An Earthworm-Inspired Subsurface Robot for Low-Disturbance Mitigation of Grassland Soil Compaction

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Grassland and Agricultural Soil Degradation and Compaction

1.2. Techniques for Mitigating Soil Compaction and Their Limitations

1.3. Potential Role of Subsurface Robots in Conservation Agriculture

1.4. Objectives and Contributions of This Study

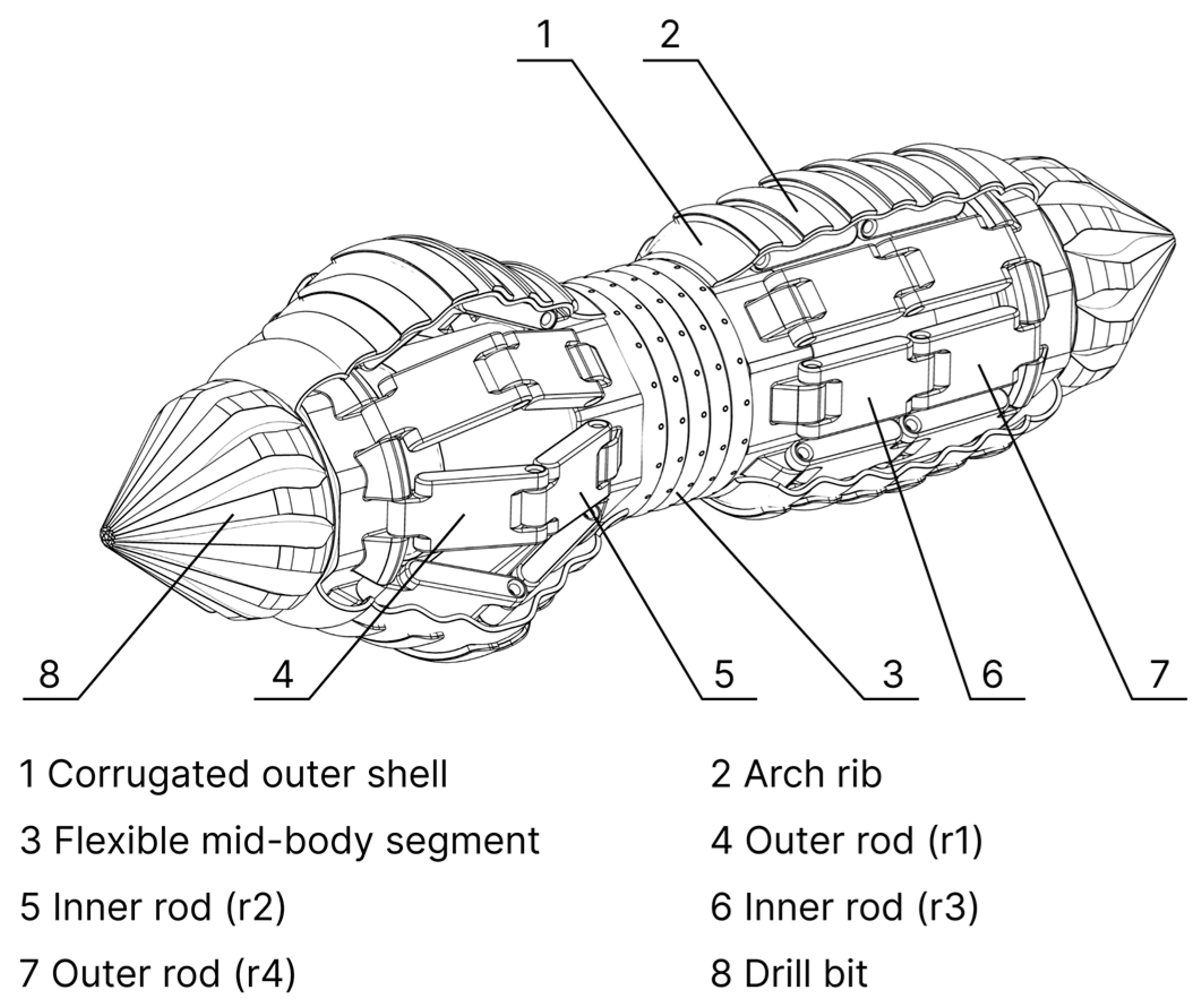

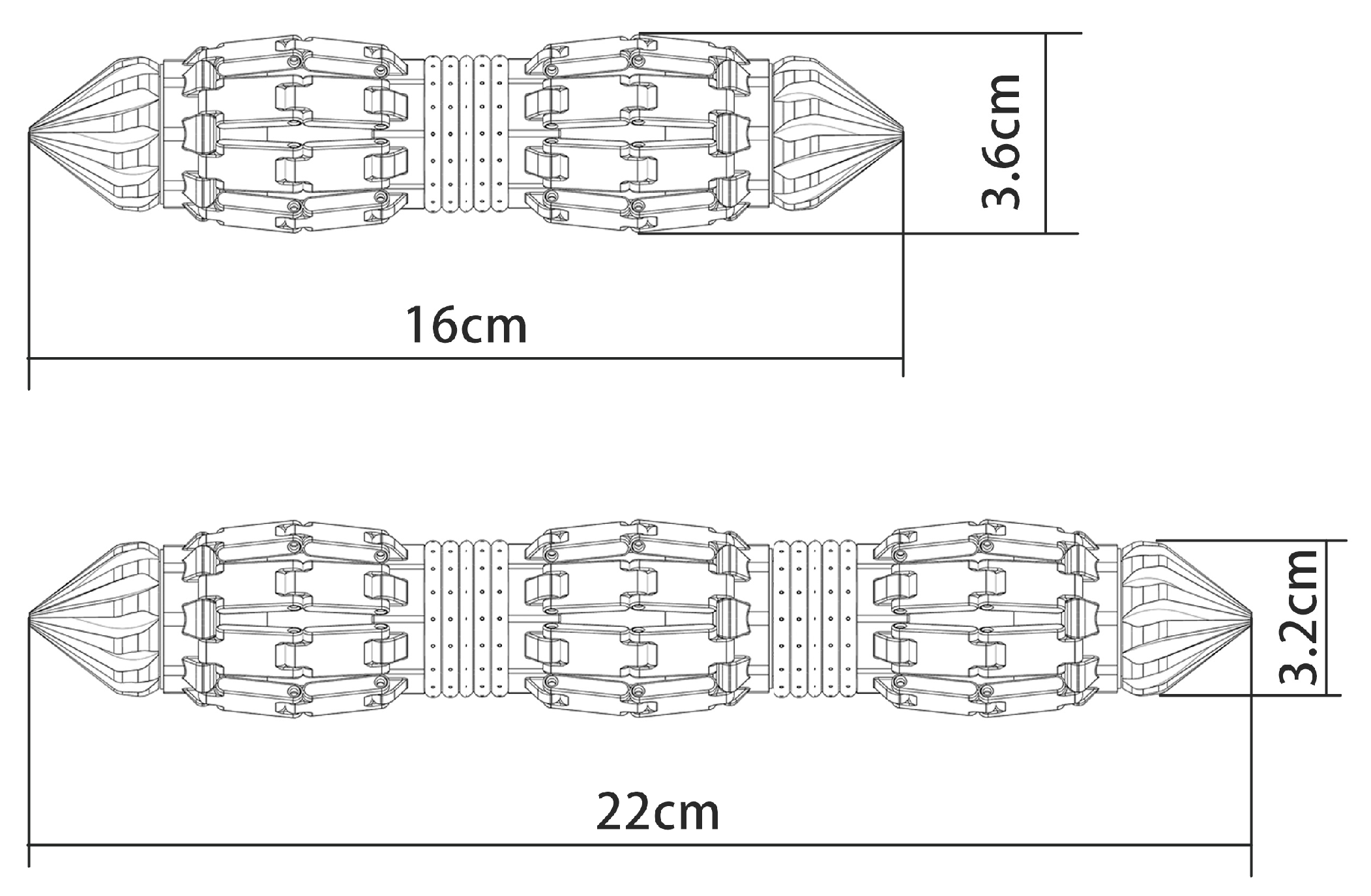

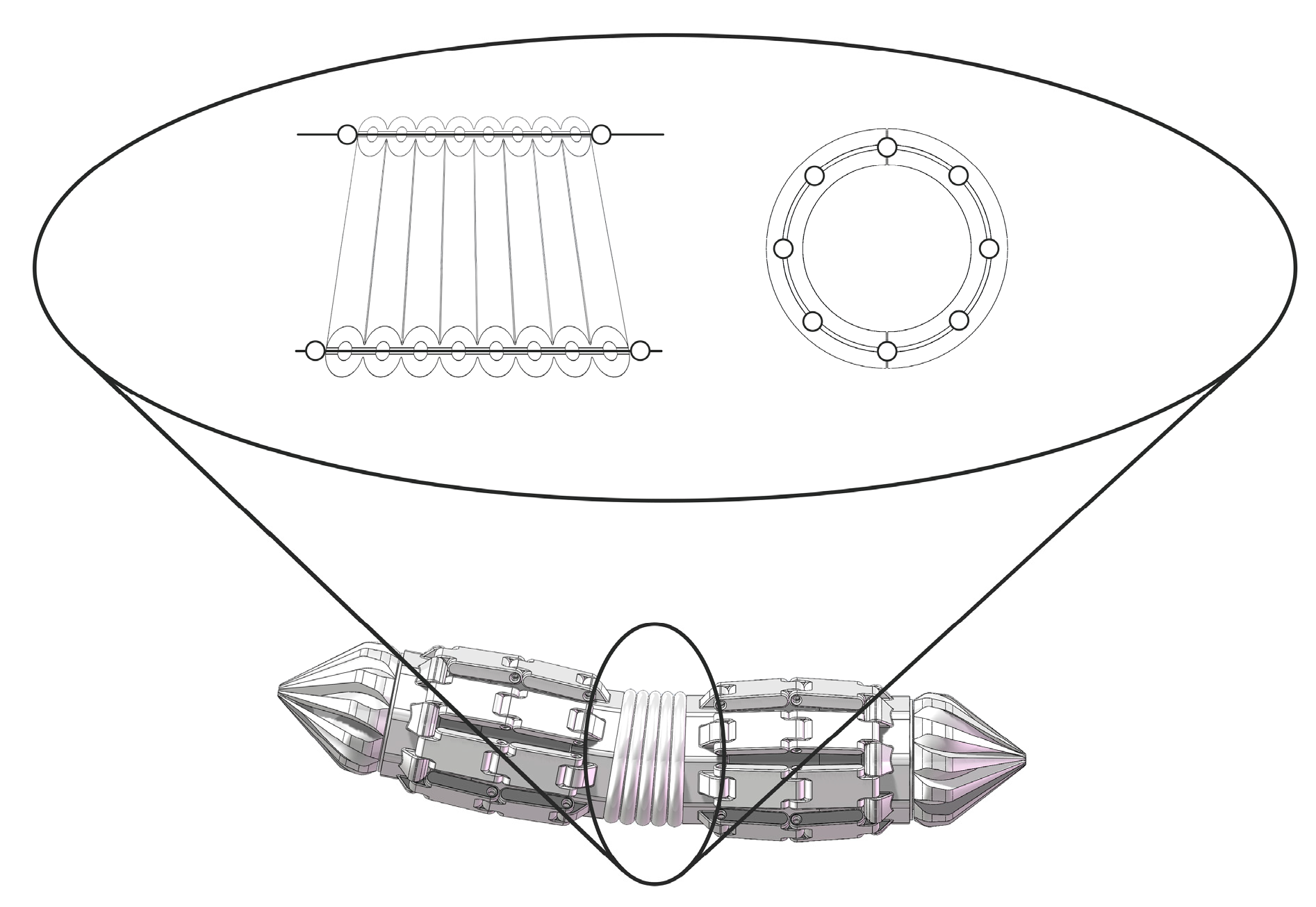

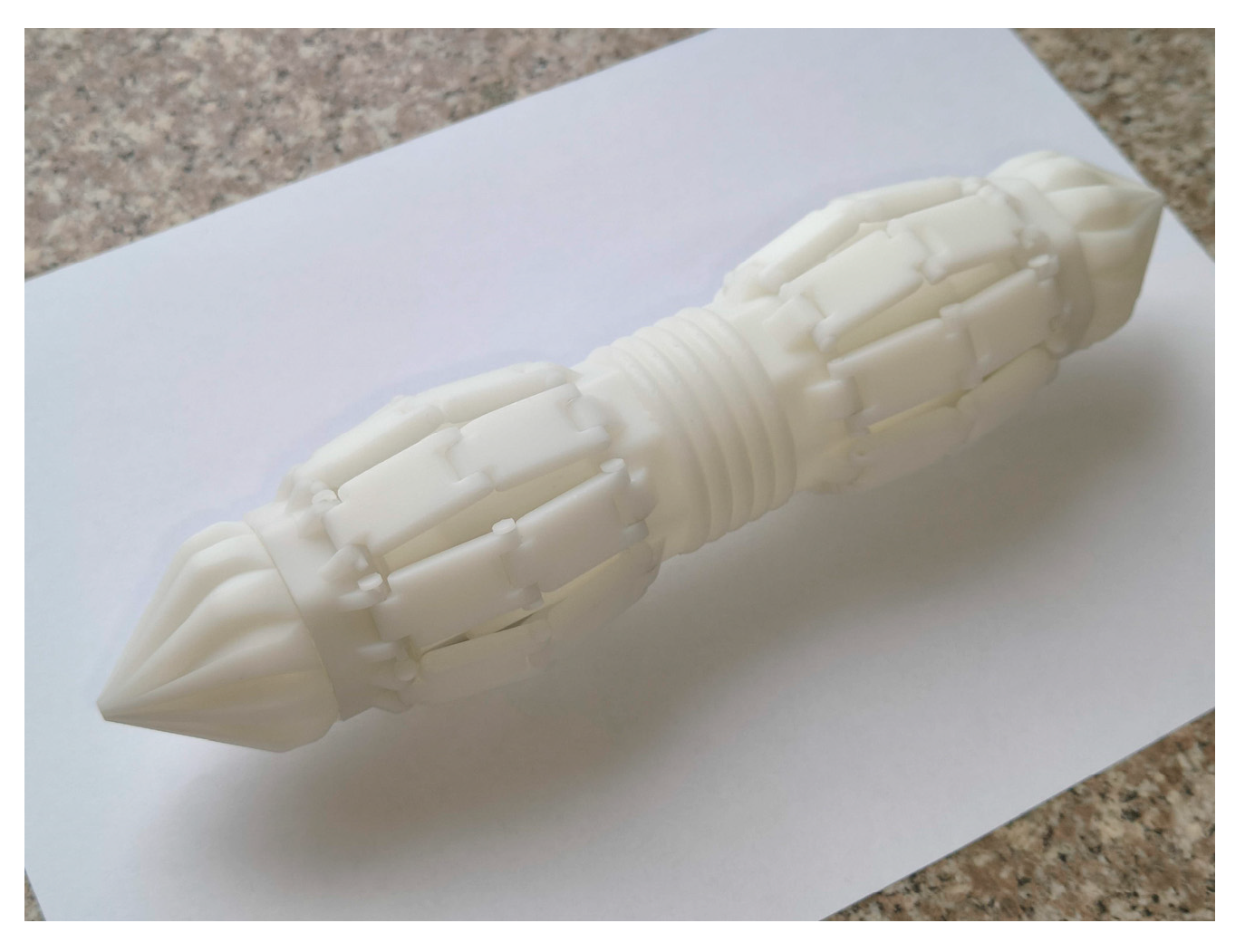

- From anatomical observations and kinematic analysis of earthworm motion, we abstract three design principles related to segmented extension, local compliance and surface corrugation and implement them in a motor-driven, rigid multi-link architecture comprising telescopic linkage modules, a flexible mid-body segment and a corrugated outer shell. This architecture is intended to emulate earthworm-like flexible locomotion while providing the structural strength and durability required for subsurface operation in compacted grassland soils.

- We establish a multi-level modelling framework that couples peristaltic kinematics with soil–structure interaction using the Modified Cam–Clay model. This framework allows us to quantify not only propulsion forces but also radial displacement fields and cavity geometry around the robot, which are directly linked to soil disturbance, potential reduction in bulk density and anchoring performance.

