Abstract

The pulp and paper mill industry in Corner Brook, Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada produces 150 Mg/day of pulp and paper mill sludge (PPMS) with a high moisture content (70–80%). Instead of the current practice of burning, PPMS may be repurposed as vermicompost. However, the optimum population density of Eisenia fetida to maximize the bioconversion process and its influence on population dynamics are largely unknown. The current study aimed at determining how stocking densities affect the vermicomposting time, vermicompost quality, and population dynamics of E. fetida. By using three stocking densities—1.13 g (TL), 2.04 g (TM), and 3.01 g (TH)—the E. fetida per kg of PPMS and the quality of the vermicompost were determined by chemical analysis followed by a germination test and bioassay on Raphanus sativus seedlings. The total vermicompost produced in TL (66.3%) and TM (68.8%) made the bioconversion process quicker in 60 days. The addition of more E. fetida (TH) delayed the process of vermicomposting by up to 90 days (p < 0.003). Overall, 0.87 (TM) E. fetida/L of PPMS was found to be the optimum population density for obtaining the best quantity and quality of vermicompost. The highest earthworm biomass was harvested in TL, followed by TM and TH, as 3.2, 1.3, and 0.9-fold, respectively, compared to the introduced biomass in 60 days (p < 0.008). The mean growth rate (2.6 mg/worm/day), biomass gain (3.49 mg/g), and reproduction rate (3.9 cocoon/worm) were also significantly higher (p < 0.023) in TL compared to TM and TH in 60 days. Therefore, the present study shows the importance of using an optimum stocking density to maximize the bioconversion process in PPMS, especially in cooler regions.

1. Introduction

Pulp and paper mills are considered one of the most important industries, supplying a variety of products all over the world and finding versatile applications. According to a report of the Statista Research Department, a total of 417.3 million Mg of paper and paperboards, with a value of 351.53 billion USD, was manufactured in 2022 [1]. Moreover, global paper products are relatively stable and remain at an average of 400 million Mg annually. However, every 1.0 Mg (Mg—megagrams (=tons)) of paper mill product generates 4.3–40 kg of pulp and paper mill sludge (PPMS) on a dry mass basis [2]. Globally, pulp and paper mills contribute to a large amount of biomass (PPMS) production, and nearly 40% (85 million Mg) of it is discarded to landfills, creating negative environmental impacts [3]. In Canada, 33.3% of the total waste is paper waste, and around 6 million Mg of paper and paper boards is used annually [4]. In 2019, facilities in Canada’s pulp and paper sector consisted of chemical pulp mills (27%), mechanical pulp mills (8%), and paper manufacturing mills (65%). According to the Forest Products Association of Canada (FPAC), these facilities contributed 46%, 30%, and 24% to the total production, respectively [5]. Pulp and paper production generates various wastes, with approximately 87% being PPMS and 13% comprising waste chemicals, gaseous emissions, and impurities [6]. In 2019, around 36% of paper-related waste was diverted to compost, reusing, and recycling, while the remaining portions were burnt and landfilled. Disposing of industrial PPMS in landfills is costly, results in nutrient loss due to the anaerobic processes, and emits greenhouse gases, contributing to climate change [7].

Vermicomposting is a popular recycling method adopted globally as one of the organic waste management techniques [8]. It is gaining popularity for its ability to convert waste into useful products for plant growth, serving as an alternative to chemical fertilizers. Earthworms are incubated in pre-decomposed organic wastes, resulting in a final product called “vermicompost” that is richer in plant nutrients and growth hormones [9], with a better quality and reduced contaminants compared to conventional composting [10]. During the process of vermicomposting, soil is not required and organic matter functions as both a food and substrate for earthworms, wherein the process can be mostly successfully completed by epigeic earthworms, rather than endogeic and anecic types of earthworms. Therefore, epigeic earthworms (Eisenia fetida—Savigny, Eisenia andrei—Bouché, Dendrobaena veneta—Rosa, Dendrobaena hortensis—Michaelsen, Eudrilus eugeniae—Kinberg, and Perionyx excavatus—Perrier) and their potential use have been evaluated in several past studies. E. andrei and E. fetida are the species most used and favored in the vermicomposting process worldwide, due to their wide range of tolerance towards different environmental conditions [11,12]. E. fetida is one of the widely used bioreactors due to its high reproduction rate, small size, and adaptability [13]. An ideal humidity of 80–90% [14], pH of 7.5–8.0 [15,16], and ambient temperature of 13–25 °C [13] are essential for the activity and development of E. fetida.

Adding structural amendments and conducting initial aerobic composting of PPMS with frequent turning for two weeks can provide additional benefits, such as reducing the concentration of various potential toxic elements in the vermicompost and increasing the vermicomposting rate [17]. Moreover, epigeic earthworms require suitable organic matter and a high moisture content for successful growth and reproduction. However, producing high-quality vermicompost depends on the nature of the raw material used, the type of vermibed preparation, and the density of earthworms [18]. Maintaining an optimum stocking density of E. fetida ensures the stability of the vermicomposting system and overall efficiency. A lower stocking density leads to a reduction in the decomposition rate of organic waste and an inefficient utilization of resources, while a higher stocking density leads to an insufficient food supply to E. fetida due to competition, thus decreasing the growth and production in the vermicomposting system [19]. Different industrial wastes, including municipal solid waste, have been vermicomposted using 10 earthworms per kg and resulted in improved nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K) [20]. A stocking density of 25 g/kg of mixed fly ash, wastepaper, and cow manure was reported to accelerate decomposition and enrich nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) [21]. Similarly, a higher degree of humification resulted from vermicomposting a mixture of cow manure and wastepaper with a 12.5 g/kg stocking density [22]. Moreover, 5–7 E. fetida/kg of banana straw and kitchen vegetable waste resulted in a significant increase in microbial activity and nutrients [19,23]. Therefore, the influence of the stocking density varies with the waste material used, as they positively promote the degradation process. However, concerns exist that either growing earthworms in a natural habitat or using wild earthworms can result in high levels of bioaccumulation of toxic residues such as heavy metals, herbicides, antibiotics, and pesticides [23], which leads to risks of transferring toxic substances to and up the food chain (poultry/fishes to humans). Furthermore, as the distribution and abundance of earthworms are seasonal in natural habitats, they cannot satisfy the global feed demand as an animal feed supplement. Therefore, growing earthworms in a substrate tested for its toxicity and heavy metals has become a trend serving to meet global demands and through which a biomagnification of pollutants or hazards is being eliminated. Furthermore, incorporating earthworms into the composting process (microorganisms and earthworms) can support the process of waste reduction and recycling for the nutrient supply, while producing earthworm biomass for alternative non-conventional animal feed sources for the poultry and aquaculture sectors. Moreover, E. fetida could convert pulp and paper mill sludge (PPMS) into vermicompost in a relatively short retention period, which is largely associated with its high organic matter content; however, E. fetida population dynamics may vary depending on the stocking density [24]. As a first attempt, the current study aimed to determine the optimal stocking density of E. fetida required to achieve efficient vermicomposting of PPMS, as the substrate collected from Corner Brook Pulp and Paper Limited (CBPPL), Newfoundland and Labrador (NL), Canada. Secondly, this study investigated E. fetida population responses under different stocking densities by assessing key population attributes at two harvesting stages of the vermicomposting process, with the objective of identifying stocking densities that support effective and stable E. fetida populations during PPMS bioconversion.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collection of Pulp and Paper Mill Sludge (PPMS) and Eisenia fetida

PPMS (Table 1) for the current study was collected from Corner Brook Pulp and Paper Limited (CBPPL), located on Mill Road, Corner Brook, Newfoundland and Labrador (NL), Canada. Healthy commercial earthworms—E. fetida—were purchased from J&C Farm, located in St. John’s, NL, Canada.

Table 1.

Physicochemical characteristics of pulp and paper mill sludge (PPMS) used as the vermicomposting substrate (mean ± SE, n = 3).

