Abstract

A Monte Carlo-based model of the CyberKnife M6 6 MV Flattening Filter-Free (FFF) beam was developed to produce the data that can be used to train artificial neural networks. The data include the energy spectra of the beam, its average energy, the spatial distributions of the beam, and the distributions of the photon propagation directions for two selected radiation fields—a large one with a diameter of 60 mm, and a small one with a diameter of 15 mm. The GEANT4 code was used to develop the beam model. The developed model was verified by comparing the depth-dose distributions along the beam axis and the profiles obtained in both simulations and measurements. The data included in this paper, intended for training neural networks, will be made available via Google Drive.

1. Introduction

The development of high-performance microprocessors and the sharp increase in their power over the last two decades have resulted in rapid advancement of computer technologies. This progress has enabled the widespread use of Monte Carlo (MC) methods, which guarantee high quality of the models created and, in many cases, provide more accurate results than those obtained using experimental techniques. An example is gamma radiation dosimetry for small radiation fields [1,2]. In this case, even miniature detectors are often too large to perform the measurements with a reliable accuracy [3]—this applies, for example, to therapeutic beam profiles. An additional advantage of MC modeling over the experiment is the application of the so-called logic detectors [4]. Their response depends neither on the type nor on the energy of radiation nor on other factors such as ambient temperature, the presence of a cable supplying current to the detector, or the discharging of the electric impulse generated in the detector under the influence of radiation before reaching the electrometer, etc. The Monte Carlo beam models are also implemented in clinical treatment planning systems and in the calculation of energy spectra and other parameters characterizing radiation beams produced by various types of medical accelerators [5,6]. The great precision of Monte Carlo calculations is particularly crucial for new radiotherapy protocols, such as hypofractionation, “flash” radiotherapy, and hadrontherapy (proton or ions) [7].

MC modeling enables the generation of large, diverse datasets necessary to improve algorithms based on artificial neural networks [8]. For example, a novel deep learning-based MC post-processing framework, termed DeepMC, has been recently announced, which employs deep convolutional neural networks as a complement to traditional MC acceleration techniques, which is especially useful in adaptive MRI-linac therapy [9]. Furthermore, another framework based on deep learning was used to denoise MC dose distributions in proton radiotherapy, enabling faster calculation times [10]. The denoising technique for Monte Carlo simulations is a rapidly developing field. Recent publications focus on leveraging advanced models, such as deep neural networks (DNNs), to significantly reduce noise while maintaining the traditional methods. Reviews, such as that by Liew Wen Yen et al. [11], confirm that machine learning, including convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and generative adversarial networks (GANs), has become a pivotal tool in denoising for computer graphics, where MC simulations are common. These methods are particularly effective in low-sample-count scenarios, which considerably lowers computational costs [12].

The aim of this work was to develop a model of a 6 MV Flattening Filter-Free (FFF) radiation beam produced in the M6 version of the CyberKnife (CK) device. A number of parameters characterizing this beam in a water phantom were determined via modeling, such as the energy spectra and average energy of the beam, a beam intensity distribution, and the directions of photon propagation determined using the momentum vector. The simulations were performed for the small and large radiation fields of 15 mm and 60 mm, respectively, in the depth range up to 300 mm and for various distances from the beam axis. The selection of extreme cases, i.e., the largest field generated by the CK and a small one, is beneficial for AI training. This approach is based on a strategy of maximizing the coverage of the device’s operational range and identifying potential issues at the boundaries of its performance. Training AI in the largest field may ensure that the system is prepared for less common, but often complex and challenging cases. When taking into account fields that vary greatly in size, it is possible to create a more robust and comprehensive AI model that will perform significantly better in “typical” cases and in extreme settings. Furthermore, it allows for a deeper understanding of the device’s performance across a wide range of field sizes and identifies areas for potential improvement in the AI algorithm. Data like the one presented in this paper can be very useful for training ANNs, as reflected in numerous publications. An example of the use of the correlation between the depth dose distribution along the beam axis and the beam’s energy spectrum was presented in detail by Torres-Diaz et al. [13]. The authors reconstructed the spectra of three linear accelerators using the Fredholm integral equation and artificial neural networks trained on data analogous to ours, including dose distributions and spectra in a water phantom. This type of data can also form the basis for creating accurate and physically consistent AI models for dose prediction [14]. They can also be used to optimize and validate AI-based treatment-planning algorithms and generally improve quality control processes [15].

The collected data constitute a database for two chosen radiation fields, intended to train artificial neural networks. Currently, such beam characterization data for the M6 CyberKnife model is lacking. In this context, this work is innovative.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Simulated System

2.1.1. Therapeutic Beam Model

To create a therapeutic beam model that accurately reflects the properties of a real beam from the CyberKnife M6 accelerator by Accuray Incorporated (USA), all components of the linac head that influence dose distributions were recreated. The simulation began with 6.7 MeV electrons directed at a conversion target. Here, the electrons decelerated and generated X-ray radiation. The spatial distribution of the electrons in front of the target followed a normal distribution with an FWHM of 3 mm. The details of the model, including the materials used, were taken from the device’s technical specification sheet. The choice of energy and the spatial spread of the electron beam hitting the target were preceded by long-term simulations. It turned out that electron energy spread in the range of 0–1 MeV (FWHM in a Gaussian distribution) did not significantly affect the dose distributions. Therefore, a monoenergetic electron beam was assumed in the model. The spatial spread was also considered to be Gaussian. It did not affect the dose distributions if the FWHM did not exceed 5 mm. The deformation of the profile shape at their edges was noticeable only for FWHM > 5 mm. This deformation became greater for larger FWHMs, with tests performed in the range from a “pin” beam (FWHM = 0) to FWHM = 15 mm. We decided to adopt the FWHM specified by the accelerator manufacturer (FWHM = 3 mm). Optimal electron energy searches were performed in the range of 5.5 to 7.5 MeV. The best fit to the measured PDDs and profiles occurred for the energies ranging from 6.2 MeV to 7.2 MeV. Within this range, the energy changes did not significantly affect the dose distributions. Only exceeding these ranges caused visible changes in the dose distributions. For energy of 7.2 MeV, a shift in the maximum dose depth was from 1.5 cm (for 6.7 MeV) to 1.6 mm, while for energy of 6.2 MeV, the maximum dose depth was 1.4 cm. With larger energy changes, the shifts were greater, and a change in the shape of the profiles at their edges was noticeable.

