Abstract

In individuals with Parkinson’s disease (PD), bradykinesia severity is related to physical activity (PA) inside homes. We aimed to investigate the effectiveness of the Lee Silverman Voice Treatment (LSVT)® BIG intervention in increasing at-home PA in individuals with PD. To evaluate the effect of the intervention, we compared pre- and post-intervention scores on the Movement Disorder Society-sponsored revision of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS) Parts 3 and 2, as well as the time spent at home in three categories of PA intensity. For statistical testing, paired t-tests were used when the data met the assumptions of normality, and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was applied otherwise. Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05. This preliminary retrospective observational study included 10 eligible individuals with PD (4 males). The participants’ mean age was 71.0 ± 10.8 years, with median Hoehn and Yahr stage 3 [interquartile range: 1 to 4]. The MDS-UPDRS Part 3 score, bradykinesia score calculated from a part of that score, and the MDS-UPDRS Part 2 score significantly improved after the intervention (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, p < 0.05). The time spent in sedentary behavior (SB) significantly decreased from 516.4 ± 72.6 to 484.0 ± 70.0 min, whereas that spent in light PA (LPA) significantly increased from 137.8 ± 46.2 to 169.5 ± 32.1 min (paired t-test, p < 0.05). The time spent on moderate-to-vigorous PA (MVPA) did not change significantly (paired t-test, p = 0.533). The results suggested that LSVT® BIG is an effective intervention for increasing at-home PA in individuals with PD. In addition, regarding the specific details of the increase, the time spent on MVPA may not change, and the increase may be mainly attributed to increased LPA and reduced sedentary time.

1. Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder affecting approximately 6 million people worldwide, with prevalence increasing with age [1]. PD is slightly more common in men than in women, and incidence rates vary across geographic regions, with higher rates reported in Europe and North America compared to Asia and Africa [2,3]. The number of people living with PD is expected to rise sharply as the global population ages, creating an increasing public health burden [4]. Mobility decline is a major concern in PD, and its progression typically follows a recognizable trajectory. In the early phase, many patients retain independent mobility; however, gait disturbances, impaired balance, and increased fall risk tend to emerge gradually as PD advances. Mobility limitations become especially evident around the mid- to late-stages (Hoehn & Yahr [HY] stage 3–4), when postural instability and gait impairments frequently lead to reduced community ambulation and a growing need for assistance [5,6]. At this transitional point, patients often shift from independent walking to the use of mobility aids such as canes or walkers and may eventually require physical assistance [7,8]. In addition, non-motor symptoms such as cognitive impairment, depression, anxiety, dementia, fatigue, and sleep disturbances affect activities of daily living (ADLs) and quality of life in individuals with PD [9].

Various medical interventions are available for individuals with PD [10,11,12]. Pharmacological treatments, including dopaminergic medications such as levodopa and dopamine agonists, can partially alleviate motor symptoms of PD, including bradykinesia, rigidity, and tremor. These medications can partially alleviate motor symptoms; however, they may not fully restore daily physical activity (PA) or eliminate disabilities and dependence in ADLs [10]. Cognitive interventions have shown some benefits for memory and executive function, but evidence for their impact on motor activity is limited [11]. Physical exercise interventions, particularly structured and task-specific physiotherapy programs, have demonstrated significant benefits for motor function, walking ability, and ADLs in individuals with PD [12].

PD is manifested by multiple motor symptoms due to the loss of dopamine-producing neurons in the motor circuits of the basal ganglia, which are essential for motor control and coordination [9,13]. Motor symptoms, including bradykinesia, rigidity, tremor, and postural instability, progressively worsen and significantly impact ADLs [14,15]. For example, bradykinesia slows down overall body movements and reactions, leading to disabilities and dependence in most ADLs (e.g., dressing, grooming, eating, writing) [9,16].

In individuals with PD, the level of at-home physical activity (PA) is an important indicator of bradykinesia, because the severity of bradykinesia influences disability and dependence in ADLs [17]. Hirakawa et al. examined how the severity of bradykinesia relates to the amount of at-home PA performed, classified into three intensity levels—sedentary behavior (SB), light PA (LPA), and moderate-to-vigorous PA (MVPA)—in individuals with PD. Their analysis demonstrated a statistically significant inverse association between bradykinesia severity and the time allocated to LPA inside the home. [17]. These three intensity levels are categorized based on widely used standard definitions [18]. SB is defined as waking activities associated with very low energy expenditure (1.5 metabolic equivalents [METs] or less), typically performed in seated or reclined positions [18]. LPA is defined as waking activities requiring an energy expenditure greater than 1.5 METs but less than 3.0 METs, and this category includes activities such as housework, personal grooming, and light indoor gardening [18,19]. MVPA is defined as activities with an energy expenditure of 3.0 METs or higher, and this category includes more purposeful movements such as brisk walking, fast cycling, or other activities that elevate heart rate and breathing above light-intensity levels [18,20]. Thus, rehabilitation interventions focusing on bradykinesia may be important to improve at-home PA in individuals with PD.

