Abstract

Although conventional lectures can provide a wide range of information to a large group of people, maintaining attention and ensuring knowledge transfer can be a challenge. Therefore, it is important to look for new, engaging, and effective approaches. This pilot feasibility study explores the effectiveness of virtual reality (VR) in increasing student engagement and knowledge transfer during lectures in the field of supply chain logistics and inventory selection systems. An educational VR game was developed through the systematic design of application logic, the creation of 3D assets, the construction of virtual scenes, and the implementation of gameplay. The application simulates three inventory picking methods: conventional selection, Pick by Light, and Pick by Vision systems. A total of 22 master’s students participated in the pilot study. They tested three different versions of the VR game, compared the time they needed to complete it, and participated in a guided discussion and questionnaire. The preliminary student reports indicated that students felt more engaged in the learning process and reported a perceived higher engagement with inventory picking systems compared to the traditional lecture format. On the other hand, participants mentioned concerns about nausea and the unavailability of VR headsets. The pilot results indicate that VR shows potential as an educational tool for teaching industrial logistics because it transforms the typical classroom environment into a more active and playful one, leading to a more natural understanding of the subject.

1. Introduction

Virtual reality (VR), as a flexible technology, is increasingly being used in various fields, including education. In the context of industrial engineering, where practical control of complex production and logistics processes is essential, VR offers a unique opportunity to simulate real-world situations in a safe, controlled, and flexible environment. This reveals the transition towards digitisation and the use of technology that is radically altering the present-day education and industrial process, with one of the major trends of innovation being the adoption of VR. The application of VR tech can create environments that are quite realistic and thus simulate the most intricate of processes and scenarios. This opens up new opportunities for the inhabitants of cognitive skills, critical thinking, and practical learning. VR is a constituent of Industry 4.0, which signals the connection of digitisation, automation, and smart systems not only in the industrial sector but also in academia, among the major teaching and learning methodologies [1,2].

VR is slow but surely winning over more students in different fields and at different levels, from the youngest kids in elementary schools to university students. Research has shown that VR enhances the participation of students and communication between teachers and students. Therefore, it plays a significant role in the overall teaching process [3,4]. However, it should be mentioned that the incorporation of such a technology would be fruitful only if appropriate didactic principles are applied and followed closely. Furthermore, the personal requirements of each student should be considered, especially their previous exposure to the use of digital tools [5]. Several authors point out that the best effect can be achieved when VR simulations are based on the theoretical foundations of constructivism, reflecting the principles of experiential learning and containing elements of gamification [6,7]. This creates a need to develop an evaluation framework for VR education and demonstrate improvements in teaching through quantifiable indicators (e.g., knowledge scores, engagement, retention tests) that allow VR interventions to be compared with traditional methods in controlled experiments [8]. Once the evaluation framework has been created, there is a good basis for developing immersive VR games for education with an emphasis on balancing visual quality and performance, natural interactions, and spatial sound. This ensures a higher level of user comfort in prototype scenarios, which is also key for educational immersive VR [9].

VR, combined with other modern technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), appears to be a unique digital tool that has the potential to revolutionise education and training methods, particularly through practical work training. It allows for complete immersion in a virtual world where it is possible to experiment and practice all kinds of learning without leaving the classroom, where actual teaching takes place. It does this through virtual environments that are often technically challenging, dangerous, or expensive to exist in the real world [10,11].

This work presents a pilot feasibility study on the use of VR-supported lectures in a supply and distribution logistics course. Specifically, it deals with the field of logistics from the perspective of industrial engineering. The aim of this experiment and the presented article is to enable students of the Department of Industrial Engineering at the University of Žilina to familiarise themselves with the topic currently presented in class more engagingly and interactively. To achieve this goal, an immersive educational game in virtual reality was developed, specially adapted and designed for the field of supply and distribution logistics [12].

2. Related Work

Looking at using VR in education, from an industrial point of view, contemporary VR simulations are a substantial transformation in getting personnel ready for technologically demanding operations and safety training. In the framework of Industry 4.0, these virtual laboratories are not only used for their employees’ training but are also involved in designing and optimising the entire production process, research, and product development [13,14]. Virtual simulations make it possible to model production processes, ergonomic workplace adjustments, and safety scenarios, thereby reducing the risks associated with traditional forms of practical training, such as monotony, low engagement, austerity, and a lack of audiovisual material [15,16]. Specifically, in the field of logistics, VR supports the practical training of warehouse handling systems in a safe environment, which, in the long term, improves employee orientation, does not burden ongoing production, and ultimately streamlines logistics operations [17,18]. At the same time, these findings consistently show that VR and digital sandboxes shorten design and validation cycles in industry, reduce the number of physical iterations, and enable safe testing of new settings before they are implemented in operation. Such optimisation interventions in the assembly workplace can subsequently lead to shorter transport times and rationalisation of individual flows, which can be directly transferred to VR training [19,20]. After a comprehensive analysis, it can be said that the most common application is the visualisation of material flows. These currently appear to be the most suitable for fully exploiting the potential of VR technology. This involves the creation and testing of layouts and supply strategies with immediate feedback on the throughput and load of nodes [21]. In addition to production itself, however, VR can be used to visualise the current progress of projects in real time. This can support faster decision-making, better-informed workers, and improved team coordination in the production sector [22].

Current studies suggest that VR-based learning is a form of immersive learning that leads to longer knowledge retention, increased motivation, and the development of team skills [23,24]. The results of pedagogical experiments show that students appreciate the opportunity to interactively test different work procedures, immediately evaluate the effectiveness of individual approaches, and link theory with practice in a safe digital environment [25,26]. Such results encourage stakeholders to consider the widespread use of VR in education. However, there are still persistent limitations such as financial and infrastructure requirements, potential health issues, and limited human resources [27,28]. In addition, one of the critical factors influencing technological development is the integration and combination of artificial intelligence (AI), which further opens possibilities for the personalised development of teaching materials and teaching strategies in VR environments [29,30]. The changes mentioned so far are often considered beneficial and necessary not only for today’s students, but even more so for Generation Z, for whom these changes are typical. This generation of students has the following main characteristics of their teaching style of the educational process: immediate feedback, adaptive learning methods, and the use of innovative technologies [31,32].

