Featured Application

This review guides the design of wearable EEG devices for monitoring student mental fatigue by identifying optimal hardware configurations, signal processing requirements, and standardisation needs for practical classroom implementation.

Abstract

Mental fatigue significantly impairs student performance and learning outcomes, yet reliable neurophysiological assessment methods remain elusive in educational research. This systematic review examines electroencephalography (EEG) as an objective monitoring tool for mental fatigue in student populations, with particular focus on portable and wearable device applications. Following PRISMA guidelines, we systematically analysed 18 empirical studies (2012–2024, N = 595 participants, ages 10–32) employing continuous EEG during educational tasks. We evaluated frequency band definitions, EEG hardware configurations (from 4-channel portable devices to 64-channel research systems), electrode placements, preprocessing pipelines, and analytical approaches, including machine learning methods. Most studies identified increased frontal theta (4–8 Hz) and decreased beta (13–30 Hz) power as primary fatigue markers across diverse EEG systems. However, substantial methodological heterogeneity emerged: frequency band definitions varied considerably, preprocessing techniques differed, and small sample sizes (median N = 20) limited statistical power. While portable EEG systems demonstrate promise for objective, non-invasive cognitive state monitoring in naturalistic educational settings, current methodological inconsistencies constrain reliability and validity. This review identifies critical standardisation gaps and provides evidence-based recommendations for wearable EEG device development and implementation, including standardised protocols, automated artifact removal strategies, and validation linking EEG measures to educational outcomes.

1. Introduction

Electroencephalography (EEG) is a non-invasive neurophysiological technique that measures brain activity by detecting electrical signals from cortical activity [1,2,3]. Due to its high temporal resolution, EEG is particularly useful for studying neural dynamics during cognitive tasks, including those related to mental fatigue [4,5,6,7]. Unlike functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) or positron emission tomography (PET), EEG offers a cost-effective and accessible alternative, which is ideal for real-world educational settings and fatigue monitoring [8,9]. The increasing availability of portable EEG devices has made continuous cognitive state monitoring more feasible, minimising interference with natural classroom activities.

The advent of portable, wearable EEG systems has further expanded the potential for real-world monitoring of mental fatigue in educational settings. Modern wearable EEG devices, characterised by wireless connectivity, miniaturised sensors, and improved signal quality, enable continuous neurophysiological monitoring during naturalistic learning activities without disrupting classroom dynamics [8]. These technological advances align with growing interest in developing practical brain–computer interfaces (BCIs) and real-time cognitive state assessment tools for educational applications.

The use of EEG in educational research has given rise to the field of neuroeducation, an interdisciplinary area that combines neuroscience, cognitive psychology, and educational science to explore the relationship between brain processes and learning [10,11,12]. Recently, this field has emphasised the study of key executive functions critical for learning, such as attention, working memory, inhibitory control, and cognitive load regulation during educational tasks [5]. Furthermore, EEG-based investigations have examined how environmental variables—such as room size, window placement, and lighting conditions—affect cognitive performance and, consequently, learning efficiency [13,14]. In addition to environmental conditions, other contextual and individual variables—such as emotional state, motivation, task complexity, or auditory distractions—have also been shown to influence cognitive performance and neural activity patterns during learning, as measured by EEG [15,16]. In this sense, EEG allows the detection of brain activity patterns related to these processes, providing valuable information to improve pedagogical strategies [17].

Beyond its role in studying cognitive processes during learning, EEG has also gained prominence as a key tool for investigating mental fatigue, an increasingly relevant construct in educational contexts. Mental fatigue is a multifaceted psychobiological state that arises from prolonged exposure to cognitively demanding tasks [15,18,19,20], encompassing several interrelated dimensions: decreased sustained attention and vigilance capacity, reduced motivation and task engagement, impaired executive functions including working memory and cognitive flexibility, subjective feelings of exhaustion and depletion of mental resources, and objective declines in task performance [7,21]. These dimensions can be assessed through diverse measures, including neurophysiological markers (EEG oscillatory patterns), behavioural performance metrics, and subjective self-report scales. Collectively, these provide a comprehensive characterisation of mental fatigue states.

Mental fatigue manifests through specific alterations in brain oscillatory patterns during cognitive tasks [22]. Research has consistently documented increased theta (θ) power in frontal and central regions, associated with reduced vigilance and compensatory cognitive effort [23,24,25,26,27]. Alpha (α) oscillations show region-dependent changes, with decreased power in occipital areas during task difficulty and increased frontal activity as fatigue progresses, reflecting reduced cortical activation and compensatory mechanisms state [22,28,29,30,31,32]. Conversely, beta (β) power, typically linked to active focus and sustained attention, demonstrates consistent reductions in posterior and central areas during mentally fatiguing tasks, indicating declined cortical excitability and processing efficiency [23,24,27,30,33].

Several studies have validated these changes by analysing parameters such as power spectral density and the absolute or relative magnitudes of frequency bands [2,32,34,35,36,37]. These findings demonstrate EEG’s potential for objectively identifying mental fatigue by quantifying shifts in neural oscillatory dynamics during cognitive task engagement. However, notable inconsistencies persist regarding which frequency bands serve as reliable fatigue markers and optimal methodological approaches, limiting the comparability of results across studies. Although a study systematically reviewed validated instruments for measuring mental load and fatigue, no previous work has examined continuous EEG protocols during educational tasks [38].

EEG’s ability to capture neural activity has made it an essential tool in mental fatigue research among students. However, the field faces significant methodological challenges, notably the lack of standardisation in hardware configurations, frequency band definitions, data acquisition protocols, and preprocessing and analysis methods [8,39]. This methodological heterogeneity has been systematically documented across the broader mental fatigue research field, where substantial variability in experimental protocols and neurophysiological indices has been identified through meta-analytical evidence [40]. While studies have identified similar neurophysiological patterns (increased frontal theta), methodological inconsistencies have prevented precise effect size quantification, hindered the development of standardised detection thresholds, and constrained replication across different systems. This has limited translation into validated practical applications. For example, studies employ varying frequency intervals to define theta or alpha bands, which compromises the comparability of results [31,41]. Moreover, data preprocessing is essential for removing artefacts from eye and muscle movements. However, there is no clear consensus on the optimal filters and techniques to ensure data quality [42].

Another critical aspect in EEG data processing lies in the diversity of analytical approaches, ranging from time- and frequency-domain techniques to more advanced methods such as functional coherence analysis and deep learning for studying brain connectivity [11,12]. However, the absence of standardised guidelines regarding software selection and analytical methodologies in neuroeducation research remains a significant barrier [16]. This methodological heterogeneity hampers the replicability of results and the generalisability of conclusions, highlighting the need for systematic reviews to critically assess these differences.

In this context, this paper aims to conduct a systematic review of EEG-based research on mental fatigue in student populations. The review will critically analyse how technological configurations, data processing protocols, and analytical approaches influence the validity and comparability of findings. This review systematically examines methodological heterogeneity across frequency band definitions, hardware configurations, preprocessing pipelines, analytical approaches, and statistical power. In addition to identifying inconsistencies, it provides a critical evaluation of methodological alternatives and evidence-based recommendations for standardised frequency bands, minimum hardware requirements, optimal preprocessing algorithms, appropriate analytical techniques, and adequate sample sizes. By providing concrete, justified guidelines, this review establishes a framework to enhance standardisation and reproducibility in EEG-based educational research.

Furthermore, it considers the challenges of conducting EEG studies in real-world educational settings, where environmental noise and uncontrolled conditions may affect data reliability. Finally, this work explores emerging technologies such as machine learning and advanced signal processing techniques, assessing their potential to enhance EEG-based mental fatigue detection and optimise its application in educational contexts [12,43]. Given the growing emphasis on methodological rigour, developing standardised protocols is crucial to ensuring the robustness, comparability, and applicability of EEG research in diverse educational settings. This will not only drive advancements in theory but also in the practical implementation of tools to improve academic performance [17,31].

2. Materials and Methods

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines [44] to ensure methodological rigour, transparency, and reproducibility. The review protocol was pre-registered on the PROSPERO platform (registration number: CRD42024583941) on 27 August 2024, prior to initiating data extraction.

For this systematic review, a comprehensive search was performed across five major online databases: Web of Science, Scopus, PubMed, PsycINFO, and ERIC. The search strategy was designed to capture all pertinent studies on the topic using the following search terms: [(“mental fatigue” OR “cognitive fatigue” OR “mental exhaustion” OR “mental exertion” OR “cognitive exertion” OR “cognitive exhaustion” OR “emotional exhaustion” OR “emotional exertion” OR “central fatigue” OR “ego depletion”) AND (“university” OR “high school” OR “secondary school” OR “primary school” OR “elementary school” OR “education”) AND (“children” OR “students” OR “pupils”) AND (“EEG” OR “Electroencephalography” OR “neuro*” OR “neural”)]. This search was conducted by a single author (RAM), with results organised in an Excel spreadsheet to facilitate the removal of duplicate records.

