Abstract

Wind power forecasting is critical to renewable energy generation, as accurate predictions are essential for the efficient and reliable operation of power systems. However, wind power output is inherently unstable and is strongly affected by meteorological factors such as wind speed, wind direction, and atmospheric pressure. Weather conditions and wind power data are recorded by sensors installed in wind turbines, which may be damaged or malfunction during extreme or sudden weather events. Such failures can lead to inaccurate, incomplete, or missing data, thereby degrading data quality and, consequently, forecasting performance. To address these challenges, we propose a method that integrates a pre-trained large-scale language model (LLM) with the spatiotemporal characteristics of wind power networks, aiming to capture both meteorological variability and the complexity of wind farm terrain. Specifically, we design a spatiotemporal graph neural network based on multi-view maps as an encoder. The resulting embedded spatiotemporal map sequences are aligned with textual representations, concatenated with prompt embeddings, and then fed into a frozen LLM to predict future wind turbine power generation sequences. In addition, to mitigate anomalies and missing values caused by sensor malfunctions, we introduce a novel frequency-domain learning-based interpolation method that enhances data correlations and effectively reconstructs missing observations. Experiments conducted on real-world wind power datasets demonstrate that the proposed approach outperforms state-of-the-art methods, achieving root mean square errors of 17.776 kW and 50.029 kW for 24-h and 48-h forecasts, respectively. These results indicate substantial improvements in both accuracy and robustness, highlighting the strong practical potential of the proposed method for wind power forecasting in the renewable energy industry.

1. Introduction

Rapid urbanization and surging energy demands necessitate efficient energy governance solutions for sustainable smart cities [1]. Consequently, the expansion of renewable energy, particularly wind power and photovoltaics, has become integral to urban energy systems. In line with China’s dual-carbon goals, non-fossil fuels are projected to comprise 25% of the nation’s total energy consumption by 2030 [2]. However, while wind power is a key sustainable resource, its inherent intermittency poses challenges for grid integration. Therefore, accurate wind power forecasting is essential to ensure the reliability and cost-effectiveness of urban energy management.

Over the past decade, numerous wind power forecasting approaches have been proposed to aid decision-making. These methods [3] are generally categorized into two groups: physical and statistical. Physical methods rely on detailed characterizations of the local environment to model wind turbines or farms. This is typically achieved by downscaling Numerical Weather Prediction (NWP) data, which necessitates comprehensive inputs regarding the target area, such as surface roughness, obstacles, and meteorological variables (e.g., temperature and pressure). These inputs drive complex, often computationally intensive mathematical models to estimate wind speed. The predicted speed is subsequently mapped to a manufacturer-supplied power curve to generate power forecasts. For instance, Focken et al. [4] developed a physical forecasting method for time horizons up to 48 h. Their model estimates wind speed at hub height by adjusting the atmospheric boundary layer to account for surface roughness, terrain features, wake effects, and variations in thermal stratification.

Statistical methods infer underlying trends by exploiting statistical patterns in historical data and by modeling linear or nonlinear relationships between NWP variables—such as wind speed, wind direction, and temperature—and power output. Firat et al. [5] proposed a statistical wind speed forecasting model based on independent component analysis combined with an autoregressive framework. Yunus et al. [6] applied a frequency decomposition approach based on the Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) model to predict short-term wind power generation. Wang et al. [7] employed Support Vector Machines (SVMs) for short-term wind power forecasting. Zhao et al. [8] utilized gated recurrent units (GRUs) to capture short-term temporal dependencies, combined with a Temporal Linear Layer (TLinear) to model long-term relationships, and further introduced the probabilistic forecasting model Deep Factor to predict both the mean and standard deviation of wind power output. Yin et al. [9] used a single-hidden-layer feedforward neural network, known as an extreme learning machine (ELM), for wind power forecasting, with crisscross optimization applied to optimize the ELM model parameters.

Although numerous methods have been proposed, they are increasingly insufficient to meet the growing demands for high accuracy and efficiency in multi-step wind power forecasting. A key limitation is that many existing approaches fail to adequately capture two critical factors: the spatial correlations among wind turbines and the temporal dependencies inherent in historical wind power data. First, most wind power forecasting models are designed for individual turbines and typically rely only on local variables such as wind speed and air density. However, the power output of neighboring turbines can influence one another, as wind power evolution is closely related to the spatial topology of the turbine network. Second, wind power exhibits strong temporal characteristics that are essential for accurate prediction. It displays seasonal, periodic, and trend components, and generally varies smoothly across adjacent time intervals. Consequently, both spatial and temporal correlations must be jointly modeled to achieve accurate and reliable wind power forecasting.

2. Related Works

Wind power forecasting is a crucial task that aids in optimizing the operation and management of wind farms. Traditional methods such as time-series models (e.g., ARIMA) and support vector machines (SVM) primarily rely on historical time information, neglecting spatial dependencies within and around the wind farm. To enhance the accuracy of future wind power predictions, researchers have increasingly turned to deep learning methods to capture the complex spatio-temporal patterns of wind farms. Most deep learning approaches fall into three categories: Transformer-based, Generative Adversarial Network (GAN)-based, and Graph Neural Network (GCN)-based methods.

Transformer models have demonstrated superior performance in wind power forecasting compared to traditional Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, primarily due to their ability to capture long-range temporal dependencies. Several variants have been proposed to enhance this capability. Tan et al. [10] applied BERT to generative forecasting, utilizing post-processing to reduce output volatility. Wu et al. [11] introduced Autoformer, which uses a decomposition framework to model trend and seasonal components via autocorrelation. Similarly, Zhou et al. [12] proposed Fedformer, which combines frequency-domain Fourier transforms with attention mechanisms for effective denoising. Building on these decomposition methods, Liang et al. [13] developed WPFFormer to apply self-attention separately to seasonal and trend components. Other approaches focus on architectural efficiency and multivariate modeling. Liu et al. [14] proposed PYRAformer, utilizing a pyramid attention mechanism to minimize computational complexity while retaining long-term dependency modeling. Dai et al. [15] introduced VTformer, a lightweight model employing multiscale linear attention to capture variate-wise dependencies and comprehensive multivariate correlations. Conversely, Liu et al. [16] introduced iTransformer, which inverts the standard paradigm by embedding entire time series as tokens to better model temporal patterns. While these methods excel at handling complex temporal dynamics, they face significant limitations. Most overlook the spatial correlations between different turbines or sites, limiting their utility in multi-location scenarios. Furthermore, the high computational cost of attention mechanisms and the requirement for large-scale datasets remain challenges for stable training and generalization.

