Abstract

The design of commercial posters must effectively capture consumer attention. To scientifically evaluate the impact of different design formats on attention-grabbing efficiency, three advertising posters were selected. Corresponding dynamic and static, as well as colour and black-and-white (B&W), versions were generated. Sixty participants were recruited for an eye-tracking experiment, recording key metrics such as fixation duration and fixation count. Results indicate: (1) Dynamic posters significantly outperformed static posters for both total fixation duration and total fixation count. When observing the total fixation duration, F = 245.896, p < 0.001, confirming the distinct advantage of dynamic design for capturing attention. (2) Colour posters generally attracted and sustained visual attention more effectively than did B&W posters. When observing the total fixation duration, F = 5.067, p = 0.028 < 0.05. (3) The impact of dynamic effects on attention is more pronounced than that of colour. For both static and dynamic posters, colour and B&W designs show no significant difference in their effect on attention, p = 0.330 > 0.05, η2 = 0.018. This provides a context-dependent prioritisation framework for commercial poster design decisions grounded in visual cognitive science.

1. Introduction

In the era of information explosion, consumers’ attention has become a scarce resource. As a widely used marketing medium, commercial poster design is evolving from mere aesthetic expression to a tool for guiding attention based on cognitive and psychological principles. Consequently, the design of commercial posters must be efficient in capturing the attention of consumers within a limited time frame.

Dynamic visual design demonstrates considerable advantages in information transmission and attention guidance. Research indicates that dynamic elements can effectively enhance visual search efficiency and information recall. This has been validated in the context of memorising health information [1], solving mathematical problems [2], evaluating food sensory attributes [3], providing first aid training [4], and delivering emotional interventions for children with autism [5]. Furthermore, Rayburn-Reeves et al. provided crucial evidence for understanding how dynamic interactive competition across cues shapes behavioural choices in real time through their study of animal behaviour [6]. Relevant technical frameworks have also been applied to areas such as the generation of cultural posters [7]. However, dynamic effects have limitations: they offer no benefit in certain prospective memory tasks [8] and may negatively impact visual working memory by increasing visual complexity [9].

As a fundamental element of visual design, colour profoundly influences cognitive processing and emotional arousal. Research indicates that colour characteristics enhance image retrieval efficiency [10] and directly regulate attentional allocation during visual searches through mechanisms such as hue [11] and background colour [12]. Okubo et al. revealed that inattentional noise induces colour uniformity illusions, highlighting attentional mechanisms’ regulatory role in colour perception [13]. At the application level, warm colour palettes increase advertising gaze and brand recognition [14], while skin tone expressions and avatar colours influence social inferences and attentional biases [15]. Furthermore, colour in food imagery impacts user engagement [16]. Colour also serves as an attentional anchor in multimodal interactions [17], influencing operational efficiency and cognitive comfort in scenarios such as emergency management interfaces [18] and reading environments [19]. Furthermore, integrating colour with dynamics intensifies emotional expression [20], while enhancing the orderliness of colour combinations alleviates cognitive load from high colour complexity while preserving visual richness [21].

Visual attention theory underscores selective attention’s central role in information processing, while eye-tracking technology provides a precise means to quantify attentional patterns. Relevant research has been extensively applied across multiple domains: in social cognition, it has been used to investigate the relationship between loneliness and attentional bias [22] and implicit biases triggered by skin-coloured facial expressions [15]; in environmental and reading studies, it has been employed to construct landscape attractiveness models [23], analyse the effects of background colour and typography on text search [12], and evaluate the impact of lighting on reading efficiency [19]. Within interface and design domains, it has been employed to evaluate the impact of display colours on information retrieval efficiency [18], develop visual perception-based automated typesetting methods [24], and validate animation’s primacy in capturing attention [25]. Furthermore, it has been utilised to explore the role of imagery in guiding attention and behaviour within outdoor signage design [26].

The integration of dynamic design and colour strategies demonstrates potent potential to drive consumer cognition, emotion, and behaviour within commercial communication. Research indicates that dynamic content effectively enhances audience knowledge and engagement, providing empirical support for advertising efficacy [27,28]. The integration of dynamic visuals with elements such as warm colour palettes enhances brand recognition and stimulates sales growth [14]. On a sensory level, dynamic colour cues—such as steam animations—activate temperature perception, thereby increasing food appeal and purchase intent [3]. Related generative technologies, including attention-based animated expression generation models, also provide crucial techniques for creating digital commercial content such as games and virtual avatars [29].

Emerging technologies continue to expand the boundaries of dynamic and colour applications in commerce. Research confirms that immersive dynamic colour advertising delivered via head-mounted devices significantly and sustainably enhances consumer trust in social media influencers, brand attitudes, and purchase intent [30]; dynamic image frameworks within virtual reality have established a new paradigm for commercial displays and product previews [31]. Looking ahead, VR, AR, and AI will collectively drive integrated innovation in dynamic colour across e-commerce, entertainment, and advertising domains [32]. Future research should concentrate on making the most of designs that involve collaboration of dynamics and colour to maximize profits, while dealing with real-life problems such as the ethical concerns regarding AI-generated content and how much it will cost to integrate technology.

