Abstract

(1) Background: With the continuous development of intelligent education, classroom behavior recognition has become increasingly important in teaching evaluation and learning analytics. In response to challenges such as occlusion, scale differences, and fine-grained behavior recognition in complex classroom environments, this paper proposes an improved YOLOv11-ASV detection framework; (2) Methods: This framework introduces the Adaptive Spatial Pyramid Network (ASPN) based on YOLOv11, enhancing contextual modeling capabilities through block-level channel partitioning and multi-scale feature fusion mechanisms. Additionally, VanillaNet is adopted as the backbone network to improve the global semantic feature representation; (3) Conclusions: Experimental results show that on our self-built classroom behavior dataset (ClassroomDatasets), YOLOv11-ASV achieves 81.5% mAP50 and 62.1% mAP50–95, improving by 1.6% and 2.9%, respectively, compared to the baseline model. Notably, performance shows significant improvement in recognizing behavior classes such as “reading” and “writing” which are often confused. The experimental results validate the effectiveness of the YOLOv11-ASV model in improving behavior recognition accuracy and robustness in complex classroom scenarios, providing reliable technical support for the practical application of smart classroom systems.

1. Introduction

With the rapid growth of computer vision, object detection has been widely applied in fields such as education, transportation, and healthcare. Classroom behavior recognition, a key element of smart education, has gained increasing attention [1]. Students’ behaviors in class, such as raising hands, reading, writing, looking down, or using mobile phones, not only reflect their concentration and participation but also provide an important basis for teaching evaluation and classroom management [2]. The traditional manual observation method is inefficient and difficult to ensure objectivity and accuracy in large-scale scenarios. In contrast, the intelligent recognition method based on deep learning, with its end-to-end learning framework and powerful feature modeling capabilities, can achieve efficient and accurate classroom behavior detection in complex environments, providing strong support for the development of smart education.

In recent years, classroom behavior recognition has gradually become a hotspot in intelligent education research. Some studies have attempted to combine deep learning with object detection methods, such as convolutional neural network-based detection frameworks that automatically extract multi-level features and improve recognition accuracy to some extent. Unlike image classification, detection frameworks enable both localization and recognition, suiting multi-person, overlapping actions. Two-stage detectors like Faster R-CNN [3] achieve high accuracy but with heavy computation.

Among mainstream single-stage detectors, the YOLO series is widely used due to its end-to-end structure and high inference speed [4,5]. YOLOv5, in particular, excels in terms of lightweight and engineering applications and has been widely adopted in various object detection tasks [6]. The subsequent YOLOv8 further optimizes the network structure and training strategies, achieving higher accuracy in general detection tasks [7]. However, when these methods are directly applied to classroom behavior recognition, they still have some shortcomings. On one hand, classroom scenarios often involve challenges such as occlusion, significant scale differences, and diverse postures, leading to poor model performance in complex backgrounds; on the other hand, the fine-grained differences between behavior categories (such as “writing” and “reading”) are difficult to distinguish, and YOLOv5 and YOLOv8 still struggle with performance at higher IoU (Intersection over Union) thresholds; YOLOv11 [8] enhances feature fusion and sample two key modules: C3k2 (Cross-Stage Partial network with kernel-size 2) and C2PSA (Channel-to-Point Spatial Attention). DETR [9] introduces Transformers for global context modeling but suffers from slow convergence and high cost. Despite progress, challenges remain in handling severe occlusion, multi-scale coexistence, and fine-grained behavior distinction.

Addressing scale variation in student behaviors requires effective multi-level feature fusion. Lin et al. introduced FPN [10] to strengthen small-target representation via a top-down pyramid, while Ghiasi et al. proposed NAS-FPN [11], using neural search to design feature pyramids automatically. Attention mechanisms also enhance contextual awareness: CBAM [12] combines channel and spatial attention to suppress noise; ECA [13] models lightweight channel dependencies; PKINet [14] extracts multi-scale context with convolutions; and the DASI module in HCF-Net [15] improves integration via grouped selective fusion. These approaches provide valuable insights for distinguishing fine-grained classroom behaviors. Nevertheless, a fundamental characteristic of prevalent feature fusion paradigms (e.g., FPN, PANet, BiFPN) is their operation on a feature-map-wise basis. These methods treat feature maps as monolithic entities during fusion, applying a uniform strategy to aggregate information across all channels. This paradigm implicitly assumes a homogeneous distribution of semantic concepts across the channel dimension, which may not hold true in practice. Consequently, the fusion process can suffer from semantic-level interference, where features representing disparate visual concepts (e.g., detailed local textures versus global structural contexts) are indiscriminately combined. This can lead to the suppression of discriminative, fine-grained signals that are critical for distinguishing between semantically similar behavior categories, thereby limiting recognition performance in complex scenarios.

Problem Formulation

This work addresses the problem of automated classroom behavior recognition from fixed camera perspectives. The task requires detecting all visible students in a single classroom image and classifying each individual’s ongoing behavior into predefined categories. Formally, the system accepts as input a JPEG-format image captured from a stationary classroom camera, which is standardized to a resolution of 640 × 640 pixels during processing. For every student present in the image, the model must output both precise spatial localization (bounding box coordinates) and behavioral classification. The solution must contend with characteristic classroom challenges: frequent occlusions between closely seated students, substantial variation in student scale due to camera perspective, and subtle visual distinctions between semantically related behaviors such as reading versus writing. Model performance is principally evaluated through the mean Average Precision (mAP) metric, with particular attention to the stringent mAP50–95 criterion that demands high localization accuracy, which is essential for reliable behavioral differentiation.