In recent years, GAN has been considered an effective algorithm for capturing the intermittency and volatility of wind power generation, as it avoids the need for complex feature extraction and tedious manual annotation in traditional data-driven models. Zhang et al. [17] proposed a GAN-based framework for conditional improved wind power generation scenarios, modeling high-quality representations for uncertain wind power scenarios through classification clustering, predictive label condition scene generation, and scene reduction processes. Yuan et al. [18] introduced PG-GAN, constructing a comprehensive multi-objective scenario prediction model to capture complex temporal dynamics and pattern correlations. They addressed multi-objective scenario prediction using an evolutionary optimization algorithm based on progressive improvement, achieving wind power generation forecasts for specific days. GAN-based methods are effective at generating diverse and realistic wind power scenarios, capturing uncertainty and volatility that deterministic models overlook. However, GANs suffer from unstable training, mode collapse, and sensitivity to hyperparameters. They also struggle to preserve long-term temporal consistency and physical interpretability in the generated outputs, which limits their reliability for operational forecasting.

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) are well suited for modeling non-Euclidean relationships by aggregating and propagating information among neighboring nodes. As a result, GNNs have been widely applied to wind power forecasting. Li et al. [19] integrated GNNs with deep residual networks (DRNs) for short-term wind power prediction. Jiang et al. [20] employed the Adaptive Graph Convolutional Recurrent Network (AGCRN), which captures correlations across nodes and time series through node-adaptive parameter learning (NAPL) and data-adaptive graph generation (DAGG) modules. Wu et al. [21] proposed the Multivariate Time Series Graph Neural Network (MTGNN), a generic GNN framework that automatically learns unidirectional relationships among variables, incorporates external knowledge and produces spatiotemporal predictions by combining temporal and graph convolution modules. Ye et al. [22] enhanced GNN-based multivariate time series forecasting by constructing multiple evolving graph structures to model interactions among time series, capturing scale correlations via dilated convolutions. Li et al. [23] introduced STFGNN, which adopts a data-driven approach to generate temporal graphs and compensate for correlations that spatial graphs alone may fail to capture. DSTAGNN [24] proposed a tensor-decomposition-inspired dynamic graph constructor. Dong et al. [25] developed a spatiotemporal convolutional network (STCN) with directed graph convolutions to model temporal characteristics of wind power. He et al. [26] proposed TEA-GCN, which alternates between adaptive graph convolutions to learn dynamic spatial dependencies and temporal attention mechanisms for traffic flow prediction. Zong et al. [27] presented MSSTGCN, which combines multi-head self-attention with spatiotemporal GCNs to handle time-series periodicities via multi-scale temporal segmentation, along with a graph attention residual layer to model spatial relationships across regions. These models effectively capture spatial dependencies among wind turbines and integrate them with temporal dynamics, making them well-suited for multi-site wind power forecasting. They can model complex non-Euclidean relationships and dynamically adapt to topological changes. However, they often rely on pre-defined or static graph structures that may not accurately reflect time-varying spatial correlations. Additionally, graph construction and training can be computationally intensive, and over-smoothing or information loss may occur as the number of graph layers increases.

3. Methodology

The instability of wind power is a primary constraint in wind energy generation. Wind power generation, reliant on natural energy sources, experiences electrical output influenced by various meteorological factors like wind speed, wind direction, and atmospheric pressure. The fluctuation in these meteorological factors results in the volatility of wind power. Beyond meteorological aspects, factors such as the terrain and altitude of the wind farm impact wind power forecasting. Variances in terrain and altitude across wind farms lead to diverse patterns of wind speed and direction, subsequently affecting wind power output. Additionally, factors like wind farm layout and the type and quantity of wind turbines also impact wind power forecasting.

To address these challenges, inspired by the success of Large Language Model (LLM), this paper introduces a spatio-temporal LLM with excellent generalization ability on the task of wind power prediction, named WPFGPT. The model comprises two modules. The first part utilizes a pre-trained LLM to extend its powerful inference capability to the wind power prediction domain. The second part utilizes an Interpolation Module Based on Frequency Domain Learning to handle missing and outlier data in the dataset. Specifically, WPFGPT integrates a spatio-temporal dependency encoder based on graph convolutional networks, which enables the model to capture the complex temporal dynamics present in the spatio-temporal data at different temporal resolutions. It represents the relationship between multiple wind turbines in a wind farm as a graph structure, which embeds spatial information in the spatio-temporal data. Furthermore, by effectively aligning the textual information with the encoded spatio-temporal information and using prompt instruction tuning technique, the LLM can understand the spatio-temporal prediction task context in order to make more accurate predictions. The interpolation model, based on frequency domain decomposition, complements datasets with missing time series values, further enhancing the robustness of wind power forecasting in the presence of missing data.

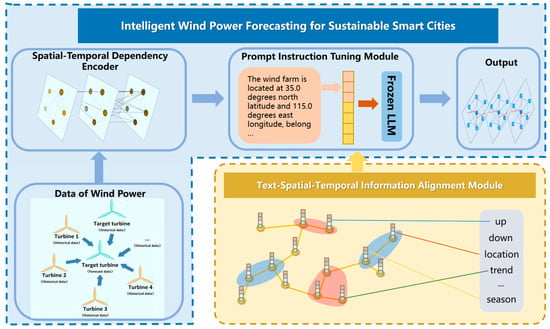

3.1. Spatio-Temporal LLM

Traditional neural architectures for wind power forecasting, such as Transformer-, GAN-, and GNN-based models, typically emphasize either temporal dependency modeling or spatial correlation learning, but often lack semantic understanding and generalization across heterogeneous data sources. In contrast, large language models (LLMs) exhibit strong generalization, reasoning, and cross-modal alignment capabilities, enabling them to integrate structured spatiotemporal data with textual or semantic priors. Accordingly, WPFGPT extends the LLM architecture with dedicated modules that explicitly encode spatiotemporal dependencies and align them with textual representations, allowing for interpretable and adaptable wind power forecasting under diverse operating conditions. The overall framework of our proposed WPFGPT for wind power forecasting is shown in Figure 1. It mainly consists of three components, including the spatio-temporal dependency encoder module, the text-spatio-temporal information alignment module and the prompt instruction tuning module. In this section, we will first give a brief introduction to the three components and then describe them in detail in the following subsections.

Figure 1.

Overall Pipeline for Wind Power Forecasting.

The spatio-temporal dependency encoder module enhances the LLM’s ability to model spatial relationships in spatiotemporal data by embedding spatial features using graph convolutional networks. By exploiting the graph structure of historical wind turbine data, this module captures interactions among turbines and improves the model’s understanding of complex spatiotemporal dependencies.

The text–spatio-temporal information alignment module enables effective integration of textual and spatiotemporal modalities. By aligning textual context with historical spatiotemporal wind power data, this module facilitates multimodal fusion and activates the transfer learning and inference capabilities of the LLM, thereby improving its interpretation of spatiotemporal representations.