However, while existing research has established the individual effects of dynamic design and colour, most studies have examined them in isolation or observed synergistic outcomes only in specific applications. A critical gap remains, i.e., a systematic, quantitative comparison of how different design formats (dynamic/static, colour/B&W) differentially influence visual attention allocation in advertising media and which factor holds dominance. Such a mechanistic analysis is lacking.

From a theoretical framework perspective, this study primarily draws upon three classic cognitive psychological models: the visual salience model, which posits that low-level features such as dynamism and contrast can automatically capture attention through a bottom-up process [33]; emotional arousal theory, which emphasizes that visual stimuli (particularly colour) can induce emotional responses that subsequently regulate attention maintenance and memory encoding [34]; and cognitive load theory, which distinguishes between intrinsic, extrinsic, and relevant cognitive loads, providing principles for optimising multimedia information design to reduce ineffective loads and enhance learning and memory efficiency [35]. Together, these theories form the foundational framework for understanding the underlying mechanisms through which dynamism and colour influence poster attention capture.

Therefore, to scientifically evaluate the attention-capturing efficiency of different poster design formats, this study employs eye-tracking experiments to address the following research questions:

- In commercial posters, does dynamic design demonstrate a significant advantage over static design for attention capture efficiency?

- Do colour designs attract and sustain visual attention more effectively than B&W designs?

- Is there an interaction effect between dynamics and colour?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Stimuli

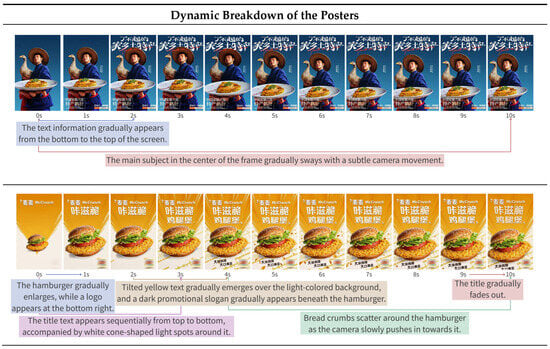

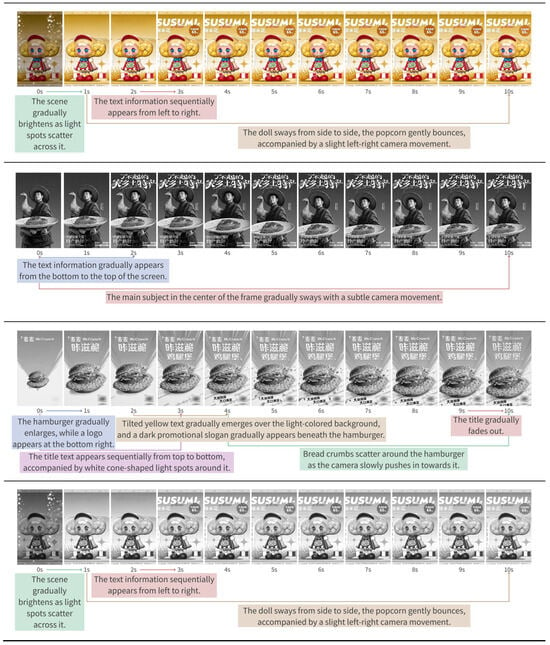

Three colour advertising posters were selected: the Lu’an Goose Liver poster, the McChicken Thigh Burger poster, and the Pop Mart poster. Using Jiemeng AI (ByteDance’s JinYing team has developed a generative artificial intelligence creation platform, Image Model 2.1), dynamic processing was applied to the images and text of the three posters, including shaking, fading, and cut-ins, to generate corresponding dynamic posters. Using Adobe Photoshop (2024 edition, professional image processing software developed by Adobe System) and Jianying (15.8.1, Android, updated on 10 March 2025, video editing application developed by Shenzhen FaceMong Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China, a subsidiary of Douyin), the colour was removed from the three colour static posters and the three colour dynamic posters, generating corresponding B&W static posters and B&W dynamic posters, as shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Static colour advertising posters and static B&W posters.

Figure 2.

Dynamic decomposition of colour and B&W advertising posters.

The static posters were juxtaposed with their corresponding dynamic posters within the same frame, yielding six sets of comparative videos contrasting static and dynamic posters. These six comparison videos were divided into two stimulus groups based on colour versus B&W posters. As shown in Figure 3, both stimulus groups played the following sequence: Lu’an Goose Liver poster, McChicken Thigh Burger poster, Pop Mart poster. Each comparison video played for 10 s.

Figure 3.

The two stimulus groups.

The stimuli cover diverse commercial domains (gourmet food, fast food, trendy toys) and feature typical advertising elements (product image, text, logo) that engage perceptual and semantic processing. Dynamic and colour manipulations were applied to systematically vary visual salience and attentional engagement, supporting the examination of both sensory-driven and cognitively mediated attention in ecologically valid advertising contexts.

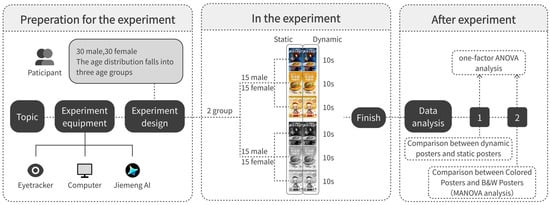

2.2. Participants

The data collected for this study primarily originates from individuals across distinct age brackets: under 20 years old, between 20 and 40 years old, and over 40 years old.