Subsequently, four authors independently screened the titles and abstracts of the 317 records retrieved after duplicate removal. RAM and ARM reviewed the first 160 records, while IGP and ADR assessed the remaining 157. During this initial screening phase, 18 discrepancies regarding inclusion or exclusion were identified. These were resolved through discussion, and when necessary, adjudicated by an additional author (TGC). To assess inter-rater reliability during the title and abstract screening phase, Cohen’s kappa (κ) was calculated, yielding a value of κ = 0.89, which indicates substantial to almost perfect agreement [45].

Articles meeting the eligibility criteria at this stage advanced to full-text review. Each full-text article (n = 38) was examined in detail to confirm compliance with all inclusion criteria. The search was completed on 11 October 2024.

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

The inclusion criteria for this review were defined using the PICOS framework (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, and Study Design) to ensure a systematic and structured approach [46]. Studies were considered eligible if they met the following conditions: (1) Population: participants were students from primary, secondary, university or higher educational levels; (2) Intervention: studies included measures related to mental fatigue, such as mental exertion, cognitive fatigue, emotional exhaustion, or ego depletion; (3) Comparison: not applicable; (4) Outcome: studies assessed mental fatigue levels within educational contexts (operationally defined as primary, secondary, or tertiary education settings involving classroom activities, academic assignments, or educationally relevant cognitive tasks) using continuous EEG measurements (defined as sustained EEG recordings during task performance, as opposed to event-related potentials derived exclusively from discrete, time-locked stimuli), and specifically addressed mental fatigue as a primary or secondary research objective; and (5) Study Design: the review included qualitative, descriptive, correlational, longitudinal, experimental, and cross-sectional studies. To be included in the review, studies had to be published between 2000 and August 2024.

Exclusion criteria included: (1) studies classified as grey literature (e.g., theses, books, dissertations…); (2) articles not available in full text or in English or Spanish (in cases where full text was not available, authors were contacted, and studies were excluded if no response was received); (3) studies that relied exclusively on event-related potentials (ERPs), defined as time-locked voltage deflections in the time domain (e.g., N2, P3 components); however, studies were included if they reported continuous EEG spectral measures (e.g., power, coherence) alongside ERP component analyses; and (4) studies that relied exclusively on instruments other than EEG (e.g., MEG, transcranial stimulation, MRI, etc.).

2.2. Study Selection and Data Extraction

The data extracted from each eligible study included the following key components: (a) study design; (b) the country in which the study was conducted; (c) sample characteristics, such as age, sex, and sample size; (d) measures of mental fatigue, specifications of the EEG system or headset used, the number and configuration of electrodes, and the software applied for data processing (e.g., EEGLAB, Python); (e) details on preprocessing methods, including filters and noise reduction techniques, as well as processing methods and EEG frequency bands analysed, with specific information for each frequency band; and (f) data on the type of intervention, measures of executive functions, and statistical approaches employed to ensure comprehensive and consistent analysis across studies.

Data extraction was performed independently by one author (RAM) and subsequently reviewed for accuracy by three additional authors (ARM, IGP, and ADR).

2.3. Methodological Quality Assessment and Risk of Bias

The risk of bias was independently assessed by four authors (RAM, ARM, IGP, and ADR), with any disagreements re-evaluated collaboratively. In cases where consensus could not be achieved, a final decision was made by an additional author (TGC).

Methodological quality was rated independently by two reviewers (RAM and ARM) using an adapted Downs and Black checklist [47]. Following established systematic review practices for heterogeneous study designs [48], only items applicable to each study’s design were scored. For example, randomization items (14, 15, 23, 24) were excluded for non-randomised designs, and sample size calculation items (27) were omitted when not applicable. Each study received a score based on applicable items from the 28-item checklist. Scores were classified as: excellent (26–28), good (20–25), fair (15–19), or poor (≤14) [48]. Inter-rater reliability was κ = 0.87 (substantial agreement; [45]). Detailed scoring is provided in Appendix A, Table A1. Sample size adequacy was evaluated based on established power analysis guidelines [49,50] to determine whether studies achieved sufficient power (≥0.80) for detecting medium effect sizes (Cohen’s d = 0.5; ηp2 = 0.06 for ANOVA designs) at α = 0.05.

2.4. Statistical Power Analysis

Post hoc statistical power was calculated using G*Power 3.1.9.7 [45] to evaluate study reliability. For each study, we calculated achieved power for detecting medium effect sizes (Cohen’s d = 0.5; ηp2 = 0.06) at α = 0.05. Studies were categorised as adequate (≥0.80), moderate (0.60–0.79), or insufficient power (<0.60) [49,50].

3. Results

3.1. Search Results

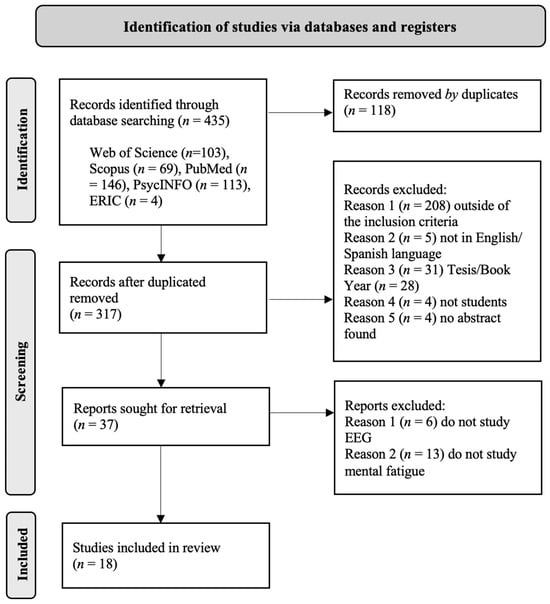

Figure 1 presents the PRISMA flow diagram, detailing each stage of the search and selection process. Initially, 435 studies were retrieved from the databases. After the removal of duplicates, 317 unique articles remained. Screening of titles and abstracts reduced this number to 38, which underwent full-text review. Ultimately, 18 studies met the inclusion criteria for this systematic review. Detailed methodological specifications are provided in Table 1, and study characteristics are summarised in Table 2.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

This systematic review encompassed a total of 18 studies published between 2012 and 2024, with a significant concentration of studies in recent years: 66.7% were published between 2020 and 2024, reflecting the increasing research interest in mental fatigue within educational contexts.

3.2. Geographical Distribution and Participants

Geographically, 44.4% of the studies were conducted in Asia, 22.2% in North America, 16.7% in Europe, and 16.7% in other regions. The studies collectively included 595 participants, with sample sizes ranging from 13 to 48 individuals. The participants’ ages spanned from 10 to 32 years, with mean ages varying across the studies. The studies encompassed various educational levels, with a predominant focus on higher education. University-level students (including undergraduate, graduate, and postgraduate students) comprised the majority of participants (77.8%, n = 14), while primary and secondary education students represented 16.7% (n = 3) and 5.6% (n = 1), respectively.

3.3. Study Design

The majority of studies (61.1%) employed experimental designs, with the remainder comprising quasi-experimental studies (16.7%), randomised controlled trials (11.1%), and observational and cross-sectional designs (11.1%).

3.4. EEG Systems and Hardware

The most frequently used EEG systems were Quick-Cap (16.7%), Ultracortex Mark IV (11.1%), BrainAmp MR Plus (11.1%), Emotiv Epoc X (11.1%), Starstim tES Cap (5.6%), and BioSemi (5.6%). With regard to electrode configurations, 38.9% of the studies utilised systems comprising more than 32 electrodes, while 27.8% employed systems with between 8 and 16 electrodes. The most prevalent electrode placement system was the 10–20 International System, which was adopted by 83.3% of the studies.

3.5. EEG Frequency Bands

The studies analysed several EEG frequency bands, including delta (Δ), theta (θ), alpha (α), beta (β), and gamma (γ). The theta band was examined in 100% of studies (n = 18), the alpha band in 94.4% (n = 17), and the beta band in 88.9% (n = 16). The delta band was considered in 33.3% of the studies, and 16.7% incorporated the gamma band.

Table 1.

EEG System Specifications, Frequency Band Definitions, and Data Processing Methodologies Across Included Studies.

Table 1.