The prompt instruction tuning module incorporates rich temporal and spatial semantics into the LLM input to support spatiotemporal prediction. Temporal information includes features such as the day of the week and hour of the day, while spatial information includes turbine locations, distances between neighboring turbines, and geographic attributes. This design allows the LLM to recognize and model spatiotemporal patterns across multiple temporal and spatial scales.

3.1.1. Problem Formalization

Wind power forecasting aims to forecast wind power for all wind power nodes with the historical power series in a period of future time. We define wind power data as , where N represents the number of wind turbines, P represents the historical timesteps and C represents the number of features.

The objective of wind power prediction is to predict the wind power of all wind power nodes in a future period using historical power series. Given a historical P step spatio-temporal graph signal, the target is to learn a function f that can predict its next T step spatio-temporal graph signals. The mapping relation is represented as follows:

3.1.2. Spatio-Temporal Dependency Encoder Module

The wind turbines exhibit inherent spatial correlations in neighboring spaces. The closer the distance between two wind turbines, the more their wind power generation is mutually influenced, thereby indirectly influencing the overall wind energy. However, pre-trained LLMs face challenges in capturing such spatially non-Euclidean relationships. While these models perform well with textual or serialized data, they are limited in their ability to understand and model spatial interactions between wind turbines.

Graph convolutional network has become a promising and powerful technique to learn the non-Euclidean relationship [28]. In this study, to extract effective spatial features from complex topologies, we use graph convolutional neural networks (GCN) as an encoder to learn features in non-Euclidean space from spatio-temporal graph data of wind power generation to capture spatial dependencies among nodes.

Graph Construction Firstly, we adopt multiple perspectives to examine the spatial relationships between wind turbines, constructing various graphs to represent the connections among individual turbines. The graph construction methods encompass relative geographical distance graphs, semantic distance graphs, and learning graphs. This approach allows graph neural networks to consider the interactions between wind turbines from different perspectives and achieves accurate dependency embedding of spatial relationships by capturing dynamic spatio-temporal features in wind power data.

The construction of the geographical distance graph utilizes the relative geographical relationships between wind turbines. Data analysis reveals that the geographical location of wind turbines significantly influences their power generation. Therefore, based on the coordinates provided for each turbine in the data, the Euclidean distance between two turbines is computed to obtain the geographical distance matrix . Additionally, considering that turbines closer in distance share more similar geographical locations and environments, thereby exerting a greater impact on power generation, the following weighted formula is defined to derive the geographical distance graph :

In the equation, represents the distance between wind turbine and wind turbine . denotes the standard deviation of the distances, and represents a predefined threshold, set here as 0.8. By setting the threshold, the sparsity of the adjacency matrix is increased, reducing complexity.

The construction of the wind power similarity graph involves computing the Dynamic Time Warping (DTW) similarity between different wind turbines’ power generation profiles [29]. The principle behind DTW is to find the optimal alignment between two time series by warping one time series relative to the other. Warping is achieved by stretching or compressing a sequence’s time axis, minimizing the distance between the two sequences after the warping operation. The specific process begins by arranging sequences and into an grid, where each point represents the alignment between and . The optimal path can be computed through the following procedure:

In the equation, represents the Euclidean distance between points and . The total path length can be calculated using the following formula:

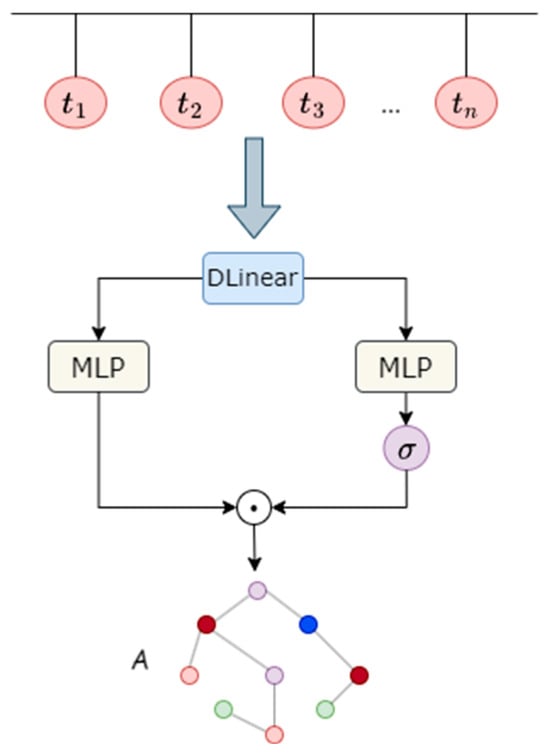

The construction of the learning graph involves adjusting the graph adjacency matrix with learnable parameters to capture hidden relationships between time series data. To enable the learning graph to adequately represent relationships between wind turbines, historical time series are first passed through a DLinear layer [30]. This layer aims to comprehensively learn the trend and seasonality features of the sequences. The learning process of the DLinear layer is defined by the following formula:

In Equation (5), represents the trend features of the sequence, represents the seasonality features of the sequence, and denotes the sliding average operation. The parameter represents the sum of trend and seasonality sequences after passing through the linear layer.

After extracting information from the time series, two linear layers are utilized to encode the output sequences of the DLinear layer [30] into a latent space, obtaining the embedding representation of the nodes. Additionally, a sigmoid function is appended after one of the linear layers to serve as a mask, controlling the output information ratio:

Here, and represent the values of the learned graph structure and mask at the row and column. denotes the sigmoid activation function, and is the learned graph structure for the time period. The learning graph module is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Dynamic Graph Learning Module.

Graph Convolutional Network. Given the adjacency matrix A and the node embedding X, the powerful graph convolutional network can perform the message passing between different nodes in the spectral domain based on the adjacency matrix to perform convolution operations on the node features. From a spatial-based perspective, the graph convolution operator could aggregate its neighborhood information. Here, is the adjacency matrix of the undirected graph G with added self-connections. is the identity matrix, . The graph convolution layer is written as:

where is the matrix of activations in the lth layer, is a layer-specific trainable weight matrix and denotes an activation function, such as the .

In this paper, we use a two-layer GCN for extracting the spatial dependencies. Our forward model then takes the simple form:

Here, we first calculate in a pre-processing step. is an input-to-hidden weight matrix for a hidden layer where P is the length of the feature matrix, and H is the number of hidden layers. is a hidden-to-output weight matrix, and is hyperbolic tangent function.

The spatial feature learning module is designed to model the spatial relationships among wind turbines within a wind farm. Each turbine is treated as a node in a graph, and the connections between turbines represent their physical or functional relationships. For a given central turbine, the module aggregates information from its neighboring turbines to obtain a comprehensive spatial representation. This aggregation allows the model to capture how changes in one turbine’s power output affect others nearby, thereby reflecting the spatial dependencies in wind power variations. The resulting spatial features are then embedded into the original spatio-temporal graph data, enabling the model to jointly learn spatial and temporal patterns during subsequent forecasting.