Thanks to such opportunities, whether in practice or among the new generation of students, it is easier to introduce VR. At the same time, sufficient progress has been made with this technology to enable it to be used in everyday education. This fact is also supported by the growing interest in the use of this technology in the aforementioned studies, the conclusions of which are relatively positive.

3. Experiment Goals and Methodology

Currently at the Department of Industrial Engineering, University of Žilina, the majority of lectures are held in conventional form-presentation in an auditorium where knowledge transfer is mainly based on listening. Although this model allows lecturers to cover essentially every topic for a large group of students, some may struggle to connect theory with practical applications, even with visual aids accompanying the lecture (such as videos showing practical applications). Moreover, lack of engagement may affect students’ willingness to attend, since lectures are often not mandatory.

As virtual reality may simulate any situation in a safe environment, it is a good candidate to be used as a method of connecting theory with practice. Especially if students can simulate an application of the taught method or technology, gaining a better understanding of how it can be translated into practical use. Industrial engineers are often required to apply their knowledge to complex manufacturing systems; therefore, simulating this complex environment in virtual reality can be very useful to showcase applications of basic principles in real processes.

The focus of the presented pilot study is to explore the feasibility of VR-enhanced lectures and to pilot-test their potential to support student engagement and perceived knowledge transfer a can be reliably used as a conventional lecture alternative. To evaluate this effectiveness, two hypotheses were proposed:

- Virtual-reality-based lectures are associated with higher perceived engagement and better perceived understanding of inventory picking systems compared to conventional lectures.

- Immersive lectures have the potential to be further investigated as an instructional method for suitable courses in university environments that support their implementation.

Lectures at the University of Žilina are not mandatory; the effort is to motivate students to attend lectures regularly without enforcing attendance with practices like bonus points. It should be the attractiveness of lectures that brings students-the aim is to encourage attendance through motivation, not through reward. The main goal of this experiment is to pilot future studies and identify the potential of interactive lectures powered by virtual reality. Although it is important to consider a possible restriction on such an approach. Therefore, three conditions were considered to ensure the viability of virtual reality education games at the chosen lecture:

- Lecture with a relatively low attendance (limited number of VR headsets).

- Lecture topic with a great potential for VR simulation.

- Lecture with sufficient time reserve for the selected topic.

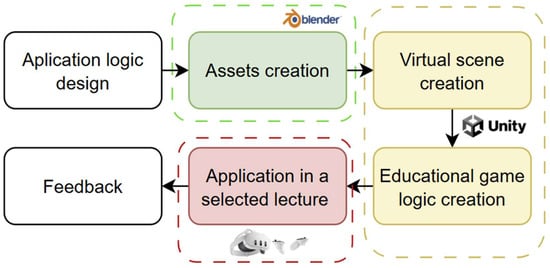

After consideration of possible applications, the lecture covering the subject of supply and distribution logistics was chosen. Specifically, the topic of inventory picking showcases inventory picking systems such as Pick by Light, Pick by Vision, or Pick by Voice. During a lecture on this topic, videos and pictures are shown of various inventory picking systems, which may often not be enough to sufficiently explain the basics of their application. However, with VR, we can simulate a process of inventory picking from the “worker’s point of view”. This way, students can try to apply a direct application of an inventory picking system that closely follows real processes. With the topic selected, the development of a VR educational game started, which consisted of multiple steps to ensure a precise simulation of the subject (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Simple diagram of the development workflow for the educational VR application.

This diagram represents a simplified version of the entire process, from initial analyses to testing and the collection of feedback. Each step will be described in more detail in the following chapter.

The pilot study design is mainly based on observing students’ reactions and engagement in a new approach to lectures supported by post-lecture discussions and a short questionnaire. In total, 22 students attended, composed of twenty men and two women, all being industrial engineering students in their second year of master’s degree studies. The focus was on reducing the invasiveness of the experiment, which had to accurately simulate the selected lecture without influencing the students. Apart from the discussion and questionnaire that took place after the lecture, the entire method of information collection was based on observation.

Currently, every lecture at the Department of Industrial Engineering, University of Žilina, is based on a traditional approach—presentation in an auditorium. As mentioned above, lectures are not mandatory for students, which results in fluctuating attendance. According to data collected in one semester of 2025, only one subject out of five observed kept average attendance at over 50%. For the selected subject-supply and distribution logistics, only 46% of students attended the lectures regularly. The more engaging nature of virtual reality could be a helpful tool to raise this number. While the pilot study focuses on the effectiveness of this new approach compared to the conventional method, an indirect result of this implementation could be an increase in attendance. This subject is also only attended by students of Industrial Engineering; therefore, its small scale is a good cornerstone for a pilot study. With good results, this approach could be applied to large-scale lectures attended by the entire Faculty of Mechanical Engineering.

4. Immersive Lecture Design

4.1. Application Logic Design

As a first step, it was important to set the expectations and capabilities of the application. Since the game focuses on inventory picking systems, the following conditions had to be established to ensure a potential knowledge transfer of the picked subject:

- Creating a clear progression (logic) for playing educational games for students.

- Creation of virtual environments suitable for inventory picking simulation.

- Creation of game scenarios to simulate inventory picking.

- A way for students to choose between these scenarios.

- A way for students to compare simulated methods (gamification elements).

- A baseline which can be used as a starting point—simulation of conventional inventory picking.

