Abstract

The results show that the numerical simulation error based on the RPI two-phase boiling heat transfer model is less than 5%, which is in good agreement with the test results. Compared with the original engine, the temperature near the spark plugs’ position of improvement in scheme 2 decreased by 8.4 K, and the maximum temperature difference between the cylinder head intake and exhaust decreased by 14 K. Moreover, the overheating degree of the water jacket wall is the lowest, avoiding the occurrence of film boiling, and the local maximum vaporization rate is less than 50%. The prototype tests also confirmed that the improvement scheme effectively enhanced the heat transfer performance of the water jacket. The inlet flow rate and temperature of the coolant have significant and complex effects on two-phase boiling heat transfer. Both too low a flow rate and too high a temperature will lead to local film boiling, deteriorating heat transfer. Too high a flow rate will blow away bubbles, while too low an inlet temperature will not cause boiling, both of which can only enforce convective heat transfer. Appropriately reducing the flow rate and increasing the temperature can effectively utilize the enhanced heat transfer potential of subcooled boiling, while also save pump power consumption and improving engine fuel economy. The average heat flux density of boiling heat transfer in this paper is 13.9% higher than that of the forced convective heat transfer. When designing a water jacket with boiling heat transfer, attention should be paid to the transport effect of convective motion on bubbles, controlling subcooled boiling in the high-temperature zone and preventing film boiling.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the thermal load of engines has been continuously increasing and the space has become more compact. There is a demand for the engine cooling system to develop towards smaller space, lower power consumption and higher efficiency [1,2,3]. An efficient cooling system can not only ensure the lubrication performance of engine oil but also prevent knocking, enhance the operational reliability of engines and reduce pollutant emissions [4,5,6]. Therefore, it is urgent to develop a new generation of more efficient, energy-saving and compact cooling systems.

The current research on the new generation of cooling systems mainly focuses on two aspects. One is the improvement of the cooling system structure, and the other is the development of new boiling phase change heat transfer enhancement technology [7]. In terms of structural improvement research, the cooling systems require precise cooling for high-temperature areas, while other areas should also be appropriately cooled. How to organize the flow field reasonably is a design challenge [8]. Cooling water jacket generally uses water distribution holes and various guide structures to distribute coolant flow [9,10]. Bi et al. [11] and Lu et al. [12] optimized the number and diameter of water distribution holes to optimize the coolant flow distribution, and results show that they meet the cooling demand of engines. Zeng et al. [13] incorporated baffles within the water jacket structure and enabled the coolant to flow preferentially toward the exhaust side. These optimization measures have collectively improved the cooling performance.

Boiling phase change heat transfer is one of the potential solutions for high heat flux density space heat transfer [14]. In recent years, research in the field of two-phase boiling heat transfer in engine cooling systems has mainly focused on two aspects. One is the study of two-phase boiling heat transfer inside the actual engine water jacket. Due to the extremely complex and enclosed structure of the water jacket channel, there are relatively few experimental studies on the two-phase boiling heat transfer of the cooling water jacket. The focus is on changing parameters to achieve visual verification of boiling inside the water jacket. Jie et al. used endoscopic high-speed photography in their experiment for boiling visualization. They successfully observed boiling bubbles and found that bubble diameter is inversely proportional to the inlet subcooling and flow rate [15]. Dong Fei successfully observed boiling occurring inside the water cavity by adjusting parameters and analyzed the effect of flow rate on bubble distribution and engine thermal load [16]. Numerical simulation research can more conveniently observe the flow and heat transfer details inside the water jacket, such as the temperature field, flow field and vaporization rate distribution of two-phase boiling heat transfer inside the water jacket, and verify the huge potential of two-phase boiling heat transfer compared with single-phase heat transfer [17,18]. Due to the complex geometric structure of the water cavity, establishing an effective mathematical model to accurately reflect the mechanisms of two-phase boiling heat transfer has become a current hotspot and challenge in this research area [19,20].

Another focus of boiling heat transfer is the use of simple pipes with regular geometric structures (such as a T-pipe) to simulate the boiling heat transfer process in the engine water jacket. Numerous scholars have conducted numerical simulations and experimental tests [21,22,23] for this purpose. Their numerical studies have evolved from single-phase to two-phase simulations, and due to the regularity of the pipe’s geometric structure, their internal two-phase boiling heat transfer model can accurately reflect the law of boiling heat transfer [24,25]. Therefore, current research on boiling heat transfer in simple channels with regular structures mainly focuses on parametric studies, hoping to understand the impact of inlet temperature, flow rate, pressure and degree of superheat on the conditions under which two-phase boiling occurs, in order to control the enhanced heat transfer technology of two-phase boiling [23,26].

However, parameterization studies for structurally regular channels cannot truly reflect the mutual influence between gas and liquid phases during boiling heat transfer in a water jacket with complex internal structures. For instance, a low-flow rate in locally narrow channels may lead to significant local accumulation of boiling bubbles, forming local film boiling that impedes heat dissipation. At the same time, this type of parameterization study generally observes changes in wall heat flux density with wall superheat under different parameters, using the transition from a linear to an accelerated upward change in heat flux density curve as an indicator of boiling heat transfer occurrence, thereby exploring the difficulty level of boiling under different parameters. However, for actual water jacket heat transfer, the main adjustable parameters are the inlet temperature and flow rate of the coolant, while it is actually difficult to directly adjust wall superheat artificially. Therefore, the results of such parameterization studies cannot be directly applied to control boiling heat transfer within engine water jackets. Moreover, the ultimate goal of engine water jacket boiling heat transfer research is to control two-phase boiling to enhance overall heat exchange performance. Therefore, it is necessary to study the impact mechanism of coolant inlet temperature and flow rate on boiling heat transfer performance, in order to effectively control boiling heat transfer and enhance heat exchange performance.

In light of this, to effectively control the heat transfer of gas–liquid two-phase boiling and enhance the heat transfer performance of the water jacket, this paper conducts research on the mechanism of boiling heat transfer in the engine’s cooling water jacket and its structural improvements. The RPI two-phase boiling heat transfer model is proposed for numerical simulation analysis of boiling heat transfer in the water jacket. The effect of the water jacket structure on the performance of boiling heat transfer is explored. Subsequently, a detailed analysis of the mechanism of boiling heat transfer and the influence of coolant inlet flow rate and temperature on boiling heat transfer is conducted.

