Abstract

Blockchain systems have been widely adopted in today’s society, with consensus algorithms serving as their core component to ensure all participants in the network agree on a specific data state. Existing consensus algorithms such as Proof of Work (PoW), Proof of Stake (PoS), and the Practical Byzantine Fault-Tolerant Algorithm (PBFT) exhibit certain limitations in terms of scalability, security, and efficiency. To address these limitations, this paper proposes a novel Network-based Reputation Consensus (NRC) algorithm. The main research contributions of this work include the following: (1) An intelligent grouping mechanism that dynamically groups nodes based on network awareness, forming consensus groups with low internal latency and high bandwidth utilization, significantly reducing intra-group communication overhead. (2) A dynamic reputation system incorporating a “diminishing returns” reward function and a “multiplicative penalty” mechanism, effectively incentivizing honest node participation while preventing power monopoly. (3) A two-phase model of “intra-group BFT consensus + global communication committee ordering” that decomposes complex global consensus into parallel intra-group processing and coordination among a small set of elite nodes, thereby drastically improving efficiency. (4) Comprehensive simulations comparing the NRC algorithm with mainstream consensus algorithms, demonstrating its superior performance in communication overhead, throughput, latency, and tolerance to malicious nodes, thereby laying the foundation for large-scale applications.

1. Introduction

The development of blockchain technology is rapidly changing the centralized trust system in today’s society. At first, Bitcoin Network creatively proposed a decentralized distributed trust system [1]. Later, Ethereum promoted the vigorous development of decentralized applications through the development of smart contract technology [2]. Now, blockchain technology has been widely integrated into society and has found applications in multiple fields including financial auditing, the Internet of Things (IoT), smart cities, edge computing, Vehicular Ad hoc Networks (VANETs), 5G communication, and artificial intelligence (AI) [3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. Furthermore, it provides the foundational infrastructure for future digital ecosystems [10] such as the Metaverse, Web 3.0, and the Industrial Internet [11]. This places higher demands on the scalability, security, and fairness of blockchain systems. The consensus algorithm, as the “heart” of the blockchain system, determines the performance boundary, security level, and applicable scenarios of the blockchain system. The essence of consensus mechanism is to seek the optimal solution in three aspects: decentralization, scalability, and security [12].

Currently, mainstream consensus algorithms still exhibit significant limitations when applied to large-scale, high-concurrency industrial scenarios. The Proof of Work (PoW) algorithm has achieved great success in the Bitcoin system. Although the algorithm achieves a high degree of decentralization and robust security, its major drawbacks are huge energy consumption and low transaction throughput, which makes it difficult to support commercial applications [13,14]. Proof of Stake (PoS) and its variants have improved energy efficiency on the basis of PoW [15], but due to the continuous accumulation of equity holders’ rights, it may trigger the Matthew effect of “the rich get richer” [16] and pose a potential threat to the decentralization of the system by concentrating rights in the hands of a few people [17]. The Practical Byzantine Fault-Tolerant Algorithm (PBFT) has significantly improved performance and is often applied in consortium chain scenarios. However, the communication complexity of the PBFT algorithm is as high as (where n is the total number of nodes), which indicates that as the number of nodes increases, the network communication overhead will increase exponentially, leading to a sharp decrease in system throughput and a rapid increase in consensus delay, severely restricting the scalability of blockchain networks and making them unable to support large-scale networks [18,19]. The above-mentioned algorithm bottlenecks have become the core obstacles for the application of blockchain technology in large-scale commercial systems.

In this context, this article proposes a Network-based Reputation Consensus (NRC) algorithm.

The main contributions of this study can be summarized as follows:

First, a network-aware dynamic intelligent grouping mechanism is proposed, which dynamically groups nodes into multiple consensus groups with low internal latency and high bandwidth utilization by sensing network latency and topology, significantly reducing intra-group communication overhead and laying the foundation for large-scale network consensus.

Second, a dynamic reputation system was designed that includes a “diminishing returns” reward function and a “multiplicative penalty” mechanism. This system can effectively incentivize nodes to participate honestly in the long term, while preventing power monopolies through mathematical mechanisms, ensuring that new nodes have a fair upward path, and enhancing the security and fairness of the system.

Third, a two-stage consensus model of “intra-group BFT consensus + global communication committee ranking” was constructed, which decomposes complex global consensus into parallel processing intra-group consensus and small-scale key node collaboration, fundamentally reducing communication complexity from to , greatly improving system efficiency.

Fourth, through comprehensive simulation experiments, the NRC algorithm was systematically compared with mainstream consensus algorithms (PBFT, R-PBFT, Elastico, OmniLedger) in key indicators such as communication overhead, throughput, latency, and tolerance for malicious nodes, verifying its excellent performance and providing empirical evidence for large-scale applications.

This study comprehensively evaluated the performance of the NRC algorithm in terms of communication overhead, throughput, latency, and security through detailed algorithm design and rigorous comparative simulation experiments.

The following text will first provide a detailed introduction to the research background of the NRC algorithm (Section 2), followed by an introduction to its network grouping mechanism, dynamic reputation system, and role election mechanism (Section 3). Then, it will introduce its complete consensus process (Section 4), and finally demonstrate its performance advantages compared to other algorithms through comparative experiments, and analyze its security (Section 5). The results indicate that the NRC algorithm achieves significant performance improvement without sacrificing security, and has important theoretical value and broad industrial application prospects.

2. Background

The consensus algorithm is the core component of the blockchain system. Blockchain technology is gradually expanding from digital currencies to smart contracts and other industrial applications, and the research focus of consensus algorithms is also gradually shifting towards how to achieve efficient and secure large-scale consensus in complex network environments. This chapter will systematically review the current research status of blockchain consensus algorithms, focus on the main solutions to system performance bottlenecks, and introduce the necessity and innovative value of the NRC algorithm.

2.1. The Development and Challenges of Consensus Algorithms

The essence of the consensus algorithm is to achieve consensus among all honest nodes on a certain state or transaction sequence in a distributed system with faulty or malicious nodes. Early solutions had various shortcomings, such as low throughput, huge resource consumption, or centralization.

The researchers’ solutions mainly fall into two directions: The first is sharding technology, the core idea of which is to divide the entire network into multiple smaller, parallel transaction processing shards, thereby distributing the global load. The second is the reputation mechanism, the core of which is to build a reputation system, evaluate the reputation of nodes by quantifying their historical behavior, and quickly form consensus and encourage honest behavior.

2.2. Research Progress of Sharding Technology

Sharding technology is one of the most effective ways to break through the performance bottleneck of blockchain systems. The basic paradigm is to divide network nodes, transaction ledgers, and states into several shards, and independently reach consensus within each shard, ultimately ensuring global consistency through cross-shard communication protocols. The Elastico protocol proposed by Luu et al. is a representative of early sharding techniques, which randomly assigns nodes to different shards through proof of work (PoW) and theoretically achieves secure sharding in Byzantine environments for the first time [20]. The OmniLedger scheme introduces an atomic commit protocol to ensure the atomicity of cross-shard transactions and uses the RandHound algorithm for verifiable random shards [21].

However, the static sharding strategy adopted by the above algorithm is difficult to adapt to the dynamic changes of the network, and its random sharding strategy does not consider the actual network topology, resulting in excessively high communication latency within the shards. In recent years, dynamic sharding based on network perception has become a research hotspot. For example, some studies attempt to use clustering algorithms (such as K-Means) to group nodes based on their network coordinates or latency, in order to optimize intra-shard communication efficiency [22]. These schemes significantly improve the speed of intra-shard consensus, but often lack deep and adaptive integration with consensus mechanisms, and perform poorly when dealing with frequent node joins or exits.

