Featured Application

The methodology proposed in this study for determining the compressive strength of hemp–lime composites may serve as a foundation for developing a unified testing standard for this type of material used in sustainable construction. The obtained results can be directly applied to the design and evaluation of building envelopes made of hemp–lime composites, ensuring greater repeatability and comparability of test outcomes, as well as optimizing their mechanical and functional properties.

Abstract

The determination of compressive strength of hemp–lime composite (HLC) is currently based on diverse and non-unified approaches, which complicates the direct comparison of results obtained in different studies. This study compares commonly used strength-determination methods using a dedicated experimental dataset and proposes a new, more universal approach, defining compressive strength as the stress corresponding to 1% permanent strain. Cubic specimens (150 × 150 × 150 mm) were produced at three compaction levels (150%, 170%, 190%) and tested under uniaxial compression. Increasing compaction increased density and resulted in compressive strengths of 219, 316, and 349 kPa, respectively. Methods based on fixed strain levels (5% and 10%) showed good repeatability but primarily reflected serviceability limits, whereas those based on loss of linearity or stiffness reduction were less reliable and highly sensitive to curve interpretation. The proposed 1% permanent-strain method accurately captured the onset of irreversible deformation and aligned with the real behavior of hemp–lime infill in frame structures, supporting its use for standardizing compressive-strength testing of hemp–lime composites.

1. Introduction

The construction sector significantly contributes to greenhouse gas emissions, representing one of the major environmental challenges [1]. Increasing requirements concerning energy efficiency and carbon footprint reduction are driving the development of sustainable materials [2,3]. Among them, renewable plant-based resources capable of CO2 sequestration have attracted particular attention [4]. Industrial hemp stands out as a promising aggregate for building composites [5]. Its woody core, known as shiv—a by-product of stem processing for fiber and hemp wool production—is used to manufacture a hemp–lime composite commonly referred to as hempcrete.

Hemp–lime composite exhibits a distinctive mechanical behavior resulting from the combination of two materials with fundamentally different properties: a highly porous, compressible organic aggregate (hemp shiv) and a rigid mineral binder [6,7]. This combination produces an unconventional mechanical response under loading [5], necessitating detailed analysis and a tailored approach to both design and strength assessment. As a material primarily intended for vertical building envelopes—such as external and internal walls—the hemp–lime composite must possess sufficient compressive strength, one of its most critical mechanical characteristics [5]. Due to the distinctive deformation characteristics of the hemp–lime composite and the wide range of stress levels it may exhibit, the literature reports a variety of approaches for determining its compressive strength from the stress–strain response. In some studies, the maximum stress, i.e., the peak point [8], is adopted as the strength criterion, whereas in others the stress corresponding to a total strain of 10% is employed [9,10,11,12,13]. Moreover, researchers have identified four additional, less commonly implemented definitions of compressive strength. This methodological heterogeneity, coupled with the inherent limitations of each approach, leads to inconsistencies in interpretation and hinders the establishment of a coherent framework for evaluating the material’s mechanical performance. Consequently, the present work undertakes a critical comparison of these existing methods and introduces a universal procedure for the determination of compressive strength, which, in the authors’ view, provides the most consistent and broadly applicable basis for its definition.

In this composite, the matrix is a mineral binder, typically based on hydrated lime, while the inclusion phase consists of hemp shiv. The shiv is characterized by high porosity (76 ± 2%) and an elongated prismatic shape [7,14]. Due to its geometry and low bulk density (approximately 110 kg/m3), the hemp–lime composite requires appropriate compression during molding, as the degree of compaction strongly influences its density and resulting compressive behavior [15,16]. To obtain a sufficiently wide range of mechanical responses—necessary for a robust evaluation of the various strength-determination methods examined in this study—specimens were intentionally prepared under different compaction levels. Although compaction is recognized as an influential parameter, its description in the literature is often general and lacks reproducible specification, which further motivated its controlled variation in the experimental program.

While the primary objective of this work is to compare existing definitions of compressive strength and to validate the proposed universal method, the study also introduces a practical procedure for defining and reporting the degree of compaction. This auxiliary contribution enables the effects of compaction-induced changes in mechanical properties to be systematically incorporated into the assessment of strength-determination methodologies.

1.1. Factors Influencing the Compressive Strength of Hemp–Lime Composite

Depending on its composition, production method, and curing stage, hemp–lime composite (HLC) exhibits a wide range of compressive strength values, from 0.06 MPa [9] up to 4.74 MPa [17], with most reported results falling between 0.1 and 1.2 MPa [9,16,18,19,20,21]. The primary factor influencing compressive strength is the composite density, which depends mainly on the binder-to-shiv ratio and the degree of compaction [22]. Increasing the binder content consistently leads to higher density and strength, as demonstrated in multiple studies [9,10,12,18,23,24].

Binder type also significantly affects the mechanical performance of HLC. Studies on hydrated lime-based binders show that hydraulic additives such as Portland cement, hydraulic lime, gypsum, or clay improve compressive strength [12,25]. Although hydraulic binders provide higher early strength than hydrated lime, this difference decreases with longer curing times [19,26]. Magnesium oxide-based binders can yield compressive strengths of up to 2 MPa [27], while hydrated lime composites typically reach 0.2–0.83 MPa [28,29]. The carbonation-driven curing of lime binders leads to a substantial long-term strength increase, accompanied by reduced failure strain [22]. Additionally, specimen orientation affects test results, with samples loaded perpendicular to the casting direction exhibiting higher strength and lower failure strain than those tested parallel to it [30].

The degree of compaction has a pronounced effect on the mechanical performance of hemp–lime composites. Experimental studies have shown that compressing the fresh material under stresses of 0.6–1 MPa, leading to a threefold reduction in volume, can yield densities up to 600 kg/m3. Intensive compaction markedly enhances compressive strength and alters the deformation behavior; the material maintains a monolithic structure even under vertical strains of about 25%. Despite the severalfold increase in strength observed between low- and high-compaction samples, identifying the exact point of failure remains challenging due to the material’s continuous densification during loading. Notably, higher packing density does not significantly affect the composite’s stiffness.

In the present study, three compaction levels were analyzed, corresponding to 30%, 45%, and 60% volume reduction. Increasing compaction from 30% to 60% resulted in a 175% increase in compressive strength, confirming the strong influence of this parameter on mechanical performance. Simultaneously, the reduction in air volume within the structure nearly doubled the material’s density, which led to an approximately 17% increase in thermal conductivity.

1.2. Behavior of Hemp–Lime Composite Under Axial Loading

The key mechanical parameter of hemp–lime composite is its compressive strength, which is typically determined through destructive tests under controlled displacement by analyzing the stress–strain curve. Under compression, the material exhibits elastoplastic behavior, with a short quasi-elastic range followed by a wide plastic region [31,32].

Initially, the mineral binder carries the load, resulting in a rapid stress increase with minimal strain; this phase usually does not exceed 2–3% strain and depends on binder content [19,22,33].

