Abstract

With the global population aging, managing fall risk among older adults has become a critical public health concern. Older adults attending adult daycare centers in South Korea are vulnerable due to poorer physical function and higher walking aid usage compared to community-dwelling counterparts. However, existing studies have primarily targeted community-dwelling older adults and rarely integrated both psychological and physical factors comprehensively. This study aimed to bridge these gaps and enhance fall prevention strategies. A study was conducted with 78 older adults (mean age = 83.24 ± 6.50 years; 82.1% female) from adult daycare centers. Physical assessments and structured interviews were conducted to measure strength, balance, and proprioception. Structured interviews collected demographic data and fear of falling. Significant differences in walking aid use, strength, balance, and proprioception were observed between participants with and without a history of falls (p < 0.05). Logistic regression analysis revealed that knee extension strength (OR = 0.893, 95% CI = 0.819–0.973) and longer timed up and go test times (OR = 1.098, 95% CI = 1.012–1.192) were significant predictors of falls. The combined model achieved an AUC of 0.83 (95% CI = 0.73–0.92), demonstrating good discriminative validity for fall prediction. Given the high fall risk in this population, targeted programs emphasizing lower-limb strengthening and mobility enhancement are essential to reduce fall incidence.

1. Introduction

With the acceleration of global population aging, the decline in physical function and fall risk management among older adults has become a major public health concern [1]. In South Korea, 62.4% of older adults are physically inactive [2], which is a key factor contributing to increased fall risk and the progression of frailty [3].

Along with these demographic changes, the utilization patterns of long-term care services among older adults have been shifting. There is a growing preference for community-based care over traditional nursing facilities, with adult daycare centers emerging as a key component of elderly care services. Over the past decade, the number of daycare center users has rapidly increased, currently exceeding 200,000 older adults in Korea, and establishing itself as a crucial form of care [4]. Many daycare center users receive long-term care insurance benefits because of difficulties in performing independent daily activities and are physically more vulnerable than community-dwelling older adults [5].

Physically vulnerable older adults are more likely to experience lateral or backward falls than forward falls [6], increasing the risk of serious injuries such as head trauma, spinal fractures, and hip fractures. Falls of this nature can lead to a decline in quality of life, increased mortality rates, and a significant financial burden on healthcare systems [7]. Therefore, implementing effective fall prevention strategies is essential, particularly for older adults attending adult daycare centers.

However, many existing cross-sectional studies on fall history have limitations, as they have primarily targeted community-dwelling older adults and thus fail to reflect the specific characteristics of elderly individuals in adult daycare centers, who typically exhibit higher use of walking aids and poorer physical function. Additionally, previous studies rarely integrated both psychological and physical factors comprehensively, limiting their ability to clearly identify variables with the greatest impact on fall risk in this specific population.

For example, Lee et al. (2018) examined the influence of psychological factors such as fear of falling and depression [8], along with demographic characteristics, but did not include physical performance measures. Meanwhile, Kitamura et al. (2023) analyzed gait and balance differences among adult daycare center users with and without a history of falls but did not consider psychological factors [9]. Similarly, Pellicer-García et al. (2020) investigated psychological (fear of falling and depression), demographic, and physical factors in community-dwelling older adults [10]; however, the study did not focus on adult daycare center users and did not assess key physical components such as lower limb strength and proprioception, which are crucial for balance and mobility.

Therefore, this study aimed to assess the association between fall experience and a comprehensive set of factors—including psychological factors, demographic characteristics, and physical performance measures—among older adults attending adult daycare centers. By integrating these variables, this study seeks to contribute to the development of practical fall prevention programs tailored to the adult daycare center environment and provide a foundation for evidence-based policy recommendations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

