Abstract

Human beings are affected by different types of skin diseases worldwide. Automatic identification of skin disease from Dermoscopy images has proved effective for diagnosis and treatment to reduce fatality rate. The objective of this work is to demonstrate efficiency of three deep learning pre-trained models, namely MobileNet, EfficientNetB0, and DenseNet121 with ensembling techniques for classification of skin lesion images. This study considers HAM1000 dataset which consists of n = 10,015 images of seven different classes, with a huge class imbalance. The study has two-fold contributions for the classification methodology of skin lesions. First, modification of three pre-trained deep learning models for grouping of skin lesion into seven types. Second, Weighted Grid Search algorithm is proposed to address the class imbalance problem for improving the accuracy of the base classifiers. The results showed that the weighted ensembling method achieved a 3.67% average improvement in Accuracy, Precision, and Recall, 3.33% average improvement for F1-Score, and 7% average improvement for Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) when compared to base classifiers. Evaluation of the model’s efficiency and performance shows that it obtained the highest ROC-AUC score of 92.5% for the modified MobileNet model for skin lesion categorization in comparison to EfficientNetB0 and DenseNet121, respectively. The implications of the results show that deep learning methods and classification techniques are effective for diagnosis and treatment of skin lesion diseases to reduce fatality rate or detect early warnings.

1. Introduction

Skin diseases, e.g., skin cancer, are increasingly becoming common among human beings and individuals worldwide [1]. Early diagnosis and treatment for skin diseases/cancer increases the survival rate [2]. Studies have shown that five-year survival chances, for instance for Melanoma skin cancer, is 99%when detected early [1]. Accurate identification of skin lesion type by visual inspection requires experienced dermatologists and process, which is time consuming and subjective [3]. Hence, an automated system for the classification of skin lesions will help dermatologists for quick and accurate identification. A skin lesion is an abnormal change in the color, shape, or texture of the skin, which may be benign or indicative of skin diseases, including cancerous conditions like melanoma [4].

The primary screening tools for pigmented skin lesions are clinical history and physical examination, which are guided by criteria such as the ABCDE rule [5] or the Seven-Point Checklist [6]. These tools can be complemented by dermoscopy [7], which increases diagnostic accuracy by allowing visualization of subsurface structures using polarized light and magnification. If a lesion is suspicious, a biopsy is then indicated—histopathological examination remains the gold standard for diagnosing malignancy. Manual diagnosis is error-prone, laborious, and biased. Therefore, this study shows that deep learning-based approaches for the categorization of skin lesions can reduce manual diagnosis time.

The goal and objective of this work are as follows:

(i) Modification of three pre-trained deep learning models for the grouping of skin lesions into seven distinctive types.

(ii) Weighted Grid Search algorithm to address class imbalance problem for improving the efficiency and accuracy of the base classifiers.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 provides a review of the related literature. Section 3 describes the dataset used in this study. Section 4 outlines the proposed methodology. Section 5 presents the experimental results. Section 6 discusses the findings in detail, including the theoretical and practical implications of the study (Section 6.1), its limitations and future directions (Section 6.2), and the potential for transferability and cross-domain application (Section 6.3). Finally, Section 7 concludes the work.

2. Literature Review

Previous works that explore automated classification of skin lesions using hand-crafted features have been explored. For example, k-Nearest Neighbors (kNN), Bayesian, and Multilayered classifiers have been considered to categorize skin lesion as Melanoma or Benign based on texture, color, and descriptors of shape of skin lesions [8]. The traditional Machine Learning classifiers like Random Forest, Support Vector Machine (SVM), and kNN were deployed to classify 1000 skin sample images into two categories using features such as GLCM, ABCD rule, and shape [9]. These studies show that traditional Machine Learning relies on manually extracted features for skin lesion classification which is subjective, time and energy consuming as well as non-robust in its prediction.

This study suggests that automatic extraction of features from image data by deep learning Algorithms is more appropriate for Computer Aided Diagnosis (CAD) of skin lesions. CAD is cost effective for disease diagnosis in rural or remote areas where there is lack of availability of expert doctors [10]. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN’s) are the class of Deep Neural Networks in the field of deep learning used to extract visual features from image data [11]. One of the methodologies in deep learning is Transfer Learning. Here in, the model trained on one task is used again on another associated task. In terms of Transfer Learning, the reuse of existing trained model for a second task is referred to as pre-trained models. Some of the popular pre-trained models trained on ImageNet [12], e.g., of at least 1000 classes are VGG-16 [13], ReseNet [14], InceptionNet [15], MobileNet [16], DenseNet [17], NASNet [18], EfficientNet [19], etc. These models differ in terms of architecture and input data size.

