Abstract

The escalating global water crisis demands the development of cost-effective and environmentally sustainable treatment technologies. Among various advanced oxidation processes (AOPs), peracetic acid (PAA) has emerged as a promising oxidant, owing to its high redox potential, chemical stability, and potent disinfection capability. Nevertheless, the lack of highly efficient catalysts remains a major obstacle to achieving the effective degradation of contaminants of emerging concern in wastewater. Heterogeneous catalysis has proven to be a viable strategy for enhancing PAA activation, highlighting the urgent need for catalysts with superior activity, stability, and recyclability. Metal–organic frameworks (MOFs), with their large surface areas, tunable porosity, and structural diversity, provide versatile platforms for catalyst design. Recently, MOF-derived materials have attracted increasing attention for PAA activation, offering a new frontier in advanced oxidation technologies for efficient and sustainable wastewater remediation. This review systematically examines the role of MOFs in PAA activation, from pristine frameworks to MOF-based composites and MOF-derived catalysts. Mechanistic insights into PAA activation are highlighted, strategies for engineering MOF-based composites with synergistic catalytic properties are discussed, and the transformation of MOFs into robust derivatives with improved stability and reactivity is explored. Special attention is given to the identification and quantification of reactive species generated in PAA systems, providing a critical understanding of reaction pathways and catalytic performance. Finally, current challenges and future directions are outlined for designing highly efficient, recyclable, and environmentally compatible MOF-based catalysts, emphasizing their potential to significantly advance PAA-based AOPs.

1. Introduction

The increasing presence of contaminants of emerging concern (CECs) in aquatic environments, including pharmaceuticals, personal care products, and endocrine-disrupting compounds, poses a significant risk to both ecosystems and human health, even at very low concentrations [1,2]. These compounds are typically refractory to conventional biological treatments and persist in water streams due to their chemical stability and resistance to biodegradation [1]. Consequently, the development of efficient and cost-effective water treatment technologies has become urgently necessary.

Among emerging approaches, peracetic acid-based advanced oxidation processes (PAA-AOPs) have attracted considerable attention due to their high reactivity and potential for removing CECs [3]. Over the past decade, research on PAA-AOPs has intensified, as evidenced by the exponential growth in publications and citations [4]. Compared with conventional oxidants such as chlorine, PAA offers several advantages, including high disinfection efficiency [5,6], reduced pH dependence [7], and lower formation of harmful disinfection byproducts [8]. Furthermore, PAA exhibits a high redox potential (1.06–1.96 V) and a relatively low O-O bond dissociation energy (159 kJ/mol) compared with peroxymonosulfate (PMS, 317 kJ/mol) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2, 213 kJ/mol), indicating a lower energy requirement for its activation [9,10]. PAA is a human-made chemical synthesized through the equilibrium reaction between acetic acid and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) in the presence of an acid catalyst, typically sulfuric acid [11]. Commercial PAA formulations are equilibrium mixtures containing PAA, acetic acid, H2O2, and water. The concentration of PAA in these solutions is generally in the range of 5–15% [12], as higher concentrations (>15%) may exhibit increased instability, reactivity, and even explosive behavior [13]. The molar ratio of PAA to H2O2 in commercially available formulations typically ranges from 0.1 to 3.0 [14]. Notably, residual H2O2 present in equilibrium PAA solutions can also act as an oxidant and disinfectant.

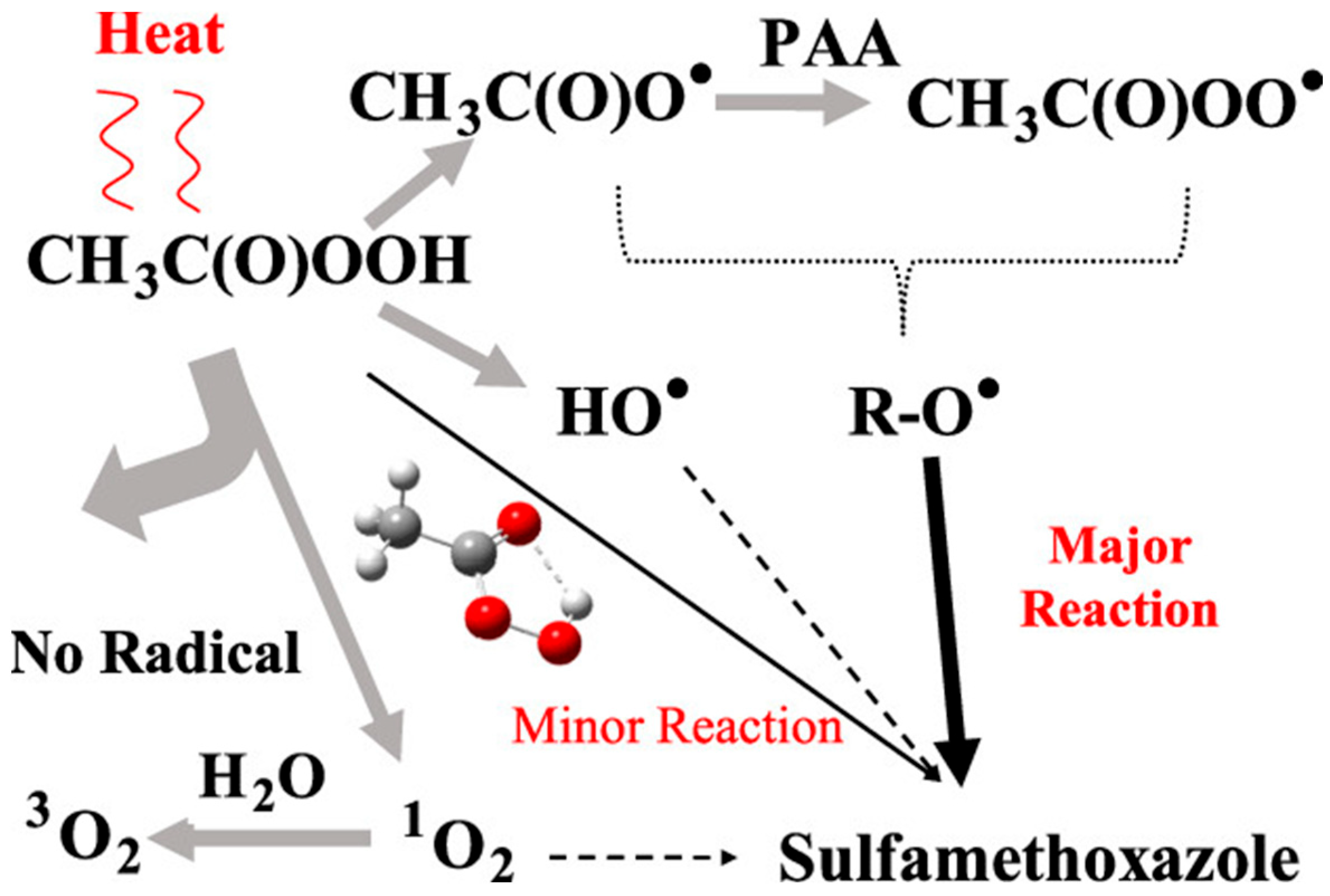

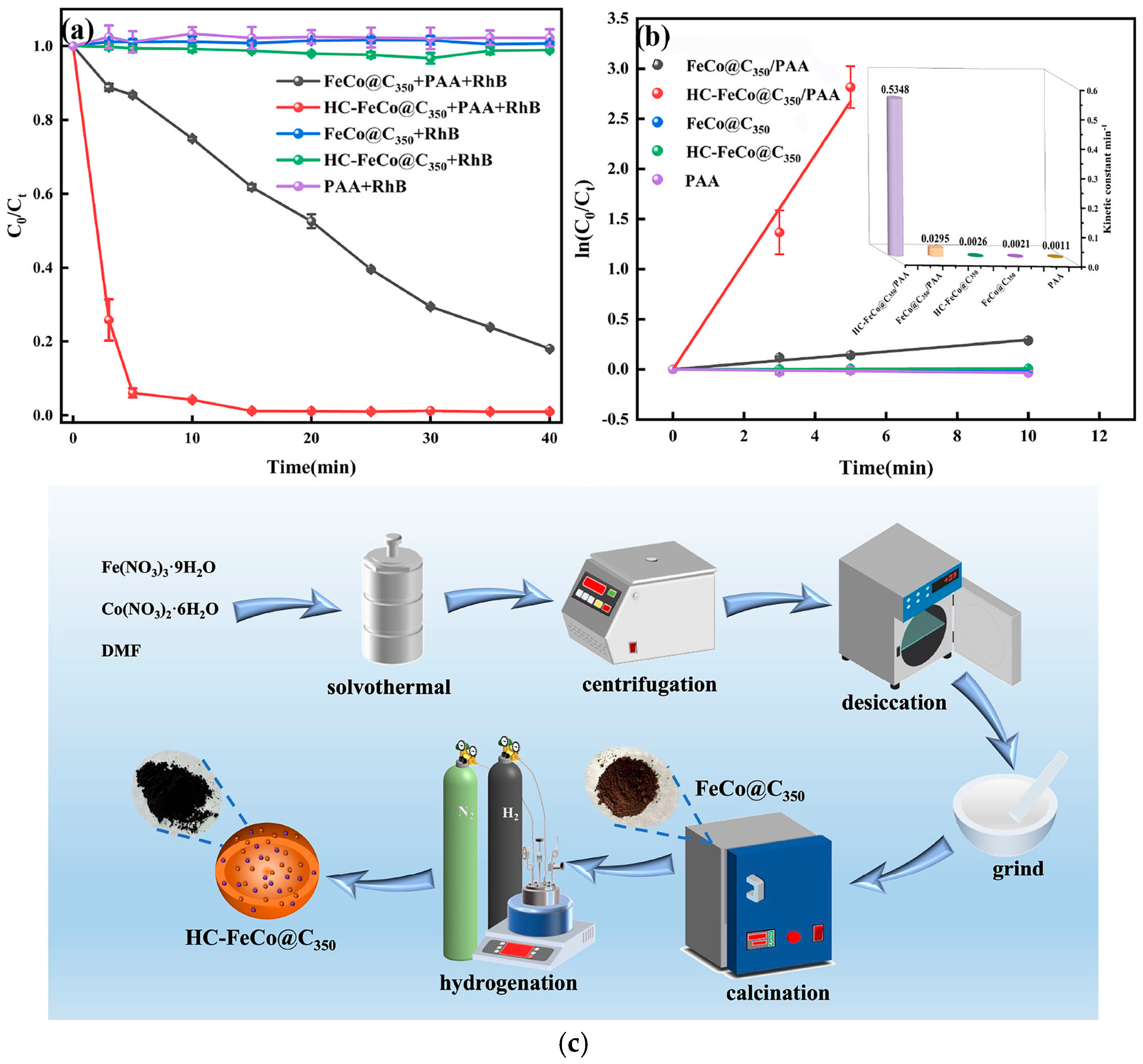

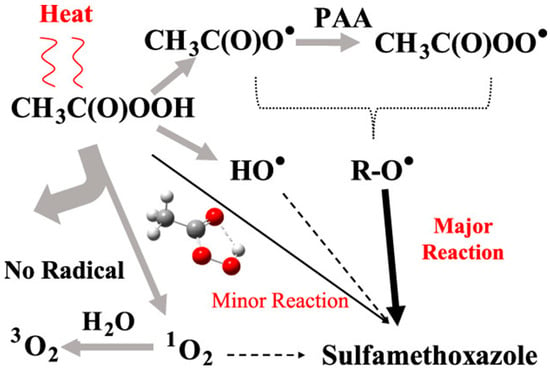

To date, various methods have been applied to activate PAA, including direct energy inputs such as UV, heat, or ultrasound, as well as homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysts. Figure 1 illustrates the thermal activation pathway of PAA and its application to degrade CECs such as sulfamethoxazole (SMX) [15]. Upon activation, PAA can undergo homolytic cleavage to generate reactive species, including hydroxyl radicals (•OH) and oxygen-centered radicals (e.g., acetoxyl (CH3C(O)O•) and acetyl peroxyl (CH3C(O)OO•)). Catalyst-assisted PAA activation has proven more efficient and cost-effective than other approaches due to its operational simplicity, energy efficiency, and potential for recyclability. However, ensuring both catalytic efficiency and long-term stability remains a major challenge. Chemical catalysts for PAA activation can be classified by composition (metal-based vs. metal-free) and by morphology (heterogeneous vs. homogeneous). Metal and metal oxide catalysts exhibit high activity but often raise concerns regarding secondary pollution caused by metal leaching. In contrast, carbon-based metal-free catalysts are more environmentally benign but generally exhibit lower catalytic performance. Consequently, developing novel strategies that integrate high catalytic efficiency with long-term stability is critical for advancing PAA-AOPs.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the thermal activation pathway of PAA and its subsequent application in the degradation of SMX. Reproduced with permission from ref. [15]. Copyright 2020 American Chemical Society.