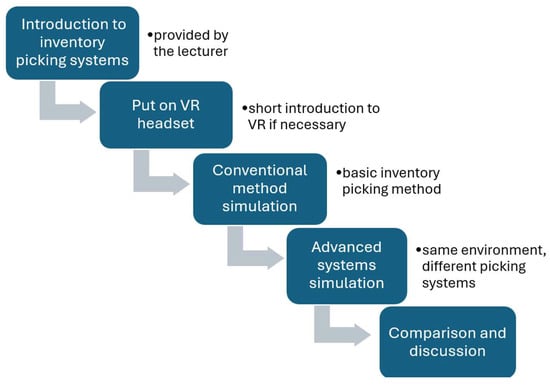

All conditions mentioned above were addressed in various parts of the development process. Firstly, a clear plan of how the application will function was created. Figure 2 shows a plan on how students can approach the experience to maximise the possible knowledge transfer, while also serving as a blueprint for a VR-enhanced lecture.

Figure 2.

Experimental procedure showing the sequential stages of the VR educational session.

This plan sets a cornerstone for each step of development and its requirements for each phase of development. Alongside the application logic, one more very important element is the logic (scenario) of educational games themselves—the breakdown of steps simulated in those games. It breaks down what the player (student) needs to do to complete the educational game, while it also serves as an important reference. In this case, three scenarios were created covering three alternatives of inventory picking:

- Conventional inventory picking scenario.

- Pick by Light system scenario.

- Pick by Vision system scenario.

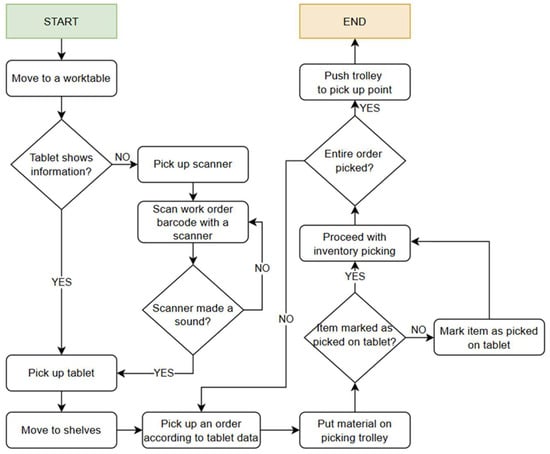

Having three scenarios means that applications were divided into three different educational games, while also being an important starting point for the next phase—assets creation. These scenarios created a list of asset requirements needed to develop a virtual reality simulation that follows them, such as 3D models or sound effects. Figure 3 shows an example of one of the proposed scenarios.

Figure 3.

The scenario of the conventional inventory picking method.

The scenario in the picture represents the conventional inventory picking method. It also serves as a foundation to create other scenarios, where the workflow will be similar but enhanced with technologies of different inventory picking systems.

4.2. Assets Creation

Asset creation represents a group of processes whose goal is to gather every possible element required to build a realistic virtual environment, such as the following:

- Reference requirements analysis.

- Gathering of references.

- Acquiring necessary assets (3D modelling, buying, browsing own asset libraries)

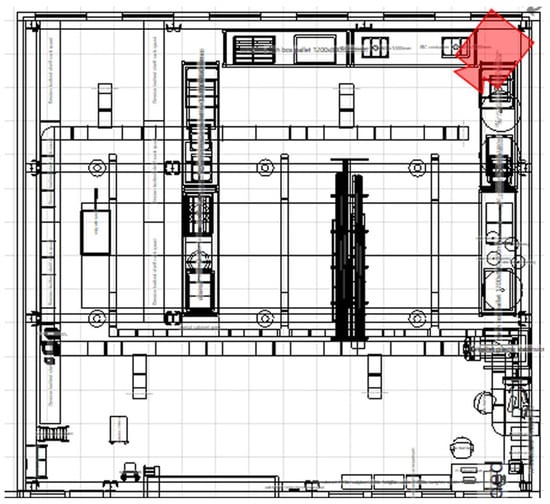

Firstly, a 2D layout of a warehouse was created along with a list of 3D models required for the creation of a realistic 3D model of this layout. However, it is important to ensure that the created warehouse model is suitable for the specified inventory picking simulation. That being the case, it is vital to consider the created game scenarios (Figure 3). For example, the presented scenario uses a barcode scanner; therefore, a 3D model of this scanner, along with appropriate sound, must be secured. For a 2D layout creation, a manufacturing system design software VisTable 3.0 was used. It allows a smooth transition from 2D to 3D, assuming all 3D models are available in libraries. Figure 4 shows the 2D layout design of the warehouse.

Figure 4.

Two-dimensional layout design of the warehouse.

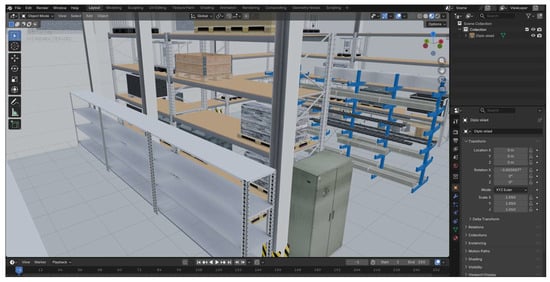

In addition, different assets had to be obtained that were not available in libraries. This includes various 3D models and sounds required to precisely replicate designed scenarios, such as tablet or special buttons and lights for the Pick by light system. Finally, after gathering the required assets, it is important to check their suitability for VR game development. Three-dimensional models needed to be in a correct format with a suitable mesh complexity to ensure smooth performance. Figure 5 shows a 3D model of a warehouse imported into Blender 4.1 3D modelling software to fix any possible issues.

Figure 5.

Three−dimensional model design of the warehouse in Blender.

After identifying and fixing any issues, every asset is ready to be imported into a game engine for the next phase of development.

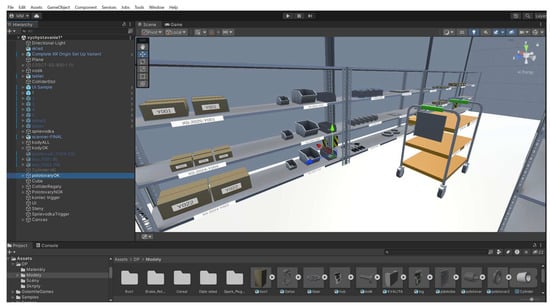

4.3. Virtual Scene Creation

The application itself was developed in Unity 3D game engine. Before the scene creation, a basic setup had to be made to prepare Unity for VR development. After that, all assets were imported, performing one last compatibility check. Virtual scene creation represents the building of every virtual environment that will be used in the application. In total, four virtual environments had to be created:

- HUB for inventory picking simulation selection.