EEG System Specifications, Frequency Band Definitions, and Data Processing Methodologies Across Included Studies.

| Author | EEG System/ Headset | SR | Electrodes | Impedance | Placement System | EEG Frequency Bands | Band Information Provided | Software | Preprocessing (Filters/Noise) | Processing Technique |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [51] | Enophones | - | Four-channel gold-plated dry electrodes Elec. Placement: A1, A2, C3, C4 | - | IS 10–20 | Δ (1–4 Hz), Θ (4–7 Hz), α (8–12 Hz), β (13–29 Hz), γ (30–50 Hz) | - | Brainflow’s Python library (version NM) | Min-max scaling, outlier removal (IQR), quantile methods, and filtering atypical signals | Feature extraction using PSD for EEG bands |

| [52] | Emotiv | - | 14 electrodes | - | - | Δ, Θ, α, β (Bands mentioned without Hz values) | - | Brain Mapping software (EEGLAB toolbox) (version NM) | - | EEG PSA bands (low and high frequency changes) |

| [53] | Emotiv Insight | - | 5 semi-dry polymer sensors (af3, af4, t7, t8, pz) | - | - | θ (0.5–8 Hz), α (9–14 Hz), β (15–30 Hz) | θ: Inward attention, α: Relaxation, β: Focus and concentration | Emotiv software, Python processing (version NM) | Proprietary filtering, FFT, noise removal (<5% discarded) | EEG PSA, β/α ratio for focus, θ/α for inward attention, α asymmetry for motivation, global α for relaxation |

| [23] | Quik-Cap | 250 Hz | 62 Ag–AgCL channels Ref: Earlobes. Gnd: 10/ant. to FZ | 5 kΩ | 10% system | Δ (0–4 Hz), Θ (4–8 Hz), α (8–12 Hz), β (12–20 Hz) | - | MATLAB (EEGLAB 5.03 toolbox) | Baseline normalisation, artifact removal (eye blinks, movements, heartbeats, muscle activity); epochs segmented (500 ms); filtered for bands | PSD using FFT; regional analysis (frontal, central, parietal, occipital); relative power normalised across time points |

| [54] | Quik-Cap SynAmps2 amplifier | 1000 Hz | 9 Ag-AgCl electrodes Pz, P3, P4, Cz, C3, C4, Fz, F3, and F4 | 5 kΩ | IS 10–20 | δ (0.5–3.9 Hz), θ (4–7.8 Hz), α (7.9–12.6 Hz), β (12.7–30 Hz) | - | SynAmps2 and a SCAN™ 4.3 EEG system | 0.15–100 Hz filters; ocular artifact reduction; automatic rejection of epochs exceeding ±100 μV | ERPs; FFT |

| [55] | Starstim tES Cap | 250 Hz | Single-channel dry electrode Electrode positions (F3-F8) | - | IS 10–20 | α (8–13 Hz), β (14–30 Hz) | α-EEG: Relaxation; β-EEG: Effortful thinking | NeuroSky’s proprietary software (version NM) | Artifact correction, spectral transformation using the autoregressive method | Analysis of α and β EEG waves |

| [56] | BrainCap MR | 1000 Hz | 64 electrodes | 5 kΩ | - | N/A (focused on ERP components) N2 (200–350 ms), P3 (350–600 ms) | ERP components: NoGo-N2 (conflict monitoring), NoGo-P3 (response inhibition), Go-P3 (attentional resource allocation) | E-prime (Psychology). Software Tools, (Pittsburgh, PA, USA) (version NM) | Bandpass filter (1–30 Hz), epoching (−200 to +800 ms), artifact rejection (±120 μV), manual ICA for artifact removal | ERP analysis focused on N2 (200–350 ms) and P3 (350–600 ms) at Fz, Cz, and Pz sites for Go/NoGo tasks; ANOVA and post hoc contrasts |

| [57] | Emotiv Epoc X 14 channels | - | 14 channels AF3, AF4, F3, F4, F7, F8, FC5, FC6; T7, T8; O1, O2; P7, P8 | - | IS 10–20 | Δ (0.5–4 Hz), Θ (4–8 Hz), α (8–13 Hz), SMR (13–15 Hz), βMid (15–20 Hz), β (13–30 Hz) | - | MATLAB (EEGLAB v14.1.2. toolbox) | FIR filter (2–39 Hz), ICA for artifact removal | PSD for δ, θ, α, SMR, mid-β, β; relative band power calculation |

| [29] | Quick-Cap | 1000 Hz | 32 channels NaCl-based conductive gel | 5 kΩ | IS 10–20 | Δ (1–3 Hz), Θ (4–7 Hz), α (8–14 Hz), β (15–30 Hz) | Δ, Θ (occipital) ↑; β ↓ (occipital, temporal) with longer response times, indicating MF ↑ | MATLAB (EEGLAB toolbox) (version NM) | 1 Hz high-pass, 50 Hz low-pass FIR filter, manual artifact rejection | FFT for spectral analysis, power spectral changes calculation |

| [58] | Quick-Cap | 1000 Hz | 32 channels using NaCl-based conductive gel | 5 kΩ | IS 10–20 | Θ (4–8 Hz), αlow (8–10 Hz), α (8–13 Hz), Δ (1–4 Hz) | - | MATLAB 2018-based open software EEGLAB v15.0B | 1–50 Hz bandpass filter, ICA for artifact removal, FFT for spectral analysis | PSA: focus on theta, low-alpha, and high-frequency power changes related to depression and anxiety |

| [59] | BIOPAC System EEG100C | 500 Hz | Gold-plated electrodes F3, F4, C3, C4, P3, P4, O1, and O2. Ref: Cz, Gnd: Faz. | 5 kΩ | IS 10–20 | Δ (1–4 Hz), Θ (4–7 Hz), α (8–12 Hz), β (13–29 Hz) | α power during HEP components (F3, F4); ERP latency at P4, O1, O2 | LabVIEW 2010, AcqKnowledge v4.1 | Blink artifact removal (EOG), FFT alpha for power extraction, signal normalisation | Feature extraction: HEP first and second components; ERP latency; FFT-based alpha synchronisation |

| [60] | Ultracortex Mark IV EEG headset | 250 Hz | 8 dry electrodes FP2, FP1, C4, C3, P8, P7, O1, and O2, and REF: one placed in each earlobe | - | IS 10–20 | Δ (1–4 Hz), Θ (4–7 Hz), α (8–12 Hz), β (13–29 Hz), γ (30–50 Hz) | MF linked to Θ ↑, β ↓ power, showing reduced cognitive processing. P300 latency correlated with fatigue. | MATLAB (EEGLAB toolbox) OpenVIBE (version NM) | 60 Hz Notch filter, 0.1–100 Hz bandpass filter, artifact subspace reconstruction (ASR) | Multiple linear regression (MLR), PSD, P300 amplitude/latency analysis |

| [61] | Ultracortex Mark IV EEG headset | 256 Hz | 8 dry electrodes FP2, FP1, C4, C3, P8, P7, O1, and O2 | - | IS 10–20 | Δ (1–4 Hz), Θ (4–7 Hz), α (8–12 Hz), β (13–29 Hz), γ (30–50 Hz) | Θ: Indicative of mental fatigue (θ/α relevant) | OpenBCI (OpenVibe) Matlab (version NM) | Bandpass filter (0.1–100 Hz, 4th-order Butterworth); artifact removal with ASR (k = 15); normalisation to eyes-open baseline | PSA (FFT for bands); feature extraction with normalised power and power ratios |

| [62] | BioSemi head-cap (suitable size) | 1024 Hz | 64 Ag-AgCl active electrodes | - | IS 10–20 | N/A (focused on ERP components) P3 (250–400 ms) | P3: attention, reduced in ADHD; N2: inhibitory control; LC: memory updating and task prep. | MATLAB (EEGLAB toolbox) (version NM) | Bandpass filter (1–80 Hz), notch filter (50 Hz), ICA for artifact removal, referencing to average electrodes | ERP analysis of early and late components (P3, LC) using ANOVA, post hoc tests, and correlations between behavioural indices and ERP amplitudes |

| [63] | Brain Products MR Plus | 2000 Hz | 64 Ag/AgCl scalp electrodes | 5 kΩ | IS 10–20 | Δ (1–4 Hz), Θ (4–7 Hz) | Θ: cognitive control; Δ: inhibition and fatigue | MATLAB 2020B (EEGLAB toolbox) | Bandpass 1–40 Hz, notch filter at 50 Hz, ICA for artifact removal | PSA using Welch’s method |

| [64] | EasyCap Brain | 1000 Hz | 63 sintered Ag-AgCl electrodes Ref: FCz. Gnd: AFz | 5 kΩ | - | N/A (focused on ERP components) N2(290 ms); P2(213–227 ms); P3(290 ms) | P2, P3: cognitive control and working memory; N2: cognitive control and conflict detection | Brain Vision Analyzer 2.0. Software | Bandpass filter (recording): 0.01–250 Hz Bandpass filter (offline): 0.1–35 Hz (Butterworth, 2nd order, 0-phase shift 48 dB) Notch filter: 50 Hz | ERP analysis of N1, P2, N2, P3 components Feature extraction for latency and amplitude differences |

| [65] | CAP100C | 1000 Hz | AgCl electrodes: F3, F4, Fz, Fp, O1 and O2. Ref: earlobe | 5 kΩ | IS 10–20 | α (8–13 Hz) | O1-O2 channels linked to visual fatigue, NM for others | BIOPAC MP150 system with AcqKnowledge 4.0 | EEG: Bandpass filter (1–100 Hz), EOG-based blink removal | FFT for EEG α power (8–13 Hz); RMS for |

| [66] | NSW316Neuracle | 1000 Hz | 16-scalp electrodes Electronic earlobe reference | 5 kΩ | IS 10–20 | α (without Hz values) | decreased complexity in a rhythm (8–13 Hz) with MF, as shown by MSE analysis | NM | Bandpass filter (0.01–100 Hz), Butterworth bandpass (8–13 Hz) for α extraction | MSE analysis on α rhythm and its instantaneous frequency variation (IFV) |

SR: Sampling Rate; NM: not-mentioned; MLR: Multivariate Linear Regression; IS: International System; Δ: Delta; Θ: Theta; α: Alpha (8–12 Hz); β: Beta; Ref: Reference electrode; Gnd: Ground electrode; EEG: electroencephalography; ERP: event-related potential; ICA: independent component analysis; FFT: fast Fourier transform; Hz: hertz; ms: milliseconds; HEP: Heartbeat Evoked Potential; ERP: Event-Related Potential; MSE: Multiscale Entropy; ↓: decrease, ↑: increase.