MOFs constitute an emerging class of porous crystalline materials constructed from metal ions or clusters bridged by organic ligands [16]. Since their first definition by Yaghi and Li in 1995 [17], more than 100,000 distinct MOF structures have been synthesized, exhibiting exceptional diversity in both composition and architecture [18]. MOFs offer ultrahigh surface areas, precisely tunable frameworks, and well-defined active sites, which have demonstrated remarkable versatility across a wide spectrum of applications, encompassing adsorption [19], separation [20], energy storage [21,22], and catalysis [23,24]. Their structural adaptability and functional tunability position MOFs as next-generation catalysts with immense potential for environmental remediation and CEC degradation [25,26]. The application of MOFs in environmental catalysis has progressed rapidly over the past two decades. A major milestone was the synthesis of the highly stable chromium-based framework MIL-101 by Gérard Férey and co-workers in 2005 [27], which exhibited exceptionally large pore sizes and surface areas.

This work laid the foundation for exploring MOFs as efficient catalysts in AOPs. MOFs were first employed for PMS activation in 2015, marking a pivotal advance in sulfate radical-based oxidation systems [28]. More recently, their integration into PAA-AOPs has begun to emerge. The first MOF reported to activate PAA, zeolitic imidazolate framework (ZIF-67) was demonstrated in 2022, highlighting that the use of MOFs for PAA activation is a newly developing and promising research direction [29]. Building on this recent development, MOFs can specifically enhance the advantages of PAA in AOPs by providing a highly tunable and confined catalytic environment that optimizes oxidant utilization and reaction selectivity. The metal ions and organic linkers within MOFs can be deliberately selected to create well-defined coordination environments that act as efficient catalytic centers for PAA activation. In particular, the incorporation of single-metal or bimetallic nodes enables synergistic redox interactions that facilitate O-O bond cleavage in PAA and promote the controlled generation of reactive species through both radical and non-radical pathways. Simultaneously, the high surface area and porosity of MOFs provide abundant and accessible active sites, while their adjustable pore sizes induce confinement effects that increase the local concentration of PAA. Moreover, the hybrid organic–inorganic framework strengthens catalyst–oxidant interactions by anchoring PAA molecules near metal centers, thereby enhancing activation efficiency and reaction kinetics. Compared with conventional heterogeneous catalysts, MOFs can enable more efficient and selective PAA-based oxidation.

To the best of our knowledge, no comprehensive review currently addresses MOF-mediated PAA activation, underscoring a critical knowledge gap. To address this gap, this review is structured to provide a comprehensive understanding of MOF-based catalysts for PAA activation. First, a discussion of the fundamental principles of MOFs, including their structural diversity and tunable active sites, establishes the basis for catalytic performance. Next, pristine MOFs are examined for direct PAA activation, highlighting their advantages and limitations. Building on this, MOF-based composites are explored as strategies to enhance catalytic efficiency and stability. Subsequently, MOF-derived catalysts are discussed for their superior activity in PAA-based systems. Since the catalytic activity of PAA is mediated by reactive species, this review also summarizes the methods used to identify and quantify reactive oxygen species (ROS) in PAA-based systems. Finally, the current challenges, emerging trends, and future directions for the design of MOF catalysts in sustainable water treatment are summarized.

2. Structural Features, Properties, and Synthesis of MOFs

MOFs are a class of hybrid organic–inorganic materials distinguished by their porous crystalline architectures and the wide range of framework designs achievable [30,31,32]. They are constructed through the coordination of metal ions or metal-oxo clusters with multifunctional organic linkers, giving rise to tunable framework geometries and a wide diversity of structures. The metal centers can adopt various coordination environments, including tetrahedral, square-planar, trigonal-bipyramidal, and octahedral configurations, providing versatile platforms for catalytic design [33]. Meanwhile, the most commonly used organic linkers, such as polytopic carboxylates and aromatic heterocyclic molecules, facilitate robust coordination with metal nodes and enable fine control over pore size, topology, and chemical functionality [34].

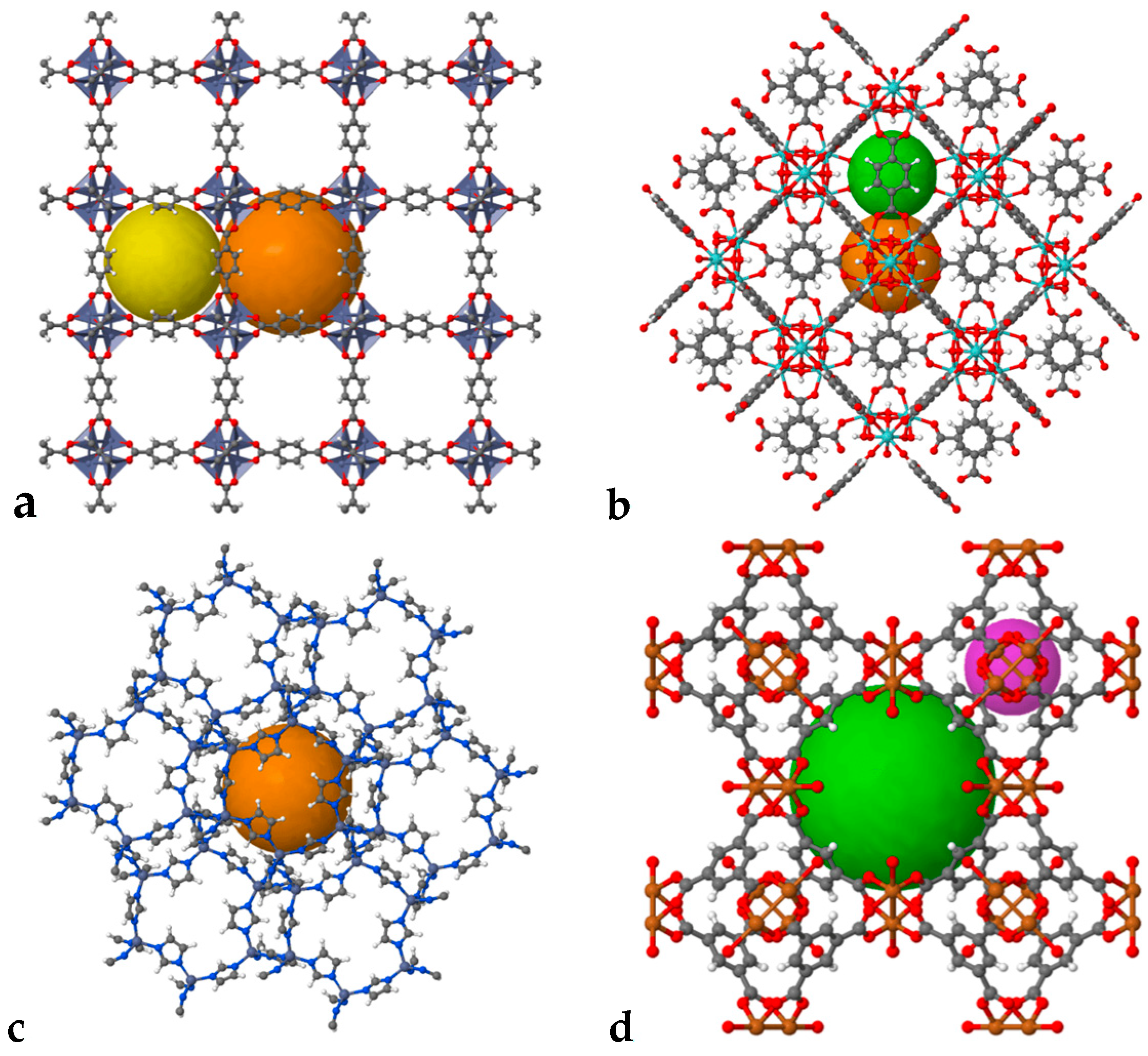

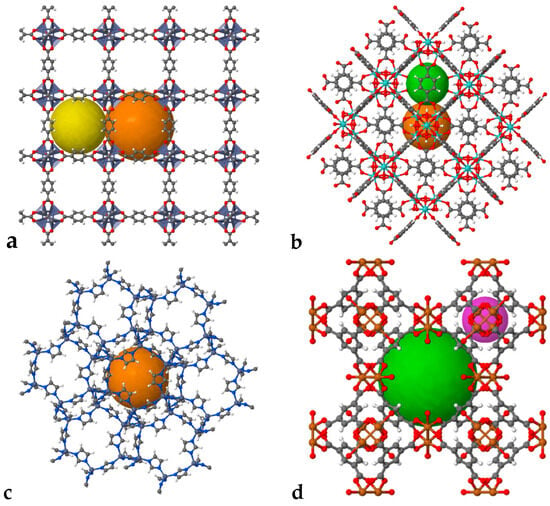

Building on these structural principles, the development of MOFs has progressed through several landmark discoveries that have shaped the evolution of the field. For the first time, Yaghi and co-workers reported a synergistic porous framework later termed a MOF constructed from 1,3,5-benzenetricarboxylic acid and cobalt, forming a stable 2D structure [35]. MOF chemistry rapidly evolved with the development of MOF-1 [17], MOF-2 [17], and related derivatives. In 1999, the introduction of MOF-5, a 3D framework composed of Zn nodes and terephthalic acid, marked a major breakthrough by transitioning from microporous to mesoporous MOFs, establishing a significant milestone in the field [36] (Figure 2). Around the same time, the Materials Institute Lavoisier (MIL) series, particularly MIL-53, was developed by Férey’s group and became notable for its large pores and high surface area [37]. Coordination pillared-layer MOFs introduced by Kitagawa featured a layered structure with “gate-opening” behavior [38]. In 2006, zeolitic imidazolate frameworks (ZIFs) were reported, combining MOF and zeolite properties and offering excellent chemical and thermal stability [39]. UiO-66, based on metallic zirconium nodes and reported by Lillerud in 2008, demonstrated exceptional stability under both acidic and alkaline conditions [40]. Additionally, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology-1 (HKUST-1) is an early example of a “pore-cage/pore channel” architecture. HKUST-1 features a 3D pore-channel system with a porosity of 40.7%, which is superior to that of most open-pore zeolites [40] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Different types of MOFs. (a) MOF-5; (b) UiO-66; (c) ZIF; (d) HKUST-1 (elaborated using ChemTube3D, https://www.chemtube3d.com/, accessed on 13 December 2025) [41].

Today, over 100,000 MOFs have been reported, synthesized from diverse metals (Cu2+, Zr4+, Zn2+, Al3+) and organic ligands, allowing precise control over size, surface chemistry, and functionality [18]. Initially used for gas storage, MOFs are now widely applied in catalysis, separation, and environmental remediation, including the removal of CECs such as heavy metals, dyes, antibiotics, and radioactive contaminants from water.