A total of 60 participants were recruited (30 males and 30 females, comprising 20 participants under 20 years old, 20 participants aged 20–40 years old, and 20 participants over 40 years old, ageSD = 11.91, and the age range of 18–50 years). All participants possessed normal vision or vision corrected to normal. They all expressed willingness to cooperate in completing the experiment.

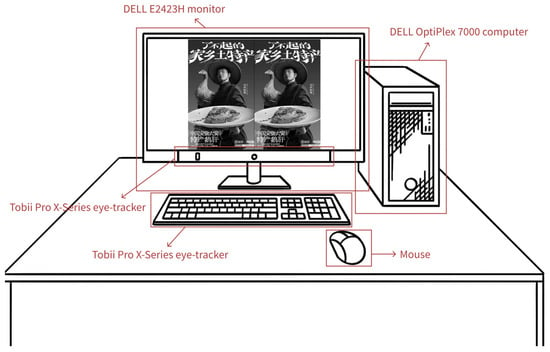

2.3. Apparatus

The eye-tracking experiment was conducted in the Human Factors and Ergonomics Laboratory using the Tobii Pro X series non-contact eye tracker (Tobii, Stockholm, Sweden); Figure 4 shows the equipment used. The equipment included a mainframe computer (Dell OptiPlex 7000 Compact Computer, Dell Inc., Xiamen, China) and a display screen (Dell E2423H, with the screen measuring 53.15 cm in size and 29.90 cm in height with a screen resolution of 1920 × 1080 pixels, Dell Inc., Xiamen, China). Stimuli were presented at the centre of the screen with a white background (the image resolution is 1297 × 1080 pixels). Ergolab 3.0 software, installed on the mainframe computer, assisted the eye tracker in recording the experimental process and collecting, displaying, and exporting each participant’s eye movement data. Laboratory conditions were maintained at a temperature of 25 °C, a humidity of 40%, and suitable lighting.

Figure 4.

Experimental apparatus.

2.4. Eye-Tracking Measurements

To analyse the eye-tracking data, areas of interest (AOIs) were defined for each group prior to the experiment. For colour advertising posters, static and dynamic posters were labelled C1 and C2, respectively. For B&W advertising posters, static and dynamic posters were labelled B1 and B2, respectively. The three advertising posters selected for the experiment—the Lu’an Goose Liver poster, the McChicken Thigh Burger poster, and the Pop Mart poster—were labelled I, II, and III, respectively. As illustrated in Figure 5, the AOI and corresponding numbers were defined for each stimulus. For each stimulus group, several AOI metrics were calculated using Ergolab 3.0: fixation duration, fixation count, total fixation duration, and total fixation count.

Figure 5.

Posters and AOIs for each stimulus group.

It is important to note that this macro-level AOI definition is designed to evaluate differences in overall attention-capturing efficacy between distinct design formats. Consequently, the resulting data (e.g., total fixation duration on a poster) do not support inferences about the specific pathways, sequences, or distributions of attention within the poster (e.g., between text, image, and logo elements). Future research may employ finer-grained AOI segmentation to delve deeper into such intra-stimulus attentional dynamics.

2.5. Procedure

The experiment was conducted using two stimulus groups. Participants viewed stimuli from a distance of 60 cm from the screen centre. Each stimulus group was presented within a 1920 × 1080 pixel rectangle. Following viewing tests with different individuals prior to the formal experiment, the total viewing duration for each stimulus group was set to 30 s, with each comparison poster viewed for 10 s. To eliminate extraneous variables, participants received a brief introduction to the procedure and relevant precautions prior to the experiment.

Sixty participants were divided into two groups, and the experiment was conducted sequentially. Participants were instructed to focus solely on the stimulus sections of interest without performing any other actions. Participants were evenly split by gender and age to view either Stimulus Group 1 or Stimulus Group 2. The general experimental procedure is illustrated in Figure 6. The variable labels and key experimental factors used in this study are presented in Table 1 and Table 2.

Figure 6.

Process illustrating the comparative effectiveness of different design formats in capturing attention.

Table 1.

List of labels for each variable.

Table 2.

Experimental critical factor.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

To quantify the differences in visual attention allocation across the experimental conditions, statistical analyses were performed on the eye-tracking metrics (Total Fixation Duration and Total Fixation Count). Prior to analysis, the data underwent normality testing (Shapiro–Wilk test) and homogeneity of variance testing (Levene’s test). The results indicate that the data satisfy the fundamental assumptions for analysis of variance. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was first employed to assess the main effects of design format (dynamic versus static) and colour (colour versus B&W) on attention capture efficiency. To examine the potential interaction effect between dynamicity and colour, a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was conducted. The statistical significance level was set at α = 0.05. All analyses were carried out using the statistical module within IBM SPSS Statistics 27.0.1 software, and data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (M ± SD), where applicable.