As one of the rehabilitation interventions for bradykinesia, the effectiveness of Lee Silverman Voice Treatment (LSVT)® BIG has been reported [21,22,23,24,25,26,27]. LSVT® BIG is an individually tailored, disease-specific task-based training designed for individuals with PD. This straining enhances self-perception of progressively smaller and slower movements by incorporating external cues. Furthermore, focusing on movement amplitude facilitates self-correction and consequently improves bradykinesia. The goal of this intervention is to achieve automatic integration of larger movements into ADLs [21,22,23]. Previous research on LSVT® BIG has predominantly concentrated on motor outcomes. Several studies have reported significant improvements in clinical motor measures, such as gait speed and balance performance, following intervention [26,27]. Iwai et al. (2024) investigated the effectiveness of LSVT® BIG therapy on bradykinesia in individuals with PD [25]. Following 4 weeks of intervention with LSVT® BIG therapy, a statistically significant improvement was observed in bradykinesia scores derived from Part 3 of the Movement Disorder Society–sponsored revision of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS).

However, despite improvements in clinical motor outcomes, it remains unclear whether LSVT® BIG can increase PA in ADLs, particularly in individuals living at home. Moreover, few studies have objectively quantified changes in physical activity using accelerometers. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the effectiveness of the LSVT® BIG intervention in increasing at-home PA in individuals with PD. Specifically, this effect was addressed from three perspectives. First, we replicated previous findings by comparing changes in motor symptoms, which include bradykinesia, and ADL in individuals with PD before and after LSVT® BIG (Perspective 1). Second, we investigated the changes in the time spent in three PA intensities (SB, LPA, and MVPA) at home before and after the intervention (Perspective 2). Third, we investigated the changes in the time spent on specific activities, including ADLs, at three intensity levels before and after the intervention (Perspective 3).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

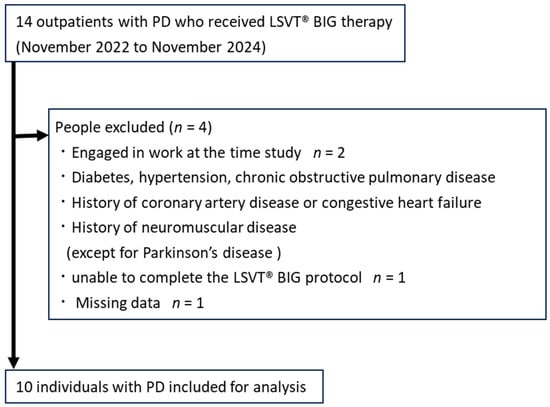

This was a preliminary retrospective observational study conducted at a single hospital in Gifu Prefecture, Japan. This study is reported following the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology statement [28]. Figure 1 shows the flowchart of individual screening. We identified outpatients with PD who were instructed to undergo LSVT® BIG therapy by a neurologist by searching the Kawamura Hospital database between October 2022 and November 2024. Then, we identified the individuals who met the inclusion criteria and did not meet the exclusion criteria through a chart review. The following individuals were included in this study: (1) individuals with PD diagnosed by a neurologist, (2) those with PD classified as HY stages 1–4, and (3) those who could walk independently (assistive devices were used if necessary). The following individuals were excluded from this study: (1) individuals who were engaged in work at the time of study participation, (2) those with uncontrolled diabetes or hypertension and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, (3) those with a history of coronary artery disease or congestive heart failure, (4) those with a history of neuromuscular disease other than PD, (5) those who were unable to complete the LSVT® BIG protocol, and (6) those with missing data during the intervention period.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of individual screening.

Generally, the number of participants in a preliminary study is determined by considering the expected effect size in the subsequent main trial [29]. According to Whitehead et al. (2016), the recommended sample sizes for an external pilot trial with 90% power and a two-sided 5% significance level are 15 participants per arm for a medium effect size (d ≈ 0.5) and 10 per arm for a large effect size (d ≈ 0.8) [29]. Because our study assumed a medium-to-large effect size for a potential future full-scale trial, we selected a sample size of 10 participants for this preliminary retrospective observational study. However, it should be noted that the small sample size and absence of a control group represent important methodological limitations that may affect the generalizability and causal interpretation of the findings.

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors and the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, and it received approval from the Human Ethics Committee of Fujita Health University (approval no. HM22-198). Written informed consent was not required owing to the retrospective observational nature of the study. Nevertheless, to ensure that participants had the opportunity to decline the use of their medical records for research purposes, details of the study were made available via an opt-out notice displayed on the hospital bulletin board.

2.2. Intervention

LSVT® BIG was prescribed to individuals with PD who were able to understand verbal instructions and were taking a stable dose of levodopa without any medication changes during the intervention period. The participants completed 16 sessions of the LSVT® BIG program under the supervision of certified LSVT® BIG therapists. The intervention consisted of 1 h sessions conducted on 4 consecutive days each week for 4 weeks. During each session, the participants performed exercises while maintaining a perceived exertion level of 7–8 out of 10 on a modified Borg Scale.

Each session incorporated the four primary components of the LSVT® BIG program: whole-body movements, functional component tasks, hierarchy tasks, and BIG walking. The task difficulty in each component progressively increased each week based on the participant motor performance gains [21,22,23]. As part of whole-body movements, the participants performed seven standardized exercises that included multidirectional reaching, stepping, weight shifting, and holding postures. As part of the functional component tasks, the participants engaged in five individualized activities selected to address specific movement difficulties in ADLs identified by the participants or their families (e.g., putting on a jacket one arm at a time while standing, side-stepping, passing a loop through one leg while standing on the other, walking through a narrow passage, and standing up). As part of the hierarchy tasks, the participants engaged in goal-directed, complex movements tailored to their specific needs and interests. These activities were directly related to the participants’ personal goals and designed to improve sequential movement patterns. As part of the BIG walking, the participants were instructed to walk with pronounced arm swings and increased stride lengths.