To address the formulated problem, particularly its requirements for robustness to occlusion, scale variation, and fine-grained distinction, this paper proposes an improved model, YOLOv11-ASV, based on the YOLOv11 framework. This model introduces a novel Adaptive Spatial Pyramid Network (ASPN) alongside VanillaNet to enable a more granular and adaptive feature fusion process, thereby achieving robust detection in complex classroom environments. The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

- (1)

- The proposed ASPN module: An adaptive spatial pyramid network (ASPN) is designed, which can selectively interact between multi-scale features, effectively enhancing the context modeling ability for fine-grained classroom behaviors.

- (2)

- The development of the improved YOLOv11-ASV model: ASPN and VanillaNet are introduced into the YOLOv11 framework to enhance feature fusion and global modeling capabilities, thereby achieving more accurate detection of multi-scale and fine-grained behaviors in complex classroom scenarios.

- (3)

- Experimental results further validate the effectiveness of the proposed method: Specifically, YOLOv11-ASV achieves 81.5% mAP50 on the self-built ClassroomDatasets, improving by 1.6% over the baseline YOLOv11; mAP50–95 improves by 2.9%; and the average improvement of mAP50–95 for complex behavior categories (such as “reading,” “writing,” and “leaning over the table”) reaches 4.3%. These results fully demonstrate that YOLOv11-ASV not only has strong robustness and generalization ability for classroom behavior recognition tasks, but also shows higher detection accuracy in fine-grained category differentiation, with promising practical applications and value.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Baseline: YOLOv11 Framework

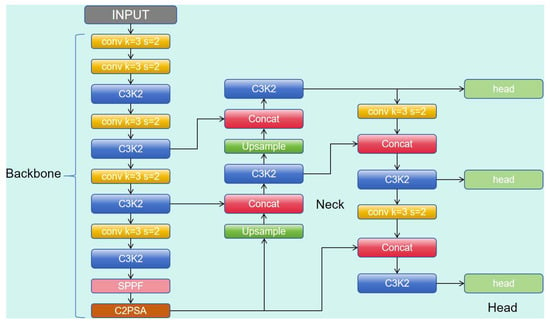

YOLOv11 serves as the baseline for our model, a high-performance detector built on a Backbone-Neck-Head architecture. As shown in Figure 1, the Backbone, inspired by CSPNet, efficiently extracts hierarchical features. The Neck adopts an enhanced FPN-PAN structure, incorporating C3k2 and C2PSA modules for effective multi-scale feature fusion. Specifically, C3k2 facilitates efficient cross-stage feature propagation, while C2PSA improves feature selectivity through a channel-to-point attention mechanism. The decoupled Head independently handles classification and bounding box regression, with optimization guided by a Task-Aligned Assigner during training.

Figure 1.

The structure diagram of YOLOv11.

While the baseline performs robustly for general detection tasks, it faces limitations in addressing the unique challenges of classroom environments, such as distinguishing fine-grained posture variations. The standard fusion mechanisms lack the adaptive context modeling required to effectively differentiate highly similar behaviors. To overcome these challenges, our YOLOv11-ASV model introduces key innovations in both the Backbone and Neck, as outlined in the following sections.

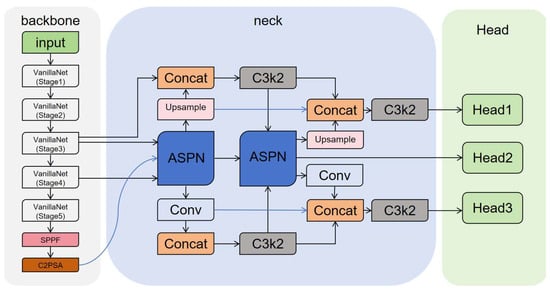

2.2. YOLOv11-ASV Improved Algorithm Model

The overall structure of YOLOv11-ASV is shown in Figure 2. In the Neck part, YOLOv11-ASV designs the ASPN module. This module is inspired by pyramid-style feature fusion structures, but introduces multi-scale convolution branches and context modeling mechanisms to achieve adaptive enhancement of features at different scales. While ensuring a lightweight design, ASPN strengthens the interaction between high-level semantics and low-level details, improving detection performance for occluded scenes and small target actions. Additionally, within ASPN, feature channels are divided into blocks, and selective feature aggregation is applied to address the semantic and detail mismatch in traditional feature fusion. The core operation divides multi-layer features into several sub-channel blocks, aligning and weighting low- and high-level features within each block, and finally concatenating them to form a global feature representation. This mechanism explicitly balances fine-grained context and detail representation, thereby improving the ability to distinguish similar posture categories in classroom behavior recognition.

Figure 2.

The overall framework of YOLOv11-ASV.

In the Backbone part, the model uses VanillaNet-5 as the feature extraction network. VanillaNet-5 is based on a minimalist structure of layer-by-layer convolution stacking, avoiding complex attention or residual branches, thus ensuring computational efficiency while providing more discriminative deep semantic features. The introduction of this Backbone enhances the model’s ability to express action boundaries that are ambiguous, as well as fine-grained posture differences.

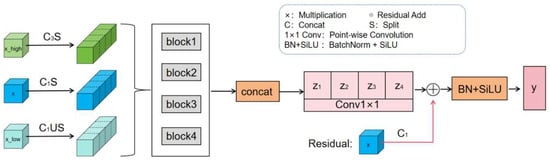

2.3. Adaptive Spatial Pyramid Network

As shown in Figure 3, the proposed Adaptive Spatial Pyramid Network module is the core innovation in the Neck part of the YOLOv11-ASV model. Its design goal is to enhance multi-scale feature fusion and context modeling capabilities to better address the challenges of diverse behaviors, significant scale variations, and fine-grained action recognition in classroom scenarios.