- Virtual warehouse for conventional inventory picking.

- Virtual warehouse for Pick by Light inventory picking system.

- Virtual warehouse for Pick by Vision inventory picking system.

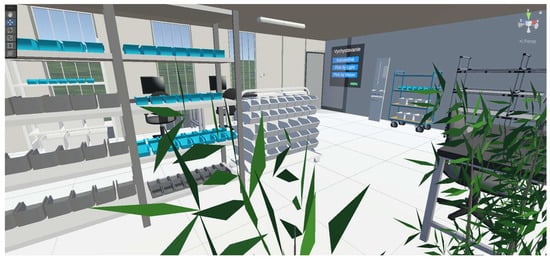

At the start, players will spawn in HUB, where they can pick from three different inventory picking games. Each game is based on the same virtual warehouse that is slightly modified for each inventory picking system. Figure 6 shows a scene that will serve as a HUB, a simple environment that contains a virtual menu for scene selection.

Figure 6.

HUB scene, where the player will spawn to choose the inventory picking game to play.

The entire 3D model of the warehouse was imported into Unity 3D and served as a base for each inventory picking scene, while additional assets were added to ensure a correct simulation. Figure 7 shows a virtual warehouse imported into the scene, ready to be modified.

Figure 7.

Imported a 3D model of the warehouse used for all inventory picking games.

4.4. Educational Game Logic Creation

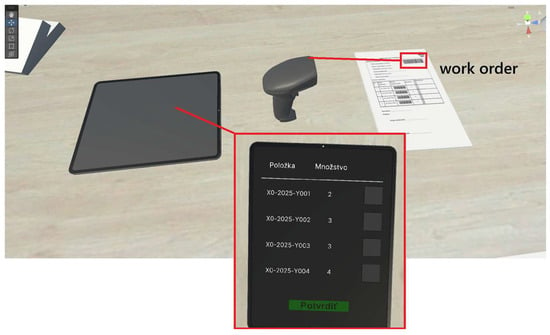

The player’s goal in this educational game is to pick the material contained in the work order and prepare it for processing using the picking cart. This simulation reflects the real process in logistics operations. In this phase, scenarios created in the previous phase (example shown in Figure 3) need to be turned into an interactive, immersive virtual experience that precisely replicates all steps. The logic of each game must follow each step of the scenario in exact order. The best way to achieve this is to split each task into elemental steps, such as moving to a position or grabbing an object. The player should not be overwhelmed with complex tasks, but instead be slowly led through the process to achieve effective knowledge transfer.

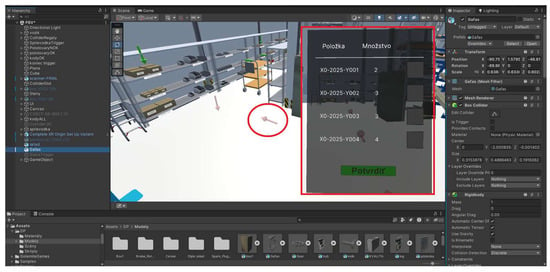

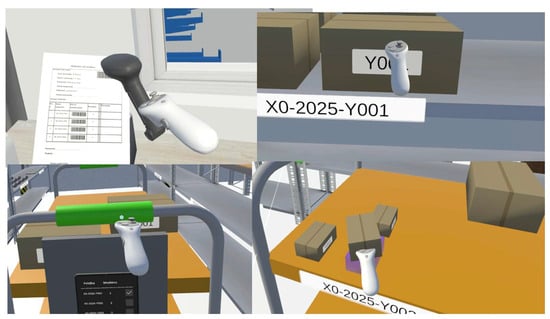

As the first game, players should experience the conventional inventory picking to set a standard and baseline to compare with more advanced systems. At the start of the game, the player scans a work order, which is then displayed on a tablet, as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Scanning the barcode that will show the order on a tablet.

In the next phase, the player moves to the shelves, where it is necessary to prepare the environment and all the interactive objects. Since the player searches for individual materials by code on the tablet, codes were placed on the shelves to identify them. The corresponding material was then placed next to the individual codes. The shelves contain not only the items intended for picking, but also others, which simulate a real warehouse environment and force the student to actively search for the correct items (Figure 9). After identifying the correct item, the player grabs the material and transfers it to the picking cart. Specific places have been prepared on the cart to store individual items. A “socket interactor” was used for this functionality, which allows for a fixed placement of the object in a selected location. When the user places an object in the interaction zone, it is automatically placed on the cart, ensuring that the items do not fall out when moving from the cart. After completing the item picking, the player confirms the fulfilment of the task on the tablet and then moves the prepared cart to the pickup location. This action ends the level and informs the player that the task has been completed.

Figure 9.

Preparing shelves with items and corresponding codes used for picking.

Finally, it was necessary to provide the player with a guide to all the steps of the procedure. The user interface was prepared to lead the player through the entire game. The steps had to be explained in reasonable doses so that the user was not overwhelmed with information. The entirety of UI consisted of floating text fields, which provided necessary instructions, letting players progress only if all steps were completed.