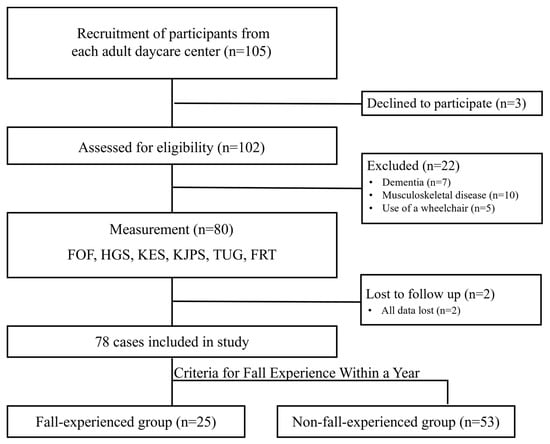

This cross-sectional study was conducted according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guideline [11]. The study involved older adults attending daycare centers where physical assessments and structured interviews were conducted. A total of 105 individuals were initially assessed for eligibility, and 27 were excluded owing to declining participate, dementia, musculoskeletal disease, wheelchair use, or missing data. Finally, 78 participants were included in the analysis. The participants were categorized into fall- and non-fall-experience groups based on their interview responses. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Sunmoon University (Approval No. SM-202409-022-2).

2.2. Data Collection

All data were collected from older adults at four adult daycare centers: two in Cheonan, and two in Asan, both in Chungcheongnam-do, South Korea. These centers were selected based on accessibility and their typical operation under the Korean long-term care insurance system. While not intended to be nationally representative, they reflect common service structures and functional characteristics of adult daycare centers in regional urban areas. Data collection took place between 16 October 2024, and 25 November 2024.

Individuals were required to meet the following inclusion criteria: (1) aged ≥ 65 years and registered under the Long-Term Care Insurance [5]; (2) capable of independent walking regardless of walking aid use; and (3) had normal cognitive function, defined as Mini-Mental State Examination-Korean version ≥ 24. Exclusion criteria were defined as follows: (1) individuals with neurological conditions associated with cognitive impairment (e.g., dementia or stroke); (2) individuals with musculoskeletal disorders accompanied by pain, with a visual analogue scale ≥ 3 on a 10-point scale; and (3) individuals with severe visual or hearing impairments that could interfere with study participation. All participants provided informed consent before participation.

2.3. Covariates and Measurements

The primary focus of this study was on physical function and performance, assessed through validated measurement tools. In addition, demographic and self-reported data were collected to account for potential covariates. Participants were categorized into fall-experienced and non-fall-experienced groups based on their self-reported history of falls within the past year.

The physical performance measures included handgrip strength (HGS), knee extension strength (KES), knee joint position sense (KJPS), the timed up and go (TUG) test, and the functional reach test (FRT). These measures were selected to comprehensively assess key domains related to fall risk, including overall muscle strength (HGS), lower-limb strength essential for postural control and sit-to-stand tasks (KES), proprioceptive function (KJPS), functional mobility (TUG), and dynamic balance (FRT). HGS was measured using a CAMRY dynamometer (Camry EH101, Sensun Weighing Apparatus Group Ltd., Zhongshan, China), which has demonstrated excellent reliability (ICC = 0.81–0.85) in elderly participants [12]. The participants stood in an anatomically neutral position with their arms fully extended and squeezed the dynamometer as hard as possible for 5 s. The procedure was repeated three times on the dominant hand, with a 15-s rest between trials, and the mean value was recorded.

KES was assessed using a hand-held dynamometer (Hoggan Health Industries Inc., MicroFET 2, Draper, UT, USA), which has shown excellent reliability (ICC = 0.81–0.98) [13,14]. The participants sat with their knees flexed at 90°, and the dynamometer was positioned just above the ankle. A make test was performed, during which the participants gradually exerted maximum force for 5 s. The highest value from three trials on the dominant leg was recorded, with 60-s rest intervals between trials, as peak force output is considered more representative of maximal lower-limb strength relevant to functional tasks such as gait and balance recovery.

KJPS was measured using a bubble inclinometer (Baseline Bubble Inclinometer; Fabrication Enterprises Inc., White Plains, NY, USA), which has demonstrated good reliability (ICC = 0.76–0.82) [15]. Participants passively moved to the target knee flexion angles (70°, 45°, and 20°), and were instructed to visually memorize each position before reproducing it with their eyes closed. The absolute errors between the target and reproduced angles were averaged across trials.

The TUG test was performed to evaluate balance and mobility, with a reported reliability of ICC = 0.87 [16]. Participants rose from a 46 cm high chair, walked 3 m, turned around, returned to the chair, and sat down. The time required to complete the task was measured using a stopwatch. Walking aids were permitted if required, and the researchers closely supervised the test for safety.

The FRT was used to assess dynamic balance (ICC = 0.83) [17]. Participants extended one arm forward at shoulder height and reached as far as possible without losing their balance. The distance reached was measured from the starting position to the ending position of the fingertips, and the maximum value from three trials was recorded.