Figure 3.

Illustration of the ASPN module structure.

The design of ASPN is inspired by the typical pyramid feature fusion structure but introduces chunk-wise splitting and selective fusion mechanisms. Multi-layer features are divided into several channel sub-blocks, and within each sub-block, low-level details and high-level semantics are aligned and fused. ASPN extends this idea to a pyramid structure with multi-scale convolution branches, achieving a balanced modeling of context and details.

In terms of module structure, let the aligned multi-layer features be {F_low, F_mid, F_high}, which are divided into K sub-blocks along the channel dimension:

Within each sub-block, selective interaction is performed:

where φ(·) is the selective fusion function, and its specific implementation is detailed in the following sections. After all sub-blocks are fused, they are concatenated along the channel dimension and reconstructed through convolution:

2.3.1. Block Internal Functionality

Each sub-block executes the selective fusion function from Equation (2). This function dynamically aggregates the multi-level input features , , and through a gating mechanism.

The implementation of is as follows: first, the three input features are concatenated. A context vector is then generated by applying Global Average Pooling (GAP) to this concatenation. This vector is fed into a small network (a fully-connected layer followed by a Softmax activation) to produce a set of adaptive weights , which represent the importance of each feature level. The final fused output for the block is the element-wise weighted sum:

This design enables each sub-block to autonomously calibrate its reliance on low-level details versus high-level semantics, which is critical for distinguishing fine-grained behavioral categories.

Each sub-block corresponds to an independent block (block 1-block K). Inside the block, the input sub-feature extracts contextual information under different receptive fields through multi-scale convolution branches (e.g., 3 × 3, 5 × 5 dilated convolutions, etc.). The results from each branch are aggregated within the block and then compressed to channels via a 1 × 1 convolution.

This allows each block to independently learn the “context–detail” balance that best fits its sub-channel: blocks containing small targets tend to focus on low-level details, while blocks with complex postures or background interference rely more on high-level semantics. Finally, the outputs of all blocks are concatenated along the channel dimension to form the overall enhanced feature.

2.3.2. Multi-Scale Convolution Branches

The processing of each block can be formalized as:

where represents the corresponding convolution operation. This design explicitly expands the effective receptive field, enhancing robustness to targets of different scales.

2.3.3. Fusion and Residual Enhancement

The outputs of all blocks are concatenated and then integrated through a 1 × 1 convolution, followed by adding the aligned residual features X. The final output is obtained through batch normalization (BN) and SiLU activation:

where σ represents the SiLU activation function. The above process forms a closed loop of chunking → independent modeling → concatenation and fusion → residual enhancement.

2.3.4. Module Configuration

The ASPN module was configured with four channel blocks (K = 4). Within each block, multi-scale contextual information was extracted using parallel convolutional branches with kernel sizes of 3, 5, and 7. The 5 × 5 and 7 × 7 convolutions employed dilation rates of 2 and 3 respectively to expand the receptive field. Input feature maps to the ASPN at the P3, P4, and P5 levels had channel dimensions of 128, 256, and 512 correspondingly. The selective fusion function φ(·) generated adaptive weights through a compact network comprising global average pooling, a fully-connected layer with 16 hidden units, and a Softmax output layer.

2.3.5. Method Advantages

The advantages of ASPN are as follows: Fine-grained modeling: Independent processing at the block level allows each channel sub-block to flexibly select high-level semantics or low-level details. Multi-scale enhancement: Parallel convolution branches expand the receptive field, improving robustness to small targets and occluded scenes. Adaptive aggregation: Sub-blocks can learn optimal fusion strategies, improving the ability to distinguish complex actions. Lightweight and scalable: The number of blocks K and the scale of the branches are adjustable, facilitating a trade-off between accuracy and efficiency.

2.4. Collaboration Between VanillaNet and ASPN

This paper combines VanillaNet-5 with the ASPN module to improve performance in classroom behavior recognition. This choice is strategically designed for the classroom environment. VanillaNet’s minimalist, sequential architecture, devoid of complex branches, enhances the clarity of feature maps and ensures more direct gradient flow. This design is particularly beneficial for addressing motion blur and accurately localizing actions under partial occlusion, common challenges in classroom videos. Additionally, its structural re-parameterization strikes an optimal balance, offering rich non-linearity during training for robust feature learning, while seamlessly merging into a highly efficient network for real-time inference, an essential requirement for smart classroom applications.

The VanillaNet-5 backbone was employed with a width multiplier of 1.0, resulting in an initial channel size of 32. This configuration provides a foundational feature hierarchy where the channel dimensions progressively double across its five stages, effectively balancing representational capacity with computational efficiency for the task.

The core concept of the VanillaNet deep training strategy is to modify the network structure in the early stages of training. Unlike traditional methods, where only a single convolution layer is trained, VanillaNet optimizes two convolution layers and the activation function between them at the start of training. As the training process progresses, the activation function gradually degenerates into an identity mapping through a weighted mechanism. After training, due to the identity transformation property of the activation function, the two convolution layers can be merged into one using a structural parameterization method, thereby improving the model’s inference speed without sacrificing performance.

Specifically, for any activation function, it is linearly combined with an identity mapping, defined as follows:

where λ is a hyperparameter used to balance the degree of non-linearity. Let e and E represent the current training epoch and total training epochs, respectively, then λ = e/E. Therefore, in the early stages of training (e ≈ 0), λ ≈ 0, and the modified activation function A′(x) approximates the original function A(x), showing strong non-linearity. As the training nears completion (e ≈ E), λ ≈ 1, and A′(x) approaches the identity mapping x, effectively removing the non-linearity between the two convolution layers and creating the conditions for layer merging.

