Abstract

High concentrations of anthocyanin pigments and vitamin C are the principal health-promoting constituents in black currant (Ribes spp.) berries. This study aimed to develop a rapid greener protocol—reducing the analytical workload, application of toxic solvents, and processing time—for analysis of anthocyanins in black currants. The influence of several laboratory factors on anthocyanin extraction was assessed (berry size, disintegration method). A rapid and robust RP-HPLC-DAD method was developed and validated for the separation and quantification of anthocyanins across 123 black currant genotypes. The optimized method employing a Kinetex C18 column demonstrated excellent sensitivity and reproducibility, achieving complete separation within 11 min. Extraction using 50% (v/v) ethanol acidified with 0.36 N HCl proved superior to methanol-based solvents. Single extraction produced similar extract concentration to triple extraction; cryogenic grinding enhanced anthocyanin extractability by approximately 25%. Smaller berries within the genotype contained higher anthocyanin levels than larger berries. On average, delphinidin 3-O-glucoside, delphinidin 3-O-rutinoside, cyanidin 3-O-glucoside, and cyanidin 3-O-rutinoside contributed 12.5%, 43.7%, 6.2%, and 35.0% of total anthocyanin content, respectively, and 97.5% of total anthocyanins, ranging from 90.5% to 98.8%. The developed greener chemistry-compliant protocols facilitate rapid, safe, and reliable high-throughput screening of anthocyanin profiles in black currant, useful for breeding programs and analytical workflows.

1. Introduction

Black currant (Ribes nigrum, Grossulariaceae family), and its interspecific crosses, is increasingly acknowledged for its high nutritional value, mainly by exceptionally high vitamin C and anthocyanins content and diverse bioactive properties [1,2,3]. These combined phytochemical attributes make black currant a unique raw material for functional food and beverage formulations and nutraceutical product with health benefits and therapeutic potential [4,5,6]. Black currant-based food products rich in anthocyanins can counteract fat-induced metabolic stress and aid cardiovascular protection [7], reduce postprandial blood glucose, incretin, and insulin levels [8], improve sleep quality in healthy older adults [9], or even improve athletic performance [10]. The steady growth in the production of black currant berries and value-added products derived from them, coupled with mounting evidence of their positive impact on human health, underscores the scientific and practical rationale for ongoing research on black currant.

Interspecific hybridization is a core strategy in modern Ribes breeding, enabling the transfer of agronomically valuable traits from related species into improved black currant (Ribes nigrum L.) germplasm. Such crosses have been used to introgress enhanced pest and disease resistance, especially pathogens such as Cecidophyopsis ribis (black currant gall mite), Podosphaera mors-uvae (powdery mildew of currant) and Pseudopeziza ribis, along with berry yield and quality [11,12,13,14,15,16]. Interspecific crosses expand the selection base for breeding programs and enhance metabolic diversity, but research on anthocyanin composition in interspecific black currant crosses remains scarce [2,14,15,17]. This limits informed conclusions on the biochemical consequences of interspecific hybridization.

The anthocyanin fraction of black currants is dominated by delphinidin and cyanidin glycosides—delphinidin 3-O-rutinoside (del 3-O-rut), delphinidin 3-O-glucoside (del 3-O-glu), cyanidin 3-O-rutinoside (cya 3-O-rut) and cyanidin 3-O-glucoside (cya 3-O-glu)—which together account for the vast majority of total anthocyanins constituting 92–97% [18] or even 97–98% [19]. Beyond the four typical main black currant anthocyanins, an additional ten to eleven minor anthocyanins have been identified [20,21,22]. Despite those findings, these minor compounds are frequently excluded from routine quantification [19,23]. Nevertheless, interspecific hybridization can substantially modify the phytochemical profile, potentially enhancing not only the levels of major but also minor anthocyanins. For example, Ribes dikuscha exhibits a pronounced accumulation of petunidin glycosides [3], suggesting that hybrid lines derived from this species may display elevated concentrations of this anthocyanin subclass. To date, most studies have focused on a limited number of black currant cultivars, typically analyzing only up to a couple dozen genotypes. The most extensive reports include 32 and 37 cultivars. The concentration ranges for individual studies exhibit wide variability in the reported anthocyanin concentration ranges and are as follows (expressed in mg 100 g−1 FW): 116–288 (3 cultivars) [18], 143–176 (3 cultivars) [24], 79–311 (15 cultivars) [19], 83–199 (17 genotypes) [25], 276–670 (32 varieties) [2], and 174–456 (37 cultivars) [26]. Given this inconsistency, a comprehensive large-scale study encompassing a wide genetic spectrum—and quantifying both major and minor anthocyanins—is warranted to provide a more robust and representative understanding of anthocyanin diversity in black currant germplasm.

Accurate profiling of anthocyanins in large and genetically diverse black currant populations remains analytically challenging due to the sensitivity of these pigments to solvent composition, pH, temperature, and oxidative degradation during extraction, as well as the strong dependence of recovery on the degree of tissue homogenization and method of extraction [27,28,29,30,31]. Methanol has frequently been substituted with ethanol in anthocyanin extraction protocols to improve safety and environmental compatibility; however, the ethanol concentration employed varies widely among studies (30–95%) [3,18,27,30], underscoring the need for methodological re-validation. Sample homogenization represents another critical factor influencing extraction efficiency. Studies on chokeberry have shown that cryogenic milling markedly enhances anthocyanin recovery by reducing particle size and increasing the effective extraction surface area [32]. Conversely, investigations on black currant remain limited on the aspect of sample preparation, with some reports even omitting sample homogenization entirely using only berry immersion in the solvent followed by maceration [3,18]. The absence of standardized extraction protocols can contribute to the broad variation in reported anthocyanin concentrations across the literature. Although the C18 column is most commonly used for HPLC separation of anthocyanins in black currants [2,14,23,33], alternative stationary phases are seldom explored [19]. Furthermore, analytical throughput remains constrained by extended run times. Recent reports still utilize 50 min HPLC protocols for black currant anthocyanin separation [23], despite existing substantially faster methods achieving comparable resolution within 13 min [19,34]. These observations emphasize an urgent need for disseminating and promoting rapid, robust, and eco-efficient analytical approaches to support the increasing industrial demand and the expanding scale of black currant breeding programs.

The present study was designed with four primary objectives: (i) to develop and validate a rapid, high-resolution RP-HPLC-DAD method capable of separating both major and low-abundance anthocyanins within a short run time, (ii) to optimize an extraction protocol that maximizes anthocyanin recovery while reducing solvent use and improving environmental compatibility, and (iii) to systematically assess how laboratory factors—such as homogenization strategy, e.g., cryogenic milling, and berry size—affect quantitative anthocyanin yields. A fourth objective was to comprehensively characterize the anthocyanin composition across 123 interspecific black currant crosses, providing one of the most extensive datasets generated to date for the genus Ribes. The novelty of this work lies in combining a multi-analytical, eco-efficient workflow with large-scale genetic screening, enabling both high throughput and enhanced detection of minor anthocyanins that are typically underreported due to methodological limitations. This integrated approach provides new insights into the biochemical diversity of interspecific progeny and establishes a robust analytical framework for future breeding, nutritional, and metabolomic research.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

Hydrochloric acid (reagent grade), methanol, and formic acid (HPLC grade) were received from Sigma-Aldrich (Steinheim, Germany). Ethanol (96.2%, v/v) for lab-scale extraction of anthocyanins was purchased from SIA Kalsnavas Elevators (Jaunkalsnava, Latvia). The anthocyanin standards—del 3-O-glu, del 3-O-rut, cya 3-O-glu, cya 3-O-rut (≥95%, HPLC purity)—were obtained from Extrasynthèse (Genay, France).

2.2. Plant Material

A total of 123 genotypes of black currant (Ribes spp.) were collected at optimal ripeness between July and August 2024 from the experimental plantation of the Institute of Horticulture (Dobele, Latvia). For each genotype, 100–200 g of randomly selected berries were harvested from single 6–7-year-old bushes cultivated for genotypic selection. In order to assess the effect of berry size on anthocyanin content, the berries were divided into two size fractions: small, with a diameter equal to or less than 7–10 mm (depending on genotype); and large, with a diameter greater than described above. The samples were frozen at −18 °C and stored for six months prior to analysis.

