Abstract

Common wheat (Triticum aestivum ssp. vulgare) is one of the three basic cereal crops worldwide that plays a key role in global food security. A key factor affecting the yield and traits of common wheat is an adequate nitrogen supply. Improving the efficiency of soil nitrogen use can be achieved through the application of appropriate mineral fertilizers and the proper selection of cultivars. The aim of this study was to determine the impact of residual nitrogen (Nres) after maize cultivation (the preceding crop) on the yield and chemical composition of winter and spring wheat grain. It was shown that both the variety selection and the type of nitrogen carrier had a significant impact on the characteristics related to wheat yield and grain quality. The most stable effect of the type of nitrogen, regardless of the type of corn variety, was recorded for ammonium nitrate with N-Lock. The average yield was approximately 6.1 t ha−1. With the exception of the variant with N-Lock, the most progressive reaction to the type of fertilizer occurred in the stand with a three-line corn hybrid (TC, stay green). The advantage of this corn variety as a winter wheat forecrop results from the value of the site in a site without nitrogen. In the nitrogen control, the increase in yield compared to the single corn hybrid (SC) was 14%. However, in the U + N-Lock variant, it was 17%, and SG Stabilo as much as 32%. The increase in the weight of 1000 wheat grains in the stands after the SC and TC hybrid compared to stay green + roots power indicates a compensatory mechanism that became visible in the grain filling phase. Current challenges in agriculture caused by population growth and the need to ensure sufficient food production require greater awareness and knowledge regarding improved nitrogen management, including recognizing the role of residual nitrogen remaining in the soil after the preceding crop. A major advantage of slow-release fertilizers is that the nutrient (N) is released in response to the dynamic demand of the crop. This, on the one hand, increases grain yield and, on the other, does not negatively impact the agrosystem (eutrophication).

1. Introduction

Common wheat (Triticum aestivum ssp. vulgare), alongside maize and rice, is one of the three most important cultivated crops worldwide. It provides the main source of nutrition for 35% of the global population and is used to produce staple food products such as flour, bread, biscuits, or pasta, as well as for brewing beer and producing biofuel [1]. Additionally, common wheat, due to its chemical composition, is a good source of dietary fiber, phenolic acids, and resistant starch, which consists of starch and its degradation products that resist digestion and absorption in the small intestine [2]. Wheat provides approximately 20% of calories and over 25% of protein. It is estimated that due to the global population rising to nearly 10 billion by 2050, the demand for this crop will also increase significantly, by approximately 60% [3]. For this reason, global wheat production in 2022 reached 778 million tons, with cultivation area of 220 million hectares [4].

Nitrogen fertilization is one of the primary factors influencing both the quantity and quality of winter and spring wheat grain yield [5,6]. Approximately 67.84 million tons of nitrogen are applied annually in global crop production. Without this nutrient, enabling higher crop yields, nearly half of the global population might not survive due to insufficient food production [7]. The quality of wheat grain depends not only on agronomic factors, such as nitrogen fertilization, but also on the cultivar, climatic conditions during growth and harvest, as well as the storage conditions after harvesting [8]. Nitrogen is absorbed by plants mainly in the form of nitrate (NO3−) and ammonium (NH4+), both of which have a significant impact on plant productivity. Plants can absorb amino acids from the soil; however, the significance of this process under field conditions is negligible [9]. Under soil nitrogen deficiency, plants adapt by increasing the transport of auxins from shoots to roots, which stimulates root growth through accelerated cell division.

Residual nitrogen refers to its inorganic forms, mainly as ammonium and nitrate ions, that remain in the soil after the end of the growing season. It is an estimated amount of nitrogen calculated as the difference between the nitrogen introduced into the soil (through mineral or organic fertilizers or biological fixation) and the nitrogen lost from the soil (taken up by plants and removed with the harvest or lost through denitrification and ammonia volatilization). Nitrates are usually the dominant form; they are highly soluble in water, which makes them prone to leaching into deeper soil layers and potentially reaching groundwater [10,11]. Nitrate leaching can be reduced by cover crops, which absorb nitrogen from the soil and incorporate it into their biomass, thereby limiting its movement into the deeper soil layers [12]. Cover crops play an important role here, particularly species from the families Brassicaceae and Poaceae, such as Italian ryegrass (Lolium multiflorum) and perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.), which efficiently utilize residual soil nitrogen remaining after the harvest of cereal crops [13].

Residual nitrogen (Nres) refers to the inorganic forms of nitrogen, primarily ammonium and nitrate ions, that remain in the soil after the growing season. It is an estimate of the amount of nitrogen calculated based on the difference between the nitrogen introduced into the soil (in mineral fertilizers, natural fertilizers, or through biological fixation) and the nitrogen that has been lost from the soil (N taken up by plants and carried with the crop, N lost through denitrification and volatilization as ammonia). Nitrates are typically the dominant form, as they dissolve readily in water and can leach into the soil and reach groundwater.

The aim of this study was to determine the effect of residual nitrogen (Nres) remaining in the soil after the cultivation of three maize (Zea mays L.) cultivars fertilized with different types of nitrogen fertilizers on the yield and chemical composition of grain of winter and spring common wheat (Triticum aestivum ssp. vulgare). Additionally, as in any factorial experiment, the interaction (variety × fertilizer) was very important, i.e., the interaction of these factors in the context of the successor crop. Research therefore provides the basis for optimising nitrogen management in crop rotation systems and reducing environmental losses.

