1. Introduction

Microalgae are photosynthetic microorganisms that have attracted the attention of the scientific and academic communities due to their ability to fix carbon dioxide (CO

2), producing biomass and releasing oxygen (O

2) [

1]. The biomass generated, in turn, can be rich in fatty acids, proteins, carotenoids, antioxidants, and other metabolites [

2]. These secondary metabolites are organic compounds of high value for the energy, pharmaceutical, cosmetic, and food industries [

3].

The growth of microalgae is a spontaneous natural phenomenon; however, their isolated cultivation and the control of specific physicochemical conditions can accelerate this process. Additionally, this can affect mass and energy transfer and, therefore, on the quantity and quality of secondary metabolites [

4]. Closed microalgae cultivation is carried out in aerobic or anaerobic airtight containers equipped with lighting, also known as photobioreactors (PBRs) [

5]. These systems allow the manipulation and monitoring of variables such as temperature (T), PAR (Photosynthetically Active Radiation) light intensity, culture medium pH, dissolved gas concentration (O

2 and CO

2), medium agitation, and nutrient availability, among others [

5]. Because microalgae cultures are biological phenomena, they are characterized by being nonlinear, multivariable, and time-varying. These characteristics pose challenges for controlling these variables. Proper control of the variables in this bioprocess not only ensures high culture performance but also maintains system stability in the face of endogenous and exogenous disturbances [

6]. This has led to the development of automatic control and monitoring strategies for this type of bioprocess, which have contributed significantly to the field of bioengineering [

7]. In recent years, different control techniques have been proposed with the aim of ensuring monitoring of the culture operating conditions [

8,

9,

10]. The main challenge lies in the difficulty of mathematically modeling bioprocess, considering all the dynamics associated with high parametric variability, environmental fluctuations, and physiological responses specific to microalgae metabolism [

11].

Existing mathematical models have contributed to the understanding of microalgae cultivation, allowing their behavior to be represented using Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs) that integrate physical, chemical, and biological aspects [

12]. Based on these models, closed-loop control strategies such as Proportional–Integral–Derivative (PID) control [

13], Linear Quadratic Regulator (LQR) Control [

14], adaptive control [

15], and modern strategies such as Active Disturbance Rejection Control (ADRC) [

16] have been implemented. However, the validation of most of the strategies reported in the literature has been limited to numerical simulations due to the economic, logistical, and technical implications associated with experimental validation in pilot systems [

17,

18,

19]. In this regard, data-driven control strategies have emerged in recent years that allow controllers to be designed without the need for an explicit model of the system (or at least not one as detailed) [

20]. Among these, the Virtual Reference Feedback Tuning (VRFT) method has been presented as an alternative to address the challenges of bioprocess control [

18]. This strategy, initially developed by [

21], allows the parameters of a controller to be adjusted based on open-loop experimental data. The methodology consists of (1) defining a reference model (RM) that represents the desired behavior of the system and based on this, (2) constructing a virtual reference signal that simulates the ideal system tracking. Finally, (3) minimizing an objective function that expresses the error between the actual system output and the reference model output under the proposed controller [

20].

One of the main advantages of the VRFT method is that it is model-free, which makes it particularly useful in processes were formulating the equations governing the behavior of the system is complex [

22]. By avoiding the detailed mathematical modeling stage, VRFT significantly reduces design time and allows for a more agile implementation. In addition, the strategy can be adapted to different control structures, including PID controllers, discrete filters, and multivariable schemes [

23]. This feature, together with its data-driven approach, enables nonlinear systems to be effectively addressed using linear control techniques.

This article presents a practical application of the VRFT control strategy in a laboratory-scale microalgae cultivation system developed by the Process Automation Research Group, Universidad de La Sabana (CAPSAB). The proposal included the design, implementation, and experimental validation of a PID controller obtained using the VRFT strategy to regulate three process variables: medium temperature (T), PAR light intensity (I), and culture medium level (L). Additionally, this work contributes to the practical validation of a VRFT control technique that, despite its growing theoretical development, still requires further experimental validation in bioprocesses. Therefore, the objective of this study was to design, implement, and experimentally validate a VRFT control strategy for the closed cultivation of

Scenedesmus obliquus UTEX 393 in flat-bottomed photobioreactors. To achieve this objective, it was necessary to (i) develop a data-driven control scheme capable of managing the nonlinear and time-varying dynamics of the culture system. (ii) Experimentally evaluate the performance of VRFT for controlling temperature, level, and irradiance, and (iii) compare the controlled responses with a reference model and an existing mathematical model to assess robustness and reproducibility. This article is organized as follows:

Section 2 presents the preliminary concepts related to the VRFT method and its implementation for the control of a microalgae culture using a mathematical model.

Section 3 describes a case study of VRFT application for the culture of the microalgae

Scenedesmus obliquus UTEX 393.

