Abstract

Rett syndrome (RTT) is a rare neurodevelopmental disorder that causes severe motor and cognitive impairments, limiting voluntary communication. Gaze-based technologies and virtual reality (VR) offer innovative ways to assess and enhance attention, happiness, and learning in individuals with minimal motor control. This study investigated and compared visual-attentional and emotional engagement in girls with RTT and typically developing (TD) peers during exploration of a virtual forest presented in 2D and immersive 3D (VR) formats across four progressively complex tasks. Twelve girls with RTT and 12 TD peers completed eye-tracking tasks measuring reaction time, fixation duration, disengagement events, and observed happiness. Girls with RTT showed slower responses and more disengagements overall, but VR significantly improved attentional efficiency in both groups, resulting in faster reaction times (η2p = 0.36), longer fixations (η2p = 0.31), and fewer disengagements (η2p = 0.27). These effects were stronger in the RTT group. Both groups also showed greater happiness in VR settings (RTT: p = 0.011; TD: p = 0.015), and in participants with RTT, peaks in attention coincided with peak happiness, indicating a link between happiness and cognitive engagement. Immersive VR thus appears to enhance attention and affect in RTT, supporting its integration into personalized neurorehabilitation.

1. Introduction

1.1. Rett Syndrome: Clinical Features and Cognitive-Motor Limitations

Rett Syndrome (RTT) is a rare and severe neurodevelopmental disorder that predominantly affects females [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. In most cases, RTT is caused by mutations in the MECP2 gene [9,10,11], which plays a critical role in the epigenetic regulation of neuronal development. The disorder is typically characterized by an initial phase of apparently normal development, followed by a profound regression of motor and cognitive skills, often accompanied by hallmark symptoms such as loss of purposeful hand movements, repetitive hand-wringing stereotypies, breathing irregularities, and progressive social withdrawal [12,13,14,15,16].

The progressive decline in motor function greatly restricts purposeful actions, making communication and interaction with the environment particularly challenging [6]. Given these limitations, gaze often represents the most reliable channel of communication for individuals with RTT. Eye-tracking technology (ETT) has therefore become a key component of Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) systems, enabling individuals to express preferences, make choices, and engage in cognitive activities through gaze-based interfaces [6,17,18]. Beyond its communicative function, ETT has proven valuable for assessing visual and cognitive abilities, training attentional control, and supporting decision-making processes [19,20]. Evidence from previous studies indicates that gaze-based interventions can enhance sustained attention, reduce stereotypical behaviors, and promote social participation, thereby improving the overall quality of life of patients and their families [21,22,23,24,25].

1.2. Rehabilitation Approaches and Technology Integration

Although no definitive cure for RTT currently exists, targeted rehabilitation programs can foster the development of motor and cognitive skills, reduce stereotyped behaviors, and improve daily participation [26,27]. Previous research suggests that rehabilitation programs characterized by high frequency and low intensity are particularly effective in enhancing performance across motor and cognitive domains. Moreover, early and individualized interventions, supported by active involvement of families and caregivers, are essential to maximize each patient’s potential [28].

In recent years, the integration of traditional rehabilitation with advanced technologies has been shown to increase treatment efficacy in individuals with neurodevelopmental disorders [29,30,31]. Among technologies in neurorehabilitation, virtual reality (VR) has shown promise as a tool for enhancing motor, cognitive, and emotional outcomes. VR enables the creation of immersive, controlled, and customizable environments that can facilitate motor and cognitive learning, increase happiness, and promote multisensory engagement [32,33]. Wankhede et al. [34] highlight VR’s capacity to enhance neuroplasticity, improve motor recovery and cognitive function, and foster emotional resilience across various neurological conditions, while also emphasizing the potential for personalized interventions and the importance of addressing ethical and practical considerations. Recent studies highlight the growing application of virtual reality (VR) in neurodevelopmental rehabilitation. For example, Capobianco et al. [35] reviewed VR-based interventions for children and adolescents with neurodevelopmental disorders, showing improvements in cognitive, motor, and emotional outcomes. Tang et al. [36] proposed an innovative interactive narrative persona (INP) approach for VR-based dementia rehabilitation, emphasizing the potential of immersive environments to enhance engagement and motivation. Moreover, a recent systematic review by Bailey, Bryant, and Hemsley [37] synthesized evidence on VR and augmented reality for individuals with communication disabilities and neurodevelopmental disorders across the lifespan.

Despite these advances, no previous controlled study has combined immersive VR with eye-tracking to assess visual–attentional and emotional engagement in girls with Rett Syndrome (RTT). This gap underscores the novelty of our work and the importance of evaluating whether immersive VR can enhance attention, motivation, and affective responsiveness beyond what is observed in conventional 2D settings.

1.3. Evidence for VR and Eye-Tracking in Cognitive Engagement

Evidence from neurological populations supports the effectiveness of VR in improving cognitive processes such as attention, memory, logical sequencing, and problem-solving, as well as promoting emotional involvement and social interaction [38,39,40]. Preliminary findings in RTT populations suggest that VR can increase attentional engagement, reduce stereotypical behaviors, and improve fine and gross motor abilities, particularly when integrated with motion sensors or treadmill systems to create more personalized and immersive experiences [26,27,41,42]. Eye-tracking metrics such as fixation duration and gaze dispersion provide quantitative indicators of attentional focus, cognitive load, and emotional engagement [43,44]. In virtual environments, indices such as fixation duration and disengagement have been shown to correlate with both task performance and affective involvement, making them valid measures of cognitive engagement even in populations with limited motor output [45,46]. Naturalistic immersive scenarios, such as interactive forest environments, may be especially effective in fostering curiosity, emotional well-being, and attentional engagement compared to traditional two-dimensional contexts [47].

1.4. Research Gap, High-Level Research Question, and Hypotheses

Despite preliminary evidence suggesting the potential of immersive VR and gaze-based interfaces in enhancing attentional and emotional engagement in neurodevelopmental disorders [32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41], studies in RTT remain scarce, often limited by small sample sizes, low ecological validity, and lack of systematic assessment of attentional and emotional responses.

Research question: Can immersive VR environments enhance attentional engagement, cognitive performance, and emotional responsiveness in girls with RTT beyond what is observed in standard 2D settings, and how do these effects interact with task complexity?

