Abstract

The model of a liquid desiccant dehumidification air conditioning (LDAC) system is one of the key foundations for achieving efficient cooling, dehumidification and regeneration, and saving energy consumption. The data-driven modeling method does not need to understand the complex heat and mass transfer mechanism and equipment physical information, thus the modeling complexity is greatly reduced. This paper proposes a temperature and humidity prediction model integrating the Black Kite Algorithm (BKA), Bidirectional Temporal Convolutional Network (BiTCN), Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM), and Self-Attention mechanism (SA). The model extracts local spatiotemporal features from sequence data through BiTCN, enhances the understanding of contextual dependencies in temporal data using BiLSTM, and employs the SA to assign dynamic weights to different time steps. Furthermore, BKA is adopted to optimize the hyperparameter combinations of the neural network, thereby improving prediction accuracy. To validate the model performance, an experimental platform for an LDAC system was established to collect operational data under multiple working conditions, constructing a comprehensive dataset for simulation analysis. Experimental results demonstrate that compared to conventional time-series prediction models, the proposed model achieves higher accuracy in predicting outlet temperature and humidity across various operating conditions, providing reliable technical support for system real-time control and performance optimization.

1. Introduction

Energy consumption has always been one of the issues of global concern. According to statistics, 40% of global energy is consumed by the building industry [1]. The largest proportion of building energy is taken up by heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems, accounting for up to 38% of the total, with residential consumption accounting for 32% and tertiary industry accounting for 47% of this [2,3]. In HVAC system applications, most energy consumption is asociated with the air cooling and dehumidification process [4]. Therefore, to achieve more energy savings, it is crucial to reduce the energy consumption of the air cooling and dehumidification process. The LDAC system has emerged as an effective alternative to traditional air-conditioning systems in the air dehumidification field. Using this method, the moisture air does not need be cooled below the dew point for dehumidification, but instead the water absorption capacity of a desiccant solution is used, thereby saving energy. Although the LDAC system’s energy efficiency is better than that of a traditional air conditioning system, its energy consumption could still be significantly improved. In order to achieve accurate and efficient control of an LDAC system, it is particularly important to develop a more accurate system temperature and humidity prediction model.

At present, LDAC system models are mainly divided into four categories as follows: the number of transfer units model (NTU model), the finite difference model, the empirical model, and the data-driven model [5]. In theoretical analysis, due to its accuracy, the finite difference model is more frequently used for heat and mass transfer process study. Factor and Grossman [6] constructed and simplified a packed-bed dehumidifier/regenerator model under several reasonable assumptions to analyze the performance of the equipment. The model calculation results were consistent with the experimental results. Wang et al. [7] proposed a coefficient formula for heat and mass transfer and a dynamic finite difference model for liquid dehumidifier mixed air conditioning systems which have been verified under different test environments. However, the finite difference model is not suitable for industrial applications due to the detailed fluid physical properties and system structure information which are required during the modeling process, which may not be available in practice. Furthermore, to solve the model, high-burden iterative computation is required. The finite difference model is also discussed in [8,9].

For -NTU models, Ren et al. [10] proposed some analytical expressions which were obtained from certain perturbation techniques to modify the liquid dehumidifier–air contact exchanger model. Stevens et al. [11] derived a liquid dehumidifier model based on an efficiency model of a cooling tower [12]. The model calculations were in good agreement with the experimental data and the finite difference model. Moreover, Shen et al. [13] and Zhang et al. [14] used similar models in their studies. In spite of the computational burden, the -NTU model is reduced compared with the finite difference model, but detailed system geometry information and iterative calculations are also required. For empirical models, Khan [15] proposed two fitted algebraic equations for a packed-bed LDDS system to obtain the air humidity and temperature, and conducted an in-depth analysis of the air dehumidification process. To predict performance of the regenerator, a regression mode was established by Yang et al. [16]. The empirical model was also used in [17]. The empirical model has the advantages of simplicity and low computational complexity, but its scalability is low because the model parameters are determined by the system operating data under certain working conditions. In addition, the empirical model is also considered in [18,19].

In recent years, data-driven modeling methods have become popular in the field of complex system modeling due to their simplicity and flexibility [20]. These methods use historical data to deduce the relationship between input and output, with no need for complex heat and mass transfer equations and related physical information, which greatly reduces the complexity of modeling [21]. In the field of time-series prediction, artificial neural networks (ANNs), long short-term memory networks (LSTMs), and hybrid models of convolutional neural networks and LSTM (CNN-LSTMs) have become mainstream frameworks. These models have demonstrated their ability to handle time-series data in building energy scenarios such as load forecasting [22,23] and indoor temperature control [24,25,26,27]. However, when these general models are directly applied to the LDAC system, due to the unique dynamic characteristics of the LDAC system, such as the strong coupling of the dehumidification and regeneration process and the interweaving of heat and mass transfer at multiple time-scales, their limitations gradually emerge. Specifically, in the air cooling and dehumidification and desiccant regeneration processes, changes in the desiccant solution’s concentration and fluctuations in air temperature and humidity simultaneously involve rapid transients at the second/minute level and slow gradients at the hour level. While traditional serial hybrid models (e.g., CNN-LSTMs) can capture certain temporal features, their cascaded architecture inherently acts as a sequential feature processor. Features extracted by the front-end network can have their physical significance across different time-scales confused or diluted when passed to the back-end network, making it difficult to explicitly and synergistically model the interaction between “fast” and “slow” dynamic processes. This limitation undermines prediction accuracy and generalization capability during highly dynamic operational phases, such as system start-up, shutdown, or mode transitions.

Data-driven modeling for LDAC systems has undergone preliminary exploration, but existing methods still have some limitations in addressing the system’s multi-time-scale dynamic characteristics. Gandhidasan and Mohandes used a multi-layer ANN to construct a system model in [28], and they examined the system operating performance using the developed model in depth. Mohammad et al. [29] established an ANN model to predict the efficiency of dehumidifiers and the water condensation rate. The model uses two different hidden layers. By comparing the predicted dehumidifier performance data with the experimental data, the relative errors were found not to exceed 10%. Zeidan et al. [30] used a multi-layer ANN structure to describe the solar desiccant cooling system operating performance. Bhowmik et al. [31] proposed an artificial intelligence-based GEP-MOPSO model to predict the efficiency of LDDS. The model employs both the sensible heat factor and mass transfer rate as performance indicators. In summary, existing studies predominantly rely on relatively singular model architectures. They fail to explicitly handle the interwoven fast and slow multi-time-scale dynamic processes inherent in LDAC systems, lack an adaptive focusing mechanism for critical operational states, and typically depend on empirical settings for model hyperparameters. In this paper, the studied LDAC system involves two-stage mass and heat transfer processes, and the structure is more complex; in particular, the air flow path in the regeneration system is self-intersecting. If the mechanism model is adopted, when calculating the regenerator outlet air temperature, it is necessary to obtain the regenerator inlet air temperature through iterative calculation. In addition, the air cooling and dehumidification and desiccant solution regeneration processes have strong coupling and hysteresis, which poses a huge challenge to the establishment of a real-time system prediction model. Therefore, it is very necessary to select a suitable and accurate modeling method.

