Abstract

The current study investigated the relationship between match-play running demands and years of elite hurling experience across the 2021–2023 seasons. Sixty-eight (mean ± SD; Age: 25.5 ± 3.6 years, Mass: 87.5 ± 5.0 kg, Height: 184.2 ± 4.9 cm, Years Elite Experience: 5.3 ± 3.5 years) male elite intercounty hurlers participated. Each participant wore a global positioning system (GPS) unit sampling at 10 Hz (STATSports, Apex, Northern Ireland), and if they played ≥70 min, they were included in the analyses. Distance metrics analysed in metres were total distance (TD), high-speed running (HSR) (≥19.8 km·h−1), sprint distance (≥25.2 km·h−1), and high metabolic load distance (HMLD) (≥25.5 W·kg−1). Participants were split into observational groups based on their years of elite experience: Emerging: 1–3 years, Established: 4–6 years, Seasoned: 7+ years. Emerging players covered less HSR (p = 0.039, ES = 0.25, small) and sprint distance (p = 0.019, ES = 0.28, small) compared to Established players. Seasoned players covered fewer TD and HMLD compared to Emerging players (TD: p < 0.001, ES = 0.31, small; HMLD: p < 0.001, ES = 0.34, small) and Established players (TD: p < 0.001, ES = 0.51, small; HMLD: p < 0.001, ES = 0.32, small). The results identified differences in match-play running demands based on years of elite experience. These findings may guide experience-specific conditioning strategies.

1. Introduction

Hurling is a stick-and-ball invasion team sport played at high intensity intermittent periods of play [1]. Each team has a goalkeeper and 14 outfield players, comprising five positional playing lines (full-back line (FBL), half-back line (HBL), midfield (MID), half-forward line (HFL), and full-forward line (FFL)) [1]. Global positioning systems (GPS) have become widely used within field sports, including hurling at elite, sub-elite, and underage levels for monitoring training loads and identifying match-play running demands [1,2,3,4]. Elite hurlers in All-Ireland Championship (AIC) matches have recently been reported to cover an average total distance of 8172 ± 1003 m, with 1253 ± 258 m of high-speed running (HSR) (≥17 km·h−1) and 406 ± 86 m of sprint distance (≥22 km·h−1) [5]. Comparative studies of match-play running demands observed that elite hurlers covered greater relative total distance than their sub-elite counterparts [6]. Positional match-play running differences have also shown elite hurlers covering greater relative total distance and HSR across the positional lines of HBL, MID, and HFL in comparison to sub-elite hurlers [7]. Running demands at under 17 (U17) level were found to be less than those at elite level [8] but were similar to those of under 21 (U21) level [9]. As hurlers progress from underage and sub-elite levels to elite squads, there is a progressive increase in match-play running demands with which practitioners may prescribe additional training to meet the increased demands of the game [1,6,7,8,9].

Comparable gaps have been demonstrated in running demands within match-play between elite squads in other field-based team sports [10,11]. Differences in training and match loads between first team and under-23 (U23) players from the English Premier League soccer found that first-team players covered significantly more distance above 120% maximal aerobic speed (MAS) and distance between 120% MAS and 85% maximal sprint speed compared to U23 athletes [10]. In further studies examining the match-play running demands of elite senior, sub-elite senior, and elite junior Australian football, and professional, semi-professional, and junior-elite rugby, it was found that the demands of the game were scaled progressively upwards across the competition tiers [11,12]. Many factors may account for the differences in running demands between different squad levels in field sports. The age and maturation of the underage cohort may be a factor [13,14,15]. Biological maturation of an older cohort of players may help them to prepare for and achieve greater distance across relative speed intensity levels of running than younger players [15]. The level of competition may also play a factor. Observed differences between women’s hockey athletes competing in either national or international level competition found an increased running profile with greater HSR covered in international competition compared to national level competition [16]. Similar research in hurling showed increased running profiles in the AIC compared to the national hurling league (NHL) [5].

