Abstract

The co-gasification of bio-oil produced via fast pyrolysis and black liquor from the pulp industry may yield a valuable feedstock for renewable gasification. This study investigated the synergistic potential of this co-gasification process. Experiments were conducted in a miniature conical spouted-bed reactor at 800 °C using bio-oil/black liquor mixing ratios ranging from 1:9 to 9:1 under equivalence ratios (ER) of 0.1, 0.3, and 0.5. Syngas characteristics and gasification performance were assessed using the lower heating value (LHV), H2/CO ratio, cold gas efficiency (CGE), and carbon conversion ratio (CCR). Increasing the bio-oil fraction increased CO and CH4 concentrations due to its higher carbon content and lower moisture content, whereas black liquor promoted H2 formation through moisture-driven water–gas shift reactions. Higher ER values intensified combustion, increasing CO2 while reducing combustible gases. The most energy-rich syngas, with the highest LHV and CGE, was obtained using a 9:1 mixture at ER = 0.1. The CCR was greatest for pure bio-oil and the 5:5 ratio among mixtures, reflecting the catalytic effects of alkali species in black liquor. These results demonstrate that co-gasification can improve syngas quality and carbon utilization, with optimal performance depending on the intended application.

1. Introduction

In pursuit of a sustainable society, research into biofuels that can replace fossil fuels, a major contributor to greenhouse gas emissions, has been ongoing. Bio-oil, obtained by fast pyrolysis of biomass, has storage, transportation, and handling advantages owing to its higher energy density compared with raw biomass [1]. This allows for a flexible feedstock supply for syngas production. Bio-oil produced via pyrolysis can be used directly to generate heat and electricity for industrial applications and can also be converted into syngas via gasification. The syngas derived from bio-oil contains components such as H2 and CH4, enabling its use as an environmentally friendly fuel for power generation [2]. Compared to solid biomass gasification, bio-oil gasification produces significantly lower amounts of tar and char, facilitating the production of high-quality syngas [3]. However, large-scale gasification facilities are required to achieve the required scale and reduce overall production costs [4].

Black liquor, a by-product generated during pulp production in the papermaking process, contains spent cooking chemicals and dissolved non-cellulosic organic materials. Although it was historically treated as waste, it can be combusted as a fuel for electricity generation in pulp mills. In addition to combustion, various studies have investigated black liquor gasification to produce syngas, which can be further converted into high-value products, such as neutral methanol or dimethyl ether (DME) for automotive use [5]. Syngas produced from black liquor gasification typically contains H2, CO, and CH4, and, importantly, the process separates sulfur and sodium, resulting in the formation of hydrogen sulfide (H2S) [6].

Several studies have examined the co-gasification of bio-oil and black liquor. For example, Jafri et al. [7] investigated bio-oil-to-black liquor mixing ratios of 1:9, 1.5:8.5, and 2:8 at temperatures ranging from 1000 °C to 1100 °C using a pilot-scale entrained-flow reactor. Furthermore, Bach-Oller et al. [8] investigated whether alkali metals in black liquor function as catalysts during gasification, typically within conventional fluidized-bed environments, examining mixing ratios of 0:10, 2:8, and 3:7 at temperatures ranging from 720 °C to 860 °C. However, the Equivalence Ratio (ER) is one of the most critical operating parameters in gasification, as it directly governs the extent of partial oxidation, reaction temperature, and the distribution of major syngas components such as H2, CO, and CH4 [9]. Variations in ER significantly affect key reaction pathways, including reforming, water–gas shift, and hydrocarbon cracking reactions, thereby exerting direct control over syngas quality, cold gas efficiency, and tar formation [10,11]. At low ER conditions, incomplete oxidation limits heat generation and conversion efficiency, whereas excessive ER leads to over-oxidation of combustible gases, reducing syngas calorific value [11]. Despite its fundamental role, the systematic influence of a wide ER range on the co-gasification of bio-oil and black liquor has rarely been investigated. Furthermore, the correlation between ER and key performance metrics, such as cold gas efficiency (CGE) and carbon conversion ratio (CCR), remains insufficiently characterized for this specific binary system [7,8,12].

