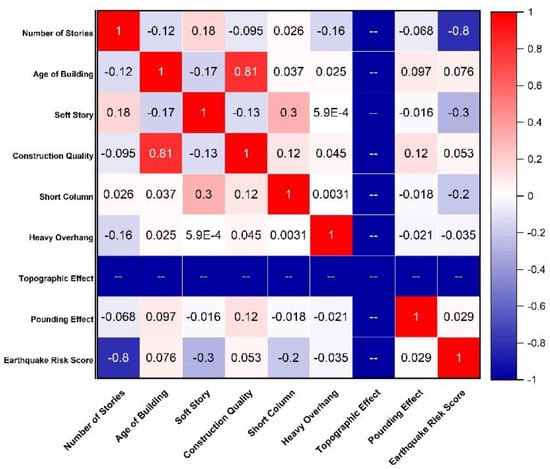

Correlation analysis was employed to identify the most significant factors that contribute to buildings’ seismic risk score. Factors considered in the assessment were number of stories, building age, presence of a soft story, construction quality, short columns, heavy overhang, topographic effect, and pounding effect. The correlation values with the risk score reflect their relative significance.

The findings of this study reveal a strong negative correlation (−0.8) between the number of stories and the seismic risk score, indicating that taller buildings are more susceptible to seismic risk. This aligns with the work of Fardis et al. [62], who emphasized that taller structures experience higher seismic forces due to increased flexibility and mass, making them more vulnerable during earthquakes. This is consistent with the findings of Chopra and Goel [63], who identified soft stories as a major contributor to irregular stiffness distribution and increased vulnerability during earthquakes. Bruneau et al. [64] further supported this by highlighting the collapse of buildings with soft stories during the 1994 Northridge earthquake. Additionally, short columns demonstrated a moderate negative correlation (−0.2) with the risk score, reinforcing their role in structural weakness. This finding is supported by Murty et al. [65], who noted that short columns attract higher shear forces, leading to brittle failure during seismic events, and Kappos et al. [66], who identified short columns as a common cause of damage in reinforced concrete buildings.

In contrast, building age and construction quality exhibited weak correlations with the risk score (0.076 and 0.053, respectively), suggesting that these factors had limited influence in the studied dataset. This finding partially contrasts with the work of Coburn and Spence [67], who argued that older buildings and poor construction quality significantly increase seismic vulnerability. The discrepancy may be attributed to the specific characteristics of the dataset, such as uniform construction practices or limited variability in building age. Heavy overhangs and pounding effects showed only slight effects on the risk score, with correlation coefficients of −0.035 and 0.029, respectively. This is consistent with the observations of Anagnostopoulos and Spiliopoulos [68], who found that while these factors can contribute to localized damage, their overall impact on seismic risk is relatively minor compared to other structural vulnerabilities. Interestingly, the analysis revealed no significant correlation for topographic effects, which contrasts with the findings of Paolucci [69], who demonstrated that site amplification due to topography can significantly influence seismic risk. This difference may be due to the specific geographic context of this study or the resolution of the topographic data used as shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Correlation heatmap of factors influencing seismic risk scores.

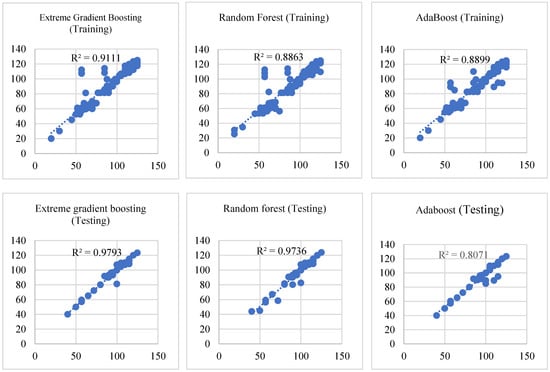

In this study, three machine learning models, Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), Random Forest, and AdaBoost, were developed and evaluated to predict risk scores for 600 buildings. The dataset was split into a training set (70%, rows 1–420) and a testing set (30%, rows 421–600). Performance was assessed using R2 (coefficient of determination) and RMSE (Root Mean Squared Error) for both training and testing. The Pearson correlation coefficient was selected for this analysis as it is the most widely used measure for quantifying linear relationships between continuous variables, provided that the data meet assumptions of normality and homoscedasticity [70].