The plastic phase is extensive and can be divided into zones. The first is associated with the progressive closure of voids between and within hemp shiv particles, leading to stress concentrations, aggregate deformation, and local binder cracking [5]. This stage may produce a quasi-linear “plateau” in the stress–strain curve, which is characterized by limited stress growth despite increasing strain, although this feature is not always distinct [19]. As voids close further, the granular skeleton stiffens, and stress growth slows; peak stress may occur here, depending on the binder-to-aggregate ratio [22]. However, a clear stress maximum is often absent or appears only at very large strains (>15%), which brings into question its suitability as an ultimate strength criterion.

Some studies identify a third deformation phase in which the compacted hemp shiv increasingly carries the load, causing the stress–strain curve to continue rising without a clear failure point [34]. In this range, the material response resembles wood loaded perpendicular to the grain, and further compression is possible despite visible damage, likely due to partial carbonation and prolonged binder curing [35].

1.3. Methods for Determining the Compressive Strength of Hemp–Lime Composite

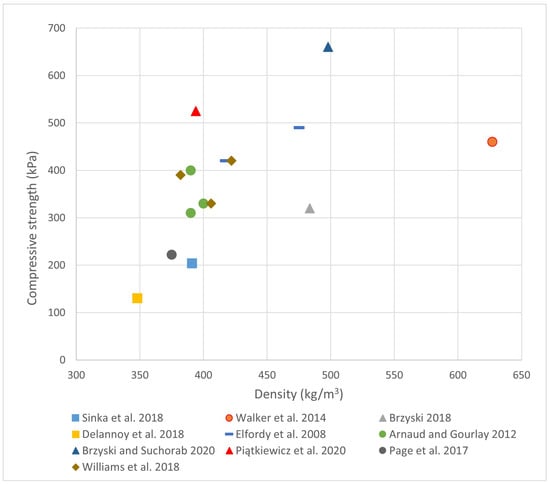

The specific mechanical characteristics of hemp–lime composite, combined with the absence of standardized testing procedures, have led to a wide variety of approaches for determining its compressive strength. Figure 1 presents a compilation of results from selected studies employing the same or very similar binder composition (70% hydrated lime, 20% hydraulic binder, and 10% pozzolanic additives) and a comparable binder-to-shiv ratio ranging from 2.0 to 2.25.

Figure 1.

Compressive strength of hemp–lime composite as a function of density, compiled from various publications using comparable binders and binder-to-shiv ratios, with consideration of possible differences arising from the applied compressive strength testing methods [9,10,12,19,20,22,23,33,36,37].

Analysis of the available data indicates that, even under comparable composite parameters—including binder composition, component proportions, and density—reported compressive strength values differ by as much as a factor of two and range from 0.24 to 0.525 MPa. These discrepancies primarily arise from the application of different testing procedures and evaluation criteria used to determine the compressive strength of the material.

Numerous approaches for determining the compressive strength of hemp–lime composites can be found in the available literature, reflecting the diversity of testing procedures and experimental parameters adopted by different researchers (Table 1). These methods vary primarily in the application of loading, sample geometry and dimensions, loading regime, and criteria used to define the ultimate strength.

All methodologies consistently assume that the loading should be applied slowly to ensure measurement accuracy, although the loading rate may range from 0.2 mm/min to 10 mm/min, depending on the adopted testing protocol [8,9]. The specimen sizes also differ significantly—from small cubic samples with 50 mm edges to cylindrical specimens measuring 110 mm in diameter and 220 mm in height [16,38]. The tests may involve either monotonic or cyclic loading, with some studies suggesting that the loading type has little effect on the measured compressive strength [39].

The principal distinction between methods lies in the definition of the ultimate compressive strength, which can be determined based on various reference points, such as the maximum recorded stress or the point of visible specimen failure. In the literature, six distinct methods for evaluating the compressive strength of hemp–lime composites have been identified and summarized in Table 1, highlighting their specific characteristics and the impact of methodological choices on the obtained results.

Table 1.

Methods for determining the compressive strength of hemp–lime composite.

Table 1.

Methods for determining the compressive strength of hemp–lime composite.

| Method Index | Abbreviated Method Name | Method Description | Testing Conditions | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Deviation from Linearity of the σ–ε Curve | The compressive strength is defined as the stress corresponding to the onset of non-linear behavior on the stress–strain curve. | Cubic specimens 50 × 50 × 50 mm or 100 × 100 × 100 mm; loading rate 50 N/s or 5 mm/min; procedure based on EN 459-2:2010 [40] and EN 196-1:2005 [41] | [19,33] |

| II | 25% Stiffness Reduction | The strength is defined at the point where the instantaneous stiffness decreases to 25% of its maximum value, determined using a 20-point moving average. | Cubic specimens 150 × 150 × 150 mm; loading rate 3 mm/min. | [23,30] |

| III | Serviceability Limit (5% Strain) | The compressive strength is defined as the stress corresponding to 5% strain, adopted as the material’s serviceability limit. | Cubic specimens 50 × 50 × 50 mm. | [38] |

| IV | Stress at 10% Strain | In accordance with EN 826, the compressive strength is defined as the stress at 10% strain. | Specimens with dimensions ranging from 50 × 50 × 30 mm to 100 × 100 × (80–93) mm; loading rate 3–10 mm/min. | [9,10,11,12,13] |

| V | Maximum Load (σmax) | The compressive strength is defined as the stress corresponding to the maximum recorded load during compression. | Cylindrical specimens with 102 mm diameter and 102 mm height, and cubic specimens 150 × 150 × 150 mm; loading rate 0.2–3 mm/min. | [8] |

| VI | Cyclic Compression | The strength is determined during the final loading to failure, preceded by three controlled compression cycles with increasing strain levels (1%, 2%, 3%). | Cylindrical specimens 110 mm in diameter and 220 mm in height; displacement control: 3 mm/min (loading) and 6 mm/min (unloading). | [17,39] |

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. Binder Characteristics

The binder for the hemp–lime composite was made by mixing hydrated non-hydraulic calcium lime of class CL 90S (ALPOL Gips, Trzebinia, Poland). Portland cement of compressive class CEM I 42.5R (Holcim S.A., Malogoszcz, Poland), and Metakaolin of type L05 (Mikrosilika Trade, Warsaw, Poland) in proportions of 75%, 15%, and 10% (wt.), respectively, based on literature and preliminary studies [9,19,20,22,26,33,42,43,44]. These locally sourced materials ensure availability in Poland, cost-effectiveness, and reduced environmental impact. Hydrated lime supports plasticity and moisture regulation due to its porous structure [25]; cement enhances high early compressive strength, enabling rapid formwork removal [45], and metakaolin, a natural pozzolan, improves durability and reduces thermal conductivity while lowering embodied energy compared to pure Portland cement [38,46,47]. Such a composition, aligned with commercial binders, optimizes mechanical, thermal, and hydrothermal properties while minimizing the carbon footprint [48,49].

