Abstract

This paper presents an innovative concept for the adaptive transformation of decommissioned coal mine shafts into advanced reduced-gravity research facilities, addressing both post-mining land management and continuous advancements in microgravity research. The proposed solution leverages existing underground infrastructure to create an exceptionally long drop tower, approximately 900 m, surpassing the operational capabilities of all current global facilities. The facility employs electromagnetic propulsion and braking systems compatible with maglev technology, enabling extended microgravity durations and the precise simulation of multiple planetary gravity environments. Comprehensive numerical simulations, taking into account realistic mining shaft geometries, aerodynamic resistance, and mechanical vibration isolation, demonstrate that the system achieves free-fall periods of at least 10 s, which will be longer in the case of a capsule drop for research in reduced-gravity conditions (controlled deceleration of the capsule during the drop). The six-point suspension system effectively isolates experimental payloads from vibrations generated during descent. Beyond technological innovation, the facility exemplifies multidimensional sustainability by integrating scientific advancement with regional economic revitalization, employment generation for mining communities, industrial heritage preservation, and alignment with European Green Deal objectives. This globally unique research center would provide unprecedented opportunities for materials science, space biology, and industrial experimentation, while demonstrating innovative repurposing of post-mining assets.

1. Introduction

Phasing out hard coal excavation in the EU brings varied challenges, including the need to manage post-mining areas and closed coal mine infrastructure. In Europe, related requirements and frameworks are defined by the European Green Deal and its just transition mechanism [1], which applys to EU member states, while Sustainable Development Goals are followed voluntarily [2,3].

Management approaches for closed coal mines and areas affected by their operation include, among others [4,5,6,7,8], full liquidation, various forms of repurposing and adaptive reuse of mining infrastructure, passive land reclamation, or active ecological restoration. These are varied in terms of technical (engineering), economic, environmental, and social aspects [9,10,11]. Post-mining land-use (PMLU) is extensively studied [12,13,14,15,16,17,18].

The adaptive reuse of mining infrastructure has emerged as a strategy to preserve and repurpose existing mine structures for heritage preservation, tourism [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26], and novel technological applications. This approach recognizes that many mine structures possess unique characteristics that are difficult or impossible to reproduce elsewhere. Research in this area reflects an evolving understanding that mine closure is a new lifecycle phase integrating three complementary objectives: environmental restoration, socioeconomic revitalization, and technological innovation, aligned with the principles of just transition frameworks [9]. The development of concepts for novel technological applications focuses on, among others, energy production, storage systems, and the utilization of mine water thermal resources [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50].

This paper presents an innovative concept for the adaptive reuse of a mine shaft that would otherwise be closed and backfilled [51,52,53]: transforming it into research facility for experiments in reduced-gravity conditions. A prerequisite for the selection of a suitable mine shaft is that it provides approximately 1 km of usable vertical length, which provides experimental opportunities exceeding those offered by existing reduced-gravity research facilities worldwide [54].

Reduced-gravity research is crucial element of space exploration and scientific understanding of how various systems behave in the absence of gravity [55,56,57]. So far, numerous studies and experiments have been conducted in space and on Earth to understand the effects of reduced-gravity conditions (in particular, weightlessness and microgravity) on humans, materials, and phenomena, providing inputs for research aimed at inventing solutions applicable in space conditions [57,58]. Early attempts on this matter, like the use of Tilt Table science to investigate the effects of rapid shifts in body mass and evaluations are presented, among others, in [59]. Reduced-gravity research has continued and evolved over the years, covering varied science domains, industries, and strengthening its position in education [60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72].

It should be assumed that space exploration—and the associated need for research and development—will continue, since the objectives have expanded well beyond the “there-and-back” paradigm of the Space Race in the second half of the 20th century. Today, extraterrestrial environments such as the Moon, planets, and asteroids are increasingly regarded as potential domains for human habitation and as valuable sources of mineral resources for extraction (i.e., space mining) [73,74,75,76,77,78].

Simulating reduced-gravity conditions for experiments carried out without leaving the Earth, i.e., in ground-based research facilities, is possible in a few ways. One of them is drop towers (drop tubes), which allow for repetitiveness in generating reduced-gravity conditions [79,80]. Drop towers allow us to carry out, at a moderate cost, short-term experiments and tests prior to long-term missions in space. These facilities allow for the regulation of parameters during experiments and real-time monitoring. The facilities’ accessibility enables rapid experimental turnaround, allowing multiple investigations to be conducted sequentially within a few days, which substantially reduces the interval from initial concept to experimental execution [80,81].

The concept of using drop towers for reduced-gravity research dates back to the late 1950s. NASA Scientist Robert Siegel conducted the first microgravity capillary rise experiments in a drop tower at the NASA Lewis Research Center (now NASA Glenn) shortly after the 1957 launch of Sputnik I [82]. The NASA Glenn Center became operational in 1966. Since then, other reduced-gravity research centers have been created worldwide. These are presented in Chapter 2 of this paper. The demand for advancements in reduced-gravity research is reflected by development of new drop towers in the past few years. In China, the TUFF (Tsinghua University Freefall Facility) started operation in 2020, preceded by a four-year feasibility study and construction phase [83,84,85]. In Germany, GraviTower Bremen was inaugurated as a prototype around 2022 and functions as a complement to the main Bremen Drop Tower [54,86,87]. In the USA, the Electro-Motive Drop Tower (EMDT) is a proposed upgrade to the existing Zero Gravity Research Facility—NASA Glenn Research Center’s 5.2 s drop tower [88].

The proposed solution, i.e., a controlled-gravity research center, the experimental part of which includes a mine shaft, lies at the intersection of the two processes indicated above—sustainable management of closed mines and continuous advancements in reduced-gravity research.

In the presented concept of the research center, the characteristics and inherent limitations of the considered mine shafts in Polish coal mines have been incorporated, directly shaping the architecture of the overall system. The possibility of simulating multiple gravitational environments was also taken into account. To present the system’s structure, the main subsystems of the solution have been identified and described.

2. Chosen Current Solutions Overview

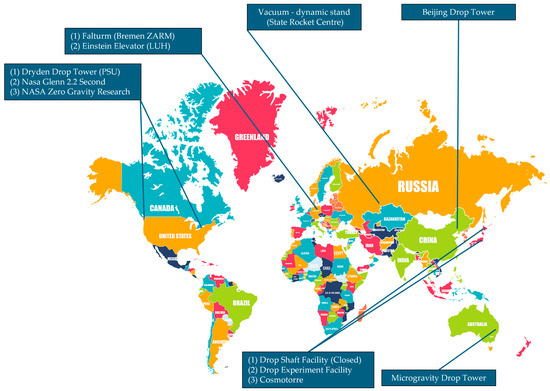

Worldwide, several ground-based facilities for reduced-gravity research have been realized [54,89,90,91,92,93]. The global distribution of large facilities is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Reduced-gravity research facilities in the world.

The first facilities of this type were developed in the USA. NASA operates two facilities at the NASA Glenn Research Center: the Zero Gravity Research (Zero-G) Facility, which offers 5.18 s of microgravity, and the 2.2 s Drop Tower, which offers 2.2 s of microgravity. Additionally, the Dryden Drop Tower (DDT), a facility at the Portland State University (PSU), provides 2.13 s of free-fall time. In China, the Beijing Drop Tower of the National Microgravity Laboratory China (NMLC) allows for 3.5 s of free fall. In Japan, the Cosmotorre facility achieves 2.5–2.8 s, while the Drop Experiment Facility of the Micro-Gravity Laboratory (MGLAB) provides 4.5 s of free fall. In Germany, the Bremen Drop Tower at the Center for Applied Space Technology and Microgravity (ZARM), established in 1990, features a 110 m-high vacuum tube with a free-fall time of 4.7 s. In 2004, a catapult system was added to the facility, extending the microgravity period to 9.3 s via vertical parabolic flight. Additionally, the newest facility has been built in Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Universität Hannover.

In Table 1, the basic parameters of the drop towers over the world are shown.

Table 1.

Worldwide weightlessness research facilities’ parameters [54].

The table systematically compares eleven leading global drop tower facilities dedicated to reduced-gravity research, presenting the key technical and operational parameters that determine each facility’s experimental potential.

A key performance indicator is the duration of free fall, which varies substantially across the table: from just 2 s (QUT Microgravity Drop Tower) to the record of 10 s at the Japanese Drop Shaft Facility. The Bremen Drop Tower, utilizing a catapult, achieves up to 9.3 s (marked by an asterisk). Free-fall heights range from 20 m (Einstein-Elevator in its basic configuration and QUT at 20 m) to 490 m in the Drop Shaft Facility.

The minimal residual acceleration is another critical factor, defining microgravity quality. The German centers set the highest standards, with Fallturm Bremen reaching 10−6–10−7 g and the Einstein-Elevator reaching . Most other towers operate between and , with Vacuum Dynamic Island in Russia showing the least favorable range (10−2–10−3 g).

Maximum braking acceleration, given in units of g, determines the resilience of the experimental apparatus. The Einstein-Elevator offers the softest deceleration (5 g), while the Zero Gravity Research Facility peaks at 36–65 g, and Fallturm Bremen operates at 40–50 g. For Vacuum Dynamic Island, these data are unavailable.

Facility throughput, expressed as the number of experimental cycles per day, is highly uneven. The Einstein-Elevator stands out with up to 300 drops daily, enabling exceptional research flexibility, while most other centers are limited to 2–20 repetitions. The Zero Gravity Research Facility, due to extensive preparation time, supports only two tests daily.