In addition to physical assessments, structured interviews were conducted to collect covariates, including fall experiences within the past year, date of birth, sex, weight, height, number of underlying conditions, use of walking aids, exercise participation (≥1 time/week), and fear of falling.

The fall experience was determined through self-reported histories, where participants were asked whether they had experienced one or more falls in the past year. A “fall” was defined as an event in which a person unintentionally came to rest on the ground or at a lower level, excluding cases caused by external forces, such as being pushed [18].

Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height squared (m2), and participants were classified as obese if their BMI was ≥ 25 [19]. The number of underlying conditions was determined based on self-reported physician-diagnosed diseases, including hypertension, diabetes, cancer, pulmonary disease, heart disease, stroke, emotional or psychological problems, and arthritis [20]. The fear of falling was assessed using the Korean version of the Falls Efficacy Scale-International (FES-I), which consists of 16 items scored on a 4-point scale. Total scores range from 16 to 64, with lower scores indicating less fear. The FES-I demonstrates high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.971) [21]. Fear of falling was included as a psychological determinant that can influence mobility behavior, activity restriction, and balance confidence, thereby indirectly affecting fall risk.

2.4. Sample Size Calculation

The sample size was calculated based on the findings of Ikutomo et al. (2019) [22], where KES was identified as a significant predictor of fall risk in the elderly population. G*Power version 3.1.9.7 was used to perform the calculation, selecting z-tests as the test family and logistic regression as the statistical test. The type of power analysis was set to A priori: Compute required sample size—given α, power, and effect size. The parameters used in the analysis were as follows: Tails: Two (two-tailed test), odds ratio: 0.22 (derived from prior studies), Pr (Y = 1|X = 1) H0: 0.3 (assumed fall rate under the null hypothesis), significance level: 0.05, and power: 0.80. Using these parameters, the required total sample size was determined to be 31 participants. However, considering the vulnerable characteristics of elderly individuals in adult daycare centers and the anticipated high dropout rate during the study, the recruitment target was increased to a minimum of 62 participants to ensure sufficient statistical power and reliability of the results.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 26.0. Data were divided into fall- and non-fall-experienced groups for comparison. Categorical variables were analyzed using the chi-square test and expressed as counts (percentages). Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and compared using the independent t-test if they were normally distributed or as median (interquartile range, IQR) and compared using the Mann–Whitney U test if non-normally distributed.

Covariates and measurements were analyzed as independent variables, and fall experiences within the past year were used as the dependent variable. The independent variables included age, sex, BMI, obesity, the number of underlying conditions, the use of walking aids, exercise participation, HGS, KES, KJPS, TUG, FRT, and FES-I.

Binary logistic regression analysis was conducted using a forward selection method to identify significant predictors of falls. This method allows the systematic inclusion of variables based on their contributions to the model, ensuring that only the most relevant predictors are retained. Multicollinearity among independent variables was assessed using variance inflation factors (VIFs). The logistic regression model’s fit was assessed using the Hosmer–Lemeshow test to ensure adequacy. Model performance was further validated using Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve analysis to calculate the Area Under the Curve (AUC) for discriminative power.

3. Results

Participants were recruited from adult daycare centers (n = 105). Among them, 102 individuals were assessed for eligibility. After excluding 22 participants, measurements were conducted on 80 individuals. Because of missing data from two participants, the final analysis included 78 older adults (Figure 1). The mean age of participants was 83.24 ± 6.50 years, with 64 females (82.1%). The mean body mass index (BMI) was 24.15 ± 4.18 kg/m2, and 29 participants (37.2%) were classified as obese. The median number of underlying conditions was one. In total, 29 participants (37.2%) used walking aids, and only six participants (7.7%) exercised at least once per week.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram.

The mean HGS was 16.08 ± 6.09 kgf, and the mean KES was 16.26 ± 8.41 kgf. The mean KJPS absolute error was 6.96 ± 4.05°. The median TUG time was 13.14 s, and the median FRT distance was 12 cm. The median FES-I score, which reflects the degree of concern regarding falling, was 21.0 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients according to fall.