Section 4 presents the results and discussion, and

Section 5 concludes the article.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. VRFT-Based Control Strategy

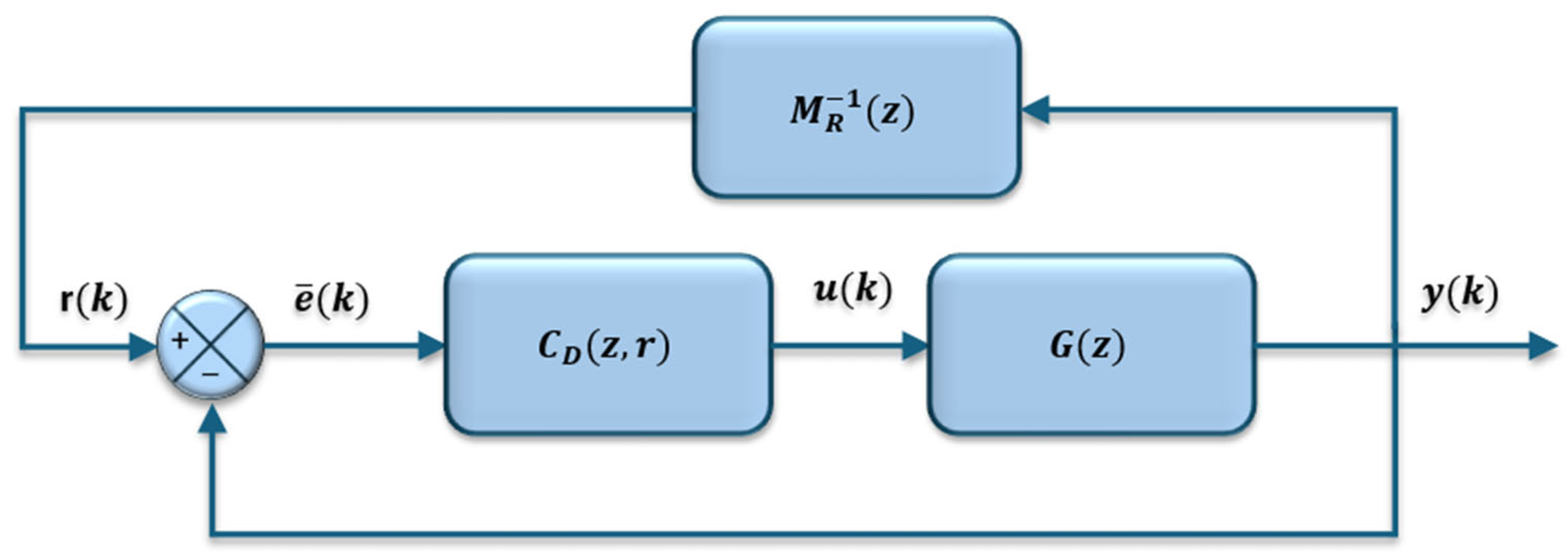

Virtual Reference Feedback Tuning (VRFT) is an optimal controller tuning strategy that allows parameters, in this specific case of a PID controller, to be adjusted without the need for a mathematical model. Instead, a parametric identification model is used, identified from a set of input and output data from the open-loop system. The formal structure of the control system is illustrated in

Figure 1, where

G(

z) is the plant transfer function and

MR(

z) is a reference model that describes the desired system dynamics.

MR(

z) generates a virtual error

that corrects the error of the controller

e(

k). The control signal is given by Equation (1).

where

is a discrete-time controller with

z =

k + 1. There is also a parameter vector

that drives the output

y(

k) to a desired value.

Since VRFT is an optimal control strategy, the control objective corresponds to minimizing the objective function expressed in Equation (2).

Note that the ratio expressed in the quadratic norm given by Equation (2) corresponds to the transfer function of the feedback system shown in

Figure 1. Therefore, VRFT is given by the following algorithm:

Based on an open-loop experiment, generating the vectors and storing the input and output information of the process, respectively.

Define a desired reference model .

Calculate the virtual error given by the relation .

Determine the parameter vector\rho of the controller that satisfies the criterion .

Extract the parameters of a Proportional Integral Derivative (PID) controller from the vector .

Implement the discrete PID filter with structure .

Since microalgae growth involves intrinsic phenomena caused by the metabolism of these microorganisms, coupled with nonlinear and time-varying dynamics, it depends on operating conditions that favor the production of biomass and/or secondary metabolites. Therefore, for this application, it is not feasible to conduct open loop experiments to obtain stoichiometric data, without compromising microorganism growth. However, in this work, the VRFT method was implemented based on the linearization of the kinetics expressed in the mathematical model reported in [

24]. The VRFT methodology is particularly suitable for microalgae cultivation because it eliminates the need to derive a complete nonlinear kinetic model, whose parameters change over time due to illumination, nutrient depletion, physiological shifts, and environmental variability. Unlike classical model-based techniques (PID with tuning, LQR, or MPC), VRFT directly tunes the controller using experimental data, making it inherently robust to nonlinearities and to the time-varying nature of microalgal growth. This model-free characteristic significantly reduces implementation complexity and improves adaptability in real biotechnological systems.

2.2. Mathematical Model Considerations

Mathematical modeling seeks to represent the dynamic behavior of systems as accurately as possible through ordinary differential equations (ODEs). In relation to microalgae models, mass and energy balance equations have been used together with chemical kinetics, as shown in the model proposed by [

25]. This model describes the functional relationship between a Michaelis–Menten reaction of the form

X(

t0)

S(

t0)

X(

t)

S(

t) and the associated material and energy balances. Equation (3) shows the modeled stoichiometry.

where

X(

t) [mg·L

−1] is the biomass,

S(

t) [µmol·L

−1] is the substrate concentration,

Q(

t) [µmol·µm

−3] is the flow rate,

V [L] is the retention volume,

D(

t) [day

−1] is the dilution rate,

q(

t) [µmol·µm

−3] represents the amount of substrate as a function of biomass growth

X(

t), and

µ(

q,

I) [day

−1] is the specific growth rate of the inoculated strain.