Since simple network structures are often limited by insufficient non-linear expressiveness, VanillaNet employs a parallel function stacking strategy to enhance the non-linearity of a single activation layer, thereby significantly improving the non-linear expression ability of each activation function. This approach constructs a more powerful composite activation function by weighted summing multiple base activation functions, formally defined as:

where n represents the number of stacked functions, and ai and bi are the scale weights and biases of the i-th activation function, respectively. This structure significantly enhances the nonlinear fitting capability of the activation function.

To further enhance its approximation ability, VanillaNet draws inspiration from BNET, enabling the activation function of this series to utilize local neighborhood information of the input features to learn global context. Specifically, for a particular position (h, w, c) on the input feature map, the improved activation function is defined as:

In experiments, VanillaNet demonstrated strong detection for actions with large movements and clear boundaries, such as standing or raising hands. For feature extraction of these actions, VanillaNet effectively extracts key features and enables accurate detection. However, for similar behaviors that are easy to confuse, such as reading, bowing the head, and writing, its simplified structure limits feature representation, reducing its ability to distinguish subtle differences and impacting performance.

To address this issue, we combine VanillaNet-5 with the ASPN module. ASPN’s multi-scale contextual enhancement and chunked feature fusion overcome VanillaNet’s limitations in fine-grained behavior modeling. It dynamically weights features at different scales, improving recognition of similar actions, such as bowing the head and writing, in complex classroom scenarios. This combination retains VanillaNet’s efficiency while enhancing feature representation for high accuracy. VanillaNet-5 performs feature downsampling and channel multiplication at multiple stages using a “1 × 1 convolution + MaxPool” structure, generating multi-scale feature maps for ASPN. Through adaptive weighting, ASPN integrates low-level details and high-level semantic features, further enhancing the network’s ability to perceive and distinguish fine-grained classroom behaviors. During inference, VanillaNet-5 increases feature dimensions at each stage via channel multiplication, capturing more detailed information, while ASPN fuses multi-scale features effectively. This optimization enhances YOLOv11’s detection accuracy for fine-grained actions and improves robustness in complex classroom environments, further advancing its potential in classroom behavior recognition tasks.

3. Results

3.1. Datasets

All experiments in this study were conducted on the Featurize cloud GPU platform, with hardware configured as NVIDIA RTX 4090 (24GB VRAM). The software environment includes Python 3.11.8, PyTorch 2.2.2, and TensorFlow 2.16.1, with Docker 26.1.0 used for environment encapsulation and dependency management. Both training and inference were implemented using the Ultralytics YOLOv11 framework (v8.3.9) on PyTorch, with CUDA version 12.1, ensuring reproducibility and computational efficiency of the experiments.

This study uses a self-built dataset, ClassroomDatasets, for experimentation. The dataset was constructed to reflect realistic educational settings and ensure diversity.

Data Collection: The dataset was compiled from video recordings of multiple authentic university classrooms. To ensure diversity and realism, the data encompassed a variety of conditions: (1) Lighting: included both natural daylight from windows and standard indoor fluorescent lighting, covering different times of the day; (2) Camera Perspectives: comprised frontal and side views to capture student postures from different angles, simulating common monitoring scenarios. The original videos were recorded at a resolution of 1920 × 1080 pixels. These videos were subsequently sampled at a rate of 1 frame per second (1 FPS) to ensure sufficient temporal discontinuity and avoid redundant images, resulting in a final set of 1140 unique images for annotation.

Annotation Process: A team of three annotators performed the labeling tasks following a standardized annotation protocol. A detailed annotation guideline was established to ensure consistency and accuracy. Key criteria for distinguishing similar behaviors included: ‘Reading’: Defined by the clear presence of a book or tablet held in the student’s hands. ‘Writing’: Required the visible presence of a pen or pencil and a notebook or paper on the desk. ‘Bowing the head’ vs. ‘Leaning over the table’: Distinguished primarily by the degree of torso inclination and the proximity of the head to the desk surface, with the latter indicating a more pronounced forward bend [16,17].

Bounding boxes were tightly drawn around the entire body of each student. To quantitatively assess labeling consistency, a subset of 100 images was independently annotated by all three annotators. The average Inter-Annotator Agreement (IAA), measured by the Intersection over Union (IoU) of bounding boxes across all annotator pairs, was 0.89, indicating a high level of annotation consistency.

The dataset consists of 1140 images and 20,132 annotated objects, covering 8 typical classroom behaviors, including hand-raising, reading, writing, using phone, bowing the head, leaning over the table, look up, and stand up. As shown in Table 1, the behavior “reading” (29.3%) and “look up” (22.8%) have the largest number of samples, while “hand-raising” (2.5%) and “leaning over the table” (2.4%) have fewer samples, resulting in a significant long-tail distribution. This characteristic places higher demands on the robustness of the detection model and more closely mirrors the challenges of behavior recognition in real classroom scenarios [18,19].

Table 1.

ClassDatasets Category Distribution.

The dataset was partitioned into a training set (798 images, 70%), a validation set (228 images, 20%), and a test set (114 images, 10%).

3.2. Training Parameters and Evaluation Metrics

Handling of Class Imbalance: The ClassroomDatasets exhibits a significant class imbalance, as detailed in Table 1. To mitigate the potential performance degradation on minority classes such as ‘hand-raising’ and ‘leaning over the table’, a combined strategy was employed during training. This strategy leveraged the Mosaic and MixUp data augmentations integrated within the Ultralytics YOLOv11 framework, which synthesize novel training samples by combining multiple images to increase the effective representation and diversity of rare classes [20]. Furthermore, the classification loss function inherently incorporates a class-wise weighting mechanism based on label frequencies, automatically assigning higher penalties to misclassifications of minority classes. This dual approach effectively addresses the class imbalance issue, promoting more balanced learning and detection performance across all behavior categories.

