Abstract

A sustainable pathway for converting low-value solid waste (Coal gangue, CG) into high-performance thermal insulation materials through a green synthesis strategy has been demonstrated. The SiO2 was successfully and efficiently extracted from CG in the form of sodium silicate. The subsequent sol–gel process of sodium silicate solution utilized an innovative CO2 carbonation method, which replaced the conventional use of strong acids, thereby reducing the carbon footprint and enhancing process safety. Hydrophobic SiO2 aerogel was subsequently prepared via ambient pressure drying, exhibiting a high specific surface area of 750.4 m2/g, a narrow pore size distribution ranging from 2 to 15 nm and a low thermal conductivity of 0.022 W·m−1·K−1. Furthermore, the powdered aerogel was shaped into a monolithic form using a simple molding technique, which conferred appreciable compressibility and resilience, maintaining the low thermal conductivity and hydrophobicity of the original aerogels, ensuring its functional integrity for practical applications. Practical thermal management tests including low and high temperature, conclusively demonstrated the superior performance of the prepared aerogel material. This work presents a viable and efficient waste-to-resource pathway for producing high-performance thermal insulation materials.

1. Introduction

Excellent properties have been observed in silica aerogel in years of research, including low density (~0.01 g/cm3) [1], high porosity (~95%) [2], and high specific surface area (≥800 m2/g) [3]. It is an excellent lightweight thermal insulation material with low thermal conductivity (≤0.013 W∙m−1∙K−1) [4] in the field of thermal insulation. Moreover, compared with commonly used organic foam insulation and asbestos materials, SiO2 has the characteristics of non-toxic, non-burning, and long life [5]. However, aerogels are significantly hindered by manufacturing costs, including raw material costs for silicon precursors and production costs associated with drying. Traditional drying uses supercritical, and the drying medium includes alcohol and CO2 [6]. The surface tension at the gas–liquid interface can be eliminated by supercritical state under high pressure, which can avoid the collapse and contraction of the aerogel skeleton. The produced aerogel has excellent performance, but it is difficult to promote large-scale production and poses safety risks. In contrast, ambient pressure drying (APD) has emerged as a more practical and scalable alternative, significantly reducing both equipment costs and operational hazards [7]. Traditional silica precursors such as methyl orthosilicate and ethyl orthosilicate are costly. Taken together, the cost of aerogel insulation products is much more expensive than other insulation materials, and silicone premises and supercritical processes contain high energy consumption. Previous studies have shown that the use of sodium silicate precursors is less costly and less toxic compared to organic silicon [8]. Combined with the atmospheric pressure drying process, will open the door to large-scale low-cost production of aerogel products. Further, sodium silicate can be extracted from solid waste.

Coal gangue (CG), a solid waste generated during coal mining, washing, and processing, usually constitutes 10–15% of the total raw coal output [9]. It has been reported that the stockpile in China exceeded 5 billion tons and grew by 350 million tons annually [10,11]. An endless stream of CG will be associated with coal usage as an indispensable energy source for a long time, impacting environmental safety and human health. In terms of minerals, CG primarily consists of carbonaceous shale, clay minerals, sandstone, and residual coal [12,13]. In terms of elements, CG mainly contains silicon, aluminum, and small amounts of calcium, iron, and magnesium, and also includes sulfides and heavy metals (e.g., lead, cadmium, mercury) [14,15,16]. Characterized by high ash content, low calorific value, and a dense structure, coal gangue accumulates in large quantities, leading to land occupation, soil salinization, water contamination, airborne dust, and hazards related to spontaneous combustion [17,18,19]. These issues threaten ecosystems and human health, particularly in mining-intensive regions. Currently, CG recycling is applied in many ways, such as adsorbent materials for environmental remediation, lightweight aggregates for concrete, water retention and slow-release fertilizers for agricultural production, as well as the recycling and extraction of valuable elements [20,21,22,23,24]. However, the recycling of CG faces significant challenges, including its heterogeneous composition, low chemical reactivity, and high processing costs, which often drive reliance on low-cost but environmentally detrimental practices such as landfills. Consequently, the accumulation of CG waste continues to rise, with secondary pollution risks (e.g., heavy metal leaching, dust emissions) persisting during processing. To address these issues, transforming CG into high-value products is critical to enhancing recycling efficiency, reducing environmental impacts, and fostering sustainable resource utilization. To address the focused challenge of recycling, producing a high-value product such as SiO2 aerogel from CG is clearly an innovative approach.

Numerous methods exist for extracting SiO2 from CG, aiming to convert solid SiO2 into water-soluble sodium silicate and maximize the extraction yield. Conventional routes often involve direct thermal activation of CG to transform the contained kaolinite into amorphous metakaolin [25], or high-temperature calcination with activators to form new aluminosilicate phases and sodium silicate [26]. Subsequently, generating a sodium silicate solution requires removing metal impurities, particularly Al2O3, from the activated product. This demetallization step typically consumes large quantities of strong acids because, under alkaline hydrothermal conditions, the presence of alumina leads to the formation of insoluble aluminosilicates with SiO2, significantly suppressing silica leaching [27,28]. Furthermore, during the acid extraction of metal oxides, improper pH control can cause dissolved silica in the solution to gel, considerably complicating the process operation. To streamline silica extraction, we devised a strategy to thermodynamically and kinetically regulate the CG activation process. This approach enables the single-step, efficient generation of sodium silicate while mitigating interference from alumina, thereby eliminating the need for strong acids. Additionally, we directly induced sol–gel transition of the leachate using CO2, also avoiding the use of strong acids.