To address this question, we formulated a set of hypotheses, separated into core and supportive categories for clarity:

- Core hypotheses (novel contributions):

- Modality effect (2D vs. VR): Both RTT and TD participants will show higher levels of attentional engagement and faster visual exploration in the VR condition compared to the 2D condition, due to greater immersiveness and ecological validity of VR environments [32,33,34,38,39,40,41].

- Modality × Group interaction: The enhancement induced by VR is expected to be stronger in RTT participants, reflecting the potential of immersive environments to facilitate attention, happiness, and emotional involvement in individuals with severe motor and communicative limitations [32,33,34,38,39].

- Task complexity effect: Increasing task complexity will reduce attentional and cognitive performance in both groups, but VR may mitigate this decline, particularly in RTT participants, highlighting the interaction between modality and task demand.

- Happiness/emotional engagement: Emotional responsiveness, as measured by observed happiness, will be higher in VR than in 2D, with RTT participants showing the largest benefit, demonstrating that immersive VR can simultaneously enhance cognitive and affective engagement [35,36,38].

- Supportive/descriptive hypotheses:

- 5.

- Group differences: RTT participants are expected to show slower reaction times, shorter fixation durations, and more frequent attentional disengagement than TD peers across both modalities, consistent with the known cognitive and motor limitations associated with RTT [6,7,8,12,13,14,15,16]. Moreover, with reference to baseline happiness, no significant differences in baseline emotional engagement are expected between RTT and TD participants in 2D conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Twelve female patients with Rett Syndrome (RTT), aged 7 to 23 years (M = 13.1, SD = 6.04), were recruited through the Italian Rett Syndrome Association (AIRETT). The wide age range reflects the real-world variability among individuals with RTT and aligns with AIRETT’s inclusive recruitment policy, which encourages participation of all eligible families regardless of age or severity level.

Inclusion criteria were: (a) chronological age between 3 and 30 years; (b) confirmed genetic diagnosis of RTT with MECP2 mutations; (c) adequate postural control while seated; and (d) at least partial or consistent eye contact. Participants with pharmacoresistant epilepsy or severe uncorrected visual impairment were excluded. Despite variability in age, all participants met the diagnostic criteria for typical RTT and were deemed functionally capable of engaging with the proposed gaze-based VR tasks. According to Hagberg’s [48] classical staging, participants were classified as either stage III, characterized by pronounced hand apraxia/dyspraxia, apparently preserved ambulation, and residual communicative skills mainly expressed through eye gaze, or stage IV, indicating late motor deterioration with progressive loss of walking ability.

Disease severity in RTT participants was assessed using the Rett Assessment Rating Scale (RARS) [49]. The RARS is a standardized tool designed to evaluate the severity of clinical symptoms in RTT across multiple domains, including motor function, communication, and autonomic features. Scores are aggregated to provide a total severity score along a continuum from mild to severe. In the present study, RARS scores were normally distributed (skewness = 0.110, kurtosis = 0.352), and the scale demonstrated excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.912), with subscale alphas ranging from 0.811 to 0.934. This assessment allowed us to characterize the functional variability within the RTT group and to interpret their performance in the subsequent experimental tasks.

Functional abilities were assessed using the Global Assessment and Intervention in Rett Syndrome (GAIRS) [50]. The GAIRS checklist is a multidimensional assessment tool evaluating ten macro-areas: basic or prerequisite behaviors, neuropsychological abilities, basic and advanced cognitive concepts, communication skills, emotional–affective abilities, hand and graphomotor skills, global motor abilities, and daily autonomy. It includes 85 hierarchically structured skills scored from 1 (minimal ability) to 5 (maximal ability). For instance, in the “basic behavior” domain, spontaneous eye contact is rated from 1 (unable) to 5 (always establishes contact), while in the “hand motor” domain, grasping ability ranges from 1 (unable to grasp) to 5 (able to grasp a 1 cm object with a precise thumb–index grip). The GAIRS provides a global overview of patient functioning and guides individualized rehabilitation planning. Cronbach’s α for the full scale was 0.89, with subscale alphas ranging from 0.82 to 0.94.

The control group consisted of twelve typically developing (TD) female participants aged 2 to 4 years (M = 3.5, SD = 0.7), recruited from local preschools and matched to the RTT group for functional abilities as assessed by GAIRS checklist [50]. None of the TD participants had a history of neurological, psychiatric, or visual disorders. Although the chronological ages differ, the TD participants were selected to match the RTT group on functional abilities rather than age. Matching on GAIRS scores allows meaningful comparisons of task performance, as RTT participants exhibit severe intellectual and motor impairments that make age-based matching inappropriate. Given the profound dissociation between chronological age and developmental functioning that characterizes Rett syndrome, functional-level matching is considered methodologically more appropriate than chronological-age matching [51,52]. For this reason, participants were matched on functional abilities, assessed via the GAIRS checklist, rather than on age. This approach ensures comparability on the cognitive, motor, attention, and communicative skills directly relevant to the interaction task

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of all participants, including age, GAIRS score, genetic mutation, RARS score, and disease severity.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants.

An a priori power analysis was conducted using G*Power 3.1 to estimate the minimum sample size required for detecting medium-sized effects (Cohen’s f = 0.25) in a 2 × 2 × 4 mixed-design ANOVA (Group × Modality × Task), with α = 0.05, an estimated correlation among repeated measures of 0.5, and a non-sphericity correction factor (ε) of 1. The analysis indicated that approximately 34 participants would be required to achieve 80% power (1-β) for detecting main effects and interactions. Given the rarity of Rett Syndrome, recruiting large samples is inherently challenging. Consequently, the present study included 24 participants (12 RTT, 12 TD), which is below the optimal sample size for detecting smaller or complex interaction effects. While this limits statistical power, the study is sufficient for exploring large effects and provides important preliminary data in this underrepresented population. A post hoc power estimation for this actual sample size indicated sufficient power to detect large effects (partial η2 ≥ 0.14), particularly for the core outcome measures (Reaction Time, Fixation Duration, and Disengagement). Consequently, results for smaller or more complex interactions should be interpreted with caution and future research with larger samples is recommended to replicate and extend these findings. All participants’ parents or legal guardians provided written informed consent prior to data collection. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the local ethics committee of the University of Genua (protocol number 2023/97, date: 29 November 2023).