Hence, in this study, gasification experiments were conducted with bio-oil-to-black liquor mixing ratios of 1:9, 3:7, 5:5, 7:3, 9:1, and 10:0 at 800 °C, focusing on ER conditions (0.1, 0.3, 0.5) to analyze the effect of ER, which has not been sufficiently addressed in previous studies. The novelty of this work lies in quantifying how variations in ER govern the competitive pathways between partial oxidation and gasification, thereby dictating the synergistic behavior of these two liquid feedstocks. The primary objective is to identify the optimal synergistic balance for this binary fuel system and to characterize the non-linear shifts in syngas quality and conversion efficiency. To achieve these goals, a lab-scale conical spouted-bed reactor was employed instead of conventional cylindrical fixed or fluidized beds. Its performance is driven by a unique hydrodynamic flow pattern—characterized by a high-velocity ‘spout’ and a descending ‘annulus’—which promotes intense gas–solid contact. This reactor was strategically selected for its superior heat transfer and intense particle circulation, which effectively prevent feedstock agglomeration and ensure kinetically controlled reactions for viscous liquid–liquid mixtures.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials

To obtain bio-oil for gasification, fast pyrolysis was performed using a 2 kg/h scale spouted-bed reactor (Figure 1). The pyrolysis reaction was conducted at an optimized temperature of 500 °C with an inlet gas velocity of 4.75 m/s and a biomass feeding rate of 1.5 kg/h to maximize liquid yield, following the methodology described in our previous study [13]. Larch wood sawdust was used as the pyrolysis feedstock; its properties are summarized in Table 1. To evaluate the fuel potential of the bio-oil-black liquor mixtures, proximate and elemental analyses were conducted for bio-oil and black liquor. Elemental analysis was performed using an elemental analyzer (EA 1112, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) in accordance with ASTM D5373 [14]. Proximate analysis was carried out using a thermogravimetric analyzer (TGA-701, LECO, St. Joseph, MI, USA) following ASTM D3172 [15]. The higher heating value (HHV) was determined using a bomb calorimeter (AC-600, LECO, St. Joseph, MI, USA) based on ASTM D4809 [16].

Figure 1.

Experimental apparatus of the 2 kg/h spouted-bed fast pyrolysis reactor.

Table 1.

Physico-chemical properties of sawdust.

The proximate and elemental analysis results for bio-oil, black liquor, and their mixtures are presented in Table 2. The volatile and carbon contents of the bio-oil were higher than those of the black liquor, whereas the moisture and ash contents of the black liquor were significantly higher than those of the bio-oil. As the proportion of bio-oil increases, the mixture’s moisture content decreases, and the fixed carbon and volatile matter increase due to the intrinsic properties of bio-oil. The ash content also decreases with increasing bio-oil fraction. These variations in chemical composition are expected to directly influence the gasification pathways. Specifically, the high carbon and volatile content of bio-oil serve as the primary sources for increased CO and CH4 yields. Conversely, the high moisture content of black liquor is expected to act as an in-situ steam source, promoting the water–gas shift (WGS) reaction and steam reforming, which would enhance H2 production. In the elemental analysis, increasing the bio-oil content results in higher carbon and hydrogen and lower oxygen levels, consistent with the proximate analysis trends.

Table 2.

Proximate and elemental analysis.

2.2. Experimental Apparatus and Method

A schematic of the experimental setup for the gasification of bio-oil-black liquor mixtures is shown in Figure 2. The system consists of a gasification reactor and a syngas analysis unit. Gasification is conducted in a miniature conical spouted-bed reactor designed to ensure rapid heat transfer and uniform temperature distribution.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the experimental apparatus.