2.3. Anthocyanin Extraction Experiments

After thawing at 21 °C for 2 h, berries were homogenized using a domestic blender. To assess the effects of various factors on extraction efficiency, 1–3 berries from each genotype (200 ± 20 g total) were selected. Five grams of blended material were placed in a 50 mL stainless steel jar, immersed in liquid nitrogen for 15 min, and cryogenically milled (30 s at 30 Hz) using an MM 400 mixer mill (Retsch, Haan, Germany), yielding a powder of ~5 μm. Subsequently, 0.5 g of sample was transferred to a 15 mL tube, combined with 10 mL of aqueous methanol or ethanol, mixed (1 min at 3500 rpm) using vortex Reax top (Heidolph, Schwabach, Germany), and extracted by ultrasonication in an ultrasonic bath (Sonorex RK 510 H, Bandelin electronic, Berlin, Germany) at the following parameters: power—160 W, temperature—60 °C, frequency—35 kHz, time—15 min. After sonication, samples were mixed for 1 min and centrifuged at 11,000× g for 5 min at 21 °C. The supernatant was filtered through a 0.2 μm nylon syringe filter into 2 mL glass vials and analyzed directly using the RP-HPLC-DAD system. The moisture content of fresh berries immersed in liquid nitrogen and cryogenically milled was determined gravimetrically.

2.3.1. Effect of Solvent Type and Concentration

Methanol and ethanol at 50, 60, 70, and 80% (v/v) acidified with 0.36 N HCl were evaluated as extraction solvents according to the procedure in Section 2.3.

2.3.2. Effect of Acid Type and Temperature of Extraction

To test the impact of the acid used and the temperature of extraction, the application of 0.36 N HCl and 1% formic acid at 60 °C, and different temperatures (30 °C, 40 °C, 50 °C, and 60 °C) for extracts acidified with 0.36 N HCl, were compared. For this purpose, a single extraction (Section 2.3) with optimized solvent (Section 2.3.1) was performed for the mix of different black currant berry genotypes cryogenically milled.

2.3.3. Effect of Re-Extraction

To assess the necessity of re-extraction, the efficiency of single vs. triple extraction was compared. After the first extraction (Section 2.3), the supernatant was collected and the residue was re-extracted twice with 7 mL of optimized solvent (Section 2.3.1). Combined extracts were made up to 25 mL, mixed, filtered, and analyzed. Data were normalized to a total equivalent volume of 10.5 mL for single extraction.

2.3.4. Effect of Sample Homogenization

Anthocyanin yields from blended samples were compared with those subjected to additional cryogenic grinding to evaluate the effect of sample homogenization and reproducibility. Extractions were performed using the optimized solvent (Section 2.3.1).

2.3.5. Effect of Berry Size and Genotype

Each genotype was divided into small and large size groups. The range of tested berries for this experiment was between 40 and 80 g for each of the analyzed samples, both small and large. The diameters of 10 randomly selected fruits per size group were measured before extraction (Section 2.3) using the optimized solvent (Section 2.3.1).

2.4. Screening and Optimization of Anthocyanins Separation via RP-HPLC-DAD

Seven stationary phases (C18, XB-C18, EVO C18, Biphenyl, Phenyl-Hexyl, and two pentafluorophenylpropyl phases PFP, and F5 (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA)) were evaluated for anthocyanin separation using SPP Kinetex columns (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm). Methanol was used instead of acetonitrile for environmental reasons. Optimal separation was achieved on a Kinetex C18 column using 4% formic acid in water (A) and methanol (B), with the following gradient: 15% B (0.01 min), 40% B (4.0 min), 80% B (5.0–6.0 min), 15% B (7.0–11.0 min). The flow rate was 1.0 mL min−1, column temperature 50 °C, and total runtime 11 min. Analyses were conducted on a Shimadzu Nexera 40 Series system (Kyoto, Japan), which consisted of a CBM-40 controller, LC-40D pump, a DGU-405 degasser, an SIL-40C autosampler, a CTO-40C column oven, and an SPD-M40 diode-array detector (DAD). Standard solutions of anthocyanins were prepared in methanol containing 0.1% HCl (v/v) to determine calibration curves, and detection was performed at 520 nm. The minor anthocyanins were semi-quantified using the cya 3-O-glu calibration curve as an equivalent. To identify the detected minor anthocyanins, unidentified peaks were repeatedly collected during 5–10 injections at the capillary outlet into glass flasks during analytical chromatographic runs. The combined fractions were concentrated under reduced pressure, reconstituted in 500 μL of methanol containing 0.1% HCl, and subsequently analyzed for compound identification using high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS).

2.5. Method Validation

The analytical method was validated using a Kinetex C18 column secured with a Synergi Fusion-RP guard (4 × 3 mm) (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA). Selectivity was confirmed by injecting 2 µL of methanol containing 0.1% HCl (v/v) (blank solution), standards, and extracts obtained from 123 genotypes of black currant injections. Linearity was verified for concentrations 2.34–179.76 ng by injecting different volumes of standards mixture (0.2–10 µL). Reproducibility of retention times and precision (repeatability and reproducibility) of quantification for the four major anthocyanins was tested across three consecutive days using extracts from the cultivar ‘Ijunskaya Kondrashovoi’. The sample was prepared on day one and stored in the refrigerator (4 °C) during the three-day test. The limit of detection (LOD) was obtained based on a signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) of 3, while limit of quantification (LOQ) was calculated according to the following equation: LOQ = 3.3 × LOD. The S/N ratio was calculated by the LabSolutions software, Version 5.110 (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) and confirmed by the injection of similar concentrations of four primary anthocyanin standards as calculated LOD values.

2.6. LC-HRMS Method for Compound Identification

Chromatographic separation of the isolated extracts was carried out using an UltiMate 3000 HPLC system (Dionex, Germering, Germany). The column oven temperature was maintained at 35 °C, and the autosampler was kept at 15 °C. A 5 µL aliquot of each sample was injected for analysis. Separation was achieved on a Kinetex C18 column—50 × 3 mm, 1.7 µm (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA). Mobile phase (A) consisted of water containing 2% formic acid, and mobile phase (B) was methanol. The flow rate was set to 0.3 mL min−1.

The gradient elution program was as follows: 10% B from 0 to 1 min; a linear increase to 95% B between 1 and 9.5 min; maintained at 95% B from 9.5 to 12 min; then increased to 100% B over 12–15 min; held at 100% B for 15–17 min; returned to 10% B at 17–17.1 min; and re-equilibrated at 10% B for 17.1–20 min.

Mass spectra were acquired by a Q-Exactive Orbitrap MS system (Thermo Scientific, Dreieich, Germany) equipped with an electrospray ionization source (ESI) operating in both positive and negative ionization modes. Full-scan and data-dependent MS/MS (ddMS2) modes were executed at resolutions of 70,000 and 17,500 FWHM (at m/z 200), respectively. The full-scan mode scanning range spanned from 100 to 1500 m/z, while for ddMS2 mode, automatic range selection was enabled without a fixed first mass. Production of spectra was generated by employing stepped normalized collision energy (NCE) at 10%, 25%, and 40%. The mass accuracy of the Orbitrap HRMS system (<5 ppm) was upheld through an external calibration method by introducing a mixture containing caffeine, MRFA, Ultramark 1621, and n-butyl amine before each sequence. Data acquisition was managed using Thermo Scientific Xcalibur (v. 4.1). Compound identification was conducted in Thermo Scientific TraceFinder™ (v. 4.1) using mzCloud (https://www.mzcloud.org), Mass Bank of North America (https://mona.fiehnlab.ucdavis.edu), Plant Specialized Metabolome Annotation (PlaSMA, https://metabobank.riken.jp), and MassBank Europe (https://massbank.eu/MassBank/) mass spectra libraries (all websites accessed: 1 November 2025).

