Abstract

This review, within the One Health framework, compiles information on plant-derived bioactive compounds and emphasises their multifunctional role in improving environmental, animal, and human health. These compounds support sustainable health and ecological stability by influencing biological and environmental processes. Data from literature research are combined to explain the mechanisms and potential uses of different key bioactive compounds. Mechanistic insights focus on their capacity to regulate oxidative stress, inflammation, and microbial balance, linking these effects to therapeutic benefits in human health, enhanced animal productivity, and environmental sustainability. These compounds show antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and metabolic activities, helping prevent chronic diseases, strengthen immunity, and reduce reliance on antibiotics and pollution. Examples like quercetin, resveratrol, and curcumin demonstrate their roles in modulating inflammatory and metabolic pathways to foster sustainable health and ecological balance. Bioactive compounds are linked to the One Health strategy, providing benefits across biological systems. Nonetheless, challenges such as variability, bioavailability, and standardization remain. Future directions should aim to develop sustainable extraction and formulation methods, leverage omics technologies and artificial intelligence for discovery and characterization, and foster industry partnerships to validate these compounds and secure global regulatory approval.

1. Introduction

The One Health approach, recognised by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), emphasises the interconnection between human, animal, and environmental health and highlights the need for integrated strategies to tackle global challenges [1]. Within this context, natural bioactive compounds, produced by microorganisms, marine organisms, and plants, have proven to be multipurpose agents that promote harmony between human, animal, and environmental systems. For instance, microorganisms remain the primary industrial source of antibiotics and fermentation-derived products with antimicrobial, anticancer, and immunomodulatory activities [2,3,4,5,6]. Marine organisms provide structurally unique metabolites shaped by extreme environmental pressures, yielding promising agents with antitumour, antiviral, and anti-inflammatory properties, as well as broad biotechnological applications [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14]. Lastly, plants represent the most accessible and renewable reservoir of bioactive compounds; their availability, cultural acceptance, and compatibility with sustainable production systems make plant-derived bioactive compounds particularly relevant for the One Health objectives [15].

Plant-derived bioactive compounds have been studied due to their antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, immunomodulatory, and metabolic regulatory properties, which sustain their role for chronic disease prevention, immune strengthening, microbial homeostasis, and reduced dependence on synthetic chemicals [16,17,18]. From a One Health perspective, these benefits extend beyond human medicine. In animal health, plant-derived bioactive compounds are being explored as performance enhancers and as alternatives to antibiotics, reducing the selective pressure that drives antimicrobial resistance [19]. At the environmental level, they can influence soil microbial communities, contribute to bioremediation, and improve productivity in agri-food systems [20,21]. Examples such as quercetin, resveratrol, and curcumin prove how modulation of oxidative, inflammatory, and metabolic pathways can translate into human health advantages, livestock productivity, and ecological resilience [22]. Despite this potential, important challenges remain: chemical variability, influenced by genetics, cultivation, and processing, delays standardization and reproducibility, while low stability or bioavailability can limit translation into effective products [23,24]. Progress, therefore, depends on sustainable extraction and formulation technologies, omics-based characterization, artificial-intelligence-driven discovery, and coordinated industry–academic partnerships [24,25]. Harmonised regulatory frameworks will also be essential to validate safety, efficacy, and ecological impact [24].

This review aims to gather and critically assess the role of plant-derived bioactive compounds, particularly the polyphenols, highlighting their multifunctionality and potential contributions to human, animal, and environmental health in accordance with the One Health approach. It will explore different mechanisms of action by which these bioactive compounds are involved, as well as emerging applications, such as natural preservatives and therapeutic advancements, while identifying the gaps that must be addressed to improve this field.

2. Plant-Derived Bioactive Compounds: An Overview

Bioactive compounds are defined by their biological activity rather than their origin, and include any molecule, whether natural or synthetic, that interacts with living systems to induce physiological or pharmacological effects [26,27]. As previously mentioned, bioactive compounds are organic molecules biosynthesised by living organisms, such as plants, microorganisms, and marine species [26,27]. These compounds are commonly classified into primary, secondary, and tertiary metabolites, based on their biological roles [26,27,28,29]. Primary metabolites (PMs) are essential for growth, development, and reproduction, including carbohydrates, lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids [30]. They take part in vital processes such as photosynthesis, respiration, cell structure formation, and function as signalling molecules (e.g., hormones and growth regulators like auxins and gibberellins) [30]. On the other hand, secondary metabolites (SMs) are not directly required for growth, but they confer ecological advantages, such as defence and adaptation [31,32]. They include phenolics, alkaloids, terpenoids, flavonoids, glycosides, and others, with bioactive properties relevant to medicine, agriculture, and biotechnology [23,25,26,27,33,34]. SMs arise from complex and integrated biosynthetic networks responsive to environmental stimuli [29]. Finally, tertiary metabolites (TMs) result from combinations or modifications of PMs and SMs with proteins, sugars, or lipids [32]. They are involved in embryogenesis, seed development, and stress adaptation, influencing metabolic balance [35]. Many natural compounds containing these metabolites exhibit anti-inflammatory, anticancer, and anti-ageing properties, underscoring their significant biomedical importance [28,29].

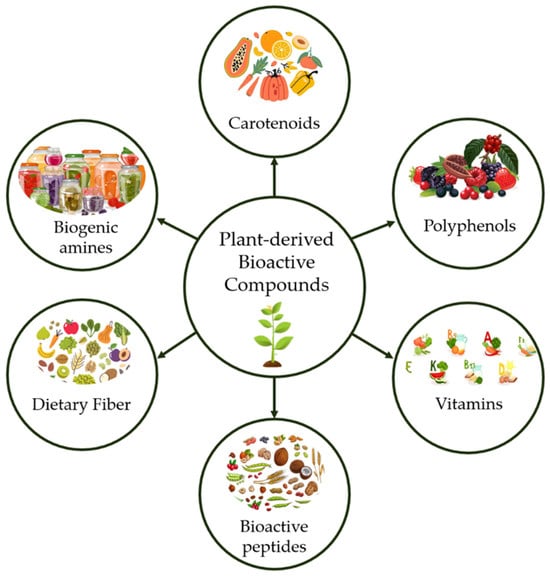

The plant kingdom comprises a vast diversity of species capable of producing structurally complex and biologically active metabolites, including carotenoids, biogenic amines, dietary fibre, bioactive peptides, vitamins, and polyphenols [36], as represented in Figure 1. Despite this, only 6% of plant species have been pharmacologically investigated, and approximately 15% have been phytochemically characterised [30,31]. Plants synthesise more than 200,000 metabolites, with applications in pharmaceutical, agrochemical, and food industries [25,37]. Compared to synthetic molecules, plant-derived products have greater structural diversity, higher molecular rigidity, and multiple chiral centres contributing to enhanced selectivity and pharmacokinetic performance [23]. Nearly 25% of modern pharmaceuticals and over 60% of anticancer and antimicrobial agents are obtained from plant natural products [24,38]. However, yield limitations, ecological dependence, and high research costs constrain large-scale exploitation, highlighting the need for biotechnological and metabolic engineering approaches to enhance production [39].

Figure 1.

Synthesised overview of plant-derived bioactive compounds.

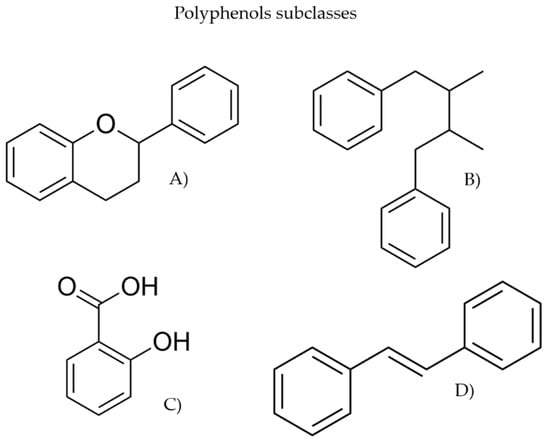

This review focuses on plant-derived bioactive compounds, namely polyphenols, SMs whose structural diversity and biological relevance have made them important sources of dyes, flavours, fragrances, and, notably, pharmaceuticals [25,37,40,41]. This class is divided into four subclasses, flavonoids, lignans, phenolic acids, and stilbenes [42], represented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Representation of polyphenol subclasses structures (A) flavonoids, (B) lignans, (C) phenolic acids, and (D) stilbenes.