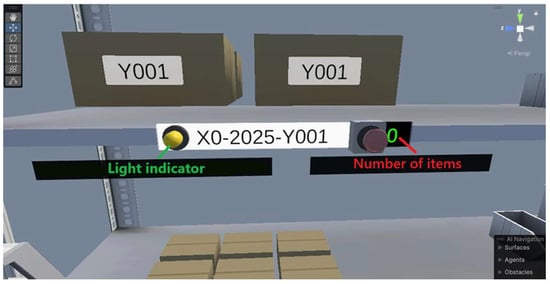

The second educational game, focused on Pick by Light technology, was based on the first scene, since a big portion of the workflow remained the same. The shelves have been equipped with a set of lights. These lights lit up green to highlight ordered items, which is a characteristic feature of the Pick by Light system. The lights have been supplemented with a button and a display that shows the number of pieces listed in the work order. After picking up the required number of items, the player presses the button, which confirms that the task has been completed, and the display is reset. Instead of manually searching for a correct code, the player is now guided by lights, making the process easier. An example is shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Example of Pick by Light system, showing if the item is on the picking list and the required amount.

The system works on a simple principle: scanning the work order activates the lights and buttons on the shelves for the items listed in the order. At the same time, the display changes to the desired number of pieces, and the light turns green.

The third educational game, focused on Pick by Vision technology, was created similarly, i.e., by copying the previous scene and adding specific elements of this picking system. The main enhancement element is a mixed reality headset that displays additional information (Figure 11). When put on, the headset displays navigation arrows according to the scanned work order. In addition, on the user’s left hand, information about material picking is displayed. After players arrive near the shelves, the red navigation arrows disappear, while only green arrows remain active and signal the position of the items for picking. After placing the material on the cart, the picking is confirmed on the virtual tablet, and the arrow that signalled the position for this material disappears. These elements simulate using augmented/mixed reality in the real world through VR simulation. The Pick by Vision educational game represents advanced level of interactivity and provides a realistic representation of modern logistics technologies. The interactive elements of the headset allow students to learn the workflow experientially without having to be physically present in a real distribution centre. Visual feedback through colour changes and the gradual disappearance of arrows provides immediate confirmation of correct task completion and manages cognitive load to an optimal level. In this way, students learn not only the theoretical knowledge of the Pick by Vision system, but also the practical application and effectiveness of this technology in a real work environment.

Figure 11.

Example of Pick by Vision technology created for the VR game.

The user interface was adapted to the Pick by Vision system to reflect its features and allow students to understand the principles of this logistics tool. With all three educational game variants completed, a testing phase followed to verify all aspects of the gameplay. Testing included the following:

- Verify the functionality of all game mechanisms, scripts and interactive elements in the Unity 3D environment.

- Test the correct transitions between individual scenes, the use of the script for switching scenes and UI buttons in the HUB.

- Last check the correct display of 3D models, textures and sound effects in different scenes.

- Identify and fix any errors in the game logic, object collisions or in the user interface.

- Test all three inventory picking game variants (conventional picking, Pick by Light, Pick by Vision) and ensure that each step of the scenario is understandable and functional for the player.

With testing concluded, the whole application was ready to be tested in the proposed utilisation—an experimental interactive educational tool for lectures. A preview of testing is shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

Complex testing of the VR game.

4.5. Application in the Lecture and Feedback

The result of development was an educational game that consisted of three variants of the inventory picking game. As a pilot experiment, it was used during a lecture on supply and distribution logistics. Supply and distribution logistics is a subject taught in the second year of master’s degree study at the Department of Industrial Engineering, University of Žilina.

To enhance the possibility of students evaluating and comparing presented inventory picking systems, gamification elements were added in the form of in-game time tracking. Students could keep a track of how long each session took them. This element allows students to quantitatively compare the times required to complete a task using different technologies, providing a basis for discussion of the advantages and disadvantages of each approach. Additionally, it adds a sense of competitiveness among students to complete the task the fastest.

5. Results

The experimental lecture took place during a specific supply and distribution logistics lecture that focused on inventory management and inventory picking, which usually lasts two to three hours (including breaks). The first part consists of a conventional approach—presentation in an auditorium. For the second part, students moved to a laboratory focused on VR educational games development. This is where the VR demonstration took place, according to Figure 2. Supply and demand logistics as a subject is only part of one study programme, which decreases the potential number of students attending the lecture, and this lowers the capacity demands, while also decreasing the sample size. In total, 22 students attended the lecture and took part in the experiment. The laboratory management gradually familiarised students with the principles of virtual reality and safe procedures for using VR headsets before starting the simulations. Each student completed all three variants of the educational game in the same order: conventional picking, Pick by Light, and Pick by Vision to ensure consistency of the lecture and uniform conditions for comparing the effectiveness of each method.

Students were divided into groups because of the laboratory capacity limitations. However, if more experiments are conducted in the future, the plan is to implement VR directly in the auditorium. The course of the experiment can be divided into five points:

- Allow students to try all three variants of inventory picking games in a VR environment.

- Compare task completion times in individual games using the implemented timer (gamification element).

- Discuss with students the advantages and disadvantages of individual picking methods, as well as the possibilities for improving the process and user interface.

- Obtain feedback on the intuitiveness of the controls, the clarity of the instructions and the overall experience of the application.

- Summarise suggestions for improvement that can be used in further developing the application of VR in lectures.

Students spawned in HUB, where they had an opportunity to familiarise themselves with controls and UI interaction. Then they played through all three games, starting with a conventional inventory picking game. Students would take turns playing while others spectated on the TV screen. The work order was randomised to prevent any prior knowledge of the required items’ position. For a conventional inventory picking, students often struggled to find positions of required items, but for two other games (with an inventory picking system integrated), the process was much smoother.

During the experiment, completion times were collected at the end for additional comparison and discussion. The fastest time for conventional picking was 3:05 (minutes), for PBL, 1:24, and for PBV, 1:25. The average completion times were 4:33 (SD = 0:34) for conventional picking, 2:29 (SD = 0:41) for PBL, and 2:27 (SD = 0:28) for PBV, indicating a substantial reduction in task duration when using technology-supported methods. Such a comparison of times can serve as a tool for emphasising the need for process innovation for students. These data demonstrate that the integration of automated picking systems has led to a substantial reduction (46%) in average completion times in (using PBV), compared to the conventional approach. This is based on the time saved compared to the conventional method. PBV also showed the lowest variability in performance across students, suggesting more consistent task execution. The observed improvement in efficiency was particularly noticeable with the Pick by Vision method, which combines a navigation guide with visual feedback and allows students to learn optimal work practices in real time. The table with times is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Completion times for inventory picking methods in a VR game by a student (in minutes).

