Abstract

Collision accidents involving merchant ships and fishing vessels are a crucial issue for maritime navigation safety, having received widespread attention due to their high frequency and serious effects. A statistical analysis of 142 collision accidents between merchant ships and fishing vessels from 2014 to 2025 was conducted to determine the regularity characteristics and causes of collisions in China’s coastal waters. This study investigated the characteristics of collision accidents, such as occurrence time, accident waters, ship length, and ship type, and used the grey relational analysis (GRA) method to analyze the accident causes. The causes of collision accidents involving merchant ships and fishing vessels were quite complicated, impacted not just by human factors but also by ship factors, environmental factors, and management factors. This study explored the characteristics of the collision accidents, including occurrence time, accident waters, ship length, and ship type, and analyzed the causal factors of the accidents using the grey relational analysis method. The causes of collision accidents between merchant ships and fishing vessels were relatively complex, being influenced not only by human factors but also by ship factors, environmental factors, and management factors. By ranking and comparing the relational degree values of the causal factors, three key factors were identified: X1 (failure to maintain a proper lookout) with the highest correlation degree of 0.93, X3 (improper emergency response) with the second highest correlation degree of 0.91, and X9 (complex navigation environment) with the third highest correlation degree of 0.84. Finally, based on the preceding research, suitable recommendations were made to provide a clear priority direction for accident prevention and control, as well as effective motivation for preventing or minimizing collision accidents involving merchant ships and fishing vessels.

1. Introduction

The prosperity of the maritime shipping industry has driven sustained growth in demand for merchant ship navigation, characterized by continuous increases in ship tonnage and navigation density. Meanwhile, the fishing areas of the fishery industry have expanded from coastal harbours to the open sea, forming intensive intersections with busy merchant shipping routes. With changes in the marine environment and the development of offshore wind power, as well as the construction of oil platforms and other marine engineering facilities, the navigable waters available for merchant ships have been reduced to a certain extent. Furthermore, the overlap between fisheries and merchant shipping routes has resulted in a long-term high incidence of collisions. Particularly in China’s coastal waters, the large number of coastal merchant ship ports and fishing ports has led to a high degree of overlap between the inbound and outbound routes of merchant ships and traditional fishing areas. Coupled with the dense distribution of fishing vessels during fishing seasons, merchant ships and fishing vessels frequently encounter each other in a short period, significantly increasing the complexity of the navigation environment and substantially raising the baseline of collision risks. Consequently, collision accidents between merchant ships and fishing vessels occur with considerable frequency.

Collision accidents between merchant ships and fishing vessels constitute one of the crucial factors affecting the safety of water transportation [1,2,3,4]. Collision accidents of fishing vessels with other ships have become one of the major hazards faced by marine fishermen [5]. Fishing vessel accidents account for approximately 70% of the total maritime accidents in South Korean waters, and collision accidents are classified as a high-risk accident type in terms of both frequency and severity of consequences [6]. In recent years, the proportion of collision accidents between merchant ships and fishing vessels among all maritime accidents in China’s coastal waters has been relatively prominent. Data released by the Maritime Safety Administration of the People’s Republic of China regarding collision accidents from 2014 to 2023 indicate that collision accidents between merchant ships and fishing vessels accounted for 48% [7]. Although the Ministry of Transport of the People’s Republic of China and the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs have jointly issued the “Three-Year Tackling Action Plan for Co-governance of Merchant Ships and Fishing Vessels (2024–2026)” to continuously deepen the prevention and control of collision risks between merchant ships and fishing vessels, such collision accidents still occur repeatedly.

Collision accidents between merchant ships and fishing vessels have attracted considerable attention from scholars at home and abroad due to their relatively high occurrence frequency and severe consequences [1,2,3,7,8,9]. Uğurlu et al. [9] used a Bayesian network and the chi-square method to study fishing vessel accidents worldwide from 2008 to 2018 involving fishing vessels with an overall length of 7 m and above, including the causes of fishing vessel collisions, and put forward suggestions for preventing accidents. Yang et al. [1] studied the relevant information of collision accidents between merchant ships and fishing vessels in China from 2016 to 2020 and adopted the weighted kernel density estimation method to intuitively analyze the spatial distribution of collision accidents between merchant ships and fishing vessels. Dong et al. [4] used the N-K model to quantify the interaction effects between the causal factors in collision accidents between merchant ships and fishing vessels. Gai et al. [8] utilized fuzzy logic and C-means clustering methods to analyze the Automatic Identification System (AIS) data of fishing vessels, and evaluated the collision risk of fishing vessels, thereby providing a novel perspective for collision avoidance decision-making between merchant ships and fishing vessels. Wang et al. [2] proposed a hybrid method combining the human factors analysis and classification system and Bayesian network to study the human and organizational factors in collision accidents between merchant ships and fishing vessels. Zhu et al. [3] proposed a collision risk assessment method for merchant ships and fishing vessels in coastal waters, classified ship collision scenarios, extracted risk data under different collision scenarios, and conducted visual analysis on areas prone to dangers. Zhang et al. [7] used the AIS movement trajectories and interaction patterns of merchant ships and fishing vessels in Qingdao Port during the peak fishing season to evaluate collision risks and found that when fishing vessels took evasive measures first, the overall collision risk between merchant ships and fishing vessels was mainly concentrated in the range of 0.4–0.8.