ρm [µmol·µm

−3·day

−1] corresponds to the maximum specific growth response and was obtained from the nonlinear PBR model proposed by [

25]. Finally,

KS [µmol·L

−1] is the substrate saturation constant.

On the other hand,

µ(

q,

I), the photoinhibition factor

µI(

I), and the optimal light intensity (

Iopt [µE·m

−2·s

−1]) are determined in (4), respectively.

where

is the maximum growth rate of microorganisms,

KQ [µmol·µm

−3] is the minimum rate of substrate consumption as a function of biomass generated,

Iin [µE·m

−2·s

−1]. The parameters entering the model are those reported in [

24,

25].

2.3. Considerations for the Design of the Controller Based on the Theoretical Model

A theoretical reference model MR(t) was obtained from the linearization of the mathematical model expressed in Equations (3) and (4), which was discretized, giving rise to MR(z).

Remark 1 [Model linearization]. Consider a system of the form . The matrix corresponds to the Jacobian matrix of evaluated at an equilibrium point .

The effect of MR(z) on the reference signal r(k) generates a virtual reference that is constrained by the same dynamics as MR(z). Since this behavior is defined near the system’s stable equilibrium points, the output y(k) is expected to reach the desired reference value under steady-state conditions and to accurately track any variations applied to that reference.

It is worth clarifying that, although VRFT is a model-free tuning method, it requires a reference model MR(z) that specifies the desired closed-loop dynamics. In this work, MR(z) was derived from the linearization of the nonlinear growth model, not for controller design, but solely to define the desired dynamic behavior. The VRFT algorithm itself does not use the model equations.

2.4. Photobioreactor Overview

Figure 2 depicts the configuration of the implemented PBR system, in which

X(

t) represents the biomass,

S(

t) denotes the substrate,

Q(

t) is the inlet flow rate, and

V corresponds to the retention volume. The operation of this PBR is governed by the following considerations:

The white light was emitted by surface-mounted Light Emitting Diode (LED) arrays.

Gas exchange (O2-CO2) and crop uniformity were achieved by a low-pressure aeration agitation system (<1 bar).

The dilution rate represents the ratio of the added medium to the total volume of the culture over a given period, which is represented as .

The substrate S(t) corresponds to the culture medium that supplies essential nutrients for microalgae growth.

2.5. Functions Obtained for the Implementation of VRFT

A discrete transfer function was identified based on the collection and analysis of three (3) process variables datasets (temperature, PAR light intensity, and culture medium level) obtained from the open-loop operation of the system with a sampling time of 1 s. The data were imported into MATLAB 2024

®, and the System Identification Toolbox was used to identify the discrete transfer function expressed in Equation (5).

On the other hand, the reference model

MR(

z) (explained in

Section 2.3) representing the linearization and discretization of the mathematical model is shown in Equation (6).

The following criteria were taken into consideration for the selection of this M_R(z):

A simplified model is preferred, as it eases implementation.

The model captures the transient growth behavior observed in microalgae cultivation.

The system exhibits slow dynamic response, resulting in a long rise time.

Maximum acceptable overshoot and oscillations of process variables (temperature, PAR light intensity, and culture medium level), as microalgae are affected by these variations.

Maintain the reference point for process variables during the microalgae growth period.

Finally, the implementation of the VRFT algorithm led to the determination of the parameters of a PID controller, which was expressed using a discrete PID filter. The transfer function of the discrete filter was obtained using MATLAB 2024

® Control System Toolbox (see Equation (7)).

2.6. Controller Implementation

The controller was simulated in MATLAB 2024

® and then implemented in a pilot system designed for the supervision and control of PBRs in a continuous microalgae culture. The system combines hardware and software elements to manage process variables such as temperature, PAR light intensity, pH, culture medium level, O

2/CO

2 gas ratio, and

D(

t), among others. The software was developed in Python 3.13 under the Object-Oriented Programming (OOP) paradigm and runs on an ARK 3530F computer Advantech (Taipei, Taiwan). The hardware was designed with modular architecture and consists of three continuous PBRs coupled to an instrumentation module responsible for recording and controlling process variables. The signals from the sensors were conditioned by electronic circuits and then processed by an ARM Cortex-M3 microcontroller.