2.2. Vermicomposting Experiment

A total of nine (9) cylindrical plastic pails (17.2 L) were set up, and 5.5 kg of air-dried PPMS was poured into each vermibin. The vermibins were watered, and we allowed 2 weeks for pre-composting (initial aerobic decomposition) while microbes initiated the biochemical breakdown of the organic polymers into their monomeric units to release energy and nutrients, which would later be utilized by the earthworms to facilitate the mechanical and physical breakdown of biomass into smaller particles [25]. The pre-composting period facilitates the removal of noxious gases such as ammonia and methane [26,27] 75] and eliminates potential risks to earthworms [26]. The PPMS was mixed weekly, maintaining the moisture percentage of 80–90% (mass basis). After two complete turnings of PPMS, vermibins were arranged in a Completely Randomized Design (CRD) for three treatments and triplication. E. fetida was introduced on the top of each vermibin as per the following treatments: TL (8 earthworms—5.98 g), TM (15 earthworms—9.62 g), and TH (22 earthworms—11.40 g) in 5.5 kg of PPMS. Each bin was covered, and we maintained the moisture content by spraying water weekly. At 60 and 90 days, adults, juveniles, and cocoons were separated by hand sorting and weighed and counted using an electronic balance. PPMS in each vermibin was sieved using a 2 mm sieve and weighed for both non-composted and composted PPMS [17].

The decomposition percentage was calculated using the following Equation (1) [27]:

where D = decomposition percentage (%); W1 = total initial mass of organic material; W2 = mass of material after decomposition.

2.3. Chemical Analysis of Vermicompost Samples

Temperature, pH, electrical conductivity (EC), organic matter content (OM), and moisture content (MC) were recorded on a weekly basis. The pH and EC of solids were determined following standard methods [15,16] using a solid-to-deionized (DI) ratio of 1:5 (WW). The MC of the samples was measured using the oven-dry method at 80 °C for three days [28]. Oven-dried samples were used for measuring OM by the loss of ignition method [29], where the samples were kept in a muffle furnace and ignited at 550 °C for 1 h. Triplicate samples were analyzed in the Soil, Plant and Feed Laboratory, St. John’s for their total carbon, nitrogen, potassium, phosphorus, calcium, iron, and sodium. The Biodegradability Coefficient (Kb) was calculated using Equation (2) relating to the changes in initial and final OMs of PPMS by using the following equation [15,30]:

where Kb = biodegradability coefficient; OMi = initial organic matter content; OMf = final organic matter content of the PPMS.

We pre-digested 0.5 g of oven-dried samples with HCL (3 mL) and HNO3 (9 mL) for about 10 min with a microwave digestor (CEM System, MARS-6, Matthews, NC, USA). The resultant samples were followed with two steps after pre-digestion: in the first stage, a 10 min ramp to 180 °C, and in the second stage, kept for 20 min at 1600 W. By using an inductivity coupled plasma spectrometer (ICP-MS) (iCAP-6300 Series, Thermo Scientific, Cambridge, UK), the resultant digested and filtered samples were analyzed. ICP-MS analysis was continued at the Grenfell Campus and AGAT Laboratory, St. John’s, NL. Each parameter was calculated on a dry basis with the statistical standard deviation (SD) and error (SE).

2.4. Bioassay of Vermicompost

A common test for seed varieties—the “phytotoxicity test”—was performed, choosing organic radish (Raphanus sativus L.) as the test seeds. PPMS and vermicompost extracts were prepared by adding 10 g of samples with 100 mL of DI to a 150 mL conical flask. They were shaken at 150 rpm for 30 min in a mechanical shaker, and we allowed 72 h for settling the solution. Next, the solutions were filtered and labeled [31]. Twenty (20) R. sativus seeds were placed in between two filter papers in Petri dishes. Finally, 10 mL of filtered extracts was added, dishes were covered, and we kept them in the dark for four days at room temperature. Simultaneously, nine (09) control experiments were set up with 10 mL of DI water. The total number of germinated seeds were counted in every 12 h interval, the radical length was measured after four (4) days, and the hypocotyl length of seedlings was measured after 6 days of germination.

The following equation was used to calculate the relative seed germination (RSG; Equation (3)), relative radical growth (RRG; Equation (4)), germination index (GI; Equation (5)), germination percentage (GP; Equation (6)), and seedling vigor index (SVI; Equation (7)) [32]. The seed germination percentage and the speed of germination were measured by means of GI [33,34].

where RSG = relative seed germination; Ns = number of seeds germinated in sample; Nc = number of seeds germinated in control.

where RRG = relative radical growth; RLs = total radical length of germinated seeds (sample); RLc = total radical length of germinated seeds (control).

where FGP = final germination percentage; NGs = number of seeds germinated (sample); N = total number of seeds taken for the test.

where SVI = seedling vigor index; SL = seedling length (cm).

where CVG = coefficient of velocity of germination; Ny = number of seeds germinated each day; Ty = number of days from seeding corresponding to N.

where MGT = mean germination time.

where GRI = germination rate index, G1 = germinated seeds at the first day after sowing; G2 = germinated seeds at the second day after sowing.

where GE = germination energy.

where TSG = time spread of germination; (Df − DL) = time in days between the first and last germination events occurring in a seed lot.

2.5. Determination of Growth Performance of Eisenia fetida

The age distribution of the total population of E. fetida collected from each wave of sampling (all the treatments and replicates) was separated in the soil laboratory into adults (well-developed clitellum), non-clitellate individuals (or pre-clitellate with tubercula pubertatis), juveniles, hatchlings (<0.01 g), and cocoons on days 60 and 90. The following equations were used to calculate the growth rate (G) as given in Equation (13).

where G = growth rate; T = time (number of days); n = number of earthworms introduced; B1 = initial biomass of earthworms (mg); B2 = maximum biomass obtained by earthworms (mg).

where BMG = biomass gain per unit waste (mg/g); W = total quantity of PPMS used (g).

2.6. Determination of Reproductive Performance of Eisenia fetida

We transferred 10 freshly laid cocoons into a Petri dish containing moist filter paper at 24 ± 2 °C and 75 ± 5% relative humidity (RH). Other sets of 10 cocoons were moved to a small, dark plastic container measuring 0.1 m × 0.05 m × 0.05 m, which contained PPMS as the bedding material, in which the adults were grown. Both units were under observation to record the emergence of hatchlings. Once we had a set of hatchlings, they were separated manually using a soft painting brush and counted to determine the hatching success and hatchling percentage, and their survival was monitored for the next two weeks.

where R = worm reproduction rate; C = total number of cocoons produced; E = total number of earthworms used in this study.

2.7. Data Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using Minitab (Version 22.1) and XLSTAT (Version 2.0, 2025) (Addinsoft, Paris, France). Data visualization and trend interpretation were performed with SigmaPlot (version 15.0). All measurements were carried out in triplicate (n = 3), and the results were presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SE). Differences between group means were determined using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s Honestly Significant Different (HSD) test at the significance level of p < 0.05.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Effect of Different Population Densities on Physicochemical Properties of Vermicompost

The mean temperature was 23.8 ± 0.12 °C during the day and 20.1 ± 3 °C at the night during the controlled experimental period.

3.1.1. pH

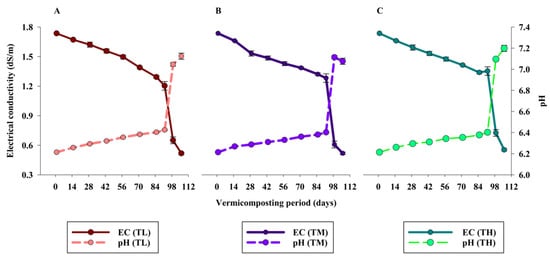

The initial pH of PPMS while introducing E. fetida was 7.34 ± 0.02, which was similar in all the experimental units. According to Figure 1, the pH of the produced vermicompost was lower than the initial pH (p < 0.036), and this trend was similar in all treatments. Vermicomposting resulted in lowering the pH of organic waste at the end of the experiment, which was favored by the moderate temperature, which in the current experiment ranged between 18 and 25 °C [15,16]. However, there was no significant difference in the pH of the produced vermicompost among the treatments (p > 0.05). The mutual action that prevailed between earthworms and microbes resulted in the production of CO2 and organic acids during vermicomposting, which ultimately caused a reduction in pH [35]. The rate of pH reduction and its fluctuation were observed at the beginning of the experiment, which was due to the initial degradation of organic matter, leading to the formation of basic hydroxides.

Figure 1.

Temporal variation in electrical conductivity and pH of pulp and paper mill sludge as affected by Eisenia fetida stocking densities ((A): TL, (B): TM, (C): TH) during the vermicomposting process (mean ± SE, n = 3; p > 0.05).

