Abstract

This study aimed to develop bioactive toothpaste and compare its remineralization potential on initial enamel lesions with toothpaste containing other active agents. Sixty extracted human maxillary incisors were randomly assigned to six groups: Group EXP (Experimental toothpaste), Group SRP (Sensodyne Repair & Protect), Group ZAC (Zubio Active Carbon Whitening), Group GTM (GC Tooth Mousse), Group CSP (Colgate Sensitive Pro-Relief), and Group ASS (Artificial saliva, control). Artificial caries were induced by immersion in a demineralization solution for three days. Specimens then underwent a seven-day pH-cycling protocol, during which toothpaste was applied twice daily for two minutes. Analyses were performed at baseline, post-demineralization, and post-remineralization using ATR-FTIR, SEM-EDS, and Vickers micro-hardness testing. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS (version 27.0, IBM Corp., Chicago, IL, USA). All treatment groups, except the control, showed significant microhardness recovery after remineralization, with the highest increase in group CSP followed by group EXP (p < 0.05). Granular surface deposits were observed, most pronounced in groups SRP and GTM (p < 0.05). Calcium and phosphorus contents increased in all groups (p < 0.05), with calcium highest in group GTM and phosphorus in group EXP. The mineral-to-matrix ratio increased in all groups, and a statistically significant difference was identified between the experimental toothpaste (EXP) and the other toothpaste formulations (p < 0.05). It is hypothesized that pomegranate seed essential oil may exhibit a remineralizing effect due to its content of anthocyanidins, anthocyanins, and various polyphenolic compounds. Therefore, the development of a toothpaste with enhanced remineralization potential was targeted by incorporating pomegranate seed essential oil into the experimental formulation in addition to bioactive agents such as bioactive glass, hydroxyapatite, and casein phosphopeptide.

1. Introduction

Dental caries is one of the most common chronic diseases worldwide and, if left untreated, may progress to tooth loss [1,2]. Acid production resulting from the metabolism of dietary carbohydrates by cariogenic bacteria, primarily Streptococcus mutans, disrupts the demineralization–remineralization balance in the oral environment, which eventually results in loss of dental hard tissue as caries lesions [3,4]. Preventive strategies against dental caries, a multifactorial disease, are mainly based on antimicrobial approaches and the enhancement of remineralization [4]. The aims of preventive dentistry include preventing the onset of caries, arresting, and repairing initial lesions, while remineralization of non-cavitated initial carious lesions represents a simple, rapid, cost-effective, comfortable, and conservative treatment approach for patients [5,6]. To promote these remineralization processes, toothpastes, varnishes, gels, and mouth rinses containing different active ingredients are commonly used [7,8,9].

Therefore, the development of such therapeutic methods and materials has become one of the major goals of current dental research. In this context, preventive and regenerative dentistry approaches have been introduced [1,4]. Hydroxyapatite (HA) is the main component of hard tissues in the human body, such as enamel, dentin, and bone, which has been proven to be highly biocompatible and bioactive [6,10]. Due to its strong affinity for enamel, it is easily absorbed onto tooth surfaces [10]. Nanosized HA particles fill surface and subsurface microdefects of worn enamel, repairing minor structural defects [11]. Milk-derived phosphoproteins called “Casein phosphopeptides” (CPPs) stabilize ions such as phosphate (P) and calcium (Ca), maintaining high levels of soluble ions in saliva necessary for remineralization [12]. Amorphous calcium phosphate (ACP), an important precursor in apatite formation, is reactive in aqueous media, leading to the release of P and Ca ions followed by their transformation into crystalline phases [7].

Bioactive glass (BAG) is one of the biocompatible materials with a composition like dental enamel, frequently incorporated into oral care products such as toothpastes [9]. BAG particles precipitate on the enamel surface, occluding surface porosities [13]. The hydroxycarbonate apatite formed on their surface enables chemical bonding with dental tissues, promoting hard tissue mineralization [14]. Studies have demonstrated that BAG can remineralize enamel and dentin while also exhibiting antimicrobial properties against oral bacteria [15,16].

Recently, the importance of natural and biocompatible products in dentistry has increased [17,18,19,20]. Plant-derived products are widely used in dentistry due to their antibacterial, antiviral, and anti-inflammatory activities [21]. Compared with synthetic agents, natural products are regarded as safer, readily available, cost-effective, and associated with fewer side effects [20,22]. Pomegranate, which has one of the least researched essential fatty acids in the literature, contains anthocyanins, anthocyanidins, flavonoids, phenolic acids, and other phytochemicals with beneficial health effects [23]. Pomegranate seed essential oil is rich in polyphenols, proteins, lipids, and bioactive compounds, exhibiting antimicrobial, antioxidant, immunomodulatory, and anticancer properties [24]. However, to the best of our knowledge, there are no studies in the literature reporting the use of pomegranate seed essential oil as a component of toothpaste formulations. Pomegranate seed extract, owing to its polyphenol content, promotes dentin biomodification, enhances mineral deposition, and represents a promising alternative for the management of carious lesions [19].

The interaction between natural bioactive compounds, particularly polyphenols, and the enamel mineral phase is a growing area of interest in preventive dentistry. Polyphenols are known to exert a protective effect by forming a stable organic–inorganic complex on the enamel surface. These compounds can act as collagen cross-linkers in dentin and potentially influence the remineralization kinetics of enamel by modulating the calcium-to-phosphate ratio and stabilizing the newly formed hydroxyapatite crystals. Biomodification of the dental substrate with such polyphenols would not only enhance mechanical properties but also create a favorable environment for ion precipitation, thereby increasing the resistance of the enamel to acidic challenges [24]. Pomegranate peel extract, which also has a higher level of polyphenols, may also act as an exogenous source of calcium and phosphorus ions due to its intrinsic mineral content. Pomegranate seed EO and peel extract facilitate ion accumulation on the enamel surface by forming an organic pellicle composed of monomeric and polymeric polyphenols, which can function as a calcium carrier, increasing local calcium concentrations and thereby promoting the remineralization of subsurface lesions [24,25,26].

The aim of this study is to develop a novel toothpaste containing hydroxyapatite, casein phosphopeptide, bioactive glass, and pomegranate seed essential oil (EO) and to investigate in vitro the effects of this formulation, along with commercially available toothpastes containing different active ingredients, on the remineralization of artificially induced initial enamel carious lesions in permanent human teeth. The null hypothesis (H0) of this study was that there would be no statistically significant difference in the remineralization effects of toothpastes with different active compositions on artificially induced initial enamel carious lesions.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Medical Research of Ege University (Decision No: 24-10T/39).

2.1. Sample Preparation

In this study, 60 extracted human maxillary incisors were obtained from patients aged 18–75 years who were admitted to the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Ege University, and had extractions performed for orthodontic or periodontal reasons. The required sample size was calculated using the G*Power software (Version 3.1.9.7, Heinrich Heine University, Düsseldorf, Germany). Based on data from similar studies [8,11], a repeated-measures ANOVA was selected for the six-group design, with an effect size (f) of 0.5315, an F-value of 4.0153, a significance level (α) of 0.05, and a statistical power of 99.87%, determining a minimum of 10 specimens per group. All teeth were examined under a light microscope (Leica DFC295, Wetzlar, Germany), and those presenting fractures, cracks, caries, discoloration, or structural anomalies were excluded. Soft and hard tissue remnants on the root surfaces were mechanically removed with hand instruments. For disinfection, a 0.1% thymol solution was used. Until the initiation of the experimental procedures, the specimens were stored in distilled water at +4 °C.