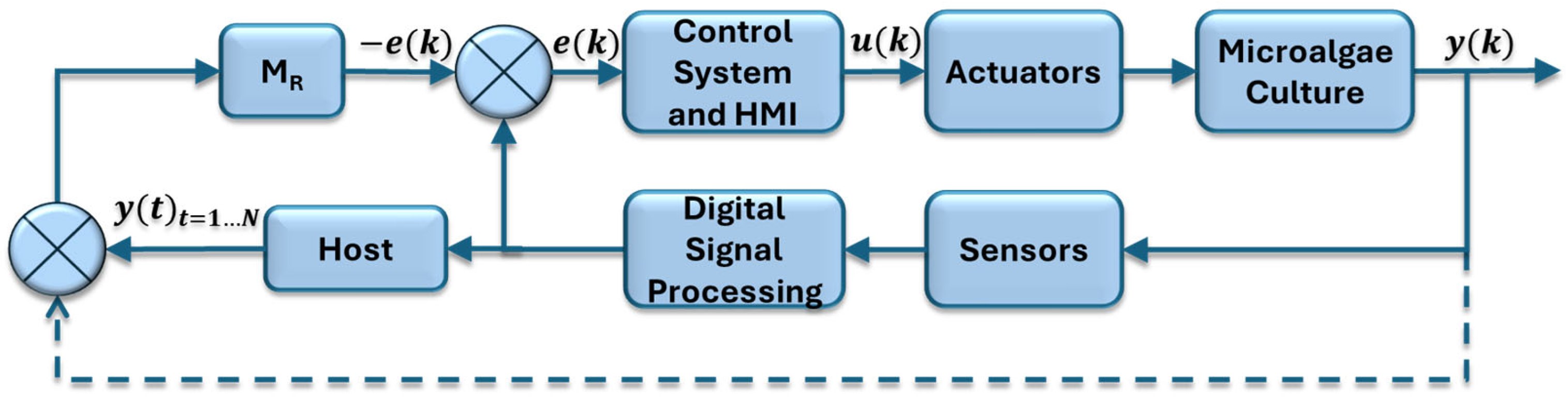

Figure 3 illustrates the general layout of the system.

Figure 4 illustrates the block diagram corresponding to the control strategy developed. In this diagram, the block labeled “Microalgae Culture” represents the dynamics associated with cell growth inside each PBR, as well as the input and output variables involved in the bioprocess. The “Sensors” and “Actuators” blocks refer to the instrumentation that enables both the measurement and control of process variables. The block called “Digital Signal Processing” is responsible for conditioning the signals through amplification, filtering, and transmission operations. The “Control system and Human–Machine Interface (HMI)” block integrates the algorithms responsible for processing the collected information, defining desired references, real-time visualization of the process, and implementation of the reference model

MR(

z). Finally, the “Host” module stores sensor data for process variables (temperature, PAR light intensity, level, dissolved oxygen, pH) in a relational database.

2.7. Implementation of Anti-Windup for SIMO System: Level Control

In continuous cultivation, it is necessary to maintain a constant culture volume. This is achieved by introducing fresh medium and extracting culture broth at the same rate. To achieve this, it is necessary to control the culture broth level in the PBR by activating a Peristaltic Metering Pump (PMP) for filling and another for extraction, which exhibits the characteristic of a Single Input-Multiple Output (SIMO) subsystem structure. This characteristic implied a variation to the implementation of the PID controller obtained by the VRFT method compared to that used for the temperature and PAR light intensity subsystems. In each of those cases, only a single actuator was required, reflecting its Single Input-Single Output (SISO) structure.

Since the structure obtained by the VRFT method for the temperature and PAR light intensity subsystems corresponded to a SISO system, when implementing the level subsystem. It was found that when the initial fill level condition of the PBR was close to zero. The controller response increased exponentially, approaching singular behavior. That is, when the level reached the reference value, the control signal exhibited changes in magnitude and sign, generating unbounded oscillations and marginally stable behavior. This generated accelerated switching in the PMPs, compromising their useful life and introducing electrical noise into the system. Additionally, when observing the behavior of the PID controller, it was evident that as the level approached values close to the reference, the integral term error

eI, had accumulated values that affected the stability of the system. Therefore, an anti-windup action was incorporated by defining saturation limits for the PMP flow rate. This anti-windup mechanism consisted of resetting the integral action of the PID controller when the tracking error

e(

tk) changed sign (Equation (8)).

Note that the integral action kiTs are equal to zero if and only if the product of the current error e(tk) and the previous error e(tk − 1) is less than zero. This solution prevented the over-accumulation of the integral action, allowing the two PMPs to be controlled by a single control signal.

2.8. Control Algorithm Programming

Figure 5 illustrates the flowchart of the VRFT method developed in Python 3.13 using an object-oriented programming approach. The algorithm’s operational structure begins with the import of the libraries required for numerical computation, followed by the initialization of the control system’s input and output variables. The experimental open-loop data were retrieved from a relational database and arranged into two vectors: [data.u] for the inputs and [data.y] for the outputs.

The reference model presented in Equation (5) was expressed in a generalized form as . A key requirement of the procedure is that the experimental data vectors and the virtual reference vector-along with the resulting output vector, must all share the same dimensionality. The iterations used for minimizing the objective function were implemented through for loops. It is also important to note that this structure pertains solely to the VRFT-based control algorithm. The full software package contains additional subclasses dedicated to other functionalities, such as the HMI and database management.

Once the controller parameters had been tuned using the VRFT algorithm, it was implemented for the three laboratory-scale PBRs (see

Figure 6). For each PBR, a subclass called “Control photobioreactors Class” was created, in which a constructor method was defined where the controller parameters (

kp,

ki,

kd) were initialized with the values determined by the VRFT algorithm and the respective setpoint values.

3. Case Study: Cultivation of Scenedesmus obliquus UTEX 393

To validate the control design developed for the process variables of temperature, PAR light intensity, and culture medium level, experiments were conducted in triplicate, cultivating the microalga

Scenedesmus obliquus UTEX 393. The culture medium used was an adaptation of Bristol Medium (

https://utex.org/products/modified-bold-3n-medium?variant=30991514763354 (accessed on 15 December 2025)), which was prepared according to the protocol described in the UTEX database.