To overcome the aforementioned limitations, a BKA-BiTCN-BiLSTM-SA prediction framework is designed for multi-time-scale dynamic decoupling and attention-based fusion, rather than simply integrating existing modules. The main contributions lie in the collaborative design across the following three levels:

- Parallel Multi-Scale Feature Extraction Architecture: In contrast to serial hybrid architectures such as CNN-LSTM, this study adopts a parallel dual-path design: a bidirectional temporal convolutional network (BiTCN) is dedicated to extracting high-frequency local features at the second-to-minute level, while a bidirectional long short-term memory network (BiLSTM) focuses on modeling low-frequency long-term trends at the hour level. This parallel structure fundamentally avoids the confusion of multi-scale features during sequential transmission, thereby achieving more efficient feature encoding for the LDAC system.

- Data-Driven Dynamic Feature Fusion Mechanism: By introducing a self-attention mechanism as the core fusion layer, adaptive weight allocation is achieved. This mechanism dynamically evaluates and fuses features from the dual paths, automatically enhancing the focus on features relevant to critical system states while suppressing interference from irrelevant information. This transforms the model from traditional “static feature concatenation” to “dynamic importance-weighted fusion,” significantly improving prediction accuracy under non-stationary operating conditions.

- Targeted Optimization Strategy for High-Dimensional Hyperparameter Space: To address the challenge of numerous hyperparameters in this complex framework and the difficulty of manual tuning, the Black-winged Kite Algorithm (BKA) is employed for adaptive and efficient search, ensuring that the model approaches its theoretically optimal performance.

In this paper, a novel hybrid neural network architecture specifically is designed for the multi-time-scale dynamic characteristics of LDAC systems. Through the synergy of parallel-division feature extraction, dynamic attention-based fusion, and intelligent hyperparameter optimization, this architecture systematically addresses the shortcomings of existing models in capturing the fast–slow intertwined dynamics of the LDAC system. Validation on an LDAC experimental platform demonstrates that the proposed BKA-BiTCN-BiLSTM-SA model achieves optimal accuracy in predicting the system outlet air temperature and humidity, laying the foundation for its application in real-time optimal control.

2. Working Principles

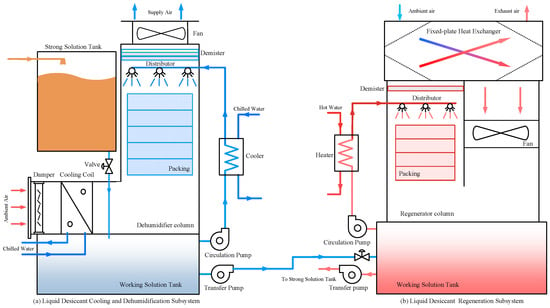

The LDAC system consists of two independently operable subsystems, namely, the liquid desiccant cooling and dehumidification subsystem (LDCDS) and the liquid desiccant regeneration subsystem (LDRS). Figure 1 shows the system schematic diagram. The LDCDS is applied to reduce the temperature and humidity of the moisture air, and mainly comprises a cooler, dehumidifier, cooling coil, pumps, and fan; the LDRS is applid to concentrate a dilute desiccant solution, restore dehumidification capacity, and mainly comprises a fixed-plate heat exchanger, a regenerator, a heater, fan, and pumps.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the LDAC system.

In the LDCDS, the moisture air is driven by the fan and enters the cooling coil, where it reacts with the chilled water in the coil. The heat is transferred from the moisture air into chilled water, the air temperature decreases, and the humidity reaches saturation gradually. As the heat transfer process continues, the moisture in the air is condensed and precipitated. Then, the cooled and dried air enters the dehumidifier. The concentrated desiccant solution is driven by a solution pump and cooled in a cooler. Both the temperature and surface water vapor partial pressure are reduced, and the cooling and dehumidification capacity are enhanced. Subsequently, the desiccant solution enters a dehumidifier and is sprayed on the packing surface through the distributor device. The air passes through the dehumidifier from bottom to top; the heat and mass transfer process occurs when the air contacts the desiccant solution. Due to the difference in the surface water vapor partial pressure and the temperature between the air and the desiccant solution, the heat and mass are transferred from the air into the desiccant solution, the air temperature and humidity decrease, while the desiccant solution is heated and diluted. As the dehumidification process continues, the desiccant solution’s dehumidification capacity is reduced; it is necessary to regenerate it in the liquid desiccant regeneration subsystem.

In the LDRS, the outdoor air is driven by a fan into a fixed-plate heat exchanger, where it undergoes a heat exchange reaction with the exhausted air, the temperature increases, and the air then enters the regenerator. The dilute desiccant solution is driven by a solution pump and first enters a heater, where it is heated by the hot fluid, and as a result, the solution surface water vapor partial pressure increases. Then, the heated desiccant solution enters the regenerator and sprays on the packing surface from top to bottom. The heated air enters the regenerator from bottom to top and contacts the desiccant solution. Since the desiccant solution’s temperature and surface water vapor partial pressure are both greater than air, the transfer direction of heat and moisture is opposite to that in the dehumidifier, from the desiccant solution into the air, and the concentration of the desiccant solution increases. After the regenerator, the hot air enters a fixed-plate heat exchanger, where it heats the incoming outdoor air to reduce the heat transfer in the regenerator, thus reducing energy consumption. The concentrated desiccant solution is driven into the strong solution tank, and then enters the dehumidifier again, so as to achieve recycling of the desiccant solution in the LDAC system.