As shown in Table 1, significant differences were observed between the fall and non-fall groups in walking aid use (p = 0.004), HGS (p = 0.003), KES (p = 0.001), KJPS (p = 0.001), TUG (p = 0.006), and FES-I scores (p < 0.001).

In the univariate logistic regression analysis (Table 2), several physical and psychological factors were significantly associated with the likelihood of falls. The use of walking aids (OR = 4.35, p = 0.006), lower handgrip strength (OR = 0.88, p = 0.004), reduced knee extension strength (OR = 0.84, p = 0.001), larger knee joint position sense error (OR = 1.31, p = 0.002), slower TUG performance (OR = 1.12, p = 0.008), and higher FES-I scores (OR = 1.08, p = 0.005) were all identified as significant predictors of falls.

Table 2.

Univariate Logistic Regression for Variables Associated with Falls.

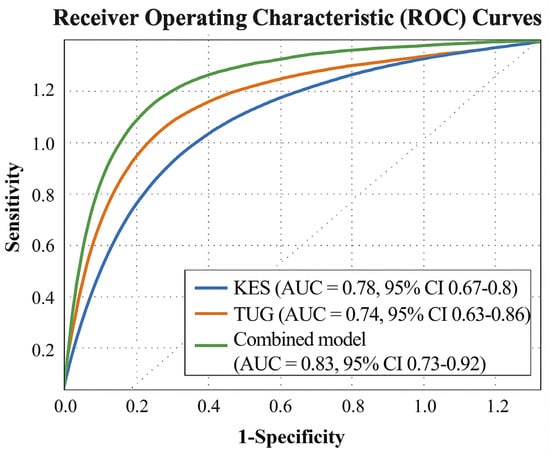

In the multivariate logistic regression model, only KES (OR = 0.893, 95% CI = 0.819–0.973, p = 0.01) and TUG (OR = 1.098, 95% CI = 1.012–1.192, p = 0.026) remained significant predictors (Table 3). All variance inflation factor (VIF) values were below 2.0, indicating no significant multicollinearity among the independent variables. The goodness-of-fit of the model was assessed using the Hosmer–Lemeshow test, which showed no significant results (p = 0.075), thereby confirming the adequacy of the model. Additionally, the model demonstrated a correct classification rate of 76.9%. ROC curve analysis showed good predictive ability (AUC = 0.83, 95% CI = 0.73–0.92; Figure 2).

Table 3.

Multivariate Logistic Regression Analysis for Fall Risk Prediction.

Figure 2.

Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves illustrating the discriminative ability of knee extension strength (KES), timed up-and-go (TUG), and their combined model for fall prediction. The combined model achieved an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.83 (95% CI = 0.73–0.92), demonstrating good discrimination between fallers and non-fallers with 81% sensitivity and 75% specificity at the optimal cut-off (Youden index).

4. Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the relationship between physical performance measures and falls among older adults. The results showed that 32.1% of older adults in adult daycare centers experienced falls, whereas previous nationwide data from community-dwelling older adults reported a substantially lower prevalence of falls [23].

To be admitted to an adult daycare center in South Korea, individuals must receive a long-term care certification issued by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, which is granted only to those requiring physical assistance. Consequently, older adults in daycare centers tend to have weaker physical function, which may explain the significantly higher fall incidence in this population. Supporting this, HGS—, a key indicator of overall physical strength—was measured at 16.08 ± 6.09 kgf among daycare center residents, whereas fall-experienced older adults in Go et al. (2021) [23] had an HGS of 24.81 ± 1.11 kgf, showing a difference in more than one-third. Previous research has demonstrated that decreased muscle strength increases fall risk [24], reinforcing the need for targeted interventions to improve physical function in vulnerable populations.

The results of this study indicate that individuals with a greater KES had a significantly lower fall incidence than those with a weaker KES. The KES plays a crucial role in supporting the lower body and maintaining balance during daily activities, such as walking and sit-to-stand movements [25,26]. Furthermore, the combined KES–TUG model (AUC = 0.83) demonstrated good discrimination in identifying high-risk individuals, emphasizing the complementary role of strength and mobility in fall prediction.

Falls often occur because of a sudden loss of balance, and a study by Ding and Yang (2016) reported that individuals with a stronger KES had a higher likelihood of recovering balance in fall-inducing situations [27]. Sufficient knee extensor strength may enable individuals to step forward or stabilize themselves during unexpected balance disturbances, thereby preventing falls.

