1. Introduction

ITU-R (International Telecommunication Union Radio Communication Sector) IMT-2030 (International Mobile Telecommunications-2030) [

1] presents core scenarios for 6th Generation Mobile Communication (6G) services, as shown in

Figure 1, expanding to autonomous driving, smart cities, and healthcare, highlighting artificial intelligence (AI) convergence and ubiquitous connectivity. In this context, it emphasizes the importance of roaming by naming interoperability and interworking across heterogeneous networks and non-terrestrial networks (NTN) as key principles. Therefore, roaming is positioned not merely as a technical feature but as a critical requirement for ensuring both security and performance in the 6G era.

Meanwhile, the 3rd Generation Partnership Project (3GPP) 6G standardization roadmap moves from Release 20 to Release 21 and addresses migration and interworking with 5th Generation Mobile Communication (5G) systems [

2,

3]. However, the standardization discussions mainly focus on procedural and architectural aspects, leaving performance degradation and attack impacts in practical deployments underexplored. This study addresses this gap by providing empirical evidence that can inform both the standardization process and operator practices.

Although this work is positioned in the context of 6G roaming, the experimental evaluation is conducted on a 5G standalone (SA) roaming platform as a practical baseline, because 6G roaming protocols and implementations are not yet finalized. Therefore, the reported results should be interpreted as forward-looking evidence that informs early 6G roaming design and operational planning, rather than as measurements of a finalized 6G system.

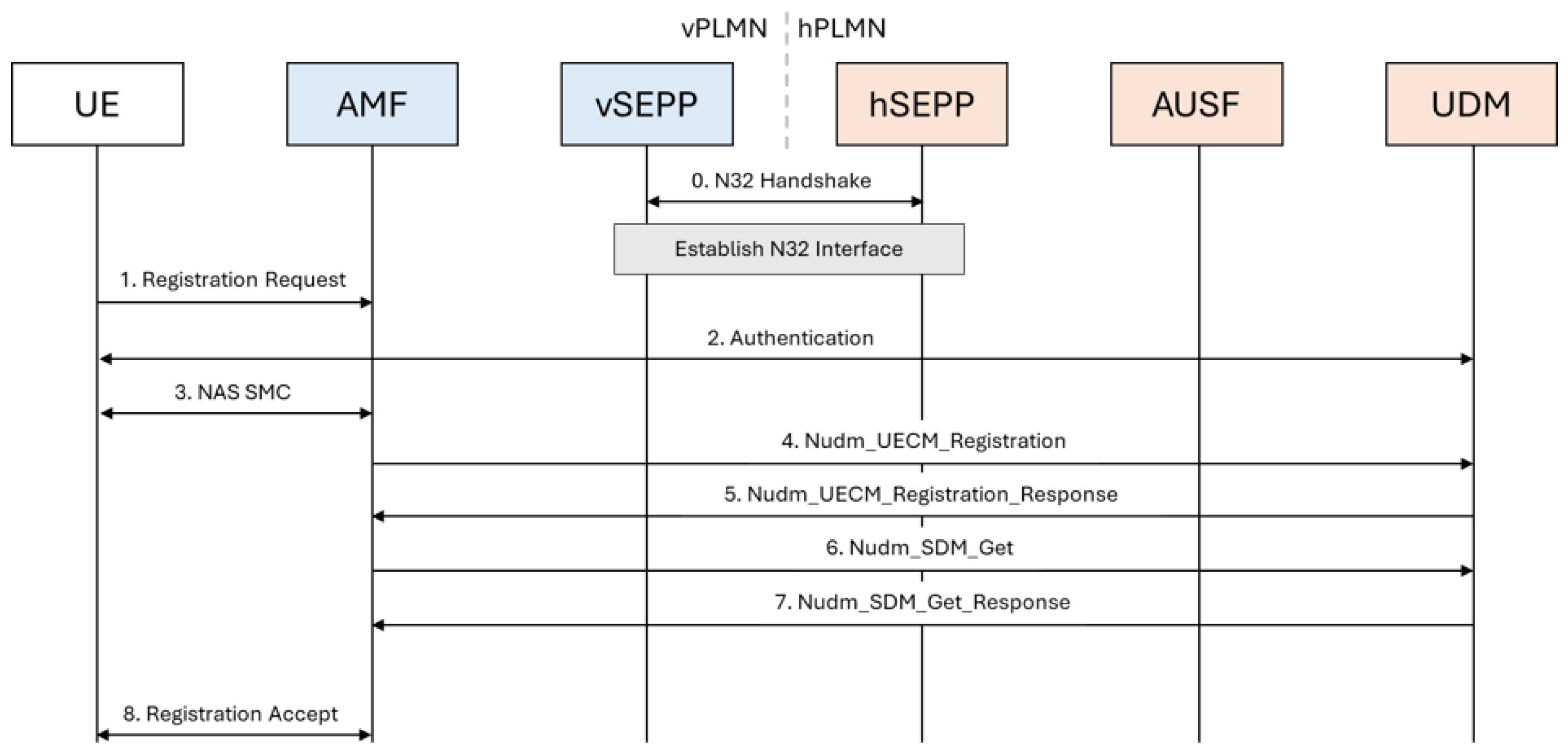

In global roaming procedures, packets traverse multiple national or operator domains. As the number of transit points increases, the attack surface broadens and transmission latency grows. 5G roaming provides security negotiation and message protection based on the Security Edge Protection Proxy (SEPP). In this process, additional latency and resource consumption are inevitable. Thus, roaming inherently entails a dual burden of degraded service quality and heightened security risk.

Recent studies have reported vulnerabilities related to subscriber identifiers, including attacks leveraging the Subscription Concealed Identifier (SUCI), such as SUCI-Catchers and fake base station based tracking [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8], indicating that SUCI security is not yet complete. In particular, the roaming setting enables unique attack vectors that are not feasible in non-roaming baseline. These include generating SUCI values at random to send non-existent subscriber information, and replaying previously used SUCIs to induce authentication failure. Such attacks place additional load on both the home public land mobile network (H-PLMN) and the visited public land mobile network (V-PLMN) and, depending on the attack type, can create bottlenecks at specific network functions (NFs).

To ensure seamless roaming services in the 6G era, a realistic, scenario-based experimental environment and quantitative analysis are essential. Although roaming studies have been reported previously [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13], practical operational aspects, such as separation of H-PLMN and V-PLMN environments, have not been sufficiently considered, limiting reproducibility and precise measurement. In particular, these studies generated signaling traffic internally within the core network without UE simulation, thereby assuming an internal attacker model and failing to reflect actual user flows; in contrast, our work incorporates UE-based scenarios to reproduce more realistic roaming procedures. Consequently, practical applicability and generalizability have also been constrained.

Accordingly, this study aims to build a realistic roaming environment and systematically analyze the performance overhead and security threats that arise during roaming. By measuring roaming cost and analyzing the impact of SUCI-based attacks, we report structural vulnerabilities and propose responses to the expanded attack surface, thereby offering insights into 6G roaming security. Unlike existing standardization efforts that emphasize procedural and architectural aspects, our empirical results shed light on operational issues that arise in practice, thereby bridging the gap between specification and deployment.

The contributions of this paper are as follows.

Construction of a realistic roaming testbed: By separating H-PLMN and V-PLMN, we enable reproducibility and fine-grained measurement that were lacking in prior work.

Definition and measurement of roaming cost: We execute the same procedures in non-roaming and roaming environments and analyze the roaming cost, which refers to additional resource consumption and latency introduced by SEPP-based procedures.

Reproduction and analysis of SUCI-based attacks: We reproduce SUCI random-generation and SUCI replay attacks, compare the load distribution between H-PLMN and V-PLMN, and identify the NFs at which bottlenecks occur in each network.

Guidance under an expanded attack surface: Considering the expanded attack surface in roaming, we propose broader detection and prediction strategies, providing insights for 6G roaming.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews the background of 5G roaming and two types of SUCI-based denial-of-service (DoS) attacks (random generation and replay).

Section 3 presents the experimental environment, threat model, and evaluation metrics.

Section 4 reports scenario-based experimental results and provides quantitative comparison and analysis.

Section 5 describes mitigation strategies, detection criteria, and discussion of the findings. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the paper and outlines future research directions.

3. Methodology

3.1. Experimental Environment

The experimental environment is summarized in

Table 1. We conducted experiments on a KVM/QEMU-based host equipped with an AMD Ryzen Threadripper PRO 5975WX 32-core processor and 256 GiB of memory. The host operating system was Debian GNU/Linux 12 with kernel version 6.8.4.

Three virtual machines were provisioned for the experiments. The first virtual machine acted as the UE and gNB, running PacketRusher on Ubuntu 24.04.1 LTS. It was allocated 8 vCPUs and 16 GiB of memory, and operated within the 10.10.1.0/24 subnet. The second virtual machine was configured as the V-PLMN and ran Open5GS 2.7.5. This VM was allocated 4 vCPUs and 8 GiB of memory, and connected to the 10.10.2.0/24 subnet. The third virtual machine served as the H-PLMN, also running Open5GS 2.7.5 on Ubuntu 24.04.1 LTS. It was allocated 8 vCPUs and 16 GiB of memory, and used the 10.10.3.0/24 subnet.

All three virtual machines were attached to the same Linux bridge, while distinct /24 subnets were assigned to ensure clear separation among PLMNs. All systems were synchronized via NTP, and no additional artificial latency or bandwidth constraints were imposed during the experiments.

3.2. Threat Model and Assumptions

The threat model of this study is premised on a roaming environment. A UE accesses the H-PLMN through a V-PLMN, and it is assumed that a roaming agreement between the two networks enables the registration procedure to be carried out normally; while the non-roaming environment is not part of the threat model itself, it is employed in the experiments as a baseline scenario for comparison.

The adversary is assumed to know the network identifiers (MCC/MNC) of both the H-PLMN and V-PLMN and to be aware that a roaming agreement exists between them. The adversary also understands the basic signaling flow of the initial registration procedure, in which a UE communicates with the gNB, the request is passed to the V-PLMN AMF, and subsequently forwarded to the AUSF and UDM in the H-PLMN. Furthermore, the adversary recognizes that the SUCI represents an encrypted subscriber identifier. Although it cannot be decrypted, the adversary is aware that it is used as an input to the registration procedure.