The causes of collision accidents between merchant ships and fishing vessels are numerous, involving human factors, ship factors, environmental factors, and management factors [2,4,10]. Human factors are the primary cause of maritime accidents and collisions [10,11,12,13]. Uğurlu and Cicek [10] pointed out that effective communication between ships during navigation and good teamwork among bridge personnel are crucial for reducing the occurrence of ship collisions. Du et al. [11] concluded that serious negligence in the lookout post, failure to correctly assess collision risks, and failure to adopt safe speeds would significantly affect collision accidents between merchant ships and fishing vessels. Wang et al. [12] studied that “failure to take timely and effective collision avoidance measures” constitutes a critical factor affecting the occurrence of such collision accidents. Yong-Ye and Su-Hyung [13] employed a Bayesian network approach to analyze the risk factors contributing to maritime accidents involving South Korean ocean-going fishing vessels, revealing that collisions of such vessels are primarily associated with inadequate lookout. In addition to being determined by human factors, the occurrence of collision accidents between merchant ships and fishing vessels is also affected by ship factors, environmental factors, and management factors. Ship factors are also one of the factors affecting collision accidents [14]. There is a relatively complex relationship between ship conditions and accident frequency, which is influenced by various parameters, such as ship type and construction quality, the quality and extent of ship maintenance and operation, the timing of major classification society inspections, and potential changes in ownership. Management factors can also lead to ship collisions [15]; for example, inadequate safety management by shipping companies/shipowners can create favourable conditions for the occurrence of collision accidents. Wang et al. [2] studied the impacts of human and organizational factors on collision accidents between merchant ships and fishing vessels. Moreover, Hayrulnizam et al. [16] concluded that the collision accident between Cargo Ship Edmy and Fishing Vessel Tornado was caused by a combination of multiple factors. The above research methods mostly analyze the causes of collision accidents between merchant ships and fishing vessels from a single factor or two factors, and there are few studies that simultaneously analyze the composite effects of multiple factors such as human factors, ship factors, environmental factors, and management factors on collision accidents between merchant ships and fishing vessels.

Collision accidents between merchant ships and fishing vessels are the result of the combined action of multiple factors, where various factors are intertwined with complex influence mechanisms. The aforementioned methods are still insufficient in clearly identifying key causal factors, secondary causal factors, and potential associated factors, while the grey relational analysis (GRA) method provides an approach to address the problem. Undoubtedly, the occurrence of ship collision accidents is the result of the correlation and interaction of complex causal factors, and the combination of the GRA method can effectively improve the accuracy of statistical results. At present, the GRA method has been applied in the field of waterway transportation [17,18,19,20,21]. Wang and Lee [17] applied the GRA method to analyze maritime casualties occurring in Keelung Port, exploring the correlation between maritime casualties and accident scenes, and the study found that fires or explosions, as well as mechanical damage, are the main causes of maritime casualties. Teng et al. [18] established a water traffic safety evaluation model based on the GRA method and evaluated the water traffic safety status of shipping companies through correlation analysis. Dong et al. [19] established a ship collision risk level evaluation system using the GRA method and found that the time periods when collision accidents occur are positively correlated with the time periods with high risk levels. Bai et al. [20] used the weighted grey relational analysis method to weight the factors affecting ship main engine failures, study the correlation between main engine failures and ship characteristics, and calculate the relational degree between main engine failures and main engine failure events. Sur and Kim [21] adopted an integrated sequential priority approach and the GRA method to assign appropriate weights to three criteria (frequency, deaths, and injuries) and rank eight accident types. The GRA method can simultaneously evaluate the composite effects of multiple factors, such as human factors, management factors, environmental factors, and ship factors.

Therefore, to study the characteristics and causes of collision accidents between merchant ships and fishing vessels, this study was based on the statistical data of 142 collision accidents between merchant ships and fishing vessels in China’s coastal waters from 2014 to 2025. It analyzed the occurrence laws of the collision accidents from multiple dimensions, including the basic accident information, accident occurrence months, time periods, water areas, and related ship characteristics. The GRA method was used to explore the causal laws of collision accidents between merchant ships and fishing vessels, clearly identified the key causal factors through relational degree values, and sorted and compared the relational degrees of these causal factors. Finally, based on the above analysis, suggestions have been put forward to provide a clear priority direction for accident prevention and control, so as to offer valuable insights for preventing collision accidents between merchant ships and fishing vessels and strengthening the safety management of the shipping industry. The following sections present the paper’s organization: Section 2 is the materials and methods. Section 3 introduces the characteristics of collision accidents between merchant ships and fishing vessels. Section 4 describes the results and discussion in this study. Finally, the conclusions are presented in Section 5.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collection of Accident Data

To ensure the authenticity and accuracy of the analysis, all statistical data were obtained from the publicly released reports and documents issued by the Maritime Safety Administration of the Ministry of Transport of the People’s Republic of China. A total of 142 investigation reports on collision accidents between merchant ships and fishing vessels in China’s coastal waters between 2014 and 2025 were selected for this study. These accidents resulted in 432 fatalities or missing persons.

2.2. Causes of Collision Accidents

Based on systems engineering theory, factors affecting maritime safety can be broadly categorized into four types: human factors, ship factors, environmental factors, and management factors. Each category can be further decomposed into more specific causal elements [4,21].

Human factors refer to direct causes rooted in human error, such as misjudgment, violation of operational procedures, and other unsafe acts by crew members. Ship factors include direct technical and physical causes, such as unseaworthy vessels or defective equipment. Environmental factors encompass external conditions like visibility and complexity of the navigation environment. Management factors relate to deficiencies in the safety management system prior to the collision accident, including inadequate regulations, unclear responsibilities, and insufficient oversight. In line with the investigation reports of collisions between merchant ships and fishing vessels in China’s coastal waters (2014–2025), this study defines: Human factors as unsafe acts by crew members; Ship factors as unsafe conditions of the vessel or cargo; Environmental factors as weather and navigational conditions; Management factors as shortcomings in safety management, rules, and regulations.

2.3. Reference and Comparison Sequences

Based on the accident investigation reports, the annual number of valid collision accidents between merchant ships and fishing vessels was selected as the reference sequence, denoted as X0. Sixteen causal factors were selected as comparison sequences, including: X1 (failure to maintain a proper lookout), X2 (failure to adopt a safe speed), X3 (improper emergency response), X4 (incompetent crew), X5 (insufficient ship manning), X6 (ship unseaworthiness), X7 (ship equipment failing to meet requirements), X8 (poor visibility), X9 (complex navigation environment), X10 (failure to correctly display signal lights), X11 (ship navigating beyond the approved sea area), X12 (illegal fishing operations), X13 (failure to comply with narrow channel navigation regulations), X14 (incorrect use of navigation equipment), X15 (inadequate ship safety management), X16 (poor communication between vessels). These factors are summarized in Table 1. Table 2 presents the annual frequency of each causal factor from 2014 to 2025.