In the training experiments of the object detection model, the following parameter settings were adopted: the batch size was set to 16, the input image resolution was 640 × 640, and the number of training epochs was 200. The initial learning rate was set to 0.01, with a learning rate decay factor of 0.01, indicating that the learning rate would remain relatively stable during training. The momentum coefficient was set to 0.937 to help accelerate training and improve convergence. The weight decay coefficient was set to 0.0005 to prevent overfitting and improve the model’s generalization ability. The optimizer used was Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD).

In object detection tasks, evaluating the effectiveness of the model’s performance is crucial. To comprehensively assess the detection performance, four key metrics are commonly used: Precision (P), Recall (R), mAP50 (Mean Average Precision at IoU = 0.5), and mAP50–95 (Mean Average Precision at IoU = 0.5:0.95). Precision measures the proportion of actual positive samples among all the samples predicted as positive by the model. Its calculation formula is:

where TP represents true positives and FP represents false positives. The higher the precision, the fewer false alarms the model has. Recall measures the proportion of actual positive samples that the model correctly predicts as positive. Its calculation formula is:

where TP represents true positives and FN represents false negatives. The higher the recall, the more positive samples the model can identify, reducing missed detections. Precision and recall are usually interdependent, meaning that increasing precision may decrease recall and vice versa, so both metrics need to be considered together [21,22].

mAP50 and mAP50–95 are two commonly used metrics for evaluating object detection models at different IoU thresholds. mAP50 represents the average precision at an IoU threshold of 0.5 and is typically used to evaluate the overall detection performance of the model. Its calculation formula is:

where C is the number of classes and APc is the Average Precision for class c. In contrast, mAP50–95 considers multiple IoU thresholds ranging from 0.5 to 0.95, providing a more stringent evaluation standard that can assess the model’s performance under varying precision requirements. The calculation formula for mAP50–95 is:

where N represents the number of IoU thresholds, typically 10 (i.e., IoU values from 0.5 to 0.95 with a step size of 0.05). The higher the mAP50–95 value, the better the model performs under stricter precision requirements.

These evaluation metrics together provide a comprehensive performance assessment of object detection models and offer data support for subsequent optimization.

To ensure the reliability and statistical significance of the experimental results, all major comparative experiments (ablation studies and model comparisons) in this research were independently repeated five times under the same conditions using different random seeds. The reported performance metrics (Precision, Recall, mAP, and FPS) are the average values from the five runs. Additionally, we calculated the standard deviation to assess the variability of the results and employed paired sample t-tests (significance level α = 0.05) to determine the statistical significance of performance differences.

Evaluation Protocol for Multi-Student Detection

The evaluation metrics (Precision, Recall, mAP) follow the standard object detection protocol, which is specifically designed to handle multiple instances per image. For each image in the test set, the model predicts a set of bounding boxes, each associated with a behavior class and a confidence score [23]. These predictions are then compared to the ground-truth annotations, with the Intersection-over-Union (IoU) threshold used as the primary matching criterion.

A predicted detection is considered a True Positive (TP) if it satisfies two conditions: the IoU between the predicted bounding box and the ground-truth box exceeds the specified threshold (e.g., 0.5 for mAP50), and the predicted behavior class matches the annotated class of the corresponding ground-truth box.

Each ground-truth annotation can be matched to at most one prediction (the one with the highest confidence among those meeting the IoU threshold), ensuring a one-to-one correspondence. Predictions that do not meet the IoU threshold with any unmatched ground-truth annotation are counted as False Positives (FP). Any ground-truth annotation that remains unmatched is considered a False Negative (FN).

The matching process is performed independently for each behavior category. The resulting counts of TP, FP, and FN are used to compute Precision and Recall per class. These values are then integrated into the mAP metric, as outlined in Equations (12) and (13). This protocol ensures a consistent and standardized evaluation of the model’s ability to both localize and classify the behaviors of individual students in multi-person classroom scenes.

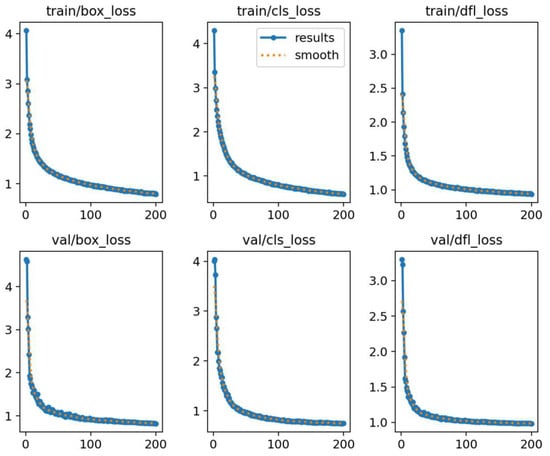

3.3. Loss Function Analysis

As shown in Figure 4, during the model training process, we closely monitored the trends of the bounding box loss (box_loss), classification loss (cls_loss), and distributed focal loss (dfl_loss). All loss components exhibited a steady decline throughout the training, indicating that the model effectively learned the underlying features of the data and gradually optimized its parameters to minimize the losses. This smooth downward trend reflects the model’s progression toward the optimal solution, without any noticeable oscillations or instability.

Figure 4.

Loss function analysis of YOLOv11-ASV.

