The Role of Bioactive Glasses in Caries Prevention and Enamel Remineralization

Abstract

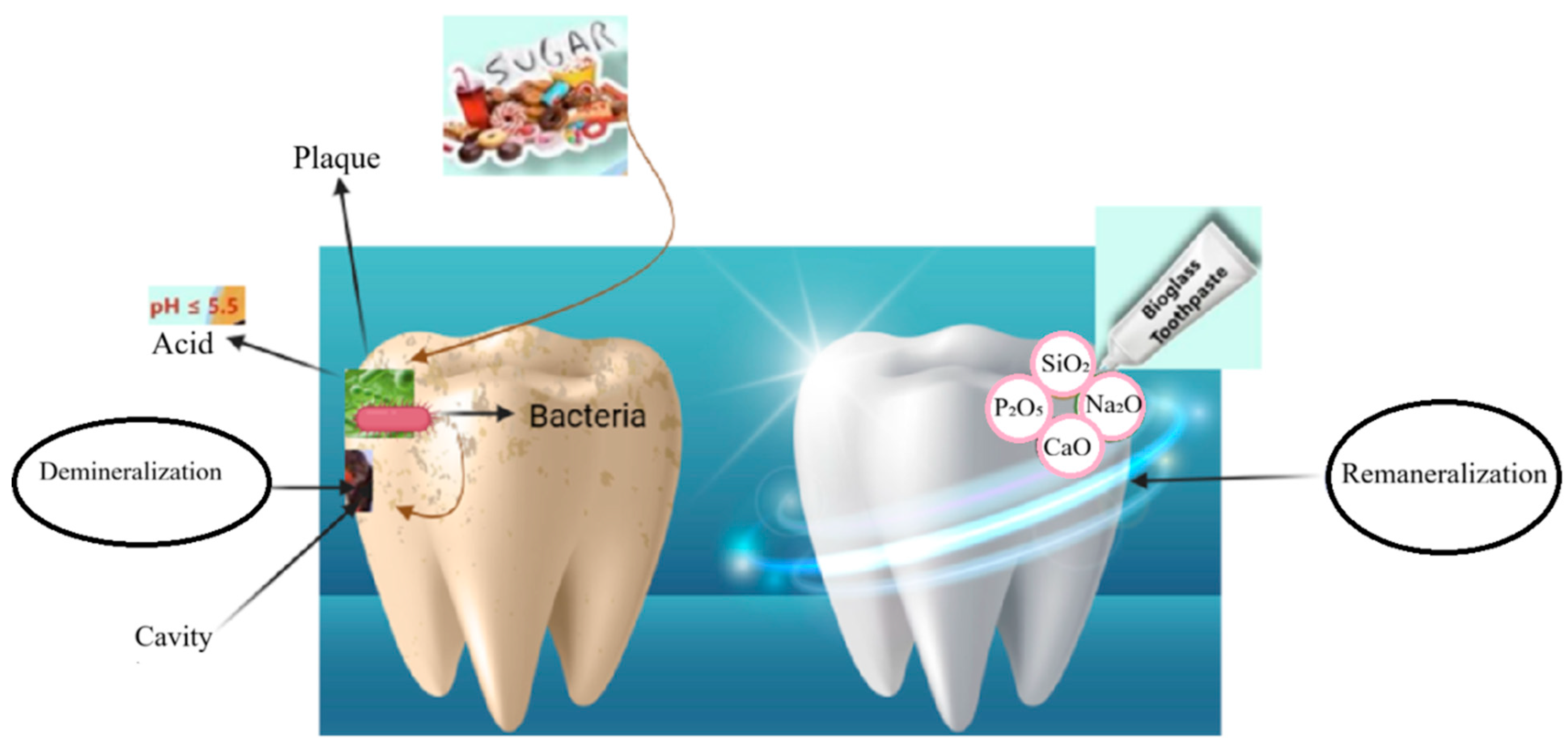

1. Introduction

2. Overview of BGs in Dentistry

2.1. History and Development

2.2. Classification of BGs

2.3. Mechanisms of Action

2.4. Delivery Systems

3. Enamel Remineralization Potential of Different BGs

3.1. Formulation Variants

3.2. Material Properties

4. Prevention of Demineralization and Early Lesion Progression

4.1. pH Buffering and Acid Neutralization

4.2. Biofilm Modulation and Pathogenic Shift Reduction

4.3. Performance in Early Lesion Models

5. Modified and Ion-Doped BGs

5.1. β-TCP and fTCP Integration

5.2. CPP–ACP Integration

5.3. Synergistic Approaches with Fluoride, Chitosan, and Polymers

5.4. Biomimetic Crystallization Pathways

6. Bioactive Glass Studies in Caries Prevention and Enamel Remineralization

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dye, B.A. The global burden of oral disease: Research and public health significance. J. Dent. Res. 2017, 96, 361–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatzidimitriou, K.; Theodorou, K.; Seremidi, K.; Kloukos, D.; Gizani, S.; Papaioannou, W. The role of hydroxyapatite-based, fluoride-free toothpastes on the prevention and the remineralization of initial caries lesions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Dent. 2025, 156, 105691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.L.; Mei, M.L.; Chu, C.H.; Lo, E.C.M. Mechanisms of bioactive glass on caries management: A review. Materials 2019, 12, 4183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Cabezas, C.; Fernández, C.E. Recent advances in remineralization therapies for caries lesions. Adv. Dent. Res. 2018, 29, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, O.L.; Niu, J.Y.; Yin, I.X.; Yu, O.Y.; Mei, M.L.; Chu, C.H. Bioactive materials for caries management: A literature review. Dent. J. 2023, 11, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiume, E.; Barberi, J.; Verné, E.; Baino, F. Bioactive glasses: From parent 45S5 composition to scaffold-assisted tissue-healing therapies. J. Funct. Biomater. 2018, 9, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, K.; Sui, B.; Ilyas, K.; Boccaccini, A.R. Porous bioactive glass micro-and nanospheres with controlled morphology: Developments, properties and emerging biomedical applications. Mater. Horiz. 2021, 8, 300–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallet-Regí, M.; Colilla, M.; Izquierdo-Barba, I.; Vitale-Brovarone, C.; Fiorilli, S. Achievements in mesoporous bioactive glasses for biomedical applications. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, J.S.; Gentile, P.; Pires, R.A.; Reis, R.L.; Hatton, P.V. Multifunctional bioactive glass and glass-ceramic biomaterials with antibacterial properties for repair and regeneration of bone tissue. Acta Biomater. 2017, 59, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenspan, D. Bioglass at 50—A look at Larry Hench’s legacy and bioactive materials. Biomed. Glas. 2019, 5, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siekkinen, M. The Impact of Dissolution Products and Solution pH on In Vitro Behaviour of the Bioactive Glasses 45S5 and S53P4. Master’s Thesis, Åbo Akademi University, Turku, Finland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Baino, F.; Hamzehlou, S.; Kargozar, S. Bioactive glasses: Where are we and where are we going? J. Funct. Biomater. 2018, 9, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, X.; Segura-Egea, J.J.; Díaz-Cuenca, A. Sol–Gel technologies to obtain advanced bioceramics for dental therapeutics. Molecules 2023, 28, 6967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kargozar, S.; Baino, F.; Hamzehlou, S.; Hill, R.G.; Mozafari, M. Bioactive glasses: Sprouting angiogenesis in tissue engineering. Trends Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 430–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Örtengren, U.; Lehrkinder, A.; Safarloo, A.; Axelsson, J.; Lingström, P. Opportunities for caries prevention using an ion-releasing coating material: A randomised clinical study. Odontology 2021, 109, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BioMin, F. BioMin F ten times more acid-resistant than NovaMin toothpastes. Br. Dent. J. 2023, 235, 148. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.; Guo, W.; Cui, L.; Xiang, D.; Cai, K.; Lin, H.; Qu, F. pH-responsive controlled-release system based on mesoporous bioglass materials capped with mineralized hydroxyapatite. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2014, 36, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, K.; Kovářík, T.; Křenek, T.; Docheva, D.; Stich, T.; Pola, J. Recent advances and future perspectives of sol–gel derived porous bioactive glasses: A review. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 33782–33835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mecca, F.G.; Bellucci, D.; Cannillo, V. Effect of thermal treatments and ion substitution on sintering and crystallization of bioactive glasses: A review. Materials 2023, 16, 4651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, L.C. Sol-Gel Glasses. In Springer Handbook of Glass; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 1333–1354. [Google Scholar]

- Ramadoss, R.; Padmanaban, R.; Subramanian, B. Role of bioglass in enamel remineralization: Existing strategies and future prospects—A narrative review. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B Appl. Biomater. 2022, 110, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Kaff, A.A.; Alshehri, A.Z.; Alasmari, R.A.; Alsubaie, N.; Aldaws, A.; Althaqeel, A.; Alshehri, R.S.; Alawaji, Y.M.; Alkaff, A.A. Minimally Invasive Techniques for Managing Dental Caries in Children: Efficacy, Applications, and Future Directions. Cureus 2025, 17, e87450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliberti, A.; Di Duca, F.; Triassi, M.; Montuori, P.; Scippa, S.; Piscopo, M.; Ausiello, P. The Effect of Different pH and Temperature Values on Ca2+, F−, PO43−, OH−, Si, and Sr2+ Release from Different Bioactive Restorative Dental Materials: An In Vitro Study. Polymers 2025, 17, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, B. The Synergistic Effect of High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound and Amorphous Calcium Phosphate Nanoparticles on the Biomimetic Remineralization of Dental Enamel. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Western Australia, Perth, Australia, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Pashley, D.H. Dentin permeability, dentin sensitivity, and treatment through tubule occlusion. J. Endod. 1986, 12, 465–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lertwisitphon, P.; Worapasphaiboon, Y.; Champakanan, N.; Toneluck, A.; Naruphontjirakul, P.; Young, A.M.; Chinli, R.; Chairatana, P.; Sucharit, S.; Panpisut, P. Enhancing elemental release and antibacterial properties of resin-based dental sealants with calcium phosphate, bioactive glass, and polylysine. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moradi, A.; Sharifianjazi, F.; Tavamaishvili, K.; Bakhtiari, A.; Mohammadi, A. A Review of samarium-containing bioactive glasses: Biomedical applications. J. Compos. Compd. 2025, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Skallevold, H.E.; Rokaya, D.; Khurshid, Z.; Zafar, M.S. Bioactive glass applications in dentistry. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirwais, A. Effect of Tooth Mousse Containing Bioactive Glass on Remineralisation of Teeth. Ph.D. Thesis, Queen Mary University of London, London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, M.; Yamada, A.; Saito, K.; Hino, R.; Sugawara, Y.; Ono, M.; Naruse, M.; Arakaki, M.; Fukumoto, S. Application of a tooth-surface coating material containing pre-reacted glass-ionomer fillers for caries prevention. Pediatr. Dent. J. 2015, 25, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farjaminejad, R.; Farjaminejad, S.; Hasani, M.; Garcia-Godoy, F.; Sayahpour, B.; Marya, A.; Jamilian, A. The Role of Tissue Engineering in Orthodontic and Orthognathic Treatment: A Narrative Review. Oral 2025, 5, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosquim, V.; Wang, L.; Zabeu, G.S.; Francisconi-dos-Rios, L.F.; Gillam, D.G.; Magalhães, A.C. Treatment Modalities and Procedures. In Dentine Hypersensitivity: Advances in Diagnosis, Management, and Treatment; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 99–130. [Google Scholar]