3.6. Software and Preprocessing Techniques

The most frequently employed software included MATLAB (with the EEGLAB toolbox, 38.9%), OpenVIBE (11.1%), Brainflow (11.1%), and NeuroSky (5.6%); specific versions are detailed in Table 1. Regarding preprocessing, 66.7% of the studies applied high-pass and low-pass filters, typically ranging between 0.1 Hz and 100 Hz. Furthermore, 50% of the studies employed Independent Component Analysis (ICA) to eliminate artifacts such as eye blinks and muscle movements.

3.7. EEG Data Processing Techniques

Power spectral analysis (PSA) was utilised in 44.4% of the studies, typically focusing on key frequency bands such as theta (θ), alpha (α), and beta (β) to assess mental fatigue. Within PSA, various sub-analyses were employed, including total power, individual peak alpha frequency (IPAF), and energy within frequency bands. Some studies examined relative power in specific bands, while others focused only on frequency shifts to investigate fatigue-related changes.

The Fast Fourier Transform (FFT), used in 33.3% of the studies, calculated power spectral density (PSD) and helped identify peak frequencies and energy distribution across the frequency spectrum. In 22.2% of the studies, Event-Related Potential (ERP) analyses focused on components like N2 and P3, which are linked to cognitive functions such as attention and inhibition during mental fatigue.

A further 27.8% of studies utilised power ratios, such as θ/α and β/θ, as indicators of cognitive state and fatigue.

It is important to specify that the final variables analysed in these studies were reported in different units. For example, μV2/Hz was commonly used for power calculations, while Hz was used to describe frequency. Additionally, studies varied in their approach to normalisation. Some applied baseline corrections or z-scores to the data, while others worked with raw, untransformed data. These differences in data processing and normalisation methods can influence the results and their comparability across studies.

3.8. Statistical Approaches

The primary statistical methods that were employed included repeated-measures ANOVA (38.9%), paired t-tests (27.8%), MANOVA (11.1%), and multiple linear regression models (16.7%). Predictive models using machine learning were applied in 16.7% of the studies.

This comprehensive description highlights the diversity of devices, frequency band configurations, and analytical approaches employed to assess mental fatigue through EEG across different studies. The present review aims to provide clarity regarding the methodologies used, emphasising the need for consistency and standardisation to enhance future research efforts.

3.9. Quantitative Analysis of Methodological Heterogeneity

To address reviewer concerns about whether methodological variability affected outcomes, we conducted quantitative analyses examining relationships between methodological parameters and reported fatigue markers.

Frequency band definitions: Theta definitions ranged from 4–7 Hz (n = 5) to 4–8 Hz (n = 11), yet all studies reported increased frontal theta during fatigue. Similarly, alpha (8–12 Hz vs. 8–13 Hz) and beta (13–29 Hz vs. 13–30 Hz) demonstrated consistent directional shifts across definitions. While qualitative convergence demonstrates robust patterns, varying definitions prevent precise effect size comparison and meta-analytical integration.

Hardware configurations: Low-density systems (4–8 electrodes; n = 5) and high-density systems (≥32 electrodes; n = 7) both detected core biomarkers (frontal theta increase, posterior beta decrease). High-density systems provided superior spatial localization [23,54,59], while low-density systems successfully identified global patterns but with reduced regional specificity [51,61,62]. No systematic relationship was identified between electrode density and biomarker detection failure.

Preprocessing approaches: Studies using ICA (50%; n = 9) reported cleaner spectral patterns and higher classification accuracies (85–88%) [51,61] compared to basic filtering. This suggests that preprocessing quality affects detection precision, although direct comparison was limited by design heterogeneity.

Statistical power: Sample size analysis revealed that 61.1% of studies (n = 11) employed samples below n = 25. Based on established power analysis guidelines [49,50], studies with n < 20 (n = 6: [51,59,60,61,65,66]) would have insufficient statistical power (<0.60) to reliably detect medium effect sizes (Cohen’s d = 0.5), indicating high Type II error risk and potential effect size inflation.

Studies with n = 20–30 (n = 8: [23,29,53,54,55,56,57,58]) would achieve moderate power (0.60–0.78), providing adequate but not optimal detection capability. Only 22.2% of studies (n = 4: [52,62,63,64]) used sample sizes (n > 30) providing adequate power (≥0.80) for reliable effect detection. These power limitations have critical implications for research: reported effect sizes from underpowered studies may be inflated due to statistical selection bias, non-significant findings cannot be interpreted as evidence of absence, confidence intervals are excessively wide, and small samples inadequately represent population diversity [49,50].

Core biomarkers demonstrate robust detection across methodologies, indicating genuine neurophysiological phenomena. However, heterogeneity prevents quantitative integration, precise effect estimation, and the development of standardised thresholds necessary for validated practical applications.

Table 2.

Study characteristics, participant demographics, and key findings of included studies.

Table 2.

Study characteristics, participant demographics, and key findings of included studies.

| Study | Count. | S.D. | Sample | Age | Intervention | Study Objective | Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [51] | Mexico | Exp., cross-sectional | N = 22 10 females 14 males | MAge = 19.8 SD = 2 | IoT-based biofeedback to monitor and improve learning | Enhance learning via real-time biometric feedback on cognitive performance | Θ ↑ and β ↓ power correlated with MF in the auditory-oddball task. The EEG model classified fatigue with 85% accuracy |

| [52] | Iran | Exp. cross-sectional | N = 32 males | MAge = 20 | FIFA 2015 video game (single-elimination tournament). Pre-post assessment with PASAT and EEG | Assess the impact of video games on brain activity, attention, and physiological stress response | During video games, increased low-frequency (≈3 Hz) power, decreased power in 6–10 Hz (occipital), and 15–18 Hz (frontal). PASAT showed no significant MF changes |

| [53] | USA | Quasi-Exp. | N = 46 26 females 19 males N1 = 24 N2 = 21 | MAge 1 = 14 MAge 2 = 11 | 15-min biking session (outdoor track), followed by Stroop before and after biking, EEG monitored throughout | Investigate the cognitive and neurological effects of biking on adolescent students’ MF and cognitive performance | β ↑ during activity, α rose post-activity, θ ↓; working memory and psychomotor speed improved (d = 0.45) |

| [23] | USA | Exp. | N = 14 30% females 70% males | MAge = 21.4 SD = 1.3 | Stroop (Word and Interference) | Examine multimodal fatigue (subjective, cognitive, physiological) during sports concussion assessments to provide a baseline for understanding fatigue effects in clinical populations | Θ ↑ (frontal-parietal) and migration of α (occipital to anterior) in the final Stroop task. Subjective fatigue is linked to more errors |

| [54] | Canada | Exp. | N = 24 females | Arange = 16–18 MAge = 16.9 SD = 0.4 | Stroop colour-word matching task (morning vs. afternoon; Monday vs. Wednesday) | To examine how bedtime patterns, social jet lag (SJL), and school start times (SST) affect cognitive performance and EEG patterns | Δ ↑ Wednesday afternoon, indicating accumulated MF and error monitoring. Θ and β ↑ Monday, reflecting cognitive effort and conflict monitoring during Stroop |

| [55] | China | Quasi-exp. | N = 48 27 females 21 males | MAge = 10.42 SD = 1.05 | Various horticultural activities (flower arranging, kokedama crafting, seed sowing, pressed flower card making, decorative bottle painting) | Evaluate the effectiveness of horticultural activities in stress recovery and MF reduction in elementary students | Horticultural activities boosted α-EEG and reduced β-EEG, suggesting lower stress and MF. Flower arrangement and Kokedama activities had the best recovery outcomes |

| [56] | China | Randomised controlled trial | N = 36 18 females 18 males | Arange = 18–22 MAge = 20.3 | Relaxing music vs. no music during task | To investigate the effect of relaxing music on alleviating mental fatigue and maintaining performance during a continuous cognitive task | Music group had less MF, stable reaction times, and higher P3 amplitudes compared to controls. Control group showed impaired inhibitory control (lower NoGo-P3 amplitude) |