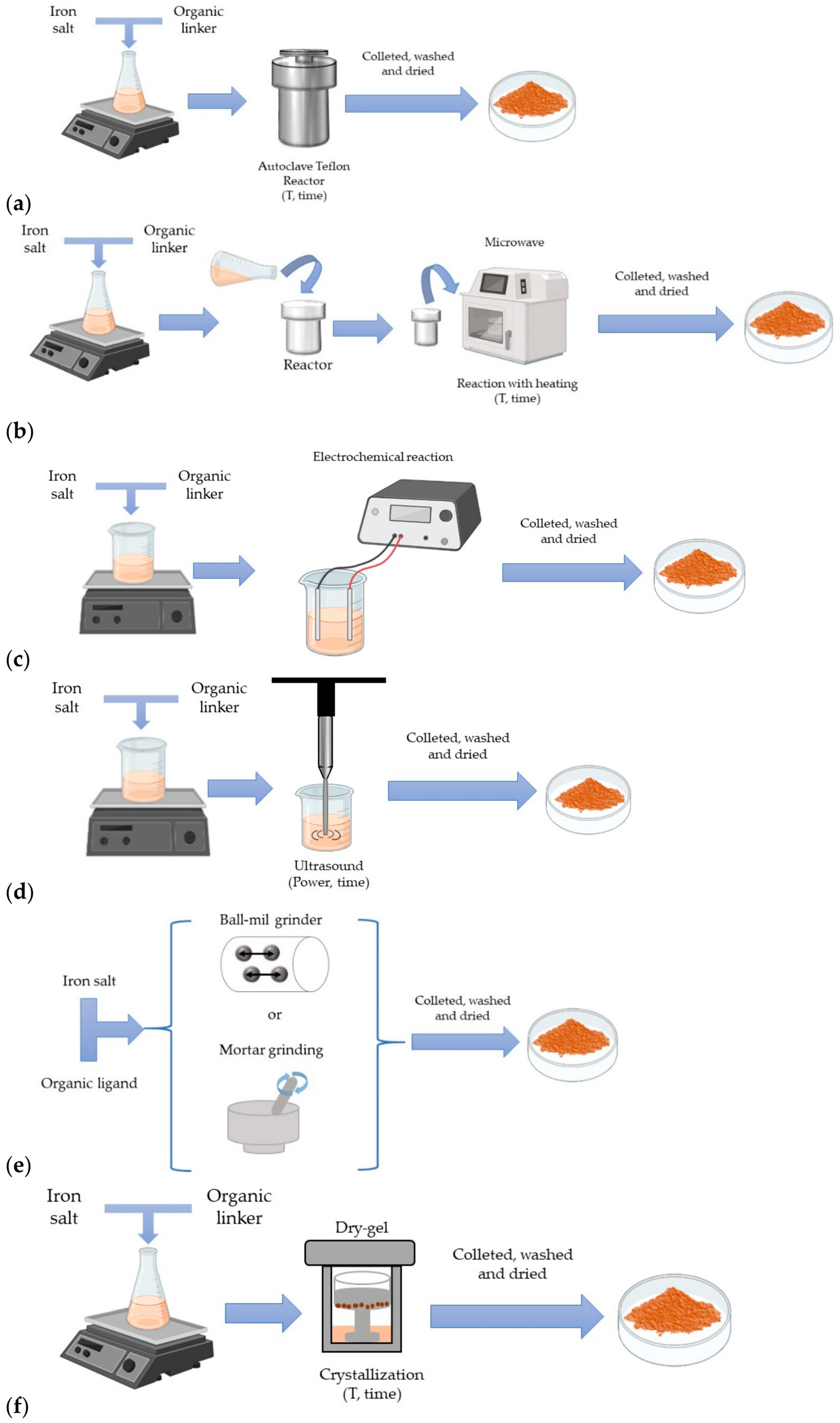

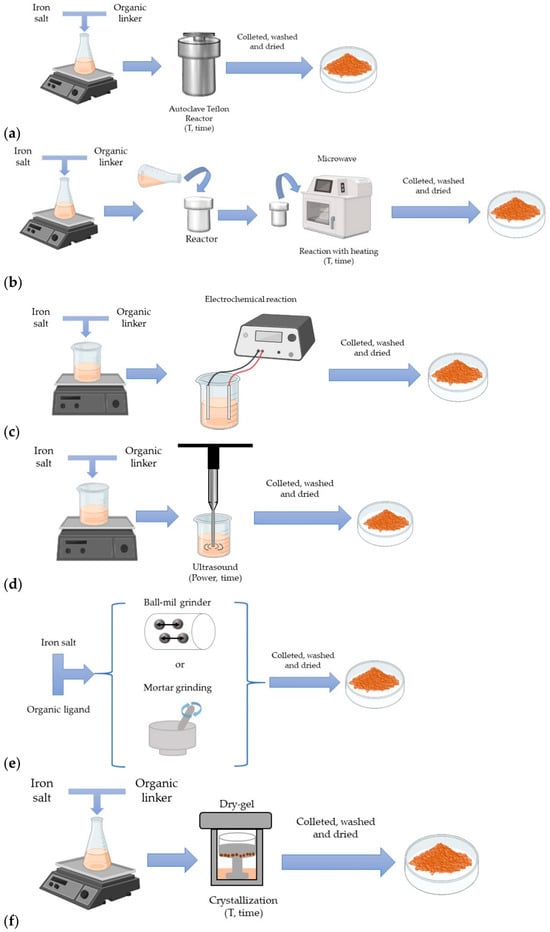

The remarkable structural diversity and tunable properties of MOFs have been made possible through the continuous development of various synthesis methodologies, which enable precise control over framework architecture and functionality. MOF synthesis approaches have continuously evolved, encompassing diffusion [42], solvothermal/hydrothermal [43], microwave-assisted [44], electrochemical [45], mechanochemical [46], and sonochemical approaches [47]. As an example, Figure 3 illustrates these different methods used for iron-based MOFs synthesis, which are comparable to those utilized for other MOF families [48]. Among these, hydrothermal and solvothermal techniques remain the predominant methods, due to their versatility and capacity to produce highly crystalline and stable frameworks. A clearer understanding of the advantages and limitations of each synthesis route is essential for selecting an appropriate strategy, as summarized in Table 1.

Figure 3.

Illustration of the different methods used for iron MOFs synthesis: (a) solvothermal/hydrothermal synthesis, (b) microwave-assisted synthesis, (c) electrochemical synthesis, (d) sonochemical synthesis, (e) mechanochemical synthesis, (f) dry-gel synthesis. Reproduced from [48].

Table 1.

Comparison of MOF synthesis methods: Strengths and Drawbacks.

3. Pristine MOFs in PAA Activation

Given the novelty of this field, only a few studies have been published on using MOFs directly to activate PAA and degrade pollutants. In 2022, Duan et al. [29] reported the first example: the MOF ZIF-67 was used to activate PAA for the degradation of the antibiotic sulfachloropyridazine (SCP). The results were remarkable: with just 50 µM of PAA and 0.05 g/L of ZIF-67, they achieved complete (100%) removal of SCP (10 µM) in only 3 min at neutral pH. Remarkably, ZIF-67 achieved a rate constant (k) that was 34.2 times higher than that of conventional Co3O4 nanoparticles, an enhancement attributed to its high surface area, uniform cobalt active sites, and well-defined porous architecture. The proposed mechanism indicates that Co(II) sites in ZIF-67 catalyze the homolytic cleavage of PAA, generating CH3C(O)OO• radicals as the dominant oxidizing species, with minimal formation of •OH. In this sense, ZIF-67 behaves similarly to other cobalt-based catalysts, favoring the production of PAA-derived organic radicals, which are more selective, over hydroxyl radicals [49]. The authors pointed out that the main active site was the Co(II) coordinated in the framework (bound to 2-methylimidazole ligands), and that the excellent performance can be attributed to the high dispersion and accessibility of these Co centers in ZIF-67’s porous structure [29].

Beyond demonstrating high activity toward SCP degradation, subsequent investigations have further clarified the mechanistic pathways underlying ZIF-67-mediated PAA activation. In 2024, Tan’s group [50] reported that ZIF-67 efficiently degrades bisphenol A (BPA) through the formation of a Co(II)-PAA complex, which serves as the key precursor for generating multiple reactive radical species [50]. The catalytic system displayed remarkable operational robustness, maintaining high degradation efficiency across both acidic and neutral pH conditions and exhibiting strong tolerance to typical water matrix constituents, including HCO3−, Cl−, NO3−, SO42−, and humic substances. Similarly, Pan et al. [51] demonstrated that amino-functionalized MIL-101(Fe)-NH2 efficiently activates PAA, enabling rapid degradation of (SMX) within 30 min. In this system, Fe(IV)=O species, formed via a thermodynamically favored four-electron transfer pathway, dominate the reaction, while nonselective organic radicals are suppressed. This selective mechanism ensures strong resistance to water matrix interference and effective degradation of diverse CECs. Increasing the MIL-101(Fe)-NH2 dosage from 50 to 200 mg/L enhanced SMX removal from 71% to 97%, underscoring the catalyst’s high activity and tunability.

