Abstract

This scoping review aimed to map and synthesize the scientific evidence on how lifestyle factors and quality of life are associated with the onset and progression of non-carious diseases (NCDs) in young and adult populations, identifying patterns, methodological characteristics, and gaps in the existing literature. A systematic literature search was conducted across PubMed, Embase, Scopus, and Web of Science databases to retrieve studies evaluating the influence of lifestyle habits and quality of life indicators on NCDs development and worsening. Most included studies were conducted in Brazil, with cross-sectional designs being the most prevalent. The main modulating factors identified included gastroesophageal reflux, post-bariatric conditions, smoking, bruxism, and anxiety. The results were summarized through a descriptive narrative synthesis. Considerable methodological heterogeneity was observed, particularly due to the absence of standardized protocols for NCDs assessment. Methodological quality was also evaluated to contextualize the robustness of the available evidence. Overall, lifestyle and quality of life factors play an important role in the progression of NCDs, underscoring the need for their integration into diagnostic and therapeutic planning. Further clinical studies are warranted to deepen the understanding of the relationship between NCDs and broader health domains, with particular attention to early oral aging syndrome (EOAS).

1. Introduction

Non-carious cervical lesions (NCCLs) began to receive more scientific attention in 1991, when the study entitled “Abfractions: A New Classification of Hard Tissue Lesions of Teeth”, summarized NCCLs as a type of abfraction lesion resulting from biomechanical stress forces acting on the tooth structure [1]. Another term frequently used in the literature is erosive wear or dental erosion, also scientifically referred to as tooth wear [2]. However, this terminology has gradually fallen out of favor with the emergence of newer classifications [3].

Over the decades, further studies were conducted, until defined non-carious diseases (NCDs) were defined as oral conditions of non-bacterial origin that are intrinsically associated with individual habits, lifestyle, and quality of life [3]. The term NCD is based on a specific conceptual framework. The study in question describes NCDs as a group comprising non-carious lesions (NCLs), dentin hypersensitivity (DH), gingival recession (GR), fractures/cracks, and pulpal damage (PD) [3]. In cases of pulpal damage, ischemia, calcification, or necrosis may be observed. GR may be associated with the occurrence of bone resorption. NCLs are more commonly found and related on the cervical surface but may also occur on the occlusal, incisal, palatal, or buccal surfaces. DH affects the cervical, palatal, buccal, occlusal, or incisal surfaces. Finally, fractures or cracks can be observed in the enamel or dentin [3,4,5].

The application of anamnesis is an essential component in the diagnostic process and in dental treatment planning, enabling the clinician not only to identify the patient’s chief complaints but also to understand the broader context of their overall health. A detailed anamnesis, including an investigation of daily habits and lifestyle factors such as diet, physical activity, and even sleep quality, is crucial for identifying risk factors that may impact oral health. This practice is particularly relevant to help in the diagnosis of NCDs, which are frequently associated with behavioral factors, thereby reinforcing the need for a holistic approach. In this way, anamnesis guides the selection of the most appropriate therapeutic interventions, promoting comprehensive health and preventing the progression of conditions that may compromise the patient’s quality of life [3,4,5].

The Early Oral Aging Syndrome (EOAS) is a term used to describe individuals whose oral cavity exhibits pathological signs of accelerated aging that are inconsistent with their physiological age. These individuals present with a mouth free of bacterial plaque accumulation but with clinical features that deviate from what is considered normal. This syndrome arises from a combination of multiple factors associated with NCDs and can be classified into four levels or stages: EOAS-0, EOAS-1, EOAS-2, and EOAS-3. Among these, EOAS-1 is the only stage considered reversible [3,4,5]. When analyzing the behavior of NCDs, their occurrence is often found to be correlated with the presence of gastric diseases, temporomandibular disorders, orofacial pain, psychiatric/psychological disorders, sleep disturbances, and dietary habits. In other words, the patient’s lifestyle and specific habits play a modulatory role in the development of NCDs [3,4,5,6].

In this context, risk groups and contributing factors for these conditions, and for the potential development of EOAS, can be identified and described as correlated. These include: moderate to severe anxiety disorders, individuals with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), former orthodontic appliance users, individuals who use electronic smoking devices (ESDs), presence of awake and/or sleep bruxism, as well as the use of illicit substances or corrosive medications, pharmacological treatment for anxiety and ADHD, high-performance athletes, individuals following an acidic or sport-specific diet, burnout syndrome, excessive occupational demands, double work shifts, and individuals with other psychiatric disorders. Additional associated conditions include gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), mouth breathing, bulimia, anorexia, post-bariatric surgery patients, salivary alterations, and individuals with molar-incisor hypomineralization (MIH) [3,4,5,6,7,8,9].