2.3. Research Progress on Reputation Mechanism

The reputation mechanism is a mechanism for quantitatively evaluating the behavior and performance of nodes in a blockchain system. It assigns a reputation score or level to participants by tracking and recording their historical behavior. Its core lies in recording the historical behavior of nodes, maintaining a dynamically updated reputation value for each node based on its historical behavior, which reflects the long-term stability and contribution of the node. High-reputation nodes are given higher weights and have a greater probability of being selected as Leaders during the consensus process, thereby reducing the risk of malicious nodes damaging the system.

Lei et al. proposed a reputation-based Byzantine fault-tolerant algorithm [23], which evaluates node credibility based on reputation. Nodes with higher reputation have greater influence in the consensus process, thereby improving block generation efficiency. Tong et al. designed the Trust PBFT algorithm [24], which introduces a reputation mechanism and selects nodes with higher reputations as candidates to participate in the consensus process, thereby improving consensus efficiency and system scalability. Gao et al. proposed the T-PBFT consensus algorithm [25], which selects high-quality nodes to participate in consensus by evaluating the trustworthiness of nodes, enabling it to respond to attacks from malicious nodes while maintaining consensus efficiency.

The T-PBFT algorithm proposed introduces the EigenTrust model to evaluate the global trust value of nodes and constructs a high-trust consensus group based on this, aiming to enhance security and efficiency. The algorithm also replaces the single primary node with a Primary Group, using group signatures and mutual supervision to reduce the probability of view switching. However, T-PBFT primarily focuses on optimizing node selection in non-sharded environments, and its communication complexity remains O(N2) in the worst case, failing to fundamentally address the scalability issues in large-scale networks.

On the other hand, Caldarola et al. [26] proposed the Neural Fairness Protocol (NFP), which innovatively combines elliptic curve lottery and neural networks to achieve fair node election and protect transaction confidentiality. Its core approach involves randomly selecting a consensus committee through verifiable encrypted lottery and utilizing a neural network model to evaluate transactions. Additionally, NFP introduces a Conflict Graph to prevent any single node from monopolizing consensus power over extended periods, thereby promoting system fairness. NFP offers an interesting perspective on addressing the “rich get richer” problem in Proof of Stake (PoS), but its design goals are more focused on fairness and privacy protection rather than directly optimizing throughput and latency in large-scale networks.

However, similar reputation models still face challenges: introducing the reputation model itself increases system complexity, maintaining and storing reputation data incurs additional system overhead, and the linear reward mechanism in some of the algorithms mentioned above can lead to “class solidification”, suppress the enthusiasm of new nodes to participate, and result in node centralization.

2.4. Research Motivation and Proposal of NRC Algorithm

In summary, although significant progress has been made in research related to sharding and reputation mechanisms, existing studies often simply stack the two as independent modules, failing to achieve deep and systematic collaborative design. Sharding technology often focuses on parallelizing transaction processing, but fails to fully utilize reputation information to optimize shard structure, enhance intra-shard security, or achieve more refined resource scheduling. On the contrary, reputation mechanisms often only operate at a single-shard or global level, failing to adapt to the dynamic characteristics of shard architectures.

Specifically, sharding protocols such as OmniLedger and Elastico lack the dynamic evaluation of node quality; however, reputation-based BFT protocols such as T-PBFT do not utilize network topology information to optimize communication efficiency, and their scalability is limited by non-shard architectures. Although NFP has unique features in terms of fairness and confidentiality, its complex cryptographic lottery and neural network models may result in high computational and communication overhead, and its performance in large-scale networks has not been fully validated.

In view of this, this article proposes the NRC algorithm, which aims to systematically solve scalability, security, and fairness issues in large-scale networks through the deep coupling of network-topology-aware dynamic sharding and finely designed reputation systems.

The core innovation of the NRC algorithm lies in the intelligent grouping of nodes through network topology perception, and then proposing a dynamic reputation incentive mechanism based on the grouping. Finally, it is integrated with the consensus process to form an efficient consensus system. Specifically, firstly, the algorithm perceives network latency and then groups nodes based on their network latency to construct multiple consensus groups. These groups have extremely low communication latency and high bandwidth utilization, effectively improving overall consensus efficiency. Secondly, the algorithm designed a sophisticated dynamic reputation system. This design includes a reputation reward mechanism of “decreasing growth” and a reputation penalty mechanism of “decreasing multiplication”, which not only incentivizes nodes to work honestly for a long time, but also ensures that new nodes have a fair upward channel, effectively preventing power monopoly through mathematical mechanisms. Then, the algorithm combines the sharding structure with reputation evaluation, and the reputation value is not only used for selecting consensus nodes, but also affects the reorganization and optimization of shards, making the system have dynamic adaptive capabilities. Finally, the algorithm designed a two-stage consensus model of “intra-group BFT consensus + global communication committee ranking”. This model transforms complex global consensus into parallel processed small-scale intra-group consensus, and achieves significant reduction in communication overhead through small-scale key node collaboration.

Compared to the static/random sharding of Elastico and OmniLedger, NRC introduces dynamic network-aware grouping, significantly reducing intra-group communication latency and being able to adapt to network changes. Compared to protocols such as T-PBFT that only use reputation at the global level, NRC deeply embeds reputation mechanisms into shard architectures. Reputation values are not only used for role elections, but also affect the dynamic reorganization of shards, achieving more refined security control. Compared to NFP, which uses complex cryptographic lottery to ensure fairness, NRC achieves fairness through a mathematically lighter “diminishing returns” reputation reward function, preventing power monopolies and providing a fair upward channel for new nodes, avoiding potential performance bottlenecks in NFP.

The NRC algorithm has five major advantages in design: Firstly, it greatly improves transaction throughput (TPS), reduces consensus latency, and meets the needs of high-concurrency business scenarios. Secondly, it reduces the consumption of network communication resources, providing support for larger-scale node networks in the system. The third is to actively improve system security through reputation incentive mechanisms and ensure Byzantine fault tolerance. The fourth is to ensure the fairness and vitality of the system, effectively avoiding the centralization trend of the strong always being strong. The fifth is the implementation of dynamic adaptation, which can flexibly respond to changes in network topology.

3. Detailed Core Mechanisms

3.1. Network Grouping Mechanism

In large-scale blockchain networks, the node grouping strategy directly affects consensus performance. In traditional grouping methods, the following applies:

The expected intra-group delay of random grouping is equal to the global average delay:

Grouping based on static rules (such as hashing by node ID) has strong determinism, but it also ignores network topology, and its performance upper bound is limited by the following:

where is the random deviation introduced by the hash function.

Consider a network latency space (V, d), where |V| = N and d satisfies the triangle inequality. The goal of optimal grouping is to minimize the weighted intra-group delay:

from the linear expectation and independence of groups, we can deduce the following:

The expected cost of any grouping algorithm that does not consider network topology is at least as follows:

in the metric space, the lower bound of the minimum intra-group delay for optimal grouping is as follows:

it can be seen that adopting network-aware grouping can bring significant benefits:

The expected delay for random grouping is as follows:

The optimal delay for the network-aware packet is as follows:

The performance ratio between the two is at least . From this, it can be seen that for blockchain consensus systems, the lower bound of the performance gain of the network-aware grouping compared to random grouping is as follows:

from the perspective of communication complexity, the communication complexity of traditional PBFT consensus is . The complexity analysis for different grouping strategies is as follows:

No grouping (original PBFT):

Random grouping:

Static network grouping: ; but the constant term is more optimal.