The adversary is capable of sending registration requests directly to the V-PLMN. It can generate random SUCIs and transmit them in large volumes, and it can observe other UEs’ registration requests over the V-PLMN radio interface. Based on this capability, the adversary can replay the observed SUCIs, thereby causing unnecessary resource consumption in the H-PLMN.

However, the adversary is not capable of breaking the underlying cryptographic algorithms (e.g., SUCI encryption, TLS key exchange), nor is it assumed to compromise NF instances within the H-PLMN or V-PLMN or gain operator-level privileges. The attacks considered in this study are strictly limited to exploiting the procedural handling of the protocol, rather than breaking its cryptographic foundations.

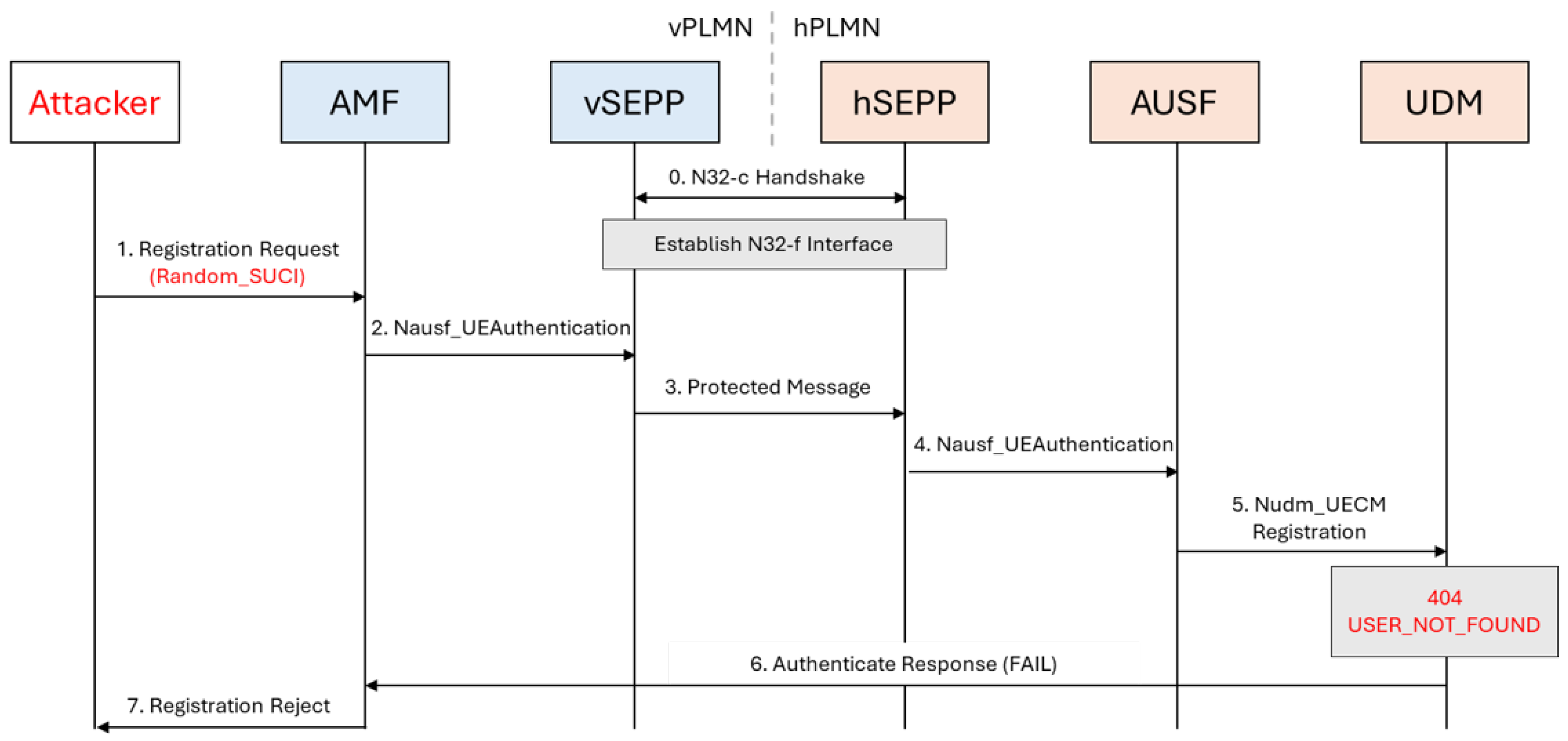

Figure 3 illustrates the random SUCI generation attack, in which syntactically valid but non-existent SUCIs are forged and forwarded to the home network. The processing chain leads to a lookup failure at the hUDM, resulting in a

404 USER_NOT_FOUND, but only after CPU and memory resources are consumed across the AUSF and UDM.

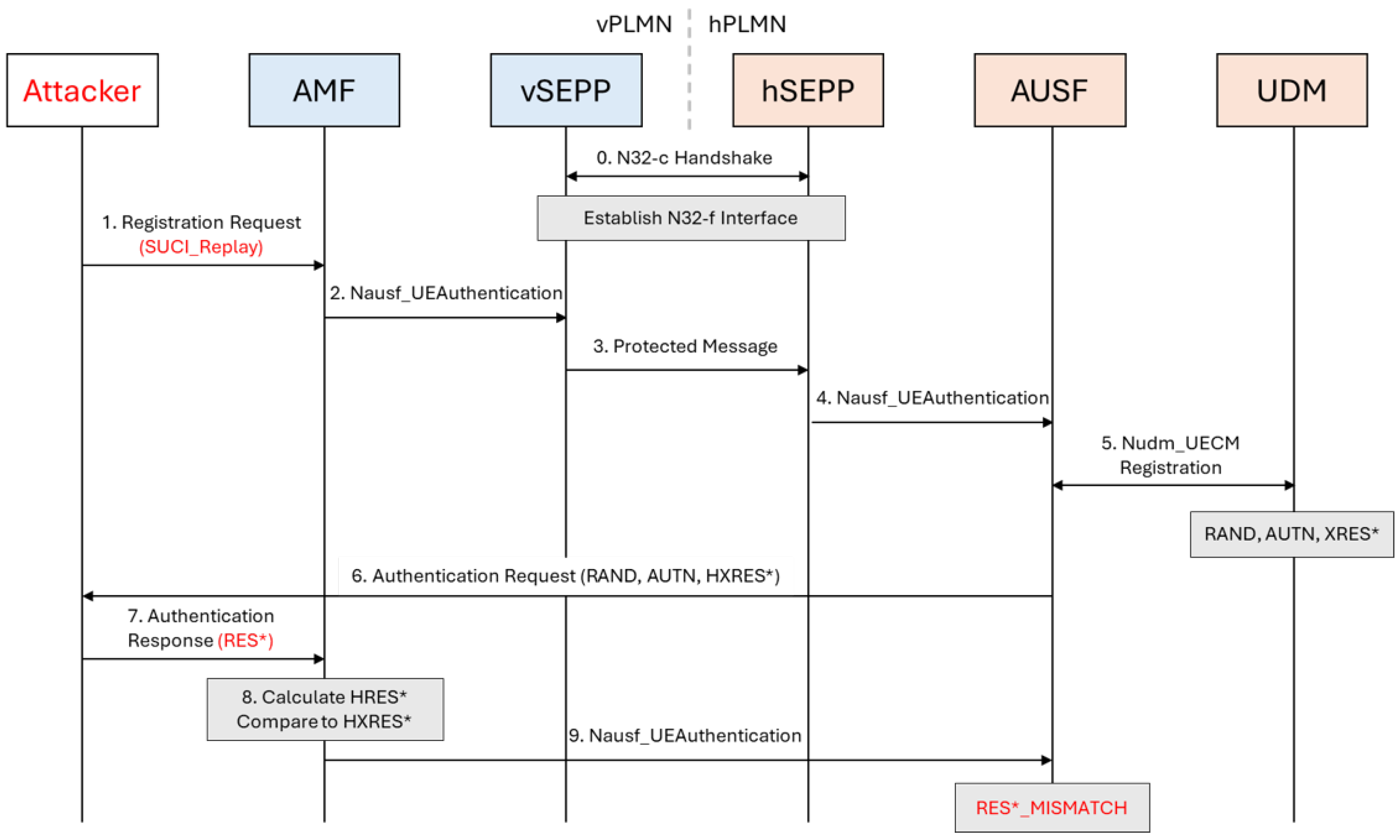

Figure 4 shows the SUCI replay attack, where previously observed legitimate SUCIs are replayed. Because the identifiers are valid in format and routing, the requests traverse deeper into the visited network’s processing path and trigger stateful authentication steps before ultimately failing with a

RES*_MISMATCH. These diagrams highlight how different SUCI-based attacks propagate through the roaming architecture and indicate the points where unnecessary resource consumption occurs.

Random SUCIs were synthetically generated by selecting valid MCC/MNC values corresponding to the target PLMN and applying the standard SUCI construction procedure defined in 3GPP TS 33.501 [

30]. The routing indicator was populated with valid but non-subscriber-specific values, and the SUCI was encrypted using the ECIES-based protection profile as specified in the 5G standard. Replay SUCIs were obtained through internal logging of previously generated SUCI messages within the testbed, rather than over-the-air capture. Although 5G-AKA provides replay protection mechanisms based on SQN and RES*, the evaluated SUCI replay attacks target pre-authentication signaling and therefore are not mitigated by these protections.

3.3. Workloads and Procedure

This study defines two workload modes. First, the burst mode increases the number of simultaneous registration attempts from 1000 to 5000 and continues until all requests are completed, to evaluate the impact of instantaneous concurrent load. Second, in the request per second (RPS) mode, the request rate starts at 25 and doubles step by step (25, 50, 100, 200, 400). Each workload proceeds until a total of 10,000 requests have been completed, thereby assessing the impact of sustained load. Every workload was repeated ten times, and the average values were used for analysis.