Only descriptive statistics were calculated due to the small sample size and pilot character of the pilot study; therefore, differences between methods should be interpreted as indicative trends rather than conclusive evidence.

Suppose students can see how much time they saved by using different and improved methods. In that case, they can experience the simulation of practical application while also understanding how much it can improve the process. Unlike the regular lectures, they can grasp the principle of the taught method while also understanding how it affects the employee.

After all students had their turn, the discussion followed, where students would compare methods and list their advantages and disadvantages with a time sheet available to them. With a theoretical basis combined with virtual experience, students possibly obtained enough knowledge and practical understanding of the presented subject to form an opinion. During a discussion, every student stated their preferred inventory picking system. A total of 12 students preferred Pick by Vision, while 10 students preferred Pick by Light. Compared to the conventional method, the main advantages students considered were:

- Much better orientation in a warehouse while looking for ordered items.

- Lowered the likelihood of making a mistake.

- Smoother transition between finding a correct item and picking it—both hands were free, no need to walk with a tablet.

As for the main disadvantages, students listed problems such as the following:

- Investment costs.

- Employees having issues with wearing a mixed reality headset (for Pick by Vision)

- Accidental button press (for Pick by Light)

A key observation from this experiment was that students appeared more engaged and communicative during the entire second part of the lecture, compared to the conventional first part. They seemed to truly grasp the principles of inventory picking systems.

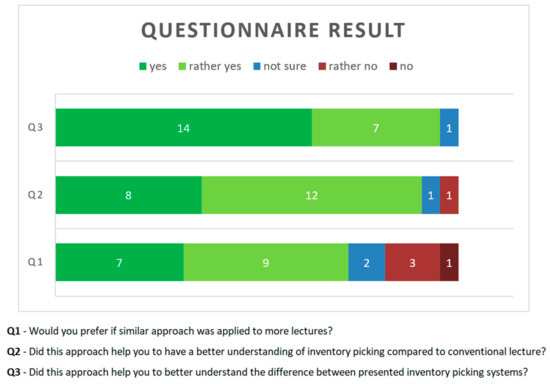

After the experiment, students filled out a short questionnaire evaluating their experience of the modified lecture. The questionnaire was in paper form, composed of open and closed questions with the possibility to add your own comment. All questions were directly connected to the discussion to expand on students’ answers. Students were asked several questions rating their satisfaction with the proposed approach:

- Would you prefer if a similar approach were applied to more lectures? (Q1)

- Did this approach help you to have a better understanding of inventory picking compared to conventional lectures? (Q2)

- Did this approach help you to better understand the difference between the presented inventory picking systems? (Q3)

- What part of this approach did you like the most?

- What part of this approach did you find problematic?

- How would you improve this approach moving forward?

The questions in the questionnaire were proposed by the authors and were based on expectations of what this approach could bring to improve the educational process. For the first three questions, students could choose between five answers: yes, rather yes, not sure, rather no, or no. The last three questions were open questions. The next day, after summarising the answers from the questionnaires, a brief discussion was held again with the same students. Figure 13 shows the results for the first three questions.

Figure 13.

Results for the first three questions.

In the last three questions, students had the opportunity to elaborate on their answers to the first part of the questionnaire, which could be further discussed in the following discussion. In the fourth question, students could state what they like about this approach; the most common answers were as follows:

- Novelty and interactivity of the approach compared to a regular lecture.

- Connection to practical applications of the presented subject.

- More relaxed and laid-back atmosphere of the experimental lecture.

In the fifth question, students could state what they thought was the biggest shortcoming of the proposed approach; the most common answers were as follows:

- Discomfort while wearing a virtual headset for an extended period.

- Small number of available headsets—longer wait time for their turn.

For a last question, students could leave their suggestions on improving the experience for a future application of this approach. Improvement suggestions included the following:

- Increasing randomness, such as anomalies caused by human error.

- Expanding introduction to VR for students who are less familiar with it.

The questionnaire and subsequent discussion suggest a clear interest in these types of lectures, which support the current interest and attractiveness of virtual reality. The experiment suggests a clear interest in an interactive approach to education, provided the application is under the right conditions. It also highlights the obvious problems with such an application, mainly due to limited capacity and simulator sickness.

6. Discussion

This pilot feasibility study examined VR-powered lectures’ performance metrics and student feedback, revealing some trends alongside methodological limitations. Mean task completion times reduced from 4:33 (SD = 0:34) for conventional inventory picking, to 2:29 min (SD = 0:41) for Pick by Light, and 2:27 (SD = 0:28) for Pick by Vision. This is a 46% cut in time throughout medians (4:41, 2:24, 2:29). Questionnaire responses indicated acceptance levels of 86–95% among students that their understanding of inventory picking systems and their differences was improved. Some of the limitations that were pointed out included a lack of comfort with the VR headset and limited availability, which contributed to longer waiting times.

The increase in student engagement and preference for interactive VR matches the literature on VR in industrial engineering education and higher education. Radianti et al. (2020) [3] and Hamilton et al. (2021) [4] report similar increases in motivation and experiential learning through immersive simulations. Compared to these studies with objective knowledge tests (pre/post quizzes, retention assessments), this pilot study relied only on performance times and self-reports, which limited direct comparability.

The shorter completion times for PBL and PBV were probably due to navigational aids (lights, arrows) that lowered cognitive load during item location. This allows both hands for picking with no tablet reference and decreases search errors in the simulated warehouse mess. The lower variability of PBV (SD = 0:28) is indicative of the progressive visual feedback that allowed uniform execution among participants. Gamification via in-game timers created a competitive atmosphere, which, in turn, brought the visible motivation of students during group rotations and discussions. This, in turn, made the practical relevance felt more than in the case of passive lectures.