2.1.2. Dose Distribution Calculations

In the simulations, dose distributions were determined in a water phantom of 63 cm × 52 cm × 63 cm. These dimensions ensured a full scattering environment, corresponding to the phantom used in the experiments that verified the simulations. Doses were recorded using logical detectors. These were precisely defined cylindrical areas within the water phantom that recorded the dose absorbed in their volume.

2.1.3. Logical Detector Configuration

The logical detectors had a height of 2.8 mm and base diameters of 1.2 mm for the 15 mm diameter radiation field and 2.4 mm for the 60 mm diameter field. Their sizes were chosen so as

- -

- to achieve good statistical results in the simulations (small statistical fluctuations, i.e., one standard deviation of the average dose value < 1%),

- -

- to obtain results in a reasonable amount of time; PDDs (percent depth doses) and profiles for a single field were acquired within a week of continuous calculations using a 12-core computer,

- -

- to maintain a relatively small dose gradient within the detector volume while preserving the typical shape of the sensitive part of real detectors used in dosimetry.

2.1.4. Data Recording

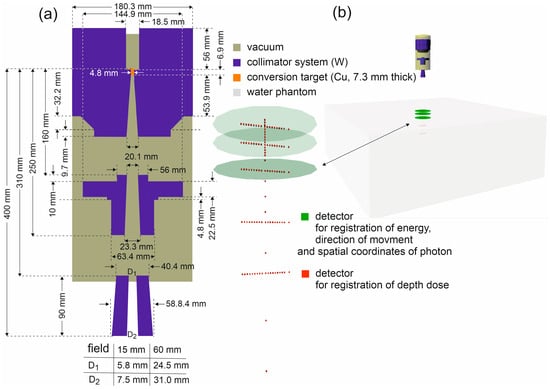

The photon energies, their spatial coordinates, and the values of their momentum vectors (which determine the directions of photon propagation) were recorded in circles with a 200 mm diameter, perpendicular to the main axis of the beam. The simulated system is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

(a) Scheme of the CyberKnife M6 head components used to model the FFF 6 MV beam, with the dimensions and materials of the individual elements indicated. All horizontal dimensions are diameters. The simulated system has axial symmetry about the beam axis. (b) The Virtual Reality Modeling Language (VRML) visualization of the simulated system.

2.2. Software and Simulated Physical Processes

The developed model was based on the GEANT4 code v. 4.11.2 [16,17,18], which enables one to simulate all important processes occurring during the emission of the 6 MV X-ray FFF therapeutic beam, i.e., the conversion of electrons into X-rays, photoelectric effect, Compton effect, electron-positron pair production, Rayleigh scattering, electron and positron scattering, positron annihilation, ionization and atomic relaxation processes. Low-energy models of electromagnetic interactions collected in the Livermore library of the GEANT4 package were used in the simulations. These models describe Compton scattering from about 10 eV, using interpolated data from the evaluated atomic data libraries (EADL, EEDL, EPDL, respectively) developed at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) in the US, provided by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) website [19]. The Livermore models have been benchmarked in many works [20,21,22,23,24]. The range cuts were 100 mm for photons and 10 mm for electrons in all simulations performed. In the case of a therapeutic beam model, scattered radiation is of great importance. It determines the physical penumbra, significantly contributes to the dose in the water phantom, and so on. Therefore, the lower energy limit that can be achieved by given models of physical processes is crucial. Among the available GEANT4 models of electromagnetic processes, the Livermore models offer the greatest potential in this regard. Details can be found on the GEANT4 project website. The simulations were carried out using a computing cluster at the Silesian Center for Education and Interdisciplinary Research in Chorzów (Poland).

2.3. The Experiment Verifying the Simulations

The dosimetric reference data was acquired at the Maria Sklodowska-Curie National Research Institute of Oncology in Gliwice. The selected dose distributions were measured with an SRS diode type 60018 (PTW, Freiburg, Germany). This detector is strongly recommended by the CyberKnife vendor for the commissioning procedures due to its radius of 0.6 mm, height of 250 μm, and a large dose response—the nominal response is 175 nC/Gy. It was installed parallel to the beam axis in the PTW BeamScan Water Phantom, which provides 3D measurements with a position resolution of 0.1 mm. The longitudinal and lateral dose distributions of the fixed field size collimator at a defined depth were acquired point by point, then symmetrized and averaged into one representative depth-dose distribution. All depth-dose distributions for one field size were measured in a one-time session without turning off the high voltage. Moreover, the reference chamber placed next to the primary collimator continuously monitored the linac stability, and every point of the measurement was normalized to its indication.

3. Results

The data were collected for the selected irradiation conditions, i.e., SSD = 80 cm and two radiation fields—the small field with a diameter of 15 mm and the large field with a diameter of 60 mm for the 6 MV X-ray FFF therapeutic beam. The fixed collimators were used for this purpose. The energy spectra and the average energies of the beam, the distributions of photon fluences, and the photon propagation directions at selected depths d in water, as a function of the distance r from the main axis of the beam, were determined.