The preparation of the Modified Bold 3N Bristol medium was carried out in a laminar flow cabinet Lumes (Bogotá, Colombia) that had been previously switched on and stabilized, using clean and dry borosilicate glassware. To prepare a total volume of 9 L of medium, three autoclavable 3 L containers were used, each of which was initially filled with 850 mL of distilled water. Under continuous agitation on a magnetic stirring plate, the stock solutions of the inorganic components were added sequentially in the established order: first the NaNO3 solution (30 mL·L−1; final concentration 8.82 mM; 90 mL per 3 L container), followed by CaCl2·2H2O (10 mL·L−1; 0.17 mM; 30 mL per container), MgSO4·7H2O (10 mL·L−1; 0.30 mM; 30 mL per container), K2HPO4 (10 mL·L−1; 0.43 mM; 30 mL per container), KH2PO4 (10 mL·L−1; 1.29 mM; 30 mL per container), and finally NaCl (10 mL·L−1; 0.43 mM; 30 mL per container), ensuring complete homogenization of the medium after each addition. Once all components had been added, the final volume in each container was adjusted with distilled water until the target volume was reached. Throughout the entire procedure, no pH measurement or adjustment was performed.

The prepared medium was properly covered and sterilized in an autoclave TOMY (Oak Brook, IL, USA) under standard operating conditions. Upon completion of the sterilization process, the medium was allowed to cool until it reached a suitable temperature for vitamin addition. Subsequently, under aseptic conditions using a burner flame, sterile vitamin solutions of vitamin B12 (1 mL·L−1; 3 mL per container; 9 mL total), biotin (1 mL·L−1; 3 mL per container; 9 mL total), and thiamine (1 mL·L−1; 3 mL per container; 9 mL total) were added, gently mixing to ensure homogeneous distribution. Finally, the Modified Bold 3N Bristol medium was transferred to the PBRs for use.

The experimental conditions were an inoculum of 1900 cells mL−1, a culture medium volume of 1 L, a culture duration of 19 days, and a temperature of 25 °C. Illumination was provided using white light at a PAR light intensity of 100 μmol/m2s with a photoperiod of 18/6 h, along with constant agitation, aeration, and CO2 supply.

Sampling and Cell Counting

The UTEX protocol was followed for the analysis of the biomass generated and for cell counting. Samples of 500 μL of microalgae were taken every 36 h. These were mixed with 500 μL of saline solution containing 4% formaldehyde to stop cell growth. Finally, cell concentration was determined using a Neubauer chamber count at 40× magnification and expressed in cells per milliliter (cells mL

−1) [

26,

27,

28].

To ensure aseptic conditions and prevent contamination throughout the cultivation process, the photobioreactors were thoroughly washed and disinfected prior to operation using a solution of distilled water and 40% ethanol, followed by several intermittent rinses with distilled water. Additionally, because the system operates in a fully automated manner, there is no direct human intervention in the culture during the experiments, further minimizing the risk of external contamination.

4. Results and Discussion

This section presents the simulation and laboratory results for the design of a linear PID controller using the VRFT method. The experiments were carried out on a laboratory scale, in triplicate, with a sampling time of 5.5 s, equivalent to the sensor update frequency. The controlled process variables were temperature, PAR light intensity, and culture medium level. The initial conditions were T = 19.6 °C, I = 0 µmol·m−2·s−1, culture level = 9.4–10.2 cm, and inoculum density = 1.9 × 106 cells·mL−1.

4.1. Reference Tracking

Figure 7 shows the response of the controller

to the dynamics given by the reference model

MR(

z) and the mathematical model expressed by Equations (3) and (4). In

Figure 7a, unlike the responses of the controller and the reference model, the mathematical model does not exhibit asymptotic steady-state behavior.

Figure 7b shows that the controller tracks changes in the reference signal.

4.2. Temperature

Figure 8 illustrates the behavior of the plant in open loop. This response was used to identify the dynamic characteristics required for the VRFT strategy. The ambient temperature at the initial time t

0 = 0 was approximately 19.6 °C, while at the final time t

f = 100 min, it was approximately 22.3 °C. Region I shows the temperature increase at maximum heater power, while region II shows relatively stable behavior for which the temperature gradient tends to zero

. Since the temperature variation was minimal in the stable region, the heater was disconnected from its power supply in region III. At the intersection between region II and region III, a maximum impulse is observed in the measure response. This behavior suggests an electrical transient that is reflected as thermal capacitance effects a few moments after the abrupt disconnection of the heater.

Microalgae growth is affected by temperature changes.