2. Materials and Methods

The field experiment with maize as a preceding crop for wheat was conducted between 2017 and 2019 at the Variety Evaluation Experimental Station in Chrząstowo, Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship. The experiment was conducted over three growing seasons using a randomized split-plot block design with two experimental factors and three replicates. The first-order factor (A) was the maize cultivar: A1: ES Bombastic (FAO 230–240)—a single cross hybrid (SC), A2: ES Abakus (FAO 230–240)—a triple-cross hybrid (TC, stay-green type), A3: ES Metronom (FAO 240)—a single-cross hybrid (SC, stay-green + roots power type). The stay-green effect and the stronger root maize variety are very important regarding the amount of Nres, because these features determine nitrogen remobilization [9]. The second-order factor (B) was the type of nitrogen fertilizer: B1: control (no nitrogen fertilization), B2: ammonium nitrate, B3: urea, B4: ammonium nitrate + the nitrogen stabilizer N-Lock, B5: urea + N-Lock nitrogen stabilizer, B6: urea + N-Lock nitrogen stabilizer, B7: Super N-46, B7: UltraGran Stabilo. Mineral fertilization with basic macronutrients for all experimental plots, calculated as pure ingredient, was: 150 kg N/ha, 120 kg P2O5/ha, and 130 kg K2O/ha. The size of the research plot was 24 m2 The pH measured in the aqueous extract, expressed in pH units, was approximately 7.0 in the study, while the pH measured KCl was approximately 0.5 units lower and fell within the upper range of slightly acidic values. Organic carbon content was approximately 1%, which, when converted to humus, gives 1.7%. Total nitrogen content was 0.086%, and the C:N ratio was approximately 12:1. The content of available forms of potassium was 80.5 mg K/kg, which qualifies these soils for medium potassium content. The amount of available phosphorus and magnesium placed the tested soils in the very high content of these nutrients; the contents of these nutrients were 168.2 mg P/kg and 92.5 mg Mg/kg, respectively. In the control plots (B1), no nitrogen fertilization was applied; however, phosphorus and potassium fertilizers were used. Nitrogen fertilizers were applied to the plots immediately before maize sowing and incorporated into the soil. In treatments B4 and B5, the nitrogen stabilizer (N-Lock) was applied as a foliar spray at a rate of 1.7 L/ha, five days after nitrogen fertilizers. It contains 200 g of nitrapyrin in a microcapsule suspension and is designed to slow down the nitrification process. It prevents the conversion of the readily available and stable ammonium form into nitrate in the soil, increasing its availability to plants [N-Lock label].

2.1. Experimental Conditions for Winter and Spring Wheat Sown After Maize Harvest

After the maize harvest, winter wheat (in 2018) and spring wheat (in 2020) were sown in the plots corresponding to the respective experimental combinations. Spring and winter wheat were harvested, yield was estimated, followed by laboratory grain analysis. The gross plot area for sowing was 24 m2, and the net plot area for harvesting was 12 m2.

2.2. Agronomic Conditions for Wheat Cultivation

Winter wheat was sown on 27 September 2018 (Table 1). It was a bread wheat cultivar (A) Hondia, developed by the Polish breeding company Danko. Plant density was 400 plants/m2. No mineral fertilization was applied to the plots. Agronomic practices were limited to the use of a growth regulator along with fungicidal and insecticidal protection. The crop was harvested on 22 July 2019 using a Wintersteiger Delata plot combine. After harvest, yield and thousand-kernel weight (TKW) were determined and adjusted to 14% moisture content.

Table 1.

Dates of agronomic practices.

The spring wheat experiment was established on 21 March 2020 (Table 1). It was a bread wheat cultivar (A) Tybalt, developed by the Polish breeding company Danko. Plant density was 450 plants/m2. No mineral fertilization was applied to the plots. Agronomic practices were limited to the use of a growth regulator and fungicidal and insecticidal protection. The crop was harvested on 14 August 2020 using a Wintersteiger Delata plot combine. After harvest, yield and TKW were determined and adjusted to 14% moisture content. The thousand-grain weight was determined on two random samples of 500 grains each, taking the average and multiplying by 2. The chemical composition of the wheat grain (protein, starch, gluten) was determined by NIRS on an NRR-Flex N-500 apparatus from Büchi Labortechnik AG (Flawil, Switzerland) using ready-made calibration models developed by INGOT.

2.3. Climatic Conditions

The climatic conditions during the study were established based on data from the meteorological station at the Variety Evaluation Experimental Station in Chrząstowo, located on its premises. Table 2 presents the meteorological conditions from sowing to harvest of winter wheat (2018–2019). The growing season for winter wheat was defined as the months from March to July. These data were compared with long-term results from 2007 to 2019. In 2019, during the winter wheat growing season (March–July), the average monthly air temperatures were 1.1 °C higher compared to the same period in the long-term average from 2007 to 2019. The average monthly temperatures were lower than those recorded in the long-term 2007–2019 period only in May and July. The highest temperature difference (an increase of 4.3 °C) was recorded in the month of June. In 2019, total precipitation during the growing season (March–July) was 114 mm lower compared to the same period of the 2007–2019 long-term average. Only in May 2019 was the total precipitation higher than the long-term average. In April 2019, total precipitation amounted to only 3 mm. Table 3 presents the meteorological conditions during the growing season of spring wheat in 2020 (April–August). These data were compared with long-term results from 2007 to 2019.

Table 2.

Average monthly air temperature and monthly total precipitation during winter wheat growing season.

Table 3.

Average monthly air temperature and monthly total precipitation during spring wheat growing season.

In 2020, the average temperature during the growing season was 0.8 °C lower than the long-term average for 2007–2019. Except for June and August, monthly average temperatures were below the long-term values throughout the growing season. Total precipitation during the 2020 growing season was 85 mm higher than the long-term average. The highest precipitation was recorded in June (166 mm) and August (105 mm). Total precipitation in April amounted to only 4 mm. Generally, it can be stated that moisture conditions during the growth period of winter and spring wheat were optimal.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The experimental data were analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) according to a split-plot design. When significant main effects or interactions were identified, pairwise comparisons of means were conducted using Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) test [14,15]. Statistical significance was taken as p-value < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistica software package, version 13 (StatSoft, 2017), with Microsoft Excel used for supplementary calculations. Graphical representations were prepared in Microsoft Excel. The bar charts display mean values with standard deviations (SD), where bar height corresponds to the mean and error bars represent ± one standard deviation. Distinct lowercase letters (a, b, c, …) above the bars (Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7) and within the tables (Table 4, Table 5, Table 6, Table 7 and Table 8) denote statistically homogeneous groups as determined by Tukey’s test.