3.1.3. Text-Spatio-Temporal Information Alignment Module

For the language model to effectively understand the patterns of spatio-temporal graph data, we align the textual information with the spatio-temporal information to reduce the gap between the source and target data domains. This alignment also allows for the fusion of different patterns, resulting in a more informative representation. By integrating contextual features from the textual and wind power spatio-temporal domains, we can capture complementary information and extract high-level semantic representations that are more expressive and meaningful. To achieve this goal, we utilize a lightweight alignment module to project spatio-temporal dependency representations . We first map the feature dimension of to , where is the hidden dimension of LLM, and the result is represented as . After that, we use cross-attention to align from the spatio-temporal modality to the textual modality , where is the size of the alphabet. Specifically, we use three linear transformations to obtain the query, key and value matrices:

where represents the word embedding from LLM, represents the spatio-temporal dependencies, and , , are learnable parameters. The attention scores are computed using the scaled dot-product attention mechanism:

The updated representations contain enriched information that captures both the linguistic context and the spatio-temporal patterns.

In our WPFGPT framework, a pre-trained LLaMA3.2-3B model [31] is adopted as the backbone large language model. The parameters of this LLM are frozen during training, meaning that they are not updated by gradient descent. This design choice is motivated by two factors: (1) the LLM has already learned extensive generalization and reasoning knowledge during its large-scale pre-training, and (2) freezing the parameters significantly reduces GPU memory usage and computational cost while maintaining strong generalization ability. Consequently, only the lightweight alignment and prediction modules are trainable, allowing efficient adaptation of the LLM to spatio-temporal forecasting tasks.

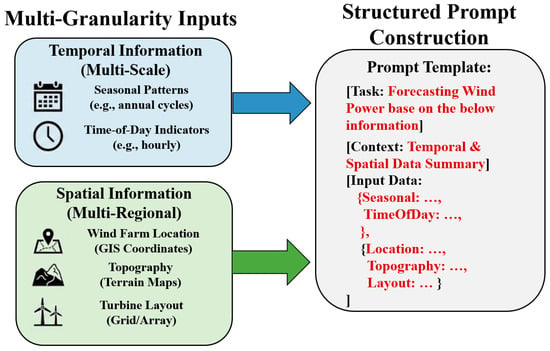

We integrate multi-granularity temporal and spatial information as prompt inputs to the frozen LLM. Temporal information includes seasonal patterns, time-of-day indicators, and historical wind power data, while spatial information comprises wind farm location, topography, and turbine layout. This structured prompting enables WPFGPT to recognize and assimilate spatio-temporal dependencies across multiple scales and geographic regions, thereby enhancing forecasting accuracy and interpretability.

Figure 3 illustrates the integration of spatio-temporal information into the instructional text for wind power forecasting. As illustrated in the figure, the process begins with the aggregation of multi-granularity inputs, distinguishing between multi-scale temporal features (e.g., seasonal patterns, time-of-day indicators) and multi-regional spatial attributes (e.g., GIS coordinates, topography, turbine layouts). These disparate data streams are synthesized through a structured prompt construction mechanism, which organizes information into distinct functional blocks—specifically [Task], [Context], and [Input Data]. By serializing numerical and categorical variables into a context-rich natural language template. After performing the alignment, we concatenate the prompt embeddings with sequence embeddings after performing the alignment and input them into the frozen LLM. The portion of the LLM output corresponding to the cue embedding is then discarded to obtain the desired output representation. Subsequently, we project the temporal and feature dimensions of this output representation separately using two linear layers to derive the final prediction . This process can be defined by the following equation:

where represents the prompt embedding, represents the output through the frozen LLM, represents Multilayer Perceptron, represents the output representation with the input prompt embedding part removed, and represents the final prediction output.

Figure 3.

The construction process of a structured prompt.

3.2. Interpolation Module Based on Frequency Domain Learning

Due to the high correlation between the wind power sequence and the wind speed at the location of the wind turbine, and the extremely complex temporal variations in wind speed influenced by various factors, relying solely on time series prediction models such as GRU and Transformer to model sequence features is challenging to extract reliable temporal dependencies. This limitation also leads to suboptimal interpolation results for time series.

Observing real-world time series data reveals that time series in reality are often a superposition of various sequences with fixed frequencies. For instance, traffic flow sequences exhibit daily and weekly variations, and weather data sequences display strong seasonal trends. Wind power time series are no exception, possessing multi-periodic attributes: rapid daytime surface temperature increases cause upward air movement, supplemented by the flow of colder air from the surroundings, resulting in increased wind speed due to a larger pressure difference; rapid nighttime surface cooling from radiative heat loss leads to weak down-sloping inversions, reducing surface air movement, making daytime wind speeds stronger than nighttime. Wind speed has a strong correlation with temperature changes, and temperature exhibits seasonal characteristics, causing wind speed to also display seasonal features.

The multi-periodic nature of time series makes temporal changes too complex. Solely relying on time series prediction models based on fixed periods for feature extraction leads to features that cannot effectively represent the entire time series. For a specific time series of data, the temporal changes at each time point are not only related to adjacent moments but also highly correlated with adjacent periods, exhibiting both intra-period and inter-period temporal changes [32]. Based on this observation, wind farm sites, with this multi-periodic attribute, naturally inspire the design of the interpolation model. The proposed approach involves first transforming the time series data into the frequency domain using Fourier transform. In the frequency domain, the periodicity of time series can be reflected through the spectrum, as expressed by:

Here, represents the Fast Fourier Transform, denotes the computation of the amplitude for each feature, and represents the calculation of the average amplitude of all features in the frequency domain.

In the frequency domain, select the top several frequency components with the highest energy. Based on the selected frequency components, decompose the original sequence as follows:

In this Equation, corresponds to the top frequencies with the maximum amplitudes, and corresponds to the prominent top periods.

This frequency-based decomposition method allows for the separation of complex temporal variations, facilitating the learning of features in time series data.

After decomposing the original time series based on frequency, to simultaneously analyze intra-period and inter-period sequence variations, it is necessary to expand the one-dimensional time series data into two-dimensional space for analysis, as shown in the following equation:

For the transformed two-dimensional vector, each column corresponds to intra-period sequences, and each row corresponds to inter-period sequences. Adjacent moments and periods often contain similar temporal variations. Therefore, 2D convolution operations can easily capture features of the time series.