The EC of the PPMS at the beginning was 0.529 ± 0.001 dS/m; however, the value showed an increasing trend (Figure 1) in all the treatments. This might be because of the release of mineral salts, such as potassium, ammonium, phosphate, etc., and loss of organic matter during the active vermi-reaction [36]. However, the process of mineralization and formation of salts are highly influenced by the temperature, with these favored within 15–35 °C. In the current study, EC values among all the treatments—TL, TM, and TH—were non-significant (p > 0.05) throughout the vermicomposting period.

3.1.2. Organic Matter (OM) Content

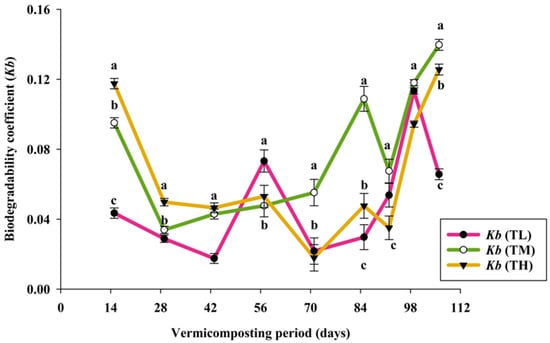

The initial organic matter content (OM) of PPMS was 75.5%, and the OM was reduced in all the treatments during the vermicomposting process. These reduction values of both harvesting days were statistically significant (p < 0.010) with the initial OM content of PPMS. However, the treatment values were non-significant between days 60 and 90 (p > 0.05). Meanwhile, OM loss was higher (12.7%) in TM compared with the other two treatments on day 90. The results indicated that E. fetida and microbial activities caused the reduction in OM favorably. Similarly, the loss of OM was inversely proportional to the increased concentration of PPMS in vermibeds. Microbial and earthworm activities enhance the oxidation process in organic wastes, and subsequent production of CO2 is lost [15,37]. Similar trends were shown in a previous study, which mentioned that microbial activity enhances the biodegradation of organic waste and releases CO2, while some organic fractions are converted into earthworm biomass, finally leading to the reduction in PPMS [38]. As shown in Figure 2, the biodegradability coefficient (Kb) is an indicator that shows the degradation intensity of organic matter presented in PPMS by microorganisms and earthworms. During the initial decomposing period, Kb values were higher due to the abundance of readily available materials. This study found that the Kb values in the first two weeks were 0.12 (TH), 0.10 (TM), and 0.04 (TL) due to the active microbial and E. fetida population. Kb values ranged between 0.02 and 0.11, 0.03 and 0.14, and 0.02 and 0.13 in TL, TM, and TH, respectively, throughout the experimental period. The second peak Kb values of 0.07 (TL), 0.06 (TM), and 0.05 (TH) were attained between 50 and 60 days while the third peak of TM (0.14) was attained in 100 days.

Figure 2.

Variation in the biodegradability coefficient (Kb) of pulp and paper mill sludge over the processing period of vermicomposting (mean ± SE, n = 3; p < 0.036). Means followed by the different letters (a, b & c) are statistically different (p < 0.05).

3.1.3. Total Nitrogen, Phosphorus, Potassium, and Carbon

The total NPK content of the vermicompost strongly relied on the quality and quantity of the substrate used for vermicomposting, as well as the free-living nitrogen-fixing bacteria [39]. As shown in Table 2, a slight decrease in total carbon (C) content was observed in the PPMS across all the treatments, while the NPK content in the vermicompost increased. The increase in NPK was higher in TM compared to TL and TH in 60 days. This study revealed that total NPK increased throughout the vermicomposting period. However, the increase between 60 and 90 days was significantly lower compared to that on day 60.

Table 2.

Changes in chemical characteristics of pulp and paper mill sludge (PPMS) during vermicomposting process (mean ± SE, n = 3). Means followed by the different letters (a, b & c) are statistically different (p < 0.05).

Additions of mucus, body fluids, enzymes, and excretory products were also reasons for the enriched N profile in vermicompost [40,41]. Enrichment of N is determined by the quality of food or substrate, which significantly influences the status of organic C and N in the earthworm cast [17]. Total N not only depended on the quality of organic waste fed to the earthworm but also may have been extended by the influence of free-living N-fixing bacteria [39]. Total N (%) in initial PPMS was 1.34 ± 0.00 and increased in all the treatments during both harvesting periods. The C:N of PPMS was (34.78 ± 1.8) slightly higher on day 1 and reduced in all the treatments. However, the changes were non-significant among all the treatments on day 90, while TM showed a result that was significant (p < 0.012) with TH and TL on day 60. Moreover, all the changes were significant with the initial C:N of PPMS (p < 0.034). As shown in Table 3, the total P content significantly (p < 0.018) increased, at about 15.9%, in TM, while the rise was 7.2 in both TL and TH. Finally, the C:P reduced to a certain level, from 67.54 ± 2.1 to 59.23 ± 2.0, 53.54 ± 2.0, and 61.61 ± 2.3 in TL, TM, and TH, respectively, at the end of 60 days. Based on the previous study conducted by earthworms produce alkaline phosphatase in their guts and excrete this through cast deposition [42,43]. The available form of P in vermicompost is due to the action of both P-solubilizing microorganisms and phosphatase present in earthworm guts [44].

Table 3.

Changes in chemical properties of pulp and paper mill sludge (PPMS) during vermicomposting (mean ± SE, n = 3). Means followed by the different letters (a, b & c) are statistically different (p < 0.05).

Additionally, the total K content was also increased in all the treatments, while 12.2% of the increase was attained in TM on day 60 (p < 0.034). Meanwhile, a 5.2% increase was achieved in both TL and TM on day 60. However, there was not any significant increase attained between 60 and 90 days. The mechanism for solubilizing insoluble K and K is achieved by the acid produced during microbial decomposition and the activities of microflora present in the guts of earthworms [45,46]. Therefore, from the current study, it can be concluded that earthworms and the combined vermicomposting process with microorganisms are the reasons for the rise in total NPK. Meanwhile, the changes in increases were influenced by the number of earthworms initially incubated and the substrate used for feeding earthworms as well.

Total Ca, Mn, and Cu also increased in the vermiconversion process of E. fetida in all the treatments in 60 days (Table 3). In addition, the total sodium content was lower in TL (781.33 mg/kg) than the initial value (850 ± 13.1 mg/kg), while TM (884 ± 12.4 mg/kg) and TH (859 ± 12.0) showed increases over the same period. Further, soluble salts increased quickly in TL (2.67 dS/m) from the value of 0.616 dS/m. These trends were similar on the 90th day with slight changes as well. In this study, decreases in C:N and C:P were faster within 60 days, and the reduction rate was slower afterwards. As a result, C:N and C:P were reduced and fell within the acceptable level of plant growth. Here, the rise in total P during vermicomposting is due to the mineralization of phosphate [47,48].

3.2. Bioassay of Vermicompost

The degree of compost maturity and the level of phytotoxicity of produced vermicompost are generally determined by the seed germination test (Table 4 and Table 5).

Table 4.

Germination response and seedling growth performance of Raphanus sativus tested in vermicompost (mean ± SE, n = 3). Means followed by the different letters (a, b, c, d and e) are statistically different (p < 0.05).

Table 5.

Summary of root bioassay parameters of Raphanus sativus (mean ± SE, n = 3). Means followed by the different letters (a, b, c and d) are statistically different (p < 0.05).

3.2.1. Final Germination Percentage (FGP)

The final germination percentage (FGP) and GI of R. sativus ranged from 90% to 100% and from 162.7 to 189.7, respectively. At the end of 60 days, the FGP of the treatments TL, TM, and TH, PPMS initial substrate, and control (DI water) showed no significance difference (p > 0.05) among them. As shown in Table 4, the highest FGP was recorded as 100% in TM, followed by 98.3% in TL and 98.1% in TH, on the 60th day.

3.2.2. Germination Index (GI)

The calculation of GI always emphasizes the combined effect of both the percentage of germination and its speed. The highest GI value indicates the highest germination percentage and rate of germination [49]. In this study, the highest GI was observed in TM (189.7 ± 0.67), followed by TL (185.3 ± 2.73) and TH (183.7 ± 0.00). The GIs of treatments TL, TM, and TH were higher than the GI value obtained from the control (178.0 ± 2.01) and initial PPMS (172.3 ± 2.91), where the values were not significant among them (treatment mean).