Additionally, a study by Ikutomo et al. (2019) found that even in patients with hip joint osteoarthritis, a stronger KES was associated with a reduced fall risk, demonstrating a similar trend to the findings of this study [22]. This suggests that knee extensor strength is not merely a measure of muscle power but also a key factor in fall prevention and overall physical function maintenance.

The results of this study indicate that individuals with shorter TUG test performance times had a significantly lower fall incidence than those with longer TUG test times. The TUG test assesses mobility by measuring sit-to-stand transitions, walking, and directional changes, with shorter completion times indicating better mobility. Therefore, individuals with greater mobility are likely to have a lower risk of falls.

Previous studies have reported that individuals who have experienced falls tend to develop a greater fear of falling [28], and this study found that participants who experienced falls had higher fear of falling scores. According to Maki (1997), fear of falling alters gait patterns, leading to decreased stride velocity and increased stride width, which may contribute to prolonged TUG times [29]. Therefore, the FoF may have influenced the increased TUG times observed in participants with a history of falls.

Additionally, Soto-Varela et al. (2020) reported that TUG times exceeding 15 s were associated with an increased fall risk [30]. Given that the median TUG time of the fall-experienced group in this study was 16.79 s, these findings support the results of the present study.

In addition to KES and TUG, other variables such as HGS, KJPS, FES-I, and use of walking aids showed significant differences between the groups in the univariate analysis but were not retained in the final regression model. This suggests that, while these factors may contribute to fall risk, their impact might be mediated through lower limb strength and mobility. For instance, a weaker HGS may reflect overall frailty but does not directly predict falls. A previous study reported that, although improvements in lower limb strength were associated with a reduced fall risk, no significant changes were observed in handgrip strength, suggesting that HGS may have a relatively smaller impact on fall risk than lower limb strength [31]. Although the KJPS could influence balance, it may not be a sufficiently strong independent predictor [32]. Similarly, although the use of walking aids was more common in the fall-experienced group, this may indicate preexisting mobility limitations rather than serving as a direct risk factor for falls. Although fear of falling was significantly associated with falls in the univariate analysis, it did not remain significant in the multivariate model. This finding suggests that fear of falling may act as a mediator rather than an independent predictor of falls, as previous studies have reported associations between fear of falling and fall experience [33,34]. Specifically, fear of falling may influence fall risk indirectly by reducing mobility, altering gait patterns, or limiting physical activity, and high levels of fear of falling have also been observed in individuals without a history of falls [28], which may explain its loss of significance after adjustment for physical performance measures such as the TUG test. Given the frailty of the participants in this study, they may have been more vulnerable to fear of falling, regardless of their actual fall history.

This study analyzed fall risk from multiple perspectives by primarily assessing physical function while also incorporating psychological factors and demographic information. By considering these diverse aspects, our findings contribute to the development of fall prevention strategies that focus on physical function. Given the cross-sectional design of this study, the direction of the causal relationship between physical performance and falls cannot be determined. It is also plausible that falls may contribute to subsequent declines in muscle strength and mobility through mechanisms such as fear of falling, reduced physical activity, or immobilization, indicating a potential bidirectional relationship.

However, this study has several limitations. As a cross-sectional study, causal relationships between the examined factors and fall occurrence could not be established. Fall history was assessed through self-report, which may be subject to recall bias. In addition, participants were recruited exclusively from adult daycare centers, representing a relatively frail population, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to healthier community-dwelling older adults. Furthermore, potentially important factors such as medication use, vestibular disorders, previous orthopedic interventions, and detailed cognitive status were not included in the analysis. Additionally, the study was conducted in a limited geographic region and the sample was predominantly female, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to a broader population.

Future research should employ longitudinal cohort studies to explore fall risk from a more comprehensive perspective and integrate a wider range of psychological and physical variables to provide a more holistic understanding of fall prevention among older adults.

5. Conclusions

Older adults attending adult daycare centers showed a high prevalence of falls in the present study population. Falls can lead to injuries that significantly reduce quality of life, making prevention even more critical for this population.

This study found that weaker KES and longer TUG test times were associated with falls. Therefore, targeted lower-limb strengthening interventions, such as isometric knee extensor exercises and open- or closed-kinetic chain training, along with functional mobility exercises, should be incorporated into fall-prevention programs. In addition, the TUG test may be useful as a simple periodic screening tool for identifying individuals at high risk of falls in adult daycare settings.