Previous studies using the same reactor [17] demonstrated a Biot number of approximately 0.1, indicating negligible internal temperature gradients. Pyrolysis numbers I and II ranged from 183.7 to 933.7 and 23.6 to 104.6, respectively, confirming a kinetically dominant regime where the reaction rate is governed by chemical kinetics rather than heat transport limitations. The particle heating rate within the sand bed was approximately 330 K/s, with a heating time of roughly 1 s, sufficiently shorter than the residence time to assume quasi-isothermal conditions. Because bio-oil has higher thermal conductivity than solid biomass, similar thermally stable, kinetically controlled conditions are expected during gasification in the present study.

For the gasification experiment, silica sand was used as the bed material. The bio-oil–black liquor mixtures were introduced into the conical spouted-bed reactor, where they reacted with the oxidant to produce syngas. The amount of feed used in each run was 3 g, corresponding to 3 wt.% of the total bed material. The inlet gas velocity was set to 3.7 m/s, which corresponds to U/Ums = 1.2, to ensure stable spouting of the bed. Oxygen was supplied to satisfy the target ER, while additional nitrogen was introduced as a balancing gas to maintain U/Ums = 1.2. The detailed experimental methodology is provided in a previous study [17]. While the small feed mass (3 g) and lab-scale reactor used in this study allow for high-precision measurements of the intrinsic kinetics by minimizing heat and mass transfer resistances, there are limitations when extrapolating these results to industrial-scale systems. In commercial applications, additional engineering challenges such as continuous feeding stability, complex heat loss management, and the hydrodynamic behavior of larger beds must be further investigated to ensure process reliability at scale.

The resulting syngas was passed through cold and moisture traps and subsequently analyzed using a Micro GC Fusion gas analyzer (INFICON, Bad Ragaz, Switzerland) in accordance with KS I ISO 6976 [18]. Gasification was performed at 800 °C with BO:BL blending ratios of 1:9, 3:7, 5:5, 7:3, and 9:1, while the ER was varied from 0.1 to 0.5, as summarized in Table 3. The ER values were selected to represent the transition from starved-air gasification (ER = 0.1) to partial combustion (ER = 0.5), encompassing the typical operational condition for biomass gasifiers (ER = 0.2–0.4). This selection allows for an investigation of how gas quality and conversion efficiency change across a broad range of conditions.

Table 3.

Bio-oil and black liquor co-gasification experimental condition.

To ensure the reliability and reproducibility of the experimental results, each test case was repeated until consistent data were achieved, with an average of approximately three runs conducted for each condition. The final reported results represent the mean values of these consistent trials.

2.3. Chemical Reaction Mechanism in the Gasifier

Representative chemical reactions occurring during gasification, including carbon reactions, oxidation, water–gas shift (WGS), and steam methane reforming (SMR), are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Chemical reactions during the gasification process [2,19,20,21,22].

Black liquor gasification involves additional multi-phase reactions associated with alkali components, as shown in Table 5. Among these, the carbonate reduction reaction (R19) plays a key catalytic role, enhancing carbon conversion during co-gasification.

Table 5.

Multi-phase chemical reactions of the black liquor gasification process [23,24].

To evaluate the gasification performance, the lower heating value (LHV), H2/CO ratio, cold gas efficiency (CGE), and carbon conversion ratio (CCR) were analyzed. The LHV of the syngas produced from gasification was calculated using Equation (1). In this equation, represents the actual volumetric lower heating value (LHV) of the gas mixture at the reference temperature and the volumetric condition . denotes the ideal-gas-based volumetric LHV calculated from the molar heating values and molar fractions of each gas component. is the compressibility factor of the gas mixture used to correct the deviation of real gas behavior from the ideal gas assumption at temperature and pressure . In this study, the reference conditions were set to = 15 °C, = 0 °C, and = 101.325 kPa in accordance with KS I ISO 6976.