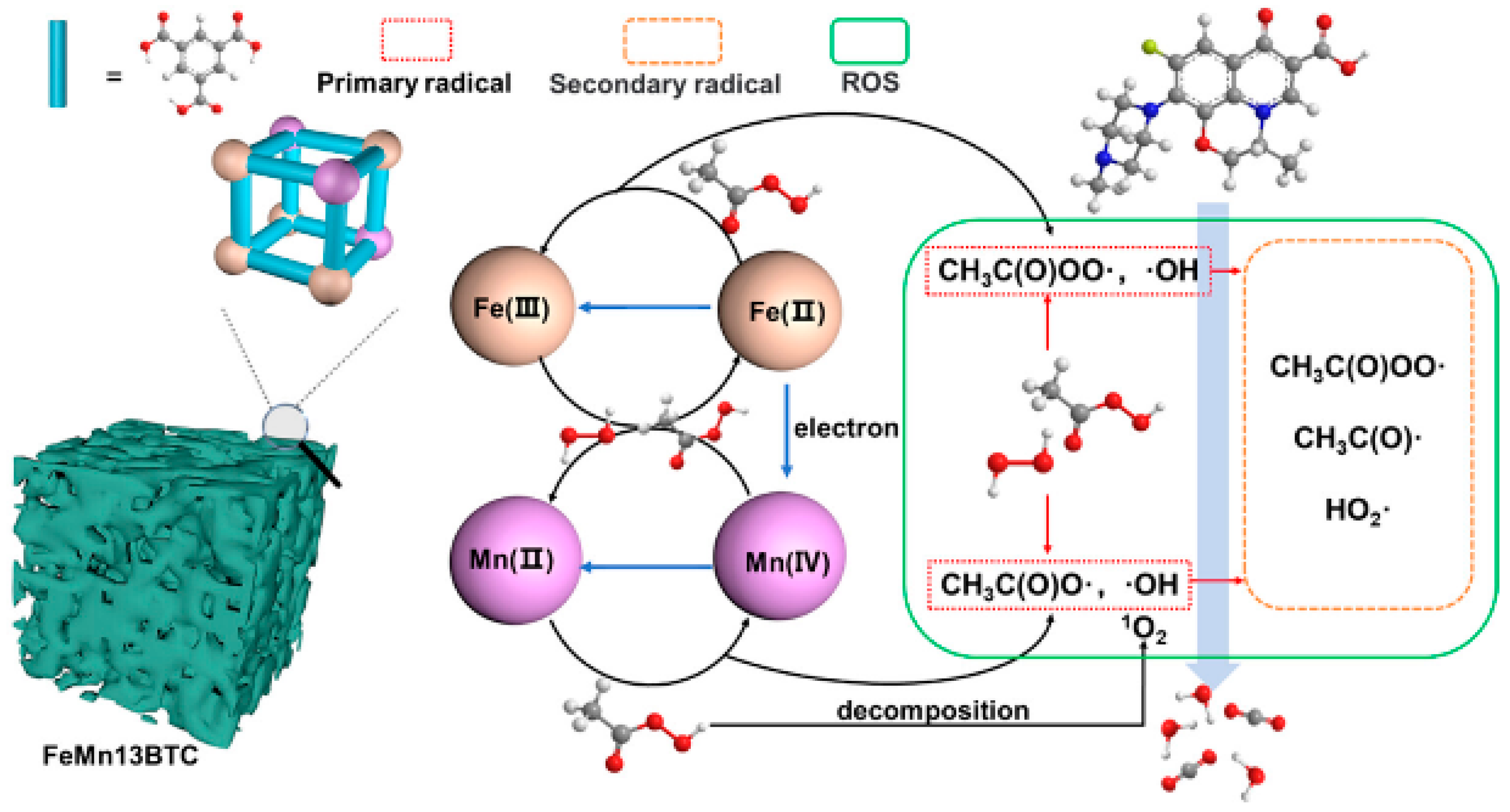

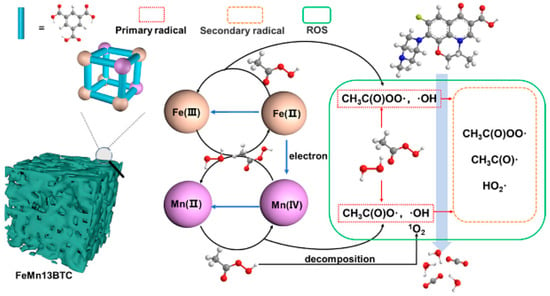

To further elevate the catalytic performance of pristine monometallic MOFs, pristine bimetallic MOFs (BMOFs) have emerged as a highly effective strategy. By incorporating two distinct metal ions into the framework, BMOFs simultaneously augment the density and accessibility of active sites, reinforce structural stability, and enhance catalytic efficiency through synergistic metal-metal interactions [52]. Moreover, the presence of multiple metal centers introduces additional redox-active sites, providing BMOFs with enhanced catalytic versatility and reactivity [53,54]. Illustrating this concept, Zheng and co-workers [55] reported the fabrication of a bimetallic hierarchical porous FeMn13BTC through a facile one-pot synthesis for the catalytic degradation of ofloxacin (OFX) (Figure 4). The optimized FeMn13BTC/PAA system achieved 81.85% OFX degradation within 1 h, clearly outperforming both the PAA-only system and the monometallic FeBTC/PAA system (56.78% within 1 h). This 38% improvement highlights the strong Fe-Mn bimetallic synergy. The enhanced catalytic activity was attributed to the hierarchical porous architecture and the cooperative interactions between Fe and Mn centers, which collectively promoted ROS generation. Mechanistic analyses combining radical quenching and electron spin resonance spectroscopy identified CH3C(O)OO• as the predominant ROS.

Figure 4.

Underlying catalytic mechanisms of PAA activation by FeMn13BTC. Reproduced from [55], used under a Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 license. Copyright 2023 American Chemical Society.

Moreover, Zhou et al. [56] synthesized a bimetallic MOF(Fe-Co) via a hydrothermal method and demonstrated its outstanding capability for PAA activation toward SMX degradation. Under neutral conditions, the MOF(Fe-Co)/PAA system achieved 86.4% SMX removal within 30 min, whereas MIL-100(Fe)/PAA showed negligible activity. In line with this enhanced catalytic performance, mechanistic analyses revealed that MOF(Fe-Co) selectively converts PAA into organic radicals (CH3C(O)OO• and CH3C(O)O•), which dominate the oxidation pathway. Notably, the efficiency of this radical-driven process is strongly influenced by water constituents, with Cl− enhancing SMX degradation, and HCO3− or natural organic matter markedly suppressing it. Furthermore, Fang et al. [6] synthesized pristine bimetallic MOF(Fe-Co) via a hydrothermal method and evaluated its performance in combination with PAA for the degradation of bezafibrate (BZF) as a target CECs. The MOF(Fe-Co)/PAA system achieved 98.1% BZF removal within 60 min using 10 mg/L PAA and 25 mg/L of catalyst. Notably, MOF(Fe-Co) exhibited excellent stability and reusability, maintaining over 90% removal efficiency across eight consecutive cycles.

4. MOF-Based Composites for Enhanced PAA Activation

Pristine MOFs possess well-defined active sites and ordered pore architectures, yet their practical deployment is often hindered by structural instability, metal leaching, limited catalytic durability, and restricted electron-transfer efficiency [57]. To address these shortcomings, MOF-based composites have emerged as a powerful design strategy, offering markedly enhanced catalytic activity, stability, and operational robustness compared with their pristine counterparts [58]. These composite systems leverage synergistic interactions between MOF scaffolds and incorporated components, such as metals, metal oxides, carbon materials, or nanoparticles [59], resulting in improved electron conductivity, accelerated redox cycling, and more efficient reactant activation. Moreover, the supporting matrices not only stabilize the MOF framework but also promote homogeneous dispersion and greater exposure of active sites [60], thereby enhancing catalytic performance. Collectively, the integration of complementary functionalities across multiple components enables MOF-based composites to overcome the intrinsic limitations of pristine MOFs and achieve superior efficiency in AOPs.

A notable example was reported by Guo et al. [57] who developed a core–shell magnetic catalyst (Fe3O4@ZIFs) by assembling Fe3O4 nanoparticles within a bimetallic Co/Zn-ZIFs shell to activate PAA for SMX degradation. The catalyst was synthesized via an in situ hydrothermal route. During PAA activation, the Fe3O4@ZIFs/PAA system achieved 99.3% SMX removal within 30 min. Mechanistic studies, including quenching experiments and electron paramagnetic resonance, indicated that SMX oxidation proceeded mainly via CH3C(O)OO• radicals and singlet oxygen (1O2). The composite exhibited outstanding stability, retaining catalytic performance over four consecutive cycles.

Building on this evidence of the benefits of integrating MOFs with functional supports, a compelling example of MOF-based composites for PAA activation was reported by Nguyen et al. [58] who synthesized a novel composite catalyst by anchoring ZIF-67 onto sodium-bicarbonate-modified biochar derived from kumquat peels (ZIF-67@KSB3). This composite exhibited outstanding catalytic performance, achieving 94.3% removal of acetaminophen (APAP) using 200 mg/L catalyst and 0.4 mM PAA at pH 7. Beyond its high activity, ZIF-67@KSB3 demonstrated remarkable stability and reusability. Over five consecutive cycles, its APAP removal efficiency remained above 86%, whereas pristine ZIF-67 rapidly deactivated, dropping from 53.6% in the first cycle to only 14.4% in the fifth. Furthermore, cumulative Co release from ZIF-67@KSB3 stayed below 70 µg/L after five cycles, in stark contrast to the 958.6 µg/L leached by pristine ZIF-67 in a single cycle.

Extending the concept of engineered composites for enhanced PAA activation, Wang et al. [61] developed an electron-optimized CoFe alloy-carbon composite (CoFeC) via pyrolyzing of CoFe Prussian blue analogs (CoFe PBAs). This approach yielded a well-defined core–shell architecture consisting of a CoFe alloy core encapsulated within a carbon shell. Electronic structure analysis revealed that the incorporation of C and Fe effectively narrowed the gap between the Co d-band center and the Fermi level, reducing PAA adsorption energy and accelerating electron transfer at the Co active sites. When applied to PAA activation, the CoFeC/PAA system achieved nearly 100% SMX removal within 30 min and displayed strong resistance to interference along with excellent durability in continuous-flow operation [53].

Recent research has increasingly emphasized the development of environmentally friendly catalysts that combine high efficiency with operational stability for wastewater treatment. In this context, Tang and co-workers [62] synthesized a CoFe/U-ZrO2 catalyst by loading CoFe onto UiO-66 derived ZrO2 (U-ZrO2) via a sol–gel method, effectively addressing the persistent issue of toxic metal leaching that often limits the practical application of heterogeneous metal catalysts in PAA activation. Notably, cobalt leaching from the CoFe/U-ZrO2/PAA system was as low as 0.005 mg/L, in stark contrast to the CoFe/PAA system, where Co and Fe leaching reached 0.354 mg/L and 0.426 mg/L. The CoFe/U-ZrO2/PAA system also exhibited outstanding catalytic performance, achieving 98.9% removal of SMX within 10 min, with CH3C(O)OO• identified as the dominant ROS through quenching experiments, probe studies, and electron paramagnetic resonance analysis. Another promising strategy for enhancing PAA activation is the construction of bimetallic MOF-based composites. A Co/Cu-based bi-MOF catalyst was synthesized through a facile room-temperature method and applied to the degradation of the antibiotic SMX [63]. Compared with its single-metal counterparts-Cu-based HKUST-1 and Co-based ZIF-67, the Co4Cu6-MOF exhibited markedly superior catalytic activity. Under optimal conditions (20 mg/L catalyst, 200 μmol/L PAA, pH 7), the composite achieved over 92% SMX removal within just 5 min, demonstrating significantly accelerated oxidation kinetics. Mechanistic investigations further confirmed that CH3C(O)OO• radicals were the dominant ROS responsible for pollutant degradation.

5. MOF-Derived Catalysts for PAA Activation

Pristine MOFs and MOF composites can act as efficient catalysts for PAA activation. Beyond their direct catalytic use, MOFs can also be transformed into nanoporous metal oxides, metal/carbon hybrids, or carbonaceous materials through controlled calcination and pyrolysis processes [64,65]. Specifically, pyrolysis under an inert atmosphere (e.g., N2 or Ar) yields nanoporous metal/carbon composites, while subsequent etching of residual metals can produce high-surface-area porous carbons [64,65]. In contrast, direct heat treatment in air generates porous metal oxides [66,67]. These MOF-derived architectures preserve the inherent porosity and metal dispersion of the parent framework while providing significantly enhanced thermal stability, electrical conductivity, and chemical durability.

Building on the advantages of these MOF-derived materials, recent studies have demonstrated their strong potential in PAA-based oxidation systems. For example, Zhang et al. [68] employed Fe-doped ZIF-8 as a precursor to synthesize nitrogen-doped carbon-supported FeSiO4 (Fe2SiO4-NC) via a SiO2 protection strategy for PAA activation in the degradation of tetracycline (TC). The incorporation of SiO2 markedly improved the stability and reactivity of Fe2SiO4-NC. Its more negative value (−1.14 eV vs. −0.42 eV for FeO) confirms higher thermodynamic stability, as silicon strengthens the iron-oxide framework and enhances resistance to PAA acidity and ROS, resulting in minimal Fe leaching. Moreover, SiO2 incorporation lowers the orbital transition energy: Fe2SiO4 exhibits a smaller band gap (0.17 eV vs. 0.42 eV for FeO), enabling easier electron excitation. This reduced band gap enhances molecular adsorption and accelerates redox processes [69,70], thereby promoting more efficient PAA activation.

Degradation experiments demonstrated that 40 μM TC was completely removed within 10 min using 0.06 g/L Fe2SiO4-NC and 0.15 mM PAA, achieving a rate constant kobs of 0.40 min−1. Moreover, Fe2SiO4-NC exhibited excellent recyclability, maintaining over 90% TC removal across six consecutive cycles, with Fe leaching remaining below 0.3 mg/L. FTIR analysis further confirmed the structural robustness of the catalyst: the characteristic peaks of Fe2SiO4-NC showed negligible variation before and after the reaction, and its surface functional groups were well preserved. These results collectively demonstrate the excellent structural stability and reusability of Fe2SiO4-NC, underscoring its strong potential for practical applications. Quenching experiments and electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) analyses revealed that TC degradation in the Fe2SiO4-NC/PAA system was primarily mediated by CH3C(O)OO• radicals. Mechanistic investigations further indicated that Fe redox cycling, together with surface Si–OH groups, facilitated efficient PAA activation. Compared with previously reported Fe-based catalysts, the Fe2SiO4-NC/PAA system demonstrates superior stability, reusability, and practical applicability.

