Abstract

The artificial ground freezing (AGF) technique is widely used in the construction of subway cross passages due to its advantages of good water sealing, strong adaptability, and minimal environmental impact. However, groundwater seepage adversely affects the formation of the frozen wall. The functional relationship between the content of unfrozen water and the temperature in saturated sandy gravel was obtained using frequency domain reflectometry (FDR). Based on the theories of heat transfer and seepage in porous media, a coupled hydrothermal mathematical model of saturated ground considering phase change was established. This model was verified using results from a model test and a freezing project for a subway cross passage. Building on this, the influence of seepage velocity on the formation and closure time of the frozen wall was studied, and prediction formulas for closure times under different seepage velocities were proposed. The results demonstrate the effectiveness of the VG–Clapeyron model in predicting the unfrozen water content in saturated sandy gravel. Groundwater seepage is the core factor affecting the formation of the frozen wall. As seepage velocity increases, closure times for both the cross passage and the pump room are significantly delayed, and the difference between their respective closure times increases. The upstream sidewall is the weak link in frozen wall expansion under seepage conditions. Monitoring of the temperature field in this area should be strengthened to track the formation of the frozen wall.

1. Introduction

In the context of accelerating urbanization, the construction of subterranean railway systems has emerged as a pivotal strategy for alleviating traffic congestion. In subterranean tunnel networks, cross passages connecting two parallel tunnels are of paramount importance for the purposes of drainage, fire evacuation, and the installation of equipment. Due to their substantial burial depth, intricate geological conditions, and recurrent presence in soft soil layers characterized by high groundwater levels, the AGF finds extensive application in the reinforcement of soil prior to excavation for cross passages, a testament to its exceptional waterproofing properties and adaptability [1]. The technology in question involves the installation of freeze pipes, the circulation of a low-temperature coolant, and the transformation of pore water in the soil into ice. This process creates a closed and high-strength frozen wall, which provides temporary support for safe excavation [2].

However, the hydrogeological environment in which subway tunnels are located is often extremely complex. The dynamic underground seepage field poses one of the most significant challenges to the successful application of AGF [3]. In comparison with static water, seepage continuously carries heat, impacting the freezing front and significantly delaying the closure and development of the frozen wall. Furthermore, this may result in uneven thickness, morphological distortion, or even failure to form a completely closed frozen wall, leaving water seepage channels. In the event of the frozen wall failing during excavation, there is a high probability of catastrophic water and sand inrush accidents. Such incidents pose a serious threat to engineering safety, the surrounding environment, and social order [4]. It is imperative to ascertain the formation mechanism and evolution laws of the frozen wall under the coupled action of seepage and temperature fields in order to ensure the safety and controllability of subway tunnel freezing engineering.

It is evident that model testing constitutes the most direct and controllable means by which to study the mechanism of seepage influence. Scaled physical models are used to simulate the tunnel–cross passage system and systematically investigate the interference mechanism of seepage on the frozen wall formation [5,6]. In order to simulate more realistic conditions, researchers have designed tests considering the interaction of twin tunnels, the non-uniform layout of freeze pipes, and the simulation of heat dissipation boundaries from tunnel segments [7,8,9]. It is evident that these refined tests provide valuable visual phenomena and quantitative data, which facilitate a comprehensive understanding of the influence of seepage under complex boundary conditions. However, extant models still face challenges in restoring the in situ stress state of the prototype, simulating large-scale spatial variability of soil, and modeling the fully coupled hydrothermal–mechanical process over long time scales [10].

Field tests are derived directly from practical applications, and their data reflect the influence of seepage under real geological and construction conditions. It is therefore asserted that these tests possess the highest authority and guiding value. The subways are situated within an urban center, meaning that the test environment is constrained by a multitude of interfering factors. Systematic and research-oriented field tests are relatively scarce, with the majority of results emanating from safety monitoring and post-analysis during construction [11]. In the context of subway freezing projects, a relatively mature monitoring system has been established, typically encompassing temperature monitoring, hydrological monitoring, and deformation monitoring [12,13]. Nevertheless, the restriction of field tests is predicated on the relatively sparse data points, which engenders difficulties in the reconstruction of a complete three-dimensional temperature field and seepage field. The interaction of multiple factors, including variations in the refrigeration system, soil heterogeneity, adjacent construction activities, and other elements, poses a significant challenge in accurately quantifying seepage’s contribution from monitoring data [14].

The utilization of numerical simulation as a tool for the study of seepage problems is imperative owing to the advantages inherent in this approach, namely its low cost, comprehensive information acquisition, and capacity to simulate complex working conditions [15]. The primary focus of this research is the development of a simulation model that is capable of representing coupled processes within multi-physical fields. These fields encompass hydrodynamic, thermal, and mechanical domains [16]. Early numerical analyses frequently simplified the freezing process as a pure heat conduction problem or considered only static groundwater. Subsequent to this, hydrothermal models coupled with Darcy seepage were extensively applied. These models, theoretically based on the Harlan model, solved the energy equation by taking into account the latent heat of phase change and the fluid mass conservation equation by taking into account the water–ice phase change. This enabled preliminary simulation of temperature field distortion and the asymmetric development of the frozen wall caused by seepage [17,18]. Utilizing such models, researchers systematically analyzed the influence of parameters such as seepage velocity, direction, soil thermal conductivity, and latent heat on the closure time and shape of frozen walls [19,20]. Presently, the frontiers of research have advanced to the point where three-field numerical simulations, encompassing hydrothermal and mechanical processes, are now possible. It has been demonstrated that advanced models have the capacity to simultaneously solve the temperature field, seepage field, and stress field. This is achieved by taking into consideration the dynamic changes in unfrozen water content with temperature and pressure in frozen soil, ice–soil structure interaction, and frost heave effects [21,22]. These models have the capacity to reproduce phenomena observed in field monitoring and to predict weak areas of the frozen wall under specific seepage conditions, thus providing a robust theoretical foundation and a predictive tool for the optimization of freezing pipe design and refrigeration technology [23].

Advancements in related research have contributed to the development of multi-field coupling theory and the promotion of the AGF method’s application under complex environmental conditions. However, extant research has focused primarily on the expansion laws of frozen walls for regular pipe layout schemes such as single rows or circles of pipes. The existing literature on the coupled problem of temperature and seepage fields during subway cross passage freezing is limited. The determination of the unfrozen water content is of particular significance. The phenomenon can be attributed to the fact that the unfrozen water content is influenced by a variety of factors, including soil properties and temperature. It is noteworthy that effective solutions for predicting the closure time of cross passage frozen walls under seepage conditions are seldom reported. The present study employs the FDR method to ascertain the functional relationship between unfrozen water content and temperature in saturated sandy gravel. In consideration of the impact of ground temperature on the permeability coefficient and thermophysical parameters during the freezing process, a coupled hydrothermal mathematical model incorporating phase change has been formulated. The model is founded upon the principles of heat transfer and seepage theory in porous media. The present study investigates the impact of seepage velocity on the formation process and closure time of the frozen wall. Prediction formulas for closure time under different flow velocities are proposed, with the aim of providing a reference for the design and construction of freezing engineering under complex environmental conditions.

