Advanced Ultrasonic Diagnostics for Restoration: Effectiveness of Natural Consolidants on Painted Surfaces

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- (2)

- Funori, a red algae extract widely adopted in recent decades for its adhesive and consolidating properties on paper [15], canvas, wood, and wall paintings [16]. Its optical behavior makes it particularly suitable for matte surfaces [17]. Funori has also been applied in cleaning, stain removal, and surface deformation treatments [18].

- (3)

- Opuntia ficus-indica mucilage, an experimental material that has shown promising results in recent years. In addition to its historical use in pre-Hispanic Mesoamerican art [19], it has been successfully tested as an additive in mortars for stucco repairs on canvas and stone, and as a consolidant for calcium carbonate-based canvas preparations [20]; as an additive in lime mortars [21] and adobe constructions typical of Mesoamerican architecture [22].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Replicas Preparation and Painting Techniques

2.2. Extraction Methods of Natural Polymers

2.3. Non-Destructive Analysis

2.3.1. Colorimetry

2.3.2. Automated Ultrasonic Mapping System with Non-Contact Probes and Data Analysis

2.3.3. Contact Angle Measurement

2.4. Peeling Test for Consolidation Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Colorimetric Measurements

3.2. Peeling Test

3.3. Automated Ultrasonic Mapping System

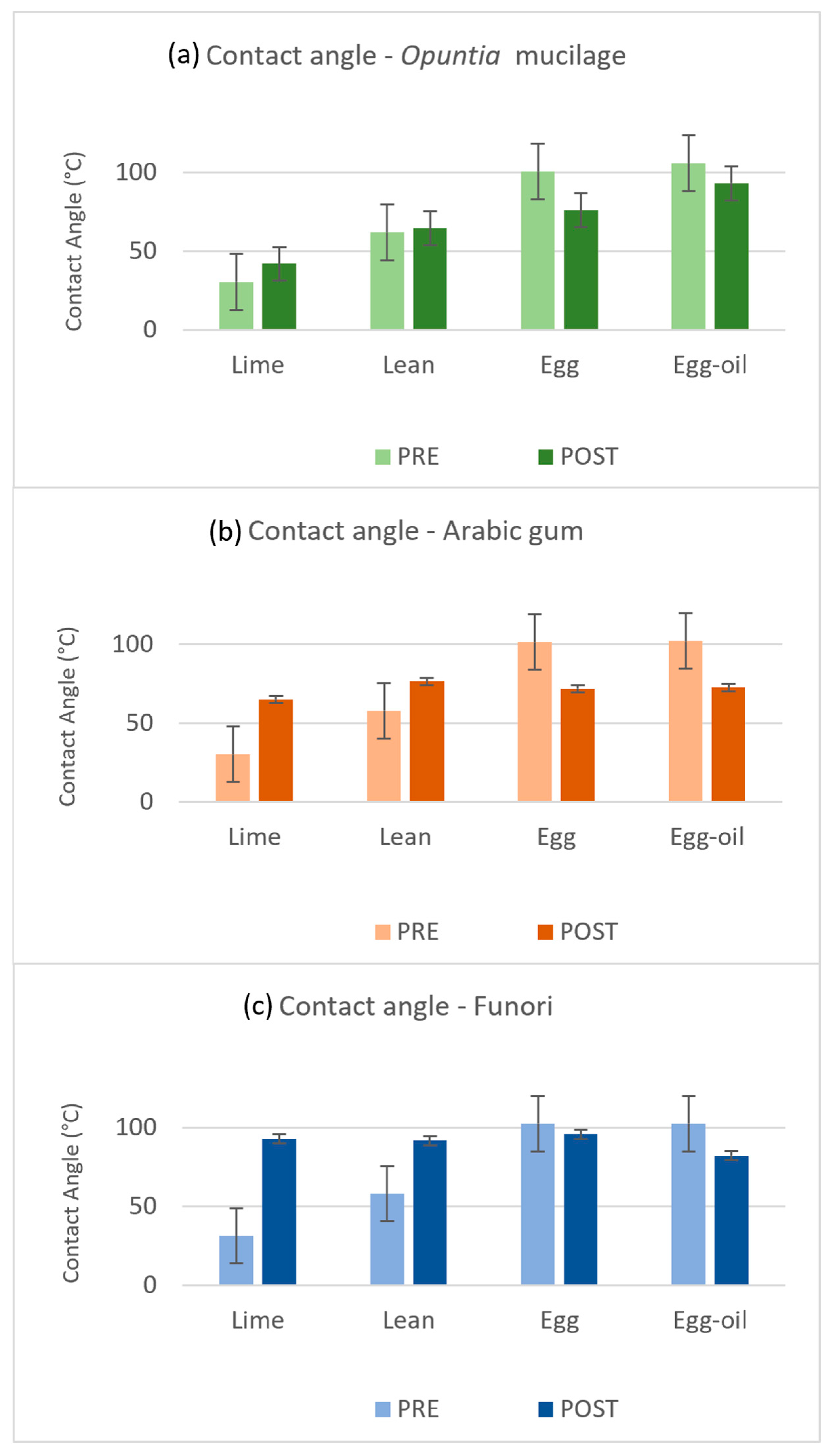

3.4. Contact Angle Measurement

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Drdácký, M.; Lesák, J.; Rescic, S.; Slížková, Z.; Tiano, P.; Valach, J. Standardization of peeling tests for assessing the cohesion and consolidation characteristics of historic stone surfaces. Mater. Struct. 2011, 45, 505–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chimenti, D.E. Review of air-coupled ultrasonic materials characterization. Ultrasonics 2014, 54, 1804–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirinu, A.; Saponaro, A.; Nobile, R.; Panella, F.W. Low-velocity impact damage quantification on sandwich panels by thermographic and ultrasonic procedures. Exp. Tech. 2024, 48, 299–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, A.; Patel, K.; Bhardwaj, M.C.; Fetfatsidis, K.A. Application of advanced non-contact ultrasound for composite material qualification. In Proceedings of the CAMX 2014—The Composites and Advanced Materials Expo, Orlando, FL, USA, 13–16 October 2014; SAMPE: Orlando, FL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bhardwaj, M.C.; Neeson, I.; Langron, M.E.; Vandervalk, L. Contact-Free Ultrasound: The Final Frontier in Non-Destructive Materials Characterization. In Ceramic Engineering and Science Proceedings; Jessen, T., Ustundag, E., Eds.; Wiley-American Ceramic Society: Westerville, OH, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Pagliaroli, T.; Pagliaro, A.; Patanè, F.; Tatì, A.; Peng, L. Wavelet analysis of ultra-thin metasurfaces for hypersonic flow control. Appl. Acoust. 