Left Atrial 4D Flow Characteristics in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation: Comparison with Healthy Controls and Associations with Left Atrial Remodelling and Contractile Health

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Magnetic Resonance Imaging Protocol

2.3. Magnetic Resonance Imaging Analysis

2.3.1. Chamber Volume-Based Measures

2.3.2. Left Atrial Strain

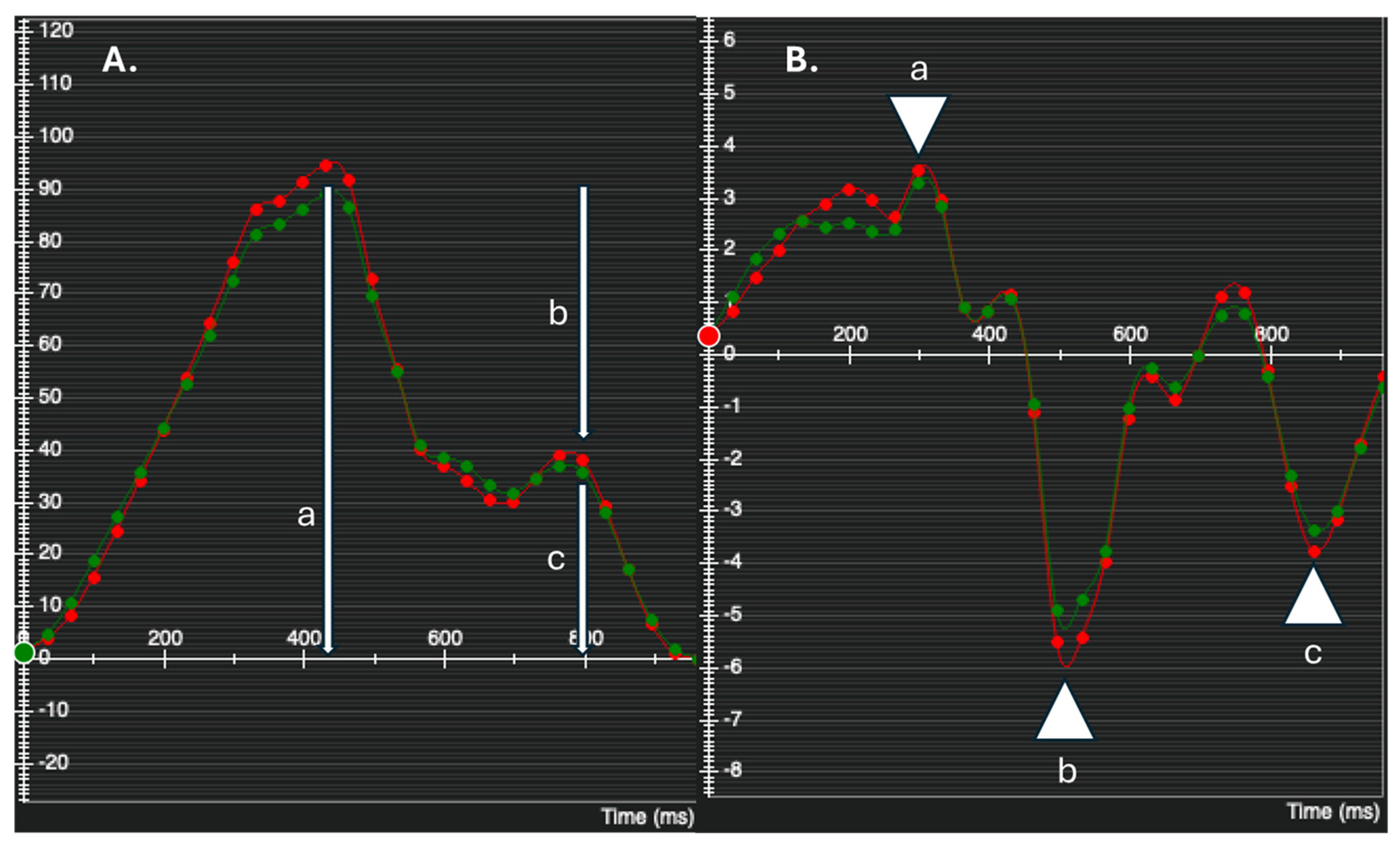

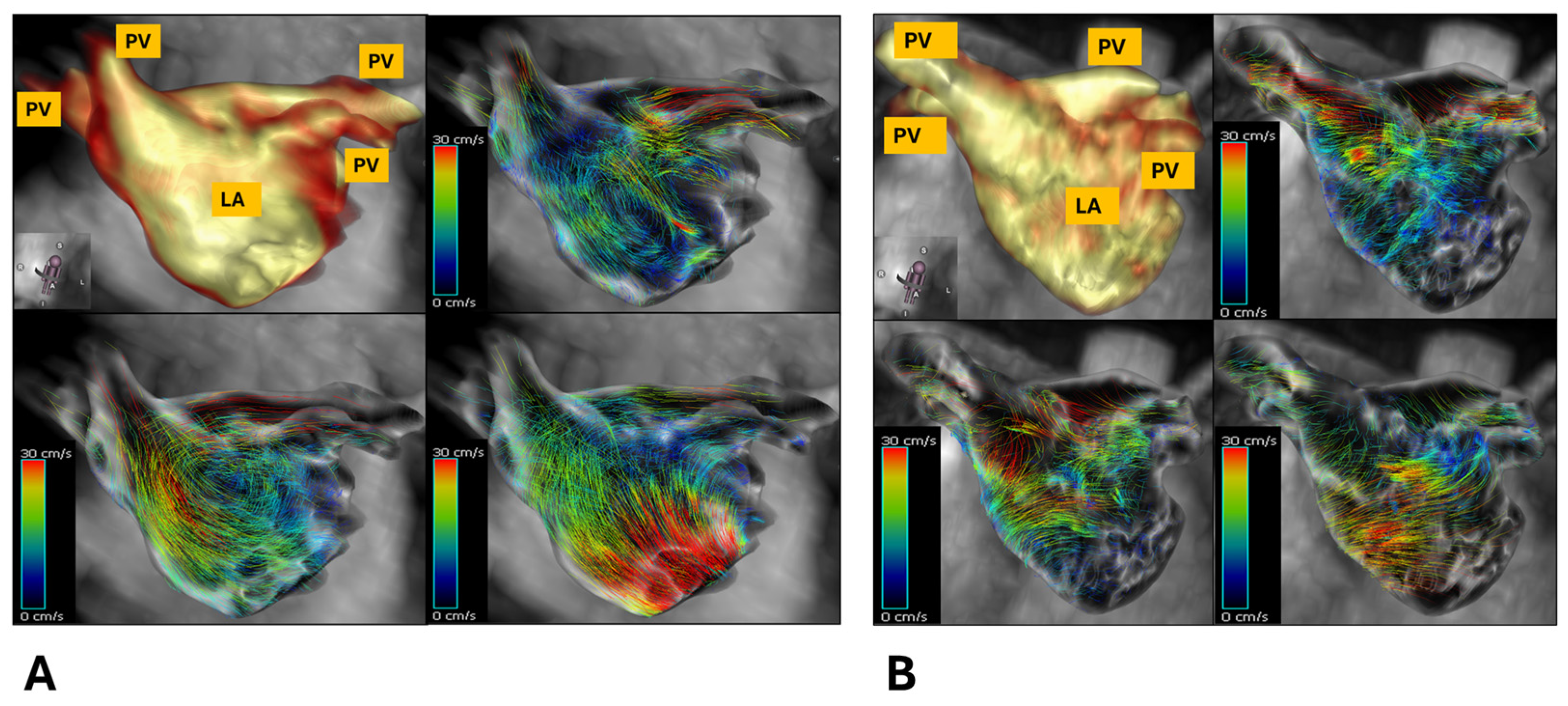

2.3.3. 4D Flow Analysis

2.3.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Characteristics of the Study Cohort