CGE was determined from the LHV of the syngas and the LHV of the feedstock, as defined in Equation (2). CCR, an important indicator of gasification efficiency, was calculated using Equation (3). The H2/CO ratio, representing the molar ratio of hydrogen to carbon monoxide, was obtained using Equation (4).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characteristics of Bio-Oil Produced by Fast Pyrolysis

Gasification was carried out in a conical spouted-bed reactor to examine the effects of the bio-oil-black liquor mixing ratio and the equivalence ratio (ER) on the co-gasification behavior. The results of the pyrolysis experiments that produced the bio-oil used for gasification are presented in Table 6. The yields and heating values of the pyrolysis products were measured, and the energy yield was evaluated using Equation (5).

Table 6.

Effects of different reaction temperatures on the biochar and bio-oil characteristics.

The bio-oil yield was greatest at 500 °C and was selected for use in the subsequent gasification experiments.

3.2. Characteristics of the Co-Gasification Syngas Products

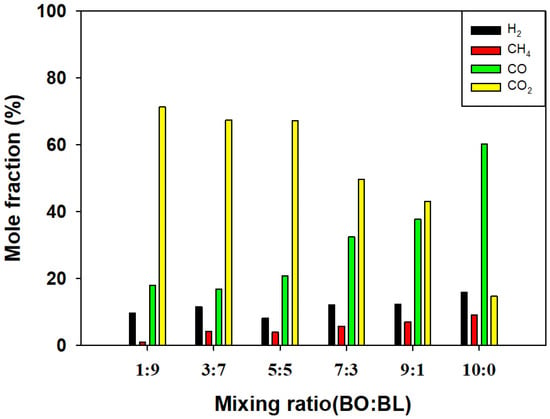

The observed variations in syngas components (H2, CO, CO2, and CH4) are governed by the complex interplay of the oxidation and reduction reactions listed in Table 4 and Table 5 (R1–R19). The syngas composition at an ER of 0.1 for different mixing ratios of bio-oil and black liquor is shown in Figure 3. The CO and CH4 concentrations increase with the proportion of bio-oil. This is due to the higher carbon content and lower moisture content in mixtures with higher bio-oil fractions. These observations are consistent with the findings of Jafri et al. [7], who reported that increasing the share of pyrolysis oil in black liquor mixtures enhances the concentration of carbonaceous gas species due to the increased energy density and volatile matter.

Figure 3.

Major gas concentration with respect to mixing ratio (ER = 0.1).

The increased carbon content results in higher CO and CH4 concentrations, while reduced moisture suppresses the water–gas shift reaction (R17) and the methane steam reforming reaction (R18), thereby reducing CO and CH4 consumption [25]. Conversely, increasing the fraction of black liquor decreases CO and CH4 concentrations while increasing H2 concentrations due to its high moisture content. Specifically, this high moisture acts as a driving force for the water–gas shift reaction (R17), promoting H2 production at the expense of CO [25]. This trend indicates a synergistic potential where the steam generated from the black liquor’s inherent moisture acts as a co-reactant that facilitates the gasification of the bio-oil components, promoting the formation of hydrogen-rich syngas. These results align with previous studies on black liquor gasification, where the high water content inherently promotes H2 production via the water–gas shift reaction, often at the expense of CO concentration [6,25].

The syngas composition at ER values of 0.3 and 0.5 is shown in Figure 4 and Figure 5, respectively. The overall trends are similar to those observed at ER 0.1. As the ER increases, the amount of supplied O2 increases, enhancing combustion reactions. This results in higher CO2 concentrations and lower concentrations of the other syngas components. The increase in CO2 with increasing ER indicates intensified combustion [26]. This inverse relationship between ER and combustible gas fraction is a well-established phenomenon in solid biomass gasification; higher oxygen availability shifts the equilibrium towards complete oxidation products (CO2 and H2O) rather than syngas components, as extensively reported in the literature [26]. At a given ER, increasing the proportion of bio-oil reduces CO2 concentrations because the higher carbon content, combined with relatively limited oxygen, limits combustion reactions. Furthermore, the interaction between the mixing ratio and ER suggests that the energy-boosting effect of bio-oil is most effectively realized at a low ER of 0.1; as the ER increases toward 0.5, the high carbon content of the bio-oil is increasingly diverted toward CO2 formation rather than combustible gas enrichment, partially diminishing the synergistic benefits observed at lower ER values.