2.2. Instruments and Procedure

Prior to the experimental session, AIRETT therapists collected demographic and clinical data for all participants, including age, genetic mutation type, disease severity (for RTT participants only), assessed with the Rett Assessment Rating Scale (RARS) [44] and functional level evaluated using the Global Assessment and Intervention in Rett Syndrome (GAIRS) [50] checklist for both groups.

2.3. Materials

2.3.1. Computer with Eye-Tracking

Data were collected using a high-performance laptop equipped with a 17.3″ UHD display (3840 × 2160, 60 Hz, 25 ms, 500 nits, 100% Adobe RGB) and Tobii® eye-tracking technology (Tobii AB, Stockholm, Sweden).

The system featured an NVIDIA® GeForce® RTX 2070 SUPER™ 8 GB GDDR6 graphics card, a 10th Generation Intel® Core™ i9-10980HK processor (8 cores, 16 MB cache, up to 5.3 GHz with Turbo Boost 2.0), 32 GB DDR4 2666 MHz memory, and a 1 TB RAID0 (2 × 512 GB PCIe M.2 SSD) drive plus an additional 512 GB SSD.

The eye-tracking system recorded gaze position and fixation duration, defined as the moments when the gaze remained stably focused on an object of interest.

2.3.2. Forest Environment

A virtual game developed in Unity (unity.com; accessed on 15 December 2025) recreated a forest environment familiar to patients. The VR scenario included four progressively demanding gaze-contingent tasks designed to elicit increasing levels of cognitive engagement and attentional control (Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4):

Figure 1.

Exploration condition (low cognitive load). Participants freely explored the virtual forest; objects responded to gaze without predefined targets or sequence.

Figure 2.

Selective attention condition (moderate cognitive load). Participants were instructed to fixate on predefined targets in a specific order, requiring top–down attentional control.

Figure 3.

Relational fixation condition (high cognitive load). Participants fixated on the mother deer to bring her closer to the fawn, requiring sustained attention and relational processing.

Figure 4.

Visual tracking condition (very high cognitive load). Participants continuously tracked a moving target (e.g., the fox) to achieve the goal (approaching the food basket), requiring continuous attentional tracking.

Exploration (Low cognitive load)—Free exploration of the virtual forest. Objects reacted contingently to gaze (e.g., the deer approached, rabbits moved, flowers grew). This phase required basic visual attention and allowed familiarization with gaze-based interaction.

Selective Attention (Moderate cognitive load)—Participants were instructed to look at specific targets in a predefined order, requiring top–down attentional control and sequential processing.

Relational Fixation (High cognitive load)—Participants had to fixate on a mother deer to bring her closer to her fawn, engaging relational reasoning and sustained attention.

Visual Tracking (Very high cognitive load)—Participants had to look at a fox to make it get closer to a food basket, requiring continuous attentional tracking of a moving target and goal-directed processing. Each task was specifically designed to probe a distinct aspect of visual–attentional or cognitive engagement: the Exploration task assessed spontaneous visual attention, Selective Attention required voluntary top–down control, Relational Fixation measured sustained attention and relational reasoning, and Visual Tracking evaluated continuous attentional tracking under high cognitive load. These tasks directly map onto the study hypotheses regarding modality effects, group differences, and task complexity.

In both the VR and 2D conditions, participants’ gaze was continuously recorded using a Tobii® eye-tracking system. The system captured fixation duration, gaze position, and disengagement events for all tasks.

The same forest scenario was recreated in a two-dimensional (2D) version using Microsoft PowerPoint. To approximate the immersive experience of the VR condition (≈100° horizontal field of view), stimuli were presented on a 55″ UHD display (≈120 cm × 68 cm, 3840 × 2160 resolution) at a viewing distance of ≈60 cm, corresponding to a visual angle of ≈95°. The VR and 2D conditions were designed to be identical in terms of task structure, timing, and visual content. Both modalities employed the same animated flower, with the same appearance, motion dynamics, and interaction contingencies. Only the display modality differed (flat screen vs. VR headset). Although visual immersion unavoidably differs between 2D and VR, no assumption of full perceptual equivalence was made; instead, we controlled for stimulus identity and task events across conditions.

2.4. Procedure

Before the experiment, caregivers received a detailed explanation of the study’s objectives, procedures, and potential benefits and risks, and provided written informed consent.

Participants were first assessed using the GAIRS checklist, and caregivers of RTT participants completed the RARS. Experimental sessions were conducted at the AIRETT Centre, with all sessions recorded via a frontal camera.

Participants sat approximately 30 cm from the display, with the infrared eye-tracking system continuously monitoring gaze. The non-dominant limb was positioned under the table to minimize interference.

Each participant experienced both the 2D and VR conditions in counterbalanced order, with a minimum interval of four hours between exposures. Instructions were kept as consistent as possible across conditions. In both modalities, the experimenter provided the same simple directive (“Look at the flower and interact with it as you wish”). In the VR condition, an additional clarifying sentence (“You will see the same flower inside the headset”) was included to ensure orientation and comfort.

Two trained AIRETT therapists manually recorded the number of aids provided and the accuracy of participants’ responses during each session. Simultaneously, the eye-tracking system automatically captured quantitative measures, including reaction times, fixation duration, and disengagement events, while video recordings were later analyzed to compute the Happiness Index (MI) across conditions.

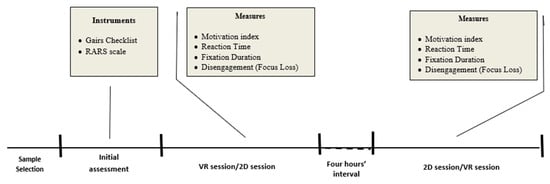

A diagram showing the procedure is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Diagram of the procedure.

2.5. Parameters

Happiness Index (MI): A composite behavioral indicator derived from Van der Maat [53] and Petry & Maes [54], based on five observable behaviors: gaze direction, sounds, mouth movements, physiological reactions, and hand gestures. Two independent blinded raters coded each behavior (1 = present, 0 = absent); inter-rater agreement = 96%.