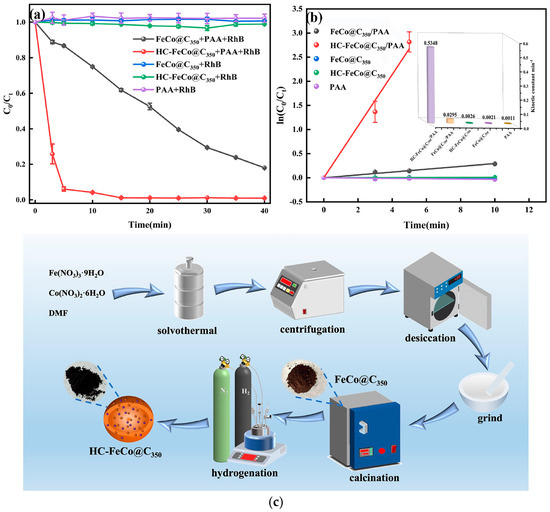

Additionally, Tan et al. [71] developed a hydrogenated FeCo-MOF-derived catalyst (HC-FeCo@C350) for PAA activation to efficiently degrade dye-contaminated wastewater, using Rhodamine B (RhB) as a model pollutant. A schematic illustration of the catalyst synthesis procedure is shown in Figure 5. The HC-FeCo@C350/PAA system achieved 99.33% removal within 20 min, exhibiting a reaction rate constant approximately 18 times higher than that of its non-hydrogenated counterpart (Figure 5). Mechanistic investigations, including quenching experiments, EPR analyses, and density functional theory (DFT) calculations, confirmed that HC-FeCo@C350 effectively activates PAA to generate 1O2, CH3C(O)O•, and CH3C(O)OO•. The catalyst also exhibited strong durability, retaining more than 80% of its activity after four consecutive cycles. Magnetic hysteresis measurements revealed a saturation magnetization of 69 emu/g, enabling rapid magnetic separation and facilitating catalyst recovery and reuse.

Figure 5.

(a) Comparative catalytic degradation of RhB in various systems. (b) Pseudo-first-orderrate modeling. (c) Schematic representation of the preparation of the HC-FeCo@C350 catalyst. Reproduced with permission from ref. [71]. Copyright 2021 American Chemical Society.

Furthermore, comparison with other PAA-activated metal-based catalysts (Table 2) highlights the competitive or superior removal efficiency and enhanced cycling stability of MOF-derived materials, underscoring their advantages over many conventional metal oxides and carbon-based catalysts [72].

Lu et al. [73] synthesized a cobalt–nitrogen–doped porous carbon material (Co-NC-700) through direct thermal carbonization of ZIF-67 under a nitrogen atmosphere and applied it as an efficient PAA activator for norfloxacin (NX) degradation. The Co-N-C-700/PAA system achieved rapid NX removal over a broad pH range. Both cobalt species and surface functional groups on Co-NC-700 served as the principal active sites for PAA activation. 1O2 dominated the degradation mechanism, while •OH, CH3C(O)O•, CH3C(O)OO•, and Co(IV) played secondary but non-negligible roles. Optimal degradation performance was obtained at a Co–NC–700 dosage of 0.05 g/L, a PAA concentration of 1.2 mM, and pH 7. Among the coexisting species, HCO3−, PO43−, and humic acid exerted strong inhibitory effects than Cl−, SO42−, and NO3−. Co–NC–700 also demonstrated excellent stability and minimal Co leaching during PAA activation, along with strong resistance to interfering constituents in real water matrices.

Table 2.

Degradation efficiencies of CECs by PAA-activated metal-based catalysts.

Table 2.

Degradation efficiencies of CECs by PAA-activated metal-based catalysts.

| Catalyst | Catalyst Concentration | Initial Pollutant Concentration | PAA Dosage | Reusability | Reaction Time (min) | Removal Efficient (%) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZIF-67 | 0.05 g/L | [Sulfachloropyridazine] = 10 μM | 50 μM | - | 3 | 100 | [29] |

| ZIF-67 | 0.1 g/L | [Bisphenol A] = 0.1 mM | 5 mM | - | 30 | 93 | [50] |

| MIL-101(Fe)-NH2 | 200 mg/L | [Sulfamethoxazole] = 10 μM | 1000 μM | 4 | 30 | 97 | [51] |

| FeMn13BTC | 0.1 g/L | [Ofloxacin] = 5 mg/L | 1.034 mM | 4 | 60 | 81.85 | [55] |

| MIL-100(Fe)Co | 0.05 g/L | [Sulfamethoxazole] = 5 μM | 50 μM | 3 | 30 | 84.6 | [56] |

| MOF-(Fe1,Co1) | 25 mg/L | [Bezafibrate] = 1 mg/L | 10 mg/L | 8 | 60 | 98.1 | [6] |

| Fe3O4@ZIFs | 0.01 g/L | [Sulfamethoxazole] = 10 μM | 0.1 mM | 4 | 30 | 99.3 | [57] |

| ZIF-67@KSB3 | 200 mg/L | [Acetaminophen] = 0.2 mM | 0.4 mM | 5 | 30 | 94.3 | [58] |

| CoFeC | 0.1 g/L | [Sulfamethoxazole] = 10 μM | 0.4 mM | 5 | 30 | 96.97 | [61] |

| CoFe/U-ZrO2 | 0.1 g/L | [Sulfamethoxazole] = 20 μM | 350 μM | 4 | 10 | 98.9 | [62] |

| Co4Cu6-MOF | 20 mg/L | [Sulfamethoxazole] = 10 μM | 200 μM | 4 | 5 | 92 | [63] |

| Fe2SiO4 | 0.06 g/L | [Tetracycline] = 40 μM | 0.15 mM | 6 | 10 | 100 | [68] |

| HC-FeCo@C350 | 0.1 g/L | [RhB] = 30 mg/L | 0.4 mM | 4 | 30 | 99.5 | [71] |

| CoFe2O4 | 0.5 g/L | [RhB] = 20 mg/L | 0.8 mM | 4 | 10 | 95 | [72] |

| Co(II) | 10 μM | [Carbamazepine] = 15 μM | 100 μM | - | 5–30 | 47.5–100 | [74] |

| Co3O4 | 0.1 g/L | [Orange G] = 0.05 mM | 1g/L | 4 | 90 | 100 | [75] |

| Fe-biochar | 0.3 g/L | [Acid orange] = 0.143 mM | 1.1 mM | 5 | 25 | 93.3 | [76] |

| BC-CoFe2O4 | 0.3 g/L | [Carbamazepine] = 1 mg/L | 0.8 mM | 3 | 20 | 100 | [77] |

| CuCo2O4 | 0.2 g/L | [BPA] = 20mg/L | 400 μM | 4 | 60 | 92.3 | [78] |

| Co-NC-700 | 0.05 g/L | [Norfloxacin] = 60 μM | 1.2 mM | 5 | 35 | 95 | [73] |

| Co-Fe-O | 0.1 g/L | [Sulfamethazine] = 20 μM | 0.4 mM | 4 | 25 | 100 | [79] |

To enhance catalytic performance, Jiang et al. [79] developed a Co-Fe bimetallic oxide (Co-Fe-O) derived from Prussian blue analogs (PBA) by calcining a Co-Fe-PBA precursor in air. The resulting material functioned as an efficient PAA activator, enabling rapid sulfamethazine (SMZ) degradation across a wide pH range (5–9). Using SMZ (20 μM) as the model contaminant, the oxidation efficiency of the Co-Fe-O/PAA system increased further with higher dosages of both PAA and Co-Fe-O. Correspondingly, CH3C(O)OO• and CH3COO• were identified as the dominant radicals driving PAA activation and subsequent SMZ degradation. Moreover, the catalyst retained excellent activity over four cycles, confirming that its crystal structure and functional groups remained stable after the reactions.

6. Identification of Reactive Species in Catalytic PAA Activation Systems

In catalytic PAA activation systems, identifying the reactive species is essential for understanding degradation pathways and optimizing catalytic design. The dominant reactive species generated during pollutant oxidation depend strongly on the activation route and the molecular structure of the contaminant [80,81]. In MOF-based catalysts, PAA can be activated through multiple pathways, including metal-centered redox cycling, ligand-mediated electron transfer, or carbon-site activation, leading to the formation of a diverse set of radicals and non-radical oxidants. Typical species include organic radicals such as CH3C(O)OO• and CH3COO•, ROS (•OH, O2•−, and 1O2), and high-valent metal-oxo intermediates. These species and their interconversion pathways are summarized in Equations (1)–(11) [68,81]:

CH3C(O)OOH + Me(n−1)+ → CH3C(O)O− + Men+ + •OH

CH3C(O)OOH + Me(n−1)+ → CH3C(O)O• + Men+ + OH−

CH3C(O)OOH + Men+ → CH3C(O)OO• + Me(n−1)+ + H+

CH3C(O)OOH + CH3C(O)O• → CH3C(O)OO• + CH3C(O)OH

CH3C(O)O• → •CH3 + CO2

•CH3 + O2 → CH3(O)O•

CH3C(O)O• + CH3C(O)O• → (CH3C(O)O)2

CH3C(O)OO• → CH2CO + O2•− + H+

2O2•− + 2H+ → 1O2 + H2O2

O2•− + Men+ → 1O2 + Me(n−1)+

CH3C(O)OOH + •OH → CH3C(O)OO• + H2O

The relative contribution of each species varies across systems and is commonly elucidated using a combination of complementary techniques, including EPR spectroscopy, radical quenching experiments, and probe-based kinetic analyses. The integration of multiple approaches is critical, as no single method can unambiguously identify all reactive pathways in PAA-based AOPs.

6.1. Scavengers and Chemical Probes

Scavenger and chemical probe experiments are among the most widely used strategies to distinguish the contribution of individual species. These methods rely on adding selective quenchers that rapidly react with a target ROS, thereby suppressing its activity. By comparing degradation efficiencies before and after scavenger addition, the relative contribution of each quenched species can be inferred. In MOFs/PAA process, various quenchers have been employed to probe specific radical or non-radical species [79]. Tert-butyl alcohol (TBA) is commonly used for •OH due to its high reaction rate constant with •OH and negligible reactivity with most other species. Methanol (MeOH), with its broader reactivity spectrum, can quench both •OH and organic radicals, while 2,4-hexadiene (2,4-HD) also effectively traps alkoxyl species. For 1O2, furfuryl alcohol (FFA) and L-histidine (L-His) are widely applied, owing to their high selectivity and fast reaction kinetics with 1O2. Meanwhile, p-benzoquinone (p-BQ) is used to quench superoxide radicals (O2•−), helping distinguish the role of electron-transfer pathways involving oxygen activation. Recent advances have expanded the toolkit of scavengers for PAA systems. Notably, in 2022, Zhang et al. [81] reported that manganese ions (Mn2+) function as a specific quencher for CH3C(O)OO• in PAA-based AOPs, providing a powerful probe to detect this key intermediate, which traditionally lacked a reliable and selective scavenger. The reaction kinetics of various frequently applied scavengers are listed in Table 3.

Despite their widespread use, scavenger experiments must be interpreted with caution. A fundamental requirement is that the added quencher reacts exclusively, or at least preferentially with the target species. If the quencher participates in side reactions, alters catalyst surfaces, or interacts with the pollutant, it may distort the results and lead to erroneous conclusions. Therefore, selecting appropriate concentrations, validating selectivity, and combining scavenger tests with complementary techniques are essential for accurate ROS identification in PAA-based systems.

Chemical probe tests are widely used to identify the types and quantify the activity of active substances. These experiments rely on adding trace amounts of probe molecules and analyzing their degradation products or transformation characteristics to infer the presence and contribution of specific active species. Among commonly used probes, para-chlorobenzoic acid (p-CBA) serves as a typical •OH probe due to its selective reactivity with •OH [6]. Methyl phenyl sulfoxide (PMSO) is employed as a probe for high-valence metal species. High-valence metals, such as Fe(IV) or Co(IV), oxidize PMSO to methyl phenyl sulfone (PMSO2) via oxygen atom transfer reactions, and the yield of PMSO2 can be used to estimate the proportion of high valence metal species relative to all active species in the system. It should be noted that •OH and alkoxyl radicals (R–O•) can react with PMSO to form hydroxylated products rather than PMSO2, which must be considered during data interpretation [82]. For R-C•, 2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-1-piperidinoxy (TEMPO) serves as a selective probe, where the signals of CH3COO-TEMPO (m/z = 216.1599) and methyl-TEMPO (m/z = 172.1696) can be detected using liquid chromatograph mass spectrometer analysis.

Table 3.

Summary of the reaction rate constants of widely applied scavengers (k, M−1s−1).

Table 3.