Figure 4.

Major gas concentration with respect to mixing ratio (ER = 0.3).

Figure 5.

Major gas concentration with respect to mixing ratio (ER = 0.5).

These results provide a guide for selecting operating conditions based on the target application. To optimize the syngas for power generation, a higher bio-oil fraction should be selected to maximize the concentrations of CO and CH4, which are the primary contributors to the LHV and overall energy recovery efficiency (CGE). Conversely, increasing the black liquor ratio is more effective for tailoring the H2/CO ratio for chemical synthesis.

3.3. Evaluation of Gasification Efficiency

To evaluate the gasification performance, the LHV, H2/CO ratio, CGE, and CCR of the syngas were calculated for each experimental condition. The LHV increased with a higher proportion of bio-oil in the mixture (Figure 6). This is because increasing the bio-oil fraction increases the carbon content while reducing the moisture content, thereby increasing CO and CH4 concentrations, which are two major contributors to LHV. This positive correlation between bio-oil content and energy density corroborates the work of Jafri et al. [7], who observed that adding high-heating-value pyrolysis oil to black liquor significantly boosts the calorific value of the product gas compared to pure black liquor gasification.

Figure 6.

LHV with respect to mixing ratio and ER.

Increasing the ER led to higher CO2 concentrations and lower concentrations of other syngas components due to enhanced combustion; thus, LHV decreased with increasing ER. The reduction in calorific value at higher ER (ER = 0.16) is observed by Zhu et al. [26], where higher oxygen concentration promotes complete combustion (C + O2 → CO2) rather than partial oxidation, thereby diluting the syngas with non-combustible CO2.

The H2/CO ratio decreased with increasing ER because elevated CO2 concentrations reflect intensified combustion and consumption of H2 and CO (Figure 7). In contrast, the H2/CO ratio increased as the fraction of black liquor increased, owing to the higher moisture content that promotes H2 formation through the water–gas shift reaction (R17), which decreases CO while increasing H2. This aligns with the characteristics of black liquor gasification described by Naqvi et al. [6], where high inherent moisture facilitates hydrogen production, shifting the syngas composition toward higher H2/CO ratios suitable for specific downstream applications like DME synthesis.

Figure 7.

H2/CO with respect to mixing ratio and ER.

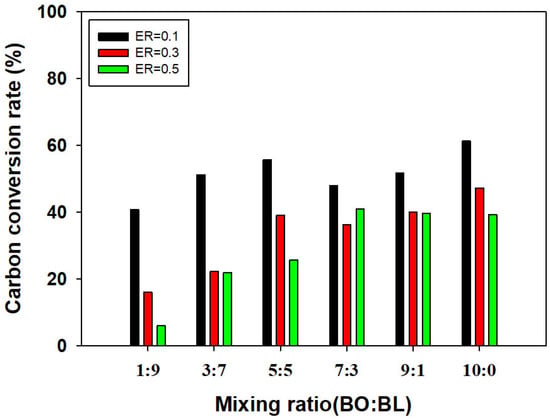

CGE exhibited a similar trend to LHV, increasing with higher bio-oil proportions, likely due to higher CO and CH4 concentrations in the syngas (Figure 8). Notably, as shown in Figure 9, CCR demonstrated a non-linear enhancement at the 5:5 mixing ratio under ER 0.1. Despite the 9:1 ratio having a higher carbon input from the bio-oil fraction, the 5:5 mixture achieved a superior CCR, indicating a positive synergistic interaction. This finding aligns with results reported by Bach-Oller et al. [8,24], who demonstrated that alkali metals (Na, K) present in black liquor act as inherent catalysts, enhancing the reaction rates and carbon conversion of the blended fuel matrix. However, it should be noted that the catalytic role of alkali species in this study is an indirect interpretation based on the experimental CCR trends. A definitive confirmation of the catalytic mechanism and the chemical state of sodium would require detailed analysis of the solid residue (e.g., SEM or XRD), which remains a subject for future work. Furthermore, the carbon balance for the system was evaluated by comparing the carbon flow in the syngas with the initial carbon content of the feedstock. At a CCR of approximately 60%, the remaining 40% of the carbon was inferred to be distributed as solid char and condensed tar within the reactor and bed material, which is consistent with the observed high-temperature gasification behavior in a lab-scale system.