3. Results

3.1. Grain Yield

The grain yield of spring wheat in this study was significantly affected by the type of nitrogen fertilizer (Table 4). Analysis of the preceding crop showed that winter wheat grown after maize cultivar A2 produced a significantly higher grain yield than wheat grown after the other two maize cultivars (Table 4). Assessment of fertilizer type showed that grain yield for both winter and spring wheat was significantly higher after the application of slow-release nitrogen fertilizers compared with the control and nitrogen fertilizers without an inhibitor. Regardless of fertilizer type, winter wheat sown after maize cultivar A2 produced a significantly higher grain yield than after cultivars A1 and A3.

Table 4.

Effect of the tested factors on grain yield (dt/ha).

Table 4.

Effect of the tested factors on grain yield (dt/ha).

| Specification/ Experimental Factor | Factor Levels | Szulc et al. [16] | Winter Wheat | Spring Wheat |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Maize (2017–2019) | 2018/2019 | 2020 | |

| A | A1 | 70.8 c | 57.05 b | 52.43 a |

| A2 | 76.6 b | 65.31 a | 52.18 a | |

| A3 | 84.6 a | 57.05 b | 54.31 a | |

| p = 0.000835 | p = 0.004814 | p = 0.364797 | ||

| B | B1 | 69.5 d | 47.07 d | 48.60 c |

| B2 | 73.7 cd | 56.15 c | 50.74 bc | |

| B3 | 74.8 c | 59.24 b | 53.53 ab | |

| B4 | 77.5 bc | 60.68 b | 55.66 a | |

| B5 | 80.3 ab | 64.02 a | 54.63 a | |

| B6 | 82.3 a | 65.22 a | 54.41 a | |

| B7 | 83.4 a | 66.22 a | 53.23 ab | |

| p = 0.000000 | p = 0.000000 | p = 0.000000 | ||

| Mean | 77.3 | 59.80 | 52.97 | |

Statistical significance was taken as p < 0.05. Values marked with at least one same letter are not significantly different.

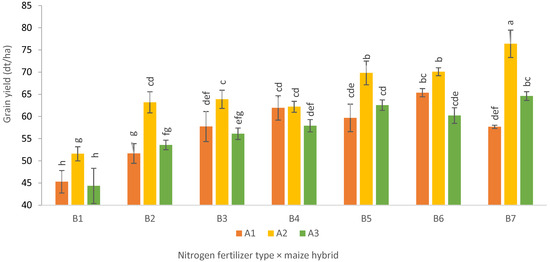

Figure 1 illustrates the interaction between nitrogen fertilizer type and maize hybrid on winter wheat grain yield. Means followed by different letters indicate significant differences according to Tukey’s test (p = 0.000000 < 0.05). It should be noted that the largest difference in grain yield between cultivars A1 and A2 occurred with nitrogen fertilizer B7.

Figure 1.

Effect of the interaction between nitrogen fertilizer type and maize hybrid on winter wheat grain yield (dt/ha). Values marked with at least one same letter are not significantly different.

3.2. Thousand-Kernel Weight (TKW)

The thousand-kernel weight (TKW) of spring wheat was significantly influenced by both the maize cultivar and type of nitrogen fertilizer (Table 5). When interpreting the effect of the preceding crop, a significantly highest TKW of both winter and spring wheat was found after the harvest of cultivar A1. Analysis of the effect of nitrogen fertilizer type on the TKW of winter and spring wheat demonstrated that a significantly higher TKW was obtained with fertilizers B6 and B7 (Table 5) compared to the other nitrogen fertilizer forms and the control plot.

Table 5.

Effect of the test factors on thousand-kernel weight (g).

Table 5.

Effect of the test factors on thousand-kernel weight (g).

| Specification/ Experimental Factor | Factor Levels | Winter Wheat | Spring Wheat |

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 2018/2019 | 2020 | |

| A | A1 | 50.17 a | 38.99 a |

| A2 | 49.12 c | 38.78 ab | |

| A3 | 49.66 b | 38.63 b | |

| p = 0.002746 | p = 0.042945 | ||

| B | B1 | 48.35 d | 37.80 c |

| B2 | 47.47 e | 38.67 b | |

| B3 | 49.00 cd | 38.75 ab | |

| B4 | 49.61 c | 38.92 ab | |

| B5 | 50.42 b | 38.94 ab | |

| B6 | 51.48 a | 39.26 a | |

| B7 | 51.22 a | 39.27 a | |

| p = 0.000000 | p = 0.000000 | ||

| Mean | 49.65 | 38.80 | |

Statistical significance was taken as p < 0.05. Values marked with at least one same letter are not significantly different.

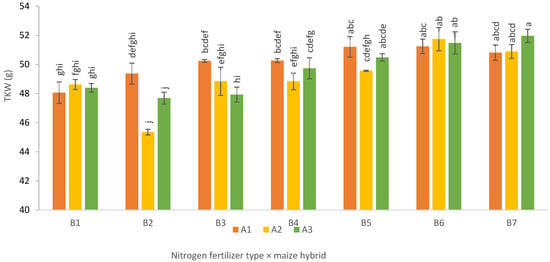

Additionally, a significant interaction between nitrogen fertilizer type and maize hybrid was observed for the TKW of winter wheat (Figure 2). Means followed by different letters indicate significant differences according to Tukey’s test (p = 0.000000 < 0.05). Notably, the lowest TKW was not found in the control treatment but in the combinations of cultivars A2 and A3 with nitrogen fertilizer B2.

Figure 2.

Effect of the interaction between nitrogen fertilizer type and maize hybrid on thousand-kernel weight of winter wheat grain (g). Values marked with at least one same letter are not significantly different.

