Structural Design and Analysis of Telescope for Gravitational Wave Detection in TianQin Program

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Structural Design and Analysis Preparation

2.1. The Structural Design Requirements

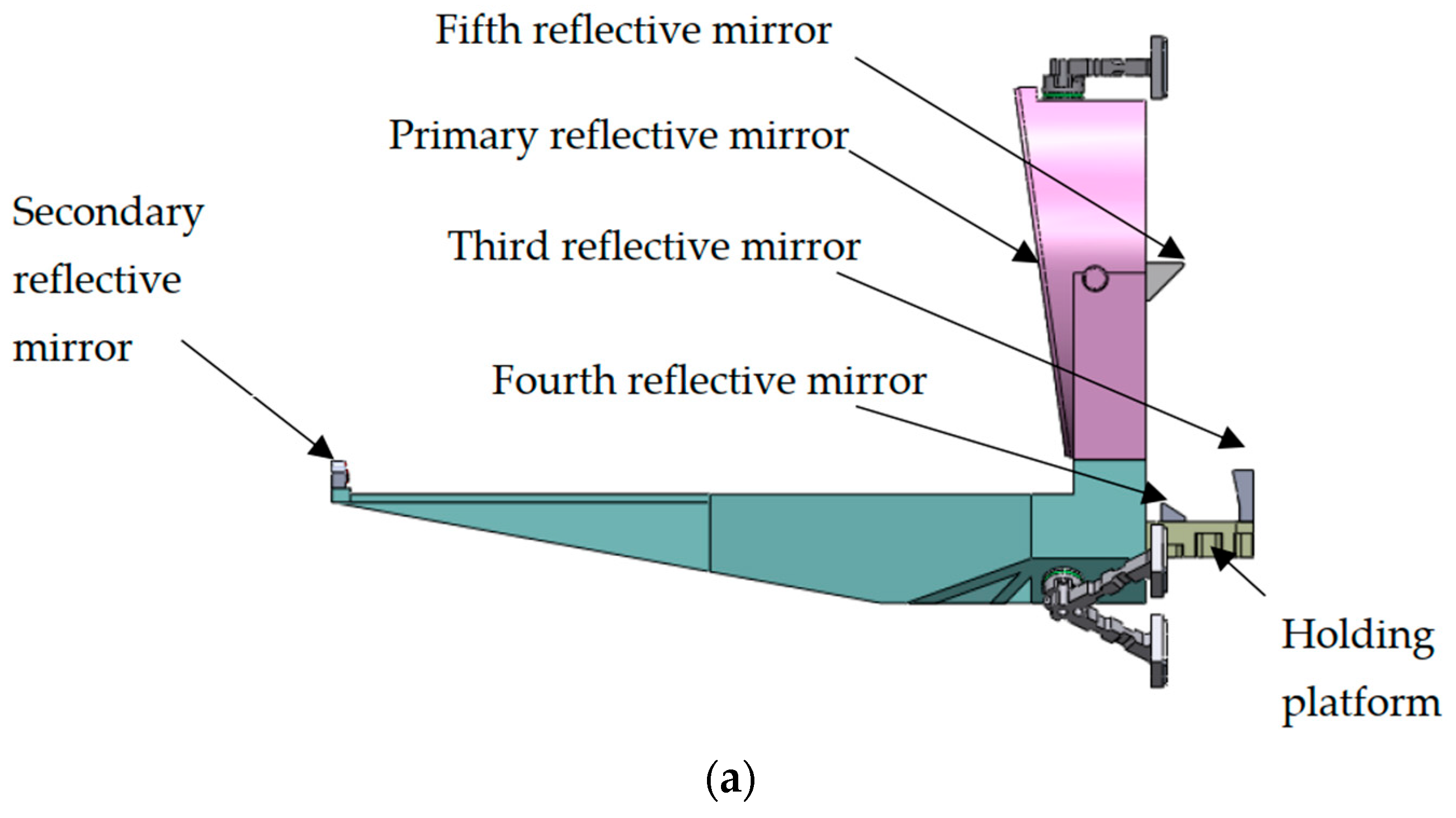

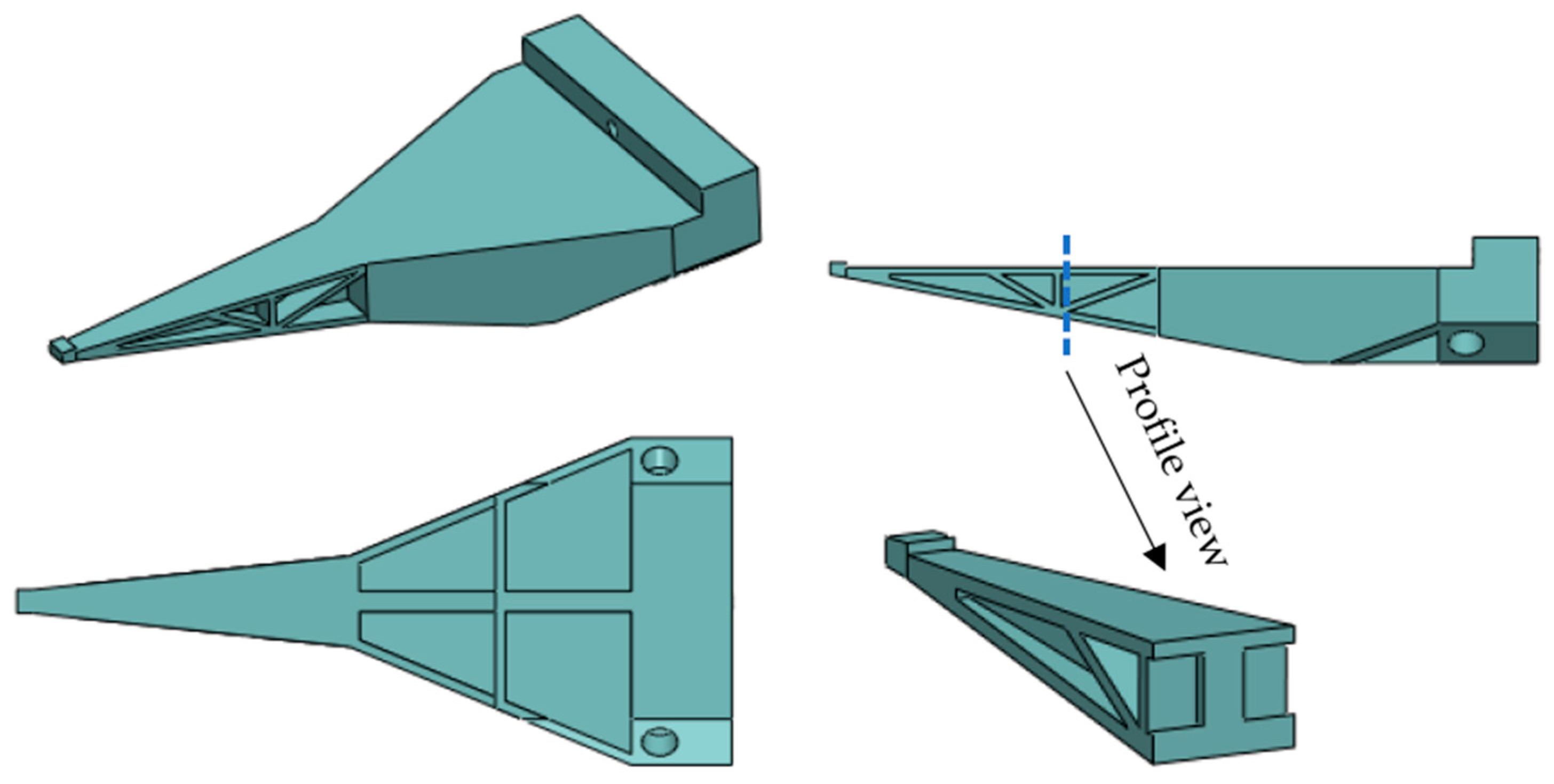

2.2. The Initial Structural Design

2.3. The Fundamental Theory of Mechanical Analysis

2.4. The Fundamental Theory of Hydroxide Catalysis Bonding