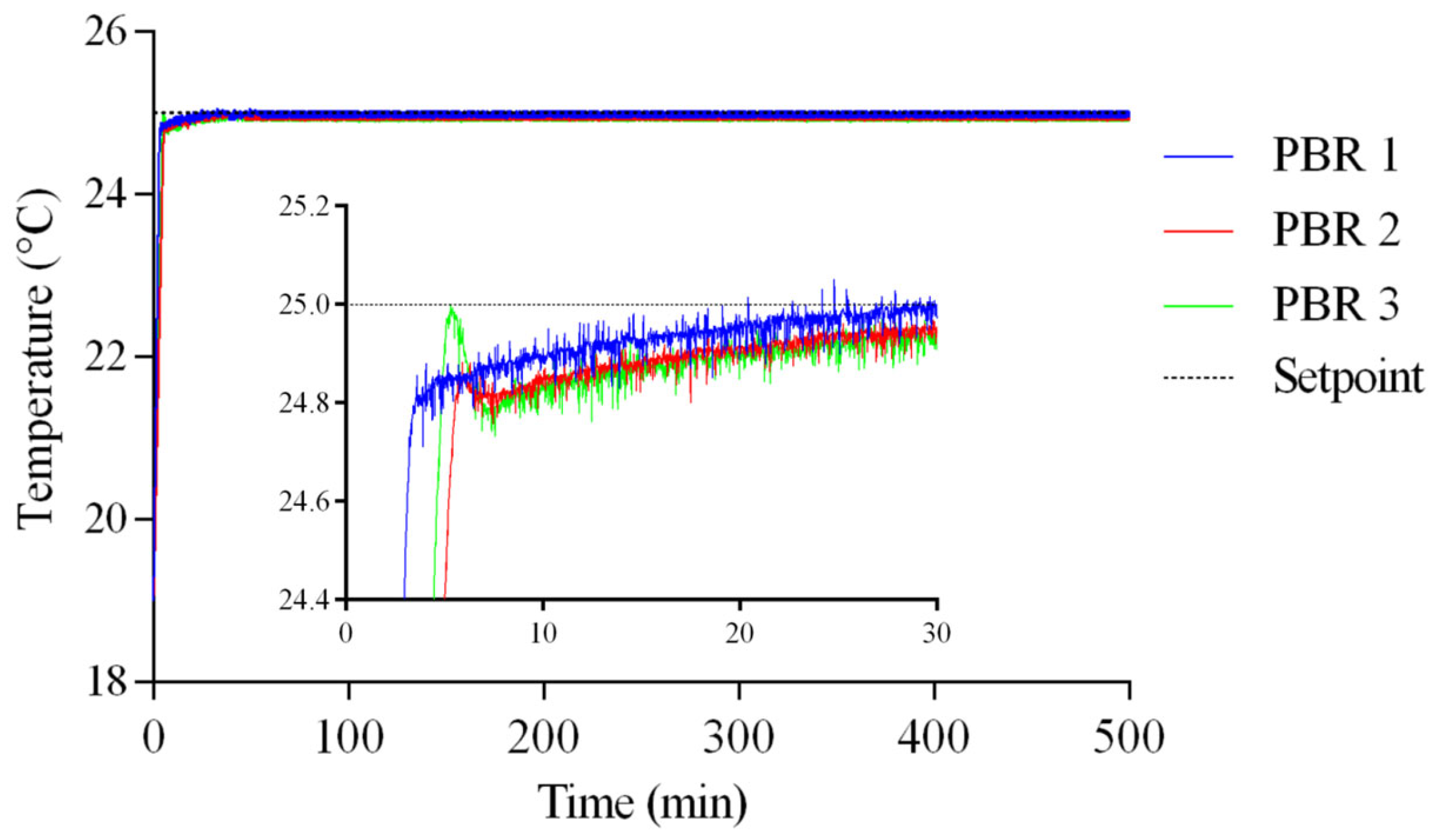

Figure 9 shows the process temperature of three (3) PBRs once the VRFT control strategy is implemented. The reference temperature (setpoint) was 25 °C. Additionally, steady-state variations of ±1% relative to the reference value were observed. This suggests the robustness of the controller in tracking the reference for the temperature variable under nominal conditions.

4.3. PAR Light Intensity

The culture was illuminated with white light emitted by surface-mounted LED strips.

Figure 10 shows the behavior of PAR light intensity in an open loop configuration. Region I corresponds to the inactive period, while region III illustrates the maximum PAR light intensity recorded by the sensor. Region II, on the other hand, represents the corresponding behavior when the actuator changes from off to on.

Figure 11 shows the variations in PAR light intensity obtained in the three PBRs. In this experiment, a reference setpoint of 100 µmol·m

−2·s

−1 was established. Once the desired reference was reached, multiple oscillations around the established reference value were observed. The amplitude of these oscillations was less than 10% of the nominal value. The differences in responses of the three PBRs suggest the incidence of external light, given the high sensor resolution. However, these results show that the controller responds quickly to changes in the actuator state.

4.4. Culture Medium Level

For level measurement and control in each PBR, an eTape analog sensor from Milon Technologies and two PMPs (one for filling and one for emptying) were required.