- Mneimne, M.; Hill, R.G.; Bushby, A.J.; Brauer, D.S. High phosphate content significantly increases apatite formation of fluoride-containing bioactive glasses. Acta Biomater. 2011, 7, 1827–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Körner, P.; Schleich, J.A.; Wiedemeier, D.B.; Attin, T.; Wegehaupt, F.J. Effects of additional use of bioactive glasses or a hydroxyapatite toothpaste on remineralization of artificial lesions in vitro. Caries Res. 2020, 54, 336–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- François, P.; Benoit, A.; Slimani, L.; Dufresne, A.; Gouze, H.; Attal, J.P.; Mangione, F.; Dursun, E. In vitro remineralization by various ion-releasing materials of artificially demineralized dentin: A micro-CT study. Dent. Mater. 2024, 40, 520–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhivya, V.; Mahalaxmi, S.; Rajkumar, K.; Premkumar, V.V.; Saravanakarthikeyan, B.; Karpagam, R.; Priyatharshini, R.; Sakthipandi, K.; Saikumari, V.; Vijay, N.; et al. Effects of strontium-containing fluorophosphate glasses for enhancing bioactivity and enamel remineralization. Mater. Charact. 2021, 181, 111496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Eesa, N.A.; Fernandes, S.D.; Hill, R.G.; Wong, F.S.L.; Jargalsaikhan, U.; Shahid, S. Remineralising fluorine containing bioactive glass composites. Dent. Mater. 2021, 37, 672–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleem, M.M.; Eid, E.S.G.; Abdelghany, A.M.; Farahat, D.S. Evaluation of the remineralization potential of different bioactive glass varnishes on white spot lesions: An in vitro study. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Goyal, A.; Gauba, K.; Kapur, A.; Singh, S.K.; Mehta, S.K. An evaluation of remineralised MIH using CPP-ACP and fluoride varnish: An in-situ and in-vitro study. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2022, 23, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taye, M.B. Biomedical applications of ion-doped bioactive glass: A review. Appl. Nanosci. 2022, 12, 3797–3812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Chen, R.; Xie, Y.; Gao, Y.; Ma, L.; Li, B.; Yao, W. Research progress of bioactive glass in the remineralization of dental hard tissue. Biomed. Phys. Eng. Express 2025, 11, 052001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, W.E.; Mangum, J.E.; Schneider, P.M. Pathophysiology of demineralization, part II: Enamel white spots, cavitated caries, and bone infection. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 2022, 20, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asadi, M.; Majidinia, S.; Bagheri, H.; Hoseinzadeh, M. The effect of formulated dentin remineralizing gel containing hydroxyapatite, fluoride, and bioactive glass on dentin microhardness: An in vitro study. Int. J. Dent. 2024, 2024, 4788668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xynos, I.D.; Hukkanen, M.V.J.; Batten, J.J.; Buttery, L.D.; Hench, L.L.; Polak, J.M. Bioglass® 45S5 stimulates osteoblast turnover and enhances bone formation in vitro: Implications and applications for bone tissue engineering. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2000, 67, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.; Chen, S.; Lei, Q.; Ma, D. A novel rapidly mineralized biphasic calcium phosphate with high acid-resistance stability for long-term treatment of dentin hypersensitivity. Dent. Mater. 2023, 39, 260–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Jia, J.; Wu, L.; Huang, T.; Chen, M.; Niu, W.; Yang, T.; Zhou, Q.; Lei, B.; Li, Y. Antibacterial and metalloproteinase-inhibited zinc-doped bioactive glass nanoparticles for enhancing dentin adhesion. J. Dent. 2025, 154, 105610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahmasbi, S.; Amdjadi, P.; Aghamohammadi, Z.; Sedighinia, M. Remineralizing and Antibacterial Properties, and Durability of a Silver-Doped Nanostructured Bioglass Resin Sealant on the Enamel. Iran. J. Orthod. 2025, 20, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, L.L.; Mei, M.L.; Chu, C.H.; Lo, E.C.M. Remineralizing effect of a new strontium-doped bioactive glass and fluoride on demineralized enamel and dentine. J. Dent. 2021, 108, 103633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleibi, A.; Tappuni, A.R.; Karpukhina, N.G.; Hill, R.G.; Baysan, A. A comparative evaluation of ion release characteristics of three different dental varnishes containing fluoride either with CPP-ACP or bioactive glass. Dent. Mater. 2019, 35, 1695–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karlinsey, R.L.; Pfarrer, A.M. Fluoride plus functionalized β-TCP: A promising combination for robust remineralization. Adv. Dent. Res. 2012, 24, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto de Souza, S.C.T.; Araújo, K.C.D.; Barbosa, J.R.; Cancio, V.; Rocha, A.A.; Tostes, M.A. Effect of dentifrice containing fTCP, CPP-ACP and fluoride in the prevention of enamel demineralization. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2018, 76, 188–194. [Google Scholar]