3.2.3. Coefficient of Velocity of Germination (CVG)

Germination rapidity is usually determined by the coefficient of velocity of germination (CVG). The CVG is calculated using the inverse relationship between the numbers of seeds germinated and the time required for germination [33,34]. Here, the CVG increases with a higher number of germinated seeds and shorter germination time. -The maximum CVG is 100, which occurs when all seeds germinate on the first day [33,34].

The current study showed the maximum CVG of 66.0 ± 1.48 in TM, followed by 65.3 ± 1.50 in TL and 65.2 ± 0.00 in TH. These values were significantly higher (p < 0.007) than the CVG of the initial PPMS (56.7 ± 2.02) and control (61.3 ± 1.03), whereas treatment means were not significant.

3.2.4. First and Last Days of Germination (FDG and LDG)

Lower first day of germination (FDG) values indicate a faster initiation of seed germination, while the last day of germination (LDG) depicts a faster ending of germination [33,34]. Seeds from all the treatments started to germinate on day 1 and completed their germination on day 3. Therefore, the FDG was one and LDG was three in the current study.

3.2.5. Germination Rate Index (GRI)

The highest germination rate index (GRI) was 15.5% per day in TM, followed by TL (15.4% per day) and TH (15.1% per day). These values were comparatively higher than the initial PPMS responses and control as well, and they had significant differences with the initial PPMS and control (p < 0.001).

3.2.6. Mean Germination Time

The mean germination time (MGT) demonstrates the required time for germination and shows the mean expected time for the seeds to germinate [50]. In the vermicomposting maturity test, a shorter time (1.5 days) was required by the seeds used in TL, TM, and TH vermicompost. However, the required time was slightly higher in PPMS (1.8 days) and the control (1.6 days). These results were highly significant and had significant differences among them (p < 0.008). The highest treatment mean difference was obtained in initial PPMS, and it had a significant mean difference with all the other treatments—TL, TM, TH, and control.

3.2.7. Germination Energy (GE)

The tested viabilities for determining the germination energy (GE—%) were 98.3 ± 0.96, 100 ± 0.91, 98.1 ± 0.93, 93.3 ± 0.91, and 95% for TL, TM, TH, PPMS, and the control, respectively. Plants grow well from seeds with a high GE and will have the ability to restrict competition as well [51].

3.2.8. Time Spread of Germination (TSG)

In the current study, seeds of R. sativus started germinating on day 1 and ended up germinating on day 3. Therefore, the first and last days of germination of R. sativus seeds were 1 and 3 days, respectively. Further, the higher TSG value depicts greater differences in germination speed. However, all the treatments showed the same day (2) of TSG in the tested lot.

3.3. Data on Growth Parameters of Seedling

Recorded values of average RL and SL were used to calculate the vigor index of the emerging seedlings [49,50].

3.3.1. Average Root Length (RL)

In the current study, the average RL did not show any significant differences (p > 0.05) among the treatments, and the highest RL was recorded in the control (DI), followed by TM, TL, and TH. Meanwhile, the lowest RL was obtained in the initial PPMS.

3.3.2. Average Shoot Length (SL)

On the other hand, the average SL had a significant difference (p < 0.023) among the treatments. The highest record was obtained in TM, followed by TL, TH, and the control. The lowest SL was observed in PPMS and had a significant difference among all the treatments (p < 0.005).

3.3.3. Seedling Vigor Index (SVI)

In order to ensure the ability of seeds to produce normal seedlings, the seedling vigor index was tested. A significant difference (p < 0.002) was observed among the treatments in SVI. In addition, the highest SVI was recorded in TM, followed by TL, TH, and the control. However, there was a huge difference in SVI observed in the initial PPMS. The treatment mean was analyzed at the 95% confidence level, where TL, TM, and TH did not have any significant differences among them; however, they differed a lot from the initial PPMS and control.

3.4. Potential Use of Eisenia fetida in Degradation and Release of Metals During Vermicomposting

The concentrations of Al, Cd, Fe, Pb, Sn, and Tl increased compared to the initial PPMS (Table 6). Al and Cd showed a significant difference (p < 0.018) with PPMS, whereas As, Fe, Pb, and Tl did not show a significant difference (p > 0.05). The accumulation of metals in tissue reflects the detritivore lifestyle, where highly permeable body walls can retain high concentrations of certain metals in an insoluble state. This process is altered during the vermicomposting process. Additionally, the organic matter content and pH significantly contribute to the accumulation of metals, particularly Pb and Cd, in earthworm tissues [50,52].

Table 6.

Changes in elemental concentration of pulp and paper mill sludge (PPMS) between day 1 and day 60 of vermicomposting (mean ± SE, n = 3). Means followed by the different letters (a, b & c) are statistically different (p < 0.05).

Meanwhile, the concentrations of minerals such as B, Co, Cu, Mn, Ni, Sr, Ba, Cr, Mo, Ag, U, V, and Zn decreased during the vermicomposting process, with the levels on day 60 being lower than the initial values. Micronutrients including B, Co, Cu, Mn, Ni, Ba, Cr, Mo, Ag, V, and Sr showed significant reductions (p < 0.001) relative to the initial PPMS, whereas U and Zn did not exhibit a statistically significant decrease in the final vermicompost. In contrast, a progressive increase in Cu, Pb, Ni, Zn, and Cd was observed in vermicompost, indicating that the total concentrations of certain metals in the substrate can change during the composting and vermicomposting processes [53]. The authors noted that nutrient enrichment and gut-associated processes variously increase the availability of elements like Cu, Co, Cr, Mn, Ca, Fe, Mg, and P for plants, while causing slight increases in Cd, Pb, Zn, and K [54]. The authors stated that vermicomposting involves two phases: one within the gut and the other as an external event within the cast, mediated by the microflora, leading to qualitative and quantitative differences in metal mobility. Vermicomposting has been reported to significantly reduce the extractable fraction of Cu and Zn [54,55]. Similarly, the current study observed a reduction in Cu (p < 0.05) and Zn (p > 0.05).

Heavy metals such as Pb, Cu, Zn, and Cd, primarily from agricultural and mining activities, are recognized as significant contributors to environmental contamination and human health risks [56,57]. In agriculture, these metals come from sources such as pesticides, manures, wastewater, and fertilizers [9]. Although some heavy metals are essential for plants and human organs, they become toxic when they exceed the CCME prescribed levels. Table 4 shows a non-significant increase in Pb (18.7 ± 0.31) and Cd (2.8 ± 0.12), alongside a reduction in both Cu (54.6 ± 1.16) and Zn (422 ± 9.78). However, the final vermicompost values were much lower than the CCME standards for AA- and A-grade composts, which are 150, 3, 400, and 700 mg/kg, respectively, and for B-grade compost, which are 500, 20, 757, and 1850 mg/kg.

3.5. Impact of Different Stocking Densities of Eisenia fetida on Vermicomposting and Production of Vermicompost

Table 7 shows the data on the total quantity of vermicompost produced, composted and non-composted portions (left out), and earthworm population density of all the age classes (juvenile, hatchlings, and cocoon) in 60 and 90 days of harvesting.

Table 7.

Rate of decomposition of pulp and paper mill sludge (PPMS) during vermicomposting (mean ± SD, n = 3). Means followed by the different letters (a, b & c) are statistically different (p < 0.05).

Among those three treatments, TM showed the maximum vermicompost yield in 60 days. Here, the population density TL and TM contributed a lot to the decomposition process and recorded a faster completion of the substrate with the average number of E. fetida each time. The decomposition rates per worm of PPMS were higher in TL > TM > TH on the 60th day. However, the rate of decomposition was much lower afterwards. Meanwhile, the non-composted percentage was higher in TH, which was an indication of the slower decomposition rate than for the other treatments. According to the results, the addition of E. fetida—more than 20 worms per worm bed—did not increase the rate of vermicomposting, and it showed a need for an increased time to complete vermicomposting. Some earthworms were found outside of the worm beds and started dying due to the high carbon level and competition for their food, and ultimately, delayed the vermicomposting process in TH.