Flavonoids represent the most abundant and extensively investigated subclass of polyphenols and are widely distributed in fruits, vegetables, and various medicinal and aromatic plants [42,43]. Due to their nutritional, therapeutic, and antioxidant properties, flavonoids have broad applications across the food, pharmaceutical, chemical, and forest product industries [43]. Lignans are broadly documented in seeds, fruits, and vegetables [44]. These compounds display a wide range of biological activities, including anti-ageing, antimicrobial, hepatoprotective, cardioprotective, and other health-promoting effects [42]. Their diverse bioactivities have facilitated the incorporation of lignans into food formulations and various medical and clinical applications [45]. Phenolic acids, abundant in whole grains, coffee, and many plant-derived foods, are known for their antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antidiabetic functions [42]. Beyond their dietary relevance, phenolic acids play essential physiological and ecological roles in plants and exhibit therapeutic potential against a range of human diseases. Their redox properties enable them to act as reducing agents, hydrogen donors, and singlet oxygen quenchers [46]. Finally, the subclass of stilbenes, which includes the compound resveratrol, has attracted considerable attention due to its potential in preventing cardiovascular, oncological, and neurodegenerative disorders [42]. Naturally occurring stilbenes are widespread in plants, where they often function as phytoalexins produced in response to biotic and abiotic stresses. These compounds exhibit a broad spectrum of biological activities, as antimicrobial, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-leukemic, anti-platelet, anti-cancer, and anti-HIV effects. Due to their diverse pharmacological properties and structural complexity, stilbenes and their derivatives remain a focus of product research [47].

3. Mechanisms of Action of Plant-Derived Bioactive Compounds

The biological effects of plant-derived bioactive compounds are underpinned by multi-target molecular actions that converge on a limited set of conserved regulatory pathways involved in oxidative stress control, inflammatory signalling, and metabolic homeostasis, ultimately influencing processes linked to ageing and chronic disease progression. Rather than behaving as single-target drugs, many phytochemicals exert pleiotropic effects through complementary mechanisms, which helps explain their broad physiological relevance across complex biological systems [48,49,50].

3.1. Conserved Molecular and Cellular Pathways

A central feature of plant-derived bioactive compounds is their capacity to modulate oxidative stress and inflammatory signalling, two fundamental processes underlying ageing, metabolic dysfunction, and chronic disease progression. Many plant bioactives influence intracellular redox homeostasis not only through direct scavenging of reactive oxygen species but also by enhancing endogenous antioxidant defences and regulating redox-sensitive signalling cascades [48,49,50].

Key pathways recurrently modulated by these compounds include NF-κB and MAPK signalling, which coordinate inflammatory transcriptional programmes, and Nrf2-associated cytoprotective responses, which govern antioxidant and detoxification systems. Through these mechanisms, plant-derived bioactives attenuate chronic low-grade inflammation and promote cellular resilience [50,51,52,53].

In parallel, several compounds interact with metabolic sensing pathways, notably AMPK and SIRT1, contributing to improved mitochondrial function, energy balance and metabolic flexibility. These effects link redox and inflammatory control with metabolic adaptation and stress tolerance, reinforcing the view that plant bioactives act as multifunctional regulators rather than simple antioxidants [50,54,55].

An additional mechanistic layer involves microbiota-mediated effects. By shaping microbial community composition and stimulating the production of short-chain fatty acids, plant-derived bioactives indirectly modulate immune responses, epithelial barrier integrity and systemic metabolism. Together, these overlapping pathways illustrate how a limited set of conserved molecular hubs underpins the diverse biological actions of plant-derived compounds [56,57,58].

3.2. Structure–Mechanism Relationships in Plant-Derived Bioactive Compounds

The convergence of plant-derived bioactive compounds on conserved signalling hubs is closely linked to their chemical architecture and functional groups. Despite marked structural diversity, distinct phytochemical scaffolds repeatedly map onto similar molecular pathways, explaining their consistent biological relevance across different contexts [16,29].

Polyphenolic scaffolds, characterised by hydroxyl-rich aromatic systems, are particularly associated with modulation of redox-sensitive and inflammatory pathways. Structural features such as catechol or polyhydroxylated moieties favour interactions with transcription factors and kinases involved in NF-κB, MAPK, and Nrf2 signalling, while also supporting antioxidant capacity. More rigid and planar architectures, as observed in stilbene-type scaffolds, further enable interactions with metabolic sensing pathways, particularly those centred on AMPK and SIRT1, linking redox control to metabolic regulation [48,50,55,59].

Curcuminoid-type structures represent a distinct yet mechanistically convergent example. Their conjugated systems and phenolic functionalities allow simultaneous engagement with multiple inflammatory and oxidative stress pathways, including NF-κB-, MAPK-, and COX-2-related signalling, together with antioxidant enzyme induction. This multi-node interaction profile provides a structural rationale for their broad regulatory capacity [60,61,62].

In contrast, phenolic monoterpenes are characterised by higher lipophilicity and preferential interaction with biological membranes. Their mechanisms of action are dominated by membrane perturbation and modulation of microbial viability, while still intersecting inflammatory signalling pathways. This membrane–microbiota interface distinguishes their functional profile from that of polyphenolic compounds and underlies their relevance in contexts where microbial pressure and barrier integrity are critical [63,64,65].

Overall, these structure–mechanism relationships demonstrate how chemically diverse plant-derived bioactive compounds converge on a restricted set of conserved molecular hubs, generating functionally coherent biological effects [16,50].

3.3. From Molecular Mechanisms to One Health Effects

The evolutionary conservation of key signalling pathways provides the mechanistic foundation for the One Health relevance of plant-derived bioactive compounds. Pathways such as NF-κB, MAPKs, Nrf2, and AMPK/SIRT1 are conserved across taxa and play central roles in inflammation, metabolism, stress responses, and barrier function. Modulation at this level therefore leads to convergent physiological effects across species, despite differences in exposure routes, life stages, and biological systems [29,50,66].

Importantly, the environmental dimension emerges primarily as a system-level consequence of these shared mechanisms. By enhancing resilience, supporting metabolic and immune balance, and stabilising host–microbiota interactions, plant-derived bioactives can indirectly reduce reliance on antimicrobial and chemical interventions in medical, veterinary, and agricultural settings. This reduction in chemical pressure has downstream implications for environmental contamination, ecosystem stability, and antimicrobial resistance dynamics [67,68,69].

Taken together, plant-derived bioactive compounds should be viewed as multifunctional modulators of conserved biological systems, rather than single-target agents. Their structure–mechanism relationships explain why chemically diverse phytochemicals repeatedly align with integrated benefits across human, animal, and environmental health, providing a coherent mechanistic framework for the One Health relevance explored in the following section [16,50,66].

Table 1 summarises the main structural architectures of plant-derived bioactive compounds and their convergence on conserved molecular hubs, highlighting how chemically distinct scaffolds can generate coherent biological effects that underpin their One Health relevance.

Table 1.

Main classes of plant-derived bioactive compounds, representative molecules, and key mechanisms of action relevant to human health.

4. One Health Relevance of Bioactive Compounds

4.1. Plant-Derived Bioactive Compounds and Human Health

In the context of human health, plant-derived bioactive compounds represent a chemically diverse group of secondary metabolites that have evolved through long-term ecological interactions between plants and their environment. This evolutionary pressure has resulted in molecules with multifunctional biological activities, capable of interacting with multiple molecular targets simultaneously. Such chemical diversity underpins their long-standing relevance in drug discovery and explains their renewed importance in modern preventive and personalised medicine [24,25].

Within the One Health framework, plant-derived bioactive compounds occupy a strategic position at the interface between nutrition, health and environmental sustainability. At dietary or nutraceutical levels, these compounds exert protective effects against oxidative stress, chronic inflammation, and metabolic dysregulation, processes that are central to the development of non-communicable diseases and shared across human, animal, and environmental health systems. Importantly, these effects gain additional relevance considering the widespread use of antibiotics, which, while essential in clinical and veterinary contexts, can disrupt host-associated microbiota and contribute to metabolic imbalance, immune dysregulation, and antimicrobial resistance across interconnected human, animal, and environmental compartments [56,67,78]. Their pleiotropic mechanisms distinguish them from single-target synthetic molecules, supporting holistic health maintenance rather than isolated therapeutic outcomes [79]. These effects are consistent with the conserved molecular mechanisms described in Section 3.

This section focuses specifically on bioactive compounds of plant origin, with particular emphasis on polyphenols, flavonoids, phenolic acids, terpenoids, and plant-derived polysaccharides, which represent the most extensively studied and biologically relevant classes in human health [80].

4.1.1. Impact of Plant-Derived Bioactive Compounds on Human Health

Through their integrated mechanisms of action, plant-derived bioactive compounds contribute to the prevention and modulation of multiple chronic conditions across the human lifespan, as also highlighted in recent lifespan-oriented reviews of polyphenol functionality [50,81].

4.1.2. Cardiovascular and Metabolic Health

Dietary polyphenols have been consistently associated with improved endothelial function, reduced oxidative damage, and modulation of vascular inflammation. These effects translate into lower blood pressure, improved lipid profiles, and reduced cardiovascular risk [51,82,83]. In metabolic disorders, including type 2 diabetes, plant-derived polyphenols and phenolic acids improve insulin sensitivity, regulate glucose uptake, and modulate the AGE–RAGE axis, contributing to better glycaemic control and metabolic stability [52,84].