When combined with low-cost silica precursors such as sodium silicate derived from solid wastes, APD presents a promising pathway toward the mass production of cost-effective aerogels. It is both technically and economically feasible to extract SiO2 from various solid wastes and dry it under normal pressure to prepare aerogel. The common method of extracting SiO2 from solid waste through an acid-base two-step process to form a sol and then gel is adopted [29,30]. Moreover, APD is a cumbersome process to be reckoned with. It requires the water in the hydrogel to be replaced by alcohol, and then the alcohol to be replaced by n-hexane with a lower surface tension and surface hydrophobicity. Only in this way can the contraction and collapse of the pore structure be avoided during the atmospheric pressure drying process. However, the excessive use of silanizing agents, chlorosilanes (MTCS, DMCS, TMCS) will generate a large amount of strongly acidic gas [31,32]. All APD problems need to be solved, and this is also the task we will tackle in the future.

This study employed a simplified model of coal gangue to calculate the reaction thermodynamics between the gangue and alkali, followed by experimental optimization to enhance the SiO2 leaching rate. The leachate was then subjected to sol–gel transition via CO2 carbonation, and silica aerogel was successfully prepared using the ambient pressure drying (APD) method. The use of NaOH enabled efficient activation of coal gangue at relatively low temperatures, which is advantageous for SiO2 extraction and facilitates subsequent processes, such as alkali recovery and further utilization of the highly activated solid residue. Moreover, the CO2 carbonation approach eliminates the need for strong acids while consuming CO2, thereby reducing the carbon footprint associated with aerogel production. Inspired by the principle of high internal phase emulsions, the SiO2 aerogel particles were assembled into monolithic aerogels to overcome the intrinsic brittleness of silica that typically leads to powdered products. Finally, the thermal management capability of the prepared aerogel was intuitively evaluated under real-world conditions.

2. Methods

2.1. Raw Materials

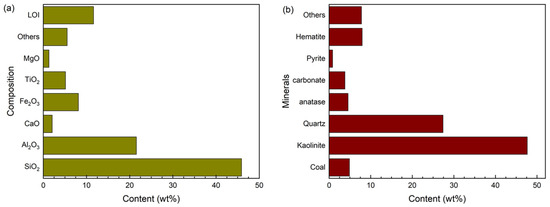

Coal gangue was obtained from Daxing Coal Mine of Liaoning Tiefa Coal Energy Co., Ltd (Diaobingshan, China). The main components were measured by XRF and XRD and are shown in Figure 1. The pure CO2 gas with a purity of 99.99% is provided by YIGAS group. The purity of other reagents is of the AR grade and was obtained from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China).

Figure 1.

Oxide Composition (a) and minerals (b) of CG used in this study.

2.2. Experimental Procedure

2.2.1. Silica Extraction

The obtained coal gangue was crushed to a particle size of less than 150 mesh, thoroughly mixed with a certain amount of activating agent, and then placed in a muffle furnace. The mixture was heated to the set temperature at a rate of 5 °C/min and held for a specified duration. After cooling to room temperature, the product was ground again and mixed with deionized water to leach out sodium silicate.

2.2.2. Silica Aerogel Synthesis

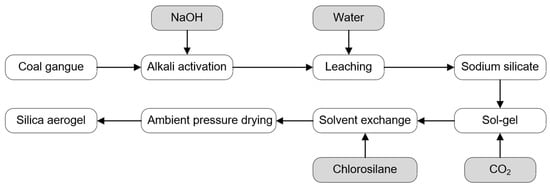

After SiO2 is extracted into the solution as sodium silicate, CO2 is introduced to induce sol–gel transition of the solution. The resulting gel is aged at 60 °C for one day, followed by three solvent exchanges with deionized water. The water is then replaced with ethanol, and hydrophobic modification is carried out using a hexane solution of trimethylchlorosilane (TMCS). After the modification, the product is washed with hexane to remove any unreacted modifying agent. Finally, the modified gel is dried to obtain SiO2 aerogel. The entire process consists of silica extraction and aerogel synthesis is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of silica extraction from CG, the sol–gel method, and the gel phase transfer.

2.3. Characterization

The physicochemical properties of the samples were characterized by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), X-ray diffraction (XRD), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), surface area and porosity analysis (BET), steady-state heat flow meter, and infrared thermography. The chemical functional groups of the synthesized materials were characterized by FTIR spectroscopy on a SHIMADZU FTIR-8400s spectrometer using KBr pellets. Crystal structures were determined by XRD on an X’Pert Pro MPD diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 0.154184 nm). Surface elemental states were analyzed via XPS on an ESCALAB 250Xi system. The material morphology was examined using a Hitachi S-4800 scanning electron microscope (SEM). The microstructure was further observed and analyzed using the JEM-2100F high-resolution TEM from JEOL Ltd. The compression-recovery performance was tested using a self-built electromechanical single-column compression-recovery device, following the ASTM D3574-17 standard [33]. The thermal conductivity of the aerogels was measured by a steady-state heat flow meter method employing an aluminum conductor (160 W), with the hot and cold sides set at 30 °C and 20 °C, respectively; the instrumental error was ±0.001 W·m−1·K−1. And each sample was tested three times. Specific surface area and pore structure were determined by nitrogen adsorption/desorption using a homemade analyzer at a vacuum degree of 1.0 Pa, with an error of ±1.5%. Temperature distribution and variations during thermal management tests were recorded using a Tiny1-B micro thermal imaging module.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Silica Extraction