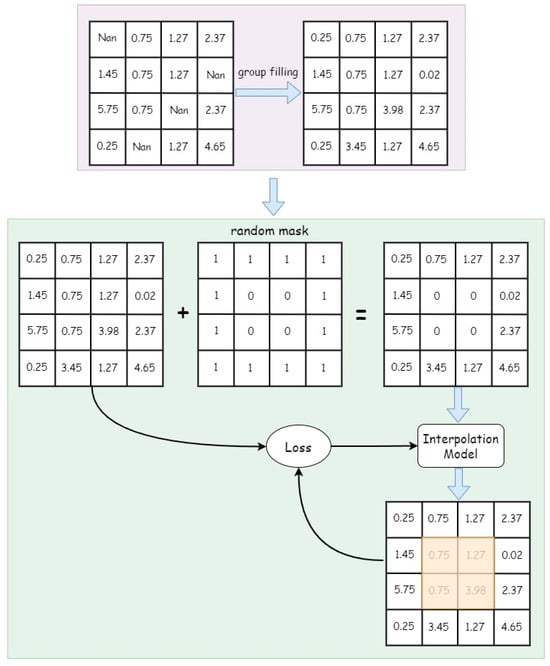

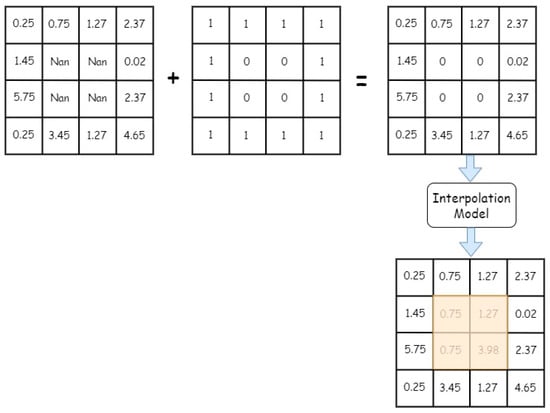

The above model, through learning multi-dimensional features in the time series, can effectively reconstruct missing values in the time series data. For the training process of the interpolation model, a self-supervised learning approach with random masking is employed. Specifically, the original sequence is first randomly masked, input to the model to learn the sequence representation, and the model outputs an estimate of the original sequence. Loss is then computed only for the masked part. Since missing values and outliers exist throughout the entire time series, and the self-supervised learning training process requires real labels for the original data, for the training and validation sets, missing values are first imputed using a grouping filling approach before training. The specific training process is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Training Process for Interpolation Module.

For missing values in the original sequence, as the data inherently lacks real labels, during the prediction phase, it is necessary to construct the corresponding mask matrix based on the positions of the missing values. The specific process is illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Forecasting Process for Interpolation Module.

The proposed interpolation module in this paper transforms the time series into the frequency domain through Fourier transform. Within the frequency domain, it selects the top several periods with the maximum amplitudes for decomposition, aiming to capture both intra-period and inter-period features of the wind power sequence simultaneously. During the training process, a self-supervised approach is employed to uncover the inherent temporal characteristics of the sequence, contributing to the effective reconstruction of missing data.

4. Experiments

4.1. Dataset Description

This study conducted an evaluation on a real-world dataset SDWPF [33] obtained from Longyuan Electric Power Group Co., Ltd (Beijing, China). The dataset comprises historical wind power and dynamic environmental factor data spanning 245 days for training and validation. It includes the geographic relative positions of 134 wind turbines, and separately provides wind power and dynamic environmental data for 17 days for testing. The historical sequence has a time interval of 10 min. More information can be found at: https://aistudio.baidu.com/competition/detail/152/0/introduction (accessed on 19 November 2025).

In the experiment, wind power data underwent normalization. The dataset of 245 days was split into a training set and a validation set in an 8:2 ratio. The first 196 days of data were used as the training set, while the subsequent 49 days were used as the validation set. The dataset of 17 days was designated as the test set. The input time series had a length of 288, representing wind power data over a span of 48 h. The objective of the experiment was to forecast the active power data for each wind turbine in the upcoming 24 to 48 h.

4.2. Evaluation Metrics

A number of commonly utilized evaluation metrics have been utilized for assessment, including Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) and Mean Absolute Error (MAE). The detailed description is as follows.

Root Mean Squared Error, RMSE:

Mean Absolute Error, MAE

where M is the number of time series samples, N is the number of turbines, and denote the ground-truth wind power and predicted wind power. For these metrics, a lower value indicates a better performance of wind power forecasting.

The two mentioned metrics serve as measures of prediction error, with lower values indicating better predictive performance.

4.3. Experimental Settings

The experimental setup utilized an NVIDIA GeForce GTX 3090 GPU. During training, the historical observation step was set to 288, meaning the model utilized past 48 h (48 × 6) of observations to predict future features. The model consisted of 3 spatio-temporal convolution blocks (), 2 layers in the graph convolutional network (), and 12 layers in the frozen LLM. The batch size during training was set to 32, and the model was trained for 30 epochs. The experiment was conducted across three independent runs using distinct random seeds. The mean and variance were calculated and reported. The Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate of 0.001 was employed to optimize the Huber loss, defined by the following equation:

We compare WPFGPT with the following mainstream approaches as the following.

Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) [34] is a type of recurrent neural network (RNN) architecture designed to handle sequential data by addressing issues like vanishing gradients in traditional RNNs through the use of gating mechanisms. It employs two primary gates: the reset gate, which determines how much past information to forget, and the update gate, which controls how much of the previous hidden state to carry over while incorporating new input. This structure allows GRUs to maintain long-term dependencies in sequences more effectively than vanilla RNNs, with fewer parameters than Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) units, leading to faster training and computation.

Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LightGBM) [35] is a machine learning framework based on the Gradient Boosting Decision Tree (GBDT) algorithm. It is capable of efficiently and rapidly training large-scale, high-dimensional datasets. For time series forecasting, LightGBM can be adapted by transforming the sequential data into a supervised learning format through feature engineering, such as creating lagged variables, extracting temporal features like day of week or seasonal indicators, and incorporating rolling statistics or external regressors.

Spatial-temporal Graph Convolutional Network (STGCN) [36] combines graph convolution with temporal convolution. It models spatio-temporal graph data by treating the network as a graph and applying graph convolution to capture spatial dependencies among road segments. It replaces recurrent temporal modelling with gated temporal convolutional layers to capture temporal dependencies efficiently and enable full convolutional training.

iTransformer [16] repurposes the standard Transformer architecture by inverting the dimensions for multivariate time series forecasting, embedding time points of individual series into variate tokens rather than fusing multiple variates into temporal tokens. This allows the attention mechanism to operate on these variate tokens, effectively capturing multivariate correlations across series, while the feed-forward network is applied to each variate token to learn nonlinear representations specific to individual series.

VTformer [15] employs a vanilla Transformer encoder backbone to address long-term multivariate time series forecasting by processing input sequences through an embedding layer that generates dual representations: temporal embeddings via convolutional value encoding combined with time and position encodings, and variate embeddings via linear projection on transposed data to capture cross-variate correlations.