The combination of hydrated lime, Portland cement, and metakaolin enables us to obtain a hybrid binder system in which the components react simultaneously or sequentially, creating a new type of composite mineral matrix. In case of calcium lime the, main contributor to the matrix, first calcium oxides take part in the reactions of hydration (Equation (1)) (at this stage, hydrated lime also contributes to maintaining a highly alkaline pore solution rather than directly enhancing mechanical resistance), and later—the hydrated phased are subjected to additional hardening through the carbonation process, i.e., neutralization of calcium hydroxide to calcium carbonate under the influence of CO2 in the presence of atmospheric moisture (Equation (2)). This process contributes to microstructural densification of the matrix at later ages.

CaO + H2O → Ca(OH)2,

Ca(OH)2 + CO2 → CaCO3 + H2O,

In case of Portland cement, the most intensive reactions are hydration and hydrolysis of calcium silicates (alite and belite), resulting in formation of calcium silicate hydrates phase (C–S–H) and calcium hydroxide (portlandite) (Equations (3)–(6)), as well as ettringite formed from calcium aluminate and ferro-aluminate phases in the presence of sulfates.

or using abbreviated formulas:

2C3S + 6H → C3S2H3 + 3CH,

2C2S + 4H → C3S2H3 + CH,

2C3S + 6H → C–S–H + 3CH,

2C2S + 4H → C–S–H + CH,

These products are primarily responsible for early-age stiffness and strength development of the matrix. Meanwhile, the calcium hydroxide (i.e., the product of both, lime and Portland clinker constituents hydration) takes part in the pozzolanic reaction with the amorphous silica present in metakaolin, resulting in formation of additional binding phases, mainly C–S–H of low Ca/Si ratio and calcium aluminosilicate hydrates (C–A–S–H) (Equations (7) and (8)) [50] with minor amounts of calcium aluminate hydrates such as gehlenite hydrate or hydrogarnet-type phases. In the presence of carbonate ions, carboaluminate and hydroxy-carboaluminate phases may also form, stabilizing aluminum-bearing reaction products [51].

or using abbreviated formula:

xCa(OH)2 + yAl2O3·zSiO2 + (n − x)H2O → (CaO)x·(Al2O3)y·(SiO2)z·(H2O)n−x,

(CH)x + AySz + H(n−x) → CxAySzH(n−x),

The combined effect of the above-mentioned reactions and mechanisms results in a continuous increase in mechanical resistance over time. Early strength is controlled by cement hydration, while medium- and long-term strength development is governed by pozzolanic reactions and gradual carbonation. Unlike pure lime binders, where strength develops slowly and may remain limited, the lime–cement–metakaolin system exhibits sustained strength growth and improved long-term stability. Importantly, the progressive consumption of calcium hydroxide reduces excessive alkalinity, which is beneficial for limiting mineralization and degradation of hemp particles, thereby contributing to the durability of the hemp–lime composite.

The specific chemical compositions of all hybrid binder components, namely Portland cement CEM I 42.5R, calcium lime CL 90S, and metakaolin L05, are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Chemical composition (expressed by oxides) of the binders used in the research according to the declarations of the manufacturers.

2.1.2. Hemp Shives

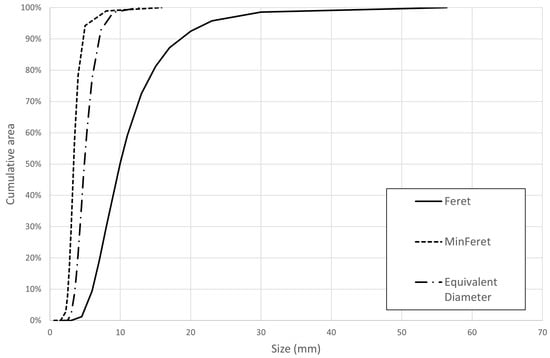

The aggregate used in the study consisted of hemp shives from the Futura 75 industrial hemp variety, commonly employed in construction applications [10,29,52]. Sourced from a single growing season and processed into fibers and shives by the Polish producer (Podlaskie Konopie, Dobrzyniówka, Poland), the material was dedusted and defibrated to ensure uniformity and minimize variables beyond particle size distribution. The hemp underwent natural retting during production. Particle geometry was characterized using image analysis, with 30 independent 3 g shive samples scanned and processed in ImageJ software, version 1.54g (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) to determine basic parameters such as Feret diameter, minimum Feret diameter, area, and perimeter of each particle, following the RILEM BBM Technical Committee protocol [35]. Based on these data, additional parameters, including equivalent diameter, circularity, and elongation, were calculated. Detailed granulometric characteristics of the shives are reported in [53], with results presented in Table 3 and Figure 2.

Table 3.

Characteristics of hemp shiv used in the study.

Figure 2.

Particle size distribution of hemp shives used in the study.

2.2. Experimental Design

To investigate the effect of compaction on the mechanical resistance of the hemp–lime composite, a series of laboratory mixes was prepared with varying degrees of material compaction during production (Table 4). All mixtures were produced and tested under controlled conditions, enabling an assessment of the correlation between the material’s internal structure and its strength parameters

Table 4.

Series of prepared specimens.

Furthermore, based on the results of the mechanical tests, a comparative analysis of the most commonly used methods for determining compressive strength reported in the scientific literature was conducted, and an original method for defining this property was proposed.

2.2.1. Specimen Preparation

In the initial stage of specimen preparation, the quantities of all components of the hemp–lime composite were precisely measured, including the binder constituents (hydrated lime CL 90-S, Portland cement CEM I 42.5 R, and metakaolin), hemp shiv, and water. The dry binder components were thoroughly mixed, after which the premeasured amount of water was added, and the mixture was blended in a planetary mixer with a vertical axis for approximately 2–3 min, until a uniform consistency was achieved, following the procedure applied in [22,54,55]. Subsequently, the hemp shiv was gradually added to ensure even distribution of the binder within the aggregate and to obtain a homogeneous composite. The total mixing time ranged from 6 to 8 min.

After the mixture was prepared, its loose bulk density (without compaction) was determined using a mold measuring 30 × 30 × 8 cm. Based on this loose density and the assumed compaction levels (150%, 170%, and 190%), the mass of material required for each specimen was calculated. The 150% compaction level was selected based on preliminary tests, which showed that a minimum compaction of 145% was necessary to ensure specimen integrity after demolding. Conversely, 190% compaction represented the maximum achievable value when using manual tamping with a hand rammer, while 170% compaction served as an intermediate level, allowing analysis of the influence of varying compaction degrees.

The specimens were formed in cubic molds measuring 15 × 15 × 15 cm using manual tamping (Figure 3). The forming process was carried out in two equal layers, each approximately 7.5 cm thick. The mass of material per layer was equal and corresponded to half of the total calculated mass for a given specimen. After forming the first layer, its surface was lightly loosened to ensure proper bonding with the subsequent layer.

Figure 3.

On the left: mold and hand rammer used for specimen forming. On the right: specimen prepared for the compressive strength test.