Summary of the reaction rate constants of widely applied scavengers (k, M−1s−1).

| Scavenger/Chemical Probe | •OH | RO•, RO2 | 1O2 | O2•− | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methanol (MeOH) | 9.7 × 108 | [73,76] | |||

| Ethanol (EtOH) | (1.2–2.8) × 109 | [29] | |||

| Tertbutyl alcohol (TBA) | (3.8–7.6) × 108 | 3.04 × 103 | [78,83] | ||

| 6.0 × 108 | [73,80] | ||||

| 2,4-hexadienoic (2,4-HD) | 1.0 × 1010 | >5.0 × 108 | [76,81] | ||

| Furfur alcohol (FFA) | 1.2 × 108 | [80,82] | |||

| Superoxide dismutase (SOD) | 2.4 × 109 | [84] | |||

| β-carotene | 9.2 × 108 | [85] | |||

| L-histidine (L-His) | 3.2 × 107 | [86] | |||

| Nitrobenzene (NB) | (3.2–4.7) × 109 | [87] | |||

| Para-chlorobenzoic acid (pCBA) | 5 × 109 | [73,79] | |||

| Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) | 7.0 × 109 | [82] | |||

| Carbamazepine (CBZ) | 8.8 × 109 | [15] | |||

| Sodium azide (NaN3) | 1.2 × 108 | [88] | |||

| Naproxen (NAP) | 9.0 × 109 | 9.0 × 109 | [89] | ||

| Benzoic acid (BA) | 5.9 × 109 | [90] |

Chemical probe experiments, when carefully selected and properly interpreted, provide a powerful approach to elucidate the formation, type, and relative contribution of reactive species in PAA-based AOPs.

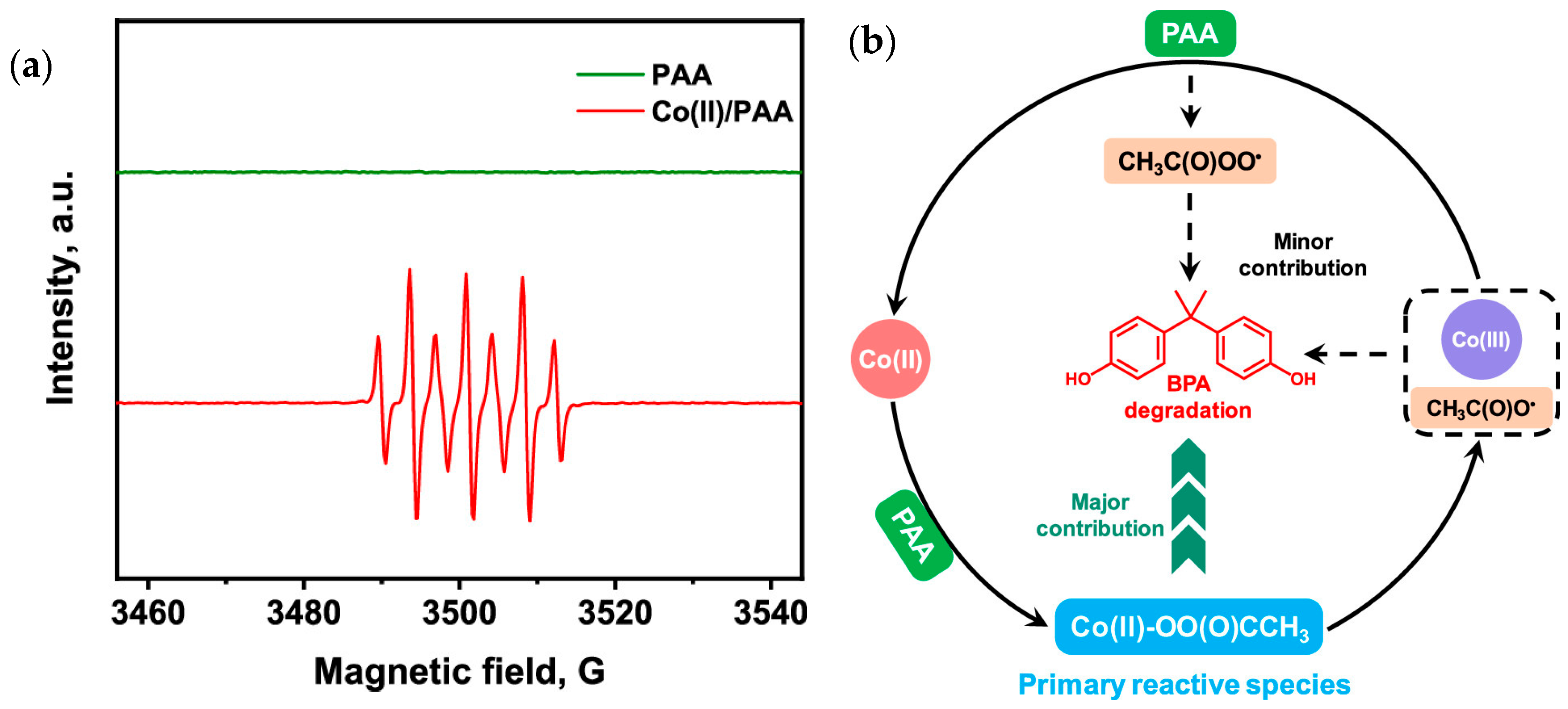

6.2. Electron Paramagnetic Resonance

EPR, also known as electron spin resonance (ESR), is a powerful technique for identifying the generation of reactive species through their characteristic spectra [91]. EPR/ESR is often integrated with spin-trapping reagents. Spin-trapping agents are commonly used to convert short-lived radicals into more stable spin adducts, which can be visualized through characteristic EPR signals. Common trapping agents include 2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-1-piperidinyloxy (TEMPO), 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine (TMP), 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-N-oxide (TEMP), and 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO). TEMPO can be used as a spin trapping reagent for detecting 1O2, where its oxidation leads to the appearance of the TEMPO-1O2 signal (intensity ratio of 1:1:1) [62]. Likewise, when DMPO is employed as the trapping agent, the formation of the DMPO-OH adduct, identified by its distinctive 1:2:2:1 intensity ratio, provides evidence for the possible presence of •OH [58].

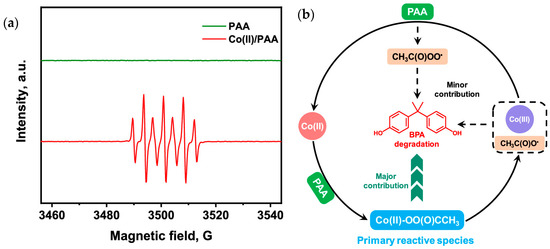

However, recent studies have demonstrated that EPR interpretation in PAA-based systems requires particular caution, especially in the presence of transition-metal catalysts. As illustrated by the EPR spectra obtained in the Co(II)/PAA system (Figure 6a), the dominant signal detected using DMPO is often attributed to DMPOX rather than to classical radical adducts such as DMPO–OH. The formation of DMPOX can result from the direct oxidation of DMPO by nonradical oxidants, including metal–peroxo complexes or high-valent metal (HMV) species, and therefore does not constitute unambiguous proof of free-radical pathways [92]. This observation highlights that EPR-active signals may reflect oxidative processes mediated by metal-centered species rather than the presence of freely diffusing radicals in solution.

Figure 6.

(a) Set of EPR peaks with strong signals belonging to DMPOX (experimental conditions: [DMPO]0 = 100 mM, and initial pH = 7.0) and (b) possible mechanism in the Co(II)/PAA process. Reproduced from [92].

In this context, HMVs such as Co(IV) and Fe(IV), which are key intermediates generated during PAA activation by MOFs-based catalysts, add an additional layer of complexity to EPR interpretation. HMV species can produce DMPO-OH adduct signals through the Forrester-Hepburn mechanism, in which the HVM abstracts a hydrogen atom from water or hydroxyl-containing molecules, forming a reactive species that reacts with DMPO. Consequently, the detection of DMPO-OH in EPR/ESR spectra may not exclusively indicate the presence of free •OH, but can also reflect oxidation mediated by HVMs species. The mechanistic framework proposed for Co(II)/PAA systems, schematically summarized in Figure 6b, further supports this view by identifying metal–PAA complexes as primary oxidants, with radical species acting only as secondary contributors [92].

Beyond their analytical implications, HMV–oxo species are increasingly recognized as highly effective oxidants in PAA-based advanced oxidation processes. These species are typically generated via multielectron transfer pathways between PAA and transition-metal centers, which are favored by the well-defined coordination environments and confinement effects provided by MOF structures. Unlike freely diffusing radicals, HMVs predominantly oxidize contaminants through direct electron transfer or oxygen atom transfer mechanisms occurring at or near the catalyst surface. As a result, they exhibit higher selectivity toward electron-rich organic pollutants and a markedly improved resistance to interference from common water matrix constituents, such as bicarbonate, chloride, and natural organic matter. This enhanced robustness explains why non-radical pathways often dominate in complex aqueous environments, where radical-based oxidation is readily quenched. Therefore, the presence of HMVs in MOF/PAA systems should not be regarded merely as a complication for EPR-based radical identification, but rather as evidence of an alternative and often more selective and stable oxidation pathway.

Thus, the generation and relative contribution of reactive species in PAA-based systems remain a topic of debate, primarily due to the limitations of the quenching experiments and characterization techniques. The interpretation of these studies is often complicated by several confounding factors. For example, quenchers can accelerate the decomposition of PAA, interfere with the adsorption or surface properties of the catalyst, or react with non-target species. These unintended interactions can distort observed reaction rates and product distributions, leading to ambiguous or even misleading conclusions regarding which reactive species are truly responsible for pollutant degradation. Therefore, a careful combination of selective scavengers, chemical probes, and complementary analytical methods is essential to accurately elucidate the roles of radical and nonradical pathways.

7. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

MOFs have played a transformative role in the field of AOPs due to their exceptionally high surface area, ordered porous architectures, and tunable chemical compositions. These inherent advantages have positioned pristine MOFs, MOF-based composites, and MOF-derived materials as highly promising catalysts for activating PAA. This review has systematically summarized recent advances in the design and application of MOF-related catalysts for efficient PAA activation, highlighting their structural, catalytic performance, and pollutant degradation efficiencies. Particular attention has been devoted to the identification and quantification of reactive species involved in PAA-based systems, providing critical mechanistic insights into both radical and non-radical oxidation pathways. However, despite the promising advancements made in MOF-based catalysts for PAA activation in recent years, several critical challenges remain and must be addressed to fully realize their effectiveness and practical applicability.

- Owing to the inherent unpredictability of the reaction, radical and non-radical pathways often occur concurrently, each with distinct advantages: radicals provide higher mineralization efficiency, whereas non-radicals offer greater resistance to interference. The design of MOF-based catalysts should carefully balance and regulate the interplay between these pathways. In particular, the mechanisms underlying non-radical pathways remain poorly understood and warrant further comprehensive study.

- Attention to safety and scalability is crucial for MOFs. Environmental toxicity from metal centers, linkers, and synthesis solvents, along with complex and costly fabrication procedures, limit their industrial application. Developing green, cost-effective, and simplified synthesis strategies is therefore essential to enable practical deployment of MOF-based catalysts.

- Ensuring catalyst stability is critical, yet many MOFs exhibit poor water stability and are prone to decomposition under highly oxidative conditions, which restrict their practical application. Future research should therefore prioritize the development of robust strategies, including the design of inherently stable MOFs and surface-modified MOFs.

- The real-world performance of MOF-based catalysts should be rigorously evaluated. Laboratory studies often employ model pollutants at relatively high concentrations, whereas actual wastewater contains CECs at ng/L to μg/L levels, often as complex mixtures. Catalytic tests under realistic conditions are necessary to validate the efficiency and robustness of MOFs in practical wastewater treatment.

- Developing and applying parameter optimization strategies, including analytical approaches for three-dimensional and multidimensional factors, is essential for enhancing the performance of MOF-based catalysts in PAA activation.

