Abstract

This study aimed to select Metschnikowia pulcherrima strains with antimicrobial potential and high biomass content, optimize their cultivation conditions, evaluate growth characteristics at different scales, and assess antimicrobial activity on apple plants (Malus domestica cv. Golden Delicious) infected with phytopathogens. Of the nine tested strains, M. pulcherrima D2 was selected for its strong inhibitory activity against all tested phytopathogenic molds: Venturia inaequalis, Botrytis cinerea, Phoma exigua, Colletotrichum coccodes, Monilia laxa, Alternaria alternata, Alternaria tenuissima, Fusarium sambucinum, and Fusarium oxysporum, both in vitro on laboratory media (inhibition zones from 13.5 to 35.0 mm) and in vivo on stems, leaves, flowers, and fruits of apple. Morphological observations of treated plants showed the complete absence or significant delays of disease symptoms for up to 10 days. Disease symptoms for several pathogens (V. inaequalis, A. alternata, A. tenuissima, B. cinerea, F. sambucinum) remained reduced by ≥50% for up to 31 days post-treatment compared to the untreated control. Optimal cultivation conditions for M. pulcherrima D2 were established: a complex medium containing yeast extract (5.0 g/L), soy peptone (5.0 g/L), and glucose (2.6 g/L), at pH 5 and 25 °C, with shaking at 180 rpm, resulted in high biomass contents (107–108 CFU/mL). Scale-up in 5 L bioreactors confirmed efficient biomass production (108 CFU/mL and from 3.1 to 3.9 g/L of dry biomass). These findings highlight the strong biotechnological potential of M. pulcherrima D2 for the development of a biocontrol agent to protect apple fruits and trees against fungal phytopathogens.

1. Introduction

There is growing public awareness of the negative effects associated with the extensive use of chemical pesticides in agriculture. Consequently, scientific efforts are increasingly focused on developing environmentally friendly biological methods for protecting plants against phytopathogens [1,2]. Unconventional yeasts of the genus Metschnikowia, due to their unique physiological and metabolic properties, show great potential for use in the production of biocontrol preparations [3,4,5,6,7]. Several species within this genus, including M. pulcherrima, M. andauensis, and M. fructicola, exhibit strong antimicrobial activity against plant phytopathogens, particularly molds, which are responsible for approximately 80% of all plant diseases [1].

Numerous studies have demonstrated the antagonistic activity of Metschnikowia yeasts, which effectively inhibit the growth of phytopathogens under both in vitro and in vivo conditions. In vitro tests have shown that Metschnikowia yeasts inhibit key pathogens such as Penicillium expansum, Botrytis cinerea, Alternaria spp., Fusarium spp., Rhizopus spp. and others [8,9,10]. In vivo research has confirmed their biocontrol potential against B. cinerea and P. expansum on grapes, Penicillium spp. on citrus fruits, and multiple pathogens including Botrytis, Penicillium, and Aspergillus on strawberries, apples, and cherries [11,12,13,14]. Several mechanisms have been identified through which yeasts of the genus Metschnikowia inhibit the growth of plant pathogens. These yeasts naturally inhabit flowers, fruits, and tree sap, where they compete with other microorganisms for ecological niches [4,15]. One of the primary antagonistic mechanisms of Metschnikowia involves iron depletion from the environment through the production of pulcherrimin, a red pigment responsible for iron chelation [16,17]. In addition, Metschnikowia species produce various antimicrobial compounds, including organic acids (e.g., lactic, malic, and cinnamic acids), which lower the environmental pH, creating conditions unfavorable for phytopathogen development [8,9]. These yeasts are also capable of secreting hydrolytic enzymes such as chitinases and glucanases that degrade and damage the cell walls of competing microorganisms [5,15]. Moreover, it has been suggested that Metschnikowia yeasts may modulate the plant immune response, representing an indirect antagonistic mechanism against phytopathogens [5]. This combination of biochemical and ecological strategies makes Metschnikowia a promising genus for use in sustainable plant protection.

The characteristics of yeasts belonging to the genus Metschnikowia offer promising opportunities for their application not only in biocontrol but also in various biotechnological processes, including in the food and cosmetics industries [7]. For example, Metschnikowia yeasts can be utilized in wine production, due to their fermentation potential and broad metabolic profile [15,18]. Co-culturing M. pulcherrima with S. cerevisiae in fruit must has been shown to enhance the aromatic properties of wine by reducing ethyl acetate levels and increasing aroma complexity [15]. Another valuable feature of M. pulcherrima is its ability to synthesize lipids. Yeasts belonging to the genus Metschnikowia typically have fatty acid profiles dominated by oleic acid, which can constitute up to 70% of the total fatty acid content [19]. This makes them promising candidates for research into microbial oil production.

In the United States, M. pulcherrima and M. fructicola species have been granted Generally Recognized As Safe (GRAS) status by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [20]. Within the European Union, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) has conducted and published a peer-reviewed risk assessment regarding the use of the active substance Metschnikowia fructicola NRRL Y-27328 as a pesticide [21]. Commercial preparations containing Metschnikowia yeasts are available for use in the wine industry, for the bioprotection of fruit musts and for pre-fermentation fruit protection (e.g., Metschnikowia pulcherrima yeast, Oenoferm® MProtect, LEVEL2 INITIA™). Although yeasts of the Metschnikowia genus exhibit biocontrol activity, only one commercial crop protection product, marketed as Noli® and Shemer®, contains Metschnikowia fructicola as the active ingredient. This product is mainly applied to vineyards and soft fruit crops (e.g., strawberries, blueberries) to suppress Botrytis spp. According to the manufacturer, it is also effective in reducing brown rot caused by Monilinia spp. in stone fruits such as cherries and plums [22].

Considering the demonstrated biocontrol potential of Metschnikowia yeasts, particularly M. pulcherrima, the development of a plant protection preparation based on these microorganisms represents a promising research direction. However, further studies and optimization of biotechnological processes are required to fully realize this potential. To produce a biopreparation based on Metschnikowia yeasts, it is necessary to first obtain a sufficient amount of viable biomass, as living cells are responsible for inhibiting phytopathogen growth [23]. Other critical steps include understanding the growth kinetics of these microorganisms, selecting the optimal growth substrates and culture conditions, and scaling up the cultivation process. This involves the Metschnikowia yeasts that can utilize a wide range of carbon sources including glucose, sucrose, galactose, maltose, trehalose, ethanol, mannitol, and glycerol. Regarding nitrogen sources, these yeasts preferentially assimilate amino acids from organic compounds over inorganic ammonium salts [4,15]. Key cultivation parameters affecting yeast growth include temperature, pH, and aeration, which must then be optimized and scaled up to achieve high biomass contents [23,24,25,26].

Previous studies have shown that Metschnikowia yeasts exhibit an optimal growth pH range from 5.0 to 7.0 and maintain tolerance across a wider pH spectrum from 3.0 to 9.0 [10,26,27]. Metschnikowia species show optimal biomass production at temperatures from 25 to 30 °C but can tolerate a wide temperature range of 8–40 °C, depending on strain and storage conditions [4,10,28]. Lower cultivation temperatures enhance lipid accumulation in Metschnikowia cells, a phenomenon also observed under nutrient-limited conditions that suppress metabolic activity [19]. Optimal growth of M reukaufii and M. koreensis species has been reported at stirring speeds from 200 to 220 rpm in shake-flask cultures [25,26], while 5 L bioreactor experiments have indicated maximal biomass content at 500 rpm, with excessive agitation (600 rpm) reducing cell density due to shear stress [26,29]. However, there are few studies in the literature that consider these parameters, as well as process scale-up, when optimizing Metschnikowia pulcherrima cultivation conditions.