Factors influencing match-play running demands are not limited to age or maturation and competition level groupings, but also between squad members based on their experience at elite levels in field sports [17,18]. Increased years of playing experience at the elite level of Australian football have been shown to have a positive effect on performance [18], as well as running demand outputs [17]. Athletes who are exposed early on in their elite career to elite game exposure may sustain periods of performance, as they progress over subsequent years and gain more experience on the squad [18]. Despite extensive work on positional, temporal, and between-level running demands in hurling [1], there is no available literature regarding how accumulated years of experience at the elite level influences match-play running demands. Understanding this relationship may guide long-term athlete development and load management strategies amongst elite squads. Therefore, this study aimed to examine whether there was a relationship between match-play running demands and years of playing experience in elite intercounty hurling squads. It was hypothesised that more experienced players would show reduced HSR and sprint demands compared to less experienced players due to familiarity with the match demands.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Approach to the Problem

The current retrospective cohort design examined the variation in multi-season match-play running demands of hurlers with varying levels of playing experience at the elite level. Participants were selected for this study as they were part of their senior elite squad to participate in the NHL and AIC. Data were only included when ≥70 min had been completed by participants. Any participant who started in a match where they were substituted after 70 min of match play had that match’s data included in the dataset. Partial participation (<70 min) was excluded from analysis. In matches that ended as a draw and went to extra-time (2 × 10 min), only data from regulation time, including additional injury time, were included. There was a total of 569 data points meeting the criteria (n = 170: FBL, n = 155: HBL, n = 69: MID, n = 109: HFL, n = 66: FFL) collected across three competitive seasons (2021–2023). Sixty-four matches (n = 33: NHL, n = 31: AIC) were analysed across this period. Playing experience at the elite level was divided into three categories (Emerging: 1–3 years, Established: 4–6 years, and Seasoned: 7+ years) for each season examined. Players were classified based on the number of years they had been part of a senior elite intercounty panel. For example, a player in their first season was assigned “1”, and their experience value increased by one year in each additional season. The groupings chosen were arbitrary and selected based on meaningful stages of career progression while also ensuring sufficient data points in each category. All matches were played between 13.00 and 21.00 h on natural grass pitches, and temperatures ranged from 10 to 24 °C. GPS units were used to track match-play running demands. Participants abstained from physical exercise 24 h before each match.

2.2. Participants

Sixty-eight male elite intercounty hurlers (mean ± SD; Age: 25.5 ± 3.6 years, Mass: 87.5 ± 5.0 kg, Height: 184.2 ± 4.9 cm, Years Elite Experience: 5.3 ± 3.5 years) from multiple teams (n = 2) participated in the study during the 2021–2023 seasons. The teams competed in Division 1 of the NHL throughout the testing period, as well as the AIC. Mean ± SD for ≥70 min match data points per participant across the observational period were 8.4 ± 7.2. Age ± SD for Emerging, Established, and Seasoned were 22.9 ± 2.1, 24.1 ± 1.1, and 28.6 ± 3.0 years, respectively. Both teams followed similar training regimes, with each participant training on pitch 2–3 times per week with their respective team in season and completed 1–2 gym sessions per week. All participants had at least an 8-week pre-season block conducted before the collection of data. All participants in this study had previously represented their county in underage squads or their club at sub-elite level before progressing to their respective senior (adult) elite squad. Each participant had no injuries or illnesses that would preclude them from testing periods. Participants provided written informed consent and were informed that they were free to withdraw from the study at any time. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Technological University Dublin (REC-PG4-20718; Approval date: 25 June 2018).

2.3. Procedures

The GPS unit used in data collection was sampling at 10 Hz (STATSports Apex, Newry, County Down, UK). The validity and reliability of these units had been established in previous literature [19]. The GPS unit was placed in a pouch held in a customised sports vest. The pouch sat between the shoulder blades of participants so as not to restrict upper-body limb movement. The GPS units were used in team training sessions prior to data collection to familiarise the participants with them and the resultant metric outputs. Each participant wore the same unit in each season for all matches in the NHL and AIC in which they competed to avoid inter-unit variability [20]. GPS units were turned on at least 15 min before the participants’ entrance to the playing pitch to establish a satellite lock and for initialisation [21]. GPS data was downloaded and analysed using the STATSports, APEX software (firmware: 4.5.2). Downloaded file data from the GPS units were trimmed to exclude warm-ups and to only include in-match data for each participant. The resultant data were then exported to a spreadsheet for further analysis (Excel, Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA).