In Lopez et al. [20] presented a method of using VGGNet for the segregation of skin complaint as Malignant or Benign on International Skin Imaging Collaboration (ISIC) archive dataset and achieved a sensitivity of 78.86%. MobileNet model was used in the study by Chaturvedi et al. [21] for skin lesion classification into seven classes, which showed an overall accuracy of 83.1%. In [22], DenseNet architecture was used for extraction of features from skin lesion images and SVM was used for tagging of the seven skin injuries. A new prediction model on the basis of Deep CNN’s was also introduced for classification into Benign or Malignant and achieved an average accuracy of 97.49% [23].

Ensembling of pre-trained deep learning models increases the efficiency of prediction by combining results of multiple models [23]. An ensemble of CNN’s framework has been proposed by [24], which showed an AUC score of 0.891 for three class classification of skin lesion images. In [25], an ensemble model was presented to classify skin lesions using DenseNet and InceptionV3 pre-trained models on the HAM10000 dataset, which showed a classification accuracy of 91%. In [26], Inception-V3 and ResNet-50 architectures have been used along with ensembling approach to classify skin lesion into seven different categories with validation accuracy of 89.9%. The efficiency of 17 commonly pre-trained CNN architectures on two distinct datasets, ISIC 2019 and PH2, has been carried out by [27]. Extracted features are classified using kNN, decision trees, linear discriminant analysis, Naive Bayes, SVM, and ensemble classifiers. The combination of DenseNet201 as a feature extractor with kNN and SVM classifiers achieved the highest accuracy rates—92.34% and 91.71%, respectively, on the ISIC 2019 dataset. The study [28] systematically investigates the influence of various color spaces—RGB, LAB, HSV, and YUV—on the performance of deep learning models for skin cancer classification. The proposed YUV-RGB pre-processing technique, combined with the tailored CNN, achieved an accuracy of 98.51% on HAM10000 dataset. Object detection framework using YOLOv8 architecture designed to detect five critical dermoscopic structures—globules, milia-like cysts, pigment networks, negative networks, and streaks enhancing the precision of skin lesion analysis [29]. This object detection framework achieved average scores of 0.9758 for the Dice similarity coefficient, 0.954 for the Jaccard similarity coefficient, 0.9724 for precision, 0.938 for recall, and 0.9692 for average precision.

Most of the previous works proposed have achieved high performance results but concentrated only on classifying into two categories such as Malignant or Benign. As there exist various types of skin diseases, designing a multi-class automated classification system for skin lesions will be useful for accurate and fast diagnosis. This work proposes investigative trials by using three popular pre-trained models, namely MobileNet, DenseNet, and EfficientNet, for classification of skin lesion images into seven categories using the grid search weighted average ensembling method.

3. Dataset

In this study’s experimentation, the HAM10000 [30] dataset was used for the training and assessment of the applied method (Section 4). This dataset includes a total of n = 10,015 images of seven different classes. The seven different dermoscopy skin images were Actinic Keratoses (akiec), Basal Cell Carcinoma (bcc), Benign Keratosis-like lesions (bkl), Dermatofibroma (df), Malignant Melanoma (mel), Melanocytic Nevi (nv), and Vascular Lesions (vasc). The Benign Keratosis-like lesions class includes a heterogeneous group of benign skin conditions, such as seborrheic keratoses, solar lentigines, and lichen planus-like keratoses, as defined in the original dataset documentation. The number of images in each class is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

HAM1000 data set split for Training, Validation, and Test set.