Table 3 and Figure 10 demonstrate that, in both testing and training, XGBoost produced outstanding outcomes. It demonstrated strong predictive accuracy and the capacity to account for roughly 91.1% of the variance in the risk scores during training, with an R2 of 0.911 and an RMSE of 5.338. Its performance further improved in testing, achieving an RMSE of 2.279 and an R2 of 0.979. Although it was marginally less successful than XGBoost, Random Forest also performed well. It demonstrated good predictive accuracy and the capacity to explain 88.6% of the variance during training, with an R2 of 0.886 and an RMSE of 6.038. It continued to perform well during testing, with an RMSE of 2.577 and an R2 of 0.973. AdaBoost performed reasonably well during training, with an RMSE of 5.999 and an R2 of 0.890. Nevertheless, testing revealed a sharp decline in performance, with an R2 of 0.806 and an RMSE of 7.568. Out of the three models, XGBoost performed the best overall, obtaining the lowest RMSE and the highest R2 for both testing and training. Close behind, Random Forest had somewhat higher prediction errors and somewhat lower accuracy. Although AdaBoost performed well during training, it had trouble during testing, displaying problems with generalization and a greater variance in its predictions. XGBoost is the top-performing model in this exercise, with the best balance of accuracy and consistency, followed closely by Random Forest. AdaBoost was a contender in training but had some limitations in generalizing to new data. The findings here suggest that XGBoost is the top choice for high-stakes applications where predictive accuracy and reliability are required, with Random Forest as a viable second choice. AdaBoost may require further tuning or alternative approaches to improve its generalizability. Multiple studies have compared the performance of XGBoost, Random Forest, and AdaBoost, with varying results. Fatima et al. [71] and Choudhury et al. [72] found that XGBoost outperformed Random Forest due to its iterative optimization and higher accuracy. Şahin [73] also supported XGBoost’s superiority, showing lower prediction errors than Random Forest. However, Wu [74] reported that Random Forest performed best among the three algorithms. This discrepancy may be due to differences in dataset characteristics, feature engineering, or model tuning.

Table 3.

Performance comparison of machine learning models for seismic risk prediction.

Figure 10.

R2 score distribution for machine learning models in training and testing.

4. Conclusions

The approach used in this research included the creation and implementation of an online RVS tool, which was then followed by data analysis, correlation evaluation, and machine learning-based predictions to assess seismic risk. The conclusions are as follows:

The RVS assessment tool based on the web that has been developed has proved to be an effective and efficient seismic risk assessment tool for RC structures. In simplifying data collection and completing the assessment by having the input pages structured, the tool successfully replicates the manual RVS method with the inclusion of ease of use and precision. Validation made sure the web-based tool gives results in agreement with the conventional method, once again confirming its reliability.

The investigation of 600 buildings from three cities was enlightening regarding their seismic risk categorization and structural vulnerabilities. The findings revealed that the majority of buildings (64.8%) were non-risk, followed by 28.3% low risk, 6.4% moderate risk, and only 0.5% high risk. Structural inadequacies such as soft-story mechanisms (81.3%) and short columns (61.2%) were prevalent, and these were key areas of focus in the seismic risk assessment.

Correlation analysis revealed that the height of the structure had the largest negative correlation value (−0.8) with the risk score, and so taller buildings tend to have greater seismic hazard potential. The existence of a soft story (−0.3) and short columns (−0.2) were also key reasons for structural weakness. Heavy overhangs, pounding effects, and quality of construction all had a lower correlation, and topographic effects were of no particular value to the risk score.

Machine learning models were employed to make seismic risk scores predictions, where XGBoost was the optimal model. XGBoost revealed high prediction capacity, explaining 91.1% of the variance when being trained and 97.9% when it was tested. Random Forest, on the other hand, gave good results while AdaBoost recorded good performance upon training but had poor generalization upon testing. The predictive nature of XGBoost indicates machine learning’s strengths in enhancing the rapid assessment approaches.