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of the Effectiveness of Dynamic Versus Static in Capturing Attention

3.1.1. Analysis of Participants’ Attention to Static and Dynamic Posters

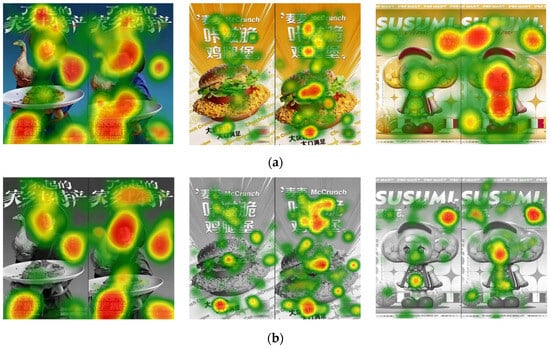

This section employs a one-way ANOVA with static versus dynamic as the influencing factor to analyse differences in participants’ attention towards static and dynamic posters. Figure 7 shows the heat map obtained from participants watching both static and dynamic forms of posters simultaneously.

Figure 7.

Participants’ heat maps after watching static and dynamic posters at the same time. (a) Heat map obtained from 30 participants after watching colour static posters and dynamic posters at the same time. (b) Heat map obtained from 30 participants after watching black and white static posters and dynamic posters at the same time.

For both dynamic and static stimuli, the fixation duration for C1 was 233.37 s, while that for C2 was 459.55 s. The fixation duration for B1 was 228.73 s, and for B2, it was 410.69 s. The fixation count for C1 was 1123, while that for C2 was 1875. The number of fixations for B1 was 1069, while that for B2 was 1868. The total fixation duration for S was 462.10 s, whereas that for D was 870.24 s, with S being lower than D. The total fixation count for S was 2192, in comparison to 3743 for D. Specific data are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Data analysis of participants’ perceptions of static versus dynamic elements for attention capture efficiency.

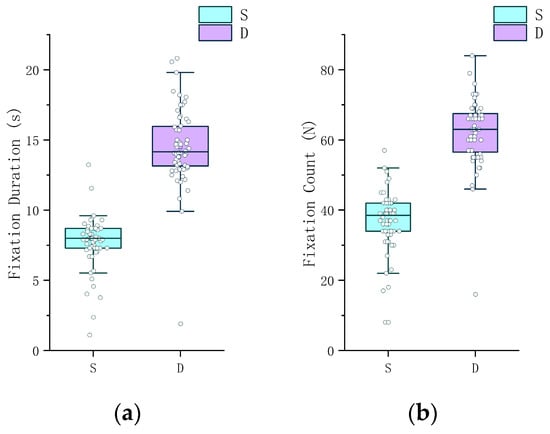

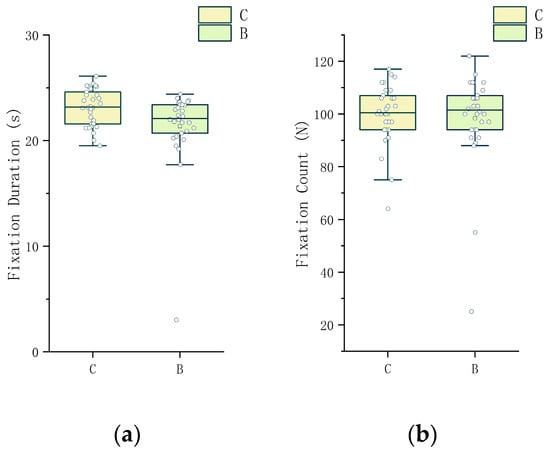

Regarding fixation duration, dynamic and static posters exerted a significant influence, F = 245.896, p < 0.001. The relevant findings are illustrated in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Statistical data regarding participants’ fixation patterns for dynamic and static posters: (a) fixation duration for static and dynamic posters; (b) fixation count for static and dynamic posters.

The data indicate that across all three poster groups, dynamic posters elicited longer fixation duration and more frequent fixations than did static posters, demonstrating that dynamic posters are more effective than static posters at capturing attention.

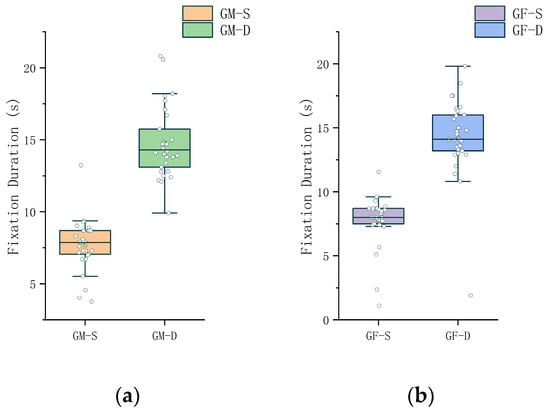

3.1.2. Analysis of Attention to Static and Dynamic Posters Among Participants of Different Genders

By gender, the total fixation duration of attention for GM was 672.82 s, while that for GF was 659.52 s, with no significant difference between GM and GF. Specific data is presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Data analysis of attention-capturing efficiency between male and female participants.

Figure 9 illustrates that, with regard to fixation duration, GM-D elicited longer fixations than did GM-S, with a significant difference between the two types of posters. In a similar manner, GF-D was observed to elicit longer fixations than did GF-S, a finding that demonstrated a significant disparity between the two types of posters. This finding suggests that gender does not influence the effectiveness of dynamic versus static posters in capturing attention.

Figure 9.

Statistics regarding fixation duration for dynamic and static posters across different genders: (a) fixation duration for male participants viewing static and dynamic posters; (b) fixation duration for female participants viewing static and dynamic posters.