3. BKA-BiTCN-BiLSTM-SA Prediction Model

3.1. Bidirectional Temporal Convolutional Neural Network

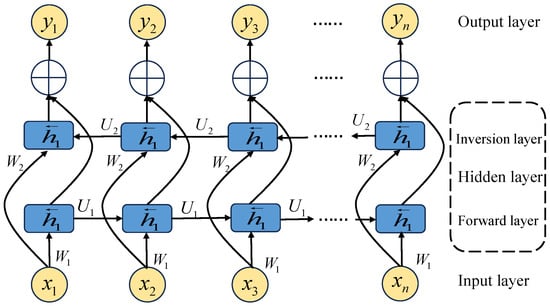

The Bidirectional Temporal Convolutional Network (BiTCN) is evolved from the conventional Temporal Convolutional Network (TCN). By incorporating structures such as causal convolutions, residual blocks, and dilated causal convolutions, the TCN can effectively process time-series data and addresses the limitations of recurrent neural networks in gradient propagation and learning long-term dependencies [32,33]. However, when handling time-series data from LDAC systems, the TCN only utilizes forward sequential information and fails to adequately extract contextual features from the reverse direction. To overcome this, the present study adopts the BiTCN architecture, which simultaneously performs forward and backward convolution operations to integrate bidirectional latent features [34]. This enables more accurate modeling of the long-term dependencies in the outlet temperature and humidity sequences and enhances the comprehensive representational capacity for the overall time series, as illustrated in Figure 2. The network employs dilated causal convolutions with exponentially increasing dilation rates across layers; the mechanism is shown in Figure 3. This design effectively expands the receptive field without significantly increasing the network depth, thereby capturing broader temporal dependencies. It also mitigates issues commonly associated with conventional sequence models, such as low efficiency in learning long-term dependencies, high computational costs, and limited utilization of future information [35].

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of BiTCN.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of dilated causal convolution.

During the air dehumidification and desiccant regeneration processes, an inherent time lag and non-steady-state behavior exist between the dynamic variation of the inlet air parameters and the corresponding outlet responses. To accurately characterize such transient dynamics, this study introduces a BiTCN module. By constructing a multi-scale dilated convolutional structure, the module enables the model to acquire multi-resolution temporal perception ranging from seconds to minutes. In this design, each dilation coefficient corresponds to a different temporal receptive field, which effectively captures periodic temperature fluctuations. Such a structure allows the model to learn the dynamic response patterns of the system at varying time-scales and align them with the time constants of the actual physical processes, thereby enhancing the modeling accuracy and generalization capability for both transient and steady-state behaviors of the LDAC system.

3.2. Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory

A Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network is a type of recurrent neural network specifically designed for processing time-series data. By introducing a gating mechanism, it effectively addresses the vanishing or exploding gradient problems commonly encountered in traditional RNNs during the training of long sequences [36]. The core of an LSTM lies in its cell state and three gating structures (forget gate, input gate, and output gate), enabling it to selectively remember or forget information, thereby capturing long-term dependencies in time series. Figure 4 shows the topological structure of an LSTM network. The computational process can be described by the following formulas:

where represents the Sigmoid function, is the state of the hidden layer unit, represents the state of the intermediate unit, and , , , and represent the bias values of the input gate, forgetting gate, intermediate unit state and output gate, respectively. , , , and represent the weight values of the input gate, forgetting gate, intermediate unit state, and output gate, respectively.

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of LSTM.

The traditional LSTM only performs forward encoding based on historical information and cannot utilize contextual information from future time steps. To address the characteristics of the outlet temperature and humidity changes in liquid desiccant air conditioning systems, which are influenced by both historical states and implied future trends, this study employs a Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory network (BiLSTM). BiLSTM captures the dependencies in the time series from both past and future directions simultaneously by operating both a forward and a backward LSTM layer. Its computational process is as follows:

where and represent the forward output and reverse output of the LSTM network, respectively, and represent the input layer weight matrix of the forward propagation and backward propagation, respectively, and represent the hidden layer weight matrix, , , and represent the bias vector; is the final output value. Figure 5 depicts the computation structure of the BiLSTM network.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of BiLSTM.

The operation of LDAC systems is significantly influenced by long-term trends, such as ambient temperature and humidity fluctuations, as well as the gradual evolution of the solution concentration. To model this trend-related dependency spanning from tens of minutes to hours, a BiLSTM module is introduced. In its implementation, the forward LSTM captures and encodes the cumulative effect of historical operating conditions on the current state, such as the concentration change due to continuous moisture absorption by the solution, while the backward LSTM provides contextual constraints for the current prediction by incorporating short-term future trends. This bidirectional modeling mechanism substantially enhances the state representation capability of the system during mode transitions, enabling more accurate characterization of the dynamic changes in outlet temperature and humidity over time-scales ranging from tens of minutes to hours.

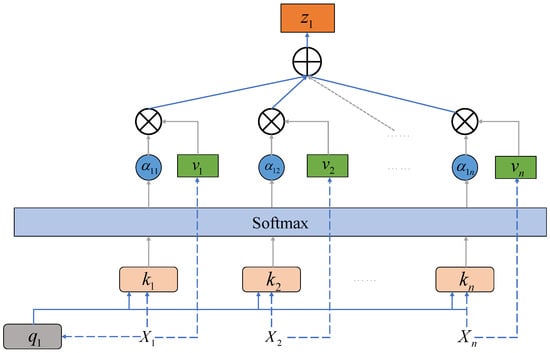

3.3. Self-Attention Mechanism Module

The self-attention (SA) mechanism is a network structure that dynamically assigns weights to focus on key information by calculating the correlations between elements within a sequence. Its core lies in the model’s ability to autonomously assess the relationships between any two positions in the input sequence and assign higher attention weights to more important information, without relying on fixed windows or external alignments. In this study, this mechanism is applied after the fusion of high-level features extracted by BiTCN and BiLSTM, aiming to enhance the model’s ability to capture and utilize key dynamic segments in the time-series data of the LDAC system. The schematic diagram of its network structure is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram of self-attention mechanism.

Specifically, given the feature sequence output from the previous module, the self-attention mechanism maps it into three matrices: query, key, and value. The attention scores are then calculated using the scaled dot-product, with the core computational process expressed by the following formula:

where q, k, and v are the query vector, key vector, and value vector, respectively. By calculating the dot product of k and q, the importance of each query element to all key elements in the self-attention mechanism is determined, and then the result is divided by .