2. Model Establishment

2.1. Mathematical Model

2.1.1. Eulerian Two-Phase Model

This paper employs the Fluent module of ANSYS R21 to conduct a numerical simulation of two-phase boiling heat transfer in the water jacket. The Eulerian model is adopted in this study to handle two-phase flow, where the vapor and liquid phases are treated as interpenetrating continuous media. The fraction of each phase is represented by introducing the phase volume fraction, with the sum of the volume fractions of the two phases equal to 1.

This model solves the mass conservation equation, momentum conservation equation and energy conservation equation for each phase. In the mass conservation equation, the mass transfer between the two phases caused by liquid boiling or bubble condensation was addressed by the mass source term. The momentum conservation equations of each phase were coupled through the pressure term and interphase forces. The energy conservation equations were coupled via the interphase heat transfer coefficient. The standard k-ε equation was employed in the Eulerian model to deal with turbulence, wherein k is the turbulent kinetic energy, and ε is the turbulent dissipation rate.

According to the calculations, the Reynolds number Re = 50,167 at the water jacket inlet, indicating that the coolant flow inside the water jacket is turbulent. The flow and heat transfer processes comply with the mass conservation, momentum conservation and energy conservation laws. The heat transfer mechanism in the internal cylinder head and block follows Fourier’s law of heat conduction, which also satisfies the law of energy conservation. The form of the energy control equation is the same as that of the coolant, but the energy control equation lacks convection terms and has different coefficients. The control equations are as follows.

The mass conservation equation

The momentum conservation equation

The energy conservation equation

wherein, ; is the volume fraction of phase k, , is the density of phase k; is the velocity vector of phase k; is the mass source term of phase k; p is the fluid pressure; is the dynamic viscosity of phase k; is the inter-phase momentum exchange term; is the temperature of phase k; is the specific heat capacity of phase k; is the coefficient of thermal conductivity of phase k; is the inter-phase energy exchange term.

2.1.2. RPI Two-Phase Boiling Heat Transfer Model

In Fluent, the wall boiling models are included under the Eulerian multiphase flow framework. Wall boiling is modeled using the RPI nucleate boiling model by Kurual and Podowski [27] and the DNB model proposed by Lavieville et al. [28]. The RPI model, in particular, features clear physical mechanisms and strong engineering practicality. By modeling bubble behavior, it can predict nucleate boiling heat transfer with high accuracy. It is especially suitable for nucleate boiling and not applicable to film boiling. Therefore, the RPI model is adopted in this simulation. Literature [17] also confirms that using this model yields more accurate simulation results for engine water jacket cooling compared with the single-phase model. The RPI model divides the total heat flux from the wall to the liquid phase into three components: convective heat flux, quenching heat flux and evaporative heat flux.

The heated wall is divided into two parts: one is the area covered by nucleating bubbles , and the other is the area covered by the liquid (). The bubble coverage area is a physical quantity defined based on bubble detachment diameter and nucleation site density, expressed as follows:

To avoid numerical instability, the influence area has to be limited. The influence area must be restricted:

The empirical constant K is typically taken as 4. However, this value is not universal, with a range of 1.8 to 5. is the nucleation site density, which is usually expressed via a correlation coefficient based on wall superheat. It is generally expressed as follows:

The convective heat flux refers to the heat flux via convection between the wall not covered by bubbles and the coolant:

In the formula, represents the single-phase heat transfer coefficient; and represent the wall temperature and liquid phase temperature, respectively.

The quenching heat flux simulates heat exchange produced when the coolant rapidly fills the contact wall after the bubble detachment:

In the formula, represents the liquid phase thermal conductivity, T represents the period time and represents the diffusion rate .

The evaporative heat flux refers to the heat absorbed by the coolant during its phase transition from liquid to vapor bubbles.

In the formula, represents the volume of bubbles detaching from the wall; is the activated nucleation site density; is the vapor phase density; is the latent heat of evaporation; and f is the bubble detachment frequency. The RPI model uses the bubble detachment frequency as a frequency based on inertia control growth.

is the bubble detachment diameter. In this simulation, the Tolubinski–Kostanchuk under the default condition of Fluent is selected, and the empirical formula [29] is used for calculation.

2.2. Model Establishment

2.2.1. Geometry Model

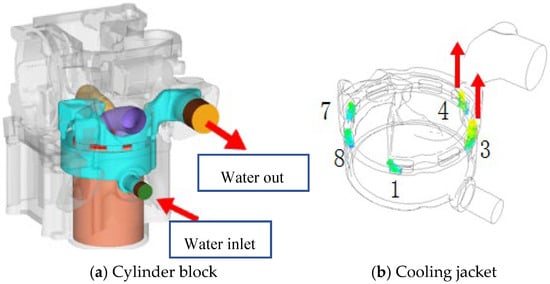

The original geometric model of the jacket body was established using UG NX 12.0 software. During the modeling process, small oil passage holes and bolt holes inside the body were removed, along with filets, chamfers and a small reinforcing rib. The model is shown in Figure 1. The main technical parameters of the engine are as follows: cylinder diameter: 66.4 mm; stroke: 69.6 mm; compression ratio: 9.6; rated speed: 6000 rpm; and rated power: 13.5 kW. To meet the requirements of numerical simulation, the inlet and outlet sections of the jacket were extended. Finally, the fluid domain model and solid domain model were integrated.

Figure 1.

Prototype cylinder body and cooling jacket geometry model.

The thermal load on the engine cylinder head is significant, necessitating focused cooling while ensuring that the entire cylinder body receives appropriate cooling without any flow dead zones in the water jacket. For this reason, the original engine cooling water jacket adopts a hybrid cooling approach with the main inlet located at the lower part of the cylinder body and the outlet set at the upper part. A portion of the coolant directly enters the cylinder head water jacket through water distribution holes 3 and 4; another portion begins to flow around the cylinder body in the cylinder body water jacket tangentially, achieving cooling of the cylinder body. Subsequently, it enters the cylinder head water jacket through water distribution holes 1, 7 and 8. The flow rates of these two coolant streams are regulated by the water distribution holes. Finally, all coolant leaves from the outlet at the upper part of the intake side of the cylinder head after cooling it. It can be seen that, in addition to the overall inlet design, the coolant diversion via water distribution holes is critical to achieving the cooling requirement.