- Efforts should focus on combining MOF-based catalysts for PAA activation with complementary technologies, including electrochemical systems and biological treatments, to enhance overall treatment efficiency.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.B. and M.Á.S.; resources, M.Á.S.; writing—original draft preparation, B.B.; writing—review and editing, M.Á.S. and E.R.; visualization, B.B., E.R. and M.Á.S.; supervision, E.R. and M.Á.S.; project administration, M.Á.S.; funding acquisition, M.Á.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has been supported by project ED431C 2025/47 funded by Xunta de Galicia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this work, the authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI, GPT-5 model) to improve the clarity and readability of the manuscript. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed, and they take full responsibility for the content of the published article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bouzayani, B.; Elaoud, S.C.; Sanromán, M.Á. Current Progress in Advanced Oxidation Processes for the Removal of Contaminants of Emerging Concern Using Peracetic Acid as an Effective Oxidant. Catalysts 2025, 15, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa-Sanchez, S.; Peñuela, G.A. Peracetic Acid-Based Advanced Oxidation Processes for the Degradation of Emerging Pollutants: A Critical Review. J. Water Process Eng. 2022, 49, 102986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, J.; Chu, Y.; Qian, M.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, W. Unusually Improved Peracetic Acid Activation for Ultrafast Organic Compound Removal through Redox-Inert Mg Incorporation into Active Co3O4. Appl. Catal. B Environ. Energy 2025, 361, 124601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciscenko, I.; Vione, D.; Minella, M. Infancy of Peracetic Acid Activation by Iron, a New Fenton-Based Process: A Review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shariatmadari, S. Water Disinfection and Wastewater Treatment in Poultry Slaughterhouses Using Peracetic Acid (PAA): Its Effectiveness in Reducing Residual Microorganisms on Chicken Carcasses. Chem. Res. Technol. 2025, 2, 128–139. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, L.; Li, K.; Lv, Y.; Ye, M. Activation of Peracetic Acid by Bimetallic Metal-Organic Frameworks for Bezafibrate Degradation: Removal Efficiency, Mechanism and Influencing Factors. J. Water Process Eng. 2025, 69, 106862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Liu, B.; Huang, X.; Ma, Y.; Wang, H. Insight into Three-Dimensional Electro-Fenton System with Fe0 Activated Peroxyacetic Acid for Sulfadiazine Degradation under Neutral Condition: Performance and Degradation Pathways. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 505, 158968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; He, Y.; Hua, Z.; Xie, Z.; He, C.-S.; Xiong, Z.; Du, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xing, G.; Fang, J.; et al. PH-Dependent Bisphenol A Transformation and Iodine Disinfection Byproduct Generation by Peracetic Acid: Kinetic and Mechanistic Explorations. Water Res. 2023, 246, 120695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Yu, S.; Dong, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhou, P.; Zhang, H.; Xiong, Z.; He, C.-S.; Lai, B. Whether Peracetic Acid-Based Oxidation Process Is an Alternative to the Traditional Fenton Process in Organic Pollutants Degradation and Actual Wastewater Treatment? J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 490, 137752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Li, Y.; Dong, H.; Pang, Z.; Zhao, M.; Huang, D.; Dong, J.; Li, L. Highly Efficient Activation of Peracetic Acid via Zero-Valent Iron-Copper Bimetallic Nanoparticles (NZVIC) for the Oxidation of Sulfamethazine in Aqueous Solution under Neutral Condition. Appl. Catal. B 2024, 340, 123183. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Zhang, T.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, D. Preparation of Peracetic Acid from Hydrogen Peroxide: Part I: Kinetics for Peracetic Acid Synthesis and Hydrolysis. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2007, 271, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luukkonen, T.; Pehkonen, S.O. Peracids in Water Treatment: A Critical Review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 47, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitis, M. Disinfection of Wastewater with Peracetic Acid: A Review. Environ. Int. 2004, 30, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Huang, C.-H. Simultaneous Quantification of Peracetic Acid and Hydrogen Peroxide in Different Water Matrices Using HPLC-UV. Chemosphere 2020, 257, 127229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wan, Y.; Ding, J.; Wang, Z.; Ma, J.; Xie, P.; Wiesner, M.R. Thermal Activation of Peracetic Acid in Aquatic Solution: The Mechanism and Application to Degrade Sulfamethoxazole. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 14635–14645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, V.F.; Malek, N.I.; Kailasa, S.K. Review on Metal–Organic Framework Classification, Synthetic Approaches, and Influencing Factors: Applications in Energy, Drug Delivery, and Wastewater Treatment. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 44507–44531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaghi, O.M.; Li, H. Hydrothermal Synthesis of a Metal-Organic Framework Containing Large Rectangular Channels. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 10401–10402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosupi, K.; Masukume, M.; Weng, G.; Musyoka, N.M.; Langmi, H.W. Recent Advances in Fe-Based Metal-Organic Frameworks: Structural Features, Synthetic Strategies and Applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2025, 529, 216467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsehli, B.R. Toward Sustainable Environmental Cleanup: Metal–Organic Frameworks in Adsorption—A Review. Desalin. Water Treat. 2023, 316, 44–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Yang, Y.; Rushlow, J.; Huo, J.; Liu, Z.; Hsu, Y.-C.; Yin, R.; Wang, M.; Liang, R.; Wang, K.-Y.; et al. Development of the Design and Synthesis of Metal–Organic Frameworks (MOFs)—From Large Scale Attempts, Functional Oriented Modifications, to Artificial Intelligence (AI) Predictions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2025, 54, 367–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Wang, Z.; Zeng, L.; Feng, G. Identifying MOFs for Electrochemical Energy Storage via Density Functional Theory and Machine Learning. NPJ Comput. Mater. 2025, 11, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, J.K.; Rostami, S.; Rajesh, J.; Princess, R.M.B.; Govindaraju, R.; Kim, J.; Adelung, R.; Rajkumar, P.; Abdollahifar, M. ZnMn2O4 Applications in Batteries and Supercapacitors: A Comprehensive Review. J. Mater. Chem. A Mater. 2025, 13, 14540–14579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, N.; Shah, S.S.A.; Lin, Z.; Zheng, Y.-Z.; Jiao, L.; Jiang, H.-L. MOF-Based Electrocatalysts: An Overview from the Perspective of Structural Design. Chem. Rev. 2025, 125, 2703–2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; VanNatta, P.E.; Ren, J.; Ma, S. Metal–Organic Frameworks Housing Active Molecules as Bioinspired Catalysts. CCS Chem. 2024, 6, 1380–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasudhevan, P.; Manikandan, V.; Iqbal, N.; Ullah, S.; Ma, H.; Singh, S.; Varshney, D.; Pu, S. Metal-Organic Frameworks for Wastewater Remediation: Sustainable Synthesis, Properties, and Applications. Chem. Rec. 2025, 25, e202500076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Sun, Y.-G.; Ma, Y.-L. Highly Stable Mn-Doped Metal–Organic Framework Fenton-like Catalyst for the Removal of Wastewater Organic Pollutants at All Light Levels. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 2949–2955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Férey, G.; Mellot-Draznieks, C.; Serre, C.; Millange, F.; Dutour, J.; Surblé, S.; Margiolaki, I. A Chromium Terephthalate-Based Solid with Unusually Large Pore Volumes and Surface Area. Science 2005, 309, 2040–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, T.; Zhang, X.; Wang, S.; Niu, H.; Cai, Y. Spatial Confinement of a Co3O4 Catalyst in Hollow Metal–Organic Frameworks as a Nanoreactor for Improved Degradation of Organic Pollutants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 2350–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, J.; Chen, L.; Ji, H.; Li, P.; Li, F.; Liu, W. Activation of Peracetic Acid by Metal-Organic Frameworks (ZIF-67) for Efficient Degradation of Sulfachloropyridazine. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2022, 33, 3172–3176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.S.; Shahid, M. Synthesis of Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs): Routes to Various MOF Topologies, Morphologies, and Composites. In Electrochemical Applications of Metal-Organic Frameworks; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 17–35. [Google Scholar]

- Kamal, S.; Khalid, M.; Khan, M.S.; Shahid, M.; Ahmad, M. A Zinc (II) MOF for Recognition of Nitroaromatic Explosive and Cr (III) Ion. J. Solid State Chem. 2022, 315, 123482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, S.; Khalid, M.; Khan, M.S.; Shahid, M.; Ahmad, M. Amine-and Imine-Functionalized Mn-Based MOF as an Unusual Turn-on and Turn-off Sensor for D10 Heavy Metal Ions and an Efficient Adsorbent to Capture Iodine. Cryst. Growth Des. 2022, 22, 3277–3294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furukawa, H.; Cordova, K.E.; O’Keeffe, M.; Yaghi, O.M. The Chemistry and Applications of Metal-Organic Frameworks. Science 2013, 341, 1230444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosi, N.L.; Kim, J.; Eddaoudi, M.; Chen, B.; O’Keeffe, M.; Yaghi, O.M. Rod Packings and Metal− Organic Frameworks Constructed from Rod-Shaped Secondary Building Units. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 1504–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaghi, O.M.; Li, G.; Li, H. Selective Binding and Removal of Guests in a Microporous Metal–Organic Framework. Nature 1995, 378, 703–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Eddaoudi, M.; O’Keeffe, M.; Yaghi, O.M. Design and Synthesis of an Exceptionally Stable and Highly Porous Metal-Organic Framework. Nature 1999, 402, 276–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millange, F.; Walton, R.I. MIL-53 and Its Isoreticular Analogues: A Review of the Chemistry and Structure of a Prototypical Flexible Metal-organic Framework. Isr. J. Chem. 2018, 58, 1019–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, D.; Nakagawa, K.; Higuchi, M.; Horike, S.; Kubota, Y.; Kobayashi, T.C.; Takata, M.; Kitagawa, S. Kinetic Gate-Opening Process in a Flexible Porous Coordination Polymer. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 3914–3918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, K.S.; Ni, Z.; Côté, A.P.; Choi, J.Y.; Huang, R.; Uribe-Romo, F.J.; Chae, H.K.; O’Keeffe, M.; Yaghi, O.M. Exceptional Chemical and Thermal Stability of Zeolitic Imidazolate Frameworks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 10186–10191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavka, J.H.; Jakobsen, S.; Olsbye, U.; Guillou, N.; Lamberti, C.; Bordiga, S.; Lillerud, K.P. A New Zirconium Inorganic Building Brick Forming Metal Organic Frameworks with Exceptional Stability. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 13850–13851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ChemTube3D. Available online: https://www.chemtube3d.com/ (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Rubio-Martinez, M.; Avci-Camur, C.; Thornton, A.W.; Imaz, I.; Maspoch, D.; Hill, M.R. New Synthetic Routes towards MOF Production at Scale. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 3453–3480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahreni, M.; Ristianingsih, Y. A Review on Metal-Organic Framework (MOF): Synthesis and Solid Catalyst Applications. In Proceeding of LPPM UPN “Veteran” Yogyakarta Conference Series 2020–Engineering and Science Series; RSF Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; Volume 1, pp. 638–645. [Google Scholar]

- Rahaman, S.K.K.; Chatterjee, T.; Alam, S.M. Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of Metal–Organic Frameworks. In Synthesis of Metal-Organic Frameworks via Water-Based Routes; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 51–72. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, H.; Wei, T. Electrochemical Synthesis Methods of Metal-organic Frameworks and Their Environmental Analysis Applications: A Review. ChemElectroChem 2022, 9, e202200196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczęśniak, B.; Borysiuk, S.; Choma, J.; Jaroniec, M. Mechanochemical Synthesis of Highly Porous Materials. Mater. Horiz. 2020, 7, 1457–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaitsis, C.; Sourkouni, G.; Argirusis, C. Sonochemical Synthesis of MOFs. In Metal-Organic Frameworks for Biomedical Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 223–244. [Google Scholar]