3.2. Magnetic Resonance Imaging Characteristics of Patients Versus Healthy Volunteers

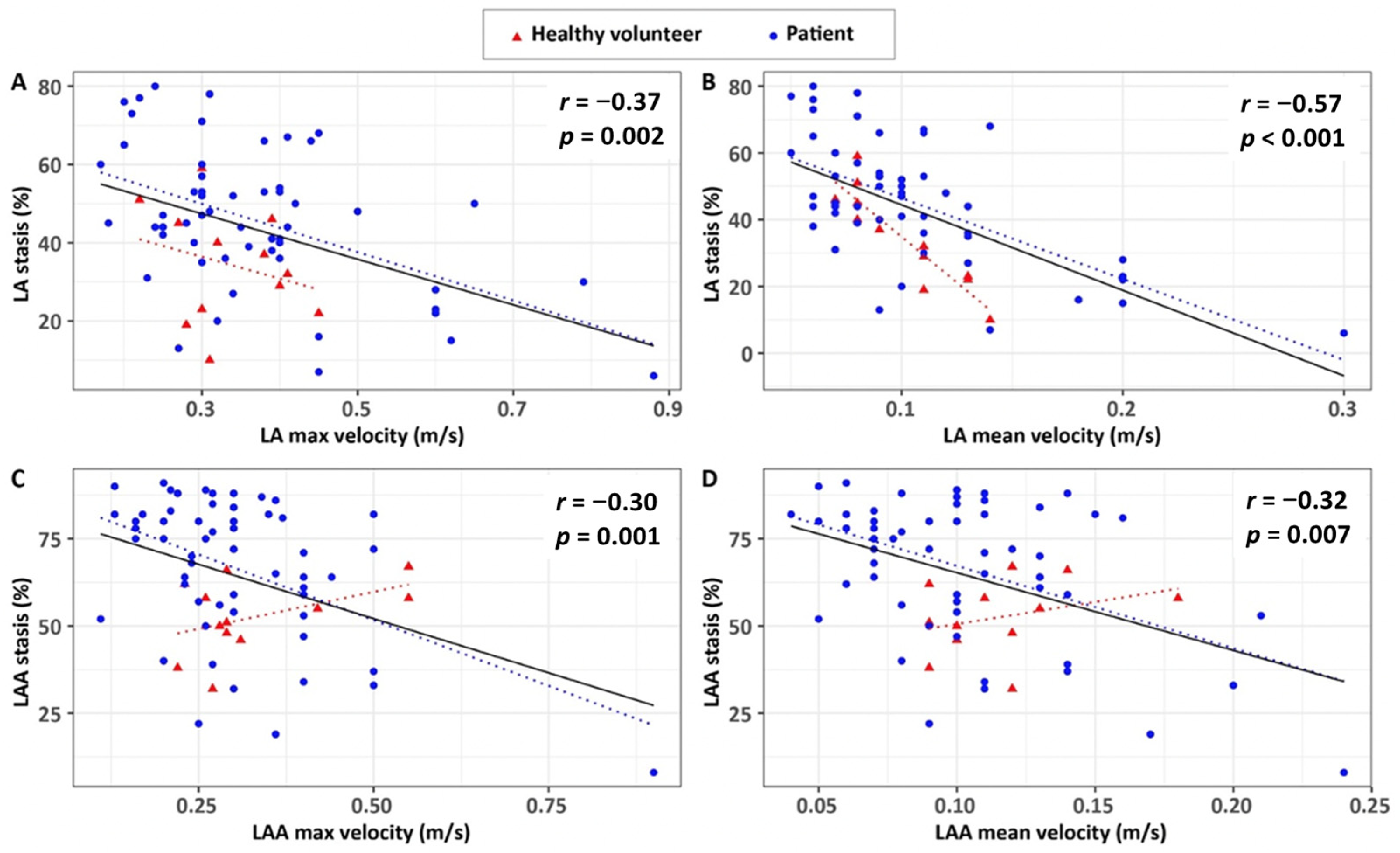

3.3. Associations of 4D Flow Stasis with Flow Velocity

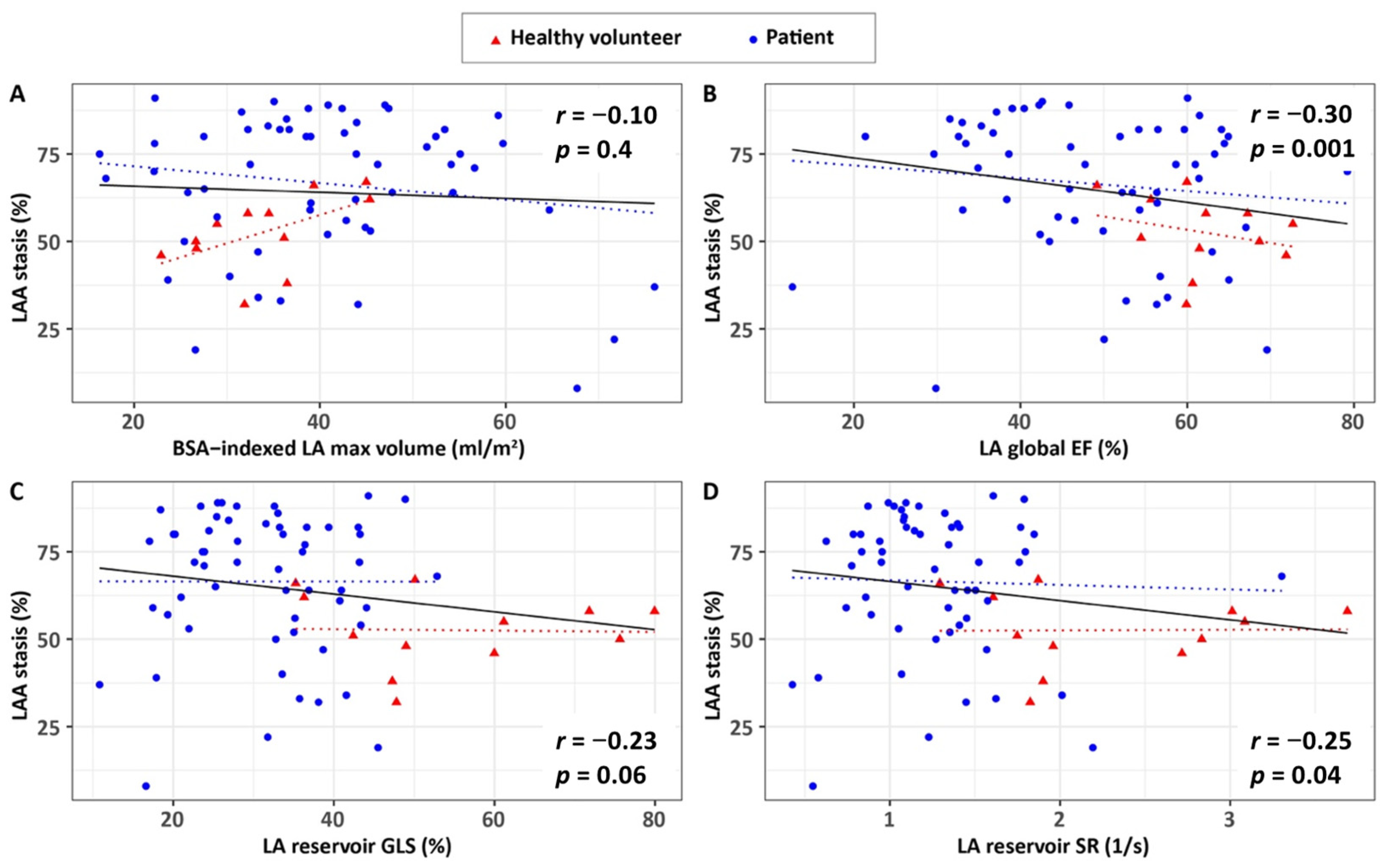

3.4. Associations of 4D Flow Characteristics with Ventricular Volumes and Atrial Remodelling and Contractile Health

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AF | Atrial Fibrillation |

| 4D Flow | Four-dimensional flow |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| PVI | Pulmonary Vein Isolation |

| LA | Left Atrium |

| HV | Healthy Volunteer |

| GLS | Global Longitudinal Strain |

| CIROC | Cardiovascular Imaging Registry of Calgary |

| MRA | Magnetic Resonance Angiography |

| ECG | Electrocardiographic |

| SSFP | Steady-State Free Precession |

| LV | Left Ventricular |

| EF | Ejection Fraction |

| SR | Strain Rate |

| EDV | End-Diastolic Volume |

| LAA | Left Atrial Appendage |

| RTD | Residence Time Distribution |

Appendix A

| Variable | r Overall | p Overall | r HV | p HV | r Patient | p Patient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4D flow LAA mean stasis | ||||||

| Age at scan, y | 0.21 | 0.087 | 0.54 | 0.069 | 0.04 | 0.790 |

| LV and RV volume-based measures | ||||||

| BSA-indexed LV EDV, mL/m2 | −0.10 | 0.420 | 0.16 | 0.610 | −0.11 | 0.420 |

| BSA-indexed LV ESV, mL/m2 | −0.11 | 0.370 | 0.15 | 0.640 | −0.16 | 0.240 |

| LV EF, % | −0.01 | 0.950 | −0.17 | 0.600 | 0.09 | 0.510 |

| BSA-indexed, LV mass, g/m2 | −0.02 | 0.860 | −0.13 | 0.690 | −0.02 | 0.880 |

| BSA-indexed RV EDV, mL/m2 | −0.14 | 0.250 | −0.50 | 0.100 | −0.09 | 0.500 |

| BSA-indexed RV ESV, mL/m2 | −0.12 | 0.310 | −0.26 | 0.420 | −0.08 | 0.570 |

| RV EF, % | 0.07 | 0.570 | −0.08 | 0.800 | 0.05 | 0.730 |

| LA markers of remodelling and contractile health | ||||||

| BSA-indexed LAmax volume, mL/m2 | 0.10 | 0.400 | 0.63 | 0.029 | −0.04 | 0.800 |

| LA global EF, % | −0.30 | 0.011 | −0.27 | 0.400 | −0.19 | 0.150 |

| LA reservoir GLS, % | −0.23 | 0.060 | −0.06 | 0.860 | −0.03 | 0.800 |

| LA reservoir SR, 1/s | −0.25 | 0.039 | −0.15 | 0.650 | −0.05 | 0.700 |

| 4D flow LAA peak velocity | ||||||

| Age at scan, y | 0.09 | 0.480 | 0.22 | 0.490 | 0.11 | 0.420 |

| LV and RV volume-based measures | ||||||

| BSA-indexed LV EDV, mL/m2 | 0.13 | 0.280 | −0.42 | 0.180 | 0.19 | 0.150 |

| BSA-indexed LV ESV, mL/m2 | 0.11 | 0.360 | −0.46 | 0.130 | 0.20 | 0.140 |

| LV EF, % | 0.00 | 0.980 | 0.36 | 0.250 | −0.09 | 0.530 |

| BSA-indexed, LV mass, g/m2 | 0.25 | 0.037 | 0.32 | 0.300 | 0.22 | 0.100 |

| BSA-indexed RV EDV, mL/m2 | 0.16 | 0.200 | 0.00 | 0.990 | 0.16 | 0.230 |

| BSA-indexed RV ESV, mL/m2 | 0.06 | 0.630 | 0.11 | 0.740 | 0.05 | 0.730 |

| RV EF, % | 0.11 | 0.370 | 0.00 | 0.990 | 0.12 | 0.370 |

| LA markers of remodelling and contractile health | ||||||

| BSA-indexed LAmax volume, mL/m2 | 0.15 | 0.220 | −0.22 | 0.490 | 0.22 | 0.100 |