4.1.3. Obesity and Low-Grade Inflammation

Plant-derived bioactive compounds play a relevant role in obesity-related metabolic inflammation by suppressing adipogenesis, regulating lipid metabolism, and modulating gut microbiota composition [54,60]. Prebiotic polysaccharides and polyphenols enhance microbial diversity and short-chain fatty acid production, thereby reducing systemic inflammation and supporting weight management strategies [54,85,86,87].

4.1.4. Cancer Prevention and Cellular Protection

Several plant bioactive compounds, including flavonoids, stilbenes, and phenolic acids, exhibit chemopreventive properties by regulating oxidative stress, apoptosis, angiogenesis, and inflammatory signalling [88,89]. Their multitarget actions complement conventional therapies and contribute to reduced carcinogenic risk and improved cellular homeostasis [89,90].

4.1.5. Ageing, Cognitive Function, and Skin Health

Across the lifespan, plant-derived bioactive compounds support healthy ageing by modulating hallmarks of ageing such as oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and chronic inflammation [81,91]. Polyphenols and carotenoids have been shown to improve cognitive performance, preserve skin integrity, and enhance stress resistance through pathways involving SIRT1, AMPK, and autophagy regulation [50,91,92]. These effects align with the emerging concept of nutritional strategies aimed at extending health span rather than lifespan alone. The major health outcomes associated with plant-derived bioactive compounds and their underlying biological mechanisms are synthesised in Table 2.

Table 2.

Health outcomes associated with plant-derived bioactive compounds and their underlying biological mechanisms.

4.2. Plant-Derived Bioactive Compounds and Animal Health

The progressive restriction of antibiotic growth promoters (AGPs) in livestock production has intensified the search for effective and sustainable alternatives that maintain animal health, productivity, and welfare while reducing selective pressure for antimicrobial resistance (AMR) [67,68]. Within this context, plant-derived bioactive compounds have emerged as promising nutritional and functional tools, aligned with the One Health framework by simultaneously benefiting animal performance, food safety, and environmental protection [67,69].

Unlike conventional antibiotics, plant-derived bioactive compounds exert multifunctional effects that extend beyond pathogen suppression, including modulation of gut microbiota, enhancement of intestinal barrier integrity, and regulation of immune responses. These properties make them particularly attractive for integration into antibiotic-free production systems [67,99].

4.2.1. Plant-Derived Bioactive Compounds as Alternatives to Antibiotics

A wide range of plant-derived bioactive compounds, including polyphenols, essential oil constituents and tannin-rich extracts, have been evaluated as alternatives to AGPs in in vivo livestock models. Supplementation with compounds such as thymol, carvacrol, eugenol, and quercetin has been associated with improved growth performance, feed conversion efficiency, and reduced intestinal colonisation by pathogenic bacteria in poultry and swine [67,68].

These effects are supported by in vitro evidence demonstrating antimicrobial activity against enteric pathogens and interference with quorum sensing and biofilm formation [100,101]. However, the relevance of these compounds lies primarily in their in vivo efficacy, where multi-target mechanisms contribute to stable and resilient gut ecosystems rather than indiscriminate microbial suppression [67,68].

In aquaculture, plant-derived bioactive compounds have similarly shown beneficial effects, including improved antioxidant status, enhanced innate immunity, and reduced disease-related mortality in fish species, reinforcing their applicability across diverse animal production systems [99,102].

Despite these advantages, variability in chemical composition, dose optimisation, and stability during feed processing remain challenges for large-scale application. Advances in encapsulation and formulation strategies are increasingly addressing these limitations, improving bioavailability and consistency of biological effects [69,103].

4.2.2. Modulation of Gut Health, Microbiota, and Immune Function

The gastrointestinal tract represents a critical interface between diet, microbiota, and host immunity, making it a primary target for plant-derived bioactive compounds [56,78]. In vivo studies in poultry and swine have demonstrated that supplementation with phytogenic compounds and plant extracts enhances villus height, tight-junction protein expression, and mucosal integrity, thereby strengthening the intestinal barrier [99,104].

Concomitantly, these compounds modulate gut microbial communities by promoting beneficial taxa such as Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium while suppressing opportunistic pathogens. These shifts are associated with reduced intestinal inflammation, improved nutrient absorption and increased production of short-chain fatty acids, which play a central role in immune regulation [57,99].

Plant-derived bioactive compounds also exert immunomodulatory effects by attenuating pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6) and enhancing anti-inflammatory mediators such as IL-10. Such immune balancing contributes to increased resilience against enteric infections and may reduce the need for therapeutic antibiotic interventions [67,99,105].

Synergistic strategies combining plant-derived compounds with probiotics or antimicrobial peptides have shown enhanced efficacy in in vivo animal models, highlighting the potential of integrated nutritional approaches to support gut health and immune competence [106,107].

4.2.3. Implications for Zoonotic Risk and Antimicrobial Resistance

Beyond individual animal health, the use of plant-derived bioactive compounds has broader implications for zoonotic disease control and antimicrobial resistance (AMR) mitigation. By reducing pathogen load, intestinal dysbiosis and environmental shedding of resistant bacteria, these compounds contribute to lower transmission risks along the food chain [67,108].

Recent surveillance studies have revealed a high prevalence of AMR genes in livestock-associated environments, emphasising the urgency of alternative strategies that reduce antibiotic dependence [109]. Plant-derived bioactive compounds, together with prebiotics, probiotics, and antimicrobial peptides, can mitigate these reservoirs by promoting stable microbial ecosystems and enhancing host defences [107,110].

However, effective implementation requires harmonised regulatory frameworks, standardised dosing strategies, and comprehensive risk assessments to ensure safety and reproducibility. When integrated into antibiotic-free production systems, plant-derived bioactive compounds represent a viable pathway toward reducing AMR dissemination while maintaining animal productivity and welfare within a One Health perspective [69,108].

Representative examples of plant-derived bioactive compounds evaluated in livestock production systems, together with their main in vivo effects and relevance within the One Health framework, are summarised in Table 3.

Table 3.

Representative plant-derived bioactive compounds evaluated in livestock and aquaculture systems and their relevance within the One Health framework.

4.3. Environmental Health and Ecosystem Sustainability

Plant-derived bioactive compounds play a fundamental role in environmental health by mediating ecological interactions, supporting sustainable agricultural practices and reducing reliance on synthetic chemical inputs [67,103]. Within the One Health framework, their environmental relevance lies not only in their biological activity but also in their generally lower environmental persistence, reduced ecotoxicity and potential contribution to biodiversity preservation and antimicrobial resistance (AMR) mitigation [103,113].

Unlike conventional agrochemicals, many plant-derived bioactives are biodegradable and act through multitarget mechanisms, which limits the development of resistance and minimises unintended impacts on non-target organisms. These properties position them as key components of environmentally responsible strategies in agriculture and ecosystem management [103,112].

4.3.1. Role of Plant-Derived Bioactive Compounds in Ecological Interactions

In natural ecosystems, plant-derived bioactive compounds such as phenolics, terpenoids, alkaloids, and peptides act as chemical mediators regulating plant–microbe, microbe–microbe, and plant–insect interactions. These compounds contribute to plant defence against pathogens and herbivores, modulate microbial competition in the rhizosphere, and enhance tolerance to abiotic stressors, including drought, ultraviolet radiation, and heavy metals [29,30,35].

Root-exuded phenolic acids and other secondary metabolites can selectively stimulate beneficial rhizobacteria, promoting nutrient acquisition and plant growth while suppressing phytopathogens. In parallel, microbial metabolites influenced by plant-derived substrates contribute to soil aggregation, carbon sequestration, and nutrient cycling, reinforcing ecosystem stability [35,114,115].

Importantly, these ecological functions are closely linked to environmental health outcomes, as they support resilient soil microbiomes and reduce the need for synthetic inputs that disrupt ecological balance.

4.3.2. Applications in Biopesticides, Biofertilisers, and Sustainable Agriculture

The multifunctionality of plant-derived bioactive compounds has driven their application in biopesticides, biofertilisers, and biostimulants as sustainable alternatives to conventional agrochemicals. Well-established examples include azadirachtin from Azadirachta indica and pyrethrins from Chrysanthemum species, which exhibit effective insecticidal activity while displaying lower toxicity towards non-target organisms when properly applied [111,112].

Plant-derived compounds are also increasingly incorporated into integrated pest management strategies, often in combination with microbial agents. Such approaches enhance pest control efficacy while reducing environmental contamination and selective pressure for resistance development [103,112]. In parallel, humic substances and seaweed-derived polysaccharides act as biostimulants, improving root development, nutrient uptake, and soil microbial activity, thereby supporting sustainable crop productivity [114,115].

These applications demonstrate that plant-derived bioactive compounds contribute not only to pest suppression but also to broader ecosystem services, including soil health preservation and biodiversity enhancement, as summarised in Table 4.

Table 4.

Representative plant-derived bioactive compounds and related natural products with ecological functions and applications in sustainable agriculture within a One Health framework.