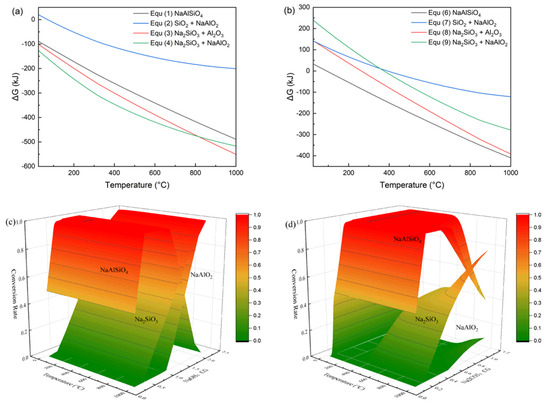

This section discusses the extraction of sodium silicate solution from CG after activation with an activating agent. Thermodynamic analysis was first performed to determine whether the activation reaction is spontaneous based on the Gibbs free energy (Equations (1)–(10)). The main minerals in CG are kaolinite and quartz. The Gibbs free energy changes for the reactions of kaolinite with NaOH and Na2CO3 were calculated, as shown in Figure 3a,b. Clearly, when NaOH is used, kaolinite more readily forms water-soluble Na2SiO3 and NaAlO2 below 800 °C, whereas with Na2CO3, it tends to form water-insoluble sodium aluminosilicate (nepheline) at around 1000 °C. To further analyze the reaction products, the equilibrium compositions of a simplified CG system—simulated by a mixture of 1.00 mol of kaolinite and 1.62 mol of SiO2—reacting with NaOH and Na2CO3 were calculated, as shown in Figure 3c,d. The formation of Na2SiO3 and NaAlO2 appears insensitive to temperature (Figure 3c); instead, increasing temperature primarily enhances the reaction kinetics by promoting the penetration of molten NaOH into the crystalline structure. Moreover, a high NaOH ratio enables excess NaOH to further react with the resulting NaAlSiO4. In contrast, Na2CO3 produces almost no NaAlO2 at lower temperatures, and the formation of Na2SiO3 is highly dependent on both the amount of Na2CO3 and the activation temperature (Figure 3d), which is consistent with previous experimental work [26]. When either NaOH or Na2CO3 is insufficient, NaAlSiO4 becomes the dominant product. Therefore, although using excess Na2CO3 to activate SiO2 in CG into Na2SiO3 leads to sharply increased cost and low extraction efficiency, an alternative approach can be adopted. Using a small amount of alkali to convert CG into highly reactive NaAlSiO4, which can then be acid-leached to dissolve metallic elements, leaving a relatively pure silica residue. This silica residue can be easily converted into sodium silicate solution via a simple hydrothermal process. Overall, compared with Na2CO3, NaOH offers significantly lower activation temperature, higher conversion rate, higher Na2SiO3 yield, and generates no CO2 during activation.

Al2O3·2SiO2·2H2O + 2NaOH → 2NaAlSiO4 + 3H2O(g)

Al2O3·2SiO2·2H2O + 2NaOH → 2SiO2 + 2NaAlO2 + 3H2O(g)

Al2O3·2SiO2·2H2O + 4NaOH → 2Na2SiO3 + Al2O3 + 4H2O(g)

Al2O3·2SiO2·2H2O + 6NaOH → 2Na2SiO3 + 2NaAlO2 + 5H2O(g)

2SiO2 + 4NaOH → 2Na2SiO3 + 2H2O(g)

Al2O3·2SiO2·2H2O + Na2CO3 → 2NaAlSiO4 + 2H2O(g) + CO2(g)

Al2O3·2SiO2·2H2O + Na2CO3 → 2SiO2 + 2NaAlO2 + 2H2O(g) + CO2(g)

Al2O3·2SiO2·2H2O + 2Na2CO3 → 2Na2SiO3 + Al2O3 + 2H2O(g) + 2CO2(g)

Al2O3·2SiO2·2H2O + 3Na2CO3 → 2Na2SiO3 + 2NaAlO2 + 2H2O(g) + 3CO2(g)

2SiO2 + 2Na2CO3 → 2Na2SiO3 + 2CO2(g)

Figure 3.

The Gibbs free energy of the kaolinite reaction with NaOH (a) and Na2CO3 (b), and the equilibrium conversion of the simplified CG composition activation products under NaOH (c) and Na2CO3 (d).

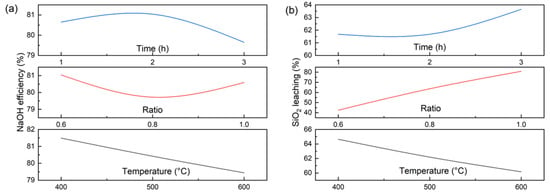

To elucidate the actual activation process, orthogonal experiments were conducted on CG with NaOH (Table 1). The subsequent factor analysis of temperature, alkali-to-gangue ratio, and activation time (Figure 4) revealed that the influence of these parameters on SiO2 leaching efficiency followed the order: NaOH dosage > temperature > activation time. Increasing the NaOH dosage significantly enhanced SiO2 leaching, achieving an efficiency of 83.8% (97.3% of the theoretical value). In contrast, NaOH utilization efficiency remained around 80% and was largely unaffected by the three factors. Both leaching efficiency and NaOH utilization decreased slightly with rising temperature. These trends suggest a diffusion-controlled activation mechanism, rather than one governed solely by thermodynamics or kinetics. Higher temperatures accelerate the surface reaction, forming a denser and thicker layer of sodium silicate/aluminate products that hinders the diffusion of molten NaOH into the unreacted CG core. Reducing the particle size of CG can mitigate this diffusion limitation and improve reaction efficiency.