3.3. Chemical Composition of Grain

There was a significant effect of the preceding maize crop, the type of nitrogen carrier, and their interaction on grain protein content in both winter and spring wheat (Table 6). Investigating the effect of the preceding crop, grain harvested after cultivar A3 showed the highest protein content compared to the other cultivars. Regarding the nitrogen source, the highest protein content in winter wheat grain was recorded for treatment B3. For spring wheat, the highest value (14.26%) was recorded after ammonium nitrate (B2) and in the control treatment. These did not differ significantly from the values obtained after fertilizers B3 and B5 (Table 6).

Table 6.

Effect of the test factors on grain protein content [%].

Table 6.

Effect of the test factors on grain protein content [%].

| Specification/ Experimental Factor | Factor Levels | Winter Wheat | Spring Wheat |

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 2018/2019 | 2020 | |

| A | A1 | 10.03 b | 13.96 c |

| A2 | 10.12 b | 14.07 b | |

| A3 | 11.32 a | 14.40 a | |

| p = 0.000465 | p = 0.000068 | ||

| B | B1 | 9.70 c | 14.26 a |

| B2 | 10.91 b | 14.26 a | |

| B3 | 12.17 a | 14.17 ab | |

| B4 | 11.16 b | 14.10 b | |

| B5 | 9.87 c | 14.11 ab | |

| B6 | 9.63 c | 14.07 b | |

| B7 | 10.01 c | 14.06 b | |

| p = 0.000000 | p = 0.000141 | ||

| Mean | 10.49 | 14.14 | |

Statistical significance was taken as p < 0.05. Values marked with at least one same letter are not significantly different.

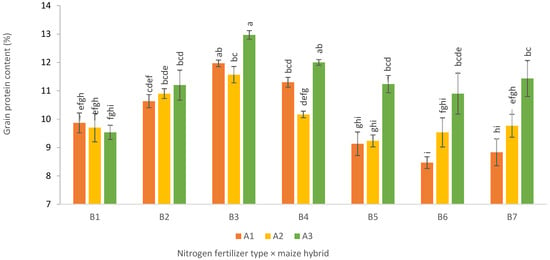

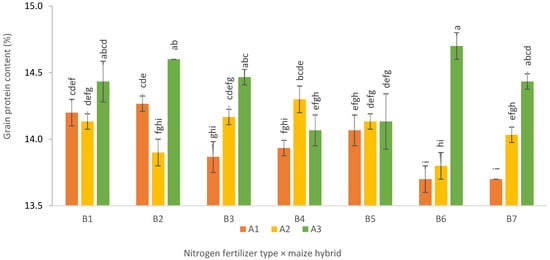

The experiment also showed a significant interaction between the type of nitrogen fertilizer and the maize hybrid on grain protein content in both winter (Figure 3) and spring wheat (Figure 4). Different letters denote statistically significant differences among means according to Tukey’s test (p = 0.000000 < 0.05). The largest differences in grain protein content in winter wheat occurred after cultivar A3 and the application of slow-release fertilizers (B5–B7). For spring wheat, the greatest significant differences in grain protein content were also observed after cultivar A3 and fertilizers B6–B7.

Figure 3.

Effect of the interaction between nitrogen fertilizer type and maize hybrid on protein content in winter wheat grain (%). Values marked with at least one same letter are not significantly different.

Figure 4.

Effect of the interaction between nitrogen fertilizer type and maize hybrid on protein content in spring wheat grain (%). Values marked with at least one same letter are not significantly different.

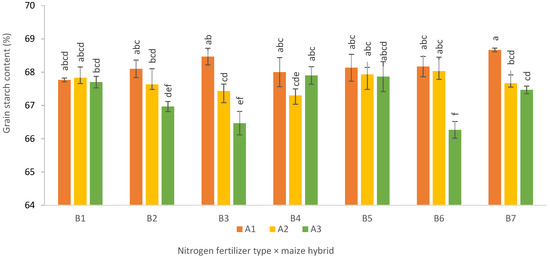

The study found that the preceding crop, nitrogen fertilizer type, and their interaction significantly affected starch content in spring wheat grain (Table 7). Starch content in winter wheat grain was significantly influenced by the preceding crop and the type of nitrogen fertilizer. Investigating the influence of the preceding crop on starch content in spring wheat grain and winter wheat grain the highest values were obtained after harvest of cultivar A1. Assessing the effect of nitrogen fertilizer on starch content in winter wheat grain, the highest values were obtained with stabilized fertilizers (B6 and B7) and in the control plot (B1). In spring wheat, the highest statistically significant grain starch contents were obtained with fertilizers B5 and B7 (Table 7).

Table 7.

Effect of the test factors on grain starch content (%).

Table 7.

Effect of the test factors on grain starch content (%).

| Specification/ Experimental Factor | Factor Levels | Winter Wheat | Spring Wheat |

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 2018/2019 | 2020 | |

| A | A1 | 71.75 a | 68.19 a |

| A2 | 71.60 a | 67.69 b | |

| A3 | 70.21 b | 67.23 c | |

| p = 0.000115 | p = 0.001525 | ||

| B | B1 | 72.04 a | 67.77 ab |

| B2 | 70.77 b | 67.57 ab | |

| B3 | 69.58 c | 67.46 b | |

| B4 | 70.74 b | 67.73 ab | |

| B5 | 71.62 ab | 67.98 a | |

| B6 | 71.87 a | 67.49 b | |

| B7 | 71.69 a | 67.93 a | |

| p = 0.000000 | p = 0.001673 | ||

| Mean | 71.19 | 67.70 | |

Statistical significance was taken as p < 0.05. Values marked with at least one same letter are not significantly different.