4.3.3. Reduction in Environmental Impact and Contribution to One Health

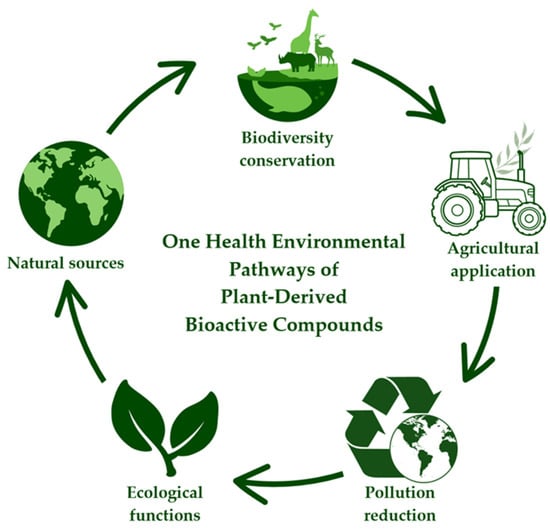

Replacing or reducing synthetic agrochemicals with plant-derived bioactive compounds offers tangible environmental benefits. Conventional pesticides and fertilisers are often persistent, bioaccumulative, and harmful to pollinators, aquatic organisms, and soil microbiota, contributing to long-term ecosystem degradation [103,111]. Figure 3 illustrates the environmental pathways of plant-derived bioactive compounds, from their natural sources to agricultural application and ecosystem-level effects, highlighting their contribution to environmental sustainability and the One Health framework.

Figure 3.

Environmental pathways of plant-derived bioactive compounds within a One Health framework, illustrating their progression from plant-based natural sources to agricultural applications, pollution reduction, ecological functions, and biodiversity conservation, with integrated implications for human, animal, and environmental health.

In contrast, plant-derived bioactive compounds generally exhibit faster environmental degradation and lower ecotoxicological profiles, reducing unintended impacts on non-target species and limiting contamination of water and soil systems [103,112]. Life cycle and risk assessment studies further indicate that biologically based inputs can reduce chemical residues and environmental pressure when integrated into sustainable agricultural practices [112].

From a One Health perspective, these environmental benefits have direct implications for human and animal health. Reduced chemical loads in ecosystems lower exposure risks across the food chain and indirectly contribute to limiting the environmental dissemination of antimicrobial-resistant bacteria. By supporting biodiversity, soil resilience, and ecological balance, plant-derived bioactive compounds represent a validated strategy for promoting environmental sustainability within integrated health frameworks [67,108,109].

Key environmental benefits and One Health implications associated with the use of plant-derived bioactive compounds, in comparison with conventional synthetic inputs, are summarised in Table 5.

Table 5.

Environmental and One Health implications of plant-derived bioactive compounds compared with conventional synthetic agrochemicals.

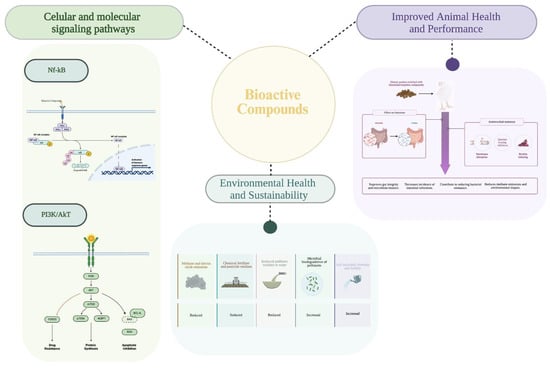

Figure 4 synthesises the One Health framework discussed in this section, illustrating how chemically distinct plant-derived bioactive compounds converge on conserved molecular hubs (e.g., NF-κB/MAPKs, Nrf2-related cytoprotection, and AMPK/SIRT1-linked metabolic sensing). Modulation at the pathway level translates into coordinated cellular and organism-level effects in human and animal systems, with indirect environmental benefits arising from reduced chemical and antimicrobial pressure.

Figure 4.

Overview of the main effects of bioactive compounds across cellular, animal, and environmental levels, illustrating their integrative contribution to the One Health concept.

5. Applicability of Selected Plant-Derived Bioactive Compounds: Evidence-Based Case Examples Within One Health

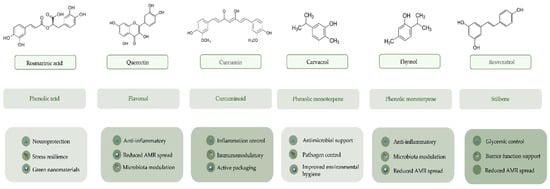

Building on the mechanistic framework outlined in Section 3 and Section 4, Table 6 compiles representative case examples showing how selected plant-derived bioactive compounds translate conserved pathway modulation into cross-pillar outcomes. Quercetin, resveratrol, curcumin, thymol, carvacrol, and rosmarinic acid exemplify an upstream (“preventive”) intervention logic: by targeting signalling hubs such as NF-κB, MAPKs, and AMPK/SIRT1, they can attenuate inflammatory signalling and support redox homeostasis. Several also display antimicrobial activity and/or microbiota-modulatory effects, consistent with benefits that extend from host resilience to downstream environmental co-benefits via reduced antimicrobial and chemical pressure, as summarised in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Graphical summary of the One Health-relevant bioactivities of six representative plant-derived bioactive compounds (quercetin, resveratrol, curcumin, rosmarinic acid, thymol, and carvacrol) across the human, animal, and environmental pillars.

5.1. Human Health

In the human health pillar, the applicability of these plant-derived bioactive compounds lies in their use as nutritional strategies and adjunct interventions in contexts characterised by chronic inflammation, oxidative stress, and metabolic dysfunction, as illustrated in Table 4. The compiled evidence supports their action on central regulatory mechanisms controlling inflammation and metabolism, notably via modulation of NF-κB, including inhibition of IκBα phosphorylation and the consequent reduction in NF-κB activation, as well as MAPKs and AMPK/SIRT1, resulting in decreased pro-inflammatory mediators and reinforcement of endogenous antioxidant responses. This mechanistic coherence is exemplified by quercetin, which is associated with anti-inflammatory effects in cardiometabolic settings through NF-κB-related regulation, and by resveratrol, whose action on SIRT1/AMPK and related metabolic signalling pathways is consistent with improvements in glycaemic homeostasis reported in Table 4 [53,119,120,121,122]. Complementarily, curcumin displays an integrative profile by modulating NF-κB/AMPK/COX-2 and inducing endogenous antioxidant enzymes (e.g., SOD, CAT, GPx), supporting its relevance in inflammatory and metabolic disorders. Importantly, these compounds may also be pertinent in situations where barrier integrity and mucosal immunoregulation shape clinical expression of inflammation: rosmarinic acid, for instance, is linked in Table 6 to improvements in allergic manifestations at the nasal mucosa level, consistent with modulation of NF-κB/MAPKs and related signalling (including PI3K/Akt). Overall, these examples indicate that applicability within the human pillar is not merely “antioxidant” or “anti-inflammatory” in generic terms but instead rests on defined, biologically grounded mechanisms with clinical relevance, supporting their integration into prevention and supportive therapeutic approaches aligned with the One Health paradigm.

5.2. Animal Health

In the animal health pillar, these compounds are applicable as functional feed and management additives capable of improving performance, health resilience, and product quality in key species, including poultry, swine, ruminants, and fish, as synthesised in Table 6. Their effects are biologically plausible because they involve modulation of conserved pathways governing inflammation, oxidative stress, and metabolism, including regulation of NF-κB and MAPKs, and, in some cases, activation of AMPK/SIRT1. A particularly relevant axis is the modulation of the gut microbiota and intestinal ecosystem, with direct implications for enteric health and infectious pressure. This is clearly illustrated by quercetin, which is associated with reduced burdens of undesirable microbes (e.g., total coliforms and Clostridium perfringens) alongside increased Lactobacillus spp. counts in broiler chickens (Table 6) [123]. Likewise, thymol is associated with increased Lactobacillus and reduced E. coli and Clostridium spp., whereas carvacrol is linked to reduced Clostridium perfringens and Salmonella spp. and to consistent zootechnical and health benefits across species (Table 6) [63,64,124]. In parallel, resveratrol stands out for improving intestinal morphology and barrier function and lowering inflammatory markers, while curcumin is highlighted for supporting host resilience under enteric challenge (e.g., reduced oocyst shedding) and for improving immunity-related and oxidative stability outcomes in poultry (Table 6) [102,125]. Taken together, these examples support their One Health applicability in animal production: promoting gut health, immunity, and pathogen control through alternatives compatible with reduced reliance on antibiotic growth promoters.