4. Methodology

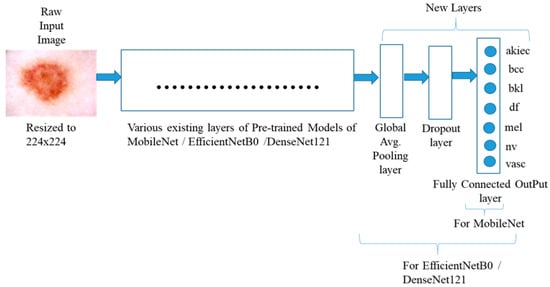

In the method of this study, three pre-trained models, MobileNet [16], EfficientNetB0 [19], and DenseNet121 [17], were utilized for transfer learning in order to categorize the skin lesion images into seven different groups. In all the three models, the last five layers were removed and then three new layers were added to the end of the model. The three new different layers added were Global Average Pooling Layer, Dropout layer with 50% nodes, and one Dense layer with seven nodes. The last five layers of each pre-trained model were removed to tailor the network architecture for the specific task of skin lesion classification. These final layers are originally designed for classification tasks specific to the ImageNet dataset, which includes 1000 generic object categories. Since the target domain in this study involves classifying skin lesion images into seven medical categories, retaining those generic output layers would not be suitable. By removing them, the model’s feature extractor can be preserved while allowing the addition of task-specific layers that are better suited for learning. The suggested structure of the system is shown in Figure 1. The study carried out two experiments, namely (i) Experiment 1 and (ii) Experiment 2.

Figure 1.

Structure of the System used to implement the trained model.

Under Experiment 1, the three models MobileNet, EfficentNetB0, and DenseNet12 were trained on the original dataset with a split-up of Train–Validation–Test as 60%–20%–20%, respectively. Stratified split-up was used to maintain inter-class ratio. The distortion gap in the quantity of images among each class is addressed by Experiment 2 using Data Augmentation. The quantity of images in the train set of each class was made approximately equal to 4800 by data augmentation. The quantity of augmented images in each class for training process is as tabulated in Table 1. The transformations used for augmentation were Rotation by 180°, Width shift by 0.1, Height Shift by 0.1, Horizontal Flip, and Vertical Flip.

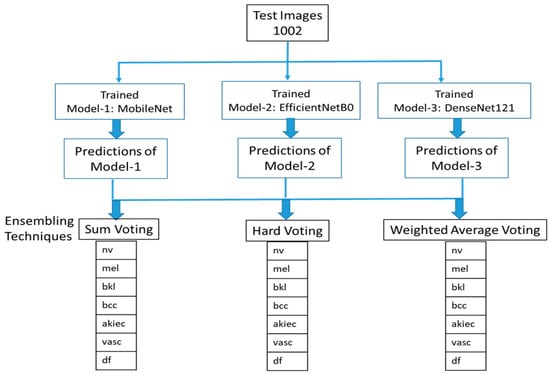

4.1. Ensemble Learning

To achieve a decrease in global errors by coalescing the calculated projections from various classifiers is a big way forward that can lead to perfection. The motivation behind this approach is that every classifier will make different mistakes during training and prediction process. Therefore, combining the outputs of different classifiers will reduce the total errors in the final prediction. In this work, the experimentation with three different ensembling techniques, namely Sum Voting, Hard Voting, and Weighted Average, has been carried out. The structure of the proposed system for ensemble predictions of the three pre-trained models is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Structure of the system to ensemble predictions of the three pre-trained models.

Sum Voting: Let Sk represent the sum voting prediction for the k th test image. Prediction calculation by sum voting is given in Equation (1). represents the probability prediction by model i for jth class with respect to to k th test image. As there are seven classes, j = 1 to 7 and as the models for ensembling considered were three, hence i = 1 to 3. In Equation (1), argmax indicates an operation that finds the argument which gives the maximum value from an objective function, i.e., the class for which the value is maximum with respect to summation of three models probability will be the prediction value.

Majority or Hard Voting: Let Hk represent the hard voting prediction for the kth test image. Prediction calculation by hard voting is given in Equation (2). In Equation (2), mode is the value that appears most often in a set of numbers, i.e., the class that is most frequent in prediction among the three models will be the prediction value. In Equation (2), indicates prediction by the model for k th test image.

Weighted Average: The core achievement attributed with this effortful scrutiny of data is the design of Weighted Ensemble based algorithm to realize superior applicational functioning for the HAM1000 dataset (see Section 3), which is a highly imbalanced seven class dataset. The algorithm proposed was Grid search to obtain best weights for Weighted Average Ensembling technique, as given by Algorithm 1 below.

| Algorithm 1: Grid search for obtaining best weights for the weighted average ensembling technique |

| For W1 = 0 to 0.5 For W2 = 0 to 0.5 For W3 = 0 to 0.5 If accuracy score is more than the previous accuracies, then restore current weights W1, W2, W3 EndIf EndFor EndFor EndFor |

4.2. Evaluation Metrics

In this segment the assessment metrics adopted to examine the functional efficiency of the proposed system for classification of the HAM10000 dataset into seven classes are discussed. The metrics used were Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-Score, MCC, and AUC-ROC score to assess the performance of the proposed method. To explain the evaluation metrics, let us consider the typical confusion matrix of two class classification as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Confusion matrix for binary-class classification.