The experiment showed a significant interaction between nitrogen fertilizer carrier and the preceding crop on starch content in spring wheat grain (Figure 5). Means followed by different letters indicate significant differences according to Tukey’s test (p = 0.000000 < 0.05). Regardless of the type of nitrogen fertilizer applied, except for the control plot, the highest starch content was observed following maize cultivar A1. The lowest starch content in spring wheat grain was observed following maize cultivar A3, with the exception of nitrogen fertilizer B4.

Figure 5.

Effect of the interaction between nitrogen fertilizer type and maize hybrid on starch content in spring wheat grain (%). Values marked with at least one same letter are not significantly different.

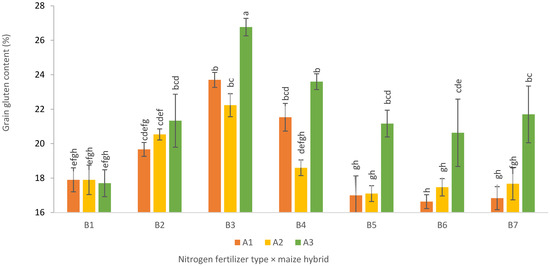

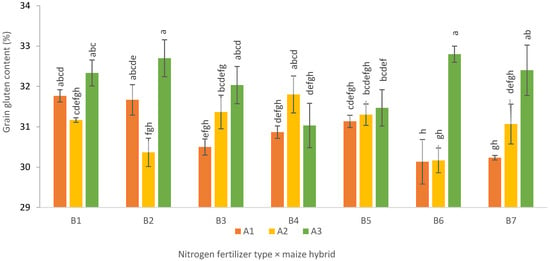

The experiment demonstrated a significant effect of the preceding crop, the type of nitrogen fertilizer, and their interaction on gluten content in the grain of both winter and spring wheat (Table 8). Analysis of the preceding crop effect showed that the highest gluten content in the grain of both wheat forms was obtained following cultivar A3 (Table 8). When verifying the influence of the type of nitrogen fertilizer on the gluten content in winter wheat grain, the significantly highest result was obtained with fertilizer B3, while the highest gluten content in spring wheat grain was recorded in the unfertilized plot.

Table 8.

Effect of the test factors on grain gluten content (%).

Table 8.

Effect of the test factors on grain gluten content (%).

| Specification/ Experimental Factor | Factor Levels | Winter Wheat | Spring Wheat |

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 2018/2019 | 2020 | |

| A | A1 | 19.04 b | 30.90 b |

| A2 | 18.79 b | 31.03 b | |

| A3 | 21.84 a | 32.11 a | |

| p = 0.000077 | p = 0.000578 | ||

| B | B1 | 17.83 c | 31.76 a |

| B2 | 20.51 b | 31.58 ab | |

| B3 | 24.23 a | 31.30 ab | |

| B4 | 21.24 b | 31.23 ab | |

| B5 | 18.42 c | 31.30 ab | |

| B6 | 18.24 c | 31.03 b | |

| B7 | 18.73 c | 31.23 ab | |

| p = 0.000000 | p = 0.007491 | ||

| Mean | 19.89 | 31.35 | |

Statistical significance was taken as p < 0.05. Values marked with at least one same letter are not significantly different.

The results indicate a significant interaction between the type of nitrogen fertilizer and the maize cultivar (preceding crop) on gluten content in the grain of winter wheat (Figure 6) and spring wheat (Figure 7). Means followed by different letters indicate significant differences according to Tukey’s test (p = 0.000063 < 0.05 (Figure 6) and p = 0.000000 < 0.05 (Figure 7)).

For winter wheat, the highest gluten content for all nitrogen-fertilized treatments was recorded following maize cultivar A3. The highest significant value was observed with fertilizer B3, while the largest significant differences in gluten content between cultivars were demonstrated with the slow-release fertilizers (B5–B7). For the interaction between nitrogen fertilizer type and maize hybrid on gluten content in spring wheat, the largest significant differences were observed with the slow-release fertilizers (B6 and B7).

Figure 6.

Effect of the interaction between nitrogen fertilizer type and maize hybrid on gluten content in winter wheat grain (%). Values marked with at least one same letter are not significantly different.

Figure 7.

Effect of the interaction between nitrogen fertilizer type and maize hybrid on gluten content in spring wheat grain (%). Values marked with at least one same letter are not significantly different.

4. Discussion

In wheat cultivation, nitrogen plays a key role in yield formation, as the plant requires on average 22–26 kg of N per hectare to produce 1 ton of grain (including the corresponding straw mass), and up to 30 kg N/ha for high-quality cultivars [17,18]. Both an excess and a deficiency of this primary macronutrient adversely affect wheat yield. The absence of this element limits plant development by reducing the number of tillers and the formation of spikes and flowers, ultimately lowering both grain yield and quality, including a decrease in grain protein content [5]. Excess nitrogen applied to the soil, or as foliar sprays, leads to higher plant density due to vigorous growth and tillering. It also extends the plants’ growing period. Plant tissues absorbing excessive nitrogen become soft, making them more susceptible to damage. These factors increase disease pressure, including eyespot, powdery mildew, and tan spot [19,20].

In Poland, the maximum permissible nitrogen from all sources is 160 kg N/ha for spring wheat and 200 kg N/ha for winter wheat, while the nitrogen requirement per ton of grain is set at 27 kg N for both wheat types [21]. Over the past decade, winter wheat yields averaged 46.4–54.8 dt/ha, compared with 32.6–42.4 dt/ha for spring wheat [22]. In practice and field trials, winter wheat yields can reach over 10 tons of grain per hectare [23,24]. Considering that a realistic grain yield exceeds 10 t/ha and assuming wheat requires 27 kg N per ton of grain, the plant must have access to over 270 kg of available nitrogen in the soil. Current regulations permit the application of only 170 kg N/ha, thus the plant must obtain the remaining nitrogen from soil resources [UE 91(676/EWG)]. This example illustrates the importance of soil nitrogen in achieving high grain yields, even under intensive mineral fertilization during the growing season. On the other hand, residual nitrogen (Nres), as in this trial, may be the only source of nitrogen available to the plant, and the type of mineral fertilizer that supplied this nitrogen can influence the yield of the subsequent crop to a greater or lesser extent. This may be particularly significant in European Union (EU) countries, including Poland, in the near future. The reason is the increasing ambitious pro-environmental goals of the EU, which aim to reduce the pressure of agriculture on the environment, including reduced fertilizer applications. Consequently, there is a growing need to maximize the use of nitrogen supplied to the plant through mineral fertilizers, including those applied to the preceding crop [25].