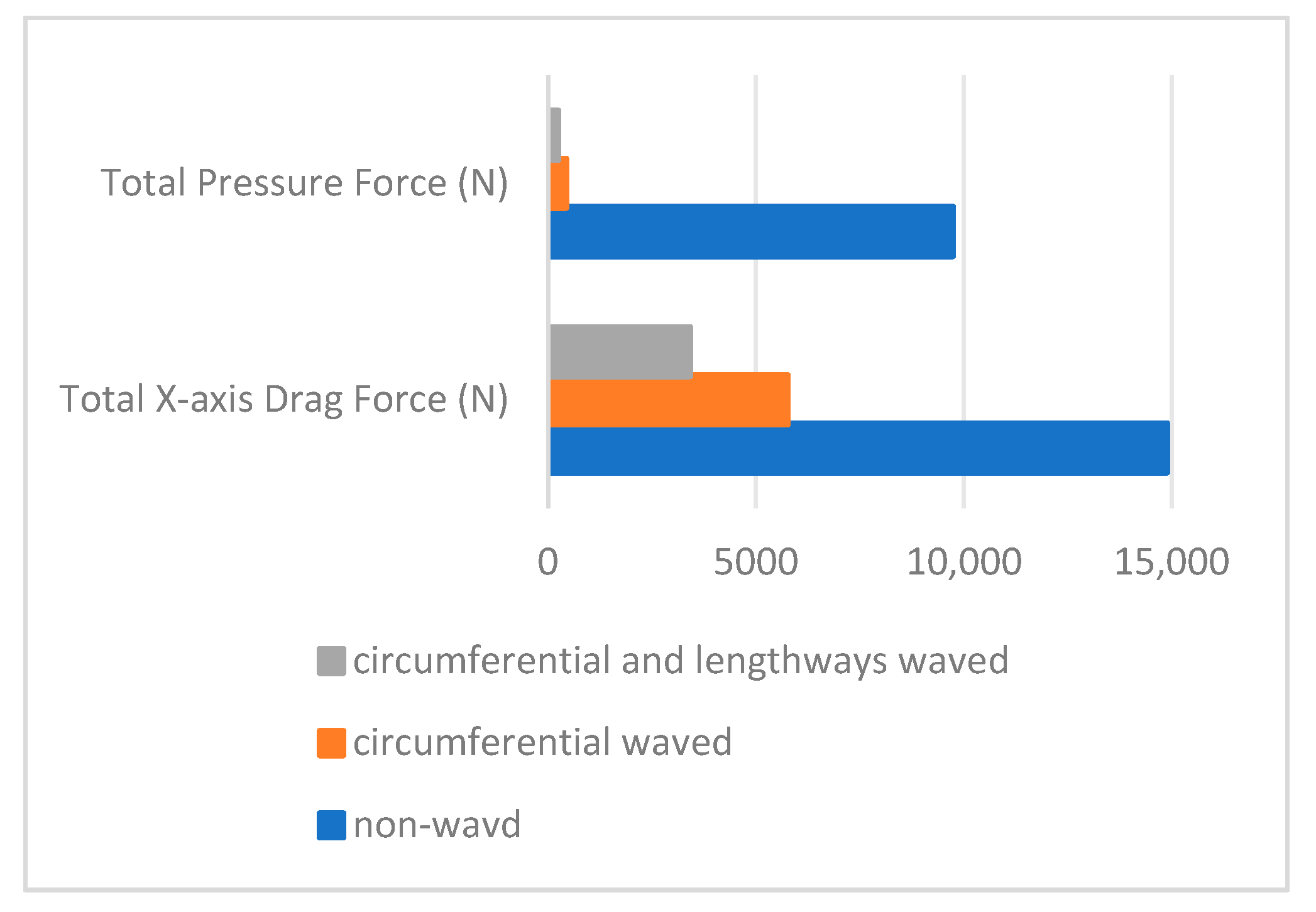

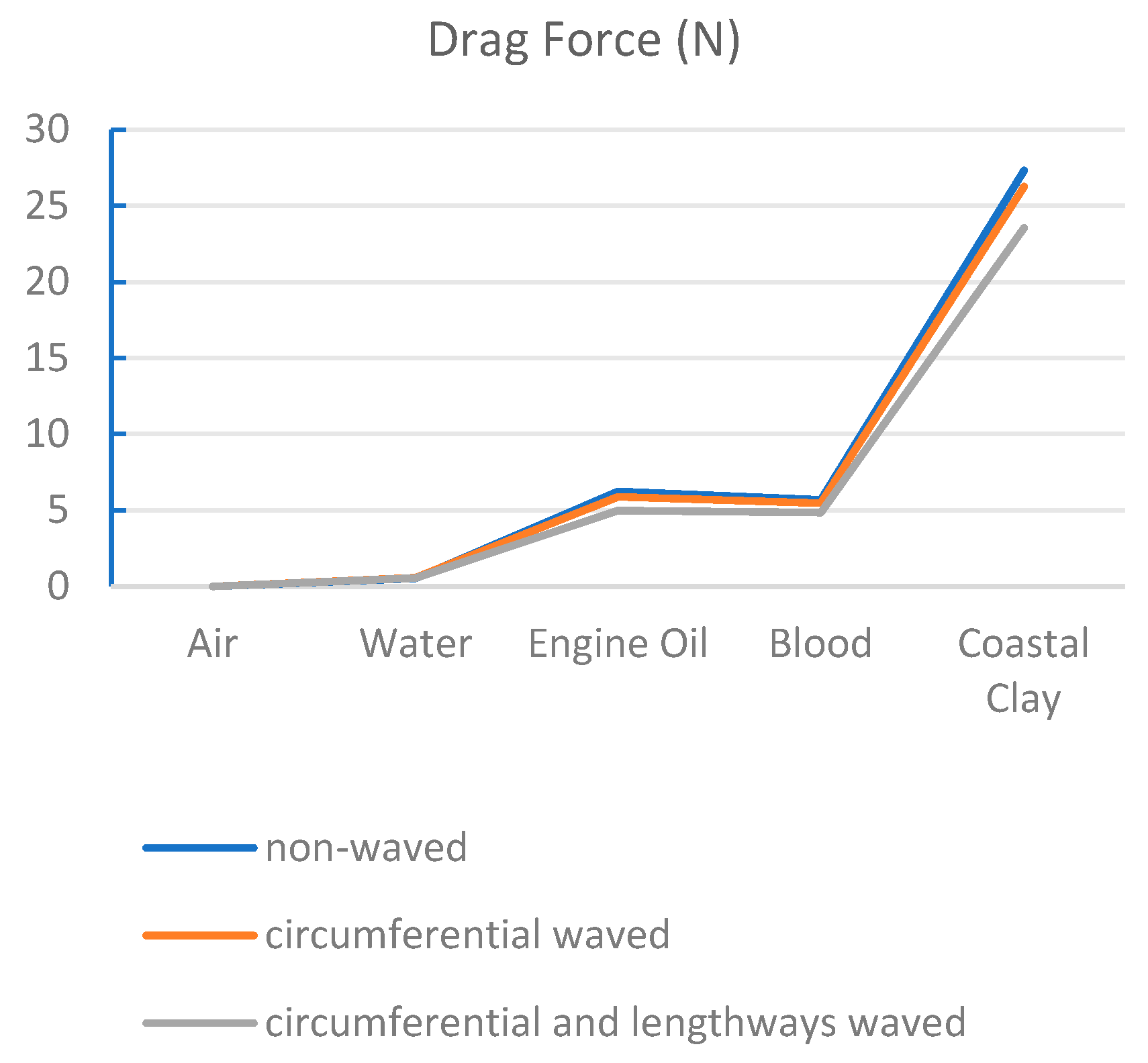

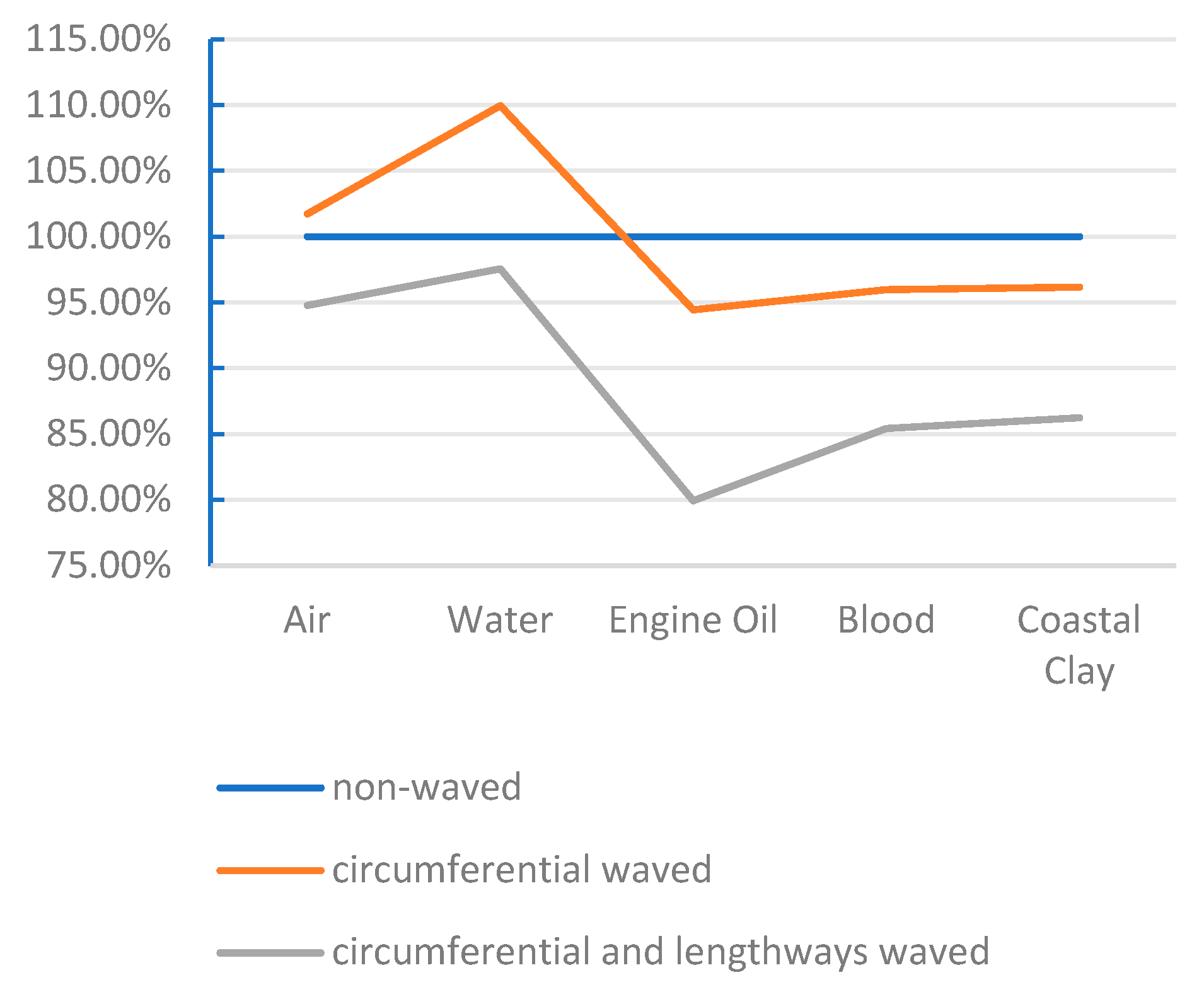

- We perform surface-geometry drag simulations in cohesive loam and in representative viscous media to assess how combined longitudinal–circumferential corrugations influence drag and contact forces relative to a smooth shell. These analyses clarify the conditions under which corrugated geometries can reduce drag by up to ~20% while maintaining sufficient normal contact for anchoring, and indicate how such trends may generalise across different high-viscosity environments.

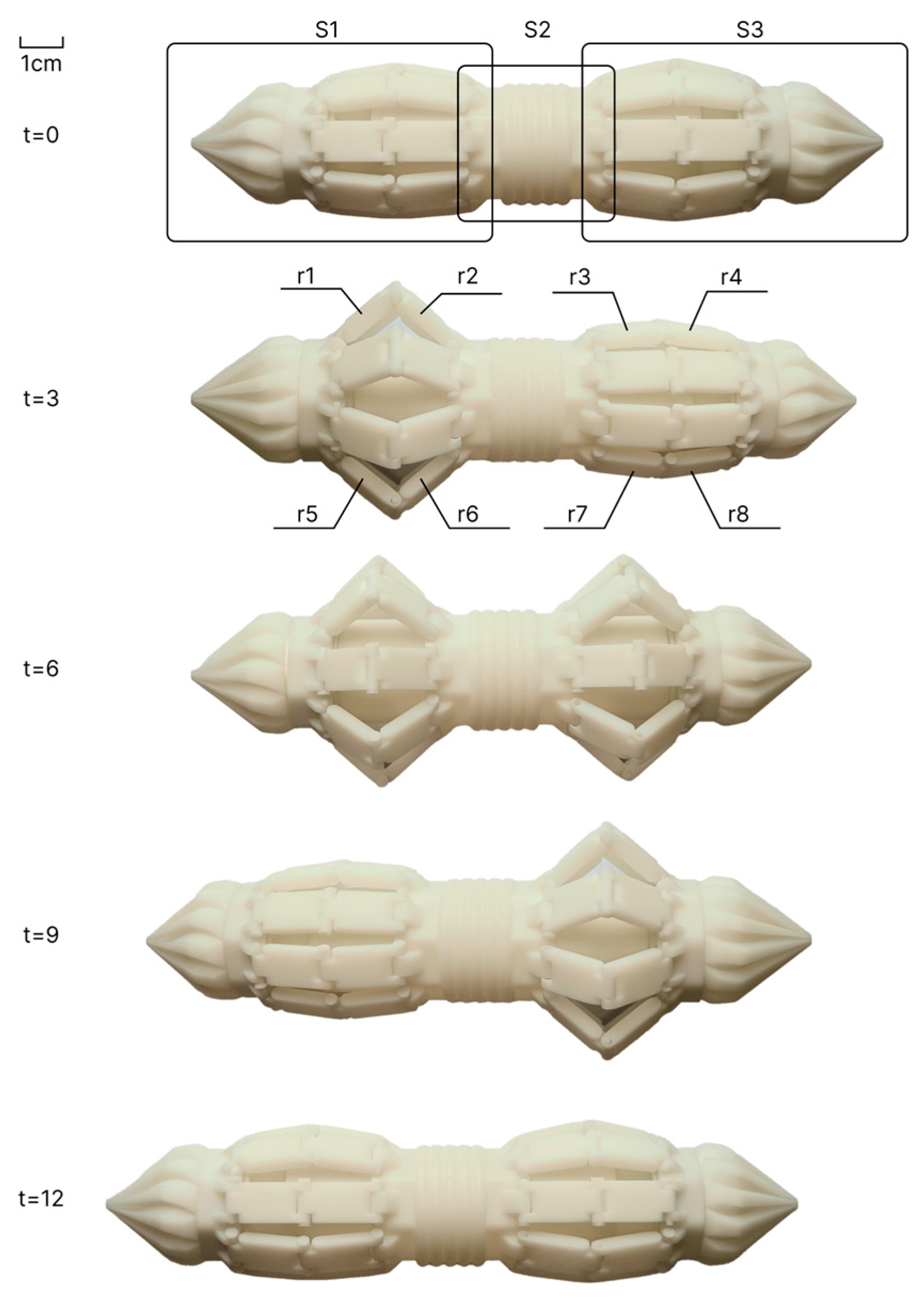

- We fabricate and test a bench-top prototype that realises the proposed peristaltic gait and brace-wire steering strategy. Experiments in a transparent tube demonstrate stable peristaltic motion and heading change, and show that the measured forward displacement per cycle is consistent with the kinematic predictions. Although these tests are conducted in a low-resistance environment, they provide an initial physical proof of concept for the rigid multi-link architecture and its potential for low-disturbance subsurface loosening.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Earthworm-Inspired Design Principles