The small and homogeneous sample consisting of only 22 second-year industrial engineering students, mostly male, indicates limited application to other groups. The unavailability of a pure conventional lecture control group with the same time allocation excludes the possibility of distinguishing VR-specific effects. Knowledge tests before and after the treatment were not given; only subjective questionnaires and observational engagement were used. The fixed testing order (conventional → PBL → PBV) carries the risk of introducing learning effects, while technical limitations (2 headsets, lab capacity) resulted in waiting periods and some participants reporting VR sickness.

Key limitations of this pilot study include small sample size (n = 22), no objective learning measures (e.g., pre/post knowledge tests), fixed order of conditions (no counterbalancing) and restriction due to time and capacity limitations of lectures. Future work should address these through controlled experiments with validated instruments.

Logistics education using VR technology is not only feasible, but it could also motivate students to attend lectures more often since it focuses on active immersion. Therefore, future studies could prove the effectiveness of VR in learning via more objective tests (pre/post tests), randomised method orders, larger and more varied samples with control groups, and long-term retention evaluations. All of which are necessary to confirm learning outcomes and the scalability of the VR setting to lectures.

7. Conclusions

Overall, students reported positive experiences, warranting further validation. The majority would welcome this approach as an expansion of regular lectures, if the presented subject was suitable. They also felt that it helped them to have a better understanding of the presented subject. A few students expressed their doubts, which they could expand on in the open-question part of the questionnaire and following the discussion. The main problem was the discomfort associated with using a VR headset—simulator sickness. Even though they could finish the entire experiment, in the case of longer educational VR games, it could be problematic. As an alternative, they proposed the mock-up storage room that could serve the same purpose as the presented inventory picking games. However, they acknowledged the higher cost and resource requirements. In the end, the consensus was to focus on reducing simulator sickness triggers (such as sudden and uncontrolled movements) in VR games, if used in more lectures. As part of the discussion, the question of lecture attendance was brought up; the consensus among students was that they would consider attending lectures more frequently if they were enriched with modern technology. The question of capacity for this kind of lecture was also discussed. This time, two virtual headsets were used, which greatly reduced the number of students who could try the experience in a reasonable time. However, increasing the number of headsets should not be the problem, since their good mobility allows them to be used outside the VR laboratory. Based on the results, more experimental interactive lectures should be conducted in the future. It is worth noting that the small sample size of 22 students does not provide sufficient data, but it provided a good starting point for future studies in the field of VR-based lectures. Future studies plan to expand on the presented experiment, focusing on bigger lectures with higher attendance, covering different subjects, simulating different methods and technologies. The main goal is to verify if such a lecture type is viable for a large audience from a knowledge transfer, but also from a management standpoint.

Two hypotheses were proposed at the start, the first hypothesis questions if Virtual-reality-based lectures are associated with higher perceived engagement and better perceived understanding of inventory picking systems compared to conventional lectures. Positive feedback leans in favour of the proposed hypothesis. In the questionnaire, an overwhelming majority of students felt that this type of lecture helped them to understand the topic better compared to conventional lectures. The majority would also welcome a similar approach for other subjects. Although student self-reports and observed engagement tended to support the first hypothesis, the absence of pre/post knowledge tests and control conditions prevents drawing firm conclusions about knowledge transfer. In addition, the small sample size may not correctly reflect reality; therefore, further studies will be needed to definitively confirm the hypothesis. The second hypothesis questions whether immersive lectures have the potential to be further investigated as an instructional method for suitable courses in a suitable university environment. Although the pilot study took place without major shortcomings while being a positive experience for students, the approach was applied to a lecture with low participation, which cannot reliably assess its applicability on a wider scale. Therefore, more studies are required to explore this possibility.

Based on this pilot test and student feedback, the created VR application appears feasible as a tool for interactive lectures, but its effectiveness still requires validation in larger, controlled studies with objective learning measures. The majority of students found the environment clear, intuitive, and the individual steps are clearly explained in the user interface. Students particularly appreciated the possibility of interactive testing of different picking methods (conventional, Pick by Light, Pick by Vision) and the immediate comparison of the effectiveness of individual approaches. The application supports active learning, development of practical skills and teamwork. For teachers, it offers the possibility to expand the teaching process engagingly to enhance the experience and knowledge transfer. Given the pilot nature of this study, small sample size (n = 22), and reliance on task completion times and self-reported measures without objective knowledge assessments, these findings represent preliminary observations that warrant further investigation in larger, controlled studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, M.M. and T.B.; methodology, M.M. and T.B.; software, M.M.; validation, Ľ.D. and M.M.; formal analysis, M.G.; investigation, M.G.; resources, M.M.; data processing, Ľ.D.; writing—preparation of the original draft, M.M.; writing—review and editing, T.B.; visualisation, M.M.; supervision, M.G.; project administration, Ľ.D.; funding acquisition, Ľ.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the KEGA Agency of Ministry of Education, Research, Development and Youth of the Slovak Republic under the contract no.: 001ŽU-4/2024 and under the contract no.: 013ŽU-4/2025.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to non interventional nature of the study. The study was a non-interventional experiment involving observing reaction to a new type of interactive lecture in healthy adult volunteers and did not involve any clinical procedures or collection of identifiable personal data. Under Slovak legislation (Act No. 362/2011 Coll. on Medicinal Products and Medical Devices; Act No. 576/2004 Coll. on Healthcare), such research is not subject to mandatory prior approval by a medical ethics committee.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| VR | Virtual reality |