Establishing upper limits for nitrogen fertilizer application is primarily intended to reduce the negative impact of agriculture on the environment by minimizing losses of this nutrient in the form of gaseous products such as ammonia (NH3), molecular nitrogen (N2), nitrous oxide (N2O), and nitrates leached into groundwater [26]. Reducing nitrogen losses not only benefits the environment but also has a direct impact on the farm’s economic performance. The recent sharp fluctuations in the prices of both production inputs, such as mineral fertilizers, and agricultural products, including wheat grain, resulting from market conditions related to the pandemic and the armed conflict in Ukraine, should prompt farmers to pay closer attention to the types of mineral fertilizers they use [27]. The trial demonstrated that both winter wheat (2018/2019) and spring wheat (2020) produced significantly higher grain yields following the application of stabilized nitrogen fertilizers to the preceding crop (maize). In winter oilseed rape, Slimka et al. [28] reported a positive effect of stabilized fertilizers on seed yield. Autumn application of stabilized nitrogen fertilizers in the experimental cycle proved to be very beneficial. Rapeseed plants from the research combinations in which autumn nitrogen fertilization was applied achieved higher yields (on average by 0.3 t/ha, i.e., 8.1% more on average between 2009/10 and 2010/11). The effectiveness of nitrogen fertilizer application in autumn is directly proportional to the length of the autumn rapeseed growing season. When winter dormancy occurs later in rapeseed plants, the application of stabilized nitrogen fertilizers becomes more important for achieving high seed yields. The advantage of applying this type of fertilizer is the gradual release of plant-available nitrogen while simultaneously reducing losses resulting from leaching from the soil or escape into the atmosphere. In Pakistan, Sarwar et al. [29] demonstrated that the use of natural nitrogen stabilizers also improved wheat yields, emphasizing the need to reduce nitrogen losses, particularly in developing countries such as Pakistan. In the study by Wallace et al. [30], fertilizers with an inhibitor increased wheat yields by 7–11% in two out of three years. Both the present experiment and literature data indicate that stabilized fertilizers can increase the yields of wheat and other cultivated plants while additionally reducing nitrogen losses, which may become necessary if restrictions on mineral fertilizer use are implemented [31,32,33]. In the current work, the highest winter wheat grain yields were obtained following the application of urea fertilizers with synthetic urease inhibitors to the preceding crop, specifically fertilizer B6 containing N-(n-butyl) thiophosphoric acid triamide (NBPT) and fertilizer B7 containing NBPT combined with N-(n-propyl) thiophosphoric acid triamide (NPPT). High grain yields of both winter and spring wheat were also obtained following the application of fertilizers B4 (ammonium nitrate) and B5 (urea) with a nitrification inhibitor (nitrapyrin-2-chloro-6-(trichloromethyl)pyridine) applied as a spray, compared with fertilizers without inhibitors. Higher yields after fertilization with inhibitors may result from lower nitrogen losses in the preceding crop, which increases its availability in the soil during wheat cultivation. According to Alonso-Ayuso et al. [34], fertilizers containing a nitrification inhibitor improved nitrogen use efficiency in maize in the year following their application compared with conventional fertilizer. The use of slow-release fertilizers may also be caused by changes in the soil microbiome. According to data from Rusyn et al. [35], the use of coated fertilizer increased barley seed germination by 4.14 times compared to without fertilizer. In these studies, this fertilizer provided a prolonged release of mineral nutrients, which positively affected seed germination and also stimulated the total number of microorganisms in the soil, which is an important indicator of agricultural efficiency. Reducing nitrogen losses through the use of inhibitors increases the amount of available nitrogen in the following season. Grain protein content depends largely on cultivar traits, site conditions, and agronomic practices, including nitrogen fertilization [36,37]. In this trial, spring wheat was characterized by a higher average protein level compared to winter wheat. Previous studies have also reported higher protein content in spring wheat compared to winter wheat [38,39]. This stems from genetic variation and the capacity for nitrogen storage in the grain of individual cultivars [40]. In a study conducted in Estonia by Koppel and Ingver [38], winter wheat produced higher yields, but spring wheat had better grain quality parameters. According to Zhang et al. [41], increasing both wheat grain yield and grain protein content is difficult; however, agronomic practices such as applying slow-release fertilizers can help achieve this objective. A major advantage of slow-release fertilizers is that the nutrient (N) is released in response to the dynamic demand of the crop. This, on the one hand, increases grain yield and, on the other, does not negatively impact the agrosystem (eutrophication). The positive effect of such fertilizers on the following crop has been demonstrated in our own research.