The smallest number of all the age classes was observed in TL and the highest in TH in 60 days, and it was reversed on the 90th day (Table 8 and Table 9). As a result, around 68.79% of the total substrate PPMS was vermicomposted by E. fetida in TM, while other treatments achieved average values of 66.13% in TL and 65.19% in TH at 60 days. On the other hand, at 90 days, the decomposition rate was similar in TL (71.54 ± 2.42) and TM (71.03 ± 1.62) more so than TH (66.50 ± 4.02). Between the 60- and 90-day periods, TM showed an increase of around 3.25%, while TL and TH showed increases of 9.74% and 2.01%, respectively, over the 30-day period. The optimal earthworm density for vermicomposting is usually determined by the smallest amount of non-composted substrate [36,58], the highest quantity of vermicompost produced in the shortest time [59,60], and the largest number of available juveniles [61,62] and cocoons [63,64]. In this study, a significant difference (p < 0.032) was found in the vermicompost percentages at the two different harvesting periods (60 and 90 days). However, within each harvest period, non-significant differences were found among the three treatments (p > 0.05). Despite this, TM produced the highest quantity of vermicompost (68.79%) compared to TL and TH.

Table 8.

Influence of Eisenia fetida population density on vermicompost production and earthworm reproduction during the vermicomposting process (mean ± SD, n = 3). Means followed by the different letters (a, b & c) are statistically different (p < 0.05).

Table 9.

Growth and reproductive performance of Eisenia fetida at 60 and 90 days of vermicomposting period (mean ± SD, n = 3). Means followed by the different letters (a, b & c) are statistically different (p < 0.05).

As per the statistical analysis, the mean values for the largest number of available preclitellate, juvenile, and hatchling worms were higher in TH on both harvesting days. The average cocoon production was also higher in TH, with 0.010 cocoons per worm per day, due to the highest initial stocking density. Total counts for the adults and juveniles for the treatments are shown in Table 6.

3.6. Growth Performances of Eisenia fetida

3.6.1. Growth Rate of Eisenia fetida

An effective vermicomposting process is achieved through the growth and reproduction of the earthworms (E. fetida) used in the vermistabilization of PPMS. The growth parameters of worms in the worm bed are strong indicators of a successful process [65,66,67].

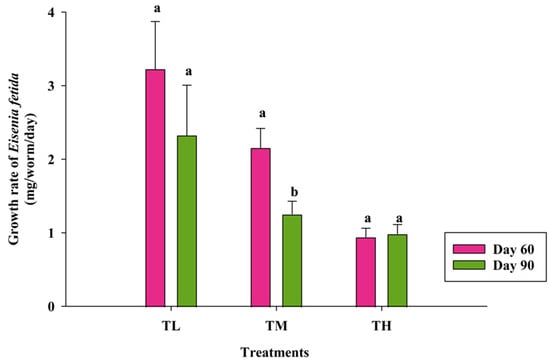

According to Figure 3, the growth rate of E. fetida over 60 days was 3.23 mg/worm/day in TL, followed by 2.16 mg/worm/day in TM, and 0.94 mg/worm/day in TH. Further, the growth rate decreased over time, as evidenced by the 90-day results: 2.33 mg/worm/day in TL, 1.25 mg/worm/day in TM, and 0.99 mg/worm/day in TH. These values were significantly different (p < 0.002) among three treatments. Additionally, the mean growth rate for TL was significantly different (p < 0.005) from both TM and TH.

Figure 3.

Growth rate of Eisenia fetida during vermicomposting at the 60th (p < 0.021) and 90th (p < 0.045) days of harvesting period (mean ± SE, n = 3) (TL—lower, TM—medium, and TH—high initial stocking densities of Eisenia fetida). Means followed by the different letters (a & b) are statistically different (p < 0.05).

3.6.2. Biomass Gain of Eisenia fetida

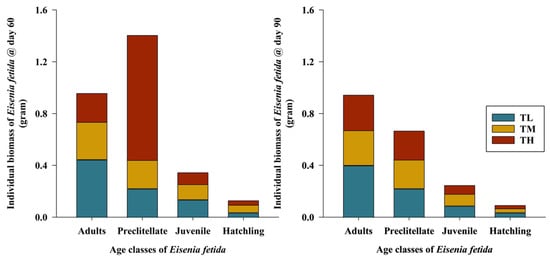

The individual biomasses of all age classes (adults/clitellated, preclitellate, juvenile, and hatchlings) showed significant differences among them (p < 0.036). In this study, the maximum individual adult biomass was found in TL (0.44 g), followed by TM (0.28 g) and TH (0.22 g), in 60 days (Figure 4). However, the individual biomass of adults decreased slightly in TM (0.27 g) and TL (0.41 g) at 90 days, while it increased in TH over the same period. Individual biomass was higher when the number of earthworms in a unit volume was lower. As the population density increased, the biomass of the earthworms decreased. Harvesting days also influenced the reduction in biomass over time. The most effective period for decomposition and achieving the maximum biomass was within the first 60 days, after which it declined.

Figure 4.

Changes in the individual biomass of Eisenia fetida across different age classes at 60 (p< 0.001) and 90 (p > 0.05) days of the harvesting period (mean ± SE, n = 3) (TL—lower, TM—medium, and TH—high initial stocking densities of Eisenia fetida).

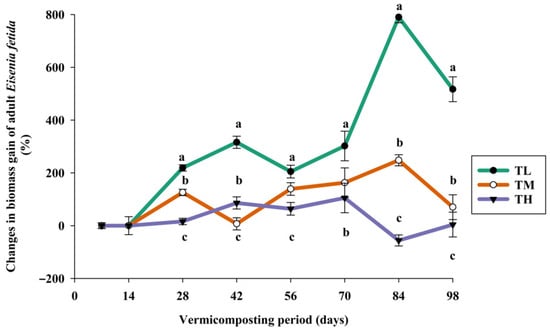

3.6.3. Growth Pattern of Adult Eisenia fetida in Gaining Biomass

Table 10 illustrates the weight of E. fetida over a 14-day experimental period. The total biomass of the earthworm increased in each treatment by the 60-day mark. However, biomass of adults from TM and TH treatments decreased after 60 days, while an increase was observed in the TL treatment due to its initially lower population density compared to the other two treatments. Statistical analysis indicated no significant differences among the three treatments or the different harvesting days.

Table 10.

Growth pattern of adult Eisenia fetida based on biomass gain during the vermicomposting process (mean ± SE, n = 3). Means followed by the different letters (a, b & c) are statistically different (p < 0.05).

The maximum weight gain in each treatment occurred during two different periods. In the TL treatment, the first peak in biomass was observed in the eighth week, and the second peak was in the 13th week. For the TM treatment, the first and the second peaks were in the 6th and the 13th weeks, respectively. However, the TH treatment showed only one peak, in the 12th week. Additionally, individual weight loss was evident by the end of this study. This weight loss might be attributed to the depletion of food resources due to the increasing number of juveniles and the energy demands associated with sexual maturity, including copulation, cocoon formation, and egg laying [27,67]. The two peak values observed correspond to the two reproductive cycles of earthworms.

This study found that adult E. fetida in the TL treatment achieved the maximum weight gain in a shorter period compared to those in the TM and TH treatments (Figure 5). Specifically, the biomass gain in TL was 316% by the eighth week (56 days), whereas it was 126% in the sixth week for TM and 105% in the 12th week for TH. Additionally, biomass in TL doubled by the 13th week, indicating that biomass gain increases with lower stocking densities, while the number of worms increases with higher stocking densities. In addition, the growth rate of earthworms is a reliable comparative index for evaluating different treatments, especially when using different organic wastes [27]. However, the type and quality of the substrate used in the vermiculture process also significantly influence the growth rate (mg/worm/day) of earthworms [68,69].

Figure 5.

Temporal changes in the total biomass of Eisenia fetida over 14 weeks of vermicomposting period (mean ± SE, n = 3; p < 0.001) (TL—lower, TM—medium, and TH—high initial stocking densities of Eisenia fetida). Means followed by the different letters (a, b, c) are statistically different (p < 0.05).