2. Subway Cross Passage Construction Using the AGF Method

2.1. Project Overview

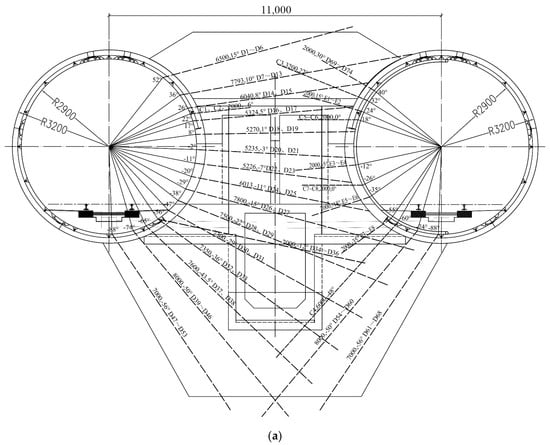

The strata of the No. 3 cross passage in the Caoqiao Station—Jingfengmen Station section of Beijing Metro Line 19 is mainly composed of a sandy gravel layer. This layer is distinguished by its substandard surrounding rock stability, which renders it vulnerable to collapse during the construction process. Evidence from geological exploration data indicates that the sandy gravel layer exhibits a high degree of permeability, with an average groundwater flow velocity of 5.05 m per day. The direction of flow is principally from north to south, aligning closely with the tunnel alignment. To ensure the safety of excavation, the AGF method was utilized for the purpose of ground reinforcement. A total of 82 freeze pipes were drilled for the cross passage and pump room, including 4 penetration holes, numbered D1~D74 and E1~E8. Furthermore, 53 freeze pipes were installed in 15 rows along the tunnel side in conjunction with the freezing station. The installation of 29 freeze pipes was conducted in 7 rows along the tunnel side opposite the freezing station. To facilitate the monitoring of the temperature and closure of the frozen wall, a total of 10 temperature measurement holes were drilled, numbered C1~C10. C1 and C2 were positioned on the tunnel side in close proximity to the freezing station, while C3 to C10 were situated on the opposite tunnel side. The depth of the temperature measurement holes ranged from 0.5 to 6 m, with 3–6 temperature sensors embedded in each, monitoring the development of ground temperature. The configuration of freeze pipes for the cross passage and pump room in the section is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Layout of freezing tubes of the cross passage. (a) Front elevation view of cross passage; (b) side profile of cross passage; (c) cross-sectional view of the opposite side of the cross passage.

2.2. Analysis of Monitoring Result

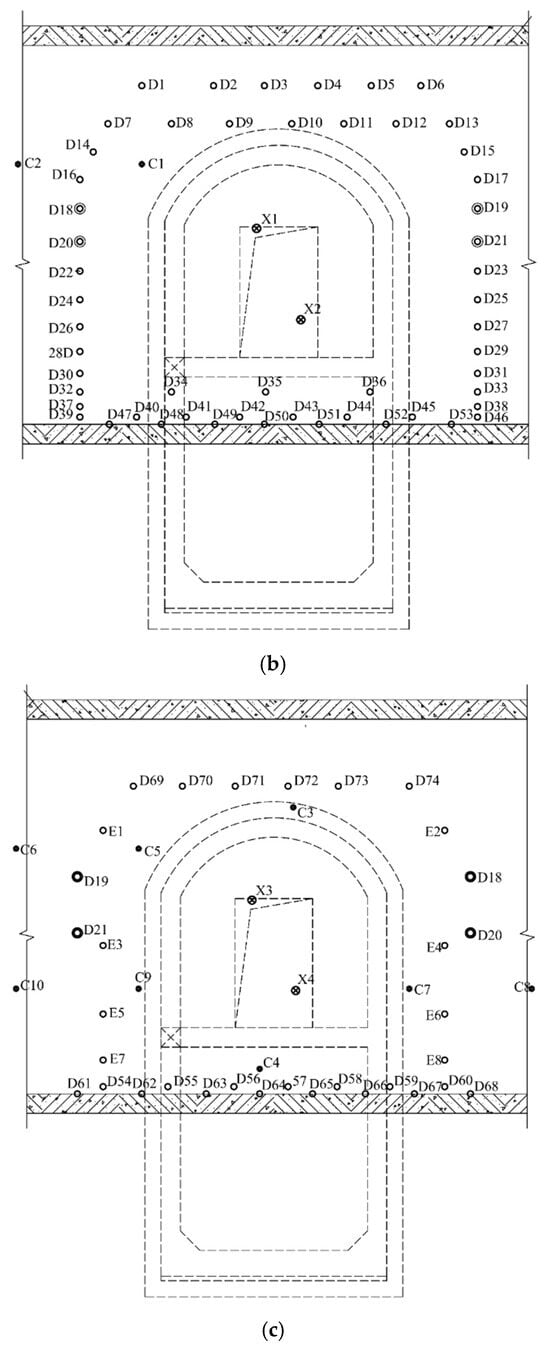

The variation in brine temperature primarily undergoes three stages: rapid cooling, slow cooling, and stabilization, as illustrated in Figure 2. During the initial freezing stage, the brine temperature underwent a rapid decrease, exhibiting average cooling rates of 1.83 °C/day for the output and 1.88 °C/day for the input. During this phase, the temperature difference between the output and input was significant, remaining at approximately 2 °C. As the freezing process continued, the temperature difference between the brine and the ground gradually diminished, resulting in a reduction in the cooling rate. At this stage, the temperature difference between the output and input decreased, stabilizing at approximately 1.0 °C. It has been demonstrated that, upon attaining thermal equilibrium, the temperatures of the output and input gradually stabilize. It is worthy of note that on the 27th day after startup, there was a sudden drop in brine temperature, and the temperature difference between the output and input increased. This was due to the activation of an additional refrigeration unit and an increase in brine flow rate to meet project timeline requirements.

Figure 2.

Temperature variation in output and input brine.