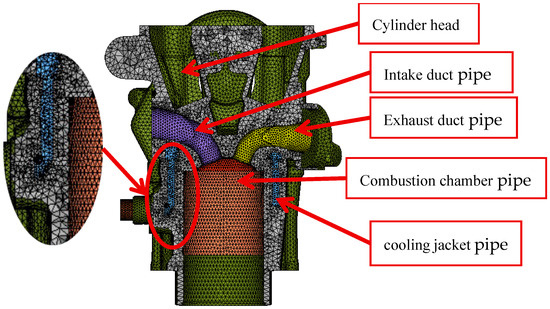

The HyperMesh 2021 software was used for mesh generation, adopting a tetrahedral body mesh. The fluid domain and solid domain were meshed separately first and then the two mesh systems were merged. To improve the simulation accuracy, a grid independence test was carried out. When the number of grids was 367,000, the temperature at the center of the combustion chamber wall was 434.1 K and the wall temperature at the spark plug was 421.4 K. After reducing the grid size, when the number of grids increased to 671,000, the temperature at the center of the combustion chamber wall reached 440.1 K and the wall temperature at the spark plug was 404.9 K. When the number of grids was further increased to 1,143,000, the temperature at the center of the combustion chamber wall was 441.6 K and the wall temperature at the spark plug was 402.1 K. It can be seen that further reducing the grid size and increasing the number of grids had a negligible impact on the simulation results at this stage. Therefore, after passing the grid independence test, the scheme with a maximum grid size of 3 mm and a volume mesh of 671,000 was finally adopted. The mesh in the water separation area and near the combustion chamber of the engine body was refined. After passing the grid independence check, the final maximum mesh size was 3 mm, with approximately 510,000 body meshes. Figure 2 shows the fluid-solid coupling mesh model.

Figure 2.

Cylinder body and cooling jacket fluid-solid coupling grid model.

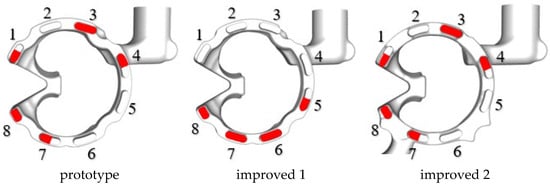

2.2.2. Boundary Condition of Model

A simulation was carried out under the rated operating condition, with a rotational speed of 6000 rpm. The tested inlet temperature was 354.2 K, and the inlet flow rate was 1.06 m/s, while the outlet was set as the outflow boundary condition. From the original water jacket in Figure 3, it can be seen that the coolant entering the water jacket through the inlet flows into the outlet via five water distribution holes of varying sizes. The fluid-solid interface was an internal coupling boundary. A zero-dimensional model of the ALV-BOOST 5.1 software was employed to simulate the engine operating process. The simulation results were validated against the experimentally measured cylinder pressure, power and torque data, which ensured the reliability of the results. After calculating the instantaneous in-cylinder gas heat transfer coefficient and temperature via this model, the cycle-averaged heat transfer coefficient and temperature were converted using Equations (13) and (14), and the values here are also spatial averages [30,31]. The above literature studies have confirmed that the simulation results obtained by this thermal boundary processing method can meet the requirements of engineering applications. The average gas temperature in the combustion chamber is 1358 K, with a heat transfer coefficient of 714 W/(m2·K). The gas temperature in the exhaust channel is 1093 K, with an average heat transfer coefficient of 472 W/(m2·K). The gas temperature in the intake channel is 307 K, with an average heat transfer coefficient of 262 W/(m2·K). The ambient temperature is 301 K, and the average heat transfer coefficient between the air and the outer wall of the engine body is 65 W/(m2·K). The engine block is made of aluminum alloy with a thermal conductivity of 167.2 W/(m2·K). Using the SIMPLE algorithm. The calculation was considered converged when the residuals dropped below 1 × 10−4.

Figure 3.

Water distribution holes of the three water jacket schemes.

3. Results Analysis

3.1. Deficiencies of Prototype Water Jacket

When assuming that the water jacket was filled with a pure liquid phase for heat transfer simulation, it was found that in the area near the exhaust side of the cylinder water jacket, the temperature exceeded 373.15 K, reaching a maximum temperature of 466 K. This exceeds the saturation temperature at the corresponding pressure, indicating the occurrence of boiling phenomena. Therefore, the RPI boiling model was adopted to simulate the two-phase boiling heat transfer process within the water jacket.

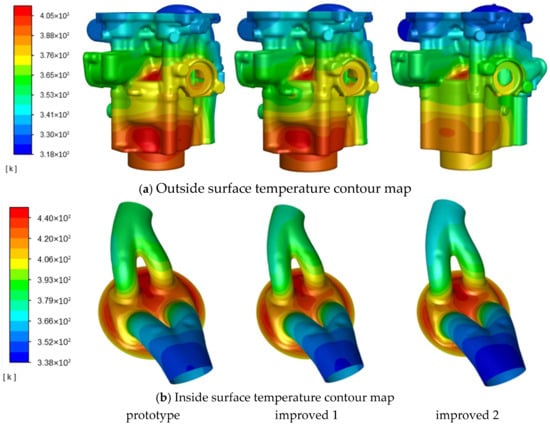

Figure 4a shows the simulated body temperature, where the entire cylinder body temperature distribution is uneven. The temperatures near the combustion chamber and exhaust pipe are higher, with the highest external surface temperature being 405 K, and the surface temperature at the spark plug position being 404.9 K. The temperature near the top of the internal combustion chamber is the highest, reaching a maximum of 440.1 K. The maximum temperature on the exhaust side is 83.3 K higher than that on the intake side. It can be seen that, first, the high thermal load is detrimental to the service reliability of the material; second, the large temperature gradient induces significant thermal stress, leading to excessive deformation of the cylinder liner and increased local wear. Additionally, an analysis of the coolant revealed that the flow rate on the intake side is larger than that on the exhaust side, increasing the temperature difference between them. Moreover, there exists a local low-flow area in the water jacket on the exhaust side. In light of this, improvements are proposed for the water jacket scheme.