Thus, this exploratory review aimed to map and synthesize the scientific evidence on how lifestyle factors and quality of life are associated with non-carious diseases in young and adult populations, identifying patterns, methodological characteristics, and gaps in the existing literature.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

This review was not registered in a formal protocol prior to its development. Nevertheless, the entire process was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) and the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) methodological guidance. No substantial methodological changes were made after the initiation of the review. The research question, eligibility criteria, search strategy structure, and analytical procedures adhered to the steps originally defined by the research team. Minor operational adjustments, such as refining search terms within specific databases and expanding gray literature sources, were made solely to improve retrieval precision and did not alter the scope or objectives of the review.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

Technical and scientific publications that discussed the influence of lifestyle and the progression of NCDs, considering individuals’ and/or groups’ specific habits and related risk factors, were considered eligible. Articles characterized solely as clinical or therapeutic protocols, laboratory-based studies, ex vivo or animal studies, as well as texts that did not align with the study scope or did not address a young or adult population, were excluded.

2.3. Information Sources

This study is a scoping review addressing how lifestyle and quality of life influence the onset and progression of NCDs. This type of systematic literature review enables a broad analysis of bibliographic productions, generating a narrative that enhances the understanding of existing research and the proposed topic [10]. To ensure methodological rigor, the checklist from the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses–Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) was followed (Table S1).

The research question was formulated using the Population, Concept, and Context (PCC) framework. In this review, the Population, initially defined as “young adults,” was operationalized with flexibility because many relevant studies included broader age ranges. Thus, studies involving young and adult populations were included when they contributed evidence to the topic. The Concept encompassed non-carious diseases (including dental erosion, dental wear, tooth wear, non-carious lesions, non-carious cervical lesions and similar) and their relationships with lifestyle and quality of life. The Context included community-based, outpatient, and population-based settings, without geographic restrictions, to reflect real-world conditions under which NCDs develop.

Accordingly, the research question guiding this review was:

“What has the scientific literature reported on the influence of lifestyle and quality of life in young and adult populations as modulatory factors of non-carious diseases?”

2.4. Search Strategy

The databases selected to identify scientific and technical literature related to the topic were: PubMed, Embase, Scopus, and Web of Science. Additional databases such as Cochrane Library, LILACS and SciELO were not included because exploratory searches indicated minimal contribution of these sources to the identification of primary studies relevant to the topic. The Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) vocabulary was used to identify the main descriptors: “non carious disease,” “quality of life,” and “young adult.” Search terms and their synonyms were combined using the Boolean operators “AND” and “OR” to construct search expressions tailored to each of the selected databases (Table S2).

The search strategy was conducted in February 2024. Being constantly updated during the writing of the study until December 2025, in order to analyze possible new articles that contemplate the scope of the review. The identified scientific and technical records were exported to the Zotero reference manager. Duplicate records were automatically removed and then manually reviewed by the authors for additional deduplication.

2.5. Selection Process

The article selection process was conducted independently and duplicated by two individual researchers (RSTF and GMTP), based on the established eligibility criteria. Initially, studies were screened by title. In the second phase, abstracts were reviewed, followed by the full-text screening in the final phase. All discrepancies were discussed and resolved by the reviewers, and a third reviewer (PVS) was consulted when necessary to reach consensus.

2.6. Data Extraction

Two summary tables were developed to extract and organize the most relevant information from each article. The items extracted for Table 1 included general publication data (author and year), study characteristics (study design, country of origin, age and gender of the population studied, number of participants, and total sample size), as well as methods used to analyze risk factors and NCDs. For Table 2, the extracted data included general publication information (author and year), the groups of NCDs analyzed, associated modulatory risk factors, and a brief summary of each article.

Table 1.

General characteristics of the studies included in the review, detailing author, year of publication, study design, country, age group, gender distribution, number of participants, total sample size, and method of analysis.

Table 2.

Main findings of the eligible studies, including the non-carious diseases described, modulating factors, and a summary of the key results.

2.7. Data Mapping Process

Data extraction was performed independently by two individual reviewers (RSTF and GMTP) using pre-designed and pilot-tested forms developed by the research team. These tools were calibrated to ensure consistency and minimize potential errors during data collection. In cases of disagreement, a third reviewer (PVS) was consulted to resolve discrepancies and reach consensus.

2.8. Data Items

The extracted variables included: (1) General study information: author, year of publication, and country of origin; (2) Characteristics of the analyzed population: age, gender, and sample size; (3) Study design: type of study and methods employed; (4) Identified modulating factors: lifestyle, habits, systemic and behavioral conditions; (5) Main findings: relationship between modulating factors and non-carious diseases.

When a given variable was not reported in the included studies, it was assumed to be absent.

2.9. Critical Appraisal of Individual Sources of Evidence

Although scoping reviews do not require a formal risk of bias assessment, we followed PRISMA-ScR and JBI guidance to describe the overall methodological quality of the included evidence. For this purpose, we conducted a structured appraisal of key methodological characteristics across all eligible studies.