5.3. Environmental Health

Finally, within the environmental pillar, the applicability of these phytochemicals becomes evident when Table 6 is interpreted as a causal chain: improved animal health and reduced pathogen burdens can translate into lower pressure to use antibiotics, decreasing environmental discharge and the selective pressure that drives antimicrobial resistance (AMR). In this context, compounds such as quercetin, resveratrol, thymol, and carvacrol have strategic value because their documented effects on gut microbial load, host resilience, and performance support partial substitution of AGPs and contribute to reduced pharmaceutical residues entering manure, effluents, and receiving ecosystems, thereby benefiting soil and water quality and limiting AMR dissemination (Table 6). Beyond antibiotic-related externalities, Table 4 also links thymol and carvacrol to reductions in parameters relevant to the sustainability of livestock units, including odour, emissions such as ammonia, and in ruminant contexts methane, underscoring that their impact is not only sanitary but also associated with environmental footprint [124]. Finally, Table 6 highlights use cases that extend applicability into technological and mitigation solutions: curcumin is presented as relevant for biosensors and active packaging, and rosmarinic acid as a candidate for incorporation into green nanomaterials for pollutant removal [126,127]. These examples indicate that plant-derived bioactive compounds can reduce environmental chemical burdens not only through “less antibiotic use” but also through improved monitoring and contaminant mitigation strategies across the agri-food chain.

Overall, the evidence summarised in Table 6 supports the view that selected plant-derived bioactive compounds can be operationalised as One Health-compatible interventions, because they target conserved biological nodes, particularly inflammatory and redox-regulatory networks and host–microbe interactions, across humans and animals, while also offering pathways to reduce environmental externalities. In human health, their relevance is grounded in mechanistically defined modulation of inflammation and metabolism; in animal production, they provide functional tools to strengthen gut health and resilience and to reduce pathogen pressure, thereby supporting strategies that can lower reliance on antibiotic growth promoters. Importantly, these cross-sector effects translate into environmental relevance through reduced pharmaceutical residues, reduced selection pressure for antimicrobial resistance, and, for some compounds, lower emission-related burdens and applicability in greener technologies (e.g., active packaging, biosensing, or pollutant-removal materials). Future implementation should prioritise well-standardised formulations, improved bioavailability where needed, and harmonised outcome reporting to enable robust cross-species translation and real-world uptake within One Health policies.

Table 6.

Evidence-based applicability of plant-derived bioactive compounds within One Health: structure, key pathways, and effects across humans, animals, and the environment.

Table 6.

Evidence-based applicability of plant-derived bioactive compounds within One Health: structure, key pathways, and effects across humans, animals, and the environment.

| Compound | Conformation | Pathway | Experimental Models | Human Health | Animal Health | Environmental Relevance | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quercetin | Flavonol (C15H10O7) with five hydroxyls at positions 3, 5, 7, 3′, 4′. | Inhibition of IκBα phosphorylation and NF-κB activation. | Humans; Broiler chickens; Swine; Ruminants. | In coronary artery disease, oral supplementation (120 mg/day) reduced circulating IL-1β and TNF-α and downregulated IκBα expression. | In broiler chickens, dietary quercetin supplementation at 200–400 ppm for 35 days increased the European production efficiency factor (EPEF), decreased total coliforms and Clostridium perfringens, increased Lactobacillus counts, and improved antioxidant status, meat quality and overall productive performance. | Reduced need for AGPs; lower drug residues in products and effluents. | [119,120,121,123,128,129,130,131] |

| Resveratrol | Stilbene (3,5,4′-trihydroxystilbene) with two phenolic rings linked by an ethylenic bond. | Activation of SIRT1/AMPK; inhibition of PI3K/Akt/mTOR; modulation of ERK/JNK/p38 and Bcl-2/Bax-dependent apoptosis. | Humans; Broiler chickens; Swine; Ruminants; Fish. | In T2D (1 g/day for 45 days), improved insulin sensitivity and reduced fasting glucose. | In weaned piglets, dietary resveratrol at 300 mg/kg feed for 42 days improved growth, antioxidant status, intestinal morphology and barrier function and lowered inflammatory markers; in growing–finishing pigs, 300–600 mg/kg for 49 days enhanced meat quality and reduced carcass fat; in fish species such as tilapia, turbot and rainbow trout, inclusion of 0.05–0.3% of the diet for 9 weeks increased antioxidant capacity, disease resistance and flesh quality, although the highest doses could attenuate growth. | Substitution for AGPs reduces antibiotic discharge into ecosystems and mitigates AMR spread; lower methane improves environmental footprint. | [102,122,125,132,133,134,135,136] |

| Curcumin | Curcuminoid (diferuloylmethane) with two phenolic rings linked by a conjugated β-diketone chain bearing hydroxyl and methoxy groups. | Modulation of NF-κB, AMPK and COX-2; induction in SOD, CAT, and GPx; inhibition of IκB kinase; regulation of p38/JNK in inflammation and apoptosis. | Humans; Broiler chickens; Swine. | In T2D and ulcerative colitis, oral supplementation (80 mg/day for 3 months) reduced HbA1c, fasting glucose and clinical disease activity. | In poultry, dietary curcumin supplementation at about 0.25–0.5% of the diet for 8 weeks reduced oocyst shedding (Eimeria), improved egg quality, decreased abdominal fat and enhanced immunity and oxidative stability of meat. | Supports replacement of pharmaceutical additives; applicable to biosensors and active packaging, reducing chemical burden in ecosystems. | [60,62,126,127,137,138,139,140,141,142,143] |

| Thymol | Monoterpenoid phenol (2-isopropyl-5-methylphenol) with an isopropyl and a para-hydroxyl group on the aromatic ring. | Modulation of NF-κB and COX-2 signalling. | Humans; Broiler chickens; Swine; Ruminants; Fish. | Antimicrobial against S. aureus, E. coli, Candida spp, anti-inflammatory effect (NF-κB, COX-2), antioxidant, potential in inflammatory disorders and cancer. | ↑ Growth, ↓ Clostridium spp., improved meat/egg quality. ↑Lactobacillus, ↓ E. coli, better digestibility, ↑ survival, immunity, resistance to infections. | Reduced antibiotic residues in manure; ↓ coliforms, ammonia, methane and odour in livestock units. | [58,59,60,63,64,144] |

| Carvacrol | Monoterpenoid phenol, positional isomer of thymol (5-isopropyl-2-methylphenol) with an ortho-hydroxyl group. | Modulation of NF-κB and MAPKs. | Humans; Broiler chickens; Swine; Ruminants; fish. | Anti-inflammatory (↓ TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β), antimicrobial against Gram± bacteria and Candida biofilms; neuroprotective and metabolically beneficial. In a phase I clinical study, healthy adults supplemented orally with 1–2 mg/kg/day of carvacrol for 30 days showed good safety and tolerability, with only mild laboratory changes remaining within normal reference ranges. | Dietary incorporation of carvacrol resulted in clear zootechnical and health benefits across species. In broilers, 200–500 mg/kg feed for 28–42 days increased growth and feed efficiency and reduced Clostridium perfringens and Salmonella spp; in weaned piglets, 100 mg/kg for 14 days reduced post-weaning diarrhoea; in laying hens, 300 mg/kg for ~50 weeks improved egg quality and antioxidant status; in fish, 1–3 g/kg in feed increased survival. | ↓ Antibiotic reliance; ↓ pathogen shedding in litter and manure; ↓ odour and ammonia emissions; ↓ methane from ruminants; lower environmental pharmaceutical load. | [65,124,145,146] |

| Rosmarinic acid | Polyphenolic ester of caffeic acid and 3,4-dihydroxyphenyllactic acid, with two catechol moieties. | Modulation of NF-κB and MAPKs (ERK, JNK, p38); regulation of PI3K/Akt. | Humans; Broiler chickens; Rodents; Fish. | Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant; neuroprotective (Alzheimer’sParkinson’s); improves glucose metabolism; hepatoprotective and anticancer. In patients with seasonal allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, oral rosmarinic acid at 50 or 200 mg/day for 21 days reduced nasal symptoms and neutrophil/eosinophil infiltration. | In rodent models, oral rosmarinic acid at 1–50 mg/kg/day for 12 days protected kidney, liver, heart and brain from toxic, ischaemic or diabetic injury by reducing oxidative stress, inflammation and apoptosis; in poultry and fish, diets enriched with rosmarinic-acid-rich extracts administered for several weeks improved antioxidant status, immune responses and survival under infectious challenge. | Used in green nanomaterials for pollutant removal; enables partial replacement of synthetic additives and reduces pharmaceutical residues in ecosystems. | [147,148,149] |

6. Challenges and Future Perspectives

Plant-derived bioactive compounds, with applications in medicine, agriculture, and direct impact on environmental sustainability, display several bioactive properties, including antimicrobial, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antifungal effects, making them interesting alternatives to synthetic chemicals [150,151]. However, scientific, technological, and regulatory challenges remain, as comprehensive safety assessments, toxicological evaluations, and scientific validation of health claims are necessary and often supported by clinical trials and analytical verification [152]. Additionally, it is essential to achieve consistent bioavailability, stability, and standardisation, as variations in natural sources can lead to differences in chemical composition and biological activity. The same compounds may exhibit low solubility, limited absorption, and rapid degradation, thereby reducing their clinical or functional efficacy [153]. Ensuring standardisation and reproducibility during extraction and formulation is essential for consistent biological performance and product quality [154]. Advances in omics technologies, genomics, proteomics, and metabolomics are transforming the discovery and analysis of bioactive compounds. These high-throughput methods enable detailed characterisation of biological systems, allowing rapid and accurate identification of biosynthetic gene clusters, metabolic pathways, and bioactive metabolites. The combination of omics data with computational tools, such as bioinformatics and artificial intelligence (AI), accelerates the discovery of new bioactive compounds, supporting targeted biotechnological innovations and personalised applications in health and agriculture [66,155]. Looking forward, with an emphasis on the One Health approach, research should focus on developing cost-effective, scalable, and energy-efficient extraction methods. Collaboration between academia and industry is crucial to integrate advances in extraction methods with functional validation and product development. Furthermore, improving regulatory clarity and harmonisation worldwide can drive innovation while ensuring safety and transparency through accurate labelling and traceability.