2020, 157, 107032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatì, A. I sistemi di mappatura non distruttiva UT. EAI—Energ. Ambiente E Innov. 2021, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vun, R.; Eischeid, T.; Bhardwaj, M. Quantitative Non-Contact Ultrasound Testing and Analysis of Materials for Process and Quality Control. In Proceedings of the 9th European Conference on NDT, Berlin, Germany, 25–29 September 2006; ECNDT: Berlin, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y.; Xia, G.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Huang, J. A novel air-coupled ultrasonic technique for assessing the weathering degree of sandstone heritage. J. Cult. Herit. 2025, 74, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiolo, A.M.; D’Acquisto, L.; Maeva, A.R.; Maev, R.G. Wooden panel paintings investigation: An air-coupled ultrasonic imaging approach. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2007, 54, 836–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadrucci, M. Sustainable Cultural Heritage Conservation: A Challenge and an Opportunity for the Future. Sustainability 2025, 17, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, M.; Melo, M.J.; de Carvalho, L.M. Towards a Sustainable Preservation of Medieval Colors through the Identification of the Binding Media, the Medieval Tempera. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mshelia, Y.M.; Lawan, M.Z.; Lawan, D.M.; Sulum, A.M. Effect of pH on Microbial Growth and Performance of Paint Produced Using Gum Arabic as a Binder. Asian J. Sci. Technol. Eng. Art 2025, 3, 1634–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Zhu, W.; Chen, X.; Liu, X. Applications and Challenges of Modern Analytical Techniques for the Identification of Plant Gum in the Polychrome Cultural Heritage. Coatings 2025, 15, 1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudone, F. Funori Seaweed Extracts as Alternative Material to Semi-Synthetic Products Used in Paper Conservation. Progressus 2020, 7, 6–18. [Google Scholar]

- Catenazzi, K. Evaluation of the use of Funori for consolidation of powdering paint layers in wall paintings. Stud. Conserv. 2017, 62, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, T.; Michel, F. Studies on the Polysaccharide JunFunori Used to Consolidate Matt Paint. Stud. Conserv. 2005, 50, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrold, J.; Wyszomirska-Noga, Z. Funori: The Use of a Traditional Japanese Adhesive in the Preservation and Conservation Treatment of Western Objects. In Adapt & Evolve 2015: East Asian Materials and Techniques in Western Conservation; Icon: London, UK, 2017; pp. 69–79. [Google Scholar]