Given the practical need to develop a M. pulcherrima-based biopreparation for the protection of fruit trees against phytopathogens and the limited literature on the biotechnological aspects of yeast biomass production, the aims of this study were: 1. Select Metschnikowia yeast strains with antimicrobial potential against apple phytopathogens and with high biomass content; 2. Evaluate the effect of various cultivation factors on yeast biomass production (medium composition, carbon and nitrogen sources, pH, temperature, and shaking speed); 3. Assess yeast growth characteristics under optimized conditions at the micro-scale (µL) and in a 5 L bioreactor; 4. Evaluate the antimicrobial activity of the yeast biomass in a study on the stems, leaves, flowers, and fruits of apple trees (Malus Mill., Malus domestica, cv. Golden Delicious) infected with phytopathogens. The eventual goal is to develop a biopreparation for use in agriculture, particularly in organic farming, for the biocontrol of phytopathogens affecting fruit trees, especially apple trees (Malus Mill.), during both cultivation and postharvest fruit storage. This study also makes a novel contribution to the available data on the growth kinetics of the analyzed yeasts, by providing a detailed characterization of their growth and identifying aeration as a key parameter influencing the growth process.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Metschnikowia Pulcherrima Yeasts

Nine strains of Metschnikowia pulcherrima yeast isolated from flowers and fruits were used. Strains D1, D2, J2, J3 and J6 were isolated from apple fruits, strains D3, D4 and M4 from raspberry fruits, and strain TK1 from strawberry flowers. Strains D1, D2, D3, and D4 were identified by sequencing the D1/D2 variable domains of the larger RNA subunit gene (LSU) [10], and the J2, J3, M4, TK1 strain was identified by Maldi-TOF mass spectrometry with a confidence score value in the range of 96.2–99.9% [9]. To select the most suitable Metschnikowia pulcherrima yeast strain for agricultural applications, biomass growth was evaluated on various culture media: YPG agar (Yeast Pepton Glucose agar, BTL, Łódź, Poland), PDA (Potato Dextrose Agar, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), PCA (Plate Count Agar, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), SDA (Sabourauda medium, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), MEA (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), and wort agar (BTL, Łódź, Poland). Yeast strains were incubated on the media for 48 h at temp. 30 °C and the most vigorously growing strains were selected for further evaluation of their antimicrobial activity against phytopathogenic molds.

2.2. Phytopathogenic Molds

The antagonistic activity of five selected Metschnikowia pulcherrima strains (D1, D2, D3, D4, TK1) was evaluated against following nine reference phytopathogenic mold strains: Alternaria tenuissima DSM 63360, Colletotrichum coccodes DSM 62126, Fusarium sambucinum DSM 62397, and Phoma exigua DSM 62040 (German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures DSMZ, Braunschweig, Germany); Alternaria alternata, Fusarium oxysporum Z 154, Botrytis cinerea, and Monilia laxa (Collection of the Plant Breeding and Acclimatization Institute, National Research Institute IHAR-PIB, Radzików, Poland) and Venturia inaequalis (Collection of the National Institute of Horticultural Research, InHort, Skierniewice, Poland).

2.3. Antimicrobial Activity Assay

Antagonistic assays were conducted as in vitro tests using the agar well diffusion method on a laboratory medium with five selected M. pulcherrima strains (D1, D2, D3, D4, TK1) [9]. In parallel, in vivo tests were carried out using M. pulcherrima D2 (a strain selected based on previous in vitro experiments) on stems, leaves, flowers, and fruits of apple (Malus Mill., Malus domestica, cv. Golden Delicious) infected with phytopathogens to evaluate the biocontrol potential of the yeast strain. The in vitro analysis was conducted according to the methodology described by Steglińska et al. [9].

Each individual apple stem and fruit was inoculated with a single phytopathogen in two replicates. Biomass of the phytopathogenic strain was collected and used to infect the stems, leaves, flowers, and fruits. Before testing, the apples were rinsed under tap water. Once dry, the apples were inoculated with phytopathogens using a sterile preparation needle inserted to a depth of 3 mm, with three wounds per fruit. In the case of flowers, stems, and leaves, inoculation involved disrupting the tissue integrity using a preparation needle and applying spores and biomass of the phytopathogens to the wound. One of the two replicates was then treated by spraying with a culture of M. pulcherrima D2 yeast culture. This yeast culture was grown in liquid YPG medium (BTL, Łódź, Poland) under the following conditions: temp. 25 °C, 48 h, shaken at 150 rpm (Heidolph Unimax 1010 shaker). The cell density of the culture was approximately 108 CFU/mL.

For spraying, approximately 10 mL of the culture was applied to stems, leaves, and flowers and about 15 mL to the fruits (each sample received approximately 1–2 individual sprays from the dispenser). Plants and fruits were incubated at room temperature (from 21 to 23 °C) for 20 days. The apples were stored individually in boxes covered with breathable material to ensure better air circulation. The stems with leaves and flowers were placed in flasks containing approximately 20 mL of water. The sprayed samples were kept separately from the samples without spraying but under the same conditions. For stems, disease development was monitored, and observations were recorded once visible symptoms appeared (approximately 10 days post-inoculation). For fruits, macroscopic observations were carried out every 7 or 10 days. The extent of infection was assessed by comparing the treated samples to the control (no yeast applied) using the following scale: 0% —no difference or increased infection; 1–20%—small difference; 21–49%—moderate difference; ≥50%—large difference.

2.4. Evaluation of Cultivation Conditions for Yeast M. pulcherrima

The following parameters of Metschnikowia pulcherrima D2 yeast cultivation were evaluated: temperature, shaking speed, carbon and nitrogen sources in the medium, and medium pH. For carbon source selection, liquid media were prepared with different concentrations and types of saccharides: glucose, sucrose (BTL, Łódź, Poland), at concentrations of 10 g/L, 20 g/L, 40 g/L, 80 g/L, and 160 g/L. Additionally, the medium contained soy peptone (20 g/L) (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), and yeast extract (10 g/L) (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). For nitrogen source selection, liquid media were prepared using glucose (40 g/L) as the carbon source and different nitrogen sources: soy peptone (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), casein hydrolysate (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), and yeast extract (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), at concentrations of 10 g/L, 20 g/L, 40 g/L, 80 g/L, and 160 g/L. After selecting the composition of the medium, the pH was adjusted. For this purpose, 50 mL portions of the medium (glucose 40 g/L, soy peptone 160 g/L) were prepared with predetermined pH values equal to 4, 4.5, 5, 5.5, 6, 6.5, and 7.

The media were prepared in test tubes, each with a total volume of 10 mL. Each medium was inoculated with 0.5 mL of a standardized suspension (2 on the McFarland scale) of M. pulcherrima strain D2 and incubated for 48 h at temp. 25 °C. To determine the optimal incubation temperature and shaking speed, 50 mL of liquid medium with the previously established composition and pH (glucose 40 g/L, soy peptone 160 g/L, pH = 5) was prepared in Erlenmeyer flasks and inoculated with 2.5 mL of a standardized suspension (2 on the McFarland scale) of M. pulcherrima strain D2. The cultures were then incubated for 48 h at temperatures of 15 °C, 20 °C, 25 °C, and 30 °C with shaking speeds of 180 rpm (for optimal temperature selection) and at temp. 25 °C with shaking speeds of 150 rpm, 180 rpm, and 200 rpm (for shaking speed selection).

After incubation, for all experiment variants serial tenfold dilutions of each culture were prepared in physiological saline, and 1 mL from each dilution was pour-plated on solid YPG medium in triplicate. The plates were incubated at a temp. of 25 °C for 48 h. Subsequently, the number of colonies was counted, and the results were expressed as colony-forming units per 1 mL of culture (CFU/mL). Each experiment was performed in three independent replicates.

Based on the selected carbon (glucose) and nitrogen sources (soy peptone and yeast extract), the next step involved optimizing the concentrations of these components. A total of 27 medium variants were prepared (see Supplementary Materials, Table S1), each with a volume of 50 mL. The media were inoculated with 1 mL of standardized suspension of M. pulcherrima D2 yeast (2 on the McFarland scale) and thoroughly mixed. Approximately 150 µL of each medium was transferred into a 96-well microplate in triplicate and placed in a Multiskan GO Microplate Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The cultivation was carried out for 72 h at 25 °C with moderate shaking. Turbidity measurements were taken at hourly intervals (the first measurement at time “0”) at a wavelength of 540 nm. The criteria for selecting the concentrations of individual medium components were two yeast growth parameters: the highest biomass content A540 and the apparent maximum specific biomass growth rate µmax. The A540 value was calculated according to the formula

where:

—maximum absorbance value of the culture/CFU/mL

—minimum absorbance value of the culture/CFU/mL

The calculation of µmax was based on regression analysis involving data points corresponding to the exponential growth phase.