3.7. Reproductive Performance of Eisenia fetida

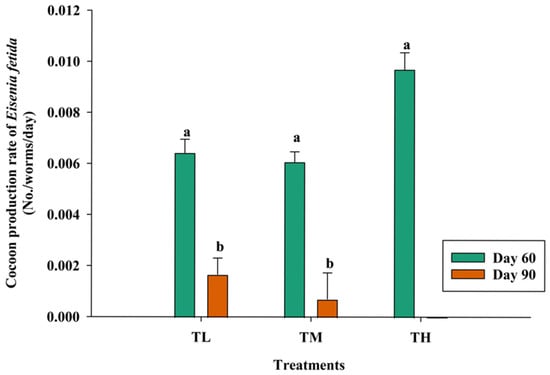

3.7.1. Production of Cocoon

As the experiment began with the adult E. fetida, cocoon production began in the second week in all three treatments, while the number of cocoons was observed differently. TL produced the maximum cocoons in week 6 (42 days), and the number was lower afterwards. Moreover, 134 cocoons were collected from TM, while 180 cocoons were collected from TH in week 4 and showed a reduction afterwards. The feeding material and nutritional value of the substrate greatly influence the number of cocoons produced in a cycle [65]. High levels of total potassium and calcium are essential for the best reproductive performance of E. fetida. In the current study, the highest cocoon production levels were 0.39 ± 0.31, 0.36 ± 0.24, and 0.58 ± 0.39 cocoons/worm, which were higher in TH and lower in TM during the harvesting period of 60 days. However, this cocoon production ceased in TH on 90th day and started again in the 14th week. Cocoons were not observed in TL and TM in the second peak and showed a drastic reduction during the study period of 14 weeks. However, the maximum cocoon production rate was observed in TL and TM, with the mean values of 0.027, 0.061, and 0.065 cocoons/worm/day with respect to the fourth, fourth, and third weeks, as well. Meanwhile, cocoon production rates during the harvesting period of 60 days were 0.0097 ± 0.007 (TH), 0.0064 ± 0.005 (TL), and 0.0061 ± 0.004 (TM) (Figure 6). A significant (p < 0.046) cocoon rate was recorded in 60 days in TH, where the initial stocking density of adults was higher for their maximum successful mating.

Figure 6.

Cocoon production rate of Eisenia fetida at the 60th (p < 0.004) and 90th (p < 0.001) days of the harvesting period (mean ± SE, n = 3) (TL—lower, TM—medium, and TH—high initial stocking densities of Eisenia fetida). Means followed by the different letters (a & b) are statistically different (p < 0.05).

Moreover, in all the treatments, we maintained a similar initial volume of PPMS, and we maintained all the environmental parameters. The difference between the three treatments was in the stocking density. Furthermore, PPMS had a higher and sufficient amount of initial non-assimilated carbohydrates, which was one of the reasons for the initial cocoon production [70]. A substrate with easily metabolizable organic matter facilitates growth and reproduction in earthworms [71]. However, few adults in all three treatments reached the adult stage (clitellum) in 43 days. Similar results were found in previous research, whereby it takes 3–4 weeks to develop the clitellum in earthworms, which can be varied based on different substrates [65,72]. Moreover, the total number recovered from all the three treatments in 60 days showed a huge difference compared to the next harvesting day (90th day).

The total number of each age class of E. fetida was higher in TH, which consisted of more hatchlings (56.3%), followed by juveniles (50.5%), adults (10.7%), and preclitellates (2.59%). The juvenile percentage was higher in TM (34.1%) compared to TL (26.6%) and TH (30.4%). The hatchling percentage was higher in TH (56.3%), followed by TM (38.5%) and TL (37.1%). However, the total juvenile and hatchling percentage is considered the best productive age class for the next round of cycling and decomposition. In 60 days, the combination of juveniles and hatchlings was higher in TH (86.7%), while it was comparable (p > 0.05) in TM (72.6%) and TL (63.7%). Meanwhile, this age class’s populations exhibited significant differences among them (p < 0.002).

In contrast, the population density was recorded in 90 days of the vermicomposting process. The combined juvenile and hatchling percentage was higher in TH, with an average of 91.3%, compared to TM (90.2%) and TL (78.6%). Adults and preclitellates peaked in TL, with averages of 17.8% and 3.6%, respectively. However, the adult and preclitellate population reduced by half in all three treatments between 60 and 90 days, which increased the population density of hatchlings and juveniles. The percentage of hatchlings reached 65.3% in TH, 59.1% in TM, and 43.3% in TL. This is one of the reasons for the slower decomposition rate of vermicomposting between 60 and 90 days.

3.7.2. Hatching Success of Cocoons

The hatching success of E. fetida did not differ significantly among treatments (p > 0.05) (Table 11).

Table 11.

Hatching performance of cocoons of Eisenia fetida in different treatments (mean ± SE, n = 3) Means followed by the same letter (a and b) is statistically non-significant (p > 0.05).

The maximum number of hatchlings was observed in TH (41.7 ± 2.08), while the minimum hatchlings were recorded in TM, with the average of 38.3 ± 1.53 (Table 11). However, there was no significant difference among the three treatments. The hatching percentage was also higher in both TL and TH, with the mean value of 86.7% ± 5.8. The average incubation period of cocoons was 12–14 days in all three treatments while using PPMS as the substrate for the worms. It took an average of 48–53 (TH) days to complete one cycle in PPMS, while the conditions were optimum (temperature—22.9 °C and moisture content 68.9–73.4%). There were no differences observed between TH and TM as the reproductive cycle of TM was accomplished in 51–54 days. Moreover, the number of days taken for a cycle in TL was nearly 53–58 days, where the average densities were comparatively lower than for the other two stocking densities. However, studies are limited on the relationship between the substrate quality and the success rate of cocoons hatched. In addition, the nitrogen content of the substrate has a strong influence on the success rate of earthworms [73,74].

4. Conclusions

This research study has demonstrated that the initial stocking density of Eisenia fetida in the worm bed significantly influenced the vermicomposting process of pulp and paper mill sludge (PPMS). For the tested PPMS volumes, an optimum population of either low (TL) or medium (TM) resulted in a faster vermicomposting process. Given that the PPMS was used without organic amendments, a stocking density of TM enabled more efficient vermicomposting and reduced the overall processing duration. When introducing 1.25 ± 0.11 kg of E. fetida per Mg of PPMS under proper management, minimums of 687.90 ± 23.4 kg and 710.26 ± 19.4 kg of PPMS could be processed by the 60th and 90th days, respectively. Additionally, vermicomposting led to an increase in total NPK contents relative to the initial PPMS, indicating improved nutrient enrichment during stabilization. The results further indicate that the nutritional characteristics of PPMS influenced the growth and reproduction of E. fetida under the experimental conditions. An optimal stocking density of 0.46 E. fetida/L was identified for maximizing E. fetida biomass production. Based on biomass calculations, the introduction of 0.75 ± 0.05 kg E. fetida per Mg of PPMS would yield 3.09 ± 0.05 and 6.61 ± 0.04 kg of E. fetida (wet weight) in 60 and 90 days, respectively, which could be repurposed as feed for poultry and fish. Therefore, using the optimum stocking density of E. fetida not only accelerates the vermicomposting process but also presents a cost-effective alternative to the traditional burning of PPMS.

5. Limitation of This Study and Future Directions

This study was conducted under controlled experimental conditions as a pilot study using a source of pulp and paper mill sludge (PPMS), and the results may therefore either not fully represent the variability observed under field-scale operations or across different waste amendments with PPMS. The experiment was limited to specific stocking densities and processing durations (up to 90 days), while environmental conditions and long-term dynamics were not evaluated during the current pilot study. In addition, while changes in the nutrient content and biomass of Eisenia fetida were quantified, and the economic feasibility was assessed at the end of the entire project, future studies should validate these findings at larger scales and across diverse operational and environmental settings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.S., M.K. and L.G.; methodology, D.S., M.K. and L.G.; software, D.S.; validation, D.S., M.K., L.G. and C.F.M.; formal analysis, D.S.; investigation, D.S.; data curation, D.S., M.K. and L.G.; writing—original draft preparation, D.S.; writing—review and editing, D.S., M.K., L.G. and C.F.M.; visualization, D.S., M.K. and L.G.; supervision, M.K. and L.G.; project administration, M.K. and L.G.; funding acquisition, M.K. and L.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by MITACS (No: IT35549), Corner Brook Pulp and Paper Limited (CBPPL), and Grenfell Campus, Memorial University of Newfoundland, Canada.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data generated or analyzed during this study are provided in full within the published article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge MITACS and Corner Brook Pulp and Paper Limited (CBPPL) for the funding and the fellowship from the Grenfell Campus, Memorial University, Newfoundland, Canada.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations were used in this manuscript.