The collected teeth were separated at the cemento-enamel junction using a diamond disc and pumice (Acurata GmbH, Freinberg, Austria) under water cooling. The crowns were fixed in acrylic resin (Duradent, Istanbul, Turkey) with the buccal surfaces oriented outward and parallel to the base (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Preparation of samples.

In order to obtain a flat and smooth surface and to remove the superficial aprismatic enamel layer, the prepared specimen surfaces were ground for 10 s under water using a polishing machine (Presi Megapol P320, Spectrographic Ltd., Grenoble, France). Subsequently, standardized windows measuring 4 × 4 mm were created to designate the analysis area, while the remaining surfaces were coated with acid-resistant nail varnish (Flormar Nail Polish, Palermo, Italy).

2.2. Grouping of the Specimens

The samples were randomly assigned to six groups by a blind researcher, with ten specimens in each group. Microhardness testing was planned for three of the ten specimens, SEM/EDS analysis for three specimens, and ATR-FTIR analysis for the remaining four specimens. Figure 2 and Table 1 show the toothpastes and their contents used in the study:

Figure 2.

Materials (toothpastes) used in the study.

Table 1.

Contact tightness values (N) obtained from the study.

- Group EXP: Experimental toothpaste.

- Group SRP: Sensodyne Repair & Protect Toothpaste (Haleon, GSK, London, UK).

- Group ZAC: Zubio Active Carbon Whitening Toothpaste (Zubio, Istanbul, Turkey).

- Group GTM: GC Tooth Mousse (GC International, Tokyo, Japan).

- Group CSP: Colgate Sensitive Pro-Relief Toothpaste (Colgate-Palmolive Manufacturing, New York, NY, USA).

- Group ASS: Artificial saliva solution (Testonic Lab., Colin Farma, Istanbul, Turkey) (negative control).

2.3. Synthesis of Experimental Toothpaste

The experimental toothpaste formulation was developed at the research laboratory of Ege University Faculty of Dentistry under the supervision of experts in chemical engineering and food engineering. A total of 75 g of product was prepared in order to achieve optimal concentration according to the formula prepared by the experts. Commercial Zubio® (Zubio Ltd., Istanbul, Turkey) toothpaste was chosen as a base due to its inert herbal composition and lack of fluoride/remineralizing agents, which allowed for isolating the effects of BAG, HA, and EO while maintaining a stable toothpaste consistency. The formulation contained glycerin (10 g), hydrated silica (8 g), xylitol (5 g), hydroxyapatite (6 g), xanthan gum (1 g), distilled water (15 g), sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS, 1 g), calcium carbonate (5 g), magnesium sulfate (2 g), limonene (1 g), peppermint oil (1 g), pomegranate seed essential oil (3.75 mL), casein phosphopeptide (CPP) powder (7.5 g), and bioactive glass powder (3.75 g).

The nanoscale size of bioactive glass particles enhances their bioactivity and remineralization effects (Sepulveda ve ark. 2002, Vollenweider ve ark. 2007). Bioactive glass inserted in (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA) consisted of both micro- and nano-sized particles (Batch No: 915084) as well as 10% wt nHA dispersion <200 µm (Batch No: 702153). In the experimental toothpaste, hydroxyapatite (HA) was specifically incorporated to act as a primary remineralizing agent. Due to its structural and chemical similarity to natural enamel hydroxyapatite, it was intended to serve as a biomimetic scaffold to promote the deposition of calcium and phosphate ions into the demineralized enamel porosities. Particles in the size range of 0.2–100 µm were directly incorporated into the toothpaste formulation, whereas larger particles were excluded due to their higher abrasive potential. Smaller particle sizes significantly increase the specific surface area, which enhances the dissolution rate and the subsequent release of calcium and phosphate ions necessary for remineralization. Bioactive glass particles with smaller diameters have a higher rate to facilitate a more rapid formation of a hydroxycarbonated apatite layer due to their higher reactivity [13,15]. To enhance dissolution potential, pre-treated particles were immersed in distilled water for 24 h before use. Active agent ratios and mixing protocols were standardized as follows: Bioactive glass powder was incorporated at 5% w/w (3.75 g). Following pre-treatment, the mixture was blended using a conventional mixer for at least 10 min or with a vacuum mixer (Whip Mix VPM2, Practicon, Greenville, NC, USA) for at least 5 min.

CPP powder was added at 10% w/w (7.5 g). A 3 min manual premixing step was performed prior to mixing with a conventional mixer for at least 10 min or a vacuum mixer for at least 5 min. Pomegranate seed essential oil was added to the experimental paste to provide lubricating efficacy, MMP inhibition, and antimicrobial activity. EO obtained by supercritical fluid extraction was inserted at 5% v/v (approximately 3.75 mL) and mixed using a vacuum mixer for at least 5 min or a medium-speed conventional mixer for at least 8 min. Vacuum mixing was carried out using the same vacuum mixing unit.

Quality control procedures included sensory evaluation, particle detection, spreadability, pH measurement, and moisture analysis. Ten volunteers evaluated the product for color, odor, taste, and texture, reporting a white to greyish-white color, soft texture, aromatic odor and taste, and satisfactory cleaning ability. For the sharp or hard particle test, a 3 g sample was pressed into a thin layer and assessed for detectable particles. In the spreadability evaluation, a 2 g sample was placed between two glass plates for 5 min, and the diameter of the spread area was recorded. pH was determined by suspending 1 g of toothpaste in 100 mL of distilled water, following ISO 11609:2017 [27]. Moisture content was calculated by drying a 5 g sample at 105 °C and determining the weight difference before and after drying. The experimental formula was prepared under aseptic conditions and tested immediately after formulation to ensure the stability of the bioactive agents. Between the experimental stages, the toothpaste was stored in opaque, airtight containers at 4 °C to prevent the oxidation of essential oils and to inhibit potential microbial growth.

2.4. Preparation of the Demineralization/Remineralization Solutions

The demineralization solution was prepared with the following composition: 2.2 mM CaCl2, 2.2 mM KH2PO4, 0.05 M acetic acid, 1.0 M KOH, pH 4.4. The remineralization solution was prepared with 1.5 mM CaCl2, 0.9 mM NaH2PO4, 0.15 mM KCl, 1.0 M KOH, pH 7.0. Both solutions were prepared at the Department of Analytical Chemistry, Faculty of Pharmacy, Ege University, and stored at +4 °C in sealed glass bottles.

2.5. Artificial Caries Formation and Toothpaste Application

To induce artificial caries, the specimens were immersed in daily refreshed demineralization–remineralization solutions and incubated at 37 °C for three days to establish a cycle, which mimics the oral environment (Figure 3). The specimens were kept in demineralization solution for 3 h, rinsed with distilled water, and then immersed in remineralization solution for 2 h. After rinsing again with distilled water, toothpastes were applied for 2 min using an applicator. Following rinsing, the specimens were once more placed in demineralization solution for 3 h, rinsed and treated with toothpaste for 2 min. During the remaining time, they were stored in remineralization solution at 37 °C. The specimens were placed into a fresh solution of 30 mL per specimen after each rinsing procedure. This cycle was repeated for seven consecutive days. Toothpaste applications were carried out randomly by a blind operator who was unaware of the group allocation [28].