2.5. Bioreactor Processes

Three stirred-tank bioreactors (Biostat B, Sartorius, Gottingen, Germany) were used, each with a total volume of 6.6 L. The cultivation processes using bioreactors were conducted with a working volume of 5.3 L of the liquid medium. The liquid medium (yeast extract 5 g/L, peptone 5 g/L, glucose 2.6 g/L, pH: 5.2) was sterilized in an autoclave at temp. 121 °C. The inoculum (preculture) was prepared at a volume of 300 mL per bioreactor and inoculated with 3 mL of a yeast suspension (2 on the McFarland scale) 48 h prior to the bioreactor process. The preculture was grown in YPG medium (BTL, Łódź, Poland) at 25 °C with shaking at 150 rpm and the final cell concentration was approximately 108 CFU/mL.

The temperature (25 °C) and stirring speed value (300 rpm) were constant. Air flow rates (vvm) were different in each bioreactor and set to 0.5, 0.8, and 1.2 Lair L−1 min−1, respectively. The bioreactor cultures were propagated for 12 h. Antifoam SE-15 emulsion (Merck, Germany) was used to control foaming during the process. During cultivation, the yeast culture samples were collected at 2 h intervals, starting immediately after inoculation. From each sample, pour plating was performed in triplicate on YPG medium and incubated for 48 h at 25 °C. After incubation, the number of CFU/mL was counted for the corresponding time point. The biomass content in each sample was determined by centrifuging 15 mL of culture at 9000 rpm and 25 °C (MPW-380R, MPW, Warsaw, Poland) and then washed twice with 15 mL of distilled water and centrifuged again under the same conditions. The samples were dried in 50 °C for 48 h. Measurements were performed in triplicate and the biomass content [g/L] was determined.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Statistica 13.1 (Statsoft, Tulsa, OK, USA). All measurements of inhibition zones of phytopathogens growth by M. pulcherrima strains and biomass yeast content were performed in triplicate. The results are reported as the mean (M) ± standard deviation (SD). Measurements were compared using a one-way ANOVA with a Duncan’s multiple range test at a significance level of p < 0.05.

3. Results

Metschnikowia pulcherrima strains showed varied growth on microbiological media. Only 5 (D1, D2, D3, D4, TK1) of the 9 strains exhibited abundant biomass growth on all tested media (Supplementary Materials, Table S2), and these strains were selected for further research. This confirms that biotechnological potential depends more on the selected strains than on yeast species.

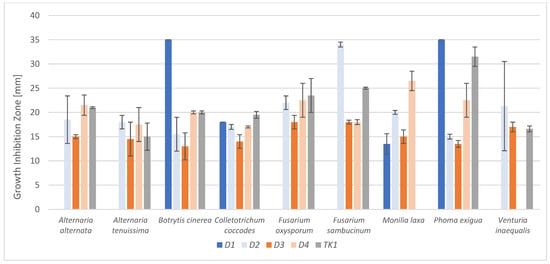

Studies on the inhibition of phytopathogens growth by M. pulcherrima yeast on laboratory media demonstrated varying levels of antimicrobial activity (Table S3, Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Antimicrobial activity of M. pulcherrima strains presented as growth inhibition zones.

Strain D1 was the least active, while the remaining strains inhibited the growth of all tested phytopathogens (except for TK1, which inhibited 8 of the 9 phytopathogenic molds). However, the largest and significantly different inhibition zones of phytopathogens growth were observed for strain D1 against Botrytis cinerea (35 mm), Phoma exigua (35 mm) and Venturia inaequalis (21 mm). All tested M. pulcherrima strains inhibited the growth of Botrytis cinerea, Colletotrichum coccodes, and Phoma exigua. The inhibition zones of phytopathogen growth on laboratory media ranged from 13.5 to 35.0 mm. On the activity assessment scale, most zones were classified as large or high (>15 mm). The strain that most strongly inhibited the growth of all phytopathogens, namely M. pulcherrima D2, was selected for the next stages of research (Table S3). The selection criteria were high biomass production and the ability to inhibit the growth of all tested phytopathogens. Additionally, based on previous studies [8], this strain is known to produce substantial amounts of antimicrobial compounds.

In vivo studies on the inhibition of phytopathogen growth by M. pulcherrima D2 yeast on apple trees (stems, leaves, flowers, fruits) confirmed the antimicrobial effects previously observed under in vitro conditions (Supplementary Materials, Table S4). Ten days after application, M. pulcherrima D2 strain significantly inhibited the development of phytopathogens with the strongest effects observed on apple fruits and leaves. The yeast suppressed the manifestation of morphological symptoms associated with fungal infections caused by Monilia laxa, Fusarium sambucinum, Botrytis cinerea and Venturia inaequalis. For the remaining phytopathogens, a reduction in macroscopic symptoms of pathogen development was observed after 10 days of incubation on plant samples (leaves and fruits) treated with the yeast, compared to the control infected with pathogens (Table S4).

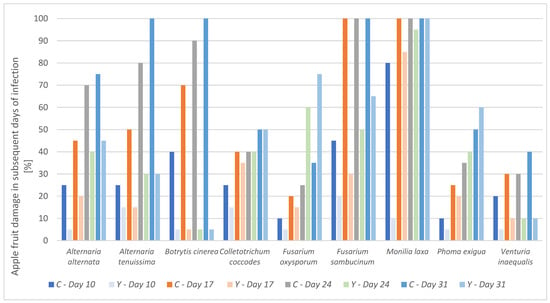

Evaluation of disease incidence on apple fruits in the control group, compared to those treated with M. pulcherrima D2 after 31 days, indicated a pronounced inhibitory effect on phytopathogen development for up to 17 days post-application (Table S5, Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Percentage of apple infection by the phytopathogen on given days. C—control sample infected with phytopathogens, Y—sample infected with phytopathogen and treated with yeast M. pulcherrima D2 culture.

The protective efficacy of the yeast varied depending on the pathogen and the duration of post-treatment. The M. pulcherrima D2 exhibited strong inhibitory activity (≥50%) against the development on apple fruits phytopathogens: Alternaria alternata, Alternaria tenuissima, Botrytis cinerea, Fusarium sambucinum, Venturia inaequalis, with effects persisting up to 31 days after treatment. The most pronounced biocontrol effect was observed against Botrytis cinerea, for which no pathogen development was detected on treated fruits throughout the entire observation period. However, for certain phytopathogens, including Colletotrichum coccodes, Fusarium oxysporum, Monilia laxa, and Phoma exigua, the protective effect of M. pulcherrima D2 was limited to the first 10 days following application. Beyond this period, pathogen development was observed on the fruits (Table S5, Figure 2).

With a view to developing a biopreparation intended for the biological control of phytopathogens in apple trees, optimal cultivation conditions were determined for the M. pulcherrima D2 yeast strain, selected based on preliminary screening (Table 1). The key parameter influencing the biotechnological potential of the strain was biomass growth.

Table 1.

Selection of culture conditions for Metschnikowia pulcherrima D2.

Depending on cultivation conditions, M. pulcherrima D2 achieved growth levels ranging from 2.8 × 105 to 4.8 × 108 CFU/mL, with average values in the range of 107–108 CFU/mL, indicating a high biomass content (Table 1).