In addition, according to instructions, a daily home exercise program was performed once on days with LSVT® BIG sessions and twice on those without. The exercise program consisted of condensed and easy-to-perform version of LSVT® BIG performed in the hospital: all exercises included in whole-body movements, standing up exercise included in functional component tasks, and BIG walking. For exercises requiring hospital equipment, the therapists instructed patients on alternative methods without equipment. A homework exercise book was also provided to enhance adherence and accountability. Adherence to the home exercise program was monitored verbally, with therapists confirming completion of the prescribed exercises during each session.

2.3. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

The following clinical assessment information was collected from all participants: sex, age, Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score, HY stage, time since PD diagnosis, and levodopa equivalent daily dose (LEDD). The MMSE is a widely used 30-point cognitive screening tool that evaluates orientation, registration, attention, recall, language, and visuospatial abilities, and its reliability and ease of administration have been well established in clinical settings [30]. The HY stage was used to investigate disease severity [31]. The total LEDD was calculated using established conversion factors for antiparkinsonian drugs [32].

2.4. Measurement of Motor Symptoms and Disabilities and Dependences of Activities of Daily Living

All participants were assessed using the MDS-UPDRS Part 3 for motor symptoms, including bradykinesia, and the MDS-UPDRS Part 2 for disabilities and dependence in ADLs. The MDS-UPDRS Part 3 is an examination assessing motor manifestations such as tremor, rigidity, bradykinesia, and postural instability. Part 3 of the MDS-UPDRS demonstrated high concurrent validity and reliability in individuals with PD. This scale consists of 33 items, with a maximum score of 132, where higher scores indicate more severe motor symptoms [33]. In addition, we used definitions reported in a previous study to calculate the bradykinesia score (3.4–3.8 and 3.14), with a maximum score of 44, where higher scores indicate more severe bradykinesia [34]. Part 2 of the MDS-UPDRS is a patient-reported measure consisting of items that capture functional difficulties related to speech, eating, dressing, hygiene, handwriting, and mobility. MDS-UPDRS Part 2 demonstrated high concurrent, convergent, and predictive validity in individuals with PD. The MDS-UPDRS Part 2 includes 13 items, with a maximum score of 52, where higher scores reflect more severe disabilities and dependence in ADLs [35]. These assessments were performed within a week of the LSVT® BIG intervention by certified LSVT® BIG therapists who did not perform the intervention. All examinations were performed during the on-state to eliminate potential influences of the medication cycle (e.g., on/off state). Based on the above procedures, the MDS-UPDRS Part 3 score, bradykinesia score, MDS-UPDRS Part 2 score were calculated for each participant.

2.5. At-Home Physical Activity Measurement

At-home PA was assessed using a combination of a triaxial accelerometer and daily activity diary, based on the methods used in a previous study [36]. PA was recorded using a triaxial accelerometer (Active-style Pro HJA-750C; Omron Healthcare, Kyoto, Japan) [37]. This device measures acceleration in three spatial dimensions—anteroposterior, mediolateral, and vertical—using a built-in sensor system [37]. The accelerometer samples acceleration signals at 32 Hz and processes them using a proprietary algorithm that estimates METs at 10 s intervals [37]. Output data are aggregated into 1 min periods for analysis. The device is compact and lightweight (40 × 52 × 12 mm; 23 g), making it suitable for continuous use during daily life without imposing a substantial burden [37]. Previous research has reported a significant positive correlation between estimates obtained using this model and energy expenditure measured by doubly labeled water (r = 0.46, p = 0.04), demonstrating acceptable validity for field-based PA assessments [38]. Participants were asked to wear the accelerometer on their waist during waking hours for 7 consecutive days [39,40]. They were instructed to attach the device immediately after waking and remove it before going to bed, keeping it off only during water-based activities such as bathing or showering [39,40]. A 7-day monitoring period was selected to account for day-to-day variability and ensure inclusion of both weekdays and weekends [41,42]. Based on MET values, PA was categorized into three intensity levels: SB, ≤1.5 METs; LPA, 1.5 < METs < 3.0; and MVPA, ≥3.0 METs [18]. To complement accelerometer data and differentiate between activities inside and outside the home, participants also completed a daily activity diary [18]. The diary was structured into four components: time period (recorded in 10 min intervals), description of activity, location (indoors or outdoors), and an optional free-description space [36]. Participants were asked to record activities twice daily—after lunch and before bedtime—to minimize reduce respondent burden [36]. In accordance with criteria commonly applied in previous studies, accelerometer data were considered valid only when the device was worn for a minimum of 10 h per day on at least 4 days within the week, a threshold regarded as sufficient to provide reliable estimates of daily physical activity [43,44]. For the daily activity diary, earlier work has indicated that records with less than 70 min of unreported time per day can be classified as adequately completed [45]. Based on these standards, only days fulfilling both conditions—acceptable accelerometer wear time and sufficient diary completeness—were included in the analysis [36]. Based on the above procedures, time spent in three different PA intensities (i.e., SB, LPA, and MVPA) at home, as well as that spent engaged in specific activities at each intensity level, were calculated for each participant. The procedure for classifying activities as occurring inside or outside the home was established through discussion among multiple authors who were familiar with this methodology, and coding was performed according to the consensus reached in these meetings.