In an LDAC system, the contribution of variables at different time steps to the current prediction is not a constant. For instance, features associated with the moment of regenerator start-up or when the solution concentration reaches a critical point are more significant than those during steady-state operation. Therefore, this study introduces a self-attention (SA) mechanism after feature fusion in BiTCN and BiLSTM. The specific role of the SA mechanism is to achieve operational-condition-adaptive dynamic feature weighting: during model training, the SA mechanism automatically learns and assigns higher attention weights to features at key time steps, such as operational mode transitions and sudden parameter changes. This enables the model to focus on the most relevant historical states during prediction, thereby enhancing the robustness and interpretability of predictions under non-stationary operating conditions.

3.4. BKA Optimization Algorithm

The Black-winged Kite Algorithm (BKA) is a swarm intelligence optimization algorithm that models the predatory and migratory behaviors of black-winged kites [37]. It mathematically formulates the adaptive mechanisms and cooperative decision-making processes observed in dynamic environments, endowing the algorithm with efficient global search capabilities. Its core principles are outlined below.

In the initialization phase of the BKA, the population is initialized by generating a set of random solution vectors. Within the mathematical formulation of the algorithm, the spatial position of each BK individual can be characterized by the following matrix representation:

where denotes the number of potential solutions, indicates the size of the problem dimension, and represents the i-th dimension of the j-th BK. The initial position assigned to each BK is calculated as follows:

where denotes the solution vector of the i-th BK individual (where ), and and represent the lower and upper bound vectors, respectively.

The BK employs two typical aerial predation strategies: a stationary hovering strategy for global exploration and a dynamic cruising strategy for local fine-grained search. These strategies form a spatially complementary cooperative search mechanism during predation. When diving from high altitude to attack, its neural regulation system dynamically adjusts the movement intensity to balance energy expenditure and strike accuracy, a process modeled by an exponential decay factor over the attack duration (Equation (14)). The transition between these two attack-behavioral modes is governed by a stochastic threshold (Equation (15)).

where t denotes the current iteration number, T represents the maximum iteration count, and and indicate the positional coordinates at iterations t and , respectively. The parameter r is a stochastic disturbance factor following a uniform distribution , while p serves as a behavior-switching threshold with a fixed value of 0.9.

The migration behavior of BKA incorporates a dynamic leadership mechanism. If a randomly selected candidate individual demonstrates superior fitness to the current leader, the incumbent leader integrates into the population to prevent the algorithm from converging to local optima; otherwise, it continues to guide the population. This strategy of dynamically transferring leadership based on fitness comparison effectively balances the algorithm’s global exploration and local exploitation capabilities, as formulated in the following mathematical model:

where m represents a dynamic adjustment factor generated by a sine function to control the migration step size. denotes the positional coordinate of the current optimal leader. and indicate the fitness values of the current individual and a randomly selected individual, reflecting migration performance and leadership competition, respectively. refers to a standard Cauchy-distributed random number, which introduces long-tailed disturbances to enhance global search capability.

The BiTCN-BiLSTM-SA hybrid model constructed in this study involves multiple critical hyperparameters, such as the learning rate, the number of hidden neurons, the key and value dimensions of the self-attention mechanism, and regularization parameters, forming a high-dimensional, non-convex optimization challenge. Traditional grid search methods are inefficient in computationally expensive scenarios like LDAC applications. This study employs the Black-winged Kite Algorithm (BKA) for hyperparameter optimization, with its adaptability demonstrated in the following aspects: (1) Tailored Parameter Space Definition: Based on the scale and characteristics of LDAC data, the search space is constrained to avoid exploration of irrelevant regions; (2) Efficient Convergence: Leveraging the parallel search capability of BKA, the algorithm stabilizes within approximately 50 generations to identify the parameter combination that minimizes validation loss. This significantly reduces the time cost of model tuning, making the parameter calibration process of the hybrid model efficient and feasible for deployment in practical LDAC systems.

3.5. BKA-BiTCN-BiLSTM-SA Model

To address the multi-time-scale and strongly dynamic-coupled data characteristics of the LDAC system, this study constructs a BKA-BiTCN-BiLSTM-SA hybrid prediction model. Through the synergistic design of its components, the model achieves precise modeling of the “fast--slow” intertwined dynamics. At the feature extraction level, the model employs a parallel dual-path structure comprising BiTCN and BiLSTM to separate multi-scale features from the source. Leveraging its bidirectional dilated convolutions, BiTCN specializes in capturing second-to-minute-level local high-frequency fluctuations. BiLSTM, utilizing its bidirectional gating mechanism, effectively models hour-level long-term trends and dependencies. At the feature fusion level, an SA mechanism is introduced as the core scheduler. The SA mechanism dynamically integrates feature representations from the dual paths. It can adaptively balance short-term and long-term information during steady-state system operation, and automatically enhance focus on high-frequency features (from BiTCN) during critical transients, thereby achieving sensitive responsiveness to changes in operational states. The BKA algorithm is adopted to address the difficulty of manual hyperparameter tuning. BKA efficiently searches for key parameters such as network depth, learning rate, and attention dimensions, ensuring the model’s performance approaches the optimum and enhancing the method’s reproducibility and robustness.

The overall design logic of this architecture is illustrated in Figure 7. Its core advantage lies in the systematic enhancement of the model’s capability to characterize the complex dynamics of the LDAC system and its prediction accuracy, achieved through parallel-division feature encoding, dynamically weighted feature fusion, and intelligent parameter optimization.

Figure 7.

Schematic diagram of BKA-BiTCN-BiLSTM-SA.

The prediction flowchart of the BKA-BiTCN-BiLSTM-SA temperature and humidity prediction model is shown in Figure 8. It mainly contains four steps: outlier and missing data processing, data burr removal, data normalization, model training and testing. The steps are given in detail as:

Figure 8.

Prediction flowchart of BKA-BiTCN-BiLSTM-SA prediction model.

- Outlier and missing data processingThe original operating data of the LDAC system usually contain outliers and missing data reflecting acquisition equipment failure or signal transmission interruption. In the process of data processing, a linear interpolation method is adopted to detect the outliers in the dataset, delete the abnormal data after detecting the outliers, and estimate the missing values through the linear relationship between the known data points.

- Data burr removalDuring the operation of the LDAC system, changes in equipment structure and airflow velocity can affect the distribution of air, leading to numerous spikes in the data measured by the sensors. To eliminate high-frequency sensor noise and transient glitches generated during data acquisition, this study applied a centered moving average filter with a window width of 5 to the raw data. This method takes the current data point as the center, selects the two adjacent points before and after it, and calculates the arithmetic mean of these five points as the smoothed value for the current point.