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Anthocyanin contents were statistically analyzed based on berry fraction by size and genotype by berry size. The mean berry size and mean anthocyanin content was calculated for all genotypes. The genotypes were further grouped according to their mean berry size (below or above mean value for all investigated genotypes) into small- and large-berry genotypes. The mean value dataset was analyzed identically to the whole dataset. This grouping approach deviated from the initial berry sorting condition but achieved a more even distribution.

RStudio (Posit Software, Boston, MA, USA) (“Cucumberleaf Sunflower” Release (20de3565, 2 September 2025) for windows) was used for data preparation and restructuring. R base and open-source packages readxl, dplyr, GGally, ggplot2, ggthemes, forcats, scales, ggExtra, ggforce, patchwork, tidyr, factoextra, and ggpubr were used for data structuring and analysis. Spearman rank correlation analysis was used for correlation analysis, and results were expressed as the Spearman rank correlation coefficient (ρ). Linear regression analysis was performed in MS Excel; other statistical analyses were performed in RStudio interface using the aforementioned packages: multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA), multivariate analysis of co-variance (MANCOVA), principal component analysis (PCA), and non-hierarchical k-means cluster analysis.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Separation Optimization and Validation

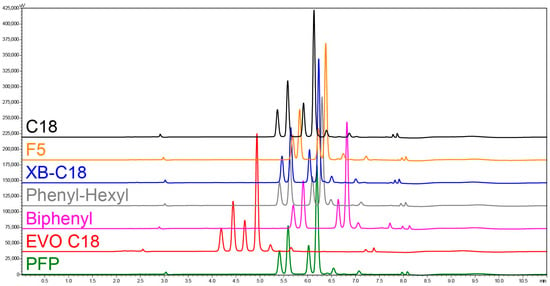

The comparative analysis of anthocyanin interactions with seven stationary phases (C18, XB-C18, EVO C18, Biphenyl, Phenyl-Hexyl, PFP, and F5) demonstrated distinct differences in separation efficiency (Rs) and sensitivity indirectly due to the obtained narrow peaks under the developed gradient conditions (Figure 1). The optimized gradient, providing a total run time of only 11 min, enabled baseline separation (Rs ≥ 1.5) of the four primary anthocyanins—del 3-O-glu, del 3-O-rut, cya 3-O-glu, and cya 3-O-rut—across all tested columns, except for the F5 phase, where partial coelution was observed for del 3-O-glu and del 3-O-rut (Rs = 1.4). This outcome highlights that the developed gradient not only ensures rapid chromatographic resolution but also offers broad applicability across a range of stationary phases—an advantage for laboratories lacking access to specifically optimized columns. Among all tested columns, C18 and EVO-C18 provided the best resolution for the most critical analyte pairs, del 3-O-glu/del 3-O-rut and cya 3-O-glu/cya 3-O-rut (Rs ≥ 2.2 and Rs ≥ 2.4, respectively). Although EVO-C18 achieved marginally higher resolution for the latter pair, the C18 column produced approximately 10% higher peak intensities, resulting indirectly in superior analytical sensitivity. Consequently, the C18 phase was selected for subsequent method validation. Beyond the four principal anthocyanins, eight additional minor anthocyanins were successfully resolved, and four exhibited partial coelution with each other. Column choice plays an important role in anthocyanin separation; however, as demonstrated in the present study, the developed gradient enables adequate separation performance across all seven tested stationary phases. Nevertheless, the content of acid in the mobile phase, e.g., formic acid, may have an even greater impact (crucial factor) than the stationary phase itself. Increasing formic acid concentration in the aqueous phase from 1% to 10% markedly enhanced resolution, reduced retention times, and increased peak intensities, thereby improving both efficiency and sensitivity (indirectly) [33]. The developed HPLC method demonstrated exceptional efficiency, achieving complete separation within only 11 min. This method is two minutes faster than the shortest previously reported HPLC protocol for black currant anthocyanin separation [19,34] and, moreover, enables the resolution of a higher number of minor anthocyanins compared to earlier rapid methodologies. The linear regression equations obtained for the calibration curves of four principal anthocyanins, along with determination coefficients (R2), limits of detection (LOD) and quantification (LOQ), linear range, retention time (RT), resolution (Rs), and standard error are presented in Table 1. The LOD and LOQ for all four principal anthocyanins were comparable, falling within the range of 0.127–0.198 ng and 0.420–0.654 ng, respectively.

Figure 1.

Anthocyanin separation chromatograms at the wavelength 520 nm of the extract obtained from the black currant cultivar ‘Ijunskaya Kondrashovoi’ using optimized chromatographic conditions on seven Kinetex column stationary phases—C18, F5, XB-C18, Phenyl-Hexyl, Biphenyl, EVO C18, and PFP.

Table 1.

Retention time of separated four anthocyanins (del 3-O-glu, del 3-O-rut, cya 3-O-glu, and cya 3-O-rut), linearity, limit of detection (LOD), limits of quantification (LOQ), and resolution of the developed method employing the Kinetex C18 column.

The optimized method for the Kinetex C18 column demonstrated good and comparable repeatability and reproducibility of RT of all four primary anthocyanins (% RSD 0.12–0.16) (Supplementary Materials). The precision, repeatability, and reproducibility were excellent for del 3-O-glu, del 3-O-rut, and cya 3-O-rut (% RSD 1) and good for cya 3-O-glu (% RSD 2–3) (Supplementary Materials). The developed method in the present study was more sensitive than reported earlier methods [23,33] due to rapid elution and very narrow peaks of anthocyanins. Another benefit of the validated method is its relatively low maximum operating pressure of 13.8 MPa.

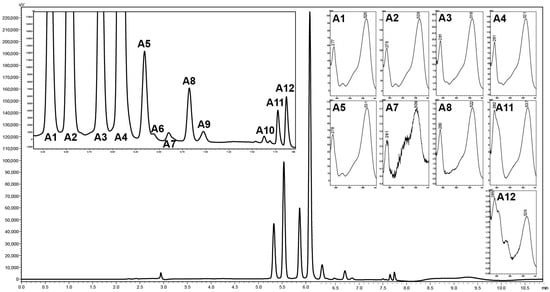

3.2. Anthocyanin Identification via LC-HRMS

Beyond the four main anthocyanins in black currant, eleven additional minor anthocyanins were detected, at least two of which exhibited partial co-elution with other anthocyanins (Figure 2). Among these, five minor anthocyanins with prominent peak areas were successfully identified using HRMS. Petunidin 3-O-rutinoside, pelargonidin 3-O-rutinoside, pelargonidin 3-O-glucoside, delphinidin 3-O-(6″-coumaroyl)-glucoside, and cyanidin 3-O-(6″-coumaroyl)-glucoside were identified as minor anthocyanins with the largest peak areas (Figure 2 and Supplementary Materials). The identification results were in full agreement with previously published data [21,22]. The consistent detection of primary and minor anthocyanins demonstrates that the developed method not only enables rapid chromatographic separation but also provides improved precision in the characterization of low-abundance anthocyanins. Earlier studies identified fifteen anthocyanins in black currant as early as 2002 [22] and confirmed them seventeen years later [21]. However, those analyses required considerably longer run times—25 and 45 min, respectively. Despite this, most subsequent research has focused on the four major anthocyanins and, at most, one to five minor compounds [19,23]. While the major anthocyanins of black currant are well-established, inconsistencies remain regarding the minor constituents. For example, delphinidin derivatives were reported by Obón et al. [35]; peonidin 3-O-rutinoside (peo 3-O-rut) and malvidin 3-O-rutinoside by Frøytlog et al. [36]; petunidin 3-O-(6″-coumaroyl)-glucoside and peonidin 3-O-(6″-coumaroyl)-glucoside by Gavrilova et al. [37] and Chen et al. [33]; and petunidin 3-O-rutinoside (pet 3-O-rut), peo 3-O-rut, delphinidin 3-O-(6″-coumaroyl)-glucoside (del 3-O-(6″), and cyanidin 3-O-(6″-coumaroyl)-glucoside (cya 3-O-(6″) by Nielsen et al. [34], and other studies have identified Peo 3-O-rut, pelargonidin 3-O-rutinoside (pel 3-O-rut), delphinidin 3-O-xyloside, del 3-O-(6″), and cya 3-O-(6″) such as Gacnik et al. [38]. In the present study, del 3-O-(6″) and cya 3-O-(6″) were consistently detected across all 123 genotypes, suggesting that their absence in some prior reports likely reflects methodological limitations—such as low detection sensitivity, absence of authentic standards, insufficient chromatographic run times, or suboptimal mobile phase composition.