The selected cultivation temperature for M. pulcherrima D2 was 25 °C. No statistically significant differences in biomass production were observed at 30 °C, whereas significantly lower contents were recorded at temperatures of 15–20 °C. The strain exhibited a broad pH tolerance, with a pH range of 4.0–6.0, and the highest biomass production was achieved at pH 5.0–5.5. The highest biomass contents were obtained at shaking speeds of 180–200 rpm. At 150 rpm, a statistically significant reduction in biomass levels was observed (Table 1). Various carbon and nitrogen sources were evaluated for their impact on yeast biomass production. Glucose was tested at concentrations of 10–40 g/L, and sucrose was tested at 10–40 g/L as well as at higher concentrations (up to 160 g/L). Nitrogen sources included soybean peptone, yeast extract, and casein hydrolysate, tested across concentrations ranging from 10 to 160 g/L (Table 1). The highest cell counts (3.0 × 108–3.6 × 108 CFU/mL) were obtained with glucose at 20–40 g/L. High cell counts (2.3 × 108–2.8 × 108 CFU/mL) were also observed with sucrose at 10–40 g/L. Biomass production declined at higher sucrose concentrations, although the differences were not statistically significant. Regarding nitrogen sources, both soybean peptone and yeast extract supported comparable biomass contents (7.4 × 106–3.5 × 107 CFU/mL) across the tested concentration range. Statistical analysis showed no significant differences in yeast cell counts on media containing soybean peptone at 80 g/L and 160 g/L. For yeast extract, no significant differences were observed from 10 to 80 g/L; however, above 80 g/L the yeast cell count decreased. In contrast, casein hydrolysate proved to be a less effective nitrogen source for M. pulcherrima D2, yielding significantly lower cell counts (1.4 × 106–8.3 × 106 CFU/mL) (Table 1).

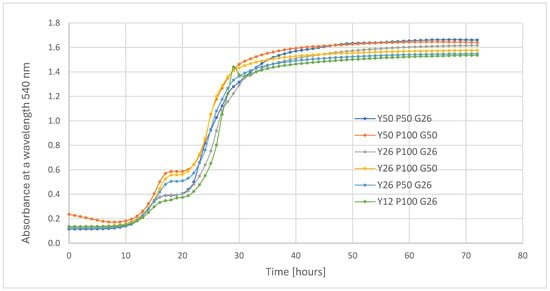

In the next stage of the study, the composition of the culture medium was optimized by testing various concentrations of the selected components: glucose (G), yeast extract (Y), and soybean peptone (P) (see Supplementary Materials, Table S1, Figure S1). Growth curves of Metschnikowia pulcherrima D2 for the six most effective medium variants, selected from the 26 tested, are presented in Figure 3. Growth parameters, including the apparent maximum specific biomass growth rate (µmax) and biomass content, are summarized in Table 2.

Figure 3.

Growth of M. pulcherrima D2 yeast on media with different chemical compositions (Y—yeast extract; P—peptone; G—glucose). The best growth was obtained in medium Y50 P50 G26.

Table 2.

Growth parameters of M. pulcherrima D2 yeast as a function of medium’s chemical composition.

All growth curves of M. pulcherrima D2 cultured in the tested medium variants (Figure S1 and Figure 3) exhibited a similar pattern, indicating biphasic (diauxic) growth. Glucose, a readily metabolizable carbon source, was likely consumed during the initial growth phase (up to approximately 18 h), after which secondary carbon sources originating from yeast extract were utilized by the yeast cells. A brief lag phase was observed between these phases, lasting until approximately 22 h, followed by a renewed exponential growth phase. The stationary phase typically commenced after around 32 h of cultivation (Figure 3).

Among the 27 tested medium variants, six supported the most rapid growth and highest biomass content of M. pulcherrima D2 (Table 2). The fastest growth rates were observed for the medium formulations Y26P100G50, Y50P100G50, and Y50P50G26, with apparent maximum growth rates (µmax) of 0.21–0.23 h−1. The highest biomass content (A540 = 1.547) was obtained with the Y50P50G26 medium (Table 2). This medium composition was selected for further evaluation of yeast growth performance during cultivation scale-up. Scale-up in the optimal medium was carried out in 5 L bioreactors with different aeration rates. Bioreactor cultures exhibited growth rates ranging from 0.19 to 0.31 h−1. The lowest growth rate was observed at vvm values of 0.5 Lair L−1 min−1, (0.19 ± 0.02 h−1), followed by 0.8 Lair L−1 min−1, (0.25 ± 0.01 h−1) and 1.2 Lair L−1 min−1, (0.31 ± 0.02 h−1). Comparing the bioreactor conditions, the highest biomass content was obtained at 1.2 Lair L−1 min−1 (2.6 × 108 CFU/mL; 3.9 ± 0.1 g/L), with lower contents observed at 0.8 Lair L−1 min−1 (2.3 × 108 CFU/mL; 3.7 ± 0.1 g/L) and 0.5 vvm (2.1 × 108 CFU/mL; 3.1 ± 2.3 g/L) (Table 2). However, no statistically significant differences were observed among the biomass content values for the three bioreactor cultivation conditions.

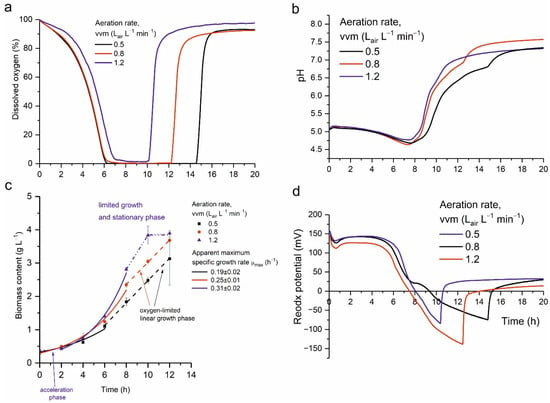

During cultivation of the yeast in a stirred-tank bioreactor, biomass (dry mass g/L), dissolved oxygen, culture pH, and redox potential were measured (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Kinetics of M. pulcherrima D2 cultivation in a bioreactor, showing changes in (a) dissolved oxygen, (b) pH values, (c) biomass content, and (d) redox potential at aeration rates (vvm) of 0.5, 0.8, and 1.2 Lair L−1 min−1.

During cultivation, the stationary phase began between 10 and 14.5 h, depending on the aeration rate (at 10 h for vvm = 0.5 Lair L−1 min−1, 12 h for vvm = 0.8 Lair L−1 min−1, and 14.5 h for vvm = 1.2 Lair L−1 min−1). Aeration rate had a strong effect on the apparent maximum specific biomass growth rates, which were 0.19 ± 0.02 h−1, 0.25 ± 0.01 h−1 and 0.31 ± 0.02 h−1 for their respective aeration levels of 0.5, 0.8 and 1.2 Lair L−1 min−1. Figure 4 clearly shows that oxygen was a limiting factor in the bioreactor cultivation. For the two lowest vvm values (0.5 and 0.8 Lair L−1 min−1) oxygen saturation of the medium was close to zero. For these two runs, exponential growth phase ended earliest and linear growth phase commenced. This phase lasted at least 6 h for vvm = 0.5 Lair L−1 min−1 and 4 h for vvm = 0.8 Lair L−1 min−1. In both cases, this growth-limiting phase exhibited a calculated volumetric biomass growth rate of 0.33 ± 0.01 g L−1 h−1, which is typical behavior for an oxygen-limited system. This limiting phase was much shorter at vvm = 1.2 Lair L−1 min−1 when oxygen saturation did not fall to zero. In this case, consumption of glucose and other dissolved substrates (rather than oxygen limitation) was the main factor causing growth deceleration.

An initial decrease in pH to 4.5 was observed during the first 7.5 h of cultivation (Figure 4), irrespective of the aeration rate, except for the run at vvm = 1.2 Lair L−1 min−1 which deviated slightly from the other two runs. The minimum pH in this run was 0.2 pH units higher than in the other runs. From 9 h onward, pH increased to 7.25 and 7.5 irrespective of the aeration rate. This behavior was associated with the onset of the stationary phase. Redox potential levels also reflected the respiratory activity of the yeasts. The time at which redox potential reached 0 mV coincided with the lowest pH values and near-zero dissolved oxygen. Subsequently, redox potential became negative, then rapidly increased to positive values, coinciding with an abrupt rise in dissolved oxygen in the cultivation broth.