Figure 8.

CGE with respect to mixing ratio and ER.

Figure 9.

CCR with respect to mixing ratio and ER.

4. Conclusions

In this study, bio-oil and black liquor were mixed at ratios of 1:9, 3:7, 5:5, 7:3, and 9:1 and gasified at 800 °C. Gasification was also conducted at ER values of 0.1, 0.3, and 0.5 to determine the optimal co-gasification conditions. Gasification performance was evaluated based on the LHV, H2/CO ratio, CGE, and CCR of the produced syngas. As the proportion of bio-oil increased, the carbon content of the feedstock increased, whereas a higher fraction of black liquor increased the moisture content. Consequently, increasing the bio-oil fraction led to lower H2 and higher CO and CH4 concentrations in the syngas.

As the bio-oil fraction increased, higher CO and CH4 concentrations corresponded to increased LHV and CGE values, whereas the H2/CO ratio decreased due to reduced H2 formation. CCR reached its highest value under pure bio-oil gasification and was lowest when the black liquor fraction was greatest. Among the blended samples, the 5:5 mixture achieved the highest CCR, likely due to the catalytic effect of alkali species in black liquor.

With respect to ER, the concentrations of H2, CO, and CH4 were highest at ER = 0.1, while ER = 0.5 resulted in increased CO2 formation and reduced concentrations of combustible gases due to enhanced combustion reactions. The highest-quality syngas was produced at a 9:1 mixing ratio under ER = 0.1. While the 9:1 mixing ratio produced the highest LHV, the 5:5 ratio was identified as the optimal condition based on a comprehensive evaluation balancing gas quality, the synergistic enhancement of CCR, and practical feedstock handling.

Author Contributions

J.G.H.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing—Original Draft, Visualization. S.W.H.: Data Curation. M.K.C.: Validation, Data Curation. H.S.C.: Resources, Writing—Review and Editing, Supervision, Project Administration, Funding Acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Regional Innovation System & Education (RISE) program through the Gangwon RISE Center, funded by the Ministry of Education (MOE) and the Gangwon State (G.S.), Republic of Korea (2025-RISE-10-006). Additionally, this work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (RS-2025-23323456).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Jae Gyu Hwang is affiliated with LOTTE Chemical R&D Center. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CCR | Carbon conversion ratio |