Figure 2.

Chromatogram of anthocyanin isolation at the wavelength 520 nm from the extract of black currant cultivar ‘Ijunskaya Kondrashovoi’ using optimized chromatographic conditions on the Kinetex C18 column and UV spectra of known anthocyanins (identified by HRMS—Supplementary Materials). A1, del 3-O-glu; A2, del 3-O-rut; A3, cya 3-O-glu; A4, cya 3-O-rut; A5, pet 3-O-rut; A6, unknown anthocyanin–UA6; A7, pel 3-O-rut; A8, peo 3-O-rut; A9, unknown anthocyanin–UA9; A10, unknown anthocyanin–UA10; A11, del 3-O-(6″); A12, cya 3-O-(6″).

3.3. Laboratory Factors Influencing Anthocyanin Quantification in Black Currant

This section aimed to minimize solvent consumption, reduce the labor and time required for sample preparation, and evaluate the effects of homogenization procedures, berry size, and genetic variability (123 genotypes) on the measured anthocyanin content in black currant.

3.3.1. Effect of Solvent Type and Concentration

Although solvent and solvent concentration significantly affected almost all anthocyanin content in the extract (p < 0.01), the exception being UA6 (p > 0.05 for solvent, and p = 0.01 for concentration), it could not identify differences between sample groups for most anthocyanins (Figure 3). Within the main anthocyanin and total anthocyanin content, the choice of solvent had a more significant effect (p < 0.001) than alcohol concentration (p = 0.002). The highest total anthocyanin extraction was achieved using 50% ethanol. There was no linear regression depending on methanol concentration (R2 = 0.0156), and higher ethanol concentration resulted in reduced anthocyanin content in the extract (y = −18.088x + 522.29, R2 = 0.8301). Previous studies utilizing aqueous ethanol as an extraction solvent often lacked systematic optimization of ethanol concentration. Some employed only 95% ethanol either without acidification [3] or with 0.1 M HCl [28], while others used 50% ethanol adjusted to pH 1.5 with HCl [30]. Comparative evaluations across different concentrations—such as 30%, 50%, and 70% [27], or 40%, 60%, and 96% [18]—identified 30% or 50% and 60% ethanol, respectively, as the most efficient solvents depending on the extraction technique and operational parameters. In another study, concentrations ranging from 35% to 95% ethanol were investigated, and 67% ethanol was reported as optimal, although extraction conditions such as temperature and solvent-to-sample ratio varied among tested variants [39]. Due to applied different methodologies of extraction, the outcomes of these studies cannot be directly compared. Nonetheless, despite the diversity of approaches, the optimal ethanol concentration for anthocyanin extraction from black currant generally converges around 50%. Importantly, acidification of solvents for anthocyanin extraction substantially enhance their recovery from black currant pomace [31].

Figure 3.

Effect of solvent choice and concentration on anthocyanin content in the extract of black currants. Letters denote statistically homogenous groups (p > 0.05).

3.3.2. Effect of Acid Type and Temperature of Extraction

Hydrochloric acid is the most frequently employed acid in anthocyanin extraction protocols, primarily because it improves both extraction efficiency and pigment stability [21,26,28,30]. Nevertheless, its corrosive nature and associated health and instrumental risks motivate the search for less hazardous alternatives. For this reason, we compared 0.36 N HCl with 1% formic acid in 50% aqueous ethanol (v/v) at 60 °C. Using anthocyanin recovery with 0.36 N HCl as the 100% reference, extraction with 1% formic acid was approximately 7% less effective in terms of black currant anthocyanin extraction and/or stabilization (Supplementary Materials). Given that higher temperatures are often assumed to adversely affect anthocyanin stability, we then defined 100% extraction efficiency and/or stability as that achieved at the lowest tested temperature (30 °C) of extraction using 50% ethanol (v/v) acidified with 0.36 N HCl. Relative to this baseline, we observed slight increases in measured anthocyanin content at 40 °C and 50 °C and a slight decrease at 60 °C. However, all of these changes were within approximately 0.5%, and none reached statistical significance (Supplementary Materials). These results indicate that, when using 50% ethanol (v/v) with 0.36 N HCl, the effective extraction efficiency and stability of black currant anthocyanins remain essentially constant between 30 and 60 °C. From a purely energetic standpoint, such equivalence would argue in favor of operating at 30 °C. It is important to emphasize, however, that in our experiments the fruits were first processed into a fine powder by cryogenic grinding. This extensive disruption of cellular structures greatly facilitates solvent penetration and solute release. Consequently, although the selection of extraction temperature within the 30–60 °C range may be flexible in this specific, finely milled matrix, the choice of acid is less equivocal. Our data clearly support the use of 0.36 N HCl over 1% formic acid for black currant anthocyanin extraction, as it aids their superior recovery/stability.

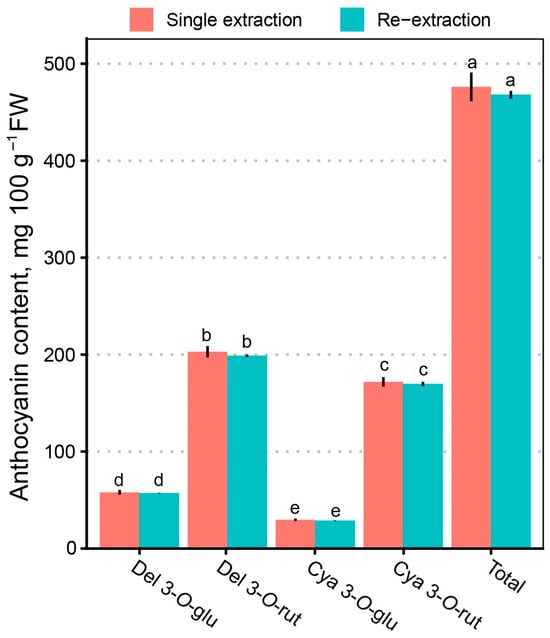

3.3.3. Effect of Re-Extraction

There were no statistically significant or marginally significant differences (p > 0.05) between any individual or total anthocyanin content of the single-extraction and re-extracted extracts (Figure 4). According to our results, the re-extraction may be skipped for analytical purposes to save solvent and time. The direct extraction yielded a total anthocyanin content of 476.07 (±14.82) mg 100 g−1 FW with a coefficient of variation (CV) of 1.46, while the repeated extraction provided a slightly lower but comparable yield of 458.89 (±3.82) mg 100 g−1 FW with a CV of 0.17. Notably, the repeated extraction method exhibited lower variability and had higher reproducibility. These findings are consistent with reports in the scientific literature, which demonstrate that optimized single-step extraction methods can achieve anthocyanin yields comparable to those obtained through multiple extraction cycles, particularly in berry matrices.

Figure 4.

Differences in the anthocyanin content in the extract of black currants depending on protocol—single extraction vs. re-extraction. Letters denote statistically homogenous groups (p > 0.05).

Previous studies emphasize that anthocyanins are thermolabile and photolabile compounds sensitive to pH, temperature, and light exposure. Consequently, shorter and simpler extraction procedures, such as direct extraction, reduce the risk of anthocyanin degradation while maintaining high extraction efficiency. In contrast, repeated extractions often lead to higher solvent usage and longer processing times without a substantial improvement in yield [19,40,41,42]. The slightly higher variability observed with direct extraction remains acceptable for routine analyses or screening studies, where efficiency and throughput are prioritized. These findings align with previous research supporting optimized single-step solvent extraction methods as effective and sustainable solutions for anthocyanin analysis in fruit matrices [19,40].