- Tina, A.; Abbas, F.; Maryam, F.; Zahra, K.; Ramtin, D. Synthesis and characterization of nano bioactive glass for improving enamel remineralization ability of casein phosphopeptide-amorphous calcium phosphate (CPP-ACP). BMC Oral Health 2022, 22, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, S.; Ma, X.; Yu, S.; Wang, R. Chitosan as a biomaterial for the prevention and treatment of dental caries: Antibacterial effect, biomimetic mineralization, and drug delivery. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1234758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, W.; Mehboob, A.; Han, M.G.; Chang, S.H. Novel biodegradable hybrid composite of polylactic acid (PLA) matrix reinforced by bioactive glass (BG) fibres and magnesium (Mg) wires for orthopaedic application. Compos. Struct. 2020, 245, 112322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, C.; Wang, K.Y.; Ma, Y.X.; Hao, D.X.; Zhu, Y.N.; Wan, Q.Q.; Zhang, J.S.; Tay, F.R.; Mu, Z.; Niu, L.N. Biomimetic Self-Maturation Mineralization System for Enamel Repair. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2311659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, N.R. Effects of Zinc and Fluoride on In Vitro Enamel Demineralisation Conditions Relevant to Dental Caries. Ph.D. Thesis, Queen Mary University of London, London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, J.K.; Gillam, D. Efficacy of a BioMin F Toothpaste Compared to Conventional Toothpastes in Remineralisation and Dentine Hypersensitivity: An Overview. J. Dent. Maxillofac. Res. 2025, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Prabhakar, A.R.; Arali, V. Comparison of the remineralizing effects of sodium fluoride and bioactive glass using bioerodible gel systems. J. Dent. Res. Dent. Clin. Dent. Prospect. 2009, 3, 117. [Google Scholar]

- Palaniswamy, U.K.; Prashar, N.; Kaushik, M.; Lakkam, S.R.; Arya, S.; Pebbeti, S. A comparative evaluation of remineralizing ability of bioactive glass and amorphous calcium phosphate casein phosphopeptide on early enamel lesion. Dent. Res. J. 2016, 13, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milly, H.; Festy, F.; Watson, T.F.; Thompson, I.; Banerjee, A. Enamel white spot lesions can remineralise using bio-active glass and polyacrylic acid-modified bio-active glass powders. J. Dent. 2014, 42, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, Z.; Jianyan, Q.; Min, G.; Hongyan, Z.; Jue, W.; Yufeng, M. Effects of 45S5 bioactive glass on the remineralization of early carious lesions in deciduous teeth: An in vitro study. BMC Oral Health 2021, 21, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavassoli-Hojjati, S.; Atai, M.; Haghgoo, R.; Rahimian-Imam, S.; Kameli, S.; Ahmaian-Babaki, F.; Hamzeh, F.; Ahmadyar, M. Comparison of various concentrations of tricalcium phosphate nanoparticles on mechanical properties and remineralization of fissure sealants. J. Dent. 2014, 11, 379. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.J.; Mo, S.Y.; Kim, D.S. Effect of bioactive glass-containing light-curing varnish on enamel remineralization. Materials 2021, 14, 3745. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, S.; Farooq, I.; Al-Thobity, A.M.; Al-Khalifa, K.S.; Alhooshani, K.; Sauro, S. An in-vitro evaluation of fluoride content and enamel remineralization potential of two toothpastes containing different bioactive glasses. Bio-Med. Mater. Eng. 2020, 30, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, R.; De Ataide, I.D.N.; Fernandes, M.; Lambor, R. Assessment of enamel remineralisation after treatment with four different remineralising agents: A scanning electron microscopy (SEM) study. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2017, 11, ZC136–ZC141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajan, R.; Krishnan, R.; Bhaskaran, B.; Kumar, S.V. A polarized light microscopic study to comparatively evaluate four remineralizing agents on enamel viz CPP-ACPF, ReminPro, SHY-NM and colgate strong teeth. Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2015, 8, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinelatti, M.A.; Tirapelli, C.; Corona, S.A.M.; Jasinevicius, R.G.; Peitl, O.; Zanotto, E.D.; Pires-de-Souza, F.D.C.P. Effect of a bioactive glass ceramic on the control of enamel and dentin erosion lesions. Braz. Dent. J. 2017, 28, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, I.S.; Kim, H.J.; Kwon, J.; Kim, D.S. Comparative In Vitro Study of Sol–Gel-Derived Bioactive Glasses Incorporated into Dentin Adhesives: Effects on Remineralization and Mechanical Properties of Dentin. J. Funct. Biomater. 2025, 16, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Boyes, V.; Festy, F.; Lynch, R.J.; Watson, T.F.; Banerjee, A. In-vitro subsurface remineralisation of artificial enamel white spot lesions pre-treated with chitosan. Dent. Mater. 2018, 34, 1154–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fallahzadeh, F.; Nouri, F.; Rashvand, E.; Heidari, S.; Najafi, F.; Soltanian, N. Enamel changes of bleached teeth following application of an experimental combination of chitosan-bioactive glass. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montaser, M.; Youssef, H.; Mahmoud, G.M. Remineralization of Decalcified Enamel in Primary Teeth via a New Bioactive Glass Paste:-An In Vitro Study. Alex. Dent. J. 2025, 50, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mareddy, A.R.; Reddy, V.N.; Done, V.; Rehaman, T.; Gadekar, T.; Raj, M. Comparative Evaluation of Three Remineralization Agents—Bioactive Glass, Nanohydroxyapatite and Casein Phosphopeptide-amorphous Calcium Phosphate Fluoride-based Slurry on Enamel Erosion of Primary Teeth: An In Vitro Study. Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2025, 18, 425. [Google Scholar]