Reaction Time (RT): The latency between stimulus onset and gaze or motor or ocular response, expressed in tenths of a second.

Fixation Duration: The time (in ms) the gaze remains stably focused on a specific object or area of interest (AOI), reflecting attentional engagement and cognitive processing [55].

Disengagement (Focus Loss): The number of interruptions during the task. A disengagement event was defined as a gaze shift away from the AOI lasting more than 500 ms without reorienting to the target. This parameter reflects attentional stability and the ability to maintain focus on goal-relevant stimuli. Higher disengagement frequency indicates reduced sustained attention or difficulties in maintaining task-related focus.

2.6. Data Preparation and Synchronization

Prior to analysis, eye-tracking and video data were carefully preprocessed to ensure accuracy and comparability across participants and conditions. Eye-tracking recordings were first calibrated for each participant using a standard 9-point procedure, and sessions with poor calibration (<90% accuracy) were excluded.

Blink events and other signal losses were automatically identified by the Tobii system and removed from the dataset. Fixations shorter than 80 ms were discarded as potential artifacts, while fixations longer than 2 standard deviations above the mean were visually inspected to confirm validity.

Video recordings were synchronized with eye-tracking data using time-stamped markers embedded in both streams. This allowed alignment of behavioral observations (used to compute the Happiness Index) with gaze-based measures (fixation duration, reaction time, and disengagement events).

Finally, all quantitative variables were exported to SPSS for statistical analysis, and quality checks ensured that each participant had complete data across all four tasks and both modalities (VR and 2D). Missing or corrupted data points (<5% of total) were handled via pairwise deletion during inferential analyses.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics 25. Preliminary screening included evaluation of outliers, missing values, and normality (Shapiro–Wilk test). Given the small sample size and heterogeneity of the RTT group, some variables violated normality assumptions; therefore, both parametric and non-parametric approaches were applied to ensure robustness and interpretability of results [56,57].

A 3-way mixed-design ANOVA was conducted for the eye-tracking measures, with the following factors: Group (between-subjects): RTT vs. TD, Modality (within-subjects): 2D vs. VR and Task (within-subjects): Exploration, Selective Attention, Relational Fixation, Visual Tracking

Dependent variables analyzed were Reaction Time (RT), Fixation Duration, and Disengagement (Focus Loss). Greenhouse–Geisser correction was applied where sphericity assumptions were violated. Effect sizes are reported as partial eta squared (η2p), with benchmarks of 0.01 (small), 0.06 (medium), and 0.14 (large) [58].

The Happiness Index (MI) was evaluated differently: it represented a global behavioral measure derived from video coding in the two modalities only (2D vs. VR), rather than task-specific data. Therefore, group differences in MI were analyzed using non-parametric Mann–Whitney U tests, and effect size was reported using rank-biserial correlation (r_rb) [59].

Descriptive statistics (means, SDs, medians, interquartile ranges) were reported for all variables to account for interindividual variability typical in RTT. Correlations between eye-tracking indices (fixation duration, disengagement) and behavioral measures (MI, RT) were explored using Spearman’s ρ to examine whether attentional engagement predicted motivational behavior or faster visual responses.

All tests were two-tailed with α = 0.05, and results were interpreted considering both statistical significance and effect size, following current recommendations for small-sample cognitive–neurodevelopmental research [60,61].

3. Results

Analyses were conducted to test the hypotheses concerning modality effects (2D vs. VR), group differences (RTT vs. TD), interactions, task complexity, and motivational engagement (Happiness Index). The integrated results are presented below.

3.1. Modality Effect (2D vs. VR)

Analyses were first conducted to test the main effect of modality, comparing 2D and VR conditions across both groups.

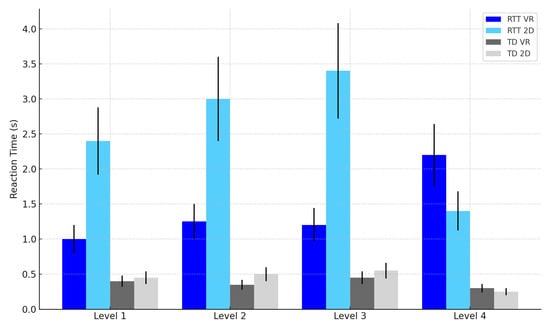

Reaction Time (RT): Mean RTs were significantly faster in the VR condition compared to the 2D condition, F(1, 22) = 12.12, p = 0.002, η2p = 0.36 (see Table 2 and Figure 6).

Table 2.

Reaction Time (seconds) by Modality and Task.

Figure 6.

Reaction time by task difficulty level, group, and modality. Note: Error bars represent standard errors of the mean (SEM).

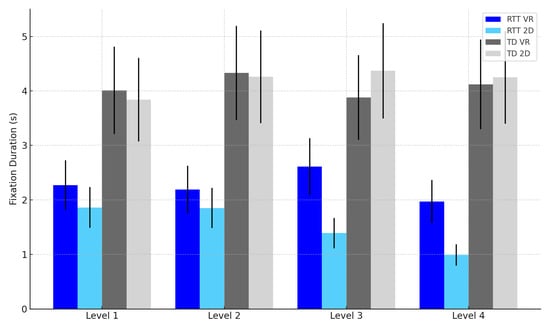

Fixation Duration (FD): Participants exhibited longer fixations in the VR condition, F(1, 22) = 9.84, p = 0.005, η2p = 0.31 (see Table 3 and Figure 7).

Table 3.

Fixation Duration (seconds) by Modality and Task.

Figure 7.

Fixation duration by task difficulty level, group, and modality. Note: Error bars represent standard errors of the mean (SEM).

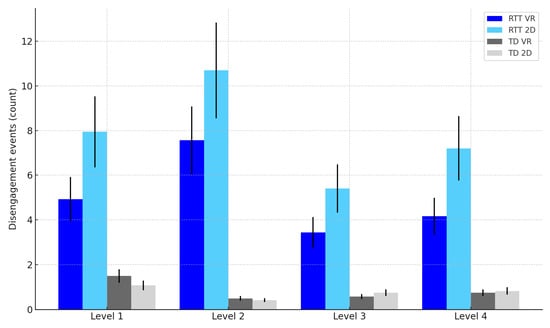

Disengagement: Fewer disengagements were observed in VR compared to 2D, F(1, 22) = 8.17, p = 0.009, η2p = 0.27 (see Table 4 and Figure 8).