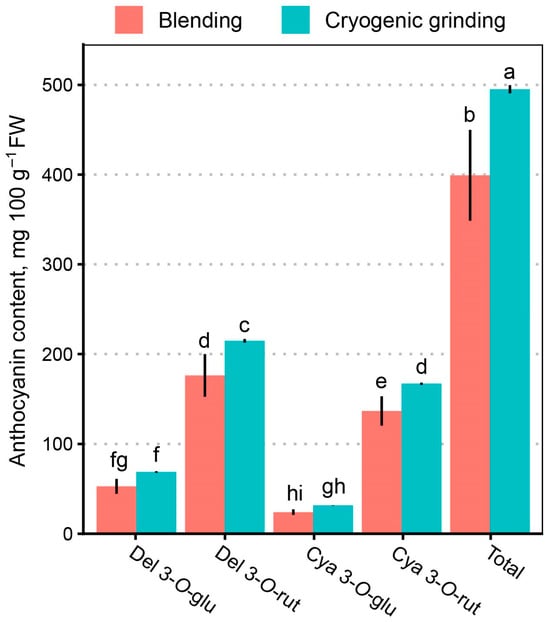

3.3.4. Effect of Sample Homogenization

According to MANOVA results, liquid nitrogen pre-treatment to the preparation protocol affected (p < 0.05) all anthocyanin concentration in the final extract, except for del 3-O-(6″) (p = 0.53). The post hoc test identified statistically significant differences between differently treated samples del 3-O-glu, del 3-O-rut, cya 3-O-glu, and cya 3-O-rut and total anthocyanin contents (Figure 5). The highest concentration increase was observed for peo 3-O-rut (167%), while the concentration of the rest increased by 26.3–64.6%, compared to blending-only extracts. The total anthocyanin concentration increased by 25.6%. Cryogenic treatment of black currant berries with liquid nitrogen, followed by cryogrinding, produces an ultrafine powder in which the cellular structures are completely disrupted. This structural breakdown significantly increases the effective surface area available for solvent penetration, thereby enhancing the extraction efficiency of secondary metabolites, including anthocyanins. The influence of particle size on anthocyanin extractability has been well documented—for instance, in purple wheat, extraction efficiency is inversely proportional to particle size [43]. Similarly, the application of cryogrinding has been demonstrated to markedly improve anthocyanin recovery from black chokeberry (Aronia melanocarpa) pomace [32]. Cryogenic processing distinctly underscores the importance of mechanical disruption for achieving maximal anthocyanin extraction from black currant fruits.

Figure 5.

Effect of pre-treatment—(blending vs. cryogenic grinding prior to blending)—on anthocyanin content in the extract of black currants. Letters denote statistically homogenous groups (p > 0.05).

3.4. Effect of Berry Size and Genotype

3.4.1. Berry Size Fraction

The mean, standard deviation and range of concentrations for individual anthocyanins in 123 genotypes were as follows: del 3-O-glu 59.0 ± 25.0, 5.8–146.9 is 25.5 times; del 3-O-rut 208.9 ± 69.6, 15.5–483.9; cya 3-O-glu 28.5 ± 13.5, 6.7–100.4; cya 3-O-rut 167.4 ± 60.8, 46.8–413.6; pet 3-O-rut 3.1 ± 3.5, 0.2–37.5; pel 3-O-rut 0.6 ± 0.4, 0.1–2.7; peo 3-O-rut 1.6 ± 1.3, 0.0–7.3; del 3-O-(6″) 3.0 ± 2.2, 0.1–14.8; cya 3-O-(6″) 1.5 ± 1.3, 0.1–8.1; and total 475.9 ± 129.7, 82.7–1020.7 mg 100 g−1 FW (Supplementary Materials).

Overall, the differences between the lowest and highest concentrations of individual and total anthocyanins ranged from one to two orders of magnitude. The variation was the lowest for cya 3-O-rut, which showed nearly a 9-fold difference, and for total anthocyanin content, which varied more than 12-fold. Among the major anthocyanins, del 3-O-rut exhibited the greatest variation, with a 31-fold difference between the lowest and highest levels. A broader range of concentrations was generally observed for delphinidin glycosides compared to cyanidin glycosides. Remarkably, pet 3-O-rut demonstrated the highest degree of variability, with a 203-fold difference between its minimum and maximum concentrations. Anthocyanin content distribution in berry fractions is depicted in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Anthocyanin proportion boxplot and distribution in small and large black currant berry fractions, % of total. Black points represent outlier values.

Notably, across all identified anthocyanin subgroups distinguished by their respective anthocyanidins (cyanidin, delphinidin, pelargonidin, peonidin, and petunidin), the highest concentrations were consistently observed for rutinoside-conjugated derivatives. This finding aligns with previous reports, where anthocyanins bearing rutinoside as the glycosidic residue exhibited dominant peak areas in chromatographic profiles in comparison to glucoside-conjugated derivatives [22].

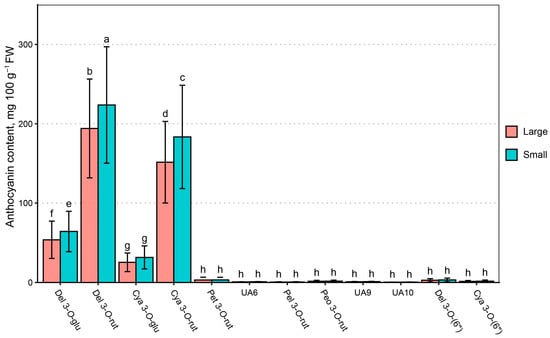

While multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) showed very significant differences between the anthocyanin contents of berries of different size and genotype (p < 0.05), the differences are less significant once the covariance of genotype and berry fraction is accounted for (Figure 7)—the post hoc test only identified significant differences between del 3-O-glu, del 3-O-rut, and cya 3-O-rut contents in different berry fractions. While cya 3-O-glu content was higher than minor anthocyanin, there were no statistically significant differences between cya 3-O-glu or minor anthocyanin contents in large and small berries (p > 0.05). No statistically significant differences were observed between the proportion of individual anthocyanins (p > 0.05).

Figure 7.

MANCOVA results for large- and small-berry fractions. Data are presented as means ± standard deviation within black currant berry fractions, mg 100 g−1 FW. Letters denote statistically homogenous groups (p > 0.05).

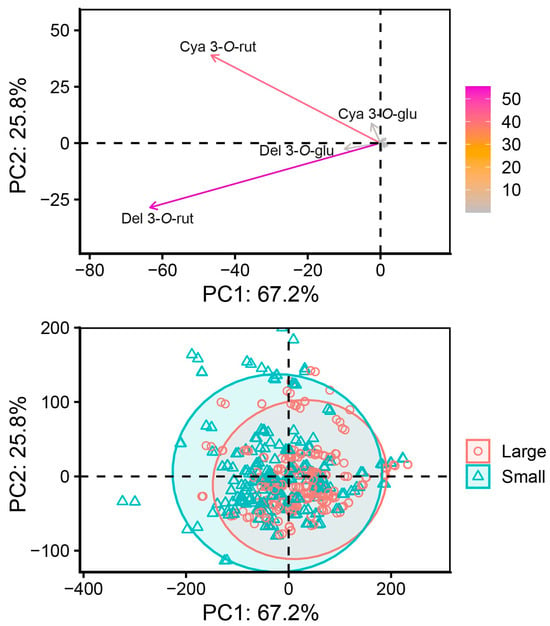

Principal component analysis (PCA) identified principal components (PC) PC1 and PC2, which explain 67.2% and 15.8% of total variance for a total of 93.0% explained variance. The main contributors to PC scores were del 3-O-rut and cya 3-O-rut. Of these, del 3-O-rut was negatively associated with PC1 (−0.80) and PC2 (−0.58), while cya 3-O-rut was negatively associated with PC1 (−0.59) and positively associated with PC2 (0.79). While the individual datapoint scores overlapped significantly, the ellipse of the small currant berry datapoints is bigger (Figure 8). While non-hierarchal cluster analysis was performed and cluster analysis identified two groups of clusters, the between-cluster sum of squares was 39.9% of total sum of squares, and the proportion and distribution of small- and large-berry datapoints was similar between the two clusters, with significant overlap of clusters.

Figure 8.