Match data collected via GPS included total distance covered, as well as distances at speed intensity zones of absolute HSR (≥19.8 km·h−1), sprint distance (≥25.2 km·h−1), and high metabolic load distance (HMLD) (m) (≥25.5 W·kg−1), which were similar to that of prior research in hurling [6,22]. Metabolic power in team sports has been presented in a theoretical model that accounted for the energetic costs of accelerations and decelerations, which underpin the metric of HMLD [23]. HMLD is a combination metric of the total distances of HSR, accelerations (>2 m·s−2), and decelerations (>2 m·s−2). In the present study, GPS metrics of HSR and sprint distance were set at thresholds greater than those commonly used for same in other GPS-related studies within hurling, as shown in a recent review of literature within the sport [1]. Only one study noted in the review had similar thresholds where HSR and sprint distance began capturing [6]. There are no universally defined thresholds for HSR and sprint distance. However, they were chosen for the current study due to them being the most frequently used thresholds in a review of sprinting and HSR in adult professional soccer recently [24]. They also reflected the standardised settings in the GPS system used in the current study, which are commonly used by practitioners in the field [24]. HSR and sprint distance are often set at lesser thresholds in field sport studies, which may not reflect the physical demands of the game [25]. All match data were initially analysed together to establish the running demands at the elite level of the participating cohort before the data were separated into playing experience bands.

2.4. Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using a statistical software package (SPSS v29, IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Means, standard deviations (SD), and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were run for the GPS metrics of total distance, HSR, sprint distance, and HMLD. Normality was checked per variable using the Shapiro–Wilk test. A one-way multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) evaluated the effect of experience group on total distance, HSR, sprint distance, and HMLD. Assumptions of homogeneity of covariance matrices were evaluated using Box’s M test, followed by Pillai’s trace. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Bonferroni-adjusted post hoc tests identified pairwise differences. For all pairwise comparisons, pairwise mean differences, 95% CI, and Cohen’s d effect sizes (ES) were calculated to describe the differences between groups, with d < 0.20, 0.20–0.59, 0.60–1.19, 1.20–1.99, and ≥2.00 interpreted as follows: trivial, small, moderate, large, and very large differences, respectively [26]. Given the sample size (n = 68) divided into three groupings, small differences between groups may not have been detectable. Results are interpreted on ES and CI, giving a conservative assessment of practical significance.

3. Results

Independent of years of experience groupings, the observed match-play running demands of elite hurling were 8540 ± 1066 m (110 ± 14 m·min−1), 764 ± 200 m (10 ± 3 m·min−1), 160 ± 85 m (2 ± 1 m·min−1), and 1729 ± 337 m (22 ± 4 m·min−1), for the metrics of total distance, high-speed running (HSR), sprint distance, and high metabolic load distance (HMLD), respectively, in the current study. Mean ± SD for time played per match per participant, inclusive of additional injury time, was 77 ± 2 min.

Box’s M test indicated that the assumption of homogeneity of covariance matrices was violated, Box’s M = 335.770, F (140, 13,000.207) = 2.183, p < 0.001. As the assumption was violated, Pillai’s trace was run. The multivariate effect of experience groups was significant, Pillai’s Trace = 0.120, F (8, 1104.000) = 8.842, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.060. Table 1 presents the GPS-derived match-play running demands in elite hurling for each experience group. Significant differences between groupings are noted. Data are mean ± SD.

Table 1.

Running demands of Emerging, Established, and Seasoned players in elite hurling match play.

