Abstract

Dendritic cell (DC) immunotherapy is a promising approach for treating cancers such as melanoma and prostate cancer. Although DC-based vaccines can elicit potent anti-tumor immune responses, dosing schedules in both preclinical and clinical settings are often chosen empirically rather than through quantitative optimization. In this work, we develop an enhanced mathematical model of tumor-immune dynamics that incorporates a more realistic tumor growth law and an estimated immune-response delay, enabling the systematic design of DC vaccination protocols. Tumor-growth and immunotherapy parameters were calibrated using experimental melanoma data and two metaheuristic optimization methods: Genetic Algorithm and Particle Swarm Optimization. Using the calibrated model, we derived vaccination schedules consisting of three injections totaling DCs. Despite using the same total dose as the baseline four-injection protocol, the optimized schedules reduced tumor burden by approximately over a 5000-h window, as measured by the area under the tumor-time curve, while also lowering the number of administrations. These results demonstrate that effective tumor control can be achieved without increasing treatment intensity and with substantially fewer vaccinations than previously assumed. Prior optimization studies often required cumulative doses exceeding cells to obtain comparable therapeutic effects. In contrast, our findings show that metaheuristic algorithms can produce dose-efficient and biologically grounded schedules that significantly enhance treatment performance. This work highlights the value of computational optimization as a decision-support tool for designing efficient and clinically meaningful DC immunotherapy protocols.

1. Introduction

Dendritic cell (DC) immunotherapy represents a promising approach in cancer and infectious disease treatment, harnessing the capacity of DCs to initiate and regulate adaptive immune responses. As professional antigen-presenting cells, DCs can be isolated from patients, loaded ex vivo with tumor-associated antigens, and subsequently re-infused to stimulate a robust antigen-specific T cell response. This strategy aims to overcome the immune evasion mechanisms of malignant or chronically infected cells by enhancing the recognition and destruction of diseased targets. Over the past two decades, advances in cell culture techniques, antigen-loading strategies, and adjuvant use have refined DC-based vaccines, leading to encouraging preclinical results and several clinical trials [1,2,3]. Despite such progress, the therapeutic efficacy of DC immunotherapy remains highly variable across studies, reflecting persistent uncertainty in several key aspects of treatment design. A major unresolved challenge is the insufficient optimization of dosing schedules. Clinical protocols vary widely in dose, injection timing, and total number of administrations; rigorous and quantitative schedule optimization has rarely been achieved. Reviews of DC vaccine trials emphasize the heterogeneity of administered doses and timing, underscoring the lack of evidence-based guidelines for constructing effective dosing regimens [4,5,6]. Experimental and clinical findings further demonstrate that variations in dose and inter-dose intervals can significantly alter therapeutic success [7,8,9,10]. Thus, determining optimal temporal dosing strategies remains an outstanding open problem.

Dendritic cell immunotherapy protocols can be determined by leveraging mathematical models that efficiently describe the dynamics of the immune system’s interaction with tumor growth, predicting the increase or decrease in the number of tumor cells. These models are usually formulated as systems of Ordinary Differential Equations (ODE) to capture the complex, time-dependent interactions among tumor cells, immune cell populations (including CD4+ and CD8+ T-lymphocytes), dendritic cells, and regulatory cytokines [11]. However, an important difficulty concerns the use of oversimplified or unrealistic tumor growth models. Classical formulations such as logistic or Gompertz models often fail to capture experimentally observed tumor dynamics. Recent comparative studies highlight substantial discrepancies between standard growth laws and empirical tumor growth curves, calling for more flexible and realistic modeling approaches [12,13]. Improved tumor growth representations are therefore essential for generating reliable predictions of treatment outcomes.

Another important limitation arises from the restricted applicability of classical optimal control techniques in cancer immunotherapy. Foundational optimal control methods rely on smooth system dynamics and differentiable cost functionals [14,15]. However, the highly nonlinear and parameter-uncertain nature of tumor–immune ODE models often violates these assumptions, resulting in convergence to poor local minima, or inability to incorporate discrete clinical interventions. Recent analyses emphasize that classical optimal control can become computationally intractable or unreliable when faced with biological delays, discontinuities, or uncertain parameters typical of immunotherapy models [16]. These challenges motivate the development of alternative optimization strategies that are robust to model complexity and uncertainty.

One early attempt to determine optimal protocols for dendritic cell immunotherapy was presented in [17], where the optimal control problem was solved using the steepest descent gradient method applied to the cost function. Building on this idea, [18] explored several variants of the gradient descent algorithm (momentum, Nesterov, Adagrad, RMSprop, Adam, and Adam-Bias). However, given that cancer models involve highly nonlinear ODE dynamics, the resulting optimal control problem is generally nonconvex. As a result, traditional approaches face several difficulties, such as convergence to local rather than global minima, slow convergence rates, numerical oscillations, and stagnation in flat regions of the cost landscape. These limitations restrict the applicability of classical optimal control methods, such as Pontryagin’s Minimum Principle or calculus of variation, to realistic cancer immunotherapy optimal scheduling problems [19].

Metaheuristic algorithms offer a powerful complement to classical approaches by providing optimization tools capable of handling nonconvex landscapes and discrete, delayed, or discontinuous dynamics [20]. Their suitability for complex therapeutic scheduling problems has been demonstrated in recent cancer optimization studies [21,22].

In this work, we address the open challenges through a comprehensive mathematical and computational study of DC immunotherapy for melanoma. Building on the tumor–immune interaction model introduced in [8], we incorporate a more realistic tumor growth law supported by empirical studies. A central improvement over previous studies is the treatment of the immune-response delay parameter . Whereas in [8] this latency is fixed at a constant value (232 h) and applied post hoc to the dosing schedule, in this work, is considered as an intrinsic system parameter. In the proposed framework, is estimated directly from data and optimized jointly with other system parameters through metaheuristic algorithms. This shift from a predetermined constant to a data-informed parameter allows the model to capture the biologically relevant delay required for effective T-cell expansion and infiltration in the tumor microenvironment.

To estimate model parameters, identify the biological delay, and optimize injection timing and dosage within a unified framework, two population-based metaheuristic algorithms are employed: Genetic Algorithm (GA) and Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO). GA, inspired by evolutionary principles, iteratively improves a population of candidate solutions through selection, crossover, and mutation, and has shown strong performance in multi-objective cancer therapy scheduling [21]. PSO, based on swarm intelligence, updates particle trajectories using both individual and collective experience, achieving rapid convergence in high-dimensional ODE parameter spaces [22]. Both methods are applied across three stages of the study:

- I.