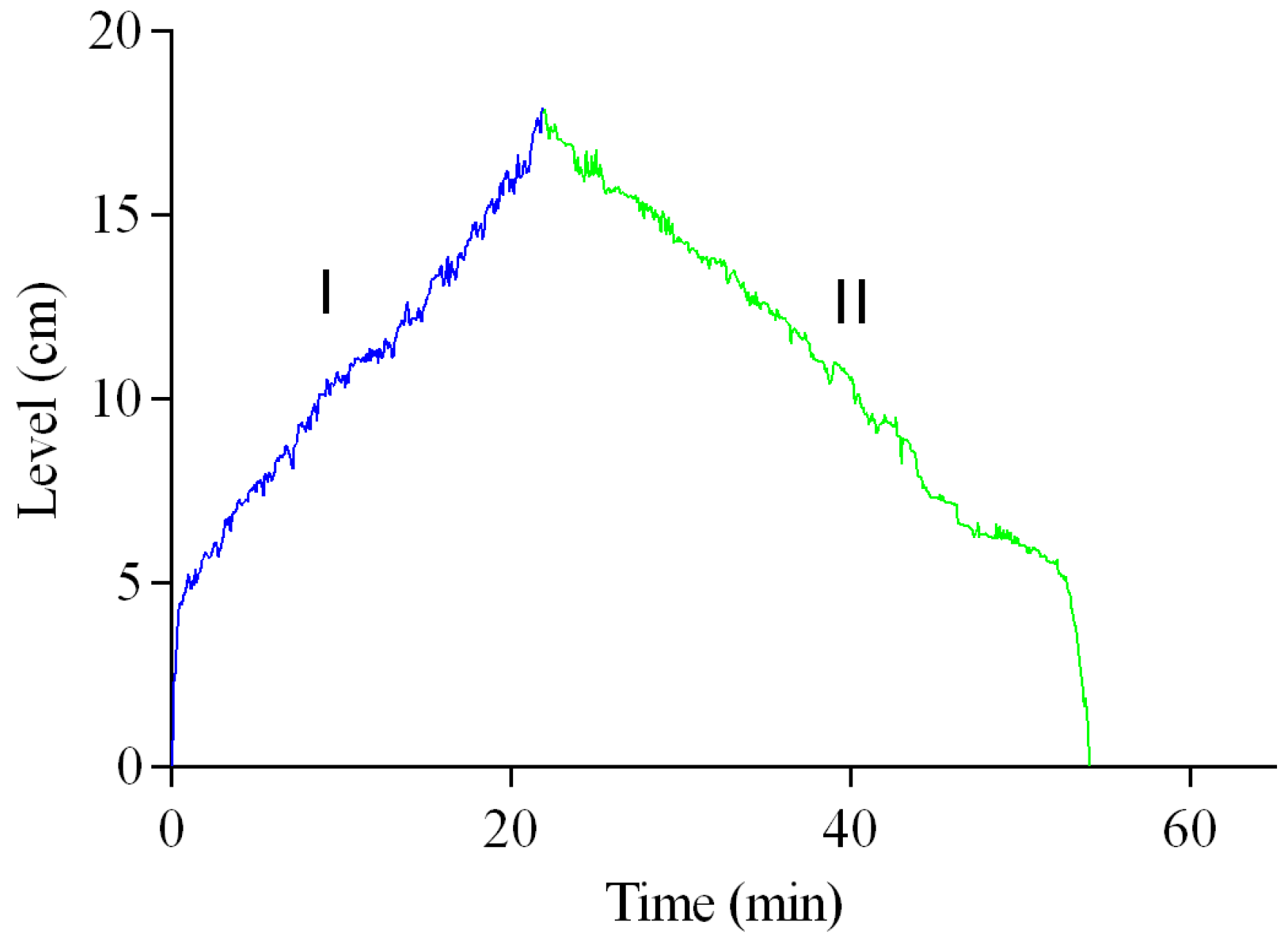

Figure 12 presents the experimentally obtained open-loop filling and emptying dynamics of the PBRs, which are included to characterize the intrinsic behavior of the level subsystem prior to closed-loop control. In region I, the filling behavior of each PBR can be observed, showing that during the first 5 cm, the rate of change in the level increases. This is because the PBRs have a geometry with a decrease in volume at the base. In region II, the emptying dynamics of the PBRs can be observed, showing that both filling and emptying take place over similar time intervals. Finally, it is suggested that the level oscillations observed in both regions can be attributed to the aeration and agitation system, which introduces turbulence into the system.

For each PBR, 1 L of culture medium was dispensed and inoculated with

Scenedesmus obliquus UTEX 393. The level control objective was to maintain 1 L of medium constant throughout the process. The differences between the level curves observed in

Figure 13 are due to the different geometries of the PBRs, as shown in

Figure 2. PBRs 1 and 2 presented comparable values close to 9.4 cm, while PBR 3 maintained a value of approximately 10.2 cm. Furthermore, for the level variable, when comparing the open-loop behavior (

Figure 12) with that of the closed loop response (

Figure 13), a decrease in the amplitude of the turbulence induced oscillations caused by the aeration system was observed.

4.5. Cell Counting and Growth Curve

Figure 14 shows the cell growth curves for

Scenedesmus obliquus UTEX 393 cultivated in the three PBRs for 19 days. Cell concentration was quantified in millions of cells per milliliter. PRBs 1 and 2 showed similar values of approximately 2500 cells mL

−1 on day 19. Meanwhile, PBR 3 showed a decrease in cell growth from day 6 to day 8, after which it exhibited a near-zero growth rate. When analyzing the behavior of PBR 3, a difference in the agitation method was identified in relation to the other PBRs, which could have influenced the decrease in cell growth. However, further investigation into the possible causes of this behavior is planned. In other words, the stagnation observed in PBR3 is associated with differences in mixing behavior caused by the alternative aeration configuration. Reducing the mixing intensity decreases the efficiency of CO

2 transfer to the liquid and limits the distribution of nutrients throughout the column. Although this mechanism is consistent with mixing theory, additional controlled experiments would be needed to quantitatively characterize the effects of turbulence and confirm this hypothesis.

4.6. Discussion

The results obtained in this study are consistent with reports in which model-based or model-free strategies are applied to microalgae cultivation. Compared with conventional PID controllers, VRFT offers improved robustness under nonlinear and time-varying conditions. In contrast to ADRC and MPC approaches, which require model derivation or online optimization, VRFT reduces computational complexity while achieving comparable dynamic performance.