All experiments followed these two workload modes, namely burst and RPS. First, baseline data were collected from normal registration requests, which were conducted in both roaming and non-roaming environments to compare resource consumption and to establish the notion of roaming cost. Here, roaming cost is defined as the incremental overhead of roaming relative to the non-roaming baseline under the same workload, i.e., the additional CPU, memory, and (when reported) latency introduced by inter-PLMN signaling and roaming security mechanisms (e.g., SEPP/SCP processing and N32-related protection). Subsequently, two SUCI-based attack scenarios, random SUCI generation and SUCI replay, were carried out under the roaming environment, to observe deviations from the baseline and to analyze resource consumption and bottlenecks across NFs in both the H-PLMN and V-PLMN.

After each workload was completed, the virtual machines were rebooted to reset the system state before the next experiment. Measurements were taken according to the characteristics of each workload: in the burst mode, CPU and memory utilization were recorded every 0.1 s; meanwhile, in RPS mode, the same metrics were collected at 1 s intervals. Through this procedure, the study enabled quantitative comparisons of NF resource consumption and system response characteristics under different workloads.

3.4. Metrics and Validity

For the analysis of experimental results, this study defines resource consumption, latency, success rate, and error rate as the primary metrics. NF-level resource usage was measured in terms of CPU and memory utilization. In the non-roaming baseline, the monitored NFs included the AMF, SCP, AUSF, UDM, and UDR. In the roaming scenario, the measurements covered the vAMF, vSCP, and vSEPP in the V-PLMN, as well as the hAUSF, hUDM, hUDR, hSCP, and hSEPP in the H-PLMN, thereby enabling a clear distinction of resource usage distribution introduced by the roaming procedure.

End-to-end latency was measured from the perspective of the PacketRusher, defined as the elapsed time between the transmission of a registration request and the reception of a Registration Accept message. The success rate was calculated based on whether a Registration Accept message was received; meanwhile, timeouts, NAS retransmissions, and SCTP reconnections were recorded as error rates.

To ensure validity, each workload was executed ten times, and the average values were used in the analysis. After each workload, the virtual machines were rebooted to reset the system state and to prevent residual effects from influencing subsequent experiments. No artificial network delay or packet loss was introduced, and background load was minimized. The baseline was established using normal registration procedures in both roaming and non-roaming environments, allowing the definition of roaming cost and comparison with SUCI-based attack scenarios.

4. Experimental Evaluations

4.1. Gate Experiment and Valid Window

Before conducting roaming cost evaluation and scenario-based analysis, a gate experiment was performed to validate the effective workload ranges. The evaluation metric was defined as the error count observed during the registration procedure, and each experiment was repeated three times with the average values reported. Although CPU and memory utilization, as well as latency, are also important indicators, they are largely constrained by the maximum capacity of the allocated virtual resources. Hence, they were not used as the primary determinants for workload validity. Instead, error count was chosen as the most direct and reliable metric for this purpose.

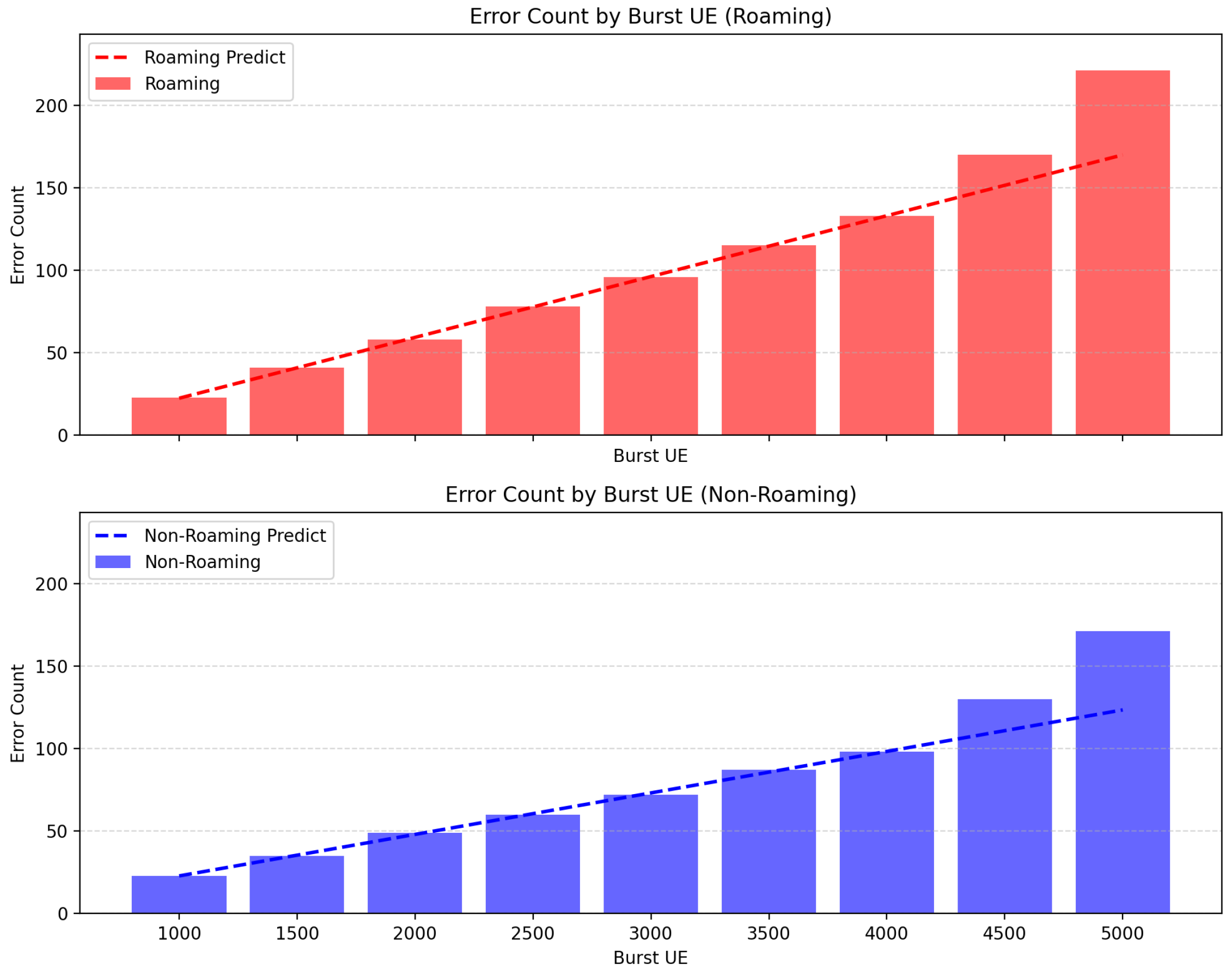

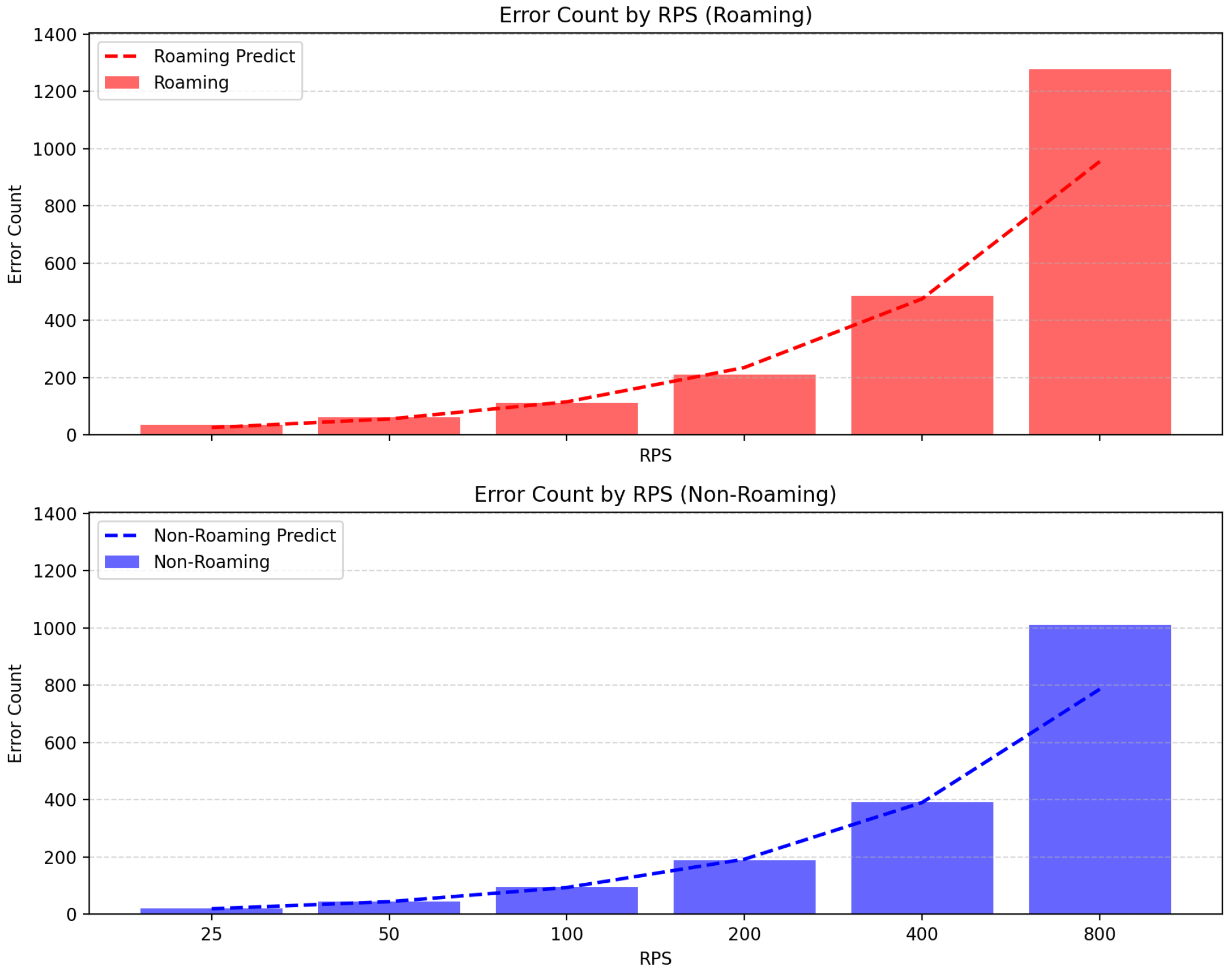

For the burst workload, error counts increased linearly within the range of 1000–4000 UEs, remaining within a predictable margin. Beyond 4500 UEs, however, error counts rose sharply, deviating from the linear approximation with more than a 20% prediction error. Therefore, the valid window for burst workload was defined as 1000–4000 UEs (

Figure 5).