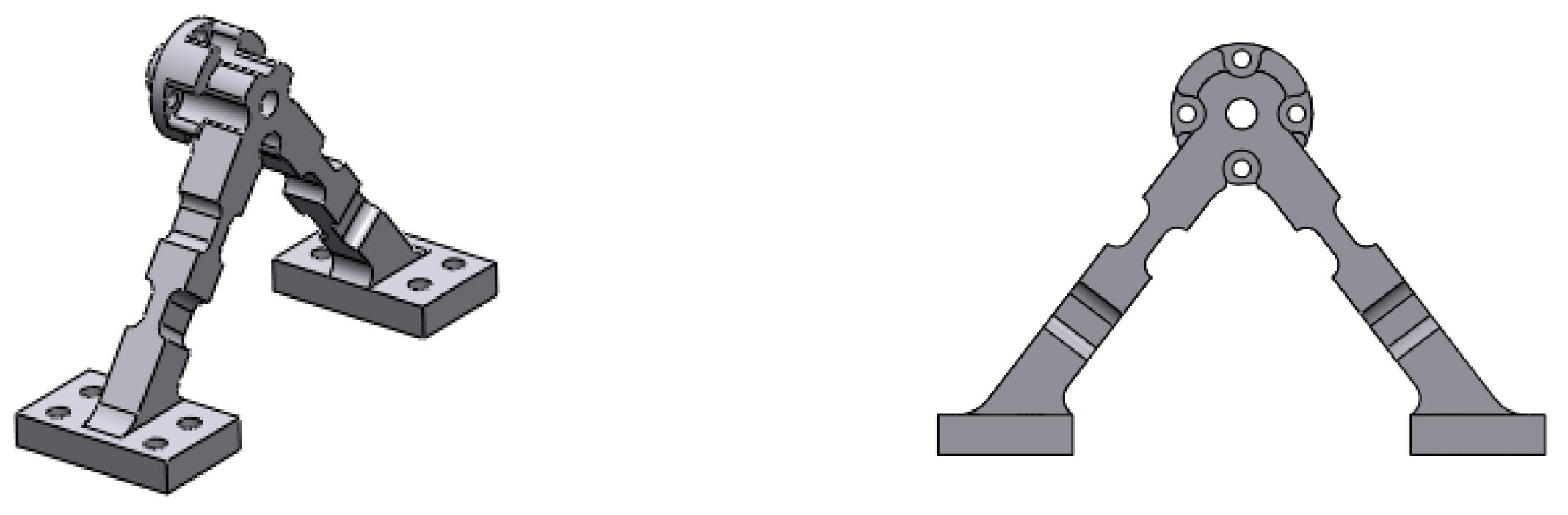

2.5. Improvement of the Initial Structural Design

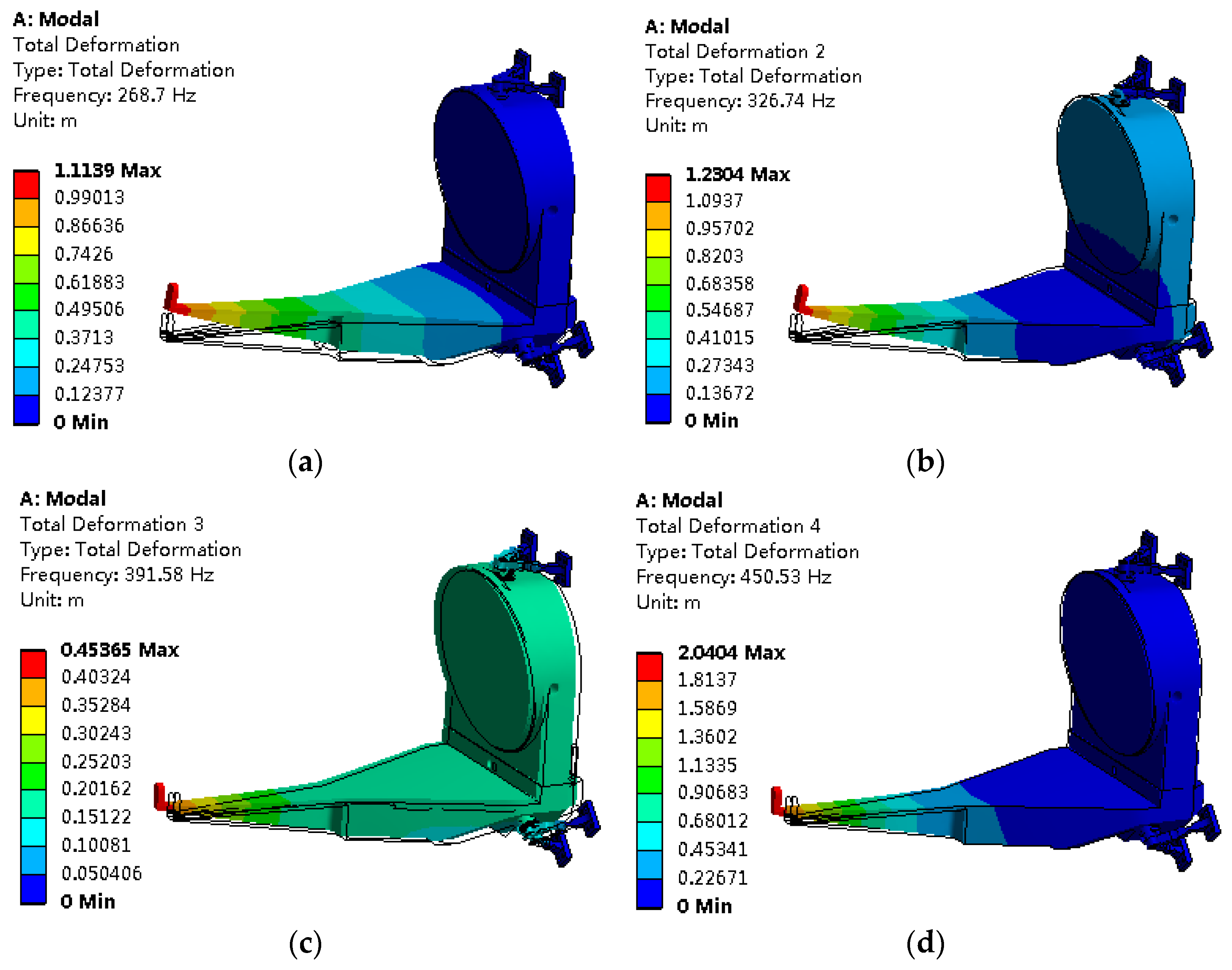

3. Structural Analysis of the Optimized Telescope

3.1. The Purpose of Structural Analysis

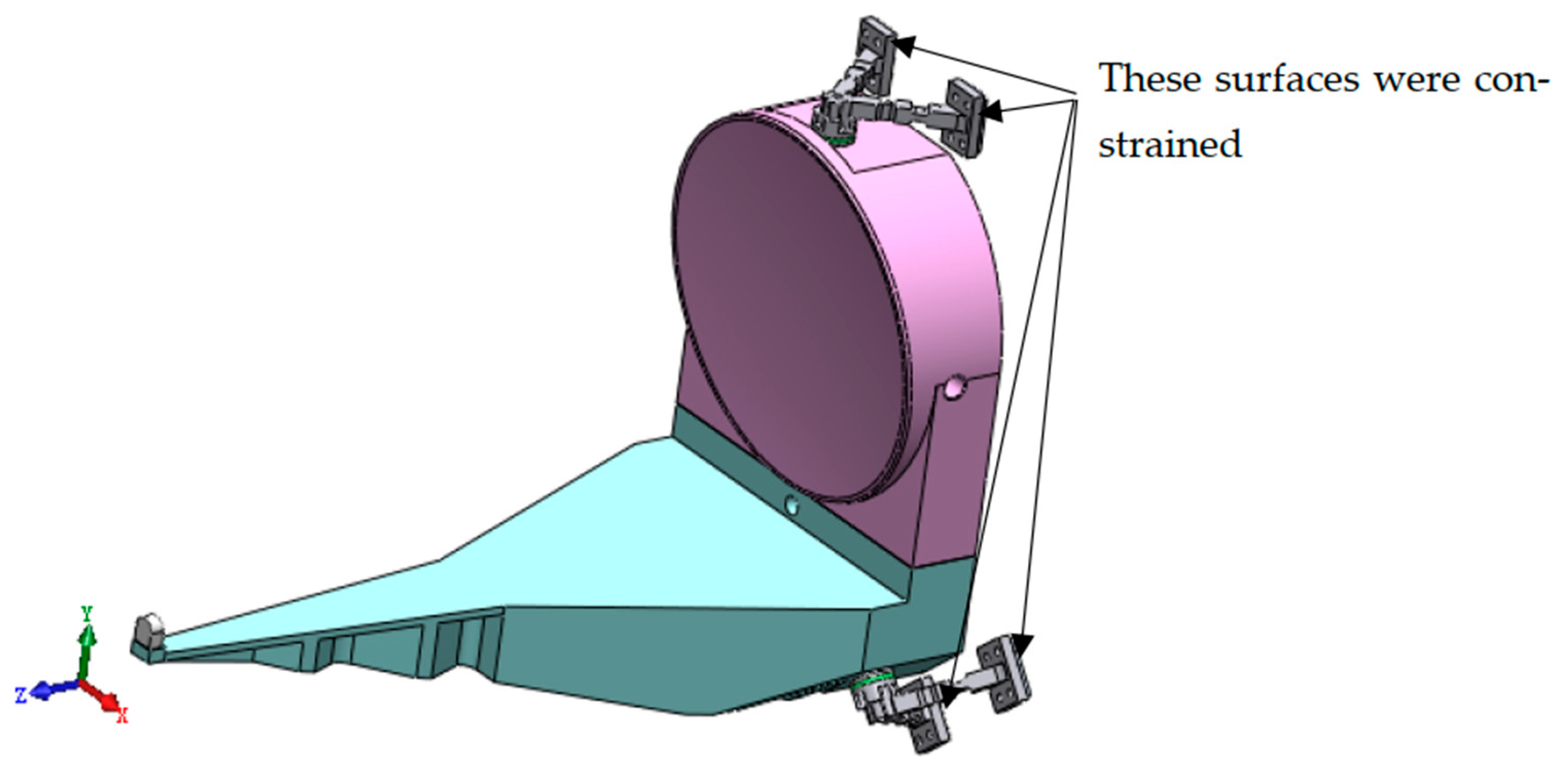

3.2. Some Information for Structural Analysis

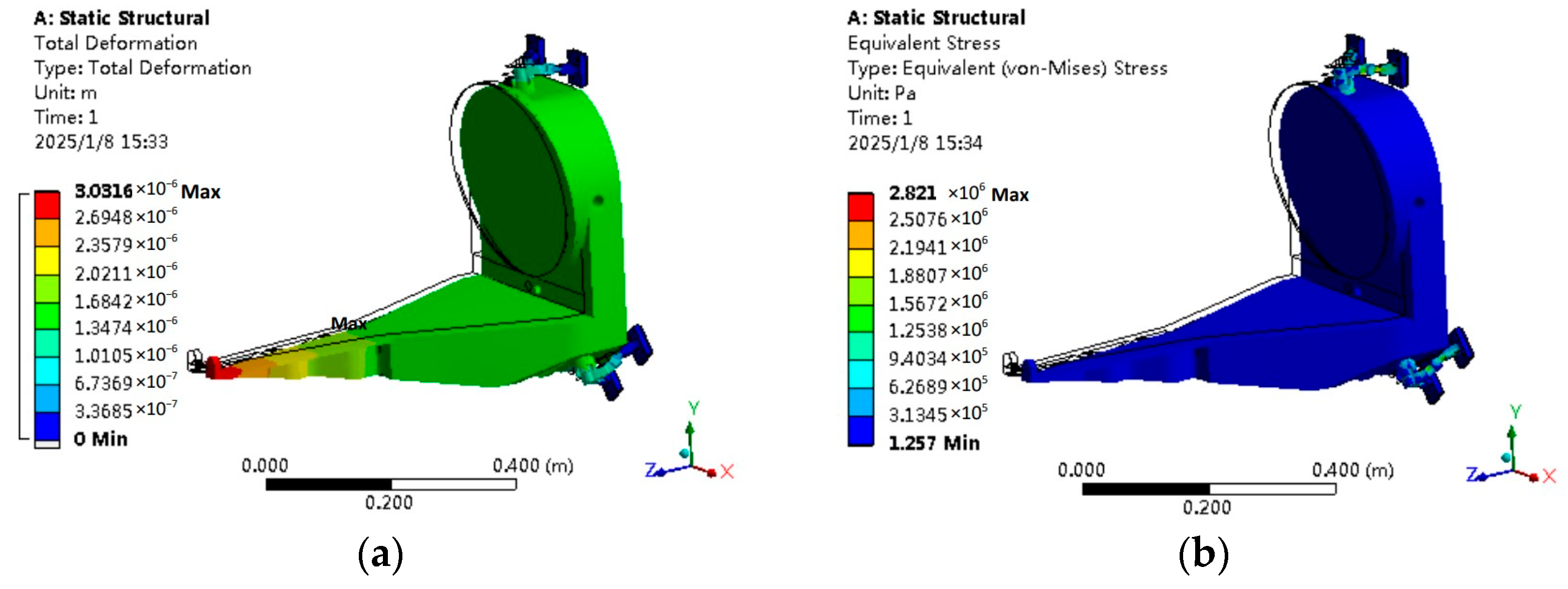

3.3. Static Analysis

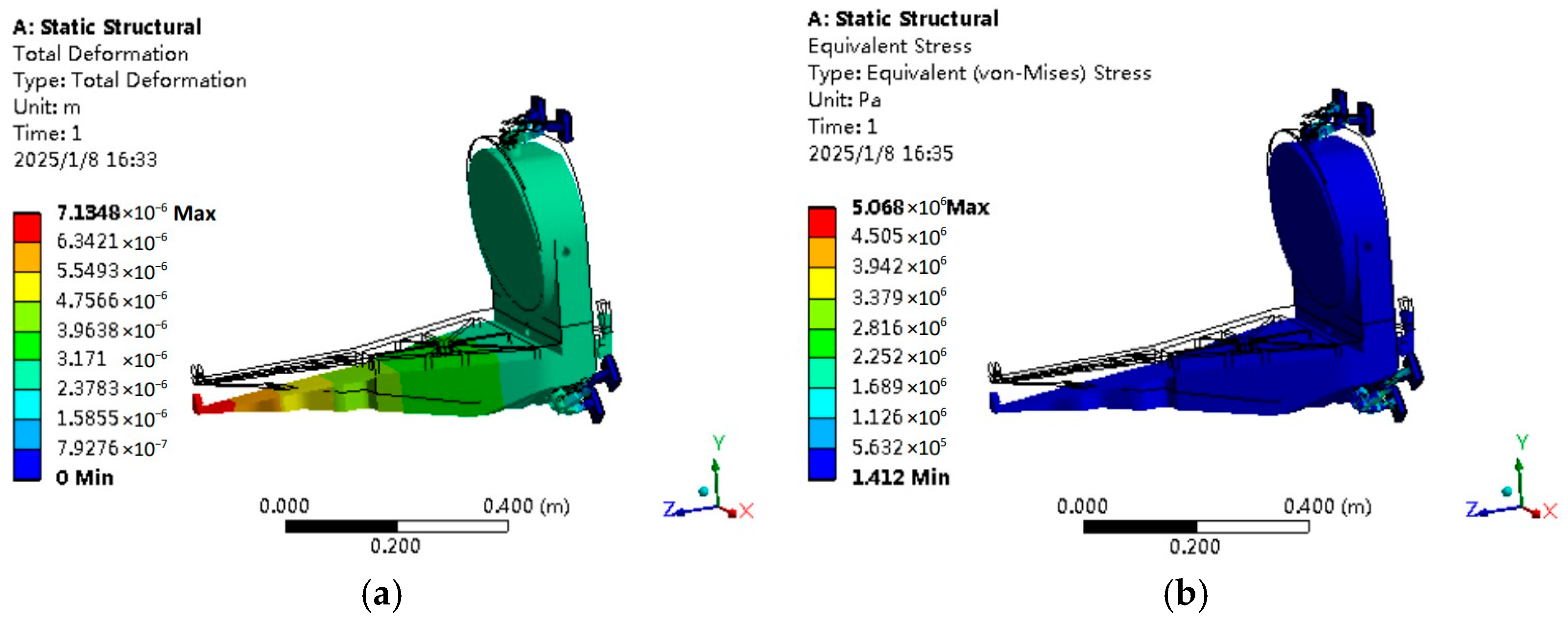