3.1. Simulation Verification

3.1.1. Denoising of Dose Distributions Obtained by Simulation

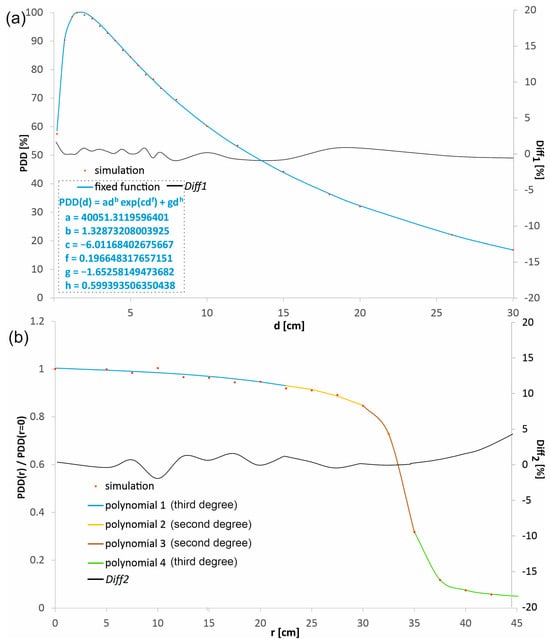

The percentage depth doses in the beam axis (PDD) and the profiles in water at the selected depths d1 = 1.5 cm, d2 = 5.0 cm, d3 = 10 cm, and d4 = 20 cm, obtained in the MC simulations, were experimentally verified for both radiation fields considered and SSD = 80 cm. The dose distributions obtained in the simulations, before being compared with the measured distributions, were subjected to a procedure aimed at denoising by fitting mathematical functions to the dose distributions using the least-squares method. The function adb·exp(cd f) + gdh describes PDDs well (see Figure 2a). The choice of a product of power and exponential functions is not accidental. Dose distributions in water, especially the depth dose curves (DDCs), often exhibit characteristics that can be well described by this product function. The power function exclusively describes the initial dose build-up region. In this region, the number of secondary electrons created by the photon beam increases with depth. As the depth increases, the exponential function starts to dominate. While the power function continues to grow, the exponential function decays more rapidly, representing the attenuation (weakening) of the primary photon beam as it passes through water. At shallow depths, the power function’s growth is stronger than the exponential’s decline, so the total dose increases. At a specific depth, the dose maximum (dmax) is reached. This is the point where the rate of dose increase from the power function is exactly balanced by the rate of dose decrease from the exponential function. Beyond the dose maximum, the exponential decline overwhelms the power function’s growth, causing the dose to decrease with increasing depth, which is precisely what’s seen in PDD curves. The added term gdh causes a small shift in the fitted function to the points in the range of the greatest considered depths. Fitting a function that has a physical justification leads to a model that not only smooths the data but also preserves its underlying physical characteristics. This provides greater confidence that the resulting dose distribution is realistic and artifact-free. Many dose calculation algorithms (e.g., in treatment planning systems) rely on parametric models of depth dose curves. For example, Furhang and Wallace use power and exponential-based models to describe Tissue Maximum Ratio (TMR) or PDD [25]. The authors emphasize that the use of a fitting function whose behavior at range limits mimics the physical phenomena, with as few parameters as possible, effectively eliminates outliers. The least squares method is a widely accepted standard for function fitting. The profiles were denoised using polynomial fitting, a purely mathematical procedure. The fundamental requirement for such profile denoising is the consistency of the polynomials at the endpoints of their ranges. This combination should be seamless, so that all polynomials form a single continuous distribution without any discontinuities. This avoids artifacts resulting from dose distribution changes.

Figure 2.

An example of (a) a percentage depth dose distribution (PDD) and (b) a profile obtained from the simulations, represented by the points and the distributions calculated with the functions fitted to these points. The percentage differences (Diff1 and Diff2) between the dose distributions obtained directly from the simulation and those calculated with the fitted functions are shown. The fitted polynomials were combined to form a continuous function. Polynomial 1 fits from r = 0 to 22.5 mm, ax3 + bx2 + cx + d: a = −4.29832 × 10−6, b = 3.12854 × 10−5, c = −0.001802367, d = 1.003676504; Polynomial 2 fits from r = 22.5 mm to 30.0 mm, ax2 + bx + c: a = −0.000958781, b = 0.039283354, c = 0.531507627; Polynomial 3 fits from r = 30.0 mm to 35.0 mm, ax2 + bx + c: a = −0.023296832, b = 1.408385675, c = −20.43731663; Polynomial 4 fits from r = 35.0 mm to 42.5 mm, ax3 + bx2 + cx + d: a = −5.8859 × 10−6, b = 0.001290637, c = −0.112970786, d = 4.934732404.

Each point in the percentage depth dose distributions and the profiles obtained in the simulations corresponded to the dose value recorded by a single logical detector. In the context of Monte Carlo simulations, a logical detector is a precisely defined, conceptual volume within the simulated geometry (e.g., a water phantom) used to record and tally specific physical events, such as the deposition of energy or the passage of particles, etc. A total of 114 logical detectors were used for one radiation field to obtain the percentage depth dose distribution along the beam axis and four profiles. The logical detectors were not evenly distributed. The number of detectors was higher in the areas with a higher dose gradient, which was associated with a shorter distance between the adjacent detectors. Figure 2a shows the percentage depth dose distribution in the beam axis obtained directly from the simulation and the fitted function for the field with a diameter of 60 mm. Similarly, Figure 2b shows an example profile at a depth of 10 cm from the simulation and the polynomials describing it, also for the field with a diameter of 60 mm. The differences between the dose values obtained directly from the simulation and calculated using the fitted functions did not exceed 1.5% in more than 90% cases, both for the PDD distribution and for the profiles. To assess the quality of the fit, the Diff1 and Diff2 parameters were introduced, defining the difference between the value calculated using the function and the value obtained directly in the simulations. The Diff1 parameter set is defined as follows:

where PDDs(d,0) is the percentage depth dose in water at a depth d in the beam axis (r = 0) obtained directly from the simulation, and PDDf(d,0) is the percentage depth dose in water at the same depth d in the beam axis calculated using the function fitted to the distributions from the simulation. Similarly, the Diff2 parameter set can be defined for profiles:

PDDf(di,r) and PDDf(di,0)—the percentage depth dose in water at the same depth di, at a distance r from the beam axis and at the beam axis (r = 0), respectively, calculated using the fitted function, and PDDS(di,r) and PDDS(di,0)—the percentage depth dose in water at the same depth di, at the distance r from the beam axis and in the beam axis, respectively, obtained directly from the simulation.

The described procedure for denoising was applied to two PDDs and eight profiles. The dose distributions for the field with a diameter of 15 mm were obtained for 1.2 × 1010 simulated primary electrons, while in the case of the field with a diameter of 60 mm, the dose distribution calculations were made by simulating 8.6 × 109 electron hits on the conversion target.

The applied procedure, based on beam modeling using accelerator head components and logical detectors, is an alternative to the method based on the phase space data files. The advantage of this method is primarily that we work on relatively small files, i.e., the result files, which are much smaller compared to the phase space data files, the sizes of which usually range from several gigabytes to even several terabytes. Working with smaller files allows one to avoid many problems, such as not having enough free space on the hard disk. Another extremely effective method that gives results with small fluctuations in a short time is a method based on the mathematical model of the beam directly entering the phantom. However, such a model requires a mathematical description of a number of complex relations between the coordinates of photons, their energy, and the momentum vector, and is generally very complicated.