2.6. Data Analysis

Regarding the statistical analyses of the obtained data, after an assessment for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test, data with normal distribution are presented as the means with standard deviations, whereas those with a non-normal distribution are presented as medians with interquartile ranges (IQR). Normally distributed data were analyzed using paired t-tests, whereas non-normally distributed data were analyzed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. For Perspective 1, we assessed changes in motor symptoms, bradykinesia scores, and disabilities and dependences in ADLs pre and postintervention. For Perspective 2, we assessed changes in the time spent in SB, LPA, and MVPA inside the home pre and postintervention. For Perspective 3, we analyzed changes in the time spent in specific activities inside the home in SB, LPA, and MVPA pre and postintervention. For parametric data, effect sizes (d) were calculated to determine the magnitude of the difference between pre- and post-intervention measurements. Cohen’s d was obtained by dividing the mean change score by the pooled standard deviation for the paired observations. The magnitude of the effect size was interpreted according to Cohen’s guidelines (1988), with values of approximately 0.20, 0.50, and 0.80 indicating small, medium, and large effects, respectively [46]. For non-parametric data, effect sizes (ρ) were calculated by dividing the Z value by the square root of the total number of observations. Following the criteria proposed by Cohen (1988) and colleagues, values of ρ from 0.10 to <0.30 were interpreted as small, those from 0.30 to <0.50 as moderate, and those ≥0.50 as large [46]. All statistical analyses were performed using EZR version 1.68 (EZR Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan), and p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

We included 10 eligible individuals with PD. This study was safely completed in all participants without any adverse effects. The characteristics of the included participants are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participants’ demographic and clinical characteristics.

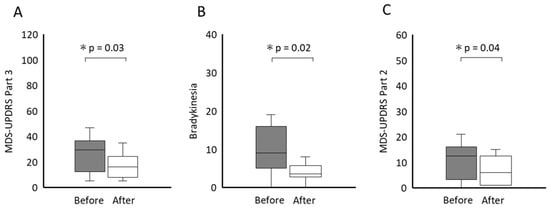

For Perspective 1, Figure 2 shows the changes in motor symptoms, disabilities, and dependence in ADLs before and after the intervention. The MDS-UPDRS Part 3 score, presented as a median with an IQR, significantly improved from 29.5 [12.3 to 37.5] to 16.0 [7.8 to 24.3] points (p = 0.02), with a mean difference of 10.4 points (95% confidence interval [CI], 2.9 to 17.9). The effect size (ρ) was 0.79. Similarly, the bradykinesia significantly decreased from 9.0 [5.0 to 16.0] to 3.5 [2.8 to 5.8] points (p = 0.01), with a mean difference of 5.9 points (95% CI, 3.0 to 9.9). The effect size (ρ) was 0.89. The MDS-UPDRS Part 2 score also showed a significant improvement, decreasing from 12.5 [3.3 to 16.0] to 6.0 [1.0 to 12.5] points (p = 0.04), with a mean difference of 3.5 points (95% CI, 0 to 8.9). The effect size (ρ) was 0.67.

Figure 2.

Scores of the MDS-UPDRS Part 3 (A), Bradykinesia (B), MDS-UPDRS Part 2 (C) before and after the intervention. The central thick lines of the boxplot represent medians; box limits comprise the interquartile range from 25 and 75%. * p < 0.05. MDS-UPDRS, Movement Disorder Society-sponsored revision of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale.

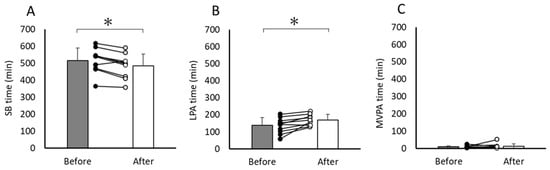

For Perspective 2, Figure 3 compares the time spent in SB, LPA, and MVPA at home before and after the intervention. The time spent in SB inside the home significantly decreased from 516.4 ± 72.6 to 484.0 ± 70.0 min (p = 0.002), with a mean difference of −32.4 min (95% CI, −49.6 to −15.2 min) (effect size (d) was 1.35), whereas that spent in LPA at home significantly increased from 137.8 ± 46.2 to 169.5 ± 32.1 min (p = 0.007), with a mean difference of 31.6 min (95% CI, 10.9 to 52.3 min). The effect size (d) was 1.09. The time spent in MVPA inside the home did not show a significant change (from 9.4 ± 6.5 to 12.3 ± 14.9 min, p = 0.53), with a mean difference of 2.9 min (95% CI, −7.2 to 13.0 min). The effect size (d) was 0.20.

Figure 3.

Changes in time spent on three PA intensities ((A) SB, (B) LPA, (C) MVPA) at home between before and after the intervention. The data are presented as means, and the error bars indicate standard deviation. Lines and dots represent individual data. * p < 0.05. SB, sedentary behavior; LPA, light physical activity; MVPA, moderate-to-vigorous-intensity physical activity.