After molding, the specimens were left in the molds for 24 h, then demolded and placed in a climatic chamber maintained at a temperature of 20 ± 2 °C and a relative humidity of 60 ± 10%, providing optimal conditions for carbonation [22]. The specimens were cured for 28 days, after which they were weighed and measured to determine their final density.

2.2.2. Compressive Strength Testing

The compressive strength tests were carried out after 28 days of curing, following the procedure described in [17]. Cubic specimens measuring 15 × 15 × 15 cm were weighed and measured prior to testing to determine their density.

Compressive strength and the shape of the stress–strain curves were determined through destructive compression tests performed using an Instron 3382 testing machine with a maximum load capacity of 100 kN. The specimens were compressed at a constant crosshead displacement rate of 5 mm/min, in a direction parallel to the forming and compaction axis, corresponding to the typical orientation of material load transfer in shuttering technology [30]. A steel plate (8 mm thick) was placed on each specimen to ensure uniform contact with the machine’s movable platen. Parameters such as load, displacement, and stress were recorded using the Instron Bluehill 2 software (Instron, Norwood, MA, USA), which generated real-time stress–strain curves.

Before each test, a preload of approximately 0.02 kN was applied to minimize the effect of surface irregularities, after which the displacement measurement was zeroed. The influence of the steel plate was neglected in calculations, as its mass accounted for less than 2% of the lowest recorded strength value. The compression test was terminated when the strain reached 13.3% or when a noticeable stress drop occurred. All key steps of the experimental procedure are presented in the experimental flow chart (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Experimental flow chart of specimen preparation and compression testing.

Due to the absence of a standardized procedure for determining the compressive strength of hemp–lime composite, five methods from the scientific literature were applied, along with a proposed method. The cyclic loading method was omitted because of the monotonic nature of the loading used. According to [39], a comparison between monotonic and cyclic loading showed no significant differences in the determined compressive strength values.

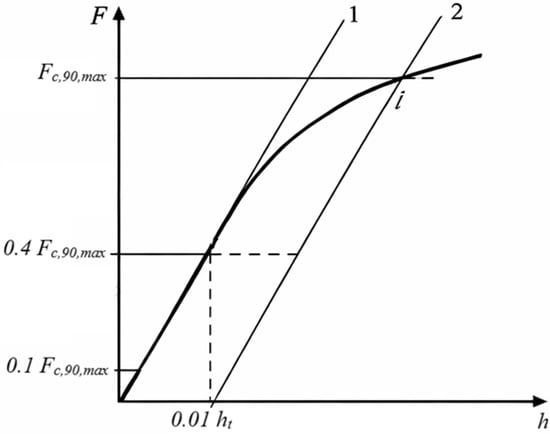

The proposed method in this study defines the compressive strength as the stress corresponding to 1% permanent strain of the material. Considering the mechanical behavior of hemp–lime composite, the approach was based on EN 408:2010+A1:2012 [56], which specifies procedures for determining the compressive strength of wood perpendicular to the grain. The choice of a 1% permanent strain criterion was motivated by the assumption that the tested material is designed to interact with timber structures in applications such as walls, floors, and roofs, where permanent strain is defined as the irreversible deformation remaining after unloading.

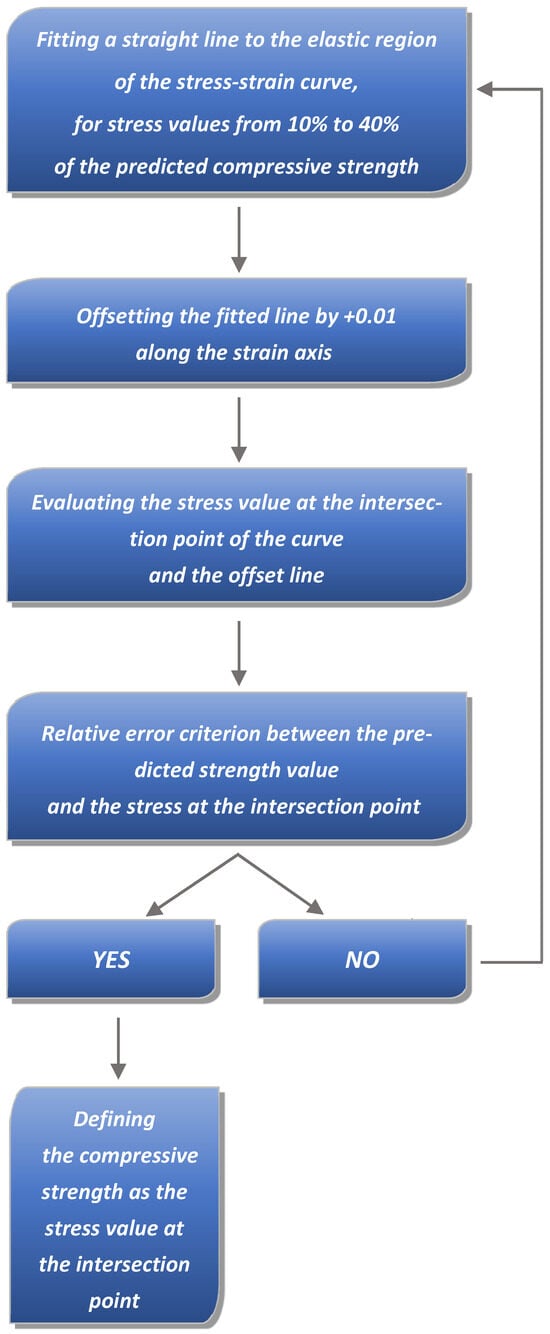

This method involved an initial estimation of the expected compressive strength of each specimen, followed by fitting a linear trend line using the least squares method to the elastic portion of the curve (up to 40% of the estimated strength, Figure 5), referred to as the initial curve. By shifting this line 1% to the right along the strain axis, an offset line was obtained. The intersection point of this offset line with the experimental stress–strain curve, recorded by the Instron Bluehill software, was taken as the compressive strength of the composite. The schematic representation of the proposed method is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 5.

Load–deformation diagram illustrating the procedure for determining compressive strength, where F is the applied load, h the deformation, Fc,90,max the maximum load, and ht the specimen height [56]. Line 1—linear trend line fitted to the elastic portion of the curve. Line 2—offset line obtained by shifting Line 1 by 1% along the strain axis.

Figure 6.

Flowchart of the procedure for determining compressive strength using the proposed method.

3. Results

3.1. Samples Density

An increase in the compaction level of the hemp–lime composite during the forming stage by 20% and 40% resulted in a corresponding increase in material density by 13.6% and 18.7%, respectively (Table 5). The standard deviation for series HLC.150 and HLC.190 was low, at 5.2–5.3 kg/m3, indicating good repeatability. The intermediate series, HLC.170, exhibited a noticeably higher standard deviation of 14.8 kg/m3, suggesting slightly greater variability in material homogeneity.

Table 5.

Density of specimens prepared for compressive strength testing.