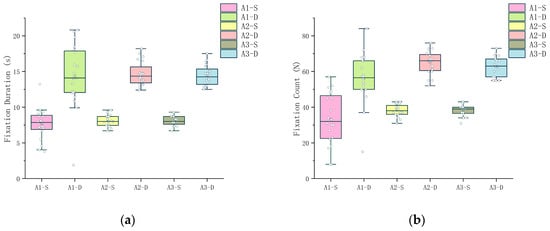

3.1.3. Attention Analysis of Static and Dynamic Posters Among Participants of Different Ages

In terms of age, the fixation duration for A1-S was 138.90 s, while that for A1-D was 287.64 s, indicating a significant effect, F = 39.078, p < 0.001. The fixation duration for A2-S was 161.60 s, while that for A2-D was 293.90 s, indicating a significant effect, F = 291.689, p < 0.001. The fixation duration for A3-S was 161.60 s, while that for A3-D was 288.70 s, indicating a significant effect, F = 330.338, p < 0.001. Detailed data are presented in Table 5 and Figure 10. This indicates that participants’ age had no influence on the study of attention capture efficiency between dynamic and static posters.

Table 5.

Data analysis of attention capture efficiency across different age groups of participants.

Figure 10.

Statistical data regarding participants’ gaze behaviour towards dynamic and static posters across different age groups: (a) fixation duration on static versus dynamic posters among participants of varying ages; (b) fixation count on static versus dynamic posters among participants of varying ages.

3.2. Comparative Analysis of Colour and B&W Posters for Attention-Capturing Efficiency

3.2.1. Overall Comparison of Colour and B&W Posters for Attention-Capturing Efficiency

The present section employs a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with colour as the independent variable to examine visual attention differences between colour and B&W posters.

For both colour and B&W stimuli, the fixation duration for I-C was 232.27 s, and that for I-B was 211.32 s. The fixation duration for II-C was 231.57 s, and that for II-B was 217.14 s. The fixation duration for III-C was 229.18 s, and that for III-B was 212.69 s. The fixation count for I-C was 1002, and that for I-B was 994. The fixation count for II-C was 1037, and that for II-B was 1011. The fixation count for III-C was 959, in comparison to 944 for III-B. The total fixation duration for C was 693.02 s, while for B it was 641.16 s. The total fixation count for C was 2998, while for B it was 2949. Specific data are presented in Table 6 and Figure 11.

Table 6.

Data analysis of participants’ responses regarding the efficiency of colour and B&W posters in capturing attention.

Figure 11.

Statistical data regarding participants’ fixation on colour and B&W posters: (a) fixation duration for colour and B&W posters; (b) fixation count for colour and B&W posters.

For fixation duration, C and B showed a significant effect, F = 5.067, p = 0.028 < 0.05. The data indicate that C outperformed B in terms of fixation duration and fixation count, demonstrating that colour holds a greater advantage than B&W in capturing attention.

3.2.2. Detailed Comparison of Attention-Capturing Efficiency Between Colour and B&W Posters

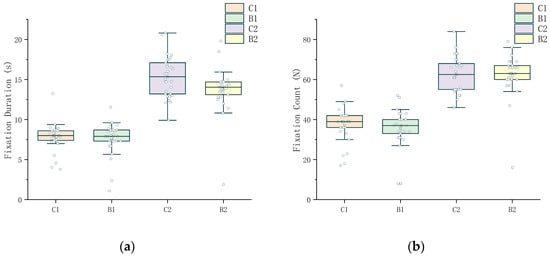

To examine the interactive effects of dynamics and colour on attention capture, we employed MANOVA for analysis.

The results indicate that the main effect of dynamics was highly significant (Wilks’ Λ = 0.147, F = 148.050, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.853), but the main effect of colour was not significant (p = 0.498 > 0.05, η2 = 0.027). Detailed data are presented in Table 7 and Figure 12.

Table 7.

Participants’ data analysis of cross-factors’ efficiency in capturing attention.

Figure 12.

Participants’ attention data analysis for colour versus B&W static posters and colour versus B&W dynamic posters: (a) participants’ fixation duration for colour versus B&W static posters and colour versus B&W dynamic posters; (b) participants’ fixation count for colour versus B&W static posters and colour versus B&W dynamic posters.

The interaction between dynamic and colour factors also proved no significant effect (Wilks’ Λ = 0.967, p = 0.330 > 0.05, η2 = 0.018), indicating that the dominance of the dynamic effect remains unaffected by colour conditions. This may stem from limitations in sample size and the inherent overwhelming advantage of the dynamic effects themselves.

4. Discussion

This study investigated the impact of dynamic design and colour application on attention-capturing efficiency in commercial posters through an eye-tracking system. Experimental results indicate that dynamic designs significantly outperform static designs in attention-capturing efficiency, while colour designs generally attract and sustain visual attention more effectively than do B&W designs. From a visual cognitive perspective, the advantage of dynamic elements can be explained by the visual salience model: dynamic cues, as strong bottom-up stimuli, automatically capture pre-attentive resources, guiding the gaze to rapidly lock onto changing areas, thereby significantly increasing both gaze duration and count. The role of colour in sustaining attention is closely linked to the arousal theory—colours, especially high-saturation or warm tones, evoke more positive emotional responses, enhancing cognitive engagement and information processing depth, thereby improving overall gaze stability and recall potential.