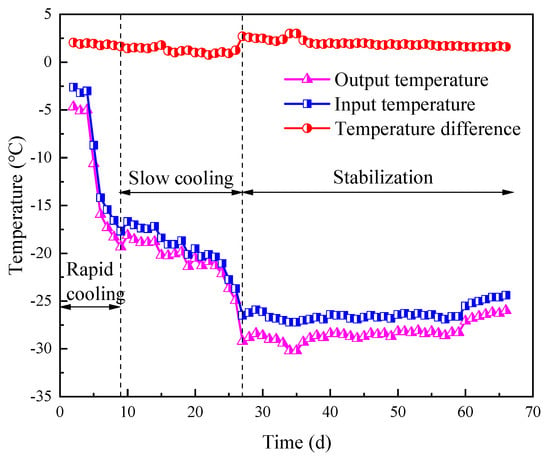

The monitoring results of thermistors C7~C10 at burial depths of 0.5 m, 1.5 m, and 3.0 m are displayed in Figure 3. During the freezing process, the ground temperature primarily underwent three phases: rapid cooling, slow cooling, and stabilization. This is consistent with the variation in the brine temperature, but it exhibits a certain lag. In the subsequent phase of freezing, the excavation of the soil within the cross passage revealed the frozen wall. It is evident that internal thermistors C7 and C9 exhibited a considerable increase in temperature, a phenomenon attributable to the combined influences of air convection and construction activities. During the positive freezing period, the soil remained undisturbed. The temperature of soil is principally influenced by groundwater seepage. The external thermistors C8 and C10 exhibited significantly higher temperatures than the internal thermistors C7 and C9, with C10 registering a higher temperature than C8. The rationale behind this phenomenon is that C10 was situated on the upstream sidewall, oriented toward the direction of water flow, while C8 was positioned on the downstream sidewall, facing away from the water flow. Groundwater seepage has been shown to exacerbate the loss of cooling capacity. Furthermore, the water flow on the side facing the water is found to carry away significantly more cooling capacity than the side facing away from the water. It is therefore imperative that, during the freezing period, temperature monitoring on the upstream sidewall is strengthened in order to ensure the safety of underground excavation construction.

Figure 3.

Comparison of ground temperature at different buried depths: (a) 0.5 m; (b) 1.5 m; (c) 3.0 m.

3. Coupled Hydrothermal Mathematical Model

3.1. Basic Assumptions

Frozen soil is generally considered to be a multiphase system, comprising a soil skeleton, water, ice, and air. The present study makes the assumption that the seepage ground is saturated, and consequently, does not consider the impact of air. Seepage ground is defined as the soil skeleton and water in its initial condition. During the freezing process, the composition of seepage ground changes to include the soil skeleton, water, and ice [24,25]. AGF is a multi-field coupling process involving complex issues such as moving boundaries, phase change, seepage, heat transfer, and stress. The formation of the frozen wall in seepage ground is primarily discussed, ignoring the influence of the stress field on the seepage and temperature fields, and we consider only the mutual influence between the seepage field and temperature field [16,26]. Seepage carries away cold energy from the ground, affecting the temperature field distribution. Changes in temperature affect fluid density and viscosity. With the movement of the freezing front, local permeability and seepage paths in the ground change significantly. To simplify the problem, the main assumptions during the derivation of the mathematical model are as follows [27,28]:

- (1)

- The soil is a continuous, homogeneous, isotropic saturated porous medium.

- (2)

- Groundwater seepage always satisfies the continuity condition and Darcy’s law.

- (3)

- Groundwater is pure water, ignoring the influence of solutes.

- (4)

- Saturated freezing soil satisfies the local thermal equilibrium assumption, and thermal parameters follow the mixture rule.

- (5)

- Heat transfer modes are conduction and convective heat transfer, following Fourier’s law of heat conduction and ignoring the influence of thermal radiation.

3.2. Temperature Field Equation

The transfer of heat occurs via three mechanisms: conduction, convection, and radiation. The AGF method is a process that facilitates heat transfer through the utilization of low-temperature brine that is circulated within freeze pipes. This results in the generation of a temperature gradient between the pipe wall and the surrounding soil. It is evident that groundwater flow is concomitant with convective heat transfer effects. It can, thus, be concluded that the primary mechanisms of heat transfer during the freezing process in seepage ground are conduction and convection [29]. In accordance with the prevailing energy conservation law in the context of porous media, the governing equation for the temperature field in the presence of seepage conditions is expressed as follows:

where is equivalent volumetric heat capacity of the soil; is the equivalent thermal conductivity of the soil; is the seepage velocity vector; is temperature; is time; and is the energy released during the water–ice phase change process.

When dealing with the ice–water phase change in ground freezing engineering, the apparent heat capacity method is selected to quantify the latent heat energy of the phase change. The core of the apparent heat capacity method is to quantify the range of the ice–water phase transition within a specific interval [−3 °C, −0.1 °C], where the latent heat of the phase change exclusively occurs. The energy released during the transformation of pore water to ice can be expressed as follows:

where is the latent heat of water–ice phase change, taken as 334 kJ/kg.

The volume content of each constituent of the soil is subject to variation in accordance with the ground temperature, and its thermophysical parameters are concomitantly subject to change. An alternative approach to characterizing these systems is to integrate the physical parameters and volume content of each component [30]. The equivalent volumetric heat capacity of the soil is expressed using the volume-weighted average method:

where , , are the densities of soil particles, liquid water, and solid ice, respectively; , , are the volume contents of soil particles, liquid water, and solid ice, respectively; , , are the specific heat capacities of soil particles, liquid water, and solid ice, respectively.

The equivalent thermal conductivity of the soil is expressed using the exponent-weighted average method:

where are the thermal conductivities of soil particles, liquid water, and solid ice, respectively.

During ground freezing, the soil particle content is fixed. The change in volume content of each soil component is mainly affected by porosity and the water–ice phase transition, which can be described as follows:

where is the porosity, and is the saturation of the frozen soil.

3.3. Water Field Equation

In accordance with the principles of mass conservation, the governing equation for the seepage field is expressed as follows:

As the advancing freezing front causes a change in the local permeability of the ground, the phenomenon of permafrost thaw occurs. The flow of groundwater is described by the Darcy equation:

where is the dynamic viscosity of water; , are the intrinsic permeability and relative permeability of the aquifer, respectively; is the pore water pressure; and is the gravitational acceleration vector.

The intrinsic permeability is described by the Kozeny–Carman equation [31]:

where is the average particle size, taken as 0.56 mm.

The relative permeability is described by the van Genuchten equation:

where is the saturation coefficient, taken as 0.5.

The viscosity of the fluid varying with temperature is expressed as follows:

3.4. Determination of Unfrozen Water Content

The volumetric unfrozen water content of saturated sandy gravel was determined by means of a small soil moisture sensor (EC-5, manufactured by METER Group, Inc., Washington, DC, USA) in conjunction with a CR1000X data logger (manufactured by Campbell Scientific, Utah, UT, USA) or functions on the principle of FDR. The sensor emits electromagnetic waves of a specific frequency, which travel along and return from the probes, thereby measuring the output voltage of the probes. It is evident that the dielectric constant is considerably influenced by the water content; consequently, the water content can be ascertained from the output voltage. In order to ensure the accuracy of the calibration process, the EC-5 sensor was calibrated using soil samples with water contents of 10% and 15%. The measurement of temperature was facilitated by Pt100 thermistor (manufactured by Northwest Institute of Ecological Resources, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Lanzhou, China), which possess a measurement range of −30 °C to +30 °C and an accuracy of ±0.05 °C.