For Perspective 3, Figure S1 (Supplementary Materials) compares the time spent in specific activities at home at three PA intensities (SB, LPA, and MVPA) before and after the intervention. During the period when the PA intensity was classified as SB, the time spent in rest significantly decreased from 56.7 ± 31.3 to 37.3 ± 36.6 min (p = 0.005), with a mean difference of −19.4 min (95% CI, −31.1 to −7.6 min). The effect size (d) was 1.17. When the PA intensity was classified as LPA, the time spent in dressing and exercise significantly increased from 7.5 ± 5.4 to 13.5 ± 4.1 min (p = 0.024), with a mean difference of 6.0 min (95% CI, 0.98 to 11.0 min) (effect size [d] was 0.85), and from 14.6 ± 12.7 to 31.8 ± 4.7 min (p = 0.001), with a mean difference of 17.2 min (95% CI, 8.9 to 25.4 min) (effect size [d] was 1.40), respectively. When the PA intensity was classified as MVPA, no significant change was noted in the time spent in every specific activity content.

4. Discussion

Regarding the improvement in the MDS-UPDRS Part 3, bradykinesia, and MDS-UPDRS Part 2 scores, the results of this study align with those shown in previous studies [11]. Iwai et al. examined the effects of the LSVT® BIG in 17 individuals with PD [11]. The scores of the UPDRS Part III and the bradykinesia significantly improved after the LSVT® BIG (median [IQR]: 24 [16 to 36] to 18 [13 to 22] points, p < 0.01; 8 [6 to 11] to 6 [5 to 8] points, p < 0.01). The improvements observed in this study may be explained by several clinical and physiological mechanisms associated with LSVT® BIG. This intervention is designed to address one of the core motor impairments of PD—bradykinesia—by training individuals to recognize their tendency to produce movements that are slower and smaller than intended, and consciously recalibrate these movements toward larger, more normal amplitudes [18,20,21]. Therefore, the intervention protocols used in this study may have been appropriate.

Regarding the changes in time spent in SB inside the home, the decrease in time spent at rest may be attributable to improvements in motor symptoms, particularly bradykinesia. Although the decrease in rest and increase in LPA, as discussed below, are assumed to be related, improvements in sit-to-stand ability may promote these changes. A previous study reported that bradykinesia impaired sit-to-stand ability in individuals with PD [47]. Another study reported that individuals with PD with a reduced ability to perform sit-to-stand activities from a chair might face limitations in independent ADLs and PA [48]. LSVT® BIG improves sit-to-stand movements in individuals with PD [49]. However, it should be noted that our study did not directly measure sit-to-stand performance; therefore, these mechanisms remain speculative. In addition to these mechanisms, reduced resting time and improvements in daily physical activity may also be associated with broader motor domains influenced by bradykinesia. Indeed, bradykinesia is known to impair not only transitional movements but also balance, postural coordination, and gait adaptability in individuals with PD [50].

Regarding the changes in the time spent on LPA inside the home, the increase in the time spent dressing may be attributable to improvements in motor symptoms, particularly bradykinesia. Bradykinesia is defined as a reduction in movement speed and amplitude and is associated with a generalized decrease in both spontaneous and intentional movements [14,51]. Bradykinesia influences tasks, such as buttoning during dressing, by reducing the speed or amplitude of movements of the upper and lower limbs [9,14,16]. The reduced difficulty of such tasks may have increased the time spent dressing at an intensity classified as LPA. In addition, intervention protocol used in LSVT® BIG may have contributed to the improvements. The LSVT® BIG protocol incorporated task-based ADL exercises tailored to participants’ or their family needs, designed to promote self-perception of large-amplitude movements in daily life beyond the treatment setting [23,24,25]. As part of the functional component tasks, task-based ADL exercises related to dressing are frequently chosen (e.g., dressing oneself by independently putting on pants and standing on one leg) [52].

However, the increased time spent exercising is difficult to explain solely by the improvement in bradykinesia and may, as a hypothesis, be attributable to the establishment of exercise habits. Indeed, establishing exercise habits is important to maintain regular PA [53]. The LSVT BIG protocol incorporated a daily home-based exercise program. In this program, to enhance participants’ motivation to exercise and encourage self-monitoring their progress, the therapist emphasized the importance of exercising at home and provided exercise notebooks as homework. For the homework requirement, the participants were instructed to check the boxes corresponding to the exercises they performed; previous studies have suggested that motivation, planning, and self-monitoring are important for forming a habit [54,55].

5. Advantages and Disadvantages

Previous studies have reported that LSVT® BIG improves motor outcomes in individuals with PD. The findings of the present preliminary study suggest that LSVT® BIG may not only improve motor outcomes but also have the potential to increase at-home PA in ADLs as measured using a triaxial accelerometer. However, this preliminary study has some limitations. First, it included a small cohort from a single center and was conducted using a retrospective, noncontrolled design, which, together with potential diary-reporting bias, may have reduced the generalizability and internal validity of the findings. Second, although significant improvements were observed after the LSVT® BIG intervention, the lack of a control group precluded definitive conclusions regarding its unique effects or direct comparisons with other exercise therapies for individuals with PD. Third, this study only evaluated PA within 2 weeks of the intervention, limiting conclusions about the long-term establishment of exercise habits.

Despite these limitations, the present findings provide preliminary evidence that LSVT® BIG may enhance at-home physical activity. Future studies involving larger, controlled, and long-term trials may help clarify whether the observed changes are sustained, identify patient subgroups who may benefit most, and determine whether increase in at-home PA may translate into meaningful improvements in independence, functional ability, and long-term quality of life.