- Magaloni Kerpel, D.I. Metodología Para El análisis de la Técnica Pictórica Mural Prehispánica: El Templo Rojo de Cacaxtla, México; IINHA: Mexico City, Mexico, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- D’Ottavio, S.; Persia, F.; Mirabile Gattia, D.; Lavorini, B.; Coladonato, M.; Cassese, G.; Carnazza, P. Sostenibilità e restauro: Analisi sperimentali sulla mucillagine di Opuntia ficus-indica per il consolidamento dei dipinti. In Atti del XVII Congresso Nazionale IGIIC «Lo Stato dell’Arte»; IGIIC: Matera, Italia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Alisi, C.; Bacchetta, L.; Bojorquez, E.; Falconieri, M.; Gagliardi, S.; Insaurralde, M.; Martinez, M.F.F.; Orozco, A.M.; Persia, F.; Sprocati, A.R.; et al. Mucilages from different plant species affect the characteristics of bio-mortars for restoration. Coatings 2021, 11, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricaldi, J.A.P.; Chavez, J.A.P.; Parian, G.J.M.; Luna, M.I.L. Evaluation of the Mechanical Properties of Adobe with the Addition of Rice Husk Ash and Opuntia ficus-indica. SSRG Int. J. Civ. Eng. 2025, 12, 79–96. [Google Scholar]

- Aldrovandi, A.; Altamura, M.L.; Cianfanelli, M.T.; Ritano, P. I materiali pittorici: Tavolette campione per la caratterizzazione mediante analisi multispettrale. OPD Restauro 1996, 8, 191–210, 101–103. [Google Scholar]

- Hebborn, E. Il Manuale del Falsario; Neri Pozza Editore: Vicenza, Italia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cennini, C.; Frezzato, F. (Eds.) Il Libro dell’Arte; Neri Pozza Editore: Vicenza, Italia, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Prasad, N.; Thombare, N.; Sharma, S.C.; Kumar, S. Gum arabic—A versatile natural gum: A review on production, processing, properties and applications. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 187, 115304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorter, L.; Seymour, K.; van den Burg, J.M.; van den Berg, K.J. Consolidation of Paint and Ground: Paintings Conservation. Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands, 2023. Available online: https://www.cultureelerfgoed.nl (accessed on 18 December 2025).

- Carnazza, P.; Francone, S.; Kron Morelli, P.; Reale, R.; Sammartino, M.P. Retouching Matt Contemporary Paint Layers: A New Approach Using Natural Polymers. Ge-Conserv 2019, 18, 384–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, J.; van Lookeren Campagne, K.; Megens, L.; Wei, B.; de Groot, S. Scratching the Surface: Research into the Use of Funori as Consolidant for Friable White Surface Coatings on Greek and Roman Terracotta Figurines. Heritage 2023, 6, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Gattuso, C.; Campanella, L.; Giosafatto, C.V.L.; Mariniello, L.; Roviello, V. The Consolidating and Adhesive Properties of Funori: Microscopy Findings on Common and Ancient Paper Samples. J. Cult. Herit. 2021, 48, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, G.F.A.; Pereira, M.M.L.; de Souza, F.A.; Palma e Silva, A.A.; Capuzzo, V.M.S.; Machado, F. Opuntia ficus-indica Mucilage: A Sustainable Bio-Additive for Cementitious Materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 396, 139254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Ottavio, S.; Manzo, E.; Bacchetta, L.; Tatì, A.; Alisi, C. Il gel di Opuntia: Una proposta sostenibile per il consolidamento di pitture murali “a secco”. In Atti del XL Convegno Scienza e Beni Culturali—Le prossime Sfide per I Beni Culturali: Ricerca, Competenze e Professioni a Fronte di Cambiamenti Climatici, Sostenibilità e Transizione Digitale; Driussi, G., Morabito, Z., Eds.; Edizioni Arcadia Ricerche: Venezia, Italy, 2025; pp. 725–736. [Google Scholar]

- NORMAL 43/93; Misure Colorimetriche di Superfici Opache. NORMAL Commission: Sesto Fiorentino, Italy, 1994.

- UNI EN 15802; Determinazione dell’Angolo di Contatto Statico. UNI: Milano, Italy, 2010.

- NORMAL 33/89; Misura dell’Angolo di Contatto Acqua–Materiale Lapideo in Condizioni Statiche. NORMAL Commission: Sesto Fiorentino, Italy, 1989.