PCA variable (top) and datapoint (bottom) plot based on black currant berry fraction size.

Since anthocyanin content increases during ripening [38], it might be intuitively expected that smaller black currant berries represent a lower ripening stage and therefore contain less anthocyanin compared to larger berries. However, this assumption was supported in only 19 genotypes, in which the larger berries exhibited higher anthocyanin concentrations. This could indeed reflect a lower degree of ripeness in the smaller berries of these particular genotypes. In contrast, for 104 genotypes—accounting for approximately 85% of all those examined—the opposite trend was observed, with smaller berries containing higher anthocyanin levels. This phenomenon can be rationalized by geometric considerations: because anthocyanin pigments are predominantly localized in the berry peel [44], the total surface area of one kilogram of smaller berries is greater than that of the same mass of larger berries, thereby providing a proportionally larger anthocyanin-bearing surface. The ratio of anthocyanin content between small and large berries ranged from 1.01 to 1.94, with an average of 1.27 ± 0.21, corresponding to approximately 27% higher anthocyanin levels in smaller black currant berries. Conversely, in the minority of genotypes where larger berries contained more anthocyanins, the ratio ranged from 1.07 to 1.51, averaging 1.21 ± 0.15—indicating about 21% higher anthocyanin content in larger berries of those genotypes (Supplementary Materials). However, it should be emphasized that berry size is not an independent variable, as genetic background strongly covaries with berry morphology.

Of the four main anthocyanins, significant Spearman rank correlations were observed between del 3-O-glu and cya 3-O-glu content (ρ = 0.62 and 0.52 in large and small berries, and ρ = 0.58 across all datapoints) and between cya 3-O-glu and cya 3-O-rut content (ρ = 0.48 and 0.51 in large and small berries, and ρ = 0.53 across all datapoints). Correlation was much stronger between anthocyanin proportions (percentage of anthocyanin in total anthocyanin content)—between del 3-O-glu and cya 3-O-glu (ρ = 0.52 and 0.48 in large and small berries, respectively, and ρ = 0.5 across all datapoints), del 3-O-glu and cya 3-O-rut (ρ = −0.5 in large and small berries, and across all datapoints), del 3-O-rut and cya 3-O-glu (ρ = −0.86 and −0.87 in large and small berries, respectively, and ρ = −0.87 across all datapoints), and del 3-O-rut and cya 3-O-rut (ρ = −0.67 and −0.68 in large and small berries, respectively, and ρ = −0.68 across all datapoints).

3.4.2. Genotype

Across all variety means, none of the anthocyanins had strong linear regression to the mean berry size (R2 < 0.2), and there were no strong correlations to mean berry size (ρ < 0.4). Upon categorizing varieties as having small or large berries (having below- or above-dataset mean berry size, respectively), anthocyanin content followed an opposite trend—larger-berry genotypes had higher anthocyanin content. While genotype ‘860-101’ contained the lowest levels of most individual and total anthocyanins, except for cya 3-O-glu, which was lowest in ‘Zabava’, the highest concentrations were distributed among several genotypes. Specifically, the genotypes with the maximum contents of each anthocyanin were as follows: del 3-O-glu—‘6r.106’; del 3-O-rut and total—‘Ben Gairn’; cya 3-O-glu—‘11r.106’; cya 3-O-rut—‘2r.120’; pet 3-O-rut and peo 3-O-rut—‘Black Naple’s x 4+6+7’; pel 3-O-rut—‘13r.7 no B’; and del 3-O-(6″) and cya 3-O-(6″)—‘Kriviai’ (Supplementary Materials). Anthocyanin content distribution in analyzed genotypes in visualized in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Mean anthocyanin content distribution in genotypes with different black currant berry sizes, mg 100 g−1 FW. Black points represent outlier values.

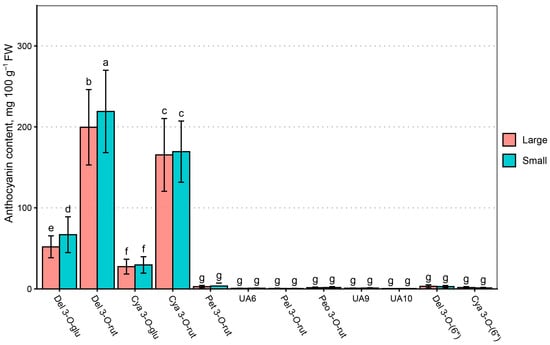

Anthocyanin contents were significantly affected by the genotype mean berry size, but genotypes with larger berries had higher anthocyanin contents. MANOVA identified statistically significant differences between del 3-O-glu (p < 0.001), del 3-O-rut (p < 0.05), and total anthocyanin content (p < 0.01), while main anthocyanin sum was similar between groups (p > 0.5). Significant differences were identified between UA6 (p < 0.001), UA9 (p < 0.001), and cya 3-O-(6″) (p < 0.01) contents. However, the post hoc test only identified statistically significant differences between individual anthocyanin, del 3-O-glu, and del 3-O-rut content (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

MANCOVA results for anthocyanin content in black currant by genotype berry size. Data are presented as means ± standard deviation within group, mg 100 g−1 FW. Letters denote statistically homogenous groups (p > 0.05).

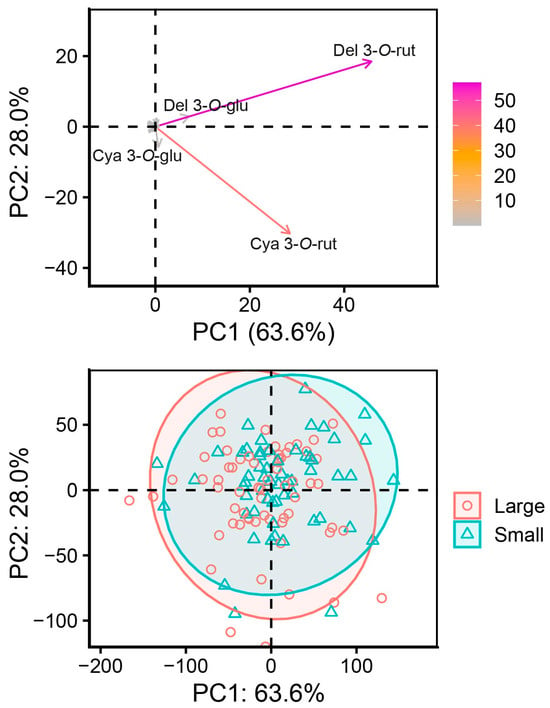

PCA identified PC1 and PC2, which explained 63.6% and 28.0% of total variance for a total of 91.6% explained variance. Like with berry fractions, del 3-O-rut and cya 3-O-rut were the main contributors. Del 3-O-rut was positively associated with PC1 (0.84) and PC2 (0.51), and cya 3-O-rut was positively associated with PC1 (0.52) but negatively associated with PC2 (−0.84). PCA results are visualized in Figure 11. The separation between large- and small-berry genotypes was lower than between-berry fractions in Figure 11. The dataset used for genotype comparison was not suitable for cluster analysis—optimal cluster number could not be identified.

Figure 11.

PCA variable (top) and datapoint (bottom) plot based on genotype berry size.

Average berry size had very weak correlation with total anthocyanin content (ρ = −0.28, p < 0.01) and had very weak negative correlation with two of the main anthocyanins: del 3-O-glu (ρ = −0.37, p < 0.01) and del 3-O-rut (ρ = −0.24, p < 0.01). It appears that berry size of the currant plant has the strongest effect on berry anthocyanins, and genotype is a slightly weaker factor. Moreover, the relationship between berry size and individual and total anthocyanin contents is not linear. The trends within and between genotypes may be explained by physiological differences (predisposition towards naturally producing more anthocyanins), berry ripeness, berry skin thickness, and a variety of factors within the fruit influencing anthocyanin extraction. Higher content of anthocyanins in small-sized berries and opposite in bigger berries has been reported in wine grape (Vitis vinifera) [45], and strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa) [46].