2.1.1. Earthworm Body Structure and Peristaltic Locomotion

2.1.2. Earthworm-Inspired Engineering Design Principles

- P1: Segmented body architecture and anchoring–propulsion cycle

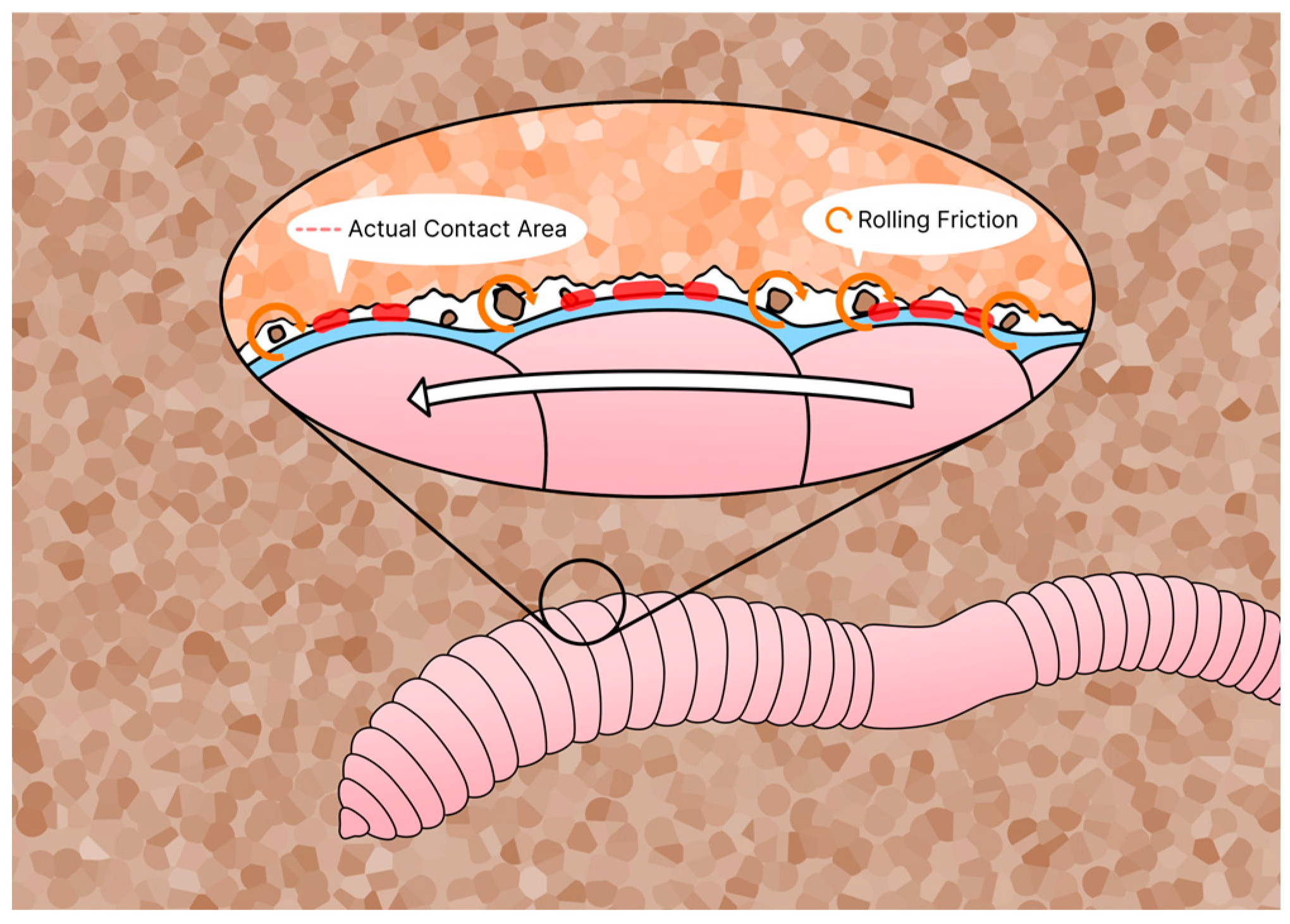

- P2: Corrugated body surface and drag reduction

- P3: Local asymmetric deformation and steering

2.2. Robotic Concept and Mechanical Design for Subsurface Loosening

2.2.1. Overall Concept and Target Working Conditions

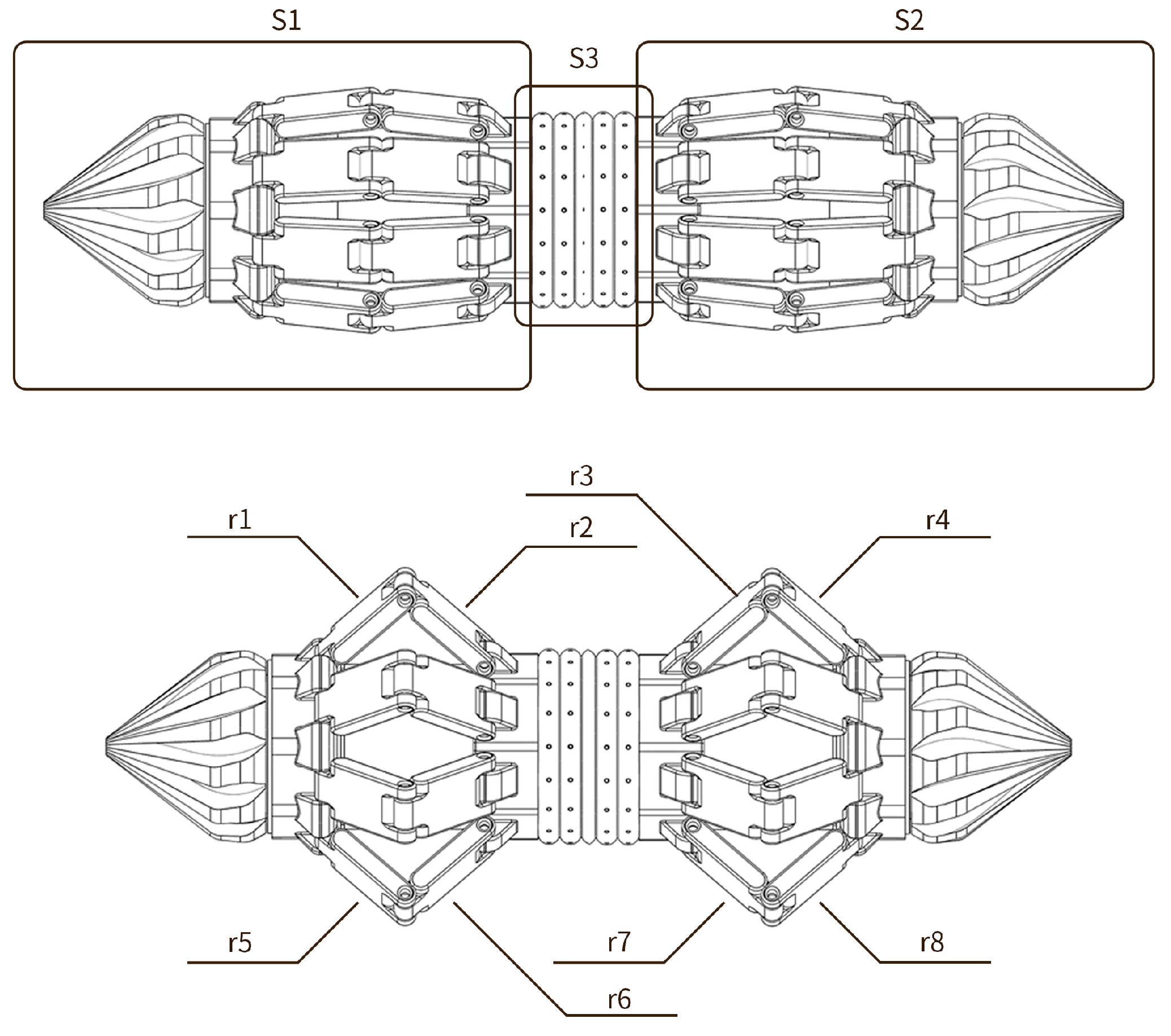

2.2.2. Segmented Body Architecture

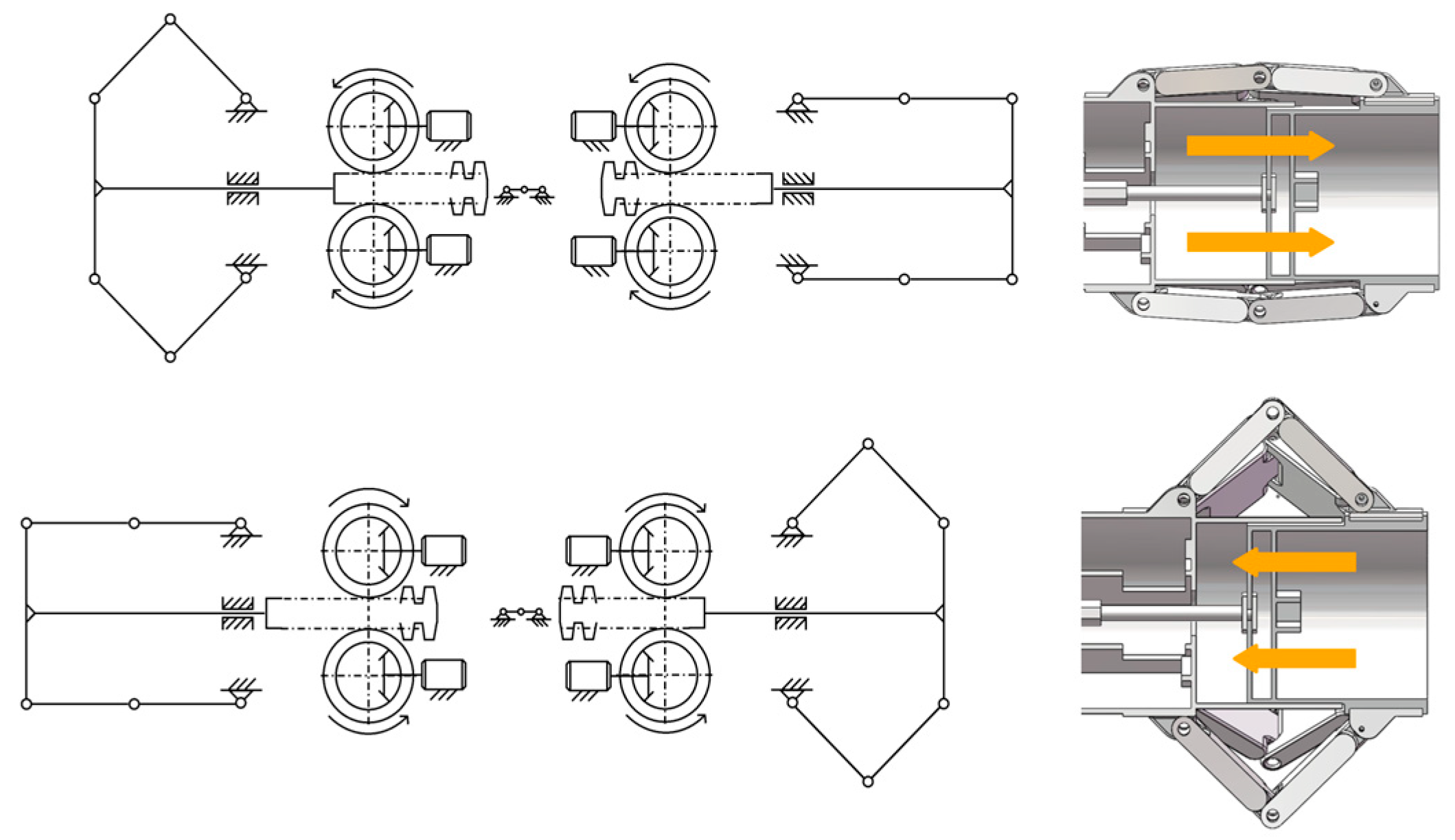

2.2.3. Peristaltic Actuation Mechanism and Telescopic Units

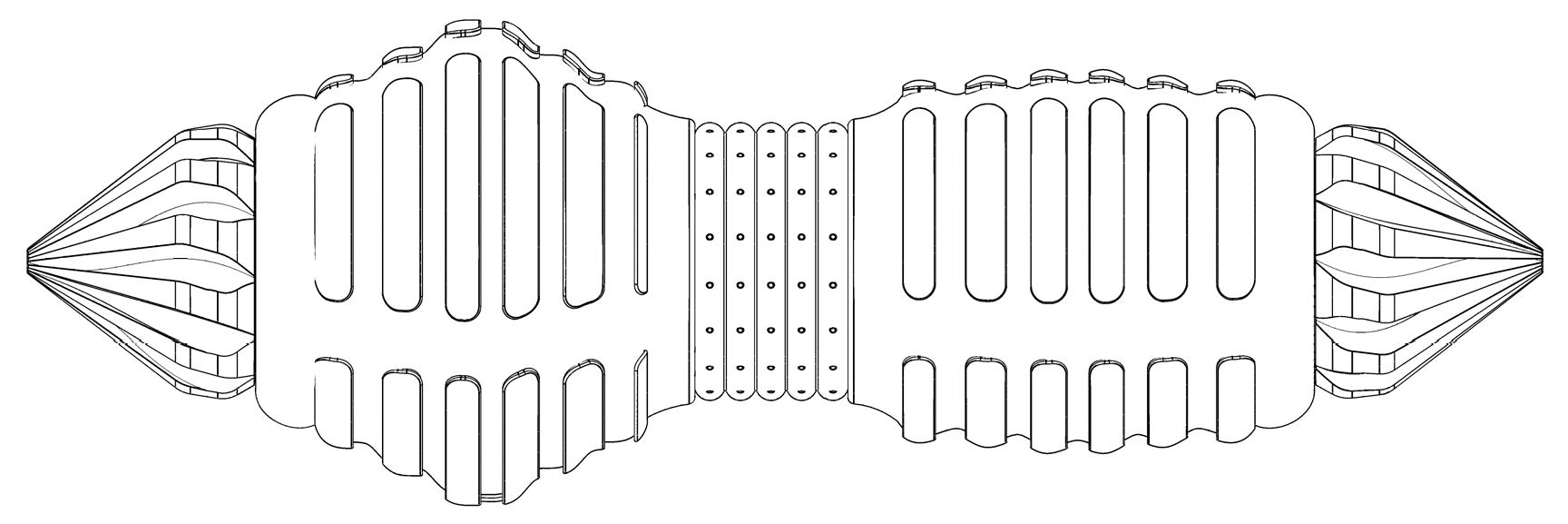

2.2.4. Corrugated Outer Shell and Central Service Channel

2.2.5. Brace-Wire Steering Mechanism

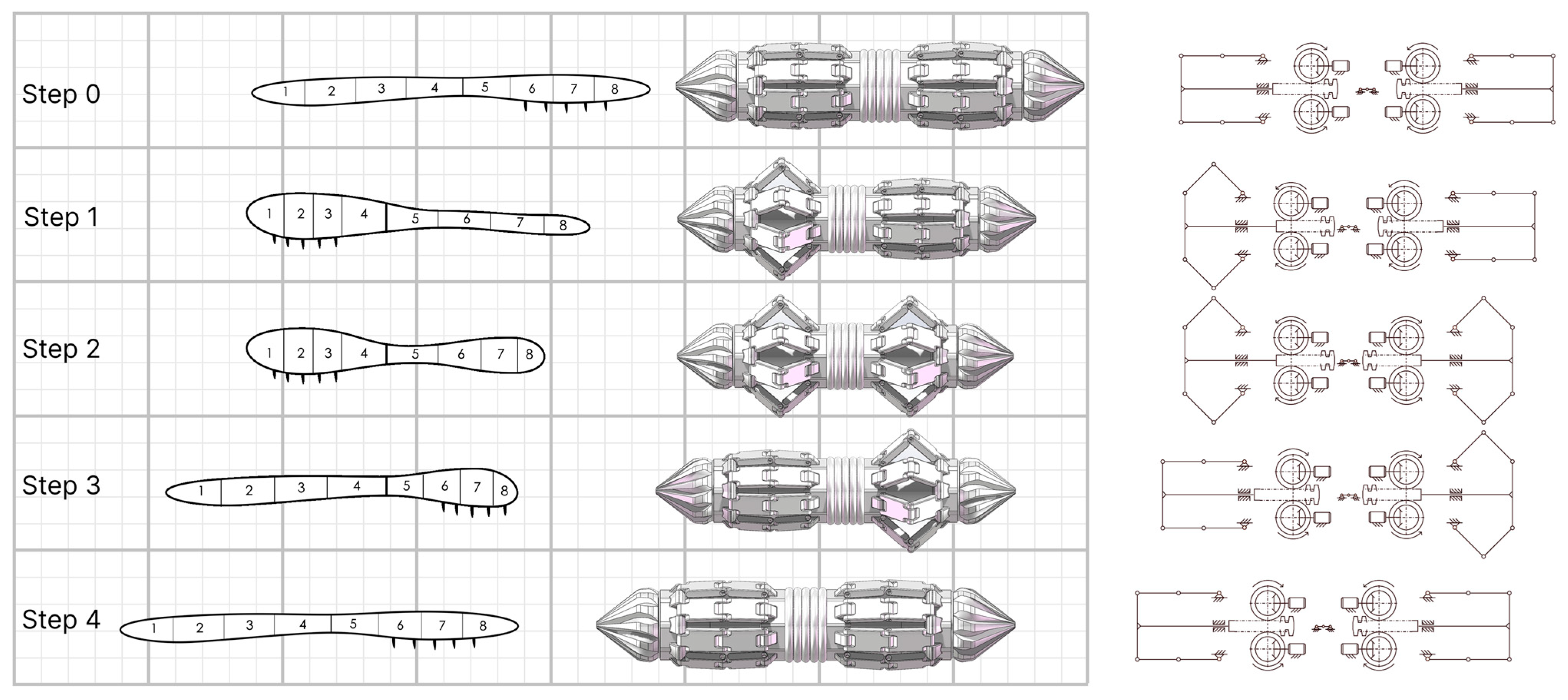

2.2.6. Typical Operation Workflow

2.3. Modelling of Robot–Soil Interaction

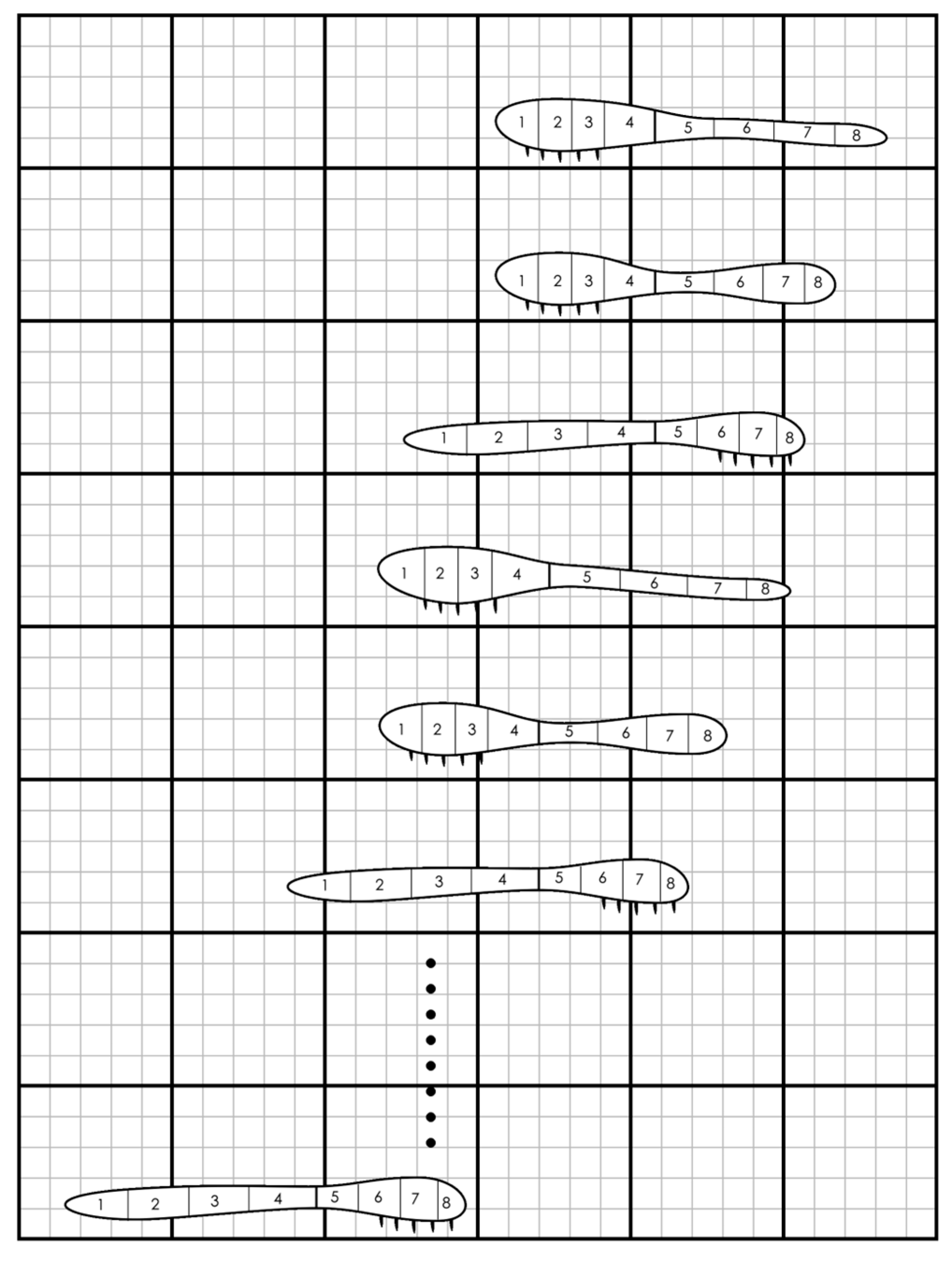

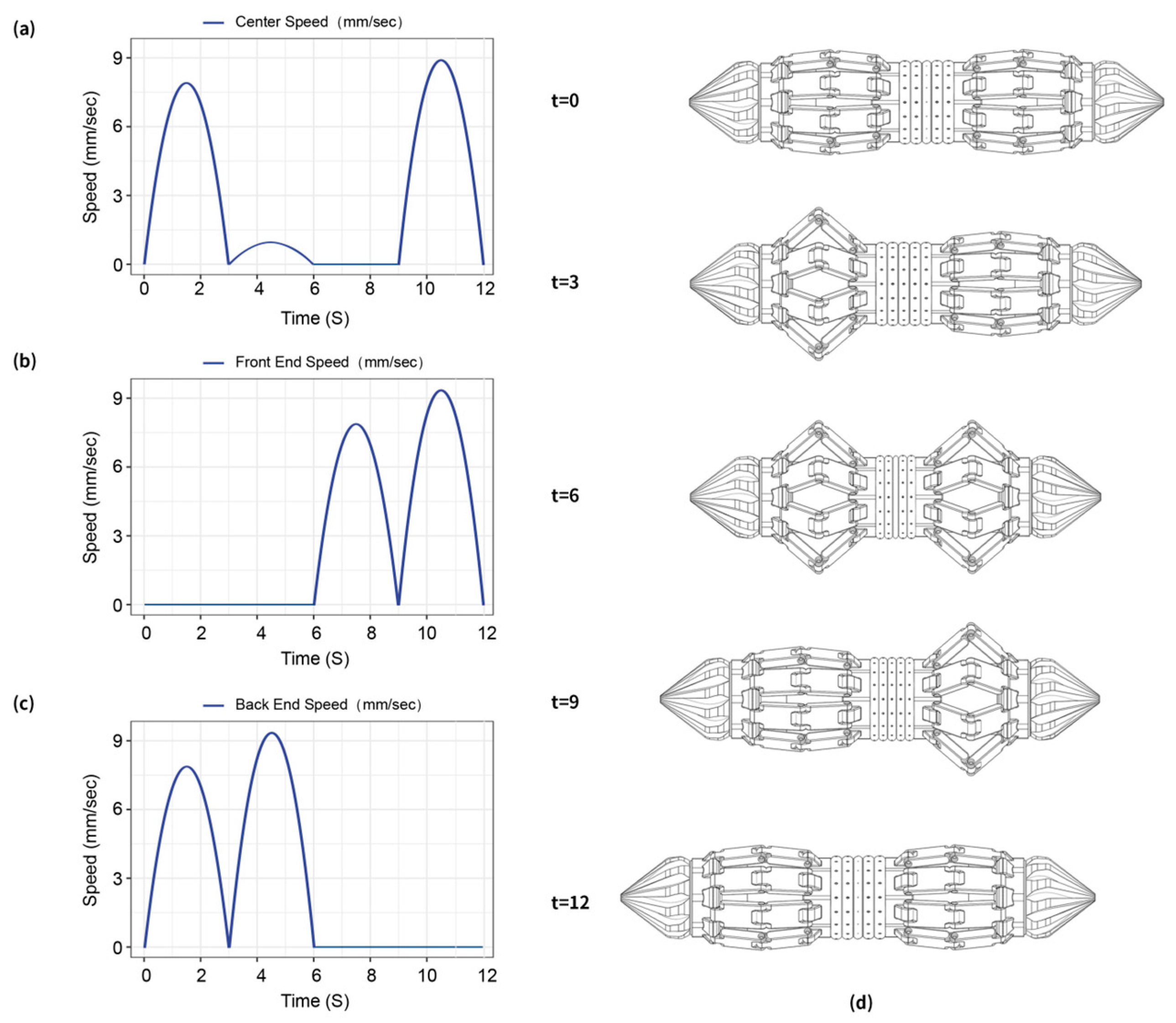

2.3.1. Kinematic Simulation

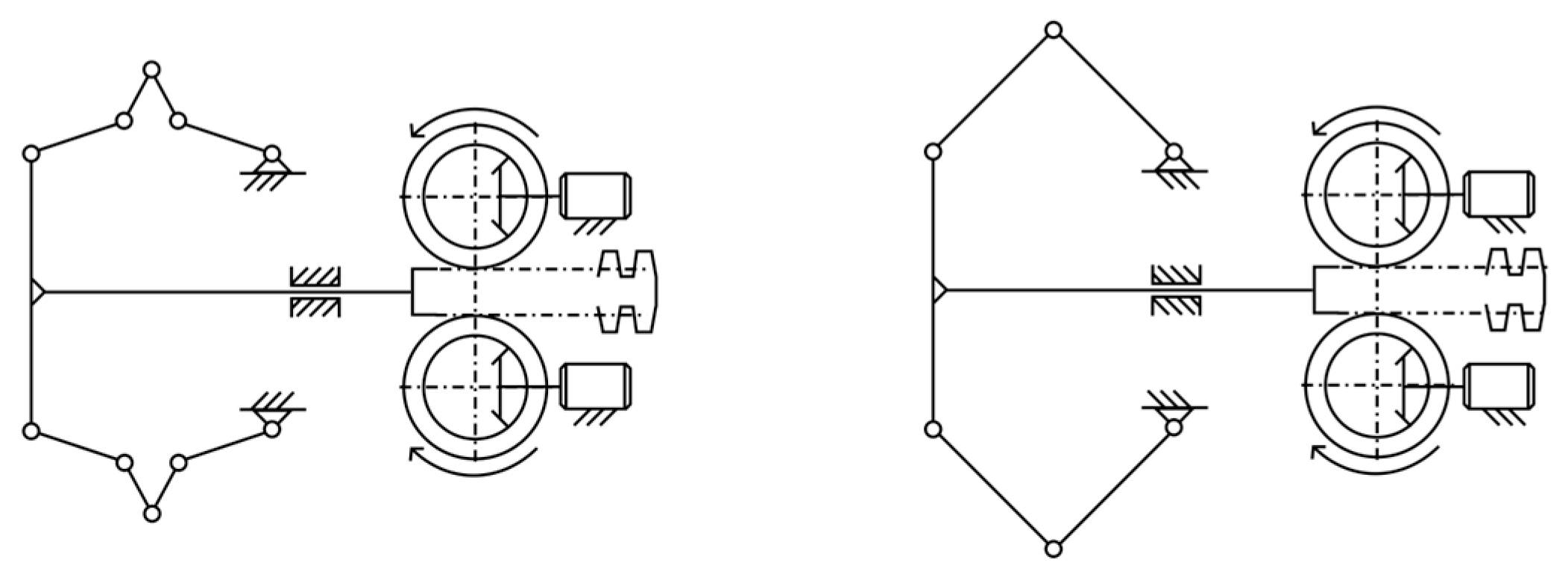

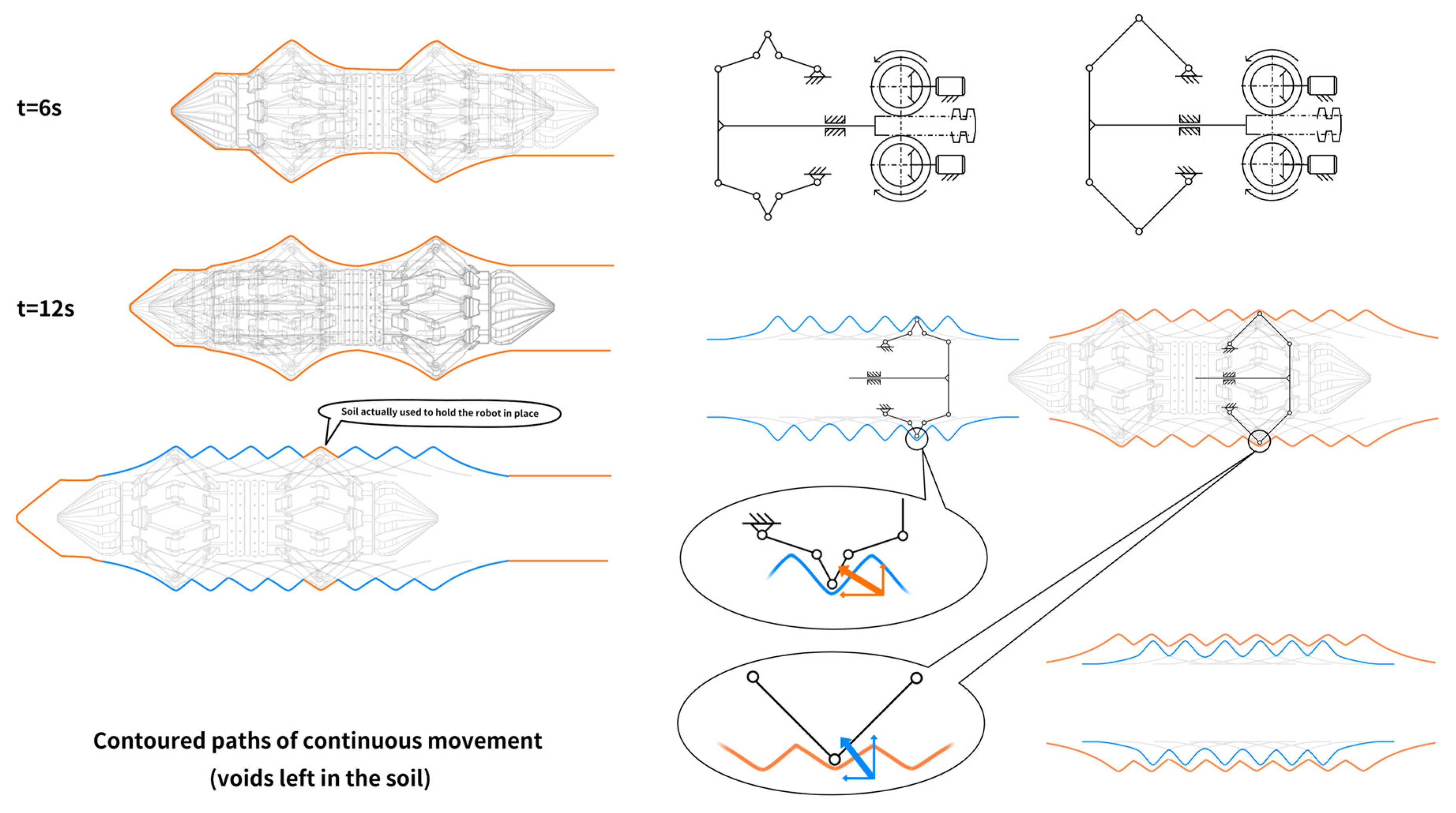

2.3.2. Linkage Layouts and Radial Soil Displacement

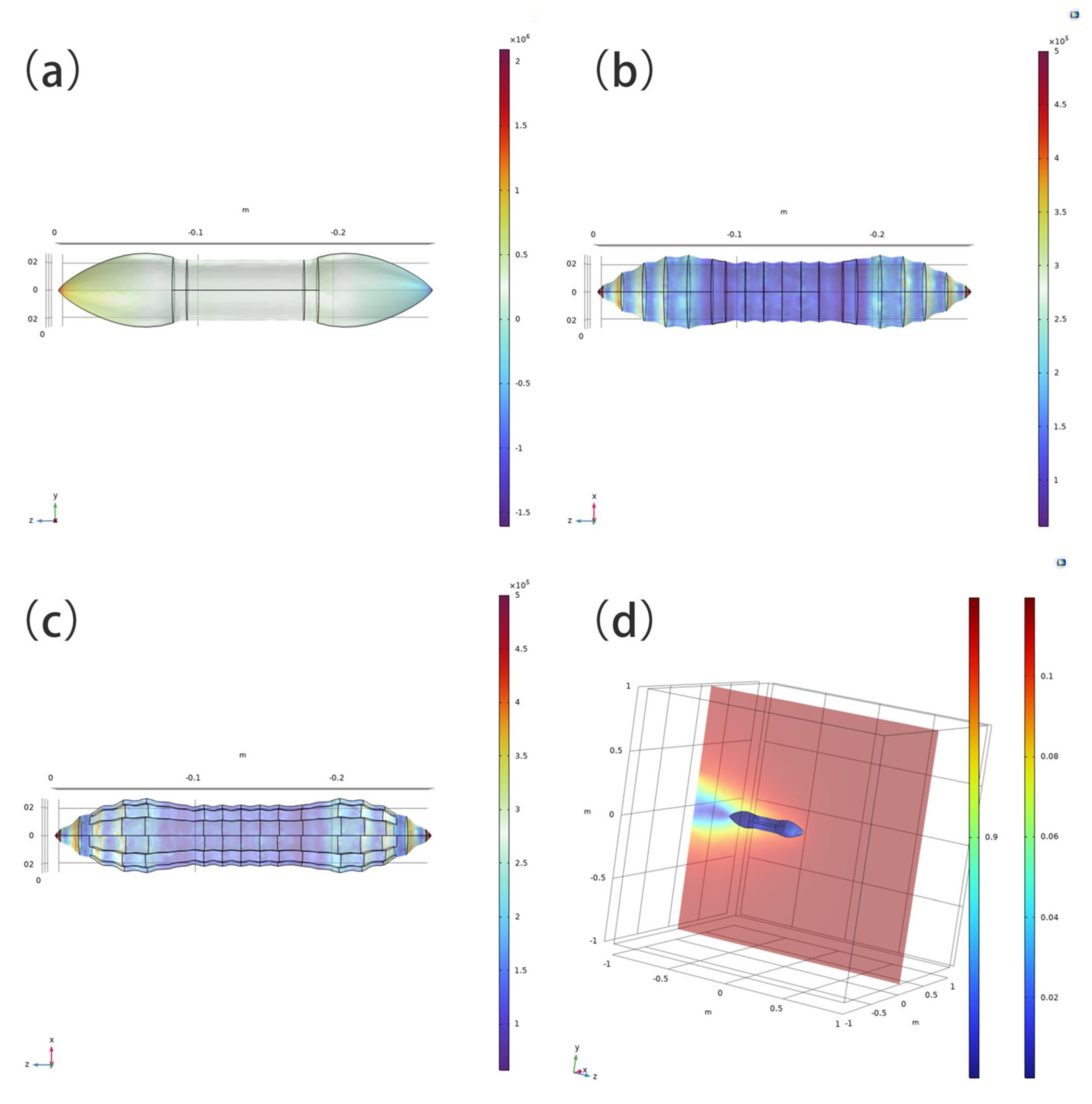

2.3.3. Outer-Shell Geometry and Drag Force in Soil

2.3.4. Drag-Force Analysis in Viscous Media

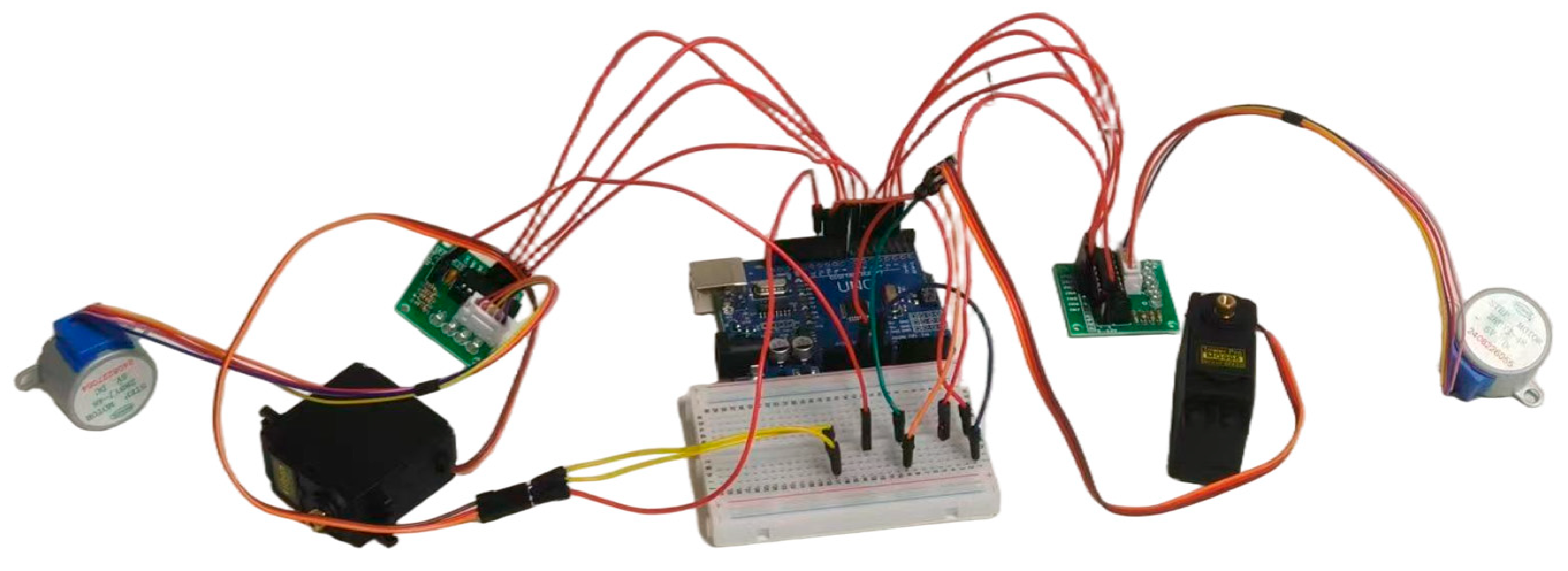

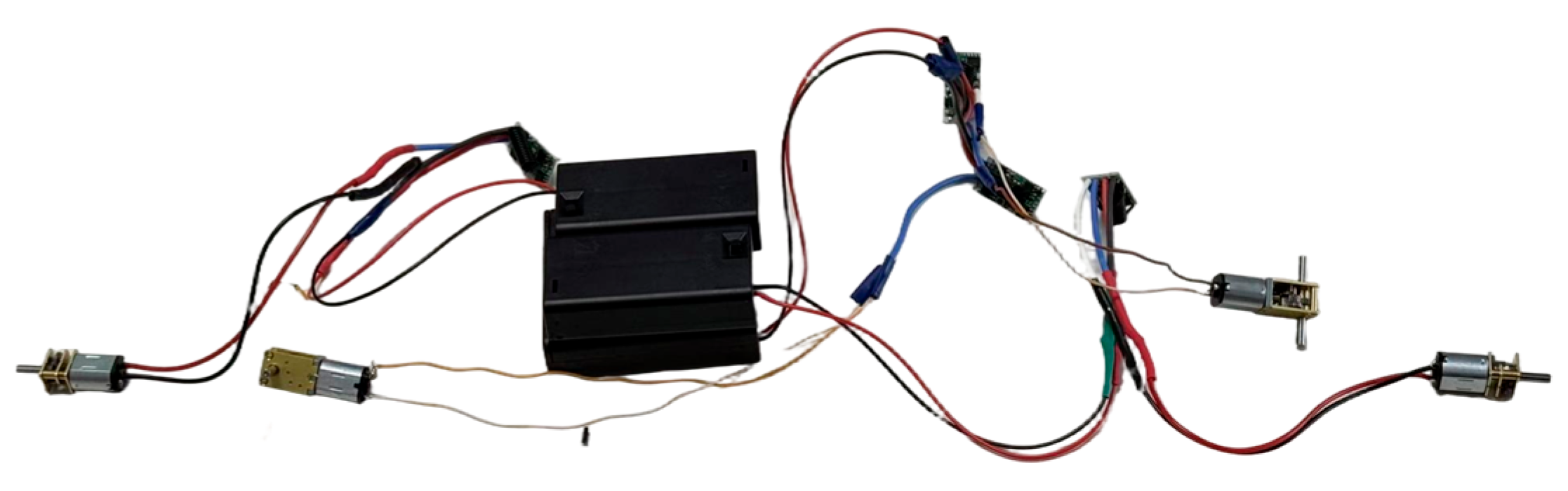

2.4. Prototype Fabrication and Control System

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Peristaltic Locomotion Simulation

3.2. Effect of Structural Optimisation on Soil Disturbance

3.3. Drag Reduction in the Corrugated Surface in Soil and High-Viscosity Media

3.3.1. Drag Reduction in Elastoplastic Loam

3.3.2. Adaptability and Maximum Drag Reduction in High-Viscosity Media

3.4. Prototype Locomotion and Steering Experiments

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Grassland Soil Compaction and Conservation Agriculture

4.2. Complementarity with Conventional Deep Tillage and Coring

4.3. Design Trade-Offs: Thrust, Drag Reduction, Disturbance and Manufacturability

4.4. Limitations of the Present Work