Author Contributions

J.-S.O. was responsible for the statistics and writing. J.-S.K. conceptualized the research framework and provided the overarching research direction and guidance. S.-G.K. organized and executed the experiments. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Regional Innovation System & Education (RISE) program through the (Chungbuk Regional Innovation System & Education Center), funded by the Ministry of Education (MOE) and the (Chungcheongbuk-do), Republic of Korea (2025-RISE-11-004-02).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Sunmoon (SM-202409-022-2, 2 October 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Regional Innovation System & Education (RISE) program through the (Chungbuk Regional Innovation System & Education Center), funded by the Ministry of Education (MOE) and the (Chungcheongbuk-do), Republic of Korea (2025-RISE-11-004-02).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BMI | body mass index |

| HGS | handgrip strength |

| KES | knee extension strength |

| KJPS | knee joint position sense |

| TUG | timed up and go |

| FRT | functional reach test |

| FES-I | Falls Efficacy Scale—International |

References

- Gu, D.; Andreev, K.; Dupre, M.E. Major trends in population growth around the world. China CDC Wkly. 2021, 3, 604–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2020 National Survey on the Elderly: Final Report. Available online: https://www.mohw.go.kr/board.es?mid=a10411010100&bid=0019&act=view&list_no=366496 (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Fried, L.P.; Tangen, C.M.; Walston, J.; Newman, A.B.; Hirsch, C.; Gottdiener, J.; Seeman, T.; Tracy, R.; Kop, W.J.; Burke, G.; et al. Frailty in older adults: Evidence for a phenotype. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2001, 56, M146–M157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2023 Annual Statistical Report on Long-Term Care Insurance for the Elderly. Available online: https://www.suwonudc.co.kr/swjjc/base/board/read?boardManagementNo=38&boardNo=1530&page=1&searchCategory=&searchType=&searchWord=&menuLevel=3&menuNo=18 (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Seok, J.E. Public long-term care insurance for the elderly in korea: Design, characteristics, and tasks. Soc. Work Public Health 2010, 25, 185–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gratza, S.K.; Chocano-Bedoya, P.O.; Orav, E.J.; Fischbacher, M.; Freystätter, G.; Theiler, R.; Egli, A.; Kressig, R.W.; Kanis, J.A.; Bischoff-Ferrari, H.A. Influence of fall environment and fall direction on risk of injury among pre-frail and frail adults. Osteoporos. Int. 2019, 30, 2205–2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergland, A. Fall risk factors in community-dwelling elderly people. Nor. Epidemiol. 2012, 22, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Oh, E.; Hong, G.S. Comparison of factors associated with fear of falling between older adults with and without a fall history. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitamura, M.; Umeo, J.; Kurihara, K.; Yamato, T.; Nagasaki, T.; Mizota, K.; Kogo, H.; Tanaka, S.; Yoshizawa, T. Differences in improvement of physical function in older adults with long-term care insurance with and without falls: A retrospective cohort study. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellicer-García, B.; Antón-Solanas, I.; Ramón-Arbués, E.; García-Moyano, L.; Gea-Caballero, V.; Juárez-Vela, R. Risk of falling and associated factors in older adults with a previous history of falls. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P.; STROBE Initiative. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int. J. Surg. 2014, 12, 1495–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Liu, Y.; Lin, T.; Hou, L.; Song, Q.; Ge, N.; Yue, J. Reliability and validity of two hand dynamometers when used by community-dwelling adults aged over 50 years. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckinx, F.; Croisier, J.L.; Reginster, J.Y.; Dardenne, N.; Beaudart, C.; Slomian, J.; Leonard, S.; Bruyère, O. Reliability of muscle strength measures obtained with a hand-held dynamometer in an elderly population. Clin. Physiol. Funct. Imaging 2017, 37, 332–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grootswagers, P.; Vaes, A.M.M.; Hangelbroek, R.; Tieland, M.; van Loon, L.J.C.; de Groot, L.C.P.G.M. Relative validity and reliability of isometric lower extremity strength assessment in older adults by using a handheld dynamometer. Sports Health 2022, 14, 899–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baert, I.A.C.; Lluch, E.; Struyf, T.; Peeters, G.; Van Oosterwijck, S.; Tuynman, J.; Rufai, S.; Struyf, F. Inter- and intrarater reliability of two proprioception tests using clinical applicable measurement tools in subjects with and without knee osteoarthritis. Musculoskelet. Sci. Pract. 2018, 35, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nepal, G.M.; Basaula, M.; Sharma, S. Inter-rater reliability of timed up and go test in older adults measured by physiotherapist and caregivers. Eur. J. Physiother. 