- Tumor growth calibration. Sensitive tumor-growth parameters are estimated to fit experimental tumor growth data. Immunotherapy is not included in this stage.

- II.

- Immunotherapy calibration. Using the tumor-growth parameters from Stage I, we estimate sensitive parameters related to the immunotherapy response, matching model outputs to experimental immunotherapy data.

- III.

- Protocol optimization. Starting from an initial protocol with fixed injection times and dosages, we optimize treatment schedules to minimize the tumor cell population.

The main contributions of this manuscript are:

- A revised tumor–immune model that incorporates a more realistic tumor growth function validated against experimental data, overcoming limitations of traditional growth laws.

- Data-driven identification of model key parameters, including the immune-response delay, using metaheuristics.

- Optimization of DC vaccination schedules (dose and timing) using GA and PSO. This leads to efficient therapeutic protocols, requiring fewer doses while preserving therapeutic control.

By explicitly addressing the unresolved issues in dosing schedule design, growth-model realism, and limitations of classical optimal control, this study provides a robust computational framework to guide the rational optimization of dendritic cell immunotherapy.

This rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents a mathematical model describing the interaction between the immune system and tumor growth. Based on this model, an adaptation of the tumor growth law is proposed, using a generic growth formulation that more accurately approximates the observed tumor growth dynamics. Section 3 formulates the optimal control problem, where the therapeutic protocol is represented by fixed-dose injections administered at selected time points. The goal is to identify the injection times that minimize the area under the tumor-cell population curve. This optimization problem is addressed using the GA and PSO metaheuristic methods, for which a brief overview of their fundamental principles is also provided. Section 4 presents the identification of tumor growth parameters, the estimation of parameters associated with dendritic cell immunotherapy, and the determination of optimal administration protocols, all obtained using the aforementioned metaheuristic techniques. Section 5 discusses the results and highlights the contributions of this work in comparison with previous studies. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper with the main findings and perspectives for future research.

2. Mathematical Model

A mathematical model describing the interaction of the immune system with tumor growth considering the dynamics of dendritic cell immunotherapy is presented in [8]. The model describes the dynamics of the following key elements of the tumor-immune interaction:

- Cancer or tumor cells, represented by T.

- CD4 helper T-lymphocytes, denoted by H.

- CD8 cytotoxic T-lymphocytes, represented by C.

- Mature dendritic cells loaded with tumor-associated antigen, denoted by D.

- Interleukin IL-2, represented by I.

- Transforming growth factor , which is an inhibitor of T-lymphocytes.

- Interferon gamma , which regulates the major histocompatibility complex of class I.

- The number of receptors of the Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) class I, denoted by , involved in the process of antigen presentation. The MHC class I molecules are housed in the dendritic cell. Their primary function is to present protein fragments produced inside dendritic cells to T-lymphocytes, so the adaptive immune system attacks cells that present protein fragments foreign to the organism.

The model proposed in [8] is defined by:

The first right-hand side term of Equation (1) represents the Gompertz growth law. The second term represents the elimination of tumor cells by CD8 T-cells considering the transforming growth factor and the efficiency of MHC class I receptors.

In (2), the second right-hand side term represents the activation of CD4 T-cells by dendritic cells considering the Verhulst growth law while the third one represents the natural decrease of CD4 T-cells.

In (3), the second right-hand side term represents CD8 T-cell activation due to IL-2 interleukin considering Verhults growth law while the third one represents the natural decrease of CD8 T-cells.

In (4), the first right-hand side term represents the elimination of dendritic cells by CD8 T-cells, while the third one, represents the control input, corresponding to the external administration of dendritic cell immunotherapy treatment.

In (5), the first right-hand side term represents interleukin IL-2 that CD8 T-cells consume, the second one represents interleukin produced by the interaction between dendritic cells and CD4 T-cells, and the third right-hand side term represents the natural decrease of Interleukin IL-2.

In (6), the the first right-hand side term represents the secretion of transforming growth factor that is proportional to the number of tumor cells while the second one indicates the natural degradation of transforming growth factor.

In (7), the first right-hand side term represents the production of interferon gamma, proportional to CD8 T-cells while the second one represents the natural degradation of interferon gamma.

Finally, the first right-hand side term of Equation (8) represents the activation of the number of receptors stimulated by interferon-gamma following Michaelis-Menten kinetics while the third one represents a natural decrease in the activation of the number of receptors.

Based on the above model, in this paper, we propose to replace the first term of Equation (1), which corresponds to the Gompertz growth law describing the tumor cells growth:

with the generic growth law described in [23]:

where , , and .

As derived in [23], the inflection points for Logistic and Gompertz growth laws are mathematically fixed at 50 % and 36.8 % of the carrying capacity (the maximum tumor cell population that the host mouse tissue can sustain given limitations in nutrients, space, and vascular support), respectively. The use of the generic growth law allows for a variable inflection point, providing the necessary flexibility to capture the specific asymmetric growth dynamics of the B16 melanoma, which rigid models fail to approximate accurately. The key advantage of using generic growth law is that it provides a more accurate representation of tumor growth dynamics. It describes a sigmoidal growth curve in which the initial growth rate is rapid, gradually decreasing as the tumor population approaches its carrying capacity and eventually saturates.

Compared to the Gompertz growth law, the generic growth law offers greater structural flexibility, enabling a better fit to experimental data by dynamically adjusting the timescales of both the inflection point and the saturation phase. Specifically, the generic growth law (9) encompasses a broad family of growth laws as special cases via variation of its shape parameters , , and . It reduces to the Richards growth law when , the classical logistic growth law when , the Von Bertalanffy growth law when , and the exponential growth law when . This parametric generalization enables the representation of a wide spectrum of growth behaviors observed in biological systems, thereby capturing empirical tumor kinetics more accurately than standard fixed-form models.

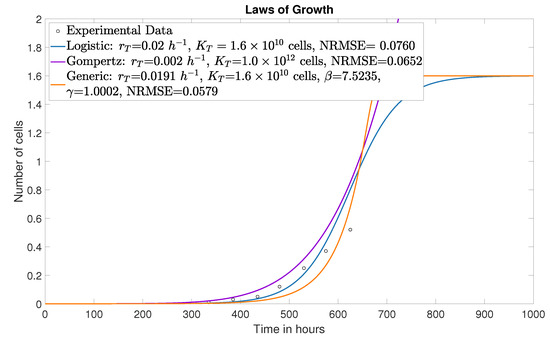

Figure 1 presents the fit of three tumor growth law curves to the experimental data described in Section 4.1 for the mice control group. In [8], the Gompertz model was used with = cells. This value is biologically unrealistic, as it corresponds to a tumor load approximately 62.5 times the maximum capacity a mouse can sustain before death [7]. As a result, the fitted parameter is also not physiologically meaningful. For comparison, Figure 1 also displays the fitted logistic and generalized growth models, with their trajectories determined by the employed specific parameterizations. To quantitatively assess model performance against the experimental data, we report the Normalized Root Mean Square Error (NRMSE) for each fit, which is directly indicated in the legend of each plot. NRMSE quantifies the average deviation between model predictions and observations relative to the data scale and is often expressed as a fraction or percentage. Lower NRMSE values indicate greater agreement between the model and the experimental data.