Experimental payload mass varies according to the configuration—capsule (C) or elevator (E)—with the highest capacity at Vacuum Dynamic Island (30,000 kg, capsule), while the smallest facilities allow for loads between 50 and 150 kg. The Zero Gravity Research Facility supports up to 1130 kg using the capsule setup and 455 kg for the elevator.

Test chamber dimensions, provided in millimeters, range from a diameter of 500 mm (50 M Drop Tower, elevator configuration) to 5000 mm (Vacuum Dynamic Island). The Einstein-Elevator offers a 1700 mm diameter in capsule mode.

The last row identifies the type of capsule configuration used: DS (drag shield), VC (vacuum chamber), or FF (free flight). Certain centers offer flexible arrangements, such as the Fallturm Bremen (vacuum chamber with optional free flight) or Einstein-Elevator (drag shield as vacuum chamber or free flight).

Building a microgravity research facility requires the careful consideration of various needs and conditions, like the quality of the microgravity environment, payload accommodation, safety considerations, space for installation and maintenance, cost considerations, and the ability to simulate a microgravity environment. Safety considerations concern, among others, experimental instrumentations. To protect them, the target deceleration should be less than 20 g [83]. Costs to be considered should include expenditures for experiment design, engineering to ensure safety and functionality, launch to space, access to facilities that provide controlled environments, data acquisition, and power supply, as well as experiment operation and, where applicable, the return of the experiment to Earth [94]. Costs affect the accessibility of the research facility. To be most functional, the facility should be able to simulate a microgravity environment for different duration times and different planetary environments.

3. Reinventing a Mine Shaft into a Reduced-Gravity Research Facility

The design process aimed to transform a mine shaft into a facility for research under controlled reduced-gravity conditions has followed a structured approach, beginning with the definition of the requirements derived from a comparative analysis of existing global facilities, proceeding through conceptual design (including iterations informed by numerical modeling), and culminating in the definition of the preliminary technical specifications presented in this chapter. The main design considerations included maximizing microgravity duration (target: >10 s), minimizing residual acceleration (target: <10−5 g), ensuring capsule and payload safety across all operational phases; maintaining compatibility with existing mine infrastructure, and enabling the simulation of multiple gravitational environments (Earth, Mars, and the Moon).

A systems approach has been adopted in the design process. The facility is considered to be a system comprising the following components: the geological and structural infrastructure (mine shaft geometry and material properties); the experimental payload system (drop capsule and research chamber); the propulsion and guidance subsystem (electromagnetic drive and control architecture); the deceleration and safety subsystem (braking mechanisms and emergency protocols); and the monitoring and control subsystem (sensor networks and real-time data acquisition).

Each subsystem of the engineered facility has been analyzed not only in terms of its individual performance characteristics but also in terms of its interactions with other system elements, ensuring that the resulting facility meets the specified operational requirements while maintaining appropriate safety margins. This is in accordance with a systems approach which acknowledges that optimizing individual subsystems in isolation may lead to suboptimal overall performance. For example, maximizing capsule velocity to extend free-fall time increases kinetic energy and braking requirements, which in turn influences structural loads, safety margins, and operational costs. Similarly, the choice between an atmospheric and vacuum operation involves trade-offs between microgravity quality, operational complexity, cycle time, and energy consumption. These interdependencies are further addressed. Design decisions are presented in the context of their system-level implications.

Furthermore, the system’s approach extends beyond technical aspects and encompasses socio-economic and environmental considerations. The designed facility is perceived not merely as a scientific instrument but as a catalyst for regional transformation—simultaneously enhancing reduced-gravity research capabilities, creating employment opportunities for former mining workers, preserving industrial heritage through adaptive reuse, and demonstrating innovative pathways for post-mining land rehabilitation in line with EU just transition principles. This multidimensional perspective ensures that design decisions encompass not only engineering optimality but also sustainability, social responsibility, and long-term operational viability.

The following subsections present the technical foundations of the facility’s design, starting with spatial and operational preconditions, progressing through subsystem specifications (capsule structure, propulsion, braking, and control), and concluding with integrated performance predictions derived from comprehensive numerical simulations. Throughout this discussion, emphasis is placed on the rationale for the design choices, the validation methods employed, and the identification of critical parameters that will require further refinement in subsequent development phases.

3.1. The Main Concept Assumptions—Outlined in Relation to Existing Facilities

The main assumption of this concept is the adaptive reuse of existing coal mine infrastructures, specifically the transformation of a mine shaft into a drop shaft for conducting experiments under controlled, reduced-gravity conditions. The utilization of underground mine infrastructure makes the proposed solution comparable to NASA’s Zero Gravity Research Facility, which also employs a shaft, which was a purpose-built construction. Furthermore, the proposed facility will provide a usable shaft part of approximately 900 m, exceeding those offered by other reduced-gravity research facilities. This extended vertical distance enables exceptional experimental durations in reduced-gravity conditions, positioning the facility as a unique scientific center at the global scale.

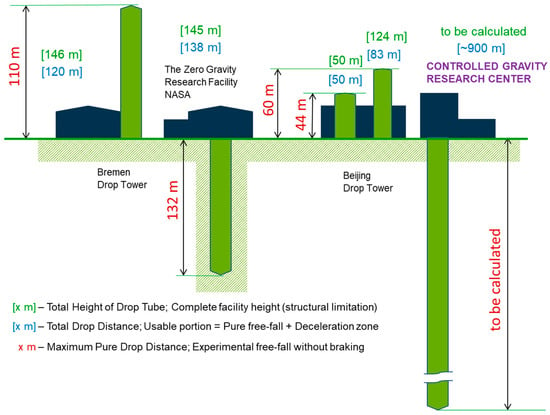

In Figure 2, the main vertical features that characterize reduced-gravity facilities are compared. The reduced-gravity facility that is the subject of design discussed in this paper is also added, limiting to approximate values of one of the main features. The other ones are to be calculated. The total height of the drop tube represents the complete structural facility’s height from which the capsule can start its move down. It includes both above-ground and below-ground infrastructure where applicable. Total drop distance is the entire usable vertical distance allocated for the drop sequence, including both the free-fall experimental phase and the deceleration/braking zone. Maximum pure drop distance is the continuous free-fall segment within which the capsule experiences weightlessness or reduced-gravity conditions. It represents the actual window with the experimental conditions.

Figure 2.

Comparing the conceptualized facility with the existing facilities.

Scientists calculate their experimental timeline based exclusively on the maximum pure drop distance. The deceleration distance, although essential for safety, provides no scientific benefit. Facility engineers, on the other hand, must consider the total drop distance when designing the structural components and underground infrastructure of the drop part of the facility. For example, the ZARM facility (Bremen Drop Tower) extends 146 m above ground with an extensive underground infrastructure to accommodate both the pure drop zone and the deceleration chamber.

3.2. Technical and Spatial Preconditions

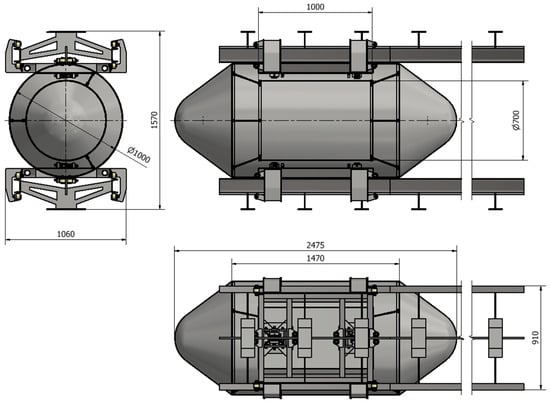

Based on the analysis of the solutions applied in existing reduced-gravity facilities and taking into account technical characteristics of considered drop shafts in Polish coal mines, the following parameters for the development of this work have been established:

- Minimum shaft diameter: 7.5 m;

- Minimum length of the active shaft section: 900 m;

- Capsule diameter: 1 m;

- Capsule height: 2.5 m;

- Maximum capsule mass: 350 kg;

- Maximum capsule velocity: ~99 m/s.

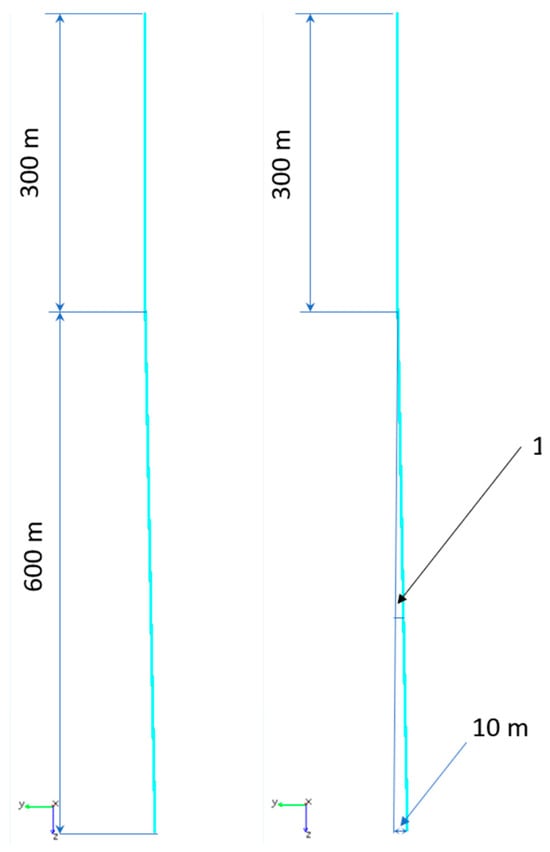

Figure 3 shows the operational assumptions and estimated velocities and decelerations of the capsule during experiments considering the reduced-gravity duration.

