Abstract

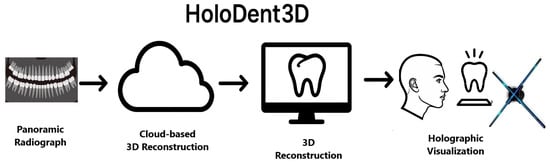

Panoramic radiography remains a cornerstone diagnostic tool in dentistry; however, its two-dimensional nature limits the visualisation of complex maxillofacial anatomy. Three-dimensional reconstruction from single panoramic images addresses this limitation by computationally generating spatial representations without additional radiation exposure or expensive cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) scans. This systematic review and conceptual study traces the evolution of 3D reconstruction approaches, from classical geometric and statistical shape models to modern artificial intelligence-based methods, including convolutional neural networks, generative adversarial networks, and neural implicit fields such as Occudent and NeBLa. Deep learning frameworks demonstrate superior accuracy in reconstructing dental and jaw structures compared to traditional techniques. Building on these advancements, this paper proposes HoloDent3D, a theoretical framework that combines AI-driven panoramic reconstruction with real-time holographic visualisation. The system enables interactive, radiation-free volumetric inspection for diagnosis, treatment planning, and patient education. Despite significant progress, persistent challenges include limited paired 2D–3D datasets, generalisation across anatomical variability, and clinical validation. Continued integration of multimodal data fusion, temporal modelling, and holographic visualisation is expected to accelerate the clinical translation of AI-based 3D reconstruction systems in digital dentistry.

1. Introduction

The field of dental imaging is at a pivotal point in its technological development. Over the past century, dental radiography has advanced from basic film-based systems to sophisticated digital imaging modalities, with each development bringing incremental improvements in diagnostic capability and patient safety. Today, dentistry is experiencing a paradigm shift driven by the convergence of advanced imaging technologies and artificial intelligence, fundamentally transforming how clinicians visualise, interpret, and use radiographic information [1,2].

Panoramic radiography, now ubiquitous in contemporary practice, is the most widely used extraoral imaging technique in modern dentistry, with an estimated 10 million examinations performed annually in Japan, 1.5 million in England and Wales, and a notable increase in the United States from approximately 11 million in 1993 to 21 million in 2014–2015 [3,4]. Its ability to capture the entire dentomaxillofacial complex in a single exposure has made it an essential diagnostic tool across all dental specialties. However, panoramic radiography remains inherently limited by two-dimensional projection geometry, resulting in loss of depth information, structural superimposition, and measurement inaccuracies that challenge diagnostic precision and treatment planning [5,6]. While cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) provides true three-dimensional visualisation, it requires significantly higher radiation exposure (50–1000 µSv vs. 2.7–24.3 µSv), incurs greater cost, and is less accessible in general practice settings [7].

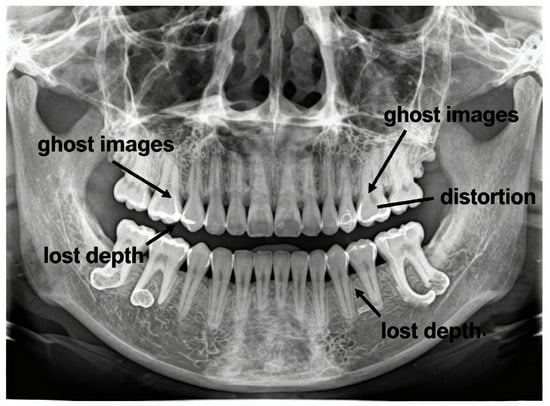

Recent advances in artificial intelligence and deep learning, particularly neural network architectures employing implicit representations and generative models, have demonstrated remarkable capability in reconstructing three-dimensional structures from limited two-dimensional projections [8,9]. These computational approaches offer the possibility of extracting 3D anatomical information from conventional panoramic radiographs—a challenging inverse problem that could bridge the dimensional divide between accessible 2D imaging and clinically necessary 3D visualisation. Figure 1 illustrates typical diagnostic challenges in panoramic imaging, including structural superimposition, ghost artefacts, magnification distortion, and loss of depth information.

Figure 1.

Diagnostic limitations of panoramic radiography: ghost artefacts, geometric distortion, and loss of depth information.

Despite progress, current reconstruction methods achieve structural similarity indices of approximately 0.7 and accuracies of 75–86%, leaving clinically relevant depth errors and reliability concerns that limit routine clinical deployment [10].

1.1. Scope and Objectives of This Concept Paper

This concept paper provides a comprehensive review of the current state of three-dimensional reconstruction from panoramic dental radiographs, focusing on computational methods capable of generating volumetric anatomical information from single-view two-dimensional projections. It examines the evolution from classical geometric techniques to contemporary AI-driven approaches—including deep learning architectures, implicit neural representations, physics-based modelling, and hybrid methods that integrate data-driven learning with geometric or anatomical priors. Both models trained on paired panoramic–CBCT datasets and those using synthetic panoramic images derived from CBCT volumes are considered, as both address the core single-view reconstruction challenge.

This paper addresses three central research questions: (1) which methodological approaches have been developed for single-view 3D reconstruction in dental panoramic imaging, and what computational principles underpin them; (2) how these methods perform quantitatively and qualitatively, including the evaluation metrics and validation strategies used to assess reconstruction accuracy; and (3) what limitations and practical barriers currently hinder clinical translation, along with promising avenues for future research.

In addition to reviewing the state of the art, this paper introduces the HoloDent3D conceptual model—an innovative framework that integrates AI-based 3D reconstruction with holographic visualisation and gesture-based interaction. By bridging the gap between complex radiographic data and everyday clinical practice, HoloDent3D aims to offer a cost-effective, radiation-free alternative to cone-beam computed tomography that enhances diagnostic precision, patient engagement, and treatment planning while remaining compatible with existing dental workflows.

1.2. Structure of This Paper

This paper follows a systematic organisational structure divided into seven main sections. Section 1 introduces the clinical context and motivation, explaining limitations of panoramic radiography, the 3D reconstruction challenge, and the scope and objectives of the review. Section 2 covers the theoretical foundations, including panoramic radiography principles, mathematical foundations of 3D reconstruction, and relevant anatomical considerations. Section 3 provides a comprehensive search strategy of the literature. Section 4 systematically examines classical and geometric approaches, deep learning architectures, neural implicit representations, and state-of-the-art frameworks, such as Occudent, NeBLa, ViT-NeBLa, X2Teeth, PX2Tooth, Oral-3D/Oral-3Dv2, and multi-view or sequential approaches. Section 5 surveys existing applications of holographic and augmented reality technologies in dentistry for education, treatment planning, and surgical navigation. Section 6 introduces the HoloDent3D conceptual model, describing its objectives, system architecture with three stages (input acquisition and preprocessing, AI-driven 3D reconstruction, and holographic visualisation), and feasibility considerations including technical challenges related to data availability, integration, latency, calibration, and regulation. Section 7 discusses clinical applicability, integration scenarios, ethical and regulatory considerations, and research challenges for future development.

2. Fundamentals of Panoramic Radiography and 3D Reconstruction

2.1. Panoramic Radiography Principles

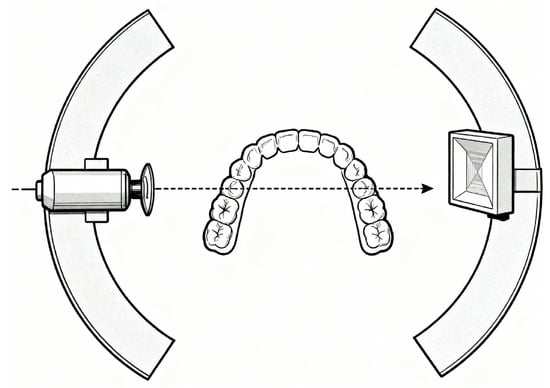

Panoramic radiography operates through the synchronised rotation of the X-ray tube and detector around the patient’s head, capturing the curved dental arch in a single exposure. The X-ray beam is collimated into a narrow vertical slit that sweeps across the jaws as the system rotates, producing a three-dimensional, horseshoe-shaped focal trough—typically 15–30 mm thick—where structures appear sharp and areas outside become blurred [11,12]. Acquisition takes about 12–20 s, and modern digital systems use solid-state sensors for immediate image capture and processing. Figure 2 illustrates the rotating X-ray source, detector, and focal trough geometry during the scan.

Figure 2.

Panoramic radiographic acquisition geometry showing synchronous rotation of X-ray source and detector around the patient, capturing the curved dental arch within a focal trough and producing spatially varying projections.

The projection geometry is highly complex: each image column corresponds to a distinct instantaneous projection angle, creating spatially variable magnification (typically 1.2–1.3×) across the image. X-ray attenuation follows the Beer–Lambert law, so each detector value represents cumulative attenuation along the curved ray path without spatial depth information—a key limitation for three-dimensional reconstruction [13].

