Abstract

Children’s skin is highly sensitive and prone to irritation, allergies, and infections, requiring special consideration in textile selection. Although clothing serves as a protective barrier, it can also pose a risk when dyed with toxic chemical colourants. This study explores the potential of multifunctional natural dyes as safer alternatives for children’s clothing, particularly for those with dermatological conditions. Cotton knitted fabrics were dyed through exhaustion with extracts of madder root (Rubia tinctorum L.), pomegranate peel (Ppe, Punica granatum L.), oxidised logwood (Logox, Haematoxylum campechianum L.), and tannin from quebracho (Schinopsis lorentzii Griseb.), both individually and in various combinations with or without potassium aluminium sulphate dodecahydrate (alum). The combination of madder and Ppe demonstrated the most promising multifunctional performance, being classified as a weak disinfectant against S. aureus (3.7 log reduction) and showing the highest antioxidant activity (92.6 ± 2.56% 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid (ABTS) radical reduction), while maintaining excellent results after washing. Moreover, these natural formulations expanded the achievable colour palette from each dye while maintaining moderate wash fastness. The results highlight the relevance of these findings to textile and fashion designers, offering sustainable tools for creating health-conscious, visually appealing garments. This research reinforces the potential of natural dyes and biomordants in developing functional textiles that support children’s wellbeing and environmental responsibility.

1. Introduction

Sustainability has become increasingly central to the fashion industry, driven by organisational commitments and rising consumer awareness of environmental and health impacts [1,2]. Along with ecological considerations, issues such as hygiene, safety, and protection have become increasingly relevant in the children’s clothing sector [3].

Childhood represents a particularly vulnerable stage of life [4]. Early exposure to hazardous substances or unsuitable environmental stimuli can have long-lasting health consequences. Children’s skin is highly sensitive and among the most susceptible organs to infections [5]. This susceptibility is especially pronounced during the first five years of life, when the immune system is still developing. Therefore, it is less capable of defending against harmful agents, an issue of even greater concern for children with naturally sensitive skin [6].

Given these sensitivities, the selection of textile materials is crucial for ensuring comfort and safety. Natural fibres, especially cotton, are widely preferred in children’s clothing due to their softness, breathability, moisture absorption, and hypoallergenic properties, which help minimise irritation and promote healthy skin function [7,8]. Cotton’s moisture absorption and air permeability create a comfortable microclimate between the fabric and the skin, making it especially suitable for infant and young child clothing [9,10].

In contrast, synthetic textile materials often contain considerable amounts of petrochemical-based compounds, which can present risks to human health and the environment [11]. Their production and finishing processes typically involve a variety of chemical additives that can cause skin irritation, allergic reactions, or other adverse effects, particularly when in prolonged contact with sensitive skin [9]. Moreover, the use of toxic chemicals in dyeing processes further exacerbates these concerns, as such substances have been associated with respiratory and dermatological conditions frequently observed in children exposed to conventionally dyed textiles through daily wear [12,13].

At the same time, colour remains a fundamental element in fashion, stimulating and attracting consumers through visual perception [14]. Beyond its cultural and emotional dimensions, colour assumes particular significance in children’s clothing, where it can actively contribute to cognitive, emotional, and behavioural development [15]. The consumption of children’s clothing continues to rise, with new garments purchased approximately every four to five months, yet consumer awareness regarding harmful dyeing chemicals remains limited [16]. Nevertheless, studies show that parents respond positively to clothing explicitly associated with reduced toxicity and improved wellbeing for children [16,17].

In this context, natural dyes have gained attention as a sustainable and healthier alternative to synthetic colourants [18]. Their biodegradability and non-toxicity make them attractive for children’s textiles [19,20]. However, their broader application faces considerable challenges, comprising limited colour fastness, a restricted chromatic spectrum, and complex dyeing processes difficult to implement in the industry [21]. Furthermore, the high crystallinity index of cotton and the absence of functional groups for chemical interactions result in a lower affinity for antimicrobial agents. This reduced affinity also contributes to fixation issues with natural dyes and leads to poor colour fastness [22,23]. To tackle these challenges, the use of biomordants (many of which possess intrinsic chromatic or functional properties [24,25]) has been explored as an environmentally friendly alternative to conventional metal-based mordants [26,27]. Certain plant-derived natural dyes, in addition to providing colour when applied individually, also exhibit fixative capabilities due to their high content of tannins and other polyphenolic compounds, enabling them to function as biomordants [21,27,28]. Moreover, when used in combination with other dyes, they can act as colour modifiers, influencing hue and saturation [26].

At the same time, the functional properties of children’s clothing are increasingly important [18]. Beyond aesthetics, garments are expected to contribute to health and wellbeing. Antimicrobial and antioxidant treatments, in particular, are important in reducing the risk of infections and improving hygiene in daily wear [7,29]. As children’s skin is particularly sensitive and prone to irritation and infection [30], fabrics that incorporate natural dyes or biomordants with inherent antimicrobial and antioxidant activity can provide a dual benefit, promoting sustainability and improving protective and health-related functions [31].

Antibacterial agents based on phenols, quaternary ammonium salts, and organosilicones are effective at inhibiting bacterial growth. However, these agents are toxic, harmful to the skin, non-eco-friendly, and have an adverse impact on the environment. Therefore, it can be concluded that every antibacterial agent has their own merits and demerits. Hence, the use of natural dyes can be considered one of the most efficient ways to enhance antibacterial activity while maintaining protection and sustainability [32,33]. However, in order to increase the applicability of natural dyes, mordants are used to improve their adhesion to the fabric by forming coordinating complexes and, in addition, enhancing antibacterial resistance [34]. Utilisation of metal mordants, such as silver, zinc, and TiO2, is highly effective. Yet, the mordanting process is hazardous to human beings, particularly for children, as their skin is highly sensitive. Hence, biomordants appear to be a promising solution to overcome these limitations [35].

Beyond antimicrobial protection, functional textiles can also benefit from antioxidant activity. The incorporation of antioxidant molecules may neutralise free radicals and limiting oxidative stress, thereby reducing the inflammatory process [29,36,37]. Besides protecting against oxidative damage, such compounds also enhance the mechanical durability and colour fastness of textile materials [38].