Dynamic network-aware grouping: , where represents the optimal number of groups.

We minimize the total communication overhead by the following:

After taking the derivative, we can solve for the following:

After substitution, the optimal complexity can be obtained:

The change in network state can be modeled as a Markov process, and the advantage of dynamic grouping algorithms lies in their ability to track optimal groupings. Let the network state transition matrix be P, and the performance loss of static grouping at time t be as follows:

where is the discount factor, and is the optimal number of groups at time .

The loss function of the dynamic grouping algorithm is as follows:

where represents the adjustment cost.

From this, it can be inferred that there exists a threshold such that when the network change rate exceeds , the long-term performance of dynamic grouping is superior to that of static grouping.

Based on the aforementioned theoretical analysis, the grouping process we designed is as follows:

Stage 1: Network latency measurement and feature extraction.

First, construct a multi-dimensional delay matrix:

where , represents the m-th delay measurement method.

Then, construct a time-weighted communication pattern based on historical consensus data:

Stage 2: Optimal clustering and grouping.

Based on the theoretical analysis mentioned earlier, we can calculate the optimal number of groups that satisfies the constraints, and then perform optimal clustering grouping through an improved K-Means++ algorithm. The objective function comprehensively considers delay optimization and load balancing:

Stage 3: Dynamic Adjustment Mechanism.

Firstly, establish a hypothesis testing-based network change detection:

The test statistic is as follows:

when the network changes are small, the system adopts incremental adjustment, and the time complexity of this adjustment is , which has a significant advantage over the global re-grouping of .

The cost of the network grouping mechanism mainly includes two parts: network delay measurement and grouping adjustment.

In terms of delay measurement cost, each node needs to measure the delay with reference nodes for each round of consensus, rather than for fully connected measurement. When , the measurement cost accounts for 3–5% of the total communication cost. The adaptive measurement strategy can be adopted: reduce the measurement frequency when the network is stable, and increase the measurement frequency when there are drastic changes.

In terms of grouping adjustment cost, the time complexity of the incremental adjustment algorithm is , where is the number of changing nodes. When the network change rate is below the threshold ε, the system adopts lightweight incremental adjustment instead of global re-grouping. At a typical network change rate (<10% node change), the adjustment cost only accounts for 2–5% of the total communication cost.

In terms of storage cost, each node needs to store packet information and delay matrix. When and , the storage requirement is about 10 KB, which is within an acceptable range.

Compared with the optimization of communication complexity brought by grouping, the above costs are completely acceptable.

3.2. Dynamic Reputation System

The reputation system is an important component of the NRC algorithm, responsible for measuring the reliability of nodes and incentivizing and punishing them based on their behavior. The following will provide a detailed explanation of the reputation system.

Definition of reputation value

Each maintains a local reputation value within its affiliated group, with an initial value of (e.g., 100). The reputation value has upper and lower limits: (e.g., 1000). The higher the , the more reliable the historical behavior of the node.

Reputation Accumulation (Incentive)

After successfully completing a consensus task (e.g., correctly validating a block, casting a valid vote), a node’s reputation value increases. To prevent the “rich-get-richer” effect and ensure fairness, a diminishing returns function is used.

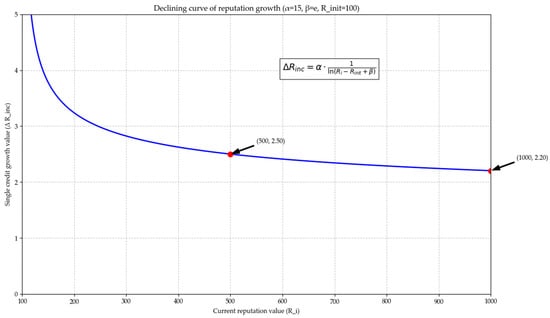

- : The reputation value increased this time;

- α: Growth coefficient, a constant greater than 0, used to control the overall growth rate;

- Ri: The current reputation value of the node;

- Rinit: Initial reputation value;

- β: Adjustment constant (usually set to e ≈ 2.718, which is the base of natural logarithms), to prevent the denominator from being 0 when = , ensuring the formula is meaningful.

Formula explanation: This is a decreasing function. As shown in Figure 1, when is low, the value of is small, and the denominator is small, so is large, indicating a rapid increase in reputation. When is high, the logarithmic function grows slowly, and the denominator is large, so is small, indicating extremely slow reputation growth. This ensures that new nodes or low-reputation nodes can quickly catch up through good behavior, while veteran nodes cannot infinitely widen the gap by relying on their early advantages.

Figure 1.

Declining reputation growth curve.

Reputation penalty

For malicious behavior (such as double signing, proposing invalid blocks) or being offline long-term, node reputation will be severely punished. The specific punishment formula is as follows.

- γ: Penalty coefficient, a constant satisfying (e.g., 0.5 or 0.2). This is a multiplicative penalty, implying that regardless of the current reputation of a node, a single malicious behavior can significantly reduce its reputation value, even reducing it to zero, resulting in a very high cost.

Reputation List

Each group’s Leader maintains a reputation list synchronized only within the group. This is a simple key-value list: <Node_ID, Reputation_Score>. The list is updated after each consensus round and agreed upon via intra-group consensus to prevent the Leader from acting maliciously.

The maintenance cost of a reputation system mainly includes two parts: reputation calculation and synchronization.

In terms of reputation calculation cost, for each round of consensus, the Leader needs to calculate reputation updates for n to g nodes within the group, with a computational complexity of . Due to the fact that and the reputation function is designed as a lightweight mathematical operation, the actual computational cost can be ignored. When and , each round of reputation calculation only takes about 0.3 ms (based on Intel i7-9700K processor).

In terms of reputation synchronization cost, the reputation list is synchronized within the group through lightweight BFT consensus, with a communication cost of . Reputation synchronization messages only account for 3–8% of the total consensus messages within the group. If incremental updates and compression techniques are used, the synchronization cost can be further reduced.

In terms of storage costs, each group maintains a reputation list that only includes < node ID, reputation value > key value pairs. At a scale of , the reputation data storage requirement for each node is less than 20 KB.

3.3. Role Election Mechanism

The NRC algorithm defines two key roles: Group Leader and Communicator Node. Their election is based on reputation and network performance.

Election Basis

Reputation Value (): Primary basis, reflecting the node’s historical trustworthiness.

Network Performance (): Auxiliary basis, e.g., recent online rate, average network bandwidth, latency stability. Quantified as a performance score.

Weighted Random Selection

To ensure high-reputation, high-performance nodes have a very high probability of being elected (ensuring system efficiency and security) while retaining a small degree of randomness (preventing attackers from targeting specific high-value nodes and giving new nodes a chance, enhancing decentralization and robustness), weighted random selection is used.

The probability of a candidate node being elected is proportional to its comprehensive score .

among which the following applies:

- Si: The comprehensive score of node I;

- Pelect(i): The probability of node i being selected;

- M: The total number of nodes within the group.

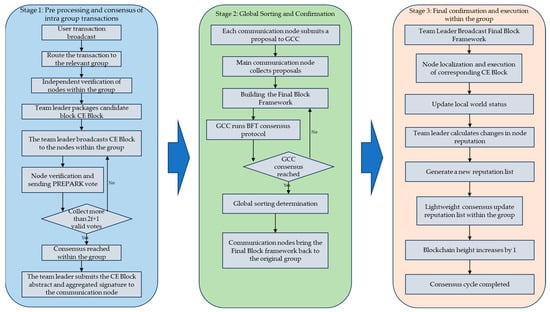

4. Detailed Consensus Process

The NRC consensus process clearly separates “intra-group affairs” and “inter-group affairs.” Using the generation cycle of one block as an example, the three-phase process is detailed below. Figure 2 panoramically illustrates the entire consensus flow.