Table 4.

Disengagement Events by Modality and Task.

Figure 8.

Disengagement events by task difficulty level, group, and modality. Note: Error bars represent standard errors of the mean (SEM).

Happiness Index: Median happiness was higher in VR for both RTT (Mdn = 6.0) and TD participants (Mdn = 6.0), Z = −2.56, p = 0.011 and Z = −2.43, p = 0.015, respectively.

These results confirm our hypothesis that immersive VR enhances attentional engagement and emotional responsiveness across both RTT and TD participants.

3.2. Modality × Group Interactions

We then analyzed interactions between group and modality to determine whether the benefits of VR differed for RTT versus TD participants.

Reaction Time: Significant Modality × Group interaction, F(1, 22) = 10.19, p = 0.004, η2p = 0.32, indicating that VR improved RTs more in RTT participants (see Table 2 and Figure 6).

Fixation Duration: Modality × Group interaction approached significance, F(1, 22) = 3.95, p = 0.060, η2p = 0.15, suggesting VR increased sustained attention more in RTT (see Table 3 and Figure 7).

Disengagement: Interaction significant, F(1, 22) = 5.22, p = 0.032, η2p = 0.19, showing stronger attentional stabilization in RTT (see Table 4 and Figure 8).

These interactions indicate that immersive VR provides greater cognitive and attentional benefits for RTT participants compared to TD peers.

3.3. Task Complexity Effects

We analyzed how task complexity influenced performance across groups and modalities. Reaction Time increased with higher task complexity in both groups, F(3, 69) = 15.42, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.41, reflecting the greater cognitive demands of more complex tasks. Fixation Duration decreased as task difficulty increased, F(3, 69) = 12.87, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.37, indicating reduced sustained attention under higher cognitive load. Disengagement events also rose with task complexity, F(3, 69) = 10.95, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.33, with a steeper increase in the RTT group, suggesting that individuals with RTT are more sensitive to increasing attentional demands. These results demonstrate that increasing task complexity challenges attentional and cognitive performance, particularly in RTT participants, as hypothesized. Full details are reported in Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4.

3.4. Happiness Index

Finally, we evaluated emotional engagement using the Happiness Index. Both RTT and TD participants showed higher happiness scores in VR compared to 2D. Wilcoxon tests confirmed significant increases in VR: RTT Z = −2.56, p = 0.011, r = 0.52; TD Z = −2.43, p = 0.015, r = 0.50 (see Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4).

These findings suggest that immersive VR enhances emotional engagement and intrinsic happiness, supporting the link between attentional engagement and affective responsiveness.

3.5. Group Differences (RTT vs. TD)

Next, we examined group differences to evaluate whether RTT participants performed differently from TD peers across conditions.

Reaction Time: RTT participants showed significantly slower RTs than TD peers, F(1, 22) = 95.34, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.81 (see Table 2).

Fixation Duration: The RTT group had shorter fixation durations than TD participants, F(1, 22) = 42.56, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.66 (see Table 3).

Disengagement: RTT participants exhibited more frequent disengagements, F(1, 22) = 27.48, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.56 (see Table 4).

Happiness Index: No significant baseline differences in happiness were observed between groups. These findings align with prior research on attentional and cognitive impairments in RTT, confirming expected group differences in performance and engagement.

4. Discussion

The present study investigated how immersive virtual reality (VR) environments influence visual–attentional and emotional engagement in girls with Rett Syndrome (RTT), compared to age-matched typically developing (TD) peers. Specifically, we examined how modality (2D vs. VR), task complexity, and group differences affect reaction times, fixation duration, attentional disengagement, and happiness during interaction with a naturalistic virtual forest scenario.

Consistent with previous research on cognitive processing in RTT [6,7,8], participants with RTT exhibited significantly slower reaction times, shorter fixation durations, and more frequent attentional disengagements than TD peers. These results confirm the expected attentional and motor control difficulties associated with RTT [1,3]. Despite these impairments, results revealed that VR immersion significantly improved attentional efficiency and emotional engagement across both groups, supporting the hypothesized modality effect. It is important to note that the control group was younger in chronological age but matched to the RTT group on functional abilities (GAIRS). This approach is common in studies of severe neurodevelopmental disorders and allows for valid comparisons of cognitive and attentional performance despite developmental delays in the RTT population.

The Modality × Group interactions for reaction time and disengagement further indicate that VR provided a greater cognitive benefit for RTT participants. Immersive environments likely enhance attentional engagement through multisensory stimulation and contextual realism, which promote orienting and sustained attention even in individuals with severe motor limitations [32,38,39]. These findings align with the literature showing that VR can modulate attention and happiness by activating emotional and reward-related neural circuits [33,34], thereby compensating for limited motor feedback in RTT.

As task complexity increased, performance declined across both groups, confirming the task complexity hypothesis. However, this decline was steeper for the RTT group, consistent with prior evidence that higher cognitive load exacerbates attentional disengagement in RTT [6,13]. Nonetheless, the presence of a significant VR benefit even at the highest task levels suggests that immersive interfaces may support cognitive engagement beyond the limits typically observed in this population.

The Happiness Index results corroborate the cognitive findings, showing significantly higher emotional engagement in the VR condition for both RTT and TD groups. This convergence between attentional and affective measures supports the idea that happiness and cognitive engagement are closely intertwined in immersive contexts [35,36]. In RTT, emotional responsiveness is a crucial indicator of well-being and cognitive activation, and the observed increase in happiness during VR interaction suggests that immersive experiences not only facilitate attention but also foster positive affect and intrinsic happiness.

Taken together, these findings contribute to the growing body of evidence highlighting the potential of immersive VR technologies as effective tools in neurodevelopmental rehabilitation [26,30,31]. The results demonstrate that VR can enhance attentional focus and emotional involvement even in individuals with profound motor and communicative limitations, supporting its use as both an assessment and training medium within Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) frameworks [18].