Biofunctional textiles based on polyphenols, such as those functionalised with madder, pomegranate, Logox, and tannin extracts, have been reported to exhibit superior antioxidant and antimicrobial properties [39,40,41]. These properties are mainly attributed to the presence of various polyphenols and other phenolic compounds (e.g., tannins, flavonoids, alizarin, gallic acid, ellagic acid, quercetin and anthraquinones) within the chemical composition of the natural dyes and biomordants under study [41]. Madder is particularly promising in this context, as its high concentration of phenolic groups and flavonoids enhances antioxidant activity [22]. Indeed, wool yarns dyed with madder demonstrated strong antioxidant efficacy, achieving a 62.7% reduction in 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radicals [42]. This study investigates the potential of natural dyes with antibacterial and antioxidant properties as a safer alternative for children’s clothing, especially for those with sensitive or dermatological conditions. In the first phase, cotton knitted fabrics were dyed with natural dyes extracted from madder roots (Rubia tinctorum L.), pomegranate peels (Ppe, Punica granatum L.), and oxidised logwood bark (Logox, Haematoxylum campechianum L.), as well as tannin extracted from quebracho (Schinopsis lorentzii Griseb.), both individually and in combination with potassium aluminium sulphate dodecahydrate (alum, AlK(SO4)2·12H2O) as a metallic mordant. These natural materials were selected for their complementary chromatic properties and distinct chemical profiles, allowing a comprehensive assessment of dyeing performance and biofunctional behaviour. Madder is a historically significant anthraquinone dye known for its chromatic yield and its documented medicinal properties [18,22]. Ppe, a sustainable agro-industrial by-product, is rich in tannins and polyphenols, providing dual functionality as a dye and biomordant with antimicrobial and antioxidant efficacy [27,43]. Logox introduces phenolic haematoxylin derivatives that produce deep violet-blue hues [44], expanding the chromatic range under study. Table 1 displays the antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of textiles dyed with these natural dyes. Tannin derived from quebracho was also included for its colour yield and for its high content of condensed tannins, making it a promising natural biomordant capable of improving functional properties [27].

Table 1.

Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of biofunctional textiles dyed with natural dyes.

Based on the promising chromatic results obtained with madder, a second experimental phase was developed in which madder served as the primary dye, combined with Ppe and tannin acting as biomordants and Logox as colour modifier. Finally, biological assays were performed on dyed samples to evaluate their antibacterial and antioxidant efficacy, providing an integrated understanding of both their aesthetic and health-related potential.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Table 2 presents a comprehensive overview of the materials applied in the experimental work, organised according to material type, description and supplier.

Table 2.

List of materials used in experimental methods.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Dyeing and Mordanting Processes

Dyeing experiments were performed for 60 min at 80 °C using IBELUS IL-720 equipment (Pregitzer & Ca., Lda, Guimarães, Portugal), following the exhaust dyeing method with a bath ratio of 1:20. Prior to dyeing, the cotton knitted samples were washed with ECE (1 g/L) to remove surface impurities and then pre-moistened to ensure uniform dye penetration. After dyeing, all samples were rinsed in distilled water and dried at 40 °C.

A 4% dye concentration (per weight of fibre, WOF) was applied to madder and Logox due to their high pigment content. In contrast, 15% WOF was used for Ppe and alum, reflecting the higher quantities required to achieve effective mordanting and dye fixation. Tannin was applied at 8% WOF due to its high content of active binding compounds and strong affinity for cellulose fibres. The dyeing conditions and percentages of products used were adapted from traditional artisanal dyeing practices and improved for application in a controlled experimental context [50].

In the first phase of the study, samples were dyed with natural dyes either individually or in combination with alum. Based on the promising colour results achieved with madder, a second experimental phase was designed in which madder was used as the primary dye, while the other natural extracts acted as biomordants and/or colour modifiers. In this stage, madder was combined separately with each biomordant through a meta-mordanting process. Subsequently, alum was introduced to all these combinations to evaluate its influence on colour development and fixation. For tannin and Logox, alum was applied simultaneously in a pre-mordanting process, whereas for Ppe, the sample was first pre-mordanted with alum and then dyed with the madder-Ppe combination using the meta-mordanting method. Previous colour studies determined the choice of mordanting techniques for each process, with the methods that yielded the best colour depth and uniformity chosen for each combination. A total of fourteen different dye combinations were analysed. In order to guarantee the dependability and consistency of the findings, three duplicates were performed for each dyeing condition.

2.2.2. Wash Fastness Tests and Colour Evaluations

Wash fastness assessments were performed using the Washtec-P equipment (Roaches, Birstall, West Yorkshire, UK) in accordance with NP EN ISO 105-C06:2010 standard, assay number A1S [51]. Each test was conducted in a 150 mL bath containing ECE (4 g/L) and 10 stainless-steel balls to simulate mechanical agitation. The dyed samples, sewn to a multifibre adjacent fabric, were washed at 40 °C for 30 min, then rinsed and dried at 40 °C prior to colour measurement.

The colour of the dyed samples was analysed instrumentally using a Datacolor International SF600 Plus—CT spectrophotometer (Datacolor, Lucerne, Switzerland), integrated with Datacolor TOOLS software (24.1.1 version). The analysis was performed under standardised conditions, using the D65 illuminant (representing average daylight conditions) and a 10° standard observer to simulate human colour perception. Three measurements were taken from different areas of each fabric sample (before and after washing) to account for potential variations, and the average value was used for analysis. Results were accepted only when the colour difference (ΔE*) between individual readings was less than 1 [52].

Colour parameters were determined according to the International Commission on Illumination (CIE) Lab and LCh colour systems. The ΔE* was calculated using Equation (1):

where, Δ symbol means “difference in”, L* represents lightness (0 = black, 100 = white), a* corresponds to the red–green axis (positive = red, negative = green), and b* to the yellow–blue axis (positive = yellow, negative = blue). In the LCh system, C* indicates chroma (colour saturation) and h denotes hue (colour tone) [53].