Common artefacts further complicate image interpretation. Dense structures outside the focal trough can produce ghost images, while incorrect head positioning causes distortions such as tooth widening or the “smile/frown” curvature of the occlusal plane. Patient movement introduces motion blur, and limited spatial resolution (two to five line pairs per millimetre) restricts fine detail visibility. Superimposition of soft tissues and air spaces over dental anatomy adds further ambiguity, as panoramic imaging lacks the volumetric separation capability of CBCT [14].

2.2. Mathematical Foundations of 3D Reconstruction

Three-dimensional reconstruction from projections traditionally relies on geometric triangulation, where corresponding points across multiple views define intersecting rays that localise spatial positions. In single-view reconstruction, this geometric constraint is absent, requiring statistical inference to estimate the most probable 3D configuration from a single observation using anatomical priors. Shape-from-shading provides limited cues, as image intensities reflect cumulative X-ray attenuation related to tissue density and thickness, but identical intensities can result from multiple density–thickness combinations or overlapping structures [15].

Panoramic projection maps 3D points to image coordinates based on continuously changing source–detector geometry during rotation. The Beer–Lambert law describes the transmitted intensity of a ray passing through tissue with a spatially varying attenuation coefficient along path length L:

where is the incident intensity. Reconstruction therefore requires inverting this relationship to recover the spatial distribution of . Modern deep learning methods bypass explicit inversion, learning this mapping directly from data. Implicit neural representations parameterise 3D structure as continuous functions mapping coordinates to density values, efficiently capturing curved anatomical geometries [16].

Single-view reconstruction remains mathematically ill-posed: infinitely many 3D structures can yield identical 2D projections, and small input variations can cause large output differences. Regularisation—via prior knowledge or learned data distributions—constrains solutions to anatomically plausible configurations. Deep models achieve this implicitly through statistical learning, though performance depends heavily on dataset quality and representativeness. Ultimately, the feasibility of single-view reconstruction depends on whether these embedded assumptions adequately compensate for the inherent information loss of projection [17].

2.3. Relevant Anatomical Considerations

The dental arches form parabolic or horseshoe-shaped curves, with substantial inter-individual variation. In panoramic projection, varying distances from the centre of rotation cause position-dependent magnification and distortion. The mandibular canal, which contains neurovascular structures, follows a variable course across individuals, posing both clinical and reconstruction challenges [18].

The maxilla is anatomically more complex due to its proximity to the nasal cavity, maxillary sinuses, and orbital floor. Air-filled regions adjacent to dense bone generate high-contrast boundaries, while overlapping soft tissues—tongue, palate, and airway—add ambiguity to bone delineation. Tooth anatomy further complicates reconstruction through intricate geometry and material heterogeneity: enamel is the most radiopaque tissue, dentine exhibits intermediate attenuation, and pulp chambers appear radiolucent. The periodontal ligament space, only 0.1–0.3 mm wide, approaches the resolution limits of panoramic imaging [11,19].

Tooth orientation and bone morphology introduce additional variability. Anterior teeth incline labially, posterior teeth tilt mesially, and cortical bone appears as high-intensity bands overlying less dense trabecular bone. Bone density varies regionally—denser in the mandibular symphysis and thinner in the maxilla [20].

Age-related resorption following tooth loss reduces alveolar dimensions, while pathological changes such as periodontal bone loss, cysts, or tumours alter attenuation characteristics. Metallic restorations (amalgam, crowns, implants) produce bright streak artefacts that obscure adjacent anatomy and distort projection geometry, complicating accurate reconstruction [21].

3. Search Strategy

A comprehensive and systematic search strategy was developed to capture the full scope of contemporary research in three-dimensional reconstruction relevant to dental imaging and computational modelling. To ensure broad coverage across medical, technical, and interdisciplinary fields, multiple academic databases and scholarly platforms were consulted. The primary sources included PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, Google Scholar, Nature Portfolio, Elsevier, ACL Anthology, SpringerOpen, arXiv, IEEE Xplore, and MDPI. These repositories were selected to encompass the biomedical literature, engineering and computer vision research, open-access scientific outputs, and preprints representing the latest methodological developments.

The search strategy included general terminology related to 3D reconstruction technology, with the core search terms including the following:

- Panoramic radiography OR panoramic X-ray.

- Three-dimensional reconstruction OR 3D teeth reconstruction OR 3D reconstruction in dentistry OR teeth reconstruction.

- Cone-beam computed tomography.

- Radiography or panoramic.

- Dental implants.

- Deep learning dentistry OR artificial intelligence dental.

- Neural implicit panoramic.

- Holography OR holography dentistry.

- Augmented reality in dentistry.

- AI fairness biomedicine OR fairness medical AI.

- FDA AI/ML medical devices.

- Bias medical image analysis.

- European Data Protection Board AI personal data.

No restrictions on publication date were applied. Searches included all available records up to November 2025.

3.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

This review included peer-reviewed scientific publications from journals, conference proceedings, symposia, and preprint servers. Eligible studies were required to address single-view 3D reconstruction of dental structures (teeth, jaws, oral cavity) derived primarily from panoramic radiographs. Priority was given to studies evaluating deep learning frameworks (including CNNs, transformers, GANs, and neural implicit representations), as well as those exploring holographic or mixed-reality applications in dentistry. Works involving paired PX–CBCT datasets, synthetic panoramic projections, or methodological and algorithmic developments relevant to 3D reconstruction technologies were also included.

Excluded were non-dental applications, multi-view or intraoral scan methods without a panoramic focus, microscopic or cellular imaging, materials science unrelated to reconstruction, studies lacking quantitative validation (e.g., no metrics such as IoU, Dice, or Chamfer distance), and pure simulation papers without real PX evaluation or without specifying the underlying technology.

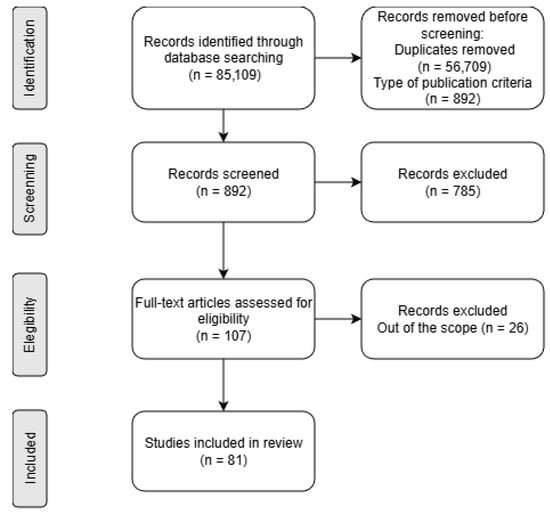

3.2. Data Collection and Extraction Process

All retrieved articles were initially evaluated by title and abstract. If these provided sufficient indication that a study met the review objectives, a full-text assessment was conducted. In addition to methodological relevance, several qualitative indicators were considered, including publication date, journal scope, study design, and overall scientific robustness. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion. The complete selection pathway, from identification to inclusion, is summarised in the flow diagram shows in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

A PRISMA flow diagram of the systematic review.

4. Review of 3D Reconstruction Methods

4.1. Classical and Geometric Approaches

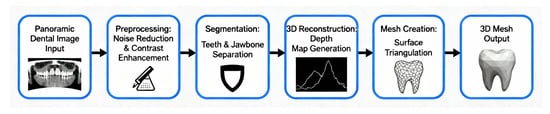

Early three-dimensional dental reconstruction methods relied on geometric constraints and statistical shape models derived from anatomical databases. These models represented 3D structures as deformations of a mean template using principal component analysis, capturing typical crown shapes, root curvatures, and proportional relationships across tooth classes. Reconstruction was achieved by fitting deformable templates to 2D panoramic images through parameter adjustment to match contours and intensity distributions [7,22]. Figure 4 shows a standard single-view 3D reconstruction pipeline, from panoramic input to AI-driven mesh generation and volumetric output.

Figure 4.

Single-view 3D reconstruction from panoramic radiographs.

Template fitting extended this approach through libraries of 3D tooth and jaw models registered to panoramic radiographs by feature correspondence. Landmarks identified in 2D images were matched to 3D template points and aligned using iterative closest point algorithms or thin-plate spline warping [23]. Interpolation-based methods reconstructed 3D surfaces from segmented tooth boundaries by extrusion or rotation under symmetry assumptions. Dental arch geometry was approximated via spline interpolation of tooth positions, and root trajectories were estimated through bilateral symmetry [12,24].

Despite their innovation, these classical methods faced major limitations. Statistical shape models lacked patient-specific accuracy, template libraries could not encompass full anatomical diversity, and interpolation relied on oversimplified smoothness assumptions. Extensive manual intervention—landmarking, template selection, and tuning—further limited clinical practicality [14].