| PPMS | Pulp and paper mill sludge |

| Mg | Megagram (ton) |

| CBPPL | Corner Brook Pulp and Paper Mill Limited |

| NL | Newfoundland and Labrador |

| NPK | Nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium |

| OM | Organic matter |

| EC | Electrical conductivity |

| D | Decomposition percentage |

| Kb | Biodegradability coefficient |

| RSG | Relative seed germination |

| RRG | Relative radical growth |

| GI | Germination index |

| FGP | Final germination percentage |

| SVI | Seedling vigor index |

| CVG | Coefficient of velocity of germination |

| MGT | Mean germination time |

| GRI | Germination rate index |

| GE | Germination energy |

| TSG | Time spread of germination |

| G | Growth rate |

| BMG | Biomass gain per unit waste |

| R | Worm reproduction rate |

| C | Carbon |

| CCME | Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| TL | Treatment—Low stocking density |

| TM | Treatment—Medium stocking density |

| TH | Treatment—High stocking density |

References

- Statista Research Department. Global Market Size of Paper and Pulp 2021–2029. Statista. 2023. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1073451/global-market-value-pulp-and-paper/ (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Turner, T.; Wheeler, R.; Oliver, I.W. Evaluating land application of pulp and paper mill sludge: A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 317, 115439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haile, A.; Gelebo, G.G.; Tesfaye, T. Pulp and paper mill wastes: Utilizations and prospects for high value-added biomaterials. Bio-Resour. Bioprocess 2021, 8, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Environment Canada. Wastepaper Recycling in Canada. 1991. Available online: https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2023/eccc/en40/En40-204-2-1991-eng.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Government of Canada. Modernization of the Pulp and Paper Effluent Regulations—Updated Detailed Proposal for Consultation—January 2024. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/managing-pollution/sources-industry/pulp-paper-effluent/modernization-proposal.html (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Norrie, J.; Fierro, A. Paper Sludge as Soil Conditioners. In Handbook of Soil Conditioners; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020; pp. 97–118. [Google Scholar]

- Nordahl, S.L.; Preble, C.V.; Kirchstetter, T.W.; Scown, C.D. Greenhouse Gas and Air Pollutant Emissions from Composting. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 2235–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santana, N.A.; Jacques, R.J.S.; Antoniolli, Z.I.; Martínez-Cordeiro, H.; Domínguez, J. Changes in the chemical and biological characteristics of grape marc vermicompost during a two-year production period. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2020, 154, 103587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.L.; Wu, T.Y. Characterization of matured vermicompost derived from valorization of palm oil mill byproduct. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 1761–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanati, C.; Willer, D.; Schubert, J.; Aldridge, D.C. Sustainable Intensification of Aquaculture through Nutrient Recycling and Circular Economies: More Fish, Less Waste, Blue Growth. Rev. Fish. Sci. Aquac. 2022, 30, 143–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatua, C.; Sengupta, S.; Balla, V.K.; Kundu, B.; Chakraborti, A.; Tripathi, S. Dynamics of organic matter decomposition during vermicomposting of banana stem waste using Eisenia fetida. Waste Manag. 2018, 79, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, S.; De Castro, F.; Marini, P.; Aprile, A.; Benedetti, M.; Fanizzi, F.P. Vermibiochar: A Novel Approach for Reducing the Environmental Impact of Heavy Metals Contamination in Agricultural Land. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usta, A.N.; Guven, H. Vermicomposting organic waste with Eisenia fetida using a continuous f low-through reactor: Investigating five distinct waste mixtures. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 114384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, T. Vermicomposting: An effective option for recycling organic wastes. In Organic Agriculture; Intech Open: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhambore, N. Municipal Solid Waste Management: Challenges, Opportunity and Best Practices in Developing Countries. In A Vision for Environmental Sustainability: Overcoming Waste Management Challenges in Developing Countries; Mandpe, A., Shah, M.P., Paliya, S., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuvaraj, A.; Thangaraj, R.; Ravindran, B.; Chang, S.W.; Karmegam, N. Centrality of cattle solid wastes in vermicomposting technology—A cleaner resource recovery and biowaste recycling option for agricultural and environmental sustainability. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 268, 115688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangappan, V.; Suji, S. Creating and Describing Briquettes from Cattle Manure by Utilizing Sawdust as a Binding Agent, Contrasted with the use of Cow Dung. In Case Studies on Holistic Medical Interventions; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024; pp. 941–947. [Google Scholar]

- Sannigrahi, A.K. Management of hazardous paper mill wastes for sustainable agriculture. In Handbook of Environmental Materials Management; Hussain, C.M., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, J.; Pegu, R.; Mondal, H.; Roy, R.; Sundar, B.S. Earthworm stocking density regulates microbial community structure and fatty acid profiles during vermicomposting of lignocellulosic waste: Unraveling the microbe-metal and mineralization-humification interactions. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 367, 128305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahariah, B.; Goswami, L.; Kim, K.H.; Bhattacharyya, P.; Bhattacharya, S.S. Metal remediation and biodegradation potential of earthworm species on municipal solid waste: A parallel analysis between Metaphire posthuma and Eisenia fetida. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 180, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajam, Y.A.; Kumar, R.; Kumar, A. Environmental waste management strategies and vermi transformation for sustainable development. Environ. Chall. 2023, 13, 100747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unuofin, F.O.; Mnkeni, P.N. Optimization of Eisenia fetida stocking density for the bioconversion of rock phosphate enriched cow dung–wastepaper mixtures. Waste Manag. 2014, 34, 2000–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katagi, T.; Ose, K. Toxicity, bioaccumulation and metabolism of pesticides in the earthworm. J. Pestic. Sci. 2015, 40, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sannigrahi, A.K. Efficiency of Perionyx excavatus in vermicomposting of Thatched grass in comparison to Eisenia foetida in Assam. J. Indian Soc. Soil Sci. 2015, 13, 23–27. [Google Scholar]