Figure 4.

Temperature comparison of cylinder bodies of different models.

3.2. Improved Schemes of Water Jacket

Addressing the shortcomings of the original cooling jacket, two improvement schemes are proposed as shown in Figure 3. The first improvement scheme is based on the original plan: close water distribution holes 1, 3 and 4, increase the diameter of water distribution hole 7 and add new water distribution holes 6 and 5. This ensures that all coolant is forced to first flow around the cylinder jacket, then enter the cylinder head jacket through water distribution holes 8, 7, 6 and 5 to cool the cylinder head. In this way, more coolant can enter the cylinder head jacket through water distribution holes 8 and 7 to cool the high-temperature area near the combustion chamber, while also increasing the amount of coolant on the exhaust side in the jacket.

The second improvement scheme is to set the total water inlet on the exhaust side of the cylinder head based on the original water jacket and make its inlet form an angle with the body to reduce flow resistance. The total water outlet is set on the air intake side of the cylinder head, which can reduce the temperature difference between the air intake and exhaust sides. A part of the coolant directly cools the cylinder head and finally flows out from the total water outlet located on the air intake side. This part is able to target the cooling high-temperature area. Another part of the coolant enters the cylinder block water jacket through water distribution holes 1, 7 and 8, forms a circumferential flow in the cylinder block water jacket and finally enters the cylinder head water jacket through water distribution holes 3 and 4 and flows out from the total water outlet.

3.3. Numerical Analysis of Heat Transfer Performance of Improved Schemes

Figure 4 shows a comparison of the simulation results for three different schemes under identical boundary conditions. Overall, the body temperature of the improved scheme is significantly lower than that of the original scheme, with the improved scheme 2 having the lowest temperature. Taking the maximum temperature at the spark plug as an example, the original scheme was 404.9 K, improved scheme 1 was 402.3 K, which is a decrease of 2.6 K compared to the original scheme, and improved scheme 2 was 396.5 K, a decrease of 8.4 K compared to the original scheme. It can be seen that the improved scheme has a significant effect on improving the high-temperature area near the combustion chamber. The temperature differences between the intake and exhaust sides of the original scheme, improved scheme 1 and improved scheme 2 were 70.3 K, 63.8 K and 56.3 K, respectively. It can be observed that improved scheme 2 performs best, reducing the maximum temperature difference by 14 K. Improved scheme 2 meets the design requirements, reduces the thermal stress caused by temperature difference and is beneficial for reducing cylinder wear.

Both improvement schemes have enhanced the cooling of the high-temperature area on the exhaust side. Compared to the original scheme, the average temperature in the exhaust channel decreased by 3.1 K for improved scheme 1 and by 10.7 K for improved scheme 2. The highest temperature for all three schemes occurred near the exhaust side at the top of the combustion chamber. The maximum temperature for the original model was 440.1 K, which dropped to 437.2 K for improved scheme 1, a decrease of 2.9 K compared to the original; for the improved scheme 2, it was 435.3 K, a reduction of 4.8 K from the original.

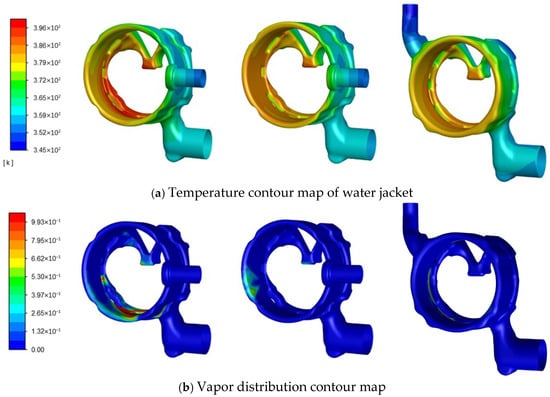

Figure 5a shows the cooling water jacket temperature, with the maximum temperature of the original scheme, improved scheme 1 and improved scheme 2 being 396.1 K, 388.8 K and 385.8 K, respectively. It can be seen that the heat transfer performance of the improved schemes has significantly improved, with the boiling heat exchange effect of improved scheme 2 being the best. The maximum wall superheat of the water jacket in improved scheme 2 is the smallest, and within a certain range, improved scheme 2 can better avoid the film boiling caused by excessive superheat.

Figure 5.

Temperature, vapor phase and path-line distribution of different models.

Figure 5b and Figure 5c, respectively, show the vaporization rate and streamline diagram of the water jacket cooling system for three different schemes. Compared to the original water jacket, the overall coolant flow distribution in the improved scheme is more uniform. The local maximum flow rate for improved schemes 1 and 2 is 2.073 m/s and 1.519 m/s, both lower than the original scheme’s 4.05 m/s. In the original scheme, there is a lack of coolant in the exhaust side cylinder water jacket, leading to the formation of flow dead zones and local gas content exceeding 90%. In improved scheme 1, the coolant eliminates these flow dead zones, especially in the cylinder head area, where the flow through the orifices is significantly higher than in the original scheme. After optimization, the local gas content on the exhaust side of the water jacket is also less than 50%, with the highest gas content reaching 66% in the bridge area of the water cavity.

Improved scheme 2 has changed the location of the coolant inlet, prioritizing the cooling of the bridge area and the exhaust side body. Boiling mainly occurs near the water distribution holes of the cylinder jacket. Overall, the improved scheme 2 is the most effective and should be adopted as the improved model’s jacket solution.