In order to ensure uniform cooling in all directions, a custom aluminum sample box was fabricated. The dimensions of the box in question were 60 mm in diameter and 80 mm in height, and it was equipped with a top cover. The top cover was designed with reserved holes for the insertion of the moisture sensor and temperature sensor. The prepared sample was then placed in a freeze–thaw test chamber, with the moisture and temperature sensors inserted vertically through the reserved holes in the top cover. The initial ambient temperature was set to 1 °C and was then maintained for a period of 8 h. Once thermal equilibrium had been achieved within the soil sample, a gradual decrease in temperature ensued. The maintenance of each temperature level was conducted for a period of six hours, with the objective of facilitating the attainment of a new hydrothermal equilibrium within the soil sample.

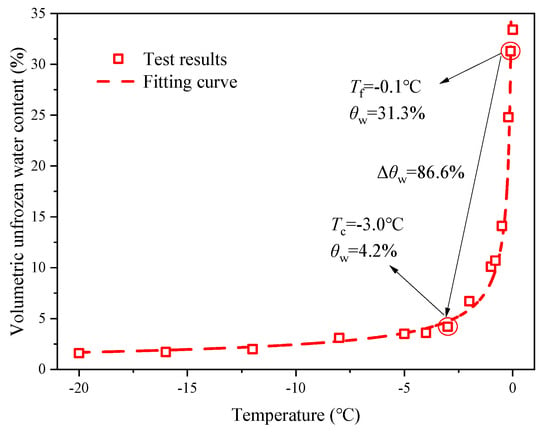

In Figure 4, the relationship between the unfrozen water content and temperature during the freezing process of saturated sandy gravel is illustrated. It has been established that the unfrozen water content of saturated sandy gravel diminishes gradually with decreasing temperature. The freezing characteristic curve displays three distinct phases: an initial rapid decline, a subsequent slow decline, and a final stabilization phase. These phases are analogous to the intense, decelerated, and ceased phases of pore water phase change, respectively. The phase change of water in the ground mainly occurs within the temperature range of −0.1 °C to −3 °C, accounting for 86.6% of the total phase change.

Figure 4.

Soil freezing characteristic curve.

Some scholars have analogized the ice pressure during soil freezing to the air pressure in unsaturated soil, proposing a prediction model for unfrozen water content in frozen soil by combining the van Genuchten soil–water characteristic curve model and the Clapeyron equation [32]:

The saturation of the frozen soil is then described:

where are fitting parameters, taken as 0.003, 0.606, and 1.646, respectively; and are the initial volumetric water content and residual unfrozen water content, taken as 0.32 and 0.042, respectively; and is the freezing temperature of the saturated sandy gravel, taken as −0.1 °C.

A quantitative analysis was conducted of the adaptability of the unfrozen water content prediction model. The present analysis was conducted by means of statistical analysis methods. The root-mean-square error (RMSE) and the coefficient of determination RMSE and R2 are 0.863 and 0.977, respectively. It is worth noting that the reported fitting parameters are site-specific and may vary with soil gradation and fines content. The VG–Clapeyron model demonstrates a high degree of adaptability in predicting the unfrozen water content in saturated sandy gravel, exhibiting a strong correlation between predicted and experimental values. The model’s simplicity in form is noteworthy. It is evident that the VG–Clapeyron model is adopted for the purpose of predicting the variation in unfrozen water content with temperature in saturated sandy gravel.

4. Simulation and Verification

4.1. Model Test

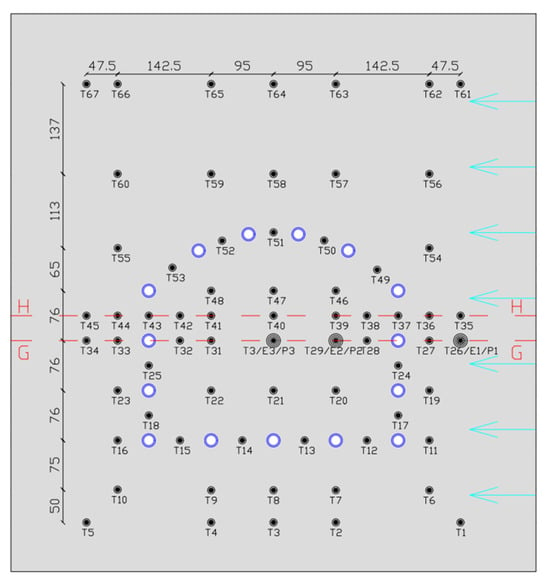

In order to investigate the formation process of the frozen wall under seepage conditions, a model test of a subway cross passage was conducted [9]. Considering the actual geometric dimensions of the cross passage freezing project and the heat dissipation area of the freezing pipes, along with factors such as the test site conditions, equipment processing technology, and the convenience of test operations, the geometric scaling ratio for the model test was determined to be 1:16. The test equipment principally comprised a model box, a refrigeration system, a seepage system, and a monitoring and acquisition system. The internal dimensions of the box were 0.8 m × 0.5 m × 0.8 m, comprising a water inlet chamber, a soil filling chamber, and a water outlet chamber. The refrigeration system was composed of three fundamental components: a chiller, freezing pipes, and a coolant. The coolant employed was ethylene glycol antifreeze, which has a freezing point of −45 °C. The seepage system comprised several essential components, including a constant temperature water tank, a power pump, a flow meter, and a circulation pipeline. The flow velocity could be monitored and regulated in real time using the flow meter and power pump. A total of 67 Pt100 thermistors were embedded in the filled soil, with a measurement range of −50 °C to +50 °C and an accuracy of ±0.1 °C. During the experimental phase, a Campbell CR6 and two multi-channel expansion boards were utilized for the real-time acquisition of monitoring data.

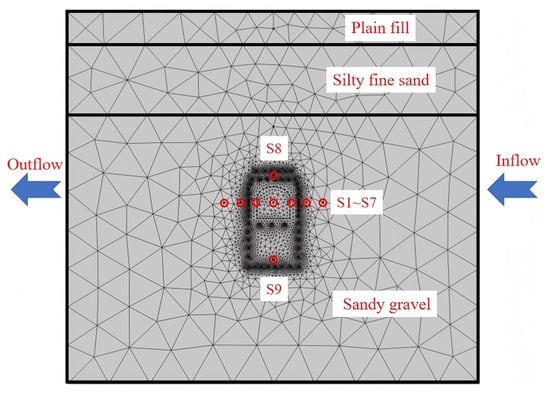

The soil was meticulously filled and compacted in layers, adhering to the prescribed density specifications. The insulation board was pasted on the surface of the box to isolate the heat transfer inside and outside the box, ensuring the cooling effect inside the box and the stability of the model boundary conditions. Prior to the initiation of the experiment, the water level in the chamber was meticulously regulated to the level of the filled soil, thereby ensuring optimal saturation conditions for a duration of eight hours. It is imperative to acknowledge the pivotal role that the surrounding environment plays in influencing heat transfer and seepage within the soil when formulating a test model. The test model can be simplified as a two-dimensional geometric model with dimensions of 0.8 m in length and 0.8 m in height. The seepage direction is from right to left, and the arrangement of the freezing pipes and temperature measurement points is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Layout of the freezing pipes and thermistors (unit: mm).