ΔE*ab = [(ΔL*)2 + (Δa*)2 + (Δb*)2]1/2,

After washing, the evaluation focused exclusively on colour change, excluding staining on the adjacent multifibre fabric. Colour variations were quantified using the obtained CIE Lab data to provide objective information on chromatic alterations. To complement the analysis, ΔE* values were subsequently interpreted according to ISO 105-A05:1993 standard [54], which defines the grey scale rating for assessing colour change. In this approach, the spectrophotometric values are correlated with the visual grey-scale grades, where 1 indicates severe colour change and 5 denotes excellent resistance.

All samples were photographed using a Canon EOS 700D camera (Canon, Tokyo, Japan) inside a Foldio 3 lightbox (Orangemonkie, San Diego, CA, USA), under consistent lighting, brightness, and focus settings to ensure uniform image quality and comparability across all samples.

2.2.3. Antibacterial Assay

Antibacterial assays were performed through the adaptation of the American Association of Textile Chemists and Colorists (AATCC) TM-100 standard, as reported in [55,56,57]. The pre-inoculum of gram-positive bacterium S. aureus American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) 6538 were prepared using TSB, and the pre-inocula were incubated at 37 °C and 120 rpm for 12 h. Afterwards, the inoculum was centrifuged at 18 °C for 10 min at 3134× g, and resuspended in PBS buffer. S. aureus concentration was adjusted to 1 × 107 colony-forming units (CFU)/mL. Then, the square textile of 4 cm2 were inoculated with 50 μL and incubated at room temperature (approximately 21 °C) for 1 h. Subsequently, the samples were immersed in a 5 mL PBS solution and vortexed for over than 60 s. Afterwards, the obtained suspensions were subjected to serial dilutions and plated on Petri dishes containing tryptic soy agar (TSA). The Petri dishes were incubated at 37 °C for 16 h. The CFUs were counted, their concentration estimated, and by using Equation (2), the logarithmic reduction (log) was calculated. The antibacterial properties (qualitatively) were categorised using the criteria given by Vieira et al. [57].

where, Log (control) is the inoculum concentration of the respective microorganism, and Log (exposed) is the concentration of the microorganism in fabrics after 1 h of incubation.

2.2.4. In Vitro Evaluation of Antioxidant Activity Assay

The antioxidant activity of the dyed knitted fabric was determined using a modified colourimetric ABTS assay [58], optimised to minimise colour interference from the dyed textile. To prepare the ABTS+• radical cation solution, 7 mM ABTS and 2.45 mM potassium persulphate (K2S2O8) were dissolved in ultrapure water (0.055 µS/cm, 25 °C). The solution was kept in the dark at room temperature for 16 h. After incubation, the ABTS stock solution was diluted with 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) until the absorbance reached 0.700 ± 0.025 at 740 nm. For the assay, 2 mL of the ABTS solution was added to 50 ± 1 mg of the dyed knitted fabric samples. These samples were incubated in the absence of light at room temperature for 30 min. After the completion of the colourimetric reaction, the absorbance was measured at 734 nm using an EZ Read Microplate Reader (Biochrom, Cambridge, UK). The percentage of ABTS+• radical inhibition was determined according to Equation (3). All assays were performed in triplicate, and ascorbic acid (1% (w/v)) was used as the positive control.

where, AbsorbanceABTS+• is the absorbance the blank solution, which contains only the ABTS radical and the solvent, and Absorbancesamples is the absorbance of the reaction mixture containing the ABTS radical and the knitted fabrics.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Colour Measurement and Wash Fastness

In the first part of this study, the natural colouration of the selected dyes was observed, either alone or in combination with alum. As a result, tannin, Logox, Ppe, and madder, when used without additional dyes or auxiliary products, produced dark beige, brown, yellowish-beige and orange tones, respectively (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Knitted fabrics dyed with tannin, Logox, Ppe, and madder extracts, as well as their combinations with alum, before and after washing.

The results also showed that the addition of alum considerably influenced the colour appearance and wash fastness of the dyed samples, as depicted in Table 4.

Table 4.

CIE Lab colour differences of samples dyed with tannin, Logox, Ppe, and madder extracts, as well as their combinations with alum, before and after washing.

For tannin-based samples, the addition of alum resulted in a slightly lighter tone (higher L*) and a mild increase in saturation (C*), producing a softer and more luminous beige tone. After washing, the fastness results were poor (grade of 2–3 for tannin and 1 for tannin with alum). This was not necessarily due to a loss of colour, but rather to a colour change to a more saturated and reddish brown induced by the pH shift caused by the slightly alkaline detergent. Washing under alkaline conditions can alter the chemical structure of pH-sensitive natural dyes, leading to changes in colour strength and shade [59]. In contrast, samples dyed with Logox and alum exhibited a different effect. Logox alone showed a brown hue, but when combined with alum, both L* and C* decreased, resulting in a much deeper violet shade. However, this result showed the most considerable loss of colour intensity after washing (ΔE* > 30), indicating that although alum improved initial dye uptake, the bonding between dye and fibre was not sufficiently stable to resist washing.

The addition of alum in the Ppe samples brightened the hue slightly and increased C*. The colour appears paler, being slightly more yellowish (b* = 23.5) and nearly neutral regarding the red-green axis (a* = 0.5). After washing, the colour change was moderate (ΔE* = 3.8), and the wash fastness grade reached 3, making it one of the more stable combinations tested.

Finally, when combined with alum, the madder-dyed fabric showed pronounced darkening and a richer hue, resulting in a deeper, warmer reddish-orange tone compared to the madder-only sample. This effect is evidenced by the marked increase in the a* value, which corresponds to the red–green axis. Despite the improved chromatic richness, washing led to perceptible fading (ΔE* = 11.3) and a poor-to-moderate wash fastness rating (grade 1–2). These results confirm that while alum intensifies the colour of madder, it does not substantially improve its resistance to washing.

Building on these findings, Table 5 presents the results from the second stage of the chromatic analysis.

Table 5.

Knitted fabrics dyed with different combinations of madder and tannin, Logox or Ppe extracts, as well as their combinations with alum in pre-mordanting (pm) processes, before and after washing.

In this phase, madder was used as the primary dye, while the other natural products served as biomordants and/or colour modifiers. The results demonstrate that the chromatic response of madder is strongly influenced by the type of product applied. Quebracho, the source of the tannin used in this study, and Ppe are commonly associated with the development of yellowish-beige hues [60,61]. In contrast, Logox produces cooler violet tones due to its distinct chromophore composition [44]. When combined with madder, which naturally imparts an orange-red colouration, each natural product altered the resulting hues, producing noticeable differences in tone and saturation.