Figure 3.

Preliminary assumptions for capsule velocities and decelerations during free-fall periods.

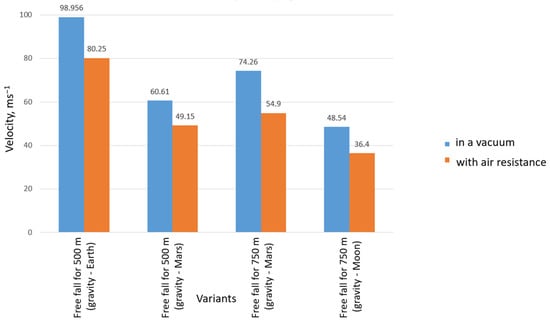

For the development of the propulsion and braking system concept, it was assumed that the total track length available for capsule movement is approximately 900 m. The proposed drive system will enable the capsule to simulate the range between microgravity and Mars gravity conditions. To achieve a state of microgravity lasting approximately 10 s, the capsule is assumed to maintain an acceleration of 9.81 m/s2 over a 500 m section of the track. Under these conditions, after traveling 500 m, the capsule reaches a velocity of approximately 98 m/s (≈356 km/h). To simulate Martian surface gravity, the capsule must maintain an acceleration of 3.68 m/s2. Over a 500 m distance, this corresponds to a velocity of approximately 60 m/s (≈218 km/h). To extend the duration of reduced gravity, the acceleration section may be lengthened to 700–750 m, resulting in terminal velocities of approximately 74 m/s (≈267 km/h) at 750 m.

The capsule propulsion system should provide the capability to achieve and maintain the specific accelerations and resulting velocities, as indicated above. The braking system should provide the ability to stop the capsule on a designated track section, taking into account the velocities obtained at the start of the braking process. The assumed mass of the capsule is 350 kg, so the kinetic energy will reach a maximum value of approximately 1.7 MJ.

Table 2 presents estimated values of accelerations and decelerations in relation to the gravities of Earth, Mars, and the Moon.

Table 2.

Preliminary assumptions of operational parameters for Earth, Mars, and lunar gravity simulations comparing vacuum and air resistance conditions at different acceleration distances. Source: Authors′ own work.

3.3. Drop Capsule: Design Features

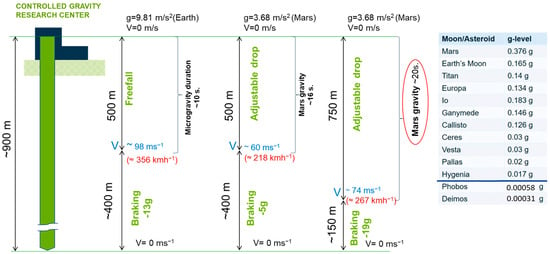

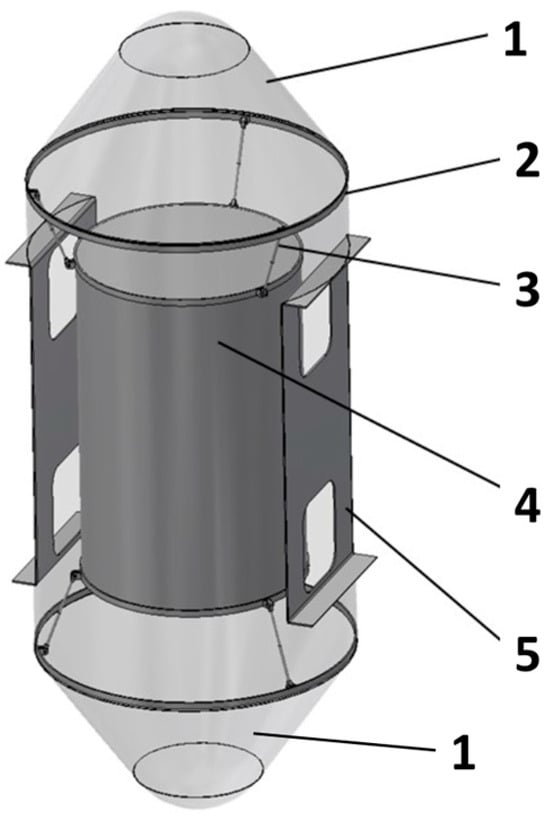

The complete drop capsule’s assembly, with its main dimensions, is presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Drop capsule model with a trolley and rails (diameters in [mm]).

The capsule (Figure 5) has been designed in the form of a cylinder (1) ended on both sides with conical covers. Such a shape should ensure low resistance during the capsule’s fall. Composite materials are taken into account for construction to reduce overall mass while maintaining structural integrity. Inside the capsule, there is a research chamber (2), which is isolated from the capsule housing by damping connectors (3). These connectors, positioned at both ends of the chamber, are mounted to reinforcing rims (4) integrated into the cylindrical body. The damping parameters will be optimized through numerical analysis to achieve the desired vibration isolation characteristics.

Figure 5.

Capsule structure (1—capsule housing, 2—research chamber, 3—damping element, 4—reinforcing rim, and 5—mounting plate).

The selection of appropriate parameters, such as hardness and length of the shock absorber stroke, will be key in ensuring stabilization. In addition, the mass of the chamber is evenly distributed to minimize changes in the center of the mass during movement. This can help to maintain stability. An additional stabilizing element could be a rotating mass (gyroscope) mounted on the moving part (capsule), which maintains a constant orientation with respect to gravity. This can help to eliminate oscillations and maintain stability.

The three damping connectors are distributed evenly around the chamber’s circumference at each end, forming a six-point suspension system. This configuration isolates the experimental payload from unwanted vibrations and mechanical shocks generated during capsule motion. The selection of damping parameters (such as hardness and length of the shock absorber stroke) is critical for achieving optimal vibration isolation performance. The chamber design incorporates uniform mass distribution to minimize center-of-gravity shifts during operation, thereby enhancing positional stability. Future design iterations may incorporate an active gyroscopic stabilization system to maintain constant orientation relative to the gravitational field and suppress residual oscillations.

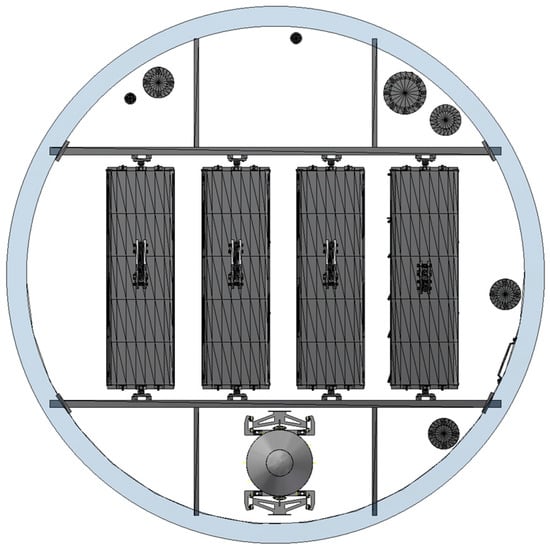

The capsule has been equipped with mounting plates (5), which bind the structure to the braking trolleys. The placement of the drop capsule in a shaft with a diameter of 7.5 m is presented in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Top-down view of drop capsule within 7.5 m-diameter mine shaft.

In the cross-section, there is the arrangement of four parallel damping elements or shock absorbers. They are positioned symmetrically along the capsule’s length. These damping connectors are distributed around the research chamber’s circumference, forming part of the six-point suspension system that isolates the experimental payload from vibrations and mechanical disturbances generated during motion.

The figure also shows the mounting plates that interface the capsule with the braking trolley system. The trolley framework, equipped with guide rollers and electromagnetic elements, maintains the capsule’s centered position and ensures stable descent along the mining drop shaft.

Around the circumference of the capsule configuration, eight small circles are visible at strategic points. These represent either the guide roller contact points or the positions of electromagnetic coil interfaces, depending on the operational phase. The symmetrical distribution of these elements underscores the engineering principle of maintaining uniform support and minimizing lateral loading during the high-velocity descent.

The substantial clearance between the capsule and shaft walls provides several important functions: it prevents direct contact between the moving apparatus and the shaft structure, accommodates minor deviations from vertical shaft alignment, allows for thermal expansion of the components, and provides access space for emergency braking mechanisms if required. This design feature is particularly important when taking into account that numerical simulations have indicated shaft deviations of up to 1 degree from vertical over-extended distances.

The top-down perspective shows how the capsule’s cylindrical geometry and central positioning enable the electromagnetic propulsion system to function effectively. Permanent magnets integrated into the capsule structure interact with electromagnetic coils positioned along external rails, while guide rollers maintain positional stability and assist in emergency braking scenarios.

This visualization is fundamental for understanding the mechanical configuration of the proposed facility, illustrating how the existing mine shaft infrastructure can accommodate advanced propulsion and control technologies while ensuring the safety redundancies that are essential for continuous research operations.