The present results also reinforce the view that gaze-based interaction, when combined with VR, can capitalize on the preserved visual–attentional potential in RTT [6,19]. Eye-tracking metrics provided objective evidence that VR enhances both sustained attention and reaction efficiency, possibly by increasing ecological validity and reducing cognitive fatigue. These outcomes extend previous findings showing that naturalistic virtual scenarios can promote curiosity, emotional engagement, and adaptive behavior [20,40,41].

From a practical standpoint, these results suggest that integrating VR-based gaze-controlled training into rehabilitation protocols may strengthen both cognitive and emotional dimensions of intervention in RTT. By combining visual attention exercises with immersive feedback, therapists may enhance happiness and reduce disengagement, fostering greater continuity and participation in therapy sessions. Furthermore, the alignment between attentional and emotional improvements underscores the value of personalized, emotionally salient environments in sustaining engagement over time—a crucial factor for populations with limited expressive capabilities.

Despite promising outcomes, several limitations must be acknowledged.

First, the sample size was small, reflecting the rarity of RTT, and may limit the generalizability of findings. Replication in larger and more diverse samples is needed to confirm the robustness of modality effects and interaction patterns. Given the small sample size, distributional assumptions (including normality) are difficult to verify reliably and may be sensitive to outliers. Although we used complementary non-parametric analyses and reported effect sizes to support robustness, replication in larger samples is needed, particularly for detecting smaller or higher-order interaction effects.

Second, the study employed a cross-sectional design, precluding conclusions about long-term cognitive or emotional benefits. Future longitudinal studies should examine whether repeated VR exposure leads to sustained improvements in attention, learning, or adaptive behaviors.

Third, although the happiness index provided valuable insight into emotional engagement, it was based on observational ratings rather than physiological measures (e.g., heart rate variability or facial electromyography). Incorporating multimodal indicators of affect would yield a more comprehensive understanding of emotional dynamics in RTT.

Fourth, while the virtual forest scenario offered ecological realism, future research should explore adaptive and personalized VR systems that can adjust task complexity in real time based on the user’s attentional state. Finally, potential issues related to sensory overload or cybersickness were not systematically assessed and should be carefully monitored in subsequent studies involving vulnerable populations. Another limitation of this study is that we did not empirically measure perceptual equivalence between the VR and 2D conditions (e.g., field of view, stereoscopic depth cues, level of immersion). Although the visual stimuli and task structure were identical, VR naturally provides a wider field of view and enhanced depth information, which may have contributed to differences in engagement or attentional allocation. Future studies should include controlled perceptual measurements to quantify these differences.

A further limitation concerns the mismatch in chronological age between the RTT and TD groups. Although TD participants were younger, groups were intentionally matched on functional abilities rather than age, using the GAIRS checklist as a validated index of cognitive, attentional, motor, and communicative functioning. This functional-matching approach is widely adopted in research on severe neurodevelopmental disorders, including RTT, where profound delays make chronological age an unreliable comparator [21,26,62]. In the present study, GAIRS scores did not significantly differ between groups, supporting functional comparability despite age disparities. Nonetheless, age-related factors—such as developmental maturity, prior exposure to digital interfaces, and general attentional readiness—may still have influenced performance. Future studies with larger samples incorporate developmental and clinical covariates to better disentangle their contribution to attentional and emotional engagement.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the present study provides empirical evidence that immersive VR environments can enhance both attentional engagement and emotional responsiveness in girls with RTT. The integration of gaze-based interfaces with naturalistic virtual scenarios represents a promising avenue for personalized neurorehabilitation, capable of stimulating cognitive, motivational, and affective processes even in conditions of severe motor impairment. Although further research is needed to refine protocols and confirm long-term effects, these results highlight the transformative potential of immersive technologies to promote participation, learning, and quality of life in individuals with Rett Syndrome and other neurodevelopmental disorders.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.A.F., M.S. and M.P.; methodology, R.A.F., M.S., A.N., G.I. and M.P.; software, A.N., G.I.; formal analysis, R.A.F.; data curation, R.A.F.; writing—original draft preparation, R.A.F., M.S. and M.P.; writing—review and editing, R.A.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Genua (protocol number 2023/97, date: 29 November 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Italian Rett Association for their support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| RARS | Rett Assessing Rating Scale |