The madder + tannin combination displayed a pale brown, slightly darker (L* = 66.2) than the colour produced by madder alone (L* = 71.8). The madder + Logox sample showed a darker, browner shade (L* = 57.0) with stronger yellow components (b* = 22.3). In contrast, the madder with Ppe combination yielded lighter and brighter tones, tending toward yellow hues, as shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

CIE Lab colour differences of samples dyed with different combinations of madder and tannin, Logox or Ppe extracts, as well as their combinations with alum in pre-mordanting (pm) processes, before and after washing.

These outcomes demonstrate that the intrinsic colour contribution of each auxiliary product can change the final shade, thereby broadening the achievable colour palette without relying on synthetic products. This observation is consistent with previous studies, which emphasise that the type of auxiliary product is determinant of colour yield, fastness, and the overall colourimetric properties of fabrics dyed with natural dyes [26].

Regarding wash fastness, it is generally reported that tannins (also present in considerable amounts in Ppe [21]) can improve the affinity of natural dyes for cellulosic fibres and enhance colour fixation [21,27]. However, in this study, the combination of tannin compounds with madder showed limited resistance to washing. Likewise, fabrics dyed with Logox demonstrated similarly poor fastness results. This reduced performance can be attributed to the inherently low substantivity of cotton towards most natural dyes [22,23].

When alum was introduced into the three previous madder-based combinations, each system responded differently. In the madder + tannin mixture, the colour shifted toward a more saturated red, reflected by an increase in a* from 12.1 to 21.9 and in C* from 19.6 to 27.5, an effect similar to that observed between madder alone and madder + alum. This combination also showed improved wash fastness (ΔE* = 4.4; rating 3) compared to the sample without alum. Conversely, in the madder + Logox combination, alum produced a pronounced hue shift: the h angle changed dramatically from 65 to 324°, accompanied by substantial variations in the remaining colour coordinates. This transformation generated a dark violet tone, indicating a strong interaction between alum, Logox compounds, and madder’s anthraquinones. However, the sample exhibited considerable colour loss after washing (ΔE* = 23.7; rating 1), suggesting poor dye–fibre stability despite higher initial uptake.

In contrast, madder + Ppe achieved the most stable chromatic behaviour upon alum addition and the most balanced performance after washing. The yellowish hues were preserved, and an improvement in wash resistance was observed (ΔE* = 3.3; rating 3–4).

To conclude, despite the various mordanting combinations tested, none of the samples achieved excellent wash fastness. The promising performance was observed in the combination of madder, Ppe, and alum, which attained a rating of 3–4 on the grey scale. Notably, the incorporation of alum with natural auxiliary products resulted in a clear improvement in colour retention compared with natural products alone.

The combination of biomordants/colour modifiers with madder also produced a diverse range of hues and tonal variations, effectively expanding the achievable colour palette without resorting to synthetic dyes and improving chromatic richness using a single primary dye source. Despite these gains, colourfastness remains a critical constraint. The observed colour fading and high ΔE* values following washing highlight a need for further optimisation. Future research should focus on improving the bonding between the natural dye-mordant complex and the fibre substrate to minimise chromatic variability.

3.2. Evaluation of Antibacterial Assay

Children are more prone to infections and skin sensitivities, making the use of textiles with antibacterial properties essential for limiting bacterial growth and supporting hygiene [7].

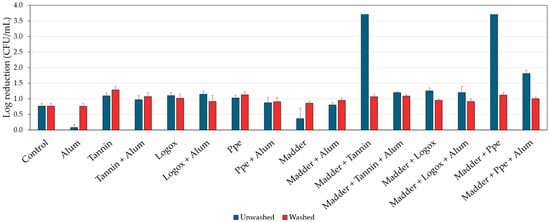

The antibacterial properties of cotton knitted fabrics dyed with natural dyes were evaluated using the gram-positive bacteria S. aureus. The results (Figure 1) showed that the fabrics dyed with alum and madder did not exhibit any antibacterial effect, whereas Ppe alone showed a slight antibacterial effect. The existence of tannin and phenolic compounds, gallic and ellagic acids in Ppe extract might contribute to the antibacterial effect [33,48,62]. As the Ppe consists of a complex mixture of bioactive compounds, the antibacterial activity of Ppe cannot be linked to one single bioactive component, and it can be due to the combined effects of two or more bioactive compounds [41]. The combination of alum with madder or Ppe (madder + alum and Ppe + alum) exhibited an antibacterial slight impact, however, less than that of Ppe alone. The mixture of madder and Ppe exhibited the highest antibacterial activity, and the addition of alum to madder and Ppe has reduced the antibacterial activity of the fabrics. Tannin alone showed little antibacterial effect, which may be due to the presence of functional groups, such as hydroxyl and carboxyl groups, that can form robust complexes with protein chains in some instances [34]. Another factor could be the presence of isomeric phenolic compounds with several structures. The phenolic compounds have hydroxyl groups, which can disrupt the integrity of the cell wall when they interact with the cell wall and membrane of the bacteria [63]. It is also reported that bacterial enzymes and bio-membrane systems can be disrupted by phenolic compounds, thereby affecting bacterial energy metabolism, and that these systems can integrate with bacteria in some respects [34]. The addition of alum to Ppe has slightly reduced the antibacterial effect (1.81 ± 0.11 log reduction). Madder, in combination with tannin or Ppe has achieved a good antibacterial effect (3.70 ± 0.00 log reduction). Hence, the knitted fabrics dyed with both combinations can be classified as a weak disinfectant [57,64]. The antibacterial properties were not retained after washing cycles.

Figure 1.

Antibacterial properties of the dyed knitted fabrics.

To conclude, the antibacterial properties of natural dyes per se do not display relevant antibacterial properties. However, when madder was mixed with tannin or Ppe, it has demonstrated considerable effects. The addition of alum, in any combination, has consistently reduced the antibacterial performance of the knitted fabrics.