| [57] | South Korea | Exp., repeated-measures design | N = 20 4 females 10 males | Arange = 23–32 MAge = 26.65 SD = 2.61 | Thermal conditions tested in a climate chamber; cognitive tests at 5 conditions (PMV −2 to PMV 2) | Analyse the relationship between thermal conditions, psychophysiological responses, and learning performance | MF and reduced executive ability in cold (17 °C) and warm (33 °C) conditions. Optimal performance at 25.7 °C. EEG showed ↑ d MF and workload, without specific spectral power values |

| [29] | Taiwan | Exp., observational | N = 18 7 females 11 males | Arange = 23–27 | Visual attention task during a real university lecture | Investigate EEG spectral changes associated with sustained attention and MF in a real-world classroom setting | Δ, Θ ↑ in occipital (+15–20%) during slow responses, linked to increased visual fatigue. β ↓ by 25% in occipital/temporal regions, indicating reduced visual alertness. α↓ slightly, no significant change |

| [58] | Taiwan | Longitudinal | N = 18 7 females 11 males | MAge = 24.0 SD = 1.2 | Daily Sampling System (DSS) app for self-reports; bi-weekly EEG recordings after DASS-21 completion | Analyse the relationship between emotional states (stress, anxiety, depression), sleep patterns, and fatigue in students | Θ ↑ and low α linked to anxiety and stress. Higher depression correlated with increased high-frequency EEG in temporal regions. No significant prefrontal α asymmetry |

| [59] | Korea | Exp. | N = 30 15 females 15 males | Arange = 20–28 MAge = 24.1 SD = 3.1 | Viewing 2D and 3D videos for 1 h. | To evaluate 3D cognitive fatigue using HEP as an indicator of heart–brain synchronisation | 3D visual fatigue increased α at F3/F4 regions, prolonged ERP latency at P4, O1, and O2, indicating reduced cognitive capacity and attention |

| [60] | Mexico | Exp., cross-sectional | N = 17 9 females 8 males | MAge = 22 SD = 3 | Passive EEG recording during 5-min P300 oddball task | Develop a fast and efficient EEG-based MF assessment tool for workplace and educational environments | Θ ↑ (+20%) and β ↓ (−25%) in C3 and O2 indicate reduced cognition. β/Θ and α/Θ ratios linked to higher fatigue (p < 0.01). P300 latency ↑ (+15%), delaying responses. EEG model predicted MF with 88% accuracy |

| [61] | Mexico | Exp., comparative | N = 20 12 females 8 males | MAgeT = 22.3 SD = 1.63 MAgeV = 22.7 SD = 2.26 | Text vs. Video learning tasks | Evaluate and compare EEG spectral components and cognitive performance in text and video learning, developing predictive models using EEG data | High θ/α at C3 and delta at FP1 are linked to fatigue and lower performance. Video group performed better, had less fatigue, and optimised cognition with reduced high-frequency ratios |

| [62] | Israel | Double-blind placebo-controlled crossover | N = 18 8 females 10 males | Arange = 9–17 MAge = 12.2 SD = 2.8 | Placebo vs. methylphenidate (MPH) | To investigate MPH’s normalising effects on P3 amplitudes in ADHD and its role in mitigating MF effects during cognitive tasks | MPH increased P3 amplitude in frontoparietal regions vs. placebo, indicating improved attention. Placebo showed lower P3 amplitude, suggesting MF. MPH normalised brain activity |

| [63] | China | Exp., within-subject | N = 19 6 females 13 males | MAge = 22.16 SD = 0.65 | 15-min rest break vs. 15-min exercise break | Investigate the effects of rest and exercise on MF recovery using EEG PSA | Θ ↓ post-exercise, correlating with improved vigilance. Δ ↑, indicating inhibition of interference thoughts. Rest-break showed Δ ↓, indicating improved long-term attention |

| [64] | China | Exp. cross-sectional | N = 36 males | MAge = 25 SD = 2.91 | 100-min 2-back working memory task | Investigate neural patterns prior to errors in a long-lasting working memory task under fatigue | Decreased P2 and P3 amplitudes and delayed N2 latency preceded errors during prolonged working memory tasks, indicating reduced cognitive control and attention under mental fatigue. Error-related neural patterns emerged 200–300 ms before behavioural responses |

| [65] | Malaysia | Exp. | N = 14 7 females 7 males | MAge = 23.1 SD = 1.79 | Repetitive precision tasks with two difficulty levels | Develop predictive models for muscle and MF during repetitive precision tasks | Elevated α in O1-O2 linked to visual demand and fatigue in high-precision tasks. Fatigue correlated with muscle fatigue over time |

| [66] | China | Exp., pre-post | N = 13 males | Arange = 20–22 MAge = 21 SD = 1.2 | Simulated flight task + mental arithmetic (60 problems) | Investigate the complexity loss in the EEG due to MF using MSE on the α rhythm | Complexity of α rhythm decreased by up to 30% after MF, especially in parietal/occipital regions. MSE on IFV showed higher sensitivity, confirming cognitive decline |

Exp.: Experimental; SD: Standard Deviation; MAge: Mean Age; Arange: Age Range; Δ: Delta; Θ: Theta; α: Alpha (8–12 Hz); β: Beta; HEP: Heartbeat Evoked Potential; ERP: Event-Related Potential; Multiscale Entropy; ICA: Independent Component Analysis; PSA: Power spectral analysis; PSD: Power spectral density; FFT: Fast Fourier Transform; ↓: decrease, ↑: increase.

4. Discussion

This systematic review examined EEG-based research on mental fatigue in student populations, focusing on methodological approaches, frequency bands, and the impact of different systems and processing techniques. The analysis of 18 studies confirms that theta (θ), alpha (α), and beta (β) frequency bands serve as primary indicators of mental fatigue, aligning with established neurophysiological research [32,35,67]. Our findings demonstrate that increased theta activity, particularly in frontal regions, represents a consistent biomarker of cognitive overload and performance decline during prolonged cognitive tasks [23,37,66,68]. Correspondingly, reduced beta activity in central and posterior cortical regions correlates with decreased alertness, lower cognitive efficiency, and impaired sustained attention [23,37,66,68]. These spectral changes reflect a shift toward lower-frequency oscillations, indicating declined cortical excitability and reduced information processing efficiency during mental fatigue [22,31]. While these convergent findings demonstrate the robustness of theta, alpha, and beta bands as qualitative fatigue biomarkers, the present analysis reveals that methodological heterogeneity introduces quantifiable limitations for translating research into standardised applications. The following sections critically evaluate methodological alternatives across key domains, including frequency band definitions, hardware configurations, preprocessing approaches, and analytical methods. Evidence-based recommendations are provided for each, with explicit justification.

4.1. Critical Evaluation of Methodological Alternatives and Evidence-Based Recommendations

The systematic analysis of 18 studies revealed substantial methodological heterogeneity across four critical domains: frequency band definitions, hardware configurations, preprocessing pipelines, and analytical approaches. This section provides a thorough evaluation of the available options in each domain, offering explicit recommendations supported by empirical evidence and practical considerations for educational implementation.

4.1.1. Frequency Band Definitions: Evaluation and Standardisation Recommendations

Our analysis revealed significant variability in frequency band definitions, particularly in the theta range (4–7 Hz to 4–8 Hz) and the alpha range (8–12 Hz to 8–13 Hz). While all studies indicated directional changes during fatigue (theta increase, beta decrease), the lack of a uniform definition hinders the ability to quantitatively compare effect sizes and limits meta-analytical integration [2,8,31]. Such variability affects result interpretation and constrains translation of findings into practical applications [2].

Based on neurophysiological evidence and analysis of the reviewed studies, we recommend the following standardised definitions for mental fatigue research in educational settings:

Theta band (4–8 Hz): This range aligns with established neurophysiological literature linking frontal midline theta to sustained attention, working memory load, and cognitive control processes [32]. The 4–8 Hz definition was employed by 61% of reviewed studies [23,57,58] and captures the spectrum of slow oscillatory activity associated with effortful cognition. Narrower definitions (4–7 Hz) [60,63] risk excluding relevant high-theta activity, while broader definitions (3–8 Hz) [53] conflate theta with delta activity, reflecting different neural processes [22].

Alpha band (8–13 Hz): The 8–13 Hz range encompasses the full alpha rhythm spectrum, including both low-alpha (8–10 Hz) associated with attentional processes and high-alpha (10–13 Hz) linked to semantic memory and task-related activation [28,30,32]. The broader 8–13 Hz range better captures individual peak alpha frequency variability across diverse student populations [31].

Beta band (13–30 Hz): Beta activity reflects cortical activation, focused attention, and active cognitive processing [23,27,33]. The 13–30 Hz range was consistently employed across 88.9% of reviewed studies and aligns with established definitions distinguishing beta from gamma activity.