Table 1.

Orthogonal experiment of SiO2 extraction.

Figure 4.

Factor analysis of NaOH efficiency (a) and SiO2 leaching (b).

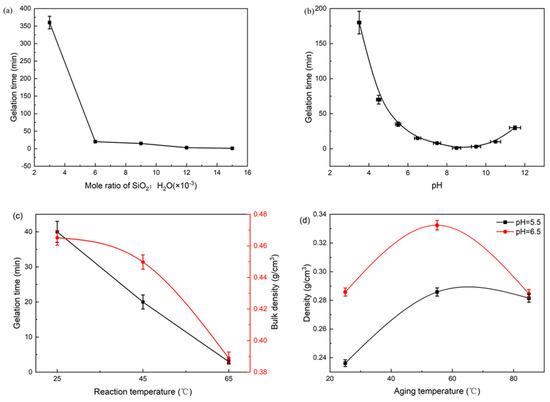

3.2. Sol–Gel Process

To optimize the aerogel preparation process, a single-variable analysis was conducted to investigate the effects of SiO2 concentration, sol–gel pH (adjusted with nitric acid), reaction temperature, and aging conditions, as summarized in Figure 5. The gelation time decreased sharply and then gradually with increasing SiO2 concentration, which can be attributed to a higher collision frequency and accelerated polycondensation rate of silicic acid particles. However, when the SiO2:H2O molar ratio exceeded 0.012, the addition of acid resulted in flocculation rather than gel formation. This occurs because excessive silica concentration leads to rapid, uncontrolled aggregation and phase separation, preventing the formation of a continuous three-dimensional network. At a fixed SiO2: H2O molar ratio of 0.006, the gelation time first decreased and then increased with rising pH, reaching a minimum at pH 8.5. This trend reflects the competing effects of pH on silicate polymerization: lower pH accelerates condensation but promotes particle flocculation, while higher pH increases electrostatic repulsion between particles, thereby delaying gel formation. When the reaction temperature was increased at the optimal pH of 5, the gelation time shortened significantly due to enhanced reaction kinetics. The corresponding reduction in xerogel density indicates the formation of a more developed porous structure, as higher temperature facilitates the formation of larger mesopores. Finally, the density of the resulting xerogel exhibited a non-monotonic trend, first increasing and then decreasing with higher aging temperatures. The initial increase is due to enhanced syneresis (gel shrinkage), which expels pore liquid and densifies the network. The subsequent decrease at higher aging temperatures is primarily governed by Ostwald ripening [34]. This process promotes the dissolution of smaller particles and the redeposition of silica onto larger particles and neck regions between them, thereby strengthening the gel network. A more robust network is better able to withstand the destructive capillary forces during the subsequent drying process, resulting in a xerogel with lower density and higher porosity.

Figure 5.

Analysis diagram of the sol–gel process using CG leaching solution, effects of (a) SiO2 concentration, (b) pH, and (c) reaction temperature on gelation time, with (c) also showing the resultant aerogel density; (d) effect of aging temperature on the density of the resulting aerogel.

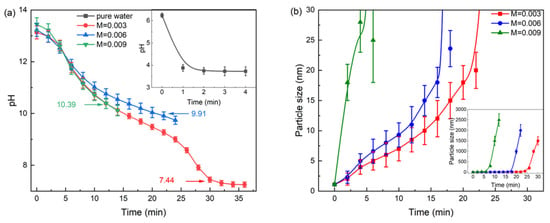

The sol–gel process entails the neutralization of Si–O− by H+ and subsequent condensation of Si–OH. It is noteworthy that the conventional reliance on additional acids for this step contributes to the overall carbon emissions in aerogel production. Consequently, we employed CO2 as a green alternative to form carbonic acid in situ (Equations (11)–(14)), thereby achieving the necessary gelation chemistry without the associated carbon footprint. Figure 6a illustrates the pH variation during the carbonation of leaching solutions with different concentrations under CO2 atmosphere. Compared to the carbonation of pure water, the pH decrease in the leaching solutions is significantly slower, and the gelation pH decreases as the concentration is reduced. After gelation, the gel remains slightly alkaline due to the hydrolysis of NaHCO3 and Na2CO3.

Figure 6.

Under CO2 atmosphere, the pH change and gelation pH of diluted CG leaching solution (a), and the change in particle size of diluted CG leaching solution (b).

Particle growth dynamics further revealed concentration-dependent behavior, as shown in Figure 6b. In solutions with molar ratios of 0.006 and 0.003, the particle size increased in an approximately linear manner, followed by a rapid acceleration just before the gelation point. In contrast, in the more concentrated solution (0.009), the particle size increased rapidly to 28 nm within 4 min, after which rapid gelation occurred. These phenomena can be explained by the coupling of silicate polymerization kinetics and physical mass-transfer limitations. At the 0.006 ratio, the concentration supported steady progression of silicic acid polymerization. This process consumes protons, creating a pronounced chemical buffering effect that effectively retards the pH decrease. In the dilute solution (0.003), the limited availability of silicate ions resulted mainly in monomer formation with minimal polymerization, leading to pH behavior dominated by acid-base equilibrium. The concentrated solution (0.009) exhibited a more complex two-stage mechanism: the initial rapid pH drop was likely caused by an intense, localized polymerization event that consumed protons vigorously. Subsequently, the sharp rise in viscosity from rapid oligomerization imposed severe mass-transfer limitations, hindering CO2 diffusion and shifting the rate-determining step from chemical reaction to physical diffusion. This accounts for the similar mid-term pH trend observed in the dilution-limited 0.003 system. The markedly shorter gelation time of the 0.009 solution stems directly from its high initial concentration, which promotes the rapid formation of a system-spanning silica network.