Figure 1.

Generic, logistic and Gompertz growth law curves.

The model adapted from [8] is described by:

The time-delay parameter denotes the elapsed biological time between vaccine administration and the onset of an effective adaptive anti-tumor response, rather than a mere temporal shift in the control input as done in [8]. In murine models, DCs reach the draining lymph nodes 1–3 days after injection [24], initiating the presentation of antigens and the priming of T cells. Antigen-specific CD8 T-cell expansion subsequently peaks between days 7 and 14 [25], establishing maximal cytotoxic capacity. The delay parameter , therefore represents the cumulative time required for this cascade, from vaccination through to dendritic cell trafficking, T-cell activation, clonal expansion and infiltration into tumor tissue, before immune-mediated tumor growth modulation becomes measurable.

3. Optimal Control Problem

As explained above, immunotherapy treatment can be modeled through the differential equation system defined in (10)–(17), which can be represented as , where

is the state vector and u represents the administration of therapy.

Consider an injection scheme s given by:

such that , where is the fixed initial time and is the fixed time horizon.

The considered therapeutic protocol consists of n injections, each with a dose of size V administered at the instants indicated in s.

Let E be the space of immunotherapy schemes, then for a particular scheme , the control variable takes the form:

Consider a cost function of the form

where L is the running cost. The optimal control problem, which is of Lagrange type, consists of determining a protocol of n injections that minimize the area under the curve of tumor cells, T, that is,

where U represents the class of admissible controls.

This is a complex problem due to nonlinear, non-convex, and time-dependent tumor-immune interactions. Classical optimal control methods, like Pontryagin’s Principle, struggle with discrete injection schedules and delayed immune responses, often requiring differentiability and getting trapped in local optima. Metaheuristic algorithms constitute an alternative for solving this problem by efficiently handling continuous and discrete variables, offering greater flexibility and robustness than traditional methods.

3.1. Metaheuristics: Basic Concepts

Metaheuristics are high-level computational strategies designed to efficiently explore complex and multidimensional solution spaces, particularly in problems where exact methods are unfeasible. Inspired by natural phenomena, from biological evolution to swarm behavior, these algorithms seek to approximate optimal solutions by balancing exploration (broad search of the solution space) and exploitation (local refinement of promising solutions) [26]. Their flexibility makes them ideal tools for the complex problem under consideration. To address the problem presented in this paper, we take advantage of GA and PSO.

3.1.1. Genetic Algorithm

The GA is a population-based metaheuristic inspired by biological evolution. It seeks to solve a task by selecting the best-performing individual (single solution) from the population (ensemble of solutions) [19]. The GA technique starts by creating a random initial population of n solutions and then creates the next generations or new populations by performing the following steps.

- Evaluate the cost function for each member (individual) of the current population and assign a cost value to each.

- Some of the best individuals from the current generation are passed on to the next generation (called an elitist selection strategy). The elitist strategy ensures that the quality of solutions does not decrease during the sequence of new generations.

- Select individuals called parents to produce new individuals called offspring; individuals with better cost values are more likely to be parents in each selection process. Individuals are chosen based on sampling with replacement, so that an individual can be chosen several times.

- Combine the entries of a pair of parents selected using crossover rules to produce two new offspring, which are passed on to the next generation.

- Change some entries of a single selected parent using mutation rules to create new offspring called mutants.

- The algorithm stops when a stopping criterion is met.

The process runs iteratively up to a maximum number of generations or until the performance of the new generation is no longer significantly superior to that of the previous generation. When this stopping criterion is met, the best-performing individual of the last generation is the near-optimal solution.

3.1.2. Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm

The PSO algorithm is also a population-based metaheuristic, it relies on the collective behavior of individuals working together to improve their individual and collective performance. PSO is particularly effective for high-dimensional optimization problems with complex or non-differentiable cost functions, such as those commonly encountered in real-world engineering and biological systems [20].

In PSO, a population (swarm) of particles explores the search space, where each particle represents a candidate solution. Each particle has a position and a velocity. The position represents a candidate solution in the search space; it is a vector encoding the values of the decision variables. The velocity determines the direction and magnitude of the movements of the particles during the search process [20].

The main steps of PSO are:

- Initialization. It covers the following aspects:

- Create a random population of particles and set initial velocities within specified limits.

- Evaluate the cost function for each individual in the created population.

- Establish the best personal position (best solution found by a particle so far) as its initial position and the best global position (best solution found by any particle in the population so far).

- Speed update. At each iteration of the algorithm, the speed of each particle is updated based on three components:

- Inertia. Maintains the current direction of the particle.

- Cognitive component. Attracts the particle towards .

- Social component. Attracts the particle towards .

- Position update. The position of each particle is updated by adding its new velocity to its current position.

- Evaluation and update of and . The cost function is evaluated for the new position of each particle. If the new position is better than its , is updated. If the new position is better than , is updated.

- Iteration. The process is repeated until a termination criterion, such as a maximum number of iterations or convergence to a satisfactory solution, is met.

- Termination. The best global position that PSO finds is the near-optimal solution.

4. Optimization with Metaheuristics

The results presented in this section cover the following aspects:

- Identification of parameters related to tumor growth.

- Identification of parameters related to DC immunotheraphy.

- Determination of optimal protocols for the administration of DC immunotherapy.

4.1. Experimental Background

Before presenting the results, it is important to provide the details about the experimental data related to dendritic cell immunotherapy.

In [27], an immunotherapy was implemented using bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) from C57BL/6 mice, which were incubated in vitro with the MG-CSF protein [28] to differentiate dendritic cells and with the antigen MAGE-AX [29] to stimulate the immune response. Melanoma formation was induced using cancer cells from the B16/F10 line [30], which were inoculated subcutaneously in 10 mice from the C57BL/6 line.