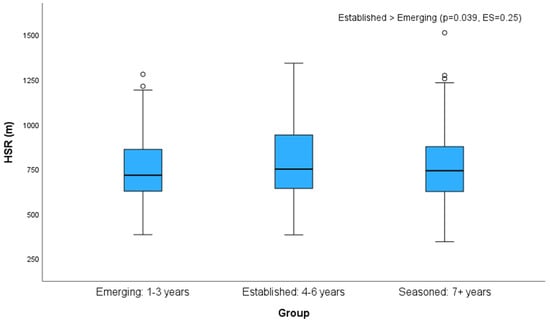

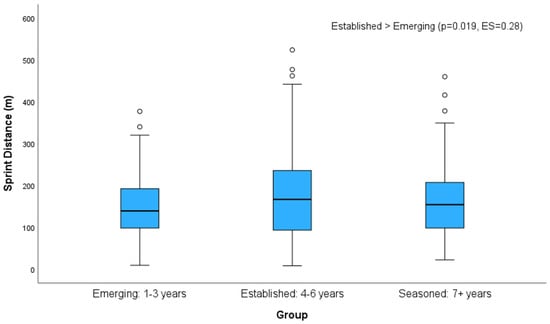

The Emerging group covered significantly less distance across HSR (p = 0.039, ES = 0.25, small) and sprint distance (p = 0.019, ES = 0.28, small) in comparison to the Established group across the observational period, with no significant differences observed for total distance (p = 0.057, ES = 0.22, small) and HMLD (p > 0.99, ES = 0.04, trivial) between them. Differences were also observed between the Emerging group and the Seasoned Group with Emerging having covered significantly more total distance (p < 0.001, ES = 0.31, small) and HMLD (p < 0.001, ES = 0.34, small), with no differences observed between them in HSR (p > 0.99, ES = 0.05, trivial) or sprint distance (p = 0.901, ES = 0.12, trivial). The Established group also demonstrated significantly more total distance (p < 0.001, ES = 0.51, small) and HMLD (p < 0.001, ES = 0.32, small) than the Seasoned group, with no significant differences in HSR (p = 0.081, ES = 0.2, small) and sprint distance (p = 0.145, ES = 0.18, trivial). The effect sizes of all identified significant differences between years of experience groupings were interpreted to be “small” effects (ES = 0.25–0.51). Figure 1 and Figure 2 present boxplots illustrating the distributions of HSR and sprint distance, respectively, across all groups. They highlight the significant differences observed between the Emerging and Established groups across these match-play running demand metrics.

Figure 1.

Boxplot of experiential difference of high-speed running in elite hurling match play. HSR high-speed running.

Figure 2.

Boxplot of experiential difference of sprint distance in elite hurling match play.

Bonferroni-adjusted post hoc comparisons showed several significant differences between experience groups across match-play running demand metrics. Table 2 represents Bonferroni-adjusted comparisons between groups across total distance, HSR, sprint distance, and HMLD. Data are displayed as pairwise mean differences (Experience Group (1) − Comparative Experience Group (2)) with corresponding p-values and 95% CI for each pairwise comparison.

Table 2.

Bonferroni-adjusted post hoc comparison of experiential groups for GPS-derived match-play running demands. * Significant difference (p < 0.05) between groups.

4. Discussion

The current study observed how years of playing experience at the elite level in hurling affect match-play running demands. Previous research in hurling identified gaps in running demands and performance profiles between sub-elite, underage, and elite levels of play [6,8,9,27]. This study adds to the existing knowledge base of match-play demands of elite hurling [1]. The main results from this study showed that individuals in the early years of experience in the Emerging group do not cover the same distances in HSR and sprint distance as those in the Established group. As athletes gained more experience and entered the Seasoned group, they had a decline in total distance and HMLD compared to the other two groups in the study.