Moreover, the loss trends on the validation set followed a similar downward pattern, further confirming the model’s strong generalization ability on unseen data. The absence of significant fluctuations in the loss functions suggests that the training process remained stable, with no indications of overfitting or underfitting. Notably, around the 150th epoch, the loss changes plateaued, further validating that the model had reached convergence at this stage.

Overall, the stable decrease in the loss function, coupled with its consistency on the validation set, demonstrates the model’s superior performance on both the training and validation datasets [24]. This provides strong support for subsequent performance evaluations and highlights the effectiveness and reliability of the proposed model in practical applications.

3.4. Robustness and Boundary Condition Analysis

3.4.1. Statistical Significance Analysis

To ensure the reliability of the performance comparison, we conducted reproducibility experiments between the baseline model YOLOv11 and the proposed YOLOv11-ASV. Table 2 summarizes the mAP50–95 results from five independent runs. YOLOv11-ASV consistently outperformed the baseline across all runs, with an average performance of 0.621 ± 0.0032 (mean ± standard deviation), compared to 0.592 ± 0.0041 for YOLOv11. The lower standard deviation of YOLOv11-ASV indicates better reproducibility in its training process. A paired t-test conducted on the two sets of results revealed a p-value of < 0.001, statistically supporting that the 2.9% mAP50–95 improvement achieved by YOLOv11-ASV is significant and stable, rather than due to random fluctuations.

Table 2.

Model Performance Reproducibility Analysis (mAP50–95).

3.4.2. Robustness Analysis Under Boundary Conditions

To validate the practicality of the model in complex real-world scenarios, we quantitatively assessed its performance on a predefined challenging subset. As shown in Table 3, YOLOv11-ASV consistently demonstrated superior robustness compared to the baseline across all challenging conditions. Notably, in scenarios involving severe occlusion and small targets, the relative performance improvements (3.9% and 3.6%, respectively) were significantly higher than the overall dataset improvement (2.9%). This directly demonstrates that the ASPN module’s multi-scale context modeling and adaptive fusion mechanisms are effective in addressing challenges posed by information loss and target scale variation. For side-view poses, the model also maintained stable performance gains, indicating its adaptability to changes in viewpoint.

Table 3.

Robustness Performance Comparison on Challenging Subsets (mAP50–95).

3.5. Ablation Study

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed improved algorithm model, this section conducts an ablation study to compare the baseline YOLOv11, YOLOv11-VanillaNet, YOLOv11-ASPN, and YOLOv11-ASV models, assessing the impact of different modules on the model’s performance. Table 4 lists the performance comparison of each model.

Table 4.

Ablation Study Results.

From Table 4 show that YOLOv11-ASV shows significant advantages in terms of Precision, Recall, and mAP metrics, with particularly notable improvements in Recall and mAP50–95. Compared to the baseline YOLOv11, YOLOv11-ASV achieves superior performance in Recall and mAP50–95. Furthermore, YOLOv11-ASV demonstrates efficient inference speed. Although the FPS is slightly lower than YOLOv11-ASPN, it still meets the requirements for real-time detection.

Overall, the YOLOv11-ASV model, by constructing the YOLOv11-ASV model, exhibits significant enhancements in fine-grained object detection capability, robustness, and detection accuracy, thereby demonstrating the efficacy of the proposed improvements.

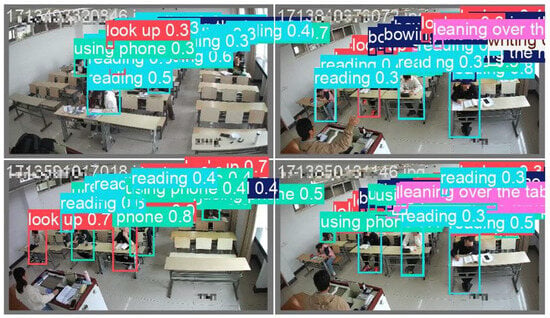

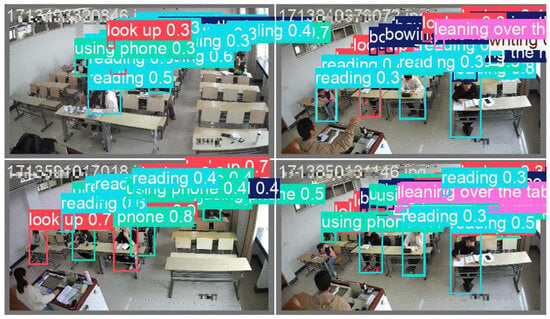

3.6. Comparative Experiments

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the proposed YOLOv11-ASV model, this section compares it with the current mainstream YOLO series models, including YOLOv5, YOLOv8, YOLOv9, and the baseline YOLOv11. All models were trained on the ClassDatasets, maintaining consistent input resolution (640 × 640) and training strategies to ensure the fairness of the comparison results. The experimental results are presented in Table 5. The detection results for classroom behavior recognition using YOLOv11 and YOLOv11-ASV are illustrated in Figure 5 and Figure 6.

Table 5.

Comparison results of different models.

Figure 5.

The experimental results of YOLOv11.

Figure 6.

The experimental results of YOLOv11-ASV.

As shown in Table 5, YOLOv11-ASV achieves the best overall accuracy. It reaches 0.815 mAP50, a 1.6% improvement over the baseline YOLOv11. On the stricter mAP50–95 metric, the improvement reaches 2.9%, demonstrating stronger robustness at high IoU thresholds. Recall increases from 0.726 to 0.762, enabling better detection of fine-grained, easily confused behaviors. In terms of efficiency, YOLOv11-ASV attains 46.32 FPS, 7.85 FPS faster than the baseline, showing excellent inference speed and meeting real-time classroom detection requirements.