Accuracy: The Accuracy metric—Equation (3) is used to find out how many of the classifier’s predictions were correct.

Precision: The Precision metric—Equation (4) indicates, out of all samples the classifier labeled as positive, what fractions were correct.

Recall: The Recall metric—Equation (5) indicates, out of all positive samples, what fraction the classifier identified correctly.

F1-Score: The F1-Score—Equation (6) conjoins Precision and Recall having an overall score that depicts how well the classification model performed. F1-score is better than accuracy when the dataset is imbalanced to evaluate the performance of the model.

Matthews Correlation Co-efficient (MCC): MCC (7) takes into account all four values in the confusion matrix, and a large value (i.e., close to 1) signifies acceptable prediction of both classes, even if one class is under or over sampled.

Area Under Curve—Receiver Operating Characteristic (AUC-ROC): AUC-ROC curve helps to envisage how well the classifier performed. True Positive rate (TPR) conveys the proportion of positive class that got correctly detected by the model. False Positive rate (FPR) communicates the share of Negative class incorrectly classified. An elevated TPR and a lesser FPR is necessary to correctly classify the negative classes. Probability curve of TPR against FPR at various threshold values is given by ROC curve. A higher AUC score indicates better results of the model in predicting the positive class as positive and negative as negative.

5. Results

The implementation of the experiments (see Section 4) was carried out using Python Version 3 programming version 3 with Keras 2.5.0 on Google Colab [31].

Training Process: For optimal regulation of the model during the training process, Adam optimizer with learning rate of 0.0001 has been used. The batch size for training was 72 for Experiment 1 and 329 for Experiment 2. The batch size validation was 18 for both the experiments. The “loss function” used was Categorical Cross Entropy. The input image size considered was 224 × 224. The raw images served as input to the deep learning models without performing any external preprocessing.

The original weight parameters in the three models were retained except the last 23 layers, i.e., the weight parameters of only the last 23 layers were trained during training process. Table 3 shows the quantity of trainable and non-trainable parameters of the three models.

Table 3.

Trainable and non-trainable parameters of the pre-trained models.

Callback function was used during training process for early stopping. During training process of any deep learning model, too many epochs may lead to overfitting and too few epochs may lead to underfitting. It is critical to end the process in time for accurate results. Methodology of “Early Stopping” allows to identify significantly considerable number of training epochs and end the training upon cease of improvement in model performance on validation data. In experiments, the Early Stopping was used to monitor validation loss with a patience of three, i.e., for three numbers of epochs with no improvement after which training was stopped. When the training must have been stopped, the model with best weights will be restored and saved.