Lower volumes of HSR and sprint distance covered by the Emerging group compared to the Established group suggest there is a transitional adjustment period to elite levels of play during the early years of integration into a senior intercounty squad. Elite hurling requires a high aerobic capacity [1], and studies in hurling and Gaelic football have shown that elite athletes perform better in the Yo-Yo intermittent recovery test level 1 (Yo-YoIR1) than sub-elite or underage players [27,28]. This matches research showing that athletes with higher VO2max and better running economy can maintain higher speeds for longer and recover more effectively between efforts [29,30]. The gap between Emerging and Established athletes may, therefore, show that underage or sub-elite athletes may not have developed the aerobic and neuromechanical needs for repeated high-speed running and sprinting actions when entering elite squads. Transitional athletes may be more likely to also have higher levels of muscle-damage markers like creatine kinase (CK), which can impair neuromuscular function and lower the ability to run at high intensity during novel training situations [31]. As hurlers progress from sub-elite or underage to elite play, the duration of competitive match-play changes from 60 min of play to 70 min, respectively, excluding additional time [32,33]. Emerging players might experience greater neuromuscular strain and muscle damage when adjusting to elite match play, suppressing their ability to repeat intermittent HSR and sprint outputs. This suggests that sub-elite and underage athletes may need additional conditioning in HSR and sprint distance when elevated to elite squads to withstand the demands of match play. Increases in their physical fitness may aid in greater match outputs and less neuromuscular fatigue [34]. Appropriate physical preparation for underage groups must be managed carefully, as increases in training may increase the risk of injury, hindering long-term development in meeting the physiological demands of the game [35].

Pacing strategies used by participants in the Emerging group might also explain the differences in HSR and sprint distance. Athletes in team field-based sports use pacing strategies to distribute their physiological output across the duration of a match based on the perceived demands required [36]. A proposed pacing model in team sports suggests that micro-pacing strategies have an outcome on overall macro-pacing strategies that they choose prior to the beginning of the match [37]. Previous experience of game duration and activities involved has been shown to affect athletes’ overall pacing strategy during match-play [36,37]. The tactical maturity of the Emerging group may not be as refined as that of more experienced groups. Recent literature on pacing strategies suggests that it interacts with neuromuscular adaptations and is a learned skill [38]. Emerging hurlers at elite level may not have developed nuanced abilities to distribute their efforts over a 70 min game. Early exposure to full-match demands at the elite level could be used by practitioners in developing task experience in Emerging athletes. Structured exposure to match-like situations may also speed up learning of pacing skills and neuromuscular changes. This may contribute to increasing their HSR and sprint outputs across a full match.

Athletes with more experience of match-play running demands may be able to anticipate the relative demands of the game better than less experienced players. This allows them to adjust their micro-pacing strategies accordingly while working towards their macro-pacing plan [37]. Of note, there were no significant differences noted in HSR and sprint distance in the Seasoned group compared to the less experienced groups in the current study. From an ecological dynamics standpoint, the pacing strategy of the Seasoned group may have been aimed towards greater running intensities with reduced focus on less intense running activities. Seasoned players may exploit environmental factors and self-regulate their pace and effort distribution to preserve performance in match play [39,40]. Players who adopt whole-match pacing strategies are more likely to be less fatigued and can preserve key energy substrates for the later stages of a match [36]. Lower volumes of total distance and HMLD observed in the Seasoned group compared to Emerging and Established groups may reflect refined pacing strategies rather than reduced physical capabilities. Distinguishing between the effects of chronological age and years of elite experience is important. Although age-related decrements in total distances are documented in professional soccer [41,42,43], accumulated match experience and repeated exposure to high-intensity actions also lead to neuromuscular adaptations and improvements in pacing skills [36,37,38,39,40]. Reduced total distance or HMLD in Seasoned players likely reflects a combination of refined pacing, neuromuscular efficiency, and strategic load management, rather than a loss of capacity with age. Practitioners may use the current results to prioritise the conditioning of Seasoned players to focus on high velocity running metrics such as HSR and sprint distance in load monitoring, with priority placed on recovery capacity between repetitions.