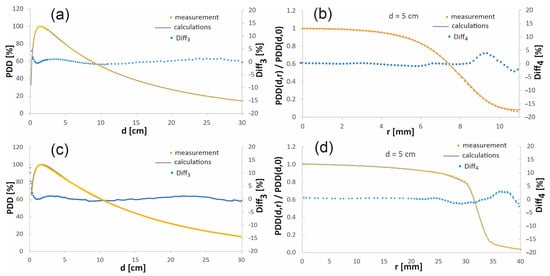

3.1.2. Comparison of Dose Distributions from Calculations with Measurements

To verify the accuracy of the results obtained by simulation, the calculated percentage depth dose distributions and the profiles after denoising, performed according to the procedure described in the previous section, were compared with the analogous dose distributions obtained experimentally. Figure 3 presents such a comparison for the chosen depth-dose distributions. The full comparison for the 15 mm diameter field, as well as for the field with a diameter of 60 mm, at four depths, is published in the online Supplementary Material.

Figure 3.

Comparison of the chosen calculated and measured percentage depth dose distributions in the beam axis (a,c) and the profiles at the depth of 5 cm (b,d) in the water phantom. The top figures (a,b) are for a 15 mm diameter radiation field, while the bottom figures (c,d) show the comparison for a 60 mm diameter field.

In order to assess the compliance of the simulation results with the measurements, the Diff3 and Diff4 parameters were introduced, defining the difference between the calculated depth doses and the measured ones. In the case of the percentage depth doses in the beam axis, the Diff3 parameter set was defined as follows:

where PDDf(d,0) is the percentage depth dose in water at the depth d in the beam axis (r = 0), calculated using the fitted function, and PDDm(d,0) is the percentage depth dose measured in water at the same depth d in the beam axis. However, the parameter Diff4 set was introduced to assess the compliance of the dose profiles:

where PDDf(di,r) and PDDf(di,0) are the percentage depth dose in water at the depth di, at the distance r from the beam axis and at the beam axis (r = 0), respectively, calculated using the fitted function, whereas PDDm(di,r) and PDDm(di,0) are the percentage depth dose measured in water at the same depth di, at the distance r from the beam axis and in the beam axis, respectively.

When comparing the depth–dose distributions obtained in the simulations with the measured distributions, in the case of PDD, the largest discrepancies appear in the built-up area, where Diff3 reaches even several percent. In general, measurement in the region of a large dose gradient is extremely difficult, since even a small change in the order of a fraction of a millimeter in a detector position causes a dose change of up to several percent. Moreover, the differences in the dose distributions are caused by the perturbations induced by the material of the detector. The weakness of the simulation is the relatively much smaller number of events at greater depths and at the edges of the profiles, which worsens the statistics of the calculations.

The quantitative evaluation of volume-averaging effects is a complex problem. First, in an area with a small dose gradient, for example, in the central part of the profile at the maximum dose depth, the volume of the logical detector is not significant because the dose is nearly constant throughout the detector volume. The situation is different in an area with a larger dose gradient. Importantly, the height of the logical detectors is 2.8 mm. Therefore, except for the excluded areas, which we do not consider, it can be assumed that the dose along the entire length of the detector varies linearly with depth. This linearity ensures that the average dose corresponds to the center of the detector. Similarly, in the plane perpendicular to the beam axis, where the detector dimensions are smaller, it even better ensures a linear change in the dose in the detector with distance from the beam axis. Linearity of the dose change in the detector is necessary to ensure that the center of the detector corresponds to the average absorbed dose in the detector volume. This linearity of dose change in the detector may not be maintained at the edges of the profile, as well as in the dose build-up region, where the dose gradient is particularly large, which is why we excluded these areas.

The depth dose distributions outside the high dose gradient area were used to verify the developed beam model. This is a typical approach to the problem of simulation verification used by many researchers [26]. In the case of the PDDs, the area of dose increase to the maximum dose depth, i.e., up to 1.5 cm (i.e., the built-up area of PDD), was not verified. In the case of profiles, their edges were excluded from verification, i.e., depth dose distributions at a distance greater than 7.5 mm from the beam axis for the field with a diameter of 15 mm and greater than 30–40 mm for the field with a diameter of 60 mm were excluded from verification. There are numerous publications [27,28] that present a divergence of the measured profiles and PDDs from the MC simulations. The divergence is usually less than approximately 2% outside of the buildup area, which is consistent with our results. In this work, the discrepancies between simulations and measurements were mostly below 1% for both considered radiation fields, except for the above-mentioned areas with the highest dose gradient.