3.3. In Vitro Evaluation of Antioxidant Properties

Children’s skin is particularly sensitive and more susceptible to irritation, infection, and inflammatory processes [30]. The presence of antioxidant compounds can mitigate these risks through neutralising free radicals and reducing oxidative stress, thereby minimising inflammation [29,36,37]. Besides protecting the skin from oxidative damage, antioxidant compounds can also enhance the durability and colour fastness of textiles [38]. Therefore, the antioxidant activity of the biofunctional knitted fabric is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

ABTS+• radical inhibition (%) of the dyed knitted fabrics. Ascorbic acid (grey colour) was used as a positive control.

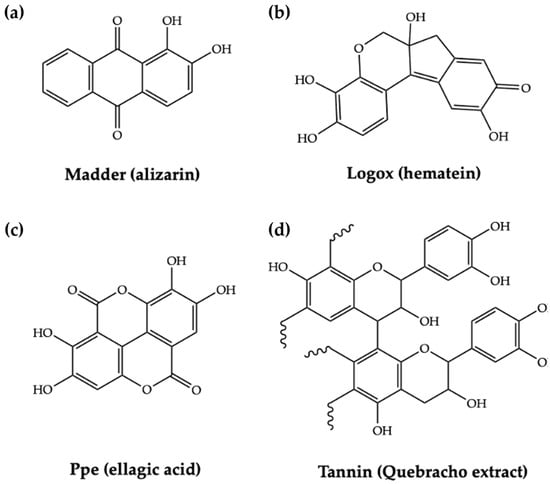

Cotton knits without functionalisation (control sample) exhibit slightly antioxidant activity, with an ABTS radical reduction of 21.1 ± 2.8%. This result confirms that unmodified cotton knitted fabrics have negligible antioxidant properties, as reported in the literature (27.4 ± 1.3%) [58]. Applying biomordants or colour modifiers to the knitted fabrics, namely tannic, Logox, and Ppe, improved antioxidant activity, reaching values above 85%. The antioxidant capacity of extracts depends on polyphenols, chemical composition, and structure, especially the presence of phenolic acids and flavonoids [65]. In the case of Schinopsis lorentzii extract, the tannin obtained possesses both chemical groups [66]. Logox (hematein) contains phenolic groups but no flavonoids [60], and Ppe contains both phenolic and flavonoid groups [43] (Figure 3). For this reason, antioxidant activity increases in the following order: Logox < tannin < Ppe. However, the use of a metallic mordant did not affect these properties (24.4 ± 3.8%), consistent with the literature for cotton fabric modified with alum [49]. When metal mordants were combined with natural products, a slight increase in antioxidant activity was observed in samples treated with tannic acid and Logox. This effect was more pronounced in washed samples, suggesting that exposure of Al3+ salts after washing promoted hydrogen atom transfer and increased antioxidant activity [49]. In contrast, samples treated with Ppe did not exhibit this behaviour, indicating that possibly no complex metal was formed.

Figure 3.

Chemical structures of: (a) madder, the natural dye, and (b) Logox, (c) Ppe, (d) Tannin, the main biomordant molecules and colour modifiers used in this study [29,34,40,60,61].

Furthermore, cotton knitted fabric dyed with madder exhibited a good antioxidant activity (64.2 ± 10.1%), similar to values reported in literature for wool yarns dyed with madder [42]. Although the combination of madder with alum moderately reduced antioxidant activity, auxiliary natural products (tannic, Logox, and Ppe) enhanced it due to their intrinsic phenolic and/or flavonoid groups. Nonetheless, combining the metallic mordant with tannin/Logox (madder + tannin + alum and madder + Logox + alum) reduced the activity of the samples. Antioxidant values of the washed samples increased, indicating that the active components remained bound to the fibre surface, possibly through the formation of a stable dye–metal–fibre complex and the stabilisation of antioxidant compounds [42]. As the structures of the natural dye and the auxiliary natural products used were distinct, no considerable differences were observed between dyed samples treated with Ppe with or without alum, in both unwashed and washed samples. Safapor et al. reported similar results, showing that the washing process reduced antioxidant activity by releasing active compounds. In contrast, metal mordants enhanced retention via stable metal–natural dye chelates with flavonoids [37]. The difference in antioxidant activity between undyed cotton fabrics and those dyed with Ppe rind (94.2%) confirms the effect of this natural extract, with values comparable to those obtained in the present study [35].

To conclude, biofunctional textile dyed with madder combined with Ppe as biomordant and colour modifier, without or with alum (madder + Ppe and madder + Ppe + alum), exhibited excellent antioxidant activity (92.6 ± 2.56% and 94.2 ± 0.86%, respectively), similar to the positive control (ascorbic acid, 95.7 ± 0.43%). Furthermore, the madder + Ppe composite excludes the use of toxic metal mordants, as the intrinsic antioxidant properties of the Ppe ensure sustained activity after washing (89.6 ± 1.44%) [21,67]. Moreover, the madder + Ppe biofunctional knitted fabric exhibits excellent antioxidant and antimicrobial activity against S. aureus (3.70 log reduction), demonstrating its potential for biofunctional and healthcare applications.

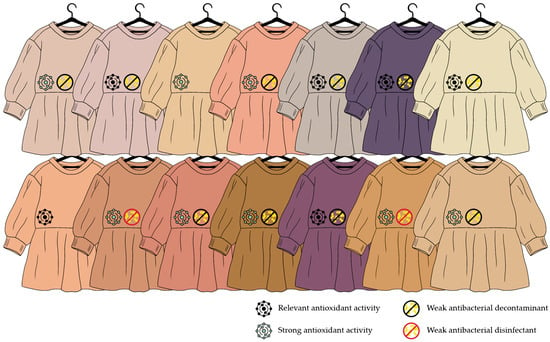

The colour palette achieved in this study demonstrates that chromatic richness and biofunctional performance can coexist, although not always in a linear correlation (Figure 4). Samples that exhibited strong antibacterial activity (madder + tannin and madder + Ppe) tended to produce warm yellow-orange hues, showing that effective microbial reduction does not diminish colour vibrancy. When considering antioxidant activity alongside antibacterial performance, the palette becomes more meaningful: nearly all samples showed antioxidant capacity and retained it even after washing. Overall, the study suggests that the pursuit of multifunctionality does not restrict aesthetic possibilities, instead, it can guide designers towards colour formulations that are both expressive and health protective.