| GAIRS | Global Assessment and Intervention for Rett Syndrome |

| RTT | Rett Syndrome |

| AOI | Area Of Interest |

| TD | Typically Developing |

| VR | Virtual Reality |

References

- Leonard, H.; Gold, W.; Samaco, R.; Sahin, M.; Benke, T.; Downs, J. Improving clinical trial readiness to accelerate development of new therapeutics for Rett syndrome. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2022, 17, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooley Coleman, J.A.; Fee, T.; Bend, R.; Louie, R.; Annese, F.; Stallworth, J.; Worthington, J.; Black Buchanan, C.; Everman, D.B.; Skinner, S.; et al. Mosaicism of common pathogenic MECP2 variants identified in two males with a clinical diagnosis of Rett syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2022, 188, 2988–2998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.A.; Kwon, W.K.; Kim, J.W.; Jang, J.H. Variation spectrum of MECP2 in Korean patients with Rett and Rett-like syndrome: A literature review and reevaluation of variants based on the ClinGen guideline. J. Hum. Genet. 2022, 67, 601–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skjeldal, O.H.; von Tetzchner, S.; Aspelund, F.; Herder, G.A.; Lofterłd, B. Rett syndrome: Geographic variation in prevalence in Norway. Brain Dev. 1997, 19, 258–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprì, T.; Santoddi, E.; Fabio, R.A. Multi-source interference task paradigm to enhance automatic and controlled processes in ADHD. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2020, 97, 103542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabio, R.A.; Caprì, T.; Iannizzotto, G.; Nucita, A.; Mohammadhasani, N. Interactive avatar boosts the performances of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in dynamic measures of intelligence. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2019, 22, 588–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabio, R.A.; Gangemi, A.; Semino, M.; Vignoli, A.; Priori, A.; Canevini, M.P.; Di Rosa, G.; Caprì, T. Effects of combined transcranial direct current stimulation with cognitive training in girls with Rett syndrome. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannizzotto, G.; Nucita, A.; Fabio, R.A.; Caprì, T.; Lo Bello, L. Remote Eye-Tracking for Cognitive Telerehabilitation and Interactive School Tasks in Times of COVID-19. Information 2020, 11, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, R.E.; Van den Veyver, I.B.; Wan, M.; Tran, C.Q.; Francke, U.; Zoghbi, H.Y. Rett syndrome is caused by mutations in X-linked MECP2, encoding methyl-CpG-binding protein 2. Nat. Genet. 1999, 23, 185–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.; Miller, M.T.; Li, K.; Sur, M.; Kaufmann, W.E. Towards a better diagnosis and treatment of Rett syndrome: A model synaptic disorder. Brain 2019, 142, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panayotis, N.; Ehinger, Y.; Felix, M.S.; Roux, J.C. State-of-the-art therapies for Rett syndrome. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2023, 65, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romano, A.; Caprì, T.; Semino, M.; Bizzego, I.; Di Rosa, G.; Fabio, R.A. Gross Motor, Physical Activity and Musculoskeletal Disorder Evaluation Tools for Rett Syndrome: A Systematic Review. Dev. Neurorehabil. 2020, 23, 485–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, W.A.; Krishnarajy, R.; Ellaway, C.; Christodoulou, J. Rett Syndrome: A Genetic Update and Clinical Review Focusing on Comorbidities. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2018, 9, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, E.; Zhao, T.; Sikora, T.; Ellaway, C.; Gold, W.A.; Van Bergen, N.J.; Stroud, D.A.; Christodoulou, J.; Kaur, S. CHD8 Variant and Rett Syndrome: Overlapping Phenotypes, Molecular Convergence, and Expanding the Genetic Spectrum. Hum. Mutat. 2025, 2025, 5485987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartl-Pokorny, K.D.; Pokorny, F.B.; Garrido, D.; Schuller, B.W.; Zhang, D.; Marschik, P.B. Vocalisation Repertoire at the End of the First Year of Life: An Exploratory Comparison of Rett Syndrome and Typical Development. J. Dev. Phys. Disabil. 2022, 34, 1053–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, T.; Ito, Y.; Ito, T.; Kidokoro, H.; Noritake, K.; Tsujimura, K.; Saitoh, S.; Yamamoto, H.; Ochi, N.; Ishihara, N.; et al. Pathological gait in Rett syndrome: Quantitative evaluation using three-dimensional gait analysis. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2023, 42, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neul, J.L.; Kaufmann, W.E.; Glaze, D.G.; Christodoulou, J.; Clarke, A.J.; Bahi-Buisson, N.; Leonard, H.; Bailey, M.E.; Schanen, N.C.; Zappella, M.; et al. Rett syndrome: Revised diagnostic criteria and nomenclature. Ann. Neurol. 2010, 68, 944–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahonniska-Assa, J.; Polack, O.; Saraf, E.; Wine, J.; Silberg, T.; Nissenkorn, A.; Ben-Zeev, B. Assessing cognitive functioning in females with Rett syndrome by eye-tracking methodology. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2018, 22, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byiers, B.; Symons, F. The need for unbiased cognitive assessment in Rett syndrome: Is eye tracking the answer? Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2013, 55, 301–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wandin, H.; Lindberg, P.; Sonnander, K. A trained communication partner’s use of responsive strategies in aided communication with three adults with Rett syndrome: A case report. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 989319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabio, R.A.; Giannatiempo, S.; Semino, M.; Caprì, T. Longitudinal cognitive rehabilitation applied with eye-tracker for patients with Rett Syndrome. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2021, 111, 103891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliorelli, C.; Medina-Rivera, I.; Bachiller, A.; Tost, A.; Alonso, J.F.; López-Sala, A.; Armstrong, J.; O’Callahan, M.D.M.; Pineda, M.; Mañanas, M.A.; et al. Cognitive stimulation has potential for brain activation in individuals with Rett syndrome. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2022, 66, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabio, R.A.; Caprì, T.; Nucita, A.; Iannizzotto, G.; Mohammadhasani, N. Eye-gaze digital games improve motivational and attentional abilities in Rett syndrome. J. Spec. Educ. Rehabil. 2018, 19, 105–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dovigo, L.; Caprì, T.; Iannizzotto, G.; Nucita, A.; Semino, M.; Giannatiempo, S.; Zocca, L.; Fabio, R.A. Social and Cognitive Interactions Through an Interactive School Service for RTT Patients at the COVID-19 Time. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 676238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vessoyan, K.; Steckle, G.; Easton, B.; Nichols, M.; Mok Siu, V.; McDougall, J. Using eye-tracking technology for communication in Rett syndrome: Perceptions of impact. Augment. Altern. Commun. 2018, 34, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabio, R.A.; Semino, M.; Perina, M.; Martini, M.; Riccio, E.; Pili, G.; Pani, D.; Chessa, M. Virtual Reality as a Tool for Upper Limb Rehabilitation in Rett Syndrome: Reducing Stereotypies and Improving Motor Skills. Pediatr. Rep. 2025, 17, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mraz, K.; Eisenberg, G.; Diener, P.; Amadio, G.; Foreman, M.H.; Engsberg, J.R. The Effects of Virtual Reality on the Upper Extremity Skills of Girls with Rett Syndrome: A Single Case Study. J. Intellect. Disabil.-Diagn. Treat. 2016, 4, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonzo, M.; Sirico, F.; Corrado, B. Evidence-Based Physical Therapy for Individuals with Rett Syndrome: A Systematic Review. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damianidou, D.; Arthur-Kelly, M.; Lyons, G.; Wehmeyer, M.L. Technology use to support employment-related outcomes for people with intellectual and developmental disability: An updated meta-analysis. Int. J. Dev. Disabil. 2018, 65, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabio, R.A.; Caprì, T.; Colombo, B.; Mohammadhasani, N. Editorial: New Technologies and Rehabilitation in Neurodevelopment. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 849888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settimo, C.; De Cola, M.C.; Pironti, E.; Muratore, R.; Giambò, F.M.; Alito, A.; Tresoldi, M.; La Fauci, M.; De Domenico, C.; Tripodi, E.; et al. Virtual Reality Technology to Enhance Conventional Rehabilitation Program: Results of a Single-Blind, Randomized, Controlled Pilot Study in Patients with Global Developmental Delay. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, S.; Brivio, E.; Riva, G.; Baños, R.M. Immersive Versus Non-immersive Experience: Exploring the Feasibility of Memory Assessment Through 360° Technology. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aida, J.; Chau, B.; Dunn, J. Immersive virtual reality in traumatic brain injury rehabilitation: A literature review. NeuroRehabilitation 2018, 42, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wankhede, N.L.; Koppula, S.; Ballal, S.; Doshi, H.; Kumawat, R.; Raju, S.; Arora, I.; Sammeta, S.S.; Khalid, M.; Zafar, A.; et al. Virtual reality modulating dynamics of neuroplasticity: Innovations in neuro-motor rehabilitation. Neuroscience 2025, 566, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capobianco, M.; Puzzo, C.; Di Matteo, C.; Costa, A.; Adriani, W. Current virtual reality based rehabilitation interventions in neuro developmental disorders at developmental ages. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2025, 18, 1441615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.M.; Tse, S.Y.; Chan, H.S.; Yip, H.T.; Cheung, H.T.; Geda, M.W. An Innovative Interactive Narrative Persona (INP) Approach for Virtual Reality-Based Dementia Tour Design (VDT) in Rehabilitation Contexts. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, B.; Bryant, L.; Hemsley, B. Virtual reality and augmented reality for children, adolescents, and adults with communication disability and neurodevelopmental disorders: A systematic review. Rev. J. Autism. Dev. Disord. 2022, 9, 160–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Abreu, B.C.; Masel, B.; Scheibel, R.S.; Christiansen, C.H.; Huddleston, N.; Ottenbacher, K.J. Virtual reality in the assessment of selected cognitive function after brain injury. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2001, 80, 597–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Natale, G.; Qorri, E.; Todri, J.; Lena, O. Impact of Virtual Reality Alone and in Combination with Conventional Therapy on Balance in Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review with a Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Medicina 2025, 61, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Keersmaecker, E.; Guida, S.; Denissen, S.; Dewolf, L.; Nagels, G.; Jansen, B.; Beckwée, D.; Swinnen, E. Virtual reality for multiple sclerosis rehabilitation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2025, 1, CD013834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabio, R.A.; Semino, M.; Nucita, A.; Iannizzotto, G.; Perina, M.; Caprì, T. The use of virtual reality in Rett Syndrome rehabilitation to improve the learning motivation and upper limb motricity: A pilot study. Life Span Disabil. 2023, 26, 245–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passaro, A.; Ghiaccio, L.; Stasolla, F. Virtual Reality and People with Neurodevelopmental Disorders. In The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Disability; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Holmqvist, K.; Nyström, M.; Andersson, R.; Dewhurst, R.; Jarodzka, H.; van de Weijer, J. Eye Tracking: A Comprehensive Guide to Methods and Measures; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kowler, E. Eye movements: The past 25 years. Vision Res. 2011, 51, 1457–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.; Vernooij, J.; Salvatori, D.; Hierck, B.P. Assessing cognitive load using EEG and eye tracking in 3D learning environments: A systematic review. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2025, 9, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionescu, A.; Ștefănescu, E.; Strilciuc, Ș.; Rafila, A.; Mureșanu, D. Correlating eye-tracking fixation metrics and neuropsychological assessment after ischemic stroke. Medicina 2023, 59, 1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilf, M.; Korakin, A.; Bahat, Y.; Koren, O.; Galor, N.; Dagan, O.; Wright, W.G.; Friedman, J.; Plotnik, M. Using virtual reality-based neurocognitive testing and eye tracking to study naturalistic cognitive-motor performance. Neuropsychologia 2024, 194, 108744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagberg, B.; Aicardi, J.; Dias, K.; Ramos, O. A progressive syndrome of autism, dementia, ataxia, and loss of purposeful hand use in girls: Rett’s syndrome: Report of 35 cases. Ann. Neurol. 1983, 14, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabio, R.A.; Martinazzoli, C.; Antonietti, A. Costruzione e standardizzazione dello strumento “R.A.R.S.” (Rett Assessment Rating Scale). Ciclo Evol. Disabil. 2005, 8, 257–281. [Google Scholar]