3.2. Compressive Strength

Visual observation of specimens during compression testing revealed characteristic failure mechanisms (Figure 7). During the initial loading stage, no discernible changes in the specimen structure were observed. With increasing load, acoustic emissions in the form of intermittent cracking became evident, suggesting the onset of microdamage within the binder matrix. With further increase in load, the specimens exhibited progressive lateral bulging. The deformation was generally symmetric; however, local stress concentrations and bulging patterns depended on the spatial distribution of aggregate particles within the composite. More pronounced bulging occurred in regions with weaker interlocking of hemp shiv particles, allowing their displacement beyond the original specimen boundaries. The observed failure mechanisms showed a clear dependence on the degree of compaction applied during specimen formation. Specimens with lower compaction (HLC.150) exhibited detachment of larger clusters of hemp shiv particles, resulting in more pronounced surface degradation. In contrast, specimens with higher compaction (HLC.190) showed markedly reduced surface damage, with particle detachment largely limited to individual aggregate elements. As the loading process continued, visible cracks began to appear in the material and propagated along the aggregate particles. Their distribution was irregular and non-repetitive, governed by the random arrangement of hemp shiv within the composite. No distinct failure surface or well-defined fracture plane typical of brittle materials was observed. The highest damage intensity occurred in the central region of the specimens, across the cross-section, where lateral bulging and detachment of hemp shiv particles were most pronounced. Despite progressive damage and visible structural degradation, detached particles did not fully separate from the composite but remained partially connected through residual binder bridges and mechanical interlocking with adjacent aggregate elements. Throughout the plastic deformation phase, the specimens exhibited a continuous increase in stress without reaching a distinct maximum within the investigated strain range.

Figure 7.

Failure progression of hemp–lime composite specimens during compression testing at 2% strain intervals (0–18%). The images demonstrate characteristic features including gradual lateral bulging, progressive particle detachment, and crack formation along aggregate particles, with maximum damage concentration in the mid-height region.

With reference to the stress–strain response of the material, the initial loading stage, typically up to a relative strain of ε = 1%, was characterized by a run-in phase. This was attributed to surface irregularities of the specimens formed during compaction, as well as to the composite’s structural characteristics, where the aggregate phase constitutes the dominant volume fraction. To minimize the influence of this initial effect on further analysis, a linear extrapolation of the elastic section of the stress–strain curve was performed on its intersection with the strain axis, ensuring consistent curve alignment between specimens.

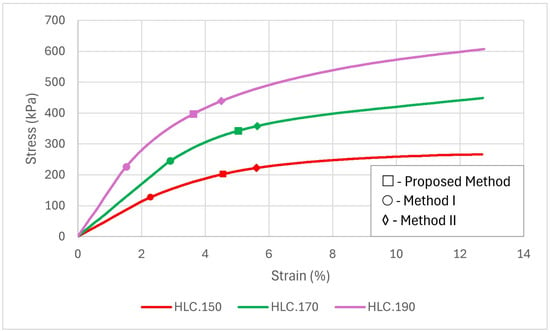

After eliminating this initial effect—and in some cases, from the very beginning of loading—a clearly defined linear-elastic phase was observed, characterized by the steepest slope (highest stiffness) and an almost perfectly straight relationship between stress and strain. In this range, stress increased most rapidly with strain. Around ε ≈ 2–3%, a gradual transition to the plastic phase occurred, during which the rate of stress increase significantly decreased while strains grew more rapidly (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Stress–strain response of representative specimens under compression, with reference points corresponding to compressive strength determined using Method I, Method II, and the proposed method.

For some specimens, the boundary between the elastic and plastic regions was difficult to identify precisely, which introduced uncertainty in defining the yield point according to Method I. Despite substantial strain accumulation with only minor stress increase, none of the tested specimens reached a distinct peak stress (maximum on the curve) within the analyzed range. After approximately ε = 7%, the stress increase became minimal but continued up to the end of the test. The HLC.190 series displayed a more pronounced stress increase at this stage compared with HLC.150 and HLC.170.

The tests were terminated when the specimen shortening reached 20 mm, corresponding to a relative strain of ε = 13.3%, in accordance with the procedure adopted in [34]. Up to this point, no stress drop was observed in any of the specimens. Due to the absence of a peak on the stress–strain curves, two of the six evaluated methods—Method V and Method VI, which require identification of maximum stress—could not be applied and were therefore excluded from further comparison.

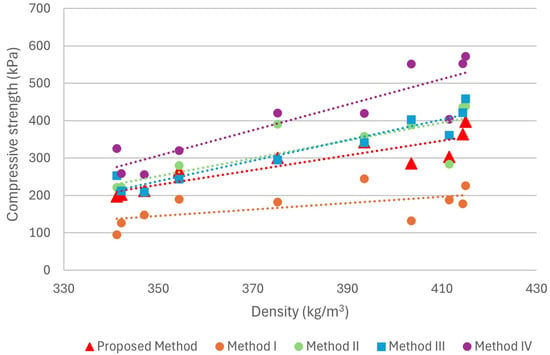

The stress values determined using the remaining methods, along with the proposed method, are presented in Table 6. Figure 9 illustrates the relationship between compressive strength and density for all tested specimens in each series. In addition, the complete dataset is provided in Appendix A.

Table 6.

Compressive strength (kPa) of tested series according to different methods.

Figure 9.

Compressive strength in relation to the density of the tested series. The dashed lines in each color represent the trend lines for each method.

In Methods III and IV, the strain corresponding to the measured stress has a fixed value, whereas in the remaining methods, this parameter is variable and provides important information when comparing the obtained strength values. The strain values corresponding to the ultimate stress in Methods I and II and in the proposed method are summarized in Table 7.

Table 7.

Strain values (%) at the point of compressive strength determination according to different methods.

An analysis of these data indicates that, in all three methods, the ultimate strain decreases with increasing compaction level of the material. This implies that, for composites with higher strength, the point at which the reference value is determined occurs closer to the initial (elastic) segment of the stress–strain curve.

4. Discussion

The observed specimen behavior during compression is consistent with the elastoplastic behavior described in the literature for hemp–lime composites with specific binder-to-aggregate ratios. The mechanism of gradual particle detachment while maintaining their partial connection confirms the phenomenon described in previous studies, where local cracking of the mineral matrix occurs around the highly compressible aggregate, leading to progressive damage accumulation rather than sudden structural collapse.

The absence of a clearly defined failure surface or distinct fracture plane is a fundamental characteristic of hemp–lime composites under compressive loading, resulting from their unique structure. Unlike conventional concrete or masonry materials, which exhibit classical failure modes with well-defined crack patterns or shear planes, hemp–lime composites are characterized by distributed damage patterns. This behavior results from the fact that the soft, highly compressible organic aggregate continues to deform plastically even after visible damage to the mineral binder has occurred.

The continuous increase in stress observed throughout the plastic deformation phase occurred without a distinct maximum. This behavior supports hypotheses reported in the literature that progressively densified hemp shiv gradually assumes load-bearing capacity as composite compaction proceeds. As a result, defining compressive strength using traditional peak-stress criteria becomes impractical. The observed failure behavior, therefore, indicates that hemp–lime composites should be evaluated using criteria that reflect their elastoplastic response and gradual densification mechanism, rather than conventional strength assessment methods developed for materials with well-defined failure surfaces.