Standardising these definitions enables direct comparison of absolute power values across studies, facilitates meta-analytical synthesis, and supports development of validated detection thresholds for practical fatigue monitoring applications.

Quantitative comparison of effect sizes between theta frequency definitions. The reviewer correctly identified that establishing whether different theta frequency definitions (4–7 Hz vs. 4–8 Hz) yield systematically different effect sizes would provide empirical evidence for standardisation recommendations. We attempted to conduct this statistical comparison by extracting effect sizes from all 18 included studies. However, this analysis proved methodologically infeasible for the following reasons: (1) Insufficient effect size reporting: Only 2 of 18 studies (11.1%) reported standardised effect sizes for theta-related measures. Bailey et al. [53] reported ηp2 = 0.011–0.128 and d = 0.211–0.746 for theta-related measures (theta/alpha ratio, not theta absolute power), while Wang et al. [63] reported ηp2 = 0.178–0.245 for theta power. Critically, both studies employed the 4–7 Hz definition; no studies using the 4–8 Hz definition reported comparable effect sizes. (2) Heterogeneous statistical reporting: The remaining 16 studies reported theta changes using incompatible metrics, including F-statistics without effect sizes (n = 6), p-values only (n = 4), correlation coefficients (n = 2), classification accuracy (n = 2), or did not analyse theta spectral power (n = 2). These metrics cannot be converted to standardised effect sizes without access to raw data. (3) Construct heterogeneity: Even the two studies reporting effect sizes analysed different constructs (theta/alpha ratio vs. absolute theta power) under different experimental conditions, precluding direct statistical comparison.

Consequently, the statistical test comparing effect sizes between theta definitions that would ideally support our standardisation recommendation cannot be performed with existing published data. This inability to conduct quantitative synthesis paradoxically strengthens the case for standardisation: the current state of heterogeneous reporting prevents the very meta-analytical evaluations necessary to establish evidence-based protocols. We have therefore revised our manuscript to acknowledge this as a critical limitation of the current literature (rather than a limitation of this review alone) and explicitly recommend that future studies report standardised effect sizes (Cohen’s d, partial eta-squared with confidence intervals) to enable the quantitative comparisons necessary for evidence-based standardisation.

4.1.2. Hardware Configurations: Balancing Spatial Resolution with Practical Feasibility

Hardware configurations showed considerable diversity, ranging from low-density portable systems, such as the Emotiv Epoc X (14 channels) [52,57] to high-density systems such as Quick-Cap with 64 electrodes [23,54]. Our analysis revealed that while all electrode density levels successfully detected core fatigue patterns (frontal theta increase, posterior beta decrease), spatial resolution capabilities differed systematically.

High-density systems (32–64 electrodes) provide superior spatial localization, enabling investigation of regional gradients, hemispheric asymmetries, and network connectivity patterns [11,59]. However, these systems require extensive setup time, technical expertise, and controlled laboratory environments, which limit their feasibility for naturalistic educational implementations [8,29].

Low-density portable systems (4–16 electrodes) offer practical advantages including rapid setup, wireless connectivity, and minimal classroom interference [51,61,62]. However, systems with fewer electrodes inherently limit measurement precision and reduce spatial resolution [11,59]. Furthermore, hardware variability influences noise levels and signal precision. This is particularly problematic in less controlled educational environments where portable systems are often used [8,29,60]. Nevertheless, studies have demonstrated that strategic electrode placement covering frontal, central, and posterior regions can reliably detect established fatigue biomarkers, achieving 85–88% classification accuracy with 8-channel systems [51,61].

For research applications that prioritise mechanistic understanding, high-density systems (≥32 electrodes) following the 10–20 International System remain optimal [23,54,67]. For practical educational monitoring and wearable applications, strategically designed systems with 8–16 electrodes covering frontal, central, and occipital regions provide sufficient sensitivity while maintaining feasibility for extended naturalistic recordings [8,17].

Recommendation: Minimum configuration should include frontal (bilateral and midline), central (bilateral), and posterior (bilateral occipital) coverage (8 electrodes minimum) following 10–20 International System placement conventions to ensure reliable detection of established fatigue biomarkers.

4.1.3. Preprocessing Pipelines: Optimising Artifact Removal for Educational Settings

Data preprocessing approaches revealed substantial methodological inconsistencies. Although 66.7% of studies implemented filtering within 0.1–100 Hz ranges, artifact removal techniques varied considerably. Some studies employed sophisticated Independent Component Analysis (ICA) for eye and muscle artifact elimination [53,64], while others relied on basic notch filters [52]. Studies employing ICA or advanced artifact removal consistently reported cleaner spectral patterns and higher classification accuracies compared to basic filtering approaches [29,54,57].

In the context of educational EEG recordings, artifact sources may include eye blinks, eye movements, muscle activity, and motion artifacts. These artifacts are particularly prevalent in naturalistic classroom settings [8,59,60]. Inadequate artifact removal can significantly distort results and underestimate mental fatigue-related brain activity, particularly when using portable EEG systems where motion artifacts are more prevalent [17,59,60,61]. Evaluation of preprocessing alternatives reveals:

Independent Component Analysis (ICA): ICA decomposes EEG signals into independent components, enabling identification and removal of artifact components while preserving neural signals [60,64]. Studies employing ICA consistently demonstrated superior signal quality and more reliable detection of fatigue-related spectral changes [29,54,57].

Manual artifact rejection: Visual inspection and manual rejection of contaminated epochs provide straightforward artifact removal. However, they are time-consuming, subjective, and may introduce experimenter bias [23,42].

Automated artifact rejection: Artifact Subspace Reconstruction (ASR) offers automated real-time artifact correction suitable for wearable applications [61,62]. Although ICA has received more extensive validation, ASR demonstrates potential for practical applications that require minimal manual intervention.

Filtering is essential for removing electrical line noise (50/60 Hz notch filter) and physiologically irrelevant frequencies. High-pass filtering (≥0.1 Hz or 1 Hz) removes slow drift artifacts, while low-pass filtering (typically 40–100 Hz) removes high-frequency muscle artifacts [29,42,54,64].

Recommendation: Implement bandpass filtering (0.1–100 Hz or 1–50 Hz) combined with a 50/60 Hz notch filter, followed by ICA-based artifact correction for research applications. For wearable real-time applications, implement ASR or similar automated approaches. Standard preprocessing pipelines should be thoroughly documented to ensure replicability. This variability in preprocessing standardisation remains a significant challenge to reliable cross-study comparisons that must be addressed through methodological harmonisation.

4.1.4. Analytical Methods: Selecting Appropriate Techniques for Research Objectives

Analytical approaches have shown promising evolution from traditional power spectral density (PSD) and fast Fourier transform (FFT) methods toward advanced techniques, including functional coherence analysis and machine learning-based predictive models [12]. These sophisticated approaches offer enhanced precision in characterising brain connectivity patterns and developing predictive tools for educational applications [11,54,66,69,70]. Machine learning integration with EEG data particularly enables personalised educational interventions and real-time cognitive state monitoring [16,63].

Critical evaluation reveals that method selection should align with specific research objectives:

Traditional spectral analysis (PSD, FFT) provides interpretable, well-validated quantification of frequency band power. It is appropriate for establishing baseline neurophysiological patterns, comparing fatigue effects across experimental conditions, and investigating relationships between EEG markers and behavioural performance [23,32,54,58]. These methods provide transparent, reproducible results [37].

Machine learning approaches (support vector machines, random forests, deep learning) enable the development of predictive models for real-time fatigue classification and integration of multimodal features [11,12,51,61]. However, these methods require larger sample sizes to prevent overfitting, demand rigorous cross-validation procedures, and may lack interpretability regarding underlying neural mechanisms [43,69]. Studies employing machine learning without adequate sample sizes risk reporting inflated accuracy estimates that fail to generalise [51,61].

Recommendation: Use traditional spectral analysis (PSD/FFT with appropriate statistical tests) for mechanistic research investigating neurophysiological patterns. Reserve machine learning approaches for the development of predictive classification models, ensuring adequate sample sizes (n > 50), rigorous cross-validation (leave-one-subject-out or k-fold), and independent validation datasets. Report both the classification accuracy and the interpretability of features contributing to predictions.

4.1.5. Sample Size Considerations and Statistical Power Requirements

Study design analysis revealed that 61.1% employed experimental designs [51,57,63], with additional quasi-experimental studies [55] and randomised controlled trials [56] demonstrating increased methodological rigour in establishing causal relationships between cognitive tasks and neural activity changes [29,35]. However, the predominance of small sample sizes (mean: 33 participants; range: 13–48 participants, median: 20) limits statistical power and results in generalizability [52,60,61,63]. This represents a significant limitation for robust scientific conclusions and practical implementation in diverse educational contexts.