Figure 4.

Overview of the colour palette and corresponding multifunctional properties for each sample applied to a fashion design proposal.

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrated the potential of natural dyes and biomordants as sustainable alternatives to synthetic systems. The incorporation of biomordants and/or colour modifiers in combination with alum improved wash fastness and expanded the chromatic range, producing varied tones.

Functionally, the combination of madder with tannin or madder with Ppe produced considerable antibacterial activity, while the madder + Ppe treatment also exhibited excellent antioxidant performance, comparable to the positive control. These results are especially meaningful for children’s textiles, where such properties support physical comfort and protection against infections. The study also yielded a varied functional palette with yellow, orange, beige, brown, grey, and violet tones.

This work provides an excellent example of the multidisciplinary requirements of textile research and development, intrinsically combining textile design and textile engineering. These findings offer new possibilities for designers by providing natural and non-toxic colour sources that achieve aesthetic versatility without compromising functional protection. While well documented natural dyes limitations still persist, such as limited wash and light fastness, the proven bioactivities and expanded colour potential endorse their application and further development. Ultimately, the development of such textiles aligns with the growing demand for ethical and health-conscious design, contributing to environmental sustainability and the improved wellbeing of children.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, D.S.; methodology, D.S., B.M. and C.A.; formal analysis, D.S., B.M. and C.A.; investigation, D.S., B.M. and C.A.; data curation, D.S., B.M. and C.A.; writing—original draft preparation, D.S., B.M. and C.A.; writing—review and editing, D.S., B.M., C.A., I.C., J.C. and J.P.; validation, D.S., B.M., C.A., I.C., J.C. and J.P.; supervision, I.C., J.C., A.Z. and J.P.; funding acquisition, I.C., J.C., A.Z. and J.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by national funds through FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P. and Programa de Recuperação e Resiliência (PRR) through NextGenerationEU from the European Union, under the Strategic Projects UID/00264/2025 and UID/PRR/00264/2025 of the 2C2T—Centro de Ciência e Tecnologia Têxtil (https://doi.org/10.54499/UID/00264/2025 and https://doi.org/10.54499/UID/PRR/00264/2025). The authors acknowledge the financial support from the integrated BIODyes project (COMPETE2030-FEDER-01480900). The authors Diana Santiago, Behnaz Mehravani, Cátia Alves, and Isabel Cabral also acknowledge the grants supported by MCTES, FSE, UE, and FCT with the references 2021.06351.BD (https://doi.org/10.54499/2021.06351.BD), 2022.13094.BD (https://doi.org/10.54499/2022.13094.BD) and 2022.10454.BD (https://doi.org/10.54499/2022.10454.BD), and junior researcher contract with the reference 2022.08710.CEECIND/CP1718/CT0031 (https://doi.org/10.54499/2022.08710.CEECIND/CP1718/CT0031), respectively.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Niinimäki, K.; Peters, G.; Dahlbo, H.; Perry, P.; Rissanen, T.; Gwilt, A. The Environmental Price of Fast Fashion. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, O.; Fung, B.C.M.; Kharb, D. Factors Influencing Consumer Choice: A Study of Apparel and Sustainable Cues from Canadian and Indian Consumers’ Perspectives. Int. J. Fash. Des. Technol. Educ. 2021, 14, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T.; Repon, M.R.; Islam, T.; Sarwar, Z.; Rahman, M.M. Impact of Textile Dyes on Health and Ecosystem: A Review of Structure, Causes, and Potential Solutions. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 9207–9242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skodova, M.; Glombikova, V.; Komarkova, P.; Havelka, A. Performance of Textile Materials for the Needs of Children with Skin Problems. Fibres Text. 2020, 27, 96–101. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke, A.; Bedwell, C.; Campbell, M.; McGowan, L.; Ersser, S.J.; Lavender, T. Skin Care for Healthy Babies at Term: A Systematic Review of the Evidence. Midwifery 2018, 56, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svedman, C.; Engfeldt, M.; Malinauskiene, L. Textile Contact Dermatitis: How Fabrics Can Induce Dermatitis. Curr. Treat. Options Allergy 2019, 6, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago, D.; Cabral, I.; Cunha, J. Children’s Functional Clothing: Design Challenges and Opportunities. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahriari-Khalaji, M.; Alassod, A.; Nozhat, Z. Cotton-Based Health Care Textile: A Mini Review. Polym. Bull. 2022, 79, 10409–10432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirvan, A.R.; Nouri, A.; Kordjazi, S. Allergies Caused by Textiles and Their Control. In Medical Textiles from Natural Resources; Mondal, M.I.H., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2022; pp. 551–579. ISBN 9780323904797. [Google Scholar]

- Shaharuddin, S.S.; Jalil, M.H.; Moghadasi, K. Study of Mechanical Properties and Characteristics of Eco-Fibres for Sustainable Children’s Clothing. J. Met. Mater. Miner. 2021, 31, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldalbahi, A.; El-Naggar, M.E.; El-Newehy, M.H.; Rahaman, M.; Hatshan, M.R.; Khattab, T.A. Effects of Technical Textiles and Synthetic Nanofibers on Environmental Pollution. Polymers 2021, 13, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berry, H.S.; Ismail, R.K.; Al-Daadi, S.E.; Badr, S.I.O.; Mesbah, Y.O.; Dabbagh, M.A. Measuring Saudi Mothers’ Awareness of Sustainable Children’s Clothing. Open J. Soc. Sci. 2020, 8, 244–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shittu, E.; Lakhanpaul, M.; Vigurs, C.; Sarkar, K.; Koch, M.; Parikh, P.; Campos, L.C. A Rapid Systematic Scoping Review of Research on the Impacts of Water Contaminated by Chemicals on Very Young Children. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 891, 164604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, J.A. Colour in Fashion Design. In Colour Design: Theories and Applications; Best, J., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2017; pp. 299–315. ISBN 9780081018897. [Google Scholar]