4.2. Deep Learning Architectures

Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) revolutionised three-dimensional dental reconstruction by learning feature representations directly from paired data rather than relying on hand-crafted geometric models. Early CNN-based approaches treated reconstruction as a regression task, predicting 3D coordinates, voxel occupancy, or depth maps from panoramic inputs. Hierarchical convolutions extracted progressively complex features—from edges and textures to complete tooth morphologies—enabling the mapping between two- and three-dimensional representations [25].

Encoder–decoder architectures became dominant, in which encoders compressed spatial information through convolution and pooling, while decoders reconstructed volumetric outputs via transposed convolutions or interpolation. Skip connections preserved fine spatial detail lost during compression [16].

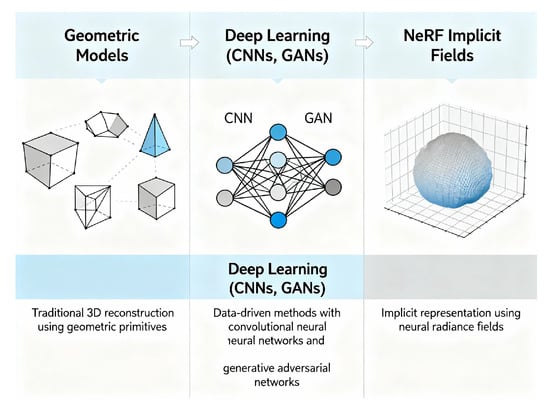

Generative adversarial networks (GANs) introduced a complementary paradigm: a generator synthesises 3D reconstructions from panoramic inputs, while a discriminator distinguishes them from real CBCT scans. This adversarial learning drives anatomically realistic reconstructions, with the discriminator acting as an implicit quality evaluator [17]. Figure 5 summarises the evolution of single-view dental 3D reconstruction—from geometric and statistical models to CNN, GAN, and neural implicit representations such as NeRF and occupancy networks.

Figure 5.

Evolution of single-view dental 3D reconstruction methods.

Recently, transformer architectures have emerged as powerful alternatives to purely convolutional designs. Self-attention enables long-range dependency modelling, capturing relationships between distant structures such as opposing molars or jaw landmarks. Vision Transformers (ViTs) process panoramic patches through attention layers, while hybrid CNN–ViT architectures combine local pattern extraction with global context modelling [26].

These deep learning approaches outperform classical methods, achieving structural similarity indices of 0.7–0.8 and mean surface errors of 1–2 mm. However, their performance depends on large paired panoramic–CBCT datasets, which remain limited, and generalisation to unseen anatomical or imaging variations continues to pose challenges [27].

4.3. Neural Implicit Representations

Implicit neural representations have transformed three-dimensional reconstruction by modelling geometry as continuous functions rather than discrete voxel grids or meshes. These methods parameterise a neural network that maps 3D coordinates to occupancy probability, signed distance, or density, enabling continuous, resolution-independent reconstruction [28].

Signed distance functions (SDFs) predict, for each point, the minimum distance to the nearest surface, with the sign indicating whether the point is inside or outside. The zero level set defines the surface, providing smooth topology and efficient extraction via marching cubes [29]. Occupancy networks similarly predict binary inside–outside values, with separate models often representing teeth, mandible, and maxilla, trained for consistency with 3D ground-truth data from panoramic inputs [30].

Neural radiance fields (NeRFs), adapted from novel view synthesis, model spatial coordinates as density and colour values under volumetric rendering principles consistent with X-ray attenuation physics. The Beer–Lambert law provides explicit physical grounding; the NeBLa model integrates this attenuation law into its architecture, comparing predicted and observed intensities to improve generalisation and reduce data requirements [13].

Implicit representations offer continuous, memory-efficient geometry capable of capturing curved dental arches [31], but they remain computationally intensive. Each spatial query requires a network evaluation, training is sensitive to initialisation, and the resulting surfaces may appear overly smooth, missing fine anatomical details [29].

4.4. State-of-the-Art Reconstruction Frameworks

The rapid development of deep learning techniques has significantly influenced modern dental imaging, providing new opportunities for automated diagnosis, image enhancement, and three-dimensional reconstruction. By learning hierarchical and context-aware representations from radiographic data, deep neural networks can extract clinically relevant information from modalities such as cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT), panoramic radiographs, and intraoral scans with high accuracy and efficiency. Recent advances, particularly in convolutional and transformer-based architectures, have enabled improved modelling of dental structures, disease detection, and cross-modality integration, thereby reducing manual intervention and inter-operator variability. This subsection presents an overview of representative deep learning frameworks and their applications in dental imaging, outlining their methodological foundations, improvements over conventional approaches, and remaining challenges in clinical deployment.

4.4.1. Occudent: Neural Implicit Functions for Teeth Reconstruction

Occudent [10] presents a novel framework for reconstructing three-dimensional tooth models from standard two-dimensional panoramic radiographs (PX) using neural implicit functions, marking the first approach to generating accurate 3D dental structures directly from real clinical images. Unlike previous methods such as X2Teeth and Oral-3D, which relied on synthetic PX generated from CBCT projections, Occudent was trained and evaluated on real radiographs, ensuring greater clinical relevance. The framework consists of two components: a multi-label 2D segmentation network based on an enhanced UNet++ that identifies and classifies all 32 tooth classes, and a 3D reconstruction network built on an implicit representation that predicts an occupancy function to determine whether each sampled 3D point lies inside or outside the tooth volume.

The condition vector (c) combines a tooth class embedding and a tooth patch embedding, integrated via the Conditional eXcitation (CX) module proposed by the authors. CX fuses these embeddings—encoding both the 2D patch and class identity—by extending the Squeeze-and-Excitation mechanism to modulate latent features according to conditional vectors, enabling more precise and class-aware 3D shape generation.

Evaluation on paired PX–CBCT datasets demonstrates Occudent’s superiority over state-of-the-art methods (3D-R2N2, Pix2Vox, PSGN, X2Teeth, OccNet) across all major metrics, including volumetric IoU (0.651), Chamfer-L1 distance (0.298), normal consistency, and reconstruction precision. The model effectively reproduces detailed dental anatomy, including root structures, while benefiting from the memory efficiency and continuity advantages of implicit shape representations over voxel-based approaches.

In conclusion, Occudent advances clinical and educational applications by enabling accurate, robust, and scalable 3D dental reconstructions from widely available 2D imaging. Its architecture provides a foundation for future developments in multimodal integration and neural optimisation, promoting greater precision and personalisation in digital dentistry.

4.4.2. NeBLa: Neural Beer–Lambert for Oral Structures

Park et al. (2024) introduced NeBLa (Neural Beer–Lambert), a physics-inspired neural framework for three-dimensional reconstruction of oral and dental structures from a single real panoramic radiograph (PX) [13]. Unlike previous methods such as X2CT-GAN and Oral-3D, which rely on synthetic PX–CBCT pairs or geometric priors, NeBLa reconstructs full volumetric CBCT-like data directly from unpaired real radiographs. Its central innovation combines X-ray attenuation physics, described by the Beer–Lambert law, with neural implicit modelling. The transmitted intensity of an X-ray beam through tissue with attenuation coefficient along path (l) is given by

where is the incident intensity, I the detected intensity, the local attenuation coefficient, and l the path length of the X-ray beam. In discrete form, this relationship is approximated as

This physics-based simulation links 2D radiographic appearance to the underlying 3D structure, enabling the network to learn spatially consistent volumetric features. Trained on CBCT volumes and unpaired real PX images, NeBLa achieved a Dice coefficient 15% higher and perceptual error 30% lower than X2CT-GAN, with PSNR and SSIM improvements of 10% and 6%, respectively. Qualitatively, it produced smoother, anatomically coherent reconstructions of crowns, roots, and jawbone structures.

By embedding the Beer–Lambert model into a neural rendering framework, NeBLa establishes a new paradigm for radiograph-based 3D dental reconstruction—offering a low-dose, data-efficient, and clinically viable alternative to CBCT. It demonstrates the synergy between physical modelling and neural implicit representations, paving the way for non-invasive, cost-effective, real-time 3D visualisation in dental and medical imaging.

4.4.3. ViT-NeBLa (Vision Transformer-Based Neural Beer–Lambert)

ViT-NeBLa [15] introduces a state-of-the-art framework for single-view three-dimensional reconstruction of oral anatomy from panoramic radiographs (PX). Building on the previously proposed NeBLa framework, it integrates Vision Transformers (ViT) with implicit neural representations guided by the Beer–Lambert law (Equation (3)), ensuring that simulated panoramic projections (SimPX) accurately model X-ray attenuation.