To further verify the performance improvements of YOLOv11-ASV across different categories, Table 6 presents a comparison of mAP50–95 between YOLOv11 and YOLOv11-ASV for each class. Special attention is given to the performance improvements for similar or difficult-to-distinguish behavior categories (e.g., reading, writing, and leaning over the table).

Table 6.

Comparison of mAP50–95 for YOLOv11 and YOLOv11-ASV across different categories.

From Table 6, YOLOv11-ASV improves over YOLOv11 in most behavior categories, especially similar or hard-to-distinguish ones. For reading, mAP50–95 increases by 4.3% (0.637 → 0.680); writing improves by 3.4% (0.562 → 0.596); and leaning over the table improves by 4.5% (0.549 → 0.594). These results indicate YOLOv11-ASV effectively differentiates fine-grained behaviors, handling complex and similar categories with higher precision and reduced confusion.

This advantage can primarily be attributed to the multi-scale context modeling capability of the ASPN module, which effectively compensates for VanillaNet’s limitations in fine-grained feature representation. The model’s improvements are especially significant in tasks that require precise differentiation of similar behaviors.

In summary, YOLOv11-ASV outperforms the baseline YOLOv11 in detection accuracy, recall, and inference speed, while exhibiting stronger differentiation capabilities for fine-grained behavior recognition tasks. This indicates that the proposed YOLOv11-ASV model effectively enhances the baseline’s detection performance and robustness.

3.6.1. Compare the Results of the Visualization Experiment

From the visualization results in Figure 5 and Figure 6, it can be observed that the YOLOv11 model fails to accurately cover the target area with the bounding boxes in some cases, resulting in missed detections. In contrast, the YOLOv11-ASV model achieves higher accuracy in detecting most behaviors, successfully identifying these behaviors with more precise bounding box localization. In addition to the accuracy of the bounding boxes, we further assessed the correctness of the class labels. By comparing the prediction results of both models, we found that the YOLOv11 model has misclassification issues in certain scenarios, particularly in the detection of behaviors such as “reading” and “writing,” where multiple targets were misclassified. In contrast, the YOLOv11-ASV model, by introducing multi-scale feature fusion and an improved backbone network, handles these scenarios more effectively, reducing misclassifications, missed detections, and improving class label assignment.

In summary, the YOLOv11-ASV model outperforms the baseline model in terms of detection accuracy and missed detections. The visualization experiment results validate the effectiveness of the proposed model and further demonstrate its reliability and advantages in the task of classroom behavior recognition.

3.6.2. Compare the Results of Different Model

To further validate the effectiveness of the proposed model, four cutting-edge algorithms focusing on neck and backbone modifications were selected for comparison. The MSAM module [25] integrates self-attention and a state-space model, enhancing handling of dependencies and contextual information, especially for complex behaviors and multi-target interactions. The WFU module [26] combines wavelet transforms and feature enhancement networks, improving detail restoration in low-resolution images through multi-scale feature extraction. Starnet [27] introduces a novel architecture to better process multi-dimensional features. MambaOut [28] optimizes basic semantic feature extraction in classification and detection, excelling in stable extraction of textures, contours, and simple object boundaries, providing more reliable input for behavior classification and object localization.

Through the combination and comparison of these modules, this paper aims to evaluate the role of different modules in improving the performance of the YOLOv11 model. Table 7 shows the performance comparison results between YOLOv11 and its integrated variants with different modules.

Table 7.

Comparison of model improvement results with different modules.

The results demonstrate that our proposed YOLOv11-ASV model delivers the best overall performance, achieving the highest scores in the critical mAP50 (0.815) and mAP50–95 (0.621) metrics. This underscores that the YOLOv11-ASV model provides a more robust and balanced solution compared to other modular approaches for tackling the challenges in classroom behavior recognition tasks.

3.7. Model Confusion Analysis

In addition to the quantitative analysis of boundary conditions, we examined the classification confusion patterns of the model. The analysis indicates that the most significant inter-class confusion occurs between behavior categories with highly similar postures, which represents one of the core challenges in classroom behavior recognition. The proposed YOLOv11-ASV model effectively reduces the mutual misclassification rate among these similar categories through its enhanced capability for fine-grained feature representation. This improvement aligns with the overall performance enhancement trend observed for fine-grained behavior categories, further corroborating the model’s effectiveness in capturing subtle postural differences.

4. Conclusions

This study introduces YOLOv11-ASV, a novel framework designed to address the critical challenges of classroom behavior recognition. Experimental evaluation and statistical analysis confirm that our model achieves significant and robust performance gains over strong baselines on the ClassroomDatasets (p < 0.001). Notably, the model demonstrates stronger adaptability under boundary conditions such as severe occlusion and small targets, validating its potential for practical application in complex classroom environments. The substantial improvement in distinguishing visually similar categories (e.g., ‘reading’ versus ‘writing’) underscores the efficacy of the proposed architectural enhancements in capturing fine-grained postural details.

The performance observed in this work is established under specific classroom conditions. The model’s adaptability to significantly different environments, such as those with alternative seating arrangements, lighting, or instructional styles, represents an important direction for future research. Extending the validation to a wider variety of educational settings will be a crucial step in translating this laboratory success into widespread practical utility.