Notably, an asymmetric interaction exists between dynamics and colour. Under both static and dynamic conditions, attention differences between colour and B&W designs failed to reach statistical significance, suggesting that the impact of dynamic effects on attention capture may override colour influences. In other words, when designs already incorporate dynamic elements, the additive effect of colour is relatively diminished; conversely, for static designs, colour’s enhancing role remains insufficient to establish a decisive advantage. This further demonstrates that, under limited cognitive resources, dynamic cues hold priority at the salience level.

Combined with cognitive load theory, the judicious use of dynamics and colour essentially optimises information processing pathways: dynamics reduce visual search load through exogenous guidance, while colour enhances information integration fluency through emotional activation. The observed synergy in enhancing total fixation duration suggests that the combined use of dynamics and colour may streamline the initial attention-capturing process, potentially freeing cognitive resources for subsequent content processing. Therefore, excellent poster design is not merely about grabbing attention; it involves systematically coordinating dynamics and colour to guide attention along low-load, high-arousal pathways, thereby more effectively activating an individual’s attention and memory systems.

A key methodological aspect of this study was the use of generative AI tools (Jiemeng AI) to create the dynamic versions of the posters. This approach was deliberately chosen to address a critical challenge in comparative design research: ensuring high experimental control and reproducibility. By applying predefined, standardized dynamic effects (e.g., specific shake and fade parameters) through an automated, template-driven workflow, we minimized the introduction of unintended variability that could arise from manual animation or different animator styles. This ensured that the “dynamic” manipulation was as consistent as possible across the three distinct poster contents, thereby strengthening the internal validity of our comparison between dynamic and static conditions. We have documented the specific tools, templates, and procedural steps in the Methods section to facilitate future replication and extension of this work. While this approach excels in standardization, future research could further explore the parameter space of such AI-generated effects (e.g., varying motion speed or complexity) to fine-tune the relationship between dynamic salience and viewer perception.

This study treats the “human–advertisement” interaction as a cognitive system centred on visual attention, with its core challenge being how to maximize the capture and maintenance efficiency of visual attention through design interventions within a limited time. The study developed an eye-tracking-derived metric system: total fixation duration reflects cognitive resource investment, while fixation count indicates information exploration activity. These metrics provide a mid-level assessment framework for evaluating poster effectiveness. While dynamic and colour designs enhance attention, they may also pose risks such as visual fatigue, cognitive overload, or distraction—particularly when dynamic overload or colour conflicts increase unnecessary cognitive load. Therefore, design practice should pursue a balanced configuration of dynamics and colour, coordinating salience guidance, emotional arousal, and cognitive load to achieve sustainable attention capture and positive user experience. Future research can build upon this study by integrating multidimensional data and long-term effect observations to establish a more robust and systematic poster design guidance framework.

This study is a foundational visual cognition experiment. All stimulus materials are modified versions of publicly available commercial advertising posters, with harmless content. The experimental task involves only natural viewing, without any pressure tasks, deceptive information, or sensitive content. Therefore, the risk to participants is minimal, limited to mild visual fatigue (all participants may rest or withdraw at any time). This study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of Nanjing Forestry University, and informed consent was obtained from all participants. All data have been anonymized to fully safeguard participants’ rights and privacy.

We must clarify that the eye-tracking experimental paradigm employed in this study is fundamentally designed as an “effectiveness evaluation method”, not as an “individual clinical diagnostic tool”. Its specific objective is defined as: quantitatively comparing the differential effects of two design variables—“dynamic/static” and “colour/black-and-white”—on group attention within a controlled environment to test visual cognition theories to provide commercial poster designers with an evidence-based hierarchical decision reference (i.e., prioritizing dynamics over colour) for optimising design resource allocation and enhancing advertising’s attention-capturing efficiency. This study establishes a group-level, design-oriented evaluation framework aimed at assessing the effectiveness of design rather than diagnosing the cognitive state or abilities of individuals.

5. Limitations and Future Research

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, the side-by-side presentation of static and dynamic posters, while designed to emulate a competitive media environment where advertisements vie for consumer attention, may have inherently favoured dynamic stimuli. Motion is a potent bottom-up attentional cue, and its direct contrast with static elements in the same visual field likely maximizes its salience advantage. Therefore, the large effect size we observed for dynamic design (e.g., F = 245.896) should be interpreted as its efficacy under conditions of direct competition. This does not diminish the practical relevance of the finding—as such competitive scenarios are common in digital advertising—but it suggests that the magnitude of the advantage might be less pronounced in isolated viewing contexts.

Second, as noted in the Methods section, our macro-level AOI analysis precludes insights into fine-grained attentional allocation within posters. Future research could address these points by employing isolated presentation paradigms to establish baseline attention levels and using finer-grained AOIs to understand how design elements guide attention internally, even within a competitive framework.

Third, related to our measurement approach, it is crucial to re-emphasize that defining each entire poster as a single area of interest (AOI) was a deliberate choice to facilitate the macro-comparison of design formats. While this provided clear metrics for overall attention capture (e.g., total fixation duration on a poster), it inherently limits the granularity of our conclusions. Our data and analysis do not support inferences about the distribution of attention within a poster—such as which specific elements (e.g., headline, product image, logo) were most attended to or the sequence in which they were viewed.