5. Conclusions

The type of nitrogen fertilizer used turned out to be the main factor determining wheat yields, regardless of the form (winter, spring). The most stable effect of the type of nitrogen, regardless of the type of maize variety, was recorded for ammonium nitrate with N-Lock. The average yield was approximately 6.1 t/ha. The higher yield of wheat in the stand after maize of the stay green variety results from both its lower yield compared to the stay-green + roots power variety and a stronger response to fertilizers such as U + N-Lock, and especially SG Stabilo. The lack of response of spring wheat to the interaction of the variety and type of nitrogen fertilizer is probably due to the exhaustion of N reserves in the soil in the third season after application. With the exception of the variant with N-Lock, the most progressive reaction to the type of fertilizer occurred in the stand with a three-line maize hybrid (TC, stay green). The advantage of this corn variety as a winter wheat forecrop results from the value of the site in a site without nitrogen. In the nitrogen control, the increase in yield compared to the single maize hybrid (SC) was 14%. However, in the U + N-Lock variant, it was 17%, and SG Stabilo as much as 32%. The increase in the weight of 1000 wheat grains in the stands after the SC and TC hybrid compared to stay green + roots power indicates a compensatory mechanism that became visible in the grain filling phase. These mechanisms are biological, physiological or agrotechnical in nature and are aimed at maintaining the stability of yields and the quality of agricultural products. The decrease in protein content in grain of winter wheat clearly indicates the appearance of the nitrogen dilution effect (higher grain yield).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.S. (Piotr Szulc), R.I. and K.A.-D.; methodology, P.S. (Piotr Szulc) and K.A.-D.; software, R.W. and K.G.; validation, P.S. (Piotr Szulc), P.S. (Przemysław Strażyński) and R.W.; formal analysis, K.A.-D.; investigation, P.S. (Przemysław Strażyński); resources, R.W.; data curation, K.G.; writing—original draft preparation, P.S. (Piotr Szulc); writing—review and editing, K.A.-D.; visualization, P.S. (Przemysław Strażyński); supervision, R.W.; project administration, K.G.; funding acquisition, P.S. (Piotr Szulc). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Financing from the funds of the Department of Agronomy (Statutory research of the entity).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Naeem, M.K.; Ahmad, M.; Kamran, M.; Shah, M.K.N.; Iqbal, M.S. Physiological responses of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) to drought stress. Int. J. Plant Soil Sci. 2015, 6, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshawih, S.; Abdullah Juperi, R.N.A.; Paneerselvam, G.S.; Ming, L.C.; Liew, K.B.; Goh, B.H.; Al-Worafi, Y.M.; Choo, C.Y.; Thuraisingam, S.; Goh, H.P.; et al. General Health Benefits and Pharmacological Activities of Triticum aestivum L. Molecules 2022, 27, 1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, S.; Modi, P.; Dave, A.; Vijapura, A.; Patel, D.; Patel, M. Effect of Abiotic Stress on Crops. In Sustainable Crop Production; Hasanuzzaman, M., Fujita, M., Teixeira Filho, M.C.M., Nogueira, T.A.R., Galindo, F.S., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Nyaupane, S.; Poudel, M.R.; Panthi, B.; Dhakal, A.; Paudel, H.; Bhandari, R. Drought stress effect, tolerance, and management in wheat—A review. Cogent Food Agric. 2024, 10, 2296094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocoń, A. Efektywność wykorzystania azotu z mocznika [15 N] stosowanego dolistnie lub doglebowego przez pszenice ozima i bobik. Acta Agrophys. 2003, 85, 55–63. [Google Scholar]

- Sułek, A.; Cacak-Pietrzak, G.; Ceglińska, A. Wpływ różnych sposobów aplikacji azotu na plon, elementy jego struktury oraz wybrane cechy jakościowe ziarna odmian pszenicy jarej. Agron. Sci. 2004, 59, 543–551. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B.; Liu, E.; Tian, Q.; Yan, C.; Zhang, Y. Soil nitrogen dynamics and crop residues. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 34, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stępniewska, S.; Słowik, E. Ocena wartości technologicznej wybranych odmian pszenicy ozimej i jarej. Acta Agrophys. 2016, 23, 275–286. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, W.; Wang, Y.; Ye, Y.; Zhen, S.; Zhou, B.; Wang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, Y. Grain Yields and Nitrogen Use Efficiencies in Different Types of Stay-Green Maize in Response to Nitrogen Fertilizer. Plants 2020, 9, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamun, A.; Sharif, H.O. Quantification of Nitrate Level in Shallow and Deep Groundwater Wells for Drinking, Domestic and Agricultural Uses in Northeastern Arid Regions of Saudi Arabia. Limnol. Rev. 2024, 24, 178–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, A.; Campanale, M. Agricultural nitrate leaching into groundwater—Case of study in Apulia Region. Ecol. Eng. Environ. Technol. 2024, 25, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball-Coelho, B.R.; Roy, R.C. Overseeding rye into corn reduces NO3 leaching and increases yields. Can. J. Soil Sci. 1997, 77, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrzejewska, J. Międzyplony w zmianowaniach zbożowych. Postępy Nauk Rol. 1999, 46, 19–31. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez, K.A.; Gomez, A.A. Statistical Procedures for Agricultural Research, 2nd ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1984; p. 680. [Google Scholar]

- Szulc, P.; Mejza, I.; Ambroży-Deręgowska, K.; Nowosad, K.; Bocianowski, J. The comparison of three models applied to the analysis of a three-factor trial on hybrid maize (Zea mays L.) cultivars. Biom. Lett. 2016, 53, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szulc, P.; Krauklis, D.; Ambroży-Deręgowska, K.; Wróbel, B.; Niedbała, G.; Niazian, M.; Selwet, M. Response of Maize Varieties (Zea mays L.) to the Application of Classic and Stabilized Nitrogen Fertilizers—Nitrogen as a Predictor of Generative Yield. Plants 2023, 12, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madej, A.; Rutkowska, A.; Smerczak, B.; Matyka, M.; Kopiński, J. Środowiskowe aspekty zakwaszenia gleb w Polsce. IUNG 2017, 43, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Błaszczyk, K. Wymagania siedliskowe i pokarmowe pszenicy ozimej. Probl. Nauk Przyr. Tech. 2019, 3, 14–22. [Google Scholar]

- Lipa, J. Wpływ nawożenia mineralnego na występowanie chorób i szkodników roślin. Postępy Nauk Rol. 1992, 39, 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Moszczyńska, E.; Pląskowska, E. Ocena zdrowotności pszenicy ozimej uprawianej tradycyjnie, w siewie bezpośrednim oraz w siewie bezpośrednim z wsiewką koniczyny białej [Evalution of the healthiness of winter wheat cultivated in conventional tillage, direct sowing and direct sowing with underplant crop of white clover]. Acta Agrobot. 2005, 58, 277–286. [Google Scholar]