- Fabio, R.A.; Semino, M.; Giannatiempo, S. The GAIRS Checklist: A useful global assessment tool in patients with Rett syndrome. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2022, 17, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marschik, P.B.; Kaufmann, W.E.; Sigafoos, J.; Wolin, T.; Zhang, D.; Bartl-Pokorny, K.D.; Budimirovic, D.B.; Vollmann, R.; Einspieler, C. Changing the perspective on early development of Rett syndrome. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2013, 34, 1236–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einspieler, C.; Sigafoos, J.; Bartl-Pokorny, K.D.; Landa, R.; Marschik, P.B.; Rowan, E. Rett syndrome: Insights into the development of early communication skills. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2014, 56, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Maat, S. Communicatie Tussen Personen met een Diep Mentale Handicap en Hun Opvoed(St)Ers [Communication Between Persons with a Profound Intellectual Disability and Their Primary Caregivers]; Garant: Leuven, Belgium, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Petry, K.; Maes, B. Identifying expressions of pleasure and displeasure by persons with profound and multiple disabilities. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2006, 31, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negi, S.; Mitra, R. Fixation duration and the learning process: An eye tracking study with subtitled videos. J. Eye Mov. Res. 2020, 13, 10-16910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A.P. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics, 5th ed.; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Erceg-Hurn, D.M.; Mirosevich, V.M. Modern robust statistical methods: An easy way to maximize the accuracy and power of your research. Am. Psychol. 2008, 63, 591–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Kerby, D.S. The simple difference formula: An approach to teaching nonparametric correlation. Compr. Psychol. 2014, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziak, J.J.; Dierker, L.C.; Abar, B. The Interpretation of Statistical Power after the Data have been Gathered. Curr. Psychol. 2020, 39, 870–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakens, D. Sample size justification. Collabra Psychol. 2022, 8, 33267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.Y.; Lee, W.T.; Shieh, J.Y.; Huang, Y.H.; Wong, L.C.; Tsao, C.H.; Chiu, Y.L.; Wu, Y.T. Multidimensional development and adaptive behavioral functioning in younger and older children with Rett syndrome. Phys. Ther. 2022, 102, pzab297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.