The ViT-NeBLa architecture consists of four main modules: (1) a hybrid ViT–CNN feature extractor that combines global contextual encoding with local texture refinement; (2) a learnable multi-resolution hash positional encoder for compact spatial embeddings; (3) a NeRF-inspired implicit field predictor that estimates voxel-level density distributions; and (4) a 3D U-Net refinement module that enhances structural continuity and fine anatomical detail. A horseshoe-shaped ray-sampling scheme confines computation to the jaw region, reducing sampling density from 200 to 96 points per ray and halving processing time compared to NeBLa, without loss of accuracy.

Trained on an expanded dataset of more than 600 real and synthetic PX–CBCT pairs, ViT-NeBLa achieved approximately 1.3 dB higher PSNR, 3% higher SSIM, 7–8% higher Dice coefficient, and about 10% lower perceptual error (LPIPS) compared to the original NeBLa. Qualitative results further demonstrate smoother and more anatomically coherent reconstructions of teeth, alveolar bone, and mandibular regions.

By uniting global transformer-based feature encoding with a physics-informed Beer–Lambert formulation, ViT-NeBLa represents a major advancement in radiograph-based 3D reconstruction, achieving greater accuracy and efficiency than previ- ous approaches.

4.4.4. X2Teeth and Single-Image Reconstruction Systems

The X2Teeth framework [32] introduces a convolutional neural network (ConvNet) for reconstructing complete three-dimensional dental structures directly from a single panoramic radiograph (PX). Using an encoder–decoder architecture, a two-dimensional encoder extracts panoramic features, while a decoder predicts the corresponding three-dimensional voxel-based tooth geometries. Unlike previous object-level reconstruction methods, X2Teeth simultaneously reconstructs all teeth within the full oral cavity at high resolution.

The method decomposes the task into two core steps:

- Teeth localisation—dividing the panoramic image into patches centred on individual teeth, enabling patch-based training focused on local context.

- Shape estimation—predicting a 3D voxel grid or mesh for each tooth patch, combining local coherence with global structure through joint optimisation and multi- class segmentation.

Model training minimises a composite loss combining 2D segmentation loss and 3D reconstruction loss, both formulated using the Dice coefficient to measure overlap between predicted and ground-truth volumes.

Experimental evaluation demonstrated that X2Teeth substantially outperforms generic single-view reconstruction models such as 3D-R2N2 and DeepRetrieval. Quantitatively, it achieved a mean Intersection-over-Union (IoU) of , exceeding those of 3D-R2N2 by and DeepRetrieval by , while attaining a per-tooth segmentation IoU of and reconstruction IoU of . Qualitative analysis confirmed that X2Teeth recovers anatomically coherent crown and root morphology with smooth surface continuity and accurate interproximal spacing.

Overall, X2Teeth is the first end-to-end learning framework to reconstruct anatomically consistent 3D dental structures from a single panoramic radiograph, establishing a foundation for radiation-free 3D modelling applicable in diagnosis, orthodontic planning, and digital dental education.

4.4.5. PX2Tooth

PX2Tooth [33] builds on the foundations established by X2Teeth by introducing a two-stage deep learning framework for accurate three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction of dental structures from a single panoramic radiograph (PX). This approach replaces voxel-based volumetric prediction with direct 3D point cloud generation, reducing memory consumption and enabling finer geometric detail. The architecture explicitly separates the tasks of tooth localisation and 3D geometry synthesis, making the reconstruction process more interpretable and anatomically constrained.

The framework comprises two key modules:

- PXSegNet—a U-Net-based segmentation network that performs per-tooth classification into 32 categories according to the FDI numbering system.

- TGNet—a point-based generator that reconstructs 3D tooth geometries using segmentation priors and panoramic image features.

PXSegNet is optimised using two complementary segmentation losses: the Metric Boundary (MB) Loss and the Unbalanced (UB) Loss, which, respectively, improve edge precision and class balance.

The Metric Boundary Loss is defined as

where C is the number of tooth classes, N is the number of pixels, is the ground =0truth label of pixel i for class c, and is the predicted probability for the same pixel and class.

This loss emphasises boundary regions by maximising overlap between predicted and true edges for each class.

The Unbalanced Loss further adjusts training focus towards classes with fewer samples, mitigating imbalance by down-weighting easy examples:

where is a focusing parameter that reduces the weight of well-classified samples.

Together, these two losses enhance segmentation stability and fine-grained boundary accuracy.

In the reconstruction stage, TGNet generates tooth point clouds from localised segmentation patches using a Prior Fusion Module (PFM) that aligns 2D image features with 3D spatial embeddings.

Training uses a Reconstruction Loss (RT Loss) based on bidirectional point set distances:

where A and B are the predicted and ground-truth point clouds and m and n are the number of points in each cloud.

This loss enforces geometric consistency by minimising the average squared distance between corresponding points across both sets.

Experimental validation on 499 paired panoramic–CBCT scans demonstrates that PX2Tooth achieves a mean Intersection-over-Union (IoU) of , outperforming previous models such as X2Teeth and Occudent by up to . Qualitative evaluations further show that PX2Tooth reconstructs smoother, topologically consistent tooth morphologies, with improved continuity at root boundaries compared to voxel-based methods.

Overall, PX2Tooth represents a major advance in single-image 3D dental reconstruction, offering a radiation-free, data-efficient, and clinically viable approach for digital dentistry and orthodontic applications.

4.4.6. Oral-3D/Oral-3Dv2

The Oral-3D framework [34] introduces a two-stage generative adversarial network (GAN)-based method for reconstructing the three-dimensional bone structure of the oral cavity from a single panoramic radiograph (PX), requiring only minimal prior information about dental arch geometry. Unlike cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT), which provides complete 3D data but involves higher radiation exposure and greater equipment requirements, Oral-3D uses deep learning to infer depth-related anatomical information from 2D images.

In the first stage, a back-projection module uses a generator–discriminator pair to map 2D panoramic images to flattened 3D density volumes, employing the least-squares GAN (LSGAN) formulation and stabilised by the following objectives:

where G is the generator, D the discriminator, x the input PX image, and y the ground-truth 3D volume. A voxel-wise reconstruction term further constrains the generator output to match the real CBCT-derived target:

The second stage, a deformation module, warps the flattened 3D volume along the estimated dental arch to restore the natural curvature of the mandible and maxilla. Experimental results on CBCT-derived datasets show that Oral-3D outperforms 3D-R2N2 and Pix2Vox, achieving 7–10% higher PSNR, 8–9% higher SSIM, and up to 13% improvement in Dice coefficient. The reconstructed 3D models accurately represent dental arches, alveolar bone density, and tooth morphology, providing a radiation-free and cost-effective alternative to CBCT.

The improved Oral-3Dv2 framework [9] addresses the data dependency and efficiency limitations of the original model through a physics-informed implicit neural representation. Its Neural X-ray Field (NeXF) architecture learns continuous 3D density distributions directly from real panoramic images and known X-ray trajectories, eliminating the need for voxel-based supervision and reducing computational complexity from cubic to quadratic order. Incorporating the Beer–Lambert attenuation law and a dynamic ray-sampling strategy enhances anatomical accuracy and surface smoothness. Empirical results show SSIM gains of about five points and overall reconstruction improvements exceeding 7%, establishing Oral-3Dv2 as a more data-efficient, physically consistent, and clinically applicable framework for single-image 3D dental reconstruction.

4.4.7. Multi-View and Sequential Approaches

While most state-of-the-art frameworks for three-dimensional reconstruction from panoramic radiographs rely on a single projection, recent developments highlight the potential of integrating additional imaging sources and temporal information. Multi-view and sequential approaches extend single-image models such as Occudent, NeBLa, and X2Teeth by combining panoramic radiographs with intraoral photographs, surface scans, or longitudinal image sequences. This fusion enhances geometric completeness and surface accuracy, and it also enables temporally consistent reconstructions suitable for treatment monitoring and dynamic anatomical analysis. The following subsections review current methodologies for cross-view fusion, temporal regularisation, and feature-level correspondence across heterogeneous dental image modalities.

Multi-View Fusion of Panoramic and Intraoral Images

The integration of multimodal dental imaging—particularly the fusion of panoramic radiographs with intraoral scans—offers a promising approach to improving the geometric accuracy and completeness of 3D dental reconstruction. Panoramic radiographs provide a comprehensive anatomical overview but lack the local surface detail captured by intraoral photographs or 3D surface scans. Recent multimodal frameworks demonstrate that combining these complementary modalities enhances reconstruction by jointly leveraging volumetric and surface cues.

Liu et al. [35] proposed Deep Dental Multimodal Fusion, a neural architecture that encodes cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) volumes and intraoral meshes into a shared latent space, enabling bidirectional translation and surface refinement through feature-level fusion. This approach improves reconstruction accuracy and surface precision while reducing dependence on high-radiation CBCT imaging.