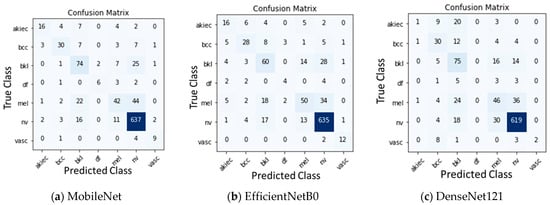

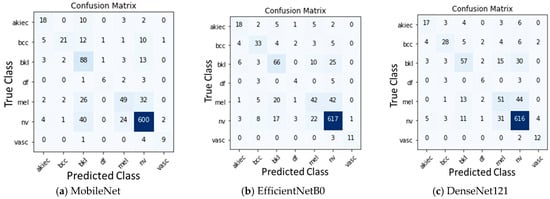

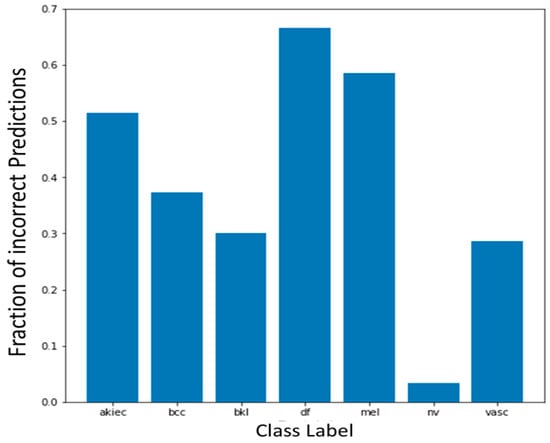

After training the models, the models were evaluated on the test data. The quantitative results of all the three base models, namely, MobileNet, EfficientNetB0, and DenseNet121 along with Sum voting, Majority voting, and Weighted average ensembling is illustrated in Table 4 for Experiment 1 and Table 5 for Experiment 2. Model-wise, MobileNet showed the highest Accuracy (0.81), Precision (0.80), Recall (0.81), F1-Score (0.80), MCC (0.62), and AUC-ROC Score (0.925) when compared to the EfficientNetB0 and DenseNet121 under Experiment 1. Under Experiment 2, AUC-ROC Score was greater for all the three models, MobileNet (0.941), EfficientNetB0 (0.917), and DenseNet121 (0.913) when compared to Experiment 1. Confusion matrix of all the three models for Experiment 1 and Experiment 2 are shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4. Figure 5 shows the fraction of misclassified cases for each of the seven classes for Experiment 1 of ensemble weighted average method, highlighting the percentage of misclassification coming from ‘df’ class is more, examining how varying fine-tuning depth in MobileNet affects performance, and Fine-tuning the last 10, 23, 50, and 75 layers, observing a consistent improvement in classification performance with deeper fine-tuning, Table 6. AUC_ROC score improved from 89.1% (with 10 layers fine-tuned) to 94.3% (with 75 layers), while the accuracy increased from 78% to 83%.

Table 4.

Tabulation of results of Experiment 1 without augmentation.

Table 5.

Tabulation of results of Experiment 2 with augmentation.

Figure 3.

Confusion Matrix for Experiment 1 without augmentation.

Figure 4.

Confusion Matrix for Experiment 2 with augmentation.

Figure 5.

Fraction of misclassification cases by class wise.

Table 6.

Performance comparison of MobileNet model with different fine-tuning depths.

To further mitigate the impact of class imbalance beyond the training phase, focal loss [32] was incorporated into the model training objective. Focal loss dynamically scales the standard cross-entropy loss, emphasizing difficult examples by reducing the relative loss contribution of well-classified samples. In the experiments, γ = 2.0 and α = 0.25 were used while fine-tuning the last 23 layers of the MobileNet architecture. This adaptation resulted in a test accuracy of 77%, precision of 64%, recall of 58%, F1-score of 60%, and a high AUC-ROC of 92.7%, suggesting improved robustness and discrimination capacity in the presence of class imbalance.

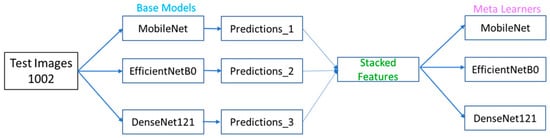

To validate the robustness of the ensemble strategy, implemented stacking-based integration using three different meta-learners: Logistic Regression, Random Forest, and Support Vector Machine and base-learners as: MobileNet, EfficienetNetB0 and DenseNet12 (Figure 6). Results of the stacking ensemble approach are shown in Table 7. Random Forest achieved the best performance with an accuracy of 0.84, precision of 0.82, recall of 0.84, and F1-score of 0.83.

Figure 6.

Framework of Stacking ensemble approach.

Table 7.

Tabulation of results of Stacking ensemble approach.

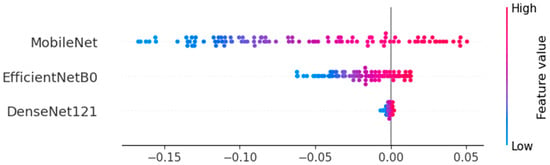

For the proposed grid search Algorithm 1, the best weights identified were [0.3, 0.1, 0.2] for MobileNet, EfficientNetB0, and DenseNet121 under Experiment 1, and [0.3, 0.2, 0.2] for Experiment 2, respectively. For Experiment 1 with weights as [0.3, 0.1, 0.2], a maximum accuracy of 83.13% was obtained. For Experiment 2 with weights as [0.3, 0.2, 0.2], a maximum accuracy of 82.73% was obtained. SHAP analysis was employed to assess the contribution of the grid search Algorithm 1 for Experiment 1. Figure 7. indicates that MobileNet contributes the most, aligning with the assigned ensemble weights of 0.3 (MobileNet), 0.2 (DenseNet121), and 0.1 (EfficientNetB0).