CO2 + H2O → H2CO3

Na2SiO3 + H2CO3 → H2SiO3 + Na2CO3

H2SiO3 → SiO2 + H2O

Na2CO3 + H2CO3 → 2NaHCO3

Si(CH3)Cl + C2H5OH → Si(CH3)3OC2H5 + HCl

Si(CH3)Cl + H2O → Si(CH3)3OH + HCl

O≡Si─OH + Si(CH3)Cl → O≡Si─O─Si(CH3)3 + HCl

O≡Si─OH + Si(CH3)3OC2H5 → O≡Si─O─Si(CH3)3 + C2H5OH

O≡Si─OH + Si(CH3)3OH → O≡Si─O─Si(CH3)3 + H2O

2Si(CH3)3OH → Si(CH3)3O(CH3)3 Si + H2O

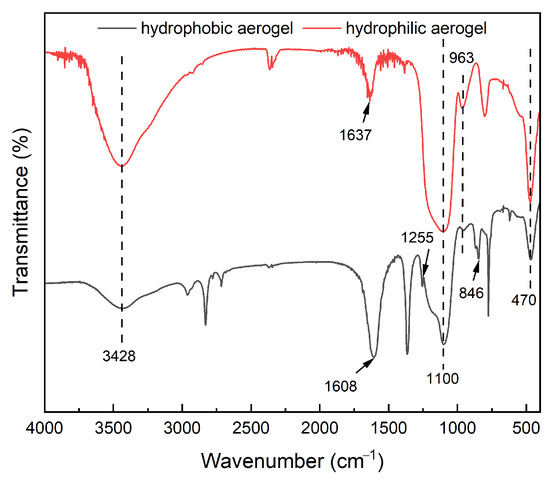

3.3. Morphology of SiO2 Aerogel

Silica aerogel was successfully prepared via sol–gel process induced by CO2 carbonation, followed by ambient pressure drying (APD). The reactions involved in the hydrophobic modification of the silica gel surface are presented in Equations (15)–(20). The FT-IR spectrum of the hydrophobically modified gel is shown in Figure 7. The absorption peak at 3428 cm−1 corresponds to the stretching vibrations of Si–OH and adsorbed water [35]. Furthermore, the intramolecular stretching vibration of the Si-OH group occurs at approximately 963 cm−1 [36]. In hydrophilic aerogels, the abundant Si–OH groups on the SiO2 surface form strong hydrogen bonds with each other or with adsorbed water molecules. This results in an energy level shift in the H–O–H bending vibration, causing a blue shift and appearing at 1637 cm−1 [37]. In contrast, in hydrophobic aerogels, most Si–OH groups are replaced by Si–CH3. The remaining Si–OH groups are isolated by surrounding methyl groups, reducing water adsorption and hydrogen bonding. As a result, the bending vibration exhibits a red shift, observed at 1608 cm−1. The peak at 1255 cm−1 is attributed to the symmetric bending vibration of Si–CH3, and the absorption at 846 cm−1 corresponds to the stretching vibration of Si–C [38]. These peaks confirm the successful modification of the aerogel with the silane agent. Finally, the broad band around 1100 cm−1 is assigned to the asymmetric stretching vibration of Si–O–Si [39], while the peak at 470 cm−1 arises from the bending vibration of Si–O–Si [40]. Both signals indicate the presence of a typical silica network structure.

Figure 7.

FTIR spectrum of silica aerogel before and after modification.

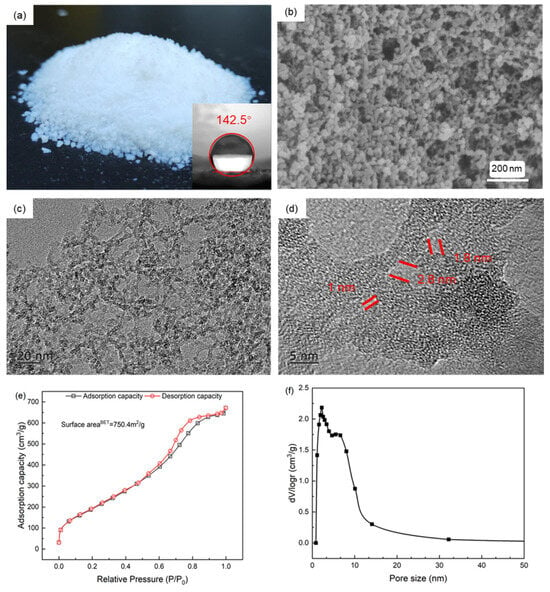

The most promising industrial application of SiO2 aerogels lies in thermal management. The thermal insulation performance of aerogels primarily relies on their pore size being smaller than the mean free path of air molecules, thereby suppressing gas convection by immobilizing air within the nanostructure. Firstly, the tapped density of this aerogel is 60 mg/cm3. As shown in the digital and SEM images in Figure 8b, the prepared silica aerogel particles exhibit Rayleigh scattering—a characteristic feature of gel-based materials. The microstructure consists of a typical porous network formed by the interconnection of spherical SiO2 nanoparticles with a uniform diameter of approximately 20 nm. The neck regions between particles appear comparable in size to the particle diameter, suggesting structural uniformity aided by Ostwald ripening during gelation. TEM images in Figure 8c,d further reveal that the aerogel skeleton contains uniformly distributed mesopores. At higher magnification, ultrafine pores smaller than 2 nm are observed. These ultrafine pores not only help reduce the density of the solid framework but also lower its thermal conduction efficiency. Moreover, according to the Knudsen effect, air molecules become increasingly stagnant within finer pores, collectively contributing to the aerogel’s low thermal conductivity. Nitrogen adsorption–desorption analysis revealed a type-IV isotherm with an H2-type hysteresis loop. The distinct desorption plateau suggests a uniform pore structure, which is further corroborated by the narrow pore size distribution ranging from 2 to 15 nm. However, a maximum appears around 2 nm, probably due to the most condensed silica precursor and the Oswald process that form little pores with less Si-OH remnant groups. BET measurements confirmed a specific surface area of 750.4 m2/g, and the pore size distribution analysis indicated a predominance of pores below 30 nm, confirming that the aerogel synthesized via CO2-assisted gelation is a nanocomposite containing both nanopores and mesopores.