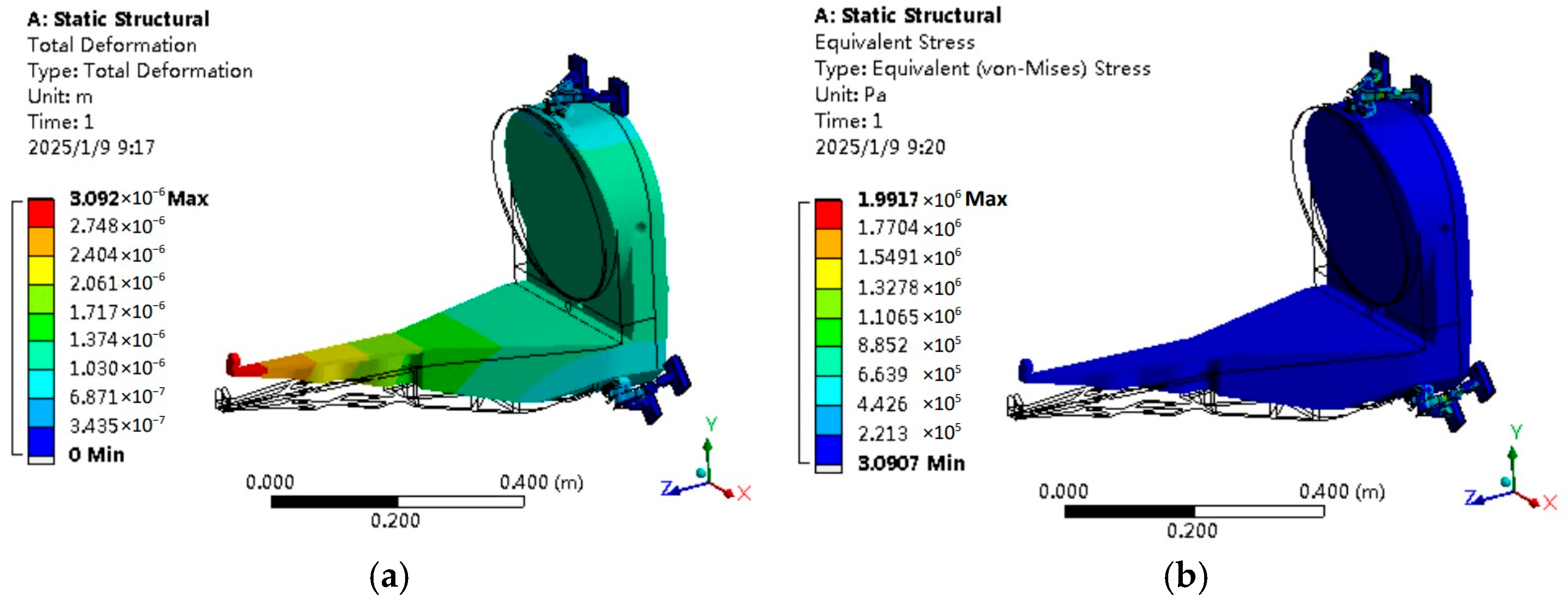

3.4. Thermal Analysis

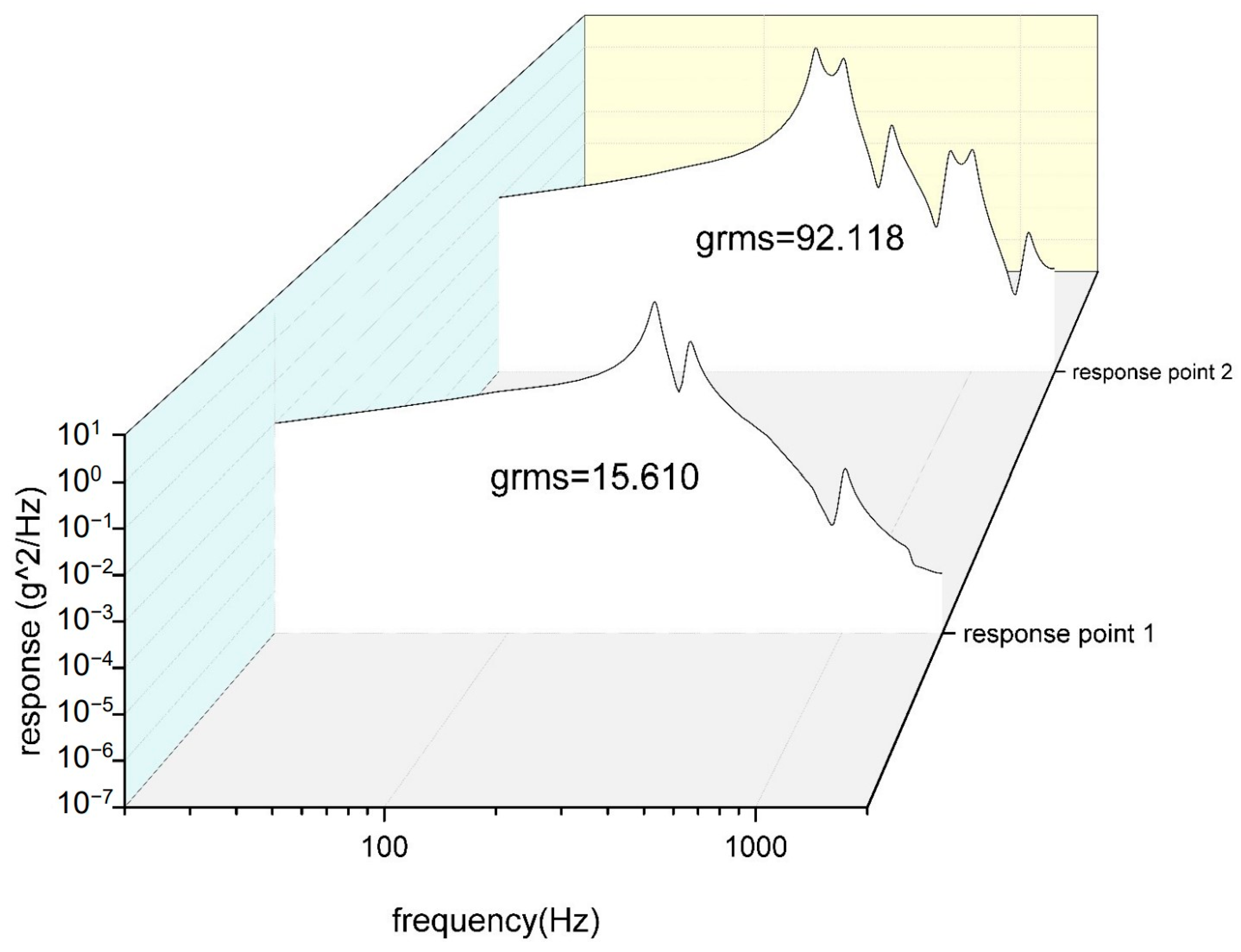

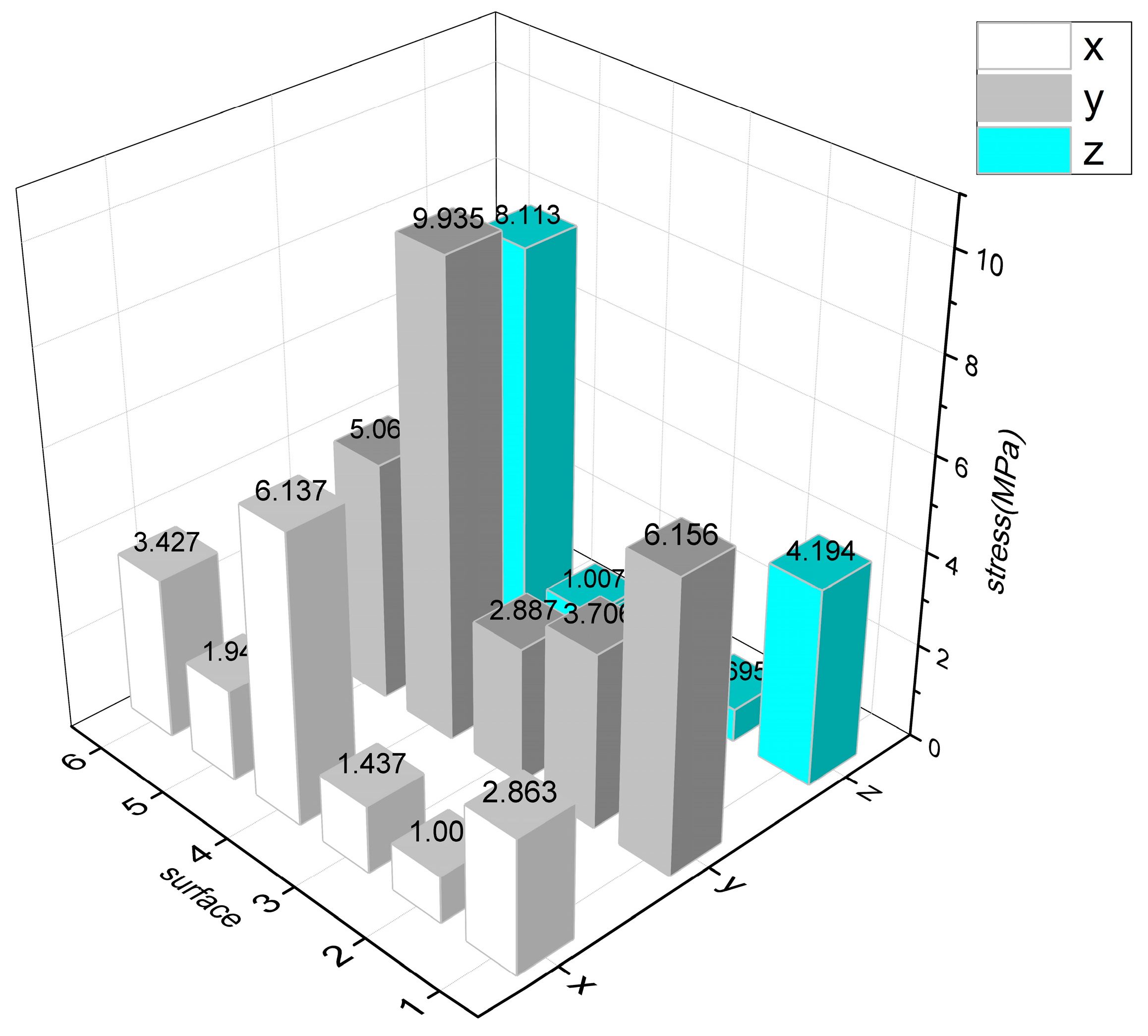

3.5. Random Vibration Analysis

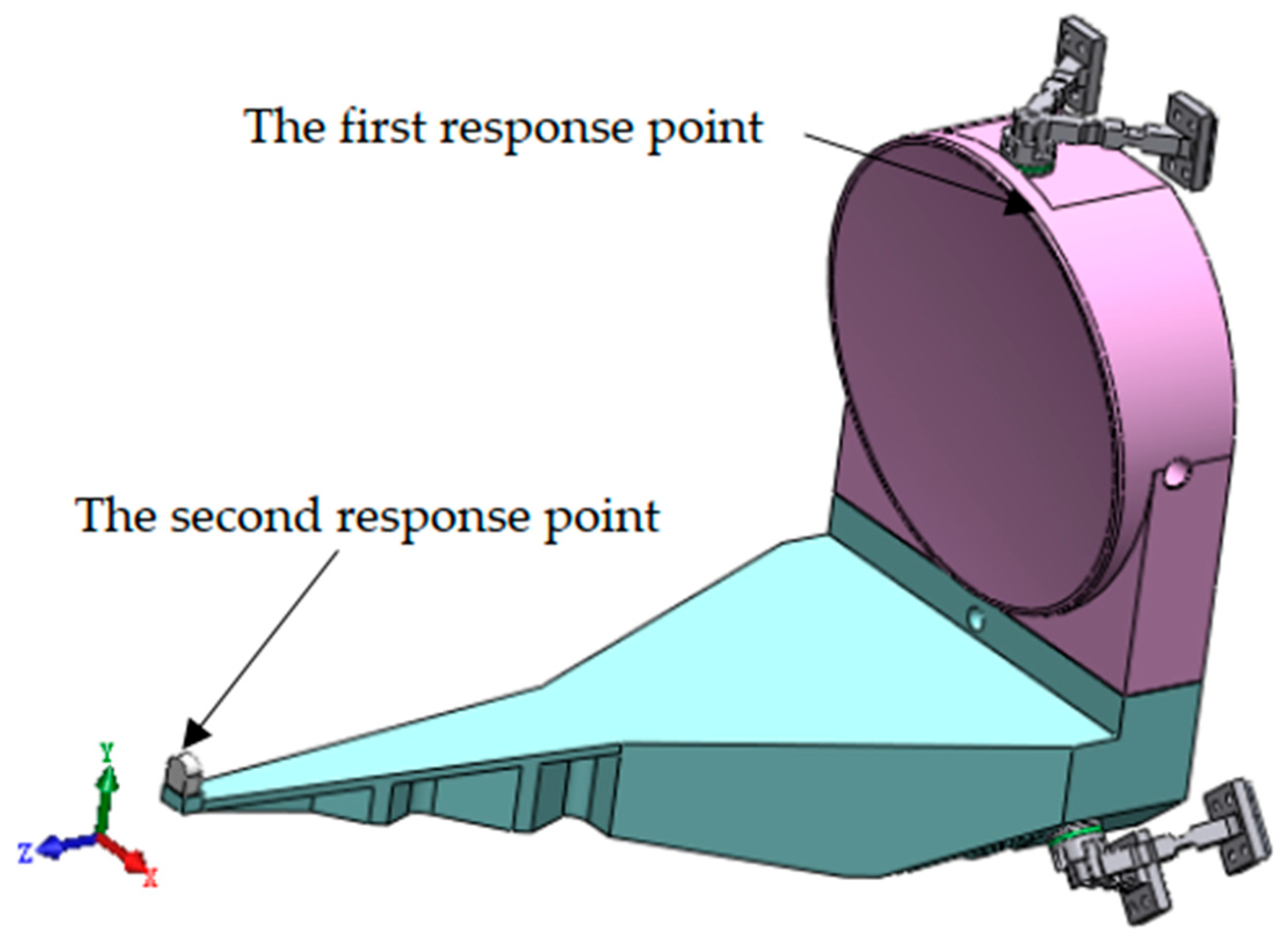

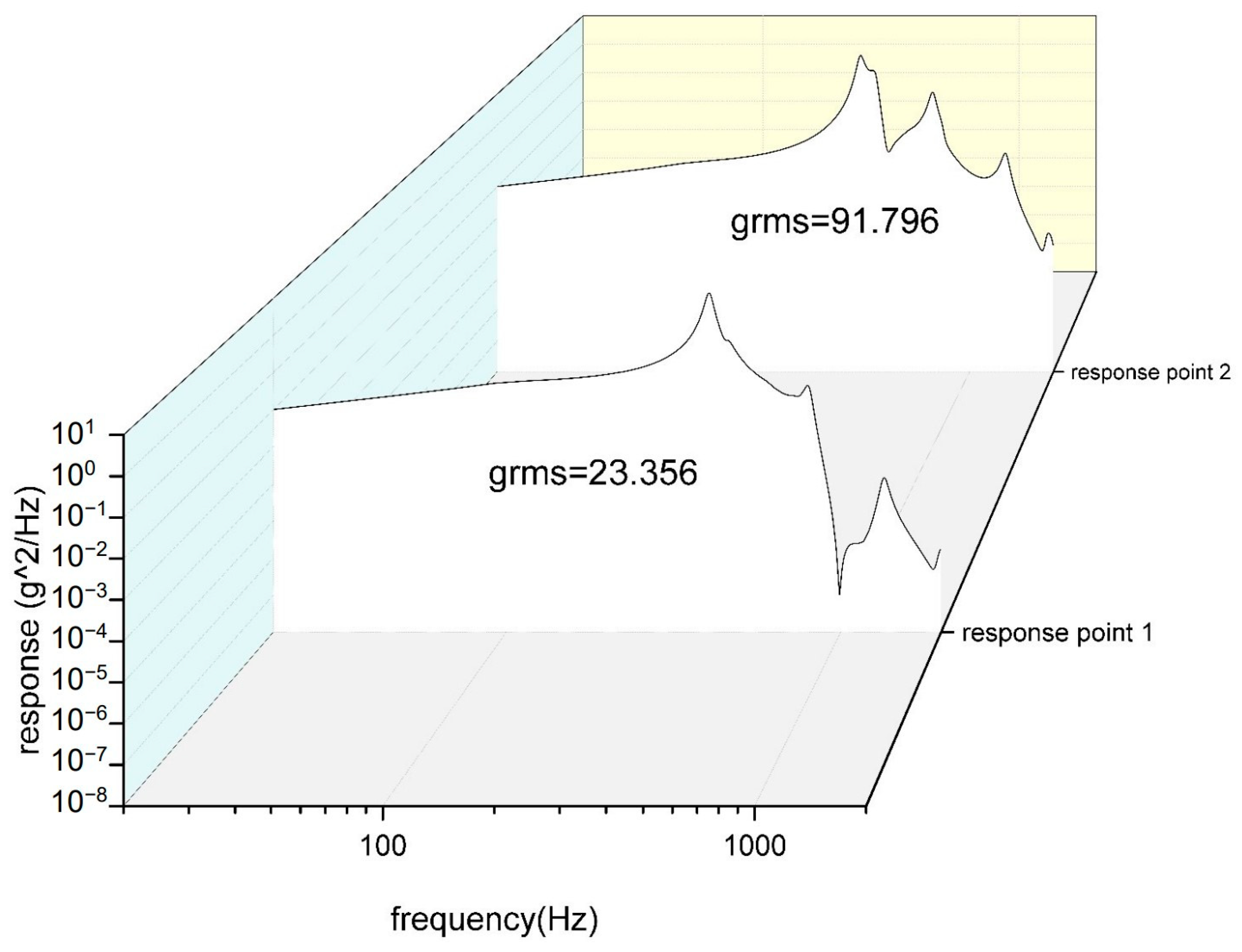

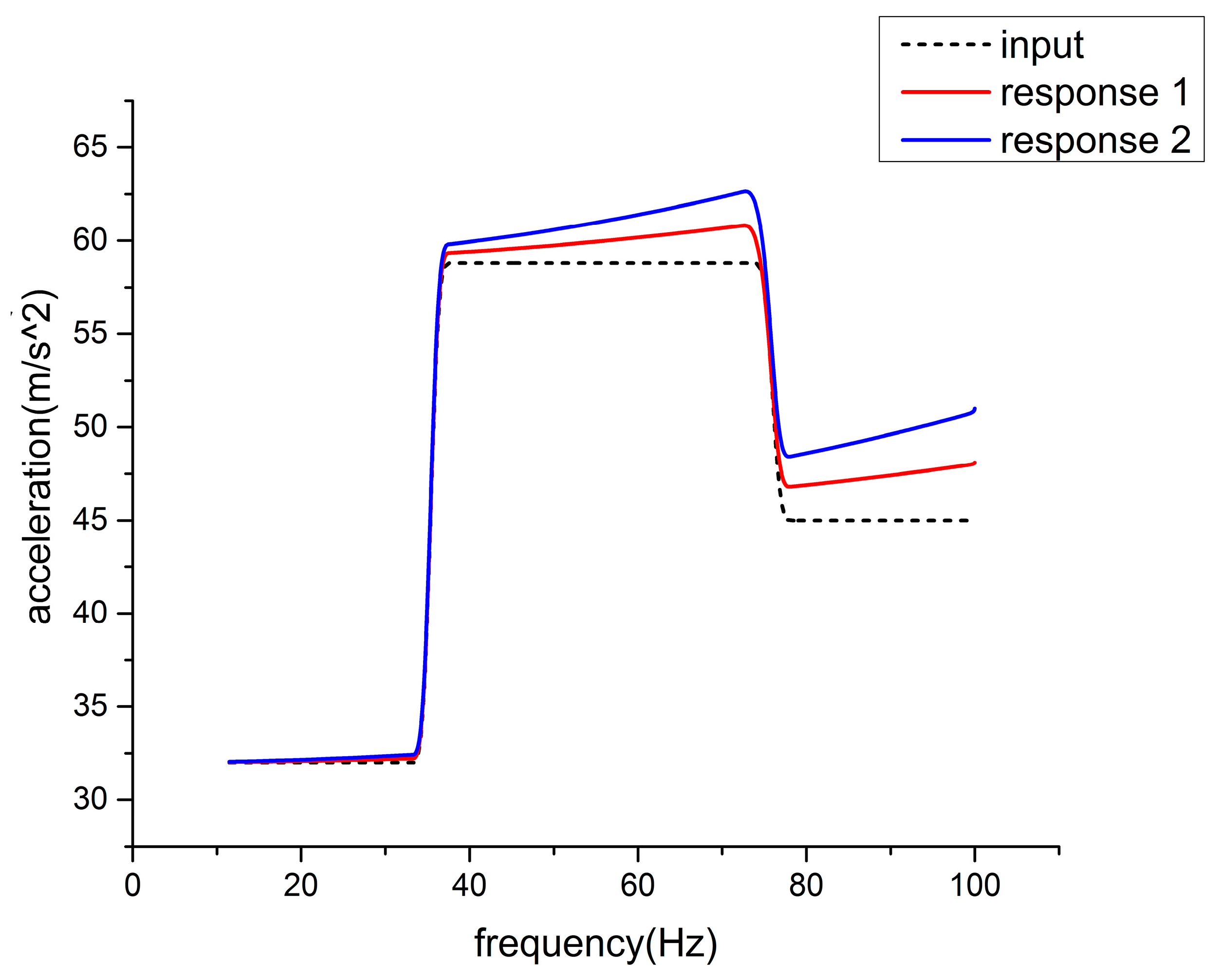

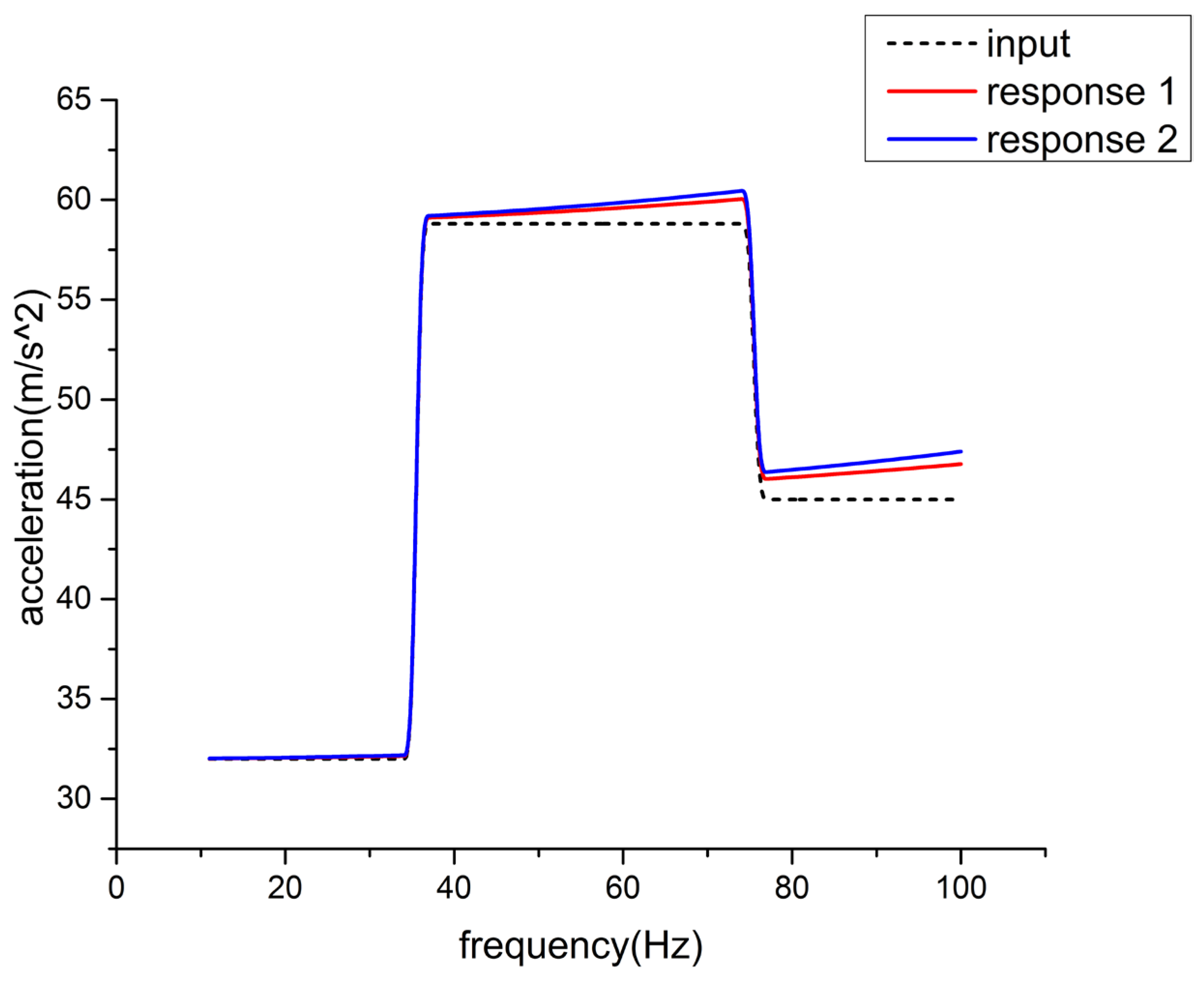

3.6. Sine Vibration Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LIGO | Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory |

| LISA | Laser Interferometer Space Antenna |

| ESA | European Space Agency |

| NASA | National Aeronautics and Space Administration |

| FEM | Finite Element Method |

| FE | Finite Element |

| PSD | Power spectral density |

| RMS | Root mean square |

| grms | Gravitational acceleration root mean square |

References

- A. Einstein, Sitzungsber. K. Preuss. Akad. Wiss. 1915. 844. Available online: https://adsabs.harvard.edu/pdf/1915SPAW.......844E (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- A. Einstein, Sitzungsber. K. Preuss. Akad. Wiss. 1916. 688. Available online: https://adsabs.harvard.edu/pdf/1916SPAW.......688E (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- A. Einstein, Sitzungsber. K. Preuss. Akad. Wiss. 1918. 154. Available online: https://adsabs.harvard.edu/pdf/1918SPAW.......154E (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Saulson, P.R. Josh Goldberg and the physical reality of gravitational waves. Gen. Relativ. Gravit. 2011, 43, 3289–3299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, F. The search for gravitational waves: An experimental physics challenge. Contemp. Phys. 1998, 39, 107–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hough, J.; Drever, R. Gravitational waves—A tough challenge. New Sci. 1978, 79, 464–467. [Google Scholar]