Dendritic cell therapy began one week after tumor induction; dendritic cells were inoculated subcutaneously in each mouse once a week for 3 weeks. In the same way, another 10 mice of the C57BL/6 line were used, in which the formation of melanomas was induced with cells of the B16/F10 line. However, they did not receive treatment with dendritic cells, which allowed data on tumor growth without immunotherapy (control group).

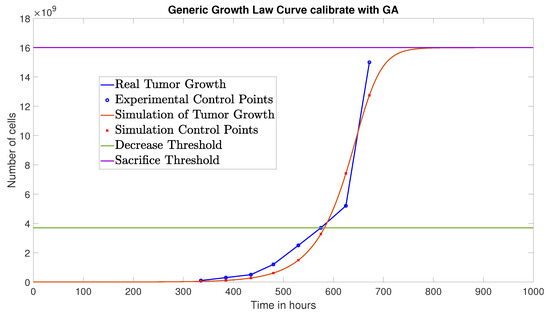

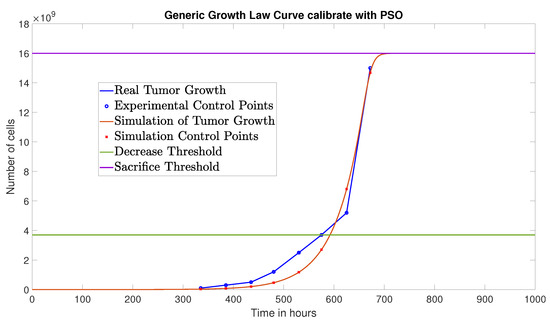

Tumor growth was measured with and without immunotherapy using a vernier caliper beginning the seventh day after tumor cells were injected. Then, it was measured every two days from the tenth day until the mice died or at week 5 when they were sacrificed. Figure 2, shows in blue, the average tumor growth without immunotherapy in the control group mice reported in [8]. The biological results show that mice die when the tumor reaches a diameter of 4.3 cm (approximately 1.6 tumor cells) [7]. For this reason, this number of tumor cells was considered as the tumor carrying capacity , this value is displayed as a horizontal purple line in the figures of this section.

A tumor is considered in remission or decreasing if it does not overlap cells [18], this value is displayed as a horizontal green line in the following figures.

It is important to point out that [8] determined that the most sensitive parameters for the model defined by Equations (1)–(8) are , , and . In this sense, we propose the use of GA and PSO metaheuristics to identify numerical values for these parameters that allow a better fit to the curve defined by the experimental data. Besides, since the tumor growth dynamics was modified from (1), by considering a generic growth law in (10), the numerical values of the parameters and must be also identified using the average growth curve of the mice control group. The parameters identification is divided in two stages. The first one does not consider immunotherapy, the parameters , and , related to the tumor growth, are identified. The second stage takes into account the dendritic cell immunotherapy, the parameters , and , related to the treatment, are identified.

Once the numerical values of the parameters , , , , , and are identified, the GA and PSO metaheuristics are implemented to generate a vector of infusion times for optimal therapy, taking as reference a vector of infusion times for an initial or random therapy, thus solving the optimization problem for immunotherapy scheduling.

4.2. Identification of Parameters Without Immunotherapy

In this stage, the parameters identification aims at accurately reproduce the behavior of tumor growth in the absence of immunotherapy. As previously discussed, the generic growth law (9) was chosen to model tumor cell proliferation. The constants and in this model must be calibrated to fit the experimental growth curve, while can be derived from these parameters. Therefore, the parameters selected for identification are , , and the tumor growth rate , which has been shown to exhibit high sensitivity in tumor growth dynamics, as reported in [8].

Initial values for and were taken from [23], i.e., and . The initial value for the tumor growth rate was set to , as considered in [8]. The initial condition was defined as cancer cells. Additionally, the tumor carrying capacity was set to cancer cells, which represents a more realistic scenario compared to value of considered in [8].

Initially, the simulated tumor growth curve diverges significantly from the experimental data, yielding a NRMSE of 0.3925. This discrepancy is expected, as parameter identification has not yet been performed.

The GA and PSO metaheuristics were implemented in MATLAB R2024b, using Simulink, as well as Parallel Computing and Global Optimization Toolboxes [31]. The objective is to minimize the NRMSE between the experimental average tumor growth curve and the interpolated simulation results from the generic growth law.

For the GA, the search space was defined as follows: , , and . The algorithm was configured with a population of 80 individuals. The initial population was generated uniformly within the defined bounds. Parent selection was performed using a tournament-based strategy, and a Laplace-type crossover operator was applied. In each generation, half of the new individuals (excluding elite offspring) were produced through crossover. The algorithm stops after a maximum of 250 generations or when no improvement in the average trend of the cost function was observed over the last five generations.

The GA converged at the 31st generation, yielding the following identified parameters: , , and , with an NRMSE of 0.0807. Figure 2 compares the resulting tumor growth simulation (red curve) with the experimental data from [8]. Note that the tumor growth saturates at the carrying capacity .

The PSO algorithm was also configured with 80 particles and utilized the same search space and initial conditions as the GA. The initial positions were generated uniformly. The maximum number of iterations was set to 60, with early stopping triggered by a lack of improvement in the average cost function over five iterations.

The PSO algorithm converged after 11 iterations yielding the following parameter values: , , and , achieving a NRMSE of 0.0579. Figure 3 shows the comparison between the experimental data and the simulation based on the parameters obtained via PSO.

Figure 2.

Simulated tumor cell growth (without immunotherapy) using GA-identified parameters, compared to experimental data.

Figure 3.

Simulated tumor cell growth (without immunotherapy) using PSO-identified parameters, compared to experimental data.

Notably, the PSO algorithm achieved a lower NRMSE than the GA, indicating a better fit to the experimental data. Therefore, the parameters identified using PSO will be used in the next stage of the parameter identification process.

4.3. Identification of Parameters with Immunotherapy

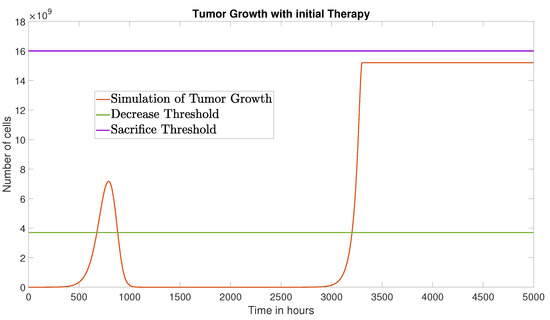

As described in [8], an effective dendritic cell immunotherapy protocol for reducing tumor cell burden within a relatively short time consists of administering dendritic cells once a week for three consecutive weeks, i.e., specifically at 168, 336, and 504 h.