Figure 8.

Digital photos and water contact angle (a), SEM image (b), TEM images (c,d), nitrogen adsorption and desorption isotherm (e), and pore size distribution (f) of SiO2 aerogel.

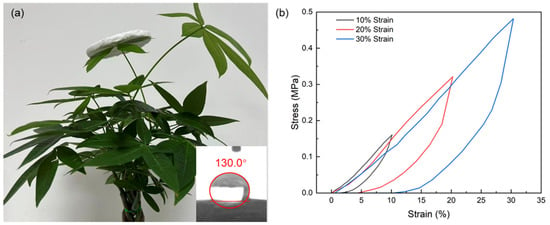

3.4. Thermal Management of Aerogels

The obtained aerogel particles exhibit a remarkable thermal conductivity of 0.022 W·m−1·K−1, demonstrating comparable insulation performance to leading commercial aerogel particles (0.023 W·m−1·K−1, Cabot P100, P200 & P300 series) [41]. To facilitate handling and testing, a moldable, solid-like composite was prepared using an aqueous PVA solution as the continuous phase and SA particles as a high-volume fraction dispersed phase. After drying at ambient temperature and pressure, a monolithic aerogel was obtained, exhibiting a thermal conductivity of 0.028 W·m−1·K−1. The resulting monolithic aerogel achieved a density of approximately 80 mg/cm3, representing a significant reduction compared to the original powdered form. This decrease is attributed to the structural collapse and pore destruction caused by grinding the aerogel into particles, followed by re-bonding during the monolithic formation process. Nevertheless, as demonstrated in Figure 9, the obtained aerogel monolith remains sufficiently lightweight to stand steadily on the most tender and delicate leaf. The hydrophobicity of the powdered aerogel decreased slightly from 143.5° to 130° after being formed into a monolith. This reduction is attributed to the introduction of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), which has amphiphilic properties and lower inherent hydrophobicity compared to the aerogel itself. The PVA adheres to the aerogel surface, thereby reducing its overall hydrophobicity.

Figure 9.

The image of SiO2 aerogel monolith (a), and the compression rebound stress–strain curves of SiO2 aerogel monolith (b).

The compression-rebound curves of the SiO2 aerogel monolith (Figure 9b) exhibit an approximately linear response under loading at peak strains of 10%, 20%, and 30%. This pronounced linearity arises from the collective elastic response of the PVA-bonded network, where the reversible stretching of polymer chains, slight bending of the SiO2 skeleton, synergistically contribute to a near-linear stress increase. However, the material’s ability to recover its original shape diminishes significantly with increasing strain. At 10% strain, the aerogel demonstrates nearly complete elastic recovery, indicating minimal structural damage. At 20% strain, noticeable residual deformation occurs, suggesting the onset of irreversible pore collapse or partial yielding in the PVA-bonded SiO2 network. When the strain exceeds 30%, the aerogel undergoes substantial plastic deformation and cannot return to its initial state, implying that the cellular architecture experiences irreversible damage such as pore wall buckling, particle dislodgment, or permanent deformation of the polymer binder. This strain-dependent recovery behavior reflects the transition from elastic bending and stretching of the network at low strains to progressive, irreversible structural collapse at higher deformations.

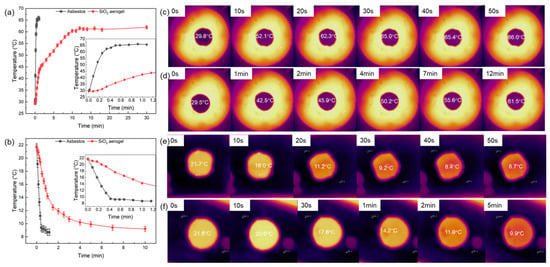

To evaluate the practical thermal management performance, the monolithic aerogel was placed over both a 110 °C heat source and a −20 °C cold source, while its surface temperature was monitored over time. For comparison, tests were also conducted using an asbestos plate of the same thickness. And the results are shown in Figure 10. When placed over the heat source, the surface temperature of both the asbestos and the SiO2 aerogel increased with time. However, the thermal insulation performance of the aerogel was significantly superior. The temperature of the asbestos reached 66.0 °C within 50 s, whereas the aerogel only reached 61.5 °C after 12 min. The surface temperature of the asbestos rose sharply, while the aerogel exhibited a rapid initial temperature increase followed by a much slower heating rate. This initial rapid rise is attributed to the heating of the air layer adjacent to the aerogel surface by the heat source. In the cold source test, the aerogel also demonstrated far better insulation than asbestos. The temperature of the asbestos dropped sharply, while the cooling rate of the aerogel continuously decreased. The temperature of the asbestos fell to 8.4 °C in 40 s, while the aerogel only decreased to 9.9 °C after 5 min. Based on its ultralow thermal conductivity and its exceptional performance in both heating and cooling scenarios, the aerogel prepared in this work exhibits outstanding thermal management capability.