4.2. Model Verification

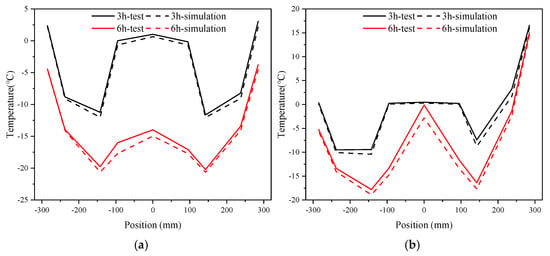

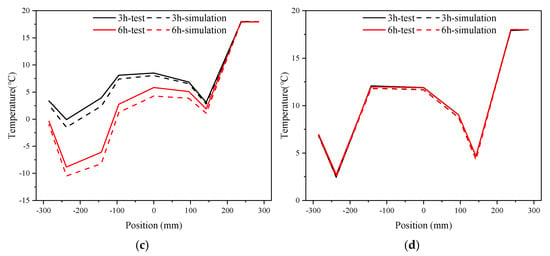

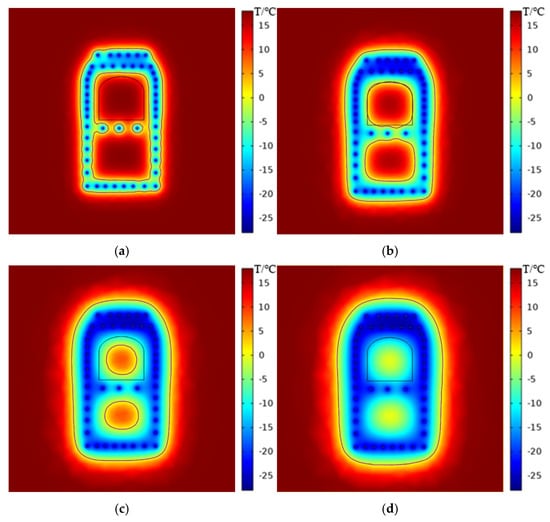

As shown in Figure 6, if there is no seepage, the temperature of the ground is normally distributed with a W shape. The closer to the freezing pipes, the lower the ground temperature, with the inner side of the connecting passage being colder than the outer side. When water seeps through the ground, the temperature is not spread out evenly. In fact, the temperature is higher in the area upstream than in the area downstream. As the temperature gets colder, there is not much change in the temperature upstream, but downstream and in the cross passage, there is a lot of cooling. Seepage carries cold energy to the downstream area, which makes a local frozen wall form. The way water was moving becomes blocked, so it is now moving around the frozen wall. This helps to reduce the negative effects of heat transfer on cooling in this area. In addition, the temperature–time curve of a standard thermistor of the G-axis at different seepage velocities is shown in Figure 7. It is interesting that the results from the simulations and experiments at 76.8 m/d are more similar. This is because large amounts of frozen bodies will not be formed at high seepage velocity. The path that water takes through the soil will not be greatly affected by freezing. Overall, the results from the model are similar to the results from the experiment, which suggests that the model can effectively predict changes in ground temperature. It should be noted that the validation remains primarily temperature-based, rather than stress- or deformation-based.

Figure 6.

Temperature distribution of typical thermistors of G-axis: (a) 0 m/d; (b) 25.6 m/d; (c) 51.2 m/d; (d) 76.8 m/d.

Figure 7.

Temperature–time curve of typical thermistors of G-axis: (a) 0 m/d; (b) 25.6 m/d; (c) 51.2 m/d; (d) 76.8 m/d.

5. Influence of Seepage on Frozen Wall Formation

The middle section of the cross passage was selected for the establishment of the calculation model. The model’s dimensions were 50 m × 45 m, and the cross passage featured a horseshoe-shaped section measuring 4 m × 3.5 m. The positioning of the freeze pipes was determined according to the actual inclination angles, with a diameter of 89 mm. In view of the complex distribution of strata, it was considered essential to implement suitable adjustments in accordance with the prevailing circumstances. The stratigraphic sequence was characterized by a succession of unconsolidated sediments, commencing with a layer of plain fill, succeeded by a silty fine sand layer, and concluding with a sandy gravel layer. The thickness of these layers was recorded as 3.88 m, 8.5 m, and 32.62 m, respectively. The thermophysical parameters of the strata are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Physical parameters of soil layers.

The temperature field and seepage field calculations were performed using the Heat Transfer in Porous Media module and the PDE module in Comsol Multiphysics, respectively. The coefficient form of the partial differential equation (PDE) was utilized for the definition of partial differential equations. The fully coupled solver was adopted to simultaneously update all unknowns at each iteration step, thereby solving the governing equations of the temperature field and the moisture field concurrently. Temperature and flow velocity were designated as the initial field variables, with saturation serving as an intermediate variable to delineate the alterations in hydraulic characteristics and thermophysical parameters with temperature. The geometrical model was divided into 31,271 triangular elements, with local refinement around the areas of the freeze pipe. The coupled equations were solved using the software’s built-in transient solver, and time discretization used the backward differentiation method with a general time step of 1 h. The boundary conditions and mesh division of the calculation model are illustrated in Figure 8. The initial condition for the temperature field was set as the initial formation temperature:

Figure 8.

Boundary condition and grid division of calculation model.

The initial condition for the seepage field was set to zero initial pressure:

It is imperative to acknowledge the heat loss between the refrigerant and the freezing pipes when determining the temperature boundary condition at the wall of the freezing pipe. The output brine temperature was set as the boundary temperature:

The direction of seepage direction is from right to left. The left and right seepage boundaries are defined in terms of pore water pressure, while the left and right temperature boundaries use the temperatures of the outflow and inflow of groundwater, respectively:

The remaining positions are defined as adiabatic temperature boundaries and no-flow seepage boundaries:

5.1. Formation Process of Frozen Wall

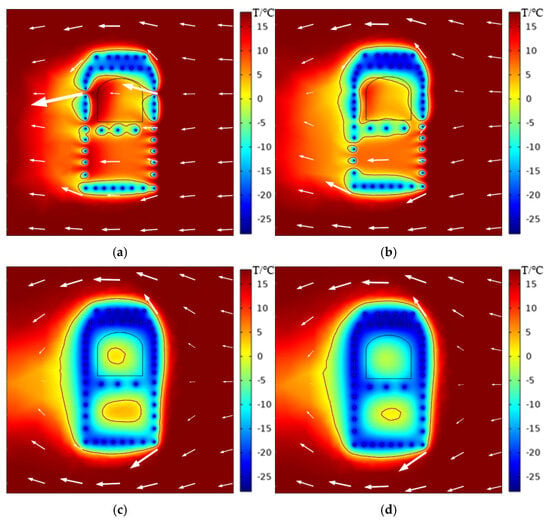

The temperature field for the cross passage under conditions of no seepage is illustrated in Figure 9. The freezing temperature of sandy gravel has been determined to be −0.1 °C. In the context of the subway cross passage, closure was defined as the formation of a frozen wall with a sealed contour, the purpose of which is to resist water and soil pressure [28]. The −0.1 °C isotherm for sandy gravel was regarded as the contour of the frozen wall. As the duration of the freezing period increased, a gradual decrease in ground temperature was observed in the freeze pipe area. Concurrently, there was continuous expansion of the frozen wall. The presence of a double row of freeze pipes at the arch crown has been demonstrated to accelerate the development of frozen soil columns, with this phenomenon subsequently extending to cross passage sidewalls. The development of frozen soil columns was retarded at the pump room floor and sidewalls due to the increased spacing of freeze pipes. Following a period of ten days during which temperatures were below zero, the frozen wall of the cross passage had achieved closure, thus forming a closed frozen wall. In the aftermath of a 20-day period characterized by sub-zero temperatures, the frozen wall underwent a further expansion in both the radial and tangential directions, ultimately reaching the excavation profile of the cross passage. In the aftermath of a 37-day period characterized by sub-zero temperatures, the frozen wall underwent expansion, consequently leading to a further diminution in area of the internal core. Subsequent to a period of 50 days, the internal core of the cross passage became invisible, thereby indicating that the soil in this area had undergone complete freezing.

Figure 9.

The expansion of the frozen wall of cross passage at a velocity of 0 m/d: (a) 10 d; (b) 20 d; (c) 37 d; (d) 50 d.

The freezing temperature field and seepage field under a flow velocity of 5 m/d are demonstrated in Figure 10. As the freezing time progresses, the temperature field becomes asymmetric. Affected by seepage, the thicknesses of the frozen soil columns on the upstream and downstream sides facing the flow were both smaller than those on the leeward sides. In the aftermath of a ten-day period characterized by sub-zero temperatures, the formation of frozen walls became evident at the cross passage arch crown and the pump room floor. However, the closure of the sidewall areas was not yet observed. Subsequent to a period of 20 days, a decline in ground temperature was observed, resulting in the formation of a continuous frozen wall on the downstream sidewall of the cross passage. At this stage, the expansion of the frozen wall was slower due to the influence of seepage. Following a 37-day period, both the cross passage and the pump room’s frozen walls were closed, and it was found that the area of the internal core in the cross passage was smaller than under static water conditions. This phenomenon can be attributed to the fact that, subsequent to the closure of the frozen wall, a minimal quantity of unfrozen water continued to form seepage channels. It has been demonstrated that low-speed seepage promotes the uniform distribution of cooling from the freeze pipes. This, in turn, accelerates the expansion of the frozen wall. Following a period of 50 days characterized by sub-zero temperatures, the cross passage frozen wall had undergone complete freezing, while the pump room frozen wall had undergone rapid expansion, albeit with the presence of a residual core. It is imperative to acknowledge that the white arrows in the diagram signify the velocity and direction of seepage. Local frozen soil bodies have been observed to induce significant increases in the flow velocity of groundwater, thereby causing it to flow around and through adjacent seepage channels. The continuous development of frozen soil columns forms a continuous frozen wall, thereby obstructing seepage channels. This phenomenon can be explained by the rapid shrinkage of the internal core area after the closure of the cross passage and pump room [20].

Figure 10.

The expansion of the frozen wall of the cross passage at a velocity of 5 m/d: (a) 10 d; (b) 20 d; (c) 37 d; (d) 50 d.

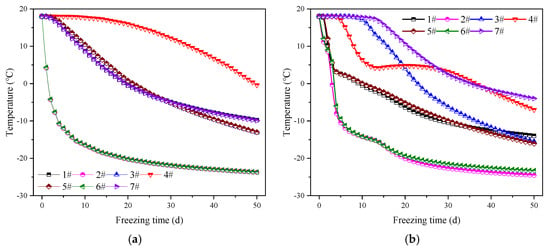

5.2. Development and Distribution of Ground Temperature

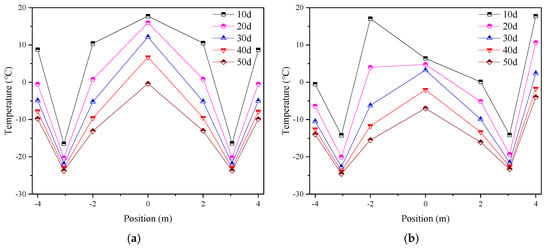

The development and distribution of temperatures at typical measurement points under flow velocities of 0 m/d and 5 m/d are demonstrated in Figure 11 and Figure 12, respectively. In the context of static water conditions, the temperature development at measurement points exhibiting symmetry is found to be largely synchronous, a phenomenon that aligns with the symmetrical distribution of the temperature field. As demonstrated in the relevant literature, the magnitude of the distance between the measurement point and the freeze pipe has been shown to have a direct correlation with the temperature gradient and the rate of temperature decline during the initial freezing stage.

Figure 11.

Temperature variation at typical measuring points: (a) 0 m/d; (b) 5 m/d.

Figure 12.

Temperature distribution of typical measuring points: (a) 0 m/d; (b) 5 m/d.

It is evident that the magnitude of the distance is directly proportional to the intensity of the temperature gradient and the rate of temperature decline. It was determined that the S2 and S6 models, which were located between two freeze pipes, cooled down at the fastest rate. In contrast, the S4 model, situated at the center of the cross passage, exhibited the slowest cooling rate. It was established that, since the distances from S1 and S7 to the sidewall freeze pipes were slightly smaller than those of S3 and S5, the former cooled down faster in the initial freezing stage. Following the closure of the frozen wall, influenced by the superimposed effect of multiple pipes, there was a gradual decline in temperature at the inner points S3 and S5 in comparison to S1 and S7.

It has been demonstrated that, at a velocity of 5 m/d, the temperature development at symmetric measurement points becomes non-synchronous. S2 and S6, located between two freeze pipes, exhibited substantial temperature gradients and were less impacted by seepage, consequently undergoing the fastest cooling process. It is evident that S1 and S5 were located on the leeward sides of the downstream and upstream sidewalls, respectively. It has been demonstrated that seepage carried some cold energy to these areas, thereby enhancing the cooling effect to a certain degree; consequently, the cooling rate was considerably greater than that observed at S3 and S7, which were located on the flow-facing sides of the downstream and upstream sidewalls, respectively. In the initial phase of freezing, S4 experienced a rapid decline in temperature, attributable to the loss of cold energy through seepage. Following the formation of a frozen wall on the upstream sidewall, which obstructed the seepage path, the cooling rate was observed to decelerate. In the subsequent freezing stage, influenced once more by the superimposed effect of multiple pipes, a further accelerated cooling phase ensued. It can be deduced from the data, which shows a period of 50 days with temperatures below 0 °C, that the internal area had undergone complete freezing.