During cultivation, dissolved oxygen content in the yeast culture (Figure 4) dropped sharply during the exponential growth phase because of intense cellular respiration and then rose again as respiratory activity decreased during the stationary phase. The timing of the dissolved oxygen increase depended on the aeration rate, and the onset of the stationary phase was ultimately caused by depletion of dissolved substrate (glucose or other nutrients).

The kinetics of growth, and the changes in pH, redox potential, and dissolved oxygen level in the medium during cultivation, indicated a short but intense exponential growth phase that resulted in a high biomass content of M. pulcherrima D2. Among the three bioreactor runs differing in aeration rate, the most intensive biomass growth occurred at the highest aeration rate (1.2 vvm). In that run, the highest yeast-cell viability was likely achieved between 6 and 8 h —i.e., in the late exponential phase before limitation began.

4. Discussion

Metschnikowia pulcherrima yeast is particularly promising for the biological control of plant pathogens, due to its simple nutritional requirements, rapid growth on inexpensive media, and strong ability to survive on fruit surfaces [30,31]. Antagonistic mechanisms of M. pulcherrimina have been studied in all tested strains and reported in earlier publications [8,10,32]. The mechanisms underlying the antimicrobial activity of Metschnikowia pulcherrima have recently become the focus of proteomic and metabolomic investigations [8,33]. Proteomic analyses have demonstrated that, during interactions between M. pulcherrima and the mold Botrytis cinerea, the principal antagonistic mechanisms involve an increased abundance of proteins associated with gene expression and translation, vesicle trafficking and intracellular transport pathways, long-chain fatty acid biosynthesis, pyruvate metabolism, and mitochondrial function, as well as proteins related to the cell wall and plasma membrane. These findings highlight the role of the cell wall and plasma membrane in the yeast’s antagonistic interactions [33]. Previous metabolomic studies conducted by the authors of the present work confirmed the complex metabolic regulation underlying the antagonistic activity of M. pulcherrima strains D2, D4, and TK1 against phytopathogens. These studies identified numerous metabolomic pathways and chemical compounds involved in the biocontrol response, including indole and its derivatives, lactic acid, pulcherriminic acid, salicylic acid, anisic acid, azelaic acid, syringic acid, cinnamic acid, catechol, and quinoline among others [8]. Future research should incorporate transcriptomic analyses of gene expression associated with plant–pathogen–yeast interactions, which would help elucidate the specific bioprotective mechanisms employed by M. pulcherrima and the defense responses activated in plants following phytopathogen invasion.

Among the nine M. pulcherrima strains tested in this study, which were isolated from flowers and fruits, strain D2 was selected because of its vigorous growth on various laboratory media and strong antifungal activity; it effectively inhibited the growth of all tested phytopathogenic molds. Strains D3, D4, and TK1 also demonstrated notable antimicrobial potential. These observations align with previous reports indicating that epiphytic strains from fruits are generally more effective in biological control than those from culture collections [34]. Consistent with earlier findings, M. pulcherrima strains isolated from apple surfaces have shown high efficacy in managing postharvest fruit diseases [34,35,36]. Their frequent isolation from various apple tissues underscores their adaptability, while strain-specific differences in biocontrol efficiency likely reflect underlying genetic diversity [37,38].

In the present in vitro studies, the yeast strains of Metchnikowia pulcherrima demonstrated potential for inhibiting nine phytopathogens: Colletotrichum coccodes, Alternaria alternata, Alternaria tenuissima, Fusarium sambucinum, Fusarium oxysporum, Monilia laxa, Phoma exigua, Botrytis cinerea, and the previously unstudied apple pathogen Venturia inaequalis. Previous in vitro studies involving Metschnikowia yeasts confirmed their ability to inhibit pathogenic molds including Penicillium expansum, Botrytis cinerea, Alternaria sp., Monilia sp., Aspergillus sp., Fusarium sp., Rhizopus sp., and Verticillium sp. [10,23,36,39].

In vivo studies have confirmed the biocontrol activity of Metschnikowia pulcherrima/andauensis against Botrytis cinerea and Penicillium expansum on grapes [11,40], Penicillium spp. on citrus fruits [12,41,42,43], P. expansum on sweet cherries [13], and multiple pathogens including Botrytis, Penicillium, Rhizopus, and Aspergillus on strawberries, apples, and grapes [33,44], Rhizopus stolonifer, Penicillium expansum and Botrytis cinerea on pears and apples [12]. Previously, yeast activity had not been evaluated against Venturia inaequalis, Monilia laxa, Phoma exigua, or Colletotrichum coccodes. The current in vivo assays on apple plants demonstrated that M. pulcherrima D2 significantly inhibited all tested fungi, particularly the destructive V. inaequalis, for up to 10 days post-treatment, with some suppression lasting up to 31 days. In the case of some phytopathogens (Colletotrichum coccodes, Monilia laxa), only small differences were observed between the control (unsprayed) and the treated samples, especially after 17 days of incubation. It is possible that these pathogens are resistant to the action of M. pulcherrima yeast, and it may be necessary to repeat the spray after 10 days of incubation.

The efficacy of yeast depends not only on strain and pathogen type but also on the apple cultivar. This study used ‘Golden Delicious’, known for its high soluble solids content, which favors growth of Metschnikowia compared with cultivars such as ‘Granny Smith’, ‘Red Chief’, and ‘Royal Gala’ [38]. Further work should assess M. pulcherrima survivability and antimicrobial activity on other cultivars, and should optimize field dosage and application frequency. In this study, suspensions at 108 CFU/mL reduced disease symptoms by ≥75%. Similarly, Manso and Nunes (2011) reported a 20–30% reduction in apple infection rates when yeast concentration increased from 5 × 106 to 1 × 107 CFU/mL [12]. Future studies should include long-term field and postharvest trials to refine treatment parameters. The efficacy of biocontrol is a complex function of both the antagonistic properties of the microorganisms and the traits of the host plant. Key host-related factors include the fruit’s chemical composition, which varies with cultivar and encompasses phenolic compounds, organic acids, and sugar content; the structure of the peel surface and the presence of wounds; plant defense mechanisms involving enzymes and resistance-modulating compounds; the degree of fruit maturity, and the native microbiome [45,46,47,48].

To enhance the antagonistic effect, the potential synergistic interactions between Metschnikowia pulcherrima and other microorganisms should be considered. For example, strains of Lactobacillus that naturally colonize fruit surfaces, which are known for their inhibitory activity against a range of phytopathogens [49]. Additionally, combinations of yeasts with plant extracts, recognized for their inhibitory properties against phytopathogens [50], as well as with edible coatings based on pectin or methylcellulose [51], could be explored. The use of yeast in combination with formulations that stimulate plant growth or enhance resistance to environmental stress may also represent a promising strategy to increase biocontrol efficacy.

Although yeasts of the Metschnikowia genus exhibit biocontrol activity, only one commercial product, marketed as Noli® and Shemer®, utilizes Metschnikowia fructicola for crop protection. It is applied to grapes and soft fruits (e.g., strawberries, blueberries) to control Botrytis spp. and, according to the manufacturer, to reduce Monilinia brown rot in stone fruits such as cherries and plums [22]. There is thus a clear need to develop a Metschnikowia pulcherrima-based biopreparation for protecting apple trees against phytopathogens. Key factors include rapid growth and high biomass content. This study evaluated the biotechnological potential of M. pulcherrima D2 for biocontrol applications, optimizing cultivation parameters such as carbon and nitrogen sources, pH, agitation speed, and temperature. Under optimal laboratory conditions, yeast extract (5.0 g/L), soy peptone (5.0 g/L), glucose (2.6 g/L), pH 5, 25 °C, and 180 rpm, the strain achieved cell counts from 107 to 108 CFU/mL, confirming its strong biotechnological potential.