Figure 10.

Low and high management performance of aerogel versus asbestos: (a,b) temperature evolution over time on an open heat source and cold source, respectively; (c,d) infrared thermal images of asbestos and aerogel on the heat source; (e,f) corresponding infrared thermal images on the cold source.

4. Conclusions

This study successfully demonstrates a complete pathway for valorizing coal gangue into high-value silica aerogel with superior thermal insulation properties. The key findings are summarized as follows:

- Activation Optimization: Thermodynamic and experimental analyses established NaOH as an efficient activator for CG. The process is predominantly diffusion-controlled, and the optimal conditions yielded a high SiO2 leaching efficiency of 83.81%, closely approaching the theoretical maximum.

- Controlled Gelation: The sol–gel process via CO2 carbonation was effectively optimized. And reveal that the CO2-driven gelation is a concentration-dependent process governed by the competition between silicate polymerization kinetics and CO2 mass transfer, which dictates the microstructural evolution of the silica network.

- Successful APD: Hydrophobic silica aerogel powder with low thermal conductivity of 0.022 W·m−1·K−1, a high specific surface area of 750.4 m2/g and a narrow pore size distribution ranging from 2 to 15 nm was successfully prepared via APD, and subsequently shaped into monolithic aerogels using a straightforward to blend with PVA solution.

- Excellent Insulating Performance: Monolithic aerogels had appreciable compressibility and resilience. Practical tests, including exposure to a −20 °C cold source and a 110 °C heat source, unequivocally proved its superior thermal management capability compared to conventional materials like asbestos.