4. Simulation Verification and Prototype Comparison

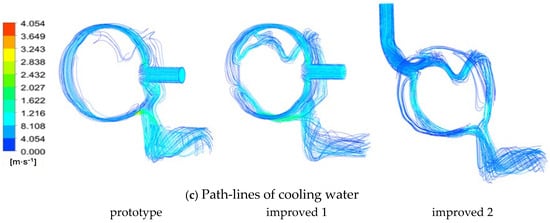

Set up two temperature measurement points. Measurement point 1 is located near the spark plug, and measurement point 2 is located near the center of the surface of the combustion chamber. The thermocouple used has a temperature measurement range of 223.15 K to 1573.15 K and an accuracy of 0.1 K. Figure 6 is the experimental test platform. The test was conducted twice, and the data obtained from the two runs are in close agreement. The arithmetic mean of these two experimental results was adopted for comparison with the single numerical simulation result presented. A blower was used to simulate the airflow during the test, and the airflow velocity was determined by the engine operating conditions. When the blower is turned on, the speed and throttle of the engine are controlled by the control system, and the temperature is measured after the engine has operated stably for approximately 1 h. It can be seen in Table 1 that the simulated values are in good agreement with the test values. And the temperature of the improved model is lower than that of the original model.

Figure 6.

Test platform.

Table 1.

Simulation verification.

5. Research on the Mechanism and Control of Enhanced Heat Transfer in Gas–Liquid Two-Phase Boiling

5.1. Study on the Influence Mechanism of Flow Rate on Boiling Heat Transfer

The mechanism of heat transfer in gas–liquid two-phase boiling differs significantly from that of pure liquid phase convection, and it requires operation within the safety zone of subcooled boiling. Therefore, in order to reasonably utilize the enhanced heat transfer capability of two-phase boiling, a study on the mechanism of gas–liquid two-phase boiling heat transfer is conducted based on improved scheme 2. During the process of two-phase boiling heat transfer, the wall superheat in the high-temperature regions induces bubble nucleation and boiling. Overall, there are two types of heat transfer mechanisms in the water jacket: liquid phase convection heat transfer and boiling phase change heat transfer. At the same time, the generated bubbles and convective transport interact with each other, changing the flow and heat transfer in the water jacket. The volume of gas is greater than that of liquid, which leads to a decrease in local flow area, an increase in the local liquid flow rate, turbulence intensity and convective heat transfer coefficient. The flowing liquid has a convective transport effect on the bubbles, changing the growth and distribution pattern of the bubbles, thereby affecting the vaporization rate and boiling heat transfer. Finally, changes in the local temperature of the coolant enhance the coupled influence mechanism between bubbles and convective motion. It can be seen that the influence mechanism of temperature and flow rate on gas–liquid two-phase boiling heat transfer is different from that of pure liquid phase convection, and it is more complex. Based on this, a simulation study on boiling heat transfer is carried out by changing the temperature and flow rate of the coolant.

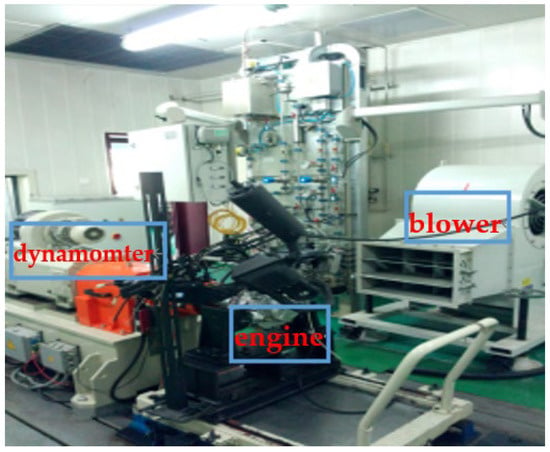

Using the same boiling heat transfer model, we simulated the heat transfer process of coolant with an inlet temperature of 354.15 K and inlet flow rates of 0.6 m/s, 0.8 m/s, 1.2 m/s and 1.4 m/s in the water jacket. The average temperature of the water jacket, the average temperature of the coolant and the average heat flux density of the water jacket are shown in Figure 7. All data shown in Figure 7 were acquired from a single Fluent simulation.

Figure 7.

The Influence of Inlet Flow Rate on Boiling Heat Transfer.

As shown in Figure 7, with the increase in coolant flow rate, the average heat flux density of the water jacket increases regardless of whether it is single-phase convective heat transfer or two-phase boiling heat transfer. This result is consistent with that reported in Reference [26]. However, when it exceeds 1 m/s, the rate of increase slows down significantly. As can be seen from Figure 8, when the flow rate increases from 0.6 m/s to 1 m/s, a noticeable boiling phenomenon occurs within the water jacket. As shown in Table 2, the area-averaged vapor fraction decreases sharply from 3.2% at 0.8 m/s to 0.06% at 1.2 m/s, indicating that the boiling bubbles are blown away and the boiling phenomenon is significantly suppressed. At this time, there are two types of heat transfer phenomena in the water jacket: forced convection heat transfer of pure liquid phase and boiling phase change heat transfer. When the flow rate exceeds 1 m/s, on one hand, due to the further increase in forced convection transport effect of the liquid phase, the boiling bubbles are blown away; on the other hand, at this time, the average temperature of the coolant is lower, thus reducing or even completely eliminating the boiling phenomenon in the water jacket. It can be seen that the thermal load required for the initiation of boiling increases with the rise in flow rate. Consistent with the findings in References [26,32], a higher flow rate makes boiling less likely to occur. Therefore, during this stage, the water jacket is essentially subjected to pure liquid phase forced convection heat transfer, so the increase rate of average heat flux density with increasing flow rate is lower than that before the condition of 1 m/s.

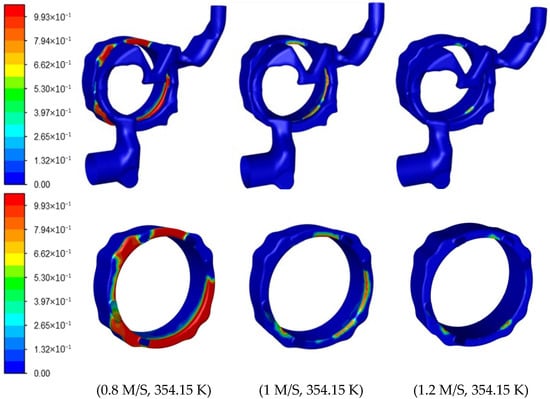

Figure 8.