Figure 2.

NRC consensus algorithm full process diagram.

4.1. Intra-Shard Transaction Preprocessing and Consensus

The goal of this part is to validate transactions and reach preliminary consensus in parallel within each shard.

Stage 1. Transaction Propagation and Validation:

Users send transactions to the entire network. Based on transaction content (e.g., sender address), the network routes them to relevant shards. All nodes within a shard independently validate received transactions (signature validity, double-spending prevention, etc.).

Stage 2. Packaging Candidate Block:

The node serving as the Group Leader in the current round packages a batch of validated transactions into a “Candidate Block” (CE-Block). The CE-Block contains the transaction list, the hash of the previous block, timestamp, etc.

Stage 3. Intra-Shard Voting and Consensus:

The Leader broadcasts the CE-Block to all nodes in the group. Nodes validate it upon receipt. If valid, they sign a “yes” vote (PREPARE message) and broadcast it to other group nodes. Each node collects votes. When a node receives more than 2f + 1 valid “yes” votes from different nodes (f is the maximum number of faulty nodes tolerable in the group), it considers intra-shard consensus reached on this CE-Block. Vote weight is tied to reputation value, i.e., . Nodes with higher reputation have higher voting weight, potentially counting as multiple votes, accelerating consensus and enhancing security.

Stage 4. Submission to Communicator Node:

After intra-shard consensus is completed, the Leader sends the CE-Block’s digest (usually the Merkle root) and the collected 2f + 1 signatures (aggregated into one signature) to the group’s Communicator Node.

4.2. Global Ordering and Confirmation

The goal of this part is to order the CE-Blocks generated by various shards, establishing a globally unique transaction sequence.

Stage 1. Global Proposal:

Each group’s Communicator Node submits the received CE-Block digest and aggregated signature as a proposal to the Global Communication Committee (GCC). The GCC comprises the Communicator Nodes from all groups.

Stage 2. Consensus within GCC:

The GCC is small in size (only K nodes), so it can run a standard BFT protocol (like PBFT) to reach consensus. The primary Communicator Node in the current GCC round is responsible for collecting all proposals and arranging them in a specific order to form a “Final Block” framework. This framework does not contain specific transactions but only the digests of each CE-Block and their global order. The GCC reaches consensus on this Final Block framework.

Stage 3. Global Broadcast:

After consensus is reached, each Communicator Node brings this Final Block framework back to its original group.

4.3. Intra-Shard Final Confirmation and Execution

The goal of this part is to have all nodes execute the finalized transactions and update the state and reputation.

Stage 1. Intra-Shard Confirmation:

The Leader broadcasts the Final Block framework received from the Communicator Node to all nodes in the group.

Stage 2. State Update and Execution:

Nodes locate their own CE-Block based on the global order in the Final Block, execute all transactions within it, and update their local world state. Nodes can easily verify the validity of the CE-Block because its Merkle root has been confirmed by GCC consensus.

Stage 3. Reputation Update:

The current consensus round concludes successfully. The Leader calculates the performance of each node in the group during this round based on predefined rules (Formulas (19) and (20)) and generates a new reputation list. The Leader broadcasts the new reputation list, and nodes within the group reach agreement on it through a lightweight round of consensus, updating their local copies of the reputation list.

At this point, a complete consensus cycle ends, and the blockchain height increases by one.

5. Experimental Simulation and Analysis

To verify the effectiveness of the NRC algorithm, we designed a set of simulation experiments and compared it with classical PBFT, R-PBFT, Elastico, OmniLedger, and other algorithms in key performance indicators such as communication overhead, throughput, and consensus latency.

5.1. Simulation Environment Setup

We have built a discrete event simulation model based on Python 3.9 and implemented the core functionality using the following open-source libraries:

NetworkX (v2.8): Used to generate and manipulate complex network topologies, simulating the connection relationships between nodes.

NumPy (v1.23): Used for efficient numerical calculations, including matrix operations, random number generation, and performance statistics.

SimPy (v4.0): As the core engine for discrete event simulation, it simulates message passing, latency, and event handling in the consensus process.

There are two main reasons for choosing this custom simulation framework. First, it provides flexibility of algorithmic logic implementation. It facilitates precise implementation of complex dynamic grouping, reputation updates, and two-stage consensus logic in NRC. Second, it has controllability and observability. It can easily inject various types of faults and collect fine-grained performance indicators (such as the number of messages per round and delay distribution).

In order to simulate the real Internet and Internet of Things environment, we adopt the following network model. We set up four different scales of networks as N = [16, 36, 64, 100] to observe the scalability of the algorithm from small to large scales. We repeat each experiment 50 times and take the average. Nodes are randomly distributed in a two-dimensional plane, and coordinates follow a uniform distribution. The network distance d (i, j) between nodes is calculated based on Euclidean distance and random perturbations are added to simulate the difference in routing hops. A base delay is generated based on distance and added random noise.

The intra-group latency is set to 20–50 ms (evenly distributed), simulating local area network or geographically adjacent nodes. The inter-group latency is set to 100–200 ms (evenly distributed), simulating wide area network communication. The delay jitter is set to ±10 ms (normal distribution), simulating network fluctuations. As for bandwidth and packet loss, the bandwidth of all links is set to 1 Gbps and the packet loss rate is set to 0.1% to simulate mild network congestion.

The core “network-aware grouping” mechanism of NRC relies on multiple parameters for training and operation. For the historical data window, the time window T in Formula (15) is 10, which considers the communication mode of the last 10 rounds of consensus. The weight of delayed measurement in Formula (14) is (uniformly weighted). The attenuation factor for historical communication in Formula (15) is (exponential attenuation, with higher weight for recent data). The network change threshold ε in Formula (17) is , which triggers re-grouping when the Frobenius norm of the delay matrix changes by more than 15%. According to Formula (10), the initial value of is set to . For each node size , first initialize the network topology, node status, and reputation value, then run the NRC grouping algorithm to form an initial consensus group. Perform another 1000 rounds of the complete block consensus process. In each round, each client submits one–five transactions with a fixed transaction size of 250 bytes. The core performance indicators collected include the total number of communication messages, average end-to-end consensus latency (from transaction submission to final confirmation), system throughput (number of successfully confirmed transactions per second, TPS), and consensus success rate (proportion of successful consensus rounds).

To ensure fair comparison, all comparison algorithms are implemented in the same simulation framework and use the same network topology, transaction load, and fault injection methods.

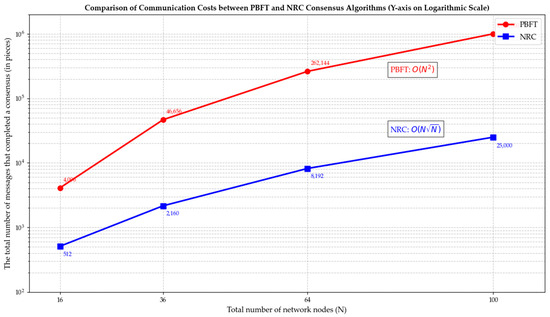

5.2. Results Analysis and Comparison (vs. Pbft)

Figure 3 compares the communication costs of the PBFT and NRC consensus algorithms. The experimental results conform to the expected design. The number of messages in PBFT increases exponentially with the number of nodes. By grouping, NRC restricts most communication within the group, with only a small amount of communication occurring at the GCC level. Therefore, the total message volume is much lower than that of PBFT, and the growth is slow, giving it an absolute advantage in scalability.