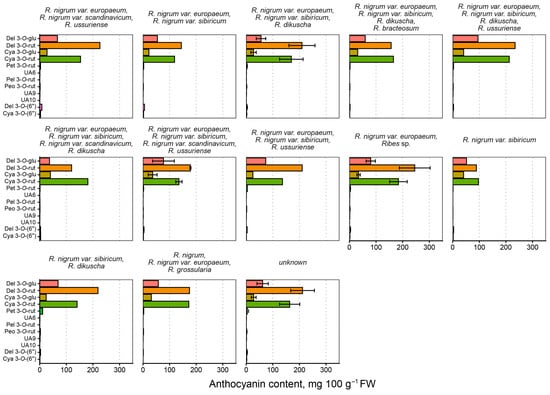

The analyzed genotypes can be grouped to some degree based on their ancestry (species and varieties used in breeding). While “black currant” generally refers to R. nigrum, several varieties and other species have been used in plant breeding, as they are in a number of fruit crops. These included R. nigrum varieties eurapeum, sibiricum, scandinavicum, and R. ussuriense (synonym of R. procumbens, or Korean currant), R. dikuscha (Dikusha currant), R. bracteosum (stink currant), and R. grossularia (synonym of R. uva-crispa, or gooseberry). The mean anthocyanin contents are visualized in Figure 12. The make-up of anthocyanins is quite similar between the different known ancestries, but detailed histories are not available for any of the tested genotypes.

Figure 12.

Mean anthocyanin content (mg 100 g−1 FW) in black currant in the specific crossbreeds. Bar color denotes anthocyanin, as shown in the left-most panel.

Enhancement of fruit quality traits remains a major challenge owing to the intricate genetic and regulatory mechanisms underlying their expression, yet it constitutes a key objective of ongoing and future breeding programs. The present findings highlight the multifactorial impact of both genetic background and environmental conditions on the sensory attributes and nutritional composition of the berries [47].

4. Conclusions

The present study establishes a rapid, robust, and comprehensive HPLC method for the analysis of four major and several minor anthocyanins in black currant within only 11 min. The validated method was successfully applied to 123 black currant genotypes, confirming its suitability for large-scale screening studies. Among the tested solvents, 50% (v/v) ethanol, acidified with 0.36 N HCl, was found to be more efficient than methanol-based mixtures for anthocyanin extraction. Cryogenic freezing prior to grinding markedly increased anthocyanin yield, while re-extraction did not improve anthocyanin content in the aqua–ethanolic extract. Smaller berries consistently exhibited higher anthocyanin concentrations than larger ones within genotypes. Similarly, genotypes with smaller-than-average berries (relative to the dataset) had higher anthocyanin contents as well. However, there was no distinct difference between the anthocyanin profiles of the berry fractions or genotype subsets.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app16010114/s1.

Author Contributions

I.M. (Inga Mišina): Resources, Formal Analysis; E.B.: Resources, Formal Analysis; K.D.: Resources, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Data Curation; I.M. (Ieva Miķelsone): Resources, Formal Analysis, Investigation; E.S.: Resources, Formal Analysis, Investigation; D.L.: Investigation, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review and Editing, Visualization; S.S.: Data Curation, Supervision; D.S.: Supervision, Funding Acquisition, Project Administration; I.P.: Investigation, Formal Analysis; P.G.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Investigation, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review and Editing, Visualization, Supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the project “Research-based solutions for sustainable agri-food system addressed to the European Green Deal” (GreenAgroRes), funded by the Latvian Council of Science under the National Research Programme “Sustainable Development of the Agricultural Sector for the Benefit of Society” (VPP-ZM-VRIIILA-2024/1-0002).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available in the Supplementary Materials and from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

Thanks go to the Latvian Council of Science for project funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

Cya 3-O-(6″), cyaniding 3-O-(6″-coumaroyl)-glucoside; Cya 3-O-glu, cyanidin 3-O-glucoside; Cya 3-O-rut, cyanidin 3-O-rutinoside; CV, coefficient of variation; Del 3-O-(6″), delphinidin 3-O-(6″-coumaroyl)-glucoside; Del 3-O-glu, delphinidin 3-O-glucoside; Del 3-O-rut, delphinidin 3-O-rutinoside; FW, fresh weight; HRMS, high-resolution mass spectrometry; LOD, limit of detection; LOQ, limit of quantification; Pel 3-O-rut, pelargonidin 3-O-rutinoside; Peo 3-O-rut, peonidin 3-O-rutinoside; Pet 3-O-rut, petunidin 3-O-rutinoside; PFP and F5, pentafluorophenylpropyl phases; S/N, signal-to-noise ratio; Rs, resolution; RSD, relative standard deviation; RT, retention time; SPP, superficially porous particles; UA6, 9, 10, unknown anthocyanin.

References

- Nour, V.; Trandafir, I.; Ionica, M.E. Ascorbic acid, anthocyanins, organic acids and mineral content of some black and red currant cultivars. Fruits 2011, 66, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattila, P.H.; Hellström, J.; Karhu, S.; Pihlava, J.-M.; Veteläinen, M. High variability in flavonoid contents and composition between different North-European currant (Ribes spp.) varieties. Food Chem. 2016, 204, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razgonova, M.P.; Nawaz, M.A.; Sabitov, A.S.; Golokhvast, K.S. Genus Ribes: Ribes aureum, Ribes pauciflorum, Ribes triste, and Ribes dikuscha—Comparative mass spectrometric study of polyphenolic composition and other bioactive constituents. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ejaz, A.; Waliat, S.; Afzaal, M.; Saeed, F.; Ahmad, A.; Din, A.; Ateeq, H.; Asghar, A.; Shah, Y.A.; Rafi, A. Biological activities, therapeutic potential, and pharmacological aspects of blackcurrants (Ribes nigrum L): A comprehensive review. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11, 5799–5817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gopalan, A.; Reuben, S.C.; Ahmed, S.; Darvesh, A.S.; Hohmann, J.; Bishayee, A. The health benefits of blackcurrants. Food Funct. 2012, 3, 795–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortez, R.E.; Gonzalez de Mejia, E. Blackcurrants (Ribes nigrum): A review on chemistry, processing, and health benefits. J. Food Sci. 2019, 84, 2387–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, A.M.; Zhou, R.; Austermann, K.; Králová, D.; Serra, G.; Ibrahim, I.S.; Corona, G.; Bergillos-Meca, T.; Aboufarrag, H.; Kroon, P.A. Acute effects of an anthocyanin-rich blackcurrant beverage on markers of cardiovascular disease risk in healthy adults: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. J. Nutr. 2025, 155, 2275–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Acosta, M.L.; Smith, L.; Miller, R.J.; McCarthy, D.I.; Farrimond, J.A.; Hall, W.L. Drinks containing anthocyanin-rich blackcurrant extract decrease postprandial blood glucose, insulin and incretin concentrations. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2016, 38, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomiwes, D.; Kanon, A.P.; Walker, E.G.; Ngametua, N.; Cooney, J.M.; Jensen, D.A.; Hedderley, D.; Lo, K. A blackcurrant powder supplement enriched with L-theanine and pine bark extract improves sleep quality in healthy older adults: Results from placebo controlled crossover study. J. Funct. Foods 2025, 127, 106768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali Redha, A.; Anusha Siddiqui, S.; Zare, R.; Spadaccini, D.; Guazzotti, S.; Feng, X.; Bahmid, N.A.; Wu, Y.S.; Ozeer, F.Z.; Aluko, R.E. Blackcurrants: A nutrient-rich source for the development of functional foods for improved athletic performance. Food Rev. Int. 2024, 40, 135–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moročko-Bičevska, I.; Stalažs, A.; Lācis, G.; Laugale, V.; Baļķe, I.; Zuļģe, N.; Strautiņa, S. Cecidophyopsis mites and blackcurrant reversion virus on Ribes hosts: Current scientific progress and knowledge gaps. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2022, 180, 26–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masny, A.; Pluta, S.; Seliga, Ł. Breeding value of selected blackcurrant (Ribes nigrum L.) genotypes for early-age fruit yield and its quality. Euphytica 2018, 214, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lācis, G.; Kārkliņa, K.; Bartulsons, T.; Stalažs, A.; Jundzis, M.; Baļķe, I.; Ruņģis, D.; Strautiņa, S. Genetic structure of a Ribes genetic resource collection: Inter-and intra-specific diversity revealed by chloroplast DNA simple sequence repeats (cpSSRs). Sci. Hortic. 2022, 304, 111285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanys, V.; Bendokas, V.; Rugienius, R.; Sasnauskas, A.; Frercks, B.; Mažeikienė, I.; Šikšnianas, T. Management of anthocyanin amount and composition in genus Ribes using interspecific hybridisation. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 247, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anisimovienė, N.; Jankauskienė, J.; Jodinskienė, M.; Bendokas, V.; Stanys, V.; Šikšnianas, T. Phenolics, antioxidative activity and characterization of anthocyanins in berries of blackcurrant interspecific hybrids. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2013, 60, 767–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.M. Resistance to black currant leaf spot (Pseudopeziza ribis) in crosses between Ribes dikuscha and R. nigrum. Euphytica 1972, 21, 510–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djordjević, B.; Rakonjac, V.; Akšić, M.F.; Šavikin, K.; Vulić, T. Pomological and biochemical characterization of European currant berry (Ribes sp.) cultivars. Sci. Hortic. 2014, 165, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nour, V.; Stampar, F.; Veberic, R.; Jakopic, J. Anthocyanins profile, total phenolics and antioxidant activity of black currant ethanolic extracts as influenced by genotype and ethanol concentration. Food Chem. 2013, 141, 961–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šimerdová, B.; Bobríková, M.; Lhotská, I.; Kaplan, J.; Křenová, A.; Šatínský, D. Evaluation of anthocyanin profiles in various blackcurrant cultivars over a three-year period using a fast HPLC-DAD method. Foods 2021, 10, 1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Gu, L.; Prior, R.L.; McKay, S. Characterization of anthocyanins and proanthocyanidins in some cultivars of Ribes, Aronia, and Sambucus and their antioxidant capacity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 7846–7856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Laaksonen, O.; Haikonen, H.; Vanag, A.; Ejaz, H.; Linderborg, K.; Karhu, S.; Yang, B. Compositional diversity among blackcurrant (Ribes nigrum) cultivars originating from European countries. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 5621–5633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slimestad, R.; Solheim, H. Anthocyanins from black currants (Ribes nigrum L.). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 3228–3231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawawi, N.I.M.; Khushairi, N.A.A.A.; Ijod, G.; Azman, E.M. Extraction of anthocyanins and other phenolics from dried blackcurrant (Ribes nigrum L.) pomace via ultrasonication. Sustain. Chem. Environ. 2025, 9, 100208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachtan-Janicka, J.; Ponder, A.; Hallmann, E. The effect of organic and conventional cultivations on antioxidants content in blackcurrant (Ribes nigrum L.) species. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordonaba, J.G.; Terry, L.A. Biochemical profiling and chemometric analysis of seventeen UK-grown black currant cultivars. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 7422–7430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikas, A.; Rätsep, R.; Kaldmäe, H.; Aluvee, A.; Libek, A.-V. Comparison of polyphenols and anthocyanin content of different blackcurrant (Ribes nigrum L.) cultivars at the Polli Horticultural Research Centre in Estonia. Agron. Res. 2020, 18, 2715–2726. [Google Scholar]