Jang et al. [36] developed a fully automatic pipeline for registering full-arch intraoral scans with CBCT data using hierarchical alignment and learned correspondence descriptors. Although both frameworks use CBCT as the volumetric modality, their principles can be extended to combine panoramic radiographs with intraoral images, reducing reliance on CBCT acquisition.

Sequential and Temporally Consistent Reconstruction

Temporal consistency is essential in dental image analysis, particularly for longitudinal monitoring of orthodontic or periodontal changes. Sequential registration ensures that morphological variations—such as tooth movement, bone remodelling, and soft tissue resorption—are accurately represented across imaging sessions.

Ogawa et al. [37] developed a framework for registering panoramic radiographs acquired at different time points. Their method combines global non-linear normalisation of the dental arch using fourth-order Lagrange polynomial interpolation with local alignment based on normalised cross-correlation, compensating for geometric distortions caused by patient repositioning. Quantitative evaluation uses logarithmic intensity difference maps to visualise localised bone density changes over time.

Rodríguez et al. [38] extended this approach by introducing a longitudinal intraoral ultrasound registration framework to track soft and hard tissue changes across multiple sessions. The method integrates rigid and deformable registration guided by intensity-based similarity metrics and temporal smoothness constraints, ensuring consistent spatial alignment and reliable assessment of progressive dental changes while preserving temporal and anatomical coherence.

Cross-View Feature Matching and Co-Training

Cross-view feature matching and co-training have become key strategies for integrating heterogeneous dental modalities—panoramic radiographs, intraoral photographs, and 3D mesh models—into unified reconstruction and analysis frameworks. Luo et al. [39] introduced the Dual-View Co-Training Network (DVCTNet), which uses dual-stream pre-training to jointly optimise panoramic and tooth-level representations, and a Gated Cross-View Attention mechanism for dynamic fusion between global and local features. Emulating clinical reasoning that combines panoramic overview with local inspection, this approach achieved up to +4.4% improvement in AP75 accuracy, demonstrating the effectiveness of cross-view co-training in dental analysis.

To improve representation learning with limited data, Almalki and Latecki [40] applied self-supervised masked image modelling (SimMIM and UM-MAE) to panoramic radiographs, achieving 13.4% higher tooth detection accuracy and 12.8% better restoration segmentation. Their results show that contrastive and self-supervised learning foster shared latent embeddings that support cross-modal generalisation.

At the 3D level, Zhao et al. [41] proposed a Two-Stream Graph Convolutional Network that fuses geometric and attribute features via shared multilayer perceptrons and attention-based graph operations, aligning 3D shape and surface texture between intraoral scans and other modalities. Similarly, Hsung et al. [42] developed an image-to-geometry registration pipeline that maps 2D intraoral photographs onto virtual 3D tooth models, enabling visually enhanced reconstructions without manual alignment.

Mohamed et al. [25] extended this multi-view paradigm to 2D dental imagery using an EfficientNet-based encoder to synthesise volumetric 3D reconstructions from multiple 2D projections, improving geometric completeness and depth estimation.

Collectively, these studies demonstrate that cross-view feature projection and contrastive co-training in a shared embedding space significantly enhance robustness and generalisation across heterogeneous dental data sources. By leveraging complementary 2D and 3D cues, such frameworks enable anatomically consistent, data-efficient, and scalable solutions for multimodal dental reconstruction and diagnostic modelling.

4.4.8. Comparative Analysis and Selection Criteria

Occudent

The Occudent framework is trained on a single-centre paired panoramic–CBCT dataset acquired using one scanner family, with patients drawn from a limited regional population. The original paper does not provide a detailed breakdown of age, sex, or ethnicity distributions. Reported results rely on internal train, validation, and test splits of this dataset; no true external validation on an independent site or different hardware is described, which increases the risk that performance is partly driven by scanner-specific intensity characteristics and the local case mix. Consequently, there is a plausible risk of overfitting to the acquisition protocol, device vendor, and prevalent dental conditions at the source institution, so accuracy may degrade when applied to populations with different craniofacial morphology, disease prevalence, or imaging workflows [10,43].

NeBLa and ViT-NeBLa

NeBLa and ViT-NeBLa combine CBCT-derived simulated panoramic images (SimPX) from a single CBCT dataset with real panoramic radiographs from a limited number of clinical sites, again with limited reporting of detailed patient demographics. Although the unpaired training scheme reduces the need for matched PX–CBCT pairs, both studies primarily evaluate performance on data from the same institutions and scanner types used to construct SimPX, and they do not report formal external validation on fully independent cohorts. This design can embed biases related to specific CBCT protocols, reconstruction kernels, and regional patient characteristics; domain shifts in beam geometry, reconstruction software, or population anatomy at deployment sites may therefore cause larger than expected decreases in reconstruction fidelity [13,43].

X2Teeth

X2Teeth is trained on a curated set of matched panoramic radiographs and CBCT volumes from a single hospital, with patients primarily undergoing comprehensive dental treatment. However, the publication provides only coarse age statistics and no ethnicity information. Validation is performed using internal cross-validation or held-out subsets from the same acquisition pipeline, with no multi-centre external test set, which limits conclusions about generalisability beyond the original scanner configuration and referral patterns. As a voxel-based ConvNet, X2Teeth can overfit to scanner-dependent noise patterns, grey-level distributions, and occlusal plane positioning; models tuned to this narrow domain may perform suboptimally on images from other vendors, paediatric cohorts, or public health screening programmes with different disease spectra [32,43].

PX2Tooth

PX2Tooth uses 499 paired panoramic–CBCT cases, collected from a limited set of clinical sources. The authors note variability in dental conditions but do not provide detailed demographic stratification. Performance is evaluated on an internal test split from the same pool of scans; there is no dedicated external validation cohort from a different institution, region or scanner, so potential overfitting to local imaging physics and annotation style remains a concern. As PX2Tooth replaces voxel grids with point clouds conditioned on segmentation outputs, it may be particularly sensitive to scanner-specific contrast, resolution and artefact profiles that affect segmentation quality. This could introduce systematic performance degradation in under-represented patient groups or on devices with different pixel sizes and exposure protocols [33,43].

Oral-3D and Oral-3Dv2

Oral-3D and its successor Oral-3Dv2 are trained on paired panoramic–CBCT datasets focused on oral bone reconstruction, typically sourced from one or a few academic centres, with limited reporting of demographic diversity and inclusion of atypical anatomies. Validation experiments use internal splits and cross-validation; to date, there is no published large-scale external validation across multiple scanners or international sites, which limits the ability to assess robustness under varying acquisition geometries, metallic artefact burdens, and ethnic craniofacial patterns. Given their GAN-based architecture, these models may inadvertently model scanner- and site-specific texture statistics as “realistic”, increasing the risk that reconstructions appear plausible but are anatomically inaccurate when applied to populations or devices not represented in the training data [43,44].

Within the scope of this paper, Occudent and NeBLa received more detailed mathematical treatment because they exemplify two complementary, theoretically grounded paradigms that are directly relevant to the HoloDent3D concept: class-conditioned neural implicit shape functions for tooth-level occupancy (Occudent) and physics-informed volumetric reconstruction guided by the Beer–Lambert law (NeBLa and ViT-NeBLa). These frameworks explicitly encode the panoramic projection geometry and X-ray attenuation model, allowing their assumptions, limitations, and possible extensions to be analysed in a principled manner and integrated with the reconstruction module of HoloDent3D. In contrast, voxel-based ConvNets such as X2Teeth, hybrid point-cloud methods like PX2Tooth, and GAN-based systems such as Oral-3D and Oral-3Dv2 primarily rely on empirical optimisation and task-specific loss design. While methodologically important, their mathematical foundations are closer to standard deep learning practice and thus require less extensive formal exposition in the context of this concept paper. A comparison of the previously mentioned and meticulously described models is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparative model characteristics. The symbol “↑” indicates an increase or improvement of the corresponding metric compared to the referenced baseline method.

Selection Criteria and Suitability for HoloDent3D

For HoloDent3D, the main requirements are as follows: (i) robust single-view 3D reconstruction from real clinical panoramic images, (ii) compatibility with heterogeneous scanners, and (iii) efficiency suitable for near real-time holographic rendering. Under these constraints, physics-informed implicit methods such as NeBLa and ViT-NeBLa are particularly attractive because they embed the Beer–Lambert projection model explicitly, which improves data efficiency and provides a clear pathway to adapt the learned field to different scanner geometries via calibration rather than full retraining. Occudent and PX2Tooth offer strong tooth-level geometry and high IoU on paired datasets, making them promising candidates for detailed dental surface reconstruction.