- Freise, A.; Strain, K. Interferometer Techniques for Gravitational-Wave Detection. Living Rev. Relativ. 2010, 13, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D. The Observation of Gravitational Waves from a Binary Black Hole Merger. Am. Phys. Soc. 2016, 116, 061102. [Google Scholar]

- Abbott, R.; Abbott, T.D.; Abraham, S.; Acernese, F.; Ackley, K.; Adams, A.; Adams, C.; Adhikari, R.X.; Adya, V.B.; Affeldt, C.; et al. GWTC-2: Compact Binary Coalescences Observed by LIGO and Virgo during the First Half of the Third Observing Run. Phys. Rev. X 2021, 11, 021053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Ligo Scientific Collaboration; Virgo Collaboration. GWTC-1: A Gravitational-Wave Transient Catalog of Compact Binary Mergers Observed by LIGO and Virgo during the First and Second Observing Runs. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1811.12907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conklin, J.; Cornish, N. LISA in the Gravitational Wave Decade. Bulletin of the American Physical Society (2015). Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/LISA-in-the-gravitational-wave-decade-Conklin-Cornish/6e53442340cf0ffa513b4c826694d962341e1cd0 (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Berti, E.; Cardoso, V.; Will, C.M. Gravitational-wave spectroscopy of massive black holes with the space inter-ferometer LISA. Phys. Rev. D Part Fields 2006, 73, 348–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweetser, T.H. An end-to-end trajectory description of the LISA mission. Class. Quantum Gravity 2005, 22, S429–S435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Li, G.; Heinzel, G.; Rüdiger, A.; Luo, Y. Orbit design for the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA). Sci. China Phys. Astron. 2010, 53, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Zhang, H. Formation flight design for a LISA-like gravitational wave observatory via Cascade optimization. Astrodynamics 2019, 3, 155–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danzmann, K. The LISA study team LISA: Laser interferometer space antenna for gravitational wave measurements. Class. Quantum Gravity 1996, 13, A247–A250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.R.; Wu, Y.L. The Taiji Program in Space for gravitational wave physics and the nature of gravity. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2017, 4, 685–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Chen, L.-S.; Duan, H.-Z.; Gong, Y.-G.; Hu, S.; Ji, J.; Liu, Q.; Mei, J.; Milyukov, V.; Sazhin, M.; et al. TianQin: A space-borne gravitational wave detector. Class. Quantum Gravity 2016, 33, 035010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Hu, W.; Jin, G. The Taiji program: A concise overview. Prog. Theor. Exp. Phys. 2021, 2021, 05A108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.-C.; Huang, Q.-G.; Liu, C.; Liu, L.; Liu, X.-J.; Wu, Y.; Wu, Y.-M.; Yi, Z.; You, Z.-Q. Prospects for Taiji to detect a gravitational-wave background from cosmic strings. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2024, 2024, 022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Ai, L.; Ai, Y.; An, Z.; Bai, W.; Bai, Y.; Bao, J.; Cao, B.; Cheng, W.; Chen, C.; et al. A brief introduction to the TianQin project. Acta Sci. Nat. Univ. Sunyatseni 2021, 60, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, S.; Shi, C.; Zhang, J.-D.; Mei, J. Detecting the gravitational wave memory effect with TianQin. Phys. Rev. D 2023, 107, 044023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Liu, L.; Cui, X.; Fang, C.; Wang, Z. Design and wavefront test method for telescope of space-based gravitational wave detection “Taiji” program. J. Astron. Telesc. Instrum. Syst. 2024, 10, 044006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.Y. Structural Design of Spaceborne Laser Emitting Telescope Based on Gravitational Wave Detection. Master’s Thesis, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, H.; Chen, Q.; Ma, Z.; Wang, H. Analysis of laser interference backward stray light based on TianQin space gravitational wave detection. J. Astron. Telesc. Instrum. Syst. 2024, 10, 034007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.; Wang, Y.; Tan, W.; Wu, G.; Chen, H.; Li, W.; Li, Z.; Zhu, F.; Li, Z.; Zhang, X.; et al. Earth–lunar thermal effect on the temperature stability of TianQin telescope and the suppression methods. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2025, 67, 105816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Fan, W.; Fang, S.; Hai, H.; Zhao, K.; Luo, J.; Zhang, R.; Li, B.; Sun, Q.; Fan, L. Optimized design of a gravitational wave telescope system based on pupil aberration. Appl. Opt. 2024, 63, 1815–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Arm Length | Displacement Measurement Accuracy | Power of Laser | Aperture of Telescope | Residual Acceleration | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taiji | 3 × 106 km | 5–10 pm Hz−1/2 | 2 W | ≤50 cm | 3 × 10−15 m/s2/Hz1/2 |

| TianQin | 1.7 × 105 km | 1 pm Hz−1/2 | 1–2 W | ≤35 cm | 1 × 10−15 m/s2/Hz1/2 |

| Weight | Outline | Diameter of Primary Mirror | The First Natural Frequency | Maximal Deformation Under 1 g Load | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | ≤40 kg | ≤600 mm × 600 mm × 900 mm | ≤350 mm | ≥200 Hz | ≤10−5 m |

| Outline Size | Weight | |

|---|---|---|

| Initial scheme | 568 mm × 470 mm × 804 mm | 37.138 kg |

| Density (kg/m3) | Young’s Modulus (GPa) | Poisson’s Ratio | Mechanical Limit | Coefficient of Thermal Expansion | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zerodur | 2530 | 90.3 | 0.26 | 55 MPa (tensile strength) | 0 ± 0.1 × 10−6 |

| Invar steel | 8130 | 147 | 0.24 | 280 MPa (yield strength) | 1.2 × 10−6 |

| Order | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency (Hz) | 268.70 | 326.74 | 391.58 | 450.53 | 518.01 | 684.58 |