2020, 22, 325–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S.; Raimundo, A.; Marmeleira, J. Test-retest reliability of the functional reach test and the hand grip strength test in older adults using nursing home services. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2021, 190, 1625–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Global Report on Falls Prevention in Older Age. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241563536 (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Kanazawa, M.; Yoshiike, N.; Osaka, T.; Numba, Y.; Zimmet, P.; Inoue, S. Criteria and classification of obesity in japan and asia-oceania. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2002, 11, S732–S737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, R.; Clark, B.C.; Cesari, M.; Johnson, C.; Jurivich, D.A. Handgrip strength asymmetry is associated with future falls in older americans. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2021, 33, 2461–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Yang, J.; Chung, S. Risk factors associated with the fear of falling in community-living elderly people in korea: Role of psychological factors. Psychiatry Investig. 2017, 14, 894–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikutomo, H.; Nagai, K.; Tagomori, K.; Miura, N.; Nakagawa, N.; Masuhara, K. Incidence and risk factors for falls in women with end-stage hip osteoarthritis. J. Geriatr. Phys. Ther. 2019, 42, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Go, Y.J.; Lee, D.C.; Lee, H.J. Association between handgrip strength asymmetry and falls in elderly koreans: A nationwide population-based cross-sectional study. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2021, 96, 104470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, M.; Gu, M.O.; Yim, J. Comparison of walking, muscle strength, balance, and fear of falling between repeated fall group, one-time fall group, and nonfall group of the elderly receiving home care service. Asian Nurs. Res. 2017, 11, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fragala, M.S.; Alley, D.E.; Shardell, M.D.; Harris, T.B.; McLean, R.R.; Kiel, D.P.; Cawthon, P.M.; Dam, T.T.; Ferrucci, L.; Guralnik, J.M.; et al. Comparison of handgrip and leg extension strength in predicting slow gait speed in older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2016, 64, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarei, H.; Norasteh, A.A.; Koohboomi, M. The relationship between muscle strength and range of motion in lower extremity with balance and risk of falling in elderl. Phys. Treat. Specif. Phys. Ther. J. 2020, 10, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Yang, F. Muscle weakness is related to slip-initiated falls among community-dwelling older adults. J. Biomech. 2016, 49, 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, K.T.; Costa, D.F.; Santos, L.F.; Castro, D.P.; Bastone, A.C. Prevalência do medo de cair em uma população de idosos da comunidade e sua correlação com mobilidade, equilíbrio dinâmico, risco e histórico de quedas. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2009, 13, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maki, B.E. Gait changes in older adults: Predictors of falls or indicators of fear? J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1997, 45, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Varela, A.; Rossi-Izquierdo, M.; Del-Río-Valeiras, M.; Faraldo-García, A.; Vaamonde-Sánchez-Andrade, I.; Lirola-Delgado, A.; Santos-Pérez, S. Modified timed up and go test for tendency to fall and balance assessment in elderly patients with gait instability. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prata, M.G.; Scheicher, M.E. Effects of strength and balance training on the mobility, fear of falling and grip strength of elderly female fallers. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2015, 19, 646–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneshjoo, A.; Sadeghi, H.; Yaali, R.; Behm, D.G. Comparison of unilateral and bilateral strength ratio, strength, and knee proprioception in older male fallers and non-fallers. Exp. Gerontol. 2023, 175, 112161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malini, F.M.; Lourenço, R.A.; Lopes, C.S. Prevalence of fear of falling in older adults, and its associations with clinical, functional and psychosocial factors: The frailty in brazilian older people-rio de janeiro study. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2016, 16, 336–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyoda, H.; Hayashi, C.; Okano, T. Associations between physical function, falls, and the fear of falling among older adults participating in a community-based physical exercise program: A longitudinal multilevel modeling study. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2022, 102, 104752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.