TEA-GCN [26] employs a layered architecture with alternating local-global temporal attention and adaptive graph convolutional modules to capture dynamic spatial-temporal dependencies, using three spatial-temporal blocks to process input data. The local-global temporal attention module extracts short-term patterns via gated one-dimensional convolutions and long-term dependencies through a transformer encoder–decoder with enhanced periodic positional embeddings, followed by an adaptive fusion using learnable weights and softmax to integrate these representations.

Multi-Head Self-Attention and Spatial-Temporal Graph Convolutional Network (MSSTGCN) [27] employs a Graph Attention Residual Network (GARN) layer to learn global spatial dependencies across regions through multi-head attention mechanisms, linear transformations, and residual connections, complemented by a T-GCN module that integrates GCN with GRU to model local spatial-temporal dependencies via normalized Laplacian matrices and gating mechanisms.

4.4. Experimental Results

Wind power forecasting model WPFGPT was compared with five benchmark methods on the SDWPF dynamic wind power forecasting dataset. Table 1 presents the results for forecasting future 24 and 48 h. Each experiment was repeated three times using a different seed. The table records the mean and standard deviation of the experimental results. The visualization of the forecasting results for each model on the test set is depicted in Figure 6, indicating discernible differences in the forecasting performances among the various models. Particularly, the proposed model demonstrates superior performance compared to the others, depicting a forecasted trend line that closely resembles the actual trend.

Table 1.

Performance comparison between the proposed WPFGPT and five baseline models. RMSE and MAE are measured in kW, and Avg denotes the average of RMSE and MAE. The bolded result indicates the best outcome.

Figure 6.

The forecasting curves of power generation for different turbines by various models. The top two figures show the results for 24 h (144 steps), and the bottom two figures show the prediction results for 48 h (288 steps).

As shown in Table 1, our proposed WPFGPT achieves the lowest RMSE and MAE values across both 24 h and 48 h prediction horizons, demonstrating its superior predictive performance compared to all baseline models. Specifically, WPFGPT reduces the average prediction error by approximately 9.5% at 24 h and 6.8% at 48 h compared to the best-performing baseline (MSSTGCN). This improvement highlights WPFGPT’s strong ability to capture complex spatio-temporal dependencies in wind power data. Unlike traditional sequence models such as GRU and LightGBM, WPFGPT leverages an LLM-based architecture combined with a spatio-temporal graph encoder, enabling it to model both temporal dynamics and spatial correlations among turbines effectively. Compared with current advanced deep learning models such as iTransformer and MSSTGCN, WPFGPT exhibits clear advantages in forecasting accuracy. While iTransformer captures temporal dependencies through attention mechanisms and MSSTGCN models spatial correlations via graph convolution, both approaches face limitations in jointly learning high-level semantic interactions between temporal and spatial dimensions. In contrast, WPFGPT introduces an LLM-based spatio-temporal fusion mechanism that aligns textual and numerical representations, enabling the model to reason over spatio-temporal contexts in a more expressive and interpretable manner. The lightweight alignment module effectively bridges the gap between spatio-temporal embeddings and LLM features, allowing WPFGPT to extract richer dependencies across turbines and time steps. Together, these innovations allow WPFGPT to learn richer representations of turbine interactions and temporal evolution patterns, leading to more accurate and robust wind power forecasts.

Furthermore, we conduct ablation experiments to demonstrate the role of the interpolation module. Table 2, using the prediction of wind power for the next 48 h as an example, illustrates the impact of the interpolation module on the model’s predictive performance.

Table 2.

Forecasting Results of Different Models with/without Interpolation. The bolded result indicates the best outcome. The green arrows indicate the enhancement achieved with interpolation.

As shown in Table 2, incorporating the frequency-domain interpolation module significantly improves the forecasting performance of all models. After interpolation, both RMSE and MAE consistently decrease across traditional models (LightGBM) and advanced deep learning models (GRU, iTransformer, MSSTGCN, etc.), indicating that the preprocessing step effectively mitigates the impact of missing and noisy data. The improvement trend is particularly evident in models that rely heavily on temporal or spatial dependencies, such as iTransformer and STGCN, where RMSE reductions exceed 3–4 kW. This demonstrates that the interpolation module enhances the continuity and smoothness of the input time series, allowing these models to learn stable patterns more effectively. WPFGPT benefits the most from the interpolation process, achieving the lowest RMSE (50.02 ± 0.51 kW) and MAE (37.92 ± 0.39 kW) among all models. This superior performance highlights the synergy between the interpolation-enhanced data quality and WPFGPT’s spatio-temporal reasoning capability, confirming that the proposed interpolation module not only improves data integrity but also strengthens downstream model generalization and forecasting reliability.

In order to explore the impact of graph construction methods on the final prediction results, this study conducted multiple experiments based on the proposed spatio-temporal graph neural network model, employing various graph construction methods and comparing their effects on prediction results. The graph adjacency matrices obtained from two kinds of fixed graph construction methods are illustrated in Figure 7. The experimental results in Table 3 clearly demonstrate the predictive performance variations associated with different graph construction methods.

Figure 7.

Adjacency Matrix with Different Graph Construction Methods (the left is geographical graph and the right is DTW graph). Both the horizontal and vertical axes represent the wind turbine number.

Table 3.

Forecasting Results with Different Graph Construction Methods. The bolded result indicates the best outcome.

In the task of forecasting the future 24 h of wind power, using the geographical distance matrix constructed based on the relative geographic positions of wind turbines achieved the best performance. However, in the task of forecasting the future 48 h of wind power, the method of using the dynamic learning graph module, which dynamically updates the graph structure throughout the learning process, yielded the best results. This indicates that, over a relatively short time span, the geographical distance construction method can better capture the spatial correlations between wind turbines, thus improving forecasting accuracy. In forecasting longer-term wind power tasks, due to the larger time span, the spatial correlations between wind turbines may change. Therefore, the dynamic learning graph module can better adapt to the data changes, thereby improving forecasting accuracy. These results also highlight the importance of selecting the appropriate graph construction method to enhance the performance of the model in different forecasting tasks.

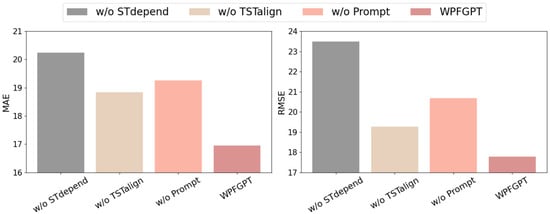

In order to investigate the impact of different key components on the performance of WPFGPT, we conducted ablation experiments on the Temporal Dependency Encoder module, the Text-Temporal Information Alignment module, and the Prompt Instruction Fine-Tuning module under the prediction duration setting of 24 h, and the results of the experiments are shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Ablation experiments on WPFGPT.