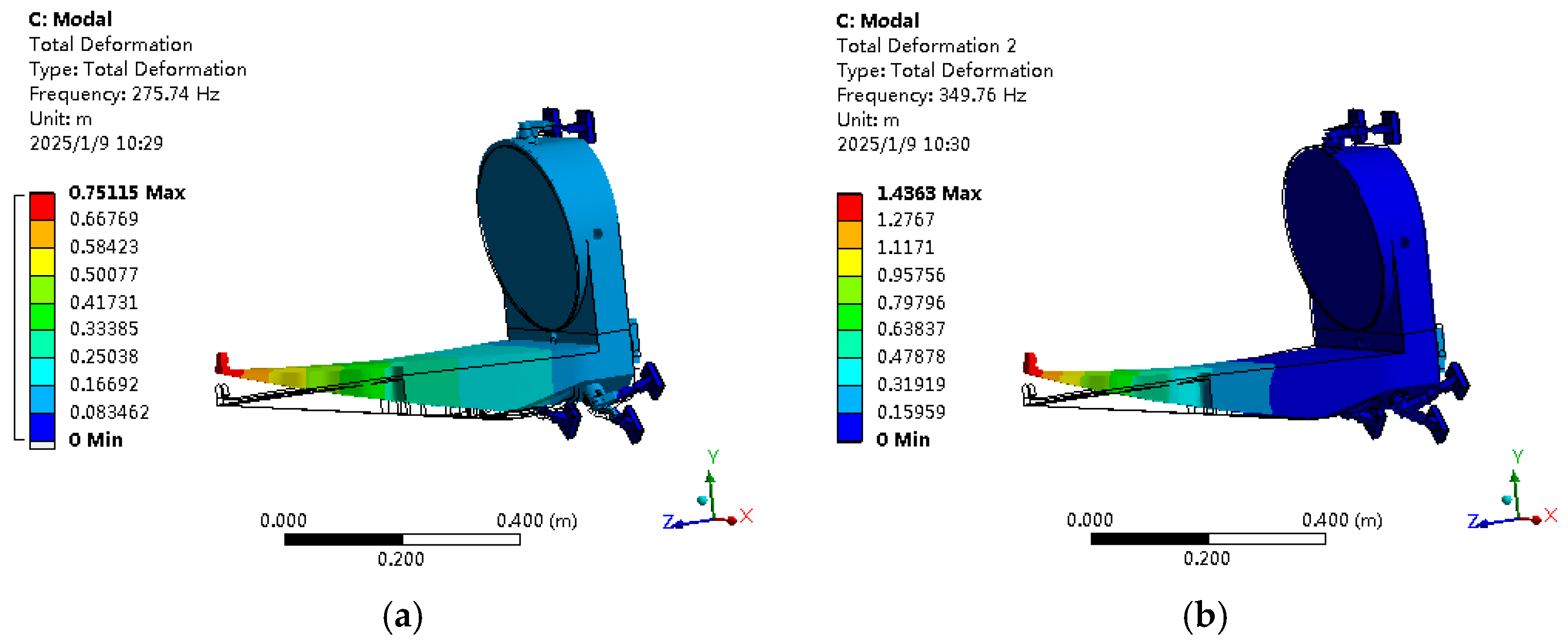

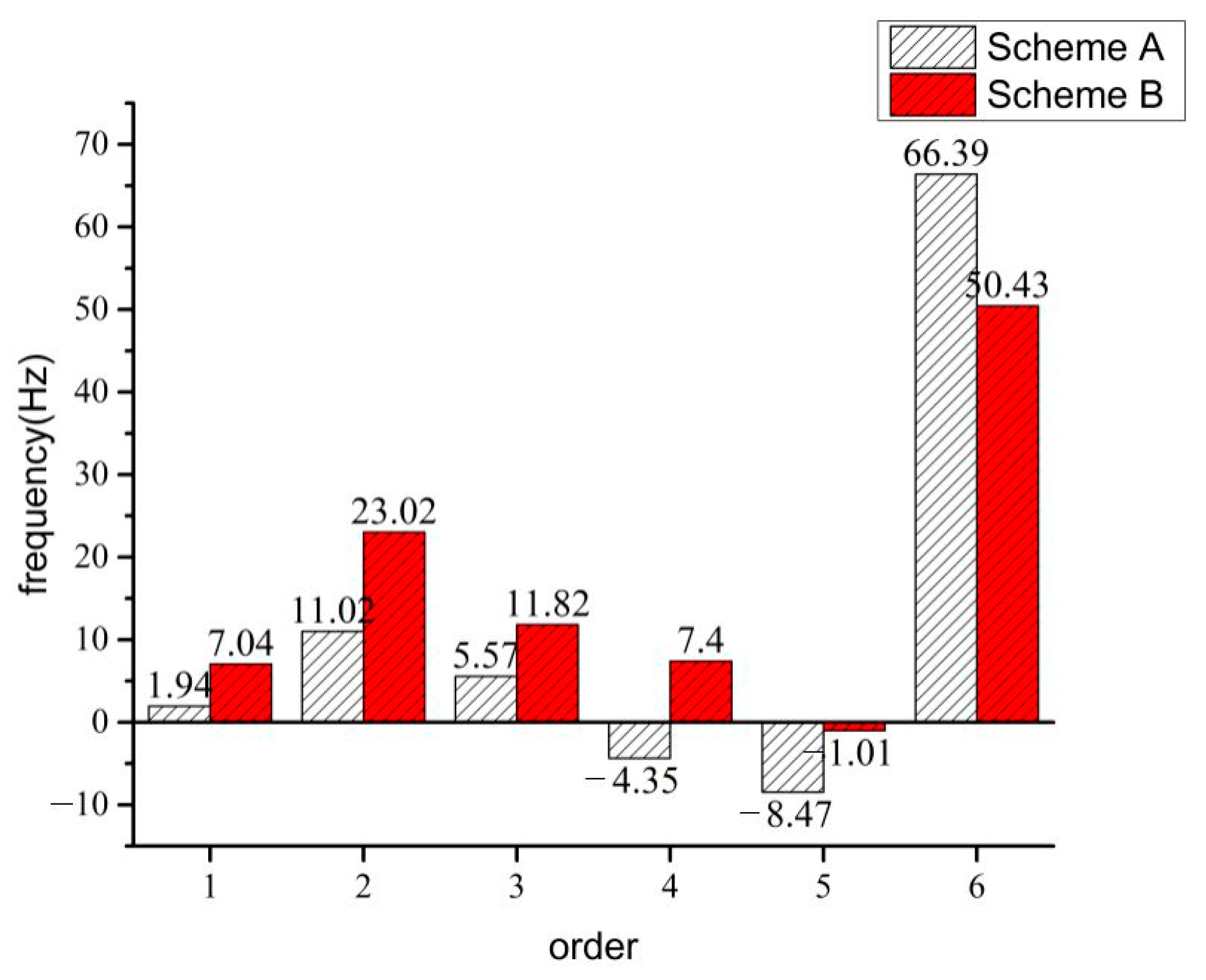

| Order | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency (Hz) | Initial scheme | 268.70 | 326.74 | 391.58 | 450.53 | 518.01 | 684.58 |

| Scheme A | 270.64 | 337.76 | 397.15 | 446.18 | 509.54 | 750.97 | |

| Scheme B | 275.74 | 349.76 | 403.40 | 457.93 | 517.00 | 735.01 |

| Constrained Situation | Types of Elements | Number of Elements | Number of Nodes | Damping Ration in Vibration Analyses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Six freedom degrees | Hexahedral and tetrahedral elements | 69,304 | 142,926 | 0.05 |

| Direction | Maximal Displacement (×10−6 m) | Maximal Stress (MPa) |

|---|---|---|

| +X | 3.032 | 2.821 |

| −Y | 7.135 | 5.069 |

| −Z | 3.092 | 1.992 |

| Δx | Δy | Δz | Δα (Relative Pitch) | Δβ (Relative Yaw) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximal tolerance | 8 × 10−6 m | 8 × 10−6 m | 2 × 10−5 m | 4.8 × 10−5 rad | 4.8 × 10−5 rad |

| Simulation result | ≤10−10 m | 4.736 × 10−6 m | 5.183 × 10−7 m | 3.423 × 10−5 rad | 1.379 × 10−7 rad |

| Maximal Displacement (×10−6 m) | Maximal Stress (MPa) | |

|---|---|---|

| 22 °C to 30 °C | 1.377 | 4.775 |

| 22 °C to 15 °C | 1.205 | 4.178 |

| 20–100 Hz | 100–600 Hz | 600–2000 Hz | grms | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | +3 dB/oct | 0.05 g2 /Hz | −9 dB/oct | 6 |

| Maximal Stress (MPa) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| X | Y | Z | |

| Surface 1 | 2.863 | 6.156 | 4.194 |

| Surface 2 | 1.004 | 3.706 | 0.695 |

| Surface 3 | 1.437 | 2.887 | 1.509 |

| Surface 4 | 6.137 | 9.935 | 1.007 |

| Surface 5 | 1.945 | 5.061 | 8.113 |

| Surface 6 | 3.427 | 2.581 | 3.539 |

| Frequency (Hz) | 10–35 | 35–36 | 36–75 | 75–76 | 76–100 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | 32 m/s2 | Transition | 58.8 m/s2 | Transition | 45 m/s2 |

| Weight | Outline | Diameter of Primary Mirror | The First Natural Frequency | Maximal Deformation Under 1 Gravity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Requirement values | ≤40 kg | ≤600 mm × 600 mm × 900 mm | ≤350 mm | ≥200 Hz | ≤10−5 m |

| Design values | 38.423 kg | 568 mm × 470 mm × 804 mm | 324 mm | 275.74 Hz | 7.135 × 10−6 m |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Song, Y.; Ye, J.; Li, X.; Chen, Q.; Wen, D.; Chai, W.; Yuan, H.; Jiang, G. Structural Design and Analysis of Telescope for Gravitational Wave Detection in TianQin Program. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 13159. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413159

Song Y, Ye J, Li X, Chen Q, Wen D, Chai W, Yuan H, Jiang G. Structural Design and Analysis of Telescope for Gravitational Wave Detection in TianQin Program. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):13159. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413159

Chicago/Turabian StyleSong, Yang, Jing Ye, Xuyang Li, Qinfang Chen, Desheng Wen, Wenyi Chai, Hao Yuan, and Guangwen Jiang. 2025. "Structural Design and Analysis of Telescope for Gravitational Wave Detection in TianQin Program" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 13159. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413159

APA StyleSong, Y., Ye, J., Li, X., Chen, Q., Wen, D., Chai, W., Yuan, H., & Jiang, G. (2025). Structural Design and Analysis of Telescope for Gravitational Wave Detection in TianQin Program. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 13159. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413159