4.5. Future Research: From Soil-Bin Experiments to Field Applications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Akiyama, T.; Kawamura, K. Grassland degradation in China: Methods of monitoring, management and restoration. Grassl. Sci. 2007, 53, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlier, L.; Rotar, I.; Vlahova, M.; Vidican, R. Importance and functions of grasslands. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. 2009, 37, 25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Bardgett, R.D.; Bullock, J.M.; Lavorel, S.; Manning, P.; Schaffner, U.; Ostle, N.; Chomel, M.; Durigan, G.; Fry, E.L.; Johnson, D.; et al. Combatting global grassland degradation. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2021, 2, 720–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, M.F.; Bourrié, G.; Trolard, F. Soil compaction impact and modelling: A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 33, 291–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; Whalley, W.R.; Zhou, H.; Ren, T.; Gao, W. Does no-tillage mitigate the negative effects of harvest compaction on soil pore characteristics in Northeast China? Soil Tillage Res. 2023, 233, 105787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Kheir, A.S.M.; Ali, O.A.M.; Hafez, E.M.; ElShamey, E.A.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, B.; Lin, X.; Ge, Y.; Fahmy, A.E.; et al. A vermicompost and deep tillage system to improve saline-sodic soil quality and wheat productivity. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 277, 111388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Archibong, G.; Sunday, E.; Akudike, J.; Okeke, O.C.; Amadi, C. A review of the principles and methods of soil stabilization. Int. J. Adv. Acad. Res. Sci. 2020, 6, 2488–9849. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Su, H. Experimental study of complex coupled deep tillage mechanism and drag reduction. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinari, S.; Masciandaro, G.; Ceccanti, B.; Grego, S. Influence of organic and mineral fertilisers on soil biological and physical properties. Bioresour. Technol. 2000, 72, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, K.; Xu, H.