Table 1.

Causal factors of collision accidents between merchant ships and fishing vessels.

Table 2.

Cause Matrix of collision accidents between merchant ships and fishing vessels from 2014 to 2025.

2.4. Methods

GRA is a statistical method for measuring the degree of correlation between various factors in a system. It judges the tightness of the relationship between different sequences by analyzing the geometric shapes of sequence curves, where the degree of proximity between curves reflects the relational grade between the corresponding sequences, enabling the determination of the order of strength of correlation between each contributing factor and accidents. The basic idea of GRA is to convert the discrete behavioural observation values of system factors into piecewise continuous polyline curves through linear interpolation and then construct a model for measuring the correlation degree based on the geometric characteristics of these polylines. In this model, the closer the geometric shapes of the polylines, the higher the relational grade between the corresponding sequences, and vice versa. GRA is widely applied in comprehensive evaluation with universal applicability. It also possesses advantages such as a small required sample size, reliable results, and simple operation.

2.5. Calculation Steps of GRA

The GRA procedure is conducted as follows:

(1) Determine the reference sequence and comparison sequences.

(2) Perform dimensionless processing. Since sequences may have different units, dimensionless treatment is necessary to ensure comparability. Common methods include initial-value normalization, standardization, and mean-value normalization. In this study, mean-value normalization is applied to the original data to derive normalized sequences.

wherein, denotes the original comparison sequence; denotes the average value of the i-th data sequence; denotes the result after dimensionless processing.

(3) Difference processing

wherein, denotes the absolute difference sequence; denotes the result of the reference sequence after dimensionless processing; denotes the result of the comparison sequence after dimensionless processing.

(4) Calculate the two-level maximum difference and minimum difference .

wherein, and denote the maximum value and minimum value of the absolute differences in each sequence, respectively.

(5) Calculate the grey relational coefficient

wherein, denotes the grey relational coefficient; denotes the distinguishing coefficient, which is usually set to 0.5; denotes the number of rows in the sequence matrix; denotes the number of columns in the sequence matrix.

(6) Calculate the correlation degree.

wherein, denotes the correlation degree; denotes the number of evaluation factors.

3. Characteristics of Collision Accidents

3.1. Types of Accident Levels and Injuries

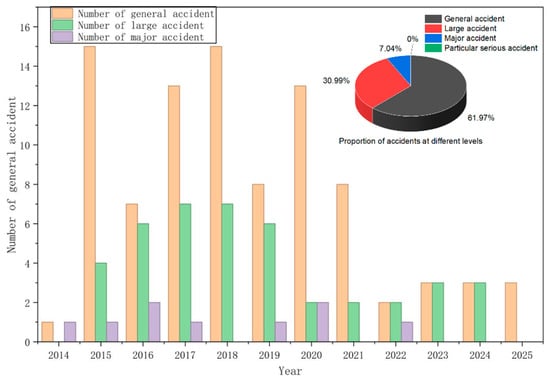

The accident severity of 142 collision accidents between merchant ships and fishing vessels was classified according to China’s Measures for the Statistics of Water Traffic Accidents [4], a particularly serious accident refers to an accident that causes more than 30 deaths (including missing persons), a major accident refers to an accident that causes more than 10 deaths (including missing persons) but less than 30 deaths (including missing persons), a large accident refers to an accident that causes more than 3 deaths (including missing persons) but less than 10 deaths (including missing persons), a general accident refers to an accident that causes more than 1 death but less than 3 deaths (including missing persons) or serious injuries to more than 1 but less than 10 people, or a direct economic loss of more than 1 million yuan but less than 10 million yuan. Figure 1 presents the statistical distribution of these accidents by grade from 2014 to 2025. As shown, general-grade accidents constituted the majority, accounting for 61.97% of the total. Major-grade accidents followed, representing 33.99% of cases. This distribution highlights a characteristic of such collision accidents: their tendency to result in serious consequences. Notably, since 2019, the numbers of both general-grade and major-grade accidents have demonstrated an overall downward trend, suggesting a significant improvement in the safety situation regarding collision accidents between merchant ships and fishing vessels in China’s coastal waters.

Figure 1.

Statistics of collision accident levels between merchant ships and fishing vessels within China’s coastal waters from 2014 to 2025.

As illustrated in Figure 2, the annual trend in the number of collision accidents broadly aligns with the trend in fatalities (including missing persons). The year 2017 recorded the highest number of fatalities at 72, constituting 16.7% of the total. The peak in the number of collision accidents occurred in 2018, with 22 accidents accounting for 15.5% of the total. However, over the most recent four-year period (2022–2025), both the total number of collision accidents and the associated fatalities have shown a consistent decline. During these years, the annual proportion of fatalities remained below 10% of the cumulative total, indicating a positive and sustained trend in the prevention and control of such maritime collisions.

Figure 2.

Collision Accidents of between merchant ships and fishing vessels within China’s coastal waters from 2014 to 2025.