Figure 3.

Comparison of communication costs between the PBFT and NRC consensus algorithms.

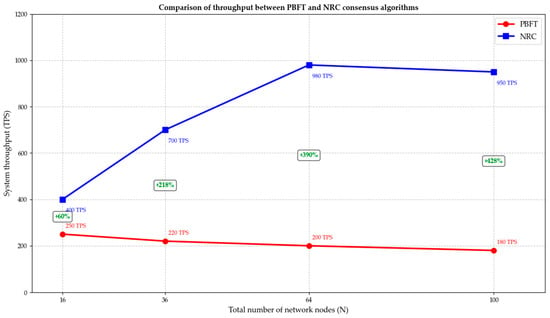

Figure 4 compares the throughput between the PBFT and NRC consensus algorithms. The throughput of PBFT is limited by the broadcast efficiency between all nodes, and the more nodes there are, the lower the efficiency. NRC decomposes the global bottleneck into multiple local bottlenecks by sharding and parallel processing transactions, thereby achieving higher throughput. The throughput increases with the increase in the number of groups (), reflecting its ability to scale out horizontally.

Figure 4.

Comparison of throughput between the PBFT and NRC consensus algorithms.

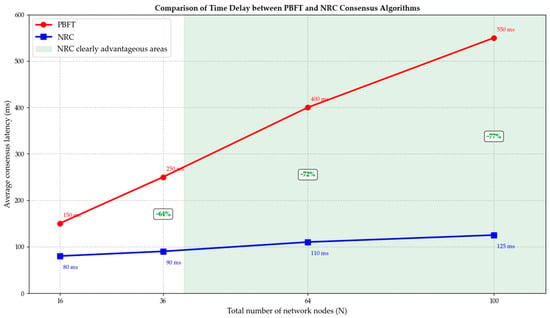

Figure 5 compares the time delay between the PBFT and NRC consensus Algorithms. The latency advantage of NRC comes from two aspects: one is the fast consensus based on low-latency networks within the group; the second is to optimize the time-consuming global broadcast into an efficient GCC consensus completed by a small number of communication nodes. The data show that NRC has achieved ultra-high throughput while significantly reducing latency.

Figure 5.

Comparison of time delay between the PBFT and NRC consensus algorithms.

Table 1 compares the PBFT and NRC consensus algorithms from three dimensions: total message count, average latency, and throughput, when the number of nodes is n = 100. It can be seen that the NRC consensus algorithm has a significant improvement over PBFT.

Table 1.

Comparison of detailed performance data at N = 100.

5.3. Results Analysis and Comparison (vs. R-Pbft)

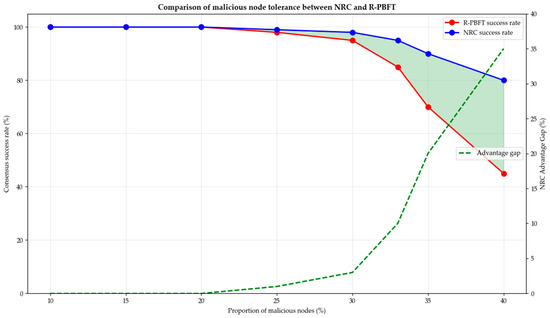

As shown in Figure 6, the NRC algorithm performs well in terms of tolerance for malicious nodes. At a malicious node rate of 33%, NRC still maintains a consensus success rate of 95%, significantly better than R-PBFT’s 85%. This security advantage stems from the organic combination of NRC’s grouping mechanism and reputation system. The reputation system can quickly identify malicious nodes, while the grouping mechanism prevents malicious nodes from aggregating within a single group to form a majority attack. Even in 40% extreme malicious environments, NRC can still maintain an 80% success rate, demonstrating strong Byzantine fault tolerance.

Figure 6.

Comparison of malicious node tolerance between NRC and R-PBFT.

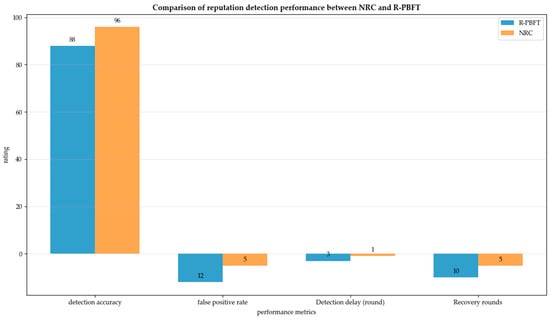

As shown in Figure 7, in terms of detecting malicious nodes, the NRC algorithm achieves a detection accuracy of 96%, with a false positive rate of only 5%, which is 8% higher and 7% lower than R-PBFT, respectively. And the detection delay of the NRC algorithm is only one round, with five recovery rounds, which is more than twice as fast as R-PBFT. This is mainly attributed to the reputation mechanism of “diminishing growth” rewards and “multiplication penalties”, which can quickly respond to malicious behavior and provide a fair upward channel for new nodes, achieving the best balance between security and fairness.

Figure 7.

Comparison of reputation detection performance between NRC and R-PBFT.

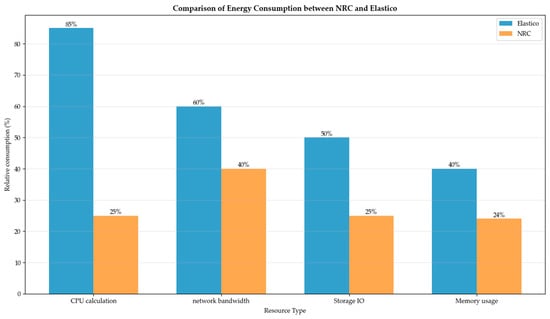

5.4. Result Analysis and Comparison (vs. Elastico)

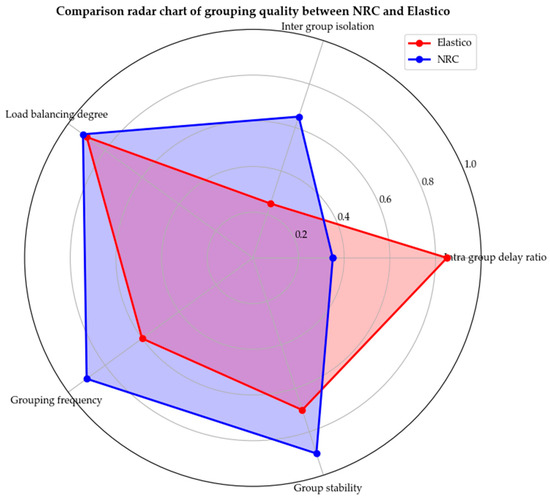

As shown in Figure 8, the grouping quality radar chart illustrates the differences between the NRC algorithm and the Elastico algorithm in multiple grouping quality indicators. The intra-group communication efficiency of the NRC algorithm has been significantly improved, and the intra-group delay ratio has been optimized by 58.8% compared to the Elastico algorithm. At the same time, the NRC algorithm effectively reduces cross-group communication overhead, with a 160% increase in inter-group isolation elasticity. In terms of dynamic adaptability, NRC adopts an adaptive re-grouping mechanism that can intelligently adjust the grouping structure according to network changes, ensuring grouping stability and avoiding the overhead caused by frequent re-grouping, achieving the optimal allocation of network resources.