| LA global EF, % | 0.07 | 0.550 | 0.26 | 0.420 | 0.01 | 0.960 |

| LA reservoir GLS, % | 0.04 | 0.760 | 0.40 | 0.200 | −0.08 | 0.560 |

| LA reservoir SR, 1/s | 0.05 | 0.710 | 0.34 | 0.280 | −0.05 | 0.720 |

| 4D flow LAA mean velocity | ||||||

| Age at scan, y | 0.01 | 0.920 | 0.12 | 0.720 | 0.10 | 0.470 |

| LV and RV volume-based measures | ||||||

| BSA-indexed LV EDV, mL/m2 | 0.00 | 0.990 | −0.06 | 0.850 | 0.01 | 0.910 |

| BSA-indexed LV ESV, mL/m2 | −0.01 | 0.930 | −0.08 | 0.800 | 0.01 | 0.960 |

| LV EF, % | 0.03 | 0.790 | 0.06 | 0.840 | 0.00 | 0.997 |

| BSA-indexed, LV mass, g/m2 | 0.20 | 0.097 | 0.49 | 0.100 | 0.17 | 0.200 |

| BSA-indexed RV EDV, mL/m2 | 0.07 | 0.580 | 0.22 | 0.480 | 0.05 | 0.740 |

| BSA-indexed RV ESV, mL/m2 | 0.01 | 0.920 | 0.34 | 0.280 | −0.03 | 0.820 |

| RV EF, % | 0.08 | 0.530 | 0.03 | 0.920 | 0.11 | 0.430 |

| LA markers of remodelling and contractile health | ||||||

| BSA-indexed LAmax volume, mL/m2 | 0.10 | 0.410 | −0.14 | 0.670 | 0.20 | 0.140 |