This study was limited to 600 RC structures from three cities, potentially affecting its generalizability across Northern Cyprus’s diverse building stock. The particularly low representation of high-risk buildings (0.5%) may lead to the underestimation of critical cases, while the 6.4% moderate-risk buildings would benefit from integrated retrofitting recommendations (e.g., jacketing or shear wall additions). Future enhancements should expand the dataset to 1000+ buildings, incorporating additional cities, while extending the methodology to masonry and steel structures that exhibit different failure mechanisms. The correlation analysis could be deepened to examine nonlinear relationships between risk factors, and the tool could be augmented with region-specific seismic parameters and actual performance data from seismic events. These improvements would transform the platform into a comprehensive risk management system capable of delivering both accurate assessments and practical mitigation strategies for all major construction types throughout Northern Cyprus.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.A. and K.S.; methodology, O.A. and K.S.; software, O.A.; validation, O.A., K.S. and F.N.; formal analysis, O.A.; investigation, O.A., K.S. and F.N.; resources, O.A.; data curation, O.A.; writing—original draft preparation, O.A.; writing—review and editing, O.A., K.S. and F.N.; visualization, O.A., K.S. and F.N.; supervision, K.S. and F.N.; project administration, O.A., K.S. and F.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data is not publicly available due to privacy, ethical, and commercial restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| RVS | Rapid visual screening |

| RC | Reinforced concrete |

| FEMA | Federal Emergency Management Agency |

| JSIM | Japanese Seismic Index Method |

| NZSEE | New Zealand Society for Earthquake Engineering |

| IAP | Initial assessment procedure |

| DSA | Detailed seismic assessments |

| EPBs | Earthquake-prone buildings |

| GNDT | National Group of Defense from Earthquakes |

| IITK-GSDMA | The Gujarat State Disaster Management Authority Gandhinagar and the Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur |

| OASP | Earthquake Planning and Protection Organization |

| EMS | European Macroseismic Scale |

| ESC | European Seismological Commission |

| MSK | Medvedev–Sponheuer–Kárník |

| WP4 | Working Package 4 |

| EMPI | Earthquake Master Plan for Istanbul |

| METU | Middle East Technical University |

| PERA | Performance Based Rapid Seismic Assessment Method |

| TSDC | Turkish Seismic Design Code |

| AURAP | Anadolu University Rapid Assessment Method |

| ANN | Artificial neural network |

| IT2FLS | Interval type-2 fuzzy logic system |

| FLM | Fuzzy logic model |

| URM | Unreinforced masonry |

| NN | Neural network |

| ML | Machine learning |

| GBDT | Gradient boost decision tree |

| E.R.S. | Earthquake Risk Score |

| B.S. | Base Score |

| S.R.V | Score reduction value |

| V.P.M. | Vulnerability Parameter Multiplier |

| XGBoost | Extreme gradient boosting |

| R2 | Coefficient of determination |

| RMSE | Root mean squared error |

References

- Gillies, A.G.; Anderson, D.L.; Mitchell, D.; Tinawi, R.; Saatcioglu, M.; Gardner, N.J.; Ghoborah, A. The August 17, 1999, Kocaeli (Turkey) earthquake lifelines and preparedness. Can. J. Civ. Eng. 2001, 28, 881–890. [Google Scholar]

- Yılmaz, S.; Karakayali, O.; Yilmaz, S.; Çetin, M.; Eroglu, S.E.; Dikme, O.; Özhasenekler, A.; Orak, M.; Yavaşi, Ö.; Akarca, F.K.; et al. Emergency medicine association of Turkey disaster committee summary of field observations of February 6th Kahramanmaraş Earthquakes. Prehosp. Disaster Med. 2023, 38, 415–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TMMOB February 6 Earthquakes 8th Month Evaluation Report. 2023. Available online: https://www.tmmob.org.tr/icerik/tmmob-6-subat-depremleri-8-ay-degerlendirmeraporu-yayimlandi (accessed on 10 January 2025). (In Turkish)

- Kumar, M.; Gupta, A.B. Post Fire Assessment of RCC Buildings through Rapid Visual Screening. Int. Res. J. Adv. Eng. Hub (IRJAEH) 2024, 2, 1327–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.K.; Mitra, K.; Kumar, M.; Shah, M. A Proposed Rapid Visual Screening Procedure for Seismic Evaluation of RC-Frame Buildings in India. Earthq. Spectra 2010, 26, 709–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Emergency Management Agency. Rapid Visual Screening of Buildings for Potential Seismic Hazards: A Handbook; FEMA P-154; Federal Emergency Management Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2015.