6. Practical Implications

This study provides preliminary evidence that LSVT® BIG intervention can be implemented as a practical rehabilitation strategy to increase at-home PA in individuals with PD. By demonstrating reductions in SB and improvements in LPA within home environments, the findings suggest that LSVT® BIG may serve as an accessible, behavior-focused therapeutic approach to support daily mobility, enhance functional independence, and potentially inform future home-based or hybrid rehabilitation programs for PD.

7. Conclusions

LSVT® BIG may be an effective intervention for increasing at-home PA in individuals with PD. Specifically, LSVT® BIG significantly improved bradykinesia, decreased the time spent in SB (specifically rest), and increased the time spent in LPA (specifically, dressing and exercising). Future larger, controlled, and long-term follow-up studies may clarify whether the observed changes are sustained, which patient groups may benefit the most, and whether increase in at-home PA leads to meaningful improvements in function and long-term quality of life.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app152413235/s1, Figure S1: Changes in time spent in specific activity contents on three Physical activity intensities inside the home between before and after the intervention.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.H., H.S., K.T., S.K., M.I., I.M. and S.T.; methodology, Y.H., H.S., K.T., S.K., M.I., I.M. and S.T.; software, Y.H. and S.T.; validation, Y.H. and S.T.; formal analysis, Y.H., M.I. and S.T.; investigation, Y.H., M.I. and I.M.; resources, H.S., S.K., K.T., Y.K., M.K., N.K. and S.T.; data curation, Y.H. and S.T.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.H. and S.T.; writing—review and editing, H.S., K.T., S.K., M.I., I.M., Y.K., N.K., M.K. and S.T.; visualization, Y.H. and S.T.; supervision, H.S.; project administration, S.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Human Ethics Committee of Fujita Health University (approval number: HM22-198, approved on 21 September 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

The requirement for written informed consent was waived owing to the retrospective observational design. However, to provide participants with the opportunity to decline the use of their health records for the study, we posted study information with an opt-out option on our hospital’s bulletin board.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of the Department of Rehabilitation at Kawamura Hospital for their technical assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ADLs | Activities of daily living |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| HY | Hoehn and Yahr |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| LEDD | Levodopa equivalent daily dose |

| LPA | Light physical activity |

| LSVT® BIG | Lee Silverman Voice Treatment® BIG |

| METs | Metabolic equivalents |

| MDS-UPDRS | Movement Disorder Society-sponsored revision of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale |

| MMSE | Mini-Mental State Examination |

| MVPA | Moderate-to-vigorous physical activity |

| PA | Physical activity |

| PD | Parkinson’s disease |

| SB | Sedentary behavior |

References

- GBD 2016 Neurology Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of neurological disorders, 1990-2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019, 18, 459–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorsey, E.R.; Sherer, T.; Okun, M.S.; Bloem, B.R. The emerging evidence of the Parkinson pandemic. J. Parkinsons Dis. 2018, 8, S3–S8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marras, C.; Beck, J.C.; Bower, J.H.; Roberts, E.; Ritz, B.; Ross, G.W.; Abbott, R.D.; Savica, R.; VanDenEeden, S.K.; Willis, A.W.; et al. Parkinson’s Foundation P4 Group. Prevalence of Parkinson’s disease across North America. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 2018, 4, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, D.; Cui, Y.; He, C.; Yin, P.; Bai, R.; Zhu, J.; Lam, J.S.T.; Zhang, J.; Yan, R.; Zheng, X.; et al. Projections for prevalence of Parkinson’s disease and its driving factors in 195 countries and territories to 2050: Modelling study of Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. BMJ 2025, 388, e080952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, D.K.; Fahn, S.; Tatsuoka, C.; Kang, U.J. Hoehn and Yahr stage 3 and postural stability item in the movement disorder society-unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale. Mov. Disord. 2018, 33, 1188–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, M.D.; Brazier, D.E.; Henderson, E.J. Current perspectives on the assessment and management of gait disorders in Parkinson’s disease. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2021, 17, 2965–2985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhidayasiri, R.; Martinez-Martin, P.; Merello, M. Assistive technologies in Parkinson’s disease. In Handbook of Parkinson’s Disease, 5th ed.; Pahwa, R., Lyons, K., Koller, W.C., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Boonsinsukh, R.; Saengsirisuwan, V.; Carlson-Kuhta, P.; Horak, F.B. A cane improves postural recovery from an unpracticed slip during walking in people with Parkinson disease. Phys. Ther. 2012, 92, 1117–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jankovic, J. Parkinson’s disease: Clinical features and diagnosis. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2008, 79, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulisevsky, J. Pharmacological management of PD motor symptoms: Update and recommendations from an expert. Rev. Neurol. 2022, 75, S1–S10, (In English and Spanish). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalbe, E.; Folkerts, A.K.; Ophey, A.; Eggers, C.; Elben, S.; Dimenshteyn, K.; Sulzer, P.; Schulte, C.; Schmidt, N.; Schlenstedt, C.; et al. Enhancement of executive functions but not memory by multidomain group cognitive training in patients with Parkinson’s disease and mild cognitive impairment: A multicenter randomized controlled trial. Parkinsons Dis. 2020, 2020, 4068706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, Y.; Ohtsuka, H.; Kamata, N.; Yamamoto, S.; Sawada, M.; Nakamura, J.; Okamoto, M.; Narita, M.; Nikaido, Y.; Urakami, H.; et al. Effectiveness of long-term physiotherapy in Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Parkinsons Dis. 2021, 11, 1619–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohlhalter, S.; Kaegi, G. Parkinsonism: Heterogeneity of a common neurological syndrome. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2011, 141, w13293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoker, T.B.; Greenland, J.C. (Eds.) Parkinson’s Disease: Pathogenesis and Clinical Aspects; Codon Publications: Singapore, 2018. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK536721/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Hariz, G.M.; Forsgren, L. Activities of daily living and quality of life in persons with newly diagnosed Parkinson’s disease according to subtype of disease, and in comparison to healthy controls. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2011, 123, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovannoni, G.; van Schalkwyk, J.; Fritz, V.U.; Lees, A.J. Bradykinesia akinesia inco-ordination test (BRAIN TEST): An objective computerised assessment of upper limb motor function. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1999, 67, 624–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirakawa, Y.; Sakurai, H.; Takeda, K.; Koyama, S.; Iwai, M.; Motoya, I.; Kanada, Y.; Kawamura, N.; Kawamura, M.; Tanabe, S. Relationship between each of the four major motor symptoms and at-home physical activity in individuals with Parkinson’s disease: A cross-sectional study. Neurol. Int. 2025, 17, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, B.B.; Hergenroeder, A.L.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Lee, I.M.; Jakicic, J.M. Definition, measurement, and health risks associated with sedentary behavior. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2015, 47, 1295–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, C.K.; Morey, M.C.; Desmond, R.A.; Cohen, H.J.; Sloane, R.; Snyder, D.C.; Demark-Wahnefried, W. Light-intensity activity attenuates functional decline in older cancer survivors. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2014, 46, 1375–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacIntosh, B.R.; Murias, J.M.; Keir, D.A.; Weir, J.M. What Is Moderate to Vigorous Exercise Intensity? Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 682233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farley, B.G.; Koshland, G.F. Training BIG to move faster: The application of the speed-amplitude relation as a rehabilitation strategy for people with Parkinson’s disease. Exp. Brain Res. 2005, 167, 462–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebersbach, G.; Ebersbach, A.; Edler, D.; Kaufhold, O.; Kusch, M.; Kupsch, A.; Wissel, J. Comparing exercise in Parkinson’s disease--the Berlin LSVT®BIG study. Mov. Disord. 2010, 25, 1902–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, C.; Ebersbach, G.; Ramig, L.; Sapir, S. LSVT LOUD and LSVT BIG: Behavioral treatment programs for speech and body movement in Parkinson disease. Parkinsons Dis. 2012, 2012, 391946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farley, B.G.; Fox, C.M.; Ramig, L.O.; McFarland, D.H. Intensive amplitude-specific therapeutic approaches for Parkinson’s disease. Top Geriatr. Rehabil. 2008, 24, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwai, M.; Koyama, S.; Takeda, K.; Hirakawa, Y.; Motoya, I.; Sakurai, H.; Kanada, Y.; Okada, Y.; Kawamura, N.; Kawamura, M.; et al. Effect of Lee Silverman Voice Treatment® BIG on the major motor symptoms in persons with moderate Parkinson’s disease: An observational study. J. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2024, 72, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millage, B.; Vesey, E.; Finkelstein, M.; Anheluk, M. Effect on gait speed, balance, motor symptom rating, and quality of life in those with stage I Parkinson’s disease utilizing LSVT BIG®. Rehabil. Res. Pract. 