| LA global EF, % | 0.07 | 0.560 | 0.13 | 0.680 | −0.03 | 0.810 |

| LA reservoir GLS, % | −0.05 | 0.700 | 0.32 | 0.310 | −0.22 | 0.100 |

| LA reservoir SR, 1/s | −0.01 | 0.940 | 0.32 | 0.320 | −0.15 | 0.270 |

| Variable | r Overall | p Overall |

|---|---|---|

| 4D Flow LA Mean Stasis | ||

| BSA-indexed LV EDV, mL/m2 | 0.380 | 0.001 |

| BSA-indexed LV ESV, mL/m2 | 0.464 | <0.001 |

| LV EF, % | 0.464 | <0.001 |

| BSA-indexed, LV mass, g/m2 | 0.310 | 0.009 |

| BSA-indexed RV EDV, mL/m2 | 0.168 5 | 0.166 |

| BSA-indexed RV ESV, mL/m2 | 0.305 | 0.011 |

| RV EF, % | 0.491 | <0.001 |

| LA markers of remodelling and contractile health | ||

| BSA-indexed LAmax volume, mL/m2 | 0.497 | <0.001 |

| LA global EF, % | 0.162 | 0.183 |

| LA reservoir GLS, % | 0.181 | 0.136 |

| LA reservoir SR, 1/s | 0.536 | <0.001 |

| 4D flow LA peak velocity | ||

| BSA-indexed LV EDV, mL/m2 | 0.616 | <0.001 |

| BSA-indexed LV ESV, mL/m2 | 0.781 | <0.001 |

| LV EF, % | 0.878 | <0.001 |

| BSA-indexed, LV mass, g/m2 | 0.654 | <0.001 |

| BSA-indexed RV EDV, mL/m2 | 0.400 5 | 0.001 |

| BSA-indexed RV ESV, mL/m2 | 0.559 | <0.001 |

| RV EF, % | 0.891 | <0.001 |

| LA markers of remodelling and contractile health | ||

| BSA-indexed LAmax volume, mL/m2 | 0.730 | <0.001 |

| LA global EF, % | 0.395 | 0.001 |

| LA reservoir GLS, % | 0.440 | <0.001 |

| LA reservoir SR, 1/s | 0.996 | <0.001 |

| 4D flow LA mean velocity | ||

| BSA-indexed LV EDV, mL/m2 | 0.608 | <0.001 |

| BSA-indexed LV ESV, mL/m2 | 0.778 | <0.001 |

| LV EF, % | 0.876 | <0.001 |

| BSA-indexed, LV mass, g/m2 | 0.656 | <0.001 |

| BSA-indexed RV EDV, mL/m2 | 0.393 5 | 0.001 |

| BSA-indexed RV ESV, mL/m2 | 0.553 | <0.001 |

| RV EF, % | 0.890 | <0.001 |

| LA markers of remodelling and contractile health | ||

| BSA-indexed LAmax volume, mL/m2 | 0.728 | <0.001 |

| LA global EF, % | 0.397 | 0.001 |

| LA reservoir GLS, % | 0.436 | <0.001 |

| LA reservoir SR, 1/s | 0.995 | <0.001 |

| Variable | r Overall | p Overall |

|---|---|---|

| 4D Flow LAA Mean Stasis | ||

| BSA-indexed LV EDV, mL/m2 | 0.342 | 0.004 |

| BSA-indexed LV ESV, mL/m2 | 0.451 | <0.001 |

| LV EF, % | 0.555 | <0.001 |

| BSA-indexed, LV mass, g/m2 | 0.435 | 0.009 |

| BSA-indexed RV EDV, mL/m2 | 0.190 5 | 0.118 |

| BSA-indexed RV ESV, mL/m2 | 0.329 | 0.006 |

| RV EF, % | 0.576 | <0.001 |

| LA markers of remodelling and contractile health | ||

| BSA-indexed LAmax volume, mL/m2 | 0.466 | <0.001 |

| LA global EF, % | 0.165 | 0.176 |

| LA reservoir GLS, % | 0.269 | 0.025 |

| LA reservoir SR, 1/s | 0.592 | <0.001 |

| 4D flow LAA peak velocity | ||

| BSA-indexed LV EDV, mL/m2 | 0.611 | <0.001 |

| BSA-indexed LV ESV, mL/m2 | 0.778 | <0.001 |

| LV EF, % | 0.880 | <0.001 |

| BSA-indexed, LV mass, g/m2 | 0.654 | <0.001 |

| BSA-indexed RV EDV, mL/m2 | 0.396 5 | 0.001 |

| BSA-indexed RV ESV, mL/m2 | 0.556 | <0.001 |

| RV EF, % | 0.731 | <0.001 |

| LA markers of remodelling and contractile health | ||

| BSA-indexed LAmax volume, mL/m2 | 0.731 | <0.001 |

| LA global EF, % | 0.396 | 0.001 |

| LA reservoir GLS, % | 0.440 | <0.001 |

| LA reservoir SR, 1/s | 0.996 | <0.001 |

| 4D flow LAA mean velocity | ||

| BSA-indexed LV EDV, mL/m2 | 0.603 | <0.001 |

| BSA-indexed LV ESV, mL/m2 | 0.771 | <0.001 |

| LV EF, % | 0.881 | <0.001 |

| BSA-indexed, LV mass, g/m2 | 0.650 | <0.001 |

| BSA-indexed RV EDV, mL/m2 | 0.390 5 | 0.001 |

| BSA-indexed RV ESV, mL/m2 | 0.552 | <0.001 |

| RV EF, % | 0.890 | <0.001 |

| LA markers of remodelling and contractile health | ||

| BSA-indexed LAmax volume, mL/m2 | 0.731 | <0.001 |

| LA global EF, % | 0.391 | 0.001 |

| LA reservoir GLS, % | 0.435 | <0.001 |

| LA reservoir SR, 1/s | 0.996 | <0.001 |

References

- Kornej, J.; Börschel, C.S.; Benjamin, E.J.; Schnabel, R.B. Epidemiology of Atrial Fibrillation in the 21st Century. Circ. Res. 2020, 127, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linz, D.; Gawalko, M.; Betz, K.; Hendriks, J.M.; Lip, G.Y.; Vinter, N.; Guo, Y.; Johnsen, S. Atrial fibrillation: Epidemiology, screening and digital health. Lancet Reg. Health-Eur. 2024, 37, 100786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Healey, J.S.; Connolly, S.J.; Gold, M.R.; Israel, C.W.; Van Gelder, I.C.; Capucci, A.; Lau, C.; Fain, E.; Yang, S.; Bailleul, C.; et al. Subclinical Atrial Fibrillation and the Risk of Stroke. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lip, G.Y.H.; Nieuwlaat, R.; Pisters, R.; Lane, D.A.; Crijns, H.J.G.M. Refining Clinical Risk Stratification for Predicting Stroke and Thromboembolism in Atrial Fibrillation Using a Novel Risk Factor-Based Approach. Chest 2010, 137, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friberg, L.; Rosenqvist, M.; Lip, G.Y.H. Evaluation of risk stratification schemes for ischaemic stroke and bleeding in 182 678 patients with atrial fibrillation: The Swedish Atrial Fibrillation cohort study. Eur. Heart J. 2012, 33, 1500–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.C.; Markl, M.; Ng, J.; Carr, M.; Benefield, B.; Carr, J.C.; Goldberger, J.J. Three-dimensional left atrial blood flow characteristics in patients with atrial fibrillation assessed by 4D flow CMR. Eur. Heart J Cardiovasc. Imaging 2016, 17, 1259–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markl, M.; Lee, D.C.; Furiasse, N.; Carr, M.; Foucar, C.; Ng, J.; Carr, J.; Goldberger, J.J. Left Atrial and Left Atrial Appendage 4D Blood Flow Dynamics in Atrial Fibrillation. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2016, 9, e004984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markl, M.; Lee, D.C.; Ng, J.; Carr, M.; Carr, J.; Goldberger, J.J. Left Atrial 4-Dimensional Flow Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Stasis and Velocity Mapping in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. Investig. Radiol. 