In conclusion, YOLOv11-ASV offers an effective and efficient solution for classroom behavior recognition in contexts analogous to our study environment. The insights and architectural contributions presented here serve as a solid foundation for future developments in intelligent educational analytics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.W. and T.F.; methodology, Z.W.; software, Z.W.; validation, Z.W. and T.F.; formal analysis, Z.W.; investigation, Z.W.; resources, T.F.; data curation, Z.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.W.; writing—review and editing, T.F.; visualization, Z.W.; supervision, T.F.; project administration, T.F.; funding acquisition, none. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by the authors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. According to internationally recognized ethical and regulatory guidelines for educational research (e.g., U.S. 45 CFR 46, Exemption Category 1; CIOMS International Ethical Guidelines; GDPR principles on anonymized data), studies conducted in routine educational environments and involving minimal risk do not require formal ethics committee approval. Besides, this study was conducted in a natural classroom setting without any intervention in teaching activities or influence on students’ academic evaluation, and only involved anonymized data with all personally identifiable information permanently deleted, so ethical review and approval were waived for this study.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. All participants were aware of the data collection and agreed to the use of their data for research purposes.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study were obtained under official authorization from the Institute of Artificial Intelligence Industry, Shanghai University of Engineering Science, and cannot be shared publicly due to institutional restrictions. Data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ASPN | Adaptive Spatial Pyramid Network |

| SGD | Stochastic Gradient Descent |

| IoU | Intersection over Union |

| P | Precision |

| R | Recall |

| mAP50 | Mean Average Precision at IoU = 0.5 |

| mAP50–95 | Mean Average Precision at IoU = 0.5:0.95 |

| box_loss | box loss |

| cls_loss | classification loss |

| dfl_loss | distributed focal loss |

References

- Ionescu, R.T.; Wong, A.L.Y.; Guo, R.L.L. Classroom behavior recognition using convolutional neural networks. J. Educ. Data Min. 2019, 12, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, H. Real-time classroom behavior detection based on YOLOv3. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Education 2020, Ifrane, Morocco, 6–10 July 2020; pp. 87–92. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, R.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2015, 39, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2016, 38, 779–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bochkovskiy, A. YOLOv4: Optimal speed and accuracy of object detection. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.10934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jocher, G. YOLOv5: Implementing YOLO in PyTorch. 2020. Available online: https://github.com/ultralytics/yolov5 (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Ultralytics. YOLOv8: YOLO’s Latest Model for Object Detection and Segmentation. 2023. Available online: https://docs.ultralytics.com/models/yolov8/ (accessed on 25 December 2025).

- Ultralytics. YOLOv11: Advancing YOLOv8 for Complex Detection Tasks. 2025. Available online: https://docs.ultralytics.com/models/yolo11/ (accessed on 25 December 2025).

- Carion, N.; Massa, F.; Synnaeve, G.; Usunier, N.; Kirillov, A.; Zagoruyko, S. End-to-end object detection with transformers. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Virtual Event, 23–28 August 2020; pp. 213–229. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2005.12872 (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Lin, T.-Y.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R.B.; He, K.; Hariharan, B.; Dollar, D. Feature pyramid networks for object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 2117–2125. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/8100175 (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Ghiasi, G.; Lin, T.; Tan, M. NAS-FPN: Learning scalable feature pyramid architecture for object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 7036–7045. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1904.07392 (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Kweon, I.S. CBAM: Convolutional block attention module. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 3–19. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1807.06521 (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Wang, Q.; Luo, X.; Wu, M. ECA-Net: Efficient channel attention for deep convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020; pp. 11534–11542. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1910.03151 (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Cai, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y. PKINet: A pyramid contextual information network for object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Virtual Event, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 6024–6033. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2102.11088 (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Zhou, Z.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, J. HCF-Net: Hybrid context fusion network for dense object detection. IEEE Trans. Image Process 2023, 32, 2955–2966. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, H.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, K.; Lin, D.; Dai, B. Revisiting Skeleton-Based Action Recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 2969–2978. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, P.; Lan, C.; Zeng, W.; Xing, J.; Xue, J.; Zheng, N. Semantics-Guided Neural Networks for Efficient Skeleton-Based Human Action Recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020; pp. 1112–1121. [Google Scholar]

- Bosch, N.; D’Mello, S.K. Automatic Detection of Mind Wandering from Video in the Lab and in the Classroom. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2019, 12, 974–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Z.; Ouyang, W. Disentangling and Unifying Graph Convolutions for Skeleton-Based Action Recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 143–152. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, B.; Wang, C.; Huang, W.; Huang, D.; Peng, H. Recognition of Student Classroom Behaviors Based on Moving Target Detection. Trait. Du Signal 2021, 38, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, J.; Zhu, R.; Yuan, H.; Shou, Z.; Chen, L. Student Behavior Recognition Based on Multitask Learning. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2022, 81, 33183–33201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Jiang, F.; Si, J.; Xiong, L.; Lu, H. StuArt: Individualized Classroom Observation of Students with Automatic Behavior Recognition and Tracking. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2211.03127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khobdeh, S.B.; Yamaghani, M.R.; Sareshkeh, S.K. Basketball Action Recognition Based on the Combination of YOLO and a Deep Fuzzy LSTM Network. J. Supercomput. 2024, 80, 3528–3553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Q.; He, J. Student Behavior Recognition in Classroom Based on Deep Learning. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Yi, J.; Fan, H.; Lin, H. A lightweight semantic segmentation network based on self-attention mechanism and state space model for efficient urban scene segmentation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 4703215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Guo, H.; Liu, X.; Liang, K.; Hu, J.; Ma, Z.; Guo, J. Efficient face super-resolution via wavelet-based feature enhancement network. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.19768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Dai, X.; Bai, Y.; Wang, Y.; Fu, Y. Rewrite the stars. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, W.; Wang, X. MambaOut: Do we really need Mamba for vision? In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 11–15 June 2025. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.