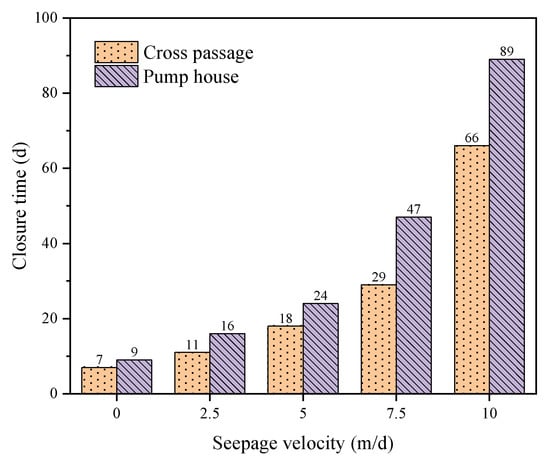

5.3. Influence of Seepage on Closure Time

The spacing of freeze pipes in the sidewalls of the cross passage and the pump room was different, with maximum spacings of 0.9 m and 1.2 m, respectively, leading to asynchronous closure times for the cross passage and pump room. The closure times for the cross passage and pump room under different flow velocities are shown in Figure 13. In conditions of static water, the variation in closure time between the cross passage and the pump room was minimal. It was demonstrated that an increase in flow velocity was accompanied by a significant delay in closure times for both the cross passage and the pump room. It was demonstrated that there was a significant increase in the difference between closure times in the cross passage and the pump room as the flow velocity increased. This finding suggests that increasing the spacing between freeze pipes has a substantial effect on prolonging the closure time of the frozen wall under conditions of high-speed seepage. It is noteworthy that when the velocity was set at 12.5 m/d, the cross passage did not close even after 100 days of freezing. In order to ensure project safety and economy, the implementation of either geological grouting or precipitation is used to reduce groundwater flow velocity. Consequently, closure times for flow velocities greater than 12.5 m/d under this pipe layout scheme are not discussed in this paper.

Figure 13.

Relationship between the closure time and velocity.

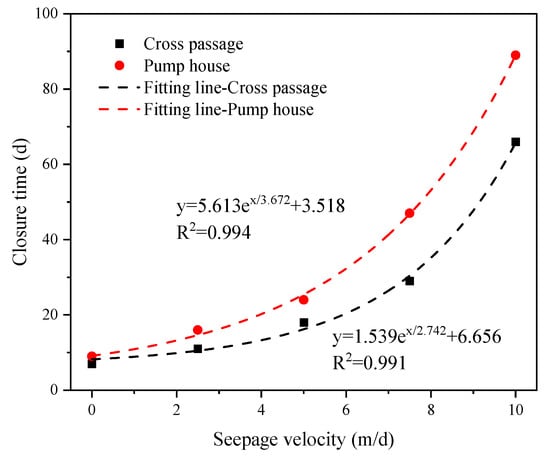

The closure times of the cross passage and pump room were modeled using an exponential function, with the function being fitted to data relating to the closure times under different groundwater velocities. The outcomes of the fitting process are presented in Figure 14. When the velocity does not exceed 10 m/d, the exponential function can reasonably predict the closure times of the frozen walls for the cross passage and pump room under different flow velocities, providing a reference for the design and construction of similar projects. It is important to note that the suitability of expressions is conditional on the specific freeze-pipe layout, soil properties, boundary conditions, and the adopted closure criterion. The proposed exponential relationships are intended as engineering reference tools, not universal predictive laws.

Figure 14.

Prediction for the closure time of the frozen wall at different groundwater velocities.

6. Conclusions

The primary factor influencing the formation process of frozen walls is the continuous replenishment of heat in frozen areas by groundwater. The distribution and development of the ground temperature under seepage conditions differ significantly from those under static water conditions. It is important to note that the mean temperature and effective thickness of the frozen wall may not meet expectations. This could have a significant impact on the safe progression of freezing engineering. The functional relationship between unfrozen water content and temperature in saturated sandy gravel was obtained by means of FDR. The establishment of a coupled hydrothermal mathematical model in saturated ground was informed by the principles of heat transfer and seepage theory in porous media. The model was verified using model test results from a freezing project of a subway cross passage.

A systematic study was conducted on the influence of groundwater flow on the formation of frozen walls, with the study being based on a freezing project. The spacing of freeze pipes in the lateral walls of the cross passage and pump room was not uniform, which resulted in asynchronous closure times. In conditions of static water, the closure times for the cross passage and pump room were seven and nine days, respectively. As the groundwater velocity increased, the closure times for both the cross passage and pump room were significantly delayed, and the difference between their closure times also increased. In instances where the groundwater velocity does not exceed 10 m/d, it can be reasonably predicted that an exponential function will provide a reliable prediction of the closure times of the frozen walls for the cross passage and pump room, given the variation in flow velocities.

The upstream sidewall has been identified as the primary weak link in the process of frozen wall expansion in seepage ground. It is recommended that the monitoring of the temperature field in this area be strengthened. In the event that the development of the frozen wall does not meet expectations, measures such as the addition of supplementary freeze pipes upstream or grouting with the objective of reducing ground permeability should be taken promptly.