Figure 3.

Demineralization–remineralization cycle.

2.6. Microhardness Measurement

A Vickers microhardness tester (Model HVM-2, Shimadzu Corp, Tokyo, Japan) was used in this study, applying a load of 200 g for 15 s. Microhardness (MH) measurements were performed at three different stages for each specimen: initial, after demineralization, and after toothpaste application (remineralization) and recorded in Vickers Hardness. For each specimen, measurements were obtained from three distinct points spaced at least ≥0.20 mm apart, and the mean value was calculated.

2.7. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Energy-Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy (EDS) Analysis

Prior to SEM imaging, specimens underwent a systematic dehydration process to prevent structural artifacts under high vacuum. The samples were dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol concentrations (50% to 100%) for 20 min at each step, followed by final drying in a desiccator for 24 h. The exposed 4 × 4 mm areas of the specimens were examined using a SEM-EDS system (Thermo Scientific Apreo S, Waltham, MA, USA) at magnifications of 1000× g, 5000× g, and 10,000× g, with an accelerating voltage of 20 kV and an average working distance of 15 mm. The weight % of calcium and phosphorus was calculated using the EDS detector of the system. Analyses were conducted at three stages: initial, after demineralization, and after toothpaste application (remineralization).

2.8. Attenuated Total Reflectance–Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR) Analysis

ATR-FTIR (Perkin Elmer Spectrum Two, Springfield, IL, USA) was performed in absorbance mode using a diamond crystal, with a resolution of 4 cm−1 and a spectral range of 4000–450 cm−1. Analyses were conducted at three stages: initial, after demineralization, and after toothpaste application (remineralization). The peak areas (AUC) corresponding to carbonate, phosphate, and amide I + water bands in the enamel structure were calculated, and the mineral/matrix ratio (phosphate AUC/amide I + water AUC) was determined. Microhardness testing, SEM-EDS procedures, and ATR-FTIR measurements were performed and analyzed in E.U. Metallurgy Analysis Labs (MATAL) by a blind operator. Spectra were subjected to linear baseline correction and normalized to the peak area of the phosphate band (1032 cm−1) to ensure comparability across all specimens.

2.9. Statistical Analyses

Statistical analysis of the data was performed using SPSS software (version 27.0, IBM Corp., Chicago, IL, USA) with a 95% confidence interval. Normality was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Post-demineralization and post-remineralization values were compared using the Wilcoxon Signed Rank test. Differences among multiple stages were evaluated with the Kruskal–Wallis test, and pairwise comparisons between groups were performed using the Mann–Whitney U test. The level of significance was set at α = 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Microhardness Results

In all groups, a decrease in MH was observed after demineralization, followed by a significant increase after remineralization (Table 2). However, none of the groups regained the initial MH levels (p > 0.05). To further quantify the clinical significance, Cohen’s d effect sizes were calculated for microhardness recovery (remineralization vs. demineralization). All toothpaste groups exhibited very large effect sizes (d > 1.2), with the highest within-group recovery observed in group CSP (d = 3.64), followed by group SRP (d = 1.85) and ETP (d = 1.17). Furthermore, EXP demonstrated large superiority over the group ASS (control) (d = 2.49).

Table 2.

Microhardness values (VHN) obtained from each stage.

When the remineralization–demineralization delta MH values were evaluated, groups SRP, GTM, and CSP showed significant differences compared with the control group (Table 3). Among all groups, group CSP exhibited the greatest increase in MH after remineralization, followed by groups SRP, GTM, and EXP. All of the toothpastes except ZAC exhibit significant differences in delta MH changes when compared with the control.

Table 3.

Demineralization–remineralization delta microhardness comparison.

3.2. SEM-EDS Analysis Results

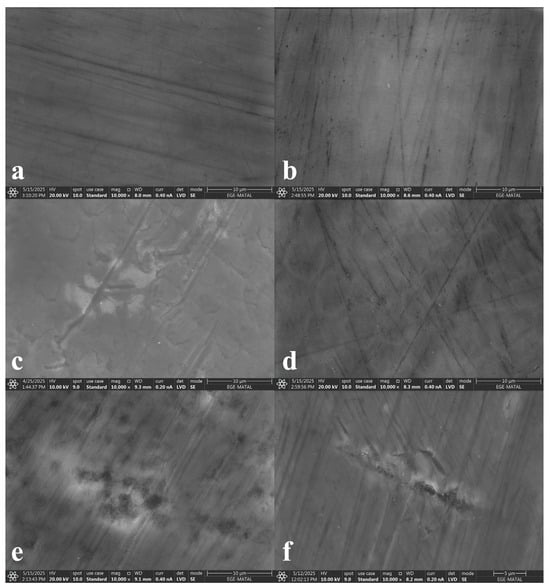

SEM images revealed that at the initial stage, the enamel surface appeared intact and smooth; however, scratch marks were detected in some specimens (Figure 4). In addition, microcracks were only observed in groups ZAC and ASS.

Figure 4.

Initial-stage SEM images ((a) group EXP, (b) group SRP, (c) group ZAC, (d) group GTM, (e) group CSP, (f) group ASS).

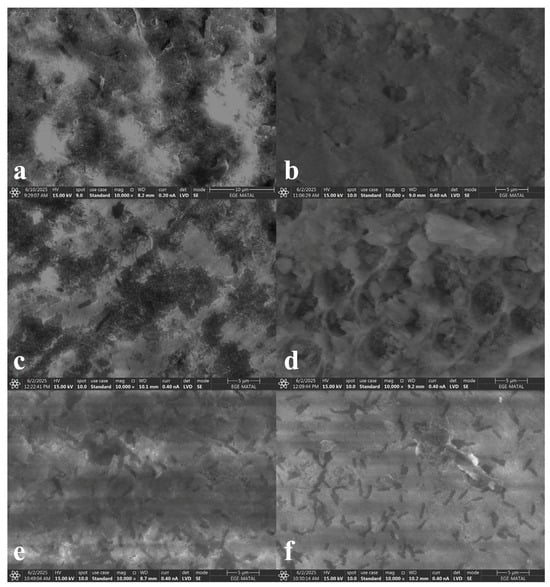

After demineralization, an increase in surface roughness and a honeycomb-like appearance were observed (Figure 5). Group EXP exhibited similar results only with group ZAC.

Figure 5.

Demineralization-stage SEM images ((a) group EXP, (b) group SRP, (c) group ZAC, (d) group GTM, (e) group CSP, (f) group ASS).

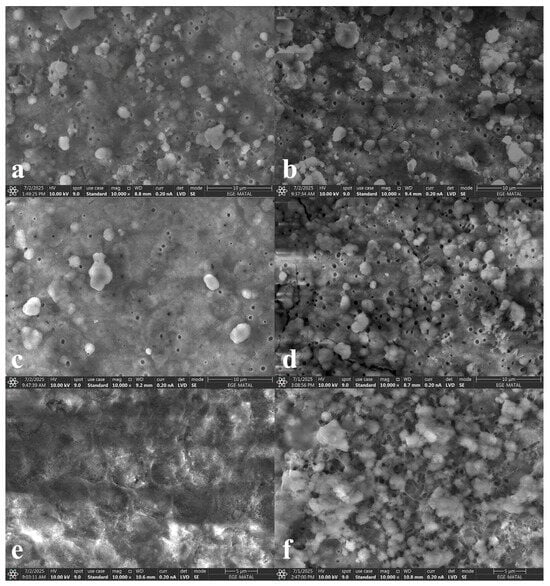

Following remineralization, scattered heterogeneous deposits were detected (Figure 6). In groups EXP, SRP, and GTM, dense deposits and spherical structures were observed, whereas group ZAC exhibited fewer and sparser deposits. Group CSP showed the least amount of deposition (Figure 6e).