- Poopirom, C.; Yimcharoen, V.; Rirattanapong, P. Comparative Analysis of Application of Fluoride Bioactive Glass and Sodium Fluoride Toothpastes for Remineralization of Primary Tooth Enamel Lesions. J. Int. Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 2025, 15, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safaee, S.; Nesabi, M.; Abe, S.; Harada, K.; Watanabe, I.; Murata, H. Effect of a novel bioactive glass synthesized by sol-gel method on restoring primary damage of enamel. Next Mater. 2025, 8, 100867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abozaid, D.; Azab, A.; Bahnsawy, M.A.; Eldebawy, M.; Ayad, A.; Soomro, R.; Elwakeel, E.; Mohamed, M.A. Bioactive restorative materials in dentistry: A comprehensive review of mechanisms, clinical applications, and future directions. Odontology 2025, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, S.; Iftikhar, N.; Agramonte, E.C.; Sur, D. The Role of Bioactive Glasses in Modern Dentistry: From Remineralization to Regeneration. Saudi J. Oral Dent. Res. 2025, 10, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hench, L.L.; Polak, J.M. Third-generation biomedical materials. Science 2002, 295, 1014–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, R.T.; Yang, J.; Ameer, G.A. Citrate-based biomaterials and their applications in regenerative engineering. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 2015, 45, 277–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alreshidi, S. Evaluation of Ion Release, Antibacterial characteristics, and Optical Properties of Newly Formulated Dental Composites with Zinc-Containing Glass Fillers. Ph.D. Thesis, Queen Mary University of London, London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ibadi, A.F.K.; Saud, A.N.; Incesu, A. Incorporation of B and V oxides into bioactive glass by melt quenching: In vitro studies for bone regeneration applications. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2025, 329, 130096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergi, R.; Bellucci, D.; Cannillo, V. A review of bioactive glass/natural polymer composites: State of the art. Materials 2020, 13, 5560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Par, M.; Plančak, L.; Ratkovski, L.; Tauböck, T.T.; Marovic, D.; Attin, T.; Tarle, Z. Improved flexural properties of experimental resin composites functionalized with a customized low-sodium bioactive glass. Polymers 2022, 14, 4289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizwan, M.; Hamdi, M.; Basirun, W.J. Bioglass® 45S5-based composites for bone tissue engineering and functional applications. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2017, 105, 3197–3223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simila, H.O.; Boccaccini, A.R. Sol-gel synthesis of lithium doped mesoporous bioactive glass nanoparticles and tricalcium silicate for restorative dentistry: Comparative investigation of physico-chemical structure, antibacterial susceptibility and biocompatibility. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1065597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Zhang, J.; Deng, S.; Su, Y.; Liu, S.; Liu, L.; Gao, S. Novel nanostructured RegeSi bioactive glass for early enamel caries remineralization: Multi-dimensional evaluation from microstructure to mechanical properties. Dent. Mater. 2025, 41, 1298–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, P.M.; Neves, A.D.A.; Makeeva, I.M.; Schwendicke, F.; Faus-Matoses, V.; Yoshihara, K.; Banerjee, A.; Sauro, S. Contemporary restorative ion-releasing materials: Current status, interfacial properties and operative approaches. Br. Dent. J. 2020, 229, 450–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Wang, Z.; Long, S.; Li, Y.; Yang, D. The advancement of nanosystems for drug delivery in the prevention and treatment of dental caries. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1546816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Špiljak, B.; Škoc, M.S.; Meštrović, I.R.; Bašić, K.; Bando, I.; Šutej, I. Targeting the Oral Mucosa: Emerging Drug Delivery Platforms and the Therapeutic Potential of Glycosaminoglycans. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, A.W.; Talley, N.J.; Walker, M.M.; Storm, G.; Hua, S. Current status and advances in esophageal drug delivery technology: Influence of physiological, pathophysiological and pharmaceutical factors. Drug Deliv. 2023, 30, 2219423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, P.D. Dental plaque as a biofilm and a microbial community–implications for health and disease. BMC Oral Health 2006, 6 (Suppl. 1), S14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Exterkate, R.A.; Mazurel, D.; Deng, D. Multispecies Oral Biofilm Models. In Oral Biofilms in Health and Disease; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 425–453. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, J.; Clare, A. (Eds.) Bio-Glasses: An Introduction; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Monfared, M.; Taghizadeh, S.; Zare-Hoseinabadi, A.; Mousavi, S.M.; Hashemi, S.A.; Ranjbar, S.; Amani, A.M. Emerging frontiers in drug release control by core–shell nanofibers: A review. Drug Metab. Rev. 2019, 51, 589–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohabatpour, F.; Chen, X.; Papagerakis, S.; Papagerakis, P. Novel trends, challenges and new perspectives for enamel repair and regeneration to treat dental defects. Biomater. Sci. 2022, 10, 3062–3087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionysopoulos, D. The Role of Bioactive Glasses in Dental Erosion―A Narrative Review. Compounds 2024, 4, 442–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Chen, X.; Pedone, A.; Apperley, D.; Hill, R.G.; Karpukhina, N. New insight into mixing fluoride and chloride in bioactive silicate glasses. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, M.; Kenny, C.; Chen, X.; Karpukhina, N.; Hill, R.G. Novel fluoride-and chloride-containing bioactive glasses for use in air abrasion. J. Dent. 2022, 125, 104252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliverio, R.; Patenaude, V.; Liberelle, B.; Virgilio, N.; Banquy, X.; De Crescenzo, G. Macroporous dextran hydrogels for controlled growth factor capture and delivery using coiled-coil interactions. Acta Biomater. 2022, 153, 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaou, M.H.; Furkó, M.; Balázsi, K.; Balázsi, C. Advanced bioactive glasses: The newest achievements and breakthroughs in the area. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaure, P.C.; Grumezescu, A.M. Recent advances in surface nanoengineering for biofilm prevention and control. Part II: Active, combined active and passive, and smart bacteria-responsive antibiofilm nanocoatings. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galarraga-Vinueza, M.E.; Passoni, B.; Benfatti, C.A.M.; Mesquita-Guimarães, J.; Henriques, B.; Magini, R.S.; Fredel, M.C.; Meerbeek, B.V.; Teughels, W.; Souza, J.C.M. Inhibition of multi-species oral biofilm by bromide doped bioactive glass. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2017, 105, 1994–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unkovskiy, A.; Spintzyk, S.; Beuer, F.; Huettig, F.; Röhler, A.; Kraemer-Fernandez, P. Accuracy of capturing nasal, orbital, and auricular defects with extra-and intraoral optical scanners and smartphone: An in vitro study. J. Dent. 2022, 117, 103916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X. Novel Halide Containing Bioactive Glasses. Ph.D. Thesis, Queen Mary University of London, London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pitts, N.B.; Ekstrand, K.R.; ICDAS Foundation. International Caries Detection and Assessment System (ICDAS) and its International Caries Classification and Management System (ICCMS)–methods for staging of the caries process and enabling dentists to manage caries. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2013, 41, e41–e52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raszewski, Z.; Chojnacka, K.; Mikulewicz, M. Investigating bioactive-glass-infused gels for enamel remineralization: An in vitro study. J. Funct. Biomater. 2024, 15, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taha, A.A.; Patel, M.P.; Hill, R.G.; Fleming, P.S. The effect of bioactive glasses on enamel remineralization: A systematic review. J. Dent. 2017, 67, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| BG Type | Composition | Surface Morphology Change (SEM/EDS Findings) | Functional/Clinical Implication | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bioglass® 45S5 | 45% SiO2, 24.5% Na2O, 24.5% CaO, 6% P2O5 |