Influence of flow rate on the distribution pattern of boiling bubbles.

Table 2.

Area-average vapor fraction at different inlet rates (353 K).

As the flow rate increases, both the average temperature of the jacket wall and the coolant decrease, and the rate of decline slows down significantly when the flow rate exceeds 1 m/s. Upon analysis, this is due to the fact that at lower flow rates, boiling heat transfer and convective heat transfer occur within the jacket. As the flow rate increases, both boiling and convective heat transfer mechanisms are enhanced, resulting in a faster decrease in wall temperature. However, at higher flow rates, only convective heat transfer occurs within the jacket. As the flow rate increases, only convective heat transfer is enhanced, leading to a slower decrease in wall temperature. It can be seen that when the flow rate is too high, it cannot fully utilize the potential of two-phase boiling to enhance heat transfer. At this point, increasing the flow rate has a diminishing marginal effect on improving heat transfer efficiency. From 0.6 m/s to 1 m/s, the average temperature of the coolant drops rapidly, and combined with Figure 8, it can be inferred that subcooled boiling occurs within the jacket at this time. This indicates that as long as the flow rate is not too low, film boiling will not occur within the jacket, allowing for good use of the potential of two-phase boiling to enhance heat transfer.

In summary, when the flow rate is moderate, subcooled boiling occurs in the water jacket. At this time, the heat transfer potential of two-phase boiling can be fully utilized to enhance the heat exchange capacity. Simultaneously, maintaining a lower flow rate is also beneficial for saving pump power consumption and improving engine output efficiency.

Figure 8 shows the boiling distribution within the water jacket at different flow rates. The figure indicates that the boiling bubbles are primarily distributed on the upper wall surface of the cylinder’s water jacket. Under the effects of convective transport and buoyancy, the boiling bubbles detach from the heating wall surface and converge in the low-flow rate area near the water-separating gasket, forming a localized bubble accumulation zone. When the inlet flow rate is 0.8 m/s, the bubble accumulation area is larger and the wall temperature is also higher. When the inlet flow rate increases to 1.2 m/s, the bubble accumulation area significantly decreases and the wall temperature drops. It can be seen that, consistent with the results in Reference [21], the vapor fraction decreases as the flow rate increases.

It can be seen that convective motion has a significant transport effect on bubbles and both excessively high and low flow rates are not conducive to enhancing heat transfer by boiling. Additionally, for complex channels in the water jacket, attention should be paid to the convective motion’s transport effect on bubbles, controlling subcooled boiling in high-temperature areas while preventing the occurrence of film boiling.

5.2. Study on the Effect Mechanism of Temperature on Boiling in the Water Jacket

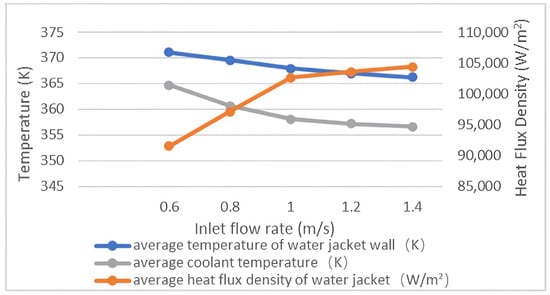

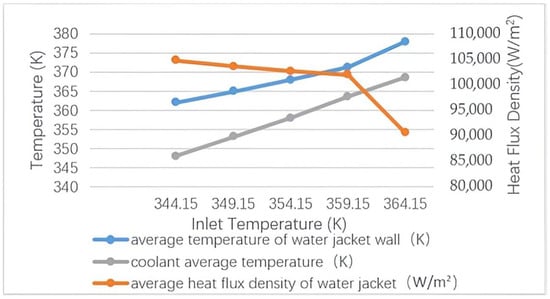

Using the same boiling heat transfer model, we simulated the two-phase boiling flow heat transfer process in a water jacket with an inlet flow rate of 1 m/s and inlet temperatures of 344.15 K, 349.15 K, 354.15 K, 359.15 K and 364.15 K, respectively. The average temperature of the water jacket, the average temperature of the coolant and the average heat flux density of the water jacket are shown in Figure 9. The data in Figure 9 were all acquired from a single Fluent simulation.

Figure 9.

The influence of inlet temperature on boiling heat transfer.

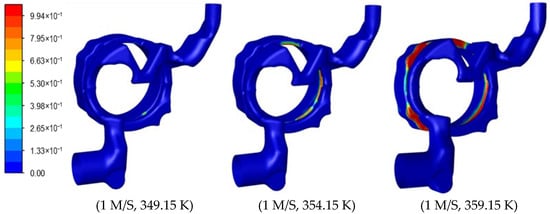

As shown in the figure, with the increase in the inlet temperature of the coolant, the average heat flux density of the water jacket decreases regardless of whether it is a single-phase convective heat transfer or a two-phase boiling heat transfer, and this result is consistent with that reported in Reference [33]. However, when it exceeds 359.15 K, the heat flux density significantly drops and the heat transfer capability rapidly deteriorates. As can be seen from Figure 10, when the temperature reaches 359.15 K, there are multiple large-area boiling phenomena within the water jacket and local boiling has developed to a considerable extent. It can be predicted that when the temperature exceeds 359.15 K, film boiling occurs, leading to a rapid deterioration of the heat exchange capability of the water jacket.

Figure 10.

Influence of inlet temperature on the distribution pattern of boiling bubbles.

As the inlet temperature increases, both the average temperature of the coolant and the average temperature of the jacket wall rise. Moreover, when the temperature rises from 344.15 K to 359.15 K, the rate of increase in the average temperature of the jacket wall is lower than that of the average temperature of the coolant, leading to a decrease in the average heat transfer difference. And the rate of this decrease is greater than the rate of decrease in heat flux density (44% vs. 27%), indicating that boiling heat transfer occurs at this stage, with boiling enhancing the heat transfer. It also indicates that boiling is more likely to occur as the inlet temperature increases, and this result is consistent with those reported in References [14,26,33]. When the inlet temperature exceeds 359.15 K, the average wall temperature significantly increases and its increase rate is clearly higher than the average coolant temperature, verifying that local film boiling deteriorates heat transfer at this time.