Small sample sizes substantially reduce statistical power and increase Type II error probability, particularly problematic given the complex analytical approaches employed (mixed-model ANOVA, machine learning). Small samples also generate wide confidence intervals, compromising the effect size precision essential for reliable EEG biomarkers. Furthermore, these samples inadequately capture the diversity necessary for robust external validity in educational settings [49,50], significantly limiting translation into scalable interventions.

Studies with insufficient power can lead to a higher probability of failing to detect true effects. Paradoxically, they may also inflate effect size estimates in significant findings due to statistical selection bias [49]. Additionally, the use of small samples can limit the representation of population diversity across age, educational level, and individual differences, thereby constraining external validity [50].

Recommendation: Future studies should conduct a priori power analyses to determine adequate sample sizes based on expected effect sizes. For between-subjects comparisons detecting medium effects (d = 0.5), a minimum of n = 64 per group achieves 80% power. For repeated-measures designs (common in fatigue research), n = 34 achieves 80% power for detecting medium within-subjects effects. For machine learning classification studies, a minimum of n = 50–100 is recommended, depending on feature dimensionality and model complexity [11,49]. Studies should report achieved power for primary analyses and prioritise adequately powered designs over exploratory underpowered investigations.

4.2. Educational Implications of EEG-Based Mental Fatigue Detection

The educational implications of these findings are significant. EEG-based mental fatigue detection enables real-time monitoring of students’ cognitive states, allowing educators to implement dynamic pedagogical adjustments. Practical applications include implementing strategic breaks based on fatigue indicators, adjusting task durations, and personalising educational content according to detected cognitive load [32,59,61,71]. Such interventions have the potential to enhance learning outcomes by preventing cognitive overload and optimising engagement during extended academic activities [37,66,68]. However, translating these research findings into practical educational implementations requires addressing the methodological standardisation gaps identified in this review. These gaps pertain particularly to frequency band definitions, preprocessing protocols, and validation of detection thresholds across diverse student populations and educational contexts.

4.3. Implications for Wearable EEG Device Development and Implementation

The reviewed studies employed diverse EEG systems ranging from low-density portable devices (4 channels) to high-density research systems (64 channels). It is important to note that fatigue-related patterns in frontal-central theta and beta activity were consistently identified across electrode densities. This suggests that practical wearable devices with strategic placement covering frontal, central, and occipital regions (8–16 channels) may provide sufficient sensitivity while maintaining portability for real-world educational applications.

Several studies have employed modern wireless systems (Emotiv Epoc X, Ultracortex Mark IV, Enophones), demonstrating the feasibility of continuous monitoring during authentic learning activities. However, the methodological heterogeneity identified—particularly in frequency band definitions, preprocessing approaches, and validation methods—must be addressed before wearable EEG transitions from research tools to reliable educational applications.

For wearable device development, this review underscores key priorities: (1) implementing standardised frequency band definitions (theta: 4–8 Hz; alpha: 8–13 Hz; beta: 13–30 Hz) in embedded algorithms; (2) incorporating robust automated artifact removal for naturalistic settings; (3) designing user-friendly configurations balancing spatial coverage with practical wearability; and (4) developing energy-efficient systems for extended monitoring (1–3 h). The incorporation of machine learning (observed in 16.7% of studies) demonstrates potential real-time fatigue classification, though most studies lacked independent validation, limiting algorithm generalizability for brain–computer interface applications. Future development of wearable technology must prioritise rigorous validation across diverse educational settings and student populations, establishment of validated detection thresholds, and demonstration of reliability under naturalistic classroom conditions before widespread implementation.

5. Conclusions

There is an urgent need to harmonise EEG methodologies in mental fatigue research. This systematic review confirms that EEG represents a valuable neurophysiological tool for detecting mental fatigue in educational settings, with theta, alpha, and beta frequency bands serving as consistent biomarkers across studies. However, the analysis reveals significant methodological inconsistencies that substantially compromise the field’s scientific rigour and limit the translation of research findings into practical educational applications.

The findings reveal significant inconsistencies in hardware setups, frequency band definitions, and software platforms that compromise cross-study comparisons and limit reliable biomarker establishment [31,70]. This methodological fragmentation hinders standardised protocol development for educational research, with variability in electrode configurations and band criteria creating substantial barriers to establishing consistent EEG-based fatigue detection systems.

Preprocessing heterogeneity presents another major challenge, with studies varying from sophisticated ICA implementations to basic filtering methods, creating data quality inconsistencies. The diversity in analytical approaches—power spectral analysis, Fourier transforms, machine learning—combined with variable normalisation methods and sample characteristics, compromises replicability and generalizability. Addressing these methodological challenges is crucial for advancing EEG as a reliable educational research tool [17].

Despite these methodological discrepancies, EEG remains a valuable tool for monitoring mental fatigue in educational settings, particularly when combined with advanced analytical techniques. Nevertheless, the applicability of EEG in real-world educational settings remains limited by the lack of standardisation in data acquisition and processing protocols, as well as external factors such as environmental noise and movement artifacts. Addressing these obstacles requires the development of standardised protocols that ensure both scientific rigour and practical feasibility, as detailed in the evidence-based recommendations provided in Section 4.1.

To advance the field, future research should prioritise:

- Methodological harmonisation: Develop global consensus on frequency band definitions (theta: 4–8 Hz; alpha: 8–13 Hz; beta: 13–30 Hz), create standardised preprocessing pipelines (bandpass filtering 0.1–100 Hz, ICA-based artifact removal), and unify statistical modelling strategies with adequate sample sizes (minimum n = 34 for repeated-measures, n = 64 for between-subjects designs). Additionally, it is crucial that studies focus on evaluating the impact of these standardised methods on the accuracy of mental fatigue detection in real-world educational environments, with larger and more diverse samples to ensure the generalisation of results [17].

- Enhanced study design: Expand sample sizes through multi-site collaborations and ensure participant diversity across educational levels and geographical regions to improve external validity and statistical power [49]. Conduct a priori power analyses to ensure adequate statistical power for reliable effect detection.

- Multimodal integration: Integrate EEG with complementary measures of cognitive load, including behavioural performance metrics (reaction time, accuracy) and subjective self-report measures, for a more holistic assessment of mental fatigue that captures neurophysiological, behavioural, and subjective dimensions of this multifaceted construct.

- Advanced analytical approaches: Explore machine learning-based approaches to enhance EEG’s predictive accuracy and applicability in educational contexts [11]. Ensure rigorous validation, including cross-validation procedures, independent test datasets, and evaluation of generalizability across diverse student populations and educational settings.

- Practical implementation guidelines: Develop evidence-based protocols for optimal measurement timing in educational settings (pre/post learning sessions, during extended cognitive tasks), establish minimum recording durations for reliable detection, and create standardised procedures for classroom-based EEG deployment that minimise environmental interference while maximising ecological validity [8,17,59].

Ultimately, the standardisation of EEG-based research on mental fatigue is crucial to bridging the gap between neuroscience and education, ensuring that EEG-derived insights translate into meaningful applications for learning environments. By addressing the methodological challenges identified in this review and implementing the evidence-based recommendations provided, future research can optimise EEG as a robust and scalable tool for assessing cognitive fatigue, supporting personalised learning interventions, and fostering more effective, neuroscience-informed educational practices.

From a neurotechnology perspective, while portable EEG systems demonstrate feasibility for naturalistic cognitive monitoring, widespread implementation requires methodological consensus, validation evidence, and technical standardisation. Addressing the gaps identified in this review through the adoption of standardised protocols for frequency bands, preprocessing pipelines, hardware configurations, and analytical approaches is essential for translating neuroscience research into practical wearable technologies supporting adaptive learning systems and brain–computer interface applications in educational contexts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.A.-M. and T.G.-C.; Methodology, R.A.-M.; Formal Analysis, R.A.-M.; Investigation, R.A.-M., A.R.-M., I.G.-P. and A.D.-R.; Data Curation, R.A.-M. and A.D.-R.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, R.A.-M.; Writing—Review and Editing, A.R.-M., I.G.-P. and T.G.-C.; Visualisation, R.A.-M.; Supervision, A.R.-M., I.G.-P. and T.G.-C.; Project Administration, R.A.-M.; Funding Acquisition, R.A.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation under the Knowledge Generation Projects 2022, grant number PID2022-140903NB-I00. A predoctoral FPI fellowship was awarded to R.A.M. by the Government of Spain (Ministry of Science and Innovation), grant number FPI-UEx/2023/5. This research has been co-financed 85% by the European Union, European Regional Development Fund, and the Government of Extremadura (Managing Authority: Ministry of Finance, GR24082).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study as it constitutes a systematic review of previously published literature and does not involve primary data collection from human or animal participants. The review protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Extremadura (Protocol No. 94/2024, approved on 8 May 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. This study is a systematic review of previously published literature and does not involve primary data collection from human participants.