This appraisal did not aim to generate individual risk-of-bias scores. Instead, it sought to identify recurring strengths and weaknesses that may influence the robustness of the synthesized evidence. The following domains were examined:

- Study design and level of evidence (e.g., cross-sectional, cohort, case–control).

- Sampling strategy, including use of convenience samples or unclear recruitment procedures.

- Sample representativeness, particularly regarding population diversity and clinical settings.

- Diagnostic criteria and outcome measurement, noting heterogeneity or lack of standardized methods.

- Calibration and training of examiners, when applicable.

- Potential sources of bias, such as recall bias, self-reported data, or limited adjustment for confounding factors.

- Overall clarity and completeness of reporting, following principles consistent with STROBE and JBI guidance.

The appraisal results were summarized narratively and tabulated to facilitate comparison across study designs. This descriptive methodological assessment guides the interpretation of the findings by clarifying the limitations that commonly affect observational research and by reinforcing that reported associations cannot be interpreted as causal relationships.

The data were organized into summary tables to facilitate the presentation and comparison of findings. The results were grouped according to the objectives of the review, with emphasis on modulating factors of non-carious diseases and their implications for quality of life. A qualitative analysis was conducted to identify relevant patterns and trends within the extracted data.

3. Results

3.1. Selection of Sources of Evidence

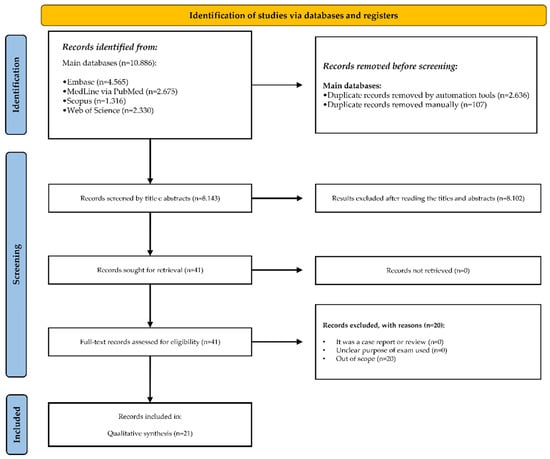

The search strategy yielded a total of 10.886 articles. During the selection process, 8.143 records were excluded based on title and abstract screening, resulting in 41 articles selected for full-text reading. Ultimately, 21 articles were deemed eligible for inclusion in the study. Figure 1 presents the PRISMA-ScR flowchart illustrating the identification and selection process of the studies.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart illustrating the identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion of studies in the review process.

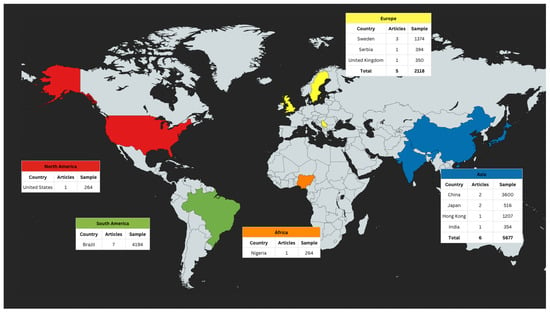

Details of the selected studies, including the analyzed population and the factors considered in the qualitative synthesis, are presented in Table 1 and Table 2. The MapChart (Figure 2) presents the distribution of publications and corresponding sample sizes across countries.

Figure 2.

Geographical distribution of the included studies and their corresponding sample sizes across countries, generated using MapChart.

3.2. Characteristics of the Sources of Evidence

3.2.1. General Characterization of the Studies Selected for Qualitative Synthesis

Most of the included studies were conducted in Brazil, and the most common study design among those selected for synthesis was cross-sectional. The analyzed populations were predominantly composed of young and adult individuals, particularly in the 18–45 age range. Among the evaluated groups of NCDs, DH, GR and NCLs were included, along with the various terminology alternatives reported in the scientific literature that have the same clinical meaning. However, conditions related to cracks/fractures and pulpal damage were not assessed. Of the 21 studies included in the analysis, 10 reported NCCLs or NCLs (47%), 5 mentioned dental erosion (25%), 7 addressed GR (35%), and 9 investigated DH (42%).

3.2.2. Association Between NCDs and Systemic and/or Surgical Conditions

The modulatory factors of NCDs, considered a possible risk factor for these conditions, generally do not act in isolation but rather exhibit interrelated patterns. Moreover, these modulatory factors, often linked to an individual’s lifestyle or quality of life, may originate from or be associated with systemic and/or surgical conditions. Examples include GERD and patients who have undergone bariatric surgery [13,24].

3.2.3. Association Between NCDs, Habits, Behaviors, and Socioeconomic Status

Lifestyle-related habits were also shown a possible association to influence the modulation of NCDs. For instance, smoking was reported in 7 out of the 20 studies included in the synthesis (35%). Behavioral and socioeconomic factors also emerged as significant modulators of NCDs. In 10 of the 21 studies (47%), conditions such as bruxism, anxiety, and socioeconomic status were identified as a possible influence to the prevalence of these conditions.