In summary, the inlet temperature of the coolant should not be too high to prevent local film boiling from deteriorating heat transfer. When the temperature is too low, boiling does not occur in the water jacket and the two-phase boiling heat enhancement technology is not utilized. Although the total heat flux density at this time is large, it is entirely achieved by a larger convective heat transfer temperature difference. To maintain a larger convective heat transfer temperature difference, it is necessary to keep the average temperature of the cooling water at a lower level, which can only be achieved by designing larger water jacket flow channels and increasing the water supply of the water pump. It can be seen that this does not conform to the development trend of modern engine compact structures, and more importantly, it increases the power consumption of the water pump and reduces the output power of the engine.

Figure 10 shows the distribution of coolant bubbles at different inlet temperatures. Different inlet temperatures lead to differences in wall superheat, which in turn affect boiling within the water jacket. As the temperature rises, the number of boiling bubbles in the water jacket increases and the area of bubble aggregation enlarges. If the inlet temperature continues to increase, it may lead to the occurrence of local film boiling, deteriorating heat transfer. When the inlet temperature is too low, boiling phenomena are rare and cannot fully utilize the heat transfer enhancement capability of two-phase boiling. As shown in Figure 10, bubbles gather near the water splitter gasket. This is a phenomenon of subcooled boiling with bubble aggregation in narrow channels. When controlling this kind of boiling, attention should be paid to the disturbance of convective motion. This disturbance may change the flow and distribution of the coolant within the water jacket.

Finally, based on improved scheme 2, both single-phase forced convection model and two-phase boiling heat transfer model were used to simulate the heat transfer process of the water jacket-engine body solid-fluid coupling, with a coolant inlet flow rate of 1 m/s and an inlet temperature of 354.15 K. From Table 3, during two-phase boiling heat transfer, the maximum temperature on the combustion chamber wall was reduced by 18.5 K compared to that of single-phase forced convection. The maximum temperature on the outer wall of the engine body decreased by 22.8 K compared to that of the latter. The average heat flux density increased by 13.9% compared to the latter. It can be seen that fully utilizing two-phase boiling heat transfer technology can significantly enhance the heat transfer effect of single-phase forced convection.

Table 3.

Characteristic temperature comparison: single-phase vs. two-phase boiling (1 m/s, 354.15 K).

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- The engine in the paper has a high thermal load and boiling occurs within the water jacket. Therefore, using the RPI two-phase boiling heat transfer model for numerical simulation is more suitable, with a simulation error of less than 5%. The simulation results are in good agreement with the experimental data.

- (2)

- The original machine model has issues with localized high temperature and significant temperature differences, which affect its lifespan. We propose improvements to the water distribution holes and the total inlet and outlet scheme to address this issue. Compared to the original machine, the temperature at the spark plug position in the improved scheme 2 decreased by 8.4 K, and the maximum temperature difference between the intake and exhaust of the cylinder head decreased by 14 K. Moreover, the local maximum gasification rate is less than 50%. Prototype testing also confirmed that the improved scheme effectively enhanced the heat exchange performance of the water jacket.

- (3)

- A too low flow rate may lead to local film boiling, which deteriorates heat transfer. An excessively high flow rate will strongly disperse the boiling bubbles, resulting in a heat transfer method of pure liquid phase convection, which cannot utilize the enhanced heat transfer capability of two-phase boiling. Appropriately reducing the flow rate can not only take advantage of the enhanced heat transfer efficiency of subcooled boiling, but also save pump power consumption and improve engine fuel economy.

- (4)

- The complex structure of the actual engine jacket enhances the convective motion’s transport effect on bubbles, while the narrow channel also intensifies the disturbance of bubbles to the convective motion. During design, attention should be paid to this transport effect, controlling subcooled boiling in the high-temperature zone and preventing the occurrence of film boiling.

- (5)

- An excessively low inlet temperature of coolant cannot generate boiling and higher cooling efficiency can only be achieved by increasing the flow rate, leading to an increase in the power consumption of the water pump. An excessively high inlet temperature will cause local film boiling, which will deteriorate heat transfer. Only by designing an appropriate inlet temperature can the two-phase enhanced heat transfer capability of subcooled boiling be utilized effectively.

- (6)

- The rational design of the water jacket structure and coolant inlet parameters can effectively utilize the heat transfer potential of boiling. In this paper, the average heat flux density of two-phase boiling is increased by 13.9% compared to pure forced convection, which helps to reduce the power consumption of the water pump and improve fuel economy.