To replicate the experimental results under this therapeutic protocol, the mathematical model defined by Equations (10)–(17) is employed. At this stage, parameter identification focuses on those associated with dendritic cell immunotherapy: the maximal cytotoxic cell efficiency , the percentage of dendritic cells that effectively activate the immune response , and the time delay involved in the activation of effector cells after immunotherapy administration. As in the previous phase, the GA and PSO metaheuristics were implemented to fit the experimental data reported in [8].

The previously identified parameters via PSO (, , and ) were retained, along with the tumor carrying capacity cancer cells. The remaining model parameters are listed in Table 2.

Initial values for , , and were taken from [8]: , , and h. The initial conditions considered were: cancer cells, , , , , , , and receptors.

With these initial parameter values, a NRMSE of 0.3539 with respect to the experimental data is obtained. To improve the accuracy of the model, GA and PSO metaheuristics were implemented to minimize the NRMSE between the experimental average tumor growth curve of the treated mice and the interpolated tumor cell population T obtained from simulations of the model (10)–(17).

The search space for both GA and PSO metaheuristics was defined as follows: , , in accordance with the experimentally observed range reported in [24], and h.

The configuration of the GA and PSO metaheuristics (population size, initialization method, parent selection strategy, crossover type, generation structure, and stopping criteria) and the cost function were kept identical to that used in the previous stage.

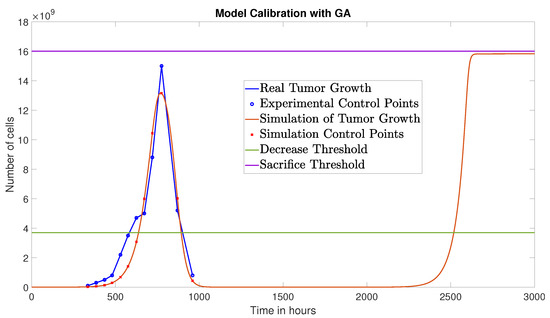

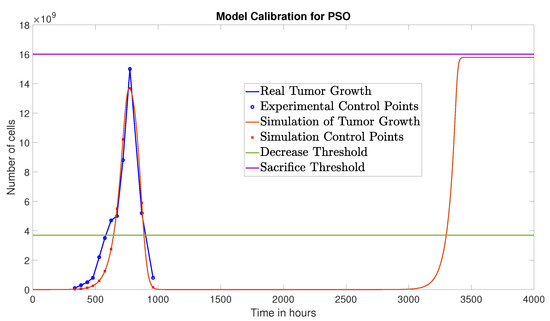

The GA converged at the 15th generation, yielding the following parameter values: , c, and h, with a corresponding NRMSE of 0.0809. Figure 4 presents the simulation results obtained with these parameters in conjunction with the experimental data from [8].

The PSO algorithm converged at the 13th iteration, identifying the following parameters: , c, and h. The resulting NRMSE was 0.0791. Figure 5 displays the corresponding simulation results for tumor cell dynamics using the parameters identified via PSO.

As in the previous phase, the parameter set obtained by PSO yielded the lowest NRMSE value and will therefore be adopted for the optimization of the immunotherapy protocol.

It is important to emphasize that the protocol under study achieves a notable reduction of tumor cells. However, experimental results indicate that, at its peak, tumor burden reaches a level close to the sacrifice threshold. The goal of the immunotherapy optimization approach presented in the next section is to improve these outcomes by ensuring that tumor cell levels remain below those observed with the current protocol.

It should be noted that although tumor regression or elimination can be achieved, cancer recurrence is observed, that is, tumor cells eventually resume growth, and the resulting curve tends to saturate near the carrying capacity of cancer cells, reflecting the behavior seen in real biological systems.

4.4. Scheduling Optimization of Dendritic Cell Immunotherapy

Once the parameter values enabling a reliable reproduction of tumor cell dynamics were identified (by fitting the experimental data from the immunotherapy described in the previous section), we assert that the mathematical model defined in Equations (10)–(17) is biologically appropriate for deriving optimized therapeutic schedules from an initial baseline protocol.

To determine an optimal administration schedule that enhances the efficacy of dendritic cell immunotherapy, it is necessary to define a suitable cost function. In this study, we consider the minimization of the area under the curve (AUC) of tumor cells T. The AUC is computed by evaluating the tumor cell population over time, given a candidate set of injection times (see Equation (20)).

Assuming a fixed dose per injection, metaheuristic optimization algorithms are used to identify the optimal set of administration times s that minimizes the cost function. The cardinality of the set s, that is, the number of injections, is also fixed throughout the optimization process.

As initial schedule, we adopt the protocol proposed in [8], which consists of four dendritic cell injections, each with a dose of cells, administered at

This schedule serves as a reference due to its reduced total dose compared to the experimental scheme presented in [27] ( dendritic cells once a week for 3 weeks). Accordingly, the number of injection times is set to four, and the individual dose remains fixed ().

The parameter values used in the simulations correspond to those identified in the previous stages: , , , , c, and h. The remaining parameters are adopted from [8] (see Table 2), with the exception of the tumor carrying capacity, which is set to cells.

The optimization problem is solved in a search space . Once a solution is found, the injection times are ordered in ascending sequence to comply with the scheduling constraints defined in (18).

To simulate tumor-related mortality, a Simulink block was implemented such that when the tumor population exceeds 95% of its carrying capacity , it remains constant at that level for the remainder of the simulation, thereby ignoring the effects of subsequent dendritic cell administrations.

Figure 6 illustrates the tumor cell dynamics under the initial protocol. Over a 5000-h simulation window, the area under the tumor cell curve is cell·h.

Figure 6.

Tumor growth under the initial therapy over a 5000-h simulation period.

To optimize the administration schedule, the metaheuristic algorithms GA and PSO were implemented. The algorithm parameters and initial conditions were set identically to those used in the previous stages.

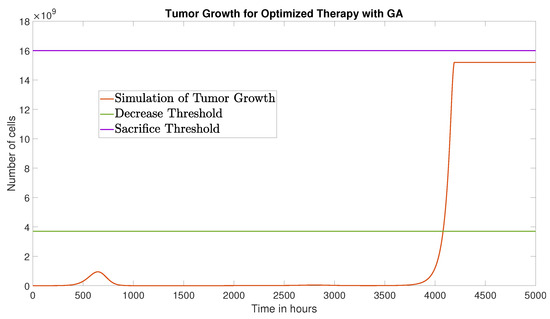

The GA converged after 113 generations, yielding the optimized schedule

This result suggests an effective strategy of three injections: one at time zero with a double dose (), and two subsequent injections at standard dose. The corresponding tumor growth is shown in Figure 7, with a reduced AUC of cell·h.