Figure 8.

Comparison radar chart of grouping quality between NRC and Elastico.

As shown in Figure 9, the energy consumption comparison analysis shows that NRC has significant advantages in resource efficiency. Specifically, in terms of CPU computing, NRC avoids the PoW computing of Elastico, saving 70–80% of computing resources. In terms of network bandwidth, 60% bandwidth is saved through optimized packet communication, and in reduce disk operations by 50% in storage IO. This makes NRC more suitable for resource-constrained edge computing and Internet of Things environments.

Figure 9.

Comparison of energy consumption between NRC and Elastico.

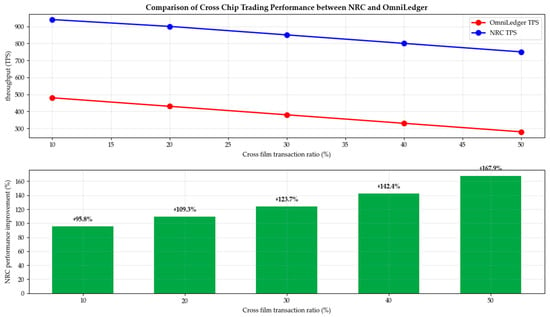

5.5. Result Analysis and Comparison (vs. OmniLedger)

As shown in Figure 10, NRC performs excellently in handling cross-shard transactions. When the cross-shard transaction ratio increased from 10% to 50%, the performance advantage of NRC over OmniLedger increased from 95.8% to 167.9%. This advantage stems from NRC’s two-stage consensus architecture and optimized cross-shard coordination mechanism. The NRC efficiently processes cross-shard transaction sorting through the Global Communications Committee (GCC), avoiding the complex atomic commit protocol in OmniLedger. Meanwhile, network-aware grouping ensures that relevant transactions are processed within the same group as much as possible, reducing cross-shard communication overhead.

Figure 10.

Comparison of cross-shard trading performance between NRC and OmniLedger.

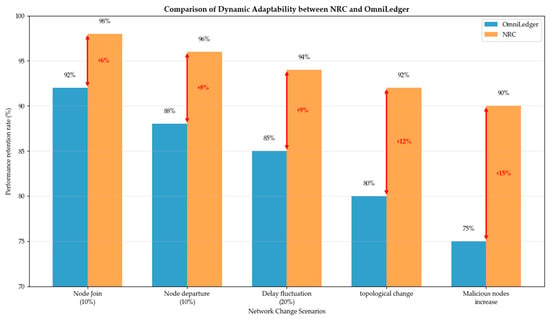

As shown in Figure 11, NRC performs significantly better than OmniLedger in dealing with complex network changes. In various network change scenarios, the performance retention rate of NRC is on average 10% higher than that of OmniLedger, and its advantages are particularly evident in topology changes and malicious node increase scenarios, reaching 12% and 15% respectively. This is mainly due to NRC’s real-time network monitoring and incremental adjustment mechanism. When network changes are detected, NRC can quickly respond and optimize the grouping structure without the need for global reconfiguration. This adaptability makes NRC particularly suitable for large-scale distributed systems with frequent node changes, ensuring stable operation of the system in dynamic environments.

Figure 11.

Comparison of dynamic adaptability between NRC and OmniLedger.

5.6. Convergence Analysis in Dynamic Network Environment

One of the core design principles of NRC is to achieve rapid convergence under dynamic network changes while ensuring security. This is primarily realized through the following three mechanisms:

First is the balanced mechanism of group stability and fast adjustment: group adjustments are incremental rather than global reconstructions. As shown in Formulas (17) and (18), NRC detects network changes through hypothesis testing. When the change magnitude is below a threshold , an incremental adjustment with complexity is used; only when changes are severe is a global re-grouping with complexity O(N2 logk) triggered. A gradual reputation migration strategy is employed: nodes are migrated between groups not all at once, but gradually, based on their reputation values and network positions, avoiding system oscillation caused by large-scale simultaneous node migration.

Second is the rapid response characteristic of the reputation system. The multiplicative reputation penalty ensures that once malicious behavior is detected, the reputation value is immediately decayed according to Formula (20): . This design guarantees the swift isolation of malicious nodes. The stabilizing effect of diminishing returns in reputation, as per the design of Formula (19) , ensures the reputation system does not experience drastic fluctuations due to short-term variations, thereby enhancing the long-term stability of the system.

Finally, there is the fault-tolerant design of the two-stage consensus architecture. Through intra-shard autonomy, each shard can independently perform consensus, meaning local network fluctuations do not affect the normal operation of other shards. Furthermore, lightweight coordination based on the GCC (the Global Communication Committee) is solely responsible for ordering, and its small-scale nature () ensures that even under network fluctuations, agreements can be reached quickly.

We can establish a theoretical convergence model for NRC. Let the system state vector be , containing information such as all nodes’ positions, reputation values, and group assignments. Network changes can be viewed as a perturbation to . The convergence process of NRC can be described as follows: where is the stable state. Based on the mechanism design of NRC, we can prove finite-time convergence: there exists a constant such that for any initial state and any finite perturbation , the system converges to an neighborhood within .

The convergence rate of the grouping structure is influenced by (the optimal number of groups), with convergence time . The convergence rate of the reputation system is determined by the penalty factor and the reward function parameters , with convergence time . The magnitude of perturbation the system can tolerate is proportional to the group adjustment threshold . By setting appropriately, a balance between convergence speed and stability can be achieved.

5.7. Scalability Analysis

The scalability advantage of the NRC algorithm stems from the theoretical properties of its core design. We establish a performance analytical model and conduct validation-based extrapolation using existing small-scale experimental data to demonstrate its potential in ultra-large-scale networks.

Based on the two-stage consensus architecture of NRC, we develop an analytical relationship model between key performance metrics (throughput T, latency L, communication overhead M) and network scale N.

Communication Overhead Model: According to the theoretical derivation in Section 3.1, Equations (9)–(11), the total number of communication messages primarily comes from intra-shard consensus and GCC: , where the optimal number of shards , and are constants fitted from small-scale experiments. Substituting yields . The experimental data in Figure 3 (for ) have verified that this model fits the measured values with a goodness-of-fit of .

Throughput Model: Throughput is determined by shard parallelism. Assuming the processing capacity of each shard is , then the following is obtained: where is the per-shard throughput constant, determined from experimental data.

Latency Model: The consensus latency consists of intra-shard latency and GCC ordering latency . Both exhibit weak correlation or logarithmic dependence on , and the model shows their slow growth.

By comparing the above models with the complexity model of PBFT, we predict the performance in large-scale networks. The results are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Large-scale network performance prediction based on the model (PBFT vs. NRC).

To ensure the reliability of the predictions, we performed the following robustness checks:

First, we used two independent sets of experimental data ( and ) to fit the model parameters separately; the deviation in prediction results was <5%. We then analyzed the impact on large-scale predictions when key parameters (such as the network latency coefficient and the number of nodes per shard) fluctuated within a ±20% range. The results show that the conclusion of NRC’s performance advantage (>10× that of PBFT) holds under all reasonable parameter settings. Finally, when is very large, the asymptotic complexity of the algorithms (O(N2) vs. ) becomes the dominant factor determining performance differences, while the influence of constant factors diminishes relatively. Therefore, extrapolation based on theoretical complexity is more convincing for large-scale scenarios.