| CGE | Cold gas efficiency |

| DME | Dimethyl ether |

| ER | Equivalence ratio |

| LHV | Lower heating value |

| SMR | Steam methane reforming |

| WGS | Water–gas shift |

References

- Chen, T.; Wu, C.; Liu, R. Steam reforming of bio-oil from rice husks fast pyrolysis for hydrogen production. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 9236–9240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, J.L.; Zhu, Y.H.; Zhu, M.Q.; Kang, K.; Sun, R.C. A review of gasification of bio-oil for gas production. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2019, 3, 1600–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buelvas, A.; Quintero-Coronel, D.A.; Vanegas, O.; Ortegon, K.; Bula, A.; Mesa, J.; González-Quiroga, A. Gasification of solid biomass or fast pyrolysis bio-oil: Comparative energy and exergy analyses using AspenPlus®. Eng. Rep. 2024, 6, e12825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, G. Techno-economic analysis of advanced biofuel production based on bio-oil gasification. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 191, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekbom, T.; Lindblom, M.; Berglin, N.; Ahlvik, P. Technical and Commercial Feasibility Study of Black Liquor Gasification with Methanol/DME Production as Motor Fuels for Automotive Uses—BLGMF; Final Report; Nykomb Synergetics AB: Stockholm, Sweden, 2003; Available online: https://dspace.tul.cz/server/api/core/bitstreams/d150c6e3-7383-40fb-b8dc-56d2a9040827/content (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Naqvi, M.; Yan, J.; Dahlquist, E. Black liquor gasification integrated in pulp and paper mills: A critical review. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 8001–8015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jafri, Y.; Furusjö, E.; Kirtania, K.; Gebart, R.; Granberg, F. A study of black liquor and pyrolysis oil co-gasification in pilot scale. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 2018, 8, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach-Oller, A.; Furusjö, E.; Umeki, K. ‘Fuel conversion characteristics of black liquor and pyrolysis oil mixtures: Efficient gasification with inherent catalyst’ ScienceDirect. Biomass Bioenergy 2015, 79, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, P. Biomass Gasification and Pyrolysis: Practical Design and Theory; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, P.; Xiong, Z.; Chang, J.; Wu, C.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, J. An Experimental Study on Biomass Air–Steam Gasification in a Fluidized Bed. Bioresour. Technol. 2004, 95, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil, J.; Aznar, M.P.; Caballero, M.A.; Francés, E.; Corella, J. Biomass Gasification in Fluidized Bed at Pilot Scale with Steam–Oxygen Mixtures. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1999, 38, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Kim, H. The Reduction and Control of Tar during Biomass Gasification: A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2008, 12, 397–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.C.; Lee, B.K.; Yoo, H.S.; Choi, H.S. Influence of Operating Conditions for Fast Pyrolysis and Pyrolysis Oil Production in a Conical Spouted-Bed Reactor. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2019, 42, 2493–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D5373; Standard Test Methods for Instrumental Determination of Carbon, Hydrogen, and Nitrogen in Laboratory Samples of Coal. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

- ASTM D3172; Standard Practice for Proximate Analysis of Coal and Coke. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2013.

- ASTM D4809; Standard Test Method for Heat of Combustion of Liquid Hydrocarbon Fuels by Bomb Calorimeter (Precision Method). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018.

- Park, H.C.; Yun, D.W.; Choi, M.K.; Choi, H.S. Study on biomass fast pyrolysis kinetics in an isothermal spouted-bed thermogravimetric analyzer and its application to CFD. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2022, 168, 105777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KS I ISO 6976; Natural Gas—Calculation of Calorific Values, Density, Relative Density and Wobbe Indices from Composition. Korean Agency for Technology and Standards: Eumseong, Republic of Korea, 2021.

- Reed, T. Biomass Gasification: Principles and Technology; Noyes Data Corporation: Park Ridge, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Kinoshita, C. Kinetic Model of Biomass Gasification. Sol. Energy 1993, 51, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcazar-Ruiz, A.; Ortiz, M.L.; Dorado, F.; Sanchez-Silva, L. Gasification versus fast pyrolysis bio-oil production: A life cycle assessment. J. Clean Prod. 2022, 336, 130373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.G.; Choi, M.K.; Choi, D.H.; Choi, H.S. Quality improvement and tar reduction of syngas produced by bio-oil gasification. Energy 2021, 236, 121473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.J.; Ramaswamy, S. Thermodynamic Analysis of Black Liquor Steam Gasification. BioResources 2011, 6, 3210–3230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach-Oller, A.; Kirtania, K.; Furusjö, E.; Umeki, K. Co-gasification of black liquor and pyrolysis oil at high temperature: Part 1. Fate of alkali elements. Fuel 2017, 202, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandara, J.C.; Eikeland, M.S.; Moldestad, B.M.E. Analysis of the effect of steam-to-biomass ratio in fluidized bed gasification with multiphase particle-in-cell CFD simulation. In Proceedings of the 58th SIMS, Reykjavik, Iceland, 25–27 September 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, D.; Wang, Q.; Xie, G.; Ye, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Ye, C. Effect of air equivalence ratio on the characteristics of biomass partial gasification for syngas and biochar co-production in the fluidized bed. Renew. Energy 2024, 222, 119881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.