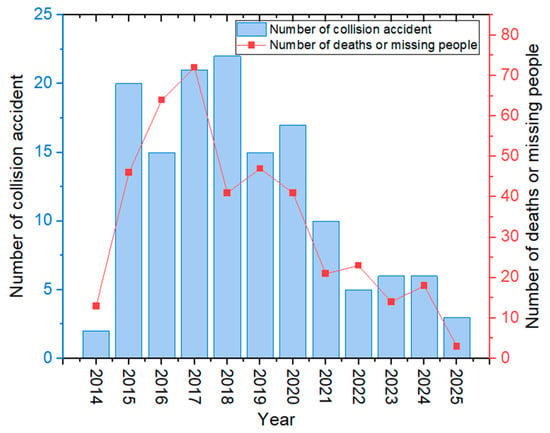

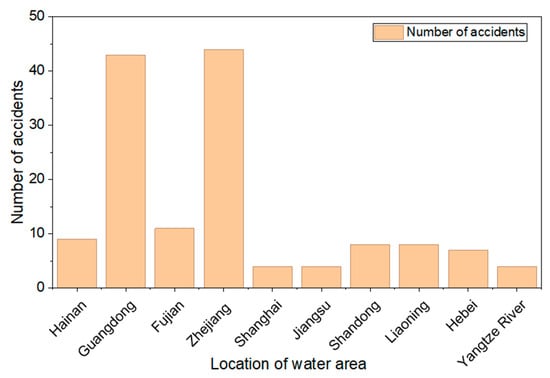

3.2. Time of Accident Occurrence

The frequency of collision accidents between merchant ships and fishing vessels in China’s coastal waters was analyzed based on the timing of occurrence, with results presented in Figure 3. As shown in the figure, January recorded the highest number of accidents, with 18 cases accounting for 12.7% of the total, followed by April and September, each with 17 cases. The number of accidents was relatively low in February and from May to July, averaging 5.25 collision accidents per month. February coincides with the Chinese Spring Festival, during which the fishing activities are reduced. In March, following the Lunar New Year holiday, industrial and commercial activities resume, leading to a surge in cargo demand and increased maritime traffic, which raises the probability of collision accidents. April precedes the annual fishing moratorium in China’s coastal waters, a period characterized by high fishing intensity and correspondingly elevated collision risks. Starting in May, the fishing moratorium takes effect, dramatically reducing fishing vessel activity and resulting in a notable decline in collision accidents. From mid- to late August, the moratorium ends and fishing operations intensify, contributing to a rise in collisions from August through October. In December and January, there is frequent cold wave activity along the coast of China, and the winter is foggy with poor visibility. Therefore, the harsh navigation environment increases the probability of collisions between merchant ships and fishing vessels.

Figure 3.

Statistics of months and times of collision accidents between merchant ships and fishing vessels within China’s coastal waters from 2014 to 2025.

A separate frequency analysis was conducted based on the time of day of accident occurrence, using two-hour intervals, also summarized in Figure 3. The results indicate that collision accidents occur predominantly in the early morning, with the 02:00–04:00 period representing the peak. In contrast, accidents between 06:00 and 20:00 were fewer and more concentrated, averaging 12.6 incidents. The 02:00–04:00 window corresponds to a period of heightened crew fatigue and reduced alertness, during which lapses in watchkeeping are more likely. Additionally, limited visibility at night combined with complex navigational conditions further elevates the risk for both merchant ships and fishing vessels.

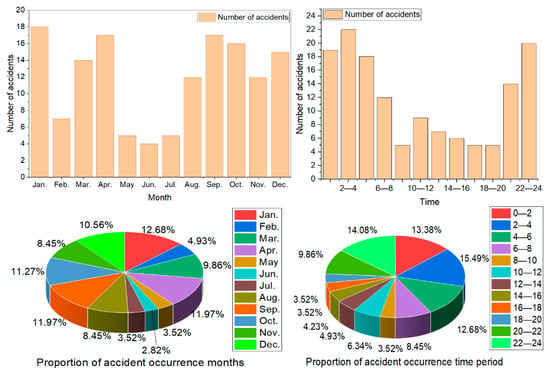

3.3. Location of Accidents

A frequency distribution analysis of collision accidents between merchant ships and fishing vessels was conducted based on the maritime areas where the accidents occurred, with the results presented in Figure 4. As shown, between 2014 and 2025, the coastal waters of Zhejiang and Guangdong provinces recorded the highest number of such collision accidents in China, with 44 and 43 accidents, respectively, which account for 30.99% and 30.28% of the total accidents. As major maritime hubs, both provinces experience dense shipping traffic in their coastal and inland waterways. The high frequency of collision accidents in these regions is attributable to multiple factors, including the presence of numerous coastal islands, complex navigational conditions, and the influence of severe weather events [1]. Particularly high-risk zones such as the Pearl River Estuary and the waters around Zhoushan port are notably prone to collision accidents. Furthermore, the abundant fishery resources in the coastal areas of Guangdong and Zhejiang lead to intensive fishing vessel activity. These combined factors contribute to the pronounced concentration of collision accidents between merchant ships and fishing vessels in these regions.

Figure 4.

Statistics of the water area of collision accidents between merchant ships and fishing vessels within China’s coastal waters from 2014 to 2025.

The top seven water areas with the highest collision frequencies were selected for further analysis. Figure 5 illustrates the annual variation in accident numbers within these waters. It can be observed that while Guangdong and Zhejiang waters had a relatively high and fluctuating total number of accidents, an overall decreasing trend is evident over the years. For the waters of Fujian, Hebei, Hainan, Shandong, and Liaoning, most accidents occurred prior to 2019, and these regions have also shown a general decline in the number of collision accidents in recent years.

Figure 5.

Statistics in high incidence water areas of collision accidents between merchant ships and fishing vessels within China’s coastal waters from 2014 to 2025.

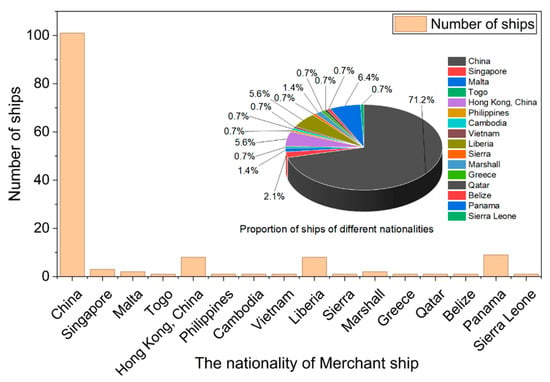

3.4. Types and Quantities of Vessels Involved in Accidents

Figure 6 presents a statistical analysis of the nationalities of merchant ships involved in collision accidents. Chinese-flagged ships constituted the overwhelming majority, with 101 vessels representing 71.13% of the total. These were followed by vessels registered in Hong Kong (China), Liberia, and Panama, with 8, 8, and 9 ships, respectively, collectively accounting for 17.16% of cases. Aside from Chinese and Hong Kong registrations, Liberia and Panama are commonly recognized as flag-of-convenience (FOC) states. The substantial number of vessels registered under these flags explains their notable presence in collision accidents between merchant ships and fishing vessels. Furthermore, FOC regimes typically impose minimal restrictions on crew employment and exercise limited oversight over vessel operations and management, indirect factors that may contribute to an increased risk of collision with fishing vessels.