- NRRC (National Research Council of Canada). Manual for Screening of Buildings for Seismic Investigation; Canadian Standard; National Research Council of Canada: Ottawa, ON, USA, 1993.

- Kudak, E. Comparison of Structural Analysis Results with Japanese Seismic Index Method. Master Thesis, Yıldız Technical University, Istanbul, Türkiye, 2005; 172p. [Google Scholar]

- New Zealand Society for Earthquake Engineering (NZSEE). An Initial Evaluation Process for Identifying Buildings Not Safe in Earthquake; New Zealand Society for Earthquake Engineering (NZSEE): Wellington, New Zealand, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kassem, M.M.; Nazri, F.M.; Farsangi, E.N. Development of seismic vulnerability index methodology for reinforced concrete buildings based on nonlinear parametric analyses. MethodsX 2019, 6, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, D.C. Seismic Evaluation and Strengthening of Existing Buildings; IIT Kanpur and Gujarat State Disaster Mitigation Authority: Gandhinagar, India, 2005; pp. 1–120. [Google Scholar]

- Earthquake Planning and Protection Organization (OASP). Provisions for PreEarthquake Vulnerability Assessment of Public Buildings (Part A); Earthquake Planning and Protection Organization (OASP): Athens, Greece, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Grünthal, G. (Ed.) The European Macroseismic Scale EMS-98; Conseil de l’ Europe Cahiers du Centre Européen de Géodynamique et de Séismologie, 15; Conseil de l’ Europe: Walferdange, Luxembourg, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Milutinovic, Z.V.; Trendafiloski, G.S. RISK-UE Project: An Advanced Approach to Earthquake Risk Scenarios with Applications to Different European Towns: WP4: Vulnerability of Current Buildings; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ansal, A.; Özaydın, K.; Edinçliler, A.; Saglamer, A.; Sucuoglu, H.; Özdemir, P. Earthquake Master Plan for Istanbul; Metropolital Municipality of Istanbul, Planning and Construction Directorate, Geotechnical and Earthquake Investigation Department: Istanbul, Turkey, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sucuoglŭ, H.; Yazgan, U.; Yakut, A. A Screening Procedure for Seismic Risk Assessment in Urban Building Stocks. Earthq. Spectra 2007, 23, 441–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakut, A. Preliminary seismic performance assessment procedure for existing RC buildings. Eng. Struct. 2004, 26, 1447–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilki, A.; Comert, M.; Demir, C.; Orakcal, K.; Ulugtekin, D.; Tapan, M.; Kumbasar, N. Performance based rapid seismic assessment method (PERA) for reinforced concrete frame buildings. Adv. Struct. Eng. 2014, 17, 439–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temur, R. Hızlı Durum Tespit (DURTES) Yöntemi ve Bilgisayar Programının Geliştirilmesi. Master’s Thesis, Istanbul Üniversitesi, İstanbul, 2006. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, O.; Guney, Y.; Topcu, A.; Çelikors, Y. A rapid seismic safety assessment method for mid-rise reinforced concrete buildings. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2018, 16, 889–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demartinos, K.; Dristos, S. First-level pre-earthquake assessment of buildings using fuzzy logic. Earthq. Spectra 2006, 22, 865–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harirchian, E.; Lahmer, T. Developing a hierarchical type-2 fuzzy logic model to improve rapid evaluation of earthquake hazard safety of existing buildings. Structures 2020, 28, 1384–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allali, S.A.; Abed, M.; Mebarki, A. Post-earthquake assessment of buildings damage using fuzzy logic. Eng. Struct. 2018, 166, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesfamariam, S.; Saatcioglu, M. Risk-Based Seismic Evaluation of Reinforced Concrete Buildings. Earthq. Spectra 2008, 24, 795–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, Z. Rapid visual earthquake hazard evaluation of existing buildings by fuzzy logic modeling. Expert. Syst. Appl. 2010, 37, 5653–5660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazumder, R.K.; Rana, S.; Salman, A.M. First Level Seismic Risk Assessment of Old Unreinforced Masonry (URM) Using Fuzzy Synthetic Evaluation. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 44, 103162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bektaş, N.; Lilik, F.; Kegyes-Brassai, O. Development of a fuzzy inference system based rapid visual screening method for seismic assessment of buildings presented on a case study of URM buildings. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadrykia, M.; Delavar, M.; Zare, M. A GIS-Based Fuzzy Decision Making Model for Seismic Vulnerability Assessment in Areas with Incomplete Data. Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2017, 6, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bektaş, N.; Kegyes-Brassai, O. Enhancing seismic assessment and risk management of buildings: A neural network-based rapid visual screening method development. Eng. Struct. 2024, 304, 117606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harirchian, E.; Lahmer, T. Improved rapid assessment of earthquake hazard safety of structures via artificial neural networks. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 897, 012014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcone, R.; Ciaramella, A.; Carrabs, F.; Strisciuglio, N.; Martinelli, E. Artificial neural network for technical feasibility prediction of seismic retrofitting in existing RC structures. Structures 2022, 41, 1220–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noura, H.; Abed, M.; Mebarki, A. Post-disaster damage assessment of structures by neural networks. Earthq. Struct. 2021, 21, 413–423. [Google Scholar]