Figure 7.

SHAP analysis to assess the contribution of grid search algorithm.

Table 8 presents a comparison of the proposed ensemble and stacking approaches with existing models such as MobileNet and ensemble architectures (e.g., VGG16 + GoogleNet). The proposed stacking model (MobileNet + EfficientNetB0 + DenseNet121 with Random Forest) achieved the highest accuracy of 84%, demonstrating its competitive performance and robustness for 7-class skin lesion classification. To evaluate the robustness of the MobileNet model, five independent runs were and the mean and standard deviation for accuracy, AUC-ROC, precision, recall, and F1-score was reported. As summarized in Table 9, the model achieved a mean AUC-ROC of 0.8009 ± 0.0674 and accuracy of 0.6892 ± 0.0201, indicating moderate but consistent performance across runs.

Table 8.

Results comparison with other published works.

Table 9.

Tabulation of standard deviation of the metrics across five runs of MobileNet model.

6. Discussion

This study presents a novel ensemble deep learning approach for the classification of skin diseases using dermatoscopic images. The key findings of this study (see Section 5) highlight the efficacy of the proposed weighted average ensemble model, which combines the outputs of DenseNet121, MobileNet, and EfficientNetB0. To note, the ensemble model achieved superior classification performance, with an overall Accuracy of 83%, Precision of 82%, Recall of 83%, and F1-score of 82, outperforming the individual base models or existing studies that only measured Accuracy.

6.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications of the Study

Theoretically, this research contributes to the growing body of literature on ensemble learning and deep neural networks in medical imaging [2,3,9,20,21]. By demonstrating the advantages of a weighted average ensemble approach [24,25,26], it validates the hypothesis that intelligently combining models with complementary strengths can significantly enhance classification performance. This aligns with the ensemble learning theory [24,25,26], which posits that diverse models can correct each other’s errors when integrated appropriately.

Practically, the high accuracy and reliability of the proposed ensemble model (see Section 5) suggest that it can serve as a powerful decision support tool in clinical settings. Dermatologists could benefit from automated systems that rapidly and accurately classify skin diseases, potentially reducing diagnostic errors and improving patient outcomes [2,7,27]. Furthermore, the method requires minimal preprocessing and performs well without extensive domain-specific feature engineering, making it more accessible and easier to deploy in real-world applications. To further assess its deployment readiness, the study evaluated the model’s inference performance and computational requirement. The final MobileNet-based model, fine-tuned by unfreezing the last 23 layers, resulted in a compact model size of 28.22 MB. It achieved an average inference time of 64.41 milliseconds per image, demonstrating its potential for real-time application. These characteristics underscore the model’s suitability for edge computing environments and mobile health applications.

6.2. Limitations and Future Directions

Despite the promising results, the authors acknowledge that the study comes with limitations. First, the dataset used—while comprehensive—may not fully capture the variability encountered in diverse clinical environments, such as differences in lighting, image resolution, and patient demographics. Second, the study did not investigate the model’s performance on imbalanced datasets in depth, which is critical for rare skin conditions. Third, the method was validated only on one dataset; further external validation is necessary to confirm its generalizability. Additionally, the ensemble weights were determined empirically, and future work could explore automated or adaptive weighting mechanisms to further enhance performance.

Future research should aim to validate the ensemble model across larger, more diverse datasets and in real-world clinical environments. Incorporating explainability features—such as saliency maps or Grad-CAM visualizations—would enhance trust and adoption by medical professionals. Moreover, exploring other ensemble strategies, such as boosting, could yield further improvements. Integration with electronic health records and patient history could also provide a more holistic diagnostic tool.

6.3. Transferability and Cross-Domain Application

A notable strength of the proposed method is its transferability. The ensemble framework is not limited to skin disease classification and can be adapted for other medical imaging domains such as retinal disease diagnosis, lung pathology detection in chest X-rays, or even histopathological image analysis. Beyond healthcare, the model architecture and ensemble strategy could be leveraged in other sectors where accurate image classification is critical, such as quality control in manufacturing, remote sensing in agriculture, or security and surveillance. The minimal preprocessing requirements and scalability of the model further support its application across different domains. Thus, re-enforcing the entire domain or field of process mining and its applications in real-time.