7. Conclusions

This review highlights the vital roles in promoting the One Health strategy that plant-derived bioactive compounds play. For human health, these natural bioactive compounds are important as preventive and therapeutic agents by modulating oxidative stress, inflammation, and infection pathways, offering potential alternatives to synthetic drugs for managing chronic diseases and enhancing immune function. Regarding animal health, it might serve as a sustainable substitute for antibiotics and synthetic additives, improving gut health, boosting immunity, and helping mitigate AMR. If we think from an environmental perspective, bioactive compounds contribute to ecological balance by functioning as natural defence mechanisms against predators, pathogens, and stressors, while their application in biopesticides, biofertilisers, and soil enhancers supports sustainable agriculture and biodiversity conservation. Their biodegradability and low toxicity further reduce environmental impact compared to conventional chemicals.

To conclude, it is imperative to overcome the scientific, technological, and regulatory challenges to unlock the full potential of plant-derived bioactive compounds. Through sustainable extraction strategies, rigorous standardization, and collaborative innovation, bioactive compounds obtained from plant-derived products can form the foundation of nutraceutical alternatives, supporting both human health and environmental sustainability, and making them essential to integrated One Health strategies that link human, animal, and ecosystem well-being.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C.G., A.R.P., A.C., E.O.-F., and J.C.L.M.; methodology, A.C.G., A.R.P., A.C., E.O.-F., and J.C.L.M.; software, A.C.G., A.R.P., A.C., E.O.-F., and J.C.L.M.; validation, A.C.G., A.R.P., A.C., E.O.-F., and J.C.L.M.; formal analysis, A.C.G., A.R.P., A.C., E.O.-F., and J.C.L.M.; investigation, A.C.G., A.R.P., A.C., E.O.-F., and J.C.L.M.; resources, A.C.G., A.R.P., A.C., E.O.-F., and J.C.L.M.; data curation, A.C.G., A.R.P., A.C., E.O.-F., and J.C.L.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.C.G., A.R.P., A.C., E.O.-F., and J.C.L.M.; writing—review and editing, J.G., A.L., M.J.S., M.M.P., and M.J.A., visualization, J.G., A.L., M.J.S., M.M.P., and M.J.A.; supervision, J.G., A.L., M.J.S., M.M.P., and M.J.A.; project administration, M.J.S., M.M.P., and M.J.A.; funding acquisition, M.J.S., M.M.P., and M.J.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by National Funds by FCT–Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology, under the projects FCT/MCTES (PIDDAC): CIMO, UIDB/00690/2020 (https://doi.org/10.54499/UIDB/00690/2020) and UIDP/00690/2020 (https://doi.org/10.54499/UIDP/00690/2020); SusTEC, LA/P/0007/2020 (https://doi.org/10.54499/LA/P/0007/2020) Portugal; CECAV UIDB/00772/2020 (https://doi.org/10.54499/UIDB/00772/2020), CITAB, UID/04033/2025 and LA/P/0126/2020 (https://doi.org/10.54499/LA/P/0126/2020), LiveWell, UID/6157/2025, and CBQF, UID/50016/2025.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

Juliana Garcia and André Lemos acknowledge funding support from Portuguese public funding through Investimento RE-C05-i02–Missão Interface N.° 01/C05-i02/2022. Ana Rita Pinto would like to acknowledge FCT–Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, I.P. for the support and individual grant (2024.06170.BDANA). André Cima would like to acknowledge FCT–Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P. for the support and individual grant (PRT/BD/154693/2023, https://doi.org/10.54499/PRT/BD/154693/2023) under the protocol “Centro para a Valorização do Barroso–Património Agrícola Mundial–Valor Barroso”. Joana Martins would like to acknowledge FCT–Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, I.P. for the support and individual grant (2023.05610.BDANA, https://doi.org/10.54499/2023.05610.BDANA). Eva Olo-Fontinha would like to acknowledge FCT–Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, I.P. for the support and individual grant 2024.06281.BDANA.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Council Recommendation on Stepping Up EU Actions to Combat Antimicrobial Resistance in a One Health Approach (OJ C 220). 2023. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=oj:JOC_2023_220_R_0001 (accessed on 24 December 2025).

- Monciardini, P.; Iorio, M.; Maffioli, S.; Sosio, M.; Donadio, S. Discovering new bioactive molecules from microbial sources. Microb. Biotechnol. 2014, 7, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrado, R.; Gomes, T.C.; Roque, G.S.C.; De Souza, A.O. Overview of bioactive fungal secondary metabolites: Cytotoxic and antimicrobial compounds. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pham, J.V.; Yilma, M.A.; Feliz, A.; Majid, M.T.; Maffetone, N.; Walker, J.R.; Kim, E.; Cho, H.J.; Reynolds, J.M.; Song, M.C.; et al. A review of the microbial production of bioactive natural products and biologics. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, N.P. Fungal secondary metabolism: Regulation, function and drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziemert, N.; Alanjary, M.; Weber, T. The evolution of genome mining in microbes–a review. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2016, 33, 988–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurkolis, F. Marine bioactives: Pioneering sustainable solutions for advanced cosmetics and therapeutics. Pharmacol. Res. 2025, 218, 107868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benameur, T.; Soleti, R.; Panaro, M.A.; La Torre, M.E.; Monda, V.; Messina, G.; Porro, C. Curcumin as prospective anti-aging natural compound: Focus on brain. Molecules 2021, 26, 4794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjørklund, G.; Shanaida, M.; Lysiuk, R.; Butnariu, M.; Peana, M.; Sarac, I.; Strus, O.; Smetanina, K.; Chirumbolo, S. Natural compounds and products from an anti-aging perspective. Molecules 2022, 27, 7084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindequist, U. Marine-derived pharmaceuticals–challenges and opportunities. Biomol. Ther. 2016, 24, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzkar, N.; Jahromi, S.T.; Poorsaheli, H.B.; Vianello, F. Metabolites from marine microorganisms, micro, and macroalgae: Immense scope for pharmacology. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, A.; Vieira, H.; Gaspar, H.; Santos, S. Marketed marine natural products in the pharmaceutical and cosmeceutical industries: Tips for success. Mar. Drugs 2014, 12, 1066–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blunt, J.W.; Carroll, A.R.; Copp, B.R.; Davis, R.A.; Keyzers, R.A.; Prinsep, M.R. Marine natural products. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2018, 35, 8–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, L.T. Impact of marine chemical ecology research on the discovery and development of new pharmaceuticals. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, R.; Nawaz, T. Medicinal plants and human health: A comprehensive review of bioactive compounds, therapeutic effects, and applications. Phytochem. Rev. 2025, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanasov, A.G.; Waltenberger, B.; Pferschy-Wenzig, E.M.; Linder, T.; Wawrosch, C.; Uhrin, P.; Temml, V.; Wang, L.; Schwaiger, S.; Heiss, E.H.; et al. Discovery and resupply of pharmacologically active plant-derived natural products: A review. Biotechnol. Adv. 2015, 33, 1582–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, G.; Romanucci, V.; De Marco, A.; Zarrelli, A. Triterpenoids from Gymnema sylvestre and their pharmacological activities. Molecules 2014, 19, 10956–10981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dincheva, I.; Badjakov, I.; Galunska, B. New Insights in the Research on Bioactive Compounds from Plant Origins with Nutraceutical and Pharmaceutical Potential II. Plants 2025, 14, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGaw, L. Use of plant-derived extracts and bioactive compound mixtures against multidrug resistant bacteria affecting animal health and production. In Fighting Multidrug Resistance with Herbal Extracts, Essential Oils and Their Components; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2025; pp. 291–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feliziani, G.; Bordoni, L.; Gabbianelli, R. Regenerative Organic Agriculture and Human Health: The Interconnection Between Soil, Food Quality, and Nutrition. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, F.; Cappitelli, F. Plant-derived bioactive compounds at sub-lethal concentrations: Towards smart biocide-free antibiofilm strategies. Phytochem. Rev. 2013, 12, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inchingolo, A.D.; Inchingolo, A.M.; Malcangi, G.; Avantario, P.; Azzollini, D.; Buongiorno, S.; Viapiano, F.; Campanelli, M.; Ciocia, A.M.; De Leonardis, N.; et al. Effects of Resveratrol, Curcumin and Quercetin Supplementation on Bone Metabolism—A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koehn, F.E.; Carter, G.T. The evolving role of natural products in drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2005, 4, 206–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanasov, A.G.; Zotchev, S.B.; Dirsch, V.M.; The International Natural Product Sciences Taskforce; Supuran, C.T. Natural products in drug discovery: Advances and opportunities. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 200–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, A.L.; Edrada-Ebel, R.; Quinn, R.J. The re-emergence of natural products for drug discovery in the genomics era. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2015, 14, 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chintada, V.; Golla, N. Exploring the therapeutic potential of bioactive compounds from plant sources. In Biotechnological Intervention in Production of Bioactive Compounds. Sustainable Landscape Planning and Natural Resources Management; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, M.; Khalid, R.; Afzal, M.; Anjum, F.; Fatima, H.; Zia, S.; Rasool, G.; Egbuna, C.; Mtewa, A.G.; Uche, C.Z.; et al. Phytobioactive compounds as therapeutic agents for human diseases: A review. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11, 2500–2529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demain, A.L.; Fang, A. The natural functions of secondary metabolites. In History of Modern Biotechnology I. Advances in Biochemical Engineering/Biotechnology; Fiechter, A., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001; Volume 69, ISBN 978-3-540-44964-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichersky, E.; Lewinsohn, E. Convergent evolution in plant specialized metabolism. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2011, 62, 549–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elshafie, H.S.; Camele, I.; Mohamed, A.A. A comprehensive review on the biological, agricultural and pharmaceutical properties of secondary metabolites based-plant origin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croteau, R.; Kutchan, T.M.; Lewis, N.G. Natural products (secondary metabolites). Biochem. Mol. Biol. Plants 2000, 24, 1250–1319. [Google Scholar]