- Data normalizationIn order to eliminate the influence of measurement units and value ranges between different features and increase the network’s convergence, the sample data are normalized. In the experiment, the sample data are scaled into [0,1], and the normalization formula for each feature input is given as follows:where and are the maximum and minimum value in sample data x, respectively, and is the normalized value after data normalization.

- Model training and testing(1) The dataset is partitioned into training and testing subsets, followed by data normalization. (2) The BKA algorithm performs hyperparameter optimization by defining the search boundaries for each hyperparameter, initializing the population size, and setting the maximum iteration count. (3) The fitness function of the BKA algorithm is computed, and the optimal individual position of the black-winged kite is identified based on its search principles. (4) The optimal parameter combination is incorporated into the BiTCN-BiLSTM-SA model to generate predictions, after which the output results are reverse-normalized.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Experimental Data and Network Parameters

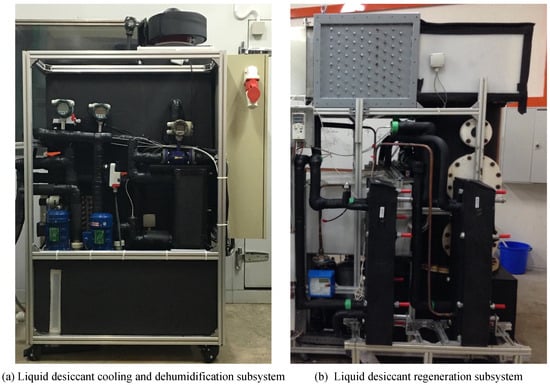

The LDAC system is divided into two independently operated subsystems, namely, the LDCDS and LDRS; the experimental platform is exhibited in Figure 9. The experimental platform mainly includes cooling coils, a dehumidifier, regenerator, fixed-plate heat exchanger, data acquisition and control system and other major components, and a lithium chloride solution is adopted as the desiccant solution. According to the discussion of the influence of the LDAC system inlet parameters on the cooling, dehumidification, and regeneration performance, it is found that the key parameters affecting the system chilled water temperature and air temperature and humidity are not the same. Therefore, the outlet chilled water temperature and the air temperature and humidity of the system are predicted separately [38]. The chosen input variables of the chilled water temperature and air temperature and humidity prediction models for the LDCDS and LDRS are summarized in Table 1. The measured values of each variable are collected by a data acquisition system, and the specifications of the different sensors are listed in Table 2. The experimental operating range of the working fluids in the LDAC system is summarised in Table 3.

Figure 9.

Experimental platform of the LDAC system.

Table 1.

Input variables of the chilled water temperature and air temperature and humidity prediction models.

Table 2.

Specifications of the different sensors.

Table 3.

Experimental operating range of the working fluids.

For the air temperature and humidity and chilled water prediction models of the liquid desiccant cooling and dehumidification subsystem, a total of 3268 sets of sample data, with an interval of 10 s between each set, were measured and collected from the experimental platform. The training set and testing set were divided by 8:2. For the air temperature and humidity prediction models of the liquid desiccant regeneration subsystem, a total of 4334 sets of sample data with an interval of 3 s were collected. The training set and testing set were divided by 7:3. All datasets were strictly split in chronological order to prevent information leakage. The computer parameters used for running the simulation program are as follows: Windows 11 operating system, Intel(R) Core(TM) Ultra 5 125H 3.60 GHz, 32 GB RAM; the running software is Matlab R2023b.

Before network training, the parameters of the BKA-BiTCN-BiLSTM-SA model were configured. The model employs the Adam optimizer and the ReLU activation function. Regarding the network architecture, the convolutional kernel size is set to 5 with 64 filters. To prevent overfitting, the Dropout rate is set to 0.1, and the maximum number of training epochs is 50. Input data sequences are constructed using a sliding window method, with a window length of 8 timesteps and a stride of 1, allowing for overlap between adjacent windows. The model’s hyperparameters, including the learning rate, the number of neurons in the BiLSTM hidden layer, the key dimensions of the self-attention mechanism, and the regularization coefficient, are all automatically optimized using the Black-winged Kite Algorithm. The initial population size for BKA is set to 10, with a maximum of 50 iterations, and the objective is to minimize the MPAE. Ultimately, a dedicated prediction model is independently trained for each target output variable. The optimal parameters identified by the BKA for the LDAC temperature and humidity model are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Optimal parameter settings of the BiTCN-BiLSTM-SA prediction models.