Consequently, a hybrid strategy appears most suitable: using a NeBLa/ViT-NeBLa as the primary jaw and bone-level reconstruction engine, augmented by Occudent or PX2Tooth-style tooth-specific modules for high-resolution crown and root surfaces in regions of interest. This combination aligns well with HoloDent3D’s goal, which targets interactive holographic exploration rather than submillimetre surgical navigation, and balances reconstruction fidelity, data availability, and computational cost in a way that is realistic for deployment on GPU-equipped workstations connected to holographic fan displays.

It is also important to note that although methods such as NeBLa and ViT-NeBLa are highly promising, reconstructing a full 3D anatomy from a single panoramic radiograph remains extremely ambitious. Depth, bone density, and the anatomical precision of both bone and teeth all push the limits of what is feasible without CBCT, so robust validation is essential. Moreover, the quality and diversity of the training dataset are critical. Simulation-based approaches, such as SimPX, rely on a sufficiently representative CBCT pool to achieve clinically reliable generalisation. Computational demands also remain a major factor, as implicit volumetric and ray-tracing-based models (NeBLa/ViT-NeBLa) are intensive during both training and inference. For practical, real-time clinical deployment, substantial optimisation will be necessary, including improved sampling strategies, quantisation, and possibly lightweight model variants. Finally, even the most accurate reconstructions may still contain errors, so clear clinical boundaries must be established to determine when the reconstructed 3D models are acceptable for treatment planning (e.g., implants, orthodontics) and when CBCT remains mandatory.

5. Review of Holography and Mixed Reality in Dentistry

Holography and mixed reality (MR) have become transformative technologies in digital dentistry, enabling the integration of virtual three-dimensional (3D) data with the clinical environment. Early medical applications of holography [45] demonstrated its potential as a non-contact, high-resolution imaging method for visualising anatomical structures with exceptional spatial accuracy. Building on this foundation, dentistry increasingly employs augmented reality (AR) and MR systems to enhance diagnosis, treatment planning, and education.

Recent studies confirm the benefits of immersive visualisation. Lin et al. [46] reported that AR and VR training systems improve procedural precision and learning efficiency through real-time feedback and simulation, while Rosu et al. [47] achieved submillimetre accuracy (), 30% faster workflows, and 37% fewer errors in AR-assisted prosthodontic and implant procedures compared to conventional methods. Despite challenges such as hardware cost, calibration complexity, and lack of standardisation, holography and MR represent a decisive step towards precision-guided, patient-specific, and interactive dentistry.

Dolega-Dolegowski et al. [48] presented a proof of concept using holographic and AR technology to visualise internal dental root structures for educational purposes with the Microsoft HoloLens 2 platform (Figure 6 (image created in Perplexity AI Pro)). The workflow involved model creation in Autodesk Maya, export to Unity 3D for interactive scripting, and gesture-based control via HoloLens sensors, allowing real-scale holographic visualisation of teeth. Users could manipulate models, explore internal canals, and inspect root anatomy from multiple perspectives, linking theoretical knowledge with spatial perception.

Figure 6.

HoloLens-based mixed-reality workflow for interactive 3D visualisation and manipulation of patient-specific dental anatomy.

A pilot study involving 12 participants (6 dental students and 6 clinicians) evaluated eight holographic models representing different Vertucci canal types. Results showed high user satisfaction—91% found the system superior to conventional 2D or screen-based 3D renderings—and reported improved understanding of spatial relationships within root canal systems. The authors concluded that holography and AR provide effective educational tools, enhancing perception of complex anatomical structures and supporting manual skill development and 3D reasoning in endodontic practice.

Talaat et al. [49] evaluated the reliability of a holographic augmented reality (AR) system for three-dimensional (3D) superimposition of digital dental models using the Microsoft HoloLens, compared with a conventional computer-based application. The study included 20 orthodontic patients (mean age years) treated with rapid maxillary expansion using Hyrax palatal expanders. Pre- and post-treatment digital maxillary models were acquired with a high-resolution Ortho Insight 3D laser scanner (20 m resolution) and imported into Ortho Mechanics Sequential Analyzer (OMSA) software for 3D superimposition based on midpalatal raphe landmarks.

Two analysis methods were compared: conventional 2D computer visualisation and holographic AR display through HoloLens. Three anatomical landmarks were placed along the midpalatal raphe—one at the distal end of the incisive papilla and two posteriorly—by the same operator to avoid inter-operator variability. Accuracy and consistency were assessed using Dahlberg’s measurement error, Bland–Altman limits of agreement, and the concordance correlation coefficient (CCC).

Results showed that HoloLens-based superimposition achieved accuracy statistically equivalent to computer-based analysis, with mean differences ranging from −0.18 mm to +0.17 mm and no significant bias. Intra-operator reliability was also high, comparable to that of traditional software. The holographic 3D display provided enhanced depth perception and intuitive spatial manipulation without loss of precision, confirming its potential for orthodontic analysis. Identified limitations included the limited computational power and memory of the HoloLens, potential rendering delays for complex models, and the need for further software optimisation.

Akulauskas et al. [50] investigated the feasibility and accuracy of using augmented reality (AR) for dental implant surgery with the Microsoft HoloLens 2 headset. The study aimed to determine whether AR-based navigation could achieve precision comparable to conventional computer-guided implant systems and to identify limitations of current hardware and calibration procedures.

Dynamic navigation systems such as Navident and X-Guide, while highly accurate, require surgeons to look away from the operative field to view external monitors, disrupting workflow. In contrast, AR technology allows navigation data to be displayed directly within the operator’s field of vision.

A custom 3D-printed dental model and a “”-shaped calibration marker were used as spatial references for holographic alignment. Calibration and alignment tests were conducted under static (headset fixed) and dynamic (headset worn) conditions using four reference points, with accuracy assessed by comparing predefined virtual and physical positions.

Overall distance deviations averaged , with precision around , and statistically significant variation across calibration points. Angular deviation between virtual and real models averaged , influenced by tracking stability and marker recognition. Virtual model trueness was in dynamic mode and in static mode, with significant differences confirmed using the Kruskal–Wallis and Dunn’s post hoc tests ().

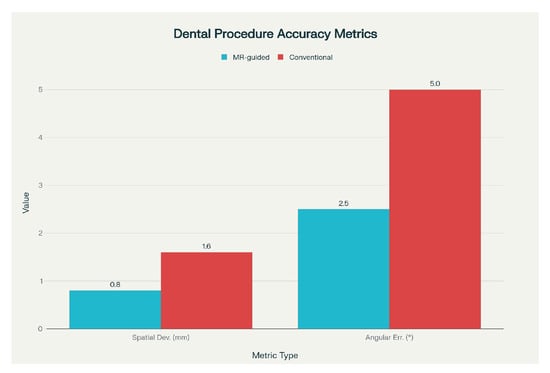

Figure 7 summarises accuracy data from multiple studies comparing mixed-reality (MR)-guided dental procedures with conventional methods, highlighting spatial deviations (mm) and angular errors (°) that demonstrate the precision gains achieved through MR guidance.

Figure 7.

Comparison of spatial deviation and angular error metrics for mixed-reality—guided versus conventional dental procedures.

Although AR currently achieves lower precision than established dynamic navigation systems (typically positional accuracy and angular deviation), the authors conclude that it holds strong potential as an educational or auxiliary tool in dental implantology. With advancements in hardware, calibration, and tracking algorithms, AR may achieve the precision required for clinical use.

Xue et al. [51] conducted a proof-of-concept study to assess whether mixed reality (MR) could enhance scaling and root planing (SRP) outcomes and improve patient understanding. The workflow involved acquiring intraoral scans and cone-beam CT data from 10 patients with advanced periodontitis. These datasets were fused into detailed three-dimensional models of teeth, gingiva, and alveolar bone, which were rendered in Microsoft HoloLens 2 for interactive manipulation (resizing, rotation, cross-sectional segmentation) and intuitive clinician–patient communication.

MR-guided SRP resulted in significant clinical improvements after eight weeks. Mean probing pocket depth (PPD) decreased from to , and clinical attachment loss (CAL) from to (). The plaque index (PI) declined from to , and bleeding on probing (BOP) from 78.92% to 36.40%. For sites with PPD , PPD and CAL reductions were and , respectively, with a 43.86% decrease in BOP.

The authors emphasised MR’s advantages in visualising subgingival regions, reducing dependence on tactile feedback, and improving instrumentation accuracy. However, they noted limitations including equipment cost, hygiene challenges, limited training, operator fatigue, and high power consumption. With continued hardware development and cost reduction, MR could be integrated into periodontal therapy, telemedicine, and training applications. Future randomised studies are recommended to quantitatively compare MR-assisted and conventional SRP for long-term efficacy.