In summary, this study not only presents a method for synthesizing high-performance aerogels from waste coal gangue, but also provides an in-depth exploration of the activation mechanism between coal gangue and NaOH, alongside the CO2-induced gelation mechanism. The practical thermal management capability of the prepared aerogel was experimentally verified, highlighting its significant potential for large-scale industrial deployment in the field of thermal insulation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.C.; methodology, Y.C. and C.C.; validation, Y.C. and C.C.; formal analysis, Chen Chenggang and H.L.; investigation, Z.S.; resources, Y.C.; data curation, Sun Zhe and H.L.; writing—original draft preparation, C.C.; writing—review and editing, Y.C.; supervision, Y.C.; funding acquisition, Y.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 22178339), 2023 Innovation-driven Development Special Foundation of Guangxi Province (AA23023021), the University Science Research Project of Anhui Province (2022AH050076), Open Project of Anhui Provincial Key Laboratory of Chemistry for Inorganic/Organic Hybrid Functionalized Materials (IOHFMAH-2505), the Hundred Talents Program (A) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this research can be obtained by sending an email to corresponding author (caoyan@ms.giec.ac.cn).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Tabata, M.; Adachi, I.; Ishii, Y.; Kawai, H.; Sumiyoshi, T.; Yokogawa, H. Development of transparent silica aerogel over a wide range of densities. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Accel. Spectrometers Detect. Assoc. Equip. 2010, 623, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Liu, L.; Wang, J. Silica aerogels as functional units for shapeable thermal management materials: Synthesis, mechanisms, and emerging applications. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 522, 167640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Stojanovic, A.; Angelica, E.; Emery, O.; Rentsch, D.; Pauer, R.; Koebel, M.M.; Malfait, W.J. Phase transfer agents facilitate the production of superinsulating silica aerogel powders by simultaneous hydrophobization and solvent- and ion-exchange. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 381, 122421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fricke, J.; Lu, X.; Wang, P.; Büttner, D.; Heinemann, U. Optimization of monolithic silica aerogel insulants. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 1992, 35, 2305–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosrati, R.; Berardi, U. Long-term performance of aerogel-enhanced materials. Energy Procedia 2017, 132, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Błaszczyński, T.; Ślosarczyk, A.; Morawski, M. Synthesis of Silica Aerogel by Supercritical Drying Method. Procedia Eng. 2013, 57, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, W.; Chen, L.; Kong, Q.; Li, L.; Chen, M.; Jiang, J.; Li, W.; Shi, F.; Xu, Z. The Synthesis and Polymer-Reinforced Mechanical Properties of SiO2 Aerogels: A Review. Molecules 2023, 28, 5534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilonga, A.H. A brief history and prospects of sodium silicate-based aerogel—A review. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2024, 112, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Liu, Y.; Lin, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, C.; Sun, L.; Gui, H. Toxicity of coal fly ash and coal gangue leachate to Daphnia magna: Focusing on typical heavy metals. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 330, 129946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, J. Comprehensive utilization and environmental risks of coal gangue: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 239, 117946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, W.; Liu, Y. A review on hazard, solidification mechanism, and novel perspective of Arsenic (As) in coal-related energy waste-based materials. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 1005, 180814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Wu, D.; Xu, F.; Lai, J.; Shao, L. Literature overview of Chinese research in the field of better coal utilization. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 185, 959–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, D.-Y.; Wang, C.-Q.; Bai, D.-S.; Huang, D.-M. Representative coal gangue in China: Physical and chemical properties, heavy metal coupling mechanism and risk assessment. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2024, 37, 101402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xiong, R.; Zong, Y.; Li, L.; Guo, H.; Wang, Z.; Guan, B.; Chang, M. Effect of raw material ratio and sintering temperature on properties of coal gangue-feldspar powder artificial aggregate. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 384, 131400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Feng, X.; Wang, Z.; Jian, J.; Chen, S.; Luo, W.; Zhang, C. Experimental study on the physico-mechanical properties and microstructure of foam concrete mixed with coal gangue. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 359, 129428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, L.; Zhang, T. Research progress on the recovery of strategic metals lithium and gallium from coal-based solid wastes: From mineral deconstruction to resource utilization. Miner. Eng. 2026, 235, 109775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snehasree, N.; Nuruddin, M.; Moghal, A.A. Critical Appraisal of Coal Gangue and Activated Coal Gangue for Sustainable Engineering Applications. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 9649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, R.; Chen, X.; Li, J.; Gu, Z.; Wang, J. Impacts of Thermal Activation on Physical Properties of Coal Gangue: Integration of Microstructural and Leaching Data. Buildings 2025, 15, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilikwazi, B.; Onyari, J.M.; Wanjohi, J.M. Determination of heavy metals concentrations in coal and coal gangue obtained from a mine, in Zambia. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 20, 2053–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Chen, G.; Li, J.; Liu, G.; Lang, D.; Guo, J.; Wang, W.; Wu, R. Upgrading Coal Gangue Waste into Molecular Sieves for Sustainable Wastewater Purification. Langmuir 2025, 41, 24572–24581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.; Wang, Z.; Chen, L.; Wu, S.; Li, D.; Ma, H.; Kim, S.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y. Modified coal gangue enables synchronous sandy soil remediation and safe potato production: Efficacy and mechanisms. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 525, 146645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Pan, L.; Li, N.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, X.; Liu, F.; Zhu, J.; Du, M. Comparative study of gangue fine aggregate strengthening technologies: Microbially induced mineralization, water glass strengthening, and composite strengthening. Waste Dispos. Sustain. Energy 2025. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Liu, Y.; Liu, S.; Wang, W.; Liu, J.; Lv, Z.; Liu, R. The Effect of Coal Gangue Fertilizer and Chemical Fertiliser Allocation on Maize Growth and Soil Nutrients. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2025. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Yang, C.; Ma, B.; Yang, H.; Cao, Z.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, C. Selective separation of Fe and Ga from Al-rich HNO3 leach liquor using sequential solvent extraction. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 118086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, J.; Hao, Z. The thermal activation process of coal gangue selected from Zhungeer in China. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2016, 126, 1559–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Yan, K.; Cui, L.; Cheng, F.; Lou, H.H. Effect of Na2CO3 additive on the activation of coal gangue for alumina extraction. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2014, 131, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Huang, H.; Tang, W.; Liu, X.; Yang, X.; Zhang, J. Preparation and characterization of a novel porous silicate material from coal gangue. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2015, 217, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Feng, K.; Wang, L.; Yu, Q.; Du, F.; Li, Y.; Yu, K. Transformation of Coal Gangue to Sodalite and Faujasite Using Alkali-hydrothermal Method. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol. Mater. Sci. Ed. 2023, 38, 1391–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.; Gao, Y.; Song, S.; Jiang, R. Kinetics and Mechanism of SiO2 Extraction from Acid-Leached Coal Gangue Residue by Alkaline Hydrothermal Treatment. Materials 2024, 17, 4168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, J.; Li, F.; Zhong, Q.; Bao, H.; Wang, B.; Huang, J.; Zhang, Y. Separation of aluminum and silica from coal gangue by elevated temperature acid leaching for the preparation of alumina and SiC. Hydrometallurgy 2015, 155, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khedkar, M.V.; Somvanshi, S.B.; Jadhav, K.M. Sol-gel-derived hydrophobic silica aerogels for oil cleanup: Effect of silylation. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2025, 116, 958–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahadik, D.B.; Rao, A.V.; Rao, A.P.; Wagh, P.B.; Ingale, S.V.; Gupta, S.C. Effect of concentration of trimethylchlorosilane (TMCS) and hexamethyldisilazane (HMDZ) silylating agents on surface free energy of silica aerogels. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2011, 356, 298–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ASTM D3574-17; Standard Test Methods for Flexible Cellular Materials—Slab, Bonded, and Molded Urethane Foams. West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- Iswar, S.; Malfait, W.J.; Balog, S.; Winnefeld, F.; Lattuada, M.; Koebel, M.M. Effect of aging on silica aerogel properties. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2017, 241, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Oweini, R.; El-Rassy, H. Synthesis and characterization by FTIR spectroscopy of silica aerogels prepared using several Si(OR)4 and R′′Si(OR′)3 precursors. J. Mol. Struct. 2009, 919, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopal, N.O.; Narasimhulu, K.V.; Rao, J.L. EPR, optical, infrared and Raman spectral studies of Actinolite mineral. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2004, 60, 2441–2448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socrates, G. Infrared and Raman Characteristic Group Frequencies: Tables and Charts; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Gunzler, H.; Gremlich, H.-U. IR Spectroscopy: An Introduction; Wiley-VCH: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Duran, A.; Serna, C.; Fornes, V.; Fernandez Navarro, J.M. Structural considerations about SiO2 glasses prepared by sol-gel. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 1986, 82, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoluzza, A.; Fagnano, C.; Antonietta Morelli, M.; Gottardi, V.; Guglielmi, M. Raman and infrared spectra on silica gel evolving toward glass. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 1982, 48, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P100, P200, & P300 AEROGEL PARTICLES. 2021. Available online: https://www.cabotcorp.com/-/media/files/product-datasheets/datasheet-aerogel-p100pdf.pdf?rev=8e78401f8a7d4cd2a14f3e2fdea82b77&hash=39D6DC0BAB41146AD957BB6C114553F4 (accessed on 4 December 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).