-L. Properties and applications of an organic fertilizer inoculated with effective microorganisms. J. Crop Prod. 2001, 3, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blouin, M.; Hodson, M.E.; Delgado, E.A.; Baker, G.; Brussaard, L.; Butt, K.R.; Dai, J.; Dendooven, L.; Peres, G.; Tondoh, J.E.; et al. A review of earthworm impact on soil function and ecosystem services. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2013, 64, 161–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, R.; Babu, S.P.M.; Visentin, F.; Palagi, S.; Mazzolai, B. An earthworm-like modular soft robot for locomotion in multi-terrain environments. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, K. Origami-based earthworm-like locomotion robots. Bioinspir. Biomim. 2017, 12, 065003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newell, G. The role of the coelomic fluid in the movements of earthworms. J. Exp. Biol. 1950, 27, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Chen, Y.; Ma, Y.; Guo, L.; Sun, J.; Tong, J. Earthworm epidermal mucus: Rheological behavior reveals drag-reducing characteristics in soil. Soil Tillage Res. 2016, 158, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.Q.; Fan, T.X.; Mou, J.G.; Jiang, L.F.; Wu, D.H.; Zheng, S.H. A review of bionic technology for drag reduction based on analysis of abilities of the earthworm. Int. J. Eng. Res. Afr. 2015, 19, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daltorio, K.A.; Boxerbaum, A.S.; Horchler, A.D.; Shaw, K.M.; Chiel, H.J.; Quinn, R.D. Efficient worm-like locomotion: Slip and control of soft-bodied peristaltic robots. Bioinspir. Biomim. 2013, 8, 035003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón, A.A.; Ugalde, J.C.; Chang, L.; Zagal, J.C.; Pérez-Arancibia, N.O. An earthworm-inspired soft robot with perceptive artificial skin. Bioinspir. Biomim. 2019, 14, 056012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quillin, K.J. Kinematic scaling of locomotion by hydrostatic animals: Ontogeny of peristaltic crawling by the earthworm Lumbricus terrestris. J. Exp. Biol. 1999, 202, 661–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, J.; Lissmann, H. Studies in animal locomotion: VII. Locomotory reflexes in the earthworm. J. Exp. Biol. 1938, 15, 506–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaka, K.; Tsumura, K.; Watanabe, T.; Toyama, W.; Sugesawa, M.; Yamada, Y.; Yoshida, H.; Nakamura, T. Development of underwater drilling robot based on earthworm locomotion. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 103127–103141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangan, E.V.; Kingsley, D.A.; Quinn, R.D.; Chiel, H.J. Development of a peristaltic endoscope. In Proceedings of the 2002 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Washington, DC, USA, 11–15 May 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Le, T.-A.; Alabay, H.H.; Singh, P.G.; Austin, M.G.; Misra, S.; Ceylan, H. Fluoroscopic-guided magnetic soft millirobot for atraumatic endovascular drug delivery. bioRxiv 2025. bioRxiv:2025.02.17.637470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munda, J.; Pradhan, P.K.; Nayak, A.K. A review on the performance of Modified Cam Clay model for fine grained soil. J. Civ. Eng. Environ. Technol. 2014, 1, 65–71. [Google Scholar]

- Roscoe, K.H. The influence of strains in soil mechanics. Géotechnique 1970, 20, 129–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rus, D.; Tolley, M.T. Design, fabrication and control of soft robots. Nature 2015, 521, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galloway, K.C.; Becker, K.P.; Phillips, B.; Kirby, J.; Licht, S.; Tchernov, D.; Wood, R.J.; Gruber, D.F. Soft robotic grippers for biological sampling on deep reefs. Soft Robot. 2016, 3, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, N.; Larsbo, M. Macropores and macropore flow. In Reference Module in Earth Systems and Environmental Sciences; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Stroppa, F.; Majeed, F.J.; Batiya, J.; Baran, E.; Sarac, M. Optimizing soft robot design and tracking with and without evolutionary computation: An intensive survey. Robotica 2024, 42, 2848–2884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| System | Structure and Actuation | Key Aspects vs. This Work |

|---|---|---|