- Enebe, M.; Erasmus, M. Vermicomposting technology -A perspective on vermicompost production technologies, limitations and prospects. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 345, 118585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Gao, X.; Yin, J.; Wang, G.; Li, J.; Li, G.; Cui, Z.; Yuan, J. Applicability and limitation of compost maturity evaluation indicators: A review. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 489, 151386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadia, M.; Hossain, M.; Islam, M.; Akter, T.; Shaha, D. Growth and reproduction performances of earthworm (Perionyx excavatus) fed with different organic waste materials. J. Adv. Vet. Anim. Res. 2020, 7, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badhwar, V.K.; Sukhwinderpal, S.; Balihar, S. Biotransformation of paper mill sludge and tea waste with cow dung using vermicomposting. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 318, 124097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harwood, M.; Thompson, C.; Burton, S. Compost Moisture. 2009. Available online: https://peaceforage.bc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/FF_48_Compost_Moisture.pdf (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Rodrigues, C.I.D.; Brito, L.M.; Nunes, L.J.R. Soil Carbon Sequestration in the Context of Climate Change Mitigation: A Review. Soil Syst. 2023, 7, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, T.E.; Febles, G.; Alonso, J. A scientific contribution to legume studies during the fifty years of the Institute of Animal Science. Cuba. J. Agric. Sci. 2016, 49, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Wang, W.; Lu, H.; Shu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Q. New perspectives on physiological, biochemical and bioactive components during germination of edible seeds: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 123, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.H.; Sobze, J.M.; Pham, T.H.; Nadeem, M.; Liu, C.; Galagedara, L.; Cheema, M.; Thomas, R. Carbon nanoparticles functionalized with carboxylic acid improved the germination and seedling vigor in upland boreal forest species. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guarrasi, V.; Leto, L.; Vecchio, L.D.; Guaitini, C.; Cirlini, M.; Chiancone, B. Sumac (Rhus coriaria L.) sprouts: From in vitro seed germination to phenolic content and antioxidant activity for biotechnological application. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2024, 157, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraru, P.I.; Rusu, T.; Mintas, O.S. Trial Protocol for Evaluating Platforms for Growing Microgreens in Hydroponic Conditions. Foods 2022, 11, 1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devjani, M.; Sahoo, K.; Sannigrahi, A. Impact of Eisenia fetida populations on bioconversion of paper mill solid wastes. Int. J. Recycl. Org. Waste Agric. 2019, 8, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viji, J.; Neelanarayanan, P. Efficacy of Lignocellulolytic Fungi on the Biodegradation of Paddy Straw. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2015, 9, 225–232. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, V.; Ismail, S.A.; Singh, P.; Singh, R.P. Urban solid waste management in the developing world with emphasis on India: Challenges and opportunities. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 2015, 14, 317–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, A.; Blouin, M.; Lubbers, I.; Capowiez, Y.; Sanchez-Hernandez, J.C.; Calogiuri, T.; van Groenigen, J.W. Chapter One—The role of earthworms in agronomy: Consensus, novel insights and remaining challenges. Adv. Agron. 2023, 181, 1–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wang, J.; Pu, S.; Blagodatskaya, E.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Razavi, B.S. Impact of manure on soil biochemical properties: A global synthesis. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 745, 141003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaqoob, H.; Teoh, Y.H.; Ud Din, Z.; Sabah, N.U.; Jamil, M.A.; Mujtaba, M.A.; Abid, A. The potential of sustainable biogas production from biomass waste for power generation in Pakistan. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 307, 127250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Li, H.; Song, J.; Chen, W.; Shi, L. Biochar/vermicompost promotes Hybrid Pennisetum plant growth and soil enzyme activity in saline soils. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2022, 183, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Verma, P. Pulp-paper industry sludge waste biorefinery for sustainable energy and value-added products development: A systematic valorization towards waste management. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 352, 120052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lirikum, K.L.N.; Thyug, L.; Lobeno, M. Vermicomposting: An eco-friendly approach for waste management and nutrient enhancement. Trop. Ecol. 2022, 63, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Goswami, A.J.; Ghosh, G.K.; Pramanik, P. Quantifying the relative role of phytase and phosphatase enzymes in phosphorus mineralization during vermicomposting of fibrous tea factory waste. Ecol. Eng. 2018, 116, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Cai, L.; Li, S.; Chang, S.X.; Sun, X.; An, Z. Bamboo biochar amendment improves the growth and reproduction of Eisenia fetida and the quality of green waste vermicompost. J. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2018, 156, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, X.; Hou, X.; Duan, W.; Yin, B.; Ren, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Gu, L.; Zhen, W. Screening and evaluation of drought resistance traits of winter wheat in the North China Plain. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1194759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regnier, L.L.P.; Salatino, M.L.F. Assessment of different seedling production techniques of Euterpe edulis. Adv. J. Grad. Res. 2020, 8, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Abo-Elyousr, K.A.M.; Mousa, M.A.A.; Saad, M.M. A study on the synergetic effect of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens and dipotassium phosphate on Alternaria solani causing early blight disease of tomato. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2022, 162, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuvaraj, A.; Karmegam, N.; Ravindran, B.; Chang, S.W.; Awasthi, M.K.; Kannan, S.; Thangaraj, R. Recycling of leather industrial sludge through vermitechnology for a cleaner environment—A review. Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 155, 112791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Fan, S.; Xiang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, J.; Sun, Q. Non-destructive analysis of germination percentage, germination energy and simple vigour index on wheat seeds during storage by Vis/NIR and SWIR hyperspectral imaging. Spectrochim. Acta. Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2020, 239, 118488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Groenigen, J.W.; Van Groenigen, K.J.; Koopmans, G.F.; Stokkermans, L.; Vos, H.M.J.; Lubbers, I.M. How fertile are earthworm casts? A meta-analysis. Geoderma 2019, 338, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šrut, M.; Menke, S.; Höckner, M.; Sommer, S. Earthworms and cadmium—Heavy metal resistant gut bacteria as indicators for heavy metal pollution in soils? Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 171, 843–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, M.K.; Pandey, A.K.; Bundela, P.S.; Wong, J.W.; Li, R.; Zhang, Z. Co-composting of gelatin industry sludge combined with organic fraction of municipal solid waste and poultry waste employing zeolite mixed with enriched nitrifying bacterial consortium. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 213, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.; Jiang, L.Q.; Zhang, W.J. A review on heavy metal contamination in the soil worldwide: Situation, impact and remediation techniques. Environ. Skept. Crit. 2014, 3, 24–38. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, F.; Ding, Y.; Gao, J.; Yan, H.; Shao, W. Heavy metal pollution and assessment in the tidal flat sediments of Haizhou Bay, China. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2013, 74, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmegam, N.; Vijayan, P.; Prakash, M.; Paul, J.A.J. Vermicomposting of paper industry sludge with cow dung and green manure plants using Eisenia fetida: A viable option for cleaner and enriched vermicompost production. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 228, 718–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monroy, F.; Aira, M.; Dominguez, J.; Velando, A. Seasonal population dynamics of Eisenia fetida (Savigny, 1826) (Oligochaeta, Lumbricidae) in the field. Comptes Rendus Biol. 2006, 329, 912–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soobhany, N. Insight into the recovery of nutrients from organic solid waste through biochemical conversion processes for fertilizer production: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 241, 118413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqas, M.; Hashim, S.; Humphries, U.W.; Ahmad, S.; Noor, R.; Shoaib, M.; Naseem, A.; Hlaing, P.T.; Lin, H.A. Composting Processes for Agricultural Waste Management: A Comprehensive Review. Processes 2023, 11, 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, M. Chemical fertilizer reduction with organic fertilizer effectively improve soil fertility and microbial community from newly cultivated land in the Loess Plateau of China. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2021, 165, 103966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köninger, J.; Lugato, E.; Panagos, P.; Kochupillai, M.; Orgiazzi, A.; Briones, M.J.I. Manure management and soil biodiversity: Towards more sustainable food systems in the EU. Agric. Syst. 2021, 194, 103251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Yin, J.; Wang, W.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Z. Transformation of phosphorus during drying and roasting of sewage sludge. Waste Manag. 2014, 34, 1211–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, H.D. Vermicomposting of spent mushroom compost using perionyxexkavatus and artificial nutrient compound. Int. J. Agric. Resour. 2016, 2, 101–109. [Google Scholar]

- Awiszus, S.; Meissner, K.; Reyer, S.; Müller, J. Utilization of digestate in a convective hot air dryer with integrated nitrogen recovery. Landtechnik 2018, 73, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teferedegn, G.D.; Ayele, C. Life cycle patterns of epigeic earthworm species (Eisenia fetida, Eisenia andrei, and Dendrobaena veneta) in a blend of brewery sludge and cow dung. Int. J. Zool. 2024, 2024, 6615245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degefe, G.; Gizaw, C.A. Comparative evaluation of growth and reproductive performance of Eisenia fetida in various agro-industrial wastes blended with horse manure in Ethiopia. J. Appl. Nat. Sci. 2025, 17, 690–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mupambwa, H.A.; Mnkeni, P.N.S. Eisenia fetida Stocking density optimization for enhanced bioconversion of fly ash enriched vermicompost. J. Environ. Qual. 2016, 45, 1087–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulibaly, S.; Ndegwa, P.; Ayiania, M.; Zoro, I. Growth, reproduction, and life cycle of Eudrilus eugeniae in cocoa and cashew residues. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2019, 143, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngwasiri, P.N.; Ambindei, W.A.; Adanmengwi, V.A.; Ngwi, P.; Mah, A.T.; Ngangmou, N.T.; Fonmboh, D.J.; Ngwabie, N.M.; Ngassoum, M.B.; Aba, E.R. A review paper on agro-food waste and food by-product valorization into value-added products for application in the food industry: Opportunities and challenges for Cameroon bioeconomy. Asian J. Biotechnol. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 9, 32–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, S.I.; Chaudhuri, P.S. Effect of rubber leaf litter diet on growth and reproduction of five tropical species of earthworm under laboratory conditions. J. Appl. Biosci. 2012, 38, 151–155. [Google Scholar]

- Biruntha, M. Growth and reproduction of Perionyx excavatus in different organic wastes. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2013, 2, 28–35. [Google Scholar]

- Bhat, S.A.; Singh, J.; Vig, A.P. Earthworms as Organic Waste Managers and Biofertilizer Producers. Waste Biomass Valoration 2018, 9, 1073–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Karmegam, N.; Singh, G.S.; Bhadauria, T.; Chang, S.W.; Awasthi, M.K.; Sudhakar, S.; Arunachalam, K.D.; Biruntha, M.; Ravindran, B. Earthworms and vermicompost: An eco-friendly approach for repaying nature’s debt. Environ. Geochem. Health 2020, 42, 1617–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.