2016, 51, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirkiran, A.; Amier, R.P.; Hofman, M.B.M.; van der Geest, R.J.; Robbers, L.F.H.J.; Hopman, L.H.G.A.; Mulder, M.J.; van de Ven, P.; Allaart, C.P.; van Rossum, A.C.; et al. Altered left atrial 4D flow characteristics in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation in the absence of apparent remodeling. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 5965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dykstra, S.; Satriano, A.; Cornhill, A.K.; Lei, L.Y.; Labib, D.; Mikami, Y.; Flewitt, J.; Rivest, S.; Sandonato, R.; Feuchter, P.; et al. Machine learning prediction of atrial fibrillation in cardiovascular patients using cardiac magnetic resonance and electronic health information. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 28, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, J.G.; Aguilar, M.; Atzema, C.; Bell, A.; Cairns, J.A.; Cheung, C.C.; Cox, J.L.; Dorian, P.; Gladstone, D.J.; Healey, J.S.; et al. The 2020 Canadian Cardiovascular Society/Canadian Heart Rhythm Society Comprehensive Guidelines for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation. Can. J. Cardiol. 2020, 36, 1847–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, J.; Sheitt, H.; Bristow, M.S.; Lydell, C.; Howarth, A.G.; Heydari, B.; Prato, F.S.; Drangova, M.; Thornhill, R.E.; Nery, P.; et al. Left atrial vortex size and velocity distributions by 4D flow MRI in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: Associations with age and CHA2DS2-VASc risk score. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2020, 51, 871–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheitt, H.; Kim, H.; Wilton, S.; White, J.A.; Garcia, J. Left Atrial Flow Stasis in Patients Undergoing Pulmonary Vein Isolation for Paroxysmal Atrial Fibrillation Using 4D-Flow Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz-Menger, J.; A Bluemke, D.; Bremerich, J.; Flamm, S.D.; A Fogel, M.; Friedrich, M.G.; Kim, R.J.; von Knobelsdorff-Brenkenhoff, F.; Kramer, C.M.; Pennell, D.J.; et al. Standardized image interpretation and post processing in cardiovascular magnetic resonance: Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance (SCMR) Board of Trustees Task Force on Standardized Post Processing. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 2013, 15, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoit, B.D. Left atrial size and function: Role in prognosis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014, 63, 493–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truong, V.T.; Palmer, C.; Wolking, S.; Sheets, B.; Young, M.; Ngo, T.N.M.; Taylor, M.; Nagueh, S.F.; Zareba, K.M.; Raman, S.; et al. Normal left atrial strain and strain rate using cardiac magnetic resonance feature tracking in healthy volunteers. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2019, 21, 446–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, Y.Y.; Buckert, D.; Ma, G.S.; Rasche, V. Quantitative Assessment of Left and Right Atrial Strains Using Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Based Tissue Tracking. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 690240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopman, L.H.; Mulder, M.J.; van der Laan, A.M.; Bhagirath, P.; Demirkiran, A.; von Bartheld, M.B.; Kemme, M.J.; van Rossum, A.C.; Allaart, C.P.; Götte, M.J. Left atrial strain is associated with arrhythmia recurrence after atrial fibrillation ablation: Cardiac magnetic resonance rapid strain vs. feature tracking strain. Int. J. Cardiol. 2023, 378, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Song, Y.; Mu, X. Application of left atrial strain derived from cardiac magnetic resonance feature tracking to predict cardiovascular disease: A comprehensive review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Wilton, S.B.; Garcia, J. Left atrium 4D-flow segmentation with high-resolution contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance angiography. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1225922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fluckiger, J.U.; Goldberger, J.J.; Lee, D.C.; Ng, J.; Lee, R.; Goyal, A.; Markl, M. Left atrial flow velocity distribution and flow coherence using four-dimensional FLOW MRI: A pilot study investigating the impact of age and Pre- and Postintervention atrial fibrillation on atrial hemodynamics. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2013, 38, 580–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markl, M.; Carr, M.; Ng, J.; Lee, D.C.; Jarvis, K.; Carr, J.; Goldberger, J.J. Assessment of left and right atrial 3D hemodynamics in patients with atrial fibrillation: A 4D flow MRI study. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2016, 32, 807–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, B.T.; Voskoboinik, A.; Qadri, A.M.; Rudman, M.; Thompson, M.C.; Touma, F.; La Gerche, A.; Hare, J.L.; Papapostolou, S.; Kalman, J.M.; et al. Measuring atrial stasis during sinus rhythm in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation using 4 Dimensional flow imaging: 4D flow imaging of atrial stasis. Int. J. Cardiol. 2020, 315, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard-Quijano, K.; McCabe, M.; Cheng, A.; Zhou, W.; Yamakawa, K.; Mazor, E.; Scovotti, J.C.; Mahajan, A. Left ventricular endocardial and epicardial strain changes with apical myocardial ischemia in an open-chest porcine model. Physiol. Rep. 2016, 30, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.H.; Oh, Y.-W.; Kim, M.-N.; Park, S.-M.; Shim, W.J.; Shim, J.; Choi, J.-I.; Kim, Y.-H. Relationship between left atrial appendage emptying and left atrial function using cardiac magnetic resonance in patients with atrial fibrillation: Comparison with transesophageal echocardiography. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2016, 32, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Descriptive Statistics |