Method I, which defines compressive strength based on the transition of the stress–strain curve from the elastic to the plastic region, exhibited the highest standard deviation among all of the analyzed approaches. In hemp–lime composites, this transition is often poorly defined, and in some samples, the elastic phase is nearly absent. Consequently, determining the strength required a subjective interpretation of the curve, increasing both result uncertainty and variability between analyses. Method I also yielded the lowest strength values, which can be attributed to the very short elastic range typical of hemp–lime composites—often not exceeding approximately 3% strain. Notably, this was the only method that indicated a higher strength for the HLC.170 series than for HLC.190, a result likely caused by the difficulty in precisely identifying the inflection point on the curve when the elastic phase is limited. In contrast, all other methods demonstrated consistent trends, showing an increase in strength with increasing density or compaction level, in agreement with findings reported in the literature.

Method II produced values comparable to those of Method III, with strains corresponding to a 25% reduction in instantaneous stiffness ranging between 4.9% and 5.3%. However, the standard deviation of the strain value at the limit point was the highest among all analyzed methods, and the relative error of stress—except for Method I—was also among the largest. This indicates significant variability of results obtained using this approach. Analysis of the stress–strain curves revealed that this method is particularly sensitive to the curve shape and the degree of “flattening.” When the curve exhibits a distinct elastic phase with a steep initial slope, followed by an abrupt transition to the plastic region, the point corresponding to 25% stiffness reduction appears relatively early. Conversely, for curves with a gentle slope from the beginning of loading—where stiffness decreases gradually over a wider strain range—the point occurs at much higher strain values.

Similar limitations of this method were also reported in a previous study [57], where some hemp–lime composite series did not reach a 25% stiffness reduction within the strain range of 0–20%. It was shown that this point could appear at strains as low as 4% for mixes with higher initial stiffness and as high as 7% for those with lower stiffness and a less distinct elastic phase. This led to situations in which a mix with a lower binder content—and consequently lower stiffness—exhibited a higher apparent strength than a stiffer mix, emphasizing the strong sensitivity of Method II to the shape of the stress–strain curve.

Methods III and IV were characterized by the lowest standard deviation among all analyzed approaches. In particular, Method IV, applied analogously to testing of insulation materials such as EPS, showed a standard deviation more than two times lower than that of Methods I and II and that of the proposed method. Both methods also exhibited a consistent increase in strength with higher compaction levels: approximately 44% between the HLC.170 and HLC.150 series and 90% between HLC.190 and HLC.150. While the strength increase between the least and moderately compacted samples was comparable across all methods (averaging about 45%), the difference between HLC.150 and HLC.190 was most pronounced in Methods III and IV.

During the analysis, an additional limitation was identified for Methods III and IV, in which compressive strength is defined as the stress corresponding to a specific strain level. These methods proved to be sensitive to material behavior in the initial loading phase, where, due to the composite’s granular structure, deformation increases nonlinearly, showing a characteristic “run-in” effect. Despite applying a preliminary preload to minimize surface irregularities, the duration of this initial phase varied between samples, resulting in direct strain-axis shifts and affecting the stress values corresponding to fixed strain levels. This reduced both repeatability and comparability of results. As discussed earlier regarding curve extrapolation, this issue can be mitigated by omitting the initial unstable portion of the curve and extending the linear section back to its intersection with the strain axis. Applying such a correction minimizes the influence of surface irregularities during the initial loading phase and yields more representative stress values at defined strain levels.

Within the proposed method, the compressive strength of the HLC.150 and HLC.190 samples increased; however, this improvement was the smallest among all analyzed approaches, amounting to 59%. A noticeable yet stable increase in strength was obtained with a relative error slightly lower than in Methods I and II. Unlike Methods V and VI—which rely on the maximum stress value as the failure criterion—the proposed method is based on the assumption that the failure of a hemp–lime composite cannot be defined by the peak of the compressive stress–strain curve. As demonstrated by the experimental data, such a maximum may either not occur or may appear only after irreversible structural changes have already taken place within the composite. Likewise, using the total strain as the failure criterion—as adopted in Methods III and IV—is inappropriate, as it disregards the elastic component of the material response. Consequently, depending on the Young’s modulus, the same total strain value may correspond to different stages of deformation and, therefore, different levels of material degradation.

In contrast, the proposed method relies on permanent strain, which provides a direct and unambiguous measure of irreversible deformation in the tested specimen. This approach is consistent with established engineering standards, where analogous criteria are employed, for example, to determine the elastic and plastic limits of metals or to assess the compressive strength of wood loaded perpendicular to the grain.

In view of the above, the authors recommend adopting a permanent strain of 1% as the failure threshold, following the convention used in wood mechanics and considering that hemp–lime composites frequently interact structurally with timber components in construction applications. It should be noted, however, that this method is not applicable to elastobrittle composites with a high binder content, for which the traditional maximum-stress approach remains the more appropriate criterion.

5. Conclusions

The analysis of the conducted tests revealed significant differences among the methods commonly used in the literature to determine the compressive strength of hemp–lime composites. The results confirm that the choice of testing procedure has a direct impact on the interpretation of the material’s mechanical behavior, which, due to its highly porous structure and nonlinear deformation characteristics, does not exhibit a typical stress–strain curve. Consequently, traditional criteria based on maximum load are insufficient and lead to results that are difficult to compare across different laboratories.

Among the analyzed approaches, the methods based on constant strain levels (5% and 10%) exhibited relatively consistent results for the specific material type examined. It should be emphasized, however, that these methods refer more to a serviceability limit state than to material strength, and in this role they perform well. Nevertheless, they lack a solid theoretical basis for defining compressive strength and remain sensitive to several influencing factors—for example, using total strain as a criterion disregards the elastic component of deformation, meaning that the same strain value may correspond to different stages of material degradation depending on the Young’s modulus. Additionally, for samples with uneven loading surfaces, the stress values measured at these strain levels may be under- or overestimated due to nonuniform contact with the press plate during the initial loading phase. To improve the reliability of this approach, the initial portion of the loading curve should be adjusted by extrapolating the linear (elastic) section, thereby minimizing errors arising from imperfect specimen–plate contact.

The proposed method—based on the stress corresponding to 1% permanent strain—can be regarded as the most representative and reliable among the approaches considered, as it directly captures the level of irreversible damage in the material and reflects the actual working conditions of hemp–lime composites in timber-frame systems, where the interaction with wooden elements is structurally significant. Such an approach is consistent with current engineering practice for other materials, including wood, for which the 1% strain criterion is widely accepted. Given the close interaction between hemp–lime composites and timber in building applications, adopting the same threshold is both practical and justified, while future studies may refine this value to reflect material-specific behavior and engineering requirements.