| Promotes rapid osteoblast adhesion, spreading, and extracellular matrix production, leading to mineralized nodule formation, relevant for strong interfacial bonding in dental and orthopedic applications. | [44] |

| Calcium phosphate–modified BG | Dicalcium phosphate dihydrate (DCPD) + trace HA, compared to 45S5 BG |

| Rapid and uniform apatite layer formation; improved mineral deposition compared to conventional BG, supporting potential use in enhanced enamel/dentin remineralization. | [45] |

| Zinc-dopted BG | Sol–gel derived bioactive glass with Zn2+ substitution for Ca2+ (up to 5 mol%) | At 24 h, all groups show sparse silver deposition. After 3 months: control (SB2) displays extensive nanoleakage; SB2+5BGNs and SB2+5ZnBGNs show reduced silver uptake (less leakage); SB2+2.5ZnBGNs remain stable over time. | Zn-doped BGNs enhance remineralization at the adhesive–dentin interface, reduce nanoleakage, inhibit MMP activity, and provide antibacterial effects, improving bond durability and caries prevention. | [46] |

| Silver-doped nanostructured bioglass (nBG-Ag) resin sealant | Sol–gel synthesized Ca–Si–P bioglass nanoparticles doped with Ag (3% or 5% w/w) dispersed in Bis-GMA/TEGDMA resin | Control shows honeycomb demineralization pattern; nBG-Ag shows hydroxyapatite (HA) crystal deposits masking enamel prisms. EDAX confirms Ca, P, Si, and Ag in the deposited layer. | Seals enamel and promotes Ca/P deposition (HA). 5% nBG-Ag significantly reduces S. mutans vs. 3% and control, supporting anti-caries action around orthodontic brackets; durability maintained (no DC penalty). | [47] |

| strontium-doped BG and fluoride | Experimental strontium-containing bioactive glass-ceramic (HX-BGC); HX-BGC with fluoride addition (HX-BGC+F); fluoride glass (F); compared against water control |