- Ncube, B.; Van Staden, J. Tilting plant metabolism for improved metabolite biosynthesis and enhanced human benefit. Molecules 2015, 20, 12698–12731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, A.L. Natural products in drug discovery. Drug Discov. Today 2008, 13, 894–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leuci, R.; Brunetti, L.; Poliseno, V.; Laghezza, A.; Loiodice, F.; Tortorella, P.; Piemontese, L. Natural compounds for the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases. Foods 2020, 10, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salam, U.; Ullah, S.; Tang, Z.H.; Elateeq, A.A.; Khan, Y.; Khan, J.; Khan, A.; Ali, S. Plant metabolomics: An overview of the role of primary and secondary metabolites against different environmental stress factors. Life 2023, 13, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samtiya, M.; Aluko, R.E.; Dhewa, T.; Moreno-Rojas, J.M. Potential Health Benefits of Plant Food-Derived Bioactive Components: An Overview. Foods 2021, 10, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, D.J.; Cragg, G.M. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the nearly four decades from 01/1981 to 09/2019. J. Nat. Prod. 2020, 83, 770–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cragg, G.M.; Pezzuto, J.M. Natural products as a vital source for the discovery of cancer chemotherapeutic and chemopreventive agents. Med. Princ. Pract. 2016, 25, 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batool, T.; Ali, R.W.; Nawaz, M.; Khan, S.; Mehmood, K.; Hassan, A.; Javed, M.; Jamil, W. Biotechnological techniques for sugarcane crop improvement, applications and challenges. J. Crop Sci. Biotechnol. 2025, 28, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamgir, A.N.M. Classification of drugs, nutraceuticals, functional food, and cosmeceuticals; proteins, peptides, and enzymes as drugs. In Therapeutic Use of Medicinal Plants and Their Extracts: Volume 1: Progress in Drug Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; Volume 73, ISBN 978-3-319-63862-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, K.; Singh, A.K.; Jabeen, R. Nutraceuticals and functional foods: The foods for the future world. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 56, 2617–2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koca, B.E.; Sarıtaş, S.; Bechelany, M.; Karav, S. The Functional Role of Polyphenols Across the Human Lifespan. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, D.; Guo, Y.; Ali, I.; Lin, J.; Xu, Y.; Yang, M. Accumulation characteristics of plant flavonoids and effects of cultivation measures on their biosynthesis: A review. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 215, 108960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassanein, E.H.; Althagafy, H.S.; Baraka, M.A.; Abd-Alhameed, E.K.; Ibrahim, I.M.; Abd El-Maksoud, M.S.; Mohamed, N.M.; Ross, S.A. The promising antioxidant effects of lignans: Nrf2 activation comes into view. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 2024, 397, 6439–6458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Z.; Cao, Q.; Deng, Z. Unveiling the Power of Flax Lignans: From Plant Biosynthesis to Human Health Benefits. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Jitan, S.; Alkhoori, S.A.; Yousef, L.F. Phenolic acids from plants: Extraction and application to human health. Stud. Nat. Prod. Chem. 2018, 58, 389–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepehri, S.; Khedmati, M.; Yousef-Nejad, F.; Mahdavi, M. Medicinal chemistry perspective on the structure–activity relationship of stilbene derivatives. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 19823–19879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahidi, F.; Ambigaipalan, P. Phenolics and polyphenolics in foods, beverages and spices: Antioxidant activity and health effects–A review. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 18, 820–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carocho, M.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. A review on antioxidants, prooxidants and related controversy: Natural and synthetic compounds, screening and analysis methodologies and future perspectives. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 51, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villegas-Aguilar, M.D.C.; Fernández-Ochoa, Á.; Cádiz-Gurrea, M.D.L.L.; Pimentel-Moral, S.; Lozano-Sánchez, J.; Arráez-Román, D.; Segura-Carretero, A. Pleiotropic biological effects of dietary phenolic compounds and their metabolites on energy metabolism, inflammation and aging. Molecules 2020, 25, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosso, G.; Godos, J.; Currenti, W.; Micek, A.; Falzone, L.; Libra, M.; Giampieri, F.; Forbes-Hernández, T.Y.; Quiles, J.L.; Battino, M.; et al. The effect of dietary polyphenols on vascular health and hypertension: Current evidence and mechanisms of action. Nutrients 2022, 14, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, R.; Saqib, F.; Awadallah, S.; Wahid, M.; Latif, M.F.; Iqbal, I.; Mubarak, M.S. Food polyphenols and type II diabetes mellitus: Pharmacology and mechanisms. Molecules 2023, 28, 3996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aghababaei, F.; Hadidi, M. Recent Advances in Potential Health Benefits of Quercetin. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Moreno, E.; Arias-Rico, J.; Jiménez-Sánchez, R.C.; Estrada-Luna, D.; Jiménez-Osorio, A.S.; Zafra-Rojas, Q.Y.; Ariza-Ortega, J.A.; Flores-Chávez, O.R.; Morales-Castillejos, E.M.; Sandoval-Gallegos, E.M. Role of bioactive compounds in obesity: Metabolic mechanism focused on inflammation. Foods 2022, 11, 1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galiniak, S.; Aebisher, D.; Bartusik-Aebisher, D. Health benefits of resveratrol administration. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2019, 66, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magrone, T.; Jirillo, E. The interplay between the gut immune system and microbiota in health and disease: Nutraceutical intervention for restoring intestinal homeostasis. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2013, 19, 1329–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuciniello, R.; Di Meo, F.; Filosa, S.; Crispi, S.; Bergamo, P. The antioxidant effect of dietary bioactives arises from the interplay between the physiology of the host and the gut microbiota: Involvement of short-chain fatty acids. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tako, E. Dietary plant-origin bio-active compounds, intestinal functionality, and microbiome. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panche, A.N.; Diwan, A.D.; Chandra, S.R. Flavonoids: An overview. J. Nutr. Sci. 2016, 5, e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoncini-Silva, C.; Vlad, A.; Ricciarelli, R.; Fassini, P.G.; Suen, V.M.M.; Zingg, J.-M. Enhancing the Bioavailability and Bioactivity of Curcumin for Disease Prevention and Treatment. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racz, L.Z.; Racz, C.P.; Pop, L.-C.; Tomoaia, G.; Mocanu, A.; Barbu, I.; Sárközi, M.; Roman, I.; Avram, A.; Tomoaia-Cotisel, M.; et al. Strategies for Improving Bioavailability, Bioactivity, and Physical-Chemical Behavior of Curcumin. Molecules 2022, 27, 6854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maiti, P.; Dunbar, G.L. Use of Curcumin, a Natural Polyphenol for Targeting Molecular Pathways in Treating Age-Related Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzat Abd El-Hack, M.; Alagawany, M.; Ragab Farag, M.; Tiwari, R.; Karthik, K.; Dhama, K.; Zorriehzahra, J.; Adel, M. Beneficial impacts of thymol essential oil on health and production of animals, fish and poultry: A review. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2016, 28, 365–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, B.; Mishra, A.P.; Shukla, I.; Sharifi-Rad, M.; Contreras, M.d.M.; Segura-Carretero, A.; Fathi, H.; Nasrabadi, N.N.; Kobarfard, F.; Sharifi-Rad, J. Thymol, thyme, and other plant sources: Health and potential uses. Phytother. Res. 2018, 32, 1688–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi-Rad, M.; Varoni, E.M.; Iriti, M.; Martorell, M.; Setzer, W.N.; del Mar Contreras, M.; Salehi, B.; Soltani-Nejad, A.; Rajabi, S.; Tajbakhsh, M.; et al. Carvacrol and human health: A comprehensive review. Phytother. Res. 2018, 32, 1675–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kussmann, M.; Abe Cunha, D.H.; Berciano, S. Bioactive compounds for human and planetary health. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1193848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibeagha-Awemu, E.M.; Omonijo, F.A.; Piché, L.C.; Vincent, A.T. Alternatives to antibiotics for sustainable livestock production in the context of the One Health approach: Tackling a common foe. Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 1605215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Luan, H.; Qiu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, W.; Xu, W.; Wang, F.; Xuan, H.; Song, P. Antibiotic alternatives in livestock feeding. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 989, 179867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acosta, A.; Tirkaso, W.; Nicolli, F.; Van Boeckel, T.P.; Cinardi, G.; Song, J. The future of antibiotic use in Dailivestock. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Mumper, R.J. Plant phenolics: Extraction, analysis and their antioxidant and anticancer properties. Molecules 2010, 15, 7313–7352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papuc, C.; Goran, G.V.; Predescu, C.N.; Tudoreanu, L.; Ștefan, G. Plant polyphenols mechanisms of action on insulin resistance and against the loss of pancreatic beta cells. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 62, 325–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Câmara, J.S.; Perestrelo, R.; Ferreira, R.; Berenguer, C.V.; Pereira, J.A.M.; Castilho, P.C. Plant-derived terpenoids: A plethora of bioactive compounds with several health functions and industrial applications—A comprehensive overview. Molecules 2024, 29, 3861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Fadhel, Y.; Maherani, B.; Aragones, M.; Lacroix, M. Antimicrobial properties of encapsulated antimicrobial natural plant products for ready-to-eat carrots. Foods 2019, 8, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Yu, S.; Kim, J.; Khaliq, N.U.; Choi, W.I.; Kim, H.; Sung, D. Facile fabrication of α-bisabolol nanoparticles with improved antioxidant and antibacterial effects. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellulu, M.S. Obesity, cardiovascular disease, and role of vitamin C on inflammation: A review of facts and underlying mechanisms. Inflammopharmacology 2017, 25, 313–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adegbola, P.; Aderibigbe, I.; Hammed, W.; Omotayo, T. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory medicinal plants have potential role in the treatment of cardiovascular disease: A review. Am. J. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2017, 7, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Mrowicka, M.; Mrowicki, J.; Kucharska, E.; Majsterek, I. Lutein and zeaxanthin and their roles in age-related macular degeneration—Neurodegenerative disease. Nutrients 2022, 14, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Liang, Q.; Balakrishnan, B.; Belobrajdic, D.P.; Feng, Q.J.; Zhang, W. Role of dietary nutrients in the modulation of gut microbiota: A narrative review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahidi, F. Functional foods: Their role in health promotion and disease prevention. J. Food Sci. 2004, 69, R146–R149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simsek, M.; Whitney, K. Examination of primary and secondary metabolites associated with a plant-based diet and their impact on human health. Foods 2024, 13, 1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Fang, M.; Tu, X.; Mo, X.; Zhang, L.; Yang, B.; Wang, F.; Kim, Y.; Huang, C.; Chen, L.; et al. Dietary polyphenols as anti-aging agents: Targeting the hallmarks of aging. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamagata, K. Polyphenols regulate endothelial functions and reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2019, 25, 2443–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-González, M.Á.; Sánchez-Villegas, A. The emerging role of Mediterranean diets in cardiovascular epidemiology: Monounsaturated fats, olive oil, red wine or the whole pattern? Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2004, 19, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Peng, Y.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, L.; Yang, X. Dietary polyphenols: Regulate the advanced glycation end products-RAGE axis and the microbiota-gut-brain axis to prevent neurodegenerative diseases. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 9816–9842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markowiak, P.; Śliżewska, K. Effects of probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics on human health. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevilacqua, A.; Campaniello, D.; Speranza, B.; Racioppo, A.; Sinigaglia, M.; Corbo, M.R. An update on prebiotics and on their health effects. Foods 2024, 13, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaik Mohamed Sayed, U.F.; Moshawih, S.; Goh, H.P.; Kifli, N.; Gupta, G.; Singh, S.K.; Chellappan, D.K.; Dua, K.; Hermansyah, A.; Ser, H.L.; et al. Natural products as novel anti-obesity agents: Insights into mechanisms of action and potential for therapeutic management. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1182937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramaniam, S.; Selvaduray, K.R.; Radhakrishnan, A.K. Bioactive compounds: Natural defense against cancer? Biomolecules 2019, 9, 758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Zhang, G.; Bai, W.; Han, X.; Li, C.; Bian, S. The role of bioactive compounds in natural products extracted from plants in cancer treatment and their mechanisms related to anticancer effects. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 1429869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehelean, C.A.; Marcovici, I.; Soica, C.; Mioc, M.; Coricovac, D.; Iurciuc, S.; Cretu, O.M.; Pinzaru, I. Plant-derived anticancer compounds as new perspectives in drug discovery and alternative therapy. Molecules 2021, 26, 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Guo, P.; Wang, P.; Zheng, S.; Qu, Z.; Liu, N. The review of anti-aging mechanism of polyphenols on Caenorhabditis elegans. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 635768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correia, P.; Araújo, P.; Ribeiro, C.; Oliveira, H.; Pereira, A.R.; Mateus, N.; De Freitas, V.; Brás, N.F.; Gameiro, P.; Coelho, P.; et al. Anthocyanin-related pigments: Natural allies for skin health maintenance and protection. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iqbal, I.; Wilairatana, P.; Saqib, F.; Nasir, B.; Wahid, M.; Latif, M.F.; Iqbal, A.; Naz, R.; Mubarak, M.S. Plant polyphenols and their potential benefits on cardiovascular health: A review. Molecules 2023, 28, 6403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ditano-Vázquez, P.; Torres-Peña, J.D.; Galeano-Valle, F.; Pérez-Caballero, A.I.; Demelo-Rodríguez, P.; Lopez-Miranda, J.; Katsiki, N.; Delgado-Lista, J.; Alvarez-Sala-Walther, L.A. The fluid aspect of the Mediterranean diet in the prevention and management of cardiovascular disease and diabetes: The role of polyphenol content in moderate consumption of wine and olive oil. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Li, Y.; Chen, Q.; Liu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Pan, D.; Yan, N.; Liu, L. Cereal polyphenols inhibition mechanisms on advanced glycation end products and regulation on type 2 diabetes. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 9495–9513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauter, E.R. Cancer prevention and treatment using combination therapy with natural compounds. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2020, 13, 265–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Shan, J.; Zhong, L.; Liang, B.; Zhang, D.; Li, M.; Tang, H. Dietary phytochemicals that can extend longevity by regulation of metabolism. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2022, 77, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, S.; Kolsters, N.; van de Klashorst, D.; Kreuter, E.; Berger Büter, K. An extract of Rosaceae, Solanaceae and Zingiberaceae increases health span and mobility in Caenorhabditis elegans. BMC Nutr. 2022, 8, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marza, S.M.; Munteanu, C.; Papuc, I.; Radu, L.; Purdoiu, R.C. The Role of Probiotics in Enhancing Animal Health: Mechanisms, Benefits, and Applications in Livestock and Companion Animals. Animals 2025, 15, 2986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allemailem, K.S. Antimicrobial potential of naturally occurring bioactive secondary metabolites. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2021, 13, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayon, N.J. High-throughput screening of natural product and synthetic molecule libraries for antibacterial drug discovery. Metabolites 2023, 13, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kari, Z.A.; Téllez-Isaías, G.; Khoo, M.I.; Wee, W.; Kabir, M.A.; Cheadoloh, R.; Wei, L.S. Resveratrol impacts on aquatic animals: A review. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 50, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaoğlan, B.; Alkassab, A.T.; Borges, S.; Fisher, T.; Link-Vrabie, C.; McVey, E.; Ortego, L.; Nuti, M. Microbial pesticides: Challenges and future perspectives for non-target organism testing. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2024, 36, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halder, N.; Sunder, J.; De, A.K.; Bhattacharya, D.; Joardar, S.N. Probiotics in poultry: A comprehensive review. J. Basic Appl. Zool. 2024, 85, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]