3.2.4. Association Between NCDs and the Absence of Standardized Assessment Protocols

Finally, the analysis revealed a lack of standardized protocols for the evaluation and diagnosis of NCDs. A wide range of clinical examination methods and questionnaires were reported for identifying risk and modulatory factors. These included instruments such as the Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP-14), Pain and Discomfort Questionnaires, Dietary and Behavioral Habit Questionnaires, BAI and Risk Assessment Tools. The absence of uniform methodologies contributes to variability in outcomes and limits the identification of consistent patterns among modulatory factors [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31].

3.3. Methodological Characteristics and Overall Quality of the Included Evidence

A descriptive methodological appraisal was performed across all included studies using the domains outlined in the Methods Section. The synthesis revealed substantial variability in study design, sample characteristics, and diagnostic approaches. Most studies were cross-sectional and relied on convenience sampling, which limits representativeness. Heterogeneity in diagnostic criteria and limited reporting of potential confounders were also observed in some studies.

3.4. Results of Individual Sources of Evidence

The data extracted from each included study is organized in summary tables (Table 1 and Table 2). The general characteristics of the studies included information such as author, year of publication, study design, country of origin, participants’ age and gender, sample size, and methods used for analysis. For example: Employed a cross-sectional design to assess the influence of bruxism and brushing frequency on NCCLs in a sample of 2160 individuals in China [12]. Investigated the association between smoking and NCCLs in a Brazilian population of 539 participants, using clinical methods and questionnaires [27].

3.5. Synthesis of Results

The main findings highlighted the association with a possible several modulatory factors associated with NCDs, such as (1) Identified gastroesophageal reflux as a significant risk factor for DH [16]. (2) Reported that post-bariatric surgery patients can presented a higher prevalence of dental erosion/non-carious lesions due to increased episodes of vomiting and acid reflux [24]. Emphasized that smoking possible significantly increases the incidence of gingival recession [17]. The findings of this scoping review reinforce the associations of lifestyle and quality of life on NCDs:

3.5.1. Behavioral and Systemic Risk Factors

- Smoking: Reported in 7 out of 20 studies, associated with GR and DH.

- Bruxism and anxiety: Identified in 10 studies as possible modulators of NCDs, particularly in the progression of NCCLs and DH.

3.5.2. Systemic and Surgical Conditions

- GERD: Patients in 3 studies exhibited a higher prevalence of dental erosion/non-carious lesions.

- Post-bariatric conditions: Associated with increased incidence of vomiting and acid reflux.

3.6. Lack of Standardized Protocols

The methodologies employed across the studies varied considerably, including the use of questionnaires and specific clinical examinations, underscoring the need for standardized assessment protocols.

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Evidence

Most studies were conducted in young and adult populations, with a predominance of cross-sectional designs (70%), focusing primarily on behavioral factors such as acidic diet, anxiety, use of antidepressants, bruxism, and improper brushing habits.

To begin with, it is essential to emphasize that specific categories of NCDs can function as modulators of other NCDs, shaped by risk factors linked to an individual’s lifestyle and overall quality of life. When considering the clinical approach to diagnosing NCDs and identifying their modulatory risk factors, the first step is to conduct thorough anamnesis. Anamnesis represents the initial phase of diagnosis and involves the detailed collection of information regarding the patient’s chief complaint and medical history, being essential for high-quality care [32]. During this phase, it is possible to identify comorbidities such as diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and hypertension, as well as to understand the patient’s emotional state, which is critical for appropriate management throughout treatment [33]. For a more accurate diagnosis and the development of patient-centered dentistry, an individualized anamnesis, addressing lifestyle factors and the human aspects of the patient, enables the dental professional to design a more effective and tailored treatment plan [34].

The accelerated transformations in lifestyle and quality of life, previously driven by globalization, were further intensified by the COVID-19 pandemic. This led to a significant global increase in anxiety levels [35]. During the pandemic, the uncertainty and complexity of the situation exacerbated psychological issues across the population, making individuals more vulnerable to stress [36]. In recent years, unhealthy relationships with work have also contributed to high stress levels, including instances of burnout. This is largely due to the intensification of work demands and the lack of clear boundaries between professional and personal life, resulting in an overall decline in well-being and quality of life [37].

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), when administered to patients in dental settings, can provide valuable insights into their emotional state, allowing for a better understanding of their oral health and lifestyle habits. This, in turn, contributes to a more holistic and integrated treatment approach [38]. Studies from external literature have shown that patients with BDI scores indicative of depression often present with DH, dental erosion, and habits involving the consumption of acidic foods and beverages, as well as dental clenching. Therefore, the BDI serves as an important tool for identifying potential etiological factors linked to psychological conditions, particularly in cases involving hypersensitivity, clenching, and dental erosion [39].