For the RPS workload, error counts showed a near-linear increase across 25–400 RPS, with only minor deviations from the fitted line. At 800 RPS, however, the error rate exceeded 5% and the deviation from the linear prediction became significant, indicating the onset of instability. Accordingly, the valid window for RPS workload was set to 25–400 RPS (

Figure 6).

In summary, the burst workload illustrates the system’s tolerance to instantaneous concurrent load, while the RPS workload captures the effect of sustained request rates. These valid windows provide the basis for subsequent analysis in

Section 4.2,

Section 4.3 and

Section 4.4, ensuring that the evaluation is confined to meaningful and stable operating ranges.

4.2. Roaming Cost

In this study, roaming cost refers to the incremental overhead observed when roaming is enabled, measured as the difference between roaming and non-roaming baselines under identical workloads. This overhead captures additional CPU and memory utilization and the added processing/queuing latency caused by inter-PLMN signaling and roaming security functions (e.g., SEPP, SCP, and N32-related protection).

We primarily focus on CPU and memory because roaming-related control plane load and SUCI-based attacks manifest as resource exhaustion at core network functions, directly affecting availability and stability. CPU/memory utilization is also consistently measurable across deployments, making it a practical operator-relevant metric; latency is reported as a complementary indicator where appropriate.

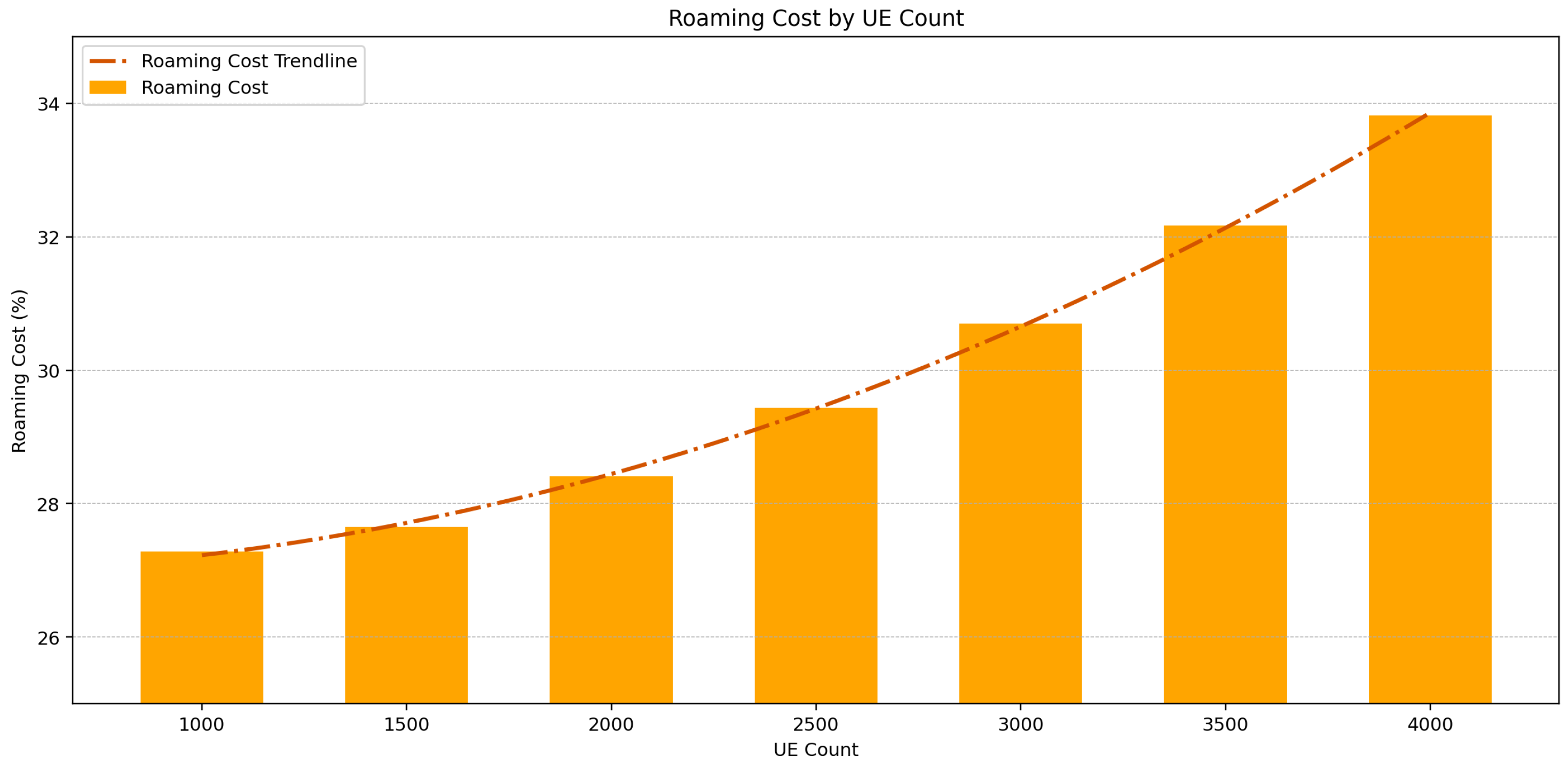

4.2.1. Burst Workload Results

In the burst mode experiment with 1000–4000 concurrent UEs, the bar chart in

Figure 7 shows that, even under identical registration procedures, the CPU usage is significantly higher in the roaming scenario than in the non-roaming baseline. This is because additional NFs in the H-PLMN, such as AUSF, UDM/UDR, and SEPP, are engaged, while the V-PLMN’s AMF also experiences additional memory overhead for context management.

Meanwhile, the cost graph in

Figure 8 does not merely compare values but quantifies the additional CPU burden attributable to roaming. The fitted cost function with UE count

u (scaled by 1000) is as follows:

indicating that the incremental resource consumption due to roaming grows non-linearly with the number of concurrent UEs.

The memory usage results are summarized in

Table 2. Roaming memory usage increases steadily with load, mainly due to the V-PLMN AMF overhead.

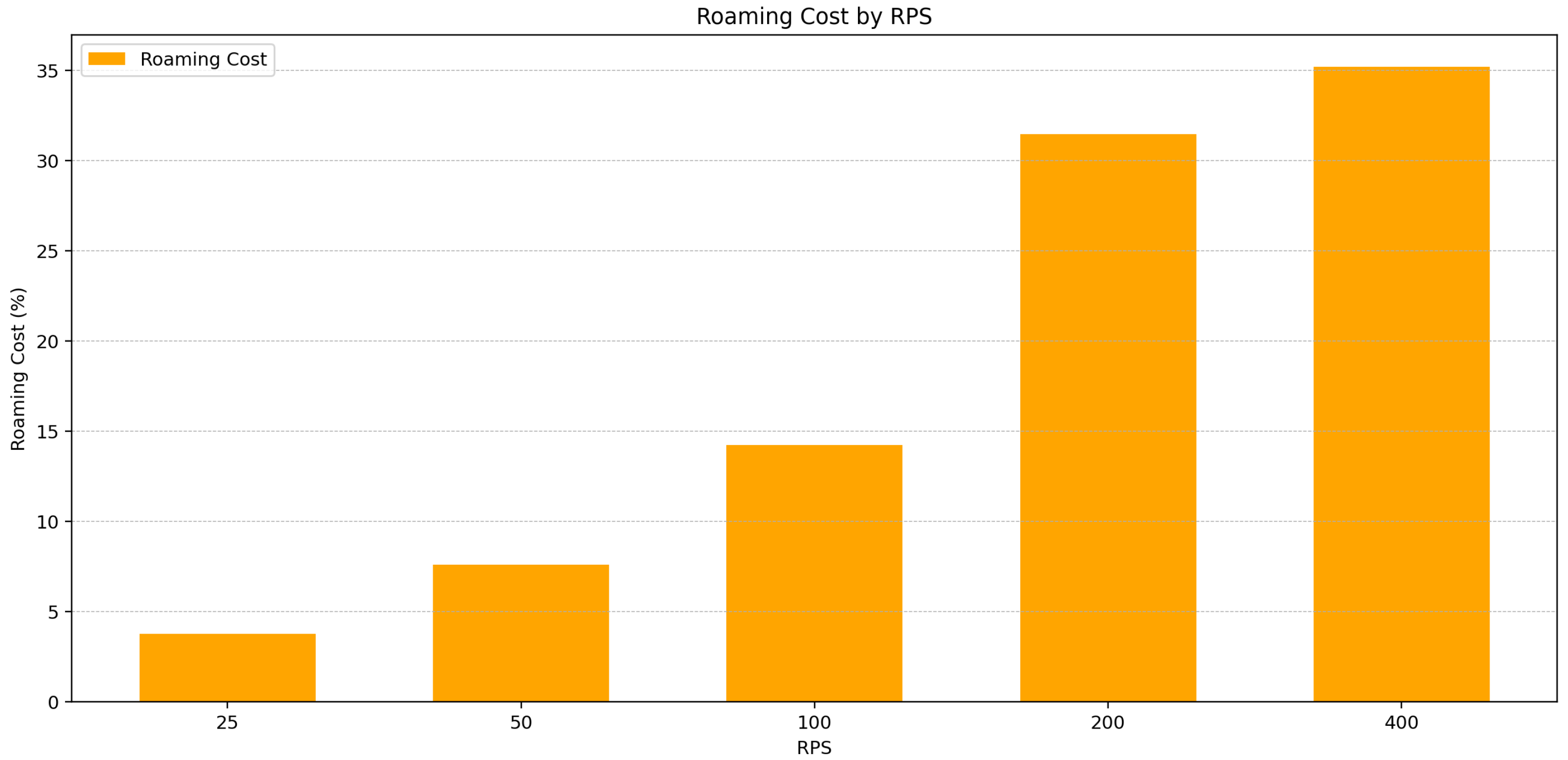

4.2.2. RPS

Workload Results

In the RPS mode, the request rate was increased from 25 up to 400 RPS with a total of 10,000 registration attempts. The bar chart in

Figure 9 shows that CPU usage in the roaming scenario grows more rapidly than in the non-roaming baseline. This is due to the continuous involvement of H-PLMN NFs (AUSF, UDM/UDR, SEPP, SCP) in processing each request.