Figure 6.

Remineralization-stage SEM images ((a) group EXP, (b) group SRP, (c) group ZAC, (d) group GTM, (e) group CSP, (f) group ASS).

At the demineralization stage, the amounts of Ca and P decreased in all groups. After toothpaste application, a significant increase in the weight % of both Ca and P was observed across all groups (Table 4). When examining the delta weight % values of the P element between the remineralization and demineralization stages, the order from highest to lowest was as follows: group EXP, group SRP, group CSP, group GTM, group ASS, and group ZAC (Table 5). When examining the delta weight % values of the Ca element between the remineralization and demineralization stages, the order from highest to lowest was as follows: group GTM, group CSP, group SRP, group EXP, group ASS, and group ZAC (Table 5).

Table 4.

Calcium and phosphate changes in weight (%) ratios during the stages.

Table 5.

Ca and P remineralization–demineralization delta weight changes comparison.

3.3. ATR-FTIR Analysis Results

The intensity of the phosphate v3 and carbonate v2 bands is directly proportional to the degree of mineralization. In contrast, the intensity of the amide I + water band is inversely proportional to the degree of mineralization. The Mineral/Matrix ratio (M/M) is defined as the ratio of the phosphate band to the amide band, and its increase is directly proportional to the degree of mineralization. In all groups, the phosphate and carbonate AUC decreased after demineralization and increased after remineralization (Table 6). The amide I + water AUC increased after demineralization and decreased after remineralization (Table 6). Furthermore, the negative control group (ASS) also exhibited a slight increase in the mineral/matrix ratio during the remineralization phase. However, this gain was insignificantly lower (p > 0.05) than that of the experimental and commercial toothpaste groups, representing a baseline ion deposition rather than an active therapeutic remineralization.

Table 6.

Mean AUC and mineral/matrix values obtained from ATR-FTIR analysis.

When examining the delta values of the M/M between the Demineralization/Remineralization stages, the order from highest to lowest was as follows: group GTM, group ZAC, group CSP, group EXP, group ASS, and group SRP (Table 7).

Table 7.

Remineralization–demineralization delta M/M comparison.

4. Discussion

Dental caries, which adversely affects both functional and aesthetic aspects, is among the most common chronic health problems today [3]. White spot lesions, the earliest stage of caries, can be remineralized with timely intervention using appropriate materials and techniques [29,30]. For this purpose, various remineralizing agents and treatment strategies have been developed to repair HA crystals that constitute enamel tissue and to restore lost ions [30]. Furthermore, as scientific advances in oral health continue, the exploration of new approaches that can enhance the benefits of oral hygiene practices is becoming increasingly important. In particular, innovations in toothpaste formulations play a crucial role in maintaining and improving oral health at the community level, owing to their affordability and accessibility [31]. The aim of this study was to formulate an innovative toothpaste containing a combination of different agents with remineralization potential and to investigate the effects of this experimental formulation, as well as commercially available toothpastes with different active components, on initial enamel carious lesions. According to the results obtained, both experimental toothpaste and study groups presented an increase in mineral/matrix concentrations and a decrease in microhardness, as well as similar surface appearances. While the experimental toothpaste exhibited similar characteristics to various study groups, especially groups SRP, ZAC, CSP, and across all evaluated parameters, it also showed markedly different results compared to some groups. This is thought to be primarily due to the differences in the proportion of bioactive material and essential oils incorporated into its formulation compared to the other products. Therefore, the null hypothesis of the study was partially accepted.

The caries formation process begins with the dissolution of HA crystals on the enamel surface, followed by the loss of Ca and P ions, and typically presents as a chalky white appearance [1,32]. In this study, after the demineralization stage—a critical step for inducing artificial caries—an opaque white surface, disruption of the crystal structure, decreased Ca and P content, and reduced MH values were observed, supporting the successful induction of artificial caries. Contemporary dentistry not only aims to treat existing carious lesions but also to arrest the progression of initial lesions, promote natural healing processes, and delay invasive procedures as much as possible [5]. Within this scope, treatment strategies focus on reducing lesion depth, increasing the MH of enamel-like tissues, and restoring mineral content to enhance biological resistance against caries [33]. In this study, all toothpastes tested increased both the MH and mineral content of demineralized enamel surfaces. These findings suggest that the toothpastes used may contribute to strengthening resistance against caries. However, regarding the spectroscopic findings, the observed variations in baseline AUC values across groups at the initial stage are attributed to the inherent biological heterogeneity of natural human enamel. Factors such as the donor’s age, individual mineralization levels, and slight variations in enamel surface morphology can influence the initial spectroscopic footprint. To account for this variability and ensure a standardized comparison of the chemical changes, the study utilized Mineral/Matrix ratios and normalized Delta values rather than absolute intensities.

Caseins are the main proteins in milk and can be used in the production of bioactive peptides. They exhibit several biological activities, including antimicrobial, antioxidant, and immunomodulatory properties [34,35]. CPPs are compounds structurally and functionally similar to salivary phosphoproteins and have been employed in in-vitro studies on enamel remineralization [16]. Since CPP is considered a promising agent, it was incorporated into the formulation of experimental toothpaste. Casein phosphopeptide–amorphous calcium phosphate (CPP-ACP) is a nanocomplex formed from CPP and ACP, which, in the oral environment, maintains calcium and phosphate ions in a biologically available and stable form, thereby supporting the remineralization of dental enamel [34]. Toothpastes containing CPP-ACP have been shown in various in-vitro and in-vivo studies to significantly prevent and reverse demineralization [8,36,37]. Owing to its strong remineralization potential, a CPP-ACP–containing toothpaste was included as one of the experimental groups in this study, and similar results to those reported in the literature were obtained.

Among remineralizing agents, fluoride ions have been used for many years and are considered the gold standard [38]. However, due to various side effects such as fluorosis and hypomineralization, the dosage of fluoride cannot be increased. Therefore, studies have investigated its combined use with other agents in remineralization, most commonly with fluoride ions yielding promising results [39,40]. For this reason, a toothpaste containing a combination of F and BAG was included in this study. Recent studies have demonstrated that BAGs possess remineralization-supporting effects while enhancing the micro-structural properties of the enamel tissue and in certain cases providing antimicrobial effect to the toothpaste [39,40,41,42,43,44]. Considering that antibacterial activity will be achieved with EO in the experimental toothpaste, BAG was incorporated into the formulation of the experimental toothpaste in this study. The effectiveness of BAGs in this field is attributed to their ability to release ions such as Ca, phosphate (PO4), and F, which play a critical role in the remineralization process [31]. The release of sodium ions increases the local pH, which promotes Ca and PO4 precipitation and thereby supports the formation of HA crystals. Through these properties, BAG not only contributes to buffering the acidic environment but also initiates a repair process similar to the natural tooth structure by supporting the reformation of HA crystals on demineralized surfaces [31]. The findings of this study are that BAG containing toothpaste groups increased mineral levels consistent with the literature.