- Milić, A.; Daničić, T.; Tepić Horecki, A.; Šumić, Z.; Teslić, N.; Bursać Kovačević, D.; Putnik, P.; Pavlić, B. Sustainable extractions for maximizing content of antioxidant phytochemicals from black and red currants. Foods 2022, 11, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubinskiene, M.; Viskelis, P.; Jasutiene, I.; Viskeliene, R.; Bobinas, C. Impact of various factors on the composition and stability of black currant anthocyanins. Food Res. Int. 2005, 38, 867–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Park, Y.; Lee, S.; Kim, D.-O. Extraction, identification, and health benefits of anthocyanins in blackcurrants (Ribes nigrum L.). Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruszewski, B.; Boselli, E. Blackcurrant pomace as a rich source of anthocyanins: Ultrasound-assisted extraction under different parameters. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azman, E.M.; Nor, N.D.M.; Charalampopoulos, D.; Chatzifragkou, A. Effect of acidified water on phenolic profile and antioxidant activity of dried blackcurrant (Ribes nigrum L.) pomace extracts. LWT 2022, 154, 112733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repajić, M.; Zorić, M.; Magnabosca, I.; Pedisić, S.; Dragović-Uzelac, V.; Elez Garofulić, I. Bioactive power of black chokeberry pomace as affected by advanced extraction techniques and cryogrinding. Molecules 2025, 30, 3383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Parker, J.; Krueger, C.G.; Shanmuganayagam, D.; Reed, J.D. Validation of HPLC assay for the identification and quantification of anthocyanins in black currants. Anal. Methods 2014, 6, 8141–8147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, I.L.F.; Haren, G.R.; Magnussen, E.L.; Dragsted, L.O.; Rasmussen, S.E. Quantification of anthocyanins in commercial black currant juices by simple high-performance liquid chromatography. Investigation of their pH stability and antioxidative potency. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 5861–5866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obón, J.M.; Díaz-García, M.C.; Castellar, M.R. Red fruit juice quality and authenticity control by HPLC. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2011, 24, 760–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frøytlog, C.; Slimestad, R.; Andersen, Ø.M. Combination of chromatographic techniques for the preparative isolation of anthocyanins—Applied on blackcurrant (Ribes nigrum) fruits. J. Chromatogr. A 1998, 825, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavrilova, V.; Kajdzanoska, M.; Gjamovski, V.; Stefova, M. Separation, characterization and quantification of phenolic compounds in blueberries and red and black currants by HPLC−DAD−ESI-MSn. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 4009–4018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gacnik, S.; Veberic, R.; Hudina, M.; Mikulic-Petkovsek, M. Changes in chemical composition of red and black currant fruits and leaves during berry ripening. Int. J. Fruit Sci. 2024, 24, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacace, J.E.; Mazza, G. Optimization of extraction of anthocyanins from black currants with aqueous ethanol. J. Food Sci. 2003, 68, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tena, N.; Asuero, A.G. Up-to-date analysis of the extraction methods for anthocyanins: Principles of the techniques, optimization, technical progress, and industrial application. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzazadeh, N.; Bagheri, H.; Mirzazadeh, M.; Soleimanimehr, S.; Rasi, F.; Akhavan-Mahdavi, S. Comparison of different green extraction methods used for the extraction of anthocyanin from red onion skin. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 12, 7347–7357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Han, Y.; Han, B.; Qi, X.; Cai, X.; Ge, S.; Xue, H. Extraction and purification of anthocyanins: A review. J. Agric. Food Res. 2022, 8, 100306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Qi, Z.; Li, J.; Gao, J.; Xie, Y.; Henry, C.J.; Zhou, W. Role of superfine grinding in purple-whole-wheat flour. Part I: Impacts of size reduction on anthocyanin profile, physicochemical and antioxidant properties. LWT 2024, 197, 115940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pocevičienė, I.; Jūrienė, L.; Pukalskienė, M.; Baranauskienė, R.; Venskutonis, P.R. Supercritical CO2 separation of lipids from mechanically pre-fractionated black currant pomace: Chemical composition, bioactivities and application perspectives. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 373, 133641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roby, G.; Harbertson, J.F.; Adams, D.A.; Matthews, M.A. Berry size and vine water deficits as factors in winegrape composition: Anthocyanins and tannins. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2004, 10, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simkova, K.; Veberic, R.; Hudina, M.; Grohar, M.C.; Ivancic, T.; Smrke, T.; Pelacci, M.; Jakopic, J. Berry size and weight as factors influencing the chemical composition of strawberry fruit. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2023, 123, 105509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pott, D.M.; Durán-Soria, S.; Allwood, J.W.; Pont, S.; Gordon, S.L.; Jennings, N.; Austin, C.; Stewart, D.; Brennan, R.M.; Masny, A. Dissecting the impact of environment, season and genotype on blackcurrant fruit quality traits. Food Chem. 2023, 402, 134360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.