It can be seen that removing the spatio-temporal dependent encoder module, the text-spatio-temporal information alignment module, and the prompt instruction tuning module all lead to an increase in MAE and RMSE. The spatio-temporal dependent encoder module extracts a more comprehensive spatio-temporal pattern by recognizing and fusing complex relationships between different turbines using a graph convolutional network. The text-spatio-temporal information alignment module realizes the fusion of different modal information by aligning the textual information with the spatio-temporal information, activating the migration learning and inference ability of the backbone network. The prompt instruction tuning module provides more semantic details for the model by integrating rich temporal and spatial information as inputs to the prompt, improving the model’s adaptability to different spatio-temporal prediction scenarios, enabling it to predict wind power generation more accurately.

Figure 9 demonstrates that WPFGPT does not treat all data equally. It “looks” at specific locations based on the semantic instruction. This confirms the model’s ability to bridge the gap between natural language concepts and numerical sensor data. For example, in the row labeled “Turbine 3 Anomaly”, the attention weight for Turbine 3 is 0.99, while all other turbines are effectively 0.00. This shows that when the LLM prompts for a specific anomaly, the alignment module successfully isolates the target node, ignoring irrelevant noise from the rest of the wind farm. This transparency allows operators to verify that the model is diagnosing the correct device. The attention is distributed primarily among Turbines 11, 12, and 13 (scores of 0.17, 0.16, 0.14) in the row “North-East Cluster”. This indicates the model has learned the spatial topology of the farm and understands “North-East” not just as text, but as a specific subset of the graph structure.

Figure 9.

Visualization of attention weights in the text spatiotemporal alignment module.

As can be seen in Figure 10, as the prediction length rises, our model consistently has the lowest MAE and RMSE among all the models and maintains a significant advantage in both short-term and long-term spatio-temporal prediction, demonstrating the robustness of our proposed WPFGPT for the task of wind power prediction. This result can be attributed to the integration of the spatio-temporal dependence encoder with the prompt command fine-tuning. By combining these components, our model effectively captures generalized and transferable spatio-temporal patterns, enabling it to make accurate predictions.

Figure 10.

Variation in MAE and RMSE with prediction length.

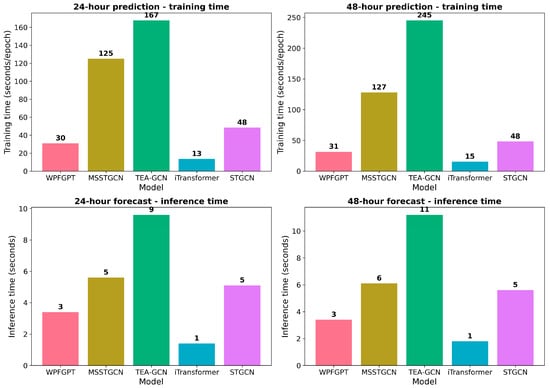

As shown in Figure 11, WPFGPT exhibits clear advantages in both training and inference efficiency for 24-h and 48-h wind power forecasting tasks. For training, WPFGPT requires approximately 30–31 s per epoch across both horizons, which is substantially lower than attention- and graph-intensive models such as MSSTGCN and TEA-GCN, whose training times exceed 120 s and increase dramatically to over 240 s for 48-h prediction. In contrast, WPFGPT shows only a marginal increase in training cost as the forecasting horizon extends, indicating good scalability. Although iTransformer achieves the shortest training time, WPFGPT provides a more balanced trade-off between computational efficiency and modeling capacity. Similar trends are observed in inference time: WPFGPT consistently maintains low latency (around 3 s) for both 24-h and 48-h forecasts, outperforming MSSTGCN, STGCN, and TEA-GCN, and remaining close to the fastest model, iTransformer. These results demonstrate that WPFGPT significantly reduces computational overhead while retaining strong predictive capability, making it well suited for large-scale and time-sensitive wind power forecasting applications.

Figure 11.

Comparison of training and inference times for different models (24 h vs. 48 h prediction).

5. Conclusions

In this study, we proposed WPFGPT, a large language model-driven spatiotemporal graph forecasting framework for wind power prediction at both turbine and wind farm levels. Experimental results demonstrate that WPFGPT consistently outperforms several baseline models in terms of forecasting accuracy. To address the widespread presence of anomalies and missing values in real-world wind power datasets, we further introduced a frequency-domain-based interpolation method for data reconstruction. Comparative experiments conducted on datasets before and after interpolation show that this preprocessing strategy effectively improves data quality and leads to more accurate power predictions. WPFGPT is capable of integrating heterogeneous data sources, including meteorological data, turbine operational data, and grid-related information. By leveraging large-scale pretraining, the proposed framework effectively captures complex spatiotemporal dependencies, encompassing both temporal dynamics and spatial interactions among turbines. This capability enables a more comprehensive understanding of wind power generation processes and contributes to more accurate and robust forecasting performance. Despite these promising results, this study has several limitations. First, the spatiotemporal dependency encoder can be further optimized to enhance the modeling of inter-turbine relationships and to improve the efficiency of message passing, particularly for large-scale wind farm networks. Second, the computational cost associated with integrating large language models may limit scalability in resource-constrained settings. Future work will therefore focus on improving model efficiency and exploring lightweight or adaptive architectures. In addition, we plan to extend WPFGPT to other renewable energy applications, such as solar power generation and energy storage systems, thereby broadening its applicability across the energy domain. We will collect and organize multiple datasets to verify and enhance the model’s generalization ability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.X. and A.S.; methodology, Z.X.; software, Y.K.; validation, Z.X. and Y.K.; investigation, Z.X. and A.S.; resources, Z.X. and Y.K.; data curation, Z.X. and Y.K.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.X. and Y.K.; writing—review and editing, Z.X., A.S. and Y.K.; visualization, Y.K.; supervision, Z.X. and A.S.; project administration, Z.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data has been described in the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zreik, M.; Jiao, Y. Comparative Econometric Analysis of Renewable Energy Policies in Smart Cities: A Case Study of Singapore and the UAE. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Wang, H.; Wang, D.; Liu, D.; Sun, K. A Review of Wind Power Prediction Methods Based on Multi-Time Scales. Energies (19961073) 2025, 18, 1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, Q.T.; Wu, Y.K.; Phan, Q.D. A hybrid wind power forecasting model with XGBoost, data preprocessing considering different NWPs. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Focken, U.; Lange, M.; Waldl, H.P. Previento: A Wind Power Prediction System with an Innovative Upscaling Algorithm. In Proceedings of the European Wind Energy Conference, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2–6 July 2001. [Google Scholar]