Figure 7.

Tumor growth under the optimized therapy obtained via GA, over a 5000-h time window.

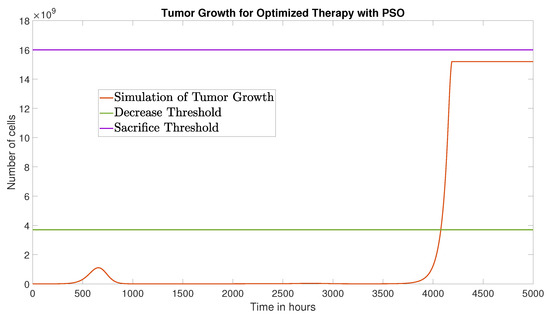

The PSO algorithm converged after 11 iterations, yielding a schedule

The corresponding tumor dynamics are presented in Figure 8, with an AUC of cell·h.

Figure 8.

Tumor growth under the optimized therapy obtained via PSO, over a 5000-h time window.

It is noteworthy that both optimization strategies converged to similar therapeutic schedules. Specifically, the outcomes suggest the administration of three injections: an initial one with a double dose at the beginning of the treatment, followed by two standard-dose injections at approximately 1342 h (59 days) and 2270 h (94 days).

Table 3 summarizes the numerical differences between the baseline protocol and the optimized schedules. The table reports the AUC values and percentage reductions in AUC over a 5000-h window, as well as number of injections and total administered dose for each protocol. These results show that both GA and PSO produce substantial reductions in tumor burden—approximately 52% relative to the baseline—without increasing the total dendritic cell dose. This table complements the visual comparison provided in Figure 7 and Figure 8 and highlights the magnitude of improvement achieved through optimization.

Table 3.

Comparison between the baseline protocol and the optimized schedules obtained via GA and PSO.

5. Discussion

This section highlights the contributions of the obtained results in comparison to previous studies, particularly those presented in [8,18]. Furthermore, it emphasizes the limitations of the considered mathematical model.

As discussed in Section 2, the adoption of the generic growth law yields a more realistic representation of tumor progression compared to the traditional Gompertz growth law. Although both models predict that the tumor cell population saturates at the carrying capacity , the value used in [8] () does not align with experimental observations, indicating that host death (mouse) occurs when the tumor cell count reaches approximately .

As presented in Section 4.2, the optimized value of the tumor growth rate () is an order of magnitude greater than the value reported in [8], suggesting that the Gompertz model is insufficient to reproduce realistic tumor dynamics. This substantial difference further supports the use of the generic growth law.

In light of the updated value for and the estimated growth rate , it was necessary to re-optimize the sensitive model parameters , , and , as identified in [8]. The optimized values for the maximal cytotoxic efficiency of immune cells ( with GA and with PSO) are close to the previously reported value (). However, the identified values for the time delay and the effective activation rate of dendritic cells differ significantly: GA yields h and c, while PSO yields h and c, in contrast to the values considered in [8] ( h and c). Importantly, both parameters were estimated within experimentally supported ranges, ensuring that the optimized values remain biologically plausible and do not require extrapolation beyond experimentally observed limits. To verify that the fitting procedure did not compensate for structural bias, we compared the quality of fit using the original versus optimized parameters. With the original parameters, the NRMSE between the simulated immunotherapy response and experimental data was 0.3539, while the optimized parameters reduced the NRMSE to 0.0791, representing a 78% improvement in model performance. Moreover, independent optimization runs using both GA and PSO consistently converged to similar parameter regions, indicating that the optimized values are intrinsic to the model-data relationship rather than artifacts of local minima or compensatory tuning.

Regarding the model identifiability, the presented analyses suggest that practical non-identifiability is minimal. GA and PSO converged to the same region across repeated runs, and the parameters of interest affect distinct temporal features of the tumor–immune dynamics. This separation in influence reduces the likelihood of interchangeable solutions. The substantial reduction in NRMSE further supports reliable parameter calibration. In summary, while no nonlinear biological model is entirely immune to partial non-identifiability, the combined evidence from independent algorithms, repeated optimizations, and the distinct dynamical roles of parameters indicates that the calibrated values for the system parameters are robust, biologically grounded, and practically identifiable, rather than artifacts of structural bias or overfitting.

A further contribution of this work is the substantial reduction in both the number of administrations and the total dendritic-cell dose required to achieve tumor control. The PSO and GA optimized protocols obtained here recommend three injections within a 3000-h window: an initial dose of DCs followed by two boosters of DCs, for a total of DCs. This dose efficiency contrasts sharply with previously proposed strategies. In [7], tumor eradication was observed only for doses DCs, regardless of the dosing interval tested (48–192 h), far exceeding the doses used in our optimized protocol. In [8], an initial four-dose schedule was optimized into two injections: a large pulse of DCs at h and a second dose of DCs at h, totaling DCs over a 1000-h horizon, matching our total dose but over a shorter treatment window. Finally, in [18], the optimized protocol consists of 53 injections of DCs each, administered over a 5000-h time window, yielding a total dose of DCs, more than four times higher than the dose required by our optimized schedules. Taken together, these comparisons indicate that the protocols derived in this work achieve tumor control with substantially fewer injections and markedly lower cumulative doses than those previously reported in the literature.

Figure 7 and Figure 8 show that, using the optimized protocols, the tumor cell population remains below the decrease threshold for approximately 4000 h and stabilizes below the experimental sacrifice threshold thereafter. These outcomes are markedly improved compared to those reported in [8,18].

The optimal dosing schedules result in very long gaps between doses (an initial double dose at the beginning of treatment, followed by two injections at approximately 59 and 94 days). This extended spacing does not depend on the persistence of DCs themselves, which have a limited lifespan of 3–7 days in lymphoid tissues [32]. Instead, the efficacy of these schedules relies on the capacity of injected DCs to prime and establish long-lived memory T-cell populations during their brief window of activity [33]. Once activated by antigen-presenting DCs, a subset of CD8 T cells differentiates into memory cells that persist for months in the absence of continuous antigenic stimulation [34]. Subsequent DC booster doses do not require the survival of previous DC injections; instead, they recall and rapidly re-expand these established memory populations [25].

Crucially, this long-term protection has been directly demonstrated experimentally in models analogous to ours. In [35], vaccination with Bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) loaded with B16 melanoma antigens induced protective immunity against tumor rechallenge 60 days later. Similarly, Umansky et al. detected functional melanoma-specific memory T cells in mice more than 20 weeks after vaccination with BMDCs [36].