| Sr promotes apatite nucleation, while F stabilizes fluorapatite. The combined Sr+F BG produces the most effective tubule sealing and collagen protection, enhancing remineralization, improving acid resistance, and reducing dentin hypersensitivity compared to Sr- or F-only BG. | [48] |

| F fluoride-containing BG | SiO2–P2O5–CaO–SrO–Na2O–CaF2 incorporated into BisGMA–TEGMA resin | SEM shows a reacted glass layer and surface apatite deposition. Apatite formation is more pronounced under neutral saliva (AS7) than acidic saliva (AS4). FTIR confirmed apatite bands at 560–600 cm−1. | Fluoride incorporation promotes FA formation, enhances acid resistance, and supports remineralization. Despite reduced strength after immersion, silylated composites maintain clinically acceptable properties. | [38] |

| NovaMin | Multi-component bioactive glass containing Si, Ca, Na, P (commercial formulation; widely known in the literature as Calcium Sodium Phosphosilicate, CSPS) |

| Restores enamel microhardness, enhances remineralization, protects against caries progression in primary teeth. | [40] |

| Case No. | Material Used | Target Lesion | Model Type | Application Method | Evaluation Techniques | Key Findings | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | Bioactive glass (BAG) & Sodium fluoride (bioerodible gel films) | Artificial caries lesions | In vitro, primary maxillary incisors | Topical gel films applied interproximally for 30 days | Polarized light microscopy, lesion area quantification | Both BAG and NaF films significantly enhanced remineralization vs. controls | [58] |

| 4 | Bioactive glass (Novamin, Sensodyne Repair and Protect) and ACP-CPP (GC Tooth Mousse) | Early enamel lesions (acid-induced) | In vitro, human mandibular premolars | Daily topical application for 10–15 days, stored in saliva | Vickers microhardness test | Bioactive glass showed significantly faster remineralization at 10 days compared with ACP-CPP, but by 15 days both materials demonstrated similar remineralization potential. | [59] |

| 9 | BAG powder and BAG containing polyacrylic acid (PAA-BAG) | WSLs | In vitro, human enamel samples | BAG or PAA-BAG slurry applied; compared with remineralization solution (positive control) and deionized water (negative control) | Surface and cross-section Knoop microhardness, Micro-Raman spectroscopy, White light profilometry, SEM | BAG and PAA-BAG significantly improved mechanical properties, increased phosphate content, and showed mineral deposition within lesions. However, lesion depth was not significantly reduced. | [60] |

| 1 | 45S5 BAG suspensions (2%, 4%, 6%, 8%) | Early carious lesions (artificial) in deciduous enamel | In vitro, human deciduous teeth | 14-day pH-cycling with twice-daily BAG suspension application | Vickers microhardness, SEM with EDX, FT-IR/ATR | BAG significantly enhanced remineralization compared with control. The 6% BAG group achieved the highest microhardness recovery, densest mineral deposition, and formation of hydroxycarbonate apatite | [61] |

| 16 | β-tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP) nanoparticles (1–5 wt%) incorporated into fissure sealant | Enamel adjacent to fissure sealant restorations | In vitro, human premolars | Fissure sealant with varying β-TCP concentrations applied to prepared cavities | Flexural strength, Micro-shear bond strength, SEM-EDX | Addition of 1–5 wt% β-TCP nanoparticles significantly enhanced formation of an intermediate remineralized layer at the enamel–sealant interface, with increasing thickness at higher concentrations, while mechanical properties (flexural strength, micro-shear bond strength) were not adversely affected. | [62] |

| 3 | Biosilicate; Acidulated Phosphate Fluoride—APF; Untreated—control | Artificial erosive and carious lesions | In vitro, bovine enamel and dentin blocks | Daily topical application of Biosilicate® or APF solutions for 10 days | Surface microhardness, 3D profilometry, Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM) | Both Biosilicate® and APF significantly reduced surface loss and demineralization compared with control. Biosilicate® was effective in both enamel and dentin, though APF performed better in enamel. | [63] |

| 2 | Novamin® (bioactive glass toothpaste) and BiominF® (fluoride-containing bioactive glass toothpaste) | Artificially demineralized human enamel (citric acid, pH 2.2) | In vitro, enamel blocks | 24 h storage in artificial saliva with added toothpaste slurry | Fluoride ion selective electrode (TF/TSF), Vickers microhardness | Both toothpastes had lower fluoride than label claims. BiominF® contained significantly more fluoride than Novamin® and produced higher enamel microhardness recovery, showing greater remineralization potential. | [64] |

| 6 | (1) CPP-ACPF, Tooth Mousse Plus (2)BAG, SHY-NM (3) Fluoride-enhanced hydroxyapatite gel (ReminPro) (4) Self-assembling peptide P11-4 (Curodont Protect) | Artificial enamel carious lesions | In vitro, human enamel samples | Topical application during 30-day pH cycling model | Surface microhardness, SEM | Self-assembling peptide P11-4 achieved the greatest remineralization, significantly outperforming BAG and HA gel, and comparable to CPP-ACPF. CPP-ACPF also showed strong remineralizing ability, followed by BAG and HA gel | [65] |