Optimization of carbon and nitrogen sources for M. pulcherrima D2 cultivation identified three key components: soy peptone (5.0 g/L), yeast extract (5.0 g/L), and glucose (2.6 g/L). The addition of yeast extract at 10–80 g/L, with an optimal concentration of 5.0 g/L, significantly enhanced biomass content. Serving mainly as a nitrogen source (11.4%), yeast extract provides a balanced mixture of peptides, proteins, vitamins, and carbohydrates [52], which, together with glucose, support rapid growth and high cell density. Its buffering capacity [53] may further promote yeast viability. Yeast extract is a key component of YPD medium and is known to stimulate biomass production through its vitamin content [54,55]. Spadaro et al. (2010) reported high biomass content (6.0 g/L and 1.5 × 109 cells/mL) for M. pulcherrima strain BIO126 in media containing ≥30 g/L yeast extract, with D-mannitol and L-sorbose (5 g/L each) [24]. Previous studies have examined diverse nitrogen and carbon sources for various Metschnikowia species, including M. pulcherrima, M. reukaufii, and M. koreensis. Tested nitrogen sources included organic compounds such as nutrient broth, malt and beef extracts, and different peptones like meat peptone, casein peptone, bacto-peptone, and hydrolyzed casein (5–60 g/L), as well as inorganic sources like ammonium sulfate and urea (1–10 g/L). Carbon sources such as glucose, fructose, sorbose, maltose, sucrose, sorbitol, mannitol, and arabitol were evaluated at 10–30 g/L [24,25,26]. Huang et al. (2022) and Singh et al. (2011) focused mainly on M. reukaufii and M. koreensis, targeting metabolite synthesis (e.g., D-arabitol, carbonyl reductase) rather than biomass growth (6–15 g/L) [25,26]. Similarly, Nemcová et al. (2021) used a peptone–glucose medium supplemented with mineral salts and waste substrates (animal fat, glycerol) to stimulate lipid biosynthesis, obtaining 4.3–13.4 g/L of biomass [56]. These results emphasize the critical role of medium composition and research objectives in determining biomass productivity and optimizing Metschnikowia cultures for specific applications [56].

Our study showed that the optimal initial pH for high M. pulcherrima D2 biomass (4 × 108 CFU/mL) is 5.0–5.5, although the species tolerated pH 4.0–6.0. Spadaro et al. (2010) reported optimal pH 5.0–7.5, achieving ~108 CFU/mL, with final pH rising to ~8.0 [24]. Other studies similarly indicated an optimal pH of 5.0–7.0 and noted tolerance from 3.0 to 9.0 [10,26,27].

The present study also determined the optimal cultivation temperature for M. pulcherrima D2. The highest cell counts (from 2.5 × 107 to 3.6 × 107 CFU/mL) were achieved at temperatures from 25 to 30 °C, whereas lower temperatures (from 15 to 20 °C) led to reduced biomass production. Temperature strongly influences yeast growth, enzyme activity, and metabolite synthesis [57]. For Metschnikowia species, optimal biomass productivity generally occurs between 25 °C and 30 °C [25,26,28,58]. Nonetheless, these yeasts exhibit broad thermal tolerance (from 8 to 40 °C), depending on strain adaptation and storage conditions [4,10,27,59]. Notably, Nemcová et al. (2021) found that temperatures ≤ 15 °C slow growth but promote lipid accumulation, potentially enhancing yeast survival [56].

Aeration is a key factor in yeast cultivation, as shaking ensures effective oxygen transfer between the medium and cells, supporting growth and metabolite synthesis [25,60]. In this study, the highest biomass contents of M. pulcherrima D2 were obtained at shaking speeds from 180 to 200 rpm, while a significant reduction occurred at 150 rpm. Similarly, Huang et al. (2022) found optimal growth of M. reukaufii at 220 rpm, and Singh et al. (2011) reported 200 rpm as optimal for M. koreensis in shake-flask cultures [25,26]. In 5 L bioreactor experiments, agitation between 200 and 600 rpm showed the best biomass content at 500 rpm, whereas excessive agitation (600 rpm) reduced cell density due to shear stress [25,26,29].

In the present study, several key observations regarding the M. pulcherrima D2 bioreactor cultivations were made. The apparent maximum specific biomass growth rate recorded at the vvm of 1.2 Lair L−1 min−1 was higher than the values noted at vvm 0.8 and 0.5 Lair L−1 min−1. Furthermore, at the vvm of 1.2 Lair L−1 min−1 the increase of oxygen level back to the value close to 100% took place sooner than at vvm 0.8 and 0.5 Lair L−1 min−1. Hence, the duration of the cultivation process at 1.2 vvm was shorter compared to the remaining two variants. These observations indicate that the higher aeration rate intensified metabolic processes in the yeast cells.

Scale-up of the process in a 5 L bioreactor confirmed high M. pulcherrima D2 biomass content within 12 h of cultivation. A biomass content of 2.6 × 108 CFU/mL and dry biomass of 3.9 g/L was obtained in the fermenter with aeration at 1.2 vvm. When comparing the obtained biomass content with the literature data reported by Spadaro et al. (2010), where the biomass content of M. pulcherrima in a bioreactor ranged from 1.4 to 6.0 g/L of dry biomass depending on the experimental conditions, and the cell number reached 1.6 × 109 CFU/mL, it can be concluded that a lower, yet satisfactory result with industrial potential was obtained [24]. It is worth noting that bioreactor cultivation (during which biomass and CFU/mL measurements were taken) lasted 12 h, whereas in the experiment conducted by Spadaro et al. (2010) the cultivation period was longer (>18 h) [24]. The obtained biomass content is sufficient to conduct further experiments aimed at developing a biopreparation for plant protection. Additionally, the selected medium does not contain a large amount of components (yeast extract 5.0 g/L, soy peptone 5.0 g/L, glucose 2.6 g/L), yet it allows for achieving a viable cell concentration of 108 CFU/mL, which is economically advantageous because biomass production requires fewer raw materials while still yielding satisfactory results.

Growth kinetic data showed a rapid pH decrease due to the secretion of organic acids and CO2, reflecting their strong acidifying effect [61]. After 7.5 h, pH increased as the stationary phase began, with reduced respiration and CO2 production, marking an appropriate time to harvest biomass for further processing. Spadaro et al. (2010) noted that pH control is not critical for biomass content [24]. Dissolved oxygen declined during the exponential phase and rose again in the stationary phase, typical for aerobic cultures [24,62,63]. Cultivation time is also crucial: too short reduces biomass, while too long can cause metabolite toxicity [25]. In our study, the exponential phase of M. pulcherrima D2 lasted up to 8 h in bioreactors, depending on the aeration rate compared to between 18 and 20 h, and 30 h reported in previous studies [26]. This likely reflects strain-specific traits and differences in medium composition and aeration.

Further scale-up should be pursued under industrial conditions, including studies on storage parameters to ensure maximum stability of the yeast in biopreparation prior to application in agricultural biocontrol. In the present study, a cell survival test was not performed, so it is important to include this step in future research. It would also be valuable to investigate protective substances that ensure the activity of yeast cells, as this is a key element in the production of a biopreparation. Conducting experiments on a larger number of fruits under storage conditions or directly in orchards would be advisable. These steps are planned for future work, as they are essential for developing an ecological biopreparation for plant protection.