4.2. Model Validation

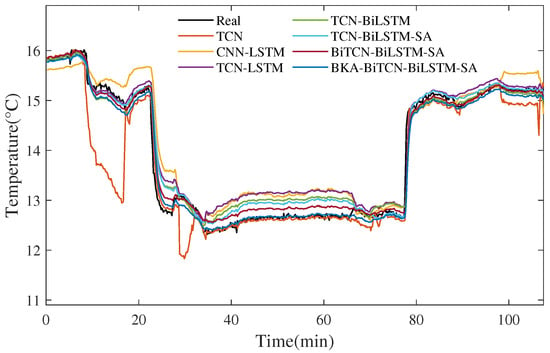

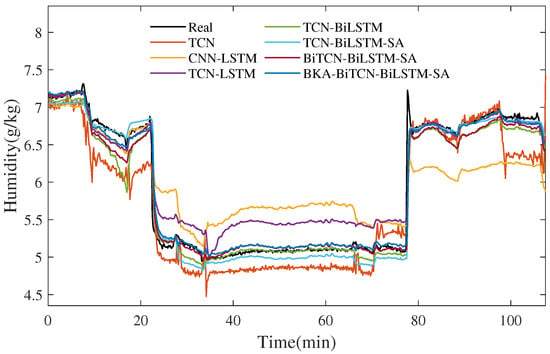

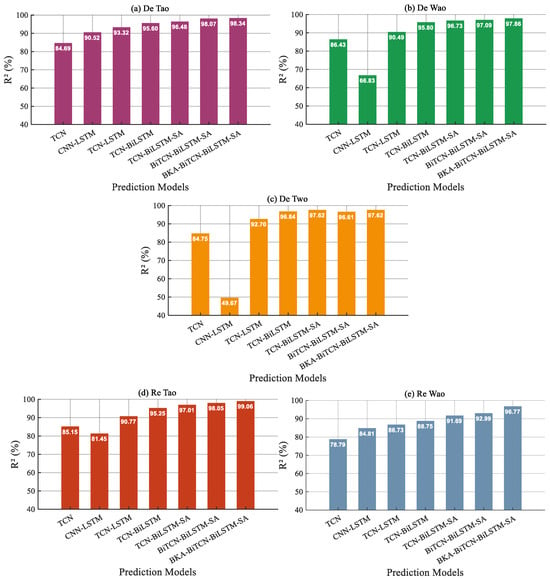

To verify the effectiveness of the proposed model, the TCN, CNN-LSTM, TCN-LSTM, TCN-BiLSTM, TCN-BiLSTM-SA, BiTCN-BiLSTM-SA and the proposed BKA-BiTCN-BiLSTM-SA model were verified and compared in the datasets of the LDCDS and LDRS. The error criteria, such as the mean absolute error (MAE), mean square error (MSE), root mean square error (RMSE), mean absolute percentage error (MAPE), and determination coefficient (), were adopted. The air temperature and humidity and chilled water temperature prediction curves of the LDCDS by different prediction models are depicted in Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12. The air temperature and humidity prediction curves of the LDRS by different prediction models are given in Figure 13 and Figure 14. Figure 15 intuitively compares the performance of different prediction models. The validation errors of the air temperature and humidity prediction models of the two subsystems are summarized in Table 5, Table 6, Table 7, Table 8 and Table 9. A comparison between the predicted values of BKA-BiTCN-BiLSTM-SA model and the experimental measured values is shown in Figure 16.

Figure 10.

Comparison of air temperature model prediction curves for liquid desiccant cooling and dehumidification subsystem.

Figure 11.

Comparison of air humidity model prediction curves for liquid desiccant cooling and dehumidification subsystem.

Figure 12.

Comparison of chilled water temperature model prediction curves for liquid desiccant cooling and dehumidification subsystem.

Figure 13.

Comparison of air temperature model prediction curves for liquid desiccant regeneration subsystem.

Figure 14.

Comparison of air humidity model prediction curves for liquid desiccant regeneration subsystem.

Figure 15.

Comparison of air temperature and humidity prediction performance.

Table 5.

Comparison of air temperature prediction model verification results of liquid desiccant cooling and dehumidification subsystem.

Table 6.

Comparison of air humidity prediction model verification results of liquid desiccant cooling and dehumidification subsystem.

Table 7.

Comparison of chilled water temperature prediction model verification results of liquid desiccant cooling and dehumidification subsystem.

Table 8.

Comparison of air temperature prediction model verification results of liquid desiccant regeneration subsystem.

Table 9.

Comparison of air humidity prediction model verification results of liquid desiccant regeneration subsystem.

Figure 16.

Comparison between the model predicted values and experimental values.

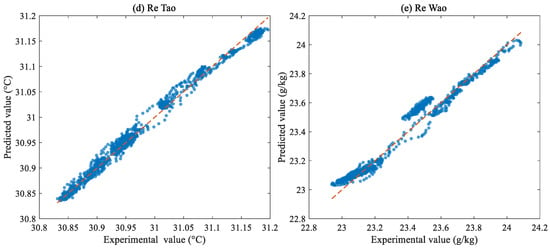

Figure 17 illustrates the convergence process of the BKA across five distinct prediction models (a–e) of the LDAC. Each subplot depicts the descent trajectory of the best fitness during the optimization process, with the evolutionary generation on the x-axis and the MAPE on the y-axis. As shown, the fitness curves of all models exhibit a consistent trend: a rapid initial decline followed by gradual stabilization. This pattern indicates that the algorithm quickly approaches the optimal solution in the early stages and subsequently refines the search. Ultimately, all curves converge to low MAPE values, demonstrating the favorable convergence performance and solution accuracy of the algorithm under various model parameters.

Figure 17.

LDAC air temperature and humidity model BKA evolution curves.

From Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13 and Figure 14, the accuracy of the air temperature and humidity and chilled water temperature prediction models based on BKA-BiTCN-BiLSTM-SA is better than the single TCN, the traditional time-series prediction model CNN-LSTM, and the hybrid prediction model TCN-LSTM. The TCN can effectively capture long-term dependencies in time series through dilated convolution. Specifically, the BKA module enables adaptive hyperparameter optimization, significantly enhancing the model’s convergence efficiency. The BiTCN module facilitates the synchronous capture of multi-scale spatiotemporal features through the parallel processing of forward and backward dilated convolutions. The BiLSTM module incorporates a bidirectional gated memory mechanism to effectively model both long- and short-term contextual dependencies within time-series data. Lastly, the SA module enhances the representation of critical information via dynamic feature weighting.

From the comprehensive comparison in Table 5, Table 6, Table 7, Table 8 and Table 9, it is evident that the proposed BKA-BiTCN-BiLSTM-SA hybrid model consistently outperforms all baseline models across all five prediction tasks, validating the effectiveness of its overall architecture. A deeper analysis yields two key insights: First, the magnitude of performance improvement varies significantly across different tasks. For instance, in predicting the outlet temperature of the solution regeneration subsystem, the model achieves a substantial improvement of 17.613% in compared to the CNN-LSTM model, highlighting its exceptional capability in capturing the rapid thermal dynamics dominated by sensible heat exchange. Second, the proposed model maintains a clear advantage even when compared to baseline models that incrementally incorporate the SA mechanism and bidirectional structures. This indicates that the BKA-driven hyperparameter optimization and the BiTCN-BiLSTM-SA architecture itself produce synergistic gains, rather than merely representing a simple additive combination. These quantitative advantages are visually demonstrated in Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13 and Figure 14. The prediction curves of the proposed model (BKA-BiTCN-BiLSTM-SA) align most closely with the ground truth. Particularly during transient operational phases, as illustrated in Figure 10 and Figure 13, predictions from the baseline models (e.g., TCN, CNN-LSTM) exhibit noticeable phase lags or amplitude deviations. In contrast, leveraging its multi-scale coordination and attention-based focusing capability, the proposed model achieves precise tracking of the dynamic processes. This confirms that the model’s superiority extends beyond leading in static metrics; more critically, it enhances the predictive fidelity for the system’s key dynamic characteristics, which is of decisive significance for realizing real-time optimal control of the LDAC system.