Furthermore, by linking an acidic diet as a significant factor in the prevalence of NCLs, it was observed that the frequent consumption of acidic foods and beverages, such as citrus fruits and energy drinks, plays a crucial role in the progression of these lesions [28]. 12 of the 20 (60%) articles included in the qualitative synthesis reported at least one type of dietary habit. Meanwhile, other studies have reported that individuals with lower income and higher anxiety levels were more likely to develop NCCLs, while bruxism was identified as a relevant risk factor in several studies included in the qualitative analysis [12,37].

There is a clear need for a standardized protocol for the assessment and evaluation of NCLs, as well as the incorporation of individualized anamnesis, particularly in the current context characterized by increased levels of anxiety, stress, and the pursuit of professional development [3]. Such a protocol, used alongside clinical examination and patient history, would facilitate the identification of risk factors related to lifestyle and quality of life, as well as personal habits and characteristics that influence the modulation of NCDs. The lack of a specific protocol hampers the standardization of diagnostic approaches.

It is worth noting that the population analyzed in the studies included consisted of young and adult individuals, as NCDs are considered pathological within this age group and, together with associated risk factors, constitute part of the EOAS. In contrast, when lesions such as NCLs, DH, GR, cracks/fractures, and pulpal damage occur in older adults, they are regarded as physiological and age-appropriate manifestations [3,7]. However, in the present review, studies addressing cracks/fractures and pulpal damage were not included, highlighting a gap in the clinical-scientific literature regarding factors associated with Early Oral Aging Syndrome (EOAS) in these specific contexts.

Three key aspects must be considered when evaluating the clinical examination for the diagnosis of NCDs: salivary assessment methods, DH testing, and GERD screening. Salivary proteins can provide protection against erosive tooth wear by regulating calcium and phosphate ions around the enamel surface [40]. Reductions in salivary flow may result from external factors such as comorbidities or intense physical activity, as well as from metabolic changes following surgical interventions, such as in post-bariatric patients. These reductions can compromise the protective capacity of saliva [41].

The harmful habit of smoking can also affect the composition and function of the salivary glands, exacerbating xerostomia by reducing salivary flow [42]. Saliva thus plays a crucial role in modulating NCDs, with hyposalivation and xerostomia being potential clinical features [39]. Studies have shown that smoking is associated with a higher prevalence of gingival recession, which consequently increases vulnerability to DH and NCCLs [17,27]. These findings support the multifactorial complexity of NCLs, in which behavioral and environmental factors interact and contribute synergistically.

The diagnostic process of DH should be multidimensional, starting with a comprehensive anamnesis that covers the patient’s medical and dental history, followed by a thorough clinical examination. This includes the use of air flow and water rinsing to simulate potential stimuli and assess the patient’s pain response, which can be measured using the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) [4,7,31,43,44]. It is essential that the dentist is able to differentiate DH from other dental conditions and to understand the etiological factors leading to this condition, such as the exposure of dentinal tubules and nerve endings, in order to ensure an accurate diagnosis and effective treatment [45].

The habit of brushing teeth with high frequency or using hard-bristled toothbrushes is reported as a risk factor for increased DH and gingival recession. Some studies highlight that vigorous brushing may be one of the main etiological factors in gingival recession, which is strongly associated with DH [14]. However, toothbrushing should not be considered the primary factor in the progression of the disease, but rather a contributing factor associated with another modulatory risk factor for NCDs [3].

Patients with GERD often present with NCLs, also known as dental erosion, which are detectable during clinical examinations. This finding is of utmost importance for indicating the presence of GERD or supporting its diagnosis [3,46,47]. Additionally, reflux indicators can also be identified in saliva, as patients with this condition tend to exhibit elevated levels of salivary bile acids, such as taurocholic acid and glycolic acid [3]. Early detection of GERD through clinical examination is essential to prevent the progression and spread of NCLs, thereby allowing the dental surgeon to initiate prompt intervention in the treatment of the disease, reducing the associated dental complications and, consequently, the severity classification within the new framework of the EOAS. Furthermore, it was observed that GR increased the prevalence of NCLs by approximately 10× [27].

These findings underscore the complexity and interrelationship among different NCDs, emphasizing the need for integrated approaches to diagnosis, treatment, and the identification of risk factors involved in disease modulation.

4.2. Limitations

This scoping review has some limitations that should be acknowledged to contextualize the interpretation of its findings. Although critical appraisal is not mandatory in scoping reviews, the absence of a formal assessment may limit the ability to judge the strength and reliability of the included evidence. Overall, the body of literature presented considerable methodological variability, including heterogeneous diagnostic criteria for NCDs, differences in data collection methods, and frequent use of convenience samples without clinical calibration. Most of the included studies employed cross-sectional designs, which inherently prevent establishing temporal relationships and therefore cannot support causal inferences between lifestyle factors, quality of life and non-carious diseases. The presence of common confounders, such as socioeconomic status, oral hygiene behaviors, dietary habits, and access to dental care, further constrains the interpretation of observed associations. Additionally, the geographical concentration of studies in Brazil and China may limit the generalizability of the results to broader populations. Despite these limitations, this scoping review offers a comprehensive mapping of current evidence, highlights important knowledge gaps, and underscores the need for well-designed longitudinal studies with standardized diagnostic frameworks to strengthen future research on modulating factors of non-carious diseases.