5. Conclusions

The results of this study confirm the strong biocontrol potential of Metschnikowia pulcherrima, particularly strain D2, which effectively inhibited a broad spectrum of apple pathogens, including, for the first time, Venturia inaequalis. These findings highlight the yeast’s adaptability, strain-dependent efficacy, and suitability for sustainable disease management in apple cultivation. Further optimization of application strategies and field validation could enhance its practical use as an environmentally friendly alternative to chemical fungicides. This study demonstrates that Metschnikowia pulcherrima D2 possesses strong biotechnological potential for large-scale production of biocontrol agents. Optimization of key parameters such as nutrient composition, pH, temperature, and aeration enabled the achievement of high biomass content. These results provide a solid foundation for developing an effective M. pulcherrima-based biopreparation for apple protection, and warrant further research on process scale-up and formulation stability under industrial conditions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app152413236/s1. Table S1. Variants of medium composition; Table S2. Growth intensity of Metschnikowia pulcherrima yeast strains on laboratory media; Table S3. Inhibition of phytopathogen growth by Metschnikowia pulcherrima strains (in vitro studies on the laboratory medium); Table S4. Macroscopic observations of apple leaves, flowers, fruits after 10 days infection with phytopathogens and after spraying with Metschnikowia pulcherrima D2 yeast culture; Table S5. Infection of apple fruit with phytopathogens and the protective effect of M. pulcherrima D2 yeast; Figure S1. Growth of Metschnikowia pulcherrima D2 yeast on media with different chemical compositions (Y-yeast extract, P-peptone, G-glucose).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.G., M.B.; Methodology, Z.P., M.B., T.B., B.G.; Formal analysis, Z.P., T.B., B.G., M.B.; Investigation, Z.P., T.B., A.Ś., M.B.; Resources, Z.P., B.G., M.B.; Data curation, Z.P., B.G.; Writing−original draft preparation, Z.P., B.G., T.B., M.B.; Writing—review and editing, B.G., T.B., M.B.; Visualization, Z.P., B.G.; Supervision, B.G.; Project administration, B.G.; Funding acquisition B.G., M.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article and Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Peng, Y.; Li, S.J.; Yan, J.; Tang, Y.; Cheng, J.P.; Gao, A.J.; Yao, X.; Ruan, J.J.; Xu, B.L. Research Progress on Phytopathogenic Fungi and Their Role as Biocontrol Agents. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 670135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Synan, A.; Khaled, M.; Lam, S.T. Mechanisms and strategies of plant defense against Botrytis cinerea. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2017, 37, 262–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez-San Milan, A.; Gamir, J.; Farran, I.; Larraya, L.; Veramendi, J. Identification of new antifungal metabolites produced by the yeast Metschnikowia pulcherrima involved in the biocontrol of postharvest plant pathogenic fungi. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2022, 192, 111995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachance, M.A. Metschnikowia: Half tetrads, a regicide and the fountain of youth. Yeast 2016, 33, 563–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipiczki, M. Metschnikowia pulcherrima and Related Pulcherrimin-Producing Yeasts: Fuzzy Species Boundaries and Complex Antimicrobial Antagonism. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Tan, Z.; Wang, C.; Liu, W.; Hang, F.; He, X.; Ye, D.; Li, L.; Sun, J. Iron Competition as an Important Mechanism of Pulcherrimin-Producing Metschnikowia sp. Strains for Controlling Postharvest Fungal Decays on Citrus Fruit. Foods 2023, 12, 4249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Rygała, A.; Zhang, B.; Kręgiel, D. Potential of Metschnikowia yeasts in green applications: A review. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1652494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perek, Z.; Krupa, S.; Nizioł, J.; Kręgiel, D.; Ruman, T.; Gutarowska, B. Metabolomic Insights into the Antimicrobial Effects of Metschnikowia Yeast on Phytopathogens. Molecules 2025, 30, 3268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steglinska, A.; Kołtuniak, A.; Berłowska, J.; Czyżowska, A.; Szulc, J.; Cieciura-Włoch, W.; Okrasa, M.; Kręgiel, D.; Gutarowska, B. Metschnikowia pulcherrima as a Biocontrol Agent against Potato (Solanum tuberosum) Pathogens. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlikowska, E.; James, S.A.; Breierova, E.; Antolak, H.; Kregiel, D. Biocontrol capability of local Metschnikowia sp. Isolates. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 2019, 112, 1425–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parafati, L.; Vitale, A.; Restuccia, C.; Cirvilleri, G. Biocontrol ability and action mechanism of food-isolated yeast strains against Botrytis cinerea causing post-harvest bunch rot of table grape. Food Microbiol. 2015, 47, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manso, T.; Nunes, C. Metschnikowia andauensis as a new biocontrol agent of fruit postharvest diseases. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2011, 61, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Paiva, E.; Serradilla, M.J.; Ruiz-Moyano, S.; Cordoba, M.G.; Villalobos, M.C.; Casquete, R.; Hernandez, A. Combined effect of antagonistic yeast and modified atmosphere to control Penicillium expansum infection in sweet cherries cv. Ambrunes. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2017, 241, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biasi, A.; Zhimo, V.Y.; Kumar, A.; Abdelfattah, A.; Salim, S.; Feygenberg, O.; Wisniewski, M.; Droby, S. Changes in the Fungal Community Assembly of Apple Fruit Following Postharvest Application of the Yeast Biocontrol Agent Metschnikowia fructicola. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morata, A.; Loira, I.; Escott, C.; del Fresno, J.M.; Bañuelos, M.A.; Suárez-Lepe, J.A. Applications of Metschnikowia pulcherrima in Wine Biotechnology. Fermentation 2019, 5, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipiczki, M. Metschnikowia Strains Isolated from Botrytized Grapes Antagonize Fungal and Bacterial Growth by Iron Depletion. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 6716–6724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kregiel, D.; Nowacka, M.; Rygala, A.; Vadkertiová, R. Biological Activity of Pulcherrimin from the Meschnikowia pulcherrima Clade. Molecules 2022, 27, 1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kręgiel, D.; Pawlikowska, E.; Antolak, H.; Dziekońska-Kubczak, U.; Pielech-Przybylska, K. Exploring Use of the Metschnikowia pulcherrima Clade to Improve Properties of Fruit Wines. Fermentation 2022, 8, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeln, F.; Chuck, J.C. The role of temperature, pH and nutrition in process development of the unique oleaginous yeast Metschnikowia pulcherrima. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2020, 95, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA. GRN No. 1028: M. pulcherrima DANMET-A and M. fructicola DANMET-B. 2022. Available online: https://www.hfpappexternal.fda.gov/scripts/fdcc/index.cfm?set=GRASNotices&id=1028 (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA); Arena, M.; Auteri, D.; Barmaz, S.; Bellisai, G.; Brancato, A.; Brocca, D.; Bura, L.; Byers, H.; Chiusolo, A.; et al. Peer review of the pesticide risk assessment of the active substance Metschnikowia fructicola NRRL Y-27328. EFSA J. 2017, 15, e05084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariranur, H.; Ban, Y.; Endang, R.; Ho, K.C.; Kang, Y. Unforeseen current and future benefits of uncommon yeast: The Metschnikowia genus. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 108, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spadaro, D.; Vola, R.; Piano, S.; Lodovica Gullino, M. Mechanisms of action and efficacy of four isolates of the yeast Metschnikowia pulcherrima active against postharvest pathogens on apples. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2002, 24, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spadaro, D.; Ciavorella, A.; Zhang, D.; Garibaldi, A.; Gullino, M.L. Effect of culture media and pH on the biomass production and biocontrol efficacy of a Metschnikowia pulcherrima strain to be used as a biofungicide for postharvest disease control. Can. J. Microbiol. 2010, 56, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; An, Y.; Zabed, H.M.; Ravikumar, Y.; Zhao, M.; Yun, J.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Qi, X. Enhanced Biosynthesis of D-Arabitol by Metschnikowia reukaufii Through Optimizing Medium Composition and Fermentation Conditions. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2022, 194, 3119–3135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Chisti, Y.; Banerjee, U.C. Production of carbonyl reductase by Metschnikowia koreensis. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 10679–10685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.M.; Choi, J.E.; Komakech, R.; Park, J.H.; Kim, D.W.; Cho, K.M.; Kang, S.M.; Choi, S.H.; Song, K.C.; Ryu, C.M.; et al. Characterization of a novel yeast species Metschnikowia persimmonesis KCTC 12991BP (KIOM G15050 type strain) isolated from a medicinal plant, Korean persimmon calyx (Diospyros kaki Thumb). AMB Express 2017, 7, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltran, G.; Novo, M.; Guillamon, J.M.; Mas, A.; Rozes, N. Effect of fermentation temperature and culture media on the yeast lipid composition and wine volatile compounds. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2008, 121, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Pérez, J.A.; Rodríguez Porcel, E.M.; Casas López, J.L.; Fernández Sevilla, J.M.; Chisti, Y. Shear rate in stirred tank and bubble column bioreactors. Chem. Eng. J. 2006, 124, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanchaichaovivat, A.; Ruenwongsa, P.; Panijpan, B. Screening and identification of yeast strains from fruits and vegetables: Potential for biological control of postharvest chilli anthracnose (Colletotrichum capsici). Biol. Control 2007, 42, 326–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Qiao, N.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Tian, F.; Zhai, Q.; Chen, W. Postharvest control of Penicillium expansum in fruits: A review. Food Biosci. 2020, 36, 100633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlikowska, E.; Kolesińska, B.; Nowacka, M.; Kręgiel, D. A New Approach to Producing High Yields of Pulcherrimin from Metschnikowia Yeasts. Fermentation 2020, 6, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-San Millan, A.; Larraya, L.; Fernandez-Irigoyen, J.; Farran, I.; Veramendi, J. Metschnikowia pulcherrima as an efficient biocontrol agent of Botrytis cinerea infection in apples: Unraveling protection mechanisms through yeast proteomics. Biol. Control. 2023, 183, 105266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muccilli, S.; Restuccia, C. Bioprotective Role of Yeasts. Microorganisms 2015, 3, 588–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansiewicz, W.J.; Tworkoski, T.J.; Kurtzman, C.P. Biocontrol potential of Metchnikowia pulcherrima strains against blue mold of apple. Phytopathology 2001, 91, 1098–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settier-Ramírez, L.; López-Carballo, G.; Hernández-Muñoz, P.; Fontana, A.; Strub, C.; Schorr-Galindo, S. New Isolated Metschnikowia pulcherrima Strains from Apples for Postharvest Biocontrol of Penicillium expansum and Patulin Accumulation. Toxins 2021, 13, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spadaro, D.; Sabetta, W.; Acquadro, A.; Portis, E.; Garibaldi, A.; Gullino, M.L. Use of AFLP for differentiation of Metschnikowia pulcherrima strains for postharvest disease biological control. Microbiol. Res. 2008, 163, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spadaro, D.; Lorè, A.; Garibaldi, A.; Gullino, M.L. A new strain of Metschnikowia fructicola for postharvest control of Penicillium expansum and patulin accumulation on four cultivars of apple. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2013, 75, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatay-Núñez, J.; Albi-Puig, J.; Garrigós, V.; Orejas-Suárez, M.; Matallana, E.; Aranda, A. Isolation of local strains of the yeast Metschnikowia for biocontrol and lipid production purposes. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 40, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez Assaf, L.A.; Pedrozo, L.P.; Nally, M.C.; Pesce, V.M.; Toro, M.E.; Castellanos de Figueroa, L.I.; Vazquez, F. Use of yeasts from different environments for the control of Penicillium expansum on table grapes at storage temperature. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2020, 320, 108520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parafati, L.; Vitale, A.; Restuccia, C.; Cirvilleri, G. Performance evaluation of volatile organic compounds by antagonistic yeasts immobilized on hydrogel spheres against gray, green and blue postharvest decays. Food Microbiol. 2017, 63, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oztekin, S.; Karbancioglu-Guler, F. Bioprospection of Metschnikowia sp. isolates as biocontrol agents against postharvest fungal decays on lemons with their potential modes of action. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2021, 181, 111634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oztekin, S.; Karbancioglu-Guler, F. Biological control of green mould on mandarin fruit through the combined use of antagonistic yeasts. Biol. Control. 2023, 180, 105186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisniewski, M.; Wilson, C.; Droby, S.; Chalutz, E.; El-Ghauth, A.; Stevens, C. Postharvest Biocontrol: New Concepts and Applications. In Biological Control: A Global Perspective, Red; Vincent, C., Goettel, M.S., Lazarovitz, G., Eds.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2007; pp. 262–273. [Google Scholar]