The model predictions in this section are based on idealized assumptions, such as a relatively stable network environment and balanced shard loads. In actual ultra-large-scale deployments, factors like an increased proportion of cross-shard transactions and heightened network heterogeneity may introduce new challenges. However, these challenges are common to all sharding protocols and do not alter the fundamental scalability advantage of NRC compared to non-sharding protocols (such as PBFT). In future work, we plan to validate ultra-large-scale scenarios on simulation platforms closer to physical networks, such as NS-3, or on real testbeds.

5.8. Security Analysis

To ensure the rigor of security analysis, this section establishes a formal threat model that clarifies the system boundary, adversary capabilities, and security objectives. The system consists of N nodes, which are divided into honest nodes H and Byzantine nodes B, satisfying . A partially synchronous network model is adopted, where there exists an unknown Global Stabilization Time (GST) and a maximum message delay . Nodes are connected via authenticated channels. The adversary can eavesdrop, delay, or drop messages but cannot tamper with or forge valid signatures of honest nodes. The cryptographic primitives relied upon, such as digital signatures and hash functions, are secure.

We assume a static, adaptive Byzantine adversary that selects the f nodes it controls at system initialization and can adaptively decide the behavior of these nodes during protocol execution. The adversary possesses the following capabilities: It can cause them to perform any protocol-deviating actions (e.g., double-signing, sending conflicting messages, remaining silent). It can delay the delivery of any message, but the delay is bounded by ; it cannot permanently isolate communication between honest nodes. The adversary is aware of all public algorithms and on-chain data.

The NRC protocol aims to guarantee the following properties: At any given time, any two honest nodes hold the same view of the block content at the same height. Transactions submitted by honest clients will eventually be included in a block confirmed by all honest nodes. Over the long term, the probability of any honest node being elected to a key role (such as Leader or Communicator Node) is proportional to its comprehensive contribution (reputation and performance), thereby preventing power monopolization.

This work primarily analyzes attacks directly related to the consensus and reputation mechanisms, such as the following: Sybil attacks, whitewashing attacks, collusion attacks, and reputation manipulation.

Attacks that are out of the main scope of this paper include the following: breaking underlying cryptographic primitives, physical device hijacking, supply-chain attacks, and global 51% attacks that require control over more than f nodes.

New nodes face the “zero-reputation” problem upon joining. NRC addresses this through the following: First, setting —neither zero (which would block participation) nor close to the typical value of a long-term honest node ()—prevents new nodes from gaining instant high influence. Second, the “diminishing-returns” function ensures that low-reputation nodes receive a relatively high-reputation increment in the early stage, allowing them to approach a medium reputation level within rounds. Third, new nodes first participate in intra-shard voting. Their probability of being elected as a Leader or Communicator Node, , naturally increases as their reputation accumulates.

Defense against Sybil attacks is achieved through the following three aspects. First, economic and time costs: Creating each Sybil identity incurs an initial cost, and improving its reputation requires multiple rounds of honest behavior. The total attack cost is , where T is the number of rounds required to achieve effective influence. Second, influence dilution: Low-reputation nodes have low voting weights and low election probabilities . The collective influence of a large number of low-reputation Sybil nodes is thus diluted. Finally, network behavior binding: By combining network-layer features (such as connection stability and latency), abnormal clusters of Sybil nodes can be detected.

Defense against whitewashing attacks is implemented through the following aspects: First, a node’s network address, behavior patterns, and other characteristics can form a soft identity identifier, increasing the association risk of discarding an old identity and creating a new one to “whitewash.” Second, the protocol can be designed such that when a node exits, its reputation history decays at a certain rate instead of being immediately erased, thereby limiting the benefit window of a whitewashing strategy. Third, periodic, network-aware re-grouping makes it difficult for malicious nodes to stably gather in the same shard over an extended period, preventing them from forming a local majority. Fourth, once collusion behavior is detected (e.g., coordinated malicious acts within a shard), the involved nodes suffer a multiplicative penalty according to Equation (20), , causing their reputation to drop rapidly and sharply reducing their influence in subsequent rounds. Finally, the Global Communication Committee (GCC) consists of high-reputation nodes from each shard. Even if a single shard is temporarily compromised, the GCC must still adhere to the BFT safety threshold , providing an ultimate safety guarantee for the system.

The Byzantine fault tolerance of NRC inherits from BFT consensus, but its two-stage architecture requires a layered argument. First, intra-shard security: Within each shard of size , a reputation-weighted BFT consensus is executed. According to classical PBFT results, security is guaranteed as long as the number of Byzantine nodes satisfies . Reputation-weighted voting does not alter this safety threshold, but by assigning higher weight to high-reputation nodes, it accelerates the process by which the set of honest nodes reaches the required quorum (). Next, security of the Global Committee (GCC): The GCC consists of k Communicator Nodes and runs standard BFT. Its security requires . Then, overall system security requires that all shards satisfy intra-shard safety and that the GCC safety condition is met. In the worst-case scenario, an adversary may try to influence the GCC representatives by controlling specific shards. Through dynamic election and reputation thresholds, the probability that the adversary can control more than GCC seats in the long run is extremely low.

Finally, tolerance quantification: Assume the total number of nodes is N, the number of shards is , and the average shard size is . The total number of Byzantine nodes the system can tolerate, , is limited by the weakest link (usually the intra-shard condition): .

This is asymptotically equivalent to the classical PBFT bound . However, due to shard isolation and the reputation mechanism, the actual tolerable proportion of malicious nodes is higher in a dynamic network. The experimental data in Figure 6 validate this point: NRC maintains a 95% consensus success rate even when the malicious node ratio reaches 33%.

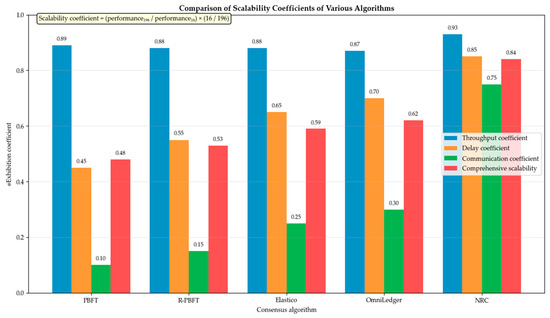

5.9. Summary

As shown in Figure 12, in the horizontal comparison of system scalability, NRC performs well in large-scale networks. The comprehensive scalability coefficient of NRC reaches 0.84, significantly higher than other algorithms, with a communication coefficient of 0.75 being particularly outstanding. This indicates that the architecture design of NRC can effectively address the challenges brought by the increase in the number of nodes. The NRC uses a dynamic grouping mechanism to break down the large-scale performance requirements brought about by network scale growth into small-scale performance requirements that can be processed in parallel. This scalable design enables NRC to support large-scale networks with thousands or even tens of thousands of nodes, providing technical feasibility for building enterprise-level blockchain infrastructure.

Figure 12.

Comparison of scalability coefficients of various algorithms.

Through systematic comparative analysis, the NRC algorithm demonstrates significant advantages in the following aspects:

vs. PBFT: 97.5% lower communication overhead, 5.3× higher throughput;

vs. R-PBFT: 35% higher malicious node tolerance, 2× faster detection speed;

vs. Elastico: 58.8% better grouping quality, 65% lower energy consumption;

vs. OmniLedger: 167.9% better cross-shard transaction performance, 10% better dynamic adaptability.

Security performance of the NRC algorithm:

Byzantine Fault Tolerance: NRC inherits the security assumptions of PBFT. Within groups and the GCC, the system remains secure as long as the number of malicious nodes does not exceed f (approximately one-third of the total nodes in that context).