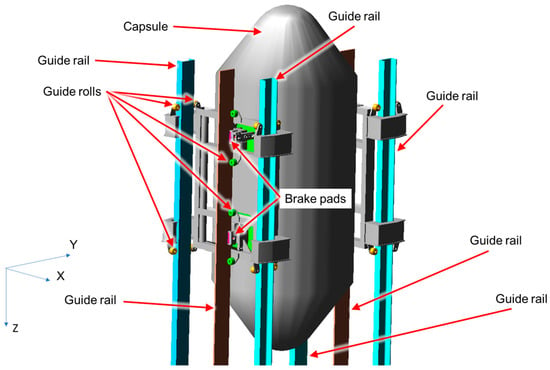

3.4. Braking System Concept

In this chapter, the braking system concept is presented. The trolley is equipped with guide rollers that provide stability and precise guidance during emergency braking. These rollers are fabricated from materials with low friction coefficients to reduce rolling resistance and wear. Strong neodymium magnets are used as magnetic elements, mounted within the undercuts of the trolley. This configuration ensures effective magnetic attraction and stable contact between the trolley and the magnetic track. To enhance operational safety, the system incorporates an emergency braking mechanism that can be activated in the event of magnetic element failure or other malfunctions. This safety function is provided through four emergency brakes—two installed on each trolley.

For additional safety under emergency or critical conditions, an auxiliary braking system is integrated. This brake must generate a sufficient braking force proportional to the capsule’s mass and velocity. The response time of the brake is a critical parameter to ensure immediate stopping capabilities when required. Durability and mechanical strength are also essential to maintain braking efficiency over prolonged operational periods.

The incorporation of redundant braking systems, providing alternative braking methods, further enhances overall operational safety. Adjustable braking characteristics enable tuning of the braking force according to specific experimental or mission conditions. In emergency scenarios, the braking system should minimize risk and ensure the safe termination of the capsule’s motion. Moreover, the brake design must facilitate ease of maintenance and repair while fully complying with applicable safety standards.

As part of the conceptual work, a series of simulations were carried out to estimate the level of free-fall time, maximum speed, and the necessary braking forces and acceleration/deceleration values. For this purpose, a computational model was built. There was a possibility of varying this model and the simulations. Based on the developed computational model, simulations of the kinematics and dynamics of multi-body systems (MBS method) were performed. It was assumed that all parts in the model were rigid bodies. Thanks to the possibility of varying the computational model during simulation, the possibility of free fall of the capsule (in the event of a vacuum in the shaft) was taken into account, and a variant with air resistance was also obtained. Air resistance was defined as a vector dependent on the capsule’s descent velocity. The value of the gravity vector was also assumed to correspond to Earth conditions (9.81 ms−2), the gravity on Mars (3.68 ms−2), and conditions on the Moon (1.62 ms−2). The following paragraphs present detailed relationships, equations, and sample calculations and results.

The load-bearing structure of the capsule has been simplified to consist of four fixed rails (Rails 1–4) and two flat bars, which—in addition to controlling the track of motion—serve to brake the set using four pairs of brake blocks. The computational model is composed of the following components, as shown in Figure 7:

Figure 7.

MBS computational model of the capsule’s load-bearing structure.

- 54 rigid bodies;

- 32 rotational constraints;

- 8 sliding constraints;

- 12 anchoring constraints;

- 81 contact models;

- 6 elastic-damping elements (shock absorbers);

- 9 force vectors.

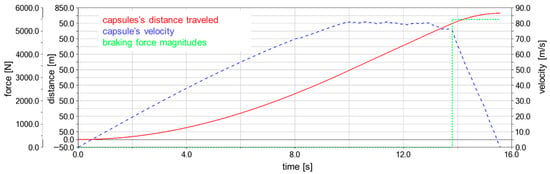

Based on simulations of various scenarios, the maximum descent speed of the capsule under different conditions was estimated, Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Maximum capsule descent velocity in each variant.

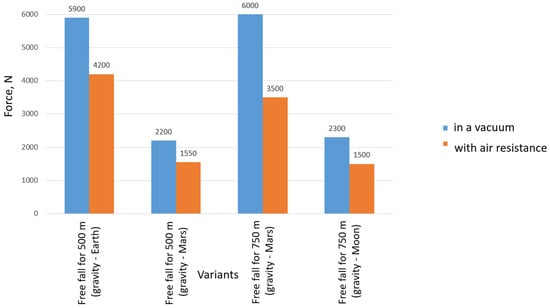

The force required to stop the falling capsule was also estimated. It was assumed that the fall distance and braking distance would not exceed 900 m. The braking force values for each variant are shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

The braking force values for each variant.

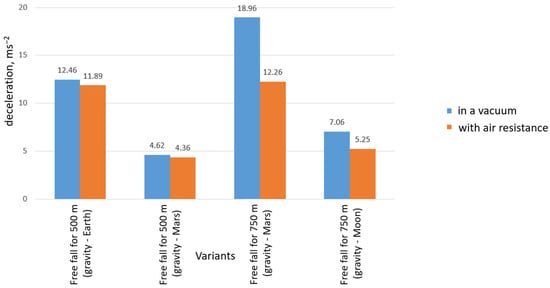

The maximum deceleration occurring during the braking process was also estimated for each variant. This is an important parameter that may affect the damage or lack of damage to the tested component or measuring equipment. The maximum braking deceleration value is shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Maximum deceleration value during braking for the various variants.

The assumed parameters for the braking system’s design are as follows:

- Maximum capsule speed: v = 98 m/s;

- Braking force: Fh = 5500 NF;

- Braked mass: m = 350 kg;

- Friction coefficient: f = 0.4;

- Number of brakes: n = 4.

For the above parameters, the braking distance was calculated from the following equation:

Assuming that a total of 400 m of track is allocated for braking, the calculated braking distance confirms that the braking system—with all four brakes operating at maximum load—provides a sufficient safety margin.

The EV 024 EFM brake, manufactured by Ringspann, is one of the options being considered for use in the system. This electromagnetic brake operates with spring pressure, ensuring safe and immediate stopping of the device—an essential function in emergency situations. The technical specifications of the brake are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Technical parameters of EV 024 EFM brake.

3.5. Capsule Design and Internal Configuration

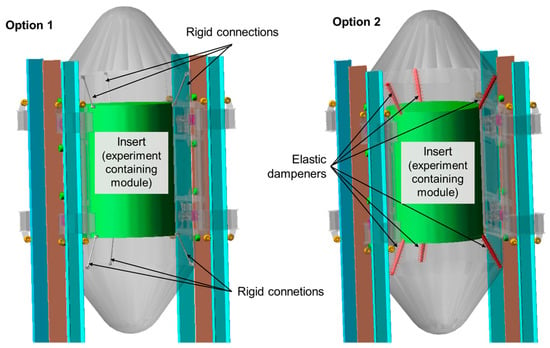

The capsule contains an internal insert that serves as an accommodation space for experimental objects and measurement equipment subjected to reduced-gravity testing. Two design options were developed and evaluated. In Option 1, the insert is rigidly connected to the capsule without a relative motion capability. In Option 2, the insert is suspended on six elastic-damping elements (shock absorbers). This second configuration aims to filter vibrations resulting from guide roller–track interactions. A comparative view of both options is presented in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Design options regarding the capsule insert: with a rigid connection of the insert with the capsule (left); with elastic dampeners as connectors of the insert with the capsule (right).

The mass distribution of the individual solid components in the 3D geometrical model is as follows:

- Capsule: 331.36 kg;

- Insert: 49.54 kg;

- Guide roller (×32): 0.394 kg each;

- Brake pad (×8): 0.4227 kg each.

The route length in the computational model corresponds to the mine shaft depth where the system can be installed. The model assumes a 900 m drop path length.

A gravitational acceleration of 9.80665 m/s2 is applied in accordance with the positive Z-axis direction of the global coordinate system. To simulate capsule braking, eight force vectors pressing the brake pads against rails 5 and 6 were defined, each with a magnitude of 5.5 kN. The friction coefficient between the brake pads and rails was set to 0.4.

The contact interactions between the brake pads and rails 5 and 6 were defined with the following parameters:

- Stiffness coefficient: 9 × 1099 × 109 N/m;

- Damping coefficient: 1 × 1051 × 105 Ns/m;

- Static friction coefficient: 0.4;

- Dynamic friction coefficient: 0.4.

The contact interactions between the guide rollers and their corresponding rails were defined with the following parameters:

- Stiffness coefficient: 7 × 1097 × 109 N/m;

- Damping coefficient: 2000 Ns/m;

- Static friction coefficient: 0.3;

- Dynamic friction coefficient: 0.1.

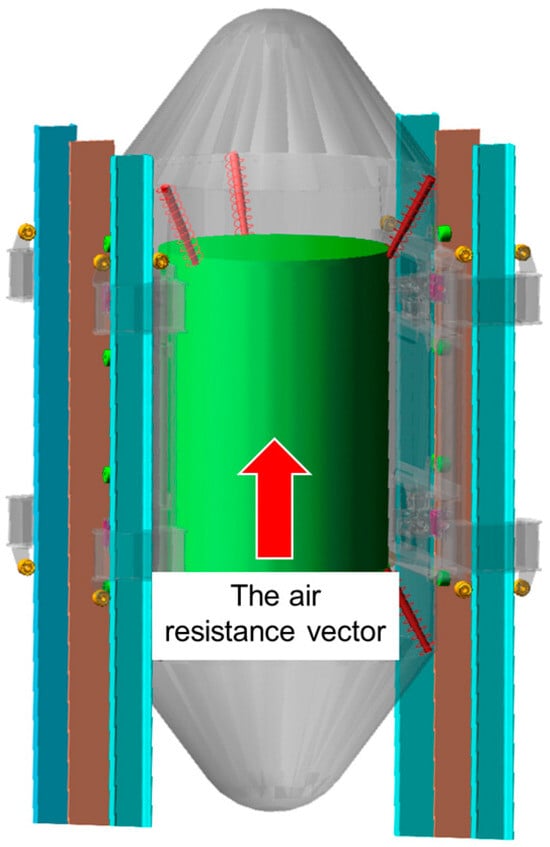

3.6. Air Resistance Calculations

During free fall, the capsule experiences aerodynamic drag forces. In the computational model, an air resistance vector was defined and applied to the capsule’s center of mass, acting vertically opposite to the direction of motion (negative Z-axis direction), Figure 12.