The cost graph in

Figure 10 quantifies the additional CPU overhead caused by roaming. The fitted quadratic function with request rate

r (scaled by 100) is as follows:

showing that, beyond a certain RPS threshold, roaming introduces disproportionately high additional resource consumption.

Memory usage also shows consistently higher values in roaming than in non-roaming, though with a gentler growth rate. As in the burst case, most of the overhead originates from the V-PLMN AMF, which manages subscriber state.

Table 3 summarizes the results.

In summary, the bar charts highlight that the same registration procedure imposes higher CPU and memory loads in roaming scenarios, while the cost graphs generalize the incremental resource consumption through fitted functions. Together, These results emphasize the tangible overhead introduced by roaming procedures and provide a quantitative basis for defining “roaming cost” in terms of system resources.

4.3. Attack Scenario 1—Random SUCI Registration Request

The random SUCI registration request attack transmits non-existent subscriber identifiers to induce unnecessary processing in the core network. In this experiment, we emulate the case where randomly generated SUCIs are forwarded from the V-PLMN to the H-PLMN. The analysis focuses on burst workloads with 1000–4000 UEs and RPS workloads with 25–400 RPS, selecting the lower and upper bounds of the valid range (

Section 4.1) to represent relatively relaxed and saturated states. We report CPU utilization as the main metric, since memory variations were marginal and did not substantially affect interpretation.

4.3.1. Burst Workload Results

Table 4 shows CPU utilization when simultaneous registration requests are injected. At 1000 UEs, hAUSF increased from 2.61% to 6.49% (+3.88%p) and hUDM from 2.57% to 6.78% (+4.21%p). At 4000 UEs, hAUSF increased from 9.11% to 19.04% (+9.93%p) and hUDM from 9.32% to 30.78% (+21.46%p). These correspond to increases of 2.5–3.2 times relative to the normal case. Although V-PLMN functions such as AMF show larger absolute values, this is due to state maintenance overhead in normal procedures. The critical observation is that attack traffic systematically drives up H-PLMN authentication functions.

4.3.2. RPS Workload Results

Table 5 presents CPU utilization under sustained request rates. At 25 RPS, hAUSF grew from 0.52% to 1.36% (+0.84%p) and hUDM from 0.51% to 4.91% (+4.40%p). At 400 RPS, hAUSF jumped from 6.24% to 11.12% (+4.88%p) while hUDM surged from 6.93% to 37.27% (+30.34%p). In particular, hUDM consumed more than five times the CPU compared to the normal baseline, highlighting that sustained random SUCIs severely stress subscriber data management.

4.3.3. Interpretation

In

Table 4 and

Table 5, blue values denote decreases in CPU utilization, which occur because invalid SUCIs terminate registration prematurely and thus reduce V-PLMN load. Increases are distinguished by color: orange values highlight moderate but meaningful growth, whereas red values indicate sharp surges corresponding to NF bottlenecks. The random SUCI registration attack therefore constitutes an asymmetric DoS that disproportionately exhausts H-PLMN resources. Although V-PLMN functions maintain higher absolute load due to session handling, the attack specifically escalates CPU usage of AUSF and UDM by 2–5 times. This directly threatens registration latency and success rates of legitimate subscribers, undermining the availability of roaming services. In addition, the standard deviations reported in

Table 4 and

Table 5 remain relatively small across all workloads, indicating that the observed CPU utilization patterns are stable and consistently reproducible over repeated runs. This suggests that the increases in hAUSF and hUDM load under random SUCI attacks are not caused by transient fluctuations but reflect systematic stress introduced by the attack.

4.4. Attack Scenario 2: SUCI Replay Attack

In this section, we compare Attack Scenario 1 (random SUCI) and Attack Scenario 2 (replayed SUCI) to analyze the NF-level changes in workload. This comparison highlights the difference between invalid random inputs and validly formatted replayed identifiers, showing how the latter propagates deeper into the signaling path and results in broader resource consumption.

4.4.1. Burst Workload Results

Table 6 illustrates the key CPU utilization trends observed under burst workloads with 1000 and 4000 concurrent UEs for both Attack1 and Attack2. Across the V-PLMN, replay attacks (Attack2) consistently induce substantially higher CPU utilization at AMF, SCP, and SEPP than random SUCI flooding (Attack1). This reflects the fact that replayed identifiers traverse deeper into the roaming signaling chain, amplifying processing overheads at the visited network functions. On the H-PLMN side, AUSF exhibits a clear increase in CPU utilization under replay attacks, indicating repeated synchronization failure checks and concentrated authentication processing. This trend becomes more pronounced as the number of UEs increases, demonstrating that burst-scale replay attacks can rapidly escalate the authentication workload at the home network.

4.4.2. RPS Workload Results

Table 7 summarizes the CPU utilization trends under sustained request-rate workloads at 25 and 400 RPS. Similar to the burst scenario, replay attacks impose significantly higher overhead on V-PLMN network functions, particularly AMF, SCP, and SEPP, highlighting the impact of deeper signaling traversal under replayed SUCI identifiers. In the H-PLMN, AUSF shows a markedly steeper increase in CPU utilization under replay attacks as the request rate rises. Compared to burst workloads, the RPS scenario demonstrates that continuous replay traffic can deplete authentication resources more aggressively, underscoring the heightened risk posed by sustained attack patterns.

4.4.3. Interpretation

As highlighted by the key trends in

Table 6 and

Table 7, replay attacks consistently induce broader and more severe resource consumption than random SUCI flooding. V-PLMN network functions (AMF, SEPP, and SCP) experience higher CPU utilization under Attack2, as replayed identifiers propagate deeper into the roaming signaling path. On the H-PLMN side, AUSF exhibits the most pronounced sensitivity to replay attacks, with sustained RPS workloads causing sharper increases than burst scenarios. This indicates that continuous replay traffic can deplete authentication resources more effectively than short-lived bursts.

Overall, Attack1 primarily concentrates load on the H-PLMN authentication infrastructure, whereas Attack2 distributes the workload across both V-PLMN and H-PLMN. This distributed impact amplifies the overall stress on roaming operations and poses a greater threat to service stability. The consistently low standard deviation across repeated runs confirms that these trends are robust and reproducible, reinforcing the reliability of the comparative analysis.

5. Mitigation, Detection, and Discussion

5.1. Observed Resource Utilization Patterns

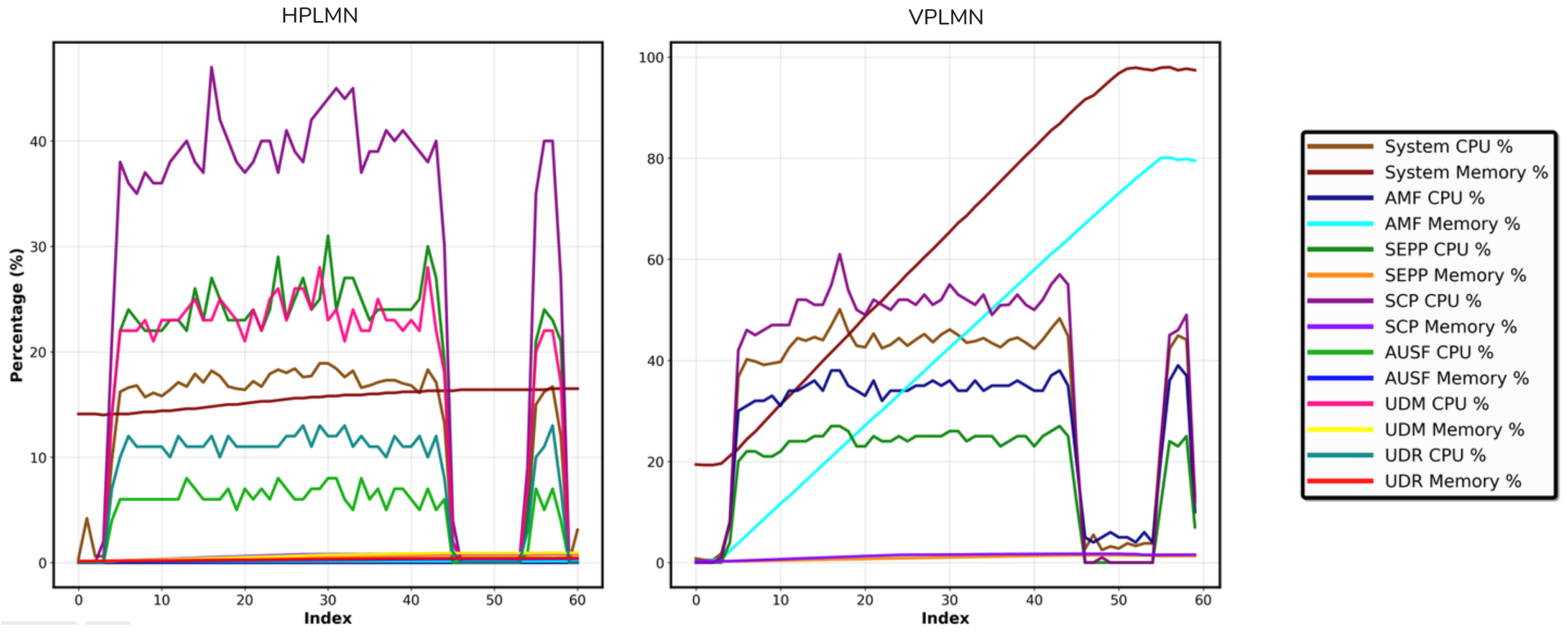

The time series analysis in

Figure 11 captures network function resource utilization across alternating scenarios of normal operation and RPS 100 DoS attacks in home and visiting 5G roaming networks. This experimental design intentionally mixes baseline conditions with attack periods to demonstrate the stark contrast in resource consumption patterns and validate detection thresholds. The temporal sequence shows: (1) initial baseline operation (before 08:29:00), (2) first DoS attack period (08:29:00–08:29:40), (3) return to normal operation (08:29:40–08:29:50), and (4) resumed attack scenario (after 08:29:50).