- Özkan, E.; Demir, A.; Turan, M.E. A new ANN based rapid assessment method for RC residential buildings. Struct. Eng. Int. 2023, 33, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sri Preethaa, K.R.; Munisamy, S.D.; Rajendran, A.; Muthuramalingam, A.; Natarajan, Y.; Yusuf Ali, A.A. Novel ANOVA-statistic-reduced deep fully connected neural network for the damage grade prediction of post-earthquake buildings. Sensors 2023, 23, 6439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bektaş, N.; Kegyes-Brassai, O. Development in machine learning based rapid visual screening method for masonry buildings. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Experimental Vibration Analysis for Civil Engineering Structures, Milan, Italy, 30 August–1 September 2023; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 411–421. [Google Scholar]

- Mangalathu, S.; Sun, H.; Nweke, C.C.; Yi, Z.; Burton, H.V. Classifying earthquake damage to buildings using machine learning. Earthq. Spectra 2020, 36, 183–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaurasia, K.; Kanse, S.; Yewale, A.; Singh, V.K.; Sharma, B.; Dattu, B.R. Predicting damage to buildings caused by earthquakes using machine learning techniques. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 9th International Conference on Advanced Computing (IACC), Tiruchirapalli, India, 13–14 December 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 81–86. [Google Scholar]

- Ghimire, S.; Guéguen, P.; Giffard-Roisin, S.; Schorlemmer, D. Testing machine learning models for seismic damage prediction at a regional scale using building-damage dataset compiled after the 2015 Gorkha Nepal earthquake. Earthq. Spectra 2022, 38, 2970–2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggieri, S.; Cardellicchio, A.; Leggieri, V.; Uva, G. Machine-learning based vulnerability analysis of existing buildings. Autom. Constr. 2021, 132, 103936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadati, D.; Moghadam, A.S. EZRVS: An AI-based web application to significantly enhance seismic rapid visual screening of buildings. J. Earthq. Eng. 2024, 28, 689–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, V.; Harirchian, E.; Lahmer, T.; Rasulzade, S. Evaluation of machine learning and web-based process for damage score estimation of existing buildings. Buildings 2022, 12, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harirchian, E.; Jadhav, K.; Kumari, V.; Lahmer, T. ML-EHSAPP: A prototype for machine learning-based earthquake hazard safety assessment of structures by using a smartphone app. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. 2022, 26, 5279–5299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanda, R.P.; Damarla, R.; Nayak, K.A. Android application of rapid visual screening for buildings in Indian context. Structures 2022, 46, 1823–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ujwal, M.S.; Kumar, G.S.; Sathvik, S.; Ramaraju, H.K. Effect of soft story conditions on the seismic performance of tall concrete structures. Asian J. Civ. Eng. 2024, 25, 3141–3149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guevara, L.T.; García, L.E. The captive-and short-column effects. Earthq. Spectra 2005, 21, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Işık, E.; Akat, F. The Effect of Different Heavy Overhang on Structural Performance in Reinforced Concrete Structures. Bitlis Eren Üniversitesi Fen Bilim. Derg. 2023, 12, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raheem, S.A.; Fooly, M.Y.; Shafy, A.A.; Abbas, Y.A.; Omar, M.; Latif, M.M.S.A.; Mahmoud, S. Seismic pounding effects on adjacent buildings in series with different alignment configurations. Steel Compos. Struct. 2018, 28, 289–308. [Google Scholar]