|---|---|

| Age at scan, y | 59.9 ± 8.9 |

| Male sex | 43 (75%) |

| Cigarette smoking | |

| Never | 44 (80%) |

| Current | 7 (13%) |

| Former | 4 (7%) |

| Alcohol consumption | |

| None/occasional (<1 drink/day) | 46 (81%) |

| Regular (≥1 drink/day) | 11 (19%) |

| Diabetes mellitus * | 3 (5%) |

| Hypertension | 13 (23%) |

| Dyslipidemia † | 35 (61%) |

| Hypothyroidism | 6 (11%) |

| Hyperthyroidism | 1 (2%) |

| Chronic kidney disease ‡ | 5 (9%) |

| Atrial fibrillation type | |

| Paroxysmal | 46 (81%) |

| Persistent | 11 (19%) |

| CHA2DS2-VASc score | 1 (1, 2) |

| Dyspnea (NYHA class ≥ II) | 13 (24%) |

| QoL (EuroQol EQ VAS) | 80 (70, 85) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 28.0 ± 4.8 |

| Obesity § | 17 (30%) |

| Medications | |

| Aspirin | 6 (11%) |

| Beta blocker | 40 (70%) |

| ACEi/ARB | 18 (32%) |

| Calcium channel blocker | 10 (18%) |

| Anti-coagulant | 56 (98%) |

| Anti-Arrhythmic | 46 (81%) |

| Loop diuretic | 2 (4%) |

| Statin | 16 (28%) |

| Labs | |

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 148.5 ± 11.5 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 92.5 ± 27.8 |

| CMR Characteristics | HV (n = 12) | Patients with AF (n = 57) | p-Value | p-Value * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chamber volumes | ||||

| BSA-indexed LV EDV, mL/m2 | 83.0 ± 6.6 | 81.8 ± 13.5 | 0.640 | 0.005 |

| BSA-indexed LV ESV, mL/m2 | 30.4 ± 5.3 | 31.3 ± 6.9 | 0.590 | <0.001 |

| LV EF, % | 63.6 ± 4.2 | 61.5 ± 6.1 | 0.17 | <0.001 |

| BSA-indexed, LV mass, g/m2 | 54.2 ± 7.0 | 55.0 ± 11.6 | 0.760 | <0.001 |

| BSA-indexed RV EDV, mL/m2 | 97.0 ± 6.6 | 90.4 ± 18.9 | 0.042 | 0.108 |

| BSA-indexed RV ESV, mL/m2 | 44.1 ± 6.4 | 40.5 ± 11.3 | 0.140 | 0.003 |

| RV EF, % | 54.7 ± 4.7 | 55.6 ± 6.4 | 0.580 | <0.001 |

| LAmax volume, mL | 67.9 ± 16.4 | 85.0 ± 27.1 | 0.008 | <0.001 |

| BSA-indexed LAmax volume, mL/m2 | 33.8 ± 7.1 | 40.8 ± 13.3 | 0.015 | <0.001 |

| LAmin volume, mL | 26.4 ± 9.9 | 45.1 ± 20.9 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| BSA-indexed LAmin volume, mL/m2 | 13.2 ± 4.7 | 21.9 ± 11.4 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Pre-atrial systole LA volume, mL | 47.5 ± 14.6 | 63.4 ± 22.4 | 0.005 | <0.001 |

| BSA-indexed pre-atrial systole LA volume, mL/m2 | 23.7 ± 6.7 | 30.6 ± 11.8 | 0.010 | <0.001 |