4.3. Implications for Research and Practice

This scoping review synthesizes the heterogeneous evidence on how lifestyle and quality of life have been examined as modulatory factors of non-carious diseases. By organizing the existing knowledge and identifying methodological gaps, the review supports a clearer understanding of the field and offers guidance for future research and preventive approaches in dental practice

5. Conclusions

This scoping review mapped how lifestyle, behavioral and quality of life factors have been examined as modulators of NCDs. The evidence synthesized indicates that dietary habits, particularly frequent exposure to acidic foods and beverages, were the most consistently reported contributors to the progression of non-carious lesions. Behavioral and psychosocial factors, such as anxiety, parafunctional habits, and bruxism, were also frequently associated with non-carious cervical lesions and dentin hypersensitivity. Smoking, use of antidepressants and systemic conditions, including gastroesophageal reflux and post-bariatric states, additionally appeared as relevant modulatory factors within the included studies.

While the heterogeneous methodologies and predominance of cross-sectional designs limit the strength of inferences, the overall findings reinforce the multifactorial nature of NCDs and highlight the importance of incorporating lifestyle-related risk assessment into preventive and therapeutic dental care. This review also identifies important gaps, such as the lack of standardized diagnostic criteria and the scarcity of longitudinal evidence, which should guide future research. By organizing and clarifying the current evidence landscape, this scoping review contributes to advancing the clinical and scientific understanding of NCDs and supports the development of more integrated approaches consistent with the EOAS conceptual framework.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app152413265/s1, Table S1: Checklist from the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses–Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR); Table S2: Search strategies and Boolean operators applied in the selected bibliographic databases. Reference [48] is cited in the Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.S.T.F. and J.V.B.; methodology, R.S.T.F., L.R.P., G.M.T.P., G.H.F.M., E.B.M., P.V.S. and J.V.B.; formal analysis, R.S.T.F.; investigation, R.S.T.F.; resources, R.S.T.F.; writing—original draft preparation, R.S.T.F., L.R.P., G.M.T.P., G.H.F.M., E.B.M., P.V.S. and J.V.B.; writing—review and editing, R.S.T.F., L.R.P., G.M.T.P., G.H.F.M., E.B.M., P.V.S. and J.V.B.; supervision, J.V.B.; funding acquisition, R.S.T.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior–Brasil (CAPES)–Finance Code 001.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Grippo, J.O. Abfractions: A new classification of hard tissue lesions of teeth. J. Esthet. Dent. 1991, 3, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlueter, N.; Amaechi, B.T.; Bartlett, D.; Buzalaf, M.A.R.; Carvalho, T.S.; Ganss, C.; Hara, A.T.; Huysmans, M.-C.D.; Lussi, A.; Moazzez, R.; et al. Terminology of Erosive Tooth Wear: Consensus Report of a Workshop Organized by the ORCA and the Cariology Research Group of the IADR. Caries Res. 2020, 54, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, P.V.; Zeola, L.F.; Wobido, A.; Machado, A.C. Síndrome do Envelhecimento Precoce Bucal; Santos: São Paulo, Brazil, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Soares, P.V.; Grippo, J.O. Lesões Cervicais Não Cariosas e Hipersensibilidade Dentinária Cervical: Etiologia, Diagnóstico e Tratamento; Quintessence Publishing Brasil: São Paulo, Brazil, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Soares, P.V.; Machado, A.C. Hipersensibilidade Dentinária: Guia Clínico; Santos: São Paulo, Brazil, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Loomans, B.; Opdam, N.; Attin, T.; Bartlett, D.; Edelhoff, D.; Frankenberger, R.; Benic, G.; Ramseyer, S.; Wetselaar, P.; Sterenborg, B.; et al. Severe Tooth Wear: European Consensus Statement on Management Guidelines. J. Adhes. Dent. 2017, 19, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favaro Zeola, L.; Soares, P.V.; Cunha-Cruz, J. Prevalence of dentin hypersensitivity: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Dent. 2019, 81, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares, P.V.; Wobido, A.R.; Machado, A.C.; Zeola, L.F.; Figueiredo, R.S.T.; Caixeta, Â.B. Diagnosis of non-carious diseases: Clinical case series. J. Clin. Dent. Res. 2024, 21, 18–37. [Google Scholar]