Zhang et al. [52] conducted a randomised controlled split-mouth clinical trial to assess the short-term efficacy of mixed-reality holographic-imaging-based scaling and root planing (MR-SRP) compared with conventional scaling and root planing (C-SRP) in patients with generalised stage III periodontitis. The prospective, single-blinded study included 20 patients and integrated cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) and intraoral scans to generate interactive 3D periodontal models displayed via HoloLens 2, allowing real-time manipulation of anatomical structures during SRP.

Both treatments resulted in significant clinical improvement at three months (), with no statistically significant differences between groups. Mean probing pocket depth (PPD) reduction was for MR-SRP and for C-SRP, while clinical attachment loss (CAL) improved by and , respectively (). The proportion of healed sites (transition from PPD with bleeding on probing (BOP) to PPD without BOP) reached 75.68% for MR-SRP and 72.69% for C-SRP, reflecting an approximate 4% relative improvement. Non-molar teeth showed higher healing rates than molars (80.44% vs. 52.01%), highlighting anatomical challenges in multirooted regions.

Reported limitations included the small sample size, short 3-month follow-up, lack of long-term evaluation, and high equipment cost. MR registration was not directly overlaid on patients during procedures to prevent visual interference, and CBCT radiation exposure remains a concern for routine therapy. The authors recommend larger multi-centre studies and software–hardware optimisation to enhance performance and cost-efficiency.

In conclusion, MR-SRP demonstrated slightly superior short-term healing outcomes compared with conventional SRP and shows potential as an effective adjunctive tool for managing severe periodontitis.

Fan et al. [53] introduced a mixed reality (MR)-guided dental implant navigation system (MR-DINS) designed to improve implant placement accuracy and efficiency by aligning preoperative plans with the surgical field in real time. The system integrates a HoloLens 2 device with an optical tracking system (NDI Polaris Spectra) and custom registration tools to align virtual 3D models reconstructed from CBCT data with the physical patient phantom.

The architecture combines optical tracking with MR visualisation using three core algorithms: HoloLens—tracker registration, image—phantom registration, and surgical drill calibration. Each uses a homogeneous transformation matrix to express coordinate transformations between virtual and physical reference frames:

where is the rotation matrix and the translation vector. For any spatial point P, the relationship between coordinate systems and is defined as

Transformations are estimated using the Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) registration algorithm, which minimises squared distances between corresponding fiducial points.

Experiments on 30 patient models with 102 implants showed a mean coronal deviation of , apical deviation of , and angular deviation of . Mean fiducial registration error (FRE), target registration error (TRE), drill calibration error (DCE), and HoloLens registration error (HRE) were all below 1 mm, confirming submillimetre calibration precision. Performance matched that of dynamic navigation systems and was 30–40% more accurate than freehand implant placement while eliminating hand–eye coordination issues typical of previous AR/MR systems.

In conclusion, the MR-DINS framework achieved high accuracy and usability in dental implant navigation, supported by rigorous mathematical modelling and validated through phantom experiments.

Grün et al. [54] introduced a smartphone-based augmented reality (AR) navigation system for guiding dental implant placement, offering a low-cost and accessible alternative to conventional computer-assisted implant surgery (CAIS) systems, which require expensive hardware and complex calibration. The study aimed to determine whether consumer-grade mobile technology could deliver clinically acceptable accuracy for implant navigation.

The AR workflow integrated cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT), intraoral scans, facial photographs, and occlusal data into a fully digital patient model. Treatment planning was performed in Romexis 6.0.1.812 software, and virtual implant positions were exported in Filmbox (FBX) format for use in a custom AR application developed for a Samsung Galaxy S22 smartphone. Using the Vuforia engine for spatial tracking, the app overlaid implant trajectories directly on the patient’s anatomy via a holographic display, eliminating the need for additional navigation equipment.

The system was validated on a 3D-printed phantom and subsequently applied in a clinical case involving a 52-year-old male requiring replacement of four anterior maxillary teeth. Four BEGO S-Line implants () were placed following the AR-guided plan. Postoperative CBCT comparison showed a mean apical deviation of and an angular deviation of , with three implants within clinically acceptable tolerance.

Compared with freehand placement, the AR-assisted workflow improved spatial accuracy by approximately 50–60%. Additional advantages include affordability, integration with standard digital workflows, and usability on widely available consumer devices. Reported limitations include sensitivity to lighting conditions, ergonomic challenges of handheld operation, and dependence on stable tracking for reliable overlay.

Grad et al. [55] investigated the use of Microsoft HoloLens-based augmented reality (AR) and three-dimensional (3D) printed anatomical tooth models in dental education, focusing on the accuracy of occlusal anatomy reconstruction during restorative procedures. The study compared AR holograms with physical 3D-printed models to evaluate accuracy, efficiency, and user experience in teaching dental morphology. Anatomical models of three molars were reconstructed from CBCT scans using InVesalius and Autodesk Meshmixer, then either 3D printed or displayed holographically via HoloLens.

Thirty-two participants performed cavity fillings under three conditions: without reference (M1), with a 3D-printed model (M2), and with an AR holographic model (M3). Accuracy was quantified using the maximum Hausdorff distance () between reconstructed and reference models. Significant differences were observed (), with the lowest mean for 3D-printed models (630 m), followed by AR (760 m) and no reference (850 m). The AR system enabled faster task completion and easier spatial orientation, but users reported reduced comfort due to the headset’s weight and incompatibility with magnification loupes.

In subjective evaluation, 78% of participants preferred 3D-printed models for comfort and effectiveness, while AR was viewed as innovative but less ergonomic. The authors conclude that lighter AR hardware and higher display resolution could improve comfort and precision, promoting broader adoption of holographic teaching aids in dental curricula.

While the reviewed studies consistently demonstrate improvements in spatial understanding, task efficiency, and user satisfaction, a critical evidence gap remains. Current evaluations rely predominantly on subjective perception metrics, workflow timing, and landmark accuracy, yet none of the included works directly measure patient-centred or clinical outcomes such as treatment success rates, patient comprehension of procedures, long-term oral health behaviour, or overall quality of care. Evidence from the broader AR/VR/MR dental literature suggests potential for increased patient comprehension and satisfaction, and possibly reduced anxiety; however, these findings are largely based on self-reported impressions rather than objective clinical endpoints [51,56,57]. Therefore, although holography and mixed reality appear highly promising for education, planning, and navigation, further research is needed to determine whether enhanced visualisation truly translates into better treatment outcomes, improved safety, and sustained patient benefit in real-world dental practice.

6. Conceptual Framework of the HoloDent3D Model

HoloDent3D currently exists as a conceptual framework at TRL 2-3. No physical prototype has been implemented. This section presents the theoretical architecture and planned development pathway.

6.1. Concept and Objectives

The HoloDent3D model offers a conceptual framework for an advanced dental imaging system that integrates artificial intelligence, computer vision, and holographic visualisation to redefine how clinicians interpret, explain, and communicate diagnostic information. Its central aim is to transform conventional two-dimensional orthopantomogram (OPG) radiographs into dynamic three-dimensional holographic reconstructions of the jaw and dental structures, viewable in real time and manipulable through intuitive, gesture-based interaction. This integration of AI-driven 3D reconstruction and holographic display seeks to bridge the gap between complex radiographic data and human spatial perception, creating a more natural, immersive, and informative diagnostic experience.

At the core of the concept is an automated reconstruction pipeline that uses deep learning algorithms to identify and segment anatomical features from standard panoramic dental X-rays. These features are then used to generate accurate 3D representations that preserve the anatomical fidelity of teeth, bone, and surrounding structures. In doing so, the system directly addresses a critical limitation of current imaging practices: the compression of three-dimensional information into a two-dimensional format, which often obscures spatial relationships and complicates diagnosis.

The intended benefits of the HoloDent3D concept span both clinical and communicative dimensions. For dental professionals, holographic visualisation supports improved diagnostic precision, clearer identification of pathological conditions, and enhanced treatment planning by enabling real-time manipulation—rotation, zooming, and cross-sectional viewing—of reconstructed structures. For patients, the system provides an accessible, visually engaging understanding of their oral health, making it easier to comprehend the nature of medical findings, proposed interventions, and expected outcomes. This transparency is expected to foster stronger dentist–patient trust, greater involvement in treatment decisions, and improved adherence to recommended care. Figure 8 (image created in PerplexityPro) presents different clinical scenarios for mixed reality applications: (a) diagnostic consultation with holographic imaging, (b) treatment planning with 3D reconstruction overlays, (c) patient education using interactive anatomical visualisations, and (d) intraoperative surgical guidance with AR-assisted precision.

Figure 8.

Clinical use cases of augmented and mixed reality in dentistry, including holographic diagnostics, 3D treatment planning, patient education, and AR-guided procedures.

A further objective is to ensure accessibility and practical integration into existing dental workflows. Unlike conventional 3D imaging solutions that require costly cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) scanners or specialised augmented reality setups, the HoloDent3D model builds upon routinely acquired OPG data and cost-efficient holographic fan display technology. This combination allows for affordable implementation without disrupting standard diagnostic procedures.