- Drdácký, M.; Slížková, Z. In situ peeling tests for assessing the cohesion and consolidation characteristics of historic plaster and render surfaces. Stud. Conserv. 2015, 60, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokrzycki, W.; Tatol, M. Color difference Delta E—A survey. Mach. Graph. Vision 2011, 20, 383–411. [Google Scholar]

- ImageJ. Available online: https://imagej.net (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Stalder, A.F.; Kulik, G.; Sage, D.; Barbieri, L.; Hoffmann, P. A Snake-Based Approach to Accurate Determination of Both Contact Points and Contact Angles. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2006, 286, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, J. A Comparative Study of Funori, JunFunori and TriFunori. Bachelor’s Thesis, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, D.; Zhang, J. Two-step detection of concrete internal condition using array ultrasound and deep learning. NDT E Int. 2023, 139, 102945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Support | “Arriccio” | “Intonachino” | Tempera Colors | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tile | Mortar | Mortar | Lean | Egg–oil | Lime | Egg |

/ | Lime putty and marble powder “00” 1:3 (v/v) | Lime putty and marble powder “000” 1:2 (v/v) | Rabbit glue; dw 1:1 (w/w); pigments | 2 egg yolks; 10 drops lavender oil; 20 mL of linseed oil; pigments | 60 g Limeputty; 100 g dw; pigments | Egg yolk; dw 1:1 (w/w); pigments |

| Category | Arabic Gum | Funori | Opuntia ficus-indica |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physico-chemical characteristics | -Polysaccharide + glycoprotein -Water-soluble -Slightly acidic–neutral pH -Viscosity concentration-dependent -Surface adhesion -Limited penetration -Possible gloss increase | -Algal polysaccharides -Water-soluble (after heating) -Matte film -Preparation-dependent viscosity, -Superficial consolidation | -Hydrophilic polysaccharide -Water-soluble -Film at low concentration -Extraction-dependent viscosity -Surface + sub-surface action -Good chromatic stability |

| Supplier | G. Poggi s.r.l (Italy) | G. Poggi s.r.l (Italy) | Organic cultivation (S.Cono, Sicily, Italy) |

| Advantages | -Long historical use -Easy preparation -No toxic -Large global market demand -Maintains substrate breathability (water vapor permeability) | -Matte appearance -Suitable for fragile surfaces -Natural and sustainable -Water-soluble -Low bioreceptivity -Versatile material | -Natural and sustainable -Improves cohesion -Long prehispanic use -Low bioreceptivity -Water retention-gel formation -Versatile material |

| Limitations | -Hygroscopic -Possible embrittlement with aging -Depolymerization processes induced by ultraviolet (UV) radiation -High bioreceptivity -Source variability | -High viscosity (low penetration) -Superficial accumulation -Possible salt residues -Source variability | -Experimental material -Source variability |

| References | [12,13,14,26] | [27,28,29,30] | [21,22,31,32] |

| Contact Angle (°C) | Surface Type | Graphical Representation |

|---|---|---|

| α = 0° | Super-hydrophilic |  |

| α > 30° | Hydrophilic | |

| 30° < α < 90° | Intermediate | |

| 90° < α < 140° | Hydrophobic | |

| α > 140° | Super-hydrophobic |

| Colorimetry | Opuntia Mucilage | Arabic Gum | Funori |

|---|---|---|---|

| ΔE ± sd | ΔE ± sd | ΔE ± sd | |

| Lime tempera | 0.6 ± 0.3 | 0.7 ± 1.3 | 0.7 ± 1.1 |

| Lean tempera | 0.5 ± 0.3 | 2.0 ± 1.6 | 0.6 ± 1.0 |

| Egg–oil tempera | 1.6 ± 0.5 | 1.0 ± 0.5 | 1.7 ± 1.8 |

| Egg tempera | 0.5 ± 0.5 | 1.8 ± 1.8 | 3.2 ± 5.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

D’Ottavio, S.; Tatì, A.; Bacchetta, L.; Alisi, C. Advanced Ultrasonic Diagnostics for Restoration: Effectiveness of Natural Consolidants on Painted Surfaces. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 504. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010504

D’Ottavio S, Tatì A, Bacchetta L, Alisi C. Advanced Ultrasonic Diagnostics for Restoration: Effectiveness of Natural Consolidants on Painted Surfaces. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):504. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010504

Chicago/Turabian StyleD’Ottavio, Stefania, Angelo Tatì, Loretta Bacchetta, and Chiara Alisi. 2026. "Advanced Ultrasonic Diagnostics for Restoration: Effectiveness of Natural Consolidants on Painted Surfaces" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 504. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010504

APA StyleD’Ottavio, S., Tatì, A., Bacchetta, L., & Alisi, C. (2026). Advanced Ultrasonic Diagnostics for Restoration: Effectiveness of Natural Consolidants on Painted Surfaces. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 504. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010504