There were numerous limitations to the current study, given its novelty. Firstly, the groupings of playing experience chosen for the current protocol were arbitrary in nature and have not appeared in literature relating to elite-level hurling. Future research may look at individual years of experience across the playing span of elite-level hurlers, as well as in relation to their age. It may also be pertinent to define further what is meant by experience when it comes to match play, as it is at the discretion of the team manager who plays from match to match. Although participants in the current study were in the Emerging group and may have required full match experience to understand the demands of the game, it did not guarantee that they would play a full match in that period. The current study did not account for actual minutes played per season or involvement in previous matches where participants undertook less than 70 min of match time. This may have introduced selection bias as players in any given game may have had differing levels of fitness or tactical role. Age ranges of the groupings were narrow, which may have biased the interpretation of differences. The current research did not also consider the positional aspects of hurling (FBL, HBL, MID, HFL and FFL), and aggregated results only based on years of experience, so as to not dilute the sample size further. Future research may examine the effect of years of elite experience on match-play running demands per position. Decrements in hurling match-play running performance across positional lines have been researched in hurling previously [44], not yet in relation to how pacing activities may influence performance. Subsequent research should explore how pacing activities, informed by individual years of experience or by the proposed groupings on an elite hurling panel, influence match-play temporal running demands. The current study did not also consider internal (heart rate, rate of perceived exertion, CK) or external (opposition quality, match importance, weather, coaching philosophy, or style of play) contextual factors. The sample was limited to two teams, which were non-random and may not be representative of all teams or the competition level in elite hurling. Each team in this study also may have employed different coaching styles across seasons within each team and contextually between teams, which was not examined.

5. Conclusions

This current study has shown that years of elite experience are associated with small ES differences in match-play running performance among elite hurlers. The Emerging group had less HSR and sprint distance than the Established group, while the Seasoned group had less total distance and HMLD compared to both Emerging and Established groups. The results suggest that pacing strategies need to be developed in transitional Emerging players early on in their elite careers with targeted conditioning and full match exposure to meet the demands of 70 min of elite match play. Experience-related changes in pacing, decision-making, and neuromuscular control are important factors in match-running profiles. These elements should be clearly included in performance planning.

The findings from this study may be used to guide training strategies to aid practitioners when prescribing conditioning and match-specific drills. Training sessions could be tailored to specific experience needs. For Emerging athletes, sessions could include structured repeated-sprint training, high-speed exposure, and small-sided games that mimic 70-min match demands. This approach aims to speed up pacing skill development and neuromuscular adaptation. For Established athletes, individual work should focus on improving high-velocity running patterns, maintaining sprint mechanics, and boosting decision-making under varying conditions. For Seasoned athletes, sessions should emphasize high-quality, low-volume, high-velocity actions, monitoring neuromuscular recovery, and custom-paced conditioning to maintain performance while minimizing fatigue. Practitioners should also be aware of how pacing strategies may have an impact on match-play running demands across years of playing experience. Understanding that the pacing strategies of Emerging hurlers may be underdeveloped due to their perception of a 70-min match at the elite level, underpins the importance of providing full match exposure early in their elite careers. Training loads could also be monitored and adapted based on years of experience at the elite level, and not just by age. Progressive exposure to the running demands of a 70 min match could help to inform load management and injury prevention strategies within the Emerging group.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.P.C., K.D.C. and D.Y.; methodology, C.P.C., K.D.C., D.Y. and G.C.; formal analysis, C.P.C.; investigation, C.P.C., J.K., S.M. and G.C.; data curation, C.P.C., J.K. and S.M.; writing—original draft preparation, C.P.C.; writing—review and editing, C.P.C., K.D.C., D.Y. and S.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Technological University Dublin (REC-PG4-20718; Approval date: 25 June 2018).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the management, backroom team, and players of the hurling teams investigated within the current manuscript, who provided their time and commitment to the current investigation across the observational period.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FBL | Full-back line |

| HBL | Half-back line |

| MID | Midfield |

| HFL | Half-forward line |

| FFL | Full-forward line |

| NHL | National Hurling League |

| AIC | All-Ireland Championship |

| U17 | Under 17 |

| U21 | Under 21 |

| U23 | Under 23 |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| HSR | High-speed running |

| HMLD | High metabolic load distance |

| MAS | Maximal aerobic speed |

| ES | Effect size |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| MANOVA | Multivariate analysis of variance |