The method based on the loss of linearity exhibited high sensitivity to researcher interpretation and to variations in the curve profile. Moreover, this method may lead to misleading conclusions, such as indicating lower strength values for composites with a higher compaction degree—contradicting the results obtained by other methods. This significantly limits its usefulness for comparative or standardized testing. Similarly, the stiffness reduction method, despite producing results close to those of Method III, showed sensitivity to the variability of the stress–strain curve and is therefore unsuitable for comparing composites with markedly different stiffness levels. The lack of clear reference points in materials with an extended plastic phase makes these approaches poorly repeatable and difficult to standardize.

The degree of compaction was found to have a significant influence on the compressive strength of the hemp–lime composite. An increase in compaction by 40% resulted in an approximately 59% increase in compressive strength, as determined using the proposed method. The present study introduces a unified approach for defining the degree of compaction during the composite manufacturing process, enabling the standardization of specimen forming and improving the comparability of results across different research facilities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.P.; methodology, W.P. and A.P.; software, W.P. and A.P.; validation, W.P. and A.P.; formal analysis, W.P. and A.P.; investigation, W.P.; resources, W.P. and A.P.; data curation, W.P.; writing—original draft preparation, W.P.; writing—review and editing, W.P. and P.N.; visualization, W.P.; project administration, W.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express sincere gratitude to Ernest Przyżecki for his valuable assistance in preparing the samples for the experimental tests, as well as to Piotr Woyciechowski (Warsaw University of Technology), Joanna Julia Sokołowska (Warsaw University of Technology), and Maciej Kalinowski (Warsaw University of Technology) for their valuable substantive support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Detailed results of density and compressive strength tests of all samples.

Table A1.

Detailed results of density and compressive strength tests of all samples.

| Specimen ID | Density (kg/m3) | Proposed Method (kPa) | Method I (kPa) | Method II (kPa) | Method III (kPa) | Method IV (kPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HLC.150.1 | 354.41 | 266.01 | 190.00 | 280.12 | 243.62 | 319.93 |

| HLC.150.2 | 342.13 | 202.39 | 127.00 | 222.23 | 211.74 | 258.39 |

| HLC.150.3 | 347.02 | 212.15 | 148.00 | 208.25 | 209.78 | 255.77 |

| HLC.150.4 | 341.24 | 197.27 | 95.00 | 221.4 | 253.43 | 325.4 |

| HLC.170.1 | 375.23 | 300.83 | 182.00 | 390.91 | 295.18 | 420.35 |

| HLC.170.2 | 411.56 | 303.29 | 188.00 | 283.34 | 360.53 | 403.46 |

| HLC.170.3 | 393.55 | 342.52 | 245.00 | 357.83 | 341.46 | 419.96 |

| HLC.190.1 | 415.01 | 397.08 | 226.00 | 438.99 | 458.17 | 572.44 |

| HLC.190.2 | 403.49 | 285.6 | 132.00 | 388.89 | 402.98 | 551.76 |

| HLC.190.3 | 414.42 | 364.07 | 178.00 | 436.02 | 421.59 | 552.75 |

References

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Glossary; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC): Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; ISBN 9781009325844. [Google Scholar]

- Narloch, P.; Piątkiewicz, W.; Pietruszka, B. The Effect of Cement Addition on Water Vapour Resistance Factor of Rammed Earth. Materials 2021, 14, 2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament and Council of the European Union. Regulation (EU) 2021/1119 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 June 2021 Establishing the Framework for Achieving Climate Neutrality and Amending Regulations (EC) No 401/2009 and (EU) 2018/1999 (European Climate Law); European Parliament and Council of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Skrzypczak, D.; Gorazda, K.; Mikula, K.; Mironiuk, M.; Kominko, H.; Sawska, K.; Evrard, D.; Trzaska, K.; Moustakas, K.; Chojnacka, K. Towards Carbon Neutrality: Enhancing CO2 Sequestration by Plants to Reduce Carbon Footprint. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 966, 178763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardouh, R.; Toussaint, E.; Amziane, S.; Marceau, S. Mechanical Behavior of Bio-Based Concrete under Various Loadings and Factors Affecting Its Mechanical Properties at the Composite Scale: A State-of-the-Art Review. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2024, 23, 100819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghari, N.; Memari, A.M. State of the Art Review of Attributes and Mechanical Properties of Hempcrete. Biomass 2024, 4, 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Lawrence, M.; Ansell, M.P.; Hussain, A. Cell Wall Microstructure, Pore Size Distribution and Absolute Density of Hemp Shiv. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2018, 5, 171945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benfratello, S.; Capitano, C.; Peri, G.; Rizzo, G.; Scaccianoce, G.; Sorrentino, G. Thermal and Structural Properties of a Hemp—Lime Biocomposite. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 48, 745–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinka, M.; Van Den Heede, P.; De Belie, N.; Bajare, D.; Sahmenko, G. Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of Magnesium Binders as an Alternative for Hemp Concrete. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 133, 288–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piątkiewicz, W.; Narloch, P.; Pietruszka, B. Influence of Hemp-Lime Composite Composition on Its Mechanical and Physical Properties. Arch. Civ. Eng. 2020, LXVI, 485–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassoni, E.; Manzi, S.; Motori, A.; Montecchi, M.; Canti, M. Novel Sustainable Hemp-Based Composites for Application in the Building Industry: Physical, Thermal and Mechanical Characterization. Energy Build. 2014, 77, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzyski, P. Hemp-Lime Composite as Wall Material Meeting the Requirements for Sustainable Development in Construction Industry; Lublin University of Technology: Lublin, Poland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- EN 826:2013; Thermal Insulating Products for Building Applications—Determination of Compression Behaviour. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

- Piątkiewicz, W.; Narloch, P.; Wólczyńska, Z.; Mańczak, J. Effect of Hemp Shive Granulometry on the Thermal Conductivity of Hemp–Lime Composites. Materials 2025, 18, 3458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colinart, T.; Glouannec, P.; Chauvelon, P. Influence of the Setting Process and the Formulation on the Drying of Hemp Concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 30, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niyigena, C.; Amziane, S.; Chateauneuf, A. Multicriteria Analysis Demonstrating the Impact of Shiv on the Properties of Hemp Concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 160, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tronet, P.; Lecompte, T.; Picandet, V.; Baley, C. Study of Lime Hemp Concrete (LHC)-Mix Design, Casting Process and Mechanical Behaviour. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2016, 67, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haustein, E. Thermal Insulation Properties of the Lime-Cement Composite with Hemp Shives. Ecol. Eng. 2018, 19, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, R.; Pavia, S.; Mitchell, R. Mechanical Properties and Durability of Hemp-Lime Concretes. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 61, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delannoy, G.; Marceau, S.; Glé, P.; Gourlay, E.; Guéguen-minerbe, M.; Diafi, D.; Nour, I.; Amziane, S. Influence of Binder on the Multiscale Properties of Hemp Concretes. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. 2018, 23, 609–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, J.; Sonebi, M.; Taylor, S.; Amziane, S. The Effect of a Polyacrylic Acid Viscosity Modifying Agent on the Mechanical, Thermal and Transport Properties of Hemp and Rapeseed Straw Concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 235, 117536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnaud, L.; Gourlay, E. Experimental Study of Parameters Influencing Mechanical Properties of Hemp Concretes. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 28, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.; Lawrence, M.; Walker, P. The Influence of Constituents on the Properties of the Bio-Aggregate Composite Hemp-Lime. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 159, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, T.M.; Magniont, C.; Coutand, M. Hemp Concrete Using Innovative Pozzolanic Binder. In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Bio-Based Building Materials, Clermont-Ferrand, France, 22–24 June 2015; RILEM Publications: Bagneux, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sáez-Pérez, M.P.; Brümmer, M.; Durán-Suárez, J.A. A Review of the Factors Affecting the Properties and Performance of Hemp Aggregate Concretes. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 31, 101323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, R.; Pavía, S. Moisture Transfer and Thermal Properties of Hemp—Lime Concretes. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 64, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cigasova, J.; Stevulova, N.; Schwarzova, I.; Junak, J. Innovative Use of Biomass Based on Technical Hemp in Building Industry. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2014, 37, 685–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evrard, A.; Herde, A. De Dynamical Interactions between Heat and Mass Flows in Lime-Hemp Concrete. In Research in Building Physics and Building Engineering; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2006; pp. 69–76. [Google Scholar]