- Siu, K.W.M.; Lam, M.S.; Wong, Y.L. Children’s Choice: Color Associations in Children’s Safety Sign Design. Appl. Ergon. 2017, 59, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaharuddin, S.S.; Jalil, M.H. Parents’ Determinants Buying Intent on Environmentally Friendly Children’s Clothing. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2021, 22, 1623–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritch, E.L.; Brownlie, D. Doing It for the Kids: The Role of Sustainability in Family Consumption. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2016, 44, 1100–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago, D.; Cunha, J.; Cabral, I. Chromatic and Medicinal Properties of Six Natural Textile Dyes: A Review of Eucalyptus, Weld, Madder, Annatto, Indigo and Woad. Heliyon 2023, 9, e22013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zannat, A.; Uddin, M.N.; Mahmud, S.T.; Mia, R.; Ahmed, T. Natural Dyes and Pigments in Functional Finishing. In Renewable Dyes and Pigments; Islam, S.U., Ed.; Elsevier: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2024; pp. 271–287. [Google Scholar]

- Zimniewska, M.; Pawlaczyk, M.; Krucinska, I.; Frydrych, I.; Mikolajczak, P.; Schmidt-Przewozna, K.; Komisarczyk, A.; Herczynska, L.; Romanowska, B. The Influence of Natural Functional Clothing on Some Biophysical Parameters of the Skin. Text. Res. J. 2019, 89, 1381–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repon, M.R.; Dev, B.; Rahman, M.A.; Jurkonienė, S.; Haji, A.; Alim, M.A.; Kumpikaitė, E. Textile Dyeing Using Natural Mordants and Dyes: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2024, 22, 1473–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Li, H.; Wan, J.; Liang, L.; Yan, J. Green In-Situ Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles from Natural Madder Dye for the Preparation of Coloured Functional Cotton Fabric. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 208, 117871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamboj, A.; Jose, S.; Singh, A. Antimicrobial Activity of Natural Dyes—A Comprehensive Review. J. Nat. Fibers 2022, 19, 5380–5394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neeta; Arya, N.; Grover, A.; Vaishali. Utilizing Henna and Babool Bark for Antibacterial and UV-Protective Cellulosic Fiber (Cotton) Treatment. Polym. Bull. 2025, 82, 3191–3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago, D.; Cunha, J.; Mendes, P.; Cabral, I. Ultraviolet-Protective Textiles: Exploring the Potential of Cotton Knits Dyed with Natural Dyes. Textiles 2025, 5, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehrani, M.; Ahmadi, S. Ecological Dyeing of Cotton Fabrics with Cochineal: Influence of Bio-Mordants on Colorimetric and Aging Parameters. Fibers Polym. 2025, 26, 3047–3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benli, H. Bio-Mordants: A Review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2024, 31, 20714–20771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinnezhad, M.; Gharanjig, K.; Imani, H.; Razani, N. Green Dyeing of Wool Yarns with Yellow and Black Myrobalan Extract as Bio-Mordant with Natural Dyes. J. Nat. Fibers 2020, 19, 3893–3915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, R.; Sharma, S.; Sharma, R.K. Antimicrobial Textile: Recent Developments and Functional Perspective. Polym. Bull. 2022, 79, 5747–5771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, I.; Yu, J. De Allergic Contact Dermatitis in Children: Recommendations for Patch Testing. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2020, 20, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, M.E.; Anas, M.S.; Jamshaid, H. Engineering an Eco-Friendly Hybrid Bi-Layer Fabric Having Inherently Flame-Resistant & Antibacterial Characteristics for Children’s Protective Clothing. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2024, 49, 102489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nateri, A.S.; Nateri, F.S. Eco-Friendly and Sustainable Antibacterial Functionalization of Medical Textiles Using Natural Dyes: A Review. Results Chem. 2025, 17, 102589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaheh, F.S.; Nateri, A.S.; Mortazavi, S.M.; Abedi, D.; Mokhtari, J. The Effect of Mordant Salts on Antibacterial Activity of Wool Fabric Dyed with Pomegranate and Walnut Shell Extracts. Color. Technol. 2012, 128, 473–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, D.; Xu, H. The Antimicrobial Potential of Plant-Based Natural Dyes for Textile Dyeing: A Systematic Review Using Prisma. Autex Res. J. 2024, 24, 20240016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Koh, J.; Hong, K.H. Sustainable Chitosan Biomordant Dyeing and Functionalization of Cotton Fabrics Using Pomegranate Rind and Onion Peel Extracts. J. Nat. Fibers 2023, 21, 2290856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivarsson, J.; Brieva, P.; Choudhary, H.; Valacchi, G. Evaluating the Effect of Fresh and Aged Antioxidant Formulations in Skin Protection Against UV Damage. Cosmetics 2025, 12, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safapour, S.; Rather, L.J.; Mazhar, M. Coloration and Functional Finishing of Wool via Prangos Ferulacea Plant Colorants and Bioactive Agents: Colorimetric, Fastness, Antibacterial, and Antioxidant Studies. Fibers Polym. 2023, 24, 1379–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzon, G.; Contardi, M.; Quilez-Molina, A.; Zahid, M.; Zendri, E.; Athanassiou, A.; Bayer, I.S. Antioxidant and Hydrophobic Cotton Fabric Resisting Accelerated Ageing. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2021, 613, 126061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouaziz, A.; Dridi, D.; Gargoubi, S.; Chelbi, S.; Boudokhane, C.; Kenani, A.; Aroui, S.; Bouaziz, A.; Dridi, D.; Gargoubi, S.; et al. Analysis of the Coloring and Antibacterial Effects of Natural Dye: Pomegranate Peel. Coatings 2021, 11, 1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krifa, N.; Miled, W.; Behary, N.; Campagne, C.; Cheikhrouhou, M.; Zouari, R. Dyeing Performance and Antibacterial Properties of Air-Atmospheric Plasma Treated Polyester Fabric Using Bio-Based Haematoxylum campechianum L. Dye, without Mordants. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2021, 19, 100372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inprasit, T.; Pukkao, J.; Lertlaksameephan, N.; Chuenchom, A.; Motina, K.; Inprasit, W. Green Dyeing and Antibacterial Treatment of Hemp Fabrics Using Punica Granatum Peel Extracts. Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2020, 2020, 6084127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safapour, S.; Almas, R.; Rather, L.J.; Mir, S.S.; Assiri, M.A.; Rostamzadeh, P. Functional and Photostable Textile Dyeing: A Comparative Study of Natural (Madder, Cochineal) and Synthetic (Alizarin Red S) Dyes on Wool Yarns. J. Text. Inst. 2025, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, Y.; Ma, J.; Gao, W.; Zhang, L.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Zang, J. Pomegranate Peel as a Source of Bioactive Compounds: A Mini Review on Their Physiological Functions. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 887113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferretti, A.; Vermeersch, E.; Sabatini, F.; Degano, I.; Vandenabeele, P. Unlocking the Secrets of Historical Violet Hues: A Spectroscopic and Mass Spectrometric Investigation of Logwood Ink Recipes. Dye. Pigment. 2025, 239, 112757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, H.; Yan, J.; Ji, X.; Xu, L. Preparation and Properties of Cotton Fabric Photocatalyzed by Ag-Doped Madder-Sensitized TiO2. J. Macromol. Sci. Part B Phys. 2025, 64, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, L.; Yan, J. Dyeing Property Improvement of Madder with Polycarboxylic Acid for Cotton. Polymers 2021, 13, 3289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pour, R.A.; Bagheri, R.; Naveed, T.; Ali, N.; Rehman, F.; He, J. Surface Functionalization of Wool via Microbial-Transglutaminase and Bentonite as Bio-Nano-Mordant to Achieve Multi Objective Wool and Improve Dyeability with Madder. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, S.; Ali, M.; Islam, S.; Iqbal, M.O.; Al-Rawi, M.B.A.; Naseem, M. Enhancing the Antibacterial Properties of Silver Particles Coated Cotton Bandages Followed by Natural Extracted Dye. J. Ind. Text. 2025, 55, 15280837251320571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Zawahry, M.; Gamal, H. A Facile Approach for Fabrication Functional Finishing and Coloring Cotton Fabrics with Haematoxylum campechianum L. Bark. Pigment. Resin Technol. 2025, 54, 661–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutrup, J.; Ellis, C. The Art and Science of Natural Dyes: Principles, Experiments, and Results, 1st ed.; Schiffer Publishing, Ltd.: Atglen, PA, USA, 2019; ISBN 978-0-7643-5633-9. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 105-C06; Textiles—Tests for Colour Fastness—Part C06: Colour Fastness to Domestic and Commercial Laundering. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010.