- Mercier, J.; Wilson, C.L. Colonization of Apple Wounds by Naturally Occurring Microflora and Introduced Candida oleophila and Their Effect on Infection by Botrytis cinerea during Storage. Biol. Control. 1994, 4, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jijakli, M.H.; Lepoivre, P.; Grevesse, C. Yeast Species for Biocontrol of Apple Postharvest Diseases: An Encouraging Case of Study for Practical Use. In Biotechnological Approaches in Biocontrol Plant Pathogenes; Mukerji, K.G., Chamola, B.P., Upadhyay, R.K., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1999; Chapter 2; pp. 31–49. [Google Scholar]

- Spadaro, D.; Droby, S. Development of biocontrol products for postharvest diseases of fruit: The importance of elucidating the mechanisms of action of yeast antagonists. Trends in Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 47, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fariñas-Mera, R.; Silva-Bea, S.; Prado-Acebo, I.; Balboa, S.; Lu-Chau, T.A.; Otero, A.; Eibes, G. The potential of apple pomace extract as a natural antimicrobial agent. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 236, 121891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steglińska, A.; Bekhter, A.; Wawrzyniak, P.; Kunicka-Styczyńska, A.; Jastrząbek, K.; Fidler, M.; Śmigielski, K.; Gutarowska, B. Antimicrobial Activities of Plant Extracts against Solanum tuberosum L. Phytopathogens. Molecules 2022, 27, 1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steglińska, A.; Kołtuniak, A.; Motyl, I.; Berłowska, J.; Cieciura-Włoch, W.; Okrasa, M.; Kręgiel, D.; Czyżowska, A.; Gutarowska, B. Lactic Acid Bacteria as Biocontrol Agents against Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) Pathogens. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 7763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settier-Ramírez, L.; López-Carballo, G.; Hernández-Muñoz, P.; Fontana-Tachon, A.; Strub, C.; Schorr-Galindo, S. Apple-based coatings incorporated with wild apple isolated yeast to reduce Penicillium expansum postharvest decay of apples. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2022, 185, 111805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, F.; Riba, J.P.; Strehaiano, P. Effect of yeast extract concentration on growth of Schizoccharomyces pombe. Biotechnol. Lett. 1992, 14, 123–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudreau, H.; Champagne, C.P.; Goulet, J.; Conway, J. Lactic fermentation of media containing high concentrations of yeast extract. J. Food Sci. 1997, 62, 1072–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goretti, M.; Ponzoni, C.; Caselli, E.; Marchegiani, E.; Cramarossa, M.R.; Turchetti, B.; Forti, L.; Buzzini, P. Bioreduction of α,β-unsaturated ketones and aldehydes by non-conventional yeast (NCY) whole-cells. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 3993–3998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurbanoglu, E.B.; Zilbeyaz, K.; Ozdal, M.; Taskin, M.; Kurbanoglu, N.I. Asymmetric reduction of substituted acetophenones using once immobilized Rhodotorula glutinis cells. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 3825–3829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemcová, A.; Szotkowski, M.; Samek, O.; Cagánová, L.; Sipiczki, M.; Márová, I. Use of Waste Substrates for the Lipid Production by Yeasts of the Genus Metschnikowia-Screening Study. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liszkowska, W.; Berlowska, J. Yeast fermentation at low temperatures: Adaptation to changing environmental conditions and formation of volatile compounds. Molecules 2021, 26, 1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyoda, T.; Ohtaguchi, K. Effect of temperature on d-arabitol production from lactose by Kluyveromyces lactis. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 38, 1179–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wisniewski, M.; Droby, S.; Tian, S.; Hershkovitz, V.; Tworkoski, T. Effect of heat shock treatment on stress tolerance and biocontrol efficacy of Metschnikowia fructicola. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2011, 76, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumdam, H.; Murthy, S.N.; Gummadi, S.N. Production of ethanol and arabitol by Debaryomyces nepalensis: Influence of process parameters. AMB Express 2013, 3, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, G.M. Yeast Physiology and Biotechnology; John Wiley and Sons: Chichester, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Abadias, M.; Teixido, N.; Usall, J.; Vinas, I. Optimization of growth conditions of the postharvest biocontrol agent Candida sake CPA-1 in a lab-scale fermenter. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2003, 95, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meesters, P.A.E.P.; Huijberts, G.N.M.; Eggink, G. Highcell density cultivation of the lipid accumulating yeast Cryptococcus curvatus using glycerol as carbon source. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1996, 45, 575–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).