During baseline operation, resource utilization remains consistently low with CPU usage below 5% and memory consumption under 20% across all network functions. Upon attack initiation at 08:29:00, sudden spikes appear across multiple functions, with SCP experiencing the highest impact, reaching 40–60% CPU utilization in both networks. The home network demonstrates more comprehensive stress across additional functions including AUSF, UDM, and UDR, with sustained elevation in SCP and SEPP. Memory consumption patterns follow similar trends, with the home network reaching higher peak memory usage during attack periods.

The intentional return to normal operation around 08:29:40 is evidenced by the abrupt drop in all metrics back to baseline levels, demonstrating system recovery when attack traffic ceases. The subsequent spike at 08:29:50 represents a resumed attack scenario, again elevating resource consumption to attack-level patterns. This cyclical behavior validates that the observed resource exhaustion is directly attributable to the DoS attack rather than system instability. The visiting network shows particularly pronounced vulnerability with sharp resource spikes and more volatile consumption patterns during attack phases. System-level CPU consumption increases to 15–50% across both networks during attacks, with corresponding memory utilization rising significantly above baseline. The clear correlation between attack presence and resource stress, combined with rapid recovery during normal periods, provides robust indicators for anomaly detection systems with well-defined deviation thresholds distinguishing normal roaming operations from DoS attack conditions.

5.2. Mitigation Strategies

5.2.1. Rate Limiting

Rate limiting is a common network defense technique that restricts the number of requests or messages processed within a given time window, helping to prevent overload and DoS conditions. In 5G roaming, it is especially critical for protecting control plane entities against flooding attacks and malicious traffic bursts.

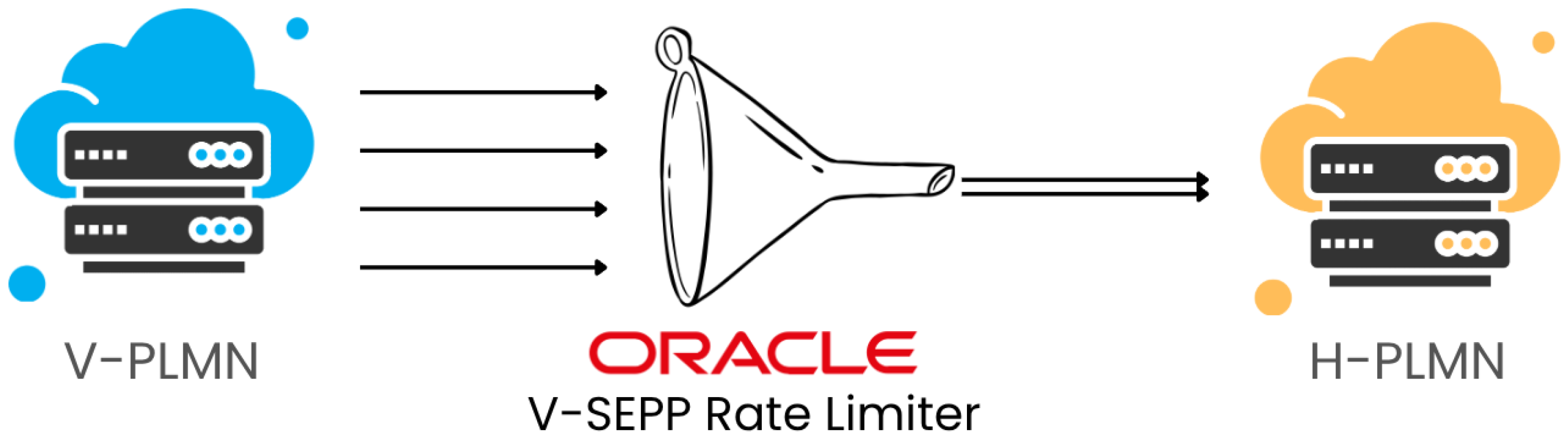

Figure 12 shows Oracle’s SEPP which integrates rate limiting as a core defense feature to secure inter-PLMN communication [

31]. The SEPP enforces configurable ingress and egress traffic thresholds, ensuring that only traffic within acceptable bounds is forwarded between operators. When limits are exceeded, the SEPP automatically blocks excessive requests and returns standardized error responses, thereby preventing abnormal signaling spikes from exhausting network resources. This mechanism provides operators with fine-grained control over roaming traffic while maintaining compliance with 3GPP standards, making it a practical first line of defense against volumetric signaling attacks in 5G core deployments.

5.2.2. Dynamic Network Function Scaling

Cloud-native design emphasizes building applications that fully leverage modern cloud environments, enabling flexibility, scalability, and resilience. Kubernetes, a leading container orchestration platform, automates the deployment, scaling, and management of containerized applications, allowing networks to adapt quickly to changing demands [

32]. In 5G roaming scenarios, Kubernetes enables both horizontal and vertical autoscaling of roaming-related core network functions (CNFs) such as SEPP, AUSF, UDM, and UDR, automatically adjusting resources based on monitored performance metrics like CPU, memory, and network throughput. This ensures that roaming services remain resilient and responsive, even under fluctuating inter-operator traffic conditions.

Beyond performance, Kubernetes-based scaling enhances robustness and security for roaming traffic. By dynamically adding instances or allocating additional resources to critical functions, the system can absorb sudden traffic spikes, including potential DoS [

33] attacks targeting roaming interfaces, reducing the risk of service degradation. Combined with monitoring and automated scaling policies, this approach allows operators to maintain high availability and consistent service quality for subscribers traveling across different networks.

5.2.3. Blockchain

The 5GSBA protocol (“Secure Blockchain-based Authentication and Key Agreement for 3GPP 5G Networks”) proposes decentralizing parts of the authentication function across base stations via a blockchain ledger to eliminate the single point of failure in the centralized UDM entity [

34]. By employing one-time secret hash functions, SUCI encryption, and replacing sequence number linkability with ECDH, the design counters replay attacks, linkability attacks, and crucially DoS and Distributed DoS (DDoS) threats.

5.3. Proof-of-Concept: Rate Limiter

5.3.1. Technical Setup

The proof-of-concept implements a rate-limiter for the SEPP in a realistic 5G roaming scenario emulation inside a cloud environment. The experimental environment consists of the technical components and technologies shown in

Table 8.

5.3.2. Rate Limiter Implementation

The rate limiter is deployed as an NGINX reverse proxy positioned in front of the SEPP N32-f service. This architecture emulates industry-grade rate limiting solutions such as Oracle SEPP’s rate limiter. The rate limiting policy is implemented using NGINX’s

limit_req and

limit_conn modules, which regulate request rates and concurrent connections at the inter-PLMN boundary. The complete NGINX configuration is provided in

Appendix A. In our deployment, the configuration enforces a base rate of 100 requests per second per IP address, with a burst capacity of 200 requests to accommodate legitimate traffic spikes. Connection limits are set to 50 concurrent connections per IP, preventing connection exhaustion attacks.

5.3.3. Attack Scenarios and Results

Three experimental scenarios were evaluated to assess the rate limiter’s effectiveness:

No rate limit (Apache Bench): Baseline measurement with direct SEPP access

Rate-limited (Apache Bench): NGINX rate limiter protecting against Apache Bench attack

Rate-limited (WRK): NGINX rate limiter defending against high-performance WRK attack