Data Availability Statement

The review protocol was pre-registered on PROSPERO (CRD42024583941) on 27 August 2024. All data extracted and analysed during the review are available within the manuscript. The PRISMA flow diagram is presented in Figure 1, and the quality assessment is provided in Table A1. No primary data were collected.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI, version GPT-4) to improve the clarity and readability of selected sentences. The authors reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| APC | Article Processing Charge |

| BCI | Brain–Computer Interface |

| EEG | Electroencephalography |

| ERP | Event-Related Potential |

| FFT | Fast Fourier Transform |

| fMRI | Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| ICA | Independent Component Analysis |

| PICOS | Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, Study Design |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PSD | Power Spectral Density |

| PSA | Power Spectral Analysis |

| PROSPERO | International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews |

| α | Alpha (8–13 Hz frequency band) |

| β | Beta (13–30 Hz frequency band) |

| Δ | Delta (1–4 Hz frequency band) |

| θ | Theta (4–8 Hz frequency band) |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Methodological Quality Assessment of Included Studies (Adapted Downs and Black Checklist, 0–28).

Table A1.

Methodological Quality Assessment of Included Studies (Adapted Downs and Black Checklist, 0–28).

| Study | Study Design | Applicable Items | Score (0–28) | Methodol. Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [51] | Exp. cross-sectional | 1–10, 12–13, 16–18, 25–26 | 18 | Fair |

| [52] | Exp. cross-sectional | 1–10, 12–13, 16–18, 25–26 | 17 | Fair |

| [53] | Quasi-Exp. | 1–10, 12–15, 16–18, 25–27 | 22 | Good |

| [23] | Exp. | 1–10, 12–15, 16–20, 25–27 | 25 | Good |

| [54] | Exp. | 1–10, 12–15, 16–20, 25–27 | 24 | Good |

| [55] | Quasi-Exp. | 1–10, 12–15, 16–18, 25–27 | 21 | Good |

| [56] | Randomised controlled trial | 1–27 | 27 | Excellent |

| [57] | Exp. repeated-measures design | 1–10, 12–15, 16–20, 25–27 | 24 | Good |

| [29] | Exp. observational | 1–10, 12–13, 16–18, 25–26 | 20 | Good |

| [58] | Longitudinal | 1–10, 12–15, 16–18, 25–27 | 23 | Good |

| [59] | Exp. | 1–10, 12–15, 16–20, 25–27 | 25 | Good |

| [60] | Exp. cross-sectional | 1–10, 12–13, 16–18, 25–26 | 18 | Fair |

| [61] | Exp. comparative | 1–10, 12–15, 16–20, 25–27 | 24 | Good |

| [62] | Double-blind placebo-controlled crossover | 1–27 | 26 | Excellent |

| [63] | Exp. within-subject | 1–10, 12–15, 16–20, 25–27 | 24 | Good |

| [64] | Exp. cross-sectional | 1–10, 12–13, 16–18, 25–26 | 19 | Fair |

| [65] | Exp. | 1–10, 12–15, 16–20, 25–27 | 23 | Good |

| [66] | Exp. pre–post | 1–10, 12–15, 16–20, 25–27 | 22 | Good |

Note. Scores based on applicable items for each study design. Maximum score = 28. Quality classifications per Hooper et al. [48]: Excellent (26–28), Good (20–25), Fair (15–19), Poor (≤14). Items excluded: randomization items (14–15, 23–24) for non-randomised studies; sample size calculations (27) when not applicable. Inter-rater reliability: Cohen’s κ = 0.87 (substantial agreement). Detailed scoring available upon request.

References

- Biasiucci, A.; Franceschiello, B.; Murray, M.M. Electroencephalography. Curr. Biol. 2019, 29, R80–R85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghojazadeh, M.; Farahbakhsh, M.; Sahrai, H.; Beheshti, R.; Norouzi, A.; Sadeghi-Bazargani, H. The Activity of Different Brain Regions in Fatigued and Drowsy Drivers: A Systematic Review Based on EEG Findings. J. Res. Clin. Med. 2024, 12, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Argüelles, F.; Morales, G.; Egozcue, S.; Pabón, R.M.; Alonso, M.T. Técnicas Básicas de Electroencefalografía: Principios y Aplicaciones Clínicas. In Anales del Sistema Sanitario de Navarra; Gobierno de Navarra, Departamento de Salud: Pamplona/Iruña, Spain, 2009; Volume 32, pp. 69–82. [Google Scholar]

- Ansari, D.; De Smedt, B.; Grabner, R.H. Neuroeducation—A Critical Overview of an Emerging Field. Neuroethics 2012, 5, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juárez-Varón, D.; Bellido-García, I.; Gupta, B.B. Analysis of Stress, Attention, Interest, and Engagement in Onsite and Online Higher Education: A Neurotechnological Study. Comunicar 2023, 31, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redolar-Ripoll, D. Neurociencia Cognitiva, 1st ed.; Editorial Medica Panamericana: Madrid, Spain, 2014; ISBN 978-84-9835-408-9. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; He, X. QI-Pathological Constitution Is Associated with Mental Fatigue in Class among University Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Psychol. 2025, 13, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orovas, C.; Sapounidis, T.; Volioti, C.; Keramopoulos, E. EEG in Education: A Scoping Review of Hardware, Software, and Methodological Aspects. Sensors 2025, 25, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schofield, H.; Hill, R.M.; Feys, O.; Holmes, N.; Osborne, J.; Doyle, C.; Bobela, D.; Corvilain, P.; Wens, V.; Rier, L.; et al. A Novel, Robust, and Portable Platform for Magnetoencephalography Using Optically Pumped Magnetometers. Imaging Neurosci. 2024, 2, imag-2-00283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruer, J.T. Education and the Brain: A Bridge Too Far. Educ. Res. 1997, 26, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hramov, A.E.; Maksimenko, V.A.; Pisarchik, A.N. Physical Principles of Brain–Computer Interfaces and Their Applications for Rehabilitation, Robotics and Control of Human Brain States. Phys. Rep. 2021, 918, 1–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.; Mu, H.; Yuan, Q.; Zhang, Y. Research on Methods for Recognizing and Analyzing the Emotional State of College Students. Front. Soc. Sci. Technol. 2025, 7, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baceviciute, S.; Makransky, G. Remediating Learning from Non-Immersive to Immersive Media: Using EEG to Investigate the Effects of Environmental Embeddedness on Reading in Virtual Reality. Comput. Educ. 2021, 164, 104122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Garza, J.G.; Darfler, M.; Rounds, J.D.; Gao, E.; Kalantari, S. EEG-Based Investigation of the Impact of Classroom Design on Cognitive Performance of Students. arXiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, R.; Li, J. Tai Chi Chuan Teaching on Alleviating Mental Fatigue among College Students: Insights from ERPs. Front. Psychol. 2025, 16, 1561888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Ji, Y.; Gao, Y.; Li, T.; Xu, W. A Novel Stress State Assessment Method for College Students Based on EEG. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 2022, 4565968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Mustieles, M.A.; Lima-Carmona, Y.E.; Pacheco-Ramírez, M.A.; Mendoza-Armenta, A.A.; Romero-Gómez, J.E.; Cruz-Gómez, C.F.; Rodríguez-Alvarado, D.C.; Arceo, A.; Cruz-Garza, J.G.; Ramírez-Moreno, M.A.; et al. Wearable Biosensor Technology in Education: A Systematic Review. Sensors 2024, 24, 2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Calvo, T.; Díaz-García, J. Mental Fatigue and Sport Performance: Current Knowledge and Future Directions. Eur. J. Hum. Mov. 2022, 48, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornsby, B.W.Y.; Naylor, G.; Bess, F.H. A Taxonomy of Fatigue Concepts and Their Relation to Hearing Loss. In Proceedings of the Ear and Hearing; Lippincott Williams and Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2016; Volume 37, pp. 136S–144S. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M.R.; Thompson, C.; Marcora, S.M.; Skorski, S.; Meyer, T.; Coutts, A.J. Mental Fatigue and Soccer: Current Knowledge and Future Directions. Sports Med. 2018, 48, 1525–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Cutsem, J.; Van Schuerbeek, P.; Pattyn, N.; Raeymaekers, H.; De Mey, J.; Meeusen, R.; Roelands, B. A Drop in Cognitive Performance, Whodunit? Subjective Mental Fatigue, Brain Deactivation or Increased Parasympathetic Activity? It’s Complicated! Cortex 2022, 155, 30–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanei, S.; Chambers, J.A. EEG Signal Processing and Machine Learning, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021; ISBN 978-1-119-38694-0. [Google Scholar]

- Barwick, F.; Arnett, P.; Slobounov, S. EEG Correlates of Fatigue during Administration of a Neuropsychological Test Battery. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2012, 123, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, C.S.; Anilkumar, A.C. EEG Normal Waveforms; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Soewardi, H.; Azzahra, F.; Atmaji, C. Electroencephalograph (EEG) Study of Mental Fatigue in Learning the Physics at Senior High School’s Students. In Proceedings of the ASIA International Multidisciplinary Conference (AIMC), Johor Bahru, Malaysia, 12–13 May 2018. [Google Scholar]