HA is a material of particular interest due to its morphological and structural similarity to enamel apatite crystals, as well as its biocompatibility and high bioactivity [6]. The large surface area of nanosized HA particles facilitates the binding of Ca and PO4 ions to the enamel surface and the filling of voids within demineralized lesions. Through these properties, HA serves as an effective template during the remineralization process [11]. Recent studies have demonstrated that nano-hydroxyapatite (nHA)-based formulations can enhance enamel hardness, restore resistance against acidic erosion, and possess significant remineralization potential [45,46,47,48]. In a clinical study conducted by Scribante et al. [49], it was reported that two different hydroxyapatite-containing toothpastes could reduce caries risk. The incorporation of HA into the experimental formulation was intended for the specific purpose of biomimetic remineralization. As supported by Scribante et al. [49] and Pepla et al. [50], nanosized hydroxyapatite particles possess a high affinity for demineralized enamel surfaces, acting as a mineral reservoir that facilitates the repair of the apatite structure and restores the lost inorganic content. Owing to this remineralization potential, a HA containing toothpaste (ZAC) was included in this study and HA was selected as one of the active agents incorporated into the formulation of experimental toothpaste. In contrast to the findings of this study, some studies have reported that a single application of nHA containing toothpastes resulted in a significant increase in calcium concentration within the remineralization solution [8]. In addition, Ebadifar et al. [48] investigated the effects of two toothpastes, with and without nHA, and compared on artificially demineralized teeth using MH measurements. After demineralization, the MH values decreased, and following toothpaste application, a partial increase was observed. The increase in MH values was found to be greater in the nHA containing toothpaste group [48]. These results are consistent with the findings of this study.

Arginine bicarbonate is an amino acid capable of adhering to mineral surfaces. Upon dissolution of its calcium carbonate content, the released Ca can be utilized for remineralization, while carbonate release may contribute to an increase in pH. In addition, arginine can be metabolized by non-pathogenic bacteria into ammonia, thereby helping to neutralize plaque acids on the tooth surface [51]. Several studies have reported that toothpastes containing 1.5% arginine were more effective in promoting remineralization than fluoride-only formulations and also have positive effects on remineralization when compared with other ingredients [38,52]. In the light of this evidence, arginine-containing toothpaste was included in this study. In a remineralization study comparing 1% sodium fluoride toothpaste with an arginine-containing formulation, MH analysis was used to evaluate efficacy, and the arginine-containing toothpaste was found to have a greater effect on increasing MH [53]. Consistent with these findings, in this study, the arginine-containing group exhibited the highest increase in MH values.

In addition, a notable finding of this study was that while the experimental toothpaste (EXT) group demonstrated the highest increase in phosphorus (P) levels via EDS analysis, it did not exhibit the highest recovery in surface microhardness compared to commercial formulations like CSP. This discrepancy highlights the critical distinction between mineral deposition and structural integration. The high P increase in the ETP group suggests a rapid precipitation of phosphate-rich minerals on the enamel surface, likely facilitated by the high reactivity of BAG and the matrix-stabilizing effect of pomegranate seed EO. However, the conversion of these surface deposits into a mature, organized crystalline apatite structure which is responsible for increasing mechanical hardness “is a time-dependent” process. Commercial formulations such as CSP, which utilize different fluoride delivery systems, may promote a more rapid transition from amorphous mineral deposition to organized crystalline integration within the study’s 15-day timeframe. Thus, the EXT group’s performance represents significant potential for mineral reservoir formation, though longer treatment periods might be required for these minerals to fully enhance the structural microhardness to the levels seen in specialized commercial benchmarks [38].

Plant-derived natural products such as essential oil (EO) have long been used in traditional medicine. Due to their antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant properties, as well as their high biodegradability and low toxicity, they represent eco-friendly bioactive compounds that can serve as alternatives to synthetic agents in oral health applications [54]. In an in vitro study investigating the remineralization capacity of natural and bioactive materials on initial carious lesions, six groups were established: Group I: CPP-ACP, Group II: rosemary oil, Group III: ginger + honey, Group IV: ginger + honey + cocoa, Group V: grape seed extract, and Group VI: control (remineralization solution). MH testing and DIAGNOdent were used for analysis. In terms of remineralization capacity, the ranking was as follows: grape seed extract > ginger + honey + cocoa > ginger + honey > rosemary oil > GC Tooth Mousse [55]. Similar to these findings, Zero et al. [17] conducted an in situ study to evaluate the remineralization effects of mouth rinses containing only EOs (0.064% thymol, 0.092% eucalyptol, 0.060% methyl salicylate, 0.042% menthol), only fluoride (100 ppm sodium fluoride), or a combination of EO + fluoride. Their results showed that the EO + fluoride rinse provided the greatest increase in surface microhardness [17,56].

Although studies investigating the remineralization effects of essential oils are limited, available findings indicate that natural products are worthy of further investigation for remineralization applications. Pomegranate seed essential oil possesses a rich profile of bioactive compounds, particularly polyphenols, in addition to its protein and lipid content [24]. Polyphenols contribute to dentin biomodification, and a concentration of 15% has been shown to enhance mineral deposition [19]. Based on the existing literature, the experimental toothpaste formulated in the present study was designed to promote remineralization by incorporating bioactive glass (BAG), hydroxyapatite (HA), casein phosphopeptide (CPP), and pomegranate seed essential oil into its composition. Pomegranate seed EO was incorporated into the experimental formulation due to its high concentration of punicic acid and polyphenols. In dentistry, polyphenols are recognized as natural cross-linkers that can stabilize the dental matrix and promote mineral deposition [25]. Furthermore, its potent antimicrobial activity against Streptococcus mutans provides a therapeutic advantage in preventing biofilm formation, which is crucial for the success of remineralization therapies [57]. Therefore, a 15% concentration of pomegranate seed essential oil was selected for inclusion in the formulation of the experimental toothpaste. While the experimental toothpaste demonstrated promising results in terms of microhardness and FTIR analyses, the specific biochemical and antimicrobial contributions of pomegranate seed EO to the remineralization process were not directly measured in this study. The potential role of punicic acid and polyphenols as cross-linkers is suggested based on analogous findings in existing literature [24,25].

In a study conducted by Silaghi-Dumitrescu et al. [58], to evaluate the remineralization process in human enamel, an experimental gel containing extracts specifically from quince (Cydonia oblonga), pineapple (Ananas comosus), and nHA was tested alongside toothpaste containing CPP-ACP and sodium fluoride. To investigate the protective effects of these remineralizing agents on enamel, Ultraviolet and Visible Light Absorption Spectroscopy was performed in conjunction with ATR-FTIR analysis. It was suggested that the tested products may help prevent or arrest early enamel demineralization; however, no significant differences were found compared with the control group [58]. Similarly, in this study, no significant differences were observed between the toothpaste groups and the control group when analyzing peak areas.