- Fdez-Sanromán, A.; Rosales, E.; Pazos, M.; Sanroman, A. Metal–Organic Frameworks as Powerful Heterogeneous Catalysts in Advanced Oxidation Processes for Wastewater Treatment. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Sun, S.; Xie, Z.; Dong, Y.; Zhou, P.; Zhang, J.; Xiong, Z.; He, C.-S.; Mu, Y.; Lai, B. Comprehensive Insight into the Common Organic Radicals in Advanced Oxidation Processes for Water Decontamination. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 19571–19583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Wang, Z.; Song, Z.; Liu, X.; Tang, S.; Ren, N.; Ma, X.; Chen, Y. Mechanistic Insights into the Efficient Activation of Peracetic Acid by ZIF-67 for Bisphenol A Degradation. Surf. Interfaces 2024, 44, 103808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, R.; Li, Z.; Zhang, T.-Y.; Fu, Q.; Zheng, Z.-X.; Shi, J.; Lu, J.; Hu, C.-Y.; Tang, Y.-L.; El-Din, M.G.; et al. Amino-Functionalized MIL-101 (Fe)-NH2 as Efficient Peracetic Acid Activator for Selective Contaminant Degradation: Unraveling the Role of Electron-Donating Ligands in Fe (IV) Generation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 491, 138028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, K.; Song, T.; Wang, D.; Zou, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Tang, Z.; Hu, W. Bimetal–Organic Frameworks for Functionality Optimization: MnFe-MOF-74 as a Stable and Efficient Catalyst for the Epoxidation of Alkenes with H2O2. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 1591–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Yazeed, W.S.A.; Abou El-Reash, Y.G.; Elatwy, L.A.; Ahmed, A.I. Novel Bimetallic Ag-Fe MOF for Exceptional Cd and Cu Removal and 3,4-Dihydropyrimidinone Synthesis. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2020, 114, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, N.; Kumar, T.; Singh, V.; Kim, K.-H. Recent Advances in Bimetallic Metal-Organic Framework as a Potential Candidate for Supercapacitor Electrode Material. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 430, 213660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Fu, J.; Hua, B.; Wu, Y.; Gu, Y.; Qin, N.; Li, F. Hierarchical Porous Bimetallic FeMn Metal–Organic Framework Gel for Efficient Activation of Peracetic Acid in Antibiotic Degradation. ACS Environ. Au 2023, 4, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, R.; Zhang, L.; Fu, Y. Bimetallic Metal-Organic Framework as a High-Performance Peracetic Acid Activator for Sulfamethoxazole Degradation. Chemosphere 2024, 349, 140958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Zhou, C.; Lv, X.; Du, S.; Sui, M. Sustainable Co (III)/Co (II) Cycles Triggered by Co-Zn Bimetallic MOF Encapsulating Fe Nanoparticles for High-Efficiency Peracetic Acid Activation to Degrade Sulfamethoxazole: Enhanced Performance and Synergistic Mechanism. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 354, 128729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.-B.; Chen, C.-W.; Chen, W.-H.; Chen, L.; Hsieh, S.; Dong, C.-D. Kumquat Peel-Derived Biochar to Support Zeolitic Imidazole Framework-67 (ZIF-67) for Enhancing Peracetic Acid Activation to Remove Acetaminophen from Aqueous Solution. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 350, 123970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subudhi, S.; Swain, G.; Tripathy, S.P.; Parida, K. UiO-66-NH2 Metal–Organic Frameworks with Embedded MoS2 Nanoflakes for Visible-Light-Mediated H2 and O2 Evolution. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 9824–9837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emam, H.E.; Ahmed, H.B.; Gomaa, E.; Helal, M.H.; Abdelhameed, R.M. Doping of Silver Vanadate and Silver Tungstate Nanoparticles for Enhancement the Photocatalytic Activity of MIL-125-NH2 in Dye Degradation. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2019, 383, 111986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wei, J.; Huo, J.; Ji, W.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Cui, N.; Yan, W.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Harnessing Electronically Core-Shell CoFe Alloy-Carbon from Prussian Blue Analogues for Efficient Pollutant Abatement via Peracetic Acid Activation: Dual Reactive Species Generation and Synergistic Mechanisms. Appl. Catal. B Environ. Energy 2025, 371, 125284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Jiang, B.; Zhu, T.; Sun, Z. Novel CoFe-Supported UiO-66-Derived ZrO2 for Rapid Activation of Peracetic Acid for Sulfamethoxazole Degradation. Environ. Res. 2025, 274, 121329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wu, Y.; Wan, S.; Wang, B.; Ji, H.; Xiang, X. Preparation of Co/Cu-Based Bi-MOFs and the Degradation of Sulfamethoxazole by Activated Peracetic Acid. Water Sci. Technol. 2023, 87, 1202–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, S.; Zhu, Q.-L.; Xu, Q. Nanomaterials Derived from Metal–Organic Frameworks. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2017, 3, 17075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, L.; Qiu, Y. Recent Advances in Energy Materials by Electrospinning. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 81, 1825–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Salunkhe, R.R.; Liu, J.; Torad, N.L.; Imura, M.; Furukawa, S.; Yamauchi, Y. Thermal Conversion of Core–Shell Metal–Organic Frameworks: A New Method for Selectively Functionalized Nanoporous Hybrid Carbon. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 1572–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Huang, X.; Wang, J.; Song, H.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, L.; Yu, C. Hollow Mesoporous Carbon Nanocubes: Rigid-Interface-Induced Outward Contraction of Metal-Organic Frameworks. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1705253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Tang, Y.; Xia, S.; Zeng, H.; Shi, Z.; Deng, L. Efficient Degradation of Tetracycline via Peracetic Acid Activation Using Fe2SiO4: Performance and Mechanisms Study. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 393, 127304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Yu, H.; Han, Z.; Xu, S.; Dong, Z.; Zhou, K.; Zhang, S.; Cheng, Z. Remediation of Atrazine in Environment by Persulfate Activation via N/B Co-Doped Si-Rich Biochar: Performance, Mechanisms, Degradation Pathways and Phytotoxicity. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 477, 147131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, T.; Wang, P. Screening for the Adsorption-Activated H2O2 and Peroxymonosulfate for High-Performance Heteroatom-Doped Graphene: Molecular Dynamics Simulation and DFT. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2024, 952, 117890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.; Zhang, L.; Cheng, Z.; Peng, Y.; Tang, J.; Zhu, H.; Qiu, F. Enhanced Remediation of Actual Dye Wastewater by Hydrogenated Bimetallic MOF Derivative with Active Peracetic Acid. npj Clean Water 2025, 8, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Fu, Y.; Zhou, R.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, L.; Deng, J.; Liu, Y. Efficient Degradation of Organic Contaminants by Magnetic Cobalt Ferrite Combined with Peracetic Acid. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2022, 160, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Chen, Y.; Li, R.; Gao, J.; Pan, S. Insight into the Activation of Peracetic Acid by Cobalt-Nitrogen-Doped Porous Carbon for Efficient Norfloxacin Degradation: Performance and Mechanism. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 338, 126572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Du, P.; Liu, W.; Luo, C.; Zhao, H.; Huang, C.-H. Cobalt/Peracetic Acid: Advanced Oxidation of Aromatic Organic Compounds by Acetylperoxyl Radicals. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 5268–5278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Tian, D.; Liu, T.; Chen, J.; Huang, T.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, Y. Degradation of Organic Compounds by Peracetic Acid Activated with Co3O4: A Novel Advanced Oxidation Process and Organic Radical Contribution. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 394, 124938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, K.; Lichtfouse, E.; Li, C.; Zhang, Y. Fe-Biochar as a Safe and Efficient Catalyst to Activate Peracetic Acid for the Removal of the Acid Orange Dye from Water. Chemosphere 2022, 307, 135686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Kamali, M.; Kakavandi, B.; Costa, M.E.V.; Thompson, I.P.; Huang, W.; Appels, L.; Dewil, R. Activation of Peracetic Acid by a Magnetic Biochar-Ferrospinel AFe2O4 (A = Cu, Co, or Mn) Nanocomposite for the Degradation of Carbamazepine—A Comparative and Mechanistic Study. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 490, 151932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, P.; Hou, K.; Chen, F.; Pi, Z.; He, L.; Chen, S.; Li, X.; Yang, Q. Ultra-Rapid and Long-Lasting Activation of Peracetic Acid by Cu-Co Spinel Oxides for Eliminating Organic Contamination: Role of Radical and Non-Radical Catalytic Oxidation. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 463, 142344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Liu, Z.; Sun, Z. Co-Fe Bimetallic Oxides Derived from Prussian Blue Analogs to Activate Peracetic Acid for Eliminating Sulfamethazine: Contribution and Identification of Radical Species. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 60, 105121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, T.; Ping, Q.; Zhang, A.; Wang, L.; Dou, Y.; Li, Y. Enhanced Removal of Oxytetracycline by UV-Driven Advanced Oxidation with Peracetic Acid: Insight into the Degradation Intermediates and N-Nitrosodimethylamine Formation Potential. Chemosphere 2021, 274, 129726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zheng, T.; Zhou, X. Highly Efficient Activation of Peracetic Acid by Nano-CuO for Carbamazepine Degradation in Wastewater: The Significant Role of H2O2 and Evidence of Acetylperoxy Radical Contribution. Water Res. 2022, 216, 118322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J.; Cao, L.; Chen, Z.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Z.; Xie, P.; Ma, J. New Insights into the Degradation of Micro-Pollutants in the Hydroxylamine Enhanced Fe (II)/Peracetic Acid Process: Contribution of Reactive Species and Effects of PH. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 441, 129885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yang, Y.; Zheng, H.; Zheng, Y.; He, C.-S.; Lai, B.; Ma, J.; Nan, J. Introduction of Oxygen Vacancy to Manganese Ferrite by Co Substitution for Enhanced Peracetic Acid Activation and 1O2 Dominated Tetracycline Hydrochloride Degradation under Microwave Irradiation. Water Res. 2022, 225, 119176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.; Li, Z.; Cheng, P.; She, Y.; Wang, W.; Tian, Y.; Ma, J.; Sun, Z. Efficient Activation of Peracetic Acid by Mixed Sludge Derived Biochar: Critical Role of Persistent Free Radicals. Water Res. 2022, 223, 119013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Guo, W.; Jia, W.; Wang, H.; Si, Q.; Zhao, Q.; Luo, H.; Jiang, J.; Ren, N. Novel Nonradical Oxidation of Sulfonamide Antibiotics with Co (II)-Doped g-C3N4-Activated Peracetic Acid: Role of High-Valent Cobalt–Oxo Species. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 12640–12651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Duan, Y.; Dai, C.; Li, S.; Chen, Y.; Tu, Y.; Leong, K.H.; Zhou, L. Oxidation of Sulfamethazine by Peracetic Acid Activated with Biochar: Reactive Oxygen Species Contribution and Toxicity Change. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 313, 120170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Cao, L.; Xie, P.; Ma, J. Molybdenum Disulfide (MoS2) Promoted Sulfamethoxazole Degradation in the Fe (III)/Peracetic Acid Process. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 281, 119854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, Z.; Ji, R.; Zhou, X. Activation of Peracetic Acid with Cobalt Anchored on 2D Sandwich-like MXenes (Co@ MXenes) for Organic Contaminant Degradation: High Efficiency and Contribution of Acetylperoxyl Radicals. Appl. Catal. B 2021, 297, 120475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Zhai, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhao, T.; Yuan, D.; Jiao, T.; Zhang, Q.; Tang, S. Peracetic Acid Activation by Natural Chalcopyrite for Metronidazole Degradation: Unveiling the Effects of Cu-Fe Bimetallic Sites and Sulfur Species. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 305, 122500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Dong, H.; Li, Y.; Li, L.; Chu, D.; Xiang, S.; Hou, X.; Dong, Q.; Xiao, S.; Jin, Z.; et al. Graphene Shell-Encapsulated Copper-Based Nanoparticles (G@ Cu-NPs) Effectively Activate Peracetic Acid for Elimination of Sulfamethazine in Water under Neutral Condition. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 441, 129895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Duan, J.; Du, P.; Sun, W.; Lai, B.; Liu, W. Accurate Identification of Radicals by In-Situ Electron Paramagnetic Resonance in Ultraviolet-Based Homogenous Advanced Oxidation Processes. Water Res. 2022, 221, 118747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Li, X.; Li, H.; Qian, J.; Pan, B. New Insights into the Activation of Peracetic Acid by Co (II): Role of Co (II)-Peracetic Acid Complex as the Dominant Intermediate Oxidant. ACS EST Eng. 2021, 1, 1432–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.