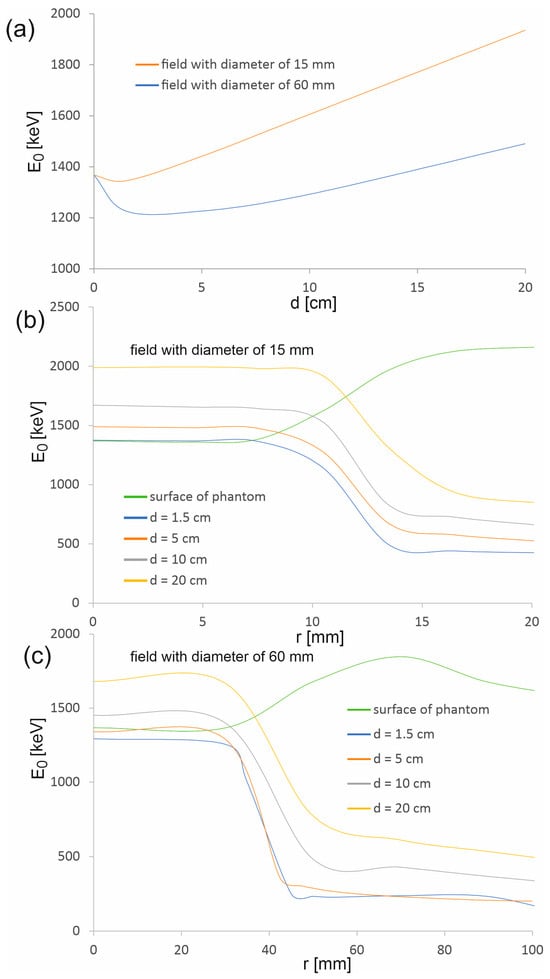

3.2. Energy Dependencies

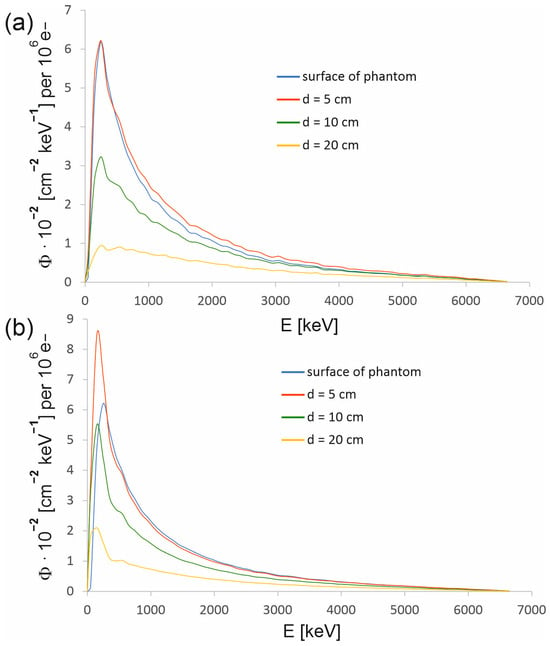

One of the basic parameters characterizing a radiation beam is its energy spectrum. The energy dependencies of the therapeutic beam were determined using the developed model. Figure 4 presents the energy spectra on the surface of the water phantom and at various depths in the beam axis. Figure 6 shows the energy spectra determined at various distances from the beam axis at selected depths in the water phantom. The spectra were expressed as spectral photon fluence (Φ), i.e., the number of photons per energy interval of 1 keV, passing through an area of 1 cm2 as a function of the photon energy. Spectral photon fluence was normalized to one million electrons hitting the conversion target (so-called primary electrons). The photon spectral fluence normalized to the number of primary electrons determined in simulations enables the depth doses to be linked to the current of electrons hitting the target of the CyberKnife M6 device. In the case of spectral photon fluence, the standard deviation did not exceed 1% except for individual cases.

Figure 4.

Energy spectra of the 6 MV FFF beam produced by the CyberKnife M6 device at selected depths in water for the radiation field with a diameter of (a) 15 mm and (b) 60 mm. Each spectrum has been determined in the circle centered at the main axis of the beam and with a radius r defined by a dose of 80% of the dose in the beam axis at a given depth (see Table 1). The photon spectral fluence Φ was normalized to 106 primary electrons.

For a 15 mm field, the spectrum at the phantom surface does not differ significantly from the spectrum at a depth of 5 cm. Thus, most photons reaching the phantom also reach a depth d = 5 cm, and the contribution to the spectrum at this depth from the photons scattered in water is not large. In the case of a 60 mm field, the photons scattered in water make a larger contribution to the spectrum. As a result, the number of photons in the low-energy part of the spectrum at a depth of 5 cm clearly exceeds the number of photons in this part of the spectrum specified on the surface of the phantom. Table 1 shows the radii of the circles in which the spectra presented in Figure 4 were determined. The radius of the circle defines the distance from the beam axis to the point that corresponds to a dose in the profile that is 80% of the dose at the beam axis at a given depth. The measured depth dose profiles were used to determine the radii. However, to determine the radii of the circles in which the spectra are acquired on the phantom surface, the distributions of photons entering the phantom were used, as shown in Figure 8, because a dose profile was not measured on the phantom surface.

Table 1.

The radii of the circles that define the areas within which the energy spectra presented in Figure 4 were determined.

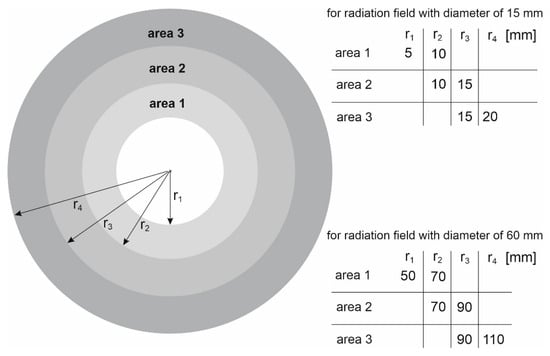

As part of the study, the spectra were also determined in areas outside the therapeutic beam at different distances from the beam axis (Figure 5). Area 1 in the case of the 15 mm diameter field is an exception, because its size and location relative to the beam axis were selected so that this area covers the edge of the profile. The occurrence of a large dose gradient in a relatively large area compared to the entire therapeutic field allowed us to check whether the spectrum representing the edge of the beam is similar to the spectrum in the field or outside the field. It turns out that the spectra from area 1 at the selected depths resemble the spectrum in the field. They are dominated by the beam photons entering the phantom, rather than lower-energy photons originating from the scattering processes in water. The spectra in the areas outside the field are clearly shifted toward a lower energy (Figure 6). Figure 7 shows how the average photon energy E0 changes with a depth d in the water phantom and with a distance r from the beam axis for both fields considered.

Figure 5.

Schematic representation of the areas within which the spectra posted in Figure 6 were determined. The areas are determined by the minimum radius ri and the maximum radius ri+1.

Figure 6.

Energy spectra at the selected depths in the water phantom, at various distances from the beam axis for the 15 mm diameter field (a–c) and for the 60 mm diameter field (d–f). The photon spectral fluence Φ was normalized to 106 primary electrons.

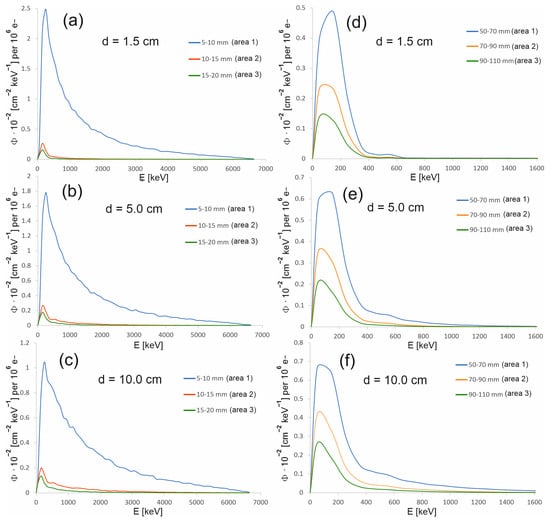

Figure 7.

Average photon energy in the main axis of the beam (a) as a function of depth d in the water phantom and (b,c) as a function of distance r from the beam axis.