| Das et al., 2023 [12] | Soft modular body, pneumatic chambers + tendons | Soft, externally pressurised; not aimed at compacted soils or root-zone loosening |

| Fang et al., 2017 [13] | Origami-like thin-film segments, embedded actuators | Focus on deployable origami body; no soil-compaction or energy analysis |

| Daltorio et al., 2013 [17] | Segmented robot with rigid frames and compliant skins | Studies peristaltic gaits, but not grassland soil or turf preservation |

| Calderón et al., 2019 [18] | Soft body with artificial skin and sensing | Emphasis on soft morphology and perception, not high-resistance agricultural soils |

| This work | Rigid-link telescopic segments + corrugated shell, motor-driven mechanism | Rigid, industry-oriented architecture that uses linkages to mimic earthworm musculature and chaetae for low-disturbance subsurface loosening; drag trends are studied as a basis for future deep-buried soil tests and industrial deployment of earthworm-inspired robots |

| Soil Parameters | |

|---|---|

| Particle Density | 2.65 g/cm3 |

| Wet Density | 1.8 g/cm3 |

| Poisson’s Ratio | 0.48 |

| Swelling Index | 0.03 |

| Compression Index | 0.2 |

| Void Ratio at Reference Pressure | 0.7 |

| Slope of Critical State Line | 0.15 |

| Young’s Modulus | 5 MPa |

| Cohesion | 50 KPa |

| Angle of Internal Friction | 20° |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cai, Y.; Liu, S. An Earthworm-Inspired Subsurface Robot for Low-Disturbance Mitigation of Grassland Soil Compaction. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010115

Cai Y, Liu S. An Earthworm-Inspired Subsurface Robot for Low-Disturbance Mitigation of Grassland Soil Compaction. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):115. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010115

Chicago/Turabian StyleCai, Yimeng, and Sha Liu. 2026. "An Earthworm-Inspired Subsurface Robot for Low-Disturbance Mitigation of Grassland Soil Compaction" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010115

APA StyleCai, Y., & Liu, S. (2026). An Earthworm-Inspired Subsurface Robot for Low-Disturbance Mitigation of Grassland Soil Compaction. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010115