The experimental results obtained in this study show good performance of the VRFT strategy designed to control temperature (25 ± 0.625 °C), PAR light intensity (100 µmol·m

−2·s

−1), and maintain a constant volume (1 L) in each PBR under nominal conditions. This capacity for precise tracking is necessary for the control of this bioprocess, which is characterized by nonlinear dynamics, Multivariable behavior, and sensitivity to exogenous disturbances [

29,

30].

The relevance of applying data-based control strategies, such as VRFT, lies in the ability of these strategies to adapt to different models, whether mathematical or parametric identification [

31].

Recent literature reports the use of model-free methods which allow practical applications with less computational effort and greater adaptability [

20,

22]. In particular, ref. [

20] showed through simulations that some model-free control strategies can improve their performance compared to other optimized systems. On the other hand, the robustness of the VRFT controller is supported by theoretical developments such as those reported in [

23], which incorporate H∞ constraints and particle swarm optimization, improving robustness margin against system disturbances. The experimental validation reported in this paper confirms the viability of using VRFT strategies for this type of bioprocess, thereby demonstrating its ability to track the operating conditions associated with process variables (temperature, PAR light intensity, and level) under nominal conditions. Likewise, the incorporation of Anti-Windup mechanisms for level control (SIMO subsystem) prevents excessive accumulation in the integral action and reduces actuator effort, suggesting a practical option without the need to redesign the control strategy.

Regarding controlled variables (temperature, PAR light intensity, and level), the literature has reported that these influence microalgae growth and therefore the overall efficiency of the bioprocess. Temperature is one of the parameters that affect microalgae metabolism, influencing photosynthesis, respiration, and the cell growth rate. This is because microalgae have a species-specific temperature range that favors growth; otherwise, metabolic efficiency decreases [

1]. Low temperatures slow growth and reduce productivity, while high temperatures can cause irreversible damage to cell structure. In addition, temperature variations influence the quality of the metabolites produced and the stability of the cultures [

32]. In this regard, the implementation of the control strategy designed in this work ensured operational stability based on data collection from the open-loop plant without relying on a mathematical model. Unlike other controller designs that incorporate thermal self-regulation and multivariable monitoring mechanisms based on mathematical models [

17,

33], the proposed approach does not require an explicit model.

PAR light intensity is a determining factor in microalgae growth, as it directly affects photosynthesis and, consequently, cell concentration. Adequate PAR light intensity ensures efficient metabolism, while low levels of this variable limit the productivity of the bioprocess [

34]. Conversely, high levels of PAR light intensity can cause photoinhibition and cell damage, reducing the overall efficiency of the culture [

35]. In our system, the controller managed to maintain PAR light intensity within the set range, avoiding both limitations and overexposure to light. This result is consistent with research highlighting the need to control not only PAR light intensity but also wavelength throughout the culture [

11]. Finally, it is known that variations in volume, whether due to evaporation, addition, or removal of the culture medium, can alter cell growth [

36,

37,

38,

39]. For this reason, another controlled variable was the PBR level, which helped maintain a constant volume of 1 L.

Overall, the experiment showed that controlling these process variables supported cell growth, reaching values of around 2500 cells mL−1 on day 19 of the Scenedesmus obliquus UTEX 393 culture in two of the three PBRs. In the third PBR, a decrease in cell concentration was recorded between days 6 and 8. This could be attributed to the turbulence caused by the aeration and agitation system that makes up that specific PBR, unlike the aeration and agitation system used in the other two PBRs.

This study has certain limitations. VRFT performance depends on the representativeness of the dataset used for tuning, and disturbances do not present during calibration may degrade robustness. Future research will explore hybrid VRFT–ADRC architectures, data-driven adaptive VRFT, and the integration of machine-learning-based models to enhance prediction accuracy under highly variable cultivation conditions.

5. Conclusions

In this study, a PID controller was designed and implemented using the Virtual Reference Feedback Tuning (VRFT) strategy to control three process variables (temperature, photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) light intensity, and level) in the closed cultivation of the microalga Scenedesmus obliquus UTEX 393. The results obtained show that the controller managed to maintain these variables within the defined operating values, ensuring the stability of the bioprocess. Temperature control allowed a reference value of 25 °C to be maintained and prevented steady-state errors that could have compromised cell growth. Similarly, PAR light intensity control was maintained at a value of 100 µmol·m−2·s−1, preventing both light limitation and photoinhibition, phenomena that directly affect microalgae growth. Level control ensured a constant culture volume of 1 L.

The use of VRFT proved to be a model-free alternative with low implementation complexity, especially in a type of bioprocess that is nonlinear and time-varying and for which a mathematical model cannot represent all the dynamics of the microorganism. The data-driven nature of this method allowed for satisfactory performance at low computational complexity compared to predictive or metaheuristic approaches, facilitating its implementation in laboratory settings and in the early stages of technological development. However, limitations were also identified, the main one being its poor performance in the face of disturbances, a scenario in which predictive methods, artificial intelligence, or hybrid approaches have reported significant advantages. This opens a future line of research aimed at integrating VRFT with advanced control strategies such as active disturbance rejection control (ADRC). As for future work, an analysis of the differences in PBR agitation will be carried out to correlate these data with the effect on the growth of microalgae cultivated in PBR 3.