- Tolentino, A.B.; Zeola, L.F.; Machado, A.C.; Soares, P.V.; Aranha, A.C.C.; Coto, N.P. Non-carious cervical lesions and risk factors in Brazilian athletes: A cross-sectional study. Res. Soc. Dev. 2021, 10, e57210917859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, J.; Pearce, P.F.; Ferguson, L.A.; Langford, C.A. Understanding scoping reviews: Definition, purpose, and process. J. Am. Assoc. Nurse Pract. 2017, 29, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, J.D.; McClure, F.; Scurria, M.S.; Shugars, D.A.; Heymann, H.O. Case-control study of non-carious cervical lesions. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 1996, 24, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Du, M.Q.; Huang, W.; Peng, B.; Bian, Z.; Tai, B.J. The prevalence of and risk factors for non-carious cervical lesions in adults in Hubei Province, China. Community Dent. Health 2011, 28, 22–28. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa, H.; Furuta, K.; Ueno, M.; Egawa, M.; Yoshino, A.; Kondo, S.; Nariai, Y.; Ishibashi, H.; Kinoshita, Y.; Sekine, J. Oral symptoms including dental erosion in gastroesophageal reflux disease are associated with decreased salivary flow volume and swallowing function. J. Gastroenterol. 2012, 47, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukumoto, Y.; Horibe, M.; Inagaki, Y.; Oishi, K.; Tamaki, N.; Ito, H.-O.; Nagata, T. Association of gingival recession and other factors with the presence of dentin hypersensitivity. Odontology 2014, 102, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Closs, L.Q.; Bortolini, L.F.; dos Santos-Pinto, A.; Rösing, C.K. Association between post-orthodontic treatment gingival margin alterations and symphysis dimensions. Acta Odontol. Latinoam. 2014, 27, 125–130. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Cheng, R.; Cheng, G.; Zhang, X. Prevalence of dentine hypersensitivity in Chinese rural adults with dental fluorosis. J. Oral Rehabil. 2014, 41, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rios, F.S.; Costa, R.S.; Moura, M.S.; Jardim, J.J.; Maltz, M.; Haas, A.N. Estimates and multivariable risk assessment of gingival recession in the population of adults from Porto Alegre, Brazil. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2014, 41, 1098–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, R.S.; Rios, F.S.; Moura, M.S.; Jardim, J.J.; Maltz, M.; Haas, A.N. Prevalence and risk indicators of dentin hypersensitivity in adult and elderly populations from Porto Alegre, Brazil. J. Periodontol. 2014, 85, 1247–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaksson, H.; Birkhed, D.; Wendt, L.K.; Alm, A.; Nilsson, M.; Koch, G. Prevalence of dental erosion and association with lifestyle factors in Swedish 20-year olds. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2014, 72, 448–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasselkvist, A.; Johansson, A.; Johansson, A.K. A 4 year prospective longitudinal study of progression of dental erosion associated to lifestyle in 13–14 year-old Swedish adolescents. J. Dent. 2016, 47, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seong, J.; Bartlett, D.; Newcombe, R.G.; Claydon, N.C.A.; Hellin, N.; West, N.X. Prevalence of gingival recession and study of associated related factors in young UK adults. J. Dent. 2018, 76, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, D.N.R.; Zeola, L.F.; Machado, A.C.; Gomes, R.R.; Souza, P.G.; Mendes, D.C.; Soares, P.V. Relationship between noncarious cervical lesions, cervical dentin hypersensitivity, gingival recession, and associated risk factors: A cross-sectional study. J. Dent. 2018, 76, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, K.O.; Oderinu, O.H.; Oginni, A.O.; Uti, O.G.; Adegbulugbe, I.C.; Dosumu, O.O. Dentine hypersensitivity and associated factors: A Nigerian cross-sectional study. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2019, 33, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghat, N.; Werling, M.; Östberg, A.L. Oral Health-Related Quality of Life After Gastric Bypass Surgery. Obes. Surg. 2020, 30, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medeiros, T.L.M.; Mutran, S.C.A.N.; Espinosa, D.G.; do Carmo Freitas Faial, K.; Pinheiro, H.H.C.; D’Almeida Couto, R.S. Prevalence and risk indicators of non-carious cervical lesions in male footballers. BMC Oral Health 2020, 20, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, B.; Wong, H.M.; Perfecto, A.P.; McGrath, C.P.J. The association of socio-economic status, dental anxiety, and behavioral and clinical variables with adolescents’ oral health-related quality of life. Qual. Life Res. 2020, 29, 2455–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demarco, F.F.; Cademartori, M.G.; Hartwig, A.D.; Lund, R.G.; Azevedo, M.S.; Horta, B.L.; Corrêa, M.B.; Huysmans, M.D.N.J.M. Non-carious cervical lesions (NCCLs) and associated factors: A multilevel analysis in a cohort study in southern Brazil. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2022, 49, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolak, V.; Ristić, T.; Melih, I.; Pesic, D.; Nikitovic, A.; Lalovic, M. The frequency of cervical dentine hypersensitivity and possible etiological factors in an urban population: A cross-sectional study. Vojnosanit. Pregl. 