Author Contributions

G.T.: Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Writing—review and editing, Validation, Project administration, Funding acquisition. C.Y.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation General Project of Chongqing Municipal: [Grant No. CSTB2022NSCQ-MSX1359].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be available on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Foundation and Advanced Research Program General Project of Chongqing City, China, through grant cstc2022jcyjA0499 for support of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Thomaz, F.; Malaquias, A.C.T.; de Paula, G.A.R.; Baêta, J.G.C. Thermal management of an internal combustion engine focused on vehicle performance maximization: A numerical assessment. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part D J. Automob. Eng. 2021, 235, 2296–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Zhang, W.B.; Wang, G.Y.; Huang, M.; Sui, J.; Zhao, H.M. Experimental study of dual-cycle thermal management system for engineering radiator. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 19691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhao, X.; Chen, J. Effects of cold start control strategy on cold start performance of the diesel engine based on a comprehensive preheat diesel engine model. Appl. Energy 2018, 210, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanivuk, T.; Lalic, B.; Mikulicic, J.Z.; Sundov, M. Simulation Modelling of Marine Diesel Engine Cooling System. Trans. Marit. Sci. 2021, 10, 112–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.J.; Ma, Y.D.; Xu, Y.K.; Wu, Y.X.; Dong, L.P.; Yu, Z.H.; Zhang, Y.L. Performance Study of Cooling System for a High-Power Heavy Truck Based on 1D/3D Coupled Simulation. Automot. Eng. 2024, 46, 1125–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naderi, A.; Qasemian, A.; Shojaeefard, M.H.; Samiezadeh, S.; Younesi, M.; Sohani, A.; Hoseinzadeh, S. A smart load-speed sensitive cooling map to have a high-performance thermal management system in an internal combustion engine. Energy 2021, 229, 120667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.H.; Xu, Z.X.; Wang, J.C.; Xu, T.S.; Lin, Z.F.; Ma, L. Research on Subcooled Boiling Multiphase Flow Simulation and Engine Cooling Structure. Automob. Technol. 2020, 2, 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, L.; Zhang, J.; Hao, G. Influence of cooling gallery structure on the flow patterns of two-phase flow and heat transfer characteristics. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2020, 110, 104407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhang, P.; Zeng, F.M. Multiobjective optimization of the cooling system of a marine diesel engine. Energy Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 1887–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.; Kim, K.; Yang, K.; Suh, I.; Kim, H. The CAE Analysis of a Cylinder Head Water Jacket Design for Engine Cooling Optimization. In Proceedings of the WCX World Congress Experience, Detroit, MI, USA, 10–12 April 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bi, Y.H.; Chen, S.J.; Yao, G.Z.; Chen, M.Y.; Shen, L.Z.; Xia, K.L. Study on the influence of coolant flow uniformity on the thermal deformation of cylinder liner. Automot. Eng. 2021, 43, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, R.J.; Wang, W.K.; Chen, H.L.; Cai, W.Y. Analysis and optimization design of engine cooling water jacket. Mach. Des. Manuf. 2018, 44, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; An, C.H.; Hu, P.; Li, L.B.; Wei, H.; Li, S.Q. The Thermodynamics Simulation Analysis and Optimization of Novel Two-cylinder Engine Water Jacket. Small Intern. Combust. Engine Veh. Tech. 2020, 49, 11092. [Google Scholar]

- Gholinia, M.; Pourfallah, M.; Chamani, H.R. Numerical investigation of heat transfers in the water jacket of heavy duty diesel engine by considering boiling phenomenon. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2018, 12, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Cao, T.; Hou, L.; Dong, F. Experimental study on bubble size distribution of subcooled flow boiling in cylinder head of internal combustion engines. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2019, 33, 913–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, F.; Gong, W.; Zhang, W.W.; Yin, B.F.; Sun, J.Z. Experiment of Vapor-Liquid Flow Visualization and Heat Transfer in Water Jacket of Cylinder Head of Internal Combustion Engine. Trans. CSICE 2015, 33, 466–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.L.; Dong, F.; Wu, Z.W. Simulation Study on Boiling Heat Transfer of the Water Jacket of Engine Cylinder Head. J. Yangzhou Univ. 2018, 21, 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, N.; Guo, Y.; Peng, C.H. A numerical simulation of single bubble growth in subcooled boiling water. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2019, 124, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.H.; Zhao, Y.H.; Xu, Z.X.; Hu, H.; Wang, J.; Ma, L. Simulation and Experimental Study on Boiling Heat Transfer in Engine Water Jacket. Chin. Intern. Combust. Engine Eng. 2018, 39, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, F.; Wang, Z.; Cao, T.; Ni, J. A novel interphase mass transfer model toward the VOF simulation of subcooled flow boiling. Numer. Heat Transf. Appl. 2019, 76, 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, S.Y.; Huang, R.H.; Zhou, P. Numerical investigation of two-phase flow characteristics of subcooled boiling in IC engine cooling passages using a new 3D two-fluid model. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2015, 90, 648–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourbakhsh, A.; Bayareh, M.; Mohammadi, A.; Jahantighi, S. Effect analysis on boiling heat transfer performance of an internal combustion engine at the shutdown time. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2018, 129, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.J.; Liu, J.M.; Wang, P.K.; Wang, L.F.; Huang, R.H. An Experimental Study for Simulating the Boiling Heat Transfer of Water-Jacket in the Cylinder Head of a Diesel Engine. Automot. Eng. 2018, 40, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, F.; Wu, H.J.; Cui, G.Q. Subcooled Boiling Model Based on VOF Two-Phase Flow Method and Experimental Verification on Cylinder Head. Trans. CSICE 2014, 32, 372–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, F.; Wu, H.J.; Cui, G.Q. Research on Subcooled Boiling Numerical Model of Cylinder Head Water-Jacket of Heavy Duty Diesel Engine. Chin. Intern. Combust. Engine Eng. 2014, 35, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, S.Y.; Huang, R.H.; Chen, L.; Yang, Z.H.; Wang, L.F. Experiment on Heat Transfer Characteristics of Subcooled Flow Boiling in a Water Jacket Simulated Channel of Diesel Engines. Trans. CSICE 2015, 33, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurul, N.; Podowski, M.Z. On the modeling of multidimensional effects in boiling channels. In Proceedings of the 27th National Heat Transfer Conference, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 28–31 July 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Lavieville, J.; Quemerais, E.; Mimouni, S.; Boucker, M.; Mechitoua, N. NEPTUNE CFD V1.0 Theory Manual; EDF: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Tolubinski, V.I.; Kostanchuk, D.M. Vapor bubbles growth rate and heat transfer intensity at subcooled water boiling. In Proceedings of the 4th International Heat Transfer Conference, Paris, France, 31 August–5 September 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.G.; Mao, H.P.; Su, T.X.; Wang, J.; Ying, H. Numerical Simulation Based Overall Discrete Method for Thermo-Fluid-Solid Coupling of Cylinder Head. Trans. Beijing Inst. Technol. 2016, 36, 563–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, F.; Hu, G.L.; Guo, C.H. Optimization of Cooling Water Jacket Structure Based on Thermal-Fluid-Solid Direction Coupling Method. Chin. Intern. Combust. Engine Eng. 2015, 36, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, G.X.; Fu, S.; Shi, X.; Bai, S. A New Single Phase Boiling Model for Heat Transfer Calculation of Cooling Water-Jacket in Cylinder Head. Trans. CSICE 2008, 26, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.R.; Li, G.X.; Hu, Y.P.; Fu, S.; Deng, K.Y. Design Criterion for Cylinder Head Water-Jacket Based on Boiling Heat Transfer Model. Chin. Intern. Combust. Engine Eng. 2014, 35, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.