- Gajurel, N.; Manandhar, S.; Bhatt, M.R. Influence of Topographic Effect on Dynamic Behavior of Hill Slope Building. Lowl. Technol. Int. 2020, 21, 221–228. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Moon, T.; Kim, S.J. Effect of uncertainties in material and structural detailing on the seismic vulnerability of RC frames considering construction quality defects. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 8832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Alwashali, H.; Sen, D.; Maeda, M.; Sikder, M.A.M.; Islam, M.R. Proposal of visual rating method for seismic capacity evaluation and screening of RC buildings with masonry infill. In Proceedings of the 2019 Pacific Conference on Earthquake Engineering and Annual NZSEE Conference, Auckland, New Zealand, 4–6 April 2019; pp. 4–6. [Google Scholar]

- Albayrak, U.; Canbaz, M.; Albayrak, G. A rapid seismic risk assessment method for existing building stock in urban areas. Procedia Eng. 2015, 118, 1242–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Google Earth. Satellite Imagery of Lefkoşa, Girne, and Mağusa. 2025. Available online: https://earth.google.com/ (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Han, J.; Shu, K.; Wang, Z. Predicting energy use in construction using Extreme Gradient Boosting. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2023, 9, e1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Wang, X.; Niu, D.; Luo, D.; Han, T.; Li, Y.; Huang, H.; Wu, Z. Electrical resistivity prediction model for basalt fibre reinforced concrete: Hybrid machine learning model and experimental validation. Mater. Struct. 2025, 58, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.Y.; Hwang, M.S.; Tseng, Y.W.; Yang, C.C.; Shen, V.R. Advancing Financial Forecasts: Stock Price Prediction Based on Time Series and Machine Learning Techniques. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 38, 2429188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaw, A.; Wiener, M. Classification and regression by randomForest. R News 2002, 2, 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Freund, Y.; Schapire, R.E. A decision-theoretic generalization of on-line learning and an application to boosting. J. Comput. Syst. Sci. 1997, 55, 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd, M. Seismic Risk Assessment of Existing Building in Northern Cyprus (Case Study of Famagusta). Enhancing Disaster Prev. Mitig. 2010, 10, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Sucuoglu, H.; Yazgan, U. Simple survey procedures for seismic risk assessment in urban building stocks. In Seismic Assessment and Rehabilitation of Existing Buildings; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 97–118. [Google Scholar]

- Fardis, M.N. Seismic Design, Assessment and Retrofitting of Concrete Buildings; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Chopra, A.K.; Goel, R.K. A modal pushover analysis procedure for estimating seismic demands for buildings. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2002, 31, 561–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruneau, M.; Gilbert, A.M. Ductile Design of Steel Structures; McGraw-Hill Education: Berkshire, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Murty, C.V.R. Why Short Columns Are More Damaged During Earthquakes? J. Struct. Eng. 2006, 132, 926–930. [Google Scholar]

- Kappos, A.J.; Saiidi, M.S.; Aydınoğlu, M.N.; Isaković, T. Seismic Design and Assessment of Bridges; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Coburn, A.; Spence, R. Earthquake Protection; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Anagnostopoulos, S.A.; Spiliopoulos, K.V. An Investigation of Earthquake Induced Pounding between Adjacent Buildings. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 1992, 21, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolucci, R. Amplification of Earthquake Ground Motion by Steep Topographic Irregularities. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2002, 31, 1831–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics; Sage Publications Limited: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Fatima, S.; Hussain, A.; Amir, S.B.; Ahmed, S.H.; Aslam, S.M.H. XGBoost and Random Forest Algorithms: An in Depth Analysis. Pak. J. Sci. Res. 2023, 3, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T. Predicting Titanic Survival Rates: A Comparison of AdaBoost, XGBoost, and Random Forest. Ph.D. Thesis, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhury, A.; Mondal, A.; Sarkar, S. Searches for the BSM scenarios at the LHC using decision tree-based machine learning algorithms: A comparative study and review of random forest, AdaBoost, XGBoost and LightGBM frameworks. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 2024, 233, 2425–2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, E.K. Assessing the predictive capability of ensemble tree methods for landslide susceptibility mapping using XGBoost, gradient boosting machine, and random forest. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.