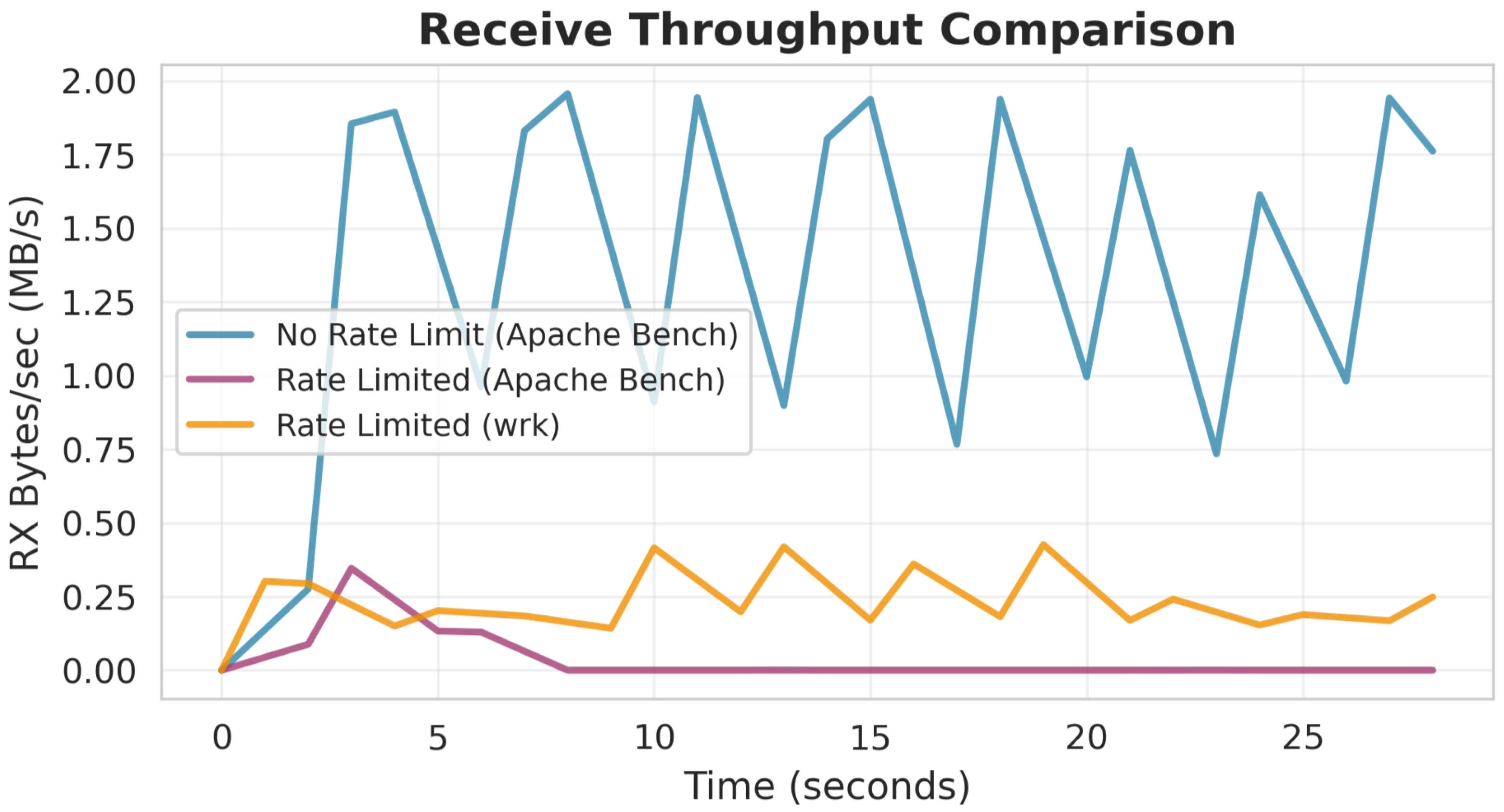

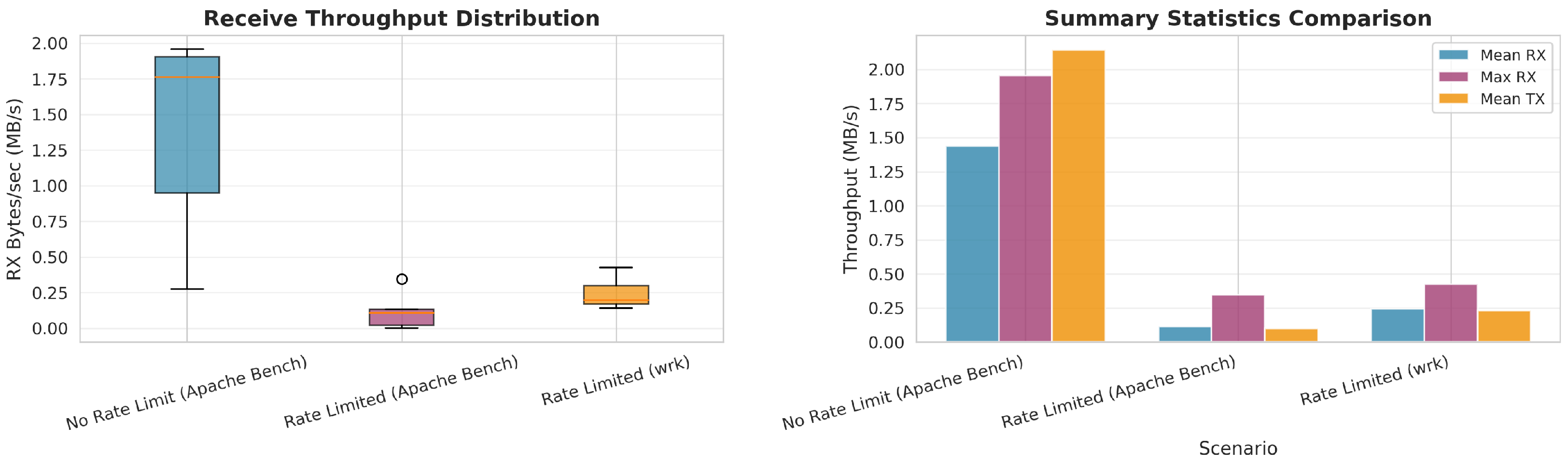

To ensure grayscale readability,

Figure 13 and

Figure 14 should be interpreted based on the scenario labels and throughput magnitude rather than color. In

Figure 13, the no-rate-limit baseline exhibits the highest throughput, whereas both rate-limited cases remain substantially lower (with WRK slightly higher than Apache Bench under the same policy).

Figure 14 summarizes these differences via throughput distributions and summary statistics, providing a monochrome-safe comparison across scenarios.

5.3.4. Analysis and Insights

The experimental results demonstrate the rate limiter’s effectiveness in mitigating DDoS attacks on the N32-f interface:

Throughput reduction: Without rate limiting, the Apache Bench attack achieved a mean receive throughput of 1.44 MB/s with peaks at 1.96 MB/s. With rate limiting enabled, this was reduced to 0.12 MB/s (92% reduction) for Apache Bench and 0.24 MB/s (83% reduction) for WRK attacks.

Packet rate control: Receive packet rates were suppressed from a mean of 958 packets/s (peak: 1303) to 115 packets/s for Apache Bench attacks and 161 packets/sec for WRK attacks when rate limiting was active.

Attack pattern differences: The WRK attack tool demonstrated approximately 2× higher throughput compared to Apache Bench under rate limiting conditions, indicating its more sophisticated request generation capabilities. However, both attack vectors were effectively constrained below harmful levels.

Traffic stability: The time series analysis reveals that rate limiting produces stable, controlled throughput patterns, eliminating the volatile spikes characteristic of unprotected services. This stability is crucial for maintaining Quality of Service (QoS) for legitimate roaming traffic.

Resource protection: By limiting concurrent connections and request rates per IP, the rate limiter prevents resource exhaustion at the SEPP level, ensuring availability for legitimate inter-operator signaling.

This proof-of-concept validates that rate limiting provides effective protection for 5G roaming interfaces against common HTTP flood attacks, demonstrating behavior comparable to commercial-grade SEPP rate limiters. The solution successfully maintains system stability and resource availability even under sustained attack conditions.

5.4. Proof-of-Concept Anomaly Detection Implementation

Anomaly detection in network security encompasses several methodological approaches, including specification-based detection (rule-based thresholds), statistical methods such as z-score and percentile-based detection [

35], distance-based techniques such as k-Nearest Neighbors (k-NN) and Local Outlier Factor (LOF) [

36], and machine learning approaches including One-Class Support Vector Machine (One-Class SVM), Isolation Forest [

37], autoencoders, and ensemble methods [

38]. Each approach presents distinct trade-offs in computational complexity, interpretability, and detection performance.

To demonstrate the practical applicability of our experimental findings, we develop a proof-of-concept anomaly detection framework using the resource utilization data collected from our roaming security experiments. The dataset comprises performance metrics from both normal operations and SUCI-based attack scenarios, enabling the detection of malicious roaming traffic patterns from NF-level resource signals.

5.4.1. Model Comparisons

Recent studies have evaluated a range of anomaly detection methods, including Isolation Forest, One-Class SVM, autoencoders, and ensemble approaches, across widely used network intrusion datasets. These works provide methodological baselines and empirical evidence that inform our model selection. A consolidated comparison of representative studies is provided in

Appendix B. Overall, this body of evidence indicates that Isolation Forest and One-Class SVM remain competitive unsupervised baselines across diverse network datasets, while autoencoder-based approaches often achieve superior performance in complex or zero-day attack scenarios.

5.4.2. Detection Framework

For our proof-of-concept, we select Isolation Forest due to several advantages supported by recent research. First, Isolation Forest demonstrates favorable scalability with

O(n log n) time complexity and low memory requirements, making it well-suited for high-volume monitoring [

37]. Second, recent advances such as Extended Isolation Forest (EIF) address the curse of dimensionality by using hyperplane-based splitting rather than axis-parallel cuts, improving performance in high-dimensional feature spaces [

39]. Third, Isolation Forest makes no strong assumptions about data distribution and can perform well when trained only on normal data without labeled anomalies [

40]. Unlike density-based methods that often degrade under high dimensionality [

37,

41], Isolation Forest is based on anomaly isolation rather than explicit profiling of normal behavior. The mathematical formulation of the Isolation Forest anomaly score and its associated parameters are provided in

Appendix C.1.

Our implementation employs an Isolation Forest with 300 trees using automatic sample sizing (50% of the training data per tree) and a contamination threshold of 8%. The model is trained exclusively on baseline (normal operation) data to establish normal behavior boundaries. The contamination parameter controls the strictness of the decision boundary and represents the proportion of the decision space flagged as anomalous, rather than the actual percentage of attacks in the dataset. A value of 8% provides a practical balance between precision and false alarms for production-style 5G monitoring. In addition, dynamic threshold optimization is applied to maximize the F1 score within a target recall range, supporting stable performance across varying operating conditions.

5.4.3. Feature Selection and Data Sources

Our feature selection targets CPU and memory utilization metrics collected from the host system and six critical 5G network functions (AMF, SEPP, SCP, AUSF, UDM, and UDR). These metrics are selected due to their direct correlation with attack-induced performance degradation and their universal availability in practical 5G deployments. The feature vector combines raw metrics with temporal statistics to capture both instantaneous and short-term behavioral patterns. The formal definition of the feature vector is provided in

Appendix C.2.

Specifically, the model uses 14 raw CPU and memory metrics. Each raw metric is augmented with temporal statistics computed over a 30 s rolling window, including the mean, standard deviation, and maximum. This yields a total of 56 features, enabling detection of both abrupt spikes and gradually evolving resource-consumption patterns. All features are standardized using z-score normalization. Missing metrics are zero-filled to ensure consistent dimensionality across heterogeneous configurations. This design supports real-time deployment by balancing descriptive power and computational efficiency.

Figure 15 illustrates the distribution of the first two scaled features. To ensure grayscale readability, the figure should be interpreted using the legend-defined class labels (normal operation vs. SUCI-based DoS) rather than relying on color cues. The visualization shows distinguishable clustering tendencies between normal operation samples and attack samples, while also exhibiting partial overlap consistent with realistic operational conditions.

5.4.4. Evaluation Methodology

Our evaluation assesses the Isolation Forest model for 5G roaming attack detection using standard classification metrics and synthetic data augmentation to emulate deployment variability. The original dataset comprises 444 normal operation samples (baseline scenarios) and 121 attack samples RPS 100 scenarios representing high-rate DoS conditions), totaling 565 samples. From these samples, we extract 56 engineered features derived from CPU and memory utilization signals captured from the host system and key 5G network functions (AMF, SEPP, SCP, AUSF, UDM, and UDR). To improve robustness, we augment the dataset to include varying attack difficulty levels, gradual transitions, partial attacks, and realistic noise patterns. The model is trained exclusively on normal operation data and evaluated on both the original and augmented datasets. We report detection capability, false positive behavior, and generalization tendencies across different attack conditions. This proof-of-concept focuses on a single model family and a single high-rate scenario. A production-grade deployment would benefit from k-fold cross-validation, broader empirical comparisons (e.g., One-Class SVM and autoencoders), and evaluation across multiple attack intensities. These limitations are discussed further in

Section 5.6. Performance metrics are computed as follows: precision is

, recall is

, and F1 score is

, where

,

, and

denote true positives, false positives, and false negatives, respectively.