7. Conclusions

The occurrence of imbalanced data sets is inevitable in the applications such as fraud detection, cancer image classification, etc. Imbalance dataset classification is prominent in the field of Machine Learning. The dataset used for this work was HAM10000, which has class imbalance ratios of [58, 9.67, 9.55, 4.47, 2.84, 1.23] for seven skin lesion images [Nv, Mel, Bkl, Bcc, Akiec, Vasc, Df]. Contributions of this work were two-fold. First, modification of the three pre-trained deep learning models namely MobileNet, EfficientNetB0, and DenseNet121 to classify skin lesion images into seven classes. Second, a grid search algorithms for weighted average ensembling to address class imbalance was proposed. The proposed weighted ensembling showed a 3.67% average improvement for Accuracy, Precision, Recall, 3.33% average improvement for F1-Score, and 7% average improvement for Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) when compared to the base classifiers. The study observed the highest ROC-AUC score of 92.5% for the modified MobileNet model for skin lesion categorization when compared to EfficientNetB0 and DenseNet121. Future work can be explored by ensembling different resample data sets with various Deep Learning architectures to progress the operational efficiency of skin lesion classification.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Methodology, Software and Validation was carried out by U.V. The Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data curation has been carried out by J.M.S. The writing—original draft preparation and project administration have been performed by S.G. and K.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset used in this work is available at URL: https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/DBW86T (accessed on 1 July 2024).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Skin Cancer Facts & Statistics. Available online: https://www.skincancer.org/skin-cancer-information/skin-cancer-facts/ (accessed on 1 August 2024).

- Conic, R.Z.; Cabrera, C.I.; Khorana, A.A.; Gastman, B.R. Determination of the impact of melanoma surgical timing on survival using the National Cancer Database. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2018, 78, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morton, C.A.; Mackie, R.M. Clinical accuracy of the diagnosis of cutaneous malignant melanoma. Br. J. Dermatol. 1998, 138, 283–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.Q.; Hussain, A.; Rehman, S.U.; Khan, U.; Maqsood, M.; Mehmood, K.; Khan, M.A. Classification of melanoma and nevus in digital images for diagnosis of skin cancer. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 90132–90144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandic, J.; Kovacevic, S.; Karabeg, R.; Lazarov, A.; Opric, D. Teledermoscopy for skin cancer prevention: A comparative study of clinical and teledermoscopic diagnosis. Acta Inform. Medica 2020, 28, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walter, F.M.; Prevost, A.T.; Vasconcelos, J.; Hall, P.N.; Burrows, N.P.; Morris, H.C.; Kinmonth, A.L.; Emery, J.D. Using the 7-point checklist as a diagnostic aid for pigmented skin lesions in general practice: A diagnostic validation study. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2013, 63, e345–e353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binder, M.; Schwarz, M.; Winkler, A.; Steiner, A.; Kaider, A.; Wolff, K.; Pehamberger, H. Epiluminescence microscopy: A useful tool for the diagnosis of pigmented skin lesions for formally trained dermatologists. Arch. Dermatol. 1995, 131, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz, D.; Berenguer, V.; Soriano, A.; Sánchez, B. A decision support system for the diagnosis of melanoma: A comparative approach. Expert Syst. Appl. 2011, 38, 15217–15223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugan, A.; Nair, S.A.H.; Kumar, K.S. Detection of skin cancer using SVM, random forest and kNN classifiers. J. Med. Syst. 2019, 43, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajwa, M.N.; Muta, K.; Malik, M.I.; Siddiqui, S.A.; Braun, S.A.; Homey, B.; Dengel, A.; Ahmed, S. Computer-aided diagnosis of skin diseases using deep neural networks. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jogin, M.; Madhulika, M.S.; Divya, G.D.; Meghana, R.K.; Apoorva, S. Feature extraction using convolution neural networks (CNN) and deep learning. In Proceedings of the 3rd IEEE International Conference on Recent Trends in Electronics, Information & Communication Technology (RTEICT), Bangalore, India, 18–19 May 2018; pp. 2319–2323. [Google Scholar]