4.3. Discussion and Analysis

The superiority of the proposed model stems from the deep alignment between its architecture and the multi-scale physical characteristics of the LDAC system. Unlike baseline models such as TCN and CNN-LSTM, this model constructs an intelligent “division-coordination” computational framework, rather than a simple stacking of modules. TCN exhibits insufficient sensitivity to high-frequency transient fluctuations, while the serial structure of CNN-LSTM, when extracting local features, tends to weaken the continuous contextual information of the sequence, adversely affecting the modeling of slow, gradual processes. Moreover, traditional feature concatenation is a static fusion method, thus cannot dynamically adjust the importance of different feature sources according to the system’s state. To address these issues, this study designed a parallel dual-path architecture: BiTCN, leveraging its dilated convolutions and bidirectional structure, specializes in capturing minute-level high-frequency pulses; BiLSTM focuses on modeling hour-level long-term evolutions. The SA layer dynamically fusing features from the dual paths, balances the consideration of short-term and long-term information during steady-state operation, while automatically shifting attention towards the high-frequency features extracted by the BiTCN path at transient critical points such as mode switching. This “division-coordination” mechanism achieves a more nuanced mapping of the fast–slow intertwined dynamics in the LDAC system, leading to significant and stable accuracy improvements across all tasks.

The development and validation of the proposed model are based on a dataset obtained from an experimental platform under specific operating conditions, which inherently delineates the boundary of its generalization capability. The model demonstrated excellent predictive performance on the temporally partitioned test set from the same system, indicating strong generalization to unseen historical operating conditions. However, the model’s performance remains subject to certain limitations. For instance, predictive effectiveness may decline under extreme operating conditions outside the training data distribution. When key parameters such as the ambient temperature/humidity significantly exceed the ranges covered in the training set, the model’s capability for physical extrapolation is challenged, and its prediction confidence decreases. The computational cost of the model is primarily concentrated in the training phase. The automated hyperparameter optimization process integrated with the BKA algorithm took approximately 6.5 h. Although this time seems somewhat long, it achieves global optimization of the hyperparameter combination, laying the foundation for the model to maintain stable high performance under different operating conditions. The prediction stage only requires forward computation, which is highly efficient and conducive to real-time deployment. Future work could focus on reducing training costs and enhancing engineering practicality through techniques like lightweight network design and distributed training.

Although this study did not conduct a quantitative global sensitivity analysis of the model input variables, qualitative inferences regarding the physical influence of key parameters can be made based on the heat and mass transfer mechanisms of the LDAC system and relevant literature [39], thereby enhancing the understanding of model behavior. In the dehumidification subsystem, air cooling and dehumidification are primarily governed by the chilled water parameters and solution temperature: the flow rate and temperature of the chilled water directly affect the sensible heat exchange capacity of the cooling coil and the precooling effect of air, while the solution temperature determines the dehumidification driving force by influencing the vapor pressure at the solution surface. Thus, both factors exert a significant impact on the temperature and humidity of the outlet air. In the regeneration subsystem, regeneration performance is mainly dominated by the heat source temperature and solution concentration: the heat source temperature dictates the heat and mass transfer rate in the regenerator, and the solution concentration affects the water vapor partial pressure at the solution surface as well as the regeneration driving force. Consequently, these parameters exhibit high sensitivity to the outlet state of the regeneration air. The above inferences are consistent with the physical mechanisms of the LDAC system and provide a mechanistic basis for understanding the role of key inputs. However, the interaction effects among variables and their specific quantitative contributions to the output still require systematic evaluation through variance decomposition-based global sensitivity analysis in future work, which also represents an important direction for improving model interpretability and reliability.

5. Conclusions

To establish an accurate heat and mass transfer model for the LDAC system, enhance control precision, and reduce energy consumption, this paper proposes a temperature and humidity prediction model based on BKA-BiTCN-BiLSTM-SA. The proposed method is validated using a dataset collected from an LDAC experimental platform. In this model, the BiTCN module, leveraging its dilated causal convolutions and bidirectional structure, excels at capturing local fluctuations at the second-to-minute scale. The BiLSTM module enhances temporal understanding via its bidirectional architecture, enabling simultaneous processing of past and future information. By incorporating SA, the model can automatically assign higher weights to historical data at moments of operating condition transitions. This mechanism enables the model to prioritize the most informative historical states during prediction, which not only improves predictive accuracy, particularly in capturing transient processes, but also enhances the physical interpretability of the model. This provides a window into understanding the decision-making logic of data-driven models.The BKA optimizes model performance by adaptively searching for the optimal combination of hyperparameters. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed BKA-BiTCN-BiLSTM-SA model significantly outperforms the traditional time-series prediction models such as TCN and CNN-LSTM in predicting the outlet air temperature and humidity of the LDAC system. For the air temperature and humidity of both dehumidification and regeneration subsystems, the coefficient of determination exceeds 96.7%. Despite the outstanding performance of the proposed BKA-BiTCN-BiLSTM-SA model, this study still has some limitations, such as that the training process relies heavily on substantial historical data, and the high computational cost of the BKA optimization process. In the future, the research will focus on the lightweight model design and hybrid modeling with embedded physical mechanisms to further improve the model’s practicality, generalizability, and reliability.