| PBL | Pick by Light |

| PBV | Pick by Vision |

| UI | User interface |

References

- Akpan, I.; Offodile, O. The Role of Virtual Reality Simulation in Manufacturing in Industry 4.0. Systems 2024, 12, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machała, S.; Chamier-Gliszczyński, N.; Królikowski, T. Application of AR/VR Technology in Industry 4.0. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 207, 2990–2998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radianti, J.; Majchrzak, T.A.; Fromm, J.; Wohlgenannt, I. A systematic review of immersive virtual reality applications for higher education: Design elements, lessons learned, and research agenda. Comput. Educ. 2020, 147, 103778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, D.; McKechnie, J.; Edgerton, E.; Wilson, C. Immersive virtual reality as a pedagogical tool in education: A systematic literature review of quantitative learning outcomes and experimental design. J. Comput. Educ. 2021, 8, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.F.A.; Mazha, T.; Shahzad, T.; Khan, M.A.; Ghadie, Y.Y.; Hamam, H. Integrating educational theories with virtual reality: Enhancing engineering education and VR laboratories. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2024, 10, 101207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallek, F.; Mazhar, T.; Shah, S.F.A.; Ghadi, Y.Y.; Hamam, H. A review on cultivating effective learning: Synthesizing educational theories and virtual reality for enhanced educational experiences. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2024, 10, e2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampropoulos, G.; Kinshuk. Virtual reality and gamification in education: A systematic review. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2024, 72, 1691–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolanti, M.; Puggioni, M.; Frontoni, E.; Giannandrea, L.; Pierdicca, R. Evaluating Learning Outcomes of Virtual Reality Applications in Education: A Proposal for Digital Cultural Heritage. ACM J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2023, 16, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J. Research on Design Methods for Immersive Games Based on Virtual Reality. Dean Fr. Press 2024, 2, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paszkiewicz, A.; Salach, M.; Dymora, P.; Bolanowski, M.; Budzik, G.; Kubiak, P. Methodology of Implementing Virtual Reality in Education for Industry 4.0. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carretero, M.d.P.; García, S.; Moreno, A.; Alcain, N.; Elorza, I. Methodology to create virtual reality assisted training for automotive industry. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2021, 80, 29699–29717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ansi, M.; Jaboob, M.; Garad, A.; Al-Ansi, A. Analyzing augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) recent development in education. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2023, 8, 100532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dammacco, L.; Carli, R.; Lazazzera, V.; Fiorentino, M.; Dotoli, M. Designing complex manufacturing systems by virtual reality: A novel approach and its application to the virtual commissioning of a production line. Comput. Ind. 2022, 143, 103761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid, M.; Haleem, A.; Singh, R.P.; Dhall, S. Role of Virtual Reality in advancing education with sustainability and identification of Additive Manufacturing as its cost-effective enabler. Sustain. Futures 2024, 8, 100324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K. VR/AR in ergonomics and workspace design: A dual-perspective analysis of applications and implications. Appl. Ergon. 2025, 129, 104612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kačerová, I.; Kubr, J.; Hořejší, P.; Kleinová, J. Ergonomic Design of a Workplace Using Virtual Reality and a Motion Capture Suit. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubr, J.; Lochmannová, A.; Hořejší, P. Immersive Virtual Reality Training in Industrial Settings: Effects on Memory Retention and Learning Outcomes. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 168270–168282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novikov, K.; Hořejší, P.; Kubr, J.; Dvořák, M.; Bednář, M.; Krákora, D.; Krňoul, M.; Šimon, M. Methodology for Rationalization of Pre-Production Processes Using Virtual Reality Based Manufacturing Instructions. Machines 2024, 12, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plinta, D.; Dulina, Ľ.; Furmannová, B.; Zuzik, J. Transport Efficiency Strategies in Assembly Workplace: A Case Study. Commun. Sci. Lett. Univ. Zilina 2024, 26, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajcovic, M.; Dulina, L.; Binasova, V.; Zuzik, J. The design of elements of an adaptive assembly system. MM Sci. J. 2023, 12, 7035–7041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulina, L.; Zuzik, J.; Furmannova, B.; Kukla, S. Improving Material Flows in an Industrial Enterprise: A Comprehensive Case Study Analysis. Machines 2024, 12, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuzik, J.; Furmannová, B.; Dulina, L. Streamlining Project Management in the Production Sector: A Case Study of Industrial Engineering. Manag. Prod. Eng. Rev. 2024, 15, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, M.; Kablitz, D.; Schumann, S. Learning effectiveness of immersive virtual reality in education and training: A systematic review of findings. Comput. Educ. X Real. 2024, 4, 100053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aufenanger, S.; Bastian, J.; Bastos, G.; Castelhano, M.; Dias-Ferreira, C.; Fokides, E.; Gavalas, D.; Kasapakis, V.; Agelada, A.; Kostas, A.; et al. Immersive virtual reality learning environments for higher education: A student acceptance study. Comput. Educ. X Real. 2025, 7, 100105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pribadi, A.P.; Rahman, Y.M.R.; Silalahi, C.D.A.B. Analysis of the effectiveness and user experience of employing virtual reality to enhance the efficacy of occupational safety and health learning for electrical workers and graduate students. Heliyon 2024, 10, e34918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krákora, D.; Hořejší, P.; Šimerová, A. Comparative Analysis of Employee Training Using Conventional Methods and Virtual Reality. Teh. Glas. 2025, 19, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.C.; Limniou, M.; Wu, W.C.V. Virtual learning environments in educational institutions. Front. Virtual Real. 2023, 4, 1138660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strojny, P.; Dużmańska-Misiarczyk, N. Measuring the effectiveness of virtual training: A systematic review and universal framework. Comput. Educ. X Real. 2023, 2, 100006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemminki-Reijonen, U.; Hassan, N.M.A.M.; Huotilainen, M.; Koivisto, J.-M.; Cowley, B.U. Design of generative AI-powered pedagogy for virtual reality-based higher education. npj Sci. Learn. 2025, 10, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chardonnens, S. Adapting educational practices for Generation Z: Integrating metacognitive strategies and artificial intelligence. Front. Educ. 2025, 10, 1504726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Altamirano, F.R.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, E.M. Learning preferences in Generation Z college students. Rev. Electrón. Educ. 2025, 29, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Kuek, F.; Feng, W.; Cheng, X. Digital learning in the 21st century: Trends, challenges, and innovations in technology integration. Front. Educ. 2025, 10, 1562391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.