| LA function | ||||

| LA global EF, % | 62.0 ± 7.1 | 48.5 ± 13.2 | <0.001 | 0.550 |

| LA booster EF, % | 45.3 ± 7.2 | 30.7 ± 13.7 | <0.001 | 0.771 |

| LA conduit EF, % | 30.7 ± 8.5 | 26.0 ± 10.5 | 0.110 | 0.002 |

| LA reservoir GLS, % | 54.7 ± 15.0 | 31.3 ± 9.5 | <0.001 | 0.098 |

| LA booster GLS, % | 21.7 ± 8.5 | 13.9 ± 6.7 | 0.010 | 0.056 |

| LA conduit GLS, % | 33.0 ± 9.4 | 17.4 ± 5.9 | <0.001 | 0.881 |

| LA reservoir SR, 1/s | 2.30 ± 0.74 | 1.26 ± 0.47 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| LA conduit SR, 1/s | −3.84 ± 1.12 | −1.73 ± 0.63 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| LA booster SR, 1/s | −2.11 ± 0.80 | −1.23 ± 0.66 | 0.003 | <0.001 |

| LA and LAA 4D flow characteristics | ||||

| LA mean stasis, % | 34.5 (22.8, 45.3) | 45.0 (36.0, 54.0) | 0.040 | <0.001 |

| LA peak velocity, m/s | 0.32 (0.30, 0.39) | 0.33 (0.28, 0.41) | 0.840 | <0.001 |

| LA mean velocity, m/s | 0.10 (0.08, 0.12) | 0.09 (0.07, 0.11) | 0.500 | <0.001 |

| LAA mean stasis, % | 53.0 (47.5, 59.0) | 72.0 (56.0, 82.0) | 0.005 | <0.001 |

| LAA peak velocity, m/s | 0.29 (0.27, 0.34) | 0.28 (0.23, 0.36) | 0.420 | <0.001 |

| LAA mean velocity, m/s | 0.12 (0.10, 0.12) | 0.10 (0.07, 0.13) | 0.130 | <0.001 |

| Variable | r All | p All | r HV | p HV | r Patient | p Patient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LA mean stasis | ||||||

| LA peak velocity, m/s | −0.37 | 0.002 | −0.28 | 0.380 | −0.39 | 0.003 |

| LA mean velocity, m/s | −0.57 | <0.001 | −0.90 | <0.001 | −0.52 | <0.001 |

| LAA mean stasis | ||||||

| LAA peak velocity, m/s | −0.30 | 0.011 | 0.35 | 0.270 | −0.35 | 0.007 |

| LAA mean velocity, m/s | −0.32 | 0.007 | 0.32 | 0.310 | −0.31 | 0.021 |

| Variable | r Overall | p Overall | r HV | p HV | r Patient | p Patient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