Figure 12.

The air resistance vector.

The magnitude of the air resistance vector was calculated according to the following equation:

where

- Fop—drag force [N];

- C—drag coefficient;

- S—cross-sectional area of the body [m2];

- ρ—density of the medium (fluid) [kg/m3];

- v—velocity [m/s].

Based on the literature data [52], the following values were adopted for the calculations:

- C = 0.5;

- ρ = 1.225 kg/m3.

The capsule’s cross-sectional area was calculated as the following:

The air resistance vector magnitude was calculated as the following:

The resulting air resistance vector magnitude is expressed as the following:

where

- v—capsule speed in the vertical axis [m/s].

It should be noted that the value of the air resistance vector is strictly dependent on the capsule’s speed. This fact has been taken into account in the calculation model, and the value of the resistance vector changes dynamically as the speed of the falling capsule changes.

3.7. Damping System Configuration

In Option 2 of the capsule (Figure 11), six elastic-damping elements were defined to function as insert dampers. Within this option, two sets of damping parameters were evaluated:

Configuration 1:

- Stiffness coefficient: 30,000 N/m;

- Damping coefficient: 700 Ns/m.

Configuration 2:

- Stiffness coefficient: 20,000 N/m;

- Damping coefficient: 1500 Ns/m.

Table 4 shows the maximum, minimum and RMS values of accelerations recorded in the three axes, X, Y, Z, in relation to the capsule and test insert in configurations 1 and 2.

Table 4.

Maximum, minimum, and RMS values of acceleration in configurations 1 and 2.

When analyzing the results obtained, it can be seen that the proposed vibration isolation (damping) system for the test insert does not significantly affect the vibration level on the vertical axis. However, on both the X and Y horizontal axes, a clear reduction in the impact of capsule vibrations on the test insert can be observed.

Based on vibration damping requirements, configuration 2 was selected as the optimal design, providing effective isolation of the experimental insert from capsule vibrations while maintaining structural stability.

3.8. Shaft Verticality and Real-World Deviations

Simulations were conducted considering disruptions to the shaft’s verticality. Over a distance of 300 m, the shaft was modeled with a 1° deviation from the vertical direction. The path’s configuration is illustrated in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

View of the capsule’s descent path: without disturbances (left), with disturbed linearity (right).

Even minor structural imperfections inherent to the aged mine shafts do not significantly affect the operational viability of the proposed facility. The 10 m lateral deviation over 300 m corresponds to a slope of approximately 3.3%, which lies within the design tolerances of the electromagnetic suspension and mechanical braking systems. The 3.25 m clearance on each side between the 1 m-diameter capsule and the 7.5 m shaft diameter provides total clearance envelope of a 6.5 m, entirely accommodating this predicted deviation.

Figure 14 presents data regarding the capsule’s velocity, distance traveled, braking force magnitudes, and activation times. Based on these data, the capsule’s braking distance was calculated.

Figure 14.

Relations between capsule velocity, distance traveled, braking force magnitude, and activation time.

Braking initiation occurs at 13.8 s. At this point, the capsule reaches a velocity of 75.31 m/s and has traveled 748.3 m. At 15.57 s, the capsule’s velocity decreases to 0 m/s, indicating a complete stop. The total distance traveled is 814.714 m, yielding a braking distance of 66.414 m over a braking duration of 1.77 s.

The maximum, minimum, and root-mean-square (RMS) acceleration values on the vertical axis for both the capsule and the insert throughout the simulation are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Maximum, minimum, and effective acceleration values on the vertical axis of the capsule and the insert during the entire simulation.

The maximum, minimum, and mean forces generated in each shock absorber are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Forces generated in each of the shock absorbers.

This simulation underscores an essential engineering consideration: Polish coal mines, having operated continuously for over a century, exhibit structural characteristics typical of aging underground excavations. Minor subsidence and lateral shifting of the shaft walls are commonplace. By demonstrating—through numerical modeling—that the control system and suspension architecture can maintain safe and stable descent under such realistic conditions, the study validates the practical feasibility of the proposed concept. The electromagnetic guidance coils and mechanical rollers are calibrated to correct minor trajectory deviations in real-time, ensuring that the capsule remains centered and stable throughout its descent.

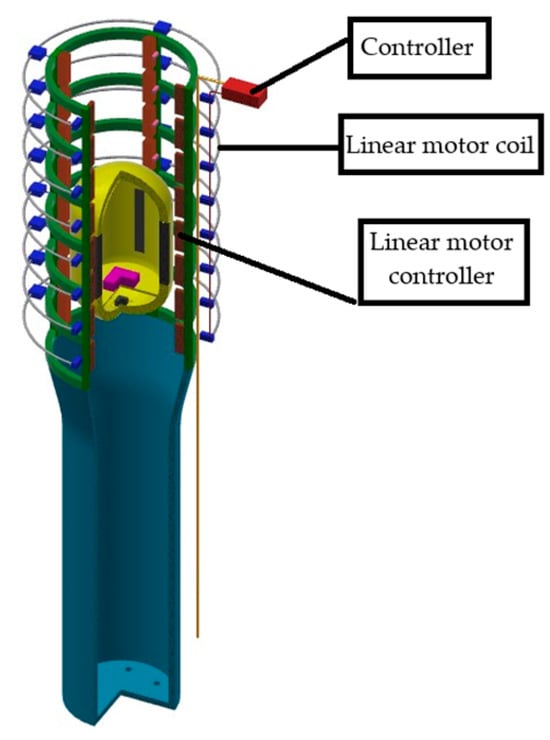

3.9. Propulsion System

It is not possible to create a vacuum in the shaft; therefore, to ensure weightlessness during the capsule’s fall, it will be necessary to accelerate it and counteract air resistance as it falls down the mine shaft. The proposed design incorporates an electromagnetic coil system mounted on the external track structure, which constitutes the capsule’s drive mechanism (Figure 15). The capsule is equipped with permanent magnets. The electromagnetic guide design is compatible with V-maglev technology. Implementation of this specialized system requires collaboration with companies specializing in electromagnetic propulsion systems.

Figure 15.

Drop shaft conception.

The capsule’s drive system operates based on phenomena occurring in synchronous linear drives. The capsule’s descent velocity is controlled through electromagnetic field generation via the coil array. To ensure correct operation, the system incorporates a central shaft equipment controller that manages the synchronization of individual linear motor coil controllers. A synchronization signal is generated by a transmitter, the frequency of which varies according to predefined time-dependent characteristics. These signals determine which coils are energized at any given moment (specifically, those located directly ahead of or behind the capsule).

An accelerometer integrated within the capsule monitors acceleration exclusively for experimental control purposes. The electromagnetic drive requirements differ significantly from those of conventional linear motors available commercially. Since the objective is to create reduced-gravity conditions, damping of transverse capsule vibrations and electromagnetic drive-induced vibrations is essential. Vibration damping necessitates increased distance (clearance) between magnets and coils. Additionally, the system must accommodate a substantial frequency variation from the minimum to maximum capsule velocity, requiring specialized linear motor magnet wire materials.

The characteristics distinguishing this system from standard, commercial industrial linear drives are as follows:

- The broad frequency range of the linear drive windings;

- The vertical configuration and extended drive length (approximately 900 m);

- The specially modified windings designed to ensure smooth acceleration and minimize vibrations arising from motor operation.

The specific performance and safety requirements for the electromagnetic braking system preclude the use of standard industrial automation components. Therefore, a dedicated braking system specifically designed for microgravity drop tower applications must be developed.

3.10. Control and Monitoring Architecture

The control architecture is divided into two main systems: one located above the shaft and the other one integrated within the capsule. The upper system manages magnetic drives, monitoring, measurement, and diagnostic functions. The onboard capsule system includes the following:

- A central controller;

- Acceleration sensors (accelerometers);

- A wireless communication system interfacing with the shaft control system;

- A friction emergency brake control system.

The main functions of the capsule’s control system include the following:

- Acquisition of measurement data;

- Transmission of data to the shaft’s control system;

- Controlling the emergency friction brake.

This configuration enables the capsule to achieve accelerations equivalent to the Earth’s gravitational acceleration, thereby generating weightlessness or zero-gravity conditions within the moving capsule. In this design, permanent magnets are integrated into the capsule’s structure, while electromagnetic coils are placed along the guide rails. Moreover, the capsule is accelerated by the combined action of gravitational forces and an electric propulsion system designed to counteract aerodynamic drag. The system exhibits a high level of structural and control complexity. Motion control is achieved through the sequential activation of individual electromagnetic coils, ensuring smooth and continuous operation within the required kinematic parameters.

Velocity and acceleration control are carried out with the use of a series of optical sensors (light barriers) positioned at predetermined intervals along the track. During operation, the time required for the capsule to traverse the distance between the sensors is recorded. These measurement data are transmitted in real time to the control system, allowing the operator to adjust the operating parameters dynamically during the experiments.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The proposed solution, once implemented, will contribute to at least two areas: (i) space science and (ii) the green transformation of mining facilities.

The design of the controlled-gravity facility integrates modern materials, advanced magnetic propulsion technologies, and robust safety and control systems, resulting in a versatile platform capable of supporting experiments under various gravitational conditions.