In essence, HoloDent3D envisions a transformative yet feasible step towards intelligent, interactive dental imaging. By merging AI-driven reconstruction with holographic visualisation and gesture-based control, the concept aims to enhance diagnostic clarity, optimise patient engagement, and lay the foundation for a new generation of human-centred, data-informed dental care.

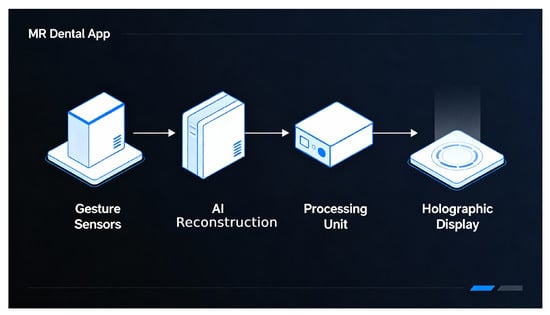

6.2. System Concept and Architecture

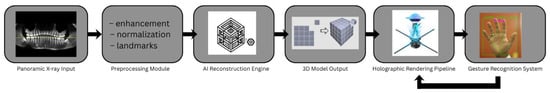

The HoloDent3D system architecture is designed as a modular, multi-stage processing pipeline that transforms conventional two-dimensional orthopantomogram radiographs into interactive three-dimensional holographic representations. Figure 9 illustrates the high-level system architecture of HoloDent3D as a horizontal pipeline. Arrows indicate the flow of information, including a feedback loop from gesture recognition back to the rendering pipeline. Only major functional blocks are shown; internal model details, device specifications, and sensor/training information are intentionally omitted to focus on overall system flow.

Figure 9.

Modular HoloDent3D system pipeline showing data flow from panoramic input through AI-based 3D reconstruction to holographic rendering and gesture-driven interaction.

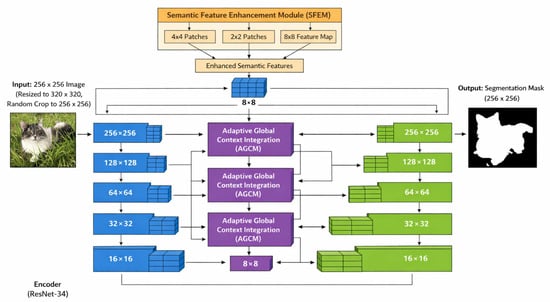

In this work, we adopt the U-Net architecture introduced in [58] as the backbone for our segmentation module. Among the architectures we evaluated, this variant delivered the most reliable and consistent performance for the type of structural delineation required in our setting. Its design consists of a U-shaped encoder–decoder network with a ResNet-34 encoder and a five-stage decoder, providing a well-balanced compromise between representational capacity and computational efficiency.

The encoder follows the standard ResNet-34 configuration, while the decoder comprises five decoding layers, each containing two convolutional layers followed by batch normalisation and ReLU activation. Input images are resized to (other datasets) and then randomly cropped to for training.

The enhanced U-Net described in [58] introduces two key architectural modules:

- Semantic Feature Enhancement Module (SFEM): Attached to the top of the final encoding layer (which outputs an feature map). It processes the features through three parallel branches operating on patch sizes of , and the full resolution, thereby capturing richer multi-scale semantic context and increasing feature discriminability.

- Adaptive Global Context Module (AGCM): Replaces standard skip connections. At each scale, it integrates information from the corresponding encoder layer, the previous decoder layer, and the SFEM output. This selective fusion mechanism filters background noise and injects global contextual cues, improving boundary coherence and segmentation stability.

Given the nature of our task—where accurate regional separation and structural consistency are critical—this enhanced U-Net configuration (shown on Figure 10) provides a strong architectural fit. We therefore implement this specific variant in our system without modification, using it as the primary segmentation engine within the HoloDent3D pipeline.

Figure 10.

Enhanced U-Net architecture: encoder features are refined via AGCM for skip connections, deepest features are enriched by SFEM and injected into all decoder stages, and each decoder stage includes an auxiliary prediction head [58].

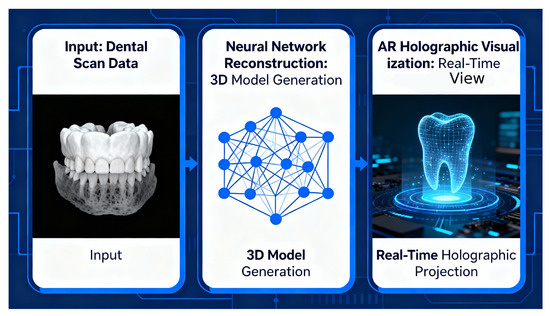

The proposed pipeline consists of three primary stages: input acquisition and preprocessing, AI-driven 3D reconstruction, and holographic visualisation with gesture-based interaction. Figure 11 presents the three-stage architecture of the HoloDent3D system: Stage 1 illustrates input acquisition and preprocessing of panoramic images; Stage 2 shows AI-driven 3D reconstruction with neural network components; and Stage 3 depicts holographic visualisation combined with a gesture-based interaction interface for clinical use.

Figure 11.

Three-stage HoloDent3D pipeline from panoramic input through neural 3D model reconstruction to real-time holographic dental visualisation.

Stage 1: Input acquisition and preprocessing. The pipeline begins with the acquisition of a standard orthopantomogram (OPG) radiograph, which serves as the sole imaging input. Orthopantomograms are routinely captured in dental practices using panoramic X-ray systems and provide comprehensive coverage of dental and maxillofacial structures in a single two-dimensional projection.

During preprocessing, the acquired OPG image undergoes quality enhancement and normalisation to optimise subsequent analysis. This includes contrast adjustment, noise reduction, and standardisation of image dimensions and resolution. Advanced image processing algorithms are used to identify and segment key anatomical landmarks, including tooth boundaries, root structures, bone margins, and potential pathological regions. The preprocessing module also performs coordinate system transformation to prepare the 2D image data for three-dimensional reconstruction.

Stage 2: AI-driven 3D reconstruction module. The core innovation of the HoloDent3D system lies in its reconstruction module, which uses artificial intelligence and computer vision techniques to transform the preprocessed 2D orthopantomogram into a detailed three-dimensional model of the jaw and dental structures.

The reconstruction process employs deep learning algorithms trained on datasets containing paired 2D radiographs and corresponding 3D anatomical models. Specifically, the system utilises generative algorithms capable of learning the complex mapping between two-dimensional radiographic projections and three-dimensional anatomical geometry. These algorithms analyse intensity distributions, texture patterns, and spatial relationships within the OPG image to infer depth information and reconstruct volumetric representations of teeth, roots, and bone structures.

The reconstruction module focuses on recognising critical anatomical features, including tooth contours, root morphology, cortical and trabecular bone patterns, and the mandibular canal. Through interpolation and depth estimation techniques, the system generates a three-dimensional mesh model that preserves anatomical accuracy and spatial relationships between structures. The module is designed to identify and accurately represent pathological conditions such as caries, periapical lesions, bone defects, and impacted teeth.To ensure clinical validity, the reconstruction algorithms incorporate anatomical constraints and prior knowledge of dental and maxillofacial morphology. The system calibrates and optimises the generative models to achieve high fidelity in representing fine anatomical details, including individual tooth surfaces, root configurations, and bone density variations.

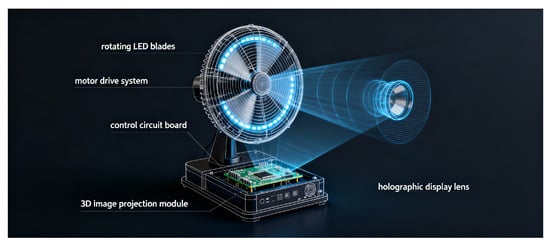

Stage 3: Holographic visualisation and interaction. After reconstruction, the 3D model is processed for holographic display using a holographic fan device that generates volumetric visualisations through high-speed rotation of LED arrays. The holographic fan technology creates the illusion of a three-dimensional object suspended in mid-air, viewable from multiple angles without the need for specialised viewing equipment such as VR headsets or 3D glasses.

The visualisation module converts the 3D mesh model into a format compatible with the holographic display hardware, optimising rendering parameters such as resolution, refresh rate, and viewing angles to ensure clear and stable holographic projection. The system uses microprocessors to synchronise the rotation of the LED fan with the display of sequential image frames, generating a persistent volumetric representation. Figure 12 illustrates demonstrates the working principle of a holographic fan display, highlighting the LED arrays, the rotational mechanism, and the creation of volumetric images through rapidly spinning light sources.

Figure 12.

Holographic fan display principle showing high-speed rotating LED blades synchronised with 3D image projection to generate a volumetric dental hologram.