The average energy of the photons of the therapeutic beam E0 on the surface of the phantom is the same for both considered radiation fields (1369.0 ± 1.0 keV). In the depth range up to 4.5 mm, there is a slight decrease in the average energy, followed by a clear continuous increase in E0. The decrease is smaller for a smaller field, while the increase is greater. This is due to scattered photons present in and near the beam axis. When the therapeutic beam enters the phantom, a certain part of the photons undergoes scattering processes, which leads to the degradation of photon energy. In the case of a wider beam, the photons leave the therapeutic beam area more easily due to the fact that most photons enter the phantom at larger angles than photons in a narrower beam (Figure 9). Some of these photons, when scattered, lose energy and change direction of propagation, returning to the area of the therapeutic beam. Therefore, the share of scattered photons with energies lower than the energies of photons creating the therapeutic beam is greater in the case of a wider beam. The subsequent layers of water act as an energy filter, which, as a result of Compton scattering processes and the photoelectric effect, removes photons from the beam; the lower the photon energy, the more effective it is. Therefore, the average energy increases with depth.

However, the average photon energy at a given depth within the treatment beam area, up to the beam edge, is approximately constant and then decreases rapidly. This proves that the area outside the therapeutic beam is completely dominated by low-energy photons from Compton photon scattering. The exception is the phantom surface, where the average energy increases outside the therapeutic field. Thus, the contribution of photons scattered in water to the photon field on the phantom surface is negligible.

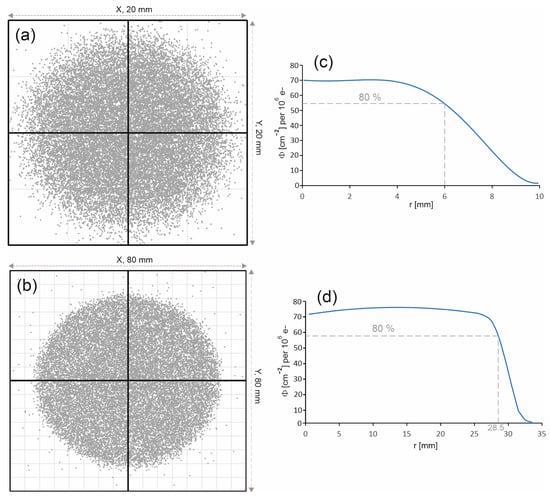

3.3. Spatial Distribution of the Beam

The spatial distribution of the 6 MV FFF beam entering the water phantom has a huge impact on both the distribution of the percentage depth doses along the beam axis and on the profiles. Figure 8a,b present the photon distributions on the surface of the water phantom for both radiation fields. The considered fields are characterized by a uniform photon distribution. In the case of the 60 mm diameter field, the edge of the field is clearly outlined, while in the case of the 15 mm diameter field, the edge of the field is more blurred.

Figure 8.

Photon distributions on the phantom surface for the radiation field with a diameter of (a) 15 mm and (b) 60 mm. The photon entry points into the water phantom are represented by dots. Photon fluence distributions Φ on the surface of the water phantom as a function of the distance r from the beam axis (c) for the field with a diameter of 15 mm and (d) for the field with a diameter of 60 mm. The photon fluence Φ was normalized to 106 primary electrons.