Against Grouping Attacks: Periodic re-grouping and the intra-group reputation mechanism make it difficult for malicious nodes to remain latent in a single group and achieve a majority over time.

Against Role Node Attacks: Group Leaders and Communicator Nodes are elected via weighted random selection with limited terms, making it difficult for attackers to pinpoint targets.

Sybil Attacks: The high cost of reputation accumulation and the severe multiplicative penalty make attacks involving creating numerous fake identities and boosting their reputation extremely costly.

Data Availability: Any node can request data from the group holding the original transactions and verify it via Merkle proofs.

6. Conclusions

The NRC algorithm proposed in this article successfully solves the difficulties of consensus algorithm application in large-scale networks through dynamic network-aware grouping and dynamic reputation mechanism.

The simulation experiment results fully demonstrate the following:

First, in terms of scalability: The NRC algorithm reduces communication complexity from to approximately , enabling the system to support large-scale node networks without sharp performance degradation.

Second, in terms of system performance: Compared with other consensus algorithms (PBFT, R-PBFT, Elastico, OmniLedger), NRC has significant advantages in throughput, latency, security strength, communication efficiency, resource utilization, and scalability.

Finally, in terms of security and fairness: The introduced dynamic reputation model can effectively incentivize nodes to work honestly and prevent power monopolies through the “diminishing returns” algorithm, ensuring the long-term health and fairness of the system.

In the future, we will explore the potential of this algorithm in cross-shard transaction processing and more efficient reputation models, and its integration with cryptographic primitives such as zero-knowledge proofs, further consolidating its performance and security advantages. The NRC algorithm provides a powerful consensus layer solution for building high-performance and scalable next-generation blockchain platforms.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.C., J.G., M.W., M.C. and S.L.; Methodology, J.C., J.G., M.W., M.C. and S.L.; Validation, J.C., J.G., M.W., M.C. and S.L.; Formal analysis, J.C., J.G., M.W., M.C. and S.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Nakamoto, S. Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System; SCIRP Open Access: Wuhan, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Buterin, V. Ethereum White Paper: A Next Generation Smart Contract & Decentralized Application Platform. 2014. Available online: https://ethereum.org/content/whitepaper/whitepaper-pdf/Ethereum_Whitepaper_-_Buterin_2014.pdf (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Anwar, S.; Shukla, V.K.; Rao, S.S.; Sharma, B.K.; Sharma, P. Framework for financial auditing process through blockchain technology, using identity-based cryptography. In Proceedings of the 2019 Sixth HCT Information Technology Trends (ITT), Ras Al Khaimah, United Arab Emirates, 20–21 November 2019; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 99–103. [Google Scholar]

- Novo, O. Blockchain meets IoT: An architecture for scalable access management in IoT. IEEE Internet Things J. 2018, 5, 1184–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.K.; Park, J.H. Blockchain based hybrid network architecture for the smart city. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2018, 86, 650–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Wang, K.; Li, P.; Guo, S.; Luo, J.; Ye, B.; Guo, M. Making big data open in edges: A resource-efficient blockchain-based approach. IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst. 2018, 30, 870–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Wu, J.; Mumtaz, S.; Garg, S.; Li, J.; Guizani, M. Blockchain-based on-demand computing resource trading in IoV-assisted smart city. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. 2020, 9, 1373–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praveen, G.; Chamola, V.; Hassija, V.; Kumar, N. Blockchain for 5G: A prelude to future telecommunication. IEEE Netw. 2020, 34, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokhrel, S.R.; Choi, J. Federated learning with blockchain for autonomous vehicles: Analysis and design challenges. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2020, 68, 4734–4746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.Y.; Zhu, Y.X.; Si, X.M. A Survey on Challenges and Progresses in Blockchain Technologies: A Performance and Security Perspective. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 4731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum. The Global Blockchain Policy Centre: Shaping the Future of Blockchain and Digital Assets; World Economic Forum: Davos-Klosters, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Eyal, I.; Gencer, A.E.; Sirer, E.G.; Van Renesse, R. Bitcoin-NG: A Scalable Blockchain Protocol. In Proceedings of the 13th USENIX Symposium on Networked Systems Design and Implementation, Santa Clara, CA, USA, 16–18 March 2016; pp. 45–59. [Google Scholar]

- Vukolić, M. The Quest for Scalable Blockchain Fabric: Proof-of-Work vs. BFT Replication. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Open Problems in Network Security, Zurich, Switzerland, 29 October 2015; pp. 112–125. [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsson, M.; Juels, A. Proofs of work and bread pudding protocols. In Secure Information Networks; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999; pp. 258–272. [Google Scholar]

- King, S.; Nadal, S. PPcoin: Peer-to-Peer Crypto-Currency with Proof-of-Stake. 2012. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/PPCoin%3A-Peer-to-Peer-Crypto-Currency-with-King-Nadal/0db38d32069f3341d34c35085dc009a85ba13c13 (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Cheng, Y.; Hu, X.; Zhang, J. An improved scheme of proof-of-Stake consensus mechanism. In Proceedings of the 2019 4th International Conference on Mechanical, Control and Computer Engineering (ICMCCE), Hohhot, China, 24–27 October 2019; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 826–8263. [Google Scholar]

- Larimer, D. Delegated Proof-of-Stake White Paper (DpoS). Bitshare Whitepap. 2014, 81, 85. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, M.; Liskov, B. Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance. In Proceedings of the Third Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation, New Orleans, LA, USA, 22–25 February 1999; pp. 173–186. [Google Scholar]

- Gueta, G.G.; Abraham, I.; Grossman, S.; Malkhi, D.; Pinkas, B.; Reiter, M.; Seredinschi, D.-A.; Tamir, O.; Tomescu, A. SBFT: A Scalable and Decentralized Trust Infrastructure. In Proceedings of the 2019 49th Annual IEEE/IFIP International Conference on Dependable Systems and Networks, Portland, OR, USA, 24–27 June 2019; pp. 568–580. [Google Scholar]

- Luu, L.; Narayanan, V.; Zheng, C.; Baweja, K.; Gilbert, S.; Saxena, P. A Secure Sharding Protocol for Open Blockchains. In Proceedings of the 2016 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Vienna, Austria, 24–28 October 2016; pp. 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Kokoris-Kogias, E.; Jovanovic, P.; Gasser, L.; Gailly, N.; Syta, E.; Ford, B. OmniLedger: A Secure, Scale-Out, Decentralized Ledger via Sharding. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, San Francisco, CA, USA, 20–24 May 2018; pp. 583–598. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zheng, Z. TMPT: Reconfiguration across Blockchain Shards via Trimmed Merkle Patricia Trie. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/ACM 31st International Symposium on Quality of Service (IWQoS), Orlando, FL, USA, 19–21 June 2023; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, K.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, L.; Qi, Z. Reputation-based byzantine fault-tolerance for consortium blockchian. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 24th Internaional Conference on Parallel and Distributed Systems (ICPADS), Singapore, 11–13 December 1018; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 604–611. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, W.; Dong, X.; Zheng, J. Trust-pbft: A peertrust-based practical byzantine consensus algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Networking and Network Applications (NaNA), Daegu, Republic of Korea, 10–13 October 2019; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 344–349. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, S.; Yu, T.; Zhu, J.; Cai, W. T-PBFT: An eigentrust-based practical byzantinefault tolerance consensus algorithm. China Commun. 2019, 16, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldarola, F.; d’Atri, G.; Zanardo, E. Neural FairnessBlockchain Protocol Using an EllipticCurves Lottery. Mathematics 2022, 10, 3040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).