- Ribeiro, A.I.; Vieira, B.; Alves, C.; Silva, B.; Pinto, E.; Cerqueira, F.; Silva, R.; Remião, F.; Shvalya, V.; Cvelbar, U.; et al. Halochromic Silk Fabric as a Reversible PH-Sensor Based on a Novel 2-Aminoimidazole Azo Dye. Polymers 2023, 15, 1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berns, R.S. Billmeyer and Saltzman’s: Principles of Color Technology: Fourth Edition, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; ISBN 9781119367314. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 105-N05:1993; Textiles—Tests for Colour Fastness—Part N05: Colour Fastness to Stoving. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1993.

- Alves, C.; Soares-Castro, P.; Fernandes, R.D.V.; Pereira, A.; Rodrigues, R.; Fonseca, A.R.; Santos, N.C.; Zille, A. Application of Prodigiosin Extracts in Textile Dyeing and Novel Printing Processes for Halochromic and Antimicrobial Wound Dressings. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermosilla, J.; Alves, C.; Zille, A.; Padrão, J.; Sanhueza, C.; Pastene-Navarrete, E.; Acevedo, F. Electrospun Fibers Loaded with Extracts of Gunnera Tinctoria and Buddleja Globosa with Potential Application in the Treatment of Skin Lesions. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2026, 115, 107628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, B.; Padrão, J.; Alves, C.; Silva, C.J.; Vilaça, H.; Zille, A. Enhancing Functionalization of Health Care Textiles with Gold Nanoparticle-Loaded Hydroxyapatite Composites. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freitas, A.S.; Oliveira, R.; Ribeiro, A.; Almeida-Aguiar, C. Biofunctional Textiles: Antioxidant and Antibacterial Finishings of Cotton with Propolis and Honey. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negi, A. Natural Dyes and Pigments: Sustainable Applications and Future Scope. Sustain. Chem. 2025, 6, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, T.H.; Grethe, T.; Mahltig, B. Wood Extracts for Dyeing of Cotton Fabrics—Special View on Mordanting Procedures. Textiles 2024, 4, 138–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otaviano, B.T.H.; Sannomiya, M.; de Queiroz, R.S.; Sánchez, A.A.C.; Freeman, H.S.; Mendoza, L.E.R.; Veliz, J.L.S.; Leon, M.M.G.; Leo, P.; Costa, S.A.d.; et al. Natural Dye Extracted from Pomegranate Peel: Physicochemical Characterization, Dyeing of Cotton Fabric, Color Fastness, and Photoprotective Properties. Fibers Polym. 2023, 24, 1321–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davulcu, A.; Benli, H.; Şen, Y.; Bahtiyari, M.İ. Dyeing of Cotton with Thyme and Pomegranate Peel. Cellulose 2014, 21, 4671–4680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Zhao, K.; Hou, X.; Zhang, Y. Multifunctional Cotton Fabric with Directional Water Transport, UV Protection and Antibacterial Properties Based on Tannin and Laser Treatment. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2023, 664, 131131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolau, T.; Filho, N.G.; Padrão, J.; Zille, A. A Comprehensive Analysis of the UVC LEDs’ Applications and Decontamination Capability. Materials 2022, 15, 2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; Dong, R.; Peng, J.; Tian, X.; Fang, D.; Xu, S. Comparison of the Effect of Extraction Methods on Waste Cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) Flowers: Metabolic Profile, Bioactive Components, Antioxidant, and α-Amylase Inhibition. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2023, 103, 6463–6472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molino, S.; Fernández-Miyakawa, M.; Giovando, S.; Rufián-Henares, J.Á. Study of Antioxidant Capacity and Metabolization of Quebracho and Chestnut Tannins through in Vitro Gastrointestinal Digestion-Fermentation. J. Funct. Foods 2018, 49, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.; Jalil, M.A.; Belowar, S.; Saeed, M.A.; Hossain, S.; Rahamatolla, M.; Ali, S. Role of Mordants in Natural Fabric Dyeing and Their Environmental Impacts. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 32, 452–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.