Bioactive materials have long been incorporated into dental applications, particularly within restorative materials such as resin composites and glass ionomers, and their integration into toothpaste formulations represents an extension of this evolving technology [56]. By refining factors such as particle size, surface properties, and chemical composition, they become feasible to better address enamel erosion, caries formation, or to enhance remineralization in patients with compromised enamel. Furthermore, combining bioactive glass particles with remineralizing agents such as nHA and CPP-ACP may amplify their clinical effectiveness. Nanotechnological strategies that enable controlled particle size and encapsulation can support a sustained and stable release of functional ions, thereby prolonging their benefits, strengthening the remineralization process, and increasing enamel resistance to decay and erosion. Overall, innovations in both material design and delivery methods are expected to further advance the clinical performance of bioactive glass–based toothpaste formulations.

A remineralization study conducted by Joshi et al. [59], including BAG, nHA, tricalcium phosphate, grape seed extract, and F (1000 ppm) groups, MH analysis was used to evaluate the agents’ efficacy. The greatest increase was observed in the BAG group, followed by tricalcium phosphate, nHA, and grape seed extract [55,59]. The greater MH increase in the BAG group compared with the nHA group is compatible with the findings of this study. Similarly, in a study comparing the effects of remineralizing agents, including nHA, NovaMin (BAG), calcium sucrose phosphate, and Pro-Argin, on the surface properties of demineralized enamel using microhardness and scanning electron microscopy and energy dispersive X-ray micro analysis (SEM-EDX) testing, calcium sucrose phosphate demonstrated the most pronounced increase in MH, followed by BAG, nHA, and Pro-Argin. SEM images showed increased surface roughness for all agents, while EDX results revealed, consistent with this study, a significant increase in Ca and P levels across all groups. However, P content was found to be higher in the calcium sucrose phosphate and BAG groups.

In the study by Suryani et al. [8], which aimed to evaluate and compare the effects of toothpastes containing fluoride-CPP-ACP, nHA, and BAG on the MH of demineralized enamel surfaces, MH and SEM analyses were employed. All toothpastes increased MH values, with the greatest improvement observed in the BAG-containing group. SEM images showed that, after remineralization, the surface layer was dense in the BAG group, dispersed and homogeneous in the fluoride-CPP-ACP group, and sparse and irregular in the nHA group. These observations are consistent with the findings of this study, which indicates that the remineralization potential of nHA was lower compared to fluoride-CPP-ACP and BAG [8]. In this study, MH analysis revealed that, compared with initial measurements, all specimens exhibited a decrease in MH values after demineralization. Following remineralization, MH values increased in all groups but did not reach the initial levels. This outcome is consistent with the results of some studies reported in the literature [39,60].

In a similar study conducted by Salinovic et al. [61], the effects of three different remineralizing materials (CPP-ACP/F, nHA, F) on enamel were investigated using microhardness testing along with SEM-EDS analysis. Consistent with the methodology used in this study, measurements were performed at three stages: initial, after demineralization, and after remineralization. The group treated with CPP-ACP/F showed significantly higher mean MH values compared with the other two groups. SEM analysis revealed irregular patterns and porosities in all specimens, while EDS results indicated an overall increase in mineral content, with the highest levels observed in the CPP-ACP/F group. These findings demonstrate that CPP-ACP/F exerts a superior remineralization effect on enamel compared with the other two materials, which is consistent with the findings of this study, where the CPP-ACP group showed a greater increase in Ca and P elements compared with the HA group.

In another study evaluating the remineralization potential of two toothpastes based on CPP-ACP and BAG, SEM images showed that deposits on enamel surfaces were smaller and amorphous in the CPP-ACP group, while larger and angular deposits were observed in the BAG group [62]. EDX analysis revealed significant increases in P and Ca levels in the CPP-ACP group, while in the BAG group, calcium, phosphorus, silicon, and zinc levels significantly increased. These findings suggest that both CPP-ACP- and BAG-based toothpastes are capable of supporting remineralization on enamel surfaces, but the remineralization efficacy of BAG may be higher [62,63]. According to the EDS analysis in this study, the CPP-ACP group was found to be more effective in increasing P levels, whereas the BAG group was more effective in increasing Ca levels.

Within the limitations of this study, an experimental toothpaste formulation including BAG and pomegranate EO was developed. The effects of this experimental formulation, together with various commercially available toothpastes containing different active ingredients, on the remineralization of artificially induced initial enamel carious lesions were investigated in vitro using multiple analytical methods. Although a separate long-term microbiological stability assay was not conducted, the high pH environment created by Bioactive Glass (BAG) and the inherent antimicrobial properties of pomegranate oil are reported to contribute to the self-preserving nature of such formulations. Another limitation of the present study is the absence of surface roughness (profilometric) analysis. While the in vitro nature of this research cannot fully replicate the complex dynamics of the human oral environment, such as the protective role of the acquired pellicle and the buffering capacity of stimulated saliva, microhardness (MH) and mineral content (EDS) provide significant data on the success of the remineralization process. Furthermore, future studies incorporating surface roughness measurements before and after application, which offer a more comprehensive understanding of the topographic changes on the enamel surface and a dynamic biofilm model such as bacterial accumulation testing that investigates the interaction between the experimental toothpaste with pomegranate seed EO and cariogenic microorganisms, are planned to validate the long-term clinical efficacy and durability of the remineralization achieved by this novel formulation.