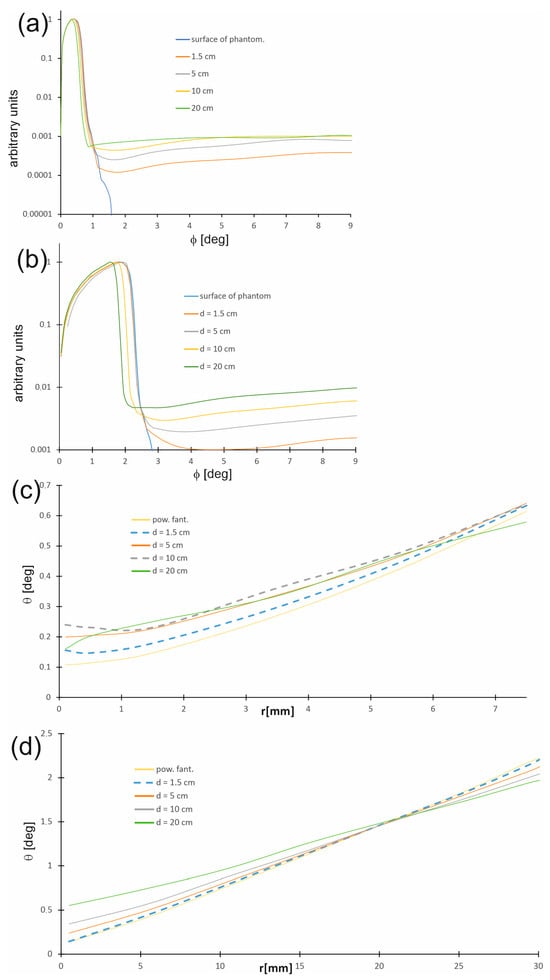

3.4. Directions of Photon Propagation

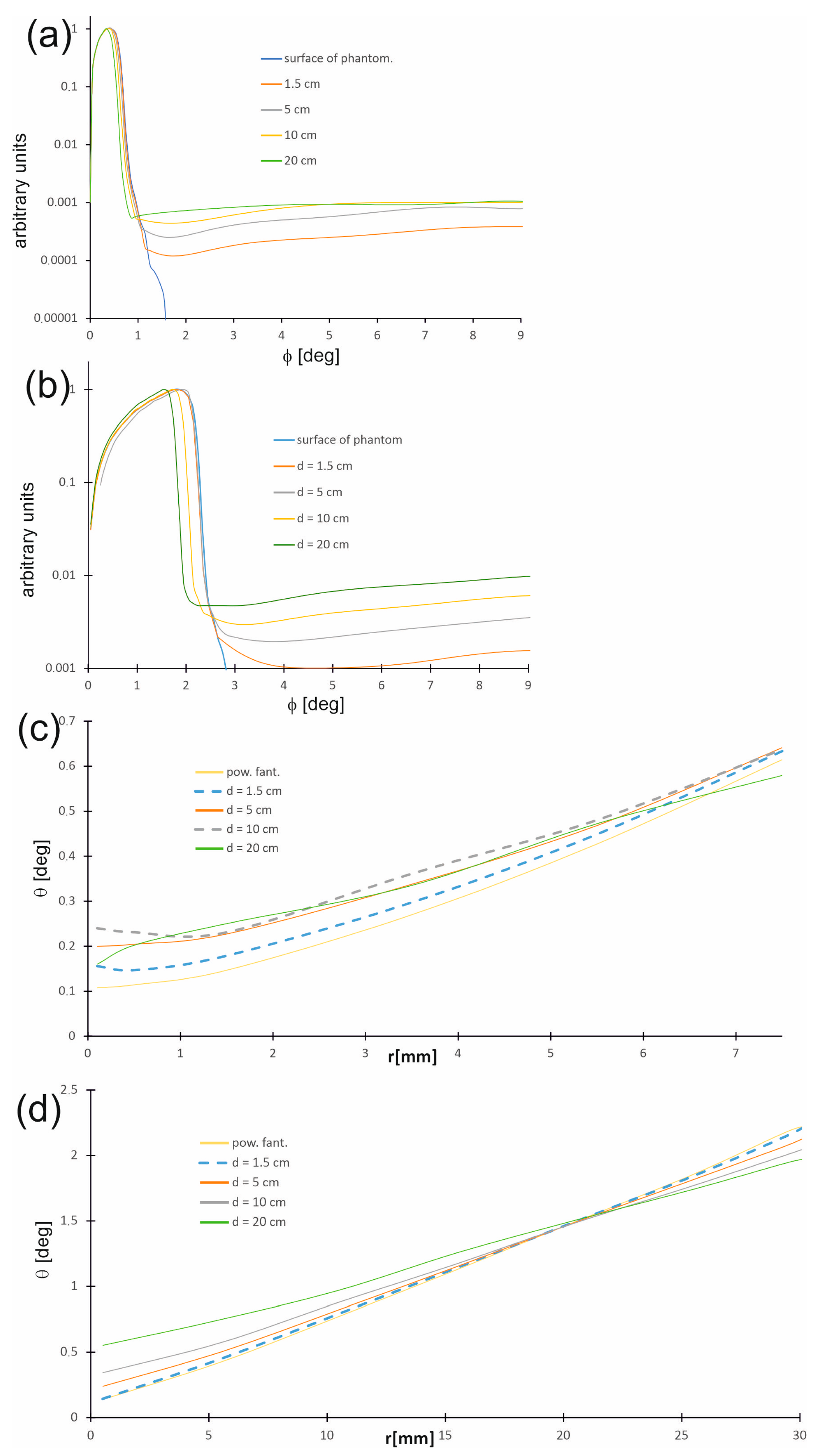

Figure 9a,b show the distribution of directions in which photons travel, called photon propagation directions in the water phantom and on its surface as a function of the angle θ between the photon trajectory direction and the beam axis at selected depths, while Figure 9c,d present the changes in the most probable photon propagation directions depending on the distance r from the beam axis. The distribution of photon propagation directions is related to the radiation field. Generally, within the therapeutic beam, the angles between the directions of photon propagation and the beam axis are small on the phantom surface and do not exceed 1.5 degrees for a 15 mm field, whereas for a 60 mm field, the values are slightly larger, being up to 2.5 degrees. With increasing depth d, the number of photons moving along the trajectories creating larger angles θ increases. Furthermore, regardless of the depth in the phantom, the angle θ increases with increasing distance r from the beam axis.

Figure 9.

Distributions of directions in which photons travel (photon propagation directions) in the water phantom and on its surface as a function of the angle q between the photon trajectory direction and the main axis of the beam (a) for the 15 mm field and (b) for the 60 mm field. Distributions of the most probable photon propagation directions in the water phantom and on its surface as a function of the distance r from the beam axis (c) for the 15 mm field and (d) for the 60 mm field.

4. Summary

In this work, a Monte Carlo model of the CyberKnife M6 6 MV Flattening Filter-Free (FFF) beam was successfully developed and validated. The model, created using the GEANT4 code, was thoroughly verified against experimental data, showing strong agreement in both depth–dose distributions and beam profiles. This validation confirms the model’s reliability in generating accurate and physically consistent data. The developed model can be used successfully to generate data for the remaining available fields.

Each quantity determined in the conducted simulations, such as the absorbed dose in water or spectral photon fluence, was determined in a series of simulations (from 10 to 15 independent runs). Each run provided values independent of the other runs because the runs differed in the starting parameter (seed) of the pseudorandom number generator. Therefore, differences between the absorbed dose values obtained from different runs in the same logical detector result from the stochastic nature of physical processes and are statistically equivalent. The mean value, for example, the absorbed dose in a single logical detector, was the arithmetic mean of the values obtained in individual runs, while the standard deviation was the average standard deviation expressed as a percentage of the mentioned mean value. As mentioned, the standard deviation associated with the absorbed dose obtained in the simulations did not exceed 1% in the areas qualified for comparison with the measured dose distributions. In the case of spectral photon fluence, efforts were also made to ensure that the standard deviation did not exceed 1%. However, in individual cases in the high-energy parts of the spectra, due to the smaller number of events in the logic detector, the standard deviation exceeded 1%, but even there it did not exceed 1.5%.

The primary achievement of this study was the generation of a unique and comprehensive dataset from the validated model. The dataset includes detailed information that is often unavailable in existing literature, such as the spatial and directional distributions of photons, the energy spectra, and the average energy. To demonstrate the differences between various field sizes, we focused on two specific radiation fields: the largest available (60 mm) and a representative small field (15 mm).

The generated data provides a valuable resource for the scientific community. It will make publicly available to facilitate further research and the development of new algorithms, particularly for artificial neural networks.

The results generated were presented as graphs. To use the data to train artificial neural networks, the data should be numerical, since it is not practical to publish numerical results in the article.