Emphatically, a fully coupled thermo-hydro-mechanical 3D model is indeed at the forefront and represents the future direction of research in the field of artificial ground freezing. It is not only a technical advancement but also an essential pathway toward achieving engineering safety, economic efficiency, and accurate predictions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.L. and J.D.; Methodology, X.L., J.D., Z.S. and L.W.; Software, H.C.; Validation, Y.X.; Formal analysis, J.D.; Investigation, X.L., J.D. and F.Z.; Resources, Z.S. and L.W.; Data curation, H.C. and L.W.; Writing—original draft, X.L., H.C., Z.S., L.W. and F.Z.; Writing—review & editing, X.L., J.D., X.Z. and Y.X.; Visualization, X.L.; Supervision, X.Z. and Y.X.; Project administration, X.Z.; Funding acquisition, X.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The financial support for this research was provided by the Chongqing Natural Science Foundation (CSTB2024NSCQ-MSX1010), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2024M753858), and the Chongqing Municipal Education Commission Science and Technology Research Project (KJQN202400769).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study did not require ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Fuping Zheng was employed by the company Chongqing Ludi Construction Company. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Zhou, X.; Jiang, G.; Li, F.; Gao, W.; Han, Y.; Wu, T.; Ma, W. Comprehensive Review of Artificial Ground Freezing Applications to Urban Tunnel and Underground Space Engineering in China in the Last 20 Years. J. Cold Reg. Eng. 2022, 36, 4022002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, K.Q.; Li, D.Q.; Tang, X.S.; Gu, S.X. Coupled Thermal–Hydraulic Modeling of Artificial Ground Freezing with Uncertainties in Pipe Inclination and Thermal Conductivity. Acta Geotech. 2021, 17, 257–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Chen, J.; Sugimoto, M.; Ge, H. Numerical Simulation Model of Artificial Ground Freezing for Tunneling Under Seepage Flow Conditions. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2019, 92, 103035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Shen, Y.P.; Zhang, Z.C.; Liu, Z.J.; Wang, B.L.; Tang, T.X.; Liu, C. Field Measurement and Numerical Investigation of Artificial Ground Freezing for the Construction of a Subway Cross Passage Under Groundwater Flow. Transp. Geotech. 2022, 37, 100869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Ji, Z.; Zhang, P.; Qi, J. Model Test and Numerical Simulation on the Development of Artificially Freezing Wall in Sandy Layers Considering Water Seepage. Transp. Geotech. 2019, 21, 100293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, E.; Sres, A.; Anagnostou, G. Large-Scale Laboratory Tests on Artificial Ground Freezing Under Seepage-Flow Conditions. Géotechnique 2012, 62, 227–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.B.; Li, S.; Liang, Y.; Yao, Z.S.; Cheng, H. Model Test and Numerical Simulation of Frost Heave During Twin-Tunnel Construction Using Artificial Ground-Freezing Technique. Comput. Geotech. 2019, 115, 103155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.D.; Fang, T.; Chen, J.; Ren, H.; Guo, W. A Large-Scale Physical Model Test On Frozen Status in Freeze-Sealing Pipe Roof Method for Tunnel Construction. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2018, 72, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Nowamoo, H.; Shen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Han, Y.; An, Y. Heat Transfer Analysis in Artificial Ground Freezing for Subway Cross Passage Under Seepage Flow. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2023, 133, 104943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Lee, S.; Lee, H.; Park, S.; Choi, H.; Won, J. Assessing the Reuse of Liquid Nitrogen in Artificial Ground Freezing through Field Experiments. Acta Geotech. 2024, 19, 6825–6842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, G.; Corbo, A.; Cavuoto, F.; Autuori, S. Artificial Ground Freezing to Excavate a Tunnel in Sandy Soil. Measurements and Back Analysis. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2015, 50, 226–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Z.X.; Cui, Z.D.; Yang, P.; Zhang, T. In Situ Monitoring of Temperature and Deformation Fields of a Tunnel Cross Passage in Changzhou Metro Constructed by AGF. Arab. J. Geosci. 2020, 13, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Ye, G.L.; Li, Y.H.; Xia, X.H.; Wang, J.H. In Situ Monitoring of Frost Heave Pressure During Cross Passage Construction Using Ground-Freezing Method. Can. Geotech. J. 2016, 53, 530–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Son, Y.; Kim, J.; Won, D.; Choi, H. Thermal and Mechanical Impact of Artificial Ground-Freezing on Deep Excavation Stability in Nakdong River Deltaic Deposits. Eng. Geol. 2024, 343, 107796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saberi, M.; Meschke, G. Numerical Investigation of Artificial Ground Freezing–Thawing Processes in Tunnel Construction. Comput. Geotech. 2024, 173, 106477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Guo, W.; Sun, Y.; Li, Q. Hydro-Thermal-Solid Modeling of Artificial Ground Freezing through Cold Gas Convection. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2024, 198, 108893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitel, M.; Rouabhi, A.; Tijani, M.; Guérin, F. Modeling Heat and Mass Transfer During Ground Freezing Subjected to High Seepage Velocities. Comput. Geotech. 2016, 73, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, E.; Papakonstantinou, S.; Anagnostou, G. Numerical Interpretation of Temperature Distributions From Three Ground Freezing Applications in Urban Tunnelling. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2012, 28, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zueter, A.; Nie-Rouquette, A.; Alzoubi, M.A.; Sasmito, A.P. Thermal and Hydraulic Analysis of Selective Artificial Ground Freezing Using Air Insulation: Experiment and Modeling. Comput. Geotech. 2020, 120, 103416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzoubi, M.A.; Madiseh, A.; Hassani, F.P.; Sasmito, A.P. Heat Transfer Analysis in Artificial Ground Freezing Under High Seepage: Validation and Heatlines Visualization. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2019, 139, 232–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tounsi, H.; Rouabhi, A.; Jahangir, E. Thermo-Hydro-Mechanical Modeling of Artificial Ground Freezing Taking into Account the Salinity of the Saturating Fluid. Comput. Geotech. 2020, 119, 103382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tounsi, H.; Rouabhi, A.; Tijani, M.; Guérin, F. Thermo-Hydro-Mechanical Modeling of Artificial Ground Freezing: Application in Mining Engineering. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2019, 52, 3889–3907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marwan, A.; Zhou, M.; Zaki Abdelrehim, M.; Meschke, G. Optimization of Artificial Ground Freezing in Tunneling in the Presence of Seepage Flow. Comput. Geotech. 2016, 75, 112–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Teng, J.; He, Z.; Sheng, D. Importance of Vapor Flow in Unsaturated Freezing Soil: A Numerical Study. Cold Reg. Sci. Tech. 2016, 126, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.Z.; Li, D.Q. Numerical Analysis of Coupled Water, Heat and Stress in Saturated Freezing Soil. Cold Reg. Sci. Tech. 2012, 72, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zueter, A.F.; Zolfagharroshan, M.; Bahrani, N.; Sasmito, A.P. Artificial Ground Freezing of Underground Mines in Cold Regions Using Thermosyphons with Air Insulation. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2024, 34, 643–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoreishian Amiri, S.A.; Grimstad, G.; Kadivar, M. An Elastic-Viscoplastic Model for Saturated Frozen Soils. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. 2022, 26, 2537–2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Wu, W.; Zhang, C.; Ma, S.; Li, Y. Monitoring and Evaluation of Artificial Ground Freezing in Metro Tunnel Construction—A Case Study. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2019, 23, 2359–2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Guo, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ke, L.; Liu, G.; Chen, C. Study on the Influence of Water Flow on Temperature Around Freeze Pipes and its Distribution Optimization During Artificial Ground Freezing. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2018, 135, 435–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzoubi, M.A.; Xu, M.H.; Hassani, F.P.; Poncet, S.; Sasmito, A.P. Artificial Ground Freezing: A Review of Thermal and Hydraulic Aspects. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2020, 104, 103534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Nowamooz, H. Effect of Rising Damp in Unstabilized Rammed Earth (Ure) Walls. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 307, 124989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Lai, Y.; Zhang, M.; Pei, W.; Zhang, C.; Yu, F. Centrifuge and Numerical Modeling of the Frost Heave Mechanism of a Cold-Region Canal. Acta Geotech. 2019, 14, 1113–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.