- De Bruijn, P.; Jeppsson, K.-H.; Sandin, K.; Nilsson, C. Mechanical Properties, Water Sorption And Frost Resistance Of Lime-Hemp Cementitious Composites. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2013, 53, 1689–1699. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, J.; Lawrence, M.; Walker, P. The Influence of the Casting Process on the Internal Structure and Physical Properties of Hemp-Lime. Mater. Struct. 2017, 50, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofiane, A.; Laurent, A. Bio-Aggregate-Based Building Materials: Applications to Hemp Concretes, 1st ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, J.; Lawrence, M.; Walker, P. A Method for the Assessment of the Internal Structure of Bio-Aggregate Concretes. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 116, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfordy, S.; Lucas, F.; Tancret, F. Mechanical and Thermal Properties of Lime and Hemp Concrete (“Hempcrete”) Manufactured by a Projection Process. Constr. Build. Mater. 2008, 22, 2116–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzyski, P.; Gładecki, M.; Rumińska, M.; Pietrak, K.; Kubiś, M.; Łapka, P. Influence of Hemp Shives Size on Hygro-Thermal and Mechanical Properties of a Hemp-Lime Composite. Materials 2020, 13, 5383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amziane, S.; Collet, F. Bio-Aggregates Based Building Materials; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2017; ISBN 9789402410303. [Google Scholar]

- Brzyski, P.; Suchorab, Z. Capillary Uptake Monitoring in Lime-Hemp-Perlite Composite Using the Time Domain Reflectometry Sensing Technique for Moisture Detection in Building Composites. Materials 2020, 13, 1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, J.; Sonebi, M.; Amziane, S. Design and Multi-Physical Properties of a New Hybrid Hemp-Flax Composite Material. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 139, 502–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, J.; Sonebi, M.; Taylor, S.; Amziane, S. Effect of Linseed Oil and Metakaolin on the Mechanical, Thermal and Transport Properties of Hemp-Lime Concrete. Acad. J. Civ. Eng. 2017, 35, 124–132. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Picandet, V.; Carre, P.; Lecompte, T.; Amziane, S.; Baley, C.; Thu, T.; Picandet, V.; Carre, P.; Lecompte, T.; et al. Effect of Compaction on Mechanical and Thermal Properties of Hemp Concrete. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. 2011, 14, 545–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 459-2:2010; Building Lime—Part 2: Test Methods. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2010.

- EN 196-1:2005; Methods of Testing Cement—Part 1: Determination of Strength. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2005.

- Kinnane, O.; Reilly, A.; Grimes, J.; Pavia, S.; Walker, R. Acoustic Absorption of Hemp-Lime Construction. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 122, 674–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collet, F.; Pretot, S. Thermal Conductivity of Hemp Concretes: Variation with Formulation, Density and Water Content. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 65, 612–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhakal, U.; Berardi, U.; Gorgolewski, M.; Richman, R. Hygrothermal Performance of Hempcrete for Ontario (Canada) Buildings. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 3655–3664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gołębiewski, M.; Narloch, P.; Piątkiewicz, W.; Wasilewski, I. Trwałość Kompozytów Wapienno-Konopnych w Świetle Różnych Metod Badawczych. Mater. Bud. 2023, 2023, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdellatef, Y.; Kavgic, M. Thermal, Microstructural and Numerical Analysis of Hempcrete-Microencapsulated Phase Change Material Composites. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2020, 178, 115520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerrouki, R.; Benazzouk, A.; Courty, M.; Ben Hamed, H. Potential Use of Matakaolin as a Partial Replacement of Preformulated Lime Binder to Improve Durability of Hemp Concrete under Cyclic Wetting/Drying Aging. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 333, 127389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ip, K.; Miller, A. Life Cycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions of Hemp-Lime Wall Constructions in the UK. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2012, 69, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggieri, G.; Arrigoni, A.; Pelosato, R.; Meli, P.; Sabbadini, S.; Dotelli, G. Life Cycle Assessment of Natural Building Materials: The Role of Carbonation, Mixture Components and Transport in the Environmental Impacts of Hempcrete Blocks. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 149, 1051–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokołowska, J.J. Utilizing Sakurajima Volcanic Ash as a Sustainable Partial Replacement for Portland Cement in Cementitious Mortars. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, M.F.; Sánchez de Rojas, M.I. The Effect of High Curing Temperature on the Reaction Kinetics in MK/Lime and MK-Blended Cement Matrices at 60 °C. Cem. Concr. Res. 2003, 33, 643–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bruijn, P.B.; Jeppsson, K.H.; Sandin, K.; Nilsson, C. Mechanical Properties of Lime-Hemp Concrete Containing Shives and Fibres. Biosyst. Eng. 2009, 103, 474–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narloch, P.; Piątkiewicz, W.; Anysz, H.; Wółczyńska, Z.; Mańczak, J. Digital Image-Based Characterization of Particle Size and Shape Distribution in Industrial Hemp Shives. 2025. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/15664512 (accessed on 25 December 2025).

- Hirst, E. Characterisation of Hemp-Lime as a Composite Building Material; University of Bath: Bath, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Amziane, S.; Arnaud, L. 4. Formulation and Implemtnetation. In Bio-Aggregate-based Building Materials: Applications to Hemp Concretes; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- EN 408:2010+A1:2012; Timber Structures-Structural Timber and Glued Laminated Timber-Determination of Some Physical and Mechanical Properties. Swedish standard: Stockholm, Sweden, 2012.

- Gołębiewski, M.; Pietruszka, B.; Piątkiewicz, W.; Kubiś, M.; Oleksiienko, O. Compressive Strength, Thermal Conductivity, Vapor Permeability and Specific Heat of Hemp-Lime Composites Varying in Density for Wall, Roof and Floor Applications. Materials 2025, 18, 4958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.