These studies confirm that standard BMDC vaccines can generate robust memory responses that persist well beyond the 2–3 month intervals identified by our optimization, providing strong biological validation of our computational results.

Despite adopting a more realistic immune activation efficiency (), the optimized protocols obtained via GA and PSO still achieve achieves tumor control for approximately 4000 h. This further emphasizes the robustness and clinical relevance of the identified vaccination strategies.

The reactivation of tumor growth indicates the necessity of additional therapeutic interventions to sustain long-term treatment efficacy.

The main limitations of the study related to the mathematical model are described below.

- I.

- The model is deterministic and therefore cannot capture stochastic fluctuations, rare events, or agent-level heterogeneity; stochastic differential equation approaches or agent-based models would be required to quantify the influence of chance and spatial structure on delayed regrowth and recurrence [37].

- II.

- The model does not include explicit mechanisms for T-cell functional exhaustion or progressive loss of effector function under chronic antigen exposure; incorporating exhaustion dynamics or state-switching effector phenotypes may be essential for predicting long-term tumor control [38,39].

- III.

- Third, cytokine dynamics and cytokine-mediated toxicity (e.g., cytokine release syndrome) were not represented; including cytokine compartments and toxicity constraints would enable safety-aware optimization of vaccine dose and schedule [40].

- IV.

- The model does not incorporate inter-individual variability in immune competence, tumor antigenicity, or DC pharmacokinetics; population-level (mixed-effects) modeling or uncertainty quantification would be necessary to evaluate robustness and to identify individualized dosing strategies [41].

- V.

- Practical clinical constraints (such as patient adherence, clinic availability, and discretized injection times) were not included in the continuous-time optimization; incorporating feasibility constraints and discrete-time decision variables would better approximate real-world implementation [42].

These limitations define clear avenues for future work, including stochastic or agent-based extensions, exhaustion and cytokine submodels, population-based calibration, and clinically feasible optimization frameworks.

6. Conclusions

The results presented in this paper suggest that metaheuristic optimization can be a powerful tool for designing dynamic and adaptive treatment protocols. Future research may explore alternative cost functions that incorporate clinically relevant criteria such as toxicity, immune exhaustion, or patient-specific tumor characteristics. Additionally, introducing full dose optimization, allowing injection sizes to vary rather than remain fixed, could provide greater flexibility and lead to more effective treatment strategies. Moreover, randomized or adaptive vaccination schedules could be investigated to increase robustness against biological variability or uncertainties in model parameters.

The framework presented here opens avenues for the development of more precise and efficient immunotherapy strategies. In addition to optimizing treatment delivery, the results highlight the potential for using mathematical models as decision-support tools in oncology, guiding therapeutic interventions that maintain tumor dynamics within controllable thresholds during and after the treatment period.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.S. and O.P.-R.; methodology, B.S., O.P.-R., C.A.-I., O.O.S.-G.; software, B.S., O.P.-R. and L.T.; validation, B.S., O.P.-R. and L.T.; formal analysis, B.S., O.P.-R. and L.T.; investigation, B.S., O.P.-R. and L.T.; resources, B.S. and O.P.-R.; data curation, B.S., O.P.-R. and L.T.; writing—original draft preparation, L.T.; writing—review and editing, B.S., O.P.-R., C.A.-I., O.O.S.-G.; visualization, B.S., O.P.-R. and L.T.; supervision, B.S. and O.P.-R.; project administration, B.S. and O.P.-R.; funding acquisition, B.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Secretariat of Science, Humanities, Technology, and Innovation (Secihti) of Mexico under the grant CF-2023-I-722.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funder had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DC | Dendritic cell |

| ODE | Ordinary differential equations |

| GA | Genetic Algorithm |

| PSO | Particle Swarm Optimization |

| MHC | Major Histocompatibility Complex |

| NRMSE | Normalized Root Mean Square Error |

| BMDCs | Bone Marrow-derived Dendritic Cells |

| AUC | Area under the curve |

References

- Bol, K.F.; Schreibelt, G.; Bloemendal, M.; van Willigen, W.W.; Hins-de Bree, S.; de Goede, A.L.; de Boer, A.J.; Bos, K.J.H.; Duiveman-de Boer, T.; Olde Nordkamp, M.A.M.; et al. Adjuvant dendritic cell therapy in stage IIIB/C melanoma: The MIND-DC randomized phase III trial. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heras-Murillo, I.; Mañanes, D.; Munné, P.; Núñez, V.; Herrera, J.; Catalá-Montoro, M.; Alvarez, M.; del Pozo, M.A.; Melero, I.; Wculek, S.K.; et al. Immunotherapy with conventional type-1 dendritic cells induces immune memory and limits tumor relapse. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bol, K.F.; Schreibelt, G.; Gerritsen, W.R.; De Vries, I.J.M.; Figdor, C.G. Dendritic cell–based immunotherapy: State of the art and beyond. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 1897–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, H.; Shurin, M.R.; Han, B. Optimizing dendritic cell-based immunotherapy for cancer. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2007, 6, 333–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.W.; Yam, J.W.P.; Mao, X. Dendritic cell vaccines: A shift from conventional approach to new generations. Cells 2023, 12, 2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subtirelu, R.C.; Teichner, E.M.; Ashok, A.; Parikh, C.; Talasila, S.; Matache, I.M.; Alnemri, A.G.; Anderson, V.; Shahid, O.; Mannam, S.; et al. Advancements in dendritic cell vaccination: Enhancing efficacy and optimizing combinatorial strategies for the treatment of glioblastoma. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1271822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castillo-Montiel, E.; Chimal-Eguía, J.; Tello, J.; Piñon-Zaráte, G.; Herrera-Enríquez, M.; Castell-Rodríguez, A. Enhancing dendritic cell immunotherapy for melanoma using a simple mathematical model. Theor. Biol. Med Model. 2015, 12, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangel-Reyes, J.; Chimal-Eguia, J.C.; Castillo-Montiel, E. Dendritic immunotherapy improvement for an optimal control murine model. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2017, 2017, 5291823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, A.; Martinez-Usatorre, A.; Liu, Y.; Demagny, H.; Li, L.; Mohammadzadeh, Y.; Hurtado, A.; Hicham, M.; Henneman, L.; Pritchard, C.E.J.; et al. Dendritic cell progenitors engineered to express extracellular-vesicle–internalizing receptors enhance cancer immunotherapy in mouse models. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 9148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, R.; Wang, F.; Jeffery, G.; Marty, V.; Kuniyoshi, J.; Bade, E.; Ryback, M.E.; Weber, J. Phase I trial of intravenous peptide-pulsed dendritic cells in patients with metastatic melanoma. J. Immunother. 2001, 24, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Lei, J. Mathematical modeling of tumor-immune interactions: Methods, applications, and future perspectives. CSIAM Trans. Life Sci. 2025, 1, 200–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaghi, C.; Rodallec, A.; Fanciullino, R.; Ciccolini, J.; Mochel, J.P.; Mastri, M.; Poignard, C.; Ebos, J.M.; Benzekry, S. Population modeling of tumor growth curves and the reduced Gompertz model improve prediction of the age of experimental tumors. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2020, 16, e1007178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, H.; Jaafari, H.; Dobrovolny, H.M. Differences in predictions of ODE models of tumor growth: A cautionary example. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burden, T.N.; Ernstberger, J.; Fister, K.R. Optimal control applied to immunotherapy. Discret. Contin. Dyn. Syst. Ser. B 2004, 4, 135–146. [Google Scholar]