Furthermore, the potential influence of specific advertisement content (e.g., product category, brand familiarity, inherent visual appeal of the product) on attentional outcomes warrants consideration. Our study employed posters from three distinct commercial domains (gourmet food, fast food, trendy toys) to increase ecological validity and test the generalizability of design effects across contexts. While the core findings regarding the superiority of dynamic over static design and the dominant role of dynamism were qualitatively consistent across all three poster types, our experimental design was not optimised to statistically isolate or quantify the interaction between content type and design format. Therefore, while our results demonstrate that dynamic and colour design principles are effective across varied content, future research should systematically manipulate content type as an independent variable to determine whether the strength of these design effects is modulated by the nature of the advertised product or the viewer’s personal interest in it.

Therefore, our findings robustly address the question of “whether and how much a dynamic or colour design captures attention overall”, but they cannot elucidate “how attention navigates the internal layout of a poster” or “which element within a dynamic design is primarily responsible for its advantage”. Future research employing element-level AOIs is needed to uncover these finer-grained attentional mechanics, which would complement our broader findings.

6. Conclusions

This study employed eye-tracking technology to analyse differences in participants’ attentional focus towards advertising posters with varying design formats (dynamic/static, colour/B&W). User tracking data was integrated to determine which design format proved more compelling. Experimental findings are as follows:

- Dynamic designs demonstrated a significant advantage over static designs for attention capture efficiency (F = 245.896, p < 0.001).

- Colour designs generally attract visual attention more effectively than do B&W designs (F = 5.067, p = 0.028 < 0.05).

- Under experimental conditions involving a side-by-side comparison, the dynamic design was found to exert a stronger influence on capturing attention than was the presence of colour alone (Wilks’ Λ = 0.967, p = 0.330 > 0.05, η2 = 0.018).

While the general advantage of dynamic over static design aligns with established principles of visual salience, this study provides several novel and nuanced contributions. First, it quantifies the overwhelming magnitude of this advantage (F = 245.896) in a realistic, competitive viewing paradigm where posters are directly compared. Second, and more importantly, it reveals a critical interaction: the potent effect of dynamic design can subordinate the influence of colour, as evidenced by the non-significant difference between colour and B&W versions within dynamic conditions (p = 0.330). This finding moves beyond confirming a known principle and offers a hierarchical, context-sensitive guideline for designers: in scenarios where capturing immediate attention is paramount and dynamic elements are employed, prioritising the optimisation of motion dynamics may be more impactful than refining colour schemes. Thus, the study’s contribution lies in detailing how and under what conditions the known effect of dynamics operates and interacts with other design factors, providing a refined evidence base for applied design decisions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.C.; methodology, C.C. and S.Y.; validation, S.Y.; for- mal analysis, S.Y.; investigation, S.Y. and J.W.; data curation, S.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, S.Y.; writing—review and editing, C.C.; visualization, S.Y.; supervision, C.C.; project administration, C.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper was supported by a National Nature Science Foundation of China Grant (No. 72201128) and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 2023M730483).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the low-risk nature of the research and the use of fully anonymized data. The approving agency for the exemption is Nanjing Forestry University.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study. This study was approved by the school ethics committee.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy concerns.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Laboratory of Human Factors and Ergonomics of NJFU for supporting the experiments. During the preparation of this work, the authors used DeepSeek (V2.0) in order to improve language. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hansen, S.; Jensen, T.S.; Schmidt, A.M.; Strøm, J.; Vistisen, P.; Høybye, M.T. The Effectiveness of Video Animations as a Tool to Improve Health Information Recall for Patients: Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 26, e58306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehrhart, T.; Lindner, M.A. Computer-Based Multimedia Testing: Effects of Static and Animated Representational Pictures and Text Modality. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2023, 73, 102151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Desebrock, C.; Okajima, K.; Spence, C. ‘Hot Stuff’: Making Food More Desirable with Animated Temperature Cues. Food Qual. Prefer. 2024, 120, 105233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohk, T.; Cho, J.; Yang, G.; Ahn, M.; Lee, S.; Kim, W.; Lee, T. Effectiveness of a Dispatcher-Assisted CPR Using an Animated Image: Simulation Study. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2024, 78, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, M.; Jin, S.; Fan, J.; Guo, W.; Chen, X. EmoLand: Utilizing Narrative Animations, Multilevel Games, and Affective Computing to Foster Emotional Development in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2025, 199, 103486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayburn-Reeves, R.M.; Qadri, M.A.J.; Brooks, D.I.; Keller, A.M.; Cook, R.G. Dynamic Cue Use in Pigeon Mid-Session Reversal. Behav. Process. 2017, 137, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Liu, F.; Li, B.; Liu, Z.; Ma, W.; Ran, C. CrePoster: Leveraging Multi-Level Features for Cultural Relic Poster Generation via Attention-Based Framework. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 245, 123136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Félix, S.B.; Poirier, M.; Pandeirada, J.N.S. Exploring the Animacy Effect in Focal Prospective Memory Tasks: When Animates Don’t Stand out. J. Mem. Lang. 2025, 144, 104673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, X.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, S.; Xu, W.; Zhang, N. The Effects of the Complexity of 3D Virtual Objects on Visual Working Memory Capacity in AR Interface for Mobile Phones. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thammastitkul, A. Optimizing AI-Generated Image Metadata with Hybrid Color Analysis and Semantic Keyword Structuring. Egypt. Inf. J. 2025, 31, 100775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forschack, N.; Oxner, M.; Müller, M.M. The Consequences of Color Chromaticity on Electrophysiological Measures of Attentional Deployment in Visual Search. iScience 2025, 28, 112252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, B.; Xu, L.; Yu, L. Tailored Information Display: Effects of Background Colour and Line Spacing on Visual Search across Different Character Types–an Eye-Tracking Study. Displays 2025, 88, 103019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okubo, L.; Miyoshi, K.; Yokosawa, K.; Nishida, S. Inattentional Noise Leads to Subjective Color Uniformity across the Visual Field. Cognition 2024, 266, 106293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.; Ma, C. The Enhancing Effect of Multimedia Elements on Brand Cognition and Memory in Advertising Design. J. Cases Inf. Technol. 2025, 27, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelica, S.; Aguiar, T.R.; Frade, S.; Guerra, R.; Prada, M. Are You What You Emoji? How Skin Tone Emojis and Profile Pictures Shape Attention and Social Inference Processing. Telemat. Inform. 2024, 95, 102207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casales-Garcia, V.; Museros, L.; Sanz, I.; Gonzalez-Abril, L. Analyzing Aesthetics, Attractiveness and Color of Gastronomic Images for User Engagement. Cognit. Syst. Res. 2025, 91, 101358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junjie, S.; Taijiro, N.; Yoko, N. Estimating Imagined Colors from Different Music Genres with Eye-Tracking. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 246, 3684–3693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, M.; Zhang, Q. Selection of Optimal Display Color for China’s Emergency Management System Using Eye Tracking. Displays 2025, 87, 102888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yao, R. Assessing the Impact of Office Artificial Lighting on Young Adults’ Reading Performance through Eye-Tracking Analysis. Build. Environ. 2025, 285, 113532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handayani, N.D.P.; Faizah, N.; Astuti, M.D.; Yupi, E.E.; Purwandari, E. Reflective Journal as a Solution for Emotional Regulation to Anti-Momster “Mama Monster”. Community Empower. 2024, 9, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, S.; Di, X.; Li, W. Moderating Effects of Visual Order in Graphical Symbol Complexity: The Practical Implications for Design. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeifer, J.; De Winter, J.; Dodou, D.; Eisma, Y.B. Loneliness, Personality, and Attention to AI-Generated Images Depicting Social Threat: An Eye-Tracking Study. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2025, 247, 113415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Fang, M.; Yang, D.; Wangari, V.W. Quantitative Evaluation of Attraction Intensity of Highway Landscape Visual Elements Based on Dynamic Perception. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2023, 100, 107081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Sheng, D.; Yao, J.; Shen, Z. Poster Graphic Design with Your Eyes: An Approach to Automatic Textual Layout Design Based on Visual Perception. Displays 2023, 79, 102458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, M.N.; Khislavsky, A.L.; Coverdale, M.E.; Gilger, J.W. Adaptive Attention: How Preference for Animacy Impacts Change Detection. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2016, 37, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, W.L.; Shellhorn, J.; Bloomgren, V.; Booth, L.; Duncan, S.; Elias, J.; Flowers, K.; Gambini, I.; Gans, A.; Medina, A.; et al. The Impact of Graphic Design on Attention Capture and Behavior among Outdoor Recreationists: Results from an Exploratory Persuasive Signage Experiment. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2023, 42, 100606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Yang, B.; Zhang, Z. New Media Technology in Digital Animation Art Teaching Experimental Exploration: Impact Analysis and Future Prospects. Int. J. Knowl. Manag. 2025, 21, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manurung, R.D.; Tambunan, S.G.P. The Effect of Education with Animation Media and Picture Pockets on Knowledge, Attitude and Action in the Family of Pulmonary TB Patients in Preventing Transmission. J. Aisyah J. Ilmu Kesehat. 2022, 7, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, C. Research on Animation Character Expression Generation Based on Attention Conditioned Cyclegan. J. Cases Inf. Technol. 2024, 26, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaban, D.C.; Mucundorfeanu, M.; Szambolics, J.; Amrhein, C. Examining the Immediate and Delayed Impact of Immersive Media on the Effectiveness of Social Media Influencer Advertising: An Experimental Approach. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2025, 19, 100781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z. Dynamic Visual Communication Image Framing of Graphic Design in a Virtual Reality Environment. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 211091–211103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhong, W. Evolution and Innovations in Animation: A Comprehensive Review and Future Directions. Concurr. Comput. Pract. Exper. 2024, 36, e7904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itti, L.; Koch, C.; Niebur, E. A Model of Saliency-Based Visual Attention for Rapid Scene Analysis. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 1998, 20, 1254–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, M.M.; Lang, P.J. Measuring Emotion: The Self-Assessment Manikin and the Semantic Differential. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 1994, 25, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweller, J. Cognitive Load Theory, Learning Difficulty, and Instructional Design. Learn. Instr. 1994, 4, 295–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.