References

- Collins, K.; Reilly, T.; Malone, S.; Keane, J.; Doran, D. Science and Hurling: A Review. Sports 2022, 10, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgeman, L.A.; Gill, N.D. The use of global positioning and accelerometer systems in age-grade and senior rugby union: A systematic review. Sports Med. Open 2021, 7, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennessy, L.; Jeffreys, I. The current use of GPS, its potential, and limitations in soccer. Strength Cond. J. 2018, 40, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisbey, B.; Montgomery, P.G.; Pyne, D.B.; Rattray, B. Quantifying movement demands of AFL football using GPS tracking. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2010, 13, 531–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, B.; Young, D.; Collins, K.; Malone, S.; Coratella, G. The Between-Competition Running Demands of Elite Hurling Match-Play. Sports 2021, 9, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, D.; Mourot, L.; Coratella, G. Match play performance-comparisons between elite and sub-elite hurling players. Sport Sci. Health 2018, 14, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keane, J.; Malone, S.; Gillan, E.; Young, D.; Coratella, G.; Collins, K. The influence of playing standard on the positional running performance profiles during hurling match-play. Sport Sci. Health 2023, 19, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, D.; Mourot, L.; Beato, M.; Coratella, G. Match-play demands of elite U17 hurlers during competitive matches. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2020, 34, 1982–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, D.; Mourot, L.; Beato, M.; Coratella, G. The match heart rate and running profile of elite under-21 hurlers during competitive match-play. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2018, 32, 2925–2933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavanagh, R.; Carling, C.; Malone, S.; Di Michele, R.; Morgans, R.; Rhodes, D. ‘Bridging the gap’: Differences in training and match physical load in 1st team and U23 players from the English Premier League. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2024, 19, 1011–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, S.J.; Watsford, M.L.; Rennie, M.J.; Spurrs, R.W.; Austin, D.; Pine, M.J. Match-play movement and metabolic power demands of elite youth, sub-elite and elite senior Australian footballers. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0212047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLellan, C.P.; Lovell, D.I. Performance analysis of professional, semiprofessional, and junior elite rugby league match-play using global positioning systems. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2013, 27, 3266–3274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gastin, P.B.; Tangalos, C.; Torres, L.; Robertson, S. Match running performance and skill execution improves with age but not the number of disposals in young Australian footballers. J. Sports Sci. 2017, 35, 2397–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundersen, H.; Riiser, A.; Algroy, E.; Vestbøstad, M.; Saeterbakken, A.H.; Clemm, H.H.; Grendstad, H.; Hafstad, A.; Kristoffersen, M.; Rygh, C.B. Associations between biological maturity level, match locomotion, and physical capacities in youth male soccer players. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2022, 32, 1592–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rábano-Muñoz, A.; Asian-Clemente, J.; Sáez de Villarreal, E.; Nayler, J.; Requena, B. Age-related differences in the physical and physiological demands during small-sided games with floaters. Sports 2019, 7, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, D.H.; Cormack, S.J.; Coutts, A.J.; Aughey, R.J. International field hockey players perform more high-speed running than national-level counterparts. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2012, 26, 947–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, G.M.; Gabbett, T.J.; Naughton, G.A.; McLean, B.D. The effect of intense exercise periods on physical and technical performance during elite Australian football match-play: A comparison of experienced and less experienced players. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2016, 19, 596–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gastin, P.B.; Fahrner, B.; Meyer, D.; Robinson, D.; Cook, J.L. Influence of physical fitness, age, experience, and weekly training load on match performance in elite Australian football. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2013, 27, 1272–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beato, M.; Coratella, G.; Stif, A.; Dello Iacono, A. The validity and between-unit variability of GNSS units (STATSports Apex 10 and 18 Hz) for measuring distance and peak speed in team sports. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jennings, D.; Cormack, S.; Coutts, A.J.; Boyd, L.J.; Aughey, R.J. Variability of GPS units for measuring distance in team sport movements. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2010, 5, 565–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maddison, R.; Ni Mhurchu, C. Global positioning system: A new opportunity in physical activity measurement. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2009, 6, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, D.; Malone, S.; Collins, K.; Mourot, L.; Beato, M.; Coratella, G. Metabolic power in hurling with respect to position and halves of match-play. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0225947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osgnach, C.; Poser, S.; Bernardini, R.; Rinaldo, R.; Di Prampero, P.E. Energy cost and metabolic power in elite soccer: A new match analysis approach. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2010, 42, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualtieri, A.; Rampinini, E.; Dello Iacono, A.; Beato, M. High-speed running and sprinting in professional adult soccer: Current thresholds definition, match demands and training strategies. A systematic review. Front. Sports Act. Living 2023, 5, 1116293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, B.W.; Talpey, S.W.; James, L.P.; Opar, D.A.; Young, W.B. Common high-speed running thresholds likely do not correspond to high-speed running in field sports. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2023, 37, 1411–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, W.G. Spreadsheets for analysis of controlled trials, with adjustment for a subject characteristic. Sportscience 2006, 10, 46. [Google Scholar]