- Castiglione, F.; Piccoli, B. Cancer immunotherapy, mathematical modeling and optimal control. J. Theor. Biol. 2007, 247, 723–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalili, P.; Vatankhah, R. Optimal control design for drug delivery of immunotherapy in chemoimmunotherapy treatment. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2023, 229, 107248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castiglione, F.; Piccoli, B. Optimal Control in a Model of Dendritic Cell Transfection Cancer Immunotherapy. Bull. Math. Biol. 2006, 68, 255–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chimal-Eguia, J.C.; Rangel-Reyes, J.C.; Paez-Hernandez, R.T. Improving Convergence in Therapy Scheduling Optimization: A Simulation Study. Mathematics 2020, 8, 2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sima, S.A.; Alireza, M. Metaheuristics and Pontryagin’s minimum principle for optimal therapeutic protocols in cancer immunotherapy: A case study and methods comparison. J. Math. Biol. 2020, 81, 691–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talbi, E.G. Metaheuristics: From Design to Implementation; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchiwata, S.; Tsuji, Y. Computational design of clinical trials using a combination of simulation and the genetic algorithm. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst. Pharmacol. 2023, 12, 522–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopal, S.P.; Jeevan, K.; Cheak, T.Z. Optimization of Chemotherapy Using Hybrid Optimal Control and Swarm Intelligence. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 28873–28886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoularis, A.; Wallace, J. Analysis of logistic growth models. Math. Biosci. 2002, 179, 21–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdijk, P.; Aarntzen, E.H.; Lesterhuis, W.J.; Boullart, A.I.; Kok, E.; van Rossum, M.M.; Strijk, S.; Eijckeler, F.; Bonenkamp, J.J.; Jacobs, J.F.; et al. Limited Amounts of Dendritic Cells Migrate into the T-Cell Area of Lymph Nodes but Have High Immune Activating Potential in Melanoma Patients. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15, 2531–2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.Y.; Kim, C.H.; Sohn, H.J.; Oh, S.T.; Kim, S.G.; Kim, T.G. The optimal interval for dendritic cell vaccination following adoptive T cell transfer is important for boosting potent anti-tumor immunity. Vaccine 2007, 25, 7322–7330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, K.; Roy, S.; Davim, J.P. Soft Computing Techniques for Engineering Optimization; Science, Technology, and Management Series; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Piñón-Zárate, G.; Herrera-Enríquez, M.Á.; Hernández-Téllez, B.; Jarquín-Yáñez, K.; Castell-Rodríguez, A.E. GK-1 Improves the Immune Response Induced by Bone Marrow Dendritic Cells Loaded with MAGE-AX in Mice with Melanoma. J. Immunol. Res. 2014, 2014, 158980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, P.K.; Bhardwaj, D.; Karnik, R. Human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor: The protein and its current & emerging applications. Indian J. Biotechnol. 2007, 6, 435–448. [Google Scholar]

- Sang, M.; Wang, L.; Ding, C.; Zhou, X.; Wang, B.; Wang, L.; Lian, Y.; Shan, B. Melanoma-associated antigen genes—An update. Cancer Lett. 2011, 302, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meenhard, H.; Mizuho, F.K. What Is a Good Model for Melanoma? J. Investig. Dermatol. 2010, 130, 911–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, K.; Taha, B. Metaheuristics: Outlines, MATLAB Codes and Examples; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Fontecha, A.; Sebastiani, S.; Höpken, U.E.; Uguccioni, M.; Lipp, M.; Lanzavecchia, A.; Sallusto, F. Regulation of Dendritic Cell Migration to the Draining Lymph Node. J. Exp. Med. 2003, 198, 615–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wherry, E.J.; Ahmed, R. Memory CD8 T-Cell Differentiation during Viral Infection. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 5535–5545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaech, S.M.; Ahmed, R. Memory CD8+ T cell differentiation: Initial antigen encounter triggers a developmental program in naïve cells. Nat. Immunol. 2001, 2, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldszmid, R.S.; Idoyaga, J.; Bravo, A.I.; Steinman, R.; Mordoh, J.; Wainstok, R. Dendritic cells charged with apoptotic tumor cells induce long-lived protective CD4+ and CD8+ T cell immunity against B16 melanoma. J. Immunol. 2003, 171, 5940–5947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umansky, V.; Abschuetz, O.; Osen, W.; Ramacher, M.; Zhao, F.; Kato, M.; Schadendorf, D. Melanoma-Specific Memory T Cells Are Functionally Active in Ret Transgenic Mice without Macroscopic Tumors. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 9451–9458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altrock, P.M.; Liu, L.L.; Michor, F. The mathematics of cancer: Integrating quantitative models. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2015, 15, 730–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wherry, E.J. T cell exhaustion. Nat. Immunol. 2011, 12, 492–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pauken, K.E.; Wherry, E.J. Overcoming T cell exhaustion in infection and cancer. Trends Immunol. 2015, 36, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Arulraj, T.; Ippolito, A.; Popel, A.S. Quantitative Systems Pharmacology Modeling in Immuno-Oncology: Hypothesis Testing, Dose Optimization, and Efficacy Prediction; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Simoni, Y.; Becht, E.; Fehlings, M.; Loh, C.Y.; Koo, S.L.; Teng, K.W.W.; Yeong, J.P.S.; Nahar, R.; Zhang, T.; Kared, H.; et al. Bystander CD8+ T cells are abundant and phenotypically distinct in human tumour infiltrates. Nature 2018, 557, 575–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenhart, S.; Workman, J.T. Optimal Control Applied to Biological Models; Chapman and Hall/CRC: New York, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).