- Journal of Laws of the Republic of Poland. Regulation of 12 February 2020 on the Adoption of the Programme of Measures to Reduce Water Pollution by Nitrates from Agricultural Sources and to Prevent Further Pollution. Journal of Laws 2020, Item 243. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Główny Urząd Statystyczny. Rocznik Statystyczny Rolnictwa 2024; GUS: Warszawa, Poland, 2024. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/roczniki-statystyczne/roczniki-statystyczne/rocznik-statystyczny-rolnictwa-2024,6,18.html (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Oleksiak, T. Znaczenie postępu hodowlanego w produkcji pszenicy ozimej. Ann. Pol. Assoc. Agric. Agrobus. Econ. 2023, 25, 338–349. [Google Scholar]

- COBORU. Lista Odmian Roślin Rolniczych Wpisanych do Krajowego Rejestru w Polsce 2024; Centralny Ośrodek Badania Odmian Roślin Uprawnych: Słupia Wielka, Poland, 2024. Available online: https://coboru.gov.pl/Publikacje_COBORU/Listy_odmian/lo_rolnicze_2024.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Madajska, K.; Tratwal, A.; Bocianowski, J. Przydatność pszenżyta ozimego w różnych warunkach gospodarowania w świetle wymogów integrowanej ochrony oraz Europejskiego Zielonego Ładu. The suitability of winter triticale in different farming conditions in the light of the requirements of integrated pest management and the European Green Deal. Prog. Plant Prot. 2025, 65, 40–52. [Google Scholar]

- Jarosz, Z.; Faber, A. Projekcja regionalnego zróżnicowania emisji amoniaku ze zużycia mineralnych nawozów azotowych. Stud. Rap. IUNG-PIB 2022, 67, 121–130. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, A.; Wnuczek, R. Ocena opłacalności produkcji pszenicy ozimej i jęczmienia jarego w zróżnicowanych uwarunkowaniach rynkowych. Agron. Sci. 2024, 79, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slimka, J.; Miksik, V.; Becka, D.; Vasak, J.; Zukalová, H. Znaczenie jesiennego stosowania klasycznych i stabilizowanych nawozów azotowych w nawożeniu rzepaku ozimego (Brassica napus L. convar. napus f. biennis). Rośliny Oleiste-Oilseed Crops 2012, 33, 90–97. [Google Scholar]

- Sarwar, N.; Wasaya, A.; Saliq, S.; Reham, A.; Farooq, O.; Mubeen, K.; Shehzad, M.; Zahoor, M.U.; Ghani, A. Use of Natural Nitrogen Stabilizers to Improve Nitrogen use Efficiency and Wheat Crop Yield. Cercet. Agron. Mold. 2019, 52, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, A.J.; Armstrong, R.D.; Grace, P.R.; Scheer, C.; Partington, D.L. Nitrogen use efficiency of 15N urea applied to wheat based on fertiliser timing and use of inhibitors. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2020, 116, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szulc, P.; Waligóra, H.; Michalski, T.; Bocianowski, J.; Rybus-Zając, M.; Wilczewska, W. The size of the Nmin soil pool as a factor impacting nitrogen utilization efficiency in maize (Zea mays L.). Pak. J. Bot. 2018, 50, 189–198. [Google Scholar]

- Szulc, P.; Krauklis, D.; Ambroży-Deręgowska, K.; Wróbel, B.; Zielewicz, W.; Niedbała, G.; Kardasz, P.; Niazian, M. Evaluation of the Effect of Conventional and Stabilized Nitrogen Fertilizers on the Nutritional Status of Several Maize Cultivars (Zea mays L.) in Critical Growth Stages Using Plant Analysis. Agronomy 2023, 13, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szulc, P.; Krauklis, D.; Ambroży-Deręgowska, K.; Wróbel, B.; Zielewicz, W.; Niedbała, G.; Kardasz, P.; Selwet, M.; Niazian, M. Evaluation of the effectiveness of NBPT and NPPT application as a urease carrier in fertilization of maize (Zea mays L.) for ensiling. Agronomy 2023, 13, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Ayuso, M.; Gabriel, J.L.; Quemada, M. Nitrogen use efficiency and residual effect of fertilizers with nitrification inhibitors. Eur. J. Agron. 2016, 80, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusyn, A.; Malovanyy, M.; Tymchuk, I.; Synelnikov, S. Effect of mineral fertilizer encapsulated with zeolite and polyethylene terephthalate on the soil microbiota, pH and plant germination. Ecol. Quest. 2020, 32, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woźniak, A. Wpływ przedplonów na plon i jakość ziarna pszenicy ozimej. Acta Sci. Polonorum. Agric. 2006, 5, 99–106. [Google Scholar]

- Harasim, E.; Wesołowski, M. Wpływ retardanta Modus 250 EC i nawożenia azotem na plonowanie i jakość ziarna pszenicy ozimej. Fragm. Agron. 2013, 30, 70–77. [Google Scholar]

- Koppel, R.; Ingver, A. A comparison of the yield and quality traits of winter and spring wheat. Latv. J. Agron. 2008, 11, 83–89. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Wang, Z.H.; Li, F.C.; Li, K.Y.; Yang, N.; Yang, Y.E. Contents of protein and amino acids of wheat grain in different wheat production regions and their evaluation. Acta Agron. Sin. 2016, 42, 768–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Song, X.; Yang, G.; Li, Z.; Zhang, D.; Feng, H. Monitoring of nitrogen and grain protein content in winter wheat based on Sentinel-2A data. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Liu, S.; Dong, Y.; Liao, Y.; Han, J. A nitrogen fertilizer strategy for simultaneously increasing wheat grain yield and protein content: Mixed application of controlled-release urea and normal urea. Field Crops Res. 2022, 277, 108405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.