- Keane, J.; Malone, S.; Keogh, C.; Young, D.; Coratella, G.; Collins, K. A comparison of anthropometric and performance profiles between elite and sub-elite hurling players. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, M.; Malone, S. Yo-Yo intermittent recovery test performance in subelite gaelic football players from under thirteen to senior age groups. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2016, 30, 3187–3193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchheit, M. The 30-15 intermittent fitness test: Accuracy for individualizing interval training of young intermittent sport players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2008, 22, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joyner, M.J.; Coyle, E.F. Endurance exercise performance: The physiology of champions. J. Physiol. 2008, 586, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.R.; Rumpf, M.C.; Hertzog, M.; Castagna, C.; Farooq, A.; Girard, O.; Hader, K. Acute and residual soccer match-related fatigue: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2018, 48, 539–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, D.; Collins, K.; Mourot, L.; Coratella, G. The matchplay activity cycles in elite u17, u21 and senior hurling competitive games. Sport Sci. Health 2019, 15, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, D.; Coratella, G.; Malone, S.; Collins, K.; Mourot, L.; Beato, M. The match-play sprint performance of elite senior hurlers during competitive games. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0215156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, R.D.; Gabbett, T.J.; Jenkins, D.G. Influence of playing standard and physical fitness on activity profiles and post-match fatigue during intensified junior rugby league competition. Sports Med. Open 2015, 1, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duggan, J.D.; Moody, J.; Byrne, P.; McGahan, J.H.; Kirszenstein, L. Considerations and guidelines on athletic development for youth Gaelic athletic association players. Strength Cond. J. 2022, 44, 76–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldron, M.; Highton, J. Fatigue and pacing in high-intensity intermittent team sport: An update. Sports Med. 2014, 44, 1645–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, A.M.; Noakes, T.D. Dehydration: Cause of fatigue or sign of pacing in elite soccer? Sports Med. 2009, 39, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menting, S.G.P.; Edwards, A.M.; Hettinga, F.J.; Elferink-Gemser, M.T. Pacing behaviour development and acquisition: A systematic review. Sports Med. Open 2022, 8, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilar, L.; Araújo, D.; Davids, K.; Button, C. The role of ecological dynamics in analysing performance in team sports. Sports Med. 2012, 42, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, C.T.; McKeown, I.; O’Sullivan, M.; Robertson, S.; Davids, K. Theory to practice: Performance preparation models in contemporary high-level sport guided by an ecological dynamics framework. Sports Med. Open 2020, 6, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Calvo, T.; Huertas, F.; Ponce-Bordón, J.C.; Del Campo, R.L.; Resta, R.; Ballester, R. Does player age influence match physical performance? A longitudinal four-season analysis in Spanish Soccer LaLiga. Biol. Sport 2023, 40, 1097–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rey, E.; Costa, P.B.; Corredoira, F.J.; de Rellan Guerra, A.S. Effects of age on physical match performance in professional soccer players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2023, 37, 1244–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sal de Rellán-Guerra, A.; Rey, E.; Kalén, A.; Lago-Peñas, C. Age-related physical and technical match performance changes in elite soccer players. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2019, 29, 1421–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, D.; Beato, M.; Mourot, L.; Coratella, G. Match-play temporal and position-specific physical and physiological demands of senior hurlers. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2020, 34, 1759–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.