- Russakovsky, O.; Deng, J.; Su, H.; Krause, J.; Satheesh, S.; Ma, S.; Huang, Z.; Karpathy, A.; Khosla, A.; Bernstein, M.; et al. Imagenet large scale visual recognition challenge. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2015, 115, 211–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1409.1556. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Szegedy, C.; Liu, W.; Jia, Y.; Sermanet, P.; Reed, S.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Vanhoucke, V.; Rabinovich, A. Going deeper with convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer vision and Pattern Recognition, Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, A.G.; Zhu, M.; Chen, B.; Kalenichenko, D.; Wang, W.; Weyand, T.; Andreetto, M.; Adam, H. Mobilenets: Efficient convolutional neural networks for mobile vision applications. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1704.04861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Liu, Z.; Van Der Maaten, L.; Weinberger, K.Q. Densely connected convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 4700–4708. [Google Scholar]

- Zoph, B.; Vasudevan, V.; Shlens, J.; Le, Q.V. Learning transferable architectures for scalable image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 8697–8710. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, M.; Le, Q. Efficientnet: Rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Long Beach, CA, USA, 9–15 June 2019; pp. 6105–6114. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, A.R.; Giro-i-Nieto, X.; Burdick, J.; Marques, O. Skin lesion classification from dermoscopic images using deep learning techniques. In Proceedings of the 2017 13th IASTED International Conference on Biomedical Engineering (BioMed), Innsbruck, Austria, 20–21 February 2017; IEEE: New York City, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 49–54. [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi, S.S.; Gupta, K.; Prasad, P.S. Skin lesion analyser: An efficient seven-way multi-class skin cancer classification using mobilenet. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advanced Machine Learning Technologies and Applications, Innsbruck, Jaipur, India, 13–15 February 2020; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 165–176. [Google Scholar]

- Carcagnì, P.; Leo, M.; Cuna, A.; Mazzeo, P.L.; Spagnolo, P.; Celeste, G.; Distante, C. Classification of skin lesions by combining multilevel learnings in a DenseNet architecture. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Image Analysis and Processing, Trento, Italy, 9–13 September 2019; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 335–344. [Google Scholar]

- Albahar, M.A. Skin lesion classification using convolutional neural network with novel regularizer. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 38306–38313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harangi, B. Skin lesion classification with ensembles of deep convolutional neural networks. J. Biomed. Inform. 2018, 86, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shekar, B.H.; Hailu, H. An Ensemble Method for Efficient Classification of Skin Lesion from Dermoscopy Image. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computer Vision and Image Processing, Prayagraj, India, 4–6 December 2020; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 161–178. [Google Scholar]

- Shahin, A.H.; Kamal, A.; Elattar, M.A. Deep ensemble learning for skin lesion classification from dermoscopic images. In Proceedings of the 2018 9th Cairo International Biomedical Engineering Conference (CIBEC), Cairo, Egypt, 20–22 December 2018; IEEE: New York City, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 150–153. [Google Scholar]

- Benyahia, S.; Meftah, B.; Lézoray, O. Multi-features extraction based on deep learning for skin lesion classification. Tissue Cell 2022, 74, 101701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mamadou, D.; Ayikpa, K.J.; Ballo, A.B.; Kouassi, B.M. HAYU Analysis of the Impact of Color Spaces on Skin Cancer Diagnosis Using Deep Learning Techniques. Rev. D’intelligence Artif. 2023, 37, 1377–1385. [Google Scholar]

- Chabi Adjobo, E.; Sanda Mahama, A.T.; Gouton, P.; Tossa, J. Automatic localization of five relevant Dermoscopic structures based on YOLOv8 for diagnosis improvement. J. Imaging 2023, 9, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tschandl, P.; Rosendahl, C.; Kittler, H. The HAM10000 dataset, a large collection of multi-source dermatoscopic images of common pigmented skin lesions. Sci. Data 2018, 5, 180161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Google Colaboratory. Available online: https://colab.research.google.com/ (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- Mukhoti, J.; Kulharia, V.; Sanyal, A.; Golodetz, S.; Torr, P.; Dokania, P. Calibrating deep neural networks using focal loss. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 15288–15299. [Google Scholar]

- Majtner, T.; Baji’c, B.; Yildirim, S.; Hardeberg, J.Y.; Lindblad, J.; Sladoje, N. Ensemble of convolutional neural networks for dermoscopic images classification. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1808.05071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).