| 5 | SHY-NM® (bioactive glass, calcium sodium phosphosilicate); GC Tooth Mousse Plus® (CPP-ACPF); ReminPro® (hydroxyapatite + fluoride + xylitol); Colgate Strong Teeth® (fluoridated toothpaste, 1000 ppm F) | Artificial caries, extracted human premolars | In vitro, human enamel | Topical application, 20-day pH cycling | Polarized light microscopy, lesion depth analysis with ImageJ | SHY-NM demonstrated the highest remineralizing potential, followed by ReminPro, CPP-ACPF, and fluoridated toothpaste, with statistically significant superiority of SHY-NM. | [66] |

| 8 | Biosilicate® (bioactive glass-ceramic); Acidulated Phosphate Fluoride (APF); untreated control | Artificial erosive and caries-like lesions (bovine enamel and dentin) | In vitro | Daily topical application during erosive cycles (1–21 days) and caries pH cycling (14 days) | 3D optical profilometry, Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM), surface and cross-sectional Knoop microhardness | Biosilicate significantly reduced surface loss in enamel and dentin and provided higher surface and subsurface microhardness than APF and control. APF reduced demineralization compared with control but was less effective than Biosilicate. | [67] |

| 15 | Sol–gel-derived BGs (BAG79, BAG87, BAG91, BAG79F) and conventional melt-quenched BAG45, incorporated into dentin adhesives | Demineralized dentin | In vitro, human dentin specimens | Experimental dentin adhesives containing BAG applied to demineralized dentin surfaces | FE-SEM, TEM, BET surface area analysis, XRD, elastic modulus measurement |

| [68] |

| 10 | Chitosan-bioactive glass (CH-BG) compared with MI Paste (CPP-ACP) and control | Bleached enamel | In vitro, human enamel specimens | Daily topical application of CH-BG or MI Paste for 14 days after bleaching | SEM-Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDX) |

| [69] |

| 11 | BioMin® bioactive glass toothpaste, fluoridated toothpaste, artificial saliva | Demineralized primary enamel | In vitro, primary teeth | Brushing twice daily for 15 days | Vickers microhardness, Polarized light microscopy | BioMin® significantly increased microhardness and reduced lesion depth more than fluoridated toothpaste or artificial saliva | [70] |

| 12 | Bioactive glass (BAG), nano-hydroxyapatite (nHAp), CPP-ACPF | Enamel erosion in primary teeth | In vitro, primary teeth | Topical application of BAG-, nHAp-, and CPP-ACPF-based slurries during pH-cycling | Vickers microhardness, SEM | All agents enhanced remineralization; nHAp showed highest microhardness, BAG also effective | [71] |

| 13 | BAG, nHAp, CPP-ACPF | Demineralized primary enamel | In vitro, primary enamel | topical slurry application during pH cycling (14 days). | Vickers microhardness, SEM | nHAp showed highest remineralization, followed by BAG; CPP-ACPF was less effective. | [72] |

| 14 | Fluoride bioactive glass (BioMin® F), sodium fluoride toothpastes (500–1500 ppm) | Artificial carious lesions in primary teeth | In vitro, human primary incisors | Brushing twice daily during 7-day pH cycling | Surface microhardness (%SMHR) | BioMin® F had remineralization comparable to 1500 ppm fluoride and outperformed 500/1000 ppm; effective and safer for children | [73] |

| 17 | Bioactive glass varnish, fluoride-containing BAG, nanosilver-containing BAG, nanosilver fluoride, fluoride, nanosilver, artificial saliva | White spot lesions | In vitro (human teeth) | Varnish applied with microbrush for 1 min, then stored in artificial saliva for 14 days | SEM, EDX (Ca/P ratio), Vickers microhardness, TEM, UV-vis spectroscopy | Nanosilver-containing BAG showed highest mineral gain (23.27%) and high hardness recovery; fluoride-containing BAG and nanosilver fluoride were similarly effective; BAG alone comparable to fluoride. Artificial saliva showed the least effect. | [39] |

| 18 | Synthesized bioactive glass (SiO2–CaO–P2O5–MgO–SrO) via sol–gel method, 20% aqueous suspension | Artificially demineralized enamel | In vitro (human third molars, sectioned) | Daily immersion in 20% BG suspension for 15 days at 37 °C (BG-treated group); others: natural and demineralized controls | XRD, ATR-FTIR, SEM, Vickers microhardness | Demineralization caused a 49.6% reduction in hardness; remineralized enamel showed a 22.35% increase. SEM confirmed BG particle deposition and HA formation. ATR-FTIR indicated enhanced mineral content. XRD showed no significant mineral phase change. | [74] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Farjaminejad, R.; Farjaminejad, S.; Garcia-Godoy, F.; Jalali, M. The Role of Bioactive Glasses in Caries Prevention and Enamel Remineralization. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 13157. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413157

Farjaminejad R, Farjaminejad S, Garcia-Godoy F, Jalali M. The Role of Bioactive Glasses in Caries Prevention and Enamel Remineralization. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):13157. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413157

Chicago/Turabian StyleFarjaminejad, Rosana, Samira Farjaminejad, Franklin Garcia-Godoy, and Mahsa Jalali. 2025. "The Role of Bioactive Glasses in Caries Prevention and Enamel Remineralization" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 13157. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413157

APA StyleFarjaminejad, R., Farjaminejad, S., Garcia-Godoy, F., & Jalali, M. (2025). The Role of Bioactive Glasses in Caries Prevention and Enamel Remineralization. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 13157. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413157