2017, 2017, 9871070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssens, J.; Malfroid, K.; Nyffeler, T.; Bohlhalter, S.; Vanbellingen, T. Application of LSVT BIG intervention to address gait, balance, bed mobility, and dexterity in people with Parkinson disease: A case series. Phys. Ther. 2014, 94, 1014–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int. J. Surg. 2014, 12, 1495–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, A.L.; Julious, S.A.; Cooper, C.L.; Campbell, M.J. Estimating the sample size for a pilot randomised trial to minimise the overall trial sample size for the external pilot and main trial for a continuous outcome variable. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 2016, 2, 1057–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurlowicz, L.; Wallace, M. The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE). J. Gerontol. Nurs. 1999, 25, 8–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, C.L.; Stowe, R.; Patel, S.; Rick, C.; Gray, R.; Clarke, C.E. Systematic review of levodopa dose equivalency reporting in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2010, 25, 2649–2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoehn, M.M.; Yahr, M.D. Parkinsonism: Onset, progression and mortality. Neurology 1967, 17, 27–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goetz, C.G.; Tilley, B.C.; Shaftman, S.R.; Stebbins, G.T.; Fahn, S.; Martinez-Martin, P.; Poewe, W.; Sampaio, C.; Stern, M.B.; Dodel, R.; et al. Movement Disorder Society-sponsored revision of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS): Scale presentation and clinimetric testing results. Mov. Disord. 2008, 23, 2129–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, R.P.; Earhart, G.M. Randomized controlled trial of community-based dancing to modify disease progression in Parkinson disease. Neurorehabilit. Neural Repair 2012, 26, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramsay, N.; Macleod, A.D.; Alves, G.; Camacho, M.; Forsgren, L.; Lawson, R.A.; Maple-Grødem, J.; Tysnes, O.B.; Williams-Gray, C.H.; Yarnall, A.J.; et al. ParkWest Study: ParkWest Principal investigators; Study personnel; ICICLE-PD Study. Validation of a UPDRS-/MDS-UPDRS-based definition of functional dependency for Parkinson’s disease. Park. Relat. Disord. 2020, 76, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirakawa, Y.; Sakurai, H.; Takeda, K.; Koyama, S.; Iwai, M.; Motoya, I.; Kanada, Y.; Kawamura, N.; Kawamura, M.; Tanabe, S. Measurement of physical activity divided into inside and outside the home in people with Parkinson’s disease: A feasibility study. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2025, 31, e14251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagayoshi, S.; Oshima, Y.; Ando, T.; Aoyama, T.; Nakae, S.; Usui, C.; Kumagai, S.; Tanaka, S. Validity of estimating physical activity intensity using a triaxial accelerometer in healthy adults and older adults. BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med. 2019, 5, e000592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, H.; Kawakami, R.; Nakae, S.; Yamada, Y.; Nakata, Y.; Ohkawara, K.; Sasai, H.; Ishikawa-Takata, K.; Tanaka, S.; Miyachi, M. Accuracy of 12 wearable devices for estimating physical activity energy expenditure using a metabolic chamber and the doubly labeled water method: Validation study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2019, 7, e13938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Ishikawa-Takata, K.; Tanaka, S.; Mekata, Y.; Tabata, I. Effects of walking speed and step frequency on estimation of physical activity using accelerometers. J. Physiol. Anthropol. 2011, 30, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaki, K.; Fujioka, S.; Sasai, H.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Tsuboi, Y. Physical activity and its diurnal fluctuations vary by non-motor symptoms in patients with Parkinson’s disease: An exploratory study. Healthcare 2022, 1, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, J.E.; Júnior, J.H.; Meneguci, J.; Tribess, S.; Marocolo Júnior, M.; Stabelini Neto, A.; Virtuoso Júnior, J.S. Number of days required for reliably estimating physical activity and sedentary behaviour from accelerometer data in older adults. J. Sports Sci. 2018, 36, 1572–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, T.L.; Swartz, A.M.; Cashin, S.E.; Strath, S.J. How many days of monitoring predict physical activity and sedentary behaviour in older adults? Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2011, 8, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Troiano, R.P.; Berrigan, D.; Dodd, K.W.; Mâsse, L.C.; Tilert, T.; McDowell, M. Physical activity in the United States measured by accelerometer. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2008, 4, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, H.; Yokoi, D.; Kobayashi, R.; Okada, H.; Kajita, Y.; Okuda, S. The relationships between three-axis accelerometer measures of physical activity and motor symptoms in patients with Parkinson’s disease: A single-center pilot study. BMC Neurol. 2020, 2, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gershuny, J.; Harms, T.; Doherty, A.; Thomas, E.; Milton, K.; Kelly, P.; Foster, C. Testing self-report time-use diaries against objective instruments in real time. Sociol. Methodol. 2020, 5, 318–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Hillsdale, L., Ed.; Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Iwai, M.; Tanabe, S.; Koyama, S.; Takeda, K.; Hirakawa, Y.; Motoya, I.; Okuda, Y.; Kikuchi, Y.; Sakurai, H.; Kanada, Y.; et al. Clinical and biomechanical factors in the sit-to-stand decline in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pract. 2025, 12, 1539–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, M.S.; Kang, G.E.; Protas, E.J. Relation of chair rising ability to activities of daily living and physical activity in Parkinson’s disease. Arch Physiother. 2020, 10, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flood, M.W.; O’Callaghan, B.P.F.; Diamond, P.; Liegey, J.; Hughes, G.; Lowery, M.M. Quantitative clinical assessment of motor function during and following LSVT-BIG® therapy. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2020, 17, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, M.K.; Wong-Yu, I.S.; Shen, X.; Chung, C.L. Long-term effects of exercise and physical therapy in people with Parkinson disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2017, 13, 689–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrione, P.; Tranchita, E.; Sansone, P.; Parisi, A. Effects of physical activity in Parkinson’s disease: A new tool for rehabilitation. World J. Methodol. 2014, 4, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirakawa, Y.; Koyama, S.; Takeda, K.; Iwai, M.; Motoya, I.; Sakurai, H.; Kanada, Y.; Kawamura, N.; Kawamura, M.; Tanabe, S. Short-term effect and its retention of LSVT® BIG on QOL improvement: 1-year follow-up in a patient with Parkinson’s disease. Neuro Rehabil. 2021, 49, 501–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouça-Machado, R.; Rosário, A.; Caldeira, D.; Castro Caldas, A.; Guerreiro, D.; Venturelli, M.; Tinazzi, M.; Schena, F.; Ferreira, J. Physical activity, exercise, and physiotherapy in Parkinson’s disease: Defining the concepts. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pract. 2019, 7, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feil, K.; Allion, S.; Weyland, S.; Jekauc, D. A systematic review examining the relationship between habit and physical activity behavior in longitudinal studies. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 626750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lally, P.; Gardner, B. Promoting habit formation. Health Psychol. Rev. 2011, 7, S137–S158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).