The comparative analysis of eleven operational and historical drop tower facilities (Table 1) reveals substantial variation in key performance parameters. The microgravity duration—arguably the most critical parameter for experimental utility—ranges from 2.0 s (QUT Microgravity Drop Tower [95]) to the historical record of 10 s achieved at Japan’s JAMIC Drop Shaft Facility [96,97]. The JAMIC facility, constructed within the decommissioned Mitsui Sunagawa coal mine (operational from 1989 to 2003), demonstrated the technical feasibility of deep-shaft microgravity research, completing 4770 experiments over its operational lifetime. However, the facility’s closure was caused by extremely high operational costs, estimated at approximately JPY 2.5 million per test, which underlines the necessity for cost-effective operational models in future implementations.

The Bremen Drop Tower (ZARM), representing the current state-of-the-art in Europe, achieves microgravity durations of 4.74 s in drop mode and, uniquely, 9.3 s when utilizing its catapult system installed in 2004. The catapult mechanism accelerates the 300–500 kg capsule to 48 m/s within 0.28 s using a pneumatic pressure differential between vacuum and pressurized tanks. This system demonstrates that achieving experiment times exceeding 9 s would require a conventional above-ground tower approximately 500 m tall, an economically and structurally impractical proposition [89].

The microgravity quality, quantified as residual acceleration, exhibits significant variation. The German facilities—Fallturm Bremen [98] and Einstein-Elevator [91,99]—set the benchmark at 10−6–10−7 g. Recent measurements at the Beijing Drop Tower, utilizing sensitive accelerometers, confirmed residual accelerations higher than for single-capsule configurations and for double-capsule systems [100,101,102].

The proposed electromagnetic propulsion and braking system represents a technological advancement over conventional mechanical systems. To date, only the Einstein-Elevator at Leibniz University Hannover employs electromagnetic linear motors for capsule acceleration, achieving accelerations of up to 22 g over a 40 m facility height. The Einstein-Elevator’s linear drive accelerates a 2700 kg system (gondola, traverse, and experiment) at 5 g, reaching 20 m/s over the first 5 m. This facility achieves an unprecedented repetition rate of up to 300 experiments per day, dramatically reducing experimental cycle time and operational costs per test. The proposed Polish facility for research under reduced-gravity conditions extends this concept to velocities approaching 98 m/s—nearly double the Einstein-Elevator’s maximum—necessitating magnetic drive technologies compatible with maglev systems rather than conventional industrial linear motors. Research on electromagnetic control systems for capsule navigation has demonstrated the feasibility of generating magnetic gradients of 0.175 T/m (82.5 mN) for attraction and 0.105 T/m (49.5 mN) for dragging at distances of 70 mm. However, scaling these systems for high-velocity, high-mass applications while maintaining a microgravity quality below remains a significant engineering challenge.

The transition from mechanical to electromagnetic guidance systems eliminates the frictional forces associated with conventional guide rails, a critical consideration at velocities approaching 100 m/s. The numerical simulations presented in this study demonstrate that magnetic self-compensation stabilization can maintain capsule centering even under realistic shaft deviation scenarios (1° over 300 m), resulting in a lateral displacement of approximately 10 m—well within the 6.5 m clearance envelope provided by the 7.5 m shaft diameter. Maximum braking acceleration constitutes a critical constraint on experimental payload design. The surveyed facilities exhibit braking accelerations ranging from 5 g (Einstein-Elevator) to 65 g (NASA Zero Gravity Research Facility [103]). The proposed system, utilizing EV 024 EFM electromagnetic brakes with a 5500 N clamping force and a friction coefficient of 0.4, achieves calculated braking distances of approximately 191 m from terminal velocity of 98 m/s. This represents a significant safety margin within the allocated 400 m braking zone.

An analysis reveals that the Japanese Drop Shaft Facility, despite its record of a 490 m drop height, limited braking acceleration to only 8 g, suggesting that extended drop distances enable gentler deceleration profiles—a favorable characteristic for sensitive biological and materials science experiments. The proposed Polish facility, with 900+ meters of total shaft length, could theoretically optimize the trade-off between microgravity duration and payload protection more effectively than current short-tower designs. Several technical challenges require resolution during subsequent development phases. First, the electromagnetic drive system must be validated at the proposed 98 m/s operational velocity—significantly exceeding any current implementation. Collaboration with maglev technology specialists will be essential, as commercial linear motors typically operate at maximum velocities of 50 m/s. The decision between vacuum and atmospheric operation fundamentally impacts microgravity quality, operational complexity, and cost. NASA’s Zero Gravity Research Facility evacuates its 1700 m3 chamber to 0.05 torr (approximately 6.67 Pa), requiring one hour per cycle. This reduces aerodynamic drag to below , but the lengthy evacuation process limits throughput to approximately two experiments per day.

The proposed facility’s shaft volume (assuming a 7.5 m diameter and 900 m length: approximately 39,760 m3) exceeds NASA’s chamber by a factor of 23, suggesting that evacuation times could exceed 20 h using conventional pumping systems— which is economically prohibitive for high-throughput operations. Alternative approaches, such as the Einstein-Elevator’s small-volume gondola (requiring only minutes to evacuate) or atmospheric operations with aerodynamic drag compensation via electromagnetic drive, should be considered.

Numerical modeling incorporating air resistance () demonstrates that atmospheric drag at 98 m/s generates approximately 2300 N of opposing force on the 1 m-diameter capsule. This necessitates continuous electromagnetic propulsion to maintain free-fall acceleration, increasing energy consumption but eliminating evacuation delays. The trade-off between microgravity quality ( in vacuum vs. with drag compensation) and operational efficiency (2 tests/day vs. potential 10–20 tests/day) requires careful economic and scientific evaluation.

Transformation of mining and post-mining regions should comply with the provisions of the European Green Deal, follow just transition principles, and meet the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which are met by the proposed way of adopting a mine shaft into the experimental facility of a research center.

According to the European Commission report, the regions most affected by the transformation towards independence from coal in Europe are as follows [104]:

- Czechia (several regions);

- Germany (Ruhr area);

- Germany (Lausitz area in Brandenburg in Saxony);

- Spain;

- Netherlands (Limburg);

- Poland (Upper Silesia, Małopolska, and Lubelskie).

Analyzing the examples of transition periods and their impact on unemployment in the coal mining sector (Table 7), Poland is the second country in which job reduction was present due to the transformation from coal dependency.

Table 7.

Transition periods and job reductions in selected European countries.

While the construction of a reduced-gravity research facility alone cannot substantially reduce the problem of the employment losses associated with the coal phase-out, it represents a strategic and forward-looking approach that supports sustainable regional development. Such a project would provide temporary employment for former mine workers during the construction phase and offer long-term technical and operational positions in the facility.

Moreover—what is important from the point of view of sustainable development—the proposed project would transform a structure that otherwise would be destined for decommission into a high-value scientific asset. This would result in varied benefits. Firstly, using the existing mine infrastructure instead of building a new research facility is an efficient use of resources. Secondly, a controlled-gravity research center could attract scientists and students, which would contribute to the development of the local community. Generally, once the proposed research center is created, relations with the following Sustainable Development Goals can be indicated:

- SDG 8: Decent work and economic growth. Mine closures cause layoffs, but repurposing mine infrastructure into a reduced-gravity research center will create jobs during both construction and operation, as well as in surrounding businesses that will arise along with the increased attractiveness of the region. The center will employ skilled workers, including mining specialists, and require scientific, engineering, administrative, and management staff. It will also provide unique professional development opportunities for space science.

- SDG 9: Industry, innovation, and infrastructure. Repurposing mine infrastructure gives it a new operational lifecycle that supports research and development. The center will create positions for researchers, engineers, and technicians, while attracting private R&D investment. As a highly innovative and unique facility, it will offer opportunities for the region, the country, Europe, and beyond. Research in reduced-gravity environments produces intellectual property, scientific publications, and commercially viable technologies, enabling effective technology transfer. This will strengthen Poland’s—and Europe’s—research and innovation capacity.

- SDG 11: Sustainable cities and communities. The reduced-gravity research center can support urban and community revitalization in Silesian mining towns affected by long-term economic decline and depopulation after mine closures. It can attract skilled workers, generate local economic activity, and improve economic and social conditions. The resulting activity can help finance better public services, infrastructure, and community facilities. Converting industrial heritage into forward-looking research infrastructure may also strengthen civic pride and local commitment to development.

- SDG 12: Responsible consumption and production. Reusing mine structures minimizes new material needs and waste, while repurposing them for a forward-looking reduced-gravity research center aligns with global space science strategies. This innovative approach treats coal facilities as R&D assets rather than demolishing them.

- SDG 17: Partnerships for the goals. The development and operation of a reduced-gravity research center require multi-sector partnerships among universities, research institutions, private companies, and governments. Such facilities typically involve international collaborations, integrating Polish and European researchers into global networks. The Silesian center could also serve as a platform for EU-funded projects.

- SDG 4: Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all. A reduced-gravity research center in the Silesian Voivodeship will provide unprecedented access to research for space sector companies, universities, and institutes at regional, national, and European levels. It can offer opportunities for students, early career scientists, and professionals through teaching labs, apprenticeships, advanced training, seminars, and teacher development programs in reduced-gravity research and related fields. This enhances scientific literacy, supports ESA-aligned projects, and promotes lifelong learning.