2022, 79, 1209–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, S.; John, P.K. Gingival recession: Prevalence, extent, and severity in women belonging to self-help groups from a panchayat in Kerala. J. Indian Assoc. Public Health Dent. 2023, 21, 324–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goergen, J.; Costa, R.S.A.; Rios, F.S.; Moura, M.S.; Maltz, M.; Jardim, J.J.; Celeste, R.K.; Haas, A.N. Oral conditions associated with oral health-related quality of life: A population-based cross-sectional study in Brazil. J. Dent. 2023, 129, 105582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmer, R.; Barbosa, G.F.; Portella, F.F.; Soares, P.V.; Reston, E.G. Association between non-carious cervical lesions, dentin hypersensitivity and anxiety in young adults: A cross-sectional study. J. Dent. 2025, 153, 105563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Cunha, S.B.; Barros, A.L.; Leite Botura, A.L. Análise da implementação da Sistematização da Assistência de Enfermagem segundo o Modelo Conceitual de Horta. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2005, 58, 568–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correia, S.; Da Silva, A.; Bueno, S. A importância da anamnese em procedimentos odontológicos. Rev. Cient. 2021, 1, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Mota, L.Q.; Farias, D.B.L.M.; Santos, T.A. Humanização no atendimento odontológico: Acolhimento da subjetividade dos pacientes atendidos por alunos de graduação em Odontologia. Rev. Odonto 2012, 48, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macêdo, A.D.; Lima, L.A.O.; Soares, T.E.C.; Araujo, A.M.L.; Rômulo, A.V.; Lucci, J.R.; Oliveira, T.S.; Gurgel, G.P.; Nunes, Q.S.; Santos, P.H.S. Saúde ocupacional: Os efeitos da pandemia sobre a qualidade de vida de profissionais da Atenção Primária à Saúde (APS). Rev. Seven Editora 2024, 6, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Triantafillou, E.; Tsellos, P.; Christodoulou, N.; Tzavara, C.; Christodoulou, G.N. Quality of life and psychopathology in different COVID-19 pandemic periods: A longitudinal study. Psychiatriki 2024, 35, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrente, M.; Park, J.; Akuamoah-Boateng, H.; Atanackovic, J.; Bourgeault, I.L. Work & life stress experienced by professional workers during the pandemic: A gender-based analysis. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbin, C.A.S.; dos Santos, L.F.P.; Garbin, A.J.S.; Saliba, T.A.; Saliba, O. Fatores associados ao desenvolvimento de ansiedade e depressão em estudantes de Odontologia. Rev. ABENO 2021, 21, 1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padrós, F.; Pintor Sánchez, B.E. Estructura interna y confiabilidad del BDI (Beck Depression Inventory) en universitarios de Michoacán (México). Psicodebate 2021, 21, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dipalma, G.; Inchingolo, F.; Patano, A.; Guglielmo, M.; Palumbo, I.; Campanelli, M.; Inchingolo, A.D.; Malcangi, G.; Palermo, A.; Tartaglia, F.C.; et al. Dental erosion and the role of saliva: A systematic review. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2023, 27, 10651–10660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelrahman, H.H.; Ammar, N.; Hassan, M.G.; Essam, W.; Amer, H. Erosive tooth wear and salivary parameters among competitive swimmers and non-swimmers in Egypt: A cross-sectional study. Clin. Oral Investig. 2023, 27, 7777–7785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, W.; Malvaso, A. Understanding the longitudinal associations between e-cigarette use and general mental health, social dysfunction and anhedonia, depression and anxiety, and loss of confidence in a sample from the UK: A linear mixed effect examination. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 346, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.X.; Tenenbaum, H.C.; Wilder, R.S.; Quock, R.; Hewlett, E.R.; Ren, Y.-F. Pathogenesis, diagnosis and management of dentin hypersensitivity: An evidence-based overview for dental practitioners. BMC Oral Health 2020, 20, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S. Dentinal hypersensitivity: An overview, pathogenesis and management of dentinal hypersensitivity. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. (IJFMR) 2024, 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Alakkad, T.M.A.A.; Enezi, A.H.A.; Alazraqi, M.S.; Qurban, A.O.; Alhazmi, L.S.; Ballol, K.M.; Madani, S.M.A.; Almakrami, M.H.; Alomran, A.A.; Hakami, R.A.; et al. Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management of dentin hypersensitivity. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2023, 11, 449–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanushevich, O.O.; Maev, I.V.; Krikheli, N.I.; Andreev, D.N.; Lyamina, S.V.; Sokolov, F.S.; Bychkova, M.N.; Beliy, P.A.; Zaslavskaya, K.Y. Prevalence and Risk of Dental Erosion in Patients with Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Meta-Analysis. Dent. J. 2022, 10, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, M.P.C.M.; Figueiredo, R.S.T.; Andrade, M.D.; Soares, P.V. Aesthetic smile modification associating Periodontology and Operative Dentistry in patient with non-carious lesion: Case report with 12-month follow-up. J. Clin. Dent. Res. 2023, 20, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMAScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).