5. Conclusions

Among the tested groups in this experimental study, the arginine- and fluoride-containing toothpaste demonstrated the greatest increase in MH. The experimental toothpaste group showed the highest increase in P levels, while the CPP-ACP group was the most effective in increasing Ca content. ATR-FTIR analysis revealed that all groups were able to enhance mineralization. Although the findings suggest that the experimental toothpaste exhibits promising remineralization potential, this study needs to be supported by more comprehensive and long-term in vitro and in vivo research due to its inability to fully replicate the oral environment, short application time, and the lack of biofilm models. In addition, further experimental studies are required to evaluate the safety of essential oils, determine their minimum effective doses, and assess their antimicrobial activities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.P.; formal analysis, C.P. and S.E.; methodology, C.P. and S.E.; investigation, N.N.K. and S.E.; validation, C.P.; resources, N.N.K.; data curation, C.P. and N.N.K.; writing—original draft, N.N.K.; writing—review and editing, C.P.; visualization, N.N.K.; supervision, S.E.; funding acquisition, C.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study is funded by Ege University Scientific Research Projects Department (Ege-BAP) with reference number ID: 32721.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all staff members of Ege University Faculty of Pharmacy and Faculty of Chemical Engineering who contributed to this study during the phases of solution preparation and chemical formulation of the experimental toothpaste.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- El Gezawi, M.; Wölfle, U.C.; Haridy, R.; Fliefel, R.; Kaisarly, D. Remineralization, regeneration, and repair of natural tooth structure: Influences on the future of restorative dentistry practice. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 5, 4899–4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitts, N.B.; Twetman, S.; Fisher, J.; Marsh, P.D. Understanding dental caries as a non-communicable disease. Br. Dent. J. 2021, 231, 749–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordoni, N.E.; Salgado, P.A.; Squassi, A.F. Comparison between indexes for diagnosis and guidance for treatment of 2dental caries. Acta Odontoloógica Latinoam. 2021, 34, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Li, F.; Ye, Y.; Zhang, X. Antimicrobial, remineralization, and infiltration: Advanced strategies for interrupting dental caries. Med. Rev. 2025, 5, 87–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochrane, N.J.; Cai, F.; Huq, N.L.; Burrow, M.F.; Reynolds, E.C. New approaches to enhanced remineralization of tooth enamel. J. Dent. Res. 2010, 89, 1187–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adel, S.M.; El-Harouni, N.; Vaid, N.R. White spot lesions: Biomaterials, workflows and protocols. Semin. Orthod. 2023, 29, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeshita, E.M.; Danelon, M.; Castro, L.P.; Cunha, R.F.; Delbem, A.C.B. Remineralizing potential of a low fluoride toothpaste with sodium trimetaphosphate: An in situ study. Caries Res. 2016, 50, 571–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryani, H.; Gehlot, P.M.; Manjunath, M.K. Evaluation of the remineralisation potential of bioactive glass, nanohydroxyapatite and casein phosphopeptide amorphous calcium phosphate fluoride based toothpastes on enamel erosion lesion—An ex vivo study. Indian J. Dent. Res. 2020, 5, 670–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekin, H.; Kırzıoğlu, Z. Herbal toothpastes and their use in children. BAUN Sağlık Bil. Derg. 2021, 10, 63–72. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, S.H.; Jang, S.O.; Kim, K.N.; Kwon, H.K.; Park, Y.D.; Kim, B.I. Remineralization potential of new toothpaste containing nano-hydroxyapatite. Key Eng. Mater. 2024, 309, 537–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitiello, F.; Tosco, V.; Monterubbianesi, R.; Orilisi, G.; Gatto, M.L.; Sparabombe, S.; Memé, L.; Mengucci, P.; Putignano, A.; Orsini, G.; et al. Remineralization efficacy of four remineralizing agents on artificial enamel lesions: SEM-EDS investigation. Materials 2022, 15, 4398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, E.C.; Cai, F.; Cochrane, N.J.; Shen, P.; Walker, G.D.; Morgan, M.V.; Reynolds, C. Fluoride and casein phosphopeptide-amorphous calcium phosphate. J. Dent. Res. 2008, 87, 344–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerruti, M.G.; Greenspan, D.; Powers, K. An analytical model for the dissolution of different particle size samples of Bioglass in TRIS-buffered solution. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 4903–4911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, O.H.; Kangasniemi, I. Calcium phosphate formation at the surface of bioactive glass in vitro. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1991, 25, 1019–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagasaki, R.; Nagano, K.; Nezu, T.; Iijima, M. Synthesis and characterization of bioactive glass and zinc oxide nanoparticles with enamel remineralization and antimicrobial capabilities. Materials 2023, 16, 6878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, K.; Hamba, H.; Miyayoshi, Y.; Ishizuka, H.; Muramatsu, T. In vitro remineralization of enamel with a solution containing casein and fluoride. Dent. Mater. J. 2021, 40, 1109–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zero, D.T.; Zhang, J.Z.; Harper, D.S.; Wu, M.; Kelly, S.; Waskow, J.; Hoffman, M. The remineralizing effect of an essential oil fluoride mouthrinse in an intraoral caries test. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2004, 135, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana, G.S.B.; Menezes, S.M.S.; Cordeiro, L.N.; Matos, F.J.A. Biological effects of pomegranate (Punica granatum L.), especially its antibacterial actions, against microorganisms present in the dental plaque and other infectious processes. In Bioactive Foods in Promoting Health: Fruits and Vegetables; Watson, R.R., Preedy, V.R., Eds.; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; Chapter 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eymirli, P.S.; Gültekin, İ.M.; Özler, C.Ö.; Özyürek, E.U. Evaluation of the efficacy of various remineralization agents and grape seed extract on microhardness and lesion depth of primary tooth enamel: An in vitro study. J. Dent. Res. Dent. Clin. Dent. Prospect. 2024, 18, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamh, R. Remineralization and antibacterial efficacy of different concentrations of aqueous stevia extract and green tea solutions in comparison with fluoride-based mouthwash on initial enamel carious lesion: An in vitro study. Egypt Dent. J. 2022, 68, 2855–2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiristioglu, Z.B.; Yanikoglu, F.; Alkan, E.; Tagtekin, D.; Gocmen, G.B.; Ilgin, C. The effect of dental paste with herbal content on remineralization and the imaging with fluorescent technique in teeth with white spot lesion. Clin. Exp. Health Sci. 2021, 11, 348–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.; Fu, C.; Zhang, D.; Li, M.; Zhou, X.; Gao, Y.; Lin, K.; Hu, B.; Zhang, K.; Cai, Q.; et al. Biomimetic remineralization of dental hard tissues via amyloid-like protein matrix composite with amorphous calcium phosphate. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2403233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galaz, P.; Valdenegro, M.; Ramírez, C.; Nuñez, H.; Almonacid, S.; Simpson, R. Effect of drum drying temperature on drying kinetics and polyphenol contents in pomegranate peel. J. Food Eng. 2017, 208, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshari, A.R.; Boroushaki, M.T.; Mollazadeh, H. Pomegranate seed oil: A comprehensive review on its therapeutic effects. Int. J. Pharm. Sci Res. 2016, 7, 1000–1013. [Google Scholar]