Supplementary Materials

The online Supplementary Material and the obtained data in a numerical form have been posted on Google Drive at: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1fBw-hcOl0QkkhvMVJq6Qk0pesRhvcdGk?usp=sharing (accessed on 3 December 2025).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.R. and A.K. (Adam Konefał); methodology, J.R., A.K. (Adam Konefał) and J.P.; software, J.R., A.K. (Adam Konefał) and A.K. (Agnieszka Kapłon); validation, J.R., A.K. (Adam Konefał) and J.P.; formal analysis, M.S. and A.O.; investigation, J.R., A.K. (Adam Konefał) and J.P.; resources, J.P. and M.S.; data curation, A.K. (Adam Konefał); writing—original draft preparation, J.R., A.K. (Adam Konefał) and M.S.; writing—review and editing, J.R., A.K. (Adam Konefał) and M.S.; supervision, A.K. (Adam Konefał); project administration, A.K. (Adam Konefał) All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Eklund, K.; Ahnesjö, A. Modeling silicon diode dose response factors for small photon fields. Phys. Med. Biol. 2010, 55, 7411–7423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarnecki, D.; Zink, K. Monte Carlo calculated correction factors for diodes and ion chambers in small photon fields. Phys. Med. Biol. 2013, 58, 2431–2444, Correction in Phys. Med. Biol. 2014, 59, 791–794. https://doi.org/10.1088/0031-9155/59/3/791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, I.J.; Ding, G.X.; Ahnesjö, A. Small fields: Nonequilibrium radiation dosimetry. Med. Phys. 2008, 35, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrzak, R.; Konefał, A.; Sokół, M.; Orlef, A. Comparison of depth-dose distributions of proton therapeutic beams calculated by means of logical detectors and ionization chamber modeled in Monte Carlo codes. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Accel. Spectrometers Detect. Assoc. Equip. 2016, 826, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konefał, A.; Bakoniak, M.; Orlef, A.; Maniakowski, Z.; Szewczuk, M. Energy spectra in water for the 6 MV X-ray therapeutic beam generated by Clinac-2300 linac. Radiat. Meas. 2015, 72, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrzak, R.; Konefał, A. Determination of Energy Spectra in Water for 6 MV X Rays from a Medical Linac. Acta Phys. Pol. Ser. B 2016, 47, 783–788. Available online: https://www.actaphys.uj.edu.pl/fulltext?series=Reg&vol=47&page=783 (accessed on 3 December 2025). [CrossRef]

- Sarrut, D.; Etxebeste, A.; Muñoz, E.; Krah, N.; Létang, J.M. Artificial Intelligence for Monte Carlo Simulation in Medical Physics. Front. Phys. 2021, 9, 738112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patlán-Cardoso, F.; Ibáñez-Orozco, O.; Rodríguez-Romo, S. X-ray dose profiles using artificial neural networks. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2023, 192, 110575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neph, R.; Lyu, Q.; Huang, Y.; Yang, Y.M.; Sheng, K. Deep MC: A deep learning method for efficient Monte Carlo beamlet dose calculation by predictive denoising in magnetic resonance-guided radiotherapy. Phys. Med. Biol. 2021, 66, 035022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid, U.; Souris, K.; Huang, S.; Lee, J.A. Denoising proton therapy Monte Carlo dose distributions in multiple tumor sites: A comparative neural networks architecture study. Phys. Med. 2021, 89, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, L.W.; Thinakaran, R.; Somasekar, J. Machine Learning-Based Denoising Techniques for Monte Carlo Rendering: A Literature Review. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2025, 16, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeze, M.; Veerman, M.A.; van Heerwaarden, C.C. Machine learning-based denoising of surface solar irradiance simulated with Monte Carlo ray tracing. J. Geophys. Res. Mach. Learn. Comput. 2025, 2, e2024JH000515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Díaz, J.; Grad, G.B.; Bonzi, E.V. Measurement of linear accelerator spectra, reconstructed from percentage depth dose curves by neural networks. Phys. Medica 2022, 96, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Chen, M.; Kazemimoghadam, M.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, K.; Gu, X.; Lu, W. Radiotherapy dose prediction using off -the-shelf segmentation networks: A feasibility study with GammaPod planning. Med. Phys. 2025, 52, 3348–3359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manson, E.N.; Mumuni, A.N.; Fiagbedzi, E.W.; Shirazu, I.; Sulemana, H. A narrative review on radiotherapy practice in the era of artificial intelligence: How relevant is the medical physicist? J. Med. Artif. Intell. 2022, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GEANT4 Project Website. Available online: https://geant4.web.cern.ch/ (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Agostinelli, S.; Allison, J.; Amako, K.; Apostolakis, J.; Araujo, H.; Arce, P.; Asai, M.; Axen, D.; Banerjee, S.; Barrand, G.; et al. GEANT4—A simulation toolkit. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Accel. Spectrometers Detect. Assoc. Equip. 2003, 506, 250–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, J.; Amako, K.; Apostolakis, J.; Araujo, H.; Arce Dubois, P.; Asai, M.; Barrand, G.; Capra, R.; Chauvie, S.; Chytracek, R.; et al. GEANT4 developments and applications. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2006, 53, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IAEA Website. Available online: https://www.iaea.org/resources/databases/photon-and-electron-interaction-data (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Kadri, O.; Ivanchenko, V.N.; Gharbi, F.; Trabelsi, A. GEANT4 simulation of electron energy deposition in extended media. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. At. 2007, 58, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirrone, G.A.P.; Cuttone, G.; Di Rosa, F.; Pandola, L.; Romano, F.; Zhang, Q. Validation of the GEANT4 electromagnetic photon cross sections for elements and compounds. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Accel. Spectrometers Detect. Assoc. Equip. 2010, 618, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanchenko, V.N.; Apostolakis, J.; Bagulya, A.V.; Abdelouahed, H.B.; Black, R.; Bogdanov, A.; Burkhard, H.; Chauvie, S.; Cirrone, P.G.A.; Cuttone, G.; et al. Recent improvements in GEANT4 electromagnetic physics models and interfaces. Prog. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 2011, 2, 898–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, M.K.; Chow, J.C.; Chithrani, B.D.; Lee, M.J.; Oms, B.; Jaffray, D.A. Irradiation of gold nanoparticles by x-rays: Monte Carlo simulation of dose enhancements and the spatial properties of the secondary electrons production. Med. Phys. 2011, 38, 624–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.M.C.; Dimmock, M.R.; Gillam, J.E.; Paganin, D.M. A low energy bound atomic electron Compton scattering model for GEANT4. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. At. 2014, 338, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furhang, E.E.; Wallace, R.E. Fitting and benchmarking of dosimetry data for new brachytherapy sources. Med. Phys. 2000, 27, 2302–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh-Bagheri, D.; Rogers, D.W.O. Monte Carlo calculation of nine megavoltage photon beam spectra using the BEAM code. Med. Phys. 2002, 29, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francescon, P.; Kilby, W.; Satariano, N. Monte Carlo simulated correction factors for output factor measurement with the CyberKnife system-results for new detectors and correction factor dependence on measurement distance and detector orientation. Phys. Med. Biol. 2014, 59, N11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francescon, P.; Kilby, W.; Noll, J.M.; Masi, L.; Satariano, N.; Russo, S. Monte Carlo simulated corrections for beam commissioning measurements with circular and MLC shaped fields on the CyberKnife M6 System: A study including diode, microchamber, point scintillator, and synthetic microdiamond detectors. Phys. Med. Biol. 2017, 62, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).