Author Contributions

Methodology, X.O., X.W. and Z.W.; Software, X.W. and Z.W.; Validation, X.W.; Writing—original draft, X.W.; Writing—review and editing, X.O.; Supervision, X.O. and X.H.; Funding acquisition, X.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China grant number 62303418 and the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China grant number LQ22F030016.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ohene, E.; Chan, A.P.; Darko, A. Review of global research advances towards net-zero emissions buildings. Energy Build. 2022, 266, 112142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, S.; Kontokosta, C.E.; Vlachokostas, A.; Azar, E. Rethinking HVAC temperature setpoints in commercial buildings: The potential for zero-cost energy savings and comfort improvement in different climates. Build. Environ. 2019, 155, 350–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spandagos, C.; Ng, T.L. Equivalent full-load hours for assessing climate change impact on building cooling and heating energy consumption in large Asian cities. Appl. Energy 2017, 189, 352–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, K.J.; Chou, S.K.; Yang, W.; Yan, J. Achieving better energy-efficient air conditioning–a review of technologies and strategies. Appl. Energy 2013, 104, 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Riffat, S.; Bai, H.; Zheng, X.; Reay, D. Recent progress in liquid desiccant dehumidification and air-conditioning: A review. Energy Built Environ. 2020, 1, 106–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Factor, H.M.; Grossman, G. A packed bed dehumidifier/regenerator for solar air conditioning with liquid desiccants. Sol. Energy 1980, 24, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Xiao, F.; Niu, X.; Gao, D.c. A dynamic dehumidifier model for simulations and control of liquid desiccant hybrid air conditioning systems. Energy Build. 2017, 140, 418–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; Lu, L.; Qi, R. Model development of heat/mass transfer for internally cooled dehumidifier concerning liquid film shrinkage shape and contact angles. Build. Environ. 2017, 114, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Gong, Y.; Niu, X.; Shen, J.; Kosonen, R. Dynamic modeling of liquid-desiccant regenerator based on a state–space method. Appl. Energy 2019, 240, 744–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.Q. Corrections to the simple effectiveness-NTU method for counterflow cooling towers and packed bed liquid desiccant–air contact systems. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2008, 51, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, D.; Braun, J.; Klein, S. An effectiveness model of liquid-desiccant system heat/mass exchangers. Sol. Energy 1989, 42, 449–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, J.E. Methodologies for the Design and Control of Chilled Water Systems. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, S.; Cai, W.; Wang, X.; Wu, Q.; Yon, H. Investigation of liquid desiccant regenerator with fixed-plate heat recovery system. Energy 2017, 137, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Tan, J.; Xie, J.; Du, B.; Liu, H.; Liu, J. Experimental and 4NTU-Le heat and mass transfer model theoretical analysis based on a novel internally cooled liquid desiccant dehumidifier. Energy 2024, 313, 134053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.Y. Sensitivity analysis and component modelling of a packed-type liquid desiccant system at partial load operating conditions. Int. J. Energy Res. 1994, 18, 643–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zhang, K.; Hwang, Y.; Lian, Z. Performance investigation on the ultrasonic atomization liquid desiccant regeneration system. Appl. Energy 2016, 171, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.Y.; Yoon, D.S.; Lee, S.J.; Jeong, J.W. Empirical model for predicting the dehumidification effectiveness of a liquid desiccant system. Energy Build. 2016, 126, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, A.; Babakhani, D. Mathematical modeling of a packed-bed air dehumidifier: The impact of empirical correlations. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2013, 108, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.H.; Park, J.Y.; Jeong, J.W. Simplified model for packed-bed tower regenerator in a liquid desiccant system. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2015, 89, 717–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.; Li, Z.; Rahman, S.M.; Vega, R. A hybrid model approach for forecasting future residential electricity consumption. Energy Build. 2016, 117, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamel, E.; Sheikh, S.; Huang, X. Data-driven predictive models for residential building energy use based on the segregation of heating and cooling days. Energy 2020, 206, 118045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jallal, M.A.; Gonzalez-Vidal, A.; Skarmeta, A.F.; Chabaa, S.; Zeroual, A. A hybrid neuro-fuzzy inference system-based algorithm for time series forecasting applied to energy consumption prediction. Appl. Energy 2020, 268, 114977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, R.; Le-Hung, T.; Nguyen-Thoi, T. Energy consumption prediction of air-conditioning systems in eco-buildings using hunger games search optimization-based artificial neural network model. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 59, 105087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Lu, W.; Zhao, Y.; Qin, P. Prediction of indoor temperature and relative humidity based on cloud database by using an improved BP neural network in Chongqing. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 30559–30566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attoue, N.; Shahrour, I.; Younes, R. Smart building: Use of the artificial neural network approach for indoor temperature forecasting. Energies 2018, 11, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleolo, I.; Abdullah, H.; Mustapha, I.; Mohamad, M.; Jaafar, M.N.M.; Olowolayemo, A.; Sulaiman, S. Long Short-Term Memory Neural Network Model for the Control of Temperature in A Multi-Circuit Air Conditioning System. CFD Lett. 2022, 14, 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmaz, F.; Eyckerman, R.; Casteels, W.; Latré, S.; Hellinckx, P. CNN-LSTM architecture for predictive indoor temperature modeling. Build. Environ. 2021, 206, 108327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhidasan, P.; Mohandes, M. Artificial neural network analysis of liquid desiccant dehumidification system. Energy 2011, 36, 1180–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, A.T.; Mat, S.B.; Sulaiman, M.; Sopian, K.; Al-Abidi, A.A. Implementation and validation of an artificial neural network for predicting the performance of a liquid desiccant dehumidifier. Energy Convers. Manag. 2013, 67, 240–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeidan, E.; Aly, A.A.; Hamed, A.M. Investigation on the effect of operating parameters on the performance of solar desiccant cooling system using artificial neural networks. Int. J. Therm. Environ. Eng. 2010, 1, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhowmik, M.; Naik, B.K.; Muthukumar, P.; Anandalakshmi, R. Performance assessment and optimization of liquid desiccant dehumidifier system using intelligent models and integration with solar dryer. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 64, 105577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Kolter, J.Z.; Koltun, V. Trellis networks for sequence modeling. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1810.06682. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, Y.; Wang, H.; Yan, J.; Liu, Y.; Han, S. Short-term wind power prediction method based on deep clustering-improved Temporal Convolutional Network. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 2118–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayashankara, M.; Sharma, A.; Singh, A.K.; Chanak, P.; Singh, S.K. A novel intelligent modeling and prediction of heat energy consumption in smart buildings. Energy Build. 2024, 310, 114105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Z.; Yang, Q.; Chen, J.; Lan, T.; Zhao, D.; Dou, M.; Liang, B. Degradation prediction of PEMFC based on BiTCN-BiGRU-ELM fusion prognostic method. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 87, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornia, M.; Baraldi, L.; Serra, G.; Cucchiara, R. Predicting human eye fixations via an lstm-based saliency attentive model. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2018, 27, 5142–5154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, W.c.; Hu, X.x.; Qiu, L.; Zang, H.f. Black-winged kite algorithm: A nature-inspired meta-heuristic for solving benchmark functions and engineering problems. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, X.; Cai, W.; He, X.; Zhai, D. Experimental investigations on heat and mass transfer performances of a liquid desiccant cooling and dehumidification system. Appl. Energy 2018, 220, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Cai, W.; Wang, X.; Wu, Q.; Yon, H. Hybrid model for heat recovery heat pipe system in Liquid Desiccant Dehumidification System. Appl. Energy 2020, 182, 383–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.