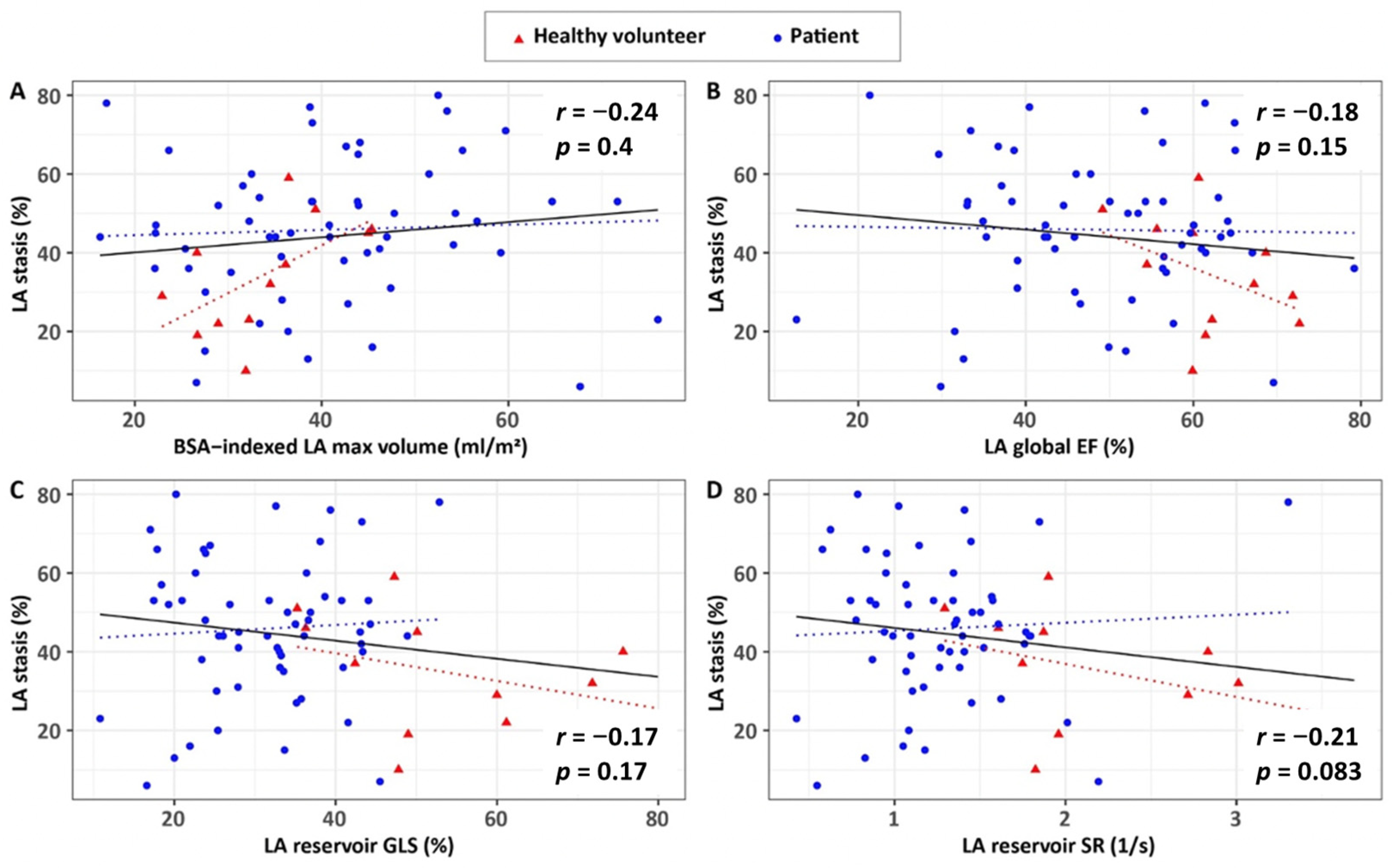

| 4D flow LA mean stasis | ||||||

| Age at scan, y | 0.10 | 0.430 | 0.19 | 0.550 | 0.01 | 0.920 |

| LV and RV volume-based measures | ||||||

| BSA-indexed LV EDV, mL/m2 | 0.07 | 0.590 | 0.13 | 0.700 | 0.05 | 0.730 |

| BSA-indexed LV ESV, mL/m2 | 0.06 | 0.630 | 0.43 | 0.160 | −0.02 | 0.880 |

| LV EF, % | −0.11 | 0.390 | −0.62 | 0.033 | 0.03 | 0.800 |

| BSA-indexed, LV mass, g/m2 | −0.10 | 0.390 | −0.39 | 0.210 | −0.11 | 0.430 |

| BSA-indexed RV EDV, mL/m2 | −0.05 | 0.700 | −0.40 | 0.200 | −0.01 | 0.950 |

| BSA-indexed RV ESV, mL/m2 | −0.02 | 0.850 | −0.23 | 0.470 | −0.01 | 0.920 |

| RV EF, % | −0.04 | 0.760 | −0.43 | 0.160 | −0.01 | 0.940 |

| LA markers of remodelling and contractile health | ||||||

| BSA-indexed LAmax volume, mL/m2 | 0.24 | 0.044 | 0.67 | 0.017 | 0.14 | 0.290 |

| LA global EF, % | −0.18 | 0.150 | −0.42 | 0.170 | −0.05 | 0.710 |

| LA reservoir GLS, % | −0.17 | 0.170 | −0.45 | 0.140 | −0.01 | 0.950 |

| LA reservoir SR, 1/s | −0.21 | 0.083 | −0.47 | 0.120 | −0.06 | 0.650 |

| 4D flow LA peak velocity | ||||||

| Age at scan, y | −0.06 | 0.610 | 0.27 | 0.390 | −0.15 | 0.250 |

| LV and RV volume-based measures | ||||||

| BSA-indexed LV EDV, mL/m2 | 0.21 | 0.089 | 0.00 | 0.990 | 0.23 | 0.090 |

| BSA-indexed LV ESV, mL/m2 | 0.17 | 0.170 | −0.31 | 0.320 | 0.23 | 0.080 |

| LV EF, % | −0.05 | 0.670 | 0.61 | 0.035 | −0.13 | 0.320 |

| BSA-indexed, LV mass, g/m2 | 0.25 | 0.035 | −0.09 | 0.79 | 0.28 | 0.030 |

| BSA-indexed RV EDV, mL/m2 | 0.22 | 0.069 | −0.28 | 0.370 | 0.29 | 0.030 |

| BSA-indexed RV ESV, mL/m2 | 0.16 | 0.190 | −0.52 | 0.084 | 0.23 | 0.080 |

| RV EF, % | 0.00 | 0.990 | 0.47 | 0.120 | −0.07 | 0.590 |

| LA markers of remodelling and contractile health | ||||||

| BSA-indexed LAmax volume, mL/m2 | −0.06 | 0.630 | −0.33 | 0.290 | −0.02 | 0.870 |

| LA global EF, % | 0.11 | 0.350 | 0.55 | 0.070 | 0.09 | 0.490 |

| LA reservoir GLS, % | −0.002 | 0.990 | 0.32 | 0.320 | −0.01 | 0.940 |

| LA reservoir SR, 1/s | 0.06 | 0.610 | 0.40 | 0.200 | 0.05 | 0.700 |

| 4D flow LA mean velocity | ||||||

| Age at scan, y | −0.19 | 0.120 | −0.23 | 0.480 | −0.21 | 0.110 |

| LV and RV volume-based measures | ||||||

| BSA-indexed LV EDV, mL/m2 | −0.01 | 0.930 | −0.31 | 0.320 | 0.02 | 0.860 |

| BSA-indexed LV ESV, mL/m2 | 0.02 | 0.890 | −0.50 | 0.100 | 0.10 | 0.460 |

| LV EF, % | 0.00 | 0.980 | 0.60 | 0.038 | −0.14 | 0.300 |

| BSA-indexed, LV mass, g/m2 | 0.24 | 0.051 | 0.55 | 0.062 | 0.20 | 0.130 |

| BSA-indexed RV EDV, mL/m2 | 0.14 | 0.250 | 0.29 | 0.370 | 0.14 | 0.310 |

| BSA-indexed RV ESV, mL/m2 | 0.09 | 0.470 | 0.07 | 0.820 | 0.11 | 0.410 |

| RV EF, % | 0.00 | 0.980 | 0.52 | 0.080 | −0.06 | 0.630 |

| LA markers of remodelling and contractile health | ||||||

| BSA-indexed LAmax volume, mL/m2 | −0.23 | 0.054 | −0.59 | 0.044 | −0.15 | 0.260 |

| LA global EF, % | 0.19 | 0.120 | 0.42 | 0.170 | 0.12 | 0.360 |

| LA reservoir GLS, % | 0.03 | 0.820 | 0.47 | 0.120 | −0.07 | 0.580 |

| LA reservoir SR, 1/s | 0.11 | 0.370 | 0.55 | 0.070 | 0.03 | 0.830 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sheitt, H.; Labib, D.; Yakimenka, A.; Serran, M.L.; Dykstra, S.; Flewitt, J.; Wilton, S.B.; Rivest, S.; White, J.A.; Garcia, J. Left Atrial 4D Flow Characteristics in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation: Comparison with Healthy Controls and Associations with Left Atrial Remodelling and Contractile Health. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010194

Sheitt H, Labib D, Yakimenka A, Serran ML, Dykstra S, Flewitt J, Wilton SB, Rivest S, White JA, Garcia J. Left Atrial 4D Flow Characteristics in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation: Comparison with Healthy Controls and Associations with Left Atrial Remodelling and Contractile Health. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):194. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010194

Chicago/Turabian StyleSheitt, Hana, Dina Labib, Alena Yakimenka, Malcolm L. Serran, Steven Dykstra, Jacqueline Flewitt, Stephen B. Wilton, Sandra Rivest, James A. White, and Julio Garcia. 2026. "Left Atrial 4D Flow Characteristics in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation: Comparison with Healthy Controls and Associations with Left Atrial Remodelling and Contractile Health" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010194

APA StyleSheitt, H., Labib, D., Yakimenka, A., Serran, M. L., Dykstra, S., Flewitt, J., Wilton, S. B., Rivest, S., White, J. A., & Garcia, J. (2026). Left Atrial 4D Flow Characteristics in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation: Comparison with Healthy Controls and Associations with Left Atrial Remodelling and Contractile Health. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010194