- First, U.; Engin, S.N.; Saraclar, M.; Ertuzun, A.B. Wind Speed Forecasting based on Second Order Blind Identification and Autoregressive Model. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning and Applications, Washington, DC, USA, 12–14 December 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Yunus, K.; Thiringer, T.; Chen, P. ARIMA-Based Frequency-Decomposed Modeling of Wind Speed Time Series. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2016, 31, 2546–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Sun, J.; Zhang, H. Short-term Wind Power Forecasting based on Support Vector Machine. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Power Electronics Systems and Applications, Hong Kong, China, 11–13 December 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Wen, H.; Lou, J.; Fu, J.; Zheng, J.; Lin, Y. EasyST: Modeling Spatial-Temporal Correlations and Uncertainty for Dynamic Wind Power Forecasting via PaddlePaddle. In Baidu KDD Cup; Renmin University of China: Beijing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, H.; Dong, Z.; Chen, Y.; Ge, J.; Lai, L.L.; Vaccaro, A.; Meng, A. An Effective Secondary Decomposition Approach for Wind Power Forecasting using Extreme Learning Machine Trained by Crisscross Optimization. Energy Convers. Manag. 2017, 150, 108–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.; Yue, H. Application of BERT in Wind Power Forecasting-Teletraan’s Solution. In Baidu KDD Cup; Renmin University of China: Beijing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; Xu, J.; Wang, J.; Long, M. Autoformer: Decomposition Transformers with Auto-Correlation for Long-Term Series Forecasting. In Proceedings of the Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Online, 6–14 December 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, T.; Ma, Z.; Wen, Q.; Wang, X.; Sun, L.; Jin, R. FEDformer: Frequency Enhanced Decomposed Transformer for Long-term Series Forecasting. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Baltimore, MD, USA, 17–23 July 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, X.; Gu, Q.; Qiao, S.; Lv, Z.; Song, X. WPFormer: A Spatio-Temporal Graph Transformer with Auto-Correlation for Wind Power Prediction. In Baidu KDD Cup; Renmin University of China: Beijing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Yu, H.; Liao, C.; Li, J.; Lin, W.; Liu, A.X.; Dustdar, S. Pyraformer: Low-complexity Pyramidal Attention for Long-range Time Series Modeling and Forecasting. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, Vienna, Austria, 3–7 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, R.; Wang, Z.; Jie, J.; Wang, W.; Ye, Q. VTformer: A novel multiscale linear transformer forecaster with variate-temporal dependency for multivariate time series. Complex Intell. Syst. 2025, 11, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Hu, T.; Zhang, H.; Wu, H.; Wang, S.; Ma, L.; Long, M. Itransformer: Inverted transformers are effective for time series forecasting. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.06625. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Ai, Q.; Xiao, F.; Hao, R.; Lu, T. Typical Wind Power Scenario Generation for Multiple Wind Farms using Conditional Improved Wasserstein Generative Adversarial Network. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2020, 114, 105388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, R.; Wang, B.; Mao, Z.; Watada, J. Multi-objective Wind Power Scenario Forecasting based on PG-GAN. Energy 2021, 226, 120379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xing, J.; Wu, S. A Spatial-temporal Ensemble Deep Learning Framework for Wind Power Forecasting (Team QDU). In Baidu KDD Cup; Renmin University of China: Beijing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, J.; Han, C.; Wang, J. Spatial-Temporal Graph Neural Network for Wind Power Forecasting in Baidu KDD CUP 2022. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.11159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Pan, S.; Long, G.; Jiang, J.; Chang, X.; Zhang, C. Connecting the Dots: Multivariate Time Series Forecasting with Graph Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 26th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Virtual, 6–10 July 2020; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, J.; Liu, Z.; Du, B.; Sun, L.; Li, W.; Fu, Y.; Xiong, H. Learning the Evolutionary and Multi-scale Graph Structure for Multivariate Time Series Forecasting. In Proceedings of the 28th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Washington, DC, USA, 14–18 August 2022; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Zhu, Z. Spatial-temporal Fusion Graph Neural Networks for Traffic Flow Forecasting. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Virtually, 2–9 February 2021; Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lan, S.; Ma, Y.; Huang, W.; Wang, W.; Yang, H.; Li, P. DSTAGNN: Dynamic Spatial-temporal Aware Graph Neural Network for Traffic Flow Forecasting. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Baltimore, MD, USA, 17–23 July 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, X.; Sun, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Pu, T. Spatio-temporal Convolutional Network Based Power Forecasting of Multiple Wind Farms. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2022, 10, 388–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Zhang, W.; Li, X.; Zhang, X. Tea-gcn: Transformer-enhanced adaptive graph convolutional network for traffic flow forecasting. Sensors 2024, 24, 7086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zong, X.; Yu, F.; Chen, Z.; Xia, X. MSSTGCN: Multi-Head Self-Attention and Spatial-Temporal Graph Convolutional Network for Multi-Scale Traffic Flow Prediction. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2025, 82, 3517. [Google Scholar]

- Kipf, T.N.; Welling, M. Semi-Supervised Classification with Graph Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, Toulon, France, 24–26 April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Muda, L.; Begam, M.; Elamvazuthi, I. Voice Recognition Algorithms using Mel Frequency Cepstral Coefficient (MFCC) and Dynamic Time Warping (DTW) Techniques. arXiv 2010, arXiv:1003.4083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, A.; Chen, M.; Zhang, L.; Xu, Q. Are Transformers Effective for Time Series Forecasting? In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 25 February–4 March 2025; Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Dubey, A.; Jauhri, A.; Pandey, A.; Kadian, A.; Al-Dahle, A.; Letman, A.; Mathur, A.; Schelten, A.; Yang, A.; Fan, A.; et al. The llama 3 herd of models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.21783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Hu, T.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, H.; Wang, J.; Long, M. TimesNet: Temporal 2D-Variation Modeling for General Time Series Analysis. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, Kigali, Rwanda, 1–5 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Lu, X.; Xiao, Y.; Su, J.; Lyu, J.; Ma, Y.; Dou, D. Sdwpf: A dataset for spatial dynamic wind power forecasting challenge at kdd cup 2022. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2208.04360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.; Van Merriënboer, B.; Gulcehre, C.; Bahdanau, D.; Bougares, F.; Schwenk, H.; Bengio, Y. Learning Phrase Representations using RNN Encoder-Decoder for Statistical Machine Translation. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1406.1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, G.; Meng, Q.; Finley, T.; Wang, T.; Chen, W.; Ma, W.; Ye, Q.; Liu, T.Y. LightGBM: A Highly Efficient Gradient Boosting Decision Tree. In Proceedings of the 31st Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS 2017), Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, B.; Yin, H.; Zhu, Z. Spatio-Temporal Graph Convolutional Networks: A Deep Learning Framework for Traffic Forecasting. In Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Stockholm, Sweden, 13–19 July 2018. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.