This article presents only a fragment of a concept developed for the potential construction of a controlled-gravity research center adopting the existing infrastructure of a mine shaft. It presents a variant assuming a certain stiffness of the shock absorbers, the presence of air in the shaft during experiments (and consequently the presence of air resistance), and the non-linearity of the shaft.

Based on the entirety of the research that has been conducted and the simulations that have been carried out, a set of conclusions have been drawn:

- To ensure a constant level of acceleration at the level of Earth’s acceleration during the free-fall phase and thus extend the time the capsule stays in a state of weightlessness, an external source of propulsion accelerating the capsule should be used. This is due to the decrease in acceleration, resulting from air resistance, which increases proportionally with the increase in speed (non-linearly).

- Introducing a damping system for the insert in which the measuring apparatus is to be located significantly reduces the magnitude of vibrations resulting from the contact of guide rollers with rails. This can be observed on the acceleration values of the capsule and insert in the horizontal axes. The use of this type of suspension of the insert does not significantly affect the acceleration values in the vertical axis.

- The values of the shock absorber parameters (stiffness coefficient and damping coefficient) have a significant impact on the way and quality of filtering accelerations in the horizontal axes. This was demonstrated by conducting simulations with two types of shock absorbers (different values of stiffness and damping coefficients). This implies that the appropriate parameters should be selected depending on the mass of the insert along with the research apparatus. It may be worth considering the development of a series of shock absorbers that will be replaced depending on the mass of the object under study.

- In the model, minimal displacements in the shock absorber attachments were deliberately introduced (the right or left ear of the handle was chosen, not the central point), thus highlighting the difference in the load on the shock absorbers and the difference in their length change. This occurs when the test object/apparatus (measurement computer, cameras, and stands, etc.) inside the insert is unsymmetrically located in it, which results in a lack of balance of the insert.

- When choosing shock absorbers that are too compliant, there is a risk of collision of the insert with the capsule as a result of too large displacements of the insert relative to the capsule. Therefore, it is necessary to introduce displacement limiters.

- Research under reduced-gravity conditions corresponding to other planets, the Moon, etc., requires the introduction of a system for accelerating or braking the capsule in the free-fall phase.

- Disturbance of the linearity of the shaft significantly limits the operation of the drop tower. Firstly, large overloads occur as a result of the guide rollers hitting the rails in the area of disturbance of the linearity of the route. Secondly, as a result of the disturbance of the “vertical” mode of the route, some of the guide rollers remain in contact with the rail for a longer time than in the case of a straight track. This introduces additional movement resistances resulting from the friction of the rollers on the rail, resistances in the bearings, and inertia forces, etc., leading to a significant reduction in the maximum free-fall speed while introducing large disturbances in the form of vibrations, which may prevent experiments from being conducted inside the capsule.

The main technical obstacle taken into account regarding the proposed concept was the impracticality of creating a vacuum within a mine shaft. This resulted in novel design idea, different to those in the existing reduced-gravity research facilities, where a vacuum is created which eliminates air resistance, a significant factor limiting maximum fall velocity. Achieving vacuum conditions would require sealing the entire shaft, and evacuating such a large volume of air would substantially reduce efficiency and increase experimental costs. Consequently, the air resistance generated during the capsule’s descent has to be taken into account, as this resistance influences the maximum velocity reached. Assuming an innovative approach that allows for acceleration adjustments that reflect the conditions prevailing on different celestial bodies, it is necessary to design an appropriate motion control system. This system should enable both the acceleration and deceleration of the capsule during the descent phase and allow for the necessary adjustments to be made in order to maintain the desired level of acceleration. The development of this system will be the subject of further work.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.M., J.T., B.O., M.R. and K.S.; methodology, D.M. and J.T.; formal analysis, J.T. and K.S.; investigation, J.T. and B.O.; writing—original draft preparation, B.O., M.R. and J.T.; writing—review and editing, B.O., M.R. and J.T.; visualization, D.M., M.R. and K.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions—The European Green Deal (COM(2019) 640 Final). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52019DC0640 (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- European Commission. EU Approach to SDGs Implementation. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/sustainable-development-goals/eu-approach-sdgs-implementation_en (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- International IDEA. The European Union Voluntary National Review 2023. Available online: https://www.idea.int/un-and-democracy/library/european-union-voluntary-national-review-2023 (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Worden, S.; Svobodova, K.; Côte, C.; Bolz, P. Regional post-mining land use assessment: An interdisciplinary and multi-stakeholder approach. Resour. Policy 2024, 89, 104680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Xu, Q.; Wei, X. Progress of mine land reclamation and ecological restoration research based on bibliometric analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woźniak, G.; Bakar, J.; Dyczko, A.; Jarosz, J.; Ryś, K.; Radosz, Ł.; Kaul, S.; Adamik, K.; Besenyei, L.; Prostański, D. The diversity and plant species composition of the spontaneous vegetation on coal mine spoil heaps in relation to the area size. Min. Mach. 2023, 1, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrychová, M.; Svobodova, K.; Kabrna, M. Mine reclamation planning and management: Integrating natural habitats into post-mining land use. Resour. Policy 2020, 69, 101882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biegańska, J.; Tora, B.; Sinka, T.; Čablík, V.; Hlavatá, M. Reclamation and Revitalization of Post-Mining Sites—Ups and Downs. Acta Montan. Slovaca 2023, 28, 637–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malec, M.; Stańczak, L.; Ricketts, B. Just Transition of Post-Mining Areas—Technical, Economic, Environmental and Social Aspects. Min. Mach. 2023, 41, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmiela, A.; Smoliło, J. The method for preliminary estimation of expenditures and time necessary for liquidation of a mining plant. Min. Mach. 2023, 41, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalik, W.; Wit, H.; Pepłowska, M.; Kryzia, D.; Gawlik, L.; Komorowska, A. Socio-cultural challenges of coal regions and their transformative capacities—A case study of Silesia. Gospod. Surowcami Miner.—Miner. Resour. Manag. 2024, 40, 167–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirshenava, S.; Osanloo, M. Strategic planning of post-mining land uses: A semi-quantitative approach based on the SWOT analysis and IE matrix. Resour. Policy 2022, 76, 102585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirshenava, S.; Osanloo, M. Mined land suitability assessment: A semi-quantitative approach based on a new classification of post-mining land uses. Int. J. Min. Reclam. Environ. 2021, 35, 743–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, D.; Barnes, T.; Porter-Smith, R.; Ruberto, D.; Sun, H.; Zeng, S. Workshop processes to generate stakeholder consensus about post-mining land uses: An Australian case study. Resour. Policy 2021, 70, 101838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mborah, C.; Bansah, K.J.; Boateng, M.K. Evaluating alternate post-mining land-uses: A review. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 5, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Agarwal, S.; Prabhat, A. A multi-criteria decision framework to evaluate sustainable alternatives for repurposing of abandoned or closed surface coal mines. Front. Earth Sci. 2024, 12, 1330217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarczyk, K.; Dobrzaniecki, P.; Woszczyński, M.; Bałaga, D.; Szewerda, K.; Dymarek, A. Wind Power Plants and Selected Technical and Economic Aspects of Their Construction on Mine Heaps. Energies 2023, 16, 6827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biały, W. Revitalization of Mining Dumps: Assessment of Possibilities. Prod. Eng. Arch. 2022, 28, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Energy. Repurposing Mines for Tourism and Culture: A Combined Case Study of Transformation Examples from Dolní Oblast Vítkovice Mine in Ostrava, Czechia and Golpa-Nord in Lusatia, Germany; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2025; ISBN 978-92-68-25054-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Głąbińska, D.; Manecki, M.; Puławska, A.; Zawadzki, D. Post-Mining Sites as Drivers of Geoheritage and Sustainable Tourism: A Study of Visitor Dynamics in Polish Underground Tourist Mines (2019–2024). Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2025, XXVIII, 514–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pijet-Migoń, E.; Migoń, P. New Geo- and Mining Heritage-Based Tourist Destinations in the Sudetes (SW Poland)—Towards More Effective Resilience of Local Communities. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krassakis, P.; Karavias, A.; Zygouri, E.; Koukouzas, N.; Szewerda, K.; Michalak, D.; Jegrišnik, T.; Kamenik, M.; Charles, N.; Beccaletto, L.; et al. CoalHeritage: Visualising and Promoting Europe’s Coal Mining Heritage. Mining 2024, 4, 489–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojka, Z. Second life of post-mining facilities: Mines as a tourist attraction of southern Poland. Stud. Hist. Oecon. 2023, 41, 121–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Z.; Li, J.; Wang, Y. A method for the transformation of abandoned coal mine clusters and the coordination planning of cultural tourism resources. Land 2024, 13, 2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Li, H.; Huang, X. Mining heritage reuse risks: A systematic review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Arredondo, L.H.; López-Gómez, A.; Garavito-Higuera, S.A. Exploration of mining heritage and evaluation of mining tourism potential in La Ferrería Village, mining territory of the municipality of Amagá, in the northwestern Colombian Andes. Int. J. Geoheritage Parks 2025, 13, 274–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menéndez, J.; Loredo, J.; Oro, J.M.; Vega, M. Underground pumped-storage hydro power plants with mine water in abandoned coal mines. In Mine Water & Circular Economy, Proceedings of the IMWA 2017, Lappeenranta, Finland, 25–30 June 2017; Wolkersdorfer, C., Sartz, L., Sillanpää, M., Häkkinen, A., Eds.; Lappeenranta University of Technology: Lappeenranta, Finland, 2017; Volume 1, pp. 6–13. ISBN 978-952-335-065-6. [Google Scholar]