- Bedran-Russo, A.K.; Pauli, G.F.; Chen, L.; Castellan, C.S.; Phansalkar, R.S.; Nam, J.W.; McAlpine, J.; Leme, A.A.; Vidal, C.M. Dentin biomodification: Strategies, renewable resources and clinical applications. Dent. Clin. N. Am. 2014, 30, 62–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.S.; Farooq, I.; Alakrawi, K.M.; Khalid, H.; Saadi, O.W.; Hakeem, A.S. Dentin tubule occlusion potential of novel dentifrices having fluoride containing bioactive glass and zinc oxide nanoparticles. Med. Princ. Pract. 2020, 29, 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO Standard No. 11609:2017; Dentistry—Dentifrices—Requirements, Test Methods and Marking—Requirements with Guidance for Use. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Singhal, R.K.; Rai, B. Remineralization potential of three tooth pastes on enamel caries. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2017, 5, 664–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Yu, L.; Li, J.; Liu, Y. Comparison of therapies of white spot lesions: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, P.; Carvalho, T.; Gomes, A.; Veiga, N.; Blanco, L.; Correia, M.J.; Mello-Moura, A.C.V. White spot lesions: Diagnosis and treatment–a systematic review. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, P.S.; Pasha, M.B.; Rao, R.N.; Rao, P.V.; Madaboosi, N.; Özcan, M. A review on enhancing the life of teeth by toothpaste containing bioactive glass particles. Curr. Oral Health Rep. 2024, 11, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abou Neel, E.A.; Aljabo, A.; Strange, A.; Ibrahim, S.; Coathup, M.; Young, A.M.; Bozec, L.; Mudera, V. Demineralization–remineralization dynamics in teeth and bone. Int. J. Nanomed. 2016, 11, 4743–4763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monjarás-Ávila, A.J.; Hardan, L.; Cuevas-Suárez, C.E.; Alonso, N.V.Z.; Fernández-Barrera, M.Á.; Moussa, C.; Jabr, J.; Bourgi, R.; Haikel, Y. Systematic review and meta-analysis of remineralizing agents: Outcomes on white spot lesions. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moita, T.; Pedroso, L.; Santos, I.; Lima, A. Casein and casein-derived peptides: Antibacterial activities and applications in health and food systems. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtari, R.; Rezaei, M.; Kazemi Fard, M.; Dirandeh, E. Evaluation of antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of casein-derived bioactive peptides using trypsin enzyme. J. Food Qual. 2023, 2023, 1792917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, F.M.C.; Almeida, E.M.F.C.; Hannig, C.; Quinteiro, J.P.; Delbem, A.C.B.; Cannon, M.L.; Danelon, M. Biofilm modulation and demineralization reduction after treatment with a new toothpaste formulation containing fluoride, casein phosphopeptide-amorphous calcium phosphate, and sodium trimetaphosphate: In situ study. Dent. Mater. 2024, 40, 2077–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Sreedharan, S. Comparative evaluation of the remineralization potential of monofluorophosphate, casein phosphopeptide-amorphous calcium phosphate and calcium sodium phosphosilicate on demineralized enamel lesions: An in vitro study. Cureus 2018, 10, e3059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, D. The development and validation of a new technology, based upon 1.5% arginine, an insoluble calcium compound and fluoride, for everyday use in the prevention and treatment of dental caries. J. Dent. 2013, 41, S1–S11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, S.M.; Alsafadi, M.; Vasconez, C.; Fares, C.; Craciun, V.; O’Neill, E.; Ren, F.; Clark, A.; Esquivel-Upshaw, J. Qualitative analysis of remineralization capabilities of bioactive glass (NovaMin) and fluoride on hydroxyapatite (HA) discs: An in vitro study. Materials 2021, 14, 3813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shihabi, S.; AlNesser, S.; Comisi, J.C. Comparative remineralization efficacy of topical NovaMin and fluoride on incipient enamel lesions in primary teeth: Scanning electron microscope and Vickers microhardness evaluation. Eur. J. Dent. 2021, 15, 420–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbasoglu, Z.; Aksit Bicak, D.; Dergin, D.; Kural, D.; Tanboga, I. Is Novamin toothpaste effective on enamel remineralization? An in-vitro study. Cumhur. Dent. J. 2019, 22, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakry, A.S.; Abbassy, M.A.; Alharkan, H.F.; Basuhail, S.; Al-Ghamdi, K.; Hill, R. A novel fluoride containing bioactive glass paste is capable of re-mineralizing early caries lesions. Materials 2018, 11, 1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldeeb, A.I.; Tamish, N.O.; Madian, A.M. Effect of Biomin F toothpaste and diode laser on remineralization of white spot lesions (in vitro study). BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, K.; Manzoor, S.; Qazi, Z.; Ghaus, S.; Saleem, M.; Kashif, M. Remineralization effect of bioactive glass with and without fluoride and casein phosphopeptide-amorphous calcium phosphate (CPP-ACP) on artificial dentine caries: An in vitro study. Cureus 2024, 16, e70801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobrota, C.T.; Florea, A.D.; Racz, C.P.; Tomoaia, G.; Soritau, O.; Avram, A.; Benea, H.R.C.; Rosoiu, C.L.; Mocanu, A.; Riga, S.; et al. Dynamics of dental enamel surface remineralization under the action of toothpastes with substituted hydroxyapatite and birch extract. Materials 2024, 17, 2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anwar, A.I.; Ruslin, M.; Marlina, E.; Hasanuddin, H. Physicochemical analysis and application of Sardinella fimbriata-derived hydroxyapatite in toothpaste formulations. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reguzzoni, M.; Carganico, A.; Lo Presti, D.; Zecca, P.A.; Scurati, E.I.; Caccia, M.; Levrini, L. Assessment of the effects of enamel remineralization after treatment with hydroxylapatite active substance: SEM study. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebadifar, A.; Nomani, M.; Fatemi, S.A. Effect of nano-hydroxyapatite toothpaste on microhardness of artificial carious lesions created on extracted teeth. J. Dent. Res. Dent. Clin. Dent. Prospect. 2017, 11, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scribante, A.; Cosola, S.; Pascadopoli, M.; Genovesi, A.; Battisti, R.A.; Butera, A. Clinical and technological evaluation of the remineralising effect of biomimetic hydroxyapatite in a population aged 6 to 18 years: A randomized clinical trial. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepla, E.; Besharat, L.K.; Palaia, G.; Tenore, G.; Romeo, U. Nano-hydroxyapatite and its applications in preventive, restorative and regenerative dentistry: A review of literature. Ann. Stomatol. 2014, 5, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, M.M. Potential uses of arginine in dentistry. Adv. Dent. Res. 2018, 29, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandolfi, M.G.; Taddei, P.; Zamparini, F.; Ottolenghi, L.; Polimeni, A.; Prati, C. Dentine surface modification and remineralization induced by bioactive toothpastes. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2024, 22, 554–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsubhi, H.; Gabbani, M.; Alsolami, A.; Alosaimi, M.; Abuljadayel, J.; Taju, W.; Bukhari, O. A comparison between two different remineralizing agents against white spot lesions: An in vitro study. Int. J. Dent. 2021, 2021, 6644069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, A.; Khar, M.; Shahid, N.; Aman, W.; Javed, J.; Rubab, A.; Nayab, M.; Arshad, R.; Rahdar, A.; Fathi-karkan, S.; et al. Progression in nano-botanical oral hygiene solutions: The dawn of biomimetic nanomaterials. Eur. J. Med. Chem. Rep. 2024, 12, 100219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumus, S.; Bakir, E.P.; Bakir, S. Evaluation of the effect of current remineralization agents on enamel by different methods. Cumh. Dent. J. 2024, 27, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shayegan, A.; Arab, S.; Makanz, V.M.; Safavi, N. Comparative evaluation of remineralizing efficacy of calcium sodium phosphosilicate, ginger, turmeric, and fluoride. Dent. Res. J. 2024, 21, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-El-Aziz, A.B.E.; Sallam, R.A. Antibacterial effect of green tea and pomegranate peel extracts on Streptococcus mutans of orthodontic treated patients. J. Rad. Res. App. Sci. 2020, 13, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kote, S.; Nagesh, L. Effect of pomegranate juice on dental plaque microorganisms: A clinical and microbiological study. J. Indian Soc. Perio. 2011, 15, 219–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silaghi-Dumitrescu, L.; Silaghi-Dumitrescu, R.; Pârvu, A.E.; Chicinaş, R.; Pârvu, M.; Pica, E.M. Preventive effects of some remineralizing gels and toothpastes on dental enamel. Stud. Univ. Babeș-Bolyai Chem. 2019, 64, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, C.; Gohil, U.; Parekh, V.; Joshi, S. Comparative evaluation of the remineralizing potential of commercially available agents on artificially demineralized human enamel: An in vitro study. Contemp. Clin. Dent. 2019, 10, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, D.V.; Awchat, K.L.; Singh, P.; Jha, M.; Arora, K.; Mitra, M. Evaluation of remineralizing potential of CPP-ACP, CPP-ACP + F and βTCP + F and their effect on microhardness of enamel using Vickers microhardness test: An in vitro study. Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2022, 15, 221–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinovic, I.; Schauperl, Z.; Marcius, M.; Miletic, I. The effects of three remineralizing agents on the microhardness and chemical composition of demineralized enamel. Materials 2021, 14, 6051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjorgievska, E.S.; Nicholson, J.W. A preliminary study of enamel remineralization by dentifrices based on Recaldent™ (CPP-ACP) and NOVAMIN® (calcium-sodium-phosphosilicate). Acta Odontol. Latinoam. 2010, 23, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.