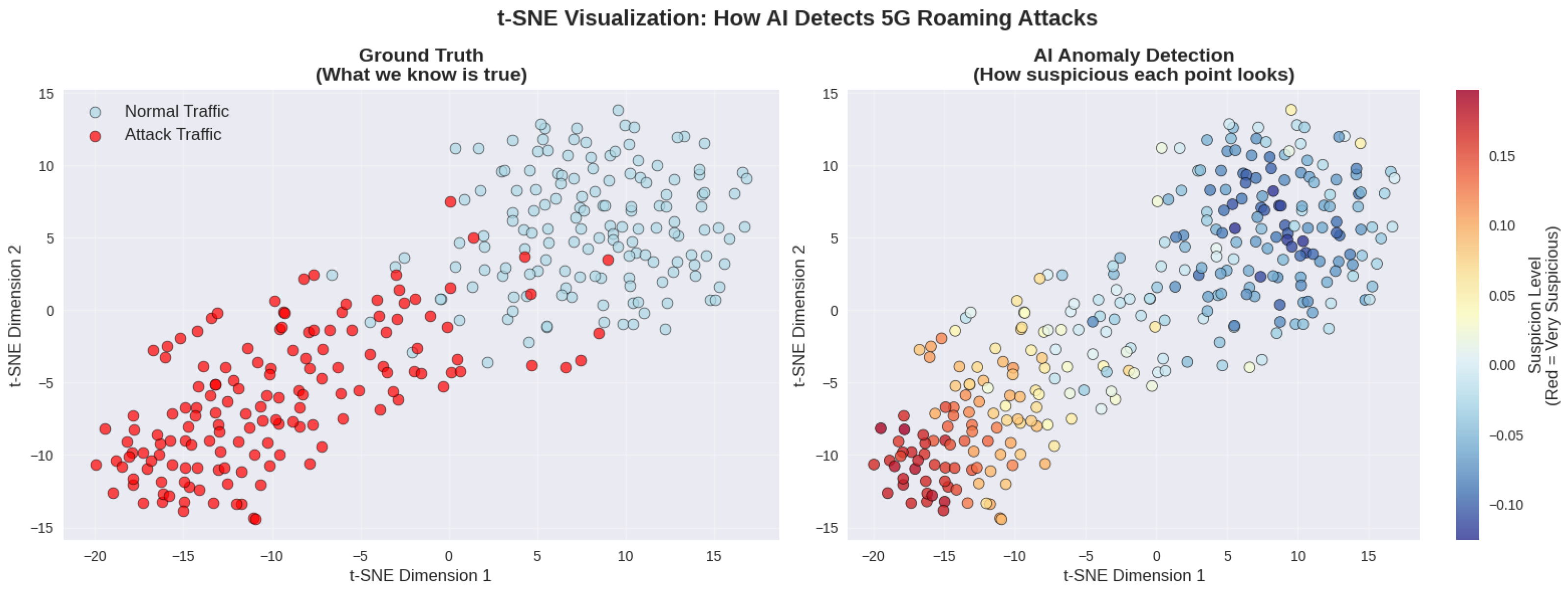

Table 9 shows 92.1% precision, indicating a low false-alarm tendency when an attack is flagged. The recall of 85.3% confirms that most attack instances are detected. The resulting F1 score (88.6%) summarizes a balanced trade-off between precision and recall. Overall, these results suggest that the proof-of-concept can detect high-rate roaming DoS conditions with modest false positives.

Figure 16 provides a low-dimensional view of the separation learned between normal operation and attack samples. For grayscale viewing, the separation should be interpreted based on the legend and the relative structure of the projected clusters, not on color intensity alone. Attack samples are assigned consistently higher anomaly scores than normal operation samples in the projected space, supporting the feasibility of resource-metric-based detection for roaming control plane attacks. In operational settings, threshold calibration and additional validation can further control false positives while maintaining sensitivity.

5.4.5. Operator Decision Framework: Balancing Security, Performance, and Cost Trade-Offs

Because operator objectives and infrastructure models vary (e.g., cost efficiency, ultra-low latency services, or hosted/shared deployments), no single roaming mitigation or detection strategy fits all cases. To improve readability and keep the main text focused on key experimental findings, the operator-oriented decision matrix, suggested decision steps, and illustrative scenarios are provided in

Appendix D.

5.5. Key Findings and Implications

The construction of a realistic roaming testbed improved reproducibility and measurement precision compared to prior studies. By separating the H-PLMN and V-PLMN, the environment more faithfully reproduces inter-operator roaming procedures. This design also enables fine-grained NF-level performance measurement under controlled workloads.

By defining and measuring roaming cost, this study quantifies the performance gap between roaming and non-roaming environments. The introduction of intermediary functions such as SEPP and SCP increases CPU and memory utilization and adds latency. These results confirm that roaming introduces measurable performance overhead in practical deployments.

Our analysis of SUCI-based attacks reveals distinct resource-consumption patterns depending on attack type. Random SUCI generation concentrates load on the AUSF in the H-PLMN. In contrast, replay attacks follow a flow closer to normal procedures and distribute load across both the V-PLMN and H-PLMN. In both cases, AUSF emerges as a bottleneck under elevated signaling load.

These findings highlight the expanded attack surface and the need for countermeasures beyond a single-operator boundary. Because roaming interconnects multiple NFs across PLMNs, defenses confined to one domain are insufficient. A multi-layered security approach supported by inter-operator coordination is required. In particular, AI-based anomaly detection and dynamic NF scaling can strengthen resilience in future 6G roaming security frameworks.

5.6. Limitations

This study primarily focused on CPU and memory usage to reveal resource-consumption patterns. However, it does not sufficiently address additional performance metrics such as latency, registration success rate, or QoS indicators (e.g., packet loss and throughput). As a result, the characterization of roaming cost remains limited to resource-centric indicators.

In real-world international roaming, round-trip time (RTT) is typically higher due to long inter-operator paths and gateway traversal. Our experimental setup uses a single-host virtualized environment and therefore cannot reflect these RTT characteristics. Accordingly, the measured latency impact and the derived attack severity may underestimate effects in geographically distributed deployments.

The scope of attacks is confined to two SUCI-based DoS types (random generation and replay). Other realistic threats, such as SUCI catcher exposure, fake base station disruptions, downgrade attacks, or session-exhaustion attacks, were not evaluated in this study.

The proof-of-concept anomaly detection implementation also has methodological limitations:

Dataset scale: The dataset size (565 samples: 444 normal, 121 attack) is relatively small compared to the 56-dimensional feature space. This raises concerns about overfitting and generalization. Larger-scale validation using data collected from production environments would strengthen robustness.

Attack intensity coverage: The evaluation focuses on an RPS 100 scenario and does not capture the full spectrum of intensities (e.g., stealthy low-rate attacks or variable-rate attacks). Future work should evaluate multiple rates (e.g., RPS 50, 200, 500) to assess sensitivity and establish rate-dependent thresholds.

Algorithmic comparisons: While we justify Isolation Forest via comparative literature analysis (

Appendix B), we do not provide direct empirical comparisons with alternatives (e.g., One-Class SVM and autoencoders) on our dataset. Comparative experiments with cross-validation would strengthen evidence for model selection.

Deployment variability: The model is trained on data from a controlled testbed. Real networks exhibit greater variability in traffic patterns, hardware configurations, and baseline utilization, which may affect detection accuracy and false positive rates.

Despite these limitations, the proof-of-concept demonstrates the feasibility of unsupervised anomaly detection for roaming security monitoring using NF-level resource metrics. The results provide a foundation for more comprehensive, production-grade implementations and evaluations.

6. Conclusions

This study experimentally verified SUCI-based DoS threats that may arise in 6G roaming environments and presented the resulting performance degradation and security implications. The contributions can be summarized in four aspects:

Establishing a realistic roaming testbed that ensures reproducibility and precision in experiments.

Defining and quantitatively measuring roaming cost to identify performance degradation factors inherent to roaming compared to non-roaming environments.

Reproducing and analyzing SUCI-based attacks to reveal resource consumption patterns at the NF level and highlight the structural vulnerability of the AUSF.

Proposing directions for countermeasures against the expanded attack surface, thereby laying the groundwork for future discussions on a secure 6G roaming framework.

In conclusion, This study empirically demonstrated the structural vulnerabilities of 6G roaming through a realistic experimental testbed, providing evidence to support operators and standardization bodies in establishing a 6G security framework. These directions can directly inform 3GPP and GSMA working groups as they refine security baselines for 6G roaming, ensuring that emerging standards incorporate resilience against SUCI-based flooding and replay attacks. In particular, the findings offer practical insights into 3GPP roaming standards, such as the N32 interface and SEPP/SCP interworking procedures defined in 3GPP TS 29.573 [

42], as well as authentication and key management aspects specified in 3GPP TS 33.501 [

30]. Moreover, these results are aligned with broader industry guidelines, including GSMA FS.40 [

43], which emphasizes end-to-end security and inter-PLMN trust models. For example, the load concentration observed at the AUSF indicates the necessity of enhancing resource protection and distribution mechanisms at the standardization level, while SUCI-based attack patterns highlight the need to strengthen identity protection and integrity verification procedures.

Future research may extend in the following directions: (1) verifying amplification effects under multi-V-PLMN distributed attack scenarios; (2) integrating post-quantum cryptography (PQC) with the 6G-AKA protocol to evaluate next-generation authentication and key management structures; (3) applying AI-based anomaly detection to compare and validate the effectiveness of diverse learning algorithms for early threat detection and prediction; and (4) employing blockchain-based distributed ledger structures to enhance transparency and integrity in UDM/UDR key management and logging. By linking these outcomes with ongoing 3GPP and GSMA standardization discussions, this line of research can contribute to the establishment of concrete guidelines for secure 6G roaming frameworks.