- Barszcz, T.; d’Obyrn, K.; Korbiel, T. Experimental underground pumped-storage hydropower (UPSH). Rynek Energii 2022, 1, 56–61. [Google Scholar]

- Badura, H.; Biały, W. Extraction of methane from the closed mine “Moszczenica”. Min. Mach. 2024, 42, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Chen, S.; Liu, W.; Ren, Y.; Guo, P.; Li, Z. Underground Hydro-Pumped Energy Storage Using Coal Mine Goafs: System Performance Analysis and a Case Study for China. Front. Earth Sci. 2021, 9, 760464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Obyrn, K.; Kamiński, P.; Cień, D.; Jendrysik, S.; Prostański, D. Hydrogeological and Mining Considerations in the Design of a Pumping Station in a Shaft of a Closed Black Coal Mine. Energies 2024, 17, 3297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado, R.; Niemann, A.; Wortberg, T. Underground pumped-storage hydroelectricity using existing coal mining infrastructure. In Proceedings of the 36th IAHR World Congress, The Hague, The Netherlands, 28 June–3 July 2015; Mynett, A., Ed.; International Association for Hydro-Environment Engineering & Research: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 3592–3599. ISBN 978-1-5108-2434-8. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q.; Hou, Z.; Wu, X.; Zhang, S.; Sun, W.; Fang, Y.; Wu, L.; Huang, L.; Zhang, T. A Two-Step Site Selection Concept for Underground Pumped Hydroelectric Energy Storage and Potential Estimation of Coal Mines in Henan Province. Energies 2023, 16, 4811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Z.; Zhu, C.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, Y. Evaluation on potential of using abandoned mines for pumped storage in nine provinces of Yellow River Basin. Coal Geol. Explor. 2022, 50, 51−64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menéndez, J.; Ordóñez, A.; Álvarez, R.; Loredo, J. Energy from closed mines: Underground energy storage and geothermal applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 108, 498–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colas, E.; Klopries, E.-M.; Tian, D.; Kroll, M.; Selzner, M.; Brücker, C.; Khaledi, K.; Kukla, P.; Preuße, A.; Sabarny, C.; et al. Overview of converting abandoned coal mines to underground pumped-storage systems: Focus on the underground reservoir. J. Energy Storage 2023, 73, 109153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korski, J. Solid gravity energy storage in mine shafts—Feasibility and functionality. Min. Mach. 2024, 42, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobór-Osadnik, K.; Korski, J.; Gajdzik, B.; Wolniak, R.; Grebski, W. Gravity Energy Storage and Its Feasibility in the Context of Sustainable Energy Management with an Example of the Possibilities of Mine Shafts in Poland. Energies 2025, 18, 3374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morstyn, T.; McCulloch, M.; Chilcott, M.D. Gravity energy storage with suspended weights for abandoned mine shafts. Appl. Energy 2019, 239, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, J.D.; Zakeri, B.; Jurasz, J.; Tong, W.; Dąbek, P.B.; Brandão, R.; Patro, E.R.; Đurin, B.; Leal Filho, W.; Wada, Y.; et al. Underground gravity energy storage: A solution for long-term energy storage. Energies 2023, 16, 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Wang, Y.; Sun, X.; Chen, H.; Wang, Q. Research progress and key technology of abandoned mine gravity energy storage system based on linear motor. Energy Storage Sci. Technol. 2025, 14, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colas, E.; Kukla, P.; Amann, F.; Back, S. Geological and mining factors influencing further use of abandoned coal mines—A multi-disciplinary workflow towards sustainable underground storage. J. Energy Storage 2025, 108, 115101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pous de la Flor, J.; Pous Cabello, J.; Castañeda, M.d.l.C.; Ortega, M.F.; Mora, P. New uses for coal mines as potential power generators and storage sites. Energies 2024, 17, 2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikuła, S.; Mikuła, J.; Nieśpiałowski, K.; Kalita, M.; Turczyński, K. Peaking water power plant powered by mine water. Min. Mach. 2024, 42, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoeven, R.; Willems, E.; Harcouët-Menou, V.; De Boever, E.; Hiddes, L.; Op ’t Veld, P.; Demollin, E. Minewater 2.0 project in Heerlen, The Netherlands: Transformation of a geothermal mine-water pilot project into a full-scale hybrid sustainable energy infrastructure for heating and cooling. Energy Procedia 2014, 46, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xu, Y.; Yuan, L.; Sun, Y.; Cai, Y. Analysis of geothermal heat recovery from abandoned coal mine water for clean heating and cooling: A case from Shandong, China. Renew. Energy 2024, 228, 120659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janson, E.; Gzyl, G.; Głodniok, M.; Markowska, M. Use of geothermal heat of mine waters in Upper Silesian Coal Basin, southern Poland—Possibilities and impediments. In Mine Water and Circular Economy, Proceedings of the IMWA 2017, Lappeenranta, Finland, 25–30 June 2017; Wolkersdorfer, C., Sartz, L., Sillanpää, M., Häkkinen, A., Eds.; IMWA: Lappeenranta, Finland, 2017; pp. 415–421. [Google Scholar]

- Menéndez, J.; Ordóñez, A.; Fernández-Oro, J.M.; Loredo, J.; Díaz-Aguado, M.B. Feasibility analysis of using mine water from abandoned coal mines in Spain for heating and cooling of buildings. Renew. Energy 2020, 146, 1166–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzantny, M.; Kostowski, W.; Nol, D.; Żymełka, S.; Kalina, J.; Stanek, W. The Silesian paradox: Using coal mines for district heating decarbonization—A case study on waste heat recovery from groundwater and ventilation air. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2025, 27, 101166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szewerda, K.; Michalak, D.; Matusiak, P.; Kowol, D. Concept of Adapting the Liquidated Underground Mine Workings into High-Temperature Sand Thermal Energy Storage. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smoliło, J.; Piszczek, M.; Lubryka, M.; Grycman, J. Technical aspects of liquidation of the shafts “Głowacki” in Rybnik, “Jas VI” and “Jas II” in Jastrzębie Zdrój, Poland. Min. Mach. 2023, 41, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czaja, P. Technologia Likwidacji Szybów oraz ich Infrastruktury Podziemnej i Powierzchniowej (Technology of Shaft Liquidation and Their Underground and Surface Infrastructure); Wydawnictwa AGH: Krakow, Poland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, Soil Conservation Service. Treatment of Abandoned Mine Shafts and Adits; Agricultural Engineering Note No. 1; USDA: Washington, DC, USA, 1981.

- Lotz, C. Investigations of Factors Affecting the Quality of Experiments Under Microgravity in the Einstein Elevator. Ph.D. Dissertation, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz University Hannover, Hannover, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harland, D.M. “Microgravity.” Encyclopedia Britannica. 4 March 2025. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/science/microgravity (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Britannica Editors. “Weightlessness.” Encyclopedia Britannica. 25 October 2023. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/science/weightlessness (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Thornton, W.; Bonato, F. An Introduction to Weightlessness and Its Effects on Humans. In The Human Body and Weightlessness; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NASA Glenn Research Center. A Researcher’s Guide to: Microgravity Materials Research; NASA: Cleveland, OH, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.nasa.gov/science-research/for-researchers/a-researchers-guide-to-microgravity-materials-research/ (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Gowen, R. A Quest for Understanding Weightlessness; Dakota State University Press: Fargo, ND, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Manna, O.M.; Burgio, S.; Picone, D.; Carista, A.; Pitruzzella, A.; Fucarino, A.; Bucchieri, F. Microgravity and Human Body: Unraveling the Potential Role of Heat-Shock Proteins in Spaceflight and Future Space Missions. Biology 2024, 13, 921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Thriving in Space: Ensuring the Future of Biological and Physical Sciences Research: A Decadal Survey for 2023–2032; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglezakis, V.J.; Rapp, D.; Razis, P.; Zorpas, A.A. Chemical Engineering beyond Earth: Astrochemical Engineering in the Space Age. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clément, G. Introduction to Space Biology. In Fundamentals of Space Biology; Clément, G., Slenzka, K., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006; Volume 18, pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipos, G.; Bihari, T.; Milánkovich, D.; Darvas, F. Flow Chemistry in Space-A Unique Opportunity to Perform Extraterrestrial Research. J. Flow. Chem. 2017, 7, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akay, Ö.; Bashkatov, A.; Coy, E.; Eckert, K.; Einarsrud, K.E.; Friedrich, A.; Kimmel, B.; Loos, S.; Mutschke, G.; Röntzsch, L.; et al. Electrolysis in Reduced Gravitational Environments: Current Research Perspectives and Future Applications. npj Microgravity 2022, 8, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawyers, L.; Anderson, C.; Boyd, M.J.; Hessel, V.; Wotring, V.; Williams, P.M.; Toh, L.S. Astropharmacy: Pushing the Boundaries of the Pharmacists’ Role for Sustainable Space Exploration. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2022, 18, 3612–3621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulhamid, F.; Sullivan, B.P.; Terzi, S. Factory in Space: A Review of Material and Manufacturing Technologies. Acta Astronaut. 2025, 229, 90–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pletser, V.; Russomano, T. Research in Microgravity in Physical and Life Sciences: An Introduction to Means and Methods; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancinelli, R.L. The affect of the space environment on the survival of Halorubrum chaoviator and Synechococcus (Nägeli): Data from the Space Experiment OSMO on EXPOSE-R. Int. J. Astrobiol. 2015, 14, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M.; Elwany, A. In-Space Additive Manufacturing: A Review. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. 2023, 145, 020801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]