Figure 6.

Statistics in merchant ships of different nationalities involved in collision accidents.

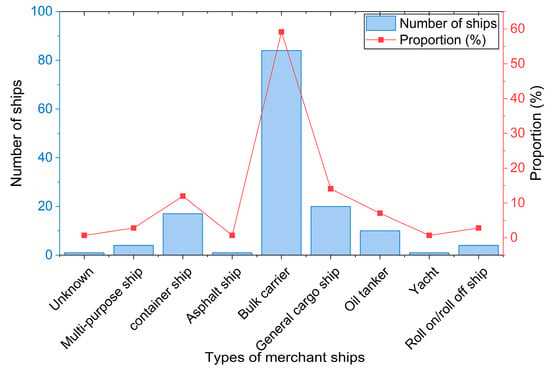

As shown in Figure 7, dry cargo ships represented the most frequently involved vessel type, with 84 ships (59.15%) constituting the majority of collision accidents between merchant ships and fishing vessels. General cargo ships followed with 20 vessels (14.08%), and container ships with 17 vessels (11.97%). Tankers, multi-purpose vessels, and Ro-Ro ships accounted for 10, 4, and 4 ships, respectively. These figures reveal a distinct pattern in vessel types involved in such collision accidents, with dry cargo, general cargo, and container ships being the most prevalent—particularly dry cargo vessels. This predominance can be attributed to the large number and widespread operational presence of such ships within China’s current merchant fleet. Additionally, cargo vessels generally sail at relatively higher speeds and often rely on autopilot systems, which may elevate their susceptibility to collisions with fishing vessels.

Figure 7.

Statistics in merchant ships of different ship types involved in collision accidents.

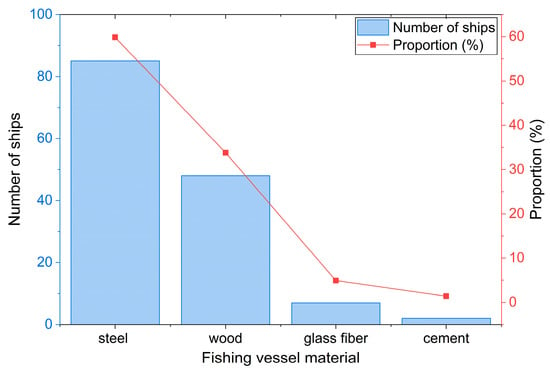

As illustrated in Figure 8, steel-hulled fishing vessels constituted the largest proportion of fishing vessels involved in collision accidents, accounting for 59.86% of the total incidents. Additionally, wooden fishing vessels were involved in 48 collisions, representing approximately 33.8% of such accidents. Notably, wooden vessels exhibit a higher tendency to capsize following collisions, leading to a relatively greater number of fatalities. The underlying reasons for this pattern are as follows: wooden fishing vessels are generally characterized by smaller dimensions, lower tonnage, and reduced structural strength, rendering them more susceptible to capsizing or severe damage upon impact with merchant ships. Furthermore, crews aboard wooden fishing vessels often demonstrate inadequate attention to maritime safety management, frequently lack formal training, and occasionally engage in illegal fishing activities, thereby increasing their vulnerability to collisions with nearby navigating merchant ships.

Figure 8.

Statistics on fishing vessels of different hull material involved in collision accidents.

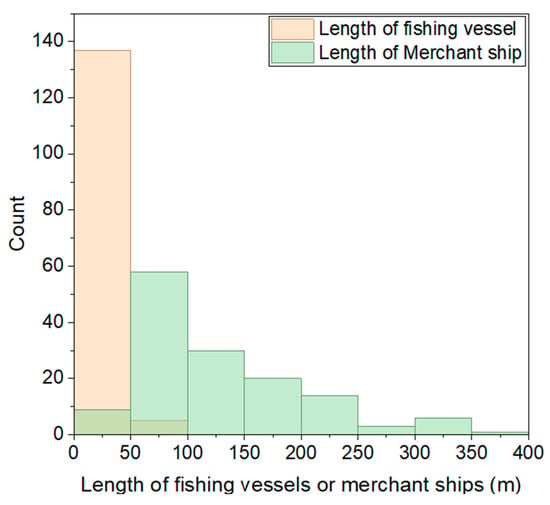

3.5. Length and Speed of Ships

Figure 9 presents a statistical analysis of the lengths of merchant ships and fishing vessels involved in collision accidents. The average length of the involved fishing vessels was 27.7 m, with 137 vessels (approximately 96.48% of the total) measuring less than 50 m in length. In contrast, the average length of the involved merchant ships was 130 m. Among these, merchant ships measuring between 50 and 100 m constituted the largest group, totaling 75 vessels (about 52.82%), followed by 30 vessels (approximately 21.43%) in the 100–150 m range. Those shorter than 50 m or longer than 250 m accounted for a relatively small proportion. Most collision accidents involved fishing vessels shorter than 50 m. Despite ongoing safety training for fishermen, the frequency of such accidents has not decreased. Kim et al. [22] identified vessel condition as the most influential indirect factor, suggesting that hull material and length may be correlated with collision occurrence.

Figure 9.

Statistics on the length of merchant ships and fishing vessels involved in collision accidents.

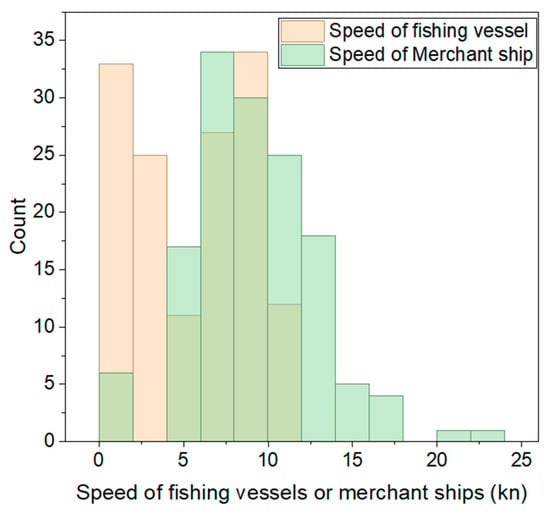

As shown in Figure 10, the speeds of vessels involved in collisions were also analyzed. The average speed of fishing vessels was 5.38 knots. Among these, 61 vessels (42.96%) were travelling between 6 and 10 knots—typically under navigation mode—while 58 vessels (40.85%) operated at less than 4 knots, most of which were either anchored or engaged in fishing activities. The average speed of merchant ships was 9.11 knots. The majority—89 vessels (62.68%)—were travelling between 6 and 12 knots, followed by 18 vessels (11.97%) in the 12–14 knot range and 17 vessels (12.68%) between 4 and 6 knots.

Figure 10.

Statistics on the speed of merchant ships and fishing vessels involved in collision accidents.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Correlation Analysis Results

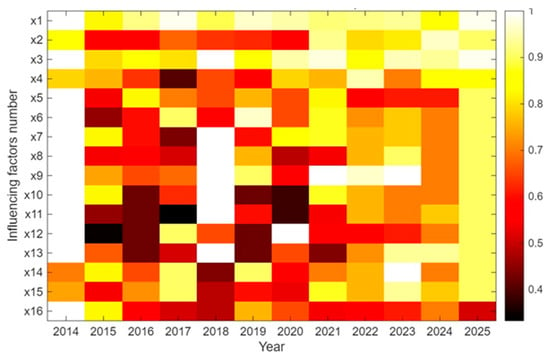

Figure 11 presents a grey relational matrix diagram, which visualizes the results of the grey relational analysis to intuitively illustrate the degree of correlation between each comparative sequence and the reference sequence. The correlation degree ranges from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating stronger correlations. It should be noted that the relatively limited data for 2014 and 2025 may contribute to generally higher correlation values across multiple factors in those years. For the period from 2015 to 2024, the matrix uses a colour gradient to represent correlation strength: darker shades denote weaker correlations, while lighter shades indicate stronger ones. As shown in the figure, in 2023, X14 and X9 exhibit strong correlations, whereas X5 and X16 show relatively weak correlations. Similarly, in 2021, X3 and X9 are strongly correlated, while X13 demonstrates a comparatively weaker association.

Figure 11.

Matrix diagram of causal factor correlation coefficient.

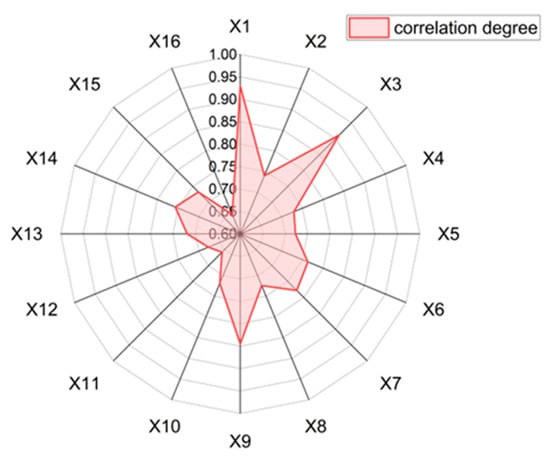

As shown in Figure 12, the correlation strength between the causative factors and the effective collision accident count (X0) is ranked in the following order:

X1 > X3 > X9 > X7 > X6 > X14 > X2 > X15 > X4 > X8 > X5 > X10 > X13 > X12 > X11 > X16.

Figure 12.

The correlation degree of causative factors.

This order indicates the relative influence of each contributing factor on X0, with X1 having the strongest effect, followed sequentially by X3, X9, X7, X6, X14, X2, X15, X4, X8, X5, X10, X13, X12, X11, and finally X16.

As shown in Figure 12, X1, X3, and X9 are identified as the key contributing factors to collision accidents between merchant ships and fishing vessels.

Among these, X1 (failure to maintain a proper lookout) exhibits the highest correlation degree, at 0.93. Many collision accidents occur due to inadequate lookout, which prevents vessels from fully assessing the surrounding situation and leads to accidents [15]. In particular, failure to keep a proper lookout on fishing vessels is often the primary cause of collisions. Negligence by watchkeepers, resulting in delayed detection of nearby fishing vessels or misjudgment of risks, frequently leads to untimely evasive actions and ultimately to collisions [11].

Meanwhile, X3 (improper emergency response) also shows a relatively high correlation degree of 0.91. When merchant ships and fishing vessels are in a close-quarters situation, inappropriate maneuvers by either the stand-on or give-way vessel can directly cause a collision [12]. Studies indicate that inadequate emergency response on fishing vessels significantly exacerbates casualties in maritime accidents [1,4,23]. In encounters between merchant ships and fishing vessels, improper responses by crew members tend to aggravate outcomes that might otherwise have been mitigated.

Additionally, X9 (complex navigation environment) correlates strongly with collision occurrence, with a degree of 0.84. Complex navigational conditions often increase the frequency of ship collisions. In such environments, both merchant ships and fishing vessels may fail to adequately comprehend the situation, thereby raising the risk of collision. External navigational factors—such as high traffic volume, increased traffic density, and severe weather—have been shown to significantly elevate the probability of ship collisions [23,24]. Thus, a complex navigation environment is a key trigger for collision accidents between merchant ships and fishing vessels.

4.2. Suggestions for Preventing Collision Accidents Between Merchant Ships and Fishing Vessels

With the closed of the summer fishing moratorium along China’s coasts, a significant concentration of fishing vessels returns to operation. This leads to overlapping navigation and operational zones between merchant shipping and fishing fleets in offshore waters, considerably complicating the maritime environment and elevating the risk of collisions. Over the past decade, such accidents have recurred in China’s coastal regions, often with severe consequences. The substantial disparity in vessel size means that even minor contact can result in critical damage, capsizing, or sinking of fishing vessels, leading to serious casualties and total losses. To address this pressing issue, the following targeted measures are proposed:

- (1)

- Formalization of Lookout Protocols. When transiting or approaching areas of high fishing activity, merchant ship watchkeepers must dedicate full attention to navigational duties. A formal lookout responsibility matrix should be established to clearly delineate the roles and boundaries among the Officer of the Watch (OOW), the dedicated lookout, and supporting personnel. Core requirements regarding scope, frequency, and procedures for information relay should be integrated into the ship’s Safety Management System (SMS). This creates a control model characterized by clear individual accountability, standardized positional procedures, and effective assessment mechanisms.

- (2)

- Enhancement of Proactive Communication. Effective communication must be established during encounters. Merchant and fishing vessels should utilize Very High Frequency (VHF) channels to collaboratively exchange information regarding navigational intentions, maneuvering constraints, and observed environmental conditions. A standardized procedure of “declaring intent first, confirming plans second, and synchronizing operations last” should be adopted to prevent misunderstandings from unilateral decisions. Where feasible, a minimum safe distance of one nautical mile should be maintained.

- (3)

- Rigorous Collision Avoidance Preparedness. During voyage planning, merchant ship routes should avoid known fishing concentration areas as a primary strategy. When transit is unavoidable, vessels should implement enhanced precautions including manual steering, engine room standby, and a safe speed while maintaining heightened vigilance. These measures are designed to mitigate risks posed by the sudden, evasive maneuvers fishing vessels may undertake to protect their gear.

- (4)

- Prudent Navigation in Complex Environments. In fishing-dense areas, while fishing vessels as operational units may claim certain navigational priority, they are also obliged to avoid core merchant shipping lanes actively. Conversely, merchant ships should proactively divert around fishing operation zones well in advance and must not attempt to force passage through them.

- (5)

- Reinforcement of Company Safety Management: Shipping companies must diligently fulfil their safety oversight responsibilities. This includes strengthening the dynamic monitoring of vessels and watchkeeping arrangements, intensifying audits of Bridge Resource Management (BRM) and navigational watch practices, ensuring crew compliance with international regulations and corporate safety protocols, and continuously enhancing crew safety awareness and professional competency.

- (6)

- Intensification of Specialized Theoretical Training. Maritime training curricula should incorporate dedicated theoretical modules on preventing merchant-fishing vessel collisions. This includes emergency collision avoidance techniques in complex environments, case study analyses of typical accidents to highlight critical operational lessons, and practical skill development (encompassing maneuvering decision-making, cooperative communication, and emergency response) using maritime simulation systems.

- (7)

- Strengthening of Inter-Agency Collaborative Oversight. A joint supervision and information-sharing platform between maritime and fisheries authorities should be established. This platform would enable real-time synchronization of data such as vessel registrations, AIS tracks, fishing permits, and violation records. A collaborative supervision process featuring “risk early warning, on-site verification, and closed-loop rectification” is recommended. High-risk encounter zones should be identified via big data analysis, followed by targeted joint law enforcement operations.

- (8)

- Promotion of Technological Empowerment. Technological upgrades should be advanced [25], including enhancing intelligent AIS and BeiDou Navigation Satellite System functionalities, mitigating interference from fishing gear markers, and optimizing radar identification capabilities for non-steel hull fishing vessels to enable automatic dynamic monitoring and collision warning. Furthermore, a unified maritime spatial information service platform should be developed, integrating data on fishing zone distributions, operational schedules, and real-time vessel movements. Merchant ships could access dynamically updated “fishing activity heatmaps” via this platform for voyage planning and execution. Based on vessel-specific parameters (type, draft, navigational constraints), the system could automatically recommend optimal routes that avoid areas of high fishing activity frequency.

5. Conclusions

This study analyzes collision accidents between merchant ships and fishing vessels in China’s coastal waters from 2014 to 2025. The findings indicate that fishing vessels involved in such accidents face a high risk of sinking, frequently resulting in severe crew casualties and total losses. Among the 142 recorded collision accidents, 432 individuals were killed or reported missing. The collision accidents in these waters exhibit the following characteristics:

- (1)

- The period from August to October, immediately following the end of the summer fishing moratorium, shows the highest density of fishing vessel activity.

- (2)

- The nighttime window between 02:00 and 04:00 is a high-incidence period for collision accidents.

- (3)

- The majority of involved merchant ships are dry cargo ships, accounting for 59.15% of cases.

- (4)

- Guangdong and Zhejiang are identified as high-risk areas within China’s coastal waters.

Furthermore, this study applies the grey relational analysis method to identify key contributing factors to collision accidents between merchant ships and fishing vessels, providing a basis for formulating preventive measures. Through the construction of an analytical framework and case-based calculations, three factors are determined to be critical: X1 (failure to maintain a proper lookout), X3 (improper emergency response), and X9 (complex navigation environment). X1 (failure to keep a proper lookout) exhibits the highest correlation degree (0.93) and is identified as the most direct cause of collision accidents. To mitigate such accidents, it is recommended that when merchant ships navigate through or approach waters with dense fishing activity, the OOW should employ all available means to maintain a proper lookout, comprehensively assess the surrounding navigation situation, and thoroughly evaluate collision risks. X3 (improper emergency response) ranks second, with a correlation degree of 0.91. It is advised that merchant ships operating in areas of high fishing vessel density should proceed at a safe speed, strictly adhere to the “early, substantial, wide, and clear” avoidance principle, and strive to maintain a minimum encounter distance of over 1 nautical mile. X9 (complex navigation environment), along with X8 (poor visibility), are also significant influencing factors. In complex navigational conditions or under poor visibility, merchant ships should reduce speed, enhance lookout efforts, closely monitor the movements of nearby fishing vessels, and prevent them from entering visual blind zones.

In summary, by focusing on these key causal factors and understanding their mechanisms, it is possible to prevent or reduce the occurrence of collision accidents between merchant ships and fishing vessels. However, the GRA method can only calculate the correlation degree of key factors and cannot directly determine causal relationships. Therefore, combining other methods such as Granger test will help to analyze the impact of causal factors on collision accidents between merchant ships and fishing vessels in more detail.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.D.; Methodology, X.G.; Software, B.L., X.G. and C.D.; Validation, X.G. and C.D.; Formal analysis, B.L. and X.G.; Investigation, B.L. and X.G.; Resources, C.D.; Data curation, B.L. and C.D.; Writing—original draft, B.L. and X.G.; Writing—review and editing, B.L. and X.G.; Supervision, C.D.; Project administration, C.D.; Funding acquisition, C.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, grant number 3132025132.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Yang, J.; Sun, Y.; Song, Q.; Ma, L. Laws and preventive methods of collision accidents between merchant and fishing vessels in coastal area of China. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2023, 231, 106404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chen, N.; Wu, B.; Soares, C.G. Human and organizational factors analysis of collision accidents between merchant ships and fishing vessels based on HFACS-BN model. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2024, 249, 110201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Lei, J.; Wang, Z.; Zheng, D.; Yu, C.; Chen, M.; He, W. Risk Analysis and Visualization of Merchant and Fishing Vessel Collisions in Coastal Waters: A Case Study of Fujian Coastal Area. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; Guo, X.; Gong, Y. Research on Coupling Mechanisms of Risk Factors for Collision Accidents Between Merchant Ships and Fishing Vessels Based on the NK Model. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subash, T.D.; Pradeep, A.S.; Joseph, A.R.; Jacob, A.; Jayaraj, P.S. Intelligent Collision Avoidance system for fishing boat. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 24, 2457–2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sur, J.M.; Kim, D.J. Comprehensive risk estimation of maritime accident using fuzzy evaluation method–Focusing on fishing vessel accident in Korean waters. Asian J. Shipp. Logist. 2020, 36, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhao, F.; Liu, J.; Liu, S.; Song, J. Assessing the collision risks of merchant and fishing ships based on behavioral patterns: A case study in Qingdao Port. Ocean Eng. 2025, 329, 121122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gai, X.; Zhang, Q.; Hu, Y.; Wang, G. A Fuzzy Fusion Method for Multi-Ship Collision Avoidance Decision-Making with Merchant and Fishing Vessels. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uğurlu, F.; Yıldız, S.; Boran, M.; Uğurlu, Ö.; Wang, J. Analysis of fishing vessel accidents with Bayesian network and Chi-square methods. Ocean Eng. 2020, 198, 106956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugurlu, H.; Cicek, I. Analysis and assessment of ship collision accidents using Fault Tree and Multiple Correspondence Analysis. Ocean Eng. 2022, 245, 110514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Q.; Ma, X.; Zhang, R.; Qiao, W. Analyzing the Causation of Collision Accidents Between Merchant and Fishing Vessels in China’s Coastal Waters by Integrating Association Rules and Complex Networks. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chen, N.; Jiang, J.; Soares, C.G.; Wu, B. A data-driven AcciMap-BN model for risk factor analysis of collisions between merchant ships and fishing vessels. Marit. Policy Manag. 2025, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong-Ye, P.; Su-Hyung, K.I.M. A study on risk factors analysis of distant water fishing vessels using Bayesian networks. J. Korean Soc. Fish. Ocean Technol. 2025, 61, 254–270. [Google Scholar]

- Eliopoulou, E.; Papanikolaou, A.; Voulgarellis, M. Statistical analysis of ship accidents and review of safety level. Saf. Sci. 2016, 85, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, P.; Mou, J.; Chen, L.; Li, M. Critical causation factor analysis in ship collision accidents with complex network. Ocean Eng. 2025, 315, 119837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayrulnizam, N.A.I.M.; Kamis, A.S.; Sulaiman, M.S.; Kamarudin, R.N.H.R. Review and Analysis of the Collision Incident between Cargo Ship Edmy and Fishing Vessel Tornado: Extracting Lessons from a Case. Asian J. Res. Educ. Soc. Sci. 2023, 5, 375–383. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.C.; Lee, H.S. Application of grey relational analysis to evaluate port safety in Keelung harbor. J. Ship Prod. Des. 2010, 26, 206–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Y.; Zhao, H.; Yang, J.; Sheng, J. Water Traffic Safety Evaluation Based on the Grey Correlation Grade Analysis. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2014, 571, 295–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Cao, Y.; Tang, M.; Wang, Y. Research on Ship Collision Risk Analysis Based on Grey relational analysis Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Big Data Technologies, Qingdao, China, 23–25 September 2022; pp. 154–159. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, C.; Sui, H.; Yang, Z.; Chen, J.; Yang, M. Weighted grey relational analysis of main engine faults on ships in port areas. In Advances in Maritime Technology and Engineering; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024; pp. 217–223. [Google Scholar]

- Sur, J.M.; Kim, Y.J. Multi-Criteria Model for Identifying and Ranking Risky Types of Maritime Accidents Using Integrated Ordinal Priority Approach and Grey Relational Analysis Approach. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Lee, S.H.; Ryu, K.J.; Lee, Y.W. Analysis of accidents of fishing vessels caused by human elements in Korean sea area. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, J.; Liao, S.; Wu, B.; Yang, D. Exploring effects of ship traffic characteristics and environmental conditions on ship collision frequency. Marit. Policy Manag. 2020, 47, 523–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventikos, N.P.; Papanikolaou, A.D.; Louzis, K.; Koimtzoglou, A. Statistical analysis and critical review of navigational accidents in ad-verse weather conditions. Ocean Eng. 2018, 163, 502–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, R.; Wu, Y.; Chen, W.; Zhang, J. Design of intelligent collision avoidance system for fishing vessels based on AIS. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 7th International Conference on Cloud Computing